Oxford University Press's Blog, page 826

April 7, 2014

10 things you didn’t know about Parkinson’s Disease

Did you know that 7-13 April is Parkinson’s Awareness Week 2014? To mark the occasion, here are 10 facts you might not have known about Parkinson’s Disease. Go on, improve your awareness!

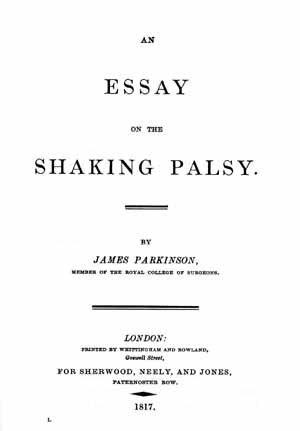

1. Parkinson’s Disease is named after British surgeon James Parkinson, who in 1817 wrote An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. Whilst Parkinson was the first to observe and describe the symptoms in a number of patients, it was actually Jean-Martin Charcot, a French neurologist, who would later coin the name ‘Parkinson’s Disease’.

1. Parkinson’s Disease is named after British surgeon James Parkinson, who in 1817 wrote An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. Whilst Parkinson was the first to observe and describe the symptoms in a number of patients, it was actually Jean-Martin Charcot, a French neurologist, who would later coin the name ‘Parkinson’s Disease’.

2. There is not yet a cure for Parkinson’s Disease, but there are very effective – almost miraculous – treatments for the symptoms. Of all the neurological disorders, Parkinson’s is one of the most treatable.

3. Symptoms are often on only one side of the body, or are asymmetric; this asymmetry persists throughout life.

4. Communication may be hindered by a softness of voice, decreased articulation, monotone speech, loss of normal inflection, and a decline in facial animation and expression.

5. Progression of Parkinson’s disease varies from person to person; it may be slow and in some cases may never lead to significant impairment.

6. There is no single laboratory test a doctor can order to confirm whether a person has Parkinson’s disease. There are, however, four “Cardinal Symptoms”, the combination of any two being enough for diagnosis:

(a) Resting tremor

(b) Bradykinesia (slowness of movement)

(c) Rigidity

(d) Postural Instability

7. While it is recognised that depression, apathy, and anxiety can be frequent “partners” of Parkinson’s, it is not uncommon for people to find inspiration and new meaning in their lives after their diagnosis.

8. Physicians may use the Hoehn and Yahr scale to report the degree of disease progression, and the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale to describe the severity of the symptoms and signs.

8. Physicians may use the Hoehn and Yahr scale to report the degree of disease progression, and the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale to describe the severity of the symptoms and signs.

9. Exposure to paraquat, a pesticide, triples a person’s risk of getting Parkinson’s Disease.

10. Loss of the sense of smell may be one of the earliest symptoms, sometimes preceding the onset of the disease by many years.

Charley James works in marketing for Oxford University Press. Her father’s experience of Parkinson’s Disease motivated her to write about the condition in support of Parkinson’s Awareness Week 2014. She wrote this blog with the help of Navigating Life with Parkinson’s Disease, The Parkinson’s Disease Treatment Book, and Parkinson’s Disease: Improving Patient Care.

Parkinson’s UK is the Parkinson’s Disease research and support charity. They bring people with Parkinson’s, their carers and families together via their network of local groups, their website and free confidential helpline. Specialist nurses, supporters and staff provide information and training on every aspect of Parkinson’s.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) James Parkinson’s 1817 work ‘An Essay on the Shaking Palsy’. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons; (2) Nose. Author information missing. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 10 things you didn’t know about Parkinson’s Disease appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPersecution in medicineDementia on the beachThe never-ending assault by microbes

Related StoriesPersecution in medicineDementia on the beachThe never-ending assault by microbes

Make the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting: pass H.R. 4085

By Edward Zelinsky

Telecommuting benefits employers, employees, and society at large. Telecommuting expands work opportunities for the disabled, for those who live far from major metropolitan areas, and for the parents of young children who value the ability to work at home. Telecommuting also removes cars from our crowded highways and enables employers to hire from a wider and more diverse pool of potential employees.

It is thus anomalous that New York State’s personal income tax discourages interstate telecommuting by taxing the compensation non-resident telecommuters earn on the days such telecommuters work at their out-of-state homes. Under the misleading label “convenience of the employer,” New York subjects telecommuters to double income taxation by their state of residence as well as by New York – even though New York provides non-resident telecommuters with no public services on the days such interstate telecommuters work at their out-of-state homes outside of New York’s borders.

Some of New York’s elected officials profess interest in making New York tax policy more rational and family-friendly. These officials, however, have shown no willingness to repeal the “convenience of the employer” rule to stop New York’s double state income taxation. Taxing non-resident, non-voters for public services they do not use is just too politically tempting for Albany to resist.

Fortunately, federal officials have begun to recognize the unfairness and irrationality of the double state income taxation inflicted on non-residents by New York’s “convenience of the employer” rule. Most recently, US Representative Jim Himes, joined by his House colleagues Elizabeth Esty and Rosa DeLauro, introduced H.R. 4085, The Multi-State Worker Tax Fairness Act of 2014.

Representative Himes, and his colleagues, are to be commended for introducing this much needed legislation. If enacted into law, H.R. 4085 would make the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting.

In previous incarnations, legislation along these lines was denominated as The Telecommuter Tax Fairness Act. The legislation’s goal remains the same. For Congress, using its authority under the commerce clause of the US Constitution, to forbid New York and other states from double taxing no-nresidents’ incomes on the days such non-residents work at their out-of-state homes.

Consider in this context the spate of service stoppages experienced by MetroNorth railroad commuters this winter. During these stoppages, public officials quite sensibly urged MetroNorth commuters to work from home rather than clog the already crowded highways to reach Manhattan. However, no public official spoke candidly about the tax penalty such commuters triggered by working at their Connecticut homes.

New York’s double taxation of non-resident telecommuters is not limited to those who live and work at home in the northeast. Under the banner of employer convenience, New York projects its taxing authority throughout the nation. In widely reported cases, New York imposed its personal income tax on Thomas L. Huckaby for days he worked at his home in Tennessee, on Manohar Kakar for days he worked at his home in Arizona, and on R. Michael Holt for days he worked at his home in Florida.

Nor is the threat of double taxation limited to New York’s personal income taxes imposed on non-resident telecommuters. Fortunately, many states recognize that double taxing non-resident telecommuters is ultimately self-destructive, driving telecommuters and the firms which employ them to states with more welcoming tax policies. However, other states emulate the Empire State’s tax hostility to interstate telecommuting. For example, Delaware taxed Dorothy A. Flynn’s income for the days she worked at her Pennsylvania home, even though Ms. Flynn did not set foot in Delaware on these work-at-home days.

The unfairness and inefficiency of the double state income taxation of interstate telecommuters has led a broad national coalition to favor federal legislation like H.R. 4085. Among those supporting such legislation are the American Legion, the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation, the National Taxpayers Union, The Small Business & Entrepreneurship Council, the Association for Commuter Transportation, The Military Spouse JD Network, and the Telework Coalition.

Representative Himes, along with Representatives Esty and DeLauro, are to be commended for introducing H.R. 4085. If enacted into law, this much needed legislation would make the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting by forbidding double state income taxation of non-resident telecommuters.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Metro-North EMD FL9 leaving Stamford, CT. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Make the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting: pass H.R. 4085 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesChallenges to the effectiveness of international lawIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?The Gaied Decision: a rare victory for tax sanity in New York

Related StoriesChallenges to the effectiveness of international lawIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?The Gaied Decision: a rare victory for tax sanity in New York

A brief history of ethnic violence in Rwanda and Africa’s Great Lakes region

A few years ago an American Catholic priest asked me about my dissertation research. When I told him I was studying the intersection of Catholicism, ethnicity, and violence in Rwandan history, he responded, “Those people have been killing each other for ages.”

Such is the common if misguided popular stereotype. But even the better informed are often unaware of the longer historical trajectories of violence in Rwanda and the broader Great Lakes region. Although the 1994 genocide in Rwanda has garnered the most scholarly and popular attention–and rightfully so–it did not emerge out of a vacuum. As the world commemorates the 20th anniversary of the genocide, it is important to locate this epochal humanitarian tragedy within a broader historical and regional perspective.

Northwestern Rwanda by CIAT. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

First, explicitly “ethnic” violence has a relatively recent history in Rwanda. Although precolonial Rwanda was by no means a utopian paradise, the worst political violence occurred in the midst of intra-elite dynastic struggles, such as the one that followed the death of Rwanda’s famous Mwami Rwabugiri in 1895. Even after the hardening of Hutu and Tutsi identities under the influence of German and Belgian colonial rule, there was no explicit Hutu-Tutsi violence throughout the first half of the 20th century.

This all changed in the late 1950s. As prospects for decolonization advanced, Hutu elites began to mobilize the Rwandan masses on the grounds of “Hutu” identity; Tutsi elites in turn encouraged a nationalist, pan-ethnic paradigm. The latter vision may have carried the day save for the sudden July 1959 death of Rwanda’s long-serving king, Mwami Mutara Rudahigwa. Mutara’s death opened up a political vacuum, emboldening extremists on all sides. After an escalating series of incidents in October 1959, a much larger wave of ethnic violence broke out in November 1959. Hutu mobs burned Tutsi homes across northern Rwanda, killing hundreds and forcing thousands from their homes. Scores of Hutu political leaders were killed in retaliatory attacks. Even here, however, motivations could be more complicated than an ethnic zero-sum game. For example, many Hutu militia leaders later claimed that they were defending Rwanda’s Tutsi king, Mwami Kigeli V, from a cabal of Tutsi chiefs. In other cases Hutu and Tutsi self-defense forces collaborated to defend their communities.

Supported by key figures in the Catholic hierarchy and the Belgian colonial administration, Hutu political leaders like Gregoire Kayibanda soon gained the upper hand in the political struggle that followed the November 1959 violence. In turn, political violence took on increasingly ethnic overtones during election cycles in 1960 and 1961; hundreds of mostly Tutsi civilians were killed in a series of local massacres between March 1960 and September 1961. Marginalized inside Rwanda, Tutsi exile leaders launched raids into Rwanda in early 1962, sparking further retaliatory violence against Tutsi civilians in the northern town of Byumba. For their part, European missionaries and colonial officials deplored the violence even as they blamed much of it on Tutsi exile militias, attributing the Hutu reactions to uncontrollable “popular anger.”

If these earlier episodes could be classified as “ethnic massacres,” a larger genocidal event unfolded in December 1963 and January 1964. Shortly before Christmas, a Tutsi exile militia invaded Rwanda from neighboring Burundi. The incursion was quickly repulsed by a combined force of Belgian and Rwandan army units. In the immediate aftermath, the Rwandan government launched a vicious repression of Tutsi opposition political leaders. In the weeks that followed, local government “self-defense” units executed upwards of 10,000 Tutsi civilians in the southern Rwandan province of Gikongoro. Vatican Radio among other media sources deplored “the worst genocide since World War II.” Local religious leaders like Archbishop André Perraudin stood by the government, however, calling the invoking of “genocide” language “deeply insulting for a Catholic head of state.”

Rwanda’s “ethnic syndrome” spread to neighboring Burundi during the 1960s. After a failed Hutu coup d’état in April-May 1972, Burundi’s Tutsi-dominated military launched a fierce repression known locally as the “ikiza” (“curse”). Over 200,000 mostly educated Hutu were killed that summer. In Rwanda, anti-Tutsi violence broke out in February 1973. Although the number of deaths was much lower than in 1963-64, hundreds of Tutsi elites were driven into exile as pogroms broke out at Rwanda’s national university, several Catholic seminaries, and a multitude of secondary schools and parishes.

Rwanda and Burundi were both dominated by one-party military dictatorships during the 1970s and 1980s. For some years each regime paid lip service to a pan-ethnic ideal. However, as economic and political conditions worsened in the late 1980s, ethnic violence flared again in 1988 in the northern Burundian provinces of Ntega and Marangara. In October 1990, the Tutsi-dominated Rwanda Patriotic Front invaded northern Rwanda, sparking a three-year civil war that profoundly destabilized Rwandan society. Following the pattern of the early 1960s, Hutu militias responded by targeting Tutsi civilians in six separate local massacres between October 1990 and February 1994. In turn, the October 1993 assassination of Melchior Ndadaye, Burundi’s first Hutu Prime Minister, sparked a massive outbreak of ethnic violence and civil war in Burundi that would ultimately take the lives of over half a million.

In turn, one should not forget the post-1994 violence that continued to plague the region. Not only did Rwanda suffer more massacres (some directed at Hutu) between 1995 and 1998, but Burundi’s civil war continued until 2006. Perhaps worst of all, Eastern Congo after 1996 became the epicenter of what many scholars have dubbed “Africa’s World War.” The precipitous cause of the conflict was Rwanda’s invasion of Congo in October 1996, ostensibly to clear Hutu refugee camps that were serving as staging grounds for cross-border raids into Rwanda. Upwards of four million Congolese died from war-related causes over the next six years. Over a decade later, Rwandan-backed militias continue to dominate Congo’s Kivu provinces. The “afterlife” of the Rwanda genocide thus continues even in 2014.

The 1994 genocide took the lives of an estimated 800,000 Rwandans, the vast majority of them Tutsi. This genocide–and the world’s utter abandonment of the Rwandan people–should never be forgotten. But nor should we overlook the political and ethnic violence that preceded and followed the genocide, whether in Rwanda, Burundi, or the Democratic Republic of the Congo. One can only hope that the next 20 years will be kinder to a region that has suffered so much over the past generation.

Find out more – read a further article by J. J. Carney on his book Rwanda Before the Genocide, including free access to “Contested Categories,” a chapter on Hutu and Tutsi categories.

J. J. Carney is Assistant Professor of Theology at Creighton University, Omaha, Nebraska. His research and teaching interests engage the theological and historical dimensions of the Catholic experience in modern Africa. He has published articles in African Ecclesial Review, Modern Theology, Journal of Religion in Africa, and Studies in World Christianity. He is author of Rwanda Before the Genocide: Catholic Politics and Ethnic Discourse in the Late Colonial Era.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A brief history of ethnic violence in Rwanda and Africa’s Great Lakes region appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTwo difficult roads from empireChallenges to the effectiveness of international lawPersecution in medicine

Related StoriesTwo difficult roads from empireChallenges to the effectiveness of international lawPersecution in medicine

Challenges to the effectiveness of international law

For the first time in its history, the American Society of International Law (ASIL) is partnering with the American Branch of the International Law Association (ILA) to combine each organization’s major conference into an extraordinary joint event. Oxford University Press is looking forward to exhibiting at the conference taking place in Washington on 7-12 April 2014. The conference theme is “The Effectiveness of International Law,” and no doubt there will be much to debate and discuss during the week. Organizers released a set of questions they hope will be addressed during the course of the conference. To kick off the debate we posed two of them to Ademola Abass, author of Complete International Law.

Are there greater challenges to effectiveness in some areas of international law practice than in others? If so, what are they, and how can they be addressed?

Keen followers of international affairs often wonder why, despite the prohibition on the use of force by the UN Charter, States still resort to this means of addressing international disputes. Explanations vary. Legal experts offer various technical explanations for this development. This includes that the rules governing the use of force are outdated and do not offer enough protection for States. Non-lawyers blame the ‘double-standard’ of international law which allows rich and powerful States to act with impunity while weak and poor States are held accountable for their conducts. Others blame the special status accorded to the five permanent members of the Security Council by the veto vote. Regardless of divergent viewpoints, all agree the prohibition of the use of force is less effective than other areas of international law. This is due principally to lack of compliance by some States, and lack of enforcement against rich and powerful States. It is also difficult for States not to defend themselves against threatening States until those have attacked them. The presence of nuclear weapons makes it difficult for most States to sit and wait for an attack before they respond. Overcoming these challenges requires making the Security Council work more evenly and responsibly; ensuring greater transparency and consistency in the administration of collective security by the United Nations. More importantly, it requires the interpretation of the law prohibiting the use of force in accordance with the reality of the twenty first century.

Do the challenges facing international law vary in different parts of the world, and, if so, how might those challenges be met?

It is often argued that international law began in the West. While one can contest whether it is possible (or purposeful) to seek locating the birthplace of international law, in contradistinction from its development, not many will argue that international law faces severe challenges in the developing world in contrast to the developed world. In the developing world, the first problem of international law is lack of its popularity. This arises through a combination of lack of awareness, of most law students, about the utility and relevance of international law to their societies. Secondly, the marketing of international institution and materials, has almost a Western bias: international institutions such as the United Nations, the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court (ICC), World Bank, are all located in the West. Most international law books report cases and jurisdictions that are preponderant Western as if cases and courts in developing countries make no contribution to international law development.

Addressing these challenges calls for a greater balancing acts in the citing and administration of international institutions; it requires a more even coverage of international law; it necessitates making international law more visible to developing countries, and making their contributions to international law more visible to the world. On their own, developing countries must do more to popularize international law in their academic curricula, expose their judges more greatly to international law, and afford international lawyers from the developing countries more opportunity in the dissemination and practice of international law.

Professor Ademola Abass joined the UNU Institute on Comparative Regional Integration Studies (UNU-CRIS) as a Research Fellow in Peace and Security in 2010. He is also the Head of Peace and Security Programme. He is a former Professor of International Law and Organisation at Brunel University, West London and was educated at the Universities of Lagos, Cambridge, and Nottingham. He holds a Ph.D. in International Law and has previously taught in several British universities. He is the author of Complete International Law.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The United Nations Security Council Chamber in New York. Photo by Patrick Gruban, 2006. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Challenges to the effectiveness of international law appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPreparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meetingIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?Is there a “cyber war” between Ukraine and Russia?

Related StoriesPreparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meetingIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?Is there a “cyber war” between Ukraine and Russia?

Two difficult roads from empire

Britain’s impending withdrawal from Afghanistan and France’s recent dispatch of troops to the troubled Central African Republic are but the latest indicators of a long-standing pattern. Since 1945 most British and French overseas security operations have taken place in places with current or past empire connections. Most of these actions occurred in the context of the contested end of imperial rule – or decolonization. Some were extraordinarily violent; others, far less so. Historians, investigative journalists and leading intellectuals, especially in France, have pointed to extra-judicial killing, systematic torture, mass internment and other abuses as evidence of just how dirty decolonization’s wars could be. Some have gone further, blaming the dismal human rights records of numerous post-colonial states on their former imperial rulers. Others have pinned responsibility on the nature of decolonization itself by suggesting that hasty, violent or shambolic colonial withdrawals left a power vacuum filled by one-party regimes hostile to democratic inclusion. Whatever their accuracy, the extent to which these accusations have altered French and British public engagement with their recent imperial past remains difficult to assess. The readiness of government and society in both countries to acknowledge the extent of colonial violence indicates a mixed record. In Britain, media interest in such events as the systematic torture of Mau Mau suspects in 1950s Kenya sits uncomfortably with the enduring image of the British imperial soldier as hot, bothered, but restrained. Recent Foreign and Commonwealth Office releases of tens of thousands of decolonization-related documents, apparently ‘lost’ hitherto, may present the opportunity for a more balanced evaluation of Britain’s colonial record.

In France, by contrast, the media furores and public debates have been more heated. In June 2000 Le Monde’s published the searing account by a young Algerian nationalist fighter, Louisette Ighilahriz, of her three months of physical, sexual and psychological torture at the hands of Jacques Massu’s 10th Parachutist Division in Algiers at the height of Algeria’s war of independence from France. Ighilahriz’s harrowing story helped trigger years of intense controversy over the need to acknowledge the wrongs of the Algerian War. After years in which difficult Algerian memories were either interiorized or swept under capacious official carpets, big questions were at last being asked. Should there be a formal state apology? Should decolonization feature in the school curriculum? Should the war’s victims be memorialized? If so, which victims? Although the soul-searching ran deep, official responses could still be troubling. On 5 December 2002 French President Jacques Chirac, himself a veteran of France’s bitterest colonial war, unveiled a national memorial to the Algerian conflict and the concurrent ‘Combats’ (using the word ‘war’ remained intensely problematic) in former French Morocco and Tunisia. France’s first computerized military monument, the names of some 23,000 French soldiers and Algerian auxiliaries who died fighting for France scrolled down vertical screens running the length of the memorial columns.

Paris monument to Algerian War dead: author’s own photograph.

No mention of the war’s Algerian victims, but at least a start. Yet, seven months later, on 5 July 2003, another unveiling took place. This one, in Marignane on Marseilles’ outer fringe, was less official to be sure. A plaque to four activists of the pro-empire terror group, the Organisation de l’Armée secrète (OAS), carries the inscription ‘fighters who fell so that French Algeria might live’. Among those commemorated were two of the most notorious members of the OAS. One was Roger Degueldre, leader of the ‘delta commandos’, who, among other killings, murdered six school inspectors in Algeria days before the war’s final ceasefire. The other was Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry, organizer of two near-miss assassination attempts on Charles de Gaulle, first President of France’s Fifth Republic. Equally troubling, it took the threat of an academic boycott in 2005 before France’s Council of State advised President Chirac to withdraw a planned stipulation that French schoolchildren must be taught the ‘positive role of the French colonial presence, notably in North Africa’.

One explanation for the intensity of these history wars is that few France and Britain’s colonial fights since the Second World War were definitively won or lost at identifiable places and times. The fall of the French fortress complex at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, the climax of an eight-year colonial war over Vietnam’s independence from France, was the exception, not the rule. Not surprisingly, its anniversary has been regularly celebrated by the Vietnamese Communist authorities since then.

Elsewhere it was harder for people to process victory or defeat as a specific event, as a clean break offering new beginnings, rather than as an inconclusive process that settled nothing. Officials in British Kenya reported that the Mau Mau rebellion, rooted among the colony’s Kikuyu majority, was ‘all but over’ by the end of 1955. Yet emergency rule continued almost five years more. To the East, in British Malaya, a larger and more long-standing Communist insurgency was in almost incessant retreat from 1952. Surrender terms were laid down in September 1955. Two years later British aircraft peppered the Malayan jungle, not with bombs but with thirty-four million leaflets offering an amnesty-for-surrender deal to the few hundred guerrillas who remained at large. Even so Malaya’s ‘Emergency’ was not finally lifted until 1960.

In the two decades that followed, the Cold War migrated ever southwards, acquiring a more strongly African and Asian dimension. The contest between liberal capitalism and diverse models of state socialism became a battle increasingly waged in regions adjusting to a post-colonial future. Some of the bitterest conflicts of the 1960s to the 1990s originated in fights for decolonization that morphed into intractable proxy wars in which civilians often counted amongst the principal victims. In the late twentieth century France and Britain avoided the worst of all this. Should we, then, celebrate the fact that most of the hard work of ending the British and French empires was done by the dawn of the 1960s? I would suggest otherwise. For every instance of violence avoided, there were instances of conflict chosen, even positively embraced. Often these choices were made in the light of lessons drawn from other places and other empires. Just as the errors made sometimes caused worst entanglements, so their original commission reflected entangled colonial pasts. Often messy, always interlocked, these histories remind us that Britain and France travelled their difficult roads from empire together.

Martin Thomas is Professor of Imperial History at the University of Exeter. This post is partially extracted from Fight or Flight: Britain, France, and their Roads from Empire

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Two difficult roads from empire appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineBritain, France, and their roads from empirePersecution in medicine

Related StoriesWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineBritain, France, and their roads from empirePersecution in medicine

April 6, 2014

Persecution in medicine

Recently I had the good fortune to see an excellent production of Bertolt Brecht’s play The Life of Galileo at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre. Brecht has a tenuous connection with the medical profession; he registered in 1917 to attend a medical course in Munich and found himself drafted into the army, serving in a military VD clinic for a short while before the end of the war. Brecht’s main interest, however, was drama (in 1918 he wrote his first play Baal) and it was in this field that he made his lasting contribution.

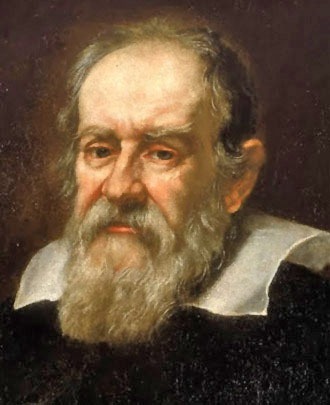

Galileo Galilei

Galileo was persecuted by the Church and the established authorities for his scientific research. His major crime was using his telescope to confirm the Copernican model of the Sun being at the centre of the solar system with the earth revolving around it. This challenged the cultural consensus and the leaders of the day were not prepared to listen to scientific evidence which challenged old dogmas. Galileo was interrogated in the Vatican, tortured, and forced to retract his theories.

The medical profession has also seen more than its fair share of persecution. I will illustrate with two examples in the relatively new speciality of radiology. The people concerned were not radiologists as such but were conducting pioneering research in imaging. Wilhelm Rötgen, the German physicist who first discovered x-rays in 1895, did himself meet relatively few obstacles regarding the dissemination of his thoughts and findings. But Werner Forssmann, a physician from the small town of Eberswalde in Germany, was not so lucky. In 1929, it is claimed, Forsmann performed the procedure of catheterisation of the heart upon himself and incurred the wrath of his boss as a result. He was sacked and had to switch from a career in cardiology to urology.

Forssmann was to have the last laugh a quarter century later when he shared the 1956 Nobel Prize for his contribution to cardiac catheterisation. This is now a commonplace procedure worldwide.

Werner Forssmann

The next case concerns the plight of Moses Swick, an American urology intern who went to Germany in 1928 to work with Professor Lichtenberg in Berlin. Swick performed scientific studies of a new intravenous contrast agent which would enable visualisation of the renal tract. He and Professor Lichtenberg fell out about who should be given the accolade for the discovery; Lichtenberg stole the limelight and was invited to talk about intravenous urography at the American Urological Association Scientific meeting. For 35 years Swick worked as an urologist in New York until in 1966 it was realised that he had been the victim of injustice and his role in the discovery was belatedly recognised.

These stories are examples where justice prevailed in the end. There are several others which did not and still do not realise fair outcomes.

Arpan K Banerjee qualified in medicine from St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School in London, UK and trained in Radiology at Westminster Hospital and Guys and St Thomas’s Hospital. In 2012 he was appointed Chairman of the British Society for the History of Radiology of which he is a founder member and council member. In 2011 he was appointed to the scientific programme committee of the Royal College Of Radiologists, London. He is the author/co-author of six books including the recent The History of Radiology. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Galileo, public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Wilhelm Röntgen, by NFejza, CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Werner Forssmann nobel, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Persecution in medicine appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDementia on the beachThe American Noah: neolithic superheroIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?

Related StoriesDementia on the beachThe American Noah: neolithic superheroIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?

Preparing for International Council for Commercial Arbitration 2014

By Rachel Holt and Jo Wojtkowski

Oxford University Press is excited to be attending the twenty-second International Council for Commercial Arbitration (ICCA) conference, to be held at the InterContinental Miami, Florida, on 6-9 April 2014. This year’s theme, “Legitimacy: Myths, Realities, Challenges” gives opportunity for practitioners, scholars and judges to explore the issues surrounding, what has been dubbed by some, the legitimacy crisis. To find out more take a look at this year’s exciting program devised by Lucy Reed and her team.

The four-day conference is packed with informative panel discussions, interactive breakout sessions, ICCA Interest Groups lunch meetings and networking events. With over 1,000 participants from around the world, highlights include “Legitimacy: Examined against Empirical Data” chaired by Jan Paulson, Holder of Michael Klein Distinguished Scholar Chair, University of Miami, and the opening session “Setting the Scene: What Are the Myths? What Are the Realities? What Are the Challenges?”, where Oxford author Eric Bergsten is to receive the ICCA Award for Lifelong Contribution to the Field of International Arbitration. Here are some of the conference events we’re excited about:

Monday 7 April, 12:15 -13:30p.m.: Latin America: The Hottest Issues, Country-by-Country

Lunch seminar chaired by Doak Bishop.

Monday 7 April, 13:45-15:00p.m.: Proof: A Plea for Precision

Proof is fundamental and can be maddeningly elusive. But must proof of fact and law so often be so imprecise? This session will explore the often fudged and occasionally ignored elements of burden of proof, the standard of proof, methods of proof to establish applicable law, and the importance of addressing these topics in a procedural order.

Monday 7 April, 15:30 – 16:45p.m.: Premise: Arbitral Institutions Can Do More To Further Legitimacy. True or False?

Have arbitral institutions been steady stewards of legitimacy in arbitration? Or, as more say, are they stagnant and protective of the status quo? In particular, can arbitration be legitimate if the arbitrator selection process is opaque, the quality of awards is variable, and the arbitral process lacks foreseeability? Particularly as the growth in regional institutions continues, are there consistent practices to be encouraged, and others to be eschewed, to promote and preserve legitimacy? This session will challenge whether institutions are doing enough to ensure the availability of diverse, well-trained arbitrators and to ensure first-rate, timely performance of their duties.

Tuesday, 8 April, 8:45 – 10:00p.m.: Matters of Evidence: Witness and Experts

Witness statements and expert reports tell the story, but whose story is it to be told? How rigorous are tribunals in “gating” witnesses? This session will explore the “do’s and don’ts” of drafting witness statements; whether the weight given to statements should vary and, if so, precisely why; and the impact of witness nonappearance on the admissibility and weight of testimony. It will also examine parallel questions for experts and expert reports.

Tuesday, 8 April, 13:45 – 15:00p.m.: ‘Treaty Arbitration: Pleading and Proof of Fraud and Comparable Forms of Abuse’

This session will explore and catalogue standards that govern the presentation and resolution of issues of fraud, abuse of rights, and similarly serious allegations that may impugn either a claim or the investment in treaty arbitrations. How do these issues arise? And how do tribunals address them? Is there a common understanding of pleading and proof standards for fraud, abuse of rights, or the bona fides of an investment? These are easy questions to ask, but precise answers are vexing.

Tuesday, 8 April, 12:15 -13:30p.m.: Spotlight on International Arbitration in Miami and the United States

A mock argument of BG Group PLC v. Argentina—the first investment treaty arbitration case to be heard by the US Supreme Court—will be one of the stops on a tour of international arbitration in Miami and the United States. Other stops will include Miami’s favorable arbitration climate, enforcement of arbitral awards in the United States generally and Florida specifically, arbitration class actions in the US, and an update on the Restatement (Third), The US Law of International Commercial Arbitration.

There is even a “Spotlight on International Arbitration in Miami and the United States” session which is not to be missed, but there is more to this amazing city than just arbitration. Located on the Atlantic coast in south-eastern Florida, Miami is a major centre and a leader in finance, commerce, culture, and international trade. In 2012, Miami was classified as an Alpha-World City in the World Cities Study Group’s inventory. In her upcoming title, Ethics in International Arbitration (publishing summer 2014), author Catherine Rogers argues:

“Ultimately, the challenge of ethical self-regulation is a challenge for the international arbitration community to think beyond its present situation, to future generations and future developments in an ever-more globalized legal world. It is a challenge for international arbitration to bring to bear all the pragmatism, creativity, and sense of the noble duty to transnational justice that it has demonstrated in the very best moments of its history.”

This comment highlights just one of the challenges facing arbitral legitimacy in the ever-growing world of international arbitration, which further highlights the importance of the ICCA’s chosen theme for the 2014 conference. If you are joining us in Miami, don’t forget to visit the Oxford University Press booth #16 where you can browse our award-winning books, and take advantage of the 20% conference discount. Plus, enter our prize draw to for a chance to win an iPad Mini, and pick up a free access password to our collection of online law resources including Investment Claims. See you in Miami!

Jo Wojtkowski is the Assistant Marketing Manager for Law at Oxford University Press. Rachel Holt is Assistant Commissioning Editor for Arbitration products at Oxford University Press.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in arbitration including the Journal of International Dispute Settlement, edited by Dr Thomas Schultz, and the ICSID Review edited by Meg Kinnear and Professor Campbell McLachlan, as well as the latest titles from experts in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from trademarks to patents, designs and copyrights, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Preparing for International Council for Commercial Arbitration 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPreparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meetingA doctrine of ‘market sovereignty’ to solve international law issues on the Internet?Is Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?

Related StoriesPreparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meetingA doctrine of ‘market sovereignty’ to solve international law issues on the Internet?Is Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?

Preparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meeting

By Jo Wojtkowski

This year’s joint ASIL/ILA Annual Meeting is of historic importance for the international law community. It is the first time that ASIL and the International Law Association (ILA) have joined forces to create a single combined conference of epic proportions. According to ASIL it is “expected to be one of the largest in international law history.”

ASIL’s 108th Annual Meeting and ILA’s 76th Biennial Conference will be held in Washington, DC, at the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, from 7-12 April 2014.

The 2014 conference theme is ‘The Effectiveness of International Law’, and participants will be tackling difficult questions such as: When, how, and why is international law most effective? Do the challenges facing international law vary across the globe? What role do non-state actors play in making international law more or less effective? Oxford Journals have pulled together a collection of articles from across our international law journals to tie-in with the theme.

More than 40 program sessions will address key topics across international law including the Approach of Courts to Foreign Affairs to National Security, Intelligence Material and the Courts, the Internet and International Law, Domestic Human Rights Enforcement after Kiobel, and even The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act’s Turn to International Law, to name but a few.

Here are some of the conference events we’re excited about:

Tuesday, April 8, 2014, 4:00-5:30 p.m.

Oxford Online Reception: Join us at the OUP Booth #1-3, for light cocktails, hors d’oeuvres, and scholarly conversation. Learn more about Oxford Online and receive two months of free access to our online law resources including Oxford Public International Law, Max Planck Encylopedia of Public International Law, Oxford Scholarly Authorities on International Law, Oxford Reports on International Law, and Oxford Constitutions of the World.

Wednesday, April 9, 2014, 5:00-6:30 p.m.

Grotius Lecture: Radhika Coomaraswamy, former UN Special Representative of the Secretary General on Children and Armed Conflict and on Violence against Women, will discuss women and children in international law.

Thursday, April 10, 2014, 12:30-2:15 p.m.

WILIG Luncheon: Women in International Law Interest Group will have remarks from Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, US Supreme Court (retired) and honorees include International Court of Justice Judges Julia Sebutinde, Joan Donoghue, and Xue Hanqin.

Thursday, April 10, 2014, 4:15-5:45 p.m.

Brower Lecture: Sundaresh Menon, Chief Justice of Singapore, will discuss international dispute resolution.

