Oxford University Press's Blog, page 824

April 12, 2014

A publisher before wartime

This year marks the centenary of the start of the First World War. This cataclysmic event in world history has been examined by many scholars with different angles over the intervening years, but the academic community hopes to gain fresh insight into the struggles of war on this anniversary. From newly digitized diaries to never-before-seen artifacts, new stories of the war are taking shape.

Oxford University Press has its own war story. With publishing dating back to the fifteenth century, the Press also felt the effects of the war: the rupture of a strong community and culture in the Jericho neighborhood of Oxford, the broken lives of the men and women of the Press who enlisted, the shadow of the Press still operating on the homefront in Oxford, and the disastrous return home — for those who did. We present the first in a series of videos with Oxford University Press Archivist Martin Maw, examining how life at the Press irrevocably changed between 1914-1919. Here he sets the stage for life in Jericho before the outbreak of war.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Martin Maw is an Archivist at Oxford University Press. The Archive Department also manages the Press Museum at OUP in Oxford. Read his previous blog posts: “Jericho: The community at the heart of Oxford University Press” and “Sir Robert Dudley, midwife of Oxford University Press.”

In the centenary of World War I, Oxford University Press has gathered together resources to offer depth, detail, perspective, and insight. There are specially commissioned contributions from historians and writers, free resources from OUP’s world-class research projects, and exclusive archival materials. Visit the First World War Centenary Hub each month for fresh updates.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A publisher before wartime appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBritain, France, and their roads from empireStreet Photography from Grove Art OnlineA call for oral history bloggers

Related StoriesBritain, France, and their roads from empireStreet Photography from Grove Art OnlineA call for oral history bloggers

April 11, 2014

Street Photography from Grove Art Online

In honor of World Art Day on 15 April 2014, Oxford is hosting a street photography competition. But what exactly is street photography? The below article from Grove Art Online by Lisa Hostetler explores the history of street photography, as well as its relationship to contemporary art. As Dr. Hostetler explains, this type of art includes “photographs exposed in and of an urban environment and made with artistic intent.”

Street photography

Genre of photography that can be understood as the product of an artistic interaction between a photographer and an urban public space. It is distinguished from documentary photography in that the photographer is not necessarily motivated by the evidentiary value or socio-political function of the resulting photographs. Unlike photojournalism, a street photographer’s images are not intended to illustrate a news story or other narrative. Instead, their primary goal is expressive and communicates a subjective impression of the experience of everyday life in a city. Thus neither the locale nor the subject-matter defines street photography; it is the photographer’s approach to the medium and movement through public space that differentiate street photography from related forms of photography.

1. Technological factors and the roots of street photography

Photographs made in or of an urban environment are as old as the history of the medium itself, but street photography did not coalesce into a distinct form of photographic practice until the 20th century. Louis Daguerre‘s view of the Boulevard du Temple (1838), made from the window of his studio, suggests one reason why: the daguerreotype’s relatively long exposure time meant that the majority of people on the street were invisible in the photograph; the only person who stood still long enough to register on the plate was a man who stopped to get a shoeshine. In the first decade after the announcement of photography’s invention, photographic optics and chemistry were not fast enough to capture bustling crowds—a hallmark of urban life and a key element in street photography. The wet collodion negatives that dominated photographic practice in the 1850s and 1860s continued to involve significant time, requiring the photographer to prepare, expose, and develop negatives all in the space of about ten minutes. This made immersion in the experience of the street difficult and did not lend itself easily to spontaneity—a quality upon which later street photography thrived. With the introduction of dry-plate negatives in the 1870s and then gelatin silver roll film in the 1880s, photographic technology became more conducive to street photography. In addition, the launch and dissemination of the 35mm camera beginning in the mid-1920s was a particular boon to street photography; its hand-held size allowed for candid, easy movement through well-populated spaces, and many of the films developed for it were sensitive enough to record images even in situations with limited light. Unlike earlier snapshot cameras, the photographer held the camera up to his or her eye to look through the viewfinder instead of peering down into it from above. This facilitated the sense of the camera as an extension of the mind’s eye and permitted photographers to move along with the rhythm of street life more fully. With such technological developments in place, street photography flourished, particularly in the decades immediately after World War II.

Before that time, much of the photography that has come to be associated with the genre had its roots in another form of the medium. For example, Charles Marville’s photographs of French architecture and condemned roads in Paris suggest urban life in the 1850s and 1860s, but they were produced primarily to record the existence of culturally significant buildings and infrastructure slated for demolition. Similarly, Eugène Atget‘s images of Paris from the late 19th century and early 20th were originally intended as documents for artists rather than as independent works of art. Nevertheless, their collective impression of the city as a place with a specific mood—one in which ageing building façades and reflective store windows combine to evoke the mien of an anonymous urban populace—established Atget as a godfather of street photography for generations of subsequent artists.

The seeds of street photography are also present in photographs from the early years of the 20th century by Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand. Stieglitz’s Winter, Fifth Avenue (1893) and The Terminal (1893) record quotidian scenes of New York life, employing snow and smoke to enhance the pictorial power of the image. In photographs such as Wall Street, New York (1915), Strand created an image that defines the experience of scale in the city’s financial district while juxtaposing the structural geometry of the built environment with the pattern of figures and shadows on the sidewalk. Blind (1916) depicts an unfortunately common feature of urban life, a blind beggar on the street, but the image may also be interpreted as a comment on the voyeurism of candid photography in public. Thus, both Stieglitz and Strand made photographs on New York streets that contributed to the development of the genre, but street photography was not their primary pursuit.

2. Development and fruition

In the years between World War I and World War II, several photographers had a formidable impact on the subsequent maturation of street photography. Hungarian photographer André Kertész‘s images of Paris made after his adoption of the 35mm camera in 1928, such asMeudon (1928) and Carrefour Blois (1930), communicate the everyday surrealism and graphic élan characteristic of metropolitan life. Kertész was an important figure for both Brassaï and Henri Cartier-Bresson—two photographers whose work fundamentally shaped the practice of street photography after World War II. Brassaï, whom Kertész introduced to photography, became especially well known for his photographs of Paris at night. His images of the characters, sights, and activities endemic to the nocturnal life of France’s capital city were published in book form asParis de nuit (1933), a foundational book of street photographs. Kertész was also a mentor to Cartier-Bresson, whose concept of the ‘decisive moment’—the instant when subject-matter and compositional form align, as in Behind the Gare Saint Lazare (1932)—guided his photographs of everyday life in Paris, Madrid, New York, and other cities beginning in the 1930s. Famous for his devotion to the Leica camera, rejection of flash photography, and purported refusal to crop his images, Cartier-Bresson advocated spontaneity and intuition as the driving forces of creative photography. His 1952 book Images à la sauvette laid out these principles and became a touchstone for subsequent generations of street photographers.

The immediate post-war years inaugurated a particularly rich era in the history of street photography in the United States. Several key street photographers—including Lisette Model, Helen Levitt, Louis Faurer, William Klein, Saul Leiter (b 1923), and Robert Frank—produced their best-known images between 1940 and 1959. Some, such as Helen Levitt, distilled decisive moments from city life into universal human images. Others, such as William Klein, transformed restless glances and brash gestures into grainy, often blurry images that embodied the frantic pace and aggressive rhythm of post-war New York City. Meanwhile, Louis Faurer trained his camera on the idiosyncratic characters, gritty nightlife, and poignant personal interactions that were common to the urban scene but absent from mainstream representations of American social life. Such photographs imparted a particularly subjective view of public space, underscoring the expressive possibilities of photography. In 1955–6, Robert Frank travelled throughout the United States making the photographs that would eventually become The Americans, a book of his work published in France in 1958 and in the United States in 1959. Although not composed exclusively of street photographs, the book established street photography as a legitimate creative pursuit and launched Frank as one of the consummate American photographers of his generation.

Street photography flourished outside the United States during the post-war period as well. In France it was dominated by three figures: Robert Doisneau, Willy Ronis, and Izis. Doisneau’s The Kiss (1950), which depicts a sailor passionately kissing a woman in front of the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, captured the energy and optimism to which many aspired after the devastation of World War II. It became one of the best-known photographs of the era. In England, Roger Mayne photographed everyday life on working-class streets after the war. His perceptive impressions of Teddy Boys and working ‘stiffs’ sharing the pavement in London foreshadowed generational tensions that would erupt in the 1960s. Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama also turned to street photography during these years. His images suggest an undercurrent of restlessness and repression in a society shattered by war and caught between tradition and modernity.

By the 1960s the snapshot aesthetic had become a prominent motif in American photography, thanks in large part to curator John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. A master of this mode, Garry Winogrand applied his talents to the streets of New York and other cities throughout the 1960s and 1970s. His street photographs, in which titled horizon lines, apparently haphazard framing, and bold movements make frequent appearances, seem to channel the kinetic energy of his subjects, making many of his images iconic examples of the genre.

3. Street photography and contemporary art

As conceptual artists began to incorporate photographs into their work in the late 1960s and 1970s, the presence of photography in contemporary art expanded, and street photography became a form of performance art. Douglas Huebler (1924–97) and Sophie Calle created work that shared street photography’s embrace of chance interactions in public space. However, their work replaced street photography’s spontaneous, subjective edge with the prescriptive procedural frameworks characteristic of conceptual art.

In the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, as the world became increasingly saturated by photographic imagery that was ever easier to manipulate, street photography found new contexts. Its emphasis on spontaneity and intuition promised an inherent authenticity, making it an appealing genre for a number of contemporary artists. Some, like Philip-Lorca diCorcia (b 1951), used it to question photography’s axiomatic association with truth. DiCorcia’s photographs on international city streets in the 1990s appear to be extemporaneous examples of street photography, but in fact, the scenarios were carefully arranged and lit. Other artists, such as Zoe Strauss (b 1970), continued to pursue street photography in its straightforward form. Her images, made in South Philadelphia, extended the accessibility, sincerity, and sense of personal exposure associated with classic street photography into the contemporary age. Outside the United States, artists such as Alexey Titarenko (b 1962) and Graeme Williams have also brought the genre of street photography into the 21st century.

Bibliography

J. Livingston: The New York School: Photographs, 1936–1963 (New York, 1992)

J. Meyerowitz and C. Westerbeck: Bystander: A History of Street Photography (New York, 1994)

K. Brougher and R. Ferguson: Open City: Street Photographs since 1950 (Oxford and Ostfildern, 2001)

U. Eskildsen: Street & Studio: An Urban History of Photography (London and New York, 2008)

L. Lee and W. Rugg, eds: Street Art, Street Life: from the 1950s to Now (New York, 2008)

L. Hostetler: Street Seen: The Psychological Gesture in Photography 1940–1959 (Milwaukee, 2010)

Lisa Hostetler

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Street Photography from Grove Art Online appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWorld Art Day photography contestMonuments Men and the FrickThe early history of the guitar

Related StoriesWorld Art Day photography contestMonuments Men and the FrickThe early history of the guitar

A call for oral history bloggers

Over the past few months, the Oral History Review has become rather demanding. In February, we asked readers to experiment with the short form article. A few weeks ago, our upcoming interim editor Dr. Stephanie Gilmore sent out a call for papers for our special Winter/Spring 2016 issue, “Listening to and for LGBTQ Lives.” Now, we’d like you to also take over our OUPBlog posting duties.

Well, “take over” might be a hyperbole. However, we have always hoped to use this and our other social media platforms to encourage discussion within the oral history discipline, and to spark exchanges with those working with oral histories outside the field. We like to imagine that through our podcasts, interviews and book reviews, we have brought about some conversations or inspired new ways to approach oral history. However, we can do better.

Well, “take over” might be a hyperbole. However, we have always hoped to use this and our other social media platforms to encourage discussion within the oral history discipline, and to spark exchanges with those working with oral histories outside the field. We like to imagine that through our podcasts, interviews and book reviews, we have brought about some conversations or inspired new ways to approach oral history. However, we can do better.

Towards that end, we are putting out a “call for blog posts” for this summer. These posts should fall in line with the aforementioned goal to promote the engagement between and beyond those in oral history field. Like our hardcopy counterpart, we are especially interested in posts that explore oral history in the digital age. As you might have gathered, we thrive on puns and the occasional, outdated pop culture reference. These are even more appreciated when coupled with clean and thoughtful insights into oral history work.

We are currently looking for posts between 500-800 words and 15-20 minutes of audio or video. Though, because we operate on the wonderful worldwide web, we are open to negotiation in terms of media and format. We should also stress that while we welcome posts that showcase a particular project, we do not want to serve as landing page for anyone’s kickstarter.

Please direct any additional questions, pitches or submissions to the social media coordinator, Caitlin Tyler-Richards, at ohreview[at]gmail[dot]com. You may also message us on Twitter (@oralhistreview) or Facebook.

We can’t wait to see what you all have to say.

Caitlin Tyler-Richards is the editorial/media assistant at the Oral History Review. When not sharing profound witticisms at @OralHistReview, Caitlin pursues a PhD in African History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research revolves around the intersection of West African history, literature and identity construction, as well as a fledgling interest in digital humanities. Before coming to Madison, Caitlin worked for the Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown University.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow the latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Retro Microphone. © Kohlerphoto via iStockphoto.

The post A call for oral history bloggers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nunsOral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nuns - EnclosureCSI: Oral History - Enclosure

Related StoriesOral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nunsOral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nuns - EnclosureCSI: Oral History - Enclosure

“The Mouth that roared”: Peter Benchley’s Jaws at 40

The novel that scared a generation out of the ocean and inspired everything from Shark Week to Sharknado recently turned forty. Commemorations of Peter Benchley’s Jaws have been as rare as megalodon sightings, however. Ballantine has released a new paperback edition featuring an amusing list of the author’s potential titles (The Grinning Fish, Pisces Redux), and in February an LA fundraiser for Shark Savers/Wildaid performed excerpts promising “an evening of relentless terror (and really awkward sex).” Otherwise, silence.

The reason is obvious. Steven Spielberg’s 1975 adaptation is so totemic that the novel is considered glorified source material, despite selling twenty-million copies. Rare is the commentator who doesn’t harp on its faults, and rarer still the fan who defends it. Critics dismiss the book as “airport literature,” while genre lovers complain it lacks “virtually every single thing that makes the movie great.” Negative perceptions arguably begin with Spielberg himself. Amid the legendary production problems that plagued the making of the movie—pneumatic sharks that didn’t work, uncooperative ocean conditions that tripled the shooting schedule—the director managed to suggest that his biggest obstacle was Benchley’s original narrative: “If we don’t succeed in making this picture better than the book,” he said, “we’re in real trouble.”

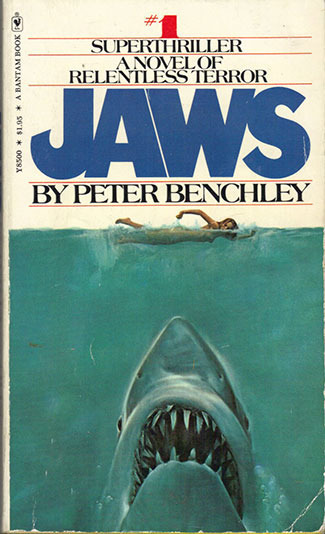

Jaws by Peter Benchley, first edition paperback, 1975.

It’s unfortunate that Benchley gets so little love. In the mid-seventies book-Jaws didn’t simply inspire a movie but was integral to the overall phenomenon. My mother brought home the hardback months before Spielberg even began filming. As the pre-release hype roiled throughout spring 1975, her ten-year old cobbled together $1.95 for his very own paperback, which featured Roger Kastel’s iconic illustration of a massive beast with a mouthful of stalactites and stalagmites speeding toward a naked woman. (The hardback’s cover was toothless, both literally and figuratively; the shark looks like an index finger with a paper cut aiming to tickle its prey). Shortly after seeing Jaws I owned the soundtrack with John Williams’s ominous dun-dun theme; co-screenwriter Carl Gottlieb’s The Jaws Log, which detailed the torturous filming; and a Jaws beach towel, which made me the envy of the pool, if only briefly.

Obsessed, I collected newspaper and magazine clippings on sharks. Following the loony lead of Mad, Cracked, and Sick, I drew goofy, pun-laden parodies (Paws) and became a connoisseur of gory rip-offs (Grizzly, Orca). My paperback was essential to feeding my frenzy. I managed only three matinees before the movie left town. That was as many times per hour as I probably pored over Benchley’s bloodier passages. The urge to revisit scenes would today send a young fan to YouTube for clips or to Google for GIFs and memes. For a pre-Internet, pre-computer kid, however, rereading was the original refresh and replay. I knew Jaws so inside out I could cite the page number where the legs of the boy my age “were severed at the hips” and “sank, spinning slowly,” and I could flip straight to the bizarre moment when the shark hunter Quint insults his quarry’s penis.

I also detailed differences between the book and movie in my journal. (I was an only child; I had free time). The first change beguiled the beginning writer in me: “[Benchley] didn’t like any of his characters,” Spielberg declared, “so none of them were very likable. He put them in a situation where you were rooting for the shark to eat the people—in alphabetical order.”

The director flattened Benchley’s characters into eminently relatable archetypes: the everyman-cop with a near-fatal fear of water, Martin Brody (Roy Scheider); Quint, the aged fisherman (Robert Shaw); and the cocky scientist, Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss). Their counterparts on the page admittedly lack both their comic relief (Scheider’s famous deadpan “You’re going to need a bigger boat” upon first seeing the shark) and their riveting monologues (especially Quint’s tale of surviving the 1945 sinking of the USS Indianapolis, brilliantly if soddenly delivered by Shaw). Benchley preferred his people perturbing, not heroic. His insecure, snockered Brody belligerently spoils his wife’s dinner party; Hooper beds Mrs. Brody; and for bait Quint uses a dolphin fetus he brags of carving from its mother’s womb.

Despite its armrest-gripping terror, Spielberg’s movie is cathartic because man ultimately conquers nature. Like most audiences, I fist-pumped and cheered when Brody blew the shark to smithereens by exploding an oxygen tank. The book’s battle is less intense and yet more primal. Benchley’s captain hurls his harpoons as Queequeg or Tashtego would instead of firing them from a gun, while Quint’s and Hooper’s deaths are cruelly ironic. Maybe it’s because my friends and I had great fun sneaking ketchup packets into the pool to reenact it, but Shaw’s blood-belching final close-up never haunted me as much as the novel’s Ahab-inspired image of Quint dragged to a watery grave snared in his own harpoon line. Hooper’s fate is even more macabre. As the ichthyologist is turned into a human toothpick Brody attempts an ill-conceived rescue by strafing the water with rifle fire. He manages to miss the shark completely yet land a bullet in Hooper’s neck. Long before reading Melville, I intuited that this was how a naturalistic universe mocked humanity.

Jaws remains a very seventies-novel. I rather like that quality, much as, by contrast, I like that Spielberg’s movie hasn’t aged a day. (Thanks to Deep Blue Sea and Sharknado, we know how un-scary CGI sharks are compared to life-size pneumatic ones). Benchley’s book feels the way the first half of its decade did: amorphous and off-center, dubious of heroes, titillated by dirty talk.

Perhaps I might feel differently if I hadn’t read it on the cusp of adolescence, but Jaws reminds me of how novels attuned me to adult frailties. It’s going overboard to say it exposed me to the sharkish side of humanity, but I could recognize Brody’s resentments, Quint’s unapologetic violence, and Hooper’s sense of sexual entitlement in men I knew. A year after I outgrew my obsession I was berated for entering a community-theater dressing room and discovering a very Mrs. Brody-like friend of my family’s kissing a man I knew wasn’t her husband.

Benchley’s novel certainly made me afraid of the water, but unlike the movie, it did nothing to convince me I was any safer on dry land.

Kirk Curnutt is professor and chair of English at Troy University’s Montgomery, Alabama, campus, where Scott Fitzgerald met Zelda Sayre in 1918. His publications include A Historical Guide to F. Scott Fitzgerald (2004), the novels Breathing Out the Ghost (2008) and Dixie Noir (2009), and Brian Wilson (2012). He is currently at work on a reader’s guide to Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post “The Mouth that roared”: Peter Benchley’s Jaws at 40 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWriting as technologyThe American Noah: neolithic superheroReflections on Son of God

Related StoriesWriting as technologyThe American Noah: neolithic superheroReflections on Son of God

BICEP2 finds gravitational waves from near the dawn of time

The cosmology community is abuzz with news from the BICEP2 experiment of the discovery of primordial gravitational waves, through their signature in the cosmic microwave background. If verified, this will be a clear indication that the very young universe underwent a period of acceleration, known as cosmic inflation. During this period, it is thought that the seeds were laid down for all the structures to form later in the universe, including galaxies, stars, and indeed ourselves.

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is radiation left over from the Hot Big Bang, first discovered in 1965 and corresponding to a temperature only about 2.7 degrees above absolute zero. In 1992 the COBE satellite made the first detection of temperature variations in the CMB, and successive experiments, including satellite missions WMAP and Planck, have been accurately measuring these variations which have become the key tool to understanding our universe.

In addition to its brightness, radiation can have a polarisation, meaning that the electromagnetic oscillations that make up the light have a preferred orientation, e.g. horizontal or vertical. This same effect is used in 3D cinemas, where light of different polarisations reaches your left or right eye, the lenses in the glasses blocking out one or other from each eye. In the CMB the polarisation signal is very small, and moreover comes in two types, known as E-mode and B-mode polarisation. The second of these, corresponding to a twisting pattern of polarisation on the sky, is what BICEP2 has discovered for the first time. This twisting pattern is the signature of gravitational waves, created in the early universe and whose presence causes space-time itself to ‘wobble’ as the light from the CMB crosses the Universe.

The Dark Sector Laboratory at Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. At left is the South Pole Telescope. At right is the BICEP2 telescope. Photo by Amble, 2009. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The BICEP2 team have been working for several years with the single aim of measuring this signal; inflation predicted it to be there but said nothing about its strength. Based at the South Pole, where the unusually clear and dry air creates an ideal viewpoint for accurate measurement, three years of observations were carried out from 2010 to 2012. Their experiment differs from others measuring the CMB polarisation because they focussed on covering as large an area of the sky as possible, at relatively moderate angular resolution, in order to specifically target the B-mode signal.

While the discovery of gravitational waves had been widely rumoured in the days leading up to the announcement, including even the size of the measured signal, what took everyone’s breath away was the significance of the signal. At 6 to 7-sigma, it exceeds even the gold-standard 5-sigma used at CERN for the Higgs particle detection. Most would have expected something tentative, 2 or 3-sigma perhaps. We will want verification, of course, especially because the use of just a single wavelength of observation (the microwave equivalent of using just one colour of the rainbow) means the experiment is a little vulnerable to radiation from sources other than the CMB, such as intervening galaxies or emission caused by particles spiralling around our own Milky Way’s magnetic fields. The strength of the detection suggests that will not be an issue, but for sure we want to see independent confirmation by other experiments and at other wavelengths. Some may have announcements even before the end of the year, including the Planck satellite mission.

The response of the cosmology community to BICEP2 has been staggeringly swift. Early communication and discussion was already underway during the web-streamed BICEP2 press conference, via a Facebook discussion group set up by Scott Dodelson at Fermilab. The first science papers using the results were already appearing on arXiv.org database within the next couple of days (including these ones by me!). By the end of March, only two weeks after the announcement, there were already almost 50 available papers with ‘BICEP’ in the title, written by researchers all around the world. Papers on BICEP2 are clearly going to be a main theme for astronomy journals, including MNRAS, for the remainder of the year as we all try to figure out what, in detail, it all means.

Andrew Liddle is Professor of Theoretical Astrophysics at the Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh. He is an editor of the OUP astronomy journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS) is one of the world’s leading primary research journals in astronomy and astrophysics, as well as one of the longest established. It publishes the results of original research in astronomy and astrophysics, both observational and theoretical.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post BICEP2 finds gravitational waves from near the dawn of time appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesVoluntary movement shown in complete paralysisA record-breaking lunar impactThe early history of the guitar

Related StoriesVoluntary movement shown in complete paralysisA record-breaking lunar impactThe early history of the guitar

Writing as technology

In honor of the beginning of National Library Week this Sunday, 13 April 2014, we’re sharing this interesting excerpt from Contemporary Fiction: A Very Short Introduction. As technology continues to evolve, the way we access books and information is changing, and libraries are continuously working to keep up-to-date with the latest resources available. Here, Robert Eaglestone presents the idea of the seemingly simple act of writing as a form of technology.

The essential thing about technology is that, despite our iPhones and computers and digital cameras and constant change, it is not new at all. In fact, human civilization over the longest possible time grew up not just hand in hand with technology but because of technology. Technology isn’t just something added to ‘being human’ the way we might acquire another gadget: the essence of technology is in the creation of tools, technology in the creation of farming and in buildings, cities, roads, and machines. (p. 87) And perhaps the most important form of technology is right here in front of you, you’re looking at it right now, this second: writing. It too—these very letters here, now—is, of course, a technology. Writing is a ‘machine’ to supplement both the fallible and limited nature of our memory (it stores information over time) and our bodies over space (it carries information over distances). So it’s not so much that we humans made technology: technology also made us. As we write, so writing makes us. It is technology that allows us history, as a recorded past and so a present, and so, perhaps a future. So to think about technology, and changes in technology, is to think about the very core of what we, as a species, are and about how we are changing. As we change technology, we change ourselves. And all novels, because they are a form of technology, implicitly or explicitly, do this.

The word ‘technology’ comes from the Greek word ‘techne’: techne is the skill of the craftsman or woman at building things (ships, tables, tapestries) but also, interestingly, the skill of crafting art and poetry. ‘Techne’ is the skill of seeing how, say, these pieces of wood would make a good table if sanded and used in just that way, or seeing the shape of David in the block of marble, or in hearing how these phrases will best represent the sadness you imagine Queen Hecuba feels in mourning her husband and sons. It’s also the skill, in our age, of working out how best to use resources to eliminate a disease globally, or to deliver high-quality education. But ‘techne’ has become more than just skill: it is a whole way of thinking about the world. In this ‘technological thinking’, everything in the world is turned into a potential resource for use, everything is a tool for doing something. Rocks become sources of ore; trees become potential timber for carpentry or pulp for paper; the wind itself is captured by a windmill or, in a more contemporary idiom, ‘farmed’ in a wind farm. Companies have departments of ‘human resources’. Even an undeveloped piece of natural land, purposely left undisturbed by buildings and agriculture, becomes a ‘wilderness park’, a ‘machine’ in which to relax and recharge (p. 88) oneself from the strains of everyday life. Great works of literature are turned into a resource through which to measure people, by exams or in quizzes. This is the point of the old saw, ‘To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail’: to a technological way of thinking, everything looks like a resource to be used (just as to a carpenter, all trees look like potential timber; to a university academic, all fiction is a source of exam questions). More than this, the modern networks which use these resources are bigger and more complex. Where once the windmill ground the miller’s corn to make bread, now a huge global food system moves food resources about internationally: understanding and using these networks are a career in themselves. This technological thinking, rather than the tools it produces, is a taken-for-granted ‘framework’ in which we come to see and understand everything. Although many people have made this sort of observation about the world, the influential and contentious German philosopher Martin Heidegger, from whom much of the above is drawn, made it most keenly.

Is this a bad thing? It certainly sounds as if it might be. Who wants, after all, to be seen only as a ‘human resource’? It’s precisely technological thinking that has put the world at risk of total destruction. On the other hand, technology has offered so much to so many: in curing illness and alleviating pain, for example. The question is too big to answer in these simple terms of ‘bad’ or ‘good’. However, contemporary fiction seems very negative about technology, positing dystopias and awful ends for humanity. However, I want to suggest that contemporary fiction doesn’t find the world utterly without hope, precisely because of technology.

Robert Eaglestone is Professor of Contemporary Literature and Thought at Royal Holloway, University of London. He is Deputy Director (and formerly Director) of the Holocaust Research Centre. His research interests are in contemporary literature and literary theory, contemporary philosophy, and on Holocaust and genocide studies. He is the author of Contemporary Fiction: A Very Short Introduction and Doing English: A Guide for Literature Students (third revised edition) (Routledge, 2009).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Writing as technology appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDisposable captivesA conversation with Alberto GallaceRoberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetry

Related StoriesDisposable captivesA conversation with Alberto GallaceRoberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetry

April 10, 2014

Disposable captives

The decision by the administrators of the Copenhagen Zoo to kill a two-year-old giraffe named Marius by shooting him in the head in February 2014, then autopsy his body in public and feed Marius’ body parts to the lions held captive at the zoo created quite an uproar. When the same zoo then killed the lions (an adult pair and their two cubs) a month later to make room for a more genetically-worthy captive, the uproar became more ferocious.

Animal lovers across the globe were shocked and sickened by these killings and couldn’t understand why this bloodshed was being carried out at a zoo.

The zoo’s justification for killing Marius was that he had genes that were already “well represented” in the captive giraffe population in Europe. The justification for killing the lions was that the zoo was planning to introduce a younger male who was not genetically related to any of the females in the group.

Sacrificing the well-being and even the lives of individual animals in the name of conserving a diverse gene pool is commonplace in zoos. Euthanasia, usually by means less grotesque than a shotgun to the head, is quite common in European zoos. In US zoos, contraception is often used to prevent “over-representation” of certain gene lines. The European zoos’ reason for not using birth control the way most American zoos do is that they believe allowing animals to reproduce provides the animals with the opportunity to engage the fuller range of species typical behaviors, but that also means killing the undesirable offspring. In both European and US zoos, families are broken up and individuals are shipped to other facilities to diversify and manage the captive gene pool.

If this all has a ring of eugenic reasoning, consider what the executive director of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Gerald Dick, had to say: “In Europe, there is a strict attempt to maintain genetically pure animals and not waste space in a zoo for genetically useless specimens.”

A stuffed giraffe, representing Marius, at a protest against zoos and the confinement of animals in Lisbon, 2014

The high-profile slaughter of Marius and the lions that ate his body focus attention on an important debate about the purpose of zoos and more generally the ethics of captivity. Originally, zoos were designed to amuse, amaze, and entertain visitors. As public awareness of the plight of endangered species and their diminishing habitats grew, zoos increasingly saw their roles as conservation and education. But just what is being conserved and what are the educational lessons that zoo-goers take away from their experiences at the zoo?

A recent study suggests that zoo-goers learn about biodiversity by visiting zoos. Critics have suggested that the study is not particularly convincing in linking the small increase in understanding of biodiversity with the complex demands of conservation. Some zoos are committed to direct conservation efforts; the Wildlife Conservation Society (aka the Bronx Zoo) and the Lincoln Park Zoo are just two examples of zoos that have extensive and successful conservation programs. Despite these laudable programs, these WAZA-accredited zoos, like the European zoos, are also in the business of gene management and a central tenet of the current management ethos is to value genetic diversity over individual well-being.

Awe-inspiring animals such as giraffes and gorillas and cheetahs and chimpanzees are not seen as individuals, with distinct perspectives, when viewed, as Dick says, as either useful or useless “specimens.” They are valued, if at all, as representative carriers of their species’ genes.

This distorts our understanding of other animals and our relationships to them. Part of the problem is that zoos are not places in which animals can be seen as dignified. Zoos are designed to satisfy human interests and desires, even though they largely fail at this. A trip to the zoo creates a relationship in which the observer, often a child, has a feeling of dominant distance over the animals being looked at. It is hard to respect and admire a being that is captive in every respect and viewed as a disposable specimen, one who can be killed to satisfy a mission that is hard for the zoo-going public to fully understand, let alone endorse.

Causing death is what zoos do. It is not all that they do, but it is a big part of what happens at zoos, even if this is usually hidden from the public. Zoos are institutions that not only purposely kill animals, they are also places that in holding certain animals captive, shorten their lives. Some animals, such as elephants and orca whales, cannot thrive in captivity and holding them in zoos and aquaria causes them to die prematurely.

Death is a natural part of life, and perhaps we would do well to have a less fearful, more accepting attitude about death. But those who purposefully bring about premature death run the risk of perpetuating the notion that some lives are disposable. It is that very idea that we can use and dispose of other animals as we please that has led to the problems that have zoos and others thinking about conservation in the first place. When institutions of captivity promote the idea that some animals are disposable by killing “genetically useless specimens” like young Marius and the lions, they may very well be undermining the tenuous conservation claims that are meant to justify their existence.

Lori Gruen is Professor of Philosophy, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and Environmental Studies at Wesleyan University where she also coordinates Wesleyan Animal Studies and directs the Ethics in Society Project. She is the editor of The Ethics of Captivity.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Sit-in protest in Lisbon. Photo by Mattia Luigi Nappi, 2014. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Disposable captives appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRoberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetryA conversation with Alberto GallaceUnsung heroes of English etymology: Henry Bradley (1845-1923)

Related StoriesRoberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetryA conversation with Alberto GallaceUnsung heroes of English etymology: Henry Bradley (1845-1923)

The early history of the guitar

I am struck by the way the recent issue of Early Music devoted to the early romantic guitar provides a timely reminder of how little is known about even the recent history of what is today the most popular musical instrument in existence. With millions of devotees worldwide, the guitar eclipses the considerably more expensive piano and allows a beginner to achieve passable results much sooner than the violin. In England, the foundations for this ascendancy were laid in the age of the great Romantic poets. It was during the lifetimes of Keats, Shelley, Byron, and Coleridge, extending from 1772 to 1834, that the guitar rose from a relatively subsidiary position in Georgian musical life to a place of such fashionable eminence that it rivalled the pianoforte and harp as the chosen instrument of many amateur musicians.

What makes this rise so fascinating is that it was not just a musical matter; the vogue for the guitar in England after 1800 owed much to a new imaginative landscape for the guitar owing much to Romanticism. John Keats, in one of his letters, tellingly associates the guitar with popular novels and serialized romances that were shaped by the interests of a predominantly female readership and were romantic in several senses of the word with their stories of hyperbolized emotion in exotic settings. For Byron, a poet with a wider horizon than Keats, the guitar was a potent image of the Spanish temper as the English commonly imagined it during the Napoleonic wars and long after: passionate and yet melancholic, lyrical and yet bellicose in the defence of political liberty, it gave full play to the Romantic fascination with extremes of sentiment. For Shelley in his Poem “With a Guitar,” the gentle sound of the instrument distilled the voices of Nature who had given the materials of her wooded hillsides to make it, but it also evoked something beyond Nature: the enchantment of Prospero’s isle and a reverie reaching beyond the limitations of sense to “such stuff as dreams are made on.” As the compilers of the Giulianiad, England’s first niche magazine for guitarists, asked in 1833: “What instrument so completely allows us to live, for a time, in a world of our own imagination?”

Given the wealth of material for a social history of the guitar in Regency England, and for its engagement with the romantic imagination, it is surprising that so little has been written about the instrument. It does say something about why England is widely regarded as the poor relation in the family of guitar-playing nations. The fortunes of the guitar in the early nineteenth century are commonly understood in a continental context established especially by contemporary developments in Italy, Spain, and France. To some extent, this is an understandable mistake, for Georgian England received rather more from the European mainland in the matter of guitar playing than she gave, but it is contrary to all indications. But we may discover, in the coming years, that the history of the guitar in England contains much that accords with that nation’s position as the most powerful country, and the most industrially advanced, of Western Europe at the close of the Napoleonic Wars.

There is so much material to consider: references to the guitar and guitarists in newspapers, advertisements, novels, short stories, poems and manuals of deportment, the majority of them published in the metropolis of London. The pictorial sources encompass a great many images of guitars and guitarists in a wealth of prints, mezzotints, lithographs, and paintings. The surviving music comprise a great many compositions for guitar, both in printed versions and in manuscript together with tutors that are themselves important social documents. Electronic resources, though fallible, permit a depth of coverage previously unattainable. Never have the words of John Thomson in the first issue of Early Music been more relevant: we set out on an intriguing journey.

Christopher Page is a long-standing contributor to Early Music. A Fellow of the British Academy, he is Professor of Medieval Music and Literature in the University of Cambridge and Gresham Professor of Music elect at Gresham College in London. In 1981 he founded the professional vocal ensemble Gothic voices, now with twenty-five CDs in the catalogue, from which he retired in 2000 to write his most recent book, The Christian West and its Singers: The first Thousand Years (Yale University Press, 2010).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Courtesy of Christopher Page. Do not use without permission.

The post The early history of the guitar appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!April Fool’s! Announcing winner of the second annual Grove Music spoof contestEight facts about the synthesizer and electronic music

Related StoriesHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!April Fool’s! Announcing winner of the second annual Grove Music spoof contestEight facts about the synthesizer and electronic music

A conversation with Alberto Gallace

From Facebook’s purchase of Oculus VR Inc. to the latest medical developments, technology is driving new explorations of the perception, reality, and neuroscience. How do we perceive reality through the sense of touch? Alberto Gallace is a researcher in touch and multisensory integration at the University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy, and co-author of In touch with the future: The sense of touch from cognitive neuroscience to virtual reality. We recently spoke to him about touch, personal boundaries, and being human.

Out of all the human senses, touch is the one that is most often unappreciated, and undervalued. When did you first become interested in touch research?

I was in Oxford as a visiting PhD student and working on multisensory integration, in particular on the integration between tactile and visual signals in the brain. Soon I realized that, despite the fact that is a very important sensory modality, there was not much research on touch, and there were not even a lot of instruments to study such sensory modality. I started by working more with engineers and technical workshops then with psychologists and neuroscientists, just because I needed some device to test the sense of touch in a different way as compared to what was done in the past. Touch was mainly studied with reference to haptic object recognition, mostly on visually impaired individuals or in terms of its physiological mechanisms. Many of the most relevant aspects of touch were very little, if not at all, investigated.

We use touch for walking, talking, eating, nearly everything basically. It also plays a major role on our interpersonal relationships, it affects the release of hormones and it contributes to define the boundary of our self.

We use touch for walking, talking, eating, nearly everything basically. It also plays a major role on our interpersonal relationships, it affects the release of hormones and it contributes to define the boundary of our self.

To my students I often say, where our touch begins, we are. I wanted to understand more of these topics. I wanted to compare touch with other sensory modalities. In doing that I was convinced that research on touch had to get away from the fingertips or hands and extend to the whole body surface. The more I studied this sense, the more I became interested in it. For every question answered there were many more without responses. I like touch a lot because there are many things that still need to be understood about it, and I am a rather curious person, particularly when it comes to science.

What do you think has been the most important development in touch research in the past 100 years?

I am not sure if it’s the most important development, but what I certainly consider important is the recent study of certain neural fibres specialized in transmitting socially-relevant information via the sense of touch. That is, the C tactile afferents in humans, that are strongly activated by ‘caress like’ stimuli, might play an important role in many of our most pleasant social experiences. However, I should also say that my personal way to think about science is much more ‘future oriented’. That is, I believe that the most important developments in touch research are the ones that we will see in the next years. I am really looking forward to reading (or possibly writing) about them.

Why did you decide to research this topic?

Most of the previously published books on touch — there aren’t many, to be honest — were focused on a single topic. Most of them were based on research on visually-impaired individuals, and the large majority of them were authored books, a collections of chapters written by different people, sometimes with a different view. Charles [Spence, University of Oxford] and myself wanted something different, something more comprehensive, something that could help people to understand that touch is involved in many different and relevant aspects of our life. We envisioned a book where the more neuroscientific aspects of touch were addressed together with a number of more applied topics. We wanted something where people could see touch ‘at work’. We talk about the neural bases of touch, tactile perception, tactile attention, tactile memory, tactile consciousness, but also about the role of touch in technology, marketing, virtual reality, food appreciation, and sexual behaviour. Many of these topics have never been considered in a book on touch before.

Philippe Mercier’s The Sense of Touch

What do you see as being the future of research in this field in the next decade?

I think that research in my field, pushed by technological advances, will grow rapidly in the coming years. One of the fields where I see a lot of potential is certainly related to the reproduction of tactile sensations in virtual reality environments. Virtual reality will likely become an important part of our life, maybe not in the next decade, but certainly in a not so distant future. However, if we want to create believable virtual environments we need to understand more of our sense of touch, and in particular how our brain processes tactile information, how different tactile stimulations can lead to certain emotions and behaviours, and how tactile sensations can be virtually reproduced. Following the idea that ‘where our touch begins, we are’, research will certainly invest a lot of resources in trying to better understand the neurocognitive mechanisms responsible for supporting our sense of ‘body ownership’ (the feeling that the body is our own) and how this sense can be transferred to virtual/artificial counterparts of our self. Here research on touch will certainly play a leading role.

If you weren’t doing touch research, what would you be doing?

I think I’d work as a scientist in a different field, but always as a scientist. I am too curious about how nature works to do something different. Since I was twelve I’ve always had a special interest in astronomy and astrophysics and I can easily picture myself working in that field too. Understanding the secrets of black cosmic matter or studying the mysteries of white brain matter? Not sure which would be better. What I am sure about is that I like my job a lot, and I won’t change it with anything else that is not based that much on creativity and curiosity.

Alberto Gallace is a researcher at Department of Psychology, University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy, and co-author of In touch with the future: The sense of touch from cognitive neuroscience to virtual reality. His research interests include spatial representation, multisensory integration, tactile perception, tactile interfaces, body representation, virtual reality, sensory substitution systems, and neurological rehabilitation of spatial disorders.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Via Catalana Barcelona Plaça Catalunya 37. Photo by Judesba. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) The Sense of Touch, painting by Philipe Mercier. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post A conversation with Alberto Gallace appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDementia on the beachPagán’s planarians: the extraordinary world of flatwormsDopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brain

Related StoriesDementia on the beachPagán’s planarians: the extraordinary world of flatwormsDopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brain

Preparing for the Vis Moot 2014

This weekend will see the oral arguments for the 21st Annual Willem C. Vis International Commercial Arbitration Moot begin in the Law Faculty of the University of Vienna, an exciting event for students, coaches, arbitrators, and publishers. This yearly event is a highlight in the arbitration event calendar and a chance for lawyers and students from all over the world to meet. Oxford University Press will have a stand in the main meeting place, the Juridicum, and we’re looking forward to showcasing our great selection of products.

With nearly 100 mooting teams, the moot promises to be a busy, vibrant, and sociable event. To find out more about this year’s problem, visit the moot website. In case you didn’t know already, this year’s moot will be using the CEPANI rules.

At the OUP stand you will be able to find plenty of copies of the essential text, Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration. Last year we caught up with the authors to discuss the book and the future of international arbitration, watch the videos below to find out more.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Also available will be the second edition of Principles of International Investment Law by Rudolf Dolzer and Christoph Schreuer, and the third edition of Schlechtriem & Schwenzer: Commentary on the UN Convention on the International Sale of Goods (CISG) edited Ingeborg Schwenzer. If you come to the stand you will be able to demo the fantastic newly re-lauched online service Investment Claims on our iPads.

It’s hard not to notice that Vienna is a great location for this event, and with so much do to in between moots that you’ll be spoilt for choice. Once you’ve had a good look at the OUP stand, why not:

Take a walk to the MuseumsQuartier, one of the largest cultural areas in the world. Here you can admire the mixture of baroque and modern architecture and visit a number of great galleries including Leopold Museum and the MUMOK

Have a coffee and cake in Café Central, only a short walk from the Juridicum and offers a great coffee house experience

Take a trip to the beautiful Schonbrunn Palace on the outskirts of Vienna

See Klimt’s famous painting ‘The Kiss’ at The Belvedere

Visit the amazing Faberge exhibition on at Kunsthistorisches Museum

Explore the Easter markets nearby, where you can buy beautiful painted eggs (if you can get them home intact!) along with traditional Austrian food and drink

We’ll be setting up our stand early on Saturday (13 April) morning and will be packing up on Tuesday morning. Do come by and say hello if you’re at the Moot, we’re looking forward to seeing you!

Isabel Jones is Senior Marketing Executive in OUP UK’s Law department.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Preparing for the Vis Moot 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPreparing for International Council for Commercial Arbitration 2014Preparing for OAH 2014Challenges to the effectiveness of international law

Related StoriesPreparing for International Council for Commercial Arbitration 2014Preparing for OAH 2014Challenges to the effectiveness of international law

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers