K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 55

September 30, 2016

Learn How to Set Up the Potential for Change in Character Arcs

Note from K.M. Weiland: Welcome to a special follow-up post to my (temporarily) completed series The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel. Wordplayer and frequent blog commenter Usvaldo de Leon, Jr. (who will no doubt remind me “commenter” is not a word!) sent me the following thoughts on the use of excellent character arcs in Ant-Man. His comments were so good I had to share, and he was gracious enough to oblige. Please enjoy one last look at my favorite superhero film series before we take a break until Dr. Strange releases in November…

***

I used to be a psychic in the circus; indulge me: you have read a book or watched a film or TV show… perhaps even many? Maybe you have even watched a play (a “play” is a TV show with live actors, no commercial breaks, and you have to pay for your snacks)?

You may have noticed these all are stories, communicating themes both noble and base. The agent who communicates this theme is the protagonist, who changes throughout the story to elucidate the theme. This is referred to as a character arc: the character begins at Point A, flies through the air like Morpheus and lands at Point B, far away. When they land at Point B they are utterly changed and this change has two factors: it is both a result of the events of the story and emblematic of the theme of the story.

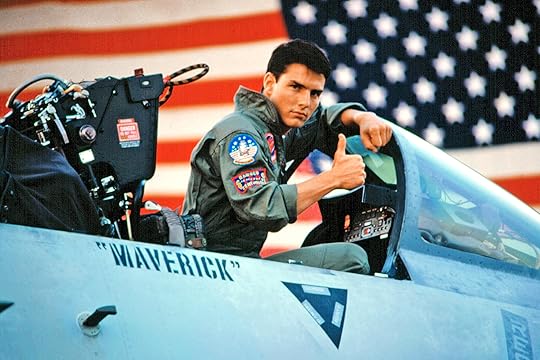

It is theme that separates; story is extremely common. It is dreary, even: Boy Meets Girl, Boy Loses Girl, Boy Wins Girl Back is the story for an entire genre. Similarly, Top Gun and Flight: same story (both feature inverted planes, in fact). Ben Hur and Gladiator: same story. Lord Foul’s Bane and Dreamlander: same story. Like siblings, they have a familial resemblance, but their themes ensure they are different. There is more than one path through the forest; a warren of routes from Points A to B.

How Theme Demonstrates Character Arcs

When we say the protagonist changes, what is actually changing? It is their inner state that is changing. They believe a Lie and over the course of the story they discover the Truth. This happens in three phases: Point A, the jumpoff point; the Midpoint, or flying through the air like Morpheus; and Point B, the ending state. (Note that when Neo, who is not prepared to change as a character, makes this jump he fails spectacularly. The metaphor is a metaphor.)

In Ben Hur, Ben Hur has a lightness of soul (jump-off point); after being sold into slavery, his only goal becomes revenge (flying); but through Jesus, he learns forgiveness and the power of grace (the landing spot).

Maximus, in Gladiator on the other hand, lives at the right hand of the Devil, his troops unleashing hell upon his command; after being sold into slavery, his only goal becomes revenge; he gets his revenge and with it the release of death.

Top Gun is the story of a U.S. Navy fighter pilot, prettier than he is smart, who does things his way until he gets it through his thick skull that he has to play nice with others.

Flight is the story of a hotshot commercial jet pilot, prettier than he is smart, who does things his way until he finds himself in a situation he cannot fly out of.

The theme of Top Gun is: One must know their place, be selfless and give their all to help the team win.

In Flight, it is that a pilot—and a man—must care more for others than himself.

For the theme to work with the story, the protagonist needs to progress in line with the story beats.

At Point A, Maverick is so concerned with demonstrating his awesomitude he forgets to have his buddy’s back, which nearly kills the buddy. Maverick is so dense that he does not even understand why this is a problem. However, by Point B: Maverick is aware he has great ability but is willing—even eager—to sublimate that ability for the Top Gun, Iceman, if it accomplishes the team’s goal. (The goal in this case being starting World War III by shooting down Soviet jets, but hey, I never said Top Gun was thoughtful, only instructive.)

In Flight, Point A finds Whip Whitaker hopelessly addicted, deeply irresponsible, and leading a selfish life. Point B finds him at peace, despite jail, and serving others. He has lost everything except the things he needed: his self-respect and the love of family and friends.

Which brings us to the Marvel film Ant-Man. Protagonist Scott Lang also begins in jail and comes close to winding up right back there for most of the film. How he avoids that fate is the arc he undergoes. How does this happen?

Begin Your Story 180 Degrees Away From the Theme

The only way to prove the importance of your theme is to put your main character in diametric opposition to the theme at the start. Point B is the character aligned with the theme. Push point A as far from the theme as possible. The plot is designed to get the protagonist from Point A to Point B.

The theme of Ant-Man is: A hero is a person who makes a tremendous sacrifice for the greater good, usually at great cost to himself.

As the film begins, Point A for Scott is, “I can’t do anything that will jeopardize my access to my daughter.” His mindset is selfish. It has nothing to do with what his daughter wants—only what Scott wants. In fact, Scott’s ex-wife tells him what his daughter wants: “Be the hero she already imagines you to be.” If Scott had just done that from the beginning, it would have saved us all a lot of trouble.

In Top Gun, Maverick leaves Cougar’s wing to attempt the impossible and invert his jet. Maverick then goes to retrieve Cougar, who is rattled by the hostile encounter and nearly crashes. With bravery equal to his foolhardiness, Maverick saves the day after initially ruining it. Point A is selfish and reckless.

Whip Whitaker saves the day in Flight, inverting his commercial jet (another impossible move) to crash land in a field and save almost everyone. No one but Whip could have done that. However, Whip is totally lost: doing cocaine the night before a flight and drinking while flying. Point A finds Whip so lost in pride and pain he can’t see how his selfish actions hurt others.

Provide Signposts Along Your Character’s Journey

When you are traveling the interstate, it is easy to wonder: are we there yet? Then a flash on the roadside says: [Place you want to go] 106 miles.

Stories use the same signposts to show how far the main character has traveled. Very often, there are two character types the protagonist can be measured against (h/t Chris Soth): the character who represents the past and no change and the character who represents the future and positive change.

In Ant-Man, the characters who represent the past are Scott’s criminal buddies. Eventually, however, even they change, reflecting the theme, as does every major character in the film (save one), but in the beginning they want to hold Scott back.

The character who represents the positive change future is Antony, Scott’s carpenter ant steed. Like all the ants, Antony stands ready to sacrifice for the greater good. Throughout the film, the ants work together selflessly to accomplish the team goals.

(It is one of the great weaknesses of the film that, when Antony is killed, the moment means nothing because the ants are all CGI and have zero personality. I refer you to the first and still best film in this series, Iron Man, which anthropomorphized not one but two robots, for an example of how it can be done).

Top Gun’s character who represents not-changing is Goose, Maverick’s RIO. Goose enables Maverick in his reckless antics, which ultimately costs him his life. The character who represents positive change—what Maverick could be—is Iceman. Maverick has no truer friend (at least to his flying career) than Iceman, who gives him a steady drumbeat of the actions he should be taking. Because Iceman is written and played repellently, he is usually seen as the antagonist, but the antagonist—the person who is most determined to stop Maverick from reaching his goals—is Maverick himself.

In Flight, the character who represents the past for Whip is his drug dealer Harling, who has a vested interest in keeping Whip out of his mind on drugs. The character who represents the future is the recovering drug addict Nicole, who breaks off their fledgling romance rather than let Whip pull them both down.

Include a Huge Decision at Your Story’s Midpoint

One can never know for sure where a protagonist is headed until the Midpoint. Negative themes are just as valid as positive ones, and it is here the determination is made.

In Ant-Man, the Midpoint comes when Scott is unwittingly sent to infiltrate an Avengers facility. Scott is ordered to abort—but if he had, he would have remained selfish. However, he is confident in his ability to accomplish the mission. The Midpoint is where Scott begins to become selfless (if we don’t have this device, we can’t stop Cross).

After his cancer diagnosis, what does Walter White do in Breaking Bad? He decides to sell drugs. Way to take your arc negative at the Midpoint, Walt!

In Flight, at the Midpoint when Nicole leaves Whip, Whip could have decided there was no longer any point in changing. The negative arc would have ended “happily” with Whip cleared by the National Transportation Safety Board, but at the cost of all his family and friends.

What About the Bad Guy?

In the summer of 1492, it was unbearably hot in Spain and Christopher Columbus could not even. He convinced the queen to give him three ships, and he set sail to party with Rihanna in Barbados. He started in Point A: Spain. He ended in Point B: Hispaniola. What was it that brought him there, across the ocean? It was the wind, an unseen force driving Columbus to make small adjustments every day to stay on course.

For protagonists, the antagonist is like the wind for ships in the age of sail. It is the driving force, constantly pushing characters to arrive at their destination. Unfortunately, none of our previous examples are any good here. Top Gun and Flight both feature internal antagonists; Ant-Man has an antagonist that is kind of foisted onto Scott; it’s one of the major weaknesses of the film. So we will press into service one of the great antagonists of all time: Vader. Darth Vader.

Let us look at Star Wars with fresh eyes. Darth Vader is forced home to Tatooine, where he sees his son Luke has grown up into a hot, whiny mess. Clearly, Darth’s brother and his wife were not up to the job of raising Luke, so Darth has them summarily whacked. This forces Luke’s hand. Instead of staying home like a whiny ne’er-do-well, he must go on an adventure with Obi-Wan.

When Luke arrives at the Death Star, he is pretty much just as whiny as ever. Darth forces him to use his resourcefulness to avoid being crushed (although if the whiny boy is crushed, that would also work; Darth is a tough dad). But the boy does not seem to be getting it. Darth therefore has no choice but to kill the boy’s mentor before the boy’s horrified eyes.

And what do you know? Luke volunteers to attack the Death Star; but he keeps futzing around, so Darth has to get himself winged by Han Solo so the kid will finally take the shot—and who gets the credit for helping this boy grow by learning some tough lessons? Darth? No: Obi-Wan. Nobody ever thanks Daddy. The things fathers do for their children…

It is through the well-timed obstacles the antagonist places in the path of the protagonist that the protagonist, through both reacting and acting, grows and reaches Point B. The reason this is possible is that these two characters are yoked together. They diametrically oppose each other. Luke stands for goodness, light, and artisan lollipops, while Darth stands for evil, darkness, and lollipops mass-produced by starving children. Anything Darth does will negatively affect Luke and vice versa.

In Ant-Man, Darren Cross was Hank Pym’s antagonist and Cross’s actions do not directly affect Scott until the climax.

Carefully Plan Your Climactic Encounter

We’re midway through the Third Act. The main character knows what they need to do. However, it is not understanding but action that defines character. And so the main character will be faced with a crisis where they will be forced to choose: the past or the future? Point A or Point B?

In Ant-Man, that moment comes when Yellow Jacket has Scott’s daughter and is too powerful for Scott to defeat. The only way to stop Yellow Jacket is to go sub-atomic, which is a suicide mission. The crisis: Does Scott continue to be selfish or does he sacrifice himself to save his daughter? Only pausing long enough for the audience to understand the stakes, Scott shrinks himself—fully aligning himself with the film’s theme. He chooses to be the hero his daughter always imagined him to be.

In Top Gun, Maverick is faced with a double crisis: Does he let his fear get in the way of rescuing his teammates? And will Maverick fly as the wingman or will he does he own thing? Maverick conquers his fear and sublimates his ego to accomplish the mission. He chooses to be a teammate.

In Flight, Whip is before the NTSB when he is asked about two missing vodka bottles. The crisis: Does Whip continue lying and smear his sometime girlfriend Trina, who died in the crash? Or does he stand up, take responsibility for his actions, which will send him to prison? Whip decides it is time to tell the truth, landing him in prison. He chooses to accept responsibility.

The crisis moment is the theme question. Is the main character going to align to the theme? Are they going to choose to become what the theme dictates they become? (Spoiler Alert: Yes)

Prove Your Character’s Change in the Resolution

Have you ever noticed people smile all the time in films? The positive arc is by far the most popular arc, which means the ending is usually a new beginning: Maverick and Iceman smiling and… hugging? (I might be misremembering that.) Whip and his son bonding on a prison visit. And perhaps most improbably, Scott having dinner with his ex-wife and her fiancé, with good feelings all around, interrupted by a possible call for Scott to join the Avengers.

There needs to be a moment at the end of a story where everyone catches their breath and reflects on how far the protagonist has come (in a positive or negative arc; a flat arc character does not change). This coda reinforces the change and sends the audience off in the right emotional state.

The character arc concept is a key element in developing a satisfying story. The character arc is one of the primary reasons mankind has stories. Aristotle laid down the rules millennia ago; even today, reading Poetics is pretty much all you need. Why are you still reading this?

Stay tuned: In November, we’ll be learning some more marvelous things from Dr. Strange.

Previous Posts in This Series:

Iron Man: Grab Readers With a Multi-Faceted Characteristic Moment

The Incredible Hulk: How (Not) to Write Satisfying Action Scenes

Iron Man II: Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist

Thor: How to Transform Your Story With a Moment of Truth

Captain America: The First Avenger: How to Write Subtext in Dialogue

The Avengers: 4 Places to Find Your Best Story Conflict

Iron Man III: Don’t Make This Mistake With Your Story Structure

Thor: The Dark World: How to Get the Most Out of Your Sequel Scenes

Captain America: The Winter Soldier: Is This the Single Best Way to Write Powerful Themes?

Guardians of the Galaxy: The #1 Key to Relatable Characters: Backstory

The Avengers: Age of Ultron: The Right Way and the Wrong Way to Foreshadow a Story

Ant-Man: How to Choose the Right Antagonist for Your Story

Captain America: Civil War: How to Be a Gutsy Writer: Stay True to Your Characters

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! In your character arcs, what are your characters’ starting and ending mindsets? Tell me in the comments!

The post Learn How to Set Up the Potential for Change in Character Arcs appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 26, 2016

7 Questions You Have About Scenes vs. Chapters

A chapter is a chapter and a scene is a scene. Or are they? What’s the differences between scenes vs. chapters? Are they ever the same thing? Must a chapter always be a complete scene? Or must a scene always be a chapter? What about scene breaks and chapter breaks? Is there a difference?

A chapter is a chapter and a scene is a scene. Or are they? What’s the differences between scenes vs. chapters? Are they ever the same thing? Must a chapter always be a complete scene? Or must a scene always be a chapter? What about scene breaks and chapter breaks? Is there a difference?

These are all questions I receive regularly from writers, and they’re all good questions with surprisingly simple answers.

The shortest and simplest answer to all of these questions is: yes, scenes and chapters are different, with very different structural roles to play within your story.

Let’s take a look at five important questions about scenes vs. chapters, which will help you better understand and control your narrative.

1. Why Do Authors Have Trouble Differentiating Scenes vs. Chapters?

First of all, let’s consider why scenes vs. chapters is even a big question at all.

Mostly, it’s because chapters are obvious and scenes aren’t. As writers, we all start out as readers, and to readers, the concept of chapters is very obvious, very visual. On its surface, a book seems to be divided into chapters, right? Scenes, then, are just smaller structural integers within the chapters.

But then, when you start learning about scene structure, you realize there’s actually a whole lot more to scenes than you thought—and a whole lot less to chapters. Nobody ever talks about “chapter structure” after all.

Turns out it’s the comparatively invisible scene that is the far more important structural unit within a story than is the obvious chapter. At first glance, that seems counter-intuitive, and that’s what trips writers up in understanding the unequal importance of scenes vs. chapters.

2. What’s the Difference Between Scenes vs. Chapters?

So what is the difference between scenes vs. chapters?

Scenes are very specific structural building blocks within your story. Each scene is made up of six distinct parts (see below), all of which are necessary in order for each scene to build into the following one to create a seamless narrative. Scene divisions are non-negotiable.

Chapters, on the other hand, are completely arbitrary divisions within a book. It’s true they do impose order upon a novel—and, as a result, a certain sense of structure. But, on the story level, they actually have nothing whatsoever to do with structure.

Chapter divisions are more about pacing than anything else. You might write a book with no chapter divisions (such as Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead) or a humongous fantasy novel with only nine chapters (such as Sergei and Marina Dyachenko’s The Scar) or one with chapters of only a single sentence (such as the notorious “Rinse” in Stephen King’s authorial nightmare Misery).

Chapters can be any length—from the entirety of the book to a single word.

In short, scenes are logical decisions; chapters are creative decisions.

3.What Must a Good Scene Accomplish?

For the moment, let us consider scenes and chapters separately to understand what each is responsible for accomplishing within your story.

Because scenes are ultimately much more complicated and much more important than chapters, they can be the more difficult of the two for writers to initially get their heads around. I’ve written extensively about scene structure in this series and in my book Structuring Your Novel, but here’s a crash course in good scene structure.

First off, remember scene structure has absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with chapter divisions. (More on that in a bit.) The scene is always a complete unit unto itself, regardless how long or short it turns out to be. What’s important in designing or identifying a scene is making sure the following six parts are all present.

We start by dividing each scene into two parts: scene (action) and sequel (reaction). We then further divide each of those halves into three more pieces each:

Scene

1. Goal (the protagonist or POV character sets out to accomplish or gain something).

2. Conflict (en route to his goal, his efforts are blocked by an obstacle of some type).

3. Disaster (the character’s attempt to gain his goal is at least partially stymied, forcing him to move forward on the diagonal, instead of rushing straight ahead through the plot).

Sequel

4. Reaction (the character must then react, however briefly or lengthily, to the previous disaster—this is where the vast majority of character development will take place).

5. Dilemma (as the result of the disaster, the character is confronted with a new complication or dilemma in his attempt to reach his main story goal).

6. Decision (the character comes to a decision about how best to act, prompting a new goal in the next scene).

And then the cycle endlessly repeats throughout the story.

Each scene is a domino. When set up correctly, scenes create a seamless line of cause and effect that almost effortlessly powers your entire plot.

4. What Must a Good Chapter Accomplish?

Good book chapters have two primary roles:

1. Chapters Control Pacing

Chapters create a sense of rhythm within the story. Depending on the length of each chapter, this rhythm will either speed or slow the pacing.

Shorter chapters create faster pacing—which is why thriller authors such as James Patterson often opt for hundreds of chapters, some of which are no longer than a page.

Longer chapters, in turn, slow the pacing. Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey/Maturin series recreates the leisurely, often charmingly indulgent style of early 19th-century literature. One of O’Brian’s more obvious techniques in achieving this pacing is his employment of very long chapters, some of which require an hour or more to read.

Shorter chapters are often used in thrillers to achieve faster pacing, while more leisurely books implement longer chapters to slow the pacing.

It’s true scene length also plays a role in pacing, but not to nearly the same extent as chapter length. Because chapters are much more obvious to readers (rather like commercial breaks in a TV show), they exercise much more blatant control over the reading experience.

2. Chapters Keep Readers Reading

The second role of the chapter is to create an experience that convinces readers to keep reading. Even to dedicated readers, books are undeniably a large time commitment. There’s never any guarantee readers will actually make it through your entire book—which means it falls to you to convince them to keep reading.

Chapters are the key to influencing readers into the proper mindset to continue turning pages. The control chapters exercise over pacing plays a role in this. Even more importantly, however, is the opportunity each chapter ending and beginning offers to hook readers back into the story.

Just as you have to hook readers with the beginning of the book, you have to re-hook them throughout the book. You’ll do this through reveals, scene disasters, and plot twists. But you’ll also do it twice within every chapter—at the beginning and at the end. Done skillfully enough, you might even convince readers to read straight through without ever putting the book down.

5. Does Every Scene Have to Be a Chapter?

Now that you understand the important differences between scenes vs. chapters, how do you fit the two of them together within the overall scheme of the narrative? Stephen King and James Patterson aside, is it ideal to divide the story into chapters based upon each scene’s structure? Should each complete scene be a chapter unto itself?

There is no “right” answer to this. Can a scene be a full chapter? Definitely. Does it have to be? Not at all.

Once again, the defining attributes of a scene have nothing to do with how many chapter breaks break it up. Depending on the needs of your story, the length of your scene, and your goals for the pacing, you may write a scene/sequel that spans multiple chapters.

6. Does Every Chapter Have to Be a Scene?

By the same token, not every chapter has to contain a whole scene. A chapter might contain nothing more than a single thought, as does William Faulkner’s one-sentence chapter in As I Lay Dying.

Or it might contain only a single part of a scene’s overall structure, such as, say, the character’s reaction to a previous disaster.

That said, my personal favorite approach to dividing scenes into chapters is to actually use the chapter break to divide the scene in half. I like to end chapters with the Scene Disaster, since it usually provides an excellent what’s-gonna-happen hook to keep readers reading.

This then allows me to open the following chapter with the Sequel Reaction, in which the characters respond to whatever just happened. I finish out that scene’s structure, then begin the next scene halfway through the chapter and end with another Scene Disaster.

The pattern I create looks like this:

Chapter

Sequel Reaction

Sequel Dilemma

Sequel Decision

[scene break]

Scene Goal

Scene Conflict

Scene Disaster

[chapter break]

This isn’t, of course, a hard-and-fast pattern. I’ll abandon it wherever necessary (such as when any part of the scene structure grows too long to be contained within the chapter length I’ve chosen for my story’s pacing). But it’s a good guideline for creating chapters that harmonize well with your scene structure and are primed to perform their most important job of hooking and re-hooking readers.

7. Are There Different Rules for Scene Breaks vs. Chapter Breaks?

Finally, let’s consider the difference between scene breaks and chapter breaks.

A chapter break indicates the end of one chapter and the beginning of the next.

A scene breaks indicates a shift of some sort within the middle of a chapter.

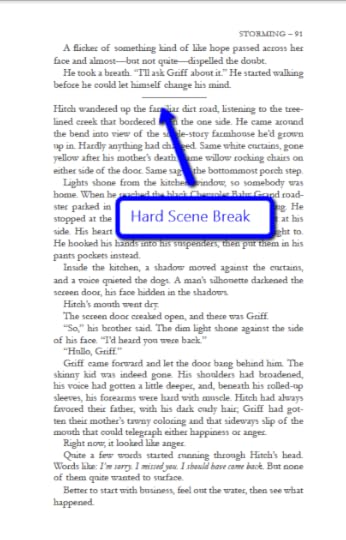

There are two types of scene breaks: hard and soft.

What Are Hard Scene Breaks?

Hard breaks are used to indicate a distinct shift within the story. This might include:

The beginning of a new structural scene unit.

The characters’ moving to a new setting.

A large jump forward in time.

A new POV narrator.

Hard breaks are usually indicated by a centered triplicate of asterisks or a short line in the middle of the page, between the paragraphs that needing splitting.

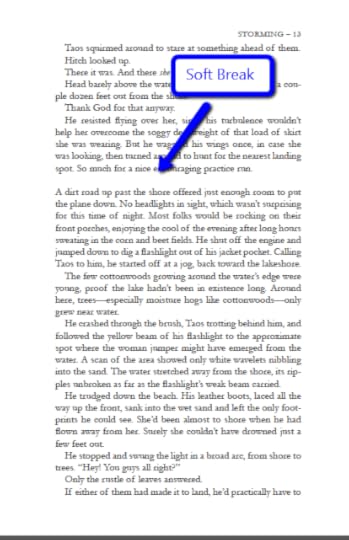

In my historical dieselpunk novel Storming, I used a hard scene break here to indicate a change in time and setting as the protagonist Hitch goes to visit his estranged brother.

What are Soft Scene Breaks?

Soft breaks are often as much as pacing trick as anything else. They serve to indicate a much smaller or less distinct shift within the story. This might include:

A minor or inconsequential shift in setting while the main action of the scene continues (e.g., the characters move from an office to the street, where they resume the same conversation).

A minor or inconsequential shift in time (e.g., “After they finished eating…”)

Soft breaks are usually indicated by only an extra space between the paragraphs that need splitting.

I used a soft scene break to skip a small amount of time as my barnstorming pilot protagonist figures out where to land his biplane after his engine dies.

What Are the Rules for Good Scene and Chapter Breaks?

As you can see, scene breaks occur at very specific moments within the story, while chapter breaks can occur just about anywhere you want them to. But the rules for executing both are the same.

Whenever you create a break of any type within your story, you must be aware of the potential for losing your readers’ focus. You combat this by creating solid hooks at each scene or chapter break.

The best way to think of a hook is simply as something that piques readers’ curiosity. Phrase the end of each chapter or scene in a way that creates even the smallest bit of dichotomy. Get readers to wrinkle their brows a little and ask themselves, What does that mean…? And, bang, you’ve got ’em! They’ll keep right on reading, regardless what kind of break they’re looking at.

***

My bet is you’re already instinctively using your chapters and scenes correctly. Don’t let the technical differences confuse you. Master them and claim them, so you can use and harmonize your scenes and chapters to create a seamless and hypnotizing reading experience.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What is your biggest challenge regarding scenes vs. chapters? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/7-questions-you-have-about-scenes-vs-chapters.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 7 Questions You Have About Scenes vs. Chapters appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 23, 2016

How to Be a Gutsy Writer: Stay True to Your Characters

Part 13 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 13 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Sometimes the greatest act of courage any person can perform is simply that of being honest. This is arguably more valid for writers than for just about anyone—and it is nowhere more valid than in being willing to stay true to your characters.

Here’s the thing about characters. They’re humans, right? Which means (spoiler!) they’re a composite of traits: neither good nor bad, right nor wrong, likable or unlikable. They’re a little bit of everything.

As writers, this realization can sometimes put us on shaky ground. We want to write characters who are both real and likable. But in allowing our characters to be real, sometimes this means letting them make choices and performs deeds that really aren’t all that likable.

That can be scary. What if, in being honest about your characters, you end up creating someone readers won’t like? Or, worse, what if the character ends up reflecting upon you in a way readers might not like so much?

Well, here’s the good news: as real as these fears may be, they’re largely unfounded. Readers like “true” characters far more than they do likable characters—and Marvel’s Captain America: Civil War shows us why.

Why Captain America: Civil War Is the Marvel Movie We’ve All Been Waiting For

Marvel has bent expectations right from the start with their interwoven cinematic universe of heroes who bounce in and out of each other’s movies. In the third, and probably final, Captain America movie, Marvel pushed this concept to the max (yes, even maxier than with Avengers). Civil War brings together almost the entire team so far (with the notable exception of Thor and Bruce Banner) into a storyline that does what the series as a whole arguably does best: interpersonal conflict.

From the moment the Civil War storyline was announced, I was stoked. It’s such a ripe opportunity for exploring characters, convictions, and painful relationships—all of which the Marvel series has in spades. Although it’s certainly not a perfect movie, the Russo brothers directorial team once again proved themselves capable of streamlining a vast amount of characters and subplots into a story that was ultimately always going to be about the face-off between Steve Rogers and Tony Stark.

I’m a Team Cap girl all the way, but I came out the theater (three times) finding myself chewing over the presentation of Tony more than any other character. When I then went back to re-watch Iron Man (which kickstarted the whole idea for this blog series), the overarching story came full circle in a way that made me feel Civil War is a culmination of the entire journey so far, the movie we’ve been waiting for ever since Marvel blasted onto the scene to the riffs of Black Sabbath.

Almost entirely, this is due to the fact Marvel was willing to be achingly honest about its beloved but incredibly flawed characters.

There really isn’t much I don’t like about this movie, save that it inevitably wobbles under its huge burden of plot and subplots toward the end and feels a little anticlimactic in a few places. It isn’t perfect, but what works for me works so well I really don’t care.

It’s hard for me to come up with a good highlight reel this week, just because, you know… everything. But here are few shout outs:

Best. Motorcycle. Stunt. Ever.

Beautifully pertinent and burningly intense subplot via the Black Panther.

Spidey. Spidey. And Spidey. (As soon as “QUEENS” blared onto the screen, I hurt my face grinning.)

And at last: sensible shoes for Black Widow.

4 Ways to Stay True to Your Characters

In trying to walk that sometimes delicate line between likable and realistic heroes, you might find yourself writing your way around honesty without even realizing it. Sometimes it’s hard being hard on our characters—because it also means being hard on ourselves.

We often want our characters to conquer, to be happy, to be worthy. They’re vicarious extensions of ourselves after all. But the irony is that when we whitewash our characters, we inevitably end up with weaker stories.

Here are four questions to ask yourself in order to double check that you’re staying true to your characters, your story, and, ultimately, yourself.

1. Who Are Your Characters?

Sometimes you will deliberately set out to write a certain kind of character. Other times, you’ll discover the character while you write him. Either way, it can be easy to lose the forest for the trees and miss out the “big picture” character you’re creating.

Sure, he’s funny, does the right thing, and generally fills out his hero shoes. But is that all he is? Western author and Wordplayer Brad Dennison describes the protagonist of his McCabe series as:

Johnny McCabe, the main character, is a gunfighter who has a moderate case PTSD from being shot at too many times. He doesn’t oil the door hinges in his house, because he wants them to squeak when they open. At night, if he hears a door hinge squeak, he knows the door is being opened. If he hears that, or even the house creaking, he’s instantly awake. He keeps a gun within reach at all times.

This isn’t heroism; it isn’t intended as heroism. It’s a traumatized man dealing with a hard past. And Brad is honest enough about his character to look past the surface trappings of the genre to recognize that and write it forthrightly.

How to Discover the Character You’re Really Writing

Step back and really examine your character. You may already know everything there is to know about him. But it’s also possible you’ll realize a few things you haven’t noticed before.

Look at his obvious flaws. What is their root cause?

Look at his obvious virtues. What is really motivating him? Ideally, your character should never be engaging with your main conflict (or, for my money, any conflict) for purely selfless reasons. So what’s his selfish reason for the good stuff he does? Now, you’re discovering who this character really is.

Once you’ve exhausted your own awareness of your story, call in backup. Ask some of your readers: What is their take on your character? Chances are excellent you’ll learn some things about your own character you never considered before.

How Civil War Was Honest About Who Its Characters Really Are

Any conflict of moral values gives you a tremendous opportunity to drill deep into the heart of the characters. The stakes go up even more when these characters are both “good guys” and the author bears zero responsibility for villainizing either one of them.

In Cap and Tony, we have arguably the two most popular characters in the entire series. Most viewers love both characters and, deep down, want to cheer for both characters. But both characters can’t both be right. They can’t both win.

Cap is a stubborn anti-authoritarian (which is an awesome bit of irony coming from an ultra-conservative, ultra-traditional character), who has a dubious personal agenda in rescuing his long-ago best friend Bucky Barnes, aka the Winter Soldier.

Tony is and has always been the most flawed character in the entire series, and the filmmakers never once shy away from this. Tony’s the “bad guy” here. Tony makes wrong decision after wrong decision for deeply personal reasons that feel like an almost inevitable outcome of his past hang-ups and mistakes. Not exactly heroic for a guy who has always been one of our heroes.

But how much better is the movie and the character development for being willing to shine a light on its characters’ dirty secrets?

2. How Have Your Characters Changed By the End of the Story?

Want to utilize one of the best ways for discovering who your character really is? Look at how she has changed—or not changed—by the end of the story. Even if your character starts out as a less-than-great person, she might prove who she really is by ending as an objectively good person who chose to do the hard right thing. Or, vice versa, she might have chosen to reject the right thing in order to cling to her own selfish or broken preferences.

The story never lies. Even when you might not entirely realize what kind of character you’re writing, the story will tell you. You can put all the pretty glitter you want on a character, but if her change proves to be negative in the story’s end, that‘s who she really is. And vice versa (which is one reason we love anti-heroes so much).

How to Figure Out How Your Character Has Changed

Ask yourself:

What negative personality traits has she overcome?

What positive personality traits has she embraced?

What positive personality traits has she rejected?

What negative personality traits has she embraced?

How has she changed physically (new clothes, straighter posture, etc.)?

What has she sacrificed along the way to gain her goals (either selflessly or selfishly)?

The character these answers reveal is the true character. This is the character you’ve been writing all book long, even if she spends most of the book acting in opposition to her ending status.

How Civil War Was Honest About How Its Characters Changed

This is Cap’s movie. There was never any doubt he was going to be the “good guy” and “win” the conflict, while Tony would be the “bad guy” and “lose.” This premise worked largely because of how it had been set up by the previous films.

Had the storyline turned Cap into someone seeking emotional revenge, the story would have been neither honest nor compelling. That’s not true to the character. Putting his friendship with a solitary wrong person above everybody else’s moral and logical arguments, that is true to his character.

The heartrending final fight in this film works largely because Tony’s actions are also utterly true to the man presented throughout his five previous films: emotionally distraught, ridden with daddy issues and regret, full of self-loathing, and obsessed with self-redemption.

The beauty of it is that Tony’s “flaws” are so utterly relatable and compelling, audiences are not distanced from him even as he makes wrong choices and tries to kill other characters we love.

[image error]

3. What Are the Logical Consequences of Your Characters’ Choices?

Often, writers will set up situations for their characters to work through just because these situations are interesting or fun for the moment. But honest writing demands we always create consequences for these situations.

If your teenage character goes for a joyride in a cop car just because you like the scene that results, that’s not good enough. The cops better show up at his parents’ door the next morning, wondering why their vehicle is double-parked outside the driveway.

The single most honest thing any writer can do is force his character to face legitimate consequences for his actions.

How to Write Logical Consequences for Your Characters

Take a good hard look at the choices your character makes. The more important those choices, the more scrutiny they deserve.

Ask yourself, in a realistic world, what negative consequences would logically result from these choices?

Then take it one step further. How can you make these consequences even more dire? The bigger the scene (e.g., is it a plot point?), the heavier the consequences should be.

Now, punish your character with these consequences. Take it as far as you can without delving into melodrama. It’ll hurt, but your story will improve in every way imaginable.

How Civil War Was Honest About the Consequences of Its Characters’ Choices

Including Tony in Civil War was a brilliant idea on so many levels, not least because it closes his arc in such a sad but honest way. As a hero within his own movies, he seemed fated by genre convention to end heroically. But because Civil War lifted him out of the context of his “own” story, it allowed for a much more honest appraisal.

As you may remember, my take on the “cornerstone” themes in the individual Marvel trilogies is that the Captain America movies are about friendships and loyalty, the Thor movies are about family, and the Iron Man movies are about self: selfishness, self-destruction, self-improvement, and the search for personal redemption.

Tony is a desperately flawed person, who has been seeking redemption in all the wrong ways. He has spent the entirety of the series trying to escape his own self-loathing and atone for his mistakes. Everything he’s done is a flamboyant gesture in an attempt to assuage his own guilt—from becoming Iron Man in the first place as a way to atone for his war profiteering, to creating Ultron in an attempt to protect the world from the threats he feels partially responsible for launching, to pushing the Accords in atonement for the deaths in Sokovia.

But no matter how hard he tries, he just can’t escape himself. That all comes home in a desperately raw and honest way in Civil War when his character finally spirals out of any semblance of heroism, forcing both Tony and the audience to face the truth about him.

4. Which of Your Character’s Actions or Attitudes Scare You?

How do you know which of your story ideas is truly honest?

Easy. It’s whichever scares you into wanting to give up writing altogether.

As my critique partner Linda Yezak wrote recently in a series of posts:

What are we afraid to write because it’s too intense and personal? Write that. Write it because it’s most relatable, because it’ll help you overcome the baggage, because your readers will realize they’re not alone. Because, if you don’t write about it… your story is shallow.

Sometimes our characters end up going to some pretty dark places—and we don’t like it. We try to steer them back to the light, back to that fun, light, happy little scene we really want to write. But that’s not honest. It’s not going to do either your character or your story justice. And readers are instinctively going to understand you’re avoiding the story’s juiciest possibilities.

How to Write Characters That Scare You

Ultimately, whatever scares you about your character is something that scares you about you. Writing is sometimes self-introspective torture. (Gotta suffer for your art, remember?)

Ask yourself:

What scares you most?

What makes you uncomfortable?

What don’t you want others to know about you?

How are these things reflected in your characters?

How are you avoiding writing these aspects of your characters?

What scenes can you create to allow you to fully explore these aspects?

How Civil War Presented Scary Characters

As far as jerks go, Tony is a deeply likable character. He’s funny, smart, unexpected, loyal, and ultimately, in his own individualistic way, upright. But if he was just a good guy with a smart mouth who pretended to be a jerk, that wouldn’t be an honest character.

In truth, a likable jerk can be one of the hardest of all characters to write. We write them because we love their their baditude, but that doesn’t mean we always like the grimy parts that create that persona.

For example, we may find Tony endlessly entertaining, but the fact remains he’s often immoral, out-of-control, and dangerous. How easy would it have been for squeamish writers or filmmakers to gloss over these less appealing aspects of his personality?

And yet if they had, we would never have gotten the intense and often cathartic honesty of Civil War, in which all Tony’s bad seeds finally bear catastrophic fruit, which he and everyone he cares about must deal with. It’s not the end we want for one of our heroes. But it’s the end we need because it’s the only end that’s true.

***

Honest characters are hard to find these days, as Hollywood churns out cookie-cutter adventure flick after cookie-cutter romance flick. One of the main reasons Marvel stands head and shoulders above just about every other franchise out there right now is that it set up difficult but compelling characters from day one—and stayed true to them every step of the way. This is nowhere truer than in Civil War.

While this isn’t my favorite of the Marvel movies, I do feel, in so many ways, it is the series’ crowning achievement. Even if the entire series made the unlikely move of careening downhill from this point forward, Civil War at least brought everything full circle in a brave and satisfying way.

Which, of course, brings us to the (temporary) end of our blog series as well. I hope you’ve enjoyed this analytical romp through one of my favorite film series as much as I have. I plan to make it an ongoing feature, so look for Part 14 in November when Doctor Strange releases. In the meantime…

Stayed Tuned: Next week, a special Wordplayer guest will give us another perspective on Ant-Man and why it demonstrates some excellent change arcs.

Previous Posts in This Series:

Iron Man: Grab Readers With a Multi-Faceted Characteristic Moment

The Incredible Hulk: How (Not) to Write Satisfying Action Scenes

Iron Man II: Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist

Thor: How to Transform Your Story With a Moment of Truth

Captain America: The First Avenger: How to Write Subtext in Dialogue

The Avengers: 4 Places to Find Your Best Story Conflict

Iron Man III: Don’t Make This Mistake With Your Story Structure

Thor: The Dark World: How to Get the Most Out of Your Sequel Scenes

Captain America: The Winter Soldier: Is This the Single Best Way to Write Powerful Themes?

Guardians of the Galaxy: The #1 Key to Relatable Characters: Backstory

The Avengers: Age of Ultron: The Right Way and the Wrong Way to Foreshadow a Story

Ant-Man: How to Choose the Right Antagonist for Your Story

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Has it ever been hard for you to stay true to your characters? Why or why not? Tell me in the comments!

The post How to Be a Gutsy Writer: Stay True to Your Characters appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 19, 2016

The Secret to Writing Dynamic Characters: It’s Always Their Fault

It’s a morbid joke among writers: we are so mean to our characters. And we love it. It’s the stuff of good stories. It’s the stuff of epic conflict. And yet, all this very important imaginative cruelty can sometimes trip us up on our way to writing dynamic characters who can, in turn, deal with this epic conflict in an equally epic and meaningful way.

It’s a morbid joke among writers: we are so mean to our characters. And we love it. It’s the stuff of good stories. It’s the stuff of epic conflict. And yet, all this very important imaginative cruelty can sometimes trip us up on our way to writing dynamic characters who can, in turn, deal with this epic conflict in an equally epic and meaningful way.

A question I’m commonly asked in interviews is: Which of your characters would you like to be for a day?

Uhh, none of them?

Honestly, that’s kind of like asking the torture master to trade places with the condemned.

My characters may be awesome and do awesome things, but have you looked at the hell they have to go through to get there? Yeah, no thanks. They can have their heroism, and I’ll just stay right here in my comfy desk chair with my trusty cattle prod and keep right on poking.

Poor characters, right? Poor victimized, helpless little dupes. Right?

Wrong-o.

This is exactly the trap writers often fall into when trying to create dynamic conflict. They make their character a victim of his horrible circumstances—and, as a result, the character himself ends up lying there on the page: inert, pitiful, alternately whiny and long-suffering, and ultimately entirely incapable of driving his story’s conflict.

Yes, You Do Have to Be Mean to Your Characters

Now, before I proceed, let me just stop and stress something to the kind-hearted among us: yes, you really do have to mean to your characters.

Some writers revel in this (*raises hand*); others find their dislike of conflict in real life makes it difficult to create it on the page. Makes sense, after all. You create these people you love—people who are always extensions of yourself to some extent. Why would you want them to suffer?

Because you want to write an interesting story, that’s why.

Stories about what James Scott Bell calls “happy people in happy land” are numbingly boring. They aren’t stories, because nothing happens. There is no conflict because the characters aren’t encountering obstacles to their goals.

Those obstacles can be relatively slight inconveniences (red lights on the way to work), or they can be terrifying disasters (hurricanes, murders, imprisonments, betrayal, you name it). Both will move your story, and your choice of how cruel you will be to a character will always depend on the needs of the story.

But if you’re not pulling out the stops somewhere in your story, then you need to ask yourself if you’re really exploring your character’s potential. This doesn’t mean you have to introduce a serial killer into your cozy hamlet tale. But you do need to examine your character.

Find out what her weak spot is. What is she most afraid of? Usually this will tie back to the Ghost and Lie you’re using in her character arc. This is not just a general misfortune; this is something very specific to this character and her inner journey.

Are you exploiting that fear? Are you using it to bring your character to her knees?

If not, you’re almost certainly not being mean enough.

Hold That Thought: You Don’t Have to Be Mean to Your Characters

Now that we’ve established your characters most definitely need to suffer, let’s take a step back and look at this from a totally different angle.

You do not have to be mean to your characters.

In fact, it’s best if you stop thinking in terms of anyone in your story being mean to your character.

But… what about the evil bad guy who has the hero locked on the rack? He’s pretty mean.

True. But is it the evil bad guy’s fault your hero is on the rack?

Is your hero 100% innocent? Was he nabbed from the local village to be made a random example to the rebellious serfs? Is he a guiltless victim?

If the answers are yes, that undoubtedly makes him seem like a pretty good guy. But it also makes him a pretty boring and lifeless protagonist.

Here is the single most important thing to understand about your protagonist’s suffering: He must always be responsible.

What? You mean, he volunteered to be tortured?

Probably not. (However, do stop to think about how much more interesting that angle makes the above scene.) But he did do something that created the situation he’s in now.

Maybe he’s a serf himself—and he chose to rebel, even knowing what the punishment would be should he be caught.

Maybe he is innocent of the rebellion, but he chose to take blame in order to protect his guilty son.

Maybe he knew there was a rebellion underway in the southern villages, but he chose to travel through in a desperate hope of getting medicine for his dying wife.

Maybe he was just passing through, minding his own business, but when confronted with a random cruelty from the local lord’s guards, he chose to stand up for the poor peasant.

See what’s happening here? This is not a passive character. This is a character who is making choices.

Not only is he personally responsible for driving the plot, he’s also personally responsible for the consequences. His own choices—whether right or wrong—are what have put him in this fix. This raises infinitely more interesting thematic explorations than those you’d find if your hero were the entirely undeserved victim of someone else’s choices.

Catalytic, Not Catatonic: 5 Steps to Writing Dynamic Characters

Dynamism, by its very definition, is about forceful movement. In writing dynamic characters, you are writing characters who drive events. They are causes that create effects. In short, they are catalysts. What they are not is catatonic. They are not passive rag dolls, tossed around by random antagonistic forces.

The best news for you is that these catalytic characters are a blast to write. Consider five immediately applicable ways you can take your character from victim to overcomer.

1. Make Your Character Knock Down the First Domino

It’s true your antagonist controls the overall conflict (which is why it’s often best to begin your plotting by examining the antagonist’s goals, rather than the protagonist’s). This means your antagonist gets to make the first move on the chessboard. This does not mean, however, that the antagonist’s first move victimizes the protagonist.

Even if the antagonist’s move immediately affects the protagonist in an undesirable way, the protagonist must still actively make a choice that engages him in the rest of the plot. The antagonist may have knocked over the first overall domino. But the protagonist must knock over the first domino in his personal involvement in the conflict.

This usually happens at the Inciting Event, the turning point halfway through the First Act at the 12% mark. This is the Call to Adventure, where the protagonist first brushes the main conflict. Usually, he will start out by rejecting it in some way. He doesn’t want to engage with the conflict. Often, this very avoidance of his destiny puts him on the road to meeting it anyway. He makes a choice, for which he is responsible and which puts him on an inevitable collision course with the antagonist force.

For Example:

In Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games, Katniss Everdeen chooses to take her sister’s place in the Reaping. Consider how vastly more interesting a story we have thanks to her having to choose to take part in the Hunger Games—instead of being randomly reaped herself.

Katniss is a dynamic character, because she is not a passive victim of her circumstances. She actively chooses to take part in the Hunger Games, in order to prevent her younger sister Primrose from being “reaped.”

2. Knock Your Character Down, Then Make Him Choose Again

Although your character’s initial choice to engage with the conflict will ultimately be the cause for everything that follows, you can’t stop there. Many authors will set up their character’s involvement with the antagonistic force by hitting the character as hard as they can, knocking her to her knees—and then leaving her there. Scene after scene occurs in which the character is buffeted by trial after trial. And she just takes it.

The patience of Job is not what we’re looking for in a protagonist. When your character gets knocked down, she can’t just stay down. She must make an active choice.

Even if that choice ends with her getting knocked down again (and, frankly, I hope it does—especially in the first half of the book), she must continue to move proactively through the story, choice after choice after choice. Her choices are what cause the next round of getting knocked down—until eventually, she starts learning how to make better choices and stops getting beat up so often.

For Example:

In Diana Wynne Jones’s Howl’s Moving Castle, Sophie chooses (however reluctantly) to lie to the king about Howl, in an effort to get him excused from employment. The scene goes entirely sideways when she inadvertently shows her true beliefs about Howl’s goodness and capability. But the result of both her presence before the king and her inability to hide her growing love for Howl are both the result of her own choices.

In Howl’s Moving Castle, Sophie reluctantly talks to the king on Howl’s behalf. However, despite her reluctance, she remains a dynamic character because her action is still entirely her own choice and the results are the consequences of her own actions.

3. Make Your Character Culpable

When your character gets himself stuck in a horrible situation despite having done only the right thing with the best of intentions, it can sometimes be hard to paint him as anything but a victim.

But what if he’s not so innocent after all? What if his own culpability for a downright wrong decision, either early in the book or somewhere in his past, means he actually deserves some of the horror he’s being hit with?

In their desire to make characters as likable and “good” as possible, authors often fail to explore this possibility. But nine times out of ten, dashing a little gray into your character’s choice will make both him and his conflict vastly more complex and interesting.

Consequences are the most interesting thing in fiction. The more deserved those consequences, the more interesting they become.

For Example:

Erstwhile assassin Jason Bourne is a tremendously likable character. He’s obviously a good man, just as he has obviously been the victim of tremendous desecration to his body, mind, and soul. In many ways, he is not truly responsible for the murders he was brainwashed into performing. And yet… he made the choice to “commit himself to the program.” Even though he can no longer fully remember it, he knowingly chose to allow himself to become a lethal tool in the hands of men with (at the best) dubious ethics and motives. At the end of the day, it’s all his fault. He knows it. We know it. And his suffering is all the more poignant for it.

Even though Jason Bourne is undeniably a victim in some ways, he remains a powerful and dynamic character in large part because he is ultimately responsible for having chosen to be turned into an assassin.

4. Let Your Character Make Both Good and Bad Choices

As your story progresses and your character makes choice after choice that knocks over domino after domino in your story’s plot, you will want to vary the types of choices she makes.

Just because she’s the smart, brave, righteous good guy doesn’t mean she should always make the right choice. Mix things up. Let her make some righteous decisions. Let her make some morally problematic decisions. Let her make some smart decisions, but also let her make some poorly informed decisions. As Geoff Johns says,

The characters that have greys are the more interesting characters. The hero who sometimes crosses the line and the villain who sometimes doesn’t are just much more interesting.

You need a balance of both in order to keep readers believing in your character’s goodness and intelligence—while still allowing them to explore the fascinating ramifications of her fallibility.

For Example:

In Sergey and Marina Dyachenko’s fantasy fable The Scar, hubristic young nobleman Egert Soll makes bad decision after bad decision, starting with two ill-fated duels, one of which ends with his killing an innocent student and the other of which ends with his being scarred and cursed in recompense for his heedless cruelty to others.

In The Scar, protagonist Egert Soll brings a wretched fate down on his own head thanks to his own misguided choices and decisions.

5. Allow Your Character to Take Responsibility as Part of His Journey

Even though your character will be at least partially culpable for everything that happens to him, he won’t necessarily recognize this. In fact, he may very well rage against the heavens, declare himself a victim, and insist he doesn’t deserve anything that’s happening to him.

Although I would caution against laying on the self-pity too thick, you do want to let your character experience a progression of revelations, leading him to the ultimate choice of taking responsibility for his life in the Third Act.

Ultimately, all character arcs come down to this central Truth—we’re all responsible for our own lives—no matter what specific Lie your character is struggling with. As such, his ability to take responsibility for the consequences of his own actions needs to be an evolution.

For Example:

In Jane Austen’s Emma, Emma Woodhouse comes to the Third Act revelation that her actions have been selfish and misguided—and have very likely cost her the love of the noble Mr. Knightley. This revelation is the central revelation of both the plot and her character arc. In its aftermath, she chooses to take responsibility for her actions, both proactively and retroactively.

Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse only gradually comes to realize how her choices have affected others—and herself—over the course of the story and her own personal evolution.

Themes of responsibility and consequences are inherent in all stories. The more adamantly you claim them and force your character to face them, the stronger your story will become. Even better, you’ll learn how to begin writing dynamic characters who electrify readers.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How have you gone about writing dynamic characters in your story? What choices do they make that reap important consequences? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/secret-to-dynamic-characters.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post The Secret to Writing Dynamic Characters: It’s Always Their Fault appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 16, 2016

How to Choose the Right Antagonist for Your Story

Part 12 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 12 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

What’s the secret of how to choose the right antagonist for your story? If you’re thinking it’s probably a little more complicated than simply making him a “bad” guy who’s out to get your protagonist, you’re definitely on the right track.

In fact, how to choose the right antagonist will influence everything about your story—from the coherency of its plot to the quality of its conflict to the focus of its theme.

In short, who will fill the role of your story’s antagonist is never a decision to be taken likely. Make the wrong decision and it could derail your story. Make the right decision, and it could be the key to making your entire book just click.

Today, let’s examine the qualifications of how to choose the right antagonist for your story.

Ant-Man: The Little-Big Addition to the Marvel Universe

Welcome to the twelfth installment in our serial exploration of the good and the bad in the Marvel movies. In light of that exploration, I find Peyton Reed’s Ant-Man a singularly interesting addition to the Marvel movies. For me, it’s a middle-of-the-road movie within the series, not so much because it’s a mediocre film as because my every reaction to it has an equal and opposite reaction to balance it.

It’s a unique film within the comic book genre: more heist than superhero.

And yet… it also packs very few surprises, hitting the beats of its various storylines (heist, redemption, protege vs. mentor, superhero origin) mechanically and without much irony or subtext.

It’s big, bold new addition to the series, bringing in the first of an entirely new set of heroes—charmingly funny and earnest antihero Scott Lang.

And yet, it somehow feels small in comparison to the previous heroic entries of Tony Stark, Thor, and Steve Rogers. Scott’s an add-on to the team, not a founding member—and it feels that way.

It throws in the unique twist of sidelining original Ant-Man Hank Pym as the mentor character, which gives audiences, in essence, two Ant-Mans for the price of one.

And yet, in doing so, it misaligns the conflict with its main antagonist, Darren Cross—Hank’s one-time protege and the rogue leader of his company.

And this is why Ant-Man offers a unique opportunity to study how to choose the right antagonist for your story. Objectively, Cross is the wrong antagonist for this story—and yet the story still makes it work.

Let’s take a look.

The 4 Qualifications of How to Choose the Right Antagonist

Want an antagonist who will help you take advantage of every aspect of your story? All you have to do is double-check him against the following four-part checklist.

1. The Antagonist Directly Opposes the Protagonist in the Plot

Let’s do a quick refresher on what an antagonist actually is. Boiled down to the lowest common denominator, an antagonist is nothing more or less than obstacle between your protagonist and his goal.

As such, the right antagonist will always be directly opposed to your protagonist. He won’t stand off to the side of the road, taunting the protagonist or throwing rocks at him. Nope, he’ll be the guy right smack in the middle of the road, pointing a gun straight at your protagonist’s head and telling him to stand down or it’s curtains.

If he’s not in the middle of the road, then he’s not the main antagonist (and/or whatever is at the end of that road is the wrong goal for your protagonist to be pursuing in the main conflict).

How to Choose the Right Antagonist to Oppose Your Protagonist

Ask yourself:

What is your protagonist’s main plot goal?

What is the Thing Your Character Wants?

What character (or thing) is best suited to get in his way?

How can this character (or thing) directly oppose your protagonist’s scene goals along the way?

What character (or thing) will your protagonist have to confront in the Climax?

Does Ant-Man‘s Antagonist Oppose Its Protagonist?

Ultimately, Cross is the wrong antagonist for Ant-Man simply because Scott Lang is the wrong protagonist. Granted, it’s kind of a chicken-and-egg problem. But the bottom line is that if Scott Lang is your protagonist, you must choose an antagonist directly opposed to his goals—and not Hank Pym’s.

In short, the choice of Cross as the main antagonist tells us this is really Hank Pym’s story, even though Scott is clearly set up as the protagonist.

Assuming, we want Scott as protagonist (which we obviously do), then a more appropriate antagonistic choice for him would be one that directly opposes his goal of staying clean, earning money, and regaining visitation rights with his daughter. Cross ends up opposing these goals, but only incidentally through Scott’s relationship with Hank.

2. The Antagonist Directly Opposes the Protagonist Thematically

The antagonist is a central cog in the wheel of your theme. Because he drives the external conflict—which is a visual metaphor for the protagonist’s inner conflict—he and the conflict he creates must be directly pertinent to the theme.

Now, granted, every character within your story should reflect upon some aspect of your theme in one way or another. But the main antagonist must be a direct commentary on your thematic premise. If he’s off chasing some other Lie or Truth—or even just a thematic blank—a crucial part of the thematic equation will be missing from your protagonist’s arc.

Alternatively, if the antagonist is not directly opposed to your protagonist in the conflict, then it doesn’t matter how thematically pertinent he is. His impact on the story simply won’t be as vital, because the protagonist’s personal discoveries won’t be directly connected to overcoming this external antagonist.

How to Choose the Right Antagonist to Thematically Oppose Your Protagonist

Ask yourself:

Does this character start out either

believing basically the same Lie as the protagonist?

believing a Truth contrary to the protagonist’s Lie?

Is this character painfully similar to the protagonist in some ways?

Is this character an example of either

someone the protagonist would desperately like to be?

someone the protagonist desperately wants to avoid being (or perhaps already is)?

Will this character be able to offer convincing thematic arguments with the potential to seduce the protagonist away from the story’s Truth—and, as a result, away from his story goal?

Does Ant-Man‘s Antagonist Thematically Oppose Its Protagonist?

There isn’t a ton of thematic depth in this movie, but what there is all revolves around parent/child relationships. Scott’s relationship with his loving, trusting daughter is one example. In this, he is following a similar path to Hank’s: except Scott succeeds in fulfilling his daughter’s trust, whereas Hank failed long ago with Hope after his wife’s death.

So far so good. Except… the antagonist Cross isn’t in a parental role. He’s in the child role, as resentful toward his former mentor Hank as is Hank’s daughter Hope. Cross certainly contributes to the theme, but his contributions relate more directly to Hank’s journey than to Scott’s. If Scott gets anything at all out of Cross’s insistence that Hank was a lousy father figure, it affects his own evolution only incidentally and subtextually.

3. The Antagonist Is a Mirror for the Protagonist

As part and parcel of the antagonist’s thematic role, he needs to offer a jarring funhouse reflection of the protagonist. He is a representation of the protagonist’s dark side—of his Lie. Perhaps he is an omen of the protagonist’s future fate, or a consequence of the protagonist’s past choices, or a revelation of who the protagonist might have been in a different life.

The antagonist is almost always a “negative impact character,” one who influences the protagonist’s journey toward the light by forcing him to face the power of the Lie’s darkness. The more striking the similarities between these vastly different characters, the more opportunities you’ll have to explore and develop your theme.

How to Choose the Right Antagonist to Mirror Your Protagonist

Ask yourself:

What character best represents where the protagonist will end up if he takes the wrong path?

What character best represents where the protagonist wants to end up externally?

What character shares a similar backstory journey with your protagonist?

What character represents or shares similarities with your protagonist’s greatest failures to date?

Note that it’s not vital for your antagonist to represent the answer to all of these questions, but he should ideally be able to fulfill at least one of them.

Is Ant-Man‘s Antagonist a Mirror for Its Protagonist?

This is probably the one qualification Cross best fulfills for Scott, in that both are proteges of Hank Pym. Cross represents the dark potential of Scott’s relationship with Hank (and, also, much less directly, of the dark potential within Scott’s own relationship with his daughter if he fails her).

However, Cross is, by far, a better reflection of Hank than he is of Scott. Both are brilliant scientists. Both are ambitious and consumed with their discoveries. Both have invented shrinking suits, designed for warfare. Cross, in short, is Hank’s darkest self realized—made all the more poignant for Hank by the fact that he essentially created Cross.

4. The Antagonist Creates Obstacles for the Protagonist From the Start

In order to create and maintain a cohesive overarching narrative within your story, you must first have a cohesive and overarching conflict. That only happens when you have a main antagonist who is in position to oppose your protagonist’s main goals from page one (even if he doesn’t immediately reveal himself).

Even if your protagonist maintains a consistent plot goal throughout, if he is opposed by first one antagonist and then another, the consistency of both conflict and theme will suffer from the jerkiness.

It’s very possible both your protagonist and your antagonist will begin your story knowing nothing about each other. But they will still be obstructing each other, from the very beginning, in ways they won’t understand until a little later in the story. When the characters (and the readers) look back on your story, they should be able to see the main antagonist was in play from the very beginning, in one way or another.

How to Choose the Right Antagonist From the Start

Ask yourself:

What antagonist will be present in the Climax’s final confrontation?

How can this antagonist be the major opposing force against the protagonist at all of the major structural beats?

How can this antagonist be set up as an obstacle (or the inevitable potential for an obstacle) from the very first scene?

How will the protagonist “brush” against this antagonist’s power in the Inciting Event?

How will this antagonist drag your character into the main conflict at the First Plot Point?

Does Ant-Man‘s Antagonist Oppose Its Protagonist From the Start?

The short answer is: no. Protagonist Scott gets out of prison with the big story goal of reuniting with his daughter, for which he must earn money and stay out of trouble. His obstacles have everything to do with his criminal past and nothing whatsoever to do with Cross’s determination to create a functional Yellowjacket suit.

Scott’s conflict finally touches Cross’s when Hank recruits Scott to help him steal the Yellowjacket suit. But even then, Cross remains only a vague obstacle to Scott’s personal goals. Scott has no personal investment in opposing Cross—which robs their final showdown in his daughter’s bedroom of much of the personal power it might otherwise have wielded.

Once again, it is Hank who is directly opposed by Cross—on every possible level: professional, personal, practical, and thematic.

Why We Like Ant-Man Anyway

Did Ant-Man choose the wrong antagonist and/or protagonist? Without question.

Would it have been a better movie had it chosen an antagonist more suited to directly oppose Scott Lang? Definitely.

But, happily for us, it’s also an example of how, even when a story bombs on such an important element, it can still salvage itself through overall charm. This may not be a super-strong movie, but it’s still an utterly likable movie, driven by an utterly likable hero with an utterly relatable motive.

At the end of the day, those things are almost always more important than the finer points of antagonism and conflict. But just think how much more awesome your story can be if it gets all of that right, including finding the perfect antagonist for its specific conflict!

Stay Tuned: Next week, we’ll talk about why Captain America: Civil War‘s gutsiest move was portraying its characters with honesty.

Previous Posts in This Series:

Iron Man: Grab Readers With a Multi-Faceted Characteristic Moment

The Incredible Hulk: How (Not) to Write Satisfying Action Scenes

Iron Man II: Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist

Thor: How to Transform Your Story With a Moment of Truth

Captain America: The First Avenger: How to Write Subtext in Dialogue

The Avengers: 4 Places to Find Your Best Story Conflict

Iron Man III: Don’t Make This Mistake With Your Story Structure

Thor: The Dark World: How to Get the Most Out of Your Sequel Scenes

Captain America: The Winter Soldier: Is This the Single Best Way to Write Powerful Themes?

Guardians of the Galaxy: The #1 Key to Relatable Characters: Backstory

The Avengers: Age of Ultron: The Right Way and the Wrong Way to Foreshadow a Story

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How did you decide to choose the right antagonist to directly oppose your protagonist throughout your story? Tell me in the comments!

The post How to Choose the Right Antagonist for Your Story appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 12, 2016

The Only 5 Ingredients You Need for Story Subtext

If there’s a magic ingredient in writing, it’s story subtext.

If there’s a magic ingredient in writing, it’s story subtext.

It’s actually not magic, of course, any more than any of the other demystified techniques of structure, theme, or character arc. But story subtext often seems like magic simply because, by its very nature, it is the execution of the unexplained.

Subtext is supposed to be invisible. It lives in the shadowy underworld beneath our words. It’s the hooded figure whisking around the dark corners of our stories, the mysterious clockmaker greasing gears behind the scenes, the phantom in our opera.

Just the very mention of subtext gives me delicious chills. A few years ago, I came to the revelation that all of my favorite stories had one very specific thing in common: subtext. All of them were stories that were about far more than what they appeared to be on the surface. They were all stories that invited me, as the reader or viewer, into the misty netherworld of the story to ask questions about characters and situations, to fill in blanks, to come to conclusions, and to broaden my experience of both the stories and my life.

Good story subtext allows readers to observe and learn without being taught. Subtext tells readers the author trusts them to understand the story and the characters without needing to have everything pointed out to them.

In short, story subtext = awesomesauce.

Why Story Subtext Is So Difficult to Master

So there I was—a total convert to the importance of story subtext. I even wrote a post about how you must put subtext into your stories. But then the inevitable queries starting coming in:

How do I create subtext in my story?