Friday, April 11, 2014, 12:30-2:15 p.m.

Hudson Medal Luncheon: Peter Tomka, International Court of Justice (Discussant, President) will speak with Hudson Medal Winner Alain Pellet, University Paris Ouest.

Friday, April 11, 2014, 4:15-5:45 p.m.

Friday Plenary: If you missed in WILIG Luncheon, catch ICJ Judges Julia Sebutinde, Joan Donoghue, and Hanqin Xue in conversation.

Friday, April 11, 2014, 8:00-10:00 p.m.

Gala Dinner: Join the luminaries of the international law community including Cherif Bassiouni (Butcher Medal) and the ASIL Certificate of Merit winners.

Don’t miss ILA’s 22 Committees and nine Working Groups, which include some of the top names in international law. We’re also thrilled to see so many of our authors among the speakers:

Kai Ambos, Professor of Criminal Law, Criminal Procedure, Comparative Law and International Criminal Law, Georg-August- Universitat Gottingen, and author of Treatise on International Criminal Law: Volume II: The Crimes and Sentencing

Laurence Boisson de Chazournes, Professor and Director of the Department of Public International Law and International Organization, Faculty of Law, at the University of Geneva, and author of Fresh Water in International Law

Curtis Bradley, William Van Alstyne Professor of Law at Duke University School of Law, and author of International Law in the U.S. Legal System

Jean d’Aspremont, Associate Professor of International Law, Amsterdam Center for International Law, University of Amsterdam, and author of Formalism and the Sources of International Law

Mark A. Drumbl , Alumni Professor at Washington & Lee University, School of Law, Director of the Transnational Law Institute, and author of Reimagining Child Soldiers in International Law and Policy

Jenny S. Martinez , Professor of Law and Justin M. Roach, Jr., Faculty Scholar at Stanford Law School, and author of The Slave Trade and the Origins of International Human Rights Law

André Nollkaemper, Professor of Public International Law, University of Amsterdam, and author of National Courts and the International Rule of Law

Georg Nolte, Professor of International Law at the Humboldt University in Berlin, and author of Treaties and Subsequent Practice

Jan Paulsson, head of the international arbitration practice of Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, and author of The Idea of Arbitration

Cesare Romano, Professor of Law, Loyola Law School, and editor of The Oxford Handbook of International Adjudication

Ben Saul, Professor of International Law at Sydney Law School, and co-author of The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Yuval Shany, Hersch Lauterpacht Chair in International Law at the Law Faculty of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and author of Assessing the Effectiveness of International Courts

Sandesh Sivakumaran, Associate Professor and Reader in Public International Law, School of Law, University of Nottingham, author of The Law of Non-International Armed Conflict , and editor of International Human Rights Law

If you are lucky enough to be joining us in DC, don’t forget to visit the Oxford University Press booth #1-3, where you can browse our award-winning books, and take advantage of the 35% conference discount. Stop by to enter our prize draw for a chance to win an iPad Mini, and pick up a free access passwords to our collection of online law resources, and featured Oxford journals.

To follow the latest updates about the ASIL-ILA joint meeting as it happens, follow us @OUPIntLaw, ASIL @asilorg, and use the hashtag #ASILILA14.

See you in DC!

Jo Wojtkowski is an Assistant Marketing Manager on the Law team at Oxford University Press USA.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Preparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meeting appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA doctrine of ‘market sovereignty’ to solve international law issues on the Internet?Is there a “cyber war” between Ukraine and Russia?An international law reading list for the situation in Crimea

Related StoriesA doctrine of ‘market sovereignty’ to solve international law issues on the Internet?Is there a “cyber war” between Ukraine and Russia?An international law reading list for the situation in Crimea

April 5, 2014

The American Noah: neolithic superhero

Reports suggest that Hollywood’s sudden interest in Bible movies is driven by economics. Comic book superheroes may be losing their luster and the studios can mine the Bible’s “action-packed material” without having to pay licensing fees to Marvel Entertainment. Maybe this explains why director Darren Aronofsky’s pitch to studio executives was not based on religious precursors, but the fact that Noah’s ark might be “the only boat more famous than the Titanic.” Did Paramount executives picture Titanic meets The Passion of the Christ?

Noah, first and foremost, follows the conventions of the Hollywood blockbuster. The studio is targeting not just churchgoers, but more importantly, the most frequent moviegoers (the under-25 crowd), and foreign audiences.

To heighten the film’s universal appeal, Aronofsky tried to meld the “fantastical world à la Middle-earth” for nonbelievers with a treatment that would please those “who take this very, very seriously as gospel.” The scorched earth magically sprouts a lush forest—lumber for ark-building—with Noah and his family helped by the Watchers, powerful earth-encrusted angels resembling Transformers. For the religiously devout, well, the movie “contains just enough spiritual pretention to make you wonder afterward if you have missed something important,” as Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson observes.

The film is “inspired by the story of Noah” with the Book of Genesis providing characters and setting. Noah is however more centrally shaped by American mythology, which is of course laced with Biblical motifs. In his classic study, R. W. B. Lewis describes the archetypal American as an Adamic figure, his innocence restored by virtue of having shed the baggage of history and ancestry. He is “an individual standing alone, self-reliant and self-propelling, ready to confront whatever awaited him with the aid of his own unique and inherent resources.”

Transplant this mythic character into Genesis and voilà! There you have it. The American Noah: Neolithic Superhero. Indeed, as Aronofsky said, “You’re going to see Russell Crowe as a superhero, a guy who has this incredibly difficult challenge put in front of him and has to overcome it.” Like the usual action-adventure lead (think of Crowe’s Maximus in Gladiator), Noah is stoic, fearless, determined, and not only capable of violence, but adroit in combat. Faith serves as Noah’s superpower with God providing some “magical outside assistance” that makes for amazing special effects (Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America). Forget the forty days and nights; in an SFX instant geysers erupt and the skies unleash a torrent of rainfall submerging the earth in the apocalyptic flood. Wow!

Logan Lerman and Russell Crowe in Noah. Source: noahmovie.com.

As expected, characterizations are stark and simplified. Conflict results from the different positions that characters embrace on two important Biblical themes.

The Biblical creation account is referred to variously in several scenes. The Creator of all that exists invests His image bearers with the care and cultivation of human life and the creation: “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground” (Gen. 1:28). Noah understands the Creator’s charge to have “dominion” in terms of creational caretaking. In contrast, his archenemy, the wicked Tubal-Cain, employs it as a divine license for exploitation of people and the creation.

There is much dialogue about whether human nature is basically good or evil. Noah’s wife Naameh stresses goodness as a counterbalance to Noah’s mounting pessimism. He believes he is chosen only because he would complete a task that is “much greater than our own desires.” Noah is convinced there is “wickedness in all of us” and that he and his family will eventually perish “like everyone else.” However, early on, one of the Watchers perceives “a glimmer of Adam” in Noah. This is more than a wistful allusion to pre-Fall innocence and foreshadows the anticipated payoff in the climax.

True to the blockbuster formula, the conflict peaks with a face-to face confrontation between Noah and his evil nemesis, but with a crosscutting twist that puts the fate of humankind in Noah’s hands (like all apocalyptic movies). The scene recalls Abraham’s test with his son Isaac (Genesis 22). At the decisive moment in Noah, however, it is not God’s intervention, but Noah’s “good” and better judgment that ultimately prevails. Such is the film’s deference to American self-reliance and the blockbuster formula that the ending is never in doubt. But let’s consider possible meanings of this crucial, if ambiguous scene.

Perhaps Noah is to be likened to the Creator, who punishes sin and remains faithful by preserving a remnant of humanity. Or maybe it’s just that Noah has seen enough devastation, which appears to have driven him (temporarily) mad, and now refuses to complete what he believes is his “mission.” The story is flawed here with Noah’s apparent—though plausible—confusion seeming contrived. The real effect of the scene is to elicit viewer empathy and admiration for the tried and true hero whose commendable faith turned dangerous. But Noah explains that when it came down to it he has “only love in his heart.” It’s a disappointing and obtuse cliché that I suppose is meant to be a comment by the narrator on both the divine and human nature. More than theological reflection, the line serves a thematic purpose: the American Noah’s autonomy and own integrity trump his trust in God.

Then again, this is an American-made blockbuster designed to attract the largest global audience possible. Among the trailers for Noah was Paramount’s next scheduled release, Transformers: Age of Extinction.

William Romanowski is Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences at Calvin College. His books include Eyes Wide Open: Looking for God in Popular Culture (a 2002 ECPA Gold Medallion Award Winner), Pop Culture Wars: Religion and the Role of Entertainment in America Life, and Reforming Hollywood: How American Protestants Fought for Freedom at the Movies. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The American Noah: neolithic superhero appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReflections on Son of GodIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?A question of consciousness

Related StoriesReflections on Son of GodIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?A question of consciousness

Word histories: conscious uncoupling

Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin (better known as an Oscar-winning actress and the Grammy-winning lead singer of Coldplay respectively) recently announced that they would be separating. While the news of any separation is sad, we can’t deny that the report also carried some linguistic interest. In the announcement, on Paltrow’s lifestyle site Goop, the pair described the end of their marriage as a “conscious uncoupling.” So … what does that mean?

The phrase was picked up by journalists, commentators, and tweeters around the world. Some called it pretentious, some thought it wise, others simply didn’t know what was going on. Let’s have a look into the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and see what we can learn about these words.

Conscious is perhaps the less controversial word of the pair. A look through the Oxford Thesaurus of English brings up adjectives like aware, deliberate, intentional, and considered. But did you know that the earliest recorded use of conscious related only to misdeeds? The OED currently dates the word to 1573, with the definition “having awareness of one’s own wrongdoing, affected by a feeling of guilt.” This sense is now confined to literary contexts, but it was only a few decades before the general sense “having knowledge or awareness; able to perceive or experience something” became common. The idea of it being used as an adjective referring to a deliberate action came later, in 1726, according to the OED’s current research.

Portrait of Geoffrey Chaucer by Thomas Hoccleve in the Regiment of Princes

The verb uncouple has an intriguing history. The current earliest evidence in the OED dates to the early fourteenth century, where it means “to release (dogs) from being fastened together in couples; to set free for the chase.” Interestingly, this is found earlier than its opposite (“to tie or fasten (dogs) together in pairs”), currently dated to c.1400 in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. In c.1386, in the hands of Chaucer and “The Monk’s Tale,” uncouple is given a figurative use:

He maked hym so konnyng and so sowple

That longe tyme it was er tirannye

Or any vice dorste on hym vncowple.

The wider meaning “to unfasten, disconnect, detach” arrives in the early sixteenth century, and that is where things rested for some centuries.

The twentieth century saw another couple of uncouples – one of which is applicable to the Paltrow-Martins, and one of which refers to a very different field. In 1948, a biochemical use is first recorded – which the OED defines “to separate the processes of (phosphorylation) from those of oxidation.” But six years earlier, an American Thesaurus of Slang includes the word as a synonym for “to divorce,” and this forms the earliest example found in the OED sense defined as “to separate at the end of a relationship.” Other instances of uncouple meaning “to split up” can be found in a 1977 Washington Post article and one from the Boston Globe in 1989.

So, despite all the attention given to the term “conscious uncoupling,” people have been uncoupling in exactly the same way as Gwyneth and Chris – and using the same word – since at least 1942. So perhaps not quite as controversial as some commentators suggested.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Simon Thomas blogs at Stuck-in-a-Book.co.uk.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Word histories: conscious uncoupling appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?Etymology as a professionCan the Académie française stop the rise of Anglicisms in French?

Related StoriesHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?Etymology as a professionCan the Académie française stop the rise of Anglicisms in French?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers