7 Questions You Have About Scenes vs. Chapters

A chapter is a chapter and a scene is a scene. Or are they? What’s the differences between scenes vs. chapters? Are they ever the same thing? Must a chapter always be a complete scene? Or must a scene always be a chapter? What about scene breaks and chapter breaks? Is there a difference?

A chapter is a chapter and a scene is a scene. Or are they? What’s the differences between scenes vs. chapters? Are they ever the same thing? Must a chapter always be a complete scene? Or must a scene always be a chapter? What about scene breaks and chapter breaks? Is there a difference?

These are all questions I receive regularly from writers, and they’re all good questions with surprisingly simple answers.

The shortest and simplest answer to all of these questions is: yes, scenes and chapters are different, with very different structural roles to play within your story.

Let’s take a look at five important questions about scenes vs. chapters, which will help you better understand and control your narrative.

1. Why Do Authors Have Trouble Differentiating Scenes vs. Chapters?

First of all, let’s consider why scenes vs. chapters is even a big question at all.

Mostly, it’s because chapters are obvious and scenes aren’t. As writers, we all start out as readers, and to readers, the concept of chapters is very obvious, very visual. On its surface, a book seems to be divided into chapters, right? Scenes, then, are just smaller structural integers within the chapters.

But then, when you start learning about scene structure, you realize there’s actually a whole lot more to scenes than you thought—and a whole lot less to chapters. Nobody ever talks about “chapter structure” after all.

Turns out it’s the comparatively invisible scene that is the far more important structural unit within a story than is the obvious chapter. At first glance, that seems counter-intuitive, and that’s what trips writers up in understanding the unequal importance of scenes vs. chapters.

2. What’s the Difference Between Scenes vs. Chapters?

So what is the difference between scenes vs. chapters?

Scenes are very specific structural building blocks within your story. Each scene is made up of six distinct parts (see below), all of which are necessary in order for each scene to build into the following one to create a seamless narrative. Scene divisions are non-negotiable.

Chapters, on the other hand, are completely arbitrary divisions within a book. It’s true they do impose order upon a novel—and, as a result, a certain sense of structure. But, on the story level, they actually have nothing whatsoever to do with structure.

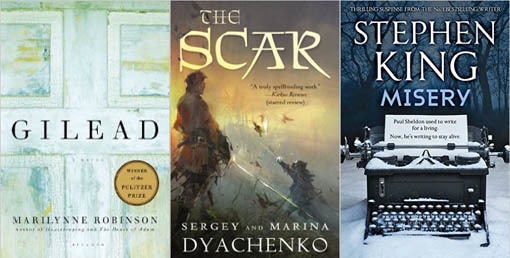

Chapter divisions are more about pacing than anything else. You might write a book with no chapter divisions (such as Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead) or a humongous fantasy novel with only nine chapters (such as Sergei and Marina Dyachenko’s The Scar) or one with chapters of only a single sentence (such as the notorious “Rinse” in Stephen King’s authorial nightmare Misery).

Chapters can be any length—from the entirety of the book to a single word.

In short, scenes are logical decisions; chapters are creative decisions.

3.What Must a Good Scene Accomplish?

For the moment, let us consider scenes and chapters separately to understand what each is responsible for accomplishing within your story.

Because scenes are ultimately much more complicated and much more important than chapters, they can be the more difficult of the two for writers to initially get their heads around. I’ve written extensively about scene structure in this series and in my book Structuring Your Novel, but here’s a crash course in good scene structure.

First off, remember scene structure has absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with chapter divisions. (More on that in a bit.) The scene is always a complete unit unto itself, regardless how long or short it turns out to be. What’s important in designing or identifying a scene is making sure the following six parts are all present.

We start by dividing each scene into two parts: scene (action) and sequel (reaction). We then further divide each of those halves into three more pieces each:

Scene

1. Goal (the protagonist or POV character sets out to accomplish or gain something).

2. Conflict (en route to his goal, his efforts are blocked by an obstacle of some type).

3. Disaster (the character’s attempt to gain his goal is at least partially stymied, forcing him to move forward on the diagonal, instead of rushing straight ahead through the plot).

Sequel

4. Reaction (the character must then react, however briefly or lengthily, to the previous disaster—this is where the vast majority of character development will take place).

5. Dilemma (as the result of the disaster, the character is confronted with a new complication or dilemma in his attempt to reach his main story goal).

6. Decision (the character comes to a decision about how best to act, prompting a new goal in the next scene).

And then the cycle endlessly repeats throughout the story.

Each scene is a domino. When set up correctly, scenes create a seamless line of cause and effect that almost effortlessly powers your entire plot.

4. What Must a Good Chapter Accomplish?

Good book chapters have two primary roles:

1. Chapters Control Pacing

Chapters create a sense of rhythm within the story. Depending on the length of each chapter, this rhythm will either speed or slow the pacing.

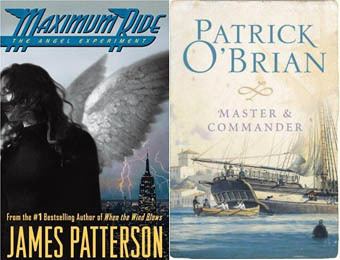

Shorter chapters create faster pacing—which is why thriller authors such as James Patterson often opt for hundreds of chapters, some of which are no longer than a page.

Longer chapters, in turn, slow the pacing. Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey/Maturin series recreates the leisurely, often charmingly indulgent style of early 19th-century literature. One of O’Brian’s more obvious techniques in achieving this pacing is his employment of very long chapters, some of which require an hour or more to read.

Shorter chapters are often used in thrillers to achieve faster pacing, while more leisurely books implement longer chapters to slow the pacing.

It’s true scene length also plays a role in pacing, but not to nearly the same extent as chapter length. Because chapters are much more obvious to readers (rather like commercial breaks in a TV show), they exercise much more blatant control over the reading experience.

2. Chapters Keep Readers Reading

The second role of the chapter is to create an experience that convinces readers to keep reading. Even to dedicated readers, books are undeniably a large time commitment. There’s never any guarantee readers will actually make it through your entire book—which means it falls to you to convince them to keep reading.

Chapters are the key to influencing readers into the proper mindset to continue turning pages. The control chapters exercise over pacing plays a role in this. Even more importantly, however, is the opportunity each chapter ending and beginning offers to hook readers back into the story.

Just as you have to hook readers with the beginning of the book, you have to re-hook them throughout the book. You’ll do this through reveals, scene disasters, and plot twists. But you’ll also do it twice within every chapter—at the beginning and at the end. Done skillfully enough, you might even convince readers to read straight through without ever putting the book down.

5. Does Every Scene Have to Be a Chapter?

Now that you understand the important differences between scenes vs. chapters, how do you fit the two of them together within the overall scheme of the narrative? Stephen King and James Patterson aside, is it ideal to divide the story into chapters based upon each scene’s structure? Should each complete scene be a chapter unto itself?

There is no “right” answer to this. Can a scene be a full chapter? Definitely. Does it have to be? Not at all.

Once again, the defining attributes of a scene have nothing to do with how many chapter breaks break it up. Depending on the needs of your story, the length of your scene, and your goals for the pacing, you may write a scene/sequel that spans multiple chapters.

6. Does Every Chapter Have to Be a Scene?

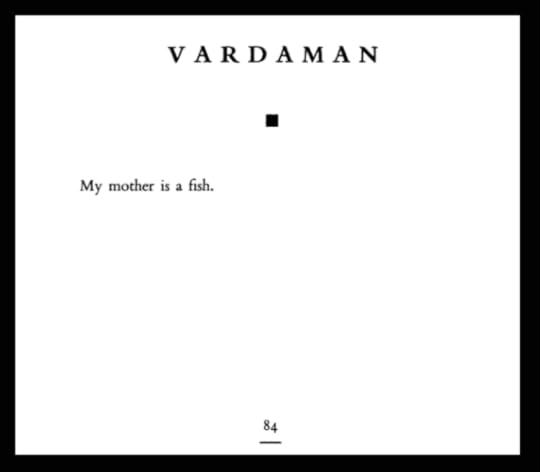

By the same token, not every chapter has to contain a whole scene. A chapter might contain nothing more than a single thought, as does William Faulkner’s one-sentence chapter in As I Lay Dying.

Or it might contain only a single part of a scene’s overall structure, such as, say, the character’s reaction to a previous disaster.

That said, my personal favorite approach to dividing scenes into chapters is to actually use the chapter break to divide the scene in half. I like to end chapters with the Scene Disaster, since it usually provides an excellent what’s-gonna-happen hook to keep readers reading.

This then allows me to open the following chapter with the Sequel Reaction, in which the characters respond to whatever just happened. I finish out that scene’s structure, then begin the next scene halfway through the chapter and end with another Scene Disaster.

The pattern I create looks like this:

Chapter

Sequel Reaction

Sequel Dilemma

Sequel Decision

[scene break]

Scene Goal

Scene Conflict

Scene Disaster

[chapter break]

This isn’t, of course, a hard-and-fast pattern. I’ll abandon it wherever necessary (such as when any part of the scene structure grows too long to be contained within the chapter length I’ve chosen for my story’s pacing). But it’s a good guideline for creating chapters that harmonize well with your scene structure and are primed to perform their most important job of hooking and re-hooking readers.

7. Are There Different Rules for Scene Breaks vs. Chapter Breaks?

Finally, let’s consider the difference between scene breaks and chapter breaks.

A chapter break indicates the end of one chapter and the beginning of the next.

A scene breaks indicates a shift of some sort within the middle of a chapter.

There are two types of scene breaks: hard and soft.

What Are Hard Scene Breaks?

Hard breaks are used to indicate a distinct shift within the story. This might include:

The beginning of a new structural scene unit.

The characters’ moving to a new setting.

A large jump forward in time.

A new POV narrator.

Hard breaks are usually indicated by a centered triplicate of asterisks or a short line in the middle of the page, between the paragraphs that needing splitting.

In my historical dieselpunk novel Storming, I used a hard scene break here to indicate a change in time and setting as the protagonist Hitch goes to visit his estranged brother.

What are Soft Scene Breaks?

Soft breaks are often as much as pacing trick as anything else. They serve to indicate a much smaller or less distinct shift within the story. This might include:

A minor or inconsequential shift in setting while the main action of the scene continues (e.g., the characters move from an office to the street, where they resume the same conversation).

A minor or inconsequential shift in time (e.g., “After they finished eating…”)

Soft breaks are usually indicated by only an extra space between the paragraphs that need splitting.

I used a soft scene break to skip a small amount of time as my barnstorming pilot protagonist figures out where to land his biplane after his engine dies.

What Are the Rules for Good Scene and Chapter Breaks?

As you can see, scene breaks occur at very specific moments within the story, while chapter breaks can occur just about anywhere you want them to. But the rules for executing both are the same.

Whenever you create a break of any type within your story, you must be aware of the potential for losing your readers’ focus. You combat this by creating solid hooks at each scene or chapter break.

The best way to think of a hook is simply as something that piques readers’ curiosity. Phrase the end of each chapter or scene in a way that creates even the smallest bit of dichotomy. Get readers to wrinkle their brows a little and ask themselves, What does that mean…? And, bang, you’ve got ’em! They’ll keep right on reading, regardless what kind of break they’re looking at.

***

My bet is you’re already instinctively using your chapters and scenes correctly. Don’t let the technical differences confuse you. Master them and claim them, so you can use and harmonize your scenes and chapters to create a seamless and hypnotizing reading experience.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What is your biggest challenge regarding scenes vs. chapters? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/7-questions-you-have-about-scenes-vs-chapters.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 7 Questions You Have About Scenes vs. Chapters appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.