K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 56

August 29, 2016

6 Reasons You Need to Make Way More Writing Mistakes

Writing mistakes are frustrating—especially when that mistake is novel-sized and cost you months of work before you realized it was, indeed, a mistake. Because frustration is a negative emotion, we usually do everything in our power to, first, avoid making writing mistakes and, then, when we inevitably do make them, distance ourselves from them as quickly as possible. But maybe that’s a mistake in itself.

Recently, I read a study suggesting that the messier someone’s desk, the more creative they are likely to be (which presents a problem for me). Some might suggest the messy desk, in itself, is actually a mistake. But perhaps in our pursuit of perfection, we are robbing ourselves of opportunities for even greater growth.

Writers put tremendous pressure upon themselves to be perfect. Search “writing perfectionism” and you’ll get page after page of helpful tips. It’s a popular topic because almost all writers suffer the fear, shame, and crippling rigidity of perfectionism at some point or another.

Which is ridiculous, since no writer nowhere at no point in time has, or ever will, write the perfect book. In short, all this self-flagellation is not only pointless, it’s even counter-productive.

Every Novel I’ve Written Was a Mistake

Granted, some of my novels have been bigger mistakes than others. But even the ones that garner great reviews and win awards are full of things I could have done better.

Sometimes I beat myself up over that. Sometimes I even cringe when I hear a reader say, “I’m so excited! I’m going to read one of your novels!” I have to resist the urge to make excuses for everything my 20/20 hindsight tells me is wrong with all my beautiful babies.

And that’s the good books!

We won’t even talk about the four novels I wrote before being published. We won’t talk about the three failed interim books that stumbled out of the gates, crippled as much by what I thought I knew about storytelling as what I didn’t.

But I am so thankful for all of those books, warts and all. If they were perfect—or, worse, if I somehow misguidedly believed they were perfect—I would miss out on so many amazing opportunities to improve my writing and to make better mistakes in my future books.

It’s time to stop beating yourself up for making writing mistakes. Scratch that. It’s time to stop hoping you won’t make writing mistakes. Instead, it’s time to embrace those mistakes as one of the most rewarding and advantageous parts of the entire writing process.

6 Ways to Make the Most of Your Writing Mistakes

Here are six positive mindsets to consciously pursue in making the most of your writing mistakes.

1. Realize Nothing Is Ever Wasted

This is one of my favorite sayings. Everything that happens in life, even the stuff we wouldn’t choose for ourselves, even the downright awful stuff, is a cause that creates an effect. Many of the most valuable lessons, in life as in writing, are those mined from the discomfort of mistakes.

When you put the time, effort, and thought into writing a story, that investment will always bear fruit—even if that fruit isn’t a spectacular story. The experience itself was worthwhile, and the lessons you’ll carry away from it will provide you with tools to move forward in proactive ways.

Takeaway:

When you complete a story and it’s, well, stinky, don’t count it as a waste of time or effort. Tap into gratitude for the experience and trust it will lead you into another worthwhile experience—and perhaps a better story down the road.

2. Don’t Beat Yourself Up for Writing Mistakes

No one will ever be harder on you than you are on yourself. Once you realize that, it’s surprising how easy it is to step out from under the cloud of blame and accept your mistakes as a natural and needed progression.

Please tell me what possible benefit could come of beating yourself up for your writing mistakes? So you didn’t write a perfect story. So what? Does telling yourself you’re a terrible writer, that you’ll never measure up, that you just wasted your life on this story—does any of that help you write a better story? Does it help you be a better person?

Absolutely not. So just stop. Think of your writer self as an eager, creative child. When that child doesn’t succeed, are you going to hold him in your arms—or spank him?

Takeaway:

Forgive yourself for your writing mistakes. Truly, they only matter to you. You’re not letting anyone else down, and when you think about it, you’re not letting yourself down either. Rejoice in the experience and move on.

3. Purposefully Give Yourself Space to Mess Up

Let’s hark back to this whole myth of perfectionism once more. It’s the bar all writers are aiming at: the perfect story. But it’s a myth, people! We’re trashing our self-esteem for nothing. Think of it this way: what’s the perfect time for a competitor in a race?

Zero seconds. That’s perfection.

It’s also impossible, and you don’t see Michael Phelps throwing a fit in the pool every time he fails to get there.

It’s time for writers to embrace the beauty of writing mistakes. You will never write a book that is perfect in your own eyes. And even if you did, it still wouldn’t be perfect in the eyes of others. And that’s okay. That’s awesome. That’s exciting!

We have a tendency to create standards for ourselves that are far too high. Writing your first book? Trust me, it’s not going to outsell Stephen King and become an instant classic. So don’t even go there. Determine realistic goals (and realize it’s okay if it takes you longer than you wanted to get there).

Takeaway:

Instead of striving for the impossible, consciously give yourself permission to mess up. When you do, the floodgates of creativity burst open in your mind. You may not even realize how much you’re holding yourself back by studiously attempting to avoid writing mistakes. When you throw your own false expectations out the window, you open yourself and your writing up to all kinds of previously unforeseen possibilities.

4. Accept Writing Mistakes as the Opportunity to Experiment

This is where writing mistakes get fun. As that unmitigated failure known as Albert Einstein once said:

Anyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new.

If you cling your to fear of mistakes, it will, without question, prevent you from reaching your full potential. That’s the irony of perfectionism: it doesn’t create perfection; it cripples it.

What would happen if, instead of trying avoid writing mistakes, you started trying to make them?

]Just think about that for a minute.

True, your logical brain is going to guide you away from most of the full-on foolhardy mistakes (like, say, purposeful spelling and grammar gaffes). But doesn’t the idea of making mistakes on purpose perk up your creative brain a little bit? Doesn’t it inspire a little swirl of color and excitement back there? What if you could write anything without worrying about the “rules”? What would happen? What would you write? Would it be better or worse than otherwise? Who knows? That’s the point.

Takeaway:

Stop thinking about mistakes as mistakes. Think of them, instead, as opportunities. They are opportunities to consider old problems in new ways, to come up with fascinating workarounds you would never have discovered otherwise, and to learn and grow into a better mastery of your craft.

5. Examine Your Writing Mistakes for Lessons to Move Forward

On the rare occasions when my writing has just worked, when a story has flown onto the page fully formed and nearly flawless, I rarely know why it worked. There was some magic ingredient at play, and darned if I can find it half the time, much less bottle it for future use.

Ah, but the mistakes. The moment I know enough to identify a mistake is the moment I have just made an inimitable new discovery about my craft and, usually, myself.

Perfection is impossible to analyze. It just… is. Sometimes it’s tougher to examine and break down a good story to figure out how it works than it is to take apart a less-than-good story and identify exactly why it didn’t work. Writing mistakes provide you with the opportunity to look through the cracks and explore the mechanics of storytelling. In her May/June 2016 Writer’s Digest article “Secrets to Success With Both Approaches,” Paula Manier observed:

Every mistake is just you “figuring out how to do it.”

Whenever you discover how to do something wrong, you’re one step closer to doing it right the next time. You’ll never make the discovery if you don’t first make the mistake.

Takeaway:

Don’t shy away from your writing mistakes. Examine everything you write for its weak points. Why didn’t this work? You might not have known the answer to that when you wrote the story, but the very fact that you know something is wrong means you will find the answer if you keep at it. Do this with other people’s stories as well. I am constantly breaking down books and movies, identifying what doesn’t work, so I can figure out how to do it right in my own writing.

6. Realize Sometimes the Only Path to Finding the Right Way Is to Explore the Wrong Ways First

Stories are not straightforward. Even if you were to follow every single writing rule to the letter, this does not mean you will get a story right the first time out of the gates. Every story is unique and requires a unique understanding from the writer.

This being so, sometimes the only path to finding the best way to right your story is to first be willing to explore all the wrong ways. In a May 2016 interview with The Writer, award-winning author Tea Obreht explained:

Even work you consider to be your worst is good for something. Every effort teaches you about your desires and tendencies, or guides you towards some new possibility, or shuts the door on an avenue you mistakenly thought was the right one. It’s a trial and error game, and every line you write—especially those that never make it to the printed page—has value.

Even as you try to streamline your writing process, don’t put too much pressure on yourself to “get it right” the first time. Sometimes the best parts of our stories are buried deep within ourselves. Sometimes we have to do a lot of digging to unearth their true beauty. Does all the time and effort of these false starts qualify as a mistake? Of course not. Rather, it’s a necessary, downright invaluable part of the process.

Takeaway:

Embrace your writing mistakes, both large and small. Give yourself permission to think outside the box, to wander off road, to follow your instincts. Sometimes those instincts will be wrong, but you will always learn something worthwhile. And the more you follow your instincts down the wrong roads, the more you hone them into an awareness of the right roads.

_

When your surrender your fear of mistakes, the tremendous surge of possibilities can be overwhelming. Take it slow at first, but give yourself permission to swim in the deep water where true creativity lives, unshackled by the limited idea that making a mistake is the worst thing you could possibly do. It’s not. It might even be the best thing.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is your knee-jerk reaction when you realize you’ve made writing mistakes? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/6-reasons-you-need-to-be-making-way-more-writing-mistakes.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 6 Reasons You Need to Make Way More Writing Mistakes appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 19, 2016

Vacation Notice: See You in a Few!

“What’s this?!” you say. “No new writing post? How dare you, madam! Do you fail to realize the insult and injury of this lapse? In short, you scullion! You rampallian! You fustilarian! I’ll tickle your catastrophe!”

To which I must reply: you’re totally right, but I beg of you to leave my catastrophe alone.

I promise I have a good excuse. Turns out: I’m on vacation! Whoo! Cruising Alaska’s Inside Passage as a matter of fact.

I promise there’ll be writing posts galore (including the continuation of the ongoing The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel series) when I get back Monday the 29th.

Until then, here are a few podcast appearances I’ve made lately:

Talking character arcs and Dreamlander‘s sequel on The Very Serious Writing Show

Talking outlining and structuring with Bleeding Ink

Talking self-publishing, marketing, characters, and Storming with Prose, Poetry, & Purpose

Some important writing posts you might have missed:

A Quick Guide to Beta Reader Etiquette

Get Rid of On-the-Nose Dialogue Once and For All

The Lazy Author’s Way to Identify and Overcome Writing Weaknesses

The 5 Secrets of Choosing the Right Setting for Your Story’s Climax

For Writers on the Verge of Writing Spectacularly Complex Characters

And some goodies from other people:

Stress & Burnout—How to Get Your Creative Mojo Back by Kristen Lamb

How to Successfully “Genre Hop” as an Author by Lindsay Buroker

Why Write? There Are Already Too Many Books In The World by Joanna Penn

The Problem with Female Protagonists by Jo Eberhardt

These Cats Share Why Writers Are Readers by Pamela Hodges

Three Ways Social Media Hurts Your Productivity by Rochelle Melander

See you soon and pray I don’t get seasick!

The post Vacation Notice: See You in a Few! appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 15, 2016

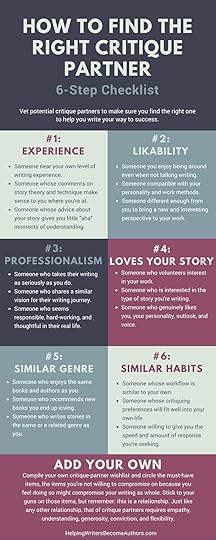

How to Find the Right Critique Partner: The 6-Step Checklist

Sometimes figuring out how to find the right critique partner feels about as daunting as finding the right marriage partner. First, you just have to find someone who’s interested, and then you somehow have to make sure this someone is the right someone. No pressure, right?

Sometimes figuring out how to find the right critique partner feels about as daunting as finding the right marriage partner. First, you just have to find someone who’s interested, and then you somehow have to make sure this someone is the right someone. No pressure, right?

There’s a lot on the line in choosing the right person to critique your writing. The whole goal is to find someone who can help you, someone who can objectively guide you to overcoming your weaknesses and deepening your strengths. When you hire a professional editor, you at least have the opportunity to read their credentials, check out their previous clients, and perhaps get a few glowing testimonials.

Because the dance of critique partnering is much more casual—fellow writer to fellow writer, with no money exchanged—the standards often feel lower. But the stakes aren’t. The difference between how to find the right critique partner and the wrong critique partner can affect your writing career, for better or worse, for years to come.

What can you do to raise your chances of finding the right critique partner—and avoiding the wrong one?

In my exclusive Wordplayers Facebook group (which you can qualify to join simply by reading one of my writing how-to books), Marya Miller raised this excellent question:

Today, let’s examine the checklist for vetting your potential critique partners to make sure you find the right one to help you write your way to success.

What Is a Critique Partner?

But first, let’s take care of a potential elephant in the room. I know some of you may be asking right now: What is a critique partner?

A critique partner is a fellow writer with whom you exchange critiques of your manuscripts. This, of course, means this person is indeed someone who critiques—not just your mom or your best friend who loves (or says she does) every word you’ve ever written. This is also, optimally, someone who understands how to balance criticism with encouragement, telling you what they like about your story as well as what needs to be improved.

For a guide to the do’s and don’ts of critique-partner etiquette, click here.

“Critique partner” and “beta reader” are often used interchangeably. However, there is a distinction: beta readers aren’t necessarily fellow writers and aren’t necessarily receiving a critique back from you in return.

Editors are also distinct from critique partners, in that they are usually professionals (either freelancers you hire yourself or someone hired by a publishing company to polish your book after you’re under contract).

6-Step Checklist: How to Find the Right Critique Partner

First, of course, you have to find a few potential critique partners. To do that, you must go where critique partners are to be found.

For a list of places to find critique partners and beta readers, click here.

Once you’ve got your hook in the water and the critique partners are nibbling, here are the six things to consider before deciding whether you should reel them in or throw them back. I’ve listed them in order, from most important to least.

1. What Is This Critique Partner’s Experience Level?

This is the single most important question to ask yourself. You are putting yourself at this person’s mercy. You are asking them to tell you what’s wrong and what’s right with your story. This means, of course, that it’d sure be nice if they ended up actually knowing what they’re talking about.

As vital as critique partners are to the writing experience, one of the common complaints about the system is that it can sometimes amount to the blind leading the blind. Inexperienced writers often don’t even realize how much they don’t know. They blithely repeat “rules” on POV, plot, and character development without yet truly understanding what they’re talking about.

It’s important to realize upfront that just because someone has an opinion about your writing doesn’t automatically mean that opinion is right. By extension, just because someone is willing to read and comment on your story doesn’t mean you’ll automatically get any value out of their participation.

What You Should Look For in a Critique Partner:

Someone who is at or (optimally) a little ahead of you in their level of writing experience.

Someone whose comments on story theory and technique make sense to you where you’re at.

Someone whose advice about your story gives you little “aha” moments of understanding.

How to Verify a Critique Partner’s Level of Experience:

Look at their blog, especially if they post about the writing process.

Read their books or stories, if they have any published or available.

Exchange a “trial” critique of no more than a chapter to see if their advice feels sound.

2. Do You Like This Critique Partner?

Once you know your potential critique partner is at a correlative level of experience and knowledge, the next step is to consider whether or not you will actually enjoy working with this person. Granted, sometimes it’s worth putting up with someone who drives you nuts if they’re providing enough value.

Ideally, however, you are going to be cultivating this relationship for the rest of your writing career (my very first critique partner Linda Yezak and I are going on ten years now). This person is someone you’re going to spend a lot of time with—either in person or digitally. You’re going to have their voice playing in your head over and over (especially when they have something negative to say). Wouldn’t it be nice if you could be friends? Even more important, it’s much easier to swallow critical advice from someone you love and who you know has your best interests in mind.

What You Should Look For in a Critique Partner:

Someone you’d enjoy being around even if you weren’t talking about writing.

Someone who seems compatible with your personality and work methods.

Someone who is different enough from you to bring a new and interesting perspective to your work.

How to Verify a Critique Partner’s Compatibility:

Spend some time with them, either in person or on social media.

Talk about writing and reading: your favorite authors, books, and movies.

Talk about non-writing subjects: your hobbies, families, even your political and religious views, if appropriate.

3. Will This Critique Partner Be Professional and Responsible?

The very nature of critique partnering is unprofessional. There’s no exchange of money. You’re just friends helping each other out. But you’re also professionals in your own right as writers, and you want a critique partner who brings that level of commitment and responsibility to the table.

Even if you’ve yet to be published, writing is serious business. The last thing you want to deal with is putting your time and effort in the hands of someone who isn’t going to pull through when it counts. Few things in writing are as frustrating as sending a manuscript to a critique partner, waiting patiently, and never hearing back.

Although it’s important to remember that critiquing a manuscript is a large time commitment that should never be taken for granted, you certainly don’t want to put yourself in the position of depending on someone who turns out to be undependable.

Just as you want a writer who roughly matches your level of experience, you also want someone who can rise to your level of professionalism—or (who knows?) maybe even challenge you to raise your standards.

What You Should Look For in a Critique Partner:

Someone who takes their writing as seriously as you do.

Someone who shares a similar vision for their writing journey.

Someone who seems responsible, hard-working, and thoughtful in their real life.

How to Verify a Critique Partner’s Professionalism:

Pay attention to whether or not they respond to emails and social media exchanges in a timely manner.

Check their social media statuses and blog posts for indications of their dedication to their writing (how much time do they spend writing?) and their frequency of project updates (is this a hobby or a profession?).

Explain your own expectations for a working relationship to double check they’re on the same page.

4. Does This Critique Partner Love Your Writing?

Now, I’ll preface this by saying that if your writing is currently stinky, then it’s not necessarily the worst sign in the world if a potential critique partner isn’t raving about it. But you want to find a person who is at least interested in what you’re writing. The more passionate they are about what you’re writing (and in return, the more passionate you are about their writing), the stronger and more useful your partnership will be.

Ideally, you want to find someone who bounces in their seat with excitement when they receive your latest manuscript—instead of groaning because now they have to make time to “fix” all your mistakes. Even though critique partnering is mutually beneficial, it is still a huge commitment of time and energy on both partners’ parts. Everything works so much better if each of you is actually enjoying reading the other person’s story.

What You Should Look For in a Critique Partner:

Someone who volunteers interest in your work (because they read a tweet about your premise or because they read an excerpted chapter on your blog).

Someone who is interested in the type of story you’re writing.

Someone who genuinely likes you, your personality, outlook, and voice.

How to Verify a Critique Partner’s Interest in Your Work:

Send them a sample chapter or two (and get one back from them in exchange).

Ask them to be honest, and gauge their response (are they on board with your vision for the story?).

If you’re comfortable doing so, chat about your plans for this story or future stories (are they engaged in the conversation, do they get where you’re wanting to go with this story?).

5. Does This Critique Partner Share Similar Genre Interests?

This one isn’t a hafta. In fact, there some nice benefits of getting viewpoints outside your own genre. But you’ll receive some of your most valuable advice from critique partners who have experience (as both readers and writers) within your chosen genre. Non-genre writers aren’t going to be able to spot where you’re going off the rails in the same way as will someone who understands the genre.

This also ties into the previous section—you want someone who understands and appreciates what you’re writing. If your critique partner hates fantasy, then he’s probably not going to be a ton of help in your quest to become the next Patrick Rothfuss.

What You Should Look For in a Critique Partner:

Someone who enjoys the same books and authors as you.

Someone who recommends new books you end up loving.

Someone who writes stories in the same or a related genre.

How to Verify a Critique Partner Has Similar Genre Interests:

Ask them which genres, books, and authors are their favorites.

Evaluate their story blurb to discover its similarity to your own focus.

Check out their Goodreads profile to discover how similar or disparate their reading experiences are from yours.

6. Does This Critique Partner Have Similar Work Habits to Yours?

The final thing to consider is how compatible your working style will be with your potential critique partner’s. Do they put out three books a year—while you only put out one book every three years? Do you write hulking 200,000 word epics—while they write 60,000 word novellas?

It’s totally possible to work around disparities such as these, but you should both enter the relationship with an idea of what you’re getting into. Ideally, you want to exchange a fair balance of work, so both of you are receiving as much as you’re giving.

Other considerations include your preferences for how you share your work. One of my critique partners often prefers to send me work chapter by chapter, while I prefer to send my entire finished manuscript all at once. Other critique partners prefer chapter by chapter updates of criticism, while still others prefer to wait until I’ve finished so I can provide a big-picture analysis.

All of these situations are negotiable, but it’s valuable to at least have some ground rules when starting out. If you understand each others’ preferences and expectations, you can make educated decisions about whether or not this critiquing partnership is going to be the most useful choice for either of you.

What You Should Look For in a Critique Partner:

Someone whose workflow is similar to your own.

Someone whose critiquing preferences will fit well into your own life.

Someone willing to give you the speed and amount of response you’re seeking.

How to Verify a Critique Partner Has Similar Work Habits:

Have an open discussion about your habits and expectations.

Ask them to clear the air about their preferences.

Agree upfront about patterns and deadlines for your critique exchanges.

Even with these guidelines in place, finding the right critique partner can still be largely a matter of trial and error. You may find exactly the right person immediately, or you may have to play the dating game for several years before finding exactly what you’re looking for.

It’s also important to realize no critique partner is perfect. With a few obvious exceptions, it’s often worthwhile to compromise on a few of the items on your checklist, rather than go without peer feedback altogether.

Compile your own critique-partner wishlist and circle the must-have items, the items you’re not willing to compromise on because you feel doing so might compromise your writing as whole. Stick to your guns on those items, but remember: this is a relationship. Just like any other relationship, that of critique partners requires empathy, understanding, generosity, conviction, and flexibility.

Now, go forth and be critiqued!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What do you think is the most important factor in how to find a critique partner that’s right for you? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/how-to-find-the-right-critique-partner.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Find the Right Critique Partner: The 6-Step Checklist appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 12, 2016

Is This the Single Best Way to Write Powerful Themes?

Part 9 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 9 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

The longer I study stories, the more convinced I am that the one single thing that sets apart the great stories from the meh ones is theme. What this means, of course, is that figuring out how to write powerful themes is possibly the most important job of any writer.

Theme is what a story is about. More than that, however, theme is why a story matters. Without a powerful theme that works in cohesion with the plot and the character development to resonate with readers in a relatable way, you will never create a story that lives beyond its two covers (if it actually gets far enough to have a cover, of course).

When, however, you find that sweet spot where theme grows so beautifully and organically at the crossroads of character and plot—the result is a story that instantly multiplies in depth, meaning, power, and cohesion. The biggest of stories without theme will always be a flop. But if you learn how to purposefully write powerful themes, you can take even the smallest, silliest, most escapist of all stories (like, say, a superhero comic book) and turn it into something great.

Why Do I Love Captain America: The Winter Soldier? Let Me Count the Ways

And that, of course, brings me to my favorite of all the Marvel movies to date—Captain America: The Winter Soldier. If Avengers was where the series kicked into high gear, Winter Soldier was where everything finally paid off in a film that is legitimately excellent in nearly every way you could ask for from a story in this genre.

Winter Soldier‘s prowess is due to several factors, including:

Rock-solid plotting and directing from the Russo brothers, including a taut suspense plot.

Spot-on placement of humor.

A well-developed antagonist, who didn’t even need a super-identity to be formidable.

Helping Writers Become Authors.

Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 8, 2016

15 (More) Reasons Writing Is Important–in Your Own Words

Is writing important? I posed that question two weeks ago in the post “5 Reasons Writing Is Important to the World.” Obviously, the conclusion I came to (after some sincere soul-searching) was that yes, writing and storytelling is a crucial part of building a better world and encouraging one another in our own quests for Truth. But I wasn’t the only one who came to that conclusion.

Is writing important? I posed that question two weeks ago in the post “5 Reasons Writing Is Important to the World.” Obviously, the conclusion I came to (after some sincere soul-searching) was that yes, writing and storytelling is a crucial part of building a better world and encouraging one another in our own quests for Truth. But I wasn’t the only one who came to that conclusion.

So did you guys.

Your response to that post was overwhelming. Personal story after personal story. Affirmation after affirmation. I was uplifted, encouraged, and empowered by the resonant “YES!” of your responses on the blog, Facebook, Twitter, and in emails. Today, I want to return to this important subject and share just a few of your great responses, so you can all find inspiration in them.

1. Writing Is Important Because… Life Is Meaningful

Thank you for this post!! It’s such an encouraging confirmation of what I’ve hardly dared hope by someone outside my own mind. I think as human beings, we need to know that our lives are intrinsically meaningful, and story has a beautifully intentional way of reflecting that meaning and purpose, even as it echoes the grander story of our lives at large.

2. Writing Is Important Because… Stories Tell Truths

YES. That’s all I can say. YES. Beautifully said, Katie. This is why I write—besides the wonder itching inside me to be expressed, the knowledge that I have the power to inspire others and satisfy a hunger screaming to be satisfied keeps me going.

Story is truth. Truth is the end of the road for every human being, and so it’s always beautiful—never unneeded, never empty. Truth’s funny that way, you know?

3. Writing Is Important Because… Language Has Many Positive Uses

4. Writing Is Important Because… Children Need Heroes

We read to our children 15 minutes every night before bed. I’ve heard that is one of the best things you can do with your child for development. Characters are great but parents also need to be their “protagonist.” Children imitate what they see in stories and those who are close to them. So when I woke up this morning I was pleased to see a book in my son’s hand. He was sitting peacefully on the couch skimming the pages of the book we read the night before. My other son took two books to daycare with him. One of them being 20,000 Leagues in the Sea…. He’s only 7.

5. Writing Is Important Because… It Reminds Us What’s Important

I am so glad you wrote this. This message is more important than ever. The world tells us to pay attention to the workings of power, as if the latest political developments were the most important things happening. But those things matter only because they affect real people—our little lives are so much bigger than we even know, and stories put us in touch with that. We were made for eternity, and the more confusing things get in the world, the more power struggles dominate our newsfeeds, the more we need to be reminded of what is really significant.

6. Writing Is Important Because… We Need a Sense of Something Greater

7. Writing Is Important Because… Writing Presents the Life Paradigm

As I’ve listened to your series on character arcs over the past week or so, I’ve been really struck by how much story is about Truth vs. Lie. A bit of light bulb for me! That whole realization just clicks so organically (to mix my metaphors) into how I see so many of the issues in life and in the wider world. Writing is a powerful thing.

8. Writing Is Important Because… Quality Craftsmanship Glorifies God

Sure, some people won’t get much out of any given story other than the story being good or bad or “meh.” But there’s a scene in the Book of Exodus where certain artisans are summoned to build the tabernacle. They’re chosen for the fineness of their craftsmanship, the beauty of their work directed to crafting items for the house of God. It’s important to me to be the equivalent of those artisans as a storyteller, where I wrought works in ink and pixels the quality of what they wrought in gold, silver, or bronze. That is why I come here.

9. Writing Is Important Because… Truth Is Worth Revealing

@KMWeiland This was fantastic! It’s a great reminder that stories are worth telling because truth is worth revealing. #thankyou!

— avery white (@praiseresound) July 25, 2016

10. Writing Is Important Because… the Subtlety of Story Is Powerful

Writing gives us the opportunity to say things that matter to us, and to dress them in allegorical fables that entertain as they argue a point. And the story form allows us a huge degree of subtlety in making that argument. Examples that the reader feels as though they are real. The ability to draw real life experience and the hopes and dreams and lives of real people into a fantasy. If we do it well enough.

11. Writing Is Important Because… It Reveals Ourselves

Yes! Our writing DOES matter. It reflects our inner being, our moral values, and, hopefully, our desire to inspire and encourage others for the good. Keep up the good work!

12. Writing Is Important Because… It Moves the World

13. Writing Is Important Because… Stories Are Arguments

It wasn’t until I saw your post that I really considered this, but I have come to the conclusion that storytelling is important. But if it is, we certainly can’t stop there.

Stories give us truths because they are arguments. There are no bad truths, but there are certainly ineffective arguments.

So how do you make an effective argument in a storytelling medium? I think the answer lies in story theory and general rhetoric, along with critical analysis of other such arguments.

14. Writing Is Important Because… It Is a Reflection of Our World

15. Writing Is Important Because… Sometimes It Saves Us

No matter if I ever do or don’t become an established author, I have to believe that there will always be souls out there in need of mental sanctuary or a hero among the pages of a book. Someone with no other way to discover what hope is, compassion, endurance of spirit, faith in something. No other way of finding inspiration in the face of all adversity to keep hanging on, knowing goodness, integrity, other virtues to be true because they read about it.

Yeah, yeah…I hear the noises about not believing everything you read. But tell that to someone with nothing else to draw strength from yet enough smarts to have a half decent grasp on what’s realistic, what’s not, and a Public Library card in their hand. The ones that derive their own courage from J.R.R. Tolkien or dream of some place beyond the slums because they read Ray Bradbury.

That persistence of wonder some of us experience when leaving the movies, read that last page and close the book… this is what matters though. Even if the rest of this world denies the significance of writing, books, movies, spinning yarns… as you said in this excellent post, keep fighting the good fight. Somebody has to. I’d like to think I am.

Not every story is perfect. Not every story is good. Not every story uplifts, clarifies, or empowers. But the good stories do. And when they do, they move the world. That’s what I want to write. How about you?

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How have stories impacted your life—as both a child and an adult—for good? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/15-more-reasons-writing-is-important.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 15 (More) Reasons Writing Is Important–in Your Own Words appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 5, 2016

How to Get the Most Out of Your Sequel Scenes

Part 8 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 8 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Sometimes just the mention of “sequel scenes” makes writers cross their eyes. Isn’t a sequel, you know, a followup to your first book? What does it have to do with individual scenes?

The answers to these questions are important, because the sequel makes up fully half of every scene and is crucial in creating deep character development, realistic cause and effect, and resonant themes. Today, we’re going to explore what happens when you neglect your sequel scenes, either by leaving them out of your story altogether, skimping on the cream, or just choosing the wrong sequels.

Scene Structure 101

Most of my regular readers are probably already familiar with the terminology of the sequel scene. But just in case you’re not, here are the basics.

The structure of every Scene in your story can be broken into two halves: scene (action) and sequel (reaction). (And, yeah, I apologize for the ridiculously confusing terminology; blame Dwight Swain.) Each of those halves are then broken into three sections apiece.

In the scene, your character has a (1) goal, which is met by (2) conflict, which ends in at least a (3) semi-disaster. This then prompts the sequel, in which your character (1) reacts to that disaster, ponders his new (2) dilemma, and comes to a (3) decision—which leads right into the next scene’s goal.

(For an in-depth exploration of scene structure, see my series How to Structure Scenes in Your Story.)

Most writers understand the scene half. Goal and conflict, baby! That’s the easy part. But sometimes, it can be easy to overlook the sequel—to your story’s detriment, as we can see in Alan Taylor’s Thor: The Dark World. Let’s take a look.

Where (and Why) Thor: The Dark World Fails to Deliver

Welcome to Part 8 of our exploration of the highs and lows of storytelling from Marvel’s popular movie series. Dark World was the first Marvel movie I saw in the theater post-Avengers, so to say I was highly anticipating it is a bit of an understatement. Walking out of the theater, I felt it was an enjoyable movie that had included all the elements I was hoping it would (Loki, Jane, Asgard, action, humor)—and yet, it hadn’t quite scratched my story itch. There was something about it that left me feeling unsatisfied.

Think I’m going to say it was because Dark World had weak sequel scenes? Head of the class for you!

But, first, the obvious highs:

I thought it was spectacularly gorgeous, one of the few movies where I noticed a decrease in visual quality from 3D (in which I viewed it the first time) to 2D.

Jane gave a deserving Thor a good whack (or two) in the face, for not sending her a postcard from NYC. (I was hoping she’d throw her cereal box in his face, but, hey, this works.)

The brother love between Thor and Loki! This was undoubtedly the best part of the film: the conflict between Thor’s wanting to trust the familial bond and knowing he can’t.

More Asgard—and more Heimdall.

The Dark Elves. They were a super-cool concept, everything from their doll-like masks to their Kursed battle fury.

And lows:

The Dark Elves. They weren’t taken advantage of in any way, which is really no surprise in a movie as busy and thematically scattered as this one.

The thematic scattering. I’d argue that the heart of the Thor movies’ theme is family—specifically brotherhood. But neither of the existing two movies have gotten a chance to sufficiently explore that, mostly because Thor’s doomed romance with the mortal Jane keeps eating up the screentime.

And, finally, and most importantly: the characters do. not. react. For every beautiful, interesting, scary, heart-rending event, there should be a HUGE sequel scene. And… there’s not.

The 3 Jobs of Your Sequel Scenes

Writers sometimes get hung up on the advice that “there should be conflict on every page.” You might feel it’s time for your characters to sit down and have a chat about what just happened, but then you hear that advice in the back of your head and you start fretting. “Where’s the conflict in this scene? What’s the character’s goal? Gah, I love this scene, but are readers going to think it’s boring?”

Short answer: no, they’re not. Not if you set up your sequel scenes wisely.

Here are the three things you have to take the time to show in your sequel scenes.

1. Use Your Sequel Scenes to Explore Character

The action half of the scene is where the plot happens; the sequel/reaction half is where the character development happens. Skip the sequel scenes, and you can be sure you’re skipping the most powerful aspects of your character’s arc.

Sequel scenes—the reaction half of scenes, the scenes with no action and no conflict—are routinely some of my favorites as a reader and viewer. What a character does or experiences is only interesting insofar as he reacts to it.

Easy Rule of Thumb: If he doesn’t react to it, it doesn’t matter.

Why Dark World Gets It Wrong: Think about how Thor and Jane never react to the fact that Thor’s mother Frigga died protecting Jane. Obviously, this is a huge event that should create ripples in both characters’ lives and in their relationship. But we get nada in the film. The only character who truly reacts to Frigga’s death is Loki (which is yet another reason Loki is usually considered the more compelling character).

How You Can Do It Right: Take a look at your scene structure. Does every action have a response period? Sometimes this will be a full-blown chapter in its own right; sometimes it may only be a paragraph or two. But everything that happens in your story must elicit a reaction from your protagonist and other pertinent characters. Otherwise, you’re cheating readers and cutting the emotional legs out from under your characters.

2. Use Your Sequel Scenes to Create Cause and Effect

Dwight V. Swain, originator of this approach to scene structure, wrote in his wonderful book Techniques of the Selling Writer:

[Your reader] demands that your character’s efforts have meaning. They must be the consequences of prior development and the product of intelligence and direction.

If you’re not using scene and sequel to create a tight weave of cause and effect, then what you’re creating is not a plot, but rather a random string of events. The sequel/reaction shows the effect of every scene/action’s cause. If you neglect either side of this dynamic duo, your story will start staggering around like a drunken pirate with one leg.

Cause and effect creates realism, it creates consequences, it enables suspension of disbelief. Without these elements, it becomes harder and harder to keep readers invested in the story world you’re trying to create.

Why Dark World Gets It Wrong: In this film’s defense, it did have a lot of ground to cover in just two hours: Jane’s illness, Loki’s fate, Frigga’s death, Odin’s revenge, Darcy’s intern, the Dark Elves’ backstory, etc. But, ultimately, that’s no excuse for skimping on the aspect of scene that is most important for grounding a story. How much better would all of these subplots have been with a little more grounding?

One of the best sequel scenes in the entire movie is the early scene when Lady Sif speaks to a melancholy Thor outside the tavern where his friends are celebrating their recent victory. It explains his emotional landscape and anticipates his motivation in the next scene for pursuing Jane—and it develops the minor character Sif into the bargain. How much better would the film have been with a few more such scenes?

How You Can Do It Right: Pay attention to the six-part weave of each Scene—goal, conflict, disaster, reaction, dilemma, decision. When each of these pieces are in place, it allows each moment in your story to build seamlessly into the next. You’ll never have to wonder if you’ve written an unnecessary scene. If it fails to fit into one of these six parts, you’ll know it’s unnecessary.

3. Use Your Sequel Scenes to Advance Theme

If the most important character development happens during your sequel scenes, then so does your thematic development—if only because character and theme must be developed side by side. Without quiet moments of reflection, irony, and subtext, the theme languishes on the back burner.

Theme lives in the spaces between your character’s actions. It lives in your story’s subtext. And subtext arises perhaps most richly in scenes of reaction, when your characters are exploring the consequences of their actions and the motivations that will prompt their next move.

Why Dark World Gets It Wrong: I love Jane Foster. She’s a thoroughly delightful character: funny, perky, sweet, feminine, brilliant, determined, awkward. But she’s just plain in the way of the theme. These movies should never have been conceived as love stories. Their burning heart has always been Thor’s difficult relationship with his adopted brother Loki.

It’s interesting that Loki actually does get the most interesting and complete sequel scenes in this movie (such as after he and Thor have escaped Asgard and share a fight and a few semi-fond memories while Jane is—conveniently—passed out in the bottom of the skiff). But because he got relegated to a subplot that’s squished in between all the story’s more action-oriented elements, the theme is ultimately just as short-changed as he is.

How You Can Do It Right: Your character’s reaction scenes are the perfect place to explore the Lie/Truth dynamic that is driving his inner conflict and evolving his personal development. This is where the arguments come to the fore, where the Mentor can advise, the Contagonist can tempt, and the protagonist can begin to see things more clearly.

Because proper scene structure affects every part of your story—plot, character, and theme—you can see how important it is to make sure you’re balancing it in every chapter of your story. Learning to write effective and well-placed sequel scenes might even spell the difference between a good book and a great book.

Stay Tuned: Next week, we’ll talk about how Captain America: The Winter Soldier used theme to knock its character development out of the park.

Previous Posts in This Series:

Iron Man: Grab Readers With a Multi-Faceted Characteristic Moment

The Incredible Hulk: How (Not) to Write Satisfying Action Scenes

Iron Man II: Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist

Thor: How to Transform Your Story With a Moment of Truth

Captain America: The First Avenger: How to Write Subtext in Dialogue

The Avengers: 4 Places to Find Your Best Story Conflict

Iron Man III: Don’t Make This Mistake With Your Story Structure

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Do you have a reaction / sequel scene following the most recent action segment in your story? Tell me in the comments!

The post How to Get the Most Out of Your Sequel Scenes appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 1, 2016

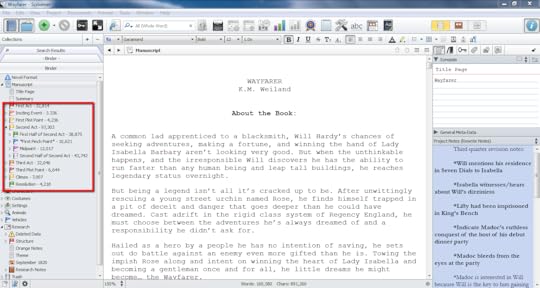

How to Use Scrivener to Edit Your Novels

As a writer, you need tools that help you organize your thoughts and eliminate distractions, so you can focus on what’s really important: the story. One of the best tools (of all time?) for this is the powerhouse writing software Scrivener. I started using it a few years ago, and it has transformed my writing process. But it does more than just help me me outline and draft; it’s great for editing too. Today, I’m going to show you how to use Scrivener to edit your way to a better story.

As a writer, you need tools that help you organize your thoughts and eliminate distractions, so you can focus on what’s really important: the story. One of the best tools (of all time?) for this is the powerhouse writing software Scrivener. I started using it a few years ago, and it has transformed my writing process. But it does more than just help me me outline and draft; it’s great for editing too. Today, I’m going to show you how to use Scrivener to edit your way to a better story.

Last year, I wrote a two-part series about how I use Scrivener to outline my novels and write my first drafts. Right away, you guys wanted a third post: how to use Scrivener to edit. At the time, I wasn’t far enough along in my Scrivener experience to have used it to edit a work-in-progress, so I had to hold off until I could report on how things turned out.

Last year, I wrote a two-part series about how I use Scrivener to outline my novels and write my first drafts. Right away, you guys wanted a third post: how to use Scrivener to edit. At the time, I wasn’t far enough along in my Scrivener experience to have used it to edit a work-in-progress, so I had to hold off until I could report on how things turned out.

And… I’m happy to report they’re turning out fine!

This is thanks in no small part to Joseph Michael—known in writerly regions as the Scrivener Coach and also one of the most generous and stand-up guys I know. Scrivener’s awesomeness is the result of its notoriously complex functionality. That means it does just about anything you can dream of—but first you have to figure it out. That’s where Joe and his detailed Learn Scrivener Fast course has come into the picture for me. He taught me how to use Scrivener—so I can teach you how to use it to edit your books.

Even better, I figured this week would be an appropriate time for this long-awaited post, since Joe has agreed to return (by your popular demand) for the third of what is quickly becoming an annual event around here: his free 60-minute Learn Scrivener Fast webinar, which I’m hosting this coming Thursday, August 4th, 2016, at 4PM EDT.

This is consistently one of the best free webinars I’ve ever been a part of. Joe absolutely crams it with helpful info for taking full advantage of everything Scrivener offers for streamlining and improving your writing (and editing!) process. It’s always a packed house (we nearly “broke” the webinar platform the first time out), so if you’re interested, grab your registration now.

6 Tips for How to Use Scrivener to Edit Your Novel

Following are my top 6 tips for how to use Scrivener to edit your fiction. Click on any image for a bigger view.

But, first, a bonus tip…

Tip #0: Simplify Editing by Writing Clean Drafts

Obviously, this is a writing tip more than an editing tip, but I promise it will keep you from ripping out all your hair come editing time.

What is a clean draft?

It’s a draft that is already as neat as you can make it.

And how do you do that without falling into the grip of rabid and utterly unproductive perfectionism?

#1: Outline

#1: OutlineOutlining is like editing before writing. If you’ve worked out most of the major story problems and know where you’re going before starting the draft, you’ll be able to avoid the vast majority of big first-draft problems.

#2: Fix Known Problems

Did you just write a scene you know isn’t working? Stop now, go back, and rewrite it. Too often, when you leave a problematic scene behind you, the problems only snowball into all future scenes.

Now, I’ll grant this one can be a sand trap for some writers, so use it with caution. You don’t want to get stuck editing the same scene over and over again with no forward progress. But if you know what the problem is and you know how to fix it, do so.

#3: Stop Quarterly for a “50-Page Edit”

Don’t just write your manuscript all the way through (unless you’re competing in NaNoWriMo). It’s way too easy to lose the forest for the trees as you get immersed in the minutiae of your prose. Stopping every quarter of the story (at the First Plot Point, Midpoint, and Third Plot Point) and editing what you have so far is a two-fold aid:

1. It orients you in the overall flow of your story.

2. It gives you a much tighter, cleaner first draft, since you’ve basically edited it three times before editing.

This is the approach I use for all my novels. It certainly doesn’t guarantee you’ll end with a super-clean, super-polished first draft. But it does guarantee that it’s much more likely.

Tip #1: Use Scrivener to Edit Your Rewrite Notes

And now… let’s talk editing. The first step is to gather any rewrite notes. These could be notes you’ve already jotted down or just ones that are floating in the back of your brain. They could be big fixes (e.g., cut this minor character, adjust timing on the Midpoint, or give the antagonist a backstory), or they could be relatively small tweaks (e.g., make sure the protagonist’s eye color is blue all the way through).

The fantabulous thing about Scrivener is that it allows you keep all your notes neatly organized in one file. No more flipping through half a dozen Word and yWriter files to find what you’re looking for!

While writing the first draft, I keep a running list titled “Rewrite Notes” in the Projects Notes section of Scrivener’s Inspector panel (on the bottom right-hand side of the screen). Some of these notes I’ll have already addressed during 50-page edits, but a lot of them will be left over for the actual editing process.

If an idea occurs to me while writing, it’s easy to simply jot it in the Rewrite Note section and keep on going. Then I can access and refer to the notes when I’m ready to start editing. They become, in essence, my “rewrite outline,” a handy checklist for making each necessary change.

Tip #2: Use Scrivener to Edit Your Story Structure and Word Count

Scrivener specializes in giving you a “big-picture view” of your story. It creates, in essence, an outline all its own, in the Binder section on the left, by listing all your chapters and scenes. This makes it easy to look at your story’s overall structure. You can:

1. Make sure all the important structural turning points are accounted for.

2. Make sure the timing is accurate.

There are seven major structural moments to be particularly aware of:

1. Inciting Event (12%)

2. First Plot Point (25%)

3. First Pinch Point (37%)

4. Midpoint (50%)

5. Second Pinch Point (62%)

6. Third Plot Point (75%)

7. Beginning of Climax (88%)

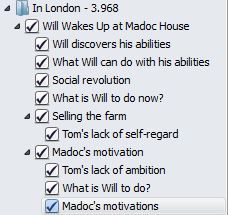

When I initially set up my outline in Scrivener, I create folders for each of my major structural moments and mark them with flag icons (square flags for each of the Three Acts; triangular flags for each of the turning points within those acts). Then I build my chapters and scenes within those folders.

To make sure I’m staying (close to) on track with the timing of each event, I add each scenes’ word count to its title, so I can see at a glance where I’m at. This shows me where I need to trim word count and where I may need to flesh out a section.

Tip #3: Use Scrivener to Edit Chapter and Scene Order

This is one of my all-time favorite Scrivener tricks. Rearranging chapter or scene order—or, even more tricky, the order of events within a single scene—can be mind-bogglingly difficult to get your head around when you can only see one screen’s worth of your story at a time.

Scrivener lets you rearrange chapters and scenes merely by clicking and dragging within the Binder. Don’t like the new order? Changing it back is as simple as clicking and dragging once more.

Even better, you can break down tricky scenes into beat-by-beat sub-documents, so you can see what your scene is really all about. Then you can click and drag those sections to remove repetitive elements and achieve the most powerful progression of events—as I did when editing a tricky dialogue scene in my historical-superhero work-in-progress Wayfarer.

Tip #4: Export Your Critique Partners’ Preferred File Types

Once you’ve completed your own edits within Scrivener, you then need to convert it to the proper format to share with your beta readers, critique partners, and editors. The one major drawback, as I see it, to Scrivener is that it does not allow you to send an editable Scrivener file back and forth between users (mostly due to the file sheer size). This means you must convert to some other file type.

The good news is that Scrivener’s export capabilities are vast—everything from Word docs to mobi and epub and everything in between. The bad news is that exporting can be tricky (especially if you’re trying to format an e-book, although it’s totally worth the effort).

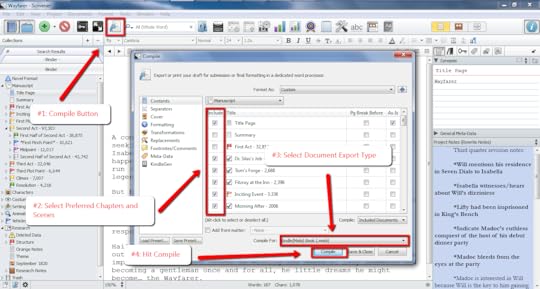

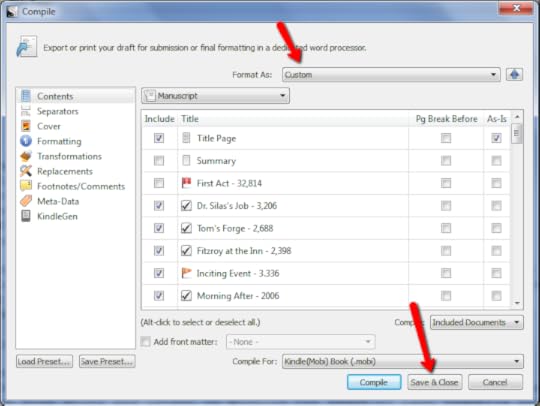

Others (including Joseph Michael) are much better equipped than I am to explain the intricacies of exporting into e-book formats. At this stage in the editing game, however, all you need to do is export a no-frills Word doc you can share with your critters. The steps for that are pretty simple:

1. Click the compile button.

2. In the compile box, click the chapters and scenes you want to include in the export.

3. Select the type of document you want to convert to.

4. Hit compile and select where you want to save the new file.

There are all kinds of additional options for adding a cover image and formatting the text appearance, but chances are, at this point, you’ll find it easiest to do most of that in Word once you get the doc converted. Now you’re ready to send it out for feedback!

Tip #5: Use Scrivener to Edit Word’s Track Changes

One of Microsoft Word’s best features is Track Changes, which records the changes your critique partners and editors make to your document and allows them to add comments. At this point, Scrivener doesn’t offer anything of competitive similarity, which means Word is still the best program to use for sharing critiques.

This means you need a system for switching between Word’s Track Changes and your manuscript in Scrivener. One option is to simply use Word exclusively as your manuscript’s master file once you reach the editing phase. I prefer not to do this, since I lose the accessibility of my Scrivener notes and I’d just have to plug it back into Scrivener eventually anyway for conversion to e-book formats.

Depending on the volume of corrections and comments you’ve received from your critique partners, you may find it easier to simply switch back and forth between Word and Scrivener, making quick corrections and adding footnotes in Scrivener to guide you to making the bigger changes later.

If you’re dealing with a massive amount of changes, then a handy trick is to take a screenshot of the pertinent sections of your Word doc, then click and drag the images into Scrivener’s Research binder. You can then use the split-screen feature to show both the images with the Track Changes and your manuscript side by side for easy reference.

Tip #6: Use Scrivener’s Snapshots Feature to Preserve Old Versions

Scrivener is very committed to making sure you don’t lose any important work, either unintentionally (it auto-saves every five seconds) or through your own misjudgment. Before you make major changes to any given scene, use the Snapshots feature in the Inspector on the right-hand side to save the current version.

If you find you liked the old version better after all—or if you just need to reference it for any reason—you can easily find it in the Snapshots section and “roll back” to revert to the earlier version. It makes the whole process of revision incredibly risk-free.

My complete storytelling process—from outlining to writing a first draft to editing—has been improved thanks to Scrivener. I’m an unabashed fan of the program because I’ve seen first-hand how powerful it is for streamlining my writing and editing processes, showing me the big picture of my work, and helping me stay out of my own way as I work toward my best stories.

Give it a try! The program is a steal at $40 and offers a free 30-day trial—which is perfect if you’re new the program and want to give it a try before the free Learn Scrivener Fast webinar this Thursday, August 4th, 4PM EDT.

Don’t forget that attendance will be limited at the webinar, so sign up early to reserve your spot. And while you’re waiting, you can also play around with this free Scrivener template created by Stuart Norfolk and based on my books Outlining Your Novel and Structuring Your Novel. Have fun!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Do you use Scrivener to edit your stories? What are your best tips? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/how-to-use-scrivener-to-edit-your-novels.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Use Scrivener to Edit Your Novels appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 29, 2016

Don’t Make This Mistake With Your Story Structure

Part 7 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 7 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

I talk a lot about how important story structure is. But let’s be honest. Story structure is a complicated beast. Few stories ace every single beat to perfection every single time. I’ve read (and watched) incredible stories that were incredible in spite of the fact they were working off a sometimes wobbly narrative structure.

Although you should always be working toward the best story structure possible, if the challenges and constraints of your particular story are keeping it from glistening perfection, that probably isn’t going to make or break the deal for readers.

Unless… you’re committing what is, in my book, the single worst story structure mistake you can make: leaving your protagonist entirely out of the structure.

Why Iron Man 3 Has the Worst Story Structure of Any Marvel Movie

Not all of the Marvel movies are paragons of story structure (Captain America: The First Avenger, in particular, skipped its entire Second Pinch Point). But most of them are examples of how the occasional structural gaffe can be overlooked in favor of a story’s other favorable qualities.

Iron Man 3 is the exception.

Now, there are things I do like about this story.

I appreciate Tony’s PTSD and the fact that his actions—both for good and ill—in previous movies are having decided consequences.

The Mandarin rocked. Until, you know… he didn’t.

More Happy! (Though, I think, under the circumstances, I would have opted for more Jon Favreau instead.)

Little boy Harley Keener was a delightfully different (and capable) foil for Tony.

But none of them can make up for the story’s fundamental story structure problems.

Iron Man 3 makes that non-negotiable mistake I was talking about. It offers up a structure that has almost nothing to do with its protagonist—Iron Man inventor Tony Stark—which means its conflict isn’t driven by the protagonist.

Don’t Know What Your Story Is About? Look at Your Story Structure

In certain complex storylines, it can be difficult, at first glance, to know exactly what a story is about—what its throughline is. But the answer is always found in the story’s structure. Whatever plotline or character is most active in the plot’s turning points, that is what the story is about.

A great (non-Marvel) example of this is Martin Scorcese’s The Aviator. This is a sprawling story that, on the surface, seems to be about many things (Howard’s Hollywood career, Howard’s relationship with Katherine Hepburn, Howard’s OCD). But the plot points back up the emphasis of the title by showing us this is really a story about Howard’s love of aviation.

Same goes for my all-time favorite movie John Sturges’s The Great Escape, which artfully gives prominence to Steve McQueen’s decidedly subplot character by making sure that subplot shows up at every single major structural beat.

Now consider Iron Man 3‘s story structure:

Inciting Event: Aldrich Killian (the antagonist) petitions Tony’s girlfriend and CEO Pepper to fund his brain-hacking project Extremis.

Where’s Tony? Oh, yeah, hiding out in his basement being an obsessive insomniac.

First Plot Point: Tony’s bodyguard Happy follows a suspicious character, somebody blows up, Happy ends up in a coma.

Where’s Tony? Gift-wrapping Gigantor the Stuffed Rabbit for Pepper’s Christmas present. He finally impacts the main conflict when he calls out the Mandarin and gets his house blown up, but it’s a long time coming.

First Pinch Point: Pepper learns Aldrich is working for the Mandarin.

Where’s Tony? Crashlanded in Tennessee, trying to get his suit to work again. He does have a nice pinch, in which he battles the guy involved in Happy’s injury. But his storyline is totally untouched by the plot’s most important revelation up to this point.

Midpoint: The Mandarin publicly challenges the President on national TV. Meanwhile Pepper is captured.

Where’s Tony? Oh, he’s off gleaning a few clues that will eventually lead him to Aldrich’s base. But that’s about it. He doesn’t know about the Mandarin’s challenge or Pepper’s capture, which means these huge events have no power to drive the plot.

Second Pinch Point: Tony crashes the Mandarin’s base, is captured, and learns about Pepper’s capture.

Where’s Tony? Finally, he’s in the main game!

Third Plot Point: The President is captured and delivered to Aldrich.

Where’s Tony? Thankfully, he’s at least off doing related things, like rescuing all the people in the President’s plane. But the Third Plot Point should have been a moment that hit him as hard possible on a personal level. He’s not directly responsible for or involved in the President’s capture, so it lacks the bite it might have had. Plus, it decidedly pales in comparison to Tony’s personal loss of Pepper earlier.

Climax: After bringing in all his suits to fight Aldrich’s exploding minions, Tony finds Pepper—who has been injected with Extremis and turned into an exploding person. He does battle with Aldrich to save her.

Where’s Tony? Right where he should be.

Climactic Moment: Pepper miraculously survives a 200-foot fall and emerges just in time to save Tony and kill Aldrich.

Where’s Tony? Well, he’s not ending the conflict, that’s for sure. His line to Pepper pretty much sums it up: “I got nothing.”

5 Reasons Your Protagonist Must Drive Your Conflict

Now you tell me: what’s Iron Man 3 about? Just by looking at the bare bones of the story structure, you sure wouldn’t know it was supposed to be about Tony Stark. And the story suffers as a result.

Consider five important reasons your story needs your protagonist front and center within its structure.

1. Cohesion Within the Conflict

A structure that’s all over the place indicates a story that’s all over the place. Story structure should never be a random collection of events that “fit” the requirements of the various structural moments. Every structural moment must be part of a cohesive whole that creates a clear image of the entire story.

If your protagonist isn’t at the center of that image, then you have to question whether or not he’s really the protagonist.

2. Forward Momentum

Your story follows your protagonist. If he’s not moving forward—if he’s not driving the story forward by creating a string of causes and effects related to the story goals he’s pursuing—then the story readers are participating in isn’t going to be moving either. It’s possible there’s lots of movement happening in the background, where other characters are driving the plot. But that’s not the show readers are privy to, or, even if they are, it’s not the show you’ve told them they should care about most.

3. Proper Foreshadowing

Strong foreshadowing is inherent within good structure: the beginning sets up the end. When one character controls one plot point, only to have another control the next one, the results seem chaotic because they are. The story isn’t correctly setting itself up.

Even worse, when you start out with an Inciting Event (the question that prompts your entire story) that isn’t bookended by a correlative Climactic Moment (the answer to the Inciting Event’s question), then you have a plot that simply doesn’t work.

4. Interesting Scenes

The most interesting scenes result at the crossroads where your protagonist meets the conflict. If he’s not meeting the conflict, then you’re leaving a ton of great scenes on the table. Chances are good your protagonist is just meandering around the neighborhood doing busy work to fill up his time—and your book. Chances are also good your readers are bored.

5. Thematic Resonance

Structure, character, and theme are integrally related. Mess up one and you’ve messed up all three. When the structure is out of whack because the most important character isn’t present, you can be sure your theme has gone a little wonky on you as well.

Your story’s central conflict presents the external metaphor for your protagonist’s inner journey. But if he’s absent for some or most of that external journey, his inner development can’t help but be stunted.

Every story must have a protagonist. Even if that character shares the stage with other prominent characters—or even co-protagonists—he must be present at the structural turning points. Otherwise, the story either isn’t about him or is missing a vital playing piece.

If you’re writing a particularly complex story, you may choose to create a single throughline to act as your story’s spine—as do The Aviator and The Great Escape. Or you may choose to give all characters equal prominence by making sure they all have an important role or independent beat at the turning points—as does Brent Weeks’s Blinding Knife.

But whatever you do, don’t let your protagonist suffer in the background of your story structure. Bring him fully on stage, and at least give all his suffering a spotlight!

Stay Tuned: Next week, we’ll talk about how Thor: The Dark World robbed itself of thematic depth by choosing the wrong sequel scenes.

Previous Posts in This Series:

Iron Man: Grab Readers With a Multi-Faceted Characteristic Moment

The Incredible Hulk: How (Not) to Write Satisfying Action Scenes

Iron Man II: Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist

Thor: How to Transform Your Story With a Moment of Truth

Captain America: The First Avenger: How to Write Subtext in Dialogue

The Avengers: 4 Places to Find Your Best Story Conflict

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What does your story structure look like? Is your protagonist a prominent player at every turning point? Tell me in the comments!

The post Don’t Make This Mistake With Your Story Structure appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 25, 2016

5 Reasons Writing Is Important to the World

I find myself a little trepidatious as I sit down to write this post. I just downed my morning coffee, and the caffeine is kicking in and latching onto my nerves, making my fingers just a little trembly.

Why am I nervous?

Because this is such a big post. And such a deeply personal post.

Let’s face it, people, the world’s a mess right now. I think the vast majority of us agree on that, to one degree or another, regardless our worldview. And what are we doing about it? What can we do about it?

We’re just average people. Normal people. People who get scared and confused. People whose own little howling demons somehow have the ability to overwhelm us even more easily than the monsters that seem to be crunching our world for breakfast right now.

We’re just folks who put words on paper. We’re just people spinning little tales that make us happy or fulfill our own fantasies: romance and superheroes, dragons and femme fatales. We’re just writers.

That doesn’t seem like much right now. It certainly doesn’t seem like enough.

Why Am I Writing? What’s the Point?

Stories have always been my language. I told myself stories all through childhood. I read voraciously. I playacted constantly, pretending I was characters in my favorite books. My imagination spun webs of wonder and possibility all around me. Life was never just what it was. It was always more. It was always a portal to something bigger, something that mattered: a story.

I thought that’s what the world was. I thought that was how everyone saw the world.

Then, of course, I grew up. I became a writer, not so much because I wanted to do anything big and important, but because that something big and important was already a part of me. All that passion and wonder of storytelling was something that just flowed out of me. I couldn’t help but share it.

Except it seemed most people didn’t see stories the way I did. I’d close a book or come out of a movie, and the world would be shining because of the power I’d just experienced—the portal to immortality I’d just glimpsed. But others would just shrug. “Yeah, it was fun.”

Except it seemed most people didn’t see stories the way I did. I’d close a book or come out of a movie, and the world would be shining because of the power I’d just experienced—the portal to immortality I’d just glimpsed. But others would just shrug. “Yeah, it was fun.”

Slowly, disillusionment crept in. I have always maintained, based on my own experiences as much as anything, that stories should be more than mere entertainment and escapism. That, indeed, they must be. Yet everywhere I looked, it seemed that’s all other people were getting out of their stories.

Is that all stories are? A soporific drug to numb our minds against the difficulties, confusion, and sometimes downright horror of our lives?

Is that what I’ve spent my life in pursuit of, as both a reader and a writer? Am I and a small handful of others the only ones who see stories as more and are affected by them on a soul-deep level?

Are Stories a Force for Evil?

Depressed yet? Let’s take it one step farther. Disillusioning as it may be to think of stories as a mere neutral force in the world, what if it’s worse than that? What if they’re actually a force for evil?

Anjelica Huston’s wicked stepmother has a line in Andy Tennant’s Cinderella retelling Ever After that always makes me snicker. She self-assuredly puts down her step-daughter with the pert declaration:

People read because they cannot think for themselves.

It’s obviously a ridiculous statement. Just the reverse is true.

Isn’t it?

No culture in history has ever been so saturated with stories as ours. Books, movies, television. Mass media connects us all and is undeniably used as a tool for propaganda. As writers, we are influenced by popular fiction in all its forms, even as it grows ever more violent, ever more gratuitous.

No culture in history has ever been so saturated with stories as ours. Books, movies, television. Mass media connects us all and is undeniably used as a tool for propaganda. As writers, we are influenced by popular fiction in all its forms, even as it grows ever more violent, ever more gratuitous.

Sometimes I find myself asking, “Am I sharing my truths—or someone else’s?” Could it be that my stories and I are only contributing to society’s downward spiral. Am I helping at all? Or am I maybe even hurting?

A few weeks ago, I watched the documentary Kingdom of Dreams and Madness about Studio Ghibli and beloved Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, as he was working on what was thought to be his final film, The Wind Rises, about the inventor of the World War II-era Zero fighter plane. In it, Miyazaki mused that animation is like aeronautics: