K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 54

October 31, 2016

4 Ways to Write Backstory That Matters (How to Outline for NaNoWriMo, Pt. 5)

There are two equally vital parts to any story: the part you see and the part you don’t. The context and subtext. The story and the backstory.

There are two equally vital parts to any story: the part you see and the part you don’t. The context and subtext. The story and the backstory.

Whether you’re trying to figure out how to outline for NaNoWriMo (only one day away!) or just needing a game plan for your next work-in-progress, one of the most important considerations will always be backstory.

Backstory isn’t always something we consider when talking about novel outlines. It’s not, strictly speaking, part of the story. It’s just stuff that happened in the character’s past. It’ll show up naturally when the time is right. No need to explore it before you start writing, in the same way you do the main plot.

Right?

Well, that’s not necessarily wrong, but it is a mindset that can lead to a lot of missed opportunities.

Backstory will influence everything that happens in your main story—from the plot events to the characters’ motivations to your ability to manage your thematic subtext.

In short, it’s important. That being so, it’s definitely something to consider in your outline.

4 Ways to Discover Backstory That Actually Matters to Your Plot

It’s the story before the story. It’s everything that happened in your character’s past. It might even include his parents’ pasts, insofar as they have impacted the character himself, his childhood, his choices, and the life that has made him who he is when readers discover him in the Normal World of your story’s First Act.

Everything that has ever happened to your character will influence the person he is. But does that mean every little bit of is important? Every childhood baseball game, every zit in high school, every job interview?

This is an easy pitfall to fall into. You’re supposed to discover your character’s backstory, so you sit down and start writing about all the stuff that happened to him. But, frankly, most of that = snore.

The only backstory that matters is the backstory that influences the main story.

If your character suffered a brain injury after being hit in the head with a baseball, then his childhood games are important to his backstory. But if he just liked baseball? Nope, probably not going to be important enough to bother outlining, much less including in your story.

So how do you decide which parts of your character’s past are important? How do you create a backstory that is not only interesting, but that actually brings depth and weight to your main story?

There are only four questions you need to ask yourself to find your story’s best possible backstory.

1. What Brought Your Character to the Beginning of Your Main Story?

First, consider your character’s physical surroundings upon his entrance into the story. What brought him here? There are two different sides to this, which may or may not both apply to your character’s situation.

What Brought Your Character Here Purposefully?

What reason does your character have for being present when the main conflict kicks off in your story’s Inciting Event? Was he aware of the coming conflict prior to its initiation with the other characters? Did he have a desire and/or goal that prompted him to want to engage with the conflict? Or perhaps he wanted to try to stop it?

Either way, if the character has a conscious reason for being present when the conflict begins, there’s always going to backstory behind that. What brought him to this point? What made him aware of what was happening?

For Example: In my dieselpunk/historical novel Storming, the biplane-pilot protagonist Hitch Hitchcock enters the sphere of the main conflict when he returns to the Midwestern home he fled years earlier. There is important backstory both in his initial reasons for having left home (the law was after him) and his decision to finally return (he needs to win the big airshow that has come to town).

For Example: In my dieselpunk/historical novel Storming, the biplane-pilot protagonist Hitch Hitchcock enters the sphere of the main conflict when he returns to the Midwestern home he fled years earlier. There is important backstory both in his initial reasons for having left home (the law was after him) and his decision to finally return (he needs to win the big airshow that has come to town).

What Brought Your Character Here Physically?

Your character may also be an unwitting participant in the initial conflict. She’s walking along, rather clueless, just minding her own business—when, wham!, the conflict sticks out its foot and trips her. But she had to have a reason to physically be in this particular space. Why is she here? What (seemingly?) unrelated goal is she pursuing that serendipitously leads her to this particular place at this particular time?

If you’re allowed one major coincidence in your story, this is it. Still, it’s best if you can come up with solid cause-and-effect for why your character just happens to be in the wrong place at the wrong time (or perhaps it’s the right place at the right time?).

For Example: In Storming, Hitch first brushes the main conflict in the Hook in the first chapter when two people fall out of the clear night sky right in front of his biplane. The immediate backstory answers the question of why he happens to be out there flying around in the dark (testing a modification on his plane), as well as why these two falling people are out there (SPOILER!).

2. What Is Your Character’s Motivation?

Arguably, the most important discovery you can make in outlining your backstory is that of your character’s motivation. What does he want in the plot? What is the Thing He Wants from life? And what related goal is powering him through the main plot?

And, most importantly of all, why does he want it?

Think of backstory as the cause to your main story’s effect. If the main story is the what, the backstory is the why.

This is a crucial pairing. It is was creates the illusion of realism within your story world. Without this all-important motivation in your character’s backstory, the verisimilitude of the story falls apart. In real life, people never pursue things without reasons. We get up to get a drink of water because we’re thirsty. We buy someone a gift because we love them. We rob banks because we’re poor… or greedy… or adrenaline junkies. There’s always a reason.

In stories, character motivation can manifest in one of two ways:

Motivation From Within the Story Itself

Sometimes, your character’s motivation will arise from within the story itself. He becomes paralyzed at the First Plot Point, which initiates a motivation and a goal he never had to even think about prior to this event: learn to walk again.

But even in these instances, it’s best if the character’s new goal is grounded in a deeper reason within his past life. Indiana Jones has no goal or motive to pursue the Ark of the Covenant until he learns of its existence, but his reasons for being in a position to go after it—the reason he is an archaeologist/adventurer—are deeply rooted in his existing life and (as we discover in The Last Crusade) his childhood relationship with his father.

Indiana Jones’s motivations for becoming an archaeologist go all the way back to his childhood, as we finally discover in his backstory in The Last Crusade.

For Example: In Storming, Hitch meets one of the people who fell from the sky—the mysterious and unpredictable young woman Jael—and agrees to help her return to what she insists is her home in the sky. Prior to meeting her, this goal was nowhere on his radar, but his motivation is grounded in both his preexisting goal of winning the airshow (Jael agrees to wing walk in his act as part of the deal) and out of his own longstanding, if conflicted, relationships with people (wanting to help them, but afraid of getting tied down—which is why he left his hometown all those years ago).

Motivation From the Character’s Past

Your character’s primary motivation for pursuing the main story goal may also be deeply rooted in events that happened prior to the beginning of the book itself. Almost always, you will want the Lie the Character Believes, which is at the heart of both the character arc and the theme, to be rooted in his past life (see the next section’s question about the Ghost). But the goal itself may originate prior to the story, only to be complicated as he engages with the obstacles of the main conflict in the Inciting Event and First Plot Point.

If this is so in your story, ask yourself: Why did the character first conceive this goal? What prompted him to want it? What’s his motivation? What prompted him to transform his desire into action?

For Example: In Storming, Hitch starts the story with the existent goal of winning Col. Bonney Livingstone’s famous air competition, so he can earn enough money to start his own air circus. This is the Thing He Wants, which provides the frame for his actions throughout the entire story, even before he gains his main story goal of helping Jael.

3. What Is Your Character’s Ghost?

What creates character motivation within your story? Even more to the point, what creates a character motivation that is pertinent to your main conflict?

Look no farther than the Ghost.

The Ghost is the single most important event that has happened in your character’s life prior to the main story. In some ways, it’s even the reason the main story is happening at all. If you know nothing else about your character’s backstory, at least know the Ghost. It will influence every decision you make about your story, from character motivations to plot goals to thematic principles.

The Ghost is the wound in the character’s backstory. It is the reason he clings to the Lie He Believes. It can be something deep and dark (such as the murder of a loved one) or it can be comparatively small and normal (such as a disapproving parent). Whatever it is, it’s at the root of your character’s motivation and, by extension, the Thing He Wants and his very plot goal.

The Ghost is what ensures your backstory is not a random history attached to your character just to make him seem more “rounded.” The Ghost is integral to the main story. It is what creates your character’s subtext. Fail to understand your story’s Ghost—or, worse, fail to give your character a backstory Ghost that actually matters to the main conflict—and you will lose the all-important cause to your story’s effect.

For Example: In Storming, Hitch’s Ghost is his broken relationships with his family—his dead wife, his wounded brother, and his embittered sister-in-law. He wants his remaining family to understand why he had to leave (because a corrupt sheriff was on his tail), but he’s still hung up on his own fear that responsibility and relationships will destroy his independence.

4. Which Backstory Revelations Will Advance the Plot?

Once you’ve explored the above questions and gained a complete view of your character’s past, why she is the way she is, and what will make her react to your main conflict the way she will—your final step is to figure out how you can also use all this juicy backstory stuff to power the main plot.

At its simplest, backstory will provide only the necessary context for your character’s motivations. But you can up the ante by using the backstory itself to power the plot through discoveries and reveals.

What can your character discover about her own past that will move the conflict? What can she discover about other characters’ pasts? What can other characters discover about her past? And what can be revealed to readers at strategic moments that will pull them deeper into the story?

Write a list of all the juicy stuff you’ve discovered in your character’s backstory. Now consider: how can you use these things to create mystery and to pull readers along? Instead of simply telling readers all about the backstory upfront, how can you uncover it, bit by bit, at strategic moments throughout the story, in a way that advances the plot?

You know something advances the plot when it changes the conflict. Its revelation either allows the character to move forward in informed ways, or it throws up obstacles she must then figure out how to overcome. This is backstory’s most delicious role in any story.

For Example: In Storming, Jael’s mysterious origins are only slowly doled out throughout the story. As Hitch discovers more and more about her backstory, he is drawn deeper and deeper into the main conflict of helping her get home before her pursuers can destroy his hometown.

A Warning About Priorities: Don’t Get Too Infatuated With Your Backstory

Brainstorming backstory is always one of my favorite parts of the outline. You never know what intriguing possibilities you will discover in your characters’ pasts. Often, you will learn things you would never have guessed, and which will then take the story in exciting new directions.

But don’t get too carried away.

I receive more questions about backstory than I can count, and most of them are from authors who either

a) have more backstory than they know how to use

-or-

b) are so in love with their backstory, they’re determined to use every last bit of it, at the expense of the main story

It’s important to note backstory is not your story. It is only a tool to advance the main story. It is almost always at its most powerful when used with restraint, when it is allowed to remain largely subtextual.

Some writers end up writing pages upon pages (tens of thousands of words, even) about their backstories. Nothing wrong with that, but always remember backstory’s purpose within your story. Don’t allow yourself to become so infatuated with your characters’ pasts that you allow them to overshadow the all-important present in your main story.

When the time comes to sow your backstory into your main story, remember this rule of thumb: Only share backstory if and as it becomes necessary to either advance the main plot or allow readers to understand what’s happening.

Now have fun digging into your characters’ fascinating pasts!

Stay Tuned: Next week, we’re going to talk about how to weave all of your story pieces together into a cohesive whole.

Previously in This Series:

Should You Outline Your Novel?

Start Your Outline With These 4 Questions

3 Steps to Find the Heart of Your Story

How to Find and Fill All Your Plot Holes

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How will your protagonist’s backstory affect the main plot? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/4-ways-to-find-backstory-that-matters-nanowrimo-guide-to-outlining.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 4 Ways to Write Backstory That Matters (How to Outline for NaNoWriMo, Pt. 5) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 28, 2016

How to Properly Motivate Your Bad Guy

No character is more misunderstand than the bad guy. Even today, it’s far too easy for authors to slip into the remnants of the old melodrama stereotype—black cape, twirled mustache, trick laugh. He’s the bad guy just because… well, he’s bad. Isn’t that enough?

Definitely not enough.

Next to your protagonist, your antagonist is the single most important character in your story. Skimp on him, and the entire story—including the protagonist—will suffer as a result.

Now, it’s true not every story will require a “bad” guy. An antagonist doesn’t have to be bad.

Doesn’t even have to be human, come to that.

The antagonistic force is nothing more or less than an obstacle between your protagonist and his story goal.

But, as often as not, this character will be bad. He may be aligned only a little to the moral south of your protagonist, or he may be a dyed-in-the-wool, raving, slasher-scary psychotic killer.

Either way, it’s your job to make sure he’s still a dimensional human being. This may or may not mean he’ll end up being sympathetic to readers in some way. What it does mean is that your bad guy must have realistic motivations for his actions.

Let’s take a quick look at how to motivate your bad guy—and how not to.

Why the Bad-Just-to-Be-Bad Antagonist Doesn’t Work

Bad guys are often conceived simply to give the protagonist someone to overcome—someone to run from or fight against. As archetypal black-hat figures, bad guys don’t always have to be complicated, but be wary of oversimplifying them.

When you create a bad guy who has no clear goal other than kill the good guy, and no clear motive other than just because I’m bad, several not-so-great things happen:

Your antagonist turns into a one-dimensional cardboard cutout.

Your antagonist lacks realism.

Your conflict lacks realism.

Your protagonist’s struggle lacks meaning and depth.

In short, you may think that in making your villain as evil as possible “just because,” you’re making him all the scarier and more impressive. But the result is exactly the opposite. The entire story and its thematic argument weakens.

Consider Gavin O’Connor’s western Jane Got a Gun, in which Ewan McGregor chews through the scenery as John Bishop, the villainous leader of a ruthless outlaw gang—who is dead-set on annihilating protagonist Jane and her husband Bill Hammond.

Ewan McGregor squints devilishly, huffs cigar smoke at everybody, and twirls his period mustache–but the writers forgot the most important thing: you must motivate your bad guy.

On the surface, he has a nominal motivation: after he tried to force Jane and her daughter into prostitution, one of his men, the kindly Hammond, rescued Jane, shooting up Bishop’s brothel and killing several of his men in the process. Granted, such a thing would be a little galling to a businessman such as Bishop, but is it logically enough to cause him to obsessively hunt down Jane and Ham for the next six years?

The character is introduced in a supremely evil characteristic moment—garroting an innocent man to death, while trying to extract info about Jane.

Shiver.

But… why?

He’s even got a reward out on these people. Putting his money where his mouth is but… why?

Why is he so obsessively, and ultimately self-destructively, determined to exact revenge on two people who were, at best, minor annoyances in his overall scheme?

Any number of suitable motivations might have been created to account for Bishop’s obsessive evil. Any one of them would have made him a far more compelling antagonist, and the conflict itself far more meaningful and realistic.

As it stands, he becomes a one-dimensional stereotype—a bad guy who is present in the story for no other reason than to simply be as bad as possible.

How to Properly Motivate Your Bad Guy

People never do things without reason. Good people can have bad reasons for their actions, just as bad people can have good reasons. At the very least, even the most wicked of men committing the most wicked of actions will almost always believe they are justified, on some level, for their deeds.

Your antagonist needs to have a motivation every bit as strong and compelling as your protagonist.

Ask yourself:

What’s your antagonist’s backstory?

What’s the Ghost/wound in his past?

What is the Lie He Believes that’s driving him?

What good reason does he have to initially engage in the conflict with the protagonist?

What good reason does he have to continue to engage in the conflict with the protagonist?

Hatred, vengeance, lust, and any other number of dark emotions are good qualifiers for your antagonist. But, alone, they are not enough to motivate his story goals.

It’s not enough for your antagonist to hate your protagonist just because. Dig deeper than that. The deeper you go, the more rounded a character your antagonist will become—and the better your protagonist will also have to become in order to face this impressive bad guy you’ve constructed for him.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What humanizing reason are you using to motivate your bad guy? Tell me in the comments!

The post How to Properly Motivate Your Bad Guy appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 24, 2016

How to Find and Fill All Your Plot Holes (How to Outline for NaNoWriMo, Pt. 4)

What is the single most important job of an outline for NaNoWriMo—or any other book at any other time of the year? We might come up with lots of answers, but they all tend to boil down to just this one: avoiding plot holes.

What is the single most important job of an outline for NaNoWriMo—or any other book at any other time of the year? We might come up with lots of answers, but they all tend to boil down to just this one: avoiding plot holes.

I hate plot holes. They drive me bazooey.

There you are, cruising along in a lovely story, full of lovely people, doing all kinds of fascinating things—when, bam!, you hit a massive plot hole. The story bounces three feet off the road, hits asphalt with a vertebrae-crunching thud, and half your lovely people (and their luggage) tumble right out the back of the story.

What a mess.

Readers don’t much like plot holes either, but I think we writers have a special hatred for them, for the simple reason that we have to fix them. Unfortunately for us, filling plot holes is never quite as simple as strategically drizzling a little hot tar.

However, on the positive side, if you make the time to approach your plot holes in a purposeful and knowledgeable way during your outline, filling them in doesn’t have to be tedious. It can actually be one of the most enjoyable parts of the entire writing process.

Why Your Outline Is the Best Place to Deal With Plot Holes

The reason I became an outliner in the first place was because I kept running afoul of massive plot holes in my first drafts. Fixing them was a gargantuan task simply because it meant not only figuring out where the story had to go from there, but also returning to fix everything I’d written up to that point, in order to make it all fit.

Plot holes are almost always the result of the story that’s already behind you—not the story that’s still ahead of you.

This means dismantling and rebuilding everything you’ve already created up to that point. If you’re discovering these plot holes while in the midst of your first draft, you’re going to have to dismantle everything—plot, theme, character motivations, narrative, prose, and the Muse only knows what else. Ugh.

But if you’re using your outline to spot the plot holes before they even happen, the most you’re going to have to dismantle is your idea of the story up to that point. You don’t have to rewrite a thing. You just have to cross out a few lines, turn the story in its new direction, and keep on trucking.

It’s so easy. Nothing intimidating about it at all. More than that: it’s fun.

Too often, discovering plot holes in the drafting stage feels like an exercise in self-flagellation: You messed up. You made a mistake. You weren’t a good enough writer to see this plot hole a mile off. Now you have to get down on your hands and knees and pay reparation.

It’s not like that at all in the outline. In the outline, discovering plot holes is exciting: Oh, look at this, a blank spot in the story you haven’t explored yet. What might you find? What’s this—a fork in the road? Which should you take? Why not both? Let’s sniff down first one trail, see what we find, and if we don’t like it, skip on back and try the other trail.

If you make a wrong choice in the beginning, there’s no rewriting involved, and the amount of time “wasted” is likely to be measurable in minutes rather than days.

3 Questions to Ask to Find Your Plot Holes

As per the previous posts in this series, you should already have a good chunk of your outline—and thus your story—figured out by the time you’re ready to tackle your plot holes head on. You’ve unearthed the skeleton of your story’s premise, plot, conflict, and character motivations. You’ve then breathed life into that skeleton by filling it with the beating heart of theme and character arc.

In short, you know quite a bit about your story by now. In seeing what is there, you’re ready to begin identifying what isn’t—in short, your plot holes.

Ask yourself the following three questions to suss out all the blank and/or weak spots in your story.

1. What Don’t You Know About This Story?

Plot holes are nothing more or less than incomplete or incorrect causes and effects. Something happens within the plot that wasn’t set up properly or that defies logic. Inevitably, these result from blank spaces within the story—areas you didn’t fully explore in order to causally link one part of your story to another that follows.

The first thing to do in hunting down these plot holes is simply to look into the darkness. Ask yourself: What don’t I know? What are you taking for granted about your characters, their motivations, and the consequences of their choices?

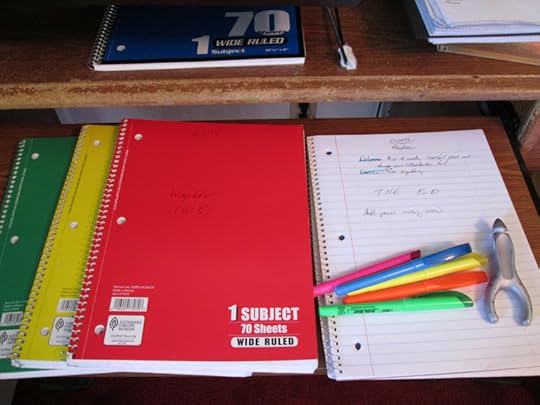

Sit down with your notebook and pen (if you’re outlining longhand, as I do) and consider what you don’t yet know about your story.

My outlining setup. Plot holes are afraid of bright colors, don’t you know?

Several specific areas to consider are:

Character Motivations

Consider all the important actions you know your characters will be taking within the story so far. Why are they doing these things? What are the story-specific causes that are creating these effects? The vast majority of plot holes arise from faulty character motivations: actions that have weak or nonexistent setup.

“Filler” Scenes

Take a look at the scenes you already know will be happening in your story. Usually, these are “big” setpiece scenes, perhaps even scenes you’ve been dreaming about since the very moment you came up with the story idea. But what happens in between these big scenes? What’s the filler that links them? Each scene must lead naturally into the next, which means there must be a causal chain to keep them from feeling like random episodes within the plot.

Character Relationships

What specific scenes and events are occurring to advance your characters’ relationships? This is especially important to consider with romantic relationships, but also just generally with any relationship that will evolve over the course of your story. If the characters start at Point A and end at Point B, they must experience obvious “marker scenes” along the way that create the progression in the relationship. Your feisty romantic couple can’t logically go from hating each other at the meet-cute to being true lovers at the end, unless you’ve filled in the blanks in between.

2. What Are the Specific Questions That Need to Find Answers?

The most valuable weapon in your outlining arsenal is the question mark. At every juncture in your brainstorming process, ask yourself questions. Lots and lots of questions. Here’s a quote from my book Outlining Your Novel:

The most valuable weapon in your outlining arsenal is the question mark. At every juncture in your brainstorming process, ask yourself questions. Lots and lots of questions. Here’s a quote from my book Outlining Your Novel:

When you get stuck—and you will get stuck—remember to ask yourself questions. Instead of stating the problem—“the princess is trapped in the high tower”—phrase it as a question—“how can I get the princess out of the high tower?” It’s amazing how much creativity can be unleashed with a question mark. For a squiggly line with a dot at the end, it wields untold power. Periods put a full stop on inspiration. They indicate whatever idea the preceding sentence holds is complete unto itself and doesn’t require further exploration. A question mark, on the other hand, is a swinging door, urging us to step forward and peek through the opening. What’s in there? How can we find it? How can we use it?

The General Sketches section of the outline is all about asking questions, finding their answers, then looking again to discover what new questions have arisen. When you run out of questions (which will continue through the next couple of outlining steps, which we’ll be discussing in future posts), that’s when you know you’ve finished your outline.

The more explicit your questions, the more explicit and helpful your answers can be. These questions will arise out of your discovery of the “blank spaces” in the previous section. They will be specific to your particular story and its needs.

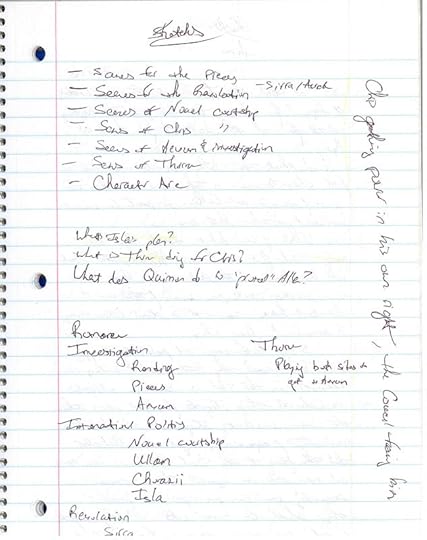

As an example, here are several specific questions I came up with during this section of my outline for my portal fantasy sequel work-in-progress Dreambreaker:

What plan is Isla (a minor antagonist) concocting?

What is Thorne (a potentially shady sidekick) doing for Chris (the protagonist)?

What does Quinnon (a bodyguard) do to “protect” Allara (the co-protagonist) that gets them both in trouble?

How does Chris gain enough power to threaten the Council?

How is [Spoiler] playing both sides?

If I left any one of these questions unanswered, I would end up with tremendous plot holes. Every single event in the story will affect every single event to follow, which means if I leave them blank in my own mind early on, I will likely end up failing to properly set them up subsequently.

3. What Are the Subplots?

I’m often asked: “How can I outline subplots?” Ultimately, you outline subplots just as you do any other aspect of the story: by being aware of them. This filling-in-the-blanks segment of your outlining process is the perfect place to dig up those important subplots and look at them in the full light of day.

Start by writing yourself a list of all the various story aspects you have yet to explore in any depth. Particularly, you might want to consider the following:

Minor characters’ goals.

Protagonist’s relationships with minor characters.

Minor characters relationships with each other.

Once again, the list you come up with will be very specific to your story. This is what mine looked like:

One of the best places to look for plot holes is in your subplots.

Romance

Chris and Allara

Allara and political courtship

Chris’s Investigation of the Rending

Geographical consequences of “Rending” of worlds

Clues and search for the “Pieces”

Clues and discovery of main antagonists

International politics

Rivale

Koraud

Cherazii

Laeler Council

Civil Revolution

Sirra

Thorne

Depending on the scope of your story and its stakes, your list may not be this long (or it may be longer!). You may also choose to eliminate or minimize some of the subplots in order to streamline your main plot. But in creating a list of all your options, you can figure out which are crucial and what further discoveries you need to make sure they fit into your story with believable cause and effect.

The Easy Patch-and-Fill Method for Stopping Plot Holes Before They Start

Now that you’ve identified all these potential plot holes—all these questions—now what?

Now is where the fun begins. You get to start brainstorming answers, throwing ideas at the wall, and seeing what sticks. Ask lots of what if? questions.

What if the hero had an evil twin? What if the heroine adopted her sister’s baby? What if the bad guy insinuated himself into the hero’s inner circle? What if, what if, what if? The possibilities are gloriously endless.

When you’ve come up with an idea you like, stop and highlight it in your chosen color (blue is mine). When you find that in answering one question, you’ve raised a new question (or three), highlight them in a different color (green, for me). This way, you can return to your notes, save the “Keeper” ones and create a new list of Questions, using your green highlights.

I use blue highlights to indicate “Keeper” ideas and green highlights to indicate new Questions that have arisen.

This is, bar none, my favorite part of the outline. It’s like watching the sun rise over the horizon. What was once a vague and murky landscape suddenly becomes a clearly defined vista. All the pieces start materializing. The story is there. You’re not even so much writing it as watching it complete itself. It’s magic!

And the best part is that, when you’re done, you will have a rock-solid story, tested and re-tested by logical questions to make sure you can safely drive your first draft straight on through with hardly a bump.

Stay Tuned: Next week, we’re going to talk about how to outline your characters’ backstory to create amazing subtext for your plot.

Previously in This Series:

Should You Outline Your Novel?

Start Your Outline With These 4 Questions

3 Steps to Find the Heart of Your Story

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What do you find most frustrating about plot holes in your story? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/how-to-find-and-fill-plot-holes-when-outlining-for-nanowrimo.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Find and Fill All Your Plot Holes (How to Outline for NaNoWriMo, Pt. 4) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 21, 2016

New Writing Journal Review: The WriteMind Planner

Is there anything sweeter than a new writing journal? How about a writing journal optimized to help novelists organize and refine their story notes?

Is there anything sweeter than a new writing journal? How about a writing journal optimized to help novelists organize and refine their story notes?

I was excited to get the opportunity to review author and designer Perry Elisabeth‘s latest project: the Write Mind Planner.

Like any self-respecting writer, just that first glimpse of customizable covers, organizable pages and sections, and a host of removable “modules” had my mouth watering. (Honestly, the hardest part was deciding what I wanted.)

It was one of those love-at-first-sight things, and I’ve only fallen in love with it more as I’ve used it.

My New Favorite Writing Journal: The WriteMind Planner

My writing process is roughly divided into two categories: the outline, which I write by hand in a notebook; and the first draft, which I write on the computer.

I used to write the first draft in Microsoft Word until über-writing software Scrivener came along and forever changed my life with its insane organizational features. It’s only drawback? It, of course, offers no similar organizational compatibility with my outlining notebook.

Then Perry’s Write MindPlanner entered my life.

The best way I can describe it is to say it is “Scrivener in a notebook.”

I’ve always felt the folks at Scrivener must have looked into my head, figured out how my writing process works, and then created a program just for my needs. Now, I’m beginning to wonder if my brain is an open book, because that is exactly what Perry has done in creating a writing journal that is perfect for my outlining process.

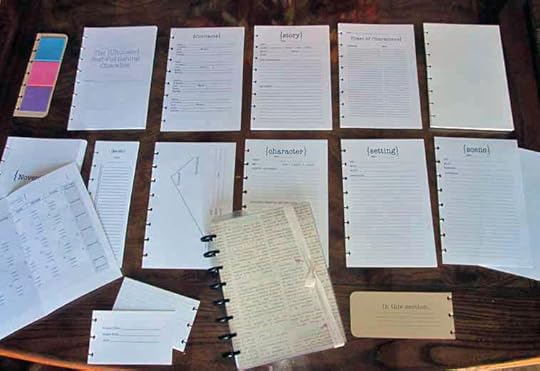

Look at all the goodies! The WriteMind Planner comes with every imaginable tool you could want for outlining, writing, or notekeeping.

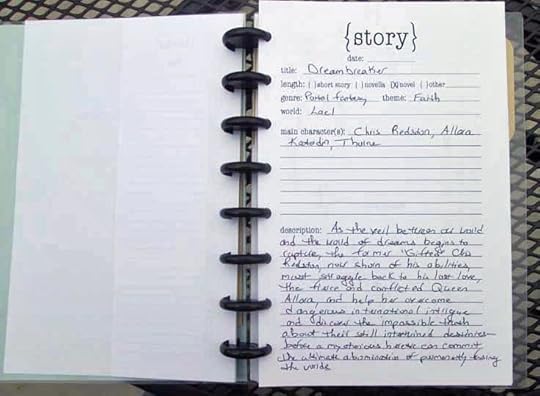

Because I’m currently in the process of outlining my portal fantasy sequel Dreambreaker, I was able to dive right in and start using my WriteMind Planner right away.

This writing journal is property of moi.

The Story Idea page lets me start with my title, logline, and other early story ideas.

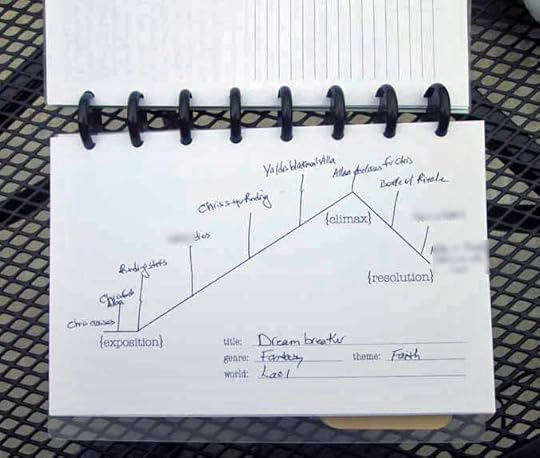

Handy chart for mapping the overall structural arc of the story.

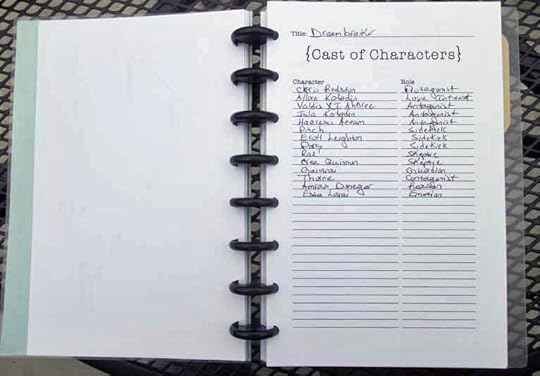

Space for extensive list of characters. I started with just the characters who will fill “archetypal” roles.

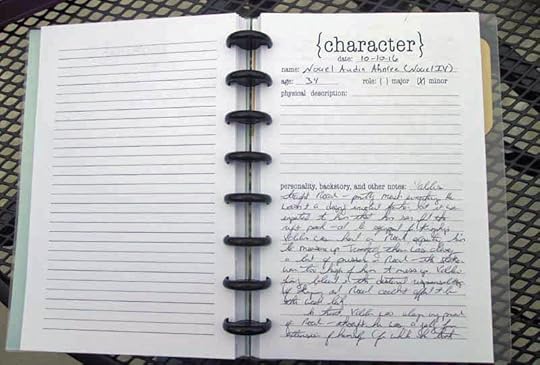

I love that there are pages in the writing journal to distinguish which part of my outline I’m working on: character sketches right now.

I can add as many lined pages as necessary for each section of my outline.

And there’s so much more than just this: setting and scene pages, places for sketch pages, scene index cards, and sticky notes.

So my review? Love it, love it, love it. If you’re a note-taker, outliner, and a lover of writing journals, the WriteMind Planner is the most complete and useful writing journal I’ve ever found. I will enjoy using it to beautify and organize my outlines for many years to come. Thank you, Perry!

About the Write Mind Planner

Offering the flexibility of a three-ring binder, but the stylish and compact look of spiral binding, this disc-bound planner will save your sanity! Simply peel pages away from the discs, move them wherever they’re needed in the planner, and press them back in. Organize ideas for use at a later date, track word-count goals, keep tabs on your works in progress, and more!

What Is Included in the Basic Planner?

8 black binding discs for ultimate flexibility: Add, remove, and move modules and individual pages with ease.

An artistic, cheerful cover page protected by transparent poly covers for durability. (Not reversible.)

“Please Return To” page for when you accidentally leave your planner at the library or coffee shop. When you’ve added your name and number (or email address) to this page, any good Samaritan will be able to make arrangements to return your planner!

30 To-Do list slips: slim pages with plenty of lines and checkboxes.

30 Idea Worksheets for all those ideas that pop into your head and need to be jotted down for later. Options include: Story Idea Sheets, Scene Idea Sheets, Character Idea Sheets, and Setting Idea Sheets.

Wordcount Tracking Calendars: Each month folds out so you have plenty of room to fill in your goals and daily word count. Track your weekly and monthly progress easily. Includes remaining months of 2016 plus all of 2017.

The Ultimate Self-Publishing Checklist: to help you take your work-in-progress from draft to publication and beyond without forgetting any steps!

Contacts section: so you’ll never lose the contact info for your editor, cover designer, beta readers, reviewers, etc.

50 sheets of lined paper: for note-taking, additional planning space, etc. Remember, because of the disc binding, you can move it to any section of the planner you’d like!

5 Tabs: your choice of decorative tabs to match your cover, or solid-colored tabs with fill-in-the-blank “In This Section” areas (select option from dropdown).

Additional modules sold separately. Inquire about custom modules by contacting the site.

Win Your Own WriteMind Planner!

Want a chance to win your own customized WriteMind Planner from Perry Elizabeth Designs?

One winner will receive a basic WriteMind Planner (extra add-on modules not included). (Open only to U.S. entrants.)

Log your entry in the RaffleCopter widget below.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What is your favorite writing journal? Tell me in the comments!

The post New Writing Journal Review: The WriteMind Planner appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 19, 2016

3 Ways Writers Can Instantly Spot Telling

Show, don’t tell is a broad concept, which is why one rule doesn’t cover it all. It’s subjective, and each telling instance found in your writing must be evaluated in context.

Does this sentence sound like telling? Is this scene explaining too much? But if you look at only the text, you risk missing “told prose” in your writing, since a sentence that technically shows can feel told. It’s important to examine the different levels of telling so you know what to look for.

Here are three.

1. Telling at the Sentence Level

You’ll find most telling at the sentence level. Most of these types of tells can be caught by searching for common red flag words, such as because, since, or when.

Keep in mind “tell” is subjective. A sentence can tell and still read and work fine. It’s up to you to decide if the sentence would be stronger with or without the telling. Such tells include:

Telling That Explains

These explain the reasons why characters feel or act as they do. They also sneak in when you fear the text isn’t clear enough and you have to explain information so readers “get it.”

Telling That Summarizes

These tells take a shortcut by summarizing instead of dramatizing. They often read as though someone is watching the scene unfold from the sidelines, giving a general overview of the action. They might even sound like a summary you’d find in an outline instead of a novel.

Telling That Conveys Information

Many tells exist only to convey information the characters would never think (or have reason) to share, such as world-building details or character backstories. They often sound too self-aware, or read as if the author was jumping into the story with a mini-lecture.

2. Telling at the Paragraph Level

If the told prose is explaining or summarizing a situation, the telling can affect an entire paragraph or even a page. You’ll find these tells most often when you pull away from the point-of-view character and start describing what’s going on from afar. These told sections can read like a summary of the scene in your outline. It might even read as if you planned to do more, but never got around to it.

Info-Dump Telling

An info dump often drops in the reasons why something is important in the overall world or setting of the story. Infodumps focus almost exclusively on information relating to the world. This is information readers “need” to understand the story.

Backstory Telling

These tells explain the history of a character, place, or item and why it’s important. Frequently, they’re more extensive than an info dump, sometimes using flashbacks and long internal monologues to reveal the often unnecessary history. Backstory tells focus exclusively on the histories of the characters, explaining why characters are the way they are.

3. Telling at the Scene Level

Telling doesn’t stop with summarized paragraphs. It’s possible to tell an entire scene. These are some of the sneakier types of tells, because writers rarely think to look for told prose at this level. This is a scene that contains important information, but in which you don’t show the scene unfolding.

The most common scene-level tell are flashbacks. They use an entire scene to dump history or explain backstory, since showing the scene might actually stop the story. Flashbacks are particularly tricky because they’re often shown, but they’re still telling readers information.

What’s annoying about these tells is that technically, they’re not traditional tells. They just read as though the author is summarizing or explaining events in the novel while nothing is happening on the page. Readers get bored, skim through them, and complain nothing happened in the novel. Since these scenes look like solid, functioning scenes, authors are left scratching their heads and wondering what’s wrong and why no one wants the book.

What Are You Trying to Tell Your Readers?

No matter where you find your told prose, before you revise it, take a step back and consider: What are you trying to tell your readers? Once you pinpoint what’s important and what needs to be conveyed, you’ll be better able to choose how to show that information. Look for ways to:

Suggest motives through what a character does, says, or thinks.

Show world-building rules through how those rules and details affect the character’s actions.

Show character backstory by choosing details and actions that had an influence on someone who lived through that history.

Show, don’t tell is a troublesome beast, but it’s a tool like any other. If you think about how you want to use it and what you’re trying to say, you’ll have a much better sense of how to convey that information to your readers.

Win a 10-Page Critique From Janice Hardy

Check out my new book, Understanding Show, Don’t Tell (And Really Getting it), and learn what show, don’t tell means, how to spot told prose in your writing, and why common advice on how to fix it doesn’t always work.

Check out my new book, Understanding Show, Don’t Tell (And Really Getting it), and learn what show, don’t tell means, how to spot told prose in your writing, and why common advice on how to fix it doesn’t always work.

Three Books. Three Months. Three Chances to Win.

To celebrate the release of my newest writing books, I’m going on a three-month blog tour—and each month, one lucky winner will receive a 10-page critique from me.

It’s easy to enter. Simply visit leave a comment and enter the drawing via Rafflecopter. At the end of each month, I’ll randomly choose a winner.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Have you every struggled with show, don’t tell? Tell me in the comments!

The post 3 Ways Writers Can Instantly Spot Telling appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 17, 2016

3 Steps to Find the Heart of Your Story (How to Outline for NaNoWriMo, Pt. 3)

Most of the time when you start figuring out how to outline a story, you know one of two things about that story. Either you know the skeleton of your story (its premise or plot), or you know the heart of your story. But it’s not enough to have just one. You gotta have both.

Most of the time when you start figuring out how to outline a story, you know one of two things about that story. Either you know the skeleton of your story (its premise or plot), or you know the heart of your story. But it’s not enough to have just one. You gotta have both.

On its surface, it certainly seems as if story is plot—the mechanics of characters doing things in pursuit of their goals. But as important and fun as all that stuff is, it’s just window dressing. To find the story you’re really telling—the story that’s really worth telling—you must look deeper.

You must find the beating, pulsing heart of your story. Otherwise, no matter how flash your plot may be, what you’re really creating is nothing more than a robot. It may move around prettily, but look into its eyes and you’ll know it’s empty inside—soulless, lifeless, heartless.

Today, we’re going to fix that.

How to Find the Heart of Your Story in Your Outline

So here you are, halfway through October, still figuring out how to outline for NaNoWriMo (or any other month of the year). You’ve already figured out the bones of your story—the answers to the four basic questions that power your plot (which we discussed in last week’s post).

But something’s missing. You have some cool ideas. But they just don’t seem like they’ve come alive for you yet.

Or maybe you were able to hear your story’s beating heart right from the beginning, but now its rhythm seems a little fainter, lost amid all the external plot stuff you dreamed up in the beginning of your outline.

Either way, now that you have a body for your story’s heart to live in, you’re ready to find that heart, refine it, and use it to make sure you create a plot with power and meaning.

What Is the Heart of Your Story?

Boiled down to its lowest common denominator, the heart of your story is its theme. This is what your story is about on a deeper, spiritual level. It is what your story is truly about, the black-and-white, archetypal, primal search for meaning and truth in the human life.

This is what every story—even the most careless—is about on some level. And the best stories are always those that tackle their themes head on and harmonize them with hard-hitting and pertinent plots that externalize their moral premises.

Can You Outline Theme?

I’m glad you asked. Because the answer is: Oh boy yeah.

In fact, theme is one of the single most important story elements you can address in the outline. An early understanding of your story’s thematic questions will provide you the foundation you need to make all the varied story decisions that follow.

Without this foundation, you won’t be able to pull the disparate elements of your story—plot, character, and theme—together into a seamless whole with a cohesive focus.

This is why the thematic questions are always my very next stop in my outline after figuring out the basics of the plot. Before I go one step further with my characters’ external adventure, I must first understand their internal journeys. Only then, can I move forward in crafting an external plot that catalyzes the inner journey and (even cooler!) provides an external metaphor for the very heart of the story.

A General Sketches Reminder: Keep It Creative

Outlining is very much about a melding of the minds: your “circular”/subconscious/”right-brain” creativity and your linear/conscious/”left-brain” logic. You’ll be bouncing back and forth between “loose” creativity and “tight” logic throughout the outlining process.

But it’s worth repeating that the General Sketches section of the outline (which I talk about in my books Outlining Your Novel and the Outlining Your Novel Workbook) is where you want to keep your brain at its loosest. You don’t want to impose too much linearity on the process just yet. You’re still just throwing paints at the wall to see which colors stick.

But it’s worth repeating that the General Sketches section of the outline (which I talk about in my books Outlining Your Novel and the Outlining Your Novel Workbook) is where you want to keep your brain at its loosest. You don’t want to impose too much linearity on the process just yet. You’re still just throwing paints at the wall to see which colors stick.

I write my General Sketches longhand in a notebook. I keep it very stream of conscious, more like a conversation with myself than anything. I’m asking questions, following the answers to their logical conclusions, discarding what doesn’t work, and answering whatever new questions then arise.

You’ll need to find your own rhythm, but as an example, here’s a characteristic excerpt from my outline for my portal fantasy sequel work-in-progress Dreambreaker:

I like the idea that Chris thinks everything is in place for him now—there’s a little Pride and Complacency at work—and he has to relearn his lesson.

Chris is more peace than Allara is. But he also starts out with a simple worldview. The worlds got knocked into focus for him after the last Book, and now they’re opened back up, it seems like God’s will, like God is rewarding his sacrifice. It all makes sense—until it doesn’t.

At that point, wouldn’t he be in despair? He did this once—gave everything, down to his very life. Now what?

I write my outlines longhand in a notebook (with an ergonomic pen).

3 Questions to Help You Find the Heart of Your Story

Get out your notebook or other outlining tool of choice and start by asking yourself the following questions on paper. Explore all the obvious answers until you find the ones that fit, that feel right, and that make sense within your vision for the plot. Find those answers, and you will find the heart of your story.

1. Plot: What Is Your Story’s External Conflict?

It’s true, we’re here today trying to find the heart of your story. But to do that, you must first remember all of fiction is a balancing act. The process of outlining a story is a continual bob and weave of sewing in first one story element and then another. We’re going to discuss this is much more depth in a future installment in this series. For now, suffice it that to find the heart of your story, you must actually begin with the skeleton.

You should already have identified your story’s basic plot, via last week’s 4 outlining questions. Now, it’s time to stop and take a long hard look at the plot you uncovered. What is it really about? What is the story under its skeleton?

Consider the following points:

What is your protagonist trying to achieve?

Why is he trying to achieve it?

What is the antagonist trying to achieve?

Why is he trying to achieve it?

What are the stakes (personal and public) should the protagonist fail?

How will the protagonist have to change to be able to externally and physically defeat the antagonistic force and gain his goal?

Even though these are all plot questions, the answers will depend on your story’s theme. (And now you see the integral weave of plot, character, and theme.)

Featured in the Outlining Your Novel Workbook

Your plot provides the framework for the theme that will emerge. Indeed, the plot must provide the framework, or else the heart of your story will fail to be central to the external story.

2. Character: What Is Your Story’s Internal Conflict?

In laying the framework for your story’s external conflict, you have also laid the framework for its internal conflict.

Now available for pre-order!

Your protagonist’s internal conflict is the foundation for his character arc. (Which reminds me: you can now pre-order the Kindle version of my new writing how-to book Creating Character Arcs! Paperback and other digital versions will be coming in November.)

Character arc is the transition a character undergoes over the course of the story. This change—whether for good or bad—is the heart of your story. Why? Because in change there is always purpose, there is always reason. Without change to either the character or the world around him, the story remains static—and has no point.

In a Positive Change Arc, the character will transform into a better or more equipped person. He learns the necessary survival skills—on an inner level—that allow him to appropriately handle his external conflict.

In a Negative Change Arc, he will learn incorrect skills or beliefs, which will ultimately cripple him in his pursuit of both his outer goals and his inner wholeness.

In a Flat Arc, the character himself will not change much, but he will help others around him to evolve through their own Positive Change Arcs.

Find the heart of your story in your theme by first determining which of the three character arcs your protagonist following.

To determine which type of arc is best for your story, consider the external conflict.

Will your character achieve his end goal? Why or why not?

Will he end as a better or worse person?

How might he need to grow into a better person in order to gain his goal?

How might his personal desires and motives change over the course of the story?

Character arcs and their internal conflict are founded upon the fulcrum of two opposing goals within the character:

1. The Thing the Character Wants

Prompts the external plot goal.

Is a conscious desire on the part of the protagonist.

Is a wrongful desire (either because it is an inherently harmful or selfish end goal or because the character blindly believes it will fix his inner problems when it will not).

Is based on a Lie (see next section).

2. The Thing the Character Needs

Is an internal thematic need.

Is often an unconscious desire on the part of the protagonist.

Is a healthy desire (which will ultimately lead to health, fulfillment, and wholeness—but not necessarily external gratification).

Is based on a Truth (see next section).

The Thing the Character Wants will power the external plot. The Thing the Character Needs will power his internal evolution over the course of the story. In the first half of the story, the character will be controlled by his Want; in the second half, he will begin to evolve into a stronger understanding of his true Need—which will ultimately lead him to personal (if not always public) victory. (Or, conversely, if he rejects his Need and clings to his Want, he will ultimately suffer a tragic end in a Negative Change Arc.)

Your external plot will usually show you what type of arc your character will be following. But only by recognizing, claiming, and strengthening that arc, via these internal-conflict questions, can you then knead the internal plot back into the external in a cohesive and seamless way.

3. Theme: What Is Your Story’s Theme?

And that brings us to the theme. Some authors shy away from consciously claiming their themes, believing the theme will become too on the nose.

But here’s the truth: your theme doesn’t just arise somewhere late in the story. It’s there, right from the start, in the conflict between your character’s external and internal needs.

In order to fully understand the import and potential of your plot and character arc, you must also bring the third member of the story trifecta front and center.

What is your story’s theme?

If you’ve answered the questions in the previous two sections, then your theme is already right there in front of you. But let’s clear the fog a little more. Let’s boil down your character’s conflicting Want and Need into something more fundamental and primal: a universal thematic premise.

Stop thinking of theme as a nebulous transcendent concept. Instead, think of your theme as a road within a defined beginning and ending.

As you figure out how to find the heart of your story, what you’re ultimately looking for is the story-long journey of theme.

The Beginning of Theme: The Lie Your Character Believes

Both your story and your theme begin with a false premise: your character believes a Lie. This Lie is what fuels the Thing He Wants. The Lie is what leads him to believe that if he can only gain the Thing He Wants, his inner self will find wholeness and victory.

Basically, this Lie has your character convinced he can fix his broken heart if only he can find the magic golden Band-Aid to put on his elbow.

He’s deluded. And it’s killing him.

The End of Theme: The Truth Your Character Believes

That’s why your character must grow into an awareness of the fundamental illusion of his Lie—so he can instead embrace the empowering (if often difficult) Truth that will set him free.

The Truth is the Thing Your Character Needs. It may or may not preclude the Thing He Wants. It may or may not lead him to final victory in the external plot. But it will always lead him to internal, spiritual victory.

The Truth is your story’s thematic premise. The Truth is the heart of your story. The Truth is the inner story that is being proven by the metaphor of the outer story.

Once you know your story’s Truth, you will be able to start mapping a way to help your character either find it or reject it in your story’s end. It will influence every important plot decision you make from this point on.

***

Your thematic premise is going to exist at the heart of your story whether you recognize it early on in the outline or not. Why not claim it right away?

The heart of your story is arguably the single most exciting element you’ll uncover during your outline. Theme is the reason stories remain the most powerful communication medium in existence. Having the opportunity to pack all that firepower into your story’s outline is a thrilling, heady, and deeply personal experience. Enjoy!

Stay Tuned: Next week, we’re going to talk about how to spot and fill all your plot holes before they even happen.

Previously in This Series:

Should You Outline Your Novel?

Start Your Outline With These 4 Questions

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion: How will you find the heart of your story? What is your theme? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/nanowrimo-3-steps-to-find-the-heart-of-your-story.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 3 Steps to Find the Heart of Your Story (How to Outline for NaNoWriMo, Pt. 3) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 14, 2016

7 Things You Need to Know About Plotting and Editing

When starting a new novel, a writer needs to overcome several challenges. Planning your plot is definitely one of those. You must decide on the elements that will define your story and that will help you deliver it to your audience in the right way, by creating a clear structure that helps readers progress from one part of the story to the next. Just as importantly, you must understand which emotions your writing should communicate to support the direction of your plot and ensure your audience’s emotions follow those of the characters–especially during the Climax.

Then, once you’ve finished your first draft, it’s time for self-editing: a process proves stressful for many writers. This is why it’s essential to have a plan in place so that you don’t feel overwhelmed. Editing can happen in different layers; you don’t need to correct all aspects of your writing at the same time.

Last but not least, proofreading: Definitely not the most creative part of the process, but at the same time, it is something no writer can avoid. It’s the final polishing of your work and, once again, there are tips and steps to follow that have been proven to work for many authors and can substantially improve your final result.

In this article, I would like to share with you a collection of tips on plotting, self-editing, and proofreading–all of which come from our community of published authors, who offer guidance and support to aspiring novelists. I hope you’ll find them useful!

Planning Your Plot: 3 Things to Consider

1. Choosing Your Narrator’s Voice

This is not your voice, not the tone you live in. It is a voice written by you specifically to tell your story; it’s the tone you write in.

Think about your tone and approach.

Who is the person narrating the story?

What do they sound like?

What’s their accent?

Choosing the right voice is essential to how your story will be delivered, how it will make readers feel, how they will perceive it.

For example, imagine Lewis Carroll delivering Pride and Prejudice. Would it have been the same Pride and Prejudice as we know it today? Not really. It probably wouldn’t have become as successful either.

2. Show More Than You Tell: Let Your Characters Act, Speak, and Think

Your characters must feel like actual people. For this to happen, you must let them act, speak, and think for themselves.

Rather than constantly telling the reader what characters did, said, or felt, let them “watch” what the characters are experiencing it. For example:

The writer tells: Then Mary approached Tim and told him he was the most annoying person in the world.

The writer shows: Mary approached Tim. “You are the most annoying person in the world!”

Notice the difference? By using dialogue, you give your characters their own voices, rather than filtering them through the narrator.

There must be a balance between showing and telling. Finding the right balance is the key to great writing.

3. Emotion Determines the Direction of Your Plot

Emotion is perhaps the main contributing factor in delivering an effective plot. The emotion of your writing determines how effectively it is delivered, as well as the feelings your characters are experiencing.

How do you want your readers to feel at given points in your story?

For instance, it would be detrimental if at the Climax readers feel bored. This is the ultimate point where you want them to feel that they can’t stop reading, that they are now part of the story and experiencing what the characters are experiencing.

Choose words that can both communicate the right emotions and direct the story in the right way. If your story conveys the right emotions at the right times, your readers will internalize it better by remembering the different emotions they felt as it progressed: different emotions will be associated with different parts of the story.

Editing and Proofreading Your Work: 4 Things to Consider

1. Write First, Edit Later

Writing is hard enough; just the thought of having to edit as well can be overwhelming. Set the editing part on the side to begin with: get the words out there first and you can focus on the nitty-gritty aspects of your writing later.

2. Concentrate on One Layer of Editing at a Time

You may have the urge to edit everything at the same time: your structure, your plot, your characters, your syntax, and your vocabulary. This can be exhausting and can make you risk losing your train of thought altogether. Instead, work through the different layers of editing separately.

3. Seek Feedback From Someone Who Doesn’t Know You

Advice is invaluable and finding beta readers for your work can be extremely helpful. Because friends and family may try to avoid hurting your feelings, you probably won’t get objective and constructive feedback from them. Instead, find someone who doesn’t know you personally.

Inkitt, the first data-driven book publisher and an online community for readers and writers with over 700,000 members, is a great platform for emerging authors who want to share their work, find an audience, and get feedback even if it is still in progress. We also offer support by providing resources for writers and hosting AMAs and group discussions with published authors who are eager to share their experience and tips. And what is most important is that if readers really like your novel, you might get it published: Inkitt’s vision is to democratize publishing by putting the decision in readers’ hands. The Inkitt algorithm analyzes reading behaviors to understand which novels have a strong potential for success. The next one could be yours!

4. Print It Out and Edit It by Hand

Screens can be deceptive. On a printout, it is much easier to spot grammar mistakes and underline and highlight phrases. Plus, technology can let you down: we’ve all had our computers crashing or acting up, and this is when you appreciate the value of having printed out a few copies of your work.

Bonus: The Importance of Strict Deadlines

Last but not least, this is something many published and successful authors have shared: actually sitting down and writing toward a set goal is tremendously important and helpful.

To get started, set yourself a word limit: for example, Graham Greene wrote 500 words a day, whereas Jean Plaidy wrote 5,000 words before lunchtime. What works best for you?

Once you’ve set your goals, be disciplined: sit down at your writing spot and actually get it done, even if these 500 words are the worst you feel you’ve ever written. Don’t forget: it is easier to improve and polish something that’s already there compared to finding the courage to face a completely blank page.

I hope this mini-collection of writing tips, gleaned from published authors with years of experience, will be of help.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What are your best tips for plotting and editing your fiction? Tell me in the comments!

The post 7 Things You Need to Know About Plotting and Editing appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 10, 2016

Start Your Outline With These 4 Questions (How to Outline for NaNoWriMo, Pt. 2)

“Where do you start your outline?” is a question I often receive. Now, if the obvious answer “start at the beginning” were, in fact, the right answer, no one would be asking this. The reason writers ask this question is because, when properly approached, outlines are anything but linear—which can make the “beginning” rather hard to identify.

“Where do you start your outline?” is a question I often receive. Now, if the obvious answer “start at the beginning” were, in fact, the right answer, no one would be asking this. The reason writers ask this question is because, when properly approached, outlines are anything but linear—which can make the “beginning” rather hard to identify.

Whether you’re needing to figure out how to outline for NaNoWriMo next month (in which writers commit to writing 50,000 words in 30 days)—or whether you simply want to notch up your outlining skills to the next level—you’re in the right place.

Welcome to Part 2 of my series about the advanced techniques of how to outline your novel in a creative and nurturing way, which will help you write better stories and become a better writer in general.

How to Start Your Outline: Discover the Skeleton of Your Story

Back to our opening question: Where should you start your outline?

Honestly, the idea of starting at the linear beginning is downright impossible at this early stage in the process. Why? Because you don’t yet know what your story’s linear beginning will be.

It’s true you could sit down and arbitrarily create a beginning scene right off the bat: “Erick is taken prisoner by the terrorists.”

But how do you know that’s the right beginning for your story? How do you know this is the beginning that will best nurture your story’s theme? The beginning that will properly set up the main conflict? The beginning that will introduce your protagonist in the prime characteristic moment? The beginning that will tie into that perfect ending scene?

Short answer: you don’t know.

What I want you to do for the time being is just forget all about linearity. Forget all about the “beginning” scene.

Instead, you’re going to startyour outline by stepping back from the nitty-gritty micro-picture of the scene list. You’re going to start your outline by looking at your story’s big picture.

Your outline’s first job is to help you discover your story’s skeleton.

What is your story about?

Who are the characters?

What themes are inherent to this conflict?

Where will the story end?

What obstacles will arise between the protagonist and that end point?

Only once you know the answers to these big-picture questions can you start honing in on the more obvious “beginning” of the outline’s first scene (which we’re not even going to discuss until the very last installment in this series).

What You Should Already Know About Outlining

As I mentioned in last week’s post on the basic how and why of outlining, what I’m going to be sharing in this series is essentially the “advanced” skill set of outlining. I shared the basic steps I use to brainstorm and create outlines in Outlining Your Novel and the Outlining Your Novel Workbook. I’ll be touching on all of those steps in this series, but only to use them as a launch pad for more in-depth techniques and explorations.

As I mentioned in last week’s post on the basic how and why of outlining, what I’m going to be sharing in this series is essentially the “advanced” skill set of outlining. I shared the basic steps I use to brainstorm and create outlines in Outlining Your Novel and the Outlining Your Novel Workbook. I’ll be touching on all of those steps in this series, but only to use them as a launch pad for more in-depth techniques and explorations.

For those who haven’t yet read the book (or haven’t read it in a while), let’s do a quick refresher of the basics we’ll be building off today.

The first step in the outlining process is what I call “General Sketches.” This is the big-picture part of the outline, where you’re throwing all your ideas onto the page, seeing what sticks, and working your way through the plot holes and salient questions until you can see a whole story emerge.

Although you will undoubtedly be coming up with individual scene ideas, this section of the outline is not a scene outline. This is the figure-out-what-your-story-and-characters-are-about part of the outline. It’s very freewheeling, very stream-of-conscious—and, as a result, is one of the most exuberant parts of the entire process. The vast majority of this series will be dealing with questions you need to be asking yourself during the General Sketches segment of your outline.

Very quickly, here are the basic steps that make up the General Sketches:

1. Record What You Already Know About the Story

Whether you’ve only just come up with a new idea for your story or whether the story has been brewing in the back of your head for several years (as mine almost always do), you will always start out knowing something about the story. Some of these tidbits will be concrete ideas; others will be only vague and distant impressions.

Start your outline by writing down everything you already know about the story. Clear out your brain. Put it all on paper in a short list, so you can evaluate what you already have.

2. Identify the Existing Plot Holes and Questions

Now comes the fun part. In writing down what you know about your story, you’re also going to discover how much you don’t know.

The protagonists fall in love. Yay! But how do they fall in love? How do they get from Point A to Point B? The female protagonist has a horrific facial scar that makes her live like a hermit. Interesting. But why? How did she get it? And how will she overcome her shame and reenter the world?

These are all questions you may be prompted to ask. So start asking! And let your imagination run riot in coming up with delicious possibilities.

3. Ask the 3 Important “What” Questions

To help yourself think outside the box in finding the right answers for your story, you’re going to use the following three “what” questions to guide you in looking at things from a different angle.

1. What if…?

2. What is expected?

3. What is unexpected?

You will use these three techniques over and over throughout the entire process of the General Sketches, until you have satisfactorily filled in all your story’s blanks.

4 Discovery Questions to Help You Start Your Outline

As you explore the exciting terra incognita of your story’s General Sketches, you will also be asking yourself many “smaller,” more specific questions to help you narrow the focus of your story and find the perfect perspective and themes to bring it to life in a cohesive and powerful narrative.

Start by asking yourself these four questions in order to discover the big-picture “skeleton” of your story:

1. What General Conflict Does Your Premise Provide?

Once you understand enough about your story to write its premise sentence, take a step back and examine the ramifications of that premise. What main conflict is at the heart of this premise?

Remember, a premise sentence presents all the vital parts of your story in one solid punch of a sentence (or two). My premise sentence for my dieselpunk/historical novel Storming ran like this:

Remember, a premise sentence presents all the vital parts of your story in one solid punch of a sentence (or two). My premise sentence for my dieselpunk/historical novel Storming ran like this:

After an eccentric woman falls out of the sky onto his biplane (situation), an irresponsible barnstormer (protagonist) must help her (objective) prevent a pirate dirigible with a weather machine (opponent) from wreaking havoc (conflict) on the Nebraska hometown he fled nine years ago.

Even when this was all I knew about the story, I knew what the general shape of the main conflict would be: a biplane pilot taking on sky pirates. That was the conflict the story had to convey—and thus the conflict I needed to create in the outline.

Understanding your story’s inherent conflict is the first kernel of information you need to start digging your way into the heart of that story. You must find the primary conflict before you can answer any other important questions about your story.

Featured in the Outlining Your Novel Workbook.

2. Who or What Is Your Story’s Antagonistic Force?

Once you’ve discovered your story’s main conflict, your next step is a surprisingly non-intuitive one: find your antagonist.

As I wrote in a recent post on this subject, this question and its early placement in the outlining process was a groundbreaking change in my approach to storytelling. Like most authors, I’ve started every single outline I’ve ever written (up until the one I’m currently writing for my portal fantasy sequel Dreambreaker) with the protagonist.

Why not, right? Your protagonist is a completely obvious entry point to your story.

But as I realized just this year, when you start with your protagonist and his goals, the antagonistic force too often becomes an afterthought. As a result, the conflict between the protagonist and antagonist becomes fragmented and does not drive the plot in a cohesive, integral way.

With this latest outline, I started by exploring the antagonistic forces in my story. What did they want? Once I knew that, I could see more clearly how, where, and why my protagonist would run afoul of them.

Specifically, I considered five different levels of antagonistic forces (not all of which need to appear in every story) and the various levels of stakes they might create:

1. Global Stakes.

2. International Stakes.

3. National Stakes.

4. Public Stakes.

5. Personal Stakes.

I identified/created unique antagonists for each category, then took a closer look at each of them. Specifically, you want to ask yourself:

1. What does each of your antagonists want (goal)?

2. Why does your antagonist want this (motive)?

3. How will he go about obtaining his goal (plan)?

Take your time exploring your antagonists. You may be eager to get to the good stuff (aka your protagonist) right away. But your antagonists will provide the foundation for your entire story. The stronger your understanding of the antagonistic forces that oppose your protagonist, the more adeptly you will be able to craft a conflict that creates the most meaningful, realistic, and symbolically rich journey for your protagonist.

3. What Are Your Protagonist’s Goals and Motivations?

Once you’ve completed your discovery of your antagonistic force(s), you’re now ready to devote your attention to the character(s) you really care about: your protagonist.

Because you started this part of the outline with your premise sentence and because you now understand what your antagonists are all about, independent of their impending relationship to your protagonist, you will already have at least a sense of who your protagonist is and what he wants.