K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 51

February 6, 2017

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 56: Unfulfilled Foreshadowing

Sometimes writing feels like magic. You look back at the story you’ve created and it seems like it came from beyond you. One of the coolest examples of this is with foreshadowing.

Sometimes writing feels like magic. You look back at the story you’ve created and it seems like it came from beyond you. One of the coolest examples of this is with foreshadowing.

Some little something you wrote in the early chapters without even thinking about it ends up being a huge clue or bit of symbolism that foreshadows something major later on.

Talk about your subconscious rocking this joint!

But the flip side is that sometimes you’ll accidentally plant things that will seem important and portentous–only to have them end up as disappointing unfulfilled foreshadowing.

The problem with unfulfilled foreshadowing is simple: it’s a broken promise to your readers. Due to the way in which you’ve presented an event, or chosen your wording, or even just copped to a familiar genre trope, readers will have certain expectations about where the story is going.

Their expectations could be a blatant iteration in their conscious (“oh, I see a fistfight coming up”), or even just a niggle in the subconscious (which might not be thought about until the story’s over, but which will leave a sense of dissatisfaction with the loose ends).

What’s the result?

Best case scenario: Your book feels ever so slightly disjointed and incomplete, like that lumpy afghan Aunt Lou gave you when she was still learning to knit.

Worst case scenario: Readers will end up disgusted with the progression of the story because it went in a completely different direction from the one you told them it was headed—like maybe Aunt Lou started out knitting you an afghan, then decided halfway in that it should be a muumuu.

Either way, unfulfilled foreshadowing is not something you want lurking in your story (anymore than anyone wants a lumpy muumuu). Here’s how to spot it and lick it.

3 Different Types of Unfulfilled Foreshadowing

There are three basic types of foreshadowing you may find yourself accidentally creating as you’re writing your story.

1. Tonal Foreshadowing

One of the easiest ways to create subconscious foreshadowing is simply through your manipulation of the story’s tone. A skilled writer can turn even the most mundane passage into one dripping with portent and the undeniable sense that something is about to happen.

Consider the entire first half of Ridley Scott’s Alien, in which nothing much actually happens, but the tension and the tone is just about enough to strangle you.

Can you imagine the problems that would have resulted had the tone of tension and foreboding in Aliens ended up as unfulfilled foreshadowing?

Or how about this progressively creepy passage from Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, in which new governess Jane is being given an innocent tour of her employer’s grand mansion Thornfield Hall:

Mrs. Fairfax stayed behind a moment to fasten the trap-door; I, by drift of groping, found the outlet from the attic, and proceeded to descend the narrow garret staircase. I lingered in the long passage to which this led, separating the front and back rooms of the third story: narrow, low, and dim, with only one little window at the far end, and looking, with its two rows of small black doors all shut, like a corridor in some Bluebeard’s castle.

Even the slightest of clues, such as the mysterious red scarf in the upper window at Thornfield Hall, must be paid off in order to avoid being unfulfilled foreshadowing.

Sometimes tonal foreshadowing ends up being a wonderful thing. It can be the source of those “magic” bits of foreshadowing you didn’t even know you were sowing. But it only works when you end up paying it off. Scary music playing in the background is never cool if there’s not actually anything scary (or at least ironically unscary) about to pop up around the corner.

2. Blatant Hook Foreshadowing

Another type of foreshadowing you may plant but forget to pay off is a blatant hook. This is when you outright tell readers to be on the watch for a future development. This might happen via a character’s internal thought process in the narrative or via dialogue.

There’s a great example of this type of unfulfilled foreshadowing in Howard Hawks’s classic western Red River when Walter Brennan’s toothless sidekick character watches an impressive display of shooting skills from two young characters who are “pawing at each other, seeing what they’re up against.” At the end of the scene, Brennan pronounces, “Those two are going to tangle for sure.”

Even masters like director Howard Hawks get it wrong sometimes in creating dead-end scenes that lead to unfulfilled foreshadowing.

That’s about as blatant a foreshadowing hook as you’re likely to get—but it’s never paid off. The two characters become friends and allies and never tangle at all.

This type of unfulfilled foreshadowing is even more egregious than the first, since the more blatant you are, the more conscious readers will be of the discrepancy.

3. Important Event Foreshadowing

You will also create an impression of foreshadowing in readers’ minds by scripting “big” and important events within your story. When these events happen early on, readers will see the obvious importance and expect these events to matter later.

In order for the foreshadowing to be properly fulfilled, these events must have proper consequences later on. There must be cause and effect; there must be foreshadowing plant and payoff. Otherwise, the story will feel decidedly lopsided and readers’ expectations will go unsatisfied.

Think about the bank robbery at the beginning of Chuck Hogan’s The Town. The bank-robber protagonist ends up falling in love with the bank-teller witness who was briefly his hostage. Think how unsatisfying the payoff would have been had she never discovered his identity as the bank robber and had he never been forced to deal with the consequences of this major early event.

Big events must end up having equally big consequences. Otherwise, readers will experience the same effect as in all unfulfilled foreshadowing—and call foul.

5 Causes of Unfulfilled Foreshadowing

Now that you understand the three most common ways you can go wrong with unfulfilled foreshadowing, stop and think about some of the reasons you might accidentally be creating it in the first place. Here are five.

1. You’re Trying to Create Tension in the Story

This is probably the most common. There you are, up to your elbows in a scene. You may even have the whole thing plotted and know exactly where it’s going. But while in the midst of the actual wordplay, as you’re trying to delicately twine sentences to create the right amount of tension and interest for readers—you may end up sticking in a bit of false foreshadowing.

This can be as small and inconsequential as a single word choice. Sometimes just saying a character “looked grim” or had a “sinking feeling” can be enough to pump extra tension into a scene—and lead readers to the wrong conclusion, if it turns out there isn’t a good reason for all that sinking grimness.

What Should You Do Instead?

Nothing wrong with using your words skillfully to create tonal foreshadowing. Truly, it’s the stuff of great writing. Just be sure you’re always in a position to pay it off later in the narrative. Otherwise, you’ll either need to leave it out altogether, or maybe even reexamine why you feel this particular scene needs an extra bump in tension. Maybe you’d be better off taking your story in this tenser direction after all.

2. You Have to Give the Character Something to Do/Someone to Talk to

Sometimes you just have to feel your way through writing a scene. You don’t know how you’re going to reach the end of it until you do and in the meantime you’ve got to give the character something to do or someone to talk to. So far, so good. But sometimes these new additions can end up creating too many new complications.

What you originally intended as simply a casual, colorful chat between your protagonist and that Mafia hit man may end up seeming like much more to readers who will expect such a weighty character to show up covered in blood in the middle of the night at the protagonist’s door.

What Should You Do Instead?

Again, nothing wrong with introducing minor characters who have the ability to take the story in new and interesting directions—as long as that’s the direction you’re actually wanting to take. In a quiet romance, the village vicar might be a better choice for that casual conversation, especially if you can circle back and return him to the story at a meaningful point later on.

It’s also important to note that when you find yourself randomly adding interesting characters and scenarios to your story while “trying to figure out your scene,” what you might really be doing is clearing your throat. Be wary of adding interesting elements just for the sake of filling space and time, or even just because they’re interesting. Every part of a story needs to be there because it advances the plot, the character, the theme—or preferably all three.

3. You Want to Include the Gun, but Not the Bullets

The dramatic principle of “Chekhov’s gun” dictates you must:

Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.

But sometimes you may find yourself writing a gun into a scene just because you want the gun even though you don’t actually have a reason to fire it later.

For example, a scene in which a character drinks and then drives is foreshadowing just begging to be paid off with consequences (or at least irony) later on. As much as you may want the initial drinking scene, it will probably do your story more harm than good if you can’t bookend it appropriately later on.

What Should You Do Instead?

When you create a scene in which a character makes certain choices, readers will expect and desire consequences. Otherwise, however great the initial scene, it will fall flat. This means you must either ruthlessly pay off the foreshadowing with subsequent consequences, or cut the initial “gun” no matter how desirable it is in itself.

4. You Forget to Pay Off the Foreshadowing Later On

Inevitably, within the sprawling journey of writing an entire novel, you will fail to pay off early foreshadowing seeds simply because you forgot all about planting them in the first place. Usually, this is an easy fix. Just wield your red pen in revisions. You can either cancel the early foreshadowing or add an appropriate payoff toward the end.

Sometimes, however, you may find that removing the early foreshadowing plant or adding a payoff later on completely changes the story you ended up writing. This is always frustrating, since it means rewriting entire scenes or subplots.

What Should You Do Instead?

Whether the required revisions end up being large or small, they’re always worth making. You don’t want readers finishing your story and wondering if you even noticed that gaping plot hole. Cohesion is one of the most important elements in a well-written story, and fulfilling your foreshadowing is one of the most important ways to achieve that cohesion.

5. You End Up Taking the Plot in a Different Direction

Other times, you may plant your foreshadowing in early chapters with every intention of paying it off in specific ways later on. But… then your story takes over. A new idea strikes and your plot ends up going in an entirely unforeseen direction. The result? Your original foreshadowing not only doesn’t work, but you’re also lacking the foreshadowing you actually need for the new ending.

What Should You Do Instead?

Again, this isn’t a fun scenario. But it’s a straightforward fix: go back and rewrite. Frame your First and Third Acts, so they are asking and answering the same questions.

***

Frankly, it’s almost impossible to write a first draft that doesn’t include at least a few instances of unfulfilled foreshadowing. But if you know what to look for and the reason you might be wandering astray with your story’s foreshadowing, you can catch yourself in the act and smooth out all the lumps. That way, you’ll be able to hand your readers a gift they’ll appreciate far more than that lumpy knitted muumuu of Aunt Lou’s.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Can you think of an instance of unfulfilled foreshadowing you need to fix? How about foreshadowing you did appropriately fulfill? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/mistake-56.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 56: Unfulfilled Foreshadowing appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 3, 2017

5 Things I Learned When I Decided to Switch Genres

I was in the middle of mundane household chores when the idea for The Lost Girl of Astor Street struck: Veronica Mars meets Downton Abbey was my initial thought. Followed quickly by, But I’ve never written a mystery or a historical! There’s no way I could write that.

I was in the middle of mundane household chores when the idea for The Lost Girl of Astor Street struck: Veronica Mars meets Downton Abbey was my initial thought. Followed quickly by, But I’ve never written a mystery or a historical! There’s no way I could write that.

The idea nipped at me all day long.

As did the doubts.

I’ve written stories all my life, but I had never before experienced such fear about writing a story. My published titles were all contemporary YA novels, about girls trying to navigate the complicated social life of modern-day high school. Writing contemporaries comes with its own unique set of hurdles, but I had years of experience overcoming those. Did I really think I could handle something as complicated as a historical mystery?

I kept thinking of Holly Gerth, and her advice to:

Be courageous, and write in a way that scares you a little bit.

Did the fear mean that I was onto something with this idea?

Maybe you are considering writing a different type of book than you have in the past, whether that involves a genre switch, a different type of main character, a theme that makes you feel too vulnerable, or something else.

If so, here are five things I learned when I made my genre switch that I hope will help you along your way.

Top 5 Things to Know if You Decide to Switch Genres

1. Get Help From Someone a Few Steps Ahead of You

I’m fortunate to have a best friend who writes historical romance novels. I sent her a panicky, “Hey, I don’t know what I’m doing! I don’t even know how to begin researching this!” kind of text. She offered me simple, manageable advice.

The first thing to do is figure out exactly where and when your book takes place. That’ll help guide the rest of the process.

After she said it, it seemed obvious. Of course that should be my first step!

Maybe you aren’t fortunate enough to have a best friend already doing what you want to be doing, but we live in a lovely generation of shared knowledge. Where Maggie Stiefvater hands out free advice about crafting characters, Stephen King has written an entire book to tell you about his process, and most writers have a “How I got published” story somewhere on the web.

Maybe you aren’t fortunate enough to have a best friend already doing what you want to be doing, but we live in a lovely generation of shared knowledge. Where Maggie Stiefvater hands out free advice about crafting characters, Stephen King has written an entire book to tell you about his process, and most writers have a “How I got published” story somewhere on the web.

Who is writing the kinds of books you want to write? If you haven’t already done so, follow them on social media. Look through their blog archives. Read interviews they’ve given. They have knowledge that will make your journey easier.

2. Don’t Linger Too Long in Preparation

After I pinpointed the specific date and location of my story (Spring of 1924, Chicago, Illinois, the Astor Street district), I started to research. And research. And research. And research…

After a while, I suspected my research and preparation was becoming a cocoon of sorts, rather than a launching pad. Of course, the cocoon is necessary and valuable to the process of creating something new, but eventually you have to leave. I was experiencing something akin to Storyworld Builders Disease, which fantasy and sci-fi authors can go through, and I realized it was time to begin the actual writing.

3. Embrace the Messiness of Telling a New Kind of Story

After lots of starts and stops, I finally hit a good balance of when to write without pausing to research, and when I needed to go look up something. When I finished the first draft, I took my standard six weeks off, and then eagerly reread my creation.

Much to my disappointment, she was extremely messy. I still had a lot to learn about crafting a strong historical mystery.

4. Realize the Process Will Take Longer Than Expected

I had gotten pretty fast at writing my YA contemporary novels. I could throw down a first draft in 6-8 weeks and have edits done in 12.

My first draft of The Lost Girl of Astor Street took me three months, which I didn’t think was too bad. But then my edits took me a year. Whenever I got one element of the story fixed, it seemed like it highlighted three more pieces that were wrong.

My first draft of The Lost Girl of Astor Street took me three months, which I didn’t think was too bad. But then my edits took me a year. Whenever I got one element of the story fixed, it seemed like it highlighted three more pieces that were wrong.

If you’re writing a new kind of book under a deadline, make sure to build in more time than you think you need!

5. Have Faith in Yourself

Changing genres isn’t always a smart move for a writer, but if you have a story you’re burning to tell, I hope you’ll be encouraged to go for it!

While The Lost Girl of Astor Street thankfully found a good home with Blink/HarperCollins, writing the story would have been valuable even if it hadn’t. Because even if you don’t publish your book, you will learn so much about yourself and storytelling in the process of pushing yourself to try something new.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! If you could switch genres right now, what would you start writing? Tell me in the comments!

The post 5 Things I Learned When I Decided to Switch Genres appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 30, 2017

How to Find Exactly the Right Story Hook

What is your story hook? That can be one of the most frustrating questions for any author—for two reasons. Either you have no idea what your hook is, or you have no idea how to describe it.

The good news is both of these scenarios are quite common.

The bad news is they’re both deep doo-doo if you’re hoping to:

a) Write a book worth reading.

b) Convince anyone to read it.

For many authors, the big trouble in finding or creating a story hook is that it’s sometimes tough to see the forest for the trees. The hook is the tiniest of entry points into your vast and fascinating story. When you’re the ringmaster at the center of the circus—the one on the inside looking out—it can be downright tricky to figure out the best way to lure people inside the tent to see your fabulous show.

However, if you can’t find the entry point to your story, it often signals a bigger problem than just marketing trouble. It’s first and foremost a sign you’re struggling to find an awareness of and control over your story.

Fortunately, we’re gonna fix that today.

The Two Different Functions of a Story Hook

When writers talk about “the hook,” they might be talking about either of two related but different things.

1. The Hook in the Premise

This is the unique aspect of your story premise. It’s what makes your story stand out from all the other “different but same” stories in your genre. If you’re lucky, it’s what lifts your idea into the rarefied air of the eagerly sought-after “high-concept premise” that makes agents, editors, and producers see green $$$ and start salivating.

This is what screenwriter William C. Martell is talking about in his book Your Idea Machine when he asks:

This is what screenwriter William C. Martell is talking about in his book Your Idea Machine when he asks:

If a viewer had a list of 100 indie movie loglines in a TV guide or the onscreen cable guide—just a handful of words to describe each film—why would they select your film? What is the core element that makes your story idea different than the others?

For Example:

Q. What makes Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn different from other epic fantasies?

A. A unique magic system.

Q. What makes John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars different from other YA romances?

A. The protagonists are both dying.

Q. What makes Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple different from other whodunits?

A. The detective is a sweet little old lady.

Q. What makes Charles Portis’s True Grit different from other westerns?

A. It’s about a teenage girl bringing outlaws to justice.

Q. What makes The Book Thief different from other World War II stories?

A. It’s narrated by Death.

And the list goes on and on. There are no new stories, but almost all the truly memorable incarnations feature some unique element—however small—that offers a new slant on the same ol’ tale. If you remove any of the unique elements from the stories above, what’s left? Not something most of us would care much about reading, huh?

2. The Hook in the First Chapter

The other manifestation of the story hook is as the all-important structural element in your first chapter. This is a carefully chosen scene that serves to introduce the premise hook, grab readers, and pull them into the story.

Authors often mistake the structural hook for the Inciting Event (which occurs halfway through the First Act at approximately the 12% mark and in which the protagonist has his first direct encounter with the main conflict via his Call to Adventure). The hook is not the event that incites the story’s main conflict. But it is the first domino in the line of events that create your story’s seamless narrative weave. In that sense, it is the moment that begins everything.

But it’s more than that too. Above all else, it is a representative of your premise hook. If you think of the premise as a promise, then the first chapter is where that promise will initially be either kept or broken.

Why You Must Know Your Story Hook

The hook in your premise will define your entire story. The sooner you can identify and solidify your story hook, the more control you will have over creating your story’s entire narrative. This is yet another reason I love outlines: before I ever begin my first draft, I know my premise and its possibilities inside out. But even if you prefer to discover your story in the narrative drafting stage, you still need to have a firm grasp of your premise in time to let it influence your revisions.

The hook in your premise will define your entire story. The sooner you can identify and solidify your story hook, the more control you will have over creating your story’s entire narrative. This is yet another reason I love outlines: before I ever begin my first draft, I know my premise and its possibilities inside out. But even if you prefer to discover your story in the narrative drafting stage, you still need to have a firm grasp of your premise in time to let it influence your revisions.

If you fail to understand your premise, you will also fail to understand your story.

Whaaa? You tellin’ me I don’t know my own story, girl?

Yep, that’s exactly what I’m telling you. If you can’t find and identify this tiny beating of your entire story, then chances are excellent your story doesn’t actually have a beating heart. Or, just as likely, it’s struggling along, like Frankestein’s homunculus, torn between multiple hearts, all fighting each other to be top dog.

The result is a mess—and a sure indication of an author who has no control over his creation.

An author who doesn’t understand his story hook is an author who has no control over his creation.

On the other hand, when you have a firm grasp of your story’s premise, you automatically have a solid understanding of what your story is about. And when you know what your story is about, you will be able to direct its narrative with confidence in making the proper choices for its best interest at every step of the process.

Even better—when people (even agents!) ask you what your story is about (which is always code for: why should I care?), you’ll never have to struggle for an appropriate answer.

How to Use Your Story Hook to Create Your Opening Chapter

Your understanding of your story hook will influence every bit of your narrative. But the very first decision it will help you make is in your first chapter.

This always makes me happy. Why? Because the first chapter is arguably one of the most difficult chapters to write in the entire book. There is just so much an author must get right in order to properly introduce and set up the rest of the story. The most important of those first-chapter tasks is always, always, always entertaining readers.

If you did your job right in creating an interesting and unique story hook in your premise, then you’ve halfway hooking readers. So here they are looking at your first chapter. What are they going to find? Does it resonate with the expectations raised by the story premise? Even more importantly, does it fulfill those expectations?

Are you seeing the parallel here?

The hook in your story premise must create the structural hook in your story’s opening chapter. They’re linked. The premise says, “Here’s what this story’s about, and I promise you’re going to like it.” The opening chapter then says, “Here’s the story! It’s everything you wanted it to be, isn’t it?”

2 Ways to Introduce Your Premise in Your First Chapter

Sounds easy enough, right? But how do you do that? How do you leverage your premise to choose a gripping and fulfilling opening scene?

Start by asking yourself these two questions:

1. Is the Premise Present in the First Chapter?

The first and most obvious step is simply to make sure your premise is actually in your opening chapter. Whatever is interesting about your premise needs to either make an appearance or at least be teased right off the bat. There are two ways to do this.

1. Show the Premise in Action

In some stories, the premise will need to be developed over the course of many chapters in order to reach fruition (see #2, below), but in others, it can be shown in its full glory right from the start.

For Example:

In Fault in Our Stars, the promised premise is immediately available to readers: the protagonist has cancer, goes to a cancer support group, meets her love interest.

Same deal in The Book Thief. Readers are immediately introduced to the narrator Death (and the promised book thieving).

This is also an approach I was able to use in my historical/dieselpunk adventure Storming , which promised readers a woman falling out of the sky and gave them that in the very first lines.

Flying a biplane, especially one as rickety as a war-surplus Curtiss JN-4D, meant being ready for anything. But in Hitch’s thirteen years of experience, this was the first time “anything” had meant bodies falling out of the night sky smack in front of his plane.

2. Introduce the First Piece That Kicks Off the Premise

Other premises will need to be developed more slowly. If you were to immediately plunge readers up to their necks in the premise’s action, nothing would make sense and the hook would ultimately fail for lack of context.

However, this doesn’t mean you still can’t open with a piece of the hook. Just as the opening chapter itself is the first domino in your plot’s line of events, the structural hook can also be the first domino in a careful buildup to the premise’s full promised power.

For Example:

True Grit offers a hook that is more situational than those previously mentioned. The protagonist Mattie Ross can’t go after the outlaws until she has a reason to: first, her father’s death, then the local law establishment’s refusal/inability to measure up to her ideals. But the first chapter still neatly introduces its premise hook in its opening line:

People do not give it credence that a fourteen-year-old girl could leave home and go off in the wintertime to avenge her father’s blood….

Mistborn offers much the same with a prologue (one that actually works!) that sets up the political and social situation, along with an outside view of central character Kelsier, with hints at his exciting abilities and his fervor for the rising cause of revolution.

This was the approach I used in my portal fantasy Dreamlander . Its premise promises the protagonist will enter a parallel fantasy world through the access point of his dreams, but this event doesn’t actually happen until the Inciting Event. Still, I was able to immediately pay off the premise in the first line:

Dreams weren’t supposed to be able to kill you. But this was one was sure trying its best.

2. Can the premise be represented in microcosm in a cohesive opening episode?

Because the first chapter will introduce your protagonist in her Normal World before she has encountered the story’s main conflict, you will rarely want to open with that conflict in its full-blown state. Instead, you must create ways to introduce the character’s status quo, while still balancing the promise of the conflict to come.

An interesting way to approach this is to think of your first chapter as a mini-episode all its own. It presents a characterizing “story”—complete with beginning, middle, and end—that gives readers a glimpse of your main plot in the form of a symbolic microcosm.

This won’t work for all stories, but it is a common gambit in some movies.

For Example:

Peter Weir opens Master and Commander: Far Side of the World with an intense naval battle that immediately pays off his historical story’s premise.

P.J. Hogan’s adaptation of Peter Pan opens with Wendy’s jovial if gruesome telling of her favorite pirate story—about the ruthless, blue-eyed Captain Hook—which both symbolizes and literally foreshadows what is to come.

Ridley Scott’s Gladiator opens with what is a (strictly speaking) nonessential battle sequence that functions to introduce the characters and their Normal World—and, just as importantly, to pay off the premise and hook viewers.

This is the approach I used in my medieval epic Behold the Dawn , which opens with a (strictly speaking) nonessential battle sequence that introduces the protagonist’s brutal Normal World and leads directly into the actual plot’s first domino.

2 Questions to Double Check You’ve Chosen the Right Opening

After you’ve chosen a gripping and promise-fulfilling opening, double check it against the following questions to make sure you’re balancing the needs of the hook against the cohesion of the rest of the story. The most challenging balancing act of the opening chapter is remembering it isn’t just about hooking readers, but also about setting up the story to come.

1. Is Your Opening Scene the First Domino in Your Plot?

The trickiest trick of the opening is finding a hook that perfectly symbolizes your premise, grabs readers’ attention—and is still the first domino in your story’s narrative. It cannot stand by itself. Even if it is clearly a “standalone” episode (as in Gladiator and my Behold the Dawn), it must still lead into the main plot.

For Example:

The opening battle scene in Gladiator immediately moves into Emperor Aurelius trying to pass his throne to protagonist Maximus—which leads to the Inciting Event when the emperor’s jealous son murders him.

The opening battle scene in Behold the Dawn leads directly to the protagonist’s confrontation with the “heretic” monk known as the Baptist, who turns out to be an important face from his past, prompting the protagonist’s journey to the Crusade in the Holy Land.

2. Is Your Opening Scene Focused on the Setup of the Normal World?

Here’s another tricky balancing act of the first chapter: it must begin with the characters in motion, wanting something pertinent to the main story goal, and doing something that will eventually lead them to a meeting with the main story conflict—and yet, the first chapter isn’t about the main conflict. Not yet.

The first eighth of your story is your opportunity for setup. The characters will have goals and meet obstacles, but neither will fully solidify until the main story goal and main conflict arrive in the First Plot Point at the end of the First Act. This means you will rarely want to open your first chapter with the big guns of your main conflict. Instead, you must figure out how to set all that up, while still being as fascinating as possible.

For Example:

Read or watch any one of the stories I’ve cited about. They all pull this balance off masterfully, opening their stories in interesting, sometimes even intense moments, but still leaving room to build up to the main conflict in the Second Act.

Do Your Two Hooks Match Up? One Final Test

So now you’ve got a great hook for your premise and a great hook for your opening chapter. But how do you know it’s the right hook?

Easy. They match. The hook in the first chapter is a direct reflection and/or setup of the hook promised in your premise.

And if it’s not, then one or the other is wrong and you need to reevaluate your choices. Either you’ve started with a faulty premise (your story is really about something else), or you’ve chosen the wrong starting place to represent that premise. As Martell went on to say:

…the hook doesn’t just make the story sound interesting in order to attract an audience. It really defines the story itself and creates strong dramatic and emotional scenes. A hook is not just a gimmick. It’s a lens that we view the story through.

If you can discover and strengthen your story hook at every step in the process, you will have created an incomparable foundation for both your storytelling and, eventually, your marketing.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How have you represented your premise’s hook in your opening chapter’s hook? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/how-to-find-exactly-the-right-hook-for-your-story.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Find Exactly the Right Story Hook appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 27, 2017

7 Essentials for Your Book Launch

Congratulations, it’s a book! You accomplished something rare and impressive just by completing your masterpiece, not to mention surviving blood-boiling revisions and the agony of the publishing process. Now, the book launch date has been set and—surprise!—you have more work to do!

Congratulations, it’s a book! You accomplished something rare and impressive just by completing your masterpiece, not to mention surviving blood-boiling revisions and the agony of the publishing process. Now, the book launch date has been set and—surprise!—you have more work to do!

Orchestrating a book launch sounds daunting, but people need your book. Take a long slow breath and relax into the creative process of promoting your release. While there is no one-size-fits-all promotion plan, there are certain essential tasks that both traditionally published authors and independent authors should do to ensure a fulfilling book launch.

How to Prepare for Your Book Launch in 7 Steps

Following, are a few basics to get you started.

Book Launch Step #1: Ready Your Website

Your author website is the online version of your professional office or storefront. It could also be your catalog, your bulletin board, or your yearbook. It should not be a cobweb-covered single page you set up years ago and haven’t touched since.

Unless you’re an avid blogger, the author website won’t be how readers discover you. Instead, it’s where they will come to learn more about you. Your web address should be the simplest form of your author name as possible and should be the link you share more than any other.

Before you create (or update) your author website, look at the websites of a few of the top authors in your genre. Decide what you like about them. Notice some of the elements the websites have in common. Choose a theme (the layout and look of a website) that reflects your brand.

Book Launch Step #2: Ready Your Social Media

While the social media landscape changes as quickly as highly-caffeinated developers can write code, the purpose and best practices of an author using social media for book promotion remain the same.

It might take setting up an account on each major social media site and experimenting to find out what works best for you and where your readers will connect with you. The important thing is that you maintain a consistent, professional presence and, of course, that you choose a platform you enjoy.

Book Launch Step #3: Build Your Media Connections

Many radio and television programs feature authors, as do newspapers and magazines. Often local media outlets are more accessible to new authors.

Build your dream team by creating a signup form and promoting it online. The promise of an early review copy of your book might be all it takes to get book lovers and bloggers to join your team.

If you like the sound of your own voice, consider starting a podcast and interviewing others in the field related to your book.

Book Launch Step #4: Perfect Your Product’s Appearance

If you’re traditionally published, your publisher should ensure your book has been professionally edited and formatted and has an eye-catching, genre-appropriate cover. If you’re independent, it’s up to you.

If you’re signed to a traditional publisher, they might write compelling copy for your book. They might not. If you are an indie author, you will have to write it yourself. Either way, take the time to perfect your book description.

Also, consider writing a reader’s guide or book club questions to include in the back of your book.

Book Launch Step #5: Create Your Media Kit

A media kit (also called a press kit) can be as simple as a document file containing your author bio, professional photo, book release information, book cover image, book description, sample Q&A, book excerpt, and endorsements.

You might not have all of the information available yet, but go ahead and start the document so you can add to it as you go.

Book Launch Step #6: Find Potential Reviewers

Book reviewers can be found in groups on social media, on Amazon by looking at the reviews of comparable titles, and on book sites such as Goodreads. You can search online for book bloggers in your genre who accept review submissions. Create a signup form for new reviewers. Promote it on your social media and send it to your email list.

Book Launch Step #7: Find Potential Endorsers

Books endorsed by popular authors in the same genre or influencers in a related field tend to sell better than those without endorsements. Who might you ask for an endorsement? If you don’t know the potential endorsers personally, email them individually.

Need More Help With Your Book Launch?

Resources such as The Writer’s Book Launch Journal can guide you through the marketing and promotional tasks every author should do to ensure a successful book launch.

Resources such as The Writer’s Book Launch Journal can guide you through the marketing and promotional tasks every author should do to ensure a successful book launch.

Filled with checklists of essential tasks, an abundance of publicity suggestions, and questions to personalize your promotions, The Writer’s Book Launch Journal will lead you on the journey to a fun and fulfilling book launch.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What is the greatest challenge you see yourself facing with your next book launch? Tell me in the comments!

The post 7 Essentials for Your Book Launch appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 23, 2017

6 Bits of Common Writing Advice You’re Misusing

Recently, I found myself reminiscing about some of the early books on writing advice that transformed and molded my understanding of storytelling and writing. They opened my eyes, honed my craft, and changed my life. I wouldn’t be the writer I am today without the solid writing advice I’ve received from the writers who have gone before me—and neither would you. But here’s the thing. When taken out of context or used without wise moderation, even the best writing advice can sometimes accidentally point you in completely the wrong direction.

Recently, I found myself reminiscing about some of the early books on writing advice that transformed and molded my understanding of storytelling and writing. They opened my eyes, honed my craft, and changed my life. I wouldn’t be the writer I am today without the solid writing advice I’ve received from the writers who have gone before me—and neither would you. But here’s the thing. When taken out of context or used without wise moderation, even the best writing advice can sometimes accidentally point you in completely the wrong direction.

(Note: This is my friend Chautona’s book, not the not-so-good book we were referencing in our email conversation.)

A few months ago, I had an email conversation with fellow author Chautona Havig about how sometimes even an excellent story can be derailed by an inexperienced author’s well-meaning but misguided attempts to adhere to common writing advice. Chautona commented about one book in particular:

It’s like the author took every ‘rule’ about writing and applied them in all the wrong ways. It HURTS. And it really is a good story.

The entire art of writing a story is all about balance. When we take these so-called “rules” and try to apply them across the board, with no understanding of how to massage them to fit specific circumstances in the story, we often end up with a clunky presentation that alienates readers.

And yet, writers often feel bound to the rules and guilty when we break them. So we double down and obsessively apply the rules everywhere they seem possibly applicable. That’s safer than trying to judge for ourselves when certain rules are applicable and when they’re not, right?

Sure. But “safe writing” is nowhere near the same thing as “good writing.”

Today, let’s take a look at 6 common bits of writing advice I see abused far too often by good-intentioned authors.

6 Snippets of Writing Advice You Must Use–But Never Abuse

Before we get started, I want you to take a gander down the 10 bits of writing advice in this section. If you’re looking just at the headers, then what you’re seeing is good advice. You want to accomplish all of these things in your stories.

But.

You must be able to approach even the best writing advice with common sense, an understanding of the essence of the advice more than its explicit definition, and, most importantly, an awareness of your story’s big picture and its requirements. Once you can do that, you can proclaim yourself a black-belt master of every single one of these “rules.”

1. Write a Likable Character

You hear it all the time. If you don’t create characters readers like—and especially a protagonist readers like—why would they ever want to read your story? Stories are made or broken on the strength of their characters, which means you must get readers invested in your main character right from go.

Common writing advice says your protagonist must be likable. But don’t confuse likability with perfection. Readers love flawed characters.

What Writers Sometimes Think This Means:

The problem is that writers sometimes think this means they must write a character who is an utter saint. If he makes a mistake, if he speaks in anger, if he’s selfish, if he sins—readers will instantly judge him, hate him, and drop him. Instead of creating a realistically flawed (and interesting) human being, these writers end up with either a

a) a self-righteous goody-goody

b) a self-flagellating goody-goody

The irony here is that “perfect” characters are hardly ever likable characters.

What This Bit of Writing Advice Really Means:

Because we often equate other people’s ability to like us with our ability to avoid of messing up, we think the same must apply to our characters. But (aside from the fact this is an utterly false paradigm) consider some of your favorite characters. I’m willing to bet most of them are egregiously flawed. And don’t you love them the more for those flaws?

When you’re told to “write a likable character,” what you’re really be told is to “write a realistic, compelling, relatable, interesting character.” So give him a relatable motivation and pile on the sins, because readers have a high capacity for forgiveness.

2. Write Unpredictable Endings

This is a question I’m often asked: If I foreshadow my ending, won’t readers see it coming and be bored?

Suspense in a story is largely fueled by readers’ curiosity. They don’t know what’s going to happen, so they keep reading to find out. If they can see a clichéd ending coming, they’ll have no reason to turn another page. Been there, done that, right? Which means authors must exercise their innovation and ingenuity all the way through the book and nowhere more so than in the ending.

Common writing advice says your story’s ending should be unpredictable, but what this really means is that your foreshadowed ending must be original.

What Writers Sometimes Think This Means:

Too often, writers hear this well-meaning writing advice, telling them to surprise readers with their endings—and they take it to mean the ending should be completely unforeseen. So they pull an unforeshadowed plot twist out of left field, smack the readers upside the head with it, and then expect readers to be delighted because they didn’t see that coming!

That’s certainly true as far as it goes. But here’s the thing: pulling a completely unforeshadowed plot twist out of left field is cheating. Yup, cheating. And readers are more likely to write you passionate hate letters than applaud your imagination.

What This Bit of Writing Advice Really Means:

Forget the idea that readers want a completely unexpected ending. That’s an utter falsehood. What they want is ending that fulfills their expectations (via foreshadowing) without being clichéd. The mark of a good story is one that engages readers time after time, long after any surprise has worn off. What’s most important is that you’re being true to the story and you’re saying interesting things in new ways.

3. Avoid Detailed Descriptions

No less than the late great Elmore Leonard backs this one up in his “10 Rules for Good Writing“:

8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

One sign of a great writer is the ability to spark the readers’ visual imagination with a modicum of information. Experienced readers need only one or two right details to get the picture; anything more is overkill.

Common writing advice says you should avoid descriptions, but this doesn’t mean you should avoid descriptions altogether. Rather, learn to describe the right details.

What Writers Sometimes Think This Means:

Now raise your hand if you’ve ever read a (probably unpublished) book in which the characters walked around having conversations in a complete blur. You had zero idea what the characters looked like, what the setting looked like, or where the characters were situated within it. I call this “White-Wall Syndrome.”

As far as readers know, the characters exist in a vacuum, since the author has refused to provide any physical context to flesh out the scene.

The result is not only confusing to readers, it’s also boring. A good setting has the ability to be almost a character unto itself—but not if readers can’t see it, smell it, touch it, and experience it, via well-chosen description.

What This Bit of Writing Advice Really Means:

Do not—repeat: do not—throw all your descriptions out the window right alongside the baby and the bathwater. Description is a vital part of storytelling. Without it, what you get is, at best, a highly avant-garde experiment. Indeed, description is one of the four pieces that make up written fiction (along with action, dialogue, and internal narrative).

In short: you need description.

What you don’t need are long, flowery, overly detailed descriptions that tell readers a bunch of stuff they don’t need to know in a way that is anything but interesting. Instead, learn to give readers the details they need when they need them, in a way they will enjoy rather than skip.

4. Flesh Out Your Minor Characters

Your protagonist may make or break the show, but the supporting cast is just as important to the success of his story. If your minor characters are boring, flat, and clichéd, your entire story will suffer. This means you must lavish just as much attention on the little people as you do your shakers and movers. Even your smallest of walk-on characters need to strike readers with just as much realism and charisma as your larger-than-life protagonist.

Common writing advice says you must flesh out even your minor characters—and you should! But you must do it artfully, using only story-pertinent details.

What Writers Sometimes Think This Means:

Every character is the hero of his own story, right? And that’s exactly what some writers seem bent on doing: writing an entire story for every minor character, however insignificant they actually are within the plot. When you end up telling a minor character’s entire life story just to “flesh him out,” you know you’ve gone too far. In fact, even just sharing a single detail about this character if it is not pertinent to the story is a bridge too far.

If you introduce your walk-on taxi driver with a lengthy conversation about his large family, you’re telling readers this man and his family are important—to the plot, to the protagonist’s development, or to the thematic premise. In short, every minor-character detail you include had better be doing double or triple duty, rather than simply serving to tell readers, “See, look, this guy is a real human being! No, really!”

What This Bit of Writing Advice Really Means:

By all means, bring your minor characters to life. But do it deftly. Do it in a way that creates irony and subtext—and most importantly moves the plot forward.

A great example is from William Wyler’s classic film Roman Holiday. Early on when Gregory Peck’s reporter unknowingly stumbles upon Audrey Hepburn’s passed-out princess, he tries to fob her off on an Italian cab driver. When this man (whom we never see again) protests by trying to communicate that he needs to get home to his large family of “bambino” who “mwhaaa!”, he is instantly characterized as a very real person—with a modicum of details, zero exposition, and in a way that is directly pertinent to the plot.

5. Add Conflict to Every Scene

Here’s one you hear a lot these days: conflict, conflict, conflict. Without it, you have no plot and no story. If characters aren’t fighting, struggling, overcoming in every single scene, the forward momentum of the plot will founder, and readers will grow bored and give up on the book. More than that, conflict is directly related to the pertinence of any scene within your story. If something isn’t happening to push the conflict forward, then chances are high that scene can and should be trimmed from the story.

Common writing advice says you must include conflict in every scene—and you should! But you must make sure it is story-driving conflict, rather than random arguments.

What Writers Sometimes Think This Means:

In their determination to include the magic story elixir of conflict, writers sometimes end up manufacturing it. The result is random conflict—arguments, obstacles, and even physical altercations that actually do nothing to move the plot.

Turns out, conflict all by itself is not a surefire indicator of a scene’s plot-progressing necessity. Too often, writers feel their story is lagging (particularly in the Second Act), so they throw in a random argument between allies—or the neighborhood bully attacks—or there’s a car wreck—or who knows what else. The result is, at best, melodrama. At worst, readers will be just as bored as if the characters really were doing nothing.

What This Bit of Writing Advice Really Means:

It’s not enough to throw in a random argument to spice things up. Every bit of conflict in every scene must function as part of the overall plot, creating a seamless line of scene dominoes—one knocking into the next—that progresses your story from beginning to end.

Just as importantly, every bit of this conflict must pertinently impact your character’s arc and your story’s theme. If it misfires on any of these three levels—plot, character, or theme—it risks irrelevance and must be reexamined to strengthen it into something with the ability to truly power your story.

6. Use Action Beats Instead of Dialogue Tags

This one goes in hand in hand with another of Elmore Leonard’s 10 rules: “Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue.” In the same spirit, why not just ditch dialogue tags (“said,” “exclaimed,” “questioned”) altogether in favor of action beats (“he looked up”)?

Action beats carry twice the weight as a dialogue tag. They tell readers who’s speaking while also providing context for the setting, the character’s body language, and the emotional subtext. Nine times out of ten, you can ditch the dialogue tags altogether and let your action beats carry the weight of your characters’ conversation.

Common writing advice says you should punctuate your dialogue with more action beats than speaker tags. But the only good action tag is one that does double or triple duty in defining your characters and their story.

What Writers Sometimes Think This Means:

Instead of using their action beats to actually add something to the scene, writers sometimes just scatter them in randomly for no other reason than to indicate the speakers. Here’s an example based on the book Chautona and I were discussing in the email exchange that prompted this post:

Jane smiled. “Do you think that is the right answer?”

“Why, no, I don’t.” John touched the ash tray before him.

Jane’s shoulders sagged. “I thought it had to be.”

“Well, it’s not.” He flicked the ash tray [which appeared out of nowhere and is never seen again] across the table.

As Chautona said to me:

Dick and Jane styled action beats. ARGH.

Action beats such as these add zero to the story. Half the time, they’re not even going to be necessary to indicate the speakers after the start of the conversation. The only thing they do is clunk up your prose.

What This Bit of Writing Advice Really Means:

As with so many of these rules of writing advice, what’s really meant is “do this, but do it well.” Do use action tags, but don’t just casually throw them into your dialogue hither and yon. Instead, craft them just as carefully as you do the dialogue itself to provide pertinent context that uses contrast and irony to avoid being on-the-nose.

If that ash tray isn’t going to either advance the action in this scene (e.g., Jane grabs it and throws it at John’s head) or symbolize the characters’ inner states (e.g., John is distracted from Jane’s problem because he’s desperately trying to stop smoking), then you need to dig deeper for an action beat that offers more than just visual clues to the characters’ surroundings.

***

Sometimes learning the “writing rules” can seem like an exercise in learning how to use them but not use them too much. Honestly, that’s not too far off the mark. But it’s a balancing act worth pursuing. All writers must serve a term of apprenticeship, in which they are governed by the rules. But there then comes a point when you understand both the context and subtext of common writing advice and can rise above to master them: you control them, not the other way around.

The mistakes I’ve outlined in this post may seem ridiculously intuitive. After all, you’re just trying to do what the rules say, right? But if you can learn to move past what the rules say to what they mean you’ve taken a huge step down that road to mastery.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What is the most confusing bit of common writing advice you’ve ever heard? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/6-ways-you-are-misusing-common-writing-advice.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 6 Bits of Common Writing Advice You’re Misusing appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 20, 2017

The Most Common Manuscript Malfunctions (and How to Avoid Them)

Editors see hundreds of manuscripts every year, from new and veteran writers alike. Almost all of them fall down on the same points. To help you avoid the common pitfalls of fiction writing, here are the manuscript malfunctions editors see most often, with tips on how you can avoid them!

Editors see hundreds of manuscripts every year, from new and veteran writers alike. Almost all of them fall down on the same points. To help you avoid the common pitfalls of fiction writing, here are the manuscript malfunctions editors see most often, with tips on how you can avoid them!

Manuscript Malfunction #1: Clichés

Clichés are at top of the list because they’re the easiest manuscript malfunction to commit. You use clichés every day without realizing it, whether you’re describing “falling head over heels” in love with someone or asking your kids if they think you’re “made of money.” Unfortunately, clichés can turn even the most exciting scene into dull prose.

How to Avoid This Manuscript Malfunction

Clichés are most often found in your descriptions. When copy editing your work, take a close look at your similes, metaphors and adverbs. If you think you might’ve read them somewhere before, change it up. Turn “eyes as blue as the sky” into “eyes the color of crushed cornflowers.” Not only does this make your writing more interesting, it also creates a vivid picture for your reader.

Manuscript Malfunction #2: Overwriting

Why say something in fifty words when you could say it in ten? Brevity increases clarity, as well as quickening pace and make startling images “pop.”

How to Avoid This Manuscript Malfunction

Read this out loud:

She looked left and right down the path, but as she saw no one coming, she hurried quickly into the forest. The darkness cast by the trees immediately swallowed her, and seemed to wrap itself around her neck, force its way into her lungs. As she ran, she choked on it.

Right. Now try this much shorter version.

She hurried into the forest. The darkness wrapped itself around her neck, forcing its way into her lungs. As she ran, she choked.

Better, right? Try reading your work out loud, then taking out a red pen and deleting all the unnecessary words.

Manuscript Malfunction #3: Double Adjectives

With great adjectives come great responsibility. Don’t dilute your existing adjectives by adding still more. For example:

He sat on the hard frozen ground and felt sharp spikes of grass poke through his black leather gloves.

Way too many adjectives in this sentence. Even removing just one from each pair makes it easier to read:

He sat on the frozen ground and felt spikes of grass poke through his leather gloves.

Or, even better still, turn your adjective into a verb for an extra punch:

He sat on the frozen ground; the grass spiked through his gloves.

How to Avoid This Manuscript Malfunction

Some writers work best on paper. Printing your manuscript is a great way to gain a new perspective and makes spotting this kind of malfunction easier.

Manuscript Malfunction #4: Soggy Speech

Dialogue is difficult to get right. Make it too real, and your scene will get bogged down with “um’s” and “er’s” that don’t add anything to the scene. Go the other way however, and your characters become wooden.

How to Avoid This Manuscript Malfunction

Use a mixture of speech and indirect action to get your point across. And—just like in the points above—if it doesn’t need to be there, cut it out. You can find an in-depth look at the pitfalls of dialogue and how to fix them, here.

Manuscript Malfunction #5: No Unique Selling Point

This is a big one, as it refers to the book as a whole, rather than things easily remedied by a copy edit. Unfortunately, it’s also one of the most common reasons for a book being rejected by a publisher. Your book might be well-written, warm, and even exciting, but if it doesn’t offer anything unusual a publisher can use to “hook” readers, then it’s going to struggle to find a place.

How to Avoid This Manuscript Malfunction

In the first instance, write a book that’s unusual. This might be an unusual narrator (like The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time), a unique concept (like in The Time Traveler’s Wife), or even a contentious subject (The Slap). If you’ve already written your book, but aren’t sure what your “hook” is—give it to a friend to read and then ask her to tell you what it’s about. What’s the first thing she says? If it isn’t clear, you might want to rethink your concept.

Fortunately, everything in this list is easily fixed (yes, even #5!). By making these edits yourself, you can save a lot of time and money later down the line when you come to hiring an editor or agent. Good luck!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Have you ever had to deal with any of these common manuscript malfunctions in your story? Which one? Tell me in the comments!

The post The Most Common Manuscript Malfunctions (and How to Avoid Them) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 16, 2017

How to Outline a Series of Bestselling Books

Every good series has to start somewhere. If you’re of the mindset (as I am) that a problem as complicated as the novel is best approached from the big-picture view of an outline, then it only makes sense that the even greater complexities of serial fiction will benefit even more when their authors understand how to outline a series.

Every good series has to start somewhere. If you’re of the mindset (as I am) that a problem as complicated as the novel is best approached from the big-picture view of an outline, then it only makes sense that the even greater complexities of serial fiction will benefit even more when their authors understand how to outline a series.

These days, books run in packs. The vast majority of authors are writing sequels and series. Aside from the fact that series are fun and offer the opportunity to return to beloved characters and settings, they’re also a smart marketing decision. Hook readers with one book, and they’re likely to return for the rest of the series.

Easily the most frequent follow-up question I’ve gotten over the years to my book Outlining Your Novel is: “How to outline a series?” I’ve hedged and hawed on that, offering a few logical suggestions here and there. But up until now, it isn’t a subject I’ve felt qualified to write about since… I’d never written a series.

And I’m glad I waited. Last year, I began my first-ever series when my originally standalone portal fantasy Dreamlander turned into a trilogy on me. Outlining the follow-up books has been an entirely different, multi-faceted, and incredibly rewarding experience. Figuring out the real-time steps of how to outline a series has exploded several of my preconceptions about the process and taught me much more about both outlining and storycraft in general.

Ready to find out how to outline a series of books you’ll be proud of and readers will love? Let’s get started!

Should You Outline the Whole Series or One Book at Time?

This is probably the most common question I receive about how to outline a series. Obviously, my approach to the Dreamlander trilogy has been a little wonky, since I wrote and published the first book with no intention of following it up. I outlined the first book with no idea there would be sequels, and now that I am outlining the sequels, the first book in the trilogy is already set in stone and I only have to worry about the remaining two.

The approach I’m finding works best is basically the one I’ve been recommending all along: outline the overarching story upfront, but not all the books.

The whole point of outlining, whether you’re working on a standalone or a series, is that you discover the story’s end, so you can then appropriately set up the beginning. This is arguably even more true of a series, in which the big-picture resonance of the overall plot and theme will be even more hotly anticipated by patient readers, who sometimes wait years for the payoff in the end.

The secret of tremendously powerful and popular series is that the ending is always present in the beginning. Authors such as J.K. Rowling knew how the story would end right from the beginning.

However, this does not mean you need to write a complete outline for each book in your series right at the start. Especially if you’re like me and your outlining process is in-depth and detail-oriented, it may actually be counter-productive to hammer down all the details of your later stories until you’ve written the earlier ones.

An outline, however thorough, is never the final story. Many important details will inevitably change during the writing of the first draft. If too many of those changed details pile up, you may find the original outline you wrote for Book 3 or Book 4 suddenly doesn’t work.

Your Game Plan for How to Outline a Series #1:

As you’re working your way through your story’s plot holes, figuring out where events are going and what your character’s transformation will be in the end, you should end up with an overall picture of your series’ arc. It’s good if you have an idea of at least the shape of each of the three acts in your planned follow-up books. Keep track of the big moments you discover, which may turn into your major plot points in later books.

Beyond that, you only need to explore future books insofar as you have questions about them that affect your current book. Go ahead and finish this book’s outline and first draft. After that, you’ll have a solid foundation for the books to follow, and you can dive into their individual outlines one by one.

How Should You Plot Each Book in a Series?

Another question I frequently hear is: “How can I keep the main conflict going in my series without making the individual books feel incomplete?”

This is an excellent question, because there’s little readers detest more than stories that cliffhang them for no good reason.

Now, it’s important to differentiate between a cliffhanger that hooks readers into the next book (see the final section in this post) and a cliffhanger that simply leaves all the book’s conflict questions unanswered. Even within a series that features a focused overall plot, each episode within that series must be complete unto itself.

Otherwise, you risk reader frustration. Why did they spend six hours reading this crazy book if they don’t get to find out what happens?

Your Game Plan for How to Outline a Series #2:

Your overarching series will have a dramatic premise of its own. The protagonist’s main goal within the plot and main Lie within the theme will not be resolved until the Climax of the last book within the series.

However, each book within the series must also have its own “mini” dramatic premise. The protagonist will not reach his main plot goal until the end of the series, but she will definitely gain or lose the individual plot goals she is seeking within each story.

For example, Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin’s overall goal in Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey/Maturin series is to “defeat Napoleon.” The series goes into the double digits without them accomplishing this. Each book, however, features its own dramatic premise, centered around a specific plot goal, which the characters either definitively succeed or fail in reaching. Each book feels complete unto itself, even as the overall story keeps on trucking.

Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey/Maturin series is a standalone series, in which each book presents its own independent adventure, even as the story’s overarching goal of “defeat Napoleon” continues from book to book.

This is even more important within a series that does not feature a prominent overarching plot. In a series that is more episodic in nature (such as some romance and mystery series), each story essentially functions as a standalone, even though a few subplots may continue from book to book to tie it all together.

How Should You Structure Your Series?

Each book within the series will, of course, maintain its own proper adherence to the pacing of the main structural beats. But what about the larger story? How can you structure that over the course of multiple books? This is where I had to challenge some of my preconceptions about outlining a series.

I’ve written previously about how you can simply divide the number of books in your series into the overall structure to figure out where to place your major structural moments. (For example, in a trilogy or a quartet, each book can, essentially, function as either one of the acts or one of the quarters of the overall structure.) While this approach isn’t wrong, I’m learning it’s pretty simplistic.

The overall story structure will usually not line up quite so neatly, book by book, in a big, complicated series that features multiple turning points, perhaps multiple character arcs (see next section), and possibly an uncooperatively uneven number of books.

Your Game Plan for How to Outline a Series #3:

What I discovered was that figuring out how to outline a series is where a solid understanding of structure becomes even more useful. Because you can no longer rely so heavily on the easy timing equations of a single-book structure, you must step beyond the facts and into the theory of structure, using your own story instincts to determine how best to control the emotional flow of the overall series.

For example, in a trilogy, you’re usually going to find the following:

Book 1 functions as set-up, an origins story of sorts—in which the protagonist first encounters the main conflict and probably experiences an early victory.

Book 2 is a descent into the darkness of the conflict—in which the protagonist is often temporarily overcome, facing a dark moment of defeat.

Book 3 then signals the climactic period—in which the character rises from his defeat into his final heroic pose.

That said, you definitely still want to make sure your major structural moments are obvious within the overall flow of the story. The middle book should feature an obvious Midpoint that signals a shift into the full-on conflict of the second half (as we see, for example, in Goblet of Fire). In a trilogy, the second book will often end with the low moment of the overall story’s Third Plot Point (but remember, of course, that the third and final book will still feature its own complete structure with its own individual Third Plot Point).

The timing will depend entirely on how many books you’re featuring—which is yet another reason outlining your overall story idea in the beginning is incredibly helpful.

What Role Should Character Arcs Play in Your Series?

Here’s another question I hear: “Can your protagonist follow more than one character arc over the course of a series?” Originally, I thought, Naw. It’s an overarching story, right? So there should be an overarching character arc. That may be true, but it’s not quite as simplistic as it looks on the surface.

As I dug into character arcs for my sequel Dreambreaker, I realized one of the characters would be demonstrating a different arc in each of the three books. I wanted this character to ultimately follow a Positive Change Arc, but along the way, this character first had to follow two different types of Negative Change Arcs: a Disillusionment Arc in Book 1 and a Corruption Arc in Book 2, before finally being able to enter a Positive Arc in Book 3. Another character, however, clearly followed an overarching Positive Arc over the course of all three books—while still overcoming individual Lies/Truths in each book.

Your Game Plan for How to Outline a Series #4:

Just as your series will have an overarching dramatic premise to guide its plot, it will also have an overarching thematic premise to guide its theme and your characters’ arcs. You need to know right from Book 1 where your characters will end up in Book Z and what Truth their end will be proving.

However, just as structure is surprisingly flexible within the overarching story of a series, so are character arcs and theme. Pay attention to what feels right and allow your characters to follow logical paths of light and darkness on their way to their final Climactic encounter.

What’s important is making sure your character’s ultimate end in the final book is foreshadowed in the beginning. The last thing you want is for your character’s redemption or fall to come out of the blue. It needs to be a steady progression of everything that’s happened to him. Fortunately, in a series, you have all kinds of space in which to explore and develop this inner journey.

How Should You Plan to Connect Each Book in the Series?

In my exclusive Wordplayers group on Facebook (which you can find out how to join here), Vickie Owens asked me,

How should you connect book one and book two in a series? I’m looking for how to end the first book in the last chapter (create a hook or something) and start the first chapter in the second book.

As I touched on briefly in the second section in this post, one of the keys to a solid series is making sure each book is a solid episode within that series. Each book’s individual plot and its loose ends must be tied off within itself.

However, that is still going to leave hanging the loose ends from the main overarching plot. The protagonist will have reached his mini-goal for this episode, but his big plot goal is still out there beckoning—the main antagonist is still out there leering in the darkness. There’s plenty of unfinished business.

That’s what you use to hook readers into your next book.

Your Game Plan for How to Outline a Series #5:

Your individual book’s Climactic Moment will have answered its individual dramatic question. You can then use that book’s Resolution to tie off the loose ends remaining from this individual plot line. What you get to do then is to, in essence, raise the next book’s dramatic question.

What aspect of the main conflict will be most pressing in the next book?

What will be the individual main conflict in the next book?

These are both questions you can use to create a hook of uncertainty that will grab readers’ curiosity and pull them right into the next adventure. Consider how Thor: The Dark World ends with the antagonist Loki on the throne of Asgard. His presence there doesn’t affect the resolution of that individual story’s plot questions, but it does raise a whole slew of questions for the next story.

After resolving its main conflict with the Dark Elves, Thor: The Dark World then teases the series continuing conflict with antagonist Loki.

As I’m discovering, figuring out how to outline a series is a tremendously exciting and fun challenge that takes the principles of storytelling up to a whole new level. As useful as outlining is when writing a standalone book, it becomes vastly more so in creating a cohesive and powerful series that grabs reader from installment to installment and resonates deeply in its final resolution. Are you up to the challenge?

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Have you figured out how to outline a series of your own? Or do you prefer to skip the prep stage? Why or why not? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/how-to-outline-a-series-of-bestselling-books.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Outline a Series of Bestselling Books appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 13, 2017

Boba Fett’s Guide to Writing Cool Characters

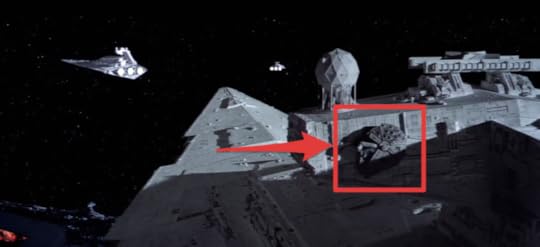

Boba Fett is one of the most beloved scourges of the Star Wars universe. Yet, he says only 27 words (28 if you add the Wilhelm Scream), and is on screen for a mere 6 minutes and 32 seconds.

Boba Fett is one of the most beloved scourges of the Star Wars universe. Yet, he says only 27 words (28 if you add the Wilhelm Scream), and is on screen for a mere 6 minutes and 32 seconds.

He even gets defeated in a pathetic way by being knocked into the Sarlacc pit by a blind Han Solo. And yet, fans look past that and still love him as one of the greatest characters.

Why is this?

Sure he’s got cool Mandalorian armor and a Clint Eastwood swagger. But that only adds to what we witnessed in the films.

2 Reasons Boba Fett Is the Coolest of Cool Characters

We love Boba Fett for two reasons:

1. A representative statement made by one particular character.