K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 50

March 13, 2017

5 Rules for How to Write a Sequel to Your Book

Just when you think you’ve figured out how to write a book, you realize you have to learn a whole new set of rules for how to write a sequel.

Just when you think you’ve figured out how to write a book, you realize you have to learn a whole new set of rules for how to write a sequel.

You’d think writing the second book in a series couldn’t be that much different from writing the first one. They both have a beginning, middle, and end—three acts, all the usual plot points, rising and falling action, etc., etc., etc. (said your best Yul Brynner voice). Even better, you’ve already done the hardest part of the foundational work, right? You’ve already successfully made it through one whole book with these characters, which means you already know what they like for breakfast, how they survived their childhood nemesis, and what their go-to move for bad-guy kicking will always be.

So far, so good. But it’s also true a sequel is a new animal in its own right, with its own set of unique questions and challenges—ones you maybe never even dreamed of when toiling through that first book.

I am now almost a year into my first experience with a sequel—the second in an unexpected trilogy, beginning with my portal fantasy Dreamlander. Having just completed its ginormous outline and now standing on the brink of streamlining it all into a cohesive first draft, I am excited to report it has been an amazing experience. The chief question I’m left with is: Why didn’t I do this sooner?!

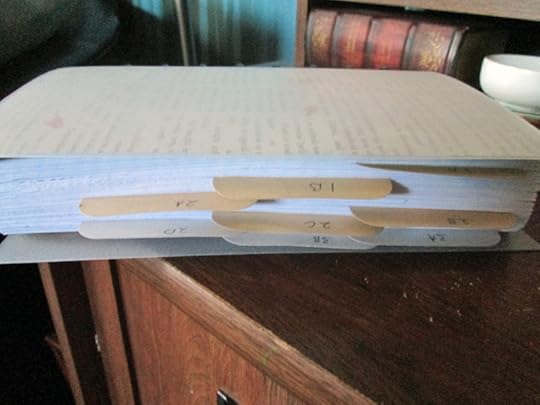

My deliciously ginormous completed scene outline (aka, extraordinarily rough draft) for Dreambreaker.

I have also learned a ton, about storytelling in general and, of course, sequels in particular. I’ve already written about how to determine the best ideas and approaches for your sequel ideas, as well as how to plan and outline your overarching story throughout the entire series. But today, it’s time to consider how to write the sequel itself.

Reader Lauren Fulton sent me an email on the subject, asking almost all the most important questions any writer can raise about how to write a sequel:

I’m working on a sequel right now and would love your thoughts on how else a sequel differs from the first book. How can we use the relationships readers have already built with characters to jump right in, without having the slow build up of getting to know the cast? Do we need to explain to readers why this story doesn’t have all the elements of the previous one?

Top 5 Guidelines for How to Write a Sequel

Let’s get our boots on the ground and go over five of the most important tactics for how to write a sequel that fulfills (and maybe even exceeds) your readers’ expectations.

1. How to Open Your Sequel’s First Chapter

Honestly, one of the most important questions of any book is—where to begin? Almost all of the same rules for beginning your standalone book’s chapter also apply to your sequel. If anything, a sequel’s opening chapter offers you more opportunities for great hooks with fewer burdens for introducing important story elements.

Historically, the opening chapter has been one of the most difficult parts of any book for me. There is just so much to juggle from the first line on. You have to introduce the protagonist in a characteristic moment that defines him, as well as a scene that introduces or hints at the main story conflict, illustrates the theme, and absolutely thrills readers.

Of course, a sequel’s opening chapter also has to accomplish all of this too, but it’s actually a much easier challenge, if only because you’ve already been there, done that in the previous book. When I originally wrote the first chapter of Dreamlander—the trilogy’s first book—I had to take into account that readers knew nothing about my character or the story world or the premise that people were living two different conscious lives, one waking in our world and another in a parallel fantasy world they visited in their dreams.

I had to open that story with a protagonist who was just as clueless as the readers—which meant it was actually really hard to come up with a Normal World hook that fulfilled all the necessary requirements. (The opening scene that ended up in the book—which I was pretty happy with—was actually an eleventh-hour edit just weeks before publication.)

But guess what? *happy dance* I didn’t have to mess with that in the sequel. I got to jump right into the heart of the story, with a protagonist who was already in the know about what was happening to him and who was, in turn, able to help readers ask all the right questions about why it was happening.

When figuring out how to write a sequel, your opening scene might actually be easier to write than it was in Book 1.

However, your sequel’s opening chapter will also present some of its own unique challenges. The Hook must still be a Hook—not simply a continuation of the final scene from your last book. And even though you won’t have to introduce your protagonist, plot, and theme from scratch, you will have to reframe them in a way that reminds readers where things stand and gives them a foundation for moving forward in this book’s unique dramatic and thematic premises.

You must choose a sequel’s opening scene with just as much care as you used for the first book. What scene will dramatize not just who your character is, where he’s at, and what he’s doing—but what scene will best show readers how the character has changed from Book 1 to Book 2?

You must also determine how much time should pass between books. Sometimes this answer will be obvious, sometimes not. But if you skip too much time, you may find yourself unwittingly jumping over some of the events readers were most desperate to know about in the aftermath of the first book. Take a step back and ask yourself: What is my readers’ most pressing question after the first book? See if you can answer that question or at least acknowledge it in your first chapter, to pull them right back in.

2. How to Explain Book 1’s Events in Book 2

A question I commonly receive is: How to share the events of the previous book in the second book? How much do readers need to know? And how can you remind them (or catch them up to speed if they’re accidentally starting with Book 2) about everything that’s already happened in this story?

Even though this is a common concern among writers, it’s actually an incredibly easy fix. All you got to do is treat the events of Book 1 as backstory. Pretend you’re starting all over with Book 2. Wipe the slate clean. Readers do not need to be told about any of the events Book 1 unless and until those events become pertinent context for what’s happening in Book 2.

How to write a sequel 101: There is no need to get sucked into the “backstory” your previous book’s events. Focus on the future!

Forget those page-long summaries of previous events and focus on what’s important in this story. If your protagonist is stranded on the moon in Chapter 1, then, yeah, you’ll need to acknowledge how he got there. But a simple sentence about that “no good space smuggler Ricardo marooning me” is probably going to be enough.

3. How to Up the Stakes Without Being Repetitious

Just as in a standalone book’s Climax, a series is going to want to save the best stuff for last. This means that, theoretically, the story should get more and more intense and exciting with each new book. If we just keep it simple and say you’re writing a trilogy, this means Book 2 should have higher stakes and more good stuff than Book 1, and Book 3 needs to be higher and bigger still.

But if you did like you should have and gave Book 1 everything you’ve got, what does that leave for the sequels? Just as importantly, how can you give readers more of what they liked in the first book without snowballing into repetition?

There are two keys.

Key #1: Each Book Should Be “Same But Different”

It’s true: readers want more of the same. They loved what you gave them in the first book, and now they’re back for more. But what they really want is to look at the same subject matter, but from a different angle.

This is why Susanne Collins’s sequel Catching Fire featured the Hunger Games all over again, but in an entirely different setting, with different goals and different stakes, for entirely different reasons.

Susanne Collins gave her rabid fans exactly what they wanted in her sequels: the same, but different and deeper.

This is why sequels always have the opportunity to be better than the first book, if the author is gutsy enough to take advantage of its opportunities. Sequels shouldn’t be repeats; they should be expansions. In short: the same, but more.

Key #2: The Stakes Must Be an Evolution

And that brings us to Key #2. Discovering new, better, and different stakes for your sequels is all about building off what you did in the first book. Consider how you can take your character’s victories from Book 1 and turn them into consequences. Again, Hunger Games is a good example. Katniss beat President Snow to survive, but as a result, she becomes Public Enemy #1 in Books 2 and 3.

Take a look at whatever was most awesome in your first book. Take a look at what events hurt your characters the most. Take a look at the weak spots they never really had to face and are still covering up. Take a look at your antagonistic force and consider their most likely response in trying to reclaim their losses.

It’s easy to raise the stakes in sequels. Just remember that the more your character wins in her victories, the more she then stands to lose in all subsequent battles.

4. How to Create a Seamless Overall Story

The best stories are those that create a seamless big picture. No matter how huge and sprawling your story will be by the time you write the final book, you still want your series’ ultimate ending to bring the story back full circle to the very first book. That can be tricky (especially if, like me, you didn’t know you were writing a series when you started Book 1).

The Best Way to Write a Seamless Series

Optimally, you will know your series’ ending before you ever begin writing Book 1’s first draft. This allows you to identify all the most important plot questions, characters, settings, thematic questions, and Maguffins. Once you’re aware of which are important throughout the series, you can then artfully sow them into each book in a meaningful way, allowing them to become consequential motifs—road marks along the way that characters and readers alike can resonate with.

Be careful not to abandon important elements in later books.

The Second Best Way to Write a Seamless Series

However, the above approach may not always be possible. Perhaps outlining just isn’t your thing, or perhaps, like me, you had to wait six years before you even realized there would be another book. In that case, you won’t be able to work your way up from the foundation of the story’s big picture. Instead, you will have to start on the ground floor, pick up whatever pieces seem important and then make sure they’re important all the way through to the end of the series.

For example, since Dreamlander was a standalone book, I basically had to cook up a whole new conflict for the sequels. And yet, I still wanted them to create the effect of a (generally) seamless overarching trilogy. This meant the new conflict I created for the sequels had to be built upon the leftover pieces of the first book. I had to figure out a way for Dreamlander‘s events to be, not so much a complete story unto themselves anymore, but rather the First Act in a larger story.

This pursuit of cohesion will be just as true of the smaller elements in your story. If certain settings, goals, or Maguffins were important in the first book, then you will want to find a way to, optimally, return to these elements in the second book—or, at the least, acknowledge them, so they don’t end up feeling like loose ends.

5. How to Continue Developing Minor Characters

If you want even the smallest elements of your story to play a role in creating a seamless big picture through your series (which you do), then this is doubly true of your supporting cast. In her email, Lauren went on to ask:

I’m finding myself trying to justify why many minor characters from the first book aren’t featured in the second one. They’re around somewhere, but just not that important for this plot!

Lauren’s dilemma was also one I faced in planning my sequels. I had some very new and exciting new roads down which to take my protagonists. But doing so required leaving behind some of the minor characters from the first book. Here’s what I discovered:

First rule of sequels: Yes, try to include as many elements as possible from the first book in the later books.

Second rule of sequels: Never force previous elements into a later book, just for the sake of cohesion.

So how can you meaningfully include old friends from Book 1, but in a way that matters to the story without interfering with that story? Here are four approaches:

1. Cameos

Although not ideal, you can still achieve the desired effect of tying off your loose ends simply by letting the minor character appear briefly in a very short scene. It lets readers know you didn’t forget about him, while also allowing you to acknowledge his whereabouts during the events of this book.

2. Frames

Even better than a one-time cameo appearance is a two-time “framing” appearance. Even if a minor character is extraneous to the main events of the plot, you can still keep her grounded within the story by giving her an appearance (or, even better, a job to do) in both the beginning and the end of your story.

3. New Roles

Often, a minor character might appear in Book 1 to fulfill a specific role, which then expires with that book. But the character himself needn’t expire. Just give him a new role. Tony Stark had no need of a bodyguard after he became Iron Man, so Happy Hogan instead became Pepper Potts’s driver in subsequent stories.

Everybody loves Happy, but as he acknowledged himself, he just didn’t have enough to do as Iron Man’s body guard in the sequels—so his role had to evolve.

4. Deaths

Finally, if you find yourself with an unnecessary character on your hands, you can always give them the chance to become necessary by letting them die a meaningful death. It’s win-win. You can stop juggling that extra piece, and you get a powerful scene that motivates surviving characters.

***

I had to write nine standalone books before I got to find out what a blast sequels are. Hopefully, you won’t have to wait quite so long. Sequels eliminate many of the challenges of a standalone book, but they also come with their own exciting new experiences to work through. Figuring out how to write a sequel can take your writing to the next level. Join me and see for yourself!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What do you think are the easiest and hardest parts of how to write a sequel? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/5-rules-of-how-to-write-a-sequel.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 5 Rules for How to Write a Sequel to Your Book appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

March 10, 2017

Free Webinar: How to Produce a Professional Audio Book

One of the fastest growing markets for writers is audio books. Like publishing a paperback or e-book, publishing a professional-quality audio book presents challenges of its own. In my experience (with four of my writing how-to books now available as audio books), this is far too lucrative a market to miss out on.

But how to tackle an audio book in a way that gives readers/listeners a quality product that does your book justice?

That was my quandary when I first looked into producing Outlining Your Novel as an audio book. I was also a veteran podcaster by then, so I figured maybe I could just go ahead and record my own. Cheapest, fastest way, right? Unfortunately, despite my podcasting experience, I quickly realized I didn’t have the technical chops to make it happen. (On the fortunate side, however, I was able to hire the amazing Sonja Field to narrate and produce it and all my audio books so far.)

I’m often asked why I haven’t yet released any of my fiction on audio, and the simple reason is that due to their larger size (and thus larger upfront production costs), I’ve never been confident enough to proceed with them—always wondering if they were something I could produce myself but still lacking the know-how.

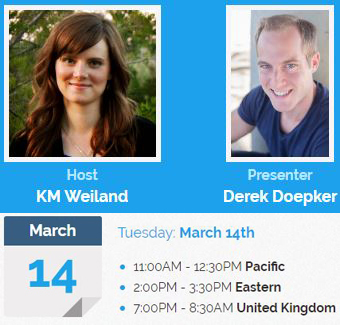

That was why I was so excited to discover Derek Doepker and the hands-on, accessible, and ultimately very easy-to-learn info he shares about recording, producing, and selling audio books. I’m always on the watch for other experts willing to share their expertise in areas I’m can’t share with you. I’ve learned a lot from Derek, and he’s given me a number of new perspectives and ideas about audio books—and even inspired me to finally start looking into producing one of my novels!

If you’re interested in branching out with your book sales and learning how to create and sell your own audio book, I hope you’ll join us for the FREE webinar “Audio Books for Every Author: 3 Ways to Turn Your Books Into Audio Books for More Royalties Every Single Month.” This 90-minute presentation, hosted by me and presented by Derek Doepker, will be live online next Tuesday, March 14th, 2017, at 2PM EDT.

This Webinar Will Show You…

How audio books are generating hundreds to thousands of extra dollars in royalties for some self-published authors.

How you can produce audio books on any budget and distribute them from anywhere in the world (even outside the U.S. and U.K.).

The critical facts you have to consider before deciding whether to outsource or produce your own audio books.

Where to hire professional audio-book narrators if you wish to outsource.

The exact microphone, software, and equipment you need to produce top-quality audio books on a shoestring budget.

Your audio-book questions answered personally by Derek (and me, where I’m able to).

The webinar platform limits the number of attendees, so be sure to sign up to reserve your spot in case of shortages.

The post Free Webinar: How to Produce a Professional Audio Book appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

March 6, 2017

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 57: Dead-End Relationships

Once upon a time there were two characters. They got along very well, cared for each other very much, always had good advice for one another, and always, always, always had each other’s back. The End.

Once upon a time there were two characters. They got along very well, cared for each other very much, always had good advice for one another, and always, always, always had each other’s back. The End.

Oh yeah, and even though it’s hardly worth mentioning, there was also this subplot character, who once betrayed one of the main characters, even though he loved her and even though he only did it because his conscience demanded he do it.

Main Character #1 (who we’ll say is a tough young woman orphaned in wartime) just happens to be haunted by this minor subplot character, thinks about him all book long, and is constantly talking about him to Main Character #2 (who we’ll say is a crusty old military buddy of her dad’s who has stepped in as a beloved father figure).

But… this is a subplot character, remember? So mostly that’s all they do: talk about him. What’s really important is this nice little relationship between tough orphan girl and her loving mentor.

Or is it?

Seriously, which of these relationships sound more interesting? We could even reverse the romance angle: the girl has a happy romantic relationship with her supportive husband, but she’s haunted by the father figure who betrayed her. Hmm, still looks like that intriguing little subplot relationship is way more interesting than the super-duper, happy-dappy ideal relationship on which this book keeps trying to focus all its attention.

So what does this mean? That your characters should never have healthy relationships? That healthy relationships are never going to be interesting to readers?

Certainly not.

But what it does mean is that if your story is trying to focus on a “dead-end relationship,” you may be missing out on some of your story’s best opportunities for entertaining readers and deepening themes.

What Is a Dead-End Relationship in a Story?

A dead-end relationship is one that doesn’t ask questions and doesn’t evolve over the course of the story. It’s static. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that, since not every relationship in a story needs to be dynamic. Most protagonists will require a support system of sorts (like our tough-girl hero and her Generalissimo father figure). These may be mentor or sidekick characters, who offer the protagonist feedback about her problems and advice about how to make forward progress through the plot.

You simply will not have space (either within the exploration of theme or the actual word count) to turn all of these relationships into something deeper. As a result, they will be comparatively shallow relationships. These characters probably won’t be following thematic arcs of their own, and they will exist primarily to provide contrast and direction as the protagonist navigates the choppy waters of more interesting relationships.

And right there, you can see the problem with dead-end relationships in a nutshell: however nice they may be, they’re simply not very interesting.

Why Dead-End Relationships Are Endangering Your Story

Relationships are the heart and soul of fiction. By no small coincidence, this is because relationships are the heart and soul of the human experience. Even for the most introverted among us, our lives are defined, limited, expanded, enriched, and endangered by all the other people bumping in and out of our spheres of existence. Even stories that focus on a protagonist’s relationship with himself are still stories that cannot escape the importance of other people’s influence upon that protagonist.

This means choosing the right relationships for your story is one of the most important decisions you will ever make.

Stories can feature multiple meaningful relationships, each an insightful commentary upon the others, in an ever-deepening web of thematic complexity. However, even the most complex stories will almost always focus on one primary relationship that crystallizes the thematic premise and catalyzes the protagonist’s personal growth.

This is the relationship that defines the story, and it must be chosen with care.

Think about it. Who is the primary relationship character in your work-in-progress? It might be a love interest, a parental figure, a best friend, even an antagonist.

Now consider what would happen if you shifted that focus to a different relationship character. It might make your story worse; it might make your story better; but, for certain, it would completely change your story.

If you inadvertently choose to focus on a dead-end relationship, you will inevitably weaken your entire story—your protagonist’s character arc, the potential of your premise, the purpose of your plot, and the persuasiveness of your theme.

5 Signs a Dead-End Relationship Is Dead-Weighting Your Story

So how do you know when you’ve accidentally bypassed your story’s juiciest options and instead chosen a hapless dead-end relationship? Here are five likely signs.

1. The Main Relationship Is Boring

This isn’t so much the cause, as it is the effect. But it’s the surest sign something has gone amiss somewhere along the line. The very nature of a dead-end relationship—static and without conflict—means it’s never going to do much of interest. It just sits there on the page, as the two main relationship characters perform a lot of purposeless rambling around, while talking a whole lot about a whole lot of nothing.

For Example:

Tough-girl Charlotte Magne was orphaned in the early days of World War II and grew up among the French Resistance, which was headed by her father’s crusty old buddy Beau N. Parte. She loves old Beau like an uncle, and despite his occasional grumpiness of manner, he loves her right back. She pines—against her better judgment—for the apparent traitor Lt. “Le Fou” Yette—and discusses it on a frequent basis with Beau, who does his best to tactfully advise her about what she should do if ever she meets poor Lt. Yette again.

2. The Main Relationship Isn’t Doing Anything

The main reason a dead-end relationship is boring is because it isn’t focused on forward progression within the plot. Because there’s no dynamism within the relationship, it has no forward momentum, no ability to affect the plot in itself, and precious little likelihood of being affected by the plot.

For Example:

Every once in a while, Charlotte and Beau will go out and skirmish with the enemy. He’ll give her a comforting pat on the shoulder. Maybe she’ll even dare to affectionately kiss that shiny bald spot atop his head. They’ll spend a couple scenes wondering together why Lt. Yette could have betrayed them, then a couple more sleeping and eating between skirmishes, then repeat.

3. The Main Relationship Doesn’t Ask a Question

The lack of dynamism in any relationship is usually because it asks no questions. For example, what a dead-end relationship does not do is ask questions such as:

Does he love me?

Can I trust her?

Why won’t he ever talk about his childhood?

Why does she always make me so spitting mad?

Why does he have to want something different from what I want?

The characters both feel they completely understand and can depend on the other. There are no mysteries here. There’s no need to figure out the other person—which means there’s no goal for either character within the relationship—which means there’s no conflict—which mean, so what?

For Example:

Charlotte understands good old Uncle Beau inside-out, just as he, in his taciturn way, understands her. Not much to think about there. They’re each quite comfortable in the knowledge that whatever may happen in the war, whatever that dastardly Lt. Yette may do next, they never have to worry about letting each other down.

4. The Main Relationship Doesn’t Change

In a dead-end relationship, everything is always great. The characters like each other, get along, and are confident that the relationship will continue to provide for them just as it has always done. They might (if readers are lucky) be working toward a common goal, but the goal, its obstacles, and the resultant conflict are entirely exterior. The relationship between these characters will be no different at the end of the story than it was at the beginning.

For Example:

Charlotte and Beau are a trusty team, fighting successfully alongside each other all book long, until… Lt. Yette shows up and (gasp!) kills Uncle Beau. Charlotte is heartbroken. She holds poor bleeding Beau in her arms while he gasps out, “I love you, my dear,” and then kicks the bucket. So, yeah, the exterior relationship did change, but aside from the fact that Charlotte is now really, really sad (and really, really mad at Lt. Yette), her relationship with Uncle Beau didn’t change a lick from beginning to end. There’s no irony in his dying words, no unfinished business between them to haunt her or inspire her to be a changed person in the aftermath.

5. The Main Relationship Character Is Static

It’s kind of a chicken/egg thing: the main relationship character in a dead-end relationship is static because the relationship is static, and the relationship is static because the character is static. Dead-end relationships are almost always an indication that your minor characters are little more than cardboard cutouts, there to serve the external plot and give your protagonist as yes-man to talk to. That, in turn, is probably a sign your protagonist herself is edging dangerously near to being a too-too precious Mary Sue, who is never challenged in her beliefs or actions by any of the supporting characters or external plot events.

For Example:

Old Beau is the quintessential soldier: gnarled, gruff, rough, tough, blustery, but with a heart of gold under it all. That’s who he was back when he took his old war buddy’s poor orphaned daughter under his wing, and that’s who he’ll be to the day he dies. He brought Charlotte up to be his best soldier, and most of his advice for her these days is gruff praise for her accomplishments and bland admonishments that Lt. Yette never really deserved her anyway. She humbly demurs now and then, but, mostly, she believes him.

5 Questions to Discover the Most Dynamic Relationship in Your Story

By now, I hope you are well and properly scared of featuring a dead-relationship too prominently in your story. But how can you make sure you’ve chosen the most dynamic duo for your story’s main relationship?

Start by answering these five questions.

1. Which Minor Character Do You Like the Most?

Most of the time, the right relationship character will present himself upfront. For me, my initial story ideas are almost always the result of two characters appearing center-stage in my imagination and starting a conversation. But in the event you’re not sure which of your awesome characters to choose, consider which you like the most. Which character will you enjoy spending the most time with? Which relationship dynamic will be the most fun to explore?

But be careful: You might find yourself in love with the idea of the relationship more than the unique and individual character himself. For example, it’s far too easy to write a vapid love interest and believe he’s loverly just because he’s Prince Charming. Good characters are always much more than the role they play.

2. Which Minor Character Is Interesting Enough to Be a Protagonist in Her Own Right?

Whenever you have a minor character so fascinating it’s all you can do to keep her from taking over as protagonist in her own right, you can be pretty sure you’ve got a wonderfully dynamic character on your hands. This is the kind of character who has ideas and goals of her own and will never be content to simply nod and smile for your protagonist’s benefit. This is the kind of character who will create interesting relationships because she’s already interesting in her own right.

3. Which Minor Character Is the Best Contrast/Mirror of Your Protagonist?

Supporting characters exist to deepen your story’s thematic argument. Even at their most individualistic and realistic, they are fundamentally archetypal symbols, representing the different facets of your protagonist’s journey via your theme.

The main relationship character is the most important influence upon your protagonist’s arc, which means you need to choose a character who is either a strong contrast and/or a mirror of who your protagonist was, is, and/or is becoming. When placed face to face with your protagonist, which of your supporting characters will inspire the deepest and most interesting questions about your theme?

4. Which Minor Character Will Create Conflict and Growth?

Do not choose a main relationship character whose chief function is to agree with your protagonist and tell him how wonderful he is. Even if the main relationship is a loving one, it should not be a fundamentally affirming one. You want to choose a relationship character who will create conflict and, as a result, inspire painful but necessary growth in your protagonist—and who, in turn, will probably also experience reciprocal growth as well.

This is relational dynamism. This is the kind of relationship that will not only be interesting in its own right, but which will forcefully and meaningfully impact your external plot.

5. Which Minor Character Is On-Stage the Most?

Finally, you will usually want to choose a relationship character who will be physically present and able to interact with your protagonist for most of the story. The Lt. Yette character from our examples may indeed have been a more interesting character than the well-meaning but flat Uncle Beau, but he never shared the stage with Charlotte until the very end. A relationship that is only talked about can’t drive your story, however interesting it may be in its own right.

***

Avoiding dead-end relationships will help you identify and eliminate countless other potential story killers—not least among them a dull plot, a lack of meaningful conflict, insipid characters, and flat themes. If you can take full advantage of your story’s main relationship, you will be that much closer to taking full advantage of the story itself.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How does your story’s main relationship character make your story (and your protagonist) that much more interesting? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/mistake-57.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 57: Dead-End Relationships appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

March 3, 2017

It’s Here! Creating Character Arcs Audio Book

It’s my pleasure to announce, to all of you who have been waiting for it, that the Creating Character Arcs audio book is now available, narrated once again by the amazing Sonja Field.

I’ve had this unabridged audio version in the works ever since the paperback and e-book versions of Creating Character Arcs came out last winter—which apparently was a good thing, since “when is the audio book coming out?!” has become one of the most common questions I’ve received of late!

You can grab it off Amazon for $17.95 (or just $1.99 if you already own the Kindle version), and if you’re not an Audible member yet you can even grab it for free by signing up!

About the Audio Book

Powerful Character Arcs Create Powerful Stories

Have you written a story with an exciting concept and interesting characters—but it just isn’t grabbing the attention of readers or agents? It’s time to look deeper into the story beats that create realistic and compelling character arcs. Learn how to achieve memorable and moving character arcs in every book you write.

By applying the foundation of the Three-Act Story Structure and then delving even deeper into the psychology of realistic and dynamic human change, this beat-by-beat checklist of character arc guidelines flexes to fit any type of story.

This comprehensive book will teach you:

How to determine which arc—positive, negative, or flat—is right for your character.

Why you should NEVER pit plot against character. Instead, learn how to blend story structure and character development.

How to recognize and avoid the worst pitfalls of writing novels without character arcs.

How to hack the secret to using overarching character arcs to create amazing trilogies and series.

And much more!

Gaining an understanding of how to write character arcs is a game-changing moment in any author’s pursuit of the craft.

Bring your characters to unforgettable and realistic life—and take your stories from good to great!

The post It’s Here! Creating Character Arcs Audio Book appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 27, 2017

The Lazy Author’s 6-Question Guide to Writing an Original Book

Never once have I worried that I might not be writing an original book.

Even just saying that kinda sounds like a dirty secret—like maybe the only kind of author who could say such a thing is either one who lacks anxiety enough to care if her stories are original and/or one who lacks integrity enough to check if her stories are original.

Granted, it is kind of a secret. But not a dirty one. Rather, it’s a completely liberating secret that lets me focus on doing my own thing without ever having to wonder if a story will have this so-called magic ingredient of “originality”—which we’re told so often is crucial for making agents swoon and readers buy.

So what is the secret?

Easy. Instead of focusing on what everyone else is doing, so I can avoid doing the same thing (leaving a very narrow window for creativity, indeed), I simply focus on doing my own thing.

Here’s how it works.

Forget Writing an Original Book: Seek Individuality

Honestly, the whole idea of writing an original book is soooo overrated. (Blasphemy, I know.) It isn’t that originality isn’t important or that it doesn’t often have that coveted effect of hypnotism on agents, editors, and readers. Rather, it’s that writing an original book is a product, not a process.

If you pursue originality, you may finally snag it in your butterfly net. But that may end up being the only thing in your net. Originality isn’t, in fact, so very hypnotizing by itself. Agent Russell Galen pointed out in the September 2016 Writer’s Digest article “Science Fiction and Fantasy Today”:

I’m interested in individuality, not originality for its own sake. If you have a vampire who drinks only the blood of octopuses, so what? I see a lot of stunt originality.

In short, individuality is the process that leads to originality. Stop worrying about writing an original book and start focusing on being “all of you” in everything you write. How do you that? Here are six important questions to get you started.

1. Do You Like This Idea?

This is where writing an original book begins. It’s also where that sound advice about “following your heart, not the market” gets its foundation. If you don’t genuinely like a story idea, then you’ve got no more business writing it than you would marrying someone you didn’t like.

This sounds like a no-brainer, but sometimes when authors end up overthinking the inspiration process, they actually can end up trying to write stories they’re not in love with. How does this happen?

Maybe you’re just desperate to break into bestseller status—so you figure you better jump on the latest trend, even though you actually have no interest in dystopia or angels or zombies or whatever.

Or maybe you’ve come up with a genuinely good idea. Logically, you know it might be a winner. But your heart just isn’t in it. This has happened to me a couple times with ideas that range from straight-up romance to police thrillers—neither of which I have the slightest interest in writing. So the great ideas, sadly, must be relegated to the Mental Cabinet of Pretty But Neglected Curiosities.

For Example:

I always know when I’ve found an idea I genuinely like. The images that suddenly flood my mind are ones that excite me. They’re ones I wish I could read about or watch on the big screen right now. This is a story I would pay to experience if another author were executing it. Lucky for me, I get to be that author!

2. Are You Passionate About This Idea?

“Of course, I’m passionate about it! I just told you I liked this idea, didn’t I?”

Yeppers, but even just liking an idea isn’t enough to imbue it with the life force that may eventually spawn true originality. You’re gonna marry this sucker, remember? That means you’ve got to be able to give it everything you’ve got.

When you’re asking yourself if you’re “passionate” about a story idea, what you really want to be asking yourself is if this idea is one capable of becoming a vessel for the fundamental passions that already drive your life. As John Dufresne wrote in The Lie That Tells a Truth:

When you’re asking yourself if you’re “passionate” about a story idea, what you really want to be asking yourself is if this idea is one capable of becoming a vessel for the fundamental passions that already drive your life. As John Dufresne wrote in The Lie That Tells a Truth:

You don’t waste your time or the reader’s by writing about what is not of crucial importance in your life.

These passions might be:

Causes you’re invested in

Credos you live by

Topics, people, and places that attract you

Theories that fascinate you

This is where we find the beating heart of the oft-maligned writing advice “write what you know.” This doesn’t mean you have to write about a whale biologist just because that’s what you do in real life or—more likely—write about a writer who stares at the blank screen, does laundry, goes shopping, and reads books. What it does mean is that stories should always reflect what you care about.

Why write about war in Afghanistan when your heart is really in education for the underprivileged? Why write about Paris when your heart is really in Skagway? Why write about forensic science when your heart is really into stormchasing?

Don’t try to cram popular, accepted, or intellectual ideas into your story just because they’re popular, accepted, or intellectual. Write what interests you. Your enthusiasm will be contagious.

For Example:

One of my chief rules of thumb in fleshing out my own ideas is “if bores me, fuhgeddaboutit.” Try it. It’s completely liberating! This rule makes it almost effortless to follow my passions in my writing. They pop up without much conscious thought at all. I write stories of redemption because I’m passionate about them. I write about ideas of honor and sacrifice because they fascinate me. I write about knights and pilots and history and epic fantasy because I love that stuff.

3. Do You Understand This Idea?

The first two questions on our list are really just about opening yourself to your subconscious and taking advantage of the great stuff you find already living there. But now, it’s time to get a little more conscious.

It’s not enough to have a good idea or even an honest idea. You also need to (at some point in the process) understand that idea. W.H. Auden said:

Some writers confuse authenticity, which they ought always to aim at, with originality, which they should never bother about.

The vast majority of truly great premises are wasted because their authors failed to understand their ideas well enough to take full advantage of them.

I’ve done whole posts on this important topic, but suffice it that once an idea has begun to gel for you, you must take it out, hold it up to the light, and turn it around to see it from every angle. Ask yourself:

What is this story really about–on the level of plot, theme, and character?

What kind of scenes do you need to create to take full advantage of all the best aspects?

What are the aspects of this type of story that have never or rarely been fully explored?

What can you and your unique life experience bring to this story?

Don’t just dance on the surface of a great idea. Follow it down the rabbit hole as far as you can possibly go.

For Example:

One of my favorite parts of the outlining process is sitting down at the very beginning to brainstorm “what if?” questions. I consciously explore every answer I can dig up in response to the questions “what will readers expect from this story?” and “what won’t they expect?”

4. Are You Doing This Idea Justice?

Sometimes it can be ridiculously tempting to add something to a story just because it seems like every story of this type has that something: heroes with amazing skills / funny little sidekicks / love-story subplots / you name it.

But to truly do justice to the individuality of your ideas, you must be able to distance yourself from the often reflexive urge to include genre tropes just because. Most of us do this at least once or twice per story without even really thinking about it.

Or maybe you do think about it: “Hmm, I better add this, or readers will be disappointed!”

Perhaps surprisingly, that’s not a good reason to include something in a story. Readers care far less about genre tropes than they do a cohesive story that follows its own rules and delivers its own satisfying surprises.

Hand-in-hand with the above exercise of mining your idea for its every unique and interesting aspect, you also need to be questioning every element you find yourself adding. Are you adding it just because it seems appropriate? Or are you adding because it’s true to the needs of this story?

For Example:

This is a trap I have to constantly guard against. Even when I attempt to be consciously aware of all my story choices, often I end up throwing in something here or there that really isn’t an honest reflection of the characters or story world I’ve created. I rely on my beta readers to point out where I’ve tossed in a trope or cliché for no good reason. Inevitably, I stand back and realize I was subconsciously including this element just to please a shallow genre convention.

5. Why Is This Idea Something Only You Can Write?

This is a question authors are frequently encouraged to ask themselves, and, yeah, I know it’s confusing as all get-out. “An idea only you can write”–what’s that supposed to mean anyway? Are you the only person who can write about dragons? Well, err, no. Are you the only person who can write a love story between a spoiled society queen and a grumpy detective? Uhhhhh, nooo. Are you the only person who can write about bewildered teens searching for the big answers? Sigh.

Those stories have already been written a gabillion times. Guess that means we’re all doomed to either pack it up and call it a day or just resign ourselves to writing the same old hackneyed stories. Or… not.

What “write something only you can write” really means is write your story as only you can write it. Put your own spin on it, your own style.

Try this. Think of five of your favorite authors. Then imagine how your story would be if they wrote it. No doubt all of their iterations would be awesome (you have excellent taste in authors, after all). But they would all be different. Yours will be different too. Don’t try to write your story as another author might write it. Write it to the fullness of your own unique capabilities and style.

For Example:

Patrick O’Brian, author of the highly stylistic Aubrey/Maturin series, is probably my all-time favorite author. I adore Dickens’s lush and cutting verbosity. I am fascinated by Patrick Rothfuss’s rambling exploration of his mysterious protagonist’s life. The painful, poetic, dreamy prose of Milena McGraw’s After Dunkirk makes me a little more than jealous every time I read it. But I am not these authors. Were I to try to be, my stories would inevitably suffer. Instead, I focus my energy on pouring my best sensibility and ability into each word I choose.

6. How Is This Idea an Introduction to You the Author?

One of the scariest thing about good writing is its total vulnerability. There is no place to hide on the page. Your deepest, rawest, most subconscious self is out there for the whole world to see. In fact, they may even end up seeing you more clearly than you see yourself.

And that’s exactly what you want. If you’re being dishonest or trying to hide yourself on the page, readers will always sense your disingenuousness and they will fail to engage. Readers come into a story wanting to know and understand your characters down their very souls. What that really means is that they’ve come to know you. Agent Russell Galen went on to insist one of the things he looks for first in a story is the sense that he is getting to know the author herself through her writing:

If so I will want to represent it, even if it’s about taking a ring to be destroyed or some cliché like that. Tropes go in and out of fashion. Just write the stories you want to write. If you are writing about authentic characters, we (agents, then editors, then readers) will care.

For Example:

Possibly my all-time favorite comment I’ve ever received about my writing was from a review of my portal fantasy Dreamlander on Amazon. The reviewer made an observation that initially blew me away. She said:

The consistent theme in each of her books is finding the best in human relationships and coming to an understanding about who you are and what you believe.

It blew me away because I never consciously put any of that into my stories, and yet these are themes I pursue passionately every day. They are the epicenter of my most primal questions. They represent some of the fundamental values of my own life. Whether she knew or not, what this reader had found in my stories was me.

You can’t manufacture originality. But you can strive to be your most vulnerable, honest, principled, and unique self. When you do that, you will write powerful stories. And the awesome thing about about powerful stories is that they have a way of finding their own originality.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What do you feel is your biggest challenge to writing an original book? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/writing-an-original-story.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post The Lazy Author’s 6-Question Guide to Writing an Original Book appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 24, 2017

Great Gift for Writers! Meraki Writers Subscription Box

I love subscription boxes. They come in the mail once a month, full of fun little goodies you might never have even heard of otherwise, much less purchased for yourself.

I love subscription boxes. They come in the mail once a month, full of fun little goodies you might never have even heard of otherwise, much less purchased for yourself.

That’s why I was excited to have the opportunity to review the Meraki Box from Alicia Jones, who curates this customizable, affordable, and highly giftable subscription box for writers.

What Is a Meraki Box?

Meraki means to do something with soul, with creativity; to put something of yourself into your work. There could not be a better description of what writers, authors, and editors do. Every word is written with love, with passion, with hope. Our boxes are designed to encourage and inspire literary artists.

Every Meraki box comes with four to five literary items, with the option of adding specialized items of chocolate, coffee, or tea.

What Was in My Meraki Box?

And now for the best part of any subscription box: opening and discovering what you’ve got!

Mine included:

Here’s a look at all the goodies I found inside my Meraki box.

Cute pencil and fun notebook.

Assorted literary goodies included an adhesive library pocket, a magnetic bookmark, and “desktop essentials.”

A stylish writing pendant.

Pumpkin spice coffee (mug and spoon not included—those are mine).

The box comes with a stylish gold ribbon (which I didn’t get a picture of, since I was too eager to get into it). It’s a fun and very nicely priced item (just $10-$15 per box) that would make a great gift for writers on your list, as well as a bright spot in your own month.

Check it out right here!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What do you think makes an inexpensive great gift for writers? Tell me in the comments!

The post Great Gift for Writers! Meraki Writers Subscription Box appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 20, 2017

Learn How to Pace Your Story (and Mind-Control Your Readers) in Just 8 Steps

Writing is really all about mind control. Seriously, think about it. You put words on paper, and if you do it right, you suddenly have the ability to control how people respond to what you’ve written. Of course, “doing it right” is the whole challenge of writing, and when it comes to this mind-control gig, the one thing you must do is learn how to pace your story.

Writing is really all about mind control. Seriously, think about it. You put words on paper, and if you do it right, you suddenly have the ability to control how people respond to what you’ve written. Of course, “doing it right” is the whole challenge of writing, and when it comes to this mind-control gig, the one thing you must do is learn how to pace your story.

At first glance, the whole subject of figuring out how to learn how to pace your story seems to be about just two things:

1. Make the story go faster. (At which point, all literary writers stop reading).

2. Make the story go slower. (At which point, all genre writers stop reading.)

True enough, that’s the basics of pacing. But the benefits go far beyond just speeding up and slowing down your story. Writers who are in control of their pacing are writers who are in control of their stories. And writers who are in control of their stories are writers who are in control of their readers (*cue eerie Twilight Zone music here*).

4 Ways to Speed Up Your Story’s Pacing

As most modern genre writers know, fast pacing is an important factor in grabbing readers’ wandering attention, sucking them into the story, and keeping them racing through the pages to find out what’s gonna happen.

Swift pacing allows you to inject a sense of urgency into your character’s actions. It ensures something interesting is happening on every page and that the dead weight must be cut.

Even more useful, however, is the psychological effect fast pacing has on your readers. Even just the simple pacing trick of shortening your chapters or scenes can be enough to suck readers into reading “just one more”—and before they know it, they’re blearily finishing the final chapter only a couple hours before they have to get up for work (*cue evil chuckle here*).

In the hands of a skilled author, fast pacing can even have a physiological effect on readers, speeding up their hearts and tapping their adrenaline. There are certain scenes in certain books I can read over and over again—and my heart rate kicks up every single time.

Here’s another mind-control secret: adrenaline is addictive! Readers love it. Get them hooked on it and they’ll come back for more, even when it means another sleepless night.

So how can you learn to pace your story in a slightly speedier way? Here are four technically sound approaches.

1. Reduce the Number of Characters

A big cast has the ability to add complexity and depth to every facet of your story, but it will also inevitably bulk it up and slow it down. The more characters you must keep track of in any given scene, the bigger, longer, and slower your book is going to be.

Nothing wrong with that. But if you’re looking for a way to speed things up, consider your cast, both as a whole and in any particularly problematic scenes. Can you cut or combine characters to streamline things? In her article “Power Tools,” in the January 2016 Writer’s Digest, Elizabeth Sims suggested:

If your pace, overall, feels too slow, try eliminating your least important character (or maybe even a few of them). This will force you to cobble together and condense action and other characters, and will provide an added benefit: The remaining characters will stand out all the more.

2. Minimize Sequel Scenes

When structuring scenes, you will want to divide each one into two parts: scene (action) and sequel (reaction). It doesn’t take a quantum physicist to figure out that the sequel is the slower half. It’s where the characters slow down and think about things.

Consider the classic scene in Little Women, in which Jo refuses Laurie’s proposal. That’s the action—new stuff happening, characters opposing each other, and the relationship dynamic changing.

Then, in the sequel, Jo sits around crying and trying to figure out where she can go to escape for a while.

Let’s suppose (quite erroneously, of course) that this sequel scene just wasn’t working. It was slowing everything down and gumming up the works. Readers were getting bored and trying to skip ahead to get to Professor Bhaer. What should you do?

Chop it. (*cue gasps of horror*)

Surely not, though? Surely, you can’t just go around eliminating a vital part of scene structure like the sequel?!

Actually, you can. But you’re right to be cautious. Scene structure works for a reason: because the reaction segment acts as a counterpoint to the action, creating realism in the chain of cause and effect. Just as importantly, the sequel is a tremendously important integer in pacing your novel. Skip too many of them and you’ll end up with a headlong novel that doesn’t develop characters and very possibly doesn’t make any sense.

However, that doesn’t mean you’re chained to every single sequel. You can occasionally remove one or use only a very short transition sentence or paragraph to bridge the gap between action scenes, allowing you to keep the story’s pace racing along.

3. Add a “Ticking Clock”

One of the easiest ways to amp your story’s pacing is simply to shorten the timeline. Instead of allowing your story to take place over a leisurely six months, why not cut it to a fast six weeks—or even six days?

Even better, add a “ticking clock”—a deadline your character must reach in order to avoid dreadful consequences. Consider even a story so simple as Beauty and the Beast. This isn’t a particularly fast-paced story, but it keeps the tension high and the viewers focused via the Beast’s wilting rose. If he can’t earn Belle’s love before the last petal falls, all is doomed.

By creating a clear goal line for the story’s finale, you allow readers to subconsciously estimate how close they’re getting to the finish—and the closer they get, the faster the pacing will seem.

4. Raise the Stakes

What do the stakes have to do with pacing? Isn’t that another technique entirely?

Yes and no.

Yes, it’s a technique in its own right. But it is also a tremendous aid when you’re trying to learn how to pace your story. The higher the stakes, the more readers will care about what happens to your characters if they fail to reach their goals. Once you get readers to invest their emotions that deeply, you will be able to pull them toward your story’s finish. Even when the story’s interior pacing isn’t extremely fast, the readers’ pacing will be, as they race toward the end to find out what happens.

4 Ways to Slow Your Story’s Pacing

That all sounds pretty good. After all that, why in heaven’s name would you want to slow your story’s pacing?

Good question, particularly since modern writing advice focuses almost exclusively on how to speed pacing. It’s hammered into writers’ heads that they better never let the story slow down or they’ll lose readers. So, with the best of intentions, they use the above techniques and do indeed end up with a fast-paced whirlwind of a novel.

By itself, however, fast pacing isn’t enough to create a good story or even to properly grip readers. To truly control your readers’ experience of your story in a way that pulls them in and invests them mentally and emotionally, you must be able to deftly balance both swift and slow pacing—sometimes all in the same chapter—in order to create exactly the right rhythm of tension and exploration within your story.

Here are four approaches you absolutely must know how to use to slow your pacing.

1. Complicate Your Sentence Structure

One of the easiest way to control your pacing—either fast or slow—is to purposefully manipulate your sentence length and structure. Short, rapid-fire sentences lend themselves to a speedy pace—like the rat-a-tat of a machine gun or the increasing heart rate of characters and readers alike. Conversely, if you wish to slow your pacing, you can lengthen sentences, adding clauses to create a leisurely or dreamy literary landscape.

Consider the famous opening of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca:

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. It seemed to me I stood by the iron gate leading to the drive, and for a while I could not enter, for the way was barred to me. There was a padlock and a chain upon the gate. I called in my dream to the lodge-keeper, and had no answer, and peering closer through the rusted spokes of the gate I saw that the lodge was uninhabited.

The steady rhythm of sentences—short, long, short, long—keeps the prose interesting and varied, while still creating a slowly haunting build-up of tension.

You can then add to this the technique of deliberately complicating even simple sentences, which forces readers to slow down ever so slightly and think about them. For example, this lyric from Bright Eyes’s “Lua”:

What is simple in the moonlight by morning never is.

2. Skew the Scene:Sequel Ratio Toward Sequel

Just as chopping sequels from your scene structure allows you to speed up your pacing, you can achieve the opposite affect by chopping scenes.

Whaaaat?! (*cue more hysterical horror*)

If chopping sequels seemed blasphemous, certainly this sacrilege is all the more so.

And, yes, it’s certainly not something you want to try at home without your helmet and safety goggles. After all, your scenes are your story. If you cut too many, leaving only reactionary sequels, you’ll end up with the literary equivalent of a spineless sloth (with apologies to Sid).

That said, you may occasionally find a scene you can abbreviate or delete, allowing you to simply summarize its events in the subsequent sequel. What you’ll get are long, introspective scenes in which the characters do little other than wander around and think.

Assuming your prose is so brilliant readers don’t care what your characters do, you may be able to get away with this for short periods, in which you can hunker down in the shelter of your words, slow the pace to create gravitas, and really focus on exploring your characters.

Kathryn Magendie’s short story “Girls on Fire” uses this technique almost exclusively, creating a dreamy effect that purposefully distances readers from the narrative. It works here both because the story is short and because the author knew exactly what she was trying to achieve.

Kathryn Magendie’s short story “Girls on Fire” uses this technique almost exclusively, creating a dreamy effect that purposefully distances readers from the narrative. It works here both because the story is short and because the author knew exactly what she was trying to achieve.

3. Add More Internal Narrative

The vast majority of a story’s interiority and narrative will be found in the sequel scenes. So it only makes sense that beefing up your narrative is a great technique, in itself, for slowing your pacing.

If you’re one of those authors who starts getting a scared, sick feeling whenever people talk about how novels these days need to be fast, fast, fast—then this especially good for you. All of those great character-driven scenes we love so much in books such as Ender’s Game and A Handmaid’s Tale and The Book Thief are the result of their author’s mastery of character-driven narrative. We get to sit in our favorite characters’ heads and just marinate.

This doesn’t mean these scenes don’t advance the story. To keep from boring readers with a lack of dimension or consequence, every word must still be chosen with purpose and care. But that means this is also where you get the chance to really practice your wordcraft. Throw those beautiful phrases onto the page, play with them, dance with your characters, dig deep into their souls.

Remember, however, that these scenes do slow the pace and must be used in harmony with other techniques.

4. Focus on Descriptive Details

Truly fast-paced novels don’t often stop to smell the roses, much less describe them. But if you feel like your story is needing a breather, an easy pacing trick is to slow down enough to thoroughly ground readers in the details of the setting.

Authors are often warned not to describe every little detail. But used with care (and beautiful prose, of course), the occasional lush description can be just the trick for easing the story into a steadier rhythm, while also pulling the double duty of providing sensual details to the readers’ imaginations.

***

In truth, just about every narrative trick you’ve ever heard of will play a role in helping you learn to pace your story. Mastering narrative, dialogue, and description are all stepping stones on the way to mastering pacing. In understanding how to use these eight important pacing tricks to get you started, you can begin your new career as a mind-control master. (*cue fingers to your temples*)

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What do you think is the most important thing to keep in mind as you learn how to pace your story? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/learn-how-to-pace-your-story-in-8-steps.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Learn How to Pace Your Story (and Mind-Control Your Readers) in Just 8 Steps appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 17, 2017

Lost at Sea Scavenger Hunt: Stop #8

Today, we’re going to do something just for fun! Welcome to the Lost at Sea Scavenger Hunt where we are helping the Kinsman people find a new home. If you’ve just found us, be sure to start the adventure at Stop #1, which is Jill Williamson’s blog.

Want to Win Prizes?

Want to win a Kindle? All you have to do is collect the clue words (see the bottom of the post) from all of the sites participating in the scavenger hunt. There will also be a second Kindle prize at the end, but to enter for that you’ll need to take a pop quiz, which will test your knowledge about all the fantasy settings featured in the hunt. So take your time and read each post carefully.

The main prizes in the hunt (and mine at the bottom of this post) are open to international entries. Individual author contests on the various sites, however, might have different rules, so please read the parameters on each site. You have until Sunday night, February 19, at midnight PST to finish.

If you need help, or get lost along the way, click here for assistance.

Good luck!

The Continuing Journey of Wilek and Trevn

Wilek and Trevn had never seen anything like the people with four arms in Denver. They left the area as soon as they could, making their way to the northeast. They caught sight of a strange craft in the sky. This was different from the noisy sky vehicles they’d seen in Redmond, PacNorth, and Denver. This one seemed to float. They followed it all the way to Stop #8, which is Schturming from K.M. Weiland’s dieselpunk adventure novel, Storming.

About Storming

Here’s a closer look at Storming:

In the high-flying, heady world of 1920s aviation, brash pilot Robert “Hitch” Hitchcock’s life does a barrel roll when a young woman in an old-fashioned ball gown falls from the clouds smack in front of his biplane. As fearless as she is peculiar, Jael immediately proves she’s game for just about anything, including wing-walking in his struggling airshow. In return for her help, she demands a ride back home . . . to the sky.

Hitch thinks she’s nuts—until he steers his plane into the midst of a bizarre storm and nearly crashes into a strange airship like none he’s ever run afoul of, an airship with the power to control the weather. Caught between a corrupt sheriff and dangerous new enemies from above, Hitch must take his last chance to gain forgiveness from his estranged family, deliver Jael safely home before she flies off with his freewheeling heart, and save his Nebraska hometown from storm-wielding sky pirates.

Cocky, funny, and full of heart, Storming is a jaunty historical/dieselpunk mash-up that combines rip-roaring steampunk adventure and small-town charm with the thrill of futuristic possibilities.

Wilek and Trevn liked this looks of this place much better than the last few stops! They decided to set up camp and explore a little more…

The Last Thing You’d Ever Think to Find in Nebraska…

Doesn’t get much more ordinary than the farm country of western Nebraska, does it? That’s what my barnstorming flyboy protagonist Hitch Hitchcock thought when he finally came back to his (and my!) hometown of Scottsbluff. He hightailed it out of there nearly ten years ago, running from a corrupt sheriff but mostly just running away—off into the wild blue yonder in the cockpit of a rattly Jenny biplane.

When Hitch comes back late in the summer of 1920, he thinks he knows exactly what to expect: some very angry family members, the same old boring small-town life, and one very big airshow competition that he should handily win. But, nope. Turns out, sleepy little Scottsbluff can beat just about anywhere when it comes to the unexpected.

Bodies start falling out of the clear blue sky, and one of them (who survives, obviously!) hornswaggles poor Hitch into helping her escape the “Groundsworld” and get back to her top-secret home in the sky, to which she refers in her very bad English only as “Schturming.”

What is Schturming? Ah well, that’s (kinda) a secret. But let’s just say that if you toss all the following into a leather pilot helmet, give it a good shake, and dump it out, what you get is Schturming:

A Victorian science experiment gone very awry for a very long time.

Antique cannons.

Ambitious sky pirates.

Weather machines.

A foreign language that sounds a lot like Russian.

To find out the truth, you can order Storming on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, or right here on my site !

Your Clue for This Stop!

Write down this clue: to

The next stop on our map is Stop #9, the spaceship Lepeus Delta, which you’ll find on Kyle Pratt’s blog .

Win a Paperback Copy of Storming!

Before you move on, I am giving away a copy of Storming to one lucky winner. To enter, use the Rafflecopter widget below. Thanks for visiting my blog. Enjoy the rest of the scavenger hunt!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What fictional setting would you most like to visit if you could? Tell me in the comments!

The post Lost at Sea Scavenger Hunt: Stop #8 appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 13, 2017

8 Ways to Troubleshoot a Scene–and 5 Ways Make It Fabulous

So there I was: sitting at my desk, notebook in front of me—and absolutely no words staring back at me. The problem? I knew what needed to happen in this scene, but now that the time had come to write it, it seemed flat as a roadkill raccoon. It was clearly time to troubleshoot a scene and give it a fixer-upper. But where to start?

So there I was: sitting at my desk, notebook in front of me—and absolutely no words staring back at me. The problem? I knew what needed to happen in this scene, but now that the time had come to write it, it seemed flat as a roadkill raccoon. It was clearly time to troubleshoot a scene and give it a fixer-upper. But where to start?

The single greatest challenge when trying to troubleshoot a scene is that the problem could be one (or more) of any dozens of issues. Sometimes, of course, you’ll sit down to write a scene without really knowing what it’s about, and you’ll end up rambling around, clearing your throat, and writing filler just to figure out what to write.

That’s a problem unto itself. Today, what I want to talk about is how to spice up scenes in which you know what events need to happen, but which you’re having trouble executing in an engaging way.

Do you have a scene in front of you that’s feeling:

Rote?

Boring?

Repetitious?

On-the-nose?

One-dimensional?

All of the above?

With a few simple brainstorming tricks, you can figure out how to troubleshoot a scene that’s giving you problems and turn it into one of the highlights of your entire manuscript.

How to Know When You Need to Troubleshoot a Scene

First off, let’s talk about how you can know when you need to troubleshoot a scene.

Most of the time, this is easy: the scene is driving you nuts.

It’s not working and you know it’s not working. You’ve played with it so much, you can’t stand the sight of it anymore, but you keep tweaking and fiddling without actually getting to the root of the issue.

Other times, a scene may feel like it’s working on almost every level but one. It works fine to power the plot forward and to accomplish the necessary effect you’re going for… and yet, something is off in one area or another.

For me, the single greatest litmus test for whether or not a scene is working is: Am I having fun writing this? If not, that’s almost always a sure sign I need to have a serious facedown with the blank page and figure out what important ingredient is missing.

Usually, it’s one of the following.

8 Common Problems When Trying to Troubleshoot a Scene

Here are eight of the most common problems I encounter when figuring out how to troubleshoot a scene. Inevitably, one or more of these is at the root of the issue. Once you identify it, you’re halfway to fixing it.

1. The Scene Is One-Dimensional

The troublesome scene I talked about in the opening paragraph was fundamentally problematic because it started out as a very one-dimensional scene. It was a scene late in the book, full of revelations about things I’d been hinting at for most of the plot. But now that the time had come to reveal them, I found myself staring at a chapter full of talking heads. There was no life, no zest, no movement, and no visual interest. Just three character sitting around gasping and going, “Uhhhhh, I understand everything now!!!” Riveting.

You can run into this problem in many different types of scene. Whether your scene is all talking, all sword-fighting, all to-being-or-not-to-being, or all kissing, chances are you’ve got a one-dimensional scene on your hands.

If the only thing happening in your scene is characters talking, consider adding another dimension.

2. The Scene Lacks Forward Momentum

Whenever I find myself stuck on a scene that’s going nowhere, the first thing I do is stop and ask myself, “What does the character want?” The POV character’s goal is the foundation of good scene structure. It’s what drives the plot forward, keeps things literally moving, and sets up the rest of the necessary structural interplay.

That was another problem I faced in my troublesome scene: what did the characters want here? What did they want other than to just sit around while the pieces clicked together for them? As soon as I engineered a goal, I instantly had a sense of forward momentum with the characters moving toward something, rather than just sitting around waiting for the revelations to hit.

3. The Scene Proceeds Unimpeded

After you’ve realized your character’s scene goal, the next step is to make sure his path to that goal isn’t unimpeded. Conflict—in the shape of an obstacle to that goal—spices up any scene. The character needs to go talk to someone else? Too simple. Stick in an obstacle. Perhaps someone else wants to talk to Character #2 too—and the protagonist doesn’t want Character #3 around to hear all these important revelations he was about to unload on Character #2.

Elements such as the need for secrecy can easily add new layers of conflict to any scene.

4. The Scene Lacks a Resolution

To truly move the plot, every scene must be cohesive unit unto itself. It must have a beginning, and it must have an end. If the characters don’t end the scene in a different space—mentally, if not physically—from the one in which they began the scene, then you can deduce one of two things about your scene:

Either:

1. The scene is completely nonessential to the plot and can be pulled.

Or:

2. The scene hasn’t ended yet.

The character’s relationship to her scene goal must change in some respect from the beginning of the scene. Either she conquers the obstacle and gets what she wants, or fails and is worse off than ever. Most often, she will encounter a “yes, but… disaster,” in which she may gain the scene goal only to encounter new complications that must be dealt with in the next scene.

5. The Scene Is Too Busy

As you’re concentrating on all this admirable work of spicing up your dull scene, you might find yourself slipping into the overcompensation of adding too much to your scene. One of legendary director John Ford’s guiding principles was that each scene should only try to accomplish one thing.

In other words, your scene should be about your character trying to discover that important missing clue—not about your character trying to discover that important missing clue while also playing matchmaker to his two hapless friends, while also learning he got a scholarship to Yale, while also learning his dad is mad at him for not gassing up the car the previous night.

This does not mean the scene needs to be simple. Even an extremely complex scene with many thematic layers and intersecting character goals should still have a clear and cohesive focus.

Director John Ford was a master of creating complex scenes with a clear focus, such as this one from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

6. The Scene Lacks Complexity

And that brings us to complexity itself. Just as a scene may suffer from being one-dimensional in focusing too stringently on one aspect—such as dialogue or action—it can also suffer from being too straightforward in its intent.

But didn’t you (and, more importantly, John Ford) just say to focus a scene on one thing?

One subject, yes—one goal for your POV character. But that doesn’t mean you should avoid complexity in your presentation of plot, theme, and character.

Even as your scene is a straight arrow toward its resolution, you want the entire rest of your story to be breathing and pulsing beneath the surface. The Apostle Paul wrote in Romans that:

For none of us liveth to himself, and no man dieth to himself.