Oxford University Press's Blog, page 825

April 9, 2014

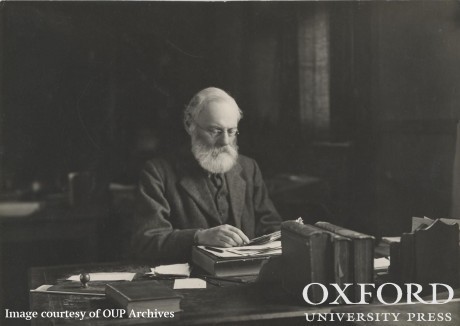

Unsung heroes of English etymology: Henry Bradley (1845-1923)

At one time I intended to write a series of posts about the scholars who made significant contributions to English etymology but whose names are little known to the general public. Not that any etymologists can vie with politicians, actors, or athletes when it comes to funding and fame, but some of them wrote books and dictionaries and for a while stayed in the public eye. Ernest Weekley authored not only an etymological dictionary (a full and a concise version) but also multiple books on English words that were read and praised widely in the twenties and thirties of the twentieth century. Walter Skeat dominated the etymological scene for decades, and his “Concise Dictionary” graced many a desk on both sides of the Atlantic. James Murray attained glory as the editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. (Curiously, for a long time people, at least in England, used to say that words should be looked up “in Murray,” as we now say “in Skeat” or “in Webster.” Not a trace of this usage is left. “Murray” yielded to the anonymous NED [New English Dictionary] and then to OED, with or without the definite article).

Those tireless researchers deserved the recognition they had. But there also were people who formed a circle of correspondents united by their devotion to some journal: Athenaeum, The Academy, and their likes. Most typically, the same subscribers used to send letters to Notes and Queries year in, year out. As a rule, they are only names to me and probably to most of our contemporaries, but the members of that “club” often knew one another or at least knew who the writers were, and being visible in Notes and Queries amounted to a thin slice of international fame. Having run (for the sake of my bibliography of English etymology) through the entire set of that periodical twice, I learned to appreciate the correspondents’ dedication to scholarship and their erudition. I learned a good deal about their way of life, their libraries, and their antiquarian interests, but not enough to write an entertaining essay devoted to any one of them. That is why my series died after the first effort, a post on Dr. Frank Chance (Dr. means “medical doctor” here), and I still hope that one day Oxford University Press will publish a collection of his excellent short articles on English and French subjects.

To be sure, Henry Bradley is not an obscure figure, but even in his lifetime he was never in the limelight. And yet for many years he was second in command at the OED and, when Murray died, replaced him as NO. 1. In principle, the OED, conceived as a historical dictionary, did not have to provide etymologies. But the Philological Society always wanted origins to be part of the entries. Hensleigh Wedgwood was at one time considered as a prospective Etymologist-in-Chief, but it soon became clear that he would not do: his blind commitment to onomatopoeia and indifference to the latest achievements of historical linguistics disqualified him almost by definition despite his diligence and ingenuity. Skeat may not have aspired for that role. In any case, James Murray decided to do the work himself. That he turned out to be such an astute etymologist was a piece of luck.

Beginning with 1884, Bradley became an active participant in the dictionary. According to Bridges, in January 1888 he sent in the first instalment of his independent editing (531 slips). In the same year he was acknowledged as Joint Editor, responsible for his own sections, in 1896 he moved to Oxford, and from 1915, after the death of Murray in July of that year, he served as Senior Editor. In 1928 Clarendon Press published The Collected Papers of Henry Bradley, With a Memoir by Robert Bridges, and it is from this memoir that I have all the dates. About the move to Oxford, Bridges wrote: “He definitely entered into bondage and sold himself to slave henceforth for the Dictionary.” (How many people still remember the poetry of Robert Bridges?)

James Murray was a jealous man. He might have preferred to go on without a senior assistant, but even he was unable to do all the editing alone. It could not be predicted that Bradley would trace the history of words, inherited and borrowed, so extremely well. Once again luck was on the side of the great dictionary. In 1923, when Bradley died, not much was left to do. Even today, despite a mass of new information, the appearance of indispensable dictionaries and databases (to say nothing of the wonders of technology), as well as the publication of countless works on archeology, every branch of Indo-European, and the structure of the protolanguage and proto-society, the original etymologies in the OED more often than not need revision rather than refutation. This fact testifies to Murray’s and Bradley’s talent and to the reliability of the method they used.

Bradley joined the ictionary after Murray read his review of the first installments of the OED (The Academy, February 16, pp. 105-106, and March 1, pp. 141-142; I am grateful to the OED’s Peter Gilliver for checking and correcting the chronology). Bridges wrote about that review: “…its immediate publication revealed to Dr. Murray a critic who could give him points.” But today, 140 years later, one wonders what impressed Murray so much in Bradley’s remarks and what points “the critic” could give him. Bradley did not conceal his admiration for what he had seen, suggested a few corrections, and expressed the hope that “the work [would] be carried to its conclusion in a manner worthy of this brilliant commencement.” It can be doubted that Murray melted at the sight of the compliments: with two exceptions, everybody praised the first fascicles, and those who did not wrote mean-spirited reports. More probably, he sensed in Bradley someone who had a thorough understanding of his ideas and a knowledgeable potential ally (Bradley’s pre-1883 articles were neither numerous nor earth shattering). If such was the case, he guessed well.

Finding word origins was only one small (even if the trickiest) part of the editors’ duties, but my subject is limited to this single aspect of their activities. The title of Bradley’s posthumous volume, The Collected Papers, should not be mistaken for The Complete Works. Nor was such a full collection needed, though some omissions cause regret. Like Murray, Bradley wrote many short notes (especially often to The Academy, of which long before his move to Oxford he was editor for a year). My database contains sixty-five titles under his name. Here are some of them: “Two Mistakes in Littré’s French Dictionary,” “Obscure Words in Middle English,” “The Etymology of the Word god,” “Dialect and Etymology” (the latter in the Transactions of the Yorkshire Dialect Society; Bradley was born in Manchester, so not in Yorkshire), numerous reviews and equally numerous reports, some of whose titles evoke today unexpected associations, as, for example, “F-words in NED” (the secretive year of 1896, when the F-word could not be included!).

Bradley had edited and revised the only full Middle English dictionary then in use. The modest reference to “obscure words” gives no idea of how well he knew that language. And among The Collected Papers the reader will find, among others, his contributions on Beowulf and “slang” to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, ten essays on place names (one of his favorite subjects), and a whole section of literary studies. Those deal with Old and Middle English, and in several cases his opinion became definitive. Bradley’s tone was usually firm (he made no bones about disagreeing with his colleagues) but courteous. Although he sometimes chose to pity an indefensible opinion, the vituperative spirit of nineteenth-century British journalism did not rub off on him. Nor was he loath to admit that his conclusions might be wrong. Temperamentally, he must have been the very opposite of Murray.

One of Bradley’s papers is of special interest to us, and it was perhaps the most influential one he ever wrote. It deals with the chances of reforming English spelling. I will devote a post to it next week.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of OUP Archives.

The post Unsung heroes of English etymology: Henry Bradley (1845-1923) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEtymology as a professionMonthly etymology gleanings for March 2014Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4

Related StoriesEtymology as a professionMonthly etymology gleanings for March 2014Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4

Pagán’s planarians: the extraordinary world of flatworms

The earth is filled with many types of worms, and the term “planarian” can represent a variety of worms within this diverse bunch of organisms. The slideshow below highlights fun facts about planarians from Oné Pagán’s book, The First Brain: The Neuroscience of Planarians, and provides a glimpse of why scientists like Pagán study these fascinating creatures.

Planarian Taxonomy

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In taxonomic terms, planarians belong to a large class of organisms called Vermes, the Latin term for “worm.” Platyhelminthes, or “flatworms,” represent a phylum within the class of Vermes, though the Platyhelminthes are broken down into four additional categories. One of these categories includes the Turbellarians—flatworms that are free-living and non-parasitic. Turbellarians are then arbitrarily distinguished based on their size, creating two further divisions: the microturbellarians (worms that are shorter than 1 mm) and macroturbellarians (worms that are longer than 1 mm). There are two types of macroturbellarians, the triclads and polyclads. Though “planarian” is a general term used to describe many types of flatworms, it is most often used in reference to triclads.

Planarian Size

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Triclads are small worms. They do not typically exceed one inch in length, but many of these worms are even smaller than that. Though these planarians can usually be seen with the naked eye, they are often studied under a microscope for closer observation. The two distinctive bumps that you can see on both sides of a planarian’s head, even without a microscope, are called auricles. Though they are commonly mistaken for ears, auricles do not pick up sounds in the environment, and instead contain many chemoreceptors that help planarians sense both nourishing and toxic substances in their surrounding environment.

Planarian Fossilization

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Planarians are an ancient species. But like other invertebrates, it’s hard for planarians to fossilize because their bodies lack hard bones. Planarians’ tendency to autolyze—or dissolve head first—when they die makes the process of fossilization even more difficult. Though the fossil record for these organisms is a bit scarce, scientists have identified a fully intact turbellarian fossil from the Eocene period about 40 million years ago. Scientists have also found what they interpret as fossilized flatworm tracks from the Permian period (300 million years ago).

Planarian Regeneration

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Planarians possess the incredible capability to regenerate cells that are damaged or removed. Though the scope of regeneration varies from species to species, many planarians are capable of full regeneration. This means that if you chop up a planarian into several pieces—the current record is 279 sections—each piece can regenerate into a full grown worm, assuming that this piece of the worm is placed in an environment with adequate nourishment. Even the isolated tip of a tail from a planarian can develop into a full grown worm that possesses a brain and central nervous system.

Planarians as Model Organisms

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In the early 20th century, scientists began looking for organisms with which they could test the principles of Mendelian genetics. Most people are aware that fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) became a common test subject because of their short lifespans and ability to produce large quantities of offspring in a short period of time. However, planarians also became a great model organism for scientists to use. Though the planarian nervous system is simple, these flatworms display an immense array of complex behaviors—making planarians an ideal candidate with which scientists can study how the brains of more complex organisms, such as humans, function.

Planarians in Popular Culture

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Planarians are not only test subjects for scientists to study. These are also creatures of popular culture, making appearances in several movies and TV shows. For example, in an episode of Fringe, Dr. Bishop offers Agent Dunham a smoothie with chopped pieces of planarians—a gesture meant to pay homage to the memory transfer experiments conducted by McConnell. Planarians have also appeared in the first movie of the Twilight saga, in addition to episodes of The Big Bang Theory and Dr. Who.

Oné R. Pagán is a Professor of Biology at West Chester University of Pennsylvania, and the author of The First Brain: The Neuroscience of Planarians.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images: The first five photos in this slideshow have been used courtesy of Dr. Masaharu Kawakatsu. Photo six is copyrighted (2003) by the National Academy of Sciences, USA and has been used with permission.

The post Pagán’s planarians: the extraordinary world of flatworms appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDementia on the beachDopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brainVoluntary movement shown in complete paralysis

Related StoriesDementia on the beachDopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brainVoluntary movement shown in complete paralysis

The political economy of skills and inequality

Inequality has been on the rise in all the advanced democracies in the past three or four decades; in some cases dramatically. Economists already know a great deal about the proximate causes. In the influential work by Goldin and Katz on “The Race between Education and Technology”, for example, the authors demonstrate that the rate of “skill-biased technological change” — which is economist speak for changes that disproportionately increase the demand for skilled labor — has far outpaced the supply of skilled workers in the US since the 1980s. This rising gap, however, is not due to an acceleration of technological change, but rather to a slowdown in the supply of skilled workers. Most importantly, a cross-national comparison reveals that other countries have continued to expand the supply of skills, i.e. the trend towards rising inequality is less pronounced in these cases.

The narrow focus of economists on the proximate causes is not sufficient, however, to fully understand the dynamic of rising inequality and its political and institutional foundations. In particular, skill formation regimes and cross-country differences in collective wage bargaining influence the quantity and quality of skills and hence also differences in inequality. Generally speaking, countries with coordinated wage-setting and highly developed vocational education and training (VET) systems respond more effectively to technology-induced changes in demand than systems without such training systems.

Yet, there is a great deal of variance in the extent to which this is true, and one needs to be attentive to the broader organization of political institutions and social relations to explain this variance. One of the recurrent themes is the growing socioeconomic differentiation of educational opportunity. Countries with a significant private financing of education, for example, induce high-income groups to opt out of the public system and into high-quality but exclusive private education. As they do, some public institutions try to compete by raising tuition and fees, and with middle- and upper-middle classes footing more of the bill for their own children’s education, support for tax-financed public education declines.

This does not happen everywhere. In countries that inherited an overwhelmingly publicly-financed system only the very rich can opt out, and the return on private education is lower because of a flatter wage structure. In this setting the middle and upper-middle classes, deeply concerned with the quality of education, tend to throw their support behind improving the public system. Yet, they will do so in ways that may reproduce class-based differentiation within the public system. Based on an analysis of the British system, one striking finding is that a great deal of differentiation happens because high-educated, high-income parents, who are most concerned with the quality of the education of their children, move into good school districts and bid up housing prices in the process. As property prices increase, those from lower socio-economic strata are increasingly shut out from the best schools.

Even in countries with less spatial inequality, in part because of a more centralized provision of public goods, socioeconomic inequality may be reproduced through early tracking of students into vocational and academic lines. This is because the choice of track is known to be heavily dependent on the social class of parents. This is reinforced by the decisions of firms to offer additional training to their best workers, which disadvantages those who start at the bottom. There is also evidence that such training decisions discriminate against women because firm-based training require long tenures and women are less likely to have uninterrupted careers. So strong VET systems, although they tend to produce less wage inequality, can undermine intergenerational class mobility and gender equality.

The rise of economic inequality also has consequence for politics. While democratic politics is usually seen as compensating for market inequality, economic and political inequality in fact tend to reinforce each other. Economic and educational inequality destroy social networks and undermines political participation in the lower half of the distribution of incomes and skills, and this undercuts the incentives of politicians to be attentive to their needs. Highly segmented labor markets with low mobility also undermine support for redistribution because pivotal “insiders” are not at risk. Labor market “dualism” therefore delimits welfare state responsiveness to unemployment and rising inequality. In a related finding, the winners of globalization often oppose redistribution, in part because they are more concerned with competitiveness and how bloated welfare states may undermine it.

Economic, educational, and political inequalities thus also tend to reinforce each other. But the extent and form of such inequality vary a great deal across countries. This special issue helps explain why and suggests the need for an interdisciplinary approach that is attentive to national institutional and political context oppose redistribution.

Marius R. Busemeyer is Professor of Political Science at the University of Konstanz, Germany. Torben Iversen is Harold Hitchings Burbank Professor of Political Economy at Harvard University. They are Guest Editors of the Socio-Economic Review April 2014 special issue on The Political Economy of Skills and Inequality which is freely available online until the end of May 2014.

Socio-Economic Review aims to encourage work on the relationship between society, economy, institutions and markets, moral commitments and the rational pursuit of self-interest. The journal seeks articles that focus on economic action in its social and historical context. In broad disciplinary terms, papers are drawn from sociology, political science, economics and management, and policy sciences.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Laptop in classic library. By photogl, via iStockphoto.

The post The political economy of skills and inequality appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTwenty years after the Rwandan GenocideWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineThe economics of sanctions

Related StoriesTwenty years after the Rwandan GenocideWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineThe economics of sanctions

Voluntary movement shown in complete paralysis

Scientists, using epidural stimulation over the lumbar spinal cord, have enabled four completely paralyzed men to voluntarily move their legs.

Kent Stephenson is one of the four. This stimulation experiment wasn’t supposed to work for him; he is what clinicians call an AIS A. This is a measure of disability, formally the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS), that rates impairment from A (no motor or sensory function) to D (ability to walk). Kent, a mid-thoracic paraplegic, has what is considered a “complete” injury. Kent’s doctors told him it was a waste of time to pursue any therapy; per the dogma, A’s don’t get better. Well, the young Texan, who was hurt five years ago on a dirt bike, didn’t get the message. He likes to cite a fortune cookie he got shortly after his injury. It said, “Everything’s impossible until somebody does it.”

Kent had the stimulator implanted. A few days later they turned it on. No one expected it to do anything. Researchers were only looking for a baseline measurement to compare Kent’s function later, after several weeks of intense Locomotor Training (guided weight supported stepping on a treadmill).

Kent tells the story: “The first time they turned the stim on I felt a charge in my back. I was told to try pull my left leg back, something I had tried without success many times before. So I called it out loud, ‘left leg up.’ This time it worked! My leg pulled back toward me. I was in shock; my mom was in the room and was in tears. Words can’t describe the feeling – it was an overwhelming happiness.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Kent was the second of the four. Rob Summers, three years ago, was the first to pioneer the concept that complete doesn’t mean what it used to; epidural stimulation could make the spinal cord more receptive to nerve signals coming from the senses or the brain. Seven months after he was implanted with a stimulator unit, he initiated voluntary movements of his legs. The other two subjects, Andrew Meas and Dustin Shillcox, also started moving within days of the implant. Summers probably could have initiated movement early on too, but the research team didn’t test for it – they had no reason to believe he could do it.

Here’s lead author of the Brain paper, Claudia Angeli, Ph.D., to explain. She is a senior researcher at the Human Locomotor Research Center at Frazier Rehab Institute, and an assistant professor at the University of Louisville’s Kentucky Spinal Cord Injury Research Center (KSCIRC).

“First, in the Lancet paper [regarding the first stimulation subject] it was just Rob, just one person. Yes, it was proof of concept, yes it went great. But now we are talking about four subjects. That’s four out of four showing functional recovery. What’s more, two of the four are categorized as AIS A – no motor or sensory function below the lesion level, with no chance for any recovery.”

The other two patients are classified AIS B: no motor function below the lesion but with some sensory function.

Left to right is Andrew Meas, Dustin Shillcox, Kent Stephenson, and Rob Summers, the first four to undergo task-specific training with epidural stimulation at the Human Locomotion Research Center laboratory, Frazier Rehab Institute, as part of the University of Louisville’s Kentucky Spinal Cord Injury Research Center, Louisville Kentucky.

How does this work? The epidural stimulation supplies a continuous electrical current, at varying frequencies and intensities, to specific locations on the lower part of the spinal cord. A 16-electrode spinal cord stimulator, commonly used to treat pain, is implanted over the spinal cord at T11-L1, a location that corresponds to the complex neural networks that control movement of the hips, knees, ankles and feet.

The leg muscles are not stimulated directly. The epidural stimulation apparently awakens circuitry in the spinal cord. “In simple terms,” says Dr. Angeli, “we are raising the excitability or gain of the spinal cord. Let’s say you have an intent to move. That signal originates in the brain and gets through to the spinal cord but the cord is not aware enough or excited enough to do anything with that intent. When we add the stimulation, the spinal cord networks are made a little more aware, so when the intent comes through, the cord is able to interpret it and movement becomes voluntary.”

The theory behind spinal cord stimulation is that these spinal cord networks are smart: they can remember and they can learn. The current work builds on decades of research. Susan Harkema, Ph.D. (University of Louisville) and V. Reggie Edgerton, Ph.D. (University of California Los Angeles) have led the effort. Dr. Harkema is Principal Investigator for the epidural stimulation projects and Director of the Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation’s NeuroRecovery Network. Dr. Edgerton, a member of the Reeve Foundation’s International Research Consortium on Spinal Cord Injury, is a basic scientist whose work attempts to understand human locomotion and how the brain and spinal cord adapt and change in response to various interventions, including activity, training and stimulation.

Dr. Harkema says plans are in place to implant eight more patients in the next year. Four will mirror the first group, matched by age, level of injury, time since injury, etc. (Gender, by the way, is not a factor; men with spinal cord injury happen to outnumber women four to one.) Another four patients will be stimulated specifically to control heart rate and blood pressure. Dr. Harkema said one of the first four had issues with low blood pressure. When the stimulator was on, though, the pressure was raised, even without contracting any muscles. They want to assess that sort of autonomic recovery in greater detail.

The research team is aware that epidural stimulation can enhance autonomic function in paralyzed subjects; indeed, the first four subjects report improved temperature control, plus better bowel, bladder, and sexual function. Data is being collected to present that part of the stimulation story in another paper.

Does this mean anyone with a spinal cord injury with an implanted stimulator can move? Not necessarily, says Dr. Harkema. “But what I want people to know about this study is that we need to change our attitude about what a complete injury is, challenge the dogma that in AIS A patients there is no possibility of recovery. The view is that it is not a worthwhile investment to offer even intense rehabilitation to people with complete injuries. They’re not going to recover. But the message now is that there is a tremendous amount available. These individuals have potential for recoveries that will improve their health and quality of life. Now we have a fundamentally new strategy that can dramatically affect recovery of voluntary movement in those with complete paralysis, even years after injury.”

Sam Maddox reports on neuroscience research for the Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation. He lives in Southern California. The paper about this research, ‘Altering spinal cord excitability enables voluntary movements after chronic complete paralysis in humans‘, appears in Brain: A Journal of Neuroscience.

Brain provides researchers and clinicians with the finest original contributions in neurology. Leading studies in neurological science are balanced with practical clinical articles. Its citation rating is one of the highest for neurology journals, and it consistently publishes papers that become classics in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Video and image both used with permission from the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation.

The post Voluntary movement shown in complete paralysis appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesExpressing ourselves about expressiveness in musicTwenty years after the Rwandan Genocide10 things you didn’t know about Parkinson’s Disease

Related StoriesExpressing ourselves about expressiveness in musicTwenty years after the Rwandan Genocide10 things you didn’t know about Parkinson’s Disease

April 8, 2014

Preparing for OAH 2014

Each year the Organization of American Historians gathers for a few days of networking and education, and this year the annual meeting will be held in Atlanta from 10-13 April 2014. This year’s conference theme is “Crossing Borders,” highlighting the impact of migration on the history of the United States. Organizers are encouraging attendees to cross a few professional borders as well — from career level to specialties.

The meeting will kick off with THATCamp, the humanities and technology camp from OAH, on Wednesday 9 April. Scholars have already proposing sessions on librarian-faculty partnerships, advice on teaching digital humanities, and digital mapping and modelling.

If you’re interested in the intersection of history scholarship and technology, you may want to speak with editors Adina Popescu Berk, Ph.D., Jon Butler Ph.D, and Susan Ware Ph.D on Friday, 11 April at 2:00 p.m. in the OUP Booth #411 to discuss the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History and the American National Biography Online. The Oxford Reference Encyclopedia in American History will provide students and scholars with vetted, reliable, historiographically-informed, and regularly updated online reference material in all areas. The landmark American National Biography offers portraits of more than 18,700 men and women — from all eras and walks of life — whose lives have shaped the nation.

You’ll discover another conference highlights on the exhibit floor: The Tuskegee Airmen: The Segregated Skies of World War II, exploring the history and heroism of the first African American pilots to fly in combat during World War II. Here a brief introduction from Todd Moye’s Freedom Flyers to help prepare you:

“Nearly one thousand young men with similar backgrounds and similar expectations graduated from the Tuskegee Army Flying School between 1941 and 1945. Roughly 14,000 additional men and women worked alongside the pilots in some capacity –as civilian or military flight instructors, as secretaries, parachute-packers, medical doctors and nurses, mechanics, and in dozens of other jobs. Their personal narratives-the stories that describe what it was like to both propel and ride a wave of social change-survive in the archives of the Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Prospect, an effort on the part of the U.S. National Park Service to record the memories of the men and women who fought Adolf Hitler and Jim Crow simultaneously. Black pilots and black military and civilian support personnel in the Army Air Corps/Air Forces, those who served overseas and those who remained stateside, all shared the experience of fighting what the editors of the Pittsburgh Courier first called a “Double Victory” campaign: war against fascism abroad and racial discrimination at home.”

That’s one of over 534 books, 140 journals, and even a TV monitor and multiple iPads (to show off our new and updated online resources) that we’re bringing. Stop by to check out these OAH 2013 prize-winning titles too:

Winner of the Winner of Ellis W. Hawley Prize, Kate Brown’s Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters

Winner of the OAH Liberty Legacy Foundation Award: Susan Carle’s Defining the Struggle: National Organizing for Racial Justice, 1880-1915

Winner of the James A. Rawley prize Brenda Stevenson’s The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins: Justice, Gender, and the Origins of the LA Race Riots

You’ll also find complimentary copies of the OAH’s Journal of American History, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. In June 1914, the Mississippi Valley Historical Review put out its first issue. In celebration, Oxford’s journals team is making one article from each of its 10 decades of publishing freely available.

For a change of pace, Ian Ruskin’s performance of “To Begin the World Over Again: the Life of Thomas Paine” on Thursday, 10 April, 5:15 p.m. is not to be missed. But if you want a little time away from the conference, we asked the newest member of the Oxford History team, Senior Marketing Manager, John Hercel what his favorite things to do in Atlanta are:

World of Coca-Cola: Did you know that Coca-Cola was created over 128 years ago by pharmacist, John S. Pemberton? When Coca-Cola was first available they averaged nine servings a day in Atlanta — today the estimate is 1.9 billion servings daily worldwide! Current exhibits at World of Coca-Cola include American Originals: Norman Rockwell and Coca-Cola (a look at how Coca-Cola has been featured in pop culture) and the Coca-Cola vault (where you can get as close as possible to the secret formula).

Inside CNN: Offering tours of the largest of CNN studios 48 bureaus, Inside CNN allows visitors to experience the fast-paced world of television news — by visiting the working studios, seeing and hearing live audio and videos feeds, and learning how the news is produced and broadcast around the world.

Don’t forget to come by Oxford’s reception on Friday, April 11 at Nikolai’s Roof starting at 5:30 -Have a little wine, a little cheese, and mingle with our authors, friends, and colleagues.

See you soon!

Oxford History Team

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in American History including books, journals, and online products. Follow them on Twiter @OUPAmHistory and follow all the OAH activities with the #OAH2014 hashtag.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Preparing for OAH 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRoberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetryTwenty years after the Rwandan GenocideA brief history of ethnic violence in Rwanda and Africa’s Great Lakes region

Related StoriesRoberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetryTwenty years after the Rwandan GenocideA brief history of ethnic violence in Rwanda and Africa’s Great Lakes region

Roberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetry

The late Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño is of course best-known as a novelist, the author of ambitious, sprawling novels like The Savage Detectives and 2666. But before turning to prose, Bolaño started out as a poet; in fact, he often said he valued poetry more highly than fiction and sometimes claimed he was a better poet than novelist. His work is marked by a deep and abiding fascination with poetry and the people who write, read, and teach it. As Ben Ehrenreich wrote several years ago in an essay for the Poetry Foundation, “through his legions of fictional poets (some more fictional than others), through their political compromises, their self-betrayals, their struggles and feuds both petty and grand, Bolaño built a world.”

Ehrenreich is surely right about the importance of poetry, and fictional poets, to Bolaño’s oeuvre, but the critical discussion of this element of Bolaño’s work thus far has mostly remained on a general plane, instead of connecting his writing to particular poets and poetry movements. However, with the recent publication of his unfinished novel Woes of the True Policeman and of his complete poetry in The Unknown University, Bolaño’s rather surprising links to a specific poetry movement — the New York School of poetry — have come into sharper focus.

It is common for readers to link Bolaño to Latin American and Spanish literary influences, to European avant-garde movements, or to other fiction writers. But Bolaño clearly read and absorbed the New York School of poetry and painting, along with a truly astonishing range of other sources. Although commentators on his work have barely mentioned it thus far, the New York School plays an important role in his work. It flickers just on the margins of Bolaño’s fictional universe, a ghostly example of the kind of poetry — as well as the type of intimate avant-garde community of like-minded others — that continually beckons and frustrates Bolaño and his characters.

Bolaño’s preoccupation with poetry can perhaps be seen best in his wonderful novel The Savage Detectives, which is actually a novel about poets. At its heart is a semi-fictional movement of young poets Bolaño calls the “Visceral Realists” (loosely based upon his own youthful involvement in a coterie called the Infrarealists). Throughout the remarkable opening section of the novel, this group — with all of its subversive energy, its iconoclasm and playfulness, its goofy, idealistic naivete, romanticism, and tragic flaws — reminds one of a host of other avant-garde communities, including the Surrealists, the Beats, and the New York School.

But it is more than just a novel about poets. The Savage Detectives is a moving meditation on poetry as a horizon of possibility and disillusionment. In fact, it’s one of the most exhilarating, devastating, exhausting, and revealing accounts of avant-garde poetry — and the movements and social worlds that sustain it — that I have encountered. It portrays the avant-garde as dream, as tragedy, as farce, as inspiring coterie and impossible community, tantalizing potential and heart-breaking, inevitable failure. In this, Bolaño echoes one of the hallmarks of the New York School itself: an intense, often ironic awareness of the paradoxes inherent in any avant-garde community, both its allure and its limitations.

[image error]

Larry Rivers, “The Athlete’s Dream” (1956) Source: Luna Commons

However, The Savage Detectives contains few direct references to the New York poets themselves (except for a passing reference to poets Ted Berrigan and John Giorno). Traces of the New York School stand out more prominently in the recently published book Woes of the True Policeman, one of the many (and perhaps the last) of Bolaño’s posthumous works that have appeared in recent years. At the novel’s center is a Chilean university professor named Óscar Amalfitano who falls in love with a young Mexican artist whose specialty is making forgeries of paintings by … Larry Rivers, of all people. Rivers, of course, was Frank O’Hara’s close friend, collaborator, and sometime lover, and the painter who is perhaps most closely allied, both socially and aesthetically, with the New York poets. This unusual detail — and the figure of Rivers himself — becomes a significant thread in Bolaño’s novel. The young artist, Castillo, explains that he sells the forgeries to a Texan who “then sells them to other filthy rich Texans.” When Castillo informs Amalfitano that Rivers is “an artist from New York,” he replies “I know Larry Rivers. I know Frank O’Hara, so I know Larry Rivers.”

Soon after, as Amalfitano meditates on the strangeness of this situation — the amateurish Rivers’ forgeries, the Texans who buy them, and the art market in New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas — Bolaño writes:

“he immediately pictured those fake Berdies, those fake camels, and those extremely fake Primo Levis (some of the faces undeniably Mexican) in the private salons and galleries, the living rooms and libraries of modestly prosperous citizens… And then he imagined himself strolling around Castillo’s nearly empty studio, naked like Frank O’Hara, a cup of coffee in his right hand and a whiskey in his left, his heart untroubled, at peace with himself, moving trustingly into the arms of his new lover” (58).

Near the end of the book, the Rivers plot culminates with a strange and funny anecdote about running into Larry Rivers himself at an exhibition of his work.

The novel also features an amusing collection of Amalfitano’s “Notes for a Class in Contemporary Literature: The Role of the Poet.” This takes the form of an almost Buzzfeed-ready list that consists of items like “Happiest: Garcia Lorca,” “Banker of the soul: T.S. Eliot,” and “Strangest wrinkles: Auden.” Among other names cited in this rather crazy, irreverent list, one finds several important figures of the New York School – Frank O’Hara, Ted Berrigan, and Diane Di Prima — getting top honors in some strange categories: “Biggest cock: Frank O’Hara,” “Best movie companion: Elizabeth Bishop, Berrigan, Ted Hughes, José Emilio Pacheco,” and under “Biggest nervous wreck: Diane Di Prima”.

Signs of Bolaño’s interest in poets of the New York School can be found elsewhere across the body of his work, as when Frank O’Hara pops up in a short story collected in Last Evenings on Earth in which two poets meet, share poems with one another, and discuss their influences: “We talked a while longer, about Sanguinetti and Frank O’Hara (I still like Frank O’Hara but I haven’t read Sanguinetti for ages).” In the newly published collection of his complete poetry, The Unknown University, Bolaño’s connection to O’Hara is considerably more substantial. He not only uses a passage by Frank O’Hara as an epigraph to a poem, but the (untitled) poem itself closely echoes O’Hara’s work:

I listen to Barney Kessel

and smoke smoke smoke and drink tea

and try to make myself some toast

with butter and jam

but discover I have no bread and

it’s already twelve thirty at night

and the only thing to eat

is a nearly full bottle

of chicken broth bought this

morning and five eggs and a little

muscatel and Barney Kessel plays

guitar stuck between a

rock and an open socket

I think I’ll make some consommé and

then get into bed

to re-read The Invention of Morel

and think about a blond girl

until I fall asleep and

start dreaming.

(translated by Laura Healey)

With its “I do this, I do that” narrative conjuring up an ordinary but melancholy-tinged everyday moment, its references to listening to music, and jazz at that (Barney Kessel), its intimate and conversational tone, its lack of punctuation and its headlong rush, Bolaño’s poem seems to intentionally evoke O’Hara’s signature style.

In another poem in The Unknown University, Bolaño chronicles his experience of reading Ted Berrigan’s 1963 book The Sonnets.

A Sonnet

16 years ago Ted Berrigan published

his Sonnets. Mario passed the book around

the leprosaria of Paris. Now Mario

is in Mexico and The Sonnets on

a bookshelf I built with my own

hands. I think I found the wood

near Montealegre nursing home

and I built the shelf with Lola. In

the winter of ’78, in Barcelona, when

I still lived with Lola! And now it’s been 16 years

since Ted Berrigan published his book

and maybe 17 or 18 since he wrote it

and some mornings, some afternoons,

lost in a local theatre I try reading it,

when the film ends and they turn on the light.

(translated by Laura Healey)

The poem portrays the speaker’s formative encounter with Berrigan’s ground-breaking collection of experimental sonnets, but also hints at the frustrations or limitations of his exposure to it: the “lost” speaker, who may also have recently lost his lover (Lola), merely tries to read the book. He seems to long for the energy he seems convinced Berrigan must have had so many years ago when he wrote those poems. The poem also underscores both the cosmopolitan nature of Bolaño’s imagination and the international reach of the New York School of poets. Berrigan’s book The Sonnets, like this sonnet itself, crosses time and space, speaking across 16 years, and sliding across boundaries and nationalities: written in New York, circulated around Paris by a Latin American poet who is now in Mexico, read by a young 26 year old Chilean poet in a movie theater in Barcelona.

Bolaño of course read voraciously, immersing himself fully in a wide range of 20th century avant-garde writing and art, but as the final pieces of his work appear in translation, it has become clearer than ever that he seems to have had a special connection to a poetry movement that sprouted from a place far from Santiago, Mexico City, Barcelona, and other key points in his own geography — the world of Frank O’Hara, Larry Rivers, Ted Berrigan, and other New York poets.

Poetry — especially the kind of poetry the New York School produced, and even more so, embodied, in its example and its ambivalent attitudes about community — seemed to exemplify Bolaño’s guiding belief about art in general: that it always promises us shimmering possibilities and perpetual disappointment at the same time.

Andrew Epstein is Associate Professor of English at Florida State University. He is the author of Beautiful Enemies: Friendship and Postwar American Poetry.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Roberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetry appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!Five jazz concerts I wish I had been atMake the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting: pass H.R. 4085

Related StoriesHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!Five jazz concerts I wish I had been atMake the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting: pass H.R. 4085

Happy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!

“But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve …”

– Othello (Act 1, Sc. 1, l.64)

April 2014 sees Shakespeare mature to the ripe old age of 450, and to celebrate we have collected a multitude of quotes from the famous bard in the below graphic, crafting his features with his own words.

To read the free scenes, open the graphic as a PDF.

Download the graphic as a jpg or PDF.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online provides an interlinked collection of authoritative Oxford editions of major works from the humanities. Scholarly editions are the cornerstones of humanities scholarship, and Oxford University Press’s list is unparalleled in breadth and quality. Read more about the site, follow the tour , or watch the full story .

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Happy 450th birthday William Shakespeare! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEntitling early modern women writersI’m dreaming of an OSEO ChristmasWorld Art Day photography contest

Related StoriesEntitling early modern women writersI’m dreaming of an OSEO ChristmasWorld Art Day photography contest

Twenty years after the Rwandan Genocide

We are now entering the month of April 2014—a time for reflection, empathy, and understanding for anyone in or involved with Rwanda. Twenty years ago, Rwandan political and military leaders initiated a series of actions that quickly turned into one of the 20th century’s greatest mass violations of human rights.

As we commemorate the genocide, our empathy needs to extend first to survivors and victims. Many families were destroyed in the genocide. Many survivors suffered enormous hardships to survive. Whatever our stand on the current state of affairs in Rwanda, we have to be enormously recognizant of the pain many endured.

In this brief post, I address three issues that speak to Rwanda today. I do so with trepidation, as discussions about contemporary Rwanda are often polarized and emotionally charged. Even though I am critical, I shall try to raise concerns with respect and recognition that there are few easy solutions.

My overall message is one of concern. At one level, Rwanda is doing remarkably and surprisingly well—in terms of security, the economy, and non-political aspects of governance. However, deep resentments and ethnic attachments persist, hardships and significant inequality remain. While it is difficult to know what people really feel, my general conclusion is that the social fabric remains tense beneath a veneer of good will. A crucial issue is that the political system is authoritarian and designed for control rather than dialogue. It is also a political system that many Rwandans believe is structured to favor particular groups over others. Fostering trust in such a political context is highly unlikely.

I also conclude that a “genocide lens” has limits for the objective of social repair. The genocide lens has been invaluable for achieving international recognition of what happened in 1994. But that lens leads to certain biases about Rwanda’s history and society that limit long-term social repair in Rwanda.

Rwandan Genocide Memorial. 7 April 2011. El Fasher: The Rwandan community in UNAMID organized the 17th Commemoration of the 1994 Genocide against Tutsi hold in Super Camp – RWANBATT 25 Military Camp (El Fasher). Photo by Albert Gonzalez Farran / UNAMID. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via UNAMID Flickr.

During the past 20 years, a sea change in international recognition has occurred. Fifteen years ago, very few people knew globally that genocide took place in Rwanda. Today, the “Rwandan Genocide” is widely recognized as a world historical event. That global recognition is an achievement. We also know a great deal more about the causes and dynamics of the genocide itself.

However, several important controversies and unanswered questions remain. One is who killed President Habyarimana on 6 April 1994. Another is how to conceptualize when the plan for genocide began. Some date the plan for genocide to the late 1950s; others to the 1990s; still others to April 1994. A third question is how one should conceptualize RPF responsibility. Some depic the former rebels as saviors who stopped the genocide. Others argue that their actions were integral to the dynamics that led to genocide. And there are other issues as well, including how many were killed. Each of these issues remains intensely debated and hopefully will be the subject of open-minded inquiry in the years to come.

Contemporary Rwanda is at one level inspiring. The government is visionary, ambitious, and accomplished. The plan is to transform the society, economy, and culture—and to wean the state from foreign aid. The government has successfully introduced major reforms. The tax system is much improved. Public corruption is virtually absent. Remarkable results in public health and the economy have been achieved. Public security is also dramatically improved.

But there is a dark side. Most importantly, the government is repressive. The government seeks to exercise control over public space, especially around sensitive topics—in politics, in the media, in the NGO sector, among ordinary citizens, and even among donors. The net impact is the experience of intimidation and, as a friend aptly put it, many silences.

That brings me to the delicate question of reconciliation. Reconciliation is an imprecise concept for what I mean. What matters is the quality of the social fabric in Rwanda—the trust between people—and the quality of state-society relations.

Jean Baptiste and Freda reconciliation. Photo by Trocaire. CC BY 2.0 via Trocaire Flickr.

A central pillar in Rwanda’s social reconstruction process has been justice. Much is written on gacaca, the government’s extraordinary program to transform a traditional dispute settlement process into a country-wide, decade-long process to account for genocide crimes. Gacaca brought some survivors satisfaction at finally seeing the guilty punished. Gacaca spawned some important conversations, led to important revelations, and prompted some sincere apologies.

But there were also a lot of problems. There were lies on all sides. There were manipulations of the system. Some apologies were pro-forma. And there were weak protections for witnesses and defendants alike. In many cases, justice was not done. But to my mind many the bigger issue is gacaca reinforced the idea that post-genocide Rwanda is an environment of winners and losers.

The entire justice process excluded non-genocide crimes, in particular atrocities that the RPF committed as it took power, in the northwest the late 1990s, and in Congo, where a lot of violence occurred. This meant that whole categories of suffering in the long arc of the 1990s and 2000s were neither recognized nor accounted for. Justice was one-sided. Many Rwandans experience it therefore as political justice that serve the RPF goal of retaining power.

The second issue is the scale. A million citizens, primarily Hutu, were accused. The net effect is that the legal process served to politically demobilize many Hutus, as Anu Chakravarty has written. Having watched the process of rebuilding social cohesion and state-society relations after atrocity in several places, I come to the conclusion that inclusion is vitally important.

If states privilege justice as a mechanism for social healing, judicial processes should recognize the multi-sided nature of atrocity. All groups that suffered from atrocity should be able to give voice to their experiences and, if punitive measures are on the table, seek accountability. Otherwise, in the long run, justice looks like a charade, one that ultimately may undermine the memories it is designed to preserve.

Here is where the “genocide lens” did not serve Rwanda well. A genocide lens narrates history as a story between perpetrators and victims. Yet the Rwandan reality is much more complicated.

Scott Straus is Professor of Political Science and International Studies at UW-Madison. Scott specializes in the study of genocide, political violence, human rights, and African politics. His published work includes several books on Rwanda and articles in African Affairs. A longer version of this article was presented at the “Rwanda Today: Twenty Years after the Genocide” event at Humanity House in The Hague on 3 April 2014. The author wishes to thank the organizers of that event.

To mark the 20th anniversary of the genocide, African Affairs is making some of their best articles on Rwanda freely available. Don’t miss this opportunity to read about the legacy of genocide and Rwandan politics under the RPF.

African Affairs is published on behalf of the Royal African Society and is the top ranked journal in African Studies. It is an inter-disciplinary journal, with a focus on the politics and international relations of sub-Saharan Africa. It also includes sociology, anthropology, economics, and to the extent that articles inform debates on contemporary Africa, history, literature, art, music and more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Twenty years after the Rwandan Genocide appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA brief history of ethnic violence in Rwanda and Africa’s Great Lakes regionWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineElinor and Vincent Ostrom: federalists for all seasons

Related StoriesA brief history of ethnic violence in Rwanda and Africa’s Great Lakes regionWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineElinor and Vincent Ostrom: federalists for all seasons

World Art Day photography contest

World Art Day is coming up on 15 April. We’re celebrating with some forthcoming blog posts, select free journal and online product articles, and a photography competition.

We invite you to celebrate with us by submitting your own art to our Street Photography Contest. According Grove Art Online, street photography is:

Genre of photography that can be understood as the product of an artistic interaction between a photographer and an urban public space. It is distinguished from documentary photography in that the photographer is not necessarily motivated by the evidentiary value or socio-political function of the resulting photographs. Unlike photojournalism, a street photographer’s images are not intended to illustrate a news story or other narrative. Instead, their primary goal is expressive and communicates a subjective impression of the experience of everyday life in a city. Thus neither the locale nor the subject-matter defines street photography; it is the photographer’s approach to the medium and movement through public space that differentiate street photography from related forms of photography.

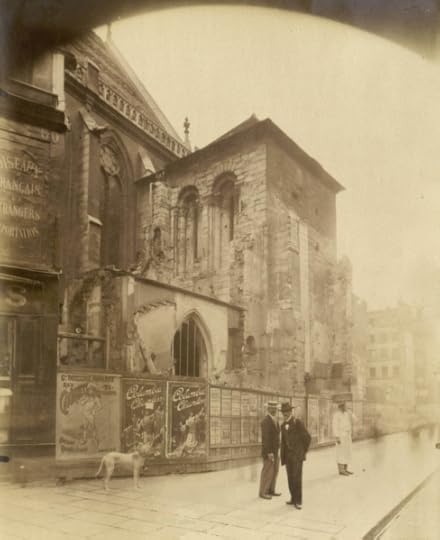

Eugène Atget. The steeple of the church before the restoration in 1913. Collections Department of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Live in a city? Have a camera? Send us your best shots.

The winner will receive $100 in Oxford University Press books. Second place will take home a copy of our Very Short Introduction to Photography.

To submit, please email groveartmarketing[at]oup[dot]com, with “photography competition” in the subject line. Please include a caption describing your work in the body of the email, and attach your image (maximum of 3MB). Competition will close on 28 April 2014. Please read our terms and conditions before entering the competition.

Victoria Davis works in marketing for Oxford University Press, including Grove Art and Oxford Art Online.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post World Art Day photography contest appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonuments Men and the FrickTreasures from Old Holland in New AmsterdamFive jazz concerts I wish I had been at

Related StoriesMonuments Men and the FrickTreasures from Old Holland in New AmsterdamFive jazz concerts I wish I had been at

Five jazz concerts I wish I had been at

Most people who have listened to jazz for very long have a list in their minds of the best live performances they’ve ever been to. I know I do. I remember with particular fondness a performance by Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson that I saw in the early 1980s in Modesto, California that was a benefit for local jazz musician and DJ Mel Williams’s Sickle Cell Anemia Foundation. It wasn’t so much that it was a groundbreaking concert as such–though I still remember how tight and in-the-pocket his band swung–but it was one of the first I ever went to.

As a kid in California’s Central Valley, an agricultural backwater at the time, I didn’t have that many chances to hear live jazz, and it was a revelation. I remember equally fondly seeing Johnny Griffin at Birdland in New York, when I was doing research for my first book, Monk’s Music (University of California Press, 2008). I had dug Griff on vinyl since I was in high school, and to see that band take the stage and hear him—old by then, but still brimming with intensity–burn through two sets of serious hard bop felt a little like coming home.

And most people who go see jazz regularly will tell you that the particular features of the venues where jazz happens color their experiences in tangible ways. For me, The Village Vanguard when it’s full has a kind of electricity that comes from the tight seating and the quality of the light in its cramped little basement space, as well as from its storied past. Sitting cheek-by-jowl with a couple hundred other fans to hear jazz in dim twilight in the same room where John Coltrane once played has a power that can’t be overstated. And being so close to the musicians in a room which has crisp acoustics doesn’t hurt, either.

These features and more make it common for jazz fans to feel that club dates are the best — or even the most authentic — way to hear the music. And yet, concerts, whether they be in monumental halls originally designed for classical music or in the purpose-built, often open-air spaces used for jazz festivals, have been an important context for the music as well. Since the 1920s jazz has been presented in these settings, often to truly great effect. As I say in my book on the Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane’s live recording at Carnegie Hall, while clubs may offer certain pleasures for musicians–a more interactive, intimate experience especially–concerts have had their value as well. Better pay, typically, for one, but also the opportunity to present their musical ideas in more formal venues.

I’ve seen some great jazz performances at clubs and in concerts, but still, sometimes, I wonder if I didn’t grow up at the wrong time, in the wrong place. There’s just so much I never had the chance to hear — Monk at the Five Spot, Coltrane at the Village Vanguard, Billie Holiday at Café Society, Ellington anywhere … With that in mind, here are five jazz concerts I wish I had seen, in no particular order:

5. Newport Jazz Festival, 1956

To have been at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1956 to hear Ellington’s band play the set that included “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” would have been, as the beatniks used to say, “beyond the beyond.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Duke Ellington Orchestra at Newport 1956, “Diminuendo in Blue” and “Crescendo in Blue,” separated, as Ellington puts it, “by an interval by Paul Gonsalves”

The story is well-enough known to jazz aficionados, that Ellington’s star was on the wane, and that this concert was a way back for them, that on this tune Gonsalves took a solo that was a standard part of the show and turned it into a 27-chorus blues tour-de-force, inspired by a woman in a little black dress who danced and danced and danced while he blew. What else is jazz but that?

I would have worn my groovy fedora, some high-waisted white slacks, combed Brylcreem through my hair and dug every minute of it.

4. Weather Report in Tokyo, 1972

Weather Report’s work, by the later 1970s, includes some pretty dispiriting instrumental pop, but in 1972, Zawinul, Shorter, and company made some music that was vital, and living somewhere on the edge of experimental funk, avant garde noise, and deep groove.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Medley of “Vertical Invader,” “Seventh Arrow,” “T.H.,” and “Doctor Honoria Causus,” from the live recording Weather Report Live in Tokyo

Recordings of this music can only begin to capture its range. Even on high fidelity equipment, the silences are not as heavy as they would have been in the concert hall, not as pregnant with expectation, and the band at full volume is not as overwhelming. In some sense jazz performances are always a bit of a ritual, but this seems like an immersive experience of another level.

3. The Clef Club Orchestra, Massed Gala 1912 and 1913

Under the leadership of James Reese Europe, the Clef Club orchestra played at some of the best private dances New York society had in the early years of the 20th century, but they also presided over at least two “massed galas” in Carnegie Hall in the years 1912 and 1913. While Europe’s bands as they were recorded around the time included fewer than a dozen musicians, an image of the full group on stage at Carnegie Hall has better than fifty. The excitement generated by the group’s sheer size and its range of instruments including cellos, harp-guitars, drums, brass, and who knows what is born out in descriptions from the time that emphasize spectacle.

Click here to view the embedded video.

James Reese Europe’s Society Orchestra, “The Castle Walk,” 1914

Somehow the recordings we know Europe by just don’t seem like they do justice …

2. Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall

I’ve written about Monk for so many years now, it is a particular sadness to say I never saw him play. Our lives overlapped a bit–I had just turned 10 when he died–but he had stopped playing in public for the most part by the time I was born, and even if he had been playing, he wouldn’t likely have played where I was.

I would love to have seen him play with any of his groups, but there was something special about that band and that night in November, 1957.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane, “Monk’s Mood”

It’s not just that the band gave a brilliant performance–though they did. It’s more. As I say at some length in my book on this concert recording, the selection of tunes is great, the chance to hear Coltrane working out a sound in relation to Monk’s established style is a treat, and there is something brilliant about the way Shadow Wilson and Ahmed Abdul-Malik come together to underpin the whole event.

Though only Monk’s set was released on CD, I would love to have had the chance to hear this performance in context with the rest of the groups on that evening’s remarkable bill, including Ray Charles, Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, Chet Baker, Zoot Sims, Sonny Rollins.

1. Newport Jazz Festival 1969, Final Night

OK, so technically this wasn’t necessarily, strictly speaking, a jazz concert, as such, but I would kill to have been at the NJF the night Miles Davis famously saw Led Zeppelin drive the kids wild. This is another one that is well-known and the stuff of legend, but everything about it would have felt like a lightening bolt at the time. Would Zeppelin play or wouldn’t they? Promoter George Wein was convinced that they would start a riot, but after some controversy, they did close an evening that also included Herbie Hancock’s sextet, and the Buddy Rich band, among others.

We often hear about Zeppelin in this story, but the whole festival was kind of incredible. The British rock band played at the end of a weekend that included George Benson, Bill Evans, Sun Ra’s Arkestra, Blood, Sweat and Tears, Art Blakey, Dave Brubeck, Sly and the Family Stone, and Jimmy Smith hosting a jam session that included Sonny Stitt and Ray Nance, among others.

So maybe I was born too soon. Though, in the past month I’ve had my head expanded by Vijay Iyer’s trio, by William Parker, and by the Bad Plus, all in the little college town in East Central Illinois where I live, so perhaps it’s all just fine.

Gabriel Solis is Associate Professor of music, African American studies, and anthropology at the University of Illinois. A scholar of jazz, American popular music, and the transnational politics of race, his work has appeared in leading journals of ethnomusicology, music history, and sociology. He is the author of Monk’s Music: Thelonious Monk and Jazz History in the Making (California, 2008), co-editor with Bruno Nettl of Musical Improvisation: Art, Education, and Society (Illinois, 2009), a forthcoming book on singer, songwriter, and performing artist, Tom Waits titled Sounding America: Gender, Genre, Memory, and the Music of Tom Waits (California), and Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five jazz concerts I wish I had been at appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMake the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting: pass H.R. 4085A brief history of ethnic violence in Rwanda and Africa’s Great Lakes regionChallenges to the effectiveness of international law

Related StoriesMake the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting: pass H.R. 4085A brief history of ethnic violence in Rwanda and Africa’s Great Lakes regionChallenges to the effectiveness of international law

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers