K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 57

July 18, 2016

4 Ways to Verify Your Story Concept Is Strong Enough

All story concepts are not created equal. Even once you get past all the boring, been-there, and just plain blah ideas to the point where you’ve discovered something legitimately interesting and cool—that’s not enough either. Many a cool story concept has gone on to be a wasted story.

But that’s not going to be you! Today, I’m going to show you how to vet your story concept ideas with a simple four-question process.

A strong story concept is the first item you have to check off your “must-have list” on your way to the kind of story agents accept, editors buy, and readers love.

On a certain level, story concept is one of those things that’s so intuitive and foundational, we almost take it for granted. You can’t have a story without a concept. Concept is story. It’s the first kernel of an idea, which, once planted in your imagination, grows into an entire book.

As a writer, you no doubt have story concept after story concept springing up in your brain, on an almost daily basis. Some of them are pretty bland, but some are special right from the get-go.

Here’s how to weed out the runner-up ideas on your way to the winners—and then refine your best idea into a story concept that can support a deep and nuanced novel.

1. What Is Your Story’s Concept?

A story concept is an utterly simple, even general idea. It’s your story at its most basic level. It’s the what-if question that piques your curiosity and pulls you into exploring its potential developments and ramifications. It is not a specific story idea. That’s your premise, and that comes later.

A good story concept is:

Unique

At least, to a certain degree—you’ll get more unique when you start adding story specifics in the premise, regarding your characters and conflict.

Dichotomous

It raises a question. It’s interesting because it presents an inherent sense of conflict or something out of place.

Simple

If the basic idea can’t be stated in one short phrase, it probably isn’t clear enough in your own mind yet. This doesn’t mean the story itself won’t be complex, but the weave of various thematic threads will come later in the process.

Real-Life Story Concepts

Consider a few examples of solid story concepts:

Star-crossed lovers commit suicide rather than let their feuding families tear them apart.

World War II soldiers track down the only survivor from amongst four brothers.

Geeks and gamers compete in a virtual contest.

A man and his son navigate a bleak post-apocalyptic world.

A young woman is cursed into old age by a jealous witch.

Aliens invade the Old West.

These should all be recognizable—because they’re all solid concepts from well-known stories.

That last is the one I particularly want you to pay attention to—because it’s the only one of the bunch that was also a big, fat flop. I am, of course, talking about Jon Favreau’s Cowboys & Aliens from a few years back.

On its surface, it was an incredibly fun, can’t-miss story concept.

But it did miss. Big time.

It’s a cautionary tale of how (and why) a high-concept story premise does not guarantee a good story. In fact, just the opposite: the higher your concept, the more responsibility you have to take advantage of it. If you fail, readers will notice the holes and judge your story all the more harshly for them.

So how can you avoid a similar disaster with your story concept? Use the following three questions to make sure you’re creating the right kind of story for your idea and taking advantage of all its possibilities.

2. Is Your Concept More Than a One-Trick Pony?

Once you’ve found a story concept that excites you, the first aspect you must examine is its potential for development. Once you get past the basic setup of the concept, does it raise still more intriguing questions and present interesting avenues to explore?

A good story concept doesn’t end with itself. Rather, it continues to generate idea after idea.

Implicit in this question, of course, is more than just the necessity of verifying that the concept has the wheels to keep rolling. You, as the author, also have push yourself to keep looking for those interesting possibilities and then taking advantage of them.

Story Concept Success:

Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One uses its high-concept premise of an immersive virtual reality competition to develop and explore many possible aspects of such a technology through the game itself, but also its effects upon the real world, its criminal element, and its monetization. It uses the concept to create a fully detailed and explored world.

Story Concept Failure:

Cowboys & Aliens was a one-note song. Instead of developing its concept—or, heaven forbid, its characters—it just kept screaming, “Aliens!!!” over and over and over again. The story raised precious few character-oriented questions, and those it did all had the same answer: Aliens.

3. Does Your Concept Have Something to Say Thematically?

The best stories are not really about what they say they’re about. Concept-driven plot is a visual and external metaphor for the characters’ inner journeys. In short, what stories are really about is always theme.

If your story concept doesn’t have the ability to present a “story beneath the story,” then it’s going to be cheap escapism at best. If you’re lucky, it’ll be entertaining enough to keep readers’ attention for the duration. But, frankly, if you’re not getting them to invest on a deeper level—if you’re not engaging both their intellect and their emotion—then you’re wasting two of your most powerful opportunities for keeping them invested in your story.

Simple plot mechanics aren’t enough to truly engage readers. You need to give them more—and that starts with your story concept. Take a look at your idea. Does it present the opportunity to explore interesting aspects of the human experience? Does it present inherent moral, psychological, or naturalistic Lies or Truths? Does it raise questions about life, choices, and consequences?

In short, does it have something to say?

If not, then the idea probably doesn’t have the strength to carry an entire novel. In order to fill out an entire story, you’ll be forced to resort to banging away at that one-note drum from the previous question by harping on the “coolness” of your premise, over and over again, instead of going deeper and wider with your plot, character arcs, and theme.

Story Concept Success:

The Road, Cormac McCarthy’s acclaimed post-apocalyptic novel, about a man and his son wandering and surviving in a barren and hostile world is high concept. But this is never a story about its concept. It uses that idea as merely a jumping-off point for exploring its characters, their choices, and the consequences they are faced with at every turn. This novel uses a premise similar to any number of post-apocalyptic stories, but it rises above all of them for the simple reason that it is an exploration of character and theme.

Story Concept Failure:

Cowboys & Aliens had little to nothing to say thematically. It created a couple potentially interesting character situations (the outlaw protagonist’s past misdeeds and unexpected opportunity to redeem himself else; the tyrannical, bigoted rancher’s relationships with his worthless son and unappreciated adopted son). But instead of developing these interesting human stories, it kept pointing at its initial concept: “Look! Aliens! Isn’t this cool?” Yep, it was cool when the title was unveiled. But I think we’re all pretty much over it by now.

4. What Is Your Concept Best Suited For?

Once you’ve verified that your story concept is deep enough to keep asking questions—and once you’ve created a compelling human story as the vehicle in which to explore this uncharted wilderness—your next task is to make sure you choose the right type of story for your concept.

Because a story concept is a general idea, it can potentially be applied to just about any kind of story. Romeo & Juliet could have been a black comedy. Saving Private Ryan could have been horror. Just by tweaking your approach to your story concept, you can potentially end up with any vast number of completely different stories.

Analyze as many angles as you can think of. Think about different genres, different narrative tones, different attitudes to the inherent themes. Which options fit your initial conception of the story? Which options bring even more possibilities to the table?

If you pair the wrong concept with the wrong story, the results can be disappointingly dysfunctional. You can write your way through the entire first draft before realizing you haven’t been able to take full advantage of your cool idea.

Story Concept Success:

Diana Wynne Jones’s beloved YA fantasy Howl’s Moving Castle is a whimsical, often humorous adventure. Had she turned it into something darker or more serious, it might still have been a good story, but it would not have been the same story. Her characters—particularly the vain and irresponsible Howl—would have necessarily been represented much differently in a more serious story.

Story Concept Failure:

As it stands, Cowboy & Aliens should totally have been camp. Humor spices up any story, but when you start out with a premise as delightfully farcical as aliens invading the Old West, it’s simply a wasted opportunity to play it too straight (especially if you’re not prepared to deal with deeper, darker themes).

How’s your story concept looking in the light of the answers to these four questions?

Is it solid and exciting?

Is it teeming with possible avenues for you to explore?

Or is it still just sitting there trying its best to look cool?

Finding a story concept that can go the distance is the difference between a story you’ll finish and sell—and a story you won’t sell and may not even be able to finish. Take the time to vet your ideas before you start that first draft and make sure you’re taking advantage of every single opportunity presented by your best story concepts.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How does your story concept stack up against these questions? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/4-ways-to-verify-your-story-concept-is-strong-enough.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 4 Ways to Verify Your Story Concept Is Strong Enough appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 15, 2016

How to Write Subtext in Dialogue

Part 5 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 5 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Good dialogue comes down to five factors:

1. Advances the plot.

2. Accurately represents characters.

3. Mimics realism.

4. Entertains.

5. Offers subtext.

These are also pretty much the “levels” in which we master dialogue. When we start out learning to write, our main concern is that the dialogue helps us tell the story. That’s the White Belt of Dialogue. Along the way, we start mastering the other levels, until finally we arrive at our Black Belt examination: Learning how to write subtext in dialogue.

Think of subtextual dialogue as the secret initiation rite of writing. It opens up a door to a whole new mansion of storytelling possibilities—everything from subtlety to irony to thematic significance. Even better, subtext helps you further refine each of the previous four levels of dialogue.

Ready to level up?

What Does Captain America: The First Avenger Have to Say About Dialogue?

Welcome to Part 5 of our ongoing series exploring the pros and cons of Marvel’s storytelling within its cinematic universe. With the exception of Iron Man, none of Marvel’s Phase One films are sincerely good movies in and of themselves. But, personally, I’ve enjoyed every single one of them, and First Avenger is probably my favorite. Mostly, this is for subjective and personal reasons:

It’s a historical story set during World War II, so I was already half-enchanted by it before it even came out.

It has steampunk sensibilities.

It’s Captain America. (After Winter Soldier came out, I mused, in all sincerity, to someone I know that, after much thought, I’d finally concluded I liked the Captain America character best of all the Avengers. She burst out laughing in my face. Apparently, this was not a surprise.)

One of you just might have sent me Captain America stickers. ;)

Steve Rogers isn’t a flashy character. He isn’t anywhere near as stylish, interesting, or entertaining as Tony Stark. But the very fact that such a straightforward, gee-whiz-golly do-gooder can be presented as a character every bit as compelling, relatable, and thought-provoking is a testament to the strength of the writing. He has become the cornerstone character of the entire cinematic universe, and his sequels are unquestionably the strongest entries in the series.

Now, First Avenger isn’t quite as clean cut as its hero. It makes some major missteps structurally in the second half—most notably, in completely skipping its Second Pinch Point (which dominoes into problems in the Third Plot Point and Climax—which many people complained felt like a new story unto itself, designed specifically to set up The Avengers).

It’s not a daring or innovative movie; it’s conservative in its storytelling and all its beats. Its villain is both a little too evil and a little too easily overcome. And none of its action sequences are particularly memorable. (It does get points, though, for introducing one of the series’ most enduring and interesting female characters in Peggy Carter.)

With all that said, however, one of the reasons First Avenger works as well as it does in laying the groundwork for everything to follow is because it presents some very nice dialogue techniques throughout. Today, let’s take a look at a few of my favorite examples and how you can use them to learn how to write subtext in dialogue.

Rule #1: Don’t Say What You Mean

Subtext is all about what isn’t said. When writing dialogue, our first impulse is often to spell out exactly what’s on the characters’ minds. “I’m so mad at you right now!” or “I love you!” or “My backstory Ghost is making me so miserable and messed up. Whaaa!” (Don’t laugh. It’s done all the time.)

Try This: Go through every conversation in your manuscript and identify the point. What is the one thing the characters are wanting to say? Underline any place where they actually spell it out in on-the-nose dialogue. Now try to come up with a way to say the same thing without saying it—by coming at it sideways, by saying the exact opposite, or by implying it through body language or narrative.

Like This: One of my all-time favorite dialogue exchanges anywhere is the bar scene late in the movie, when Peggy’s red dress gets everyone’s attention. She walks up to Steve and his newly rescued pal Bucky, who immediately starts flirting with her. Steve doesn’t say a word. The entire exchange is between Peggy and Bucky—but the subtext is all about what Peggy and Steve really want to say to each other. Instead of an on-the-nose exchange in which Steve says, “Hey, we should be a couple and go out after the war,” this little gem is what we get instead:

Peggy [to Steve]: I see your top squad is prepping for duty.

Bucky: You don’t like music?

Peggy: I do, actually. I might even, when this is all over, go dancing.

Bucky: Then what are we waiting for?

Peggy: The right partner. [leaves]

Bucky [to Steve]: I’m invisible. I’m turning into you. It’s a horrible dream.

Rule #2: Bring Dialogue Full Circle

Say something once and it means exactly what it means. Say it twice and it begins to take on new, even iconic, meanings. Snippets of dialogue that can be repeated at crucial junctures can frame the entire story and bring it full circle thematically.

Try This: See if you can identify dialogue in the beginning of your story that can be taken at face value—and then repeated later on in another situation, where its meaning is doubled thanks to the subtext of the first iteration.

Like This: First Avenger uses this technique several times, notably with the “right partner” line from the example above. In that scene, Peggy is repeating an earlier statement of Steve’s, in which he indicated what he was looking for in a romantic relationship. Her return to the same line of dialogue here allows her, in essence, to provide a direct response to his earlier statement without its being on the nose, as it would have been had she immediately responded in the initial scene.

Other repeated lines are Steve’s catchphrase “I could do this all day” (as he’s getting the stuffing beat out of him) and his earnest inquiry, “Is this a test?”

Rule #3: Surprise Me

Subtext (and humor) arises out of the dichotomy between the expected and the unexpected. When a character responds in a way readers don’t expect, the result is inevitably both amusing and enlightening.

Try This: Look for areas in your dialogue exchanges where one character asks another character a straight-up question with an obvious answer. What would happen if you switched out the answer for something less obvious and on-the-nose?

Perhaps the second character misunderstands (deliberately or not). Or perhaps he responds sarcastically or ironically. Perhaps he lies. Perhaps he just plain ducks the question because he doesn’t want to answer it. All of these options present interesting possibilities for entertaining dialogue that actually says more about your characters than most straight-up answers ever could.

Like This: Cap is a pretty straightforward guy himself, so this technique isn’t used overmuch in this movie. However, his misunderstanding of Howard Stark’s “fondue” invitation to Peggy is humorous, while doing double duty in speaking to his romantic interest in her (“So you two? Do you? Fondue?”). It’s followed up in subsequent scenes that, again, allow the dialogue to be about their relationship without actually spelling it out.

We also have the humorous moment when the obviously German Dr. Erskine reacts to Steve’s inquiry about his origins by ingenuously responding, “Queens. 73rd Street and Utopia Parkway.”

Rule #4: Understatement and Irony

Sometimes when you need a character to be clear about what he’s saying, you can still avoid on-the-nose dialogue by employing understatement or irony. When this kind of dialogue is done well, readers always understand exactly what the character means, but they also get a little extra bang for their buck thanks to the subtlety of the delivery.

Try This: Look for exchanges where characters make absolute statements. (“I’m a three-time world champion.” “She dumped me.” “This is the best restaurant.”) Now brainstorm ways to slant these statements using understatement or irony.

Like This: Steve’s first big (unauthorized) mission has him rescuing captured Allied soldiers from a Hydra base. His outfit and methods immediately mark him as unorthodox. One of the soldiers—Dum-Dum Dugan—asks incredulously, “You know what you’re doing?” There are two obvious answers to this. Steve could either have offered the expected and comforting lie, “Yes.” Or he could have told the truth about being a “dancing monkey” with zero combat experience.

Instead, he tells a different truth with a totally different subtextual meaning. He pauses, then says nonchalantly, “Yeah. I knocked out Adolf Hitler over 200 times.” It’s a delightful bit of irony that speaks to his inexperience without admitting to it, while also slyly referencing his true ability, since the only reason he was knocking out Hitler in the stage show was because he’s a one-of-a-kind super soldier. That’s four layers of meaning in one simple line.

The truth is this: there’s a different dialogue technique for just about any situation you can dream up in your story. But the same five rules (mentioned at the top of this post) apply in all of them. If you can master Level 5—the art of how to write subtext in dialogue—you’ll lift your story and your writing to an entirely new plane.

Stay Tuned: Next week, we’ll talk about why one of The Avengers‘ greatest achievements is its vivid interpersonal conflict.

Previous Posts in This Series:

Iron Man: Grab Readers With a Multi-Faceted Characteristic Moment

The Incredible Hulk: How (Not) to Write Satisfying Action Scenes

Iron Man II: Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist

Thor: How to Transform Your Story With a Moment of Truth

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What is your favorite trick for how to write subtext in dialogue? Tell me in the comments!

The post How to Write Subtext in Dialogue appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 11, 2016

7 Reasons You Need Story Theory

Just as in fiction itself, the writer’s life is marked by several major turning points–perhaps the most important of which is discovering story theory.

Just as in fiction itself, the writer’s life is marked by several major turning points–perhaps the most important of which is discovering story theory.

In the story of your writing life, the Hook, of course, is that moment when you find yourself entranced with your first story idea. Maybe you were three years old–as I was–spinning yourself a tale in a treehouse at a family reunion (which just happens to be my earliest memory). It’s the beginning of everything: a tantalizing fascination with the unknown possibilities of what’s gonna happen. It pulls you in and never lets go–just as a good story should.

The Inciting Event is when you first put pen to paper. Now you’re not just an Imaginer–you’re a Writer.

Then comes the First Plot Point: the moment when you realize there’s actually a method to the madness of writing. There are rules to follow. Goodbye, head hopping. Goodbye, telling instead of showing. Goodbye, random, episodic storyline. This is a moment of much excitement–a whole new horizon opens before you. But it’s also a little scary, as you realize how much you don’t know about writing.

Then commences the Second Act of your writing life, a long period of reaction and struggle and, yes, conflict. There are pinch points along the way, as you realize how hard writing can be when you have to try to measure up to millennia of literary knowledge and evolution. You’re steadily improving as a writer, but this is also where you’re probably writing some of your worst stuff.

And then.

And then comes the Midpoint–the Moment of Truth–when you encounter what is arguably the most important revelation in your story. This is where you learn about story theory.

For me, my introduction to story theory arrived on the day when I first learned about story structure. Light bulbs flashed. Angels sang. There was no going back.

What Is Story Theory?

“Story theory.” It’s a term that might make make your eyes glaze over–redolent as it is with the the misty concepts of philosophy and experimentation. But, then again, if you’re like me, it might just make your eyes light up like the 4th of July.

I’ll play doctor for a second and say that if you’re eyes are glazing right now, then it might just be because you’ve yet to reach that Midpoint Moment of Truth where it all becomes clear.

I did a little bit of googling to prepare for this post, only to discover something interesting. There really isn’t much info out there on the subject of story theory. (Google the phrase and what you get is all Dramatica, all the time. Exclude Dramatica from the search results and what you get is mostly fan “theories” about Disney movies.)

To define story theory, let’s paraphrase Wikipedia’s presentation of music theory:

Story theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of story. It is derived from observation of, and involves hypothetical speculation about how writers make stories.

In other words, story theory is all about analyzing the existing body of literature to find its patterns and rhythms. What makes it work consistently? Naturally, a lot of these theorized patterns come down to plot structure. There are many different systems that all teach variations on basically the same universal approach to storytelling. We have such approaches as:

In other words, story theory is all about analyzing the existing body of literature to find its patterns and rhythms. What makes it work consistently? Naturally, a lot of these theorized patterns come down to plot structure. There are many different systems that all teach variations on basically the same universal approach to storytelling. We have such approaches as:

Aristotle’s Three Acts

Dramatica

Hero’s Journey/Monomyth

All are different approaches the same journey of story–rising and falling action–and all are worth studying, since they all bring their own insights to the table. (What I teach is primarily the Three Act approach, with a lot of Dramatica and a little of the Hero’s Journey thrown in.)

Think of story theory as the heart of storytelling. Although theory has connections to just about every actionable part of writing, it is primarily concerned with the nature of story itself, rather than the finer mechanics (such as grammar, the do’s and don’ts of POV, and dialogue).

Why You Should Hang Onto Story Theory Like a Drowning Sailor to a Lifesaver

Do you have to learn about story theory in order to be a good writer? No, not officially. But think of it like this: story theory is creative instinct actualized. It’s talent transformed into skill. Following are 7 vital reasons every author should be chasing story theory like a kid after a kite.

1. Story Theory Helps You Organize and Understand Your Writing

Here’s a possibly provocative statement: organizing your writing and understanding it go hand in hand.

Writers find themselves in vastly mixed camps these days when it comes to the idea of organization–aka plotting–aka outlining. Many writers contend that over-organization kills the creative spark.

An understanding of story theory does not impede creativity: it accelerates it.

But here’s an interesting trend I’ve been noticing. Every time I run upon an article or a post written for pantsers (those writers who prefer to “write by the seat of their pants” rather than outline their stories), it always ends up being a not-so-subtly-disguised means of seducing the pantsers over to the Dark Side of outlining and organization.

Why?

Easy. Because, ultimately, almost all the problems pantsers struggle with come down to a lack of organization and therefore a lack of understanding about the nature of story in general and their own stories in particular.

Story theory can help with that. Since theorizing is all about learning to understand something, it’s also inevitably about learning to organize the nature of storytelling. This doesn’t mean pantsers still can’t pants (the ability to pants is as important to all writers as is the ability to plot). But it does mean that an understanding of how story works–everything from structure to character arcs to theme–will show you how to understand your own stories’ needs, and to plan them accordingly.

2. Story Theory Eliminates Writer Confusion by Revealing Applicable Patterns

Raise your hand if you’ve ever found plotting overwhelming.

For all that stories are frequently reduced to the old fairy-tale formula of Once Upon a Time/Happily Ever After, they are absolutely, convincingly, 100% not simple.

Just the opposite. Stories are tremendously vast, complex, sprawling beasts. Indeed, as reflections of life, they are just as vast, complex, and sprawling as life itself.

In short, they’re complicated. Creating a seamless, perfectly resonant story can sometimes feel like looking at a tabletop scattered with puzzle pieces and being expected to immediately know exactly where every piece fits. No wonder we end up juggling pieces and dropping them all over the floor half the time.

Sometimes trying to understand a story is like trying to see where every puzzle pieces belongs all at once.

But story theory helps with that too. Story theory is all about identifying the universal patterns that exist in storytelling, across the globe and throughout the ages. The better you understand these patterns, the more clearly you can see where the pieces fit in your own stories.

You learn story theory by studying other stories–books and movies. You learn to identify the patterns–what works, what doesn’t, what makes you feel and react in a certain way. You begin to be able to break down the patterns in other people’s stories so you can better understand and study them.

3. Story Theory Helps You Identify and Avoid Mistakes

So many of the frustrations of the writing life come down to the instinctive knowledge that something is wrong with your story–only you don’t know what. How many times have you ripped apart a broken story and put it back together again, only to realize it’s still not right?

Without an understanding of story theory, you end up ripping apart your manuscripts and putting them back together, time and again, without understanding how to actually fix their problems.

A writer’s instincts are incredibly powerful. Indeed, the truths of story theory are already deeply ingrained within the human psyche. But instinctive knowledge can only take you so far. Your untrained conscious brain will get in your way. It will make you doubt the wrong things and believe in other wrong things.

After all, how can you ever know you’re doing something wrong if you don’t know how to do it right? Story theory teaches you what is right and why it is right. It allows you to harmonize your powerful storytelling instincts with story knowledge upon which you can act confidently and purposefully. It harmonizes your creative instinct with applicable skills.

4. Story Theory Shows You How to Mimic the Masters

We’re all trying to write the perfect story. The previous generation of writers didn’t get it right, so we try to learn from them–both their mistakes and their successes–just as the next generation will try to learn from us. Story theory is firmly grounded in the actuality of story itself. You can’t study story theory without studying stories.

The single best way to learn story theory is to read books and watch movies.

But it’s also true you won’t learn much from the masters who have gone before if you aren’t able to understand what it is they’ve actually done. As Jeff Somers said in the May/June 2016 Writer’s Digest article “Plantsing: The Art of Plotting and Pantsing”:

It’s tough to replicate a trick you didn’t understand in the first place.

An exploration of story theory will teach you how to get the most out of every story you encounter–good or bad, written or visual, your favorite genre or not. Every story ever written feeds into the overall study of story theory. It first teaches you about theory, and then allows you to use that theory to analyze what you’re experiencing. In his article “10 Reasons to Study Music Theory and Aural Skills,” David Werfelmann makes a comment that is as pertinent to writers as musicians:

Music theory is nothing more than a codification of the works that are the most meaningful to us. If we neglect to show why the rules and procedures are so important–that is, how they produce effective works of art–we miss the point of theory entirely.

5. Story Theory Takes You From Storyteller to Storymaster

Anyone can tell a story. But very few people are masters of storytelling. What’s the difference?

You know it: story theory.

If you want to take your writing to the next level–if you want to write more than forgettable potboilers–if you want your stories to matter–then you’ll need story theory to get there.

And there’s a bonus: the better you understand story theory, the easier your writing gets. You have more control over what you’re doing. No more flailing in the dark, wondering how to fix your story. You know how to fix it. (Even better, you’ll have far fewer problems to correct in the first place, since your understanding of story will have accurately guided your decisions all the way through the outline and first draft.)

You lose nothing in creative energy. Instead, you learn to harness that energy in the most effective and powerful ways.

6. Story Theory Is Awesomesauce!

Okay, this is really a bonus reason. But it’s big! Story theory is a.maz.ing.

Seriously, it’s totally addictive. The deeper I get into story theory, the more it enhances not just my writing, but also my enjoyment of stories in general, and even my own understanding and approach to life.

Story theory can sometimes sound like homework when you’re first getting your brain around the idea. But it’s not. This is what algebra is to Will Hunting, what physics were to Albert Einstein, what gorillas are to Jane Goodall. For writers, this is the stuff of life. It will suck you in, pull you under, and never let you go. And you’ll love every second of it.

7. TL;DR: Story Theory Will Teach You Everything You Need to Know About Writing

Let me sum all this up: story theory is storytelling. It is all of writing in a nutshell. It is everything I teach on this blog. Story theory shows you how stories work and how you can apply those lessons to your own writing. In short, whether or not you’re consciously chasing after story theory yet, you’ve already been immersed in it up to eyeballs all this time.

Story theory is a concept as big as the world itself. The more your knowledge and understanding of the theory grows, so does the theory itself grow. It’s a never-ending playground for writers–a never-ending opportunity to become a better writer every single day. You need story theory. ‘Nuff said.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How important is it for writers to study story theory? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/7-reasons-you-need-story-theory.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 7 Reasons You Need Story Theory appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 8, 2016

How to Transform Your Story With a Moment of Truth

Part 4 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 4 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

“How can I fix the saggy middle of my story?”

I love it when writers ask me that.

Why? Because the answer is so incredibly juicy–and it all revolves around the Moment of Truth that needs to occur at every story’s Midpoint.

The Second Act—that longest of all the acts, spanning a full 50% from the 25% to the 75% marks—is largely misunderstood. The setup of the First Act and the Climax of the Third Act are pretty self-explanatory. But what’s supposed to happen in between? How can you come up with enough story to entertainingly fill up such a huge chunk of the book?

The short answer is: structure.

There are more important structural moments in the Second Act than anywhere else in the story. If you’re aware of how to use the First Plot Point, First Pinch Point, Midpoint, Second Pinch Point, and Third Plot Point, you’ll never lack for forward impetus in your story’s hard-working Second Act.

Today, we’re going to take a look at what is, arguably, the most important of these structural turning points—the Midpoint and its Moment of Truth. (Click here for more info on structure in general, here for more info on the Second Act in general, and here for more info on the pinch points.)

The #1 Reason Thor Works Despite Its Problems

Welcome to Part 4 of our ongoing series exploring what Marvel has done right (and sometimes wrong) in their cinematic universe. I debated whether or not to focus Thor‘s post on a “do” or a “don’t” of storytelling.

This is far from a perfect movie.

The pacing is wonky: sometimes rushed, sometimes lagging.

The antagonist—the ever-charismatic Loki—is relatively absent from the protagonist’s main conflict for most of the story, and he fails to provide solid pinch points.

The parallel worlds of Asgard and Earth are never balanced well in the presentation of scenes.

In a lot of ways, it feels like a “small” movie, despite its obviously epic and interstellar stakes. Some people complained that the romance between Thor and scientist Jane Foster was given too much emphasis. Personally, I loved Natalie Portman in this role and thought she was a highlight of the entire movie—but I don’t disagree because, ultimately, the greatest problem with both this movie and its sequel Dark World is that it has a muddy thematic focus. What these movies are really about is family, and Jane, however adorable she may be, keeps getting in the way of that.

In short, we’d have to objectively say the script and its execution are pretty choppy. And yet I still really like this movie. For one thing, it was the movie where the whole cinematic vision of the Avengers throughline really gelled for me and started getting exciting. I thought the Earthside humor was charming. And, of course, it gets full credit for introducing the single most loved and interesting villain in the entire series.

However, at the end of the day, the reason I like this movie—and the reason I decided to focus on its good qualities instead of its weaknesses—is because I love its heart. I love its character arc (however rushed). I love the transformation of the protagonist from arrogant, self-centered war-monger to humbled, self-sacrificing, crown-worthy hero.

And most of all I love the Moment of Truth at the story’s center.

What Is the Moment of Truth?

The Midpoint is your story’s second major plot point. It occurs, as its name suggests, smack in the middle of the story. It divides both the Second Act and the entire book into two distinct halves. The first half of the book is all about the character’s reaction to the conflict; the second half is all about his ability to take action in light of a revelation he experienced.

That revelation is the single most important job of your story’s Midpoint. It is the Moment of Truth, and it is comprised of two different layers—one pertaining to the plot and the other pertaining to the character arc.

Layer #1: The Plot Revelation

Within the exterior conflict of your story’s plot, your protagonist is going to reach a game-changing revelation at the Midpoint. This revelation pertains directly to his exterior conflict with the antagonist. He desires a goal, and the antagonist has been throwing up obstacle after obstacle throughout the first half of the story. The antagonist has been squarely in control of the conflict, and the protagonist has had little choice but to remain in a reactive role.

Now, thanks to this Midpoint revelation, the protagonist suddenly sees the nature of the conflict much more clearly. He learns the true nature of both the conflict and the antagonistic force. He gains important info that will allow him to finally start taking control of the external conflict—thus allowing him to phase out of reaction and into action in the second half of the story. (Captain America: The Winter Soldier offers a great plot-based Moment of Truth, which I talked about in this article.)

Layer #2: The Character Revelation

Even as your character has been navigating the story’s external conflict throughout the first half of the story, his internal conflict has been closely mirroring, affecting, and being affected by the external plot. When he reaches the plot-centric Moment of Truth at the Midpoint (which grants him important new information about the nature of the external conflict), he also reaches an all-important personal Moment of Truth.

Remember, character arcs are founded on the protagonist’s inner battle between the story’s Lie and Truth. Throughout the first half of the story, he has been learning to see, more and more clearly, the nature of his Lie and that, indeed, it is a Lie.

The Midpoint is where he finally sees the Truth. He still has a long way to go until he’ll be able to fully claim that Truth by surrendering to it and acting upon it. But the Midpoint is where something happens to him that’s so dramatic, it prompts a shift in his personal allegiance—away from the Lie and toward the Truth.

How a Good Moment of Truth Transforms Your Story

Some stories will require a different Moment of Truth for both aspects of the Midpoint mentioned above. Often, one aspect’s revelation will lead right into the other. Other stories, however, will be able to harmonize plot and character into a single Moment of Truth.

Thor is such a story.

Thor’s Lie is that he is a worthy leader simply by right of birth and personal power.

His story is that of growing into an awareness that true worthiness is instead based on personal merit—humility, foresight, love, and self-sacrifice. Worthiness is something that must be earned. Despite getting boxed around by his Lie (in essence, “punished” for believing in it) throughout the first half of the story, he does not come face to face with that Truth until the Midpoint.

After using his old Lie-based methods to batter his way through SHIELD’s defenses on his way to reclaim his hammer Mjolnir and his Asgardian powers, he discovers he can’t so much as much lift his own hammer. He doesn’t know his father enchanted the hammer so that only “Whosoever holds this hammer, if he be worthy, shall possess the power of Thor.”

Thor is not worthy. That realization changes everything. It rocks his world. It undermines everything he has believed about himself, about others, and indeed about the universe. It forces him to reconsider his old belief—the Lie—in exchange for a new paradigm. As Dr. Selvig tells him after rescuing him from SHIELD, “It’s not a bad thing finding out that you don’t have all the answers. You start asking the right questions.”

Boom. Moment of Truth. Right between da eyes.

3 Questions for Planning Your Story’s Moment of Truth

What should your story’s Moment of Truth be? The answer depends on three factors:

1. What’s Your Protagonist’s Truth?

Can’t have a Moment of Truth without first knowing what that Truth is, right?

Naturally, the Moment of Truth cannot live in isolation. It is a product of everything that has come before it in the first half of the story, just as it is the catalyst for everything to follow. You can’t just shoehorn in any ol’ Truth. It has to be the Truth your protagonist requires in order to overcome the Lie he’s been carrying around since Page 1.

So take a look at Page 1. What’s the Lie Your Character Believes? What Truth will he need to overcome that Lie?

2. What Is the Key to Overcoming the Antagonist?

Now consider the plot. What is the one bit of information the protagonist requires in order to transform his understanding of the external conflict and allow him to shift from reacting to the antagonist into taking action?

(Note that Thor’s external conflict is not defeating Loki, but rather returning home. In reaching his Moment of Truth he becomes worthy of the hammer—and thus his ride back to Asgard—even though he doesn’t yet realize it.)

Ideally, both the plot and character revelations should be the same or at least lead organically one into the other. If they’re too disparate from one another, then you need to consider whether or not your plot and theme may be too different from one another to belong in the same story.

3. What Is the Best Visual Representation of Plot and Theme?

Once you understand the Truths your character will come to understand at your Midpoint, you must then create a scene to represent them. Your Midpoint will usually be one of your story’s biggest scenes (in Thor, the fight in SHIELD’s compound is one of the the biggest action setpieces in the movie).

Even though the Moment of Truth will probably be a quiet moment of personal introspection, it should be featured within a huge plot catalyst—one that visually and symbolically represents the Lie and the Truth.

James Scott Bell talks about a “mirror moment,” in which the character must metaphorically look at his own reflection and confront what he sees. In some stories, you can portray this outright, either by having the character literally look at himself in a mirror (e.g., Thor sees his battered appearance in a reflective door after he’s imprisoned by SHIELD), or by providing some other visual reflection of his inner battle (e.g., in Iron Man II, a drunken Tony who is using his suit for dangerous party tricks is confronted by his best friend Rhodey, also in a suit, telling him he’s a disgrace).

Note: this visualization of the “mirror moment” isn’t a must; don’t shoehorn it in. But it can present a nice symbolism if handled well.

Once you understand your story’s Moment of Truth at the Midpoint, you already have your single most powerful tool for crafting, not just an interesting Second Act, but a powerful and resonant character arc, story structure, and theme. Think you’re worthy?

Stay Tuned: Next week, we’ll talk about one of my all-time favorite examples of subtext-rich dialogue from Captain America: The First Avenger.

Previous Posts in This Series:

Iron Man: Grab Readers With a Multi-Faceted Characteristic Moment

The Incredible Hulk: How (Not) to Write Satisfying Action Scenes

Iron Man II: Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What’s your protagonist’s Moment of Truth at the Midpoint? Tell me in the comments!

The post How to Transform Your Story With a Moment of Truth appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 6, 2016

4 Ways to Choose the Right Story Setting

Most writers don’t have too much trouble when it comes to how to choose the right story setting for their books. Middle Earth; Maycomb, Alabama; Hogwarts—it’s often fairly obvious which locations will serve the needs of the story; then it’s just as matter of picking the best one.

But what about the rest of the settings? A small-town high school might be the sensible choice for your YA novel, but you can’t set every scene in the fine arts hallway. What about when your character is at work, on a date, or hanging out with friends? How does she get to and from school? What kind of home does she live in and what does her personal space look like?

While most authors understand how to choose the right story setting for the overall book, they don’t typically put as much thought into the locations for the individual scenes. Yet these decisions are just as important. The setting choices at this level have the power to make or break the story—to simply set the stage or to bring the scene to life by making it meaningful and drawing readers into it.

If you’re hoping to accomplish the latter, consider the following questions when selecting settings at the scene level.

1. What Is the Purpose of This Setting?

Most writers think of the setting as merely the tool that enables us to establish the time and place for readers. But settings can—and should—do so much more. Through the setting, you can also

Hint at or reveal backstory

Establish mood

Symbolize

Characterize

Foreshadow

Reinforce emotion

Provide tension and conflict

If you know beforehand which of these things you’d like your setting to accomplish, you can choose a location that will suit your purpose and help you achieve that goal.

For instance, maybe it’s the beginning of your story and you want to set the stage while also including some much-needed characterization for the protagonist. Use a personal setting that will reveal truths about her:

Workspace

Car

Favorite room in her home

For a scene that’s meant to add conflict, consider locations that will cause her stress:

The site of a traumatic past event

A place that will trigger insecurities

A location where she’s likely to see someone she’d rather avoid

Always consider the purpose of the scene—what you can organically accomplish through the setting. Our Setting Checklist can help with this, enabling you to plan ahead what you’d like your setting to do in each scene so you can choose the best locations possible.

2. Which Setting Makes Sense for Your Character?

When choosing settings, it’s always important to keep your character in mind. One location might make sense for your story, but if it doesn’t fit with your character, it will fall flat.

For instance, maybe something important has just happened and it’s time for a reflection moment for your protagonist; you need a place where he can process what has happened and prepare himself for the next step. The first place that comes to mind might be a dock by the lake or a walk through the woods. These are great choices for someone who appreciates nature and needs peace and quiet in order to properly reflect.

But what if your character is an urbanite who hates bugs or an extrovert who doesn’t like to be alone? For the former, a solitary ride on the city bus or train might enable him to work through his thoughts. An extrovert’s best reflection time might occur while walking a crowded street or partying with friends at a club.

There are so many setting possibilities for each scene; many of them can feasibly work, but only if they make sense for your character.

3. Which Settings Have an Emotional Pull for Your Character?

Most of the time, identifying your setting’s purpose and making sure it fits for your character will be enough for the location to work for your scene. But some parts of the story need a little more care: highly emotional scenes, scenes that reveal important information, ones that mark a turning point for either your protagonist or the story—these important events can be made more meaningful when they’re set in a place that triggers past memories or impacts the character’s emotions.

In John Grisham’s The Firm, Mitch McDeere learns his house is bugged and his employers have been spying on his family. Now he has to reveal this disturbing information to his wife. Instead of Mitch taking her out to dinner or for a walk, Grisham sets this scene in the one place that makes this news even more impactful: in their house, the site of their violation.

This is their home, their safe place, the one place in the world where they should be able to be themselves. Setting this revelatory scene in their home adds an emotional punch (and an element of danger) that would have been missing had it taken place elsewhere.

When you’re considering locations for an important scene, brainstorm possibilities with your character in mind. What locations are emotionally loaded in some way for him? Which ones elicit strong positive or negative feelings? Are there any that would provide an emotional contrast to what’s happening in the scene? The answers to these questions can help you come up with the perfect settings for the important events in your story.

Have You Thought Far Enough Outside of the Box?

As with any area of writing, it’s tempting to go with the first idea that comes to mind. In doing so, we often settle for good when, with a little more thought, we could unearth something amazing that could take a scene to the next level. For this reason, when choosing a setting, it’s always good to think past our initial ideas.

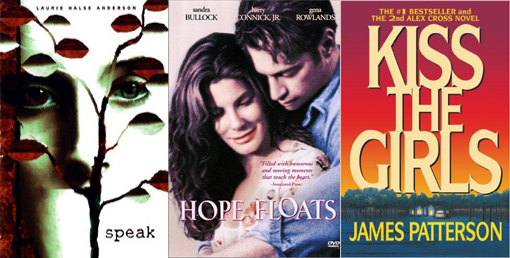

Melinda, the lead character in Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak, finds peace and solace in a janitorial closet at her school. Hope Floats’ Birdee Pruitt is dumped by her husband on a live talk show. In Kiss the Girls, the protagonist is kidnapped and held captive in the ruins of an abandoned plantation—creepy and symbolic.

All of these settings are a bit out of the ordinary. There are many locations where each event could have taken place, but these locales add a little something to each scene while still supporting both the story and the character.

So as you’re choosing settings for the scenes within your story, keep all of this in mind. Know your setting’s purpose. Know your protagonist and what makes sense for him. When it’s appropriate, choose a setting that has significant emotional impact for your character. And always think past your first impulse to see what interesting secondary possibilities arise. If you can consider these questions during the planning process, you’re sure to come up with an intriguing array of settings that will add that extra bit of oomph to each scene and to your story as a whole.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What is your top consideration in figuring out how to choose the right story setting? Tell me in the comments!

The post 4 Ways to Choose the Right Story Setting appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 4, 2016

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 52: Stagnant Story Conflict

What’s so hard about story conflict? You throw your protagonist and your antagonist onto the page–insta-conflict! Right? Actually, not so fast. Turns out creating a fascinating story world in which dwells a fascinating hero and an evil villain is not enough, in itself, to create integral and interesting story conflict.

What’s so hard about story conflict? You throw your protagonist and your antagonist onto the page–insta-conflict! Right? Actually, not so fast. Turns out creating a fascinating story world in which dwells a fascinating hero and an evil villain is not enough, in itself, to create integral and interesting story conflict.

I’ve read quite a few unfortunate stories in which the protagonist spent the majority of the book pacing around his base thinking about that dirty antagonist and all his dirty deeds. The protag shakes his fist at the sky, curses the antag, and promises to make him pay. Then he resumes pacing. Finally, the Climax rolls around, the protag and antag meet, they fight, the protag wins.

Of course, the author is lucky if I’ve actually stuck around long enough to read his fascinating Climax, since all that pacing on the protagonist’s part slipped me the Mickey chapters and chapters ago.

The dangerous part of all this is that it’s super easy for authors to fall into this mistake without even realizing it. But never fear! There is an easy precautionary measure you can take to make sure your conflict is alive and well throughout your entire story.

Do You Understand the True Nature of Story Conflict?

Where many authors go wrong with their conflict is simply in failing to understand what story conflict really is.

Is story conflict…

A protagonist and an antagonist on opposite sides of a war?

Two characters arguing?

Two characters duking it out?

Two characters nuking it out?

An evil antagonist making your protagonist’s life miserable?

An evil antagonist giving your protagonist an opportunity to look awesome?

Good stomping all over evil on its way to ultimate triumph?

Short answer: no.

All of these are often manifested aspects of story conflict. But they are not, in themselves, conflict.

What this means, of course, is that you can create all of the above in your story and still not have a story. Without organic conflict, the above elements will only ever be flimsy window dressing.

Powerful Story Conflict in 2 Steps

Conflict-as-plot is about much more than simply characters who nominally oppose one another. Fundamentally, conflict is about two things:

1. Goal.

2. Obstacle.

Your protagonist and your antagonist each want something, and they’re each getting in each other’s way. As a result, they must each keep readjusting their tactics in an attempt to outmaneuver the other. (Find how more about how the antagonist’s goal powers the conflict in this recent post.)

This is what drives your story conflict on the macro level of your entire plot, and it does that by, first, powering your story in a seamless line of cause and effect throughout every single scene. Remember scene structure?

Proper scene structure looks like this:

Scene (Action)

1. Goal (Character wants a smaller something that will help him gain his overall story goal.)

2. Conflict (Obstacle prevents character from gaining his goal.)

3. Disaster (The obstruction leads to a whole new set of problems.)

Sequel (Reaction)

1. Reaction (Character must reflect on his new setback.)

2. Dilemma (Character must face the new set of problems created by the disaster.)

3. Decision (Character comes up with a plan for a new scene goal to help him gain his overall story goal.)

When all your scenes are focused on a specific mini-goal designed to help your character gain his overall story goal–and that goal is then met with a specific obstacle related to or empowered by the antagonist in some way–then your story conflict will never stagnate. It will be organic and powerful. Your characters will never need to spend their time pacing the room and thinking about the conflict, because they will always be driving it forward.

How to Write Your Story Conflict That Isn’t Really Conflict

Here’s the problem. Too many authors write story conflict that isn’t conflict so much as a delaying tactic to fill up their books until they can actually get around to the Climax. The characters have to do something, right? And if they meet up with the antagonist too soon–and defeat him–well, then, the story is over right then and there, isn’t it?

So what can you do to fill all those intervening chapters? Maybe something like this…

Brunhilde walked down the hall at Ft. Nibelung, headed for her third briefing of the day.

The elevator pinged, and Colonel Wagner stepped out and hailed her. “Terrible about what Admiral Walkure is cooking up out there in the Rheingold Wastes, isn’t it?”

Brunhilde clutched her files closer to her chest. “Terrible. And to think he was my step-father.”

“What did you learn in this morning’s meeting?”

“The hover-carriers are getting closer every day.”

“What does General Sieglinde want us to do about it?”

“Just wait for now. What else can we do?”

The colonel’s face tightened. “True. But war is coming, make no doubt.”

Sounds kinda tense, right? It’s true there’s nothing inherently wrong with this scene–as long as Brunhilde and the colonel enter that briefing room and receive orders to immediately charge out there to sabotage the admiral’s fearsome hover-carrier by midnight tonight.

But what if the briefing drones on, telling readers more about the evil admiral and his evil plans? What if, after the briefing, Bundhilde heads off to the lunch room, where she and her aide Siegfried pull long faces and mourn the news of the admiral’s atrocities? What if they then head down to the training room to hone their already long-honed skills so they’ll be ready when the admiral finally attacks?

Bored yet? I’m bored just writing that severely condensed paragraph. There’s no story conflict there. There’s just characters talking about the potential for conflict.

Whatever that is, it ain’t plot.

How to Electrify Readers With Powerful Story Conflict

Now picture this. What if, instead of rambling around Ft. Nibelung, mulling on the awfulness of having an evil admiral for a stepfather, Brunhilde, Colonel Wagner, and Siegfried get their acts together and decide on a plan of action?

If ending the war is their main story goal, then every single scene goal should be related to that goal in some way. What can Brunhilde want in this scene that will be the first step toward defeating the admiral and accomplishing her story goal? What obstacle will prevent her from easily or entirely gaining that goal? What new goal will that inspire? Every scene should lead her–hard-fought step by hard-fought step–closer to her ultimate goal of taking down Step-Daddy.

Consider:

Brunhilde stalked down the hall at Ft. Nibelung, headed for her third briefing of the day.

The elevator pinged, and Colonel Wagner stepped out and hailed her. “Terrible about what Admiral Walkure is cooking up out there in the Rheingold Wastes, isn’t it?”

Brunhilde clutched her files closer to her chest. “Nobody’s doing anything about it. If I didn’t know better, I’d say our good General Sieglinde is taking orders from the admiral.”

The colonel grabbed her arm and stopped her. “What did you learn in this morning’s meeting?”

“The hover-carriers are getting closer every day.”

“What does the general want us to do about it?”

“Just wait for now. What else can we do?”

The colonel’s face tightened. “What if I told you I’m looking for volunteers for a top-secret mission?”

An emotion somewhere between fear and hope sprang up in Brunhilde’s chest. “Well, sir–then I’d tell you, you just found your first volunteer.”

Can you spot the single greatest difference between the two versions of this scene?

This is it in a nutshell: the second example moves the plot. The characters are in a totally different place at the end of the scene than they were at the beginning. Contrast that to the first example. What changed there? Say it with me: nada.

4 Questions to Refine Your Story Conflict

Here’s a challenge for you: go through your latest story, scene by scene and ask yourself the following questions.

1. Can you identify your character’s scene-specific goal in each scene?

2. Does that goal tie into the overall story goal?

3. Is that goal met by conflict that will inspire a new goal in the next scene?

4. Does the nature your story change in each scene?

If you find a scene in which the characters and the conflict are both in essentially the same place at the end as they were at the beginning, then it’s a pretty sure bet you’re looking at some stagnant story conflict. Root it out ruthlessly by creating dynamic conflict–and readers will stay glued to the page.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How does the story conflict in your latest scene change the story? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/mistakes-52.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 52: Stagnant Story Conflict appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 1, 2016

Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist

Part 3 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 3 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Stop thinking of your minor characters as characters.

If that flies in the face of everything you’ve ever heard about your story’s supporting cast, then just hang with me for a minute as I first ask you this all-important question:

What is story?

On its surface, story is a mimicry of real life following the journey of one character in particular (the protagonist) as he interacts with a bunch of other characters–just like we interact with all kinds of random and not-so-random people in real life.

But if we dig straight down to the beating heart of story theory, we discover that story is actually more about positing and proving (or disproving) theme than it is anything else. This is true of any type of story, no matter how banal or high-brow, whether the author realizes it or not.

As such, you then have to look past the surface role of all the playing pieces on your story’s board. Your minor characters are no longer just characters; they’re no longer just representations of people (although, of course, you have to keep that aspect in play as well). So what are they?

Get ready–this is where it gets awesome.

Your minor characters are reflections of your protagonist.

Deep down, on the deepest of story levels, the minor characters are there to provide thematic representations of your protagonist’s various fates.

Is Iron Man II a Character Movie?

Welcome to Part 3 of our exploration of the Marvel cinematic universe’s highs and lows of storytelling. Today, we’re going to take a look at how Jon Favreau’s Iron Man II used its minor characters in this powerful way to reinforce the inner journey of protagonist Tony Stark.

In the wake of the blockbuster Iron Man and the flaccid Incredible Hulk, this highly anticipated sequel was received with lukewarm responses. At the time of its release, Marvel’s overarching vision of interwoven movies still wasn’t completely clear, and this movie definitely suffers as a standalone. In hindsight, however, I find it works better, and is, indeed, an integral piece in the overall storytelling–a sort of Avengers 0.5, setting up the true evolution of the series in the following movies.

It’s also an excellent character study, as we get to see mightily flawed would-be hero Tony Stark struggling with the ramifications of everything that happened to him in the past six months–including being captured by terrorists, changing the focus of his multi-billion-dollar company, becoming Iron Man, and just generally trying to figure out what it really means to stop wasting his life.

Oh, yeah, and he’s also dying.

In short, he’s having a bit of an existential crisis, all against the backdrop of pressure from the government and assault by rogue terrorist Ivan Vanko, who has a personal grudge against Tony and his father.

It’s a busy movie, and one of the chief complaints is that it didn’t develop its exterior conflict with Vanko well enough. Everybody blames Marvel’s insistence of shoehorning in Nick Fury, SHIELD, and Black Widow as setup for The Avengers. But the reality is that this movie is, in fact, a character movie. The external conflict isn’t the point.

The point is Tony’s relationship with the minor characters–and how they flesh out his personal, inner journey. Let’s take a look at how this movie uses its minor characters to create a unified theme–and how you can do the same in your books.

How to Use Your Minor Characters to Create a Rock-Solid Thematic Premise

If character arc and theme are all about the conflict between a posited Lie and Truth, then everything in the story will need to reflect upon that thematic premise in some way. Same goes for the minor characters.

The fabulous Matt Bird talks about:

…the concept of clones, characters in the hero’s life who represent possible outcomes, either as cautionary tales or as potential role models. I refer to such characters as parallel characters.

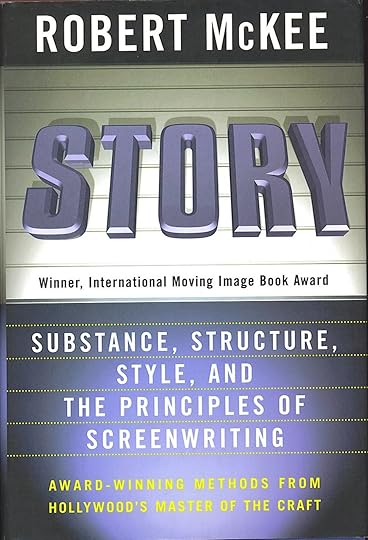

In Story, Robert McKee says it this way:

Consider this hypothetical protagonist: He’s amusing and optimistic, then morose and cynical; he’s compassionate, then cruel; fearless, then fearful. This four-dimensional role needs a cast around him to delineate his contradictions, characters toward whom he can act and react in different ways at different times and places. These supporting characters must round him out so that his complexity is both consistent and credible.

6 Ways Minor Characters Can Deepen Your Protagonist

Now consider how Iron Man II uses its minor characters. Every single one is carefully chosen to reflect upon the protagonist or represent a future fate he may experience–depending on the thematic choices he makes in the story.

Ivan Vanko/Whiplash

The antagonist is always the most obvious representation of the protagonist. It is his similarities to the protagonist that both tempt the protagonist and warn him away from the Lie.

Vanko is an obvious example. He and Tony are very similar. Both are genius inventors. Both are the sons of genius inventors–both of whom were involved in creating the ARC reactor. Both are tortured by their pasts with their fathers. Both are intent on “putting things right.” Tony could end up as Vanko in the blink of the eye (and, indeed, arguably does by the time Civil War rolls around).

Justin Hammer

Here’s another antagonist, mirroring still more aspects of Tony’s life. Hammer is also an inventor (although not quite so genius), and, like Tony, he is the head of a major arms manufacturing company (although not quite so successful). He’s a wise guy (although not quite so fly as Tony), he’s a jerk (although never lovable like Tony), and a selfish wheeler and dealer (just like Tony).

Hammer is a representation primarily of who Tony used to be: a weapons dealer who had no care whatsoever for the moral ramifications of his actions. All he cared about was being the top dog whatever the cost and however much of a jerk he had to be to get there.

Natasha Romanov / Black Widow

Iron Man II introduces the perennially popular character of (sorta) repentant spy Natasha Romanov. She provides foreshadowing for the roles Tony will fill–as a reluctant member of SHIELD and the Avengers. Hers is primarily a surface reflection of outer roles, rather than a representation of the Lie/Truth.

Pepper Potts

Tony’s not-quite girlfriend, the ever-dependable Pepper Potts, reluctantly takes over Stark Industries, at Tony’s insistence–representing his status as head of the company and his erstwhile position as CEO. Note how by externalizing this particular role of Tony’s, the story is able to transform it into a much more active form of conflict. Now, Tony gets to argue with Pepper (representing the aspect of him that would be a “good” CEO), instead of simply internalizing information and making decisions.

Pepper is also, as Love Interest and a Mentor of sorts, a representation of the Truth. She is Tony’s complete opposite: thoughtful, responsible, dutiful, and kind. She represents the ideal the protagonist is capable of achieving if only he can come fully to grips with the Truth.

James Rhodes / War Machine

Tony’s rightfully indignant best friend Rhodey is a two-sided reflection. On the one hand, like Pepper, he represents the ideal toward which Tony is striving: a man who is responsible enough to be entrusted with the War Machine suit–without using it for drunken party tricks.

On the other hand, Rhodey also represents Tony’s potential fate if he ever completely surrenders his tech to the government. Rhodey’s suit is slaved by Hammer and Vanko, turning him into a mindless weapon that threatens even his friends.

Howard Stark

And, finally, we have Tony’s dad, Howard, who appears in flashbacks. Tony’s relationship with his brilliant father is complicated and full of wounds–but it is also perhaps the most important projection of Tony’s future evolution.

He is more similar to his father than to any other character: they’re both brilliant, conflicted playboys with poor relational skills. In hating his father, Tony is essentially hating himself. He cannot come to inner peace without first harmonizing this outer manifestation of his inner conflict.

Consider the minor characters in your story. How are they already reflections or representations of your protagonist’s various traits, roles, and potential fates? How can you strengthen their thematic relationship to your protagonist to create an even deeper and more powerful weave within your story?

Stay Tuned: Next week, we’ll talk about how the one thing the wobbly Thor undeniably aces is its Moment of Truth.

Previous Posts in This Series:

Iron Man: Grab Readers With a Multi-Faceted Characteristic Moment

The Incredible Hulk: How (Not) to Write Satisfying Action Scenes

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How are you using your minor characters to flesh out your protagonist? Tell me in the comments!

The post Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 27, 2016

5 Secrets of Complex Supporting Characters

Supporting characters don’t get nearly enough love.

Supporting characters don’t get nearly enough love.

We come up with amazing protagonists who do amazing things and we labor to give them solid and complicated character arcs. But after all that work on the story’s forerunner, what happens to the supporting characters?

Too often, they’re an afterthought.

Of course, your protagonist needs a dad or a best friend or a little old neighbor lady, so you stick them into the story. You can see them already, right? But the sad part is many writers get no farther than that in planning these incredibly important characters.

Even the best of protagonists can’t carry your entire story. You need a cast of supporting characters who are every bit as complex, rounded, and interesting in their own right. Not only do complex supporting characters create a more interesting and realistic world for your story, they’re also crucial ingredients in rounding out your protagonist. Robert McKee says in Story:

In essence, the protagonist creates the rest of the cast. All other characters are in a story first and foremost because of the relationship they strike to the protagonist and the way each helps to delineate the dimensions of the protagonist’s complex nature.

Does this mean you must create a complete character arc for every single minor character in your story?

Definitely not. Many of your supporting characters will have comparatively tiny roles–perhaps only appearing for a few scenes. Fleshing out a entire character arc for all of them would land somewhere between that’s crazy and that will make you crazy. Suffice it that it’s overkill.

All you need to create complex supporting characters–no matter how large or small their roles within the story–is to answer five important questions about each of your minor characters.

1. What Does This Supporting Character Want?

If you’re only going to ask one question, this is the one. If you’re Dr. Frankenstein, and your characters are your little monsters, then this question is the vivifying electricity that brings every single one of them to life–from your protagonist right on down to the walking-est of walk-ons.

Take a look at your cast of supporting characters. I’ll bet you a lot of juice you’re going to find one of two things:

1. They really don’t want much of anything.

2. If they do want something, then that desire is either:

a. Help protagonist get what he wants.

b. Stop protagonist from getting what he wants.

Believe me, people, we can do better than this. I asked myself these questions about my supporting characters, as a new outlining exercise, while working on the sequel to my portal fantasy Dreamlander. I was a little startled to realize the desires of most of the minor characters in the first book fit neatly into one of those two narrow categories up there.

So what did I do? I started going through my supporting cast, name by name, and coming up with a specific desire for each of them in the new book.

The result?

Every single character–the protagonist’s relationship with them–the main conflict–the entire plot–they all instantaneously bounced into a new dimension. Boosh. Mind blown.

Try it. I guarantee your minor characters will go from inconsequential smiling heads to full-on plot catalysts and genuinely interesting humans.

2. What Is Your Supporting Character’s Goal?

It’s not enough for your supporting characters to sit around wanting something. They need a plan of action for how they’re going to obtain their goal.

This is where things get fun. Because, just as with your protagonist’s goal in the main conflict, your minor characters need to discover that the course of good storytelling never did run smooth. They’re going to have a really hard time getting what they want. They’re going to meet serious resistance. Conflict, baby, conflict.

Want it to get even better? The majority of that resistance should be the result of other character’s goals–particularly the protagonist’s–getting in the way of the supporting character. And vice versa.

Let’s say your protagonist is a spaceship pilot whose goal is to go off and save the galaxy. Now let’s say he has a mother who loves him and who desperately wants to keep him from harm’s way. Her goal is to stop him any way she can, even if it means lying to recruitment officers–or maybe even breaking her son’s hand in the door to “protect” him.

Talk about conflicting goals.

3. What Lie Does Your Supporting Character Believe?

Just like your protagonist, your supporting characters are going to be less-than-perfect people. Their motivations for their desires and goals will be driven by their own complicated and often detrimental perspectives on life.

The fundamental heart of every character arc–however complete or cursory–is the Lie the Character Believes. This is what creates the underlying personal motivation and justification for everything the character desires and does.

Let’s return to our overprotective mother from the previous example: her Lie might be that she failed to protect her older son, who has already died in the war, and so she must do anything short of murder to stop this second son from also dying a hero’s death.

Or it could be something much smaller and less injurious. In Charles Dickens’s Little Dorrit, the protagonist’s older sister and brother believe they must “do the family credit” by acting high and mighty, in order to somehow make up for the fact that their father has been in debtor’s prison for twenty years. This creates a wonderful undercurrent of conflict with the protagonist, Amy, since she both recognizes the folly of this approach and rejects it as ignoble.

The Lie marks the “starting place” for your supporting character. It’s the mark on the wall, showing how tall he is at the beginning of the story. At the story’s end, you’ll create another mark to contrast the first and show how far the character has advanced (or retreated) over the course of the story. Every prominent supporting character in your story should be different in some way at the end from who he is at the beginning.

4. What Flaw Results From Your Supporting Character’s Lie?