Oxford University Press's Blog, page 823

April 14, 2014

A bookish slideshow

From ancient times to the creation of eBooks, books have a long and vast history that spans the globe. Although a book may only seem like a collection of pages with words, they are also an art form that have survived for centuries. In honor of National Library Week, we couldn’t think of a more fitting book to share than The Book: A Global History. The slideshow below highlights the fascinating evolution of the book.

Origin of the alphabet

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The proto-Sinaitic theory of the origin of the alphabet. Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators.

Illustrations of runic stones

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Illustrations of runic stones from the Danish scholar Carl Rafn’s ‘Runic Inscriptions in which the Western Countries are Alluded to’, in Mémoires de la Société Royale des Antiquaires du Nord, 1848–9 (Copenhagen, 1852); the variety of languages is notable. Private collection.

Composing frame

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

A composing frame with two sets of cases of type: the upper case lies at a steeper angle than the lower case. By permission of Oxford University Press.

Cuneiform signs

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Some cuneiform (wedge-shaped) signs, showing the pictographic form (c .3000 BC ), an early cuneiform representation (c. 2400 BC ), and the late Assyrian form ( c .650 BC ), now turned through 90 degrees, with the meaning. Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators.

Modern casebound Book

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Diagram of the structural features of a modern casebound book ready for casing in (adapted from Gaskell, NI ). Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators.

East Asian book forms

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Traditional East Asian book forms. A (top): scroll binding: 18 th -century printed Buddhist sutra (Japan). B (2 nd from top): pleated binding, 17 th -century printed Buddhist sutra (Japan). C (3 rd from top left): butterfly binding: 16th -century Buddhist MS (Japan). D (3 rd from top right): butterf19ly binding: contemporary printed book bound in traditional style (China). E (bottom left): wrapped back binding with original printed title label: 17th-century printed book (China). F (bottom centre): thread binding: 18th-century printed book (China). G (bottom right): protective folding case, MS title label: early 20th century (China). © J. S. Edgren

Medieval European bookbinding

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The basic structural features of a European bookbinding in the medieval and hand press periods. Line drawing by Chartwell Illustrators.

Pica italic matrices

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

A box of John Fell’s pica italic matrices, with some steel punches for larger capitals beneath them. By permission of Oxford University Press

In celebration of National Library Week we’re giving away 10 copies of The Book: A Global History, edited by Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H.R. Woudhuysen. Learn more and enter for a chance to win.

Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H. R. Woudhuysen are the authors of The Book: A Global History. Michael F. Suarez S.J. is Professor and Director of the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia. H. R. Woudhuysen is Rector of Lincoln College, Oxford.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A bookish slideshow appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Mexican-American War and the making of American identityWriting as technologyHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!

Related StoriesThe Mexican-American War and the making of American identityWriting as technologyHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!

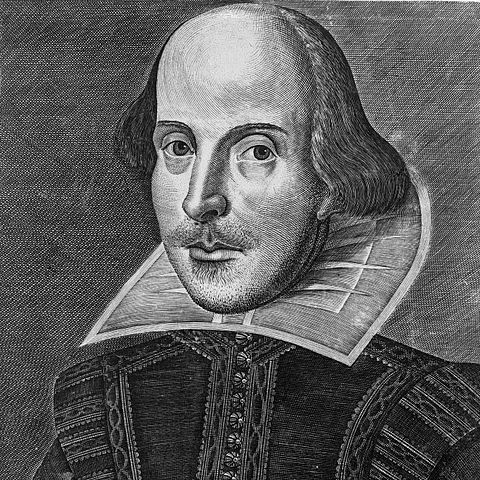

Shakespeare’s 450th birthday quiz

William Shakespeare was born 450 years ago this month, in April 1564, and to celebrate Oxford Scholarly Editions Online is testing your knowledge on Shakespeare quotes. Do you know your sonnets from your speeches? Find out…

William Shakespeare was born 450 years ago this month, in April 1564, and to celebrate Oxford Scholarly Editions Online is testing your knowledge on Shakespeare quotes. Do you know your sonnets from your speeches? Find out…

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Need a clue or two? Then take a look at our Shakespeare birthday infographic!

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) is a major publishing initiative from Oxford University Press, providing an interlinked collection of authoritative Oxford editions of major works from the humanities, including the complete Oxford Shakespeare series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Droeshout portrait of William Shakespeare. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shakespeare’s 450th birthday quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!Entitling early modern women writersI’m dreaming of an OSEO Christmas

Related StoriesHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!Entitling early modern women writersI’m dreaming of an OSEO Christmas

An interview with Brian Hughes, digital strategist

This week is National Library Week in the United States. Oxford University Press is celebrating the contributions of these institutions to communities around the world in a variety of ways, including granting free access to online products in the United States and Canada. To better understand the work that goes into these reference works, we sat down with Senior Marketing Manager Brian Hughes to discuss the challenges and opportunities of the digital space; how Oxford strives to provide knowledge to students, scholars, and researchers; and the hidden considerations that must be made.

What do you do here at Oxford University Press?

I’ve been with OUP for 14 years now and have seen many of our products develop from ideas on paper to the dynamic research and teaching tools they are today. After working in academic marketing for well over a decade, I moved to the global online team and I’m extremely lucky that my current role is diverse and ever-changing. That’s the exciting part of working with digital products.

Much of my time does involve working with the User Experience Platform Management (UXPM) Group, which looks at the functionality and design enhancements for our digital products. I’m also very involved in the Future Business Models Group, which looks at how we can better serve our customers in the near and distant future. The group discusses options and scopes out pilots that will help the business make evidence-based decisions about viable new sales models. For example, later this year we’ll be piloting a Pay-Per-View option on some of our products. In this case we are partnering with a third party but we will have reliable data that will aid us in determining whether building the option ourselves would be feasible. I’m also working with a group that’s looking to make our presence at academic conferences more efficient and further integrate our digital products in the day-to-day discipline marketing. It’s rewarding to work in so many areas and see how the digital program impacts them in a positive way.

What’s the dynamic of the product marketing team?

The biggest difference from my previous positions in academic marketing is that my daily interactions are strictly with those within OUP. Each of the groups and teams that I work with now are made up of an impressive cross-section of the organization: sales, market research, technology, finance, and design. Whether it’s deciding on a site change to Oxford Bibliographies or testing a new price for Grove Art, there’s a team of people helping to ensure the decision is the right one for the Press, both now and in the future.

How do you choose which enhancements to make or prioritize?

There’s a small assessment group that reviews all enhancement requests that come from different parts of the business. First and foremost, we think about how the enhancement is going to help the user. We ask ourselves a lot of questions:

Will this change improve the user journey?

How will it impact users coming from other Oxford digital products?

Are users expecting this functionality because it’s common on competitors’ products?

Of course, we always have to look at the cost. Generally the business case is strong and the benefits will outweigh the cost and the enhancement is approved. But when that’s not the case, it’s important that we in the assessment group provide context for the rejection and provide feedback. Just saying no isn’t fair. But in the end, if it’s good for the user and is cost effective, the change does get approved. Implementation isn’t always immediate. We have to design, test, and schedule the enhancement, which can take a few months, so it’s also important to explain that timeline to my colleagues throughout the business.

What makes excellent online reference from a user experience or web perspective?

Users expect digital products to be intuitive, information to be served up quickly, and finally, information to be as relevant as possible. It’s important once a user engages with any of our digital products that they are able stay within the OUP ecosystem. They came to us as a trusted resource, so we try to create connections between our online products — giving them all the information they need. We have a very short window in which to capture the users’ attention before they move on in their research. We are constantly working to provide them with the best online experience possible. It sounds like a simple task, but it takes a lot of work and a lot of people to make it happen.

What kinds of new tools or technologies would you love to explore further?

One very exciting tool we’re looking to implement within the next six months is an A/B testing system. This will be a very important piece of business intelligence that we’ll be able to use when it comes to enhancements and product development. Currently, we’re unable to test in a live environment, and being able to serve up attributes like availability markers or style changes to different groups will help us make the right decision for our users. I think this is going to be one of the most exciting and important pieces of UX in the next year for the digital program.

What should new users of Oxford’s online resources should know?

Oxford digital products are extremely dynamic. Not just when it comes to functionality or technology, but also content. Our content is being updated on a regular basis; we don’t just replicate the print in an online environment. New types of content are also being added, for instance, we’re adding timelines and commentary to supplement what has appeared in print.

Is there anything loyal users would be surprised to learn about our online resources?

One thing I was surprised to learn is just how much goes on “behind the scenes” to make our digital products better for users. Helping students and researchers along their digital journeys involves a lot more than site design. The team of people working to improve search results, linking, and deliver the best and most relevant content to our users. There’s a lot more than data feeds and style sheets when it comes to digital products.

Professionally speaking, I come from a print background and until I started in my new role, I had no idea how much work and effort went into any one of our products. In 2003, when Oxford Scholarship Online launched, there was nothing like it in the market. Someone once commented that “Oxford has the ability to see around the corner” when it comes to digital publishing. I think that’s pretty telling when it comes to our development and commitment to academic research.

Brian Hughes is Senior Marketing Manager for Oxford University Press’s online program, and oversees advancements on over 40 online products. He has worked at Oxford for 14 years.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post An interview with Brian Hughes, digital strategist appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesStreet Photography from Grove Art OnlineWriting as technologyThe early history of the guitar

Related StoriesStreet Photography from Grove Art OnlineWriting as technologyThe early history of the guitar

The Defamation Act 2013: reflections and reforms

How can a society balance both the freedom of expression, including the freedom of the press, with the individual’s right to reputation? Defamation law seeks to address precisely this delicate equation. Especially in the age of the internet, where it is possible to publish immediately and anonymously, these concerns have become even more pressing and complex. The Defamation Act 2013 has introduced some of the most important changes to this area in recent times, including the defence for honest opinion, new internet-specific reforms protecting internet publishers, and attempts to curb an industry of “libel tourism” in the U.K.

Dr Matthew Collins SC introduces the Defamation Act 2013, and discusses the most important reforms and their subsequent implications.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Dr Matthew Collins SC is a barrister based in Melbourne, Australia. He is a Senior Fellow at the University of Melbourne, a door tenant at One Brick Court chambers in London, and the author of Collins On Defamation.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Defamation Act 2013: reflections and reforms appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesExtreme makeover: England’s new defamation lawThe quest for ‘real’ protection for indigenous intangible property rightsOvercoming everyday violence [infographic]

Related StoriesExtreme makeover: England’s new defamation lawThe quest for ‘real’ protection for indigenous intangible property rightsOvercoming everyday violence [infographic]

April 13, 2014

The quest for ‘real’ protection for indigenous intangible property rights

Intellectual property rights (IPRs) and the regimes of protection and enforcement surrounding them have often been the subject of debate, a debate fuelled in the past year by the increased emphasis on free-trade negotiations and multi-lateral treaties including the now-rejected Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) and its Goliath cousin, the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA). The significant media coverage afforded to these treaties, however, risks thrusting certain perspectives of IPR protection and enforcement into the spotlight, while eclipsing alternative, but equally crucial voices that are perhaps in greater need of legitimate dialogue to safeguard their own collection of intangible rights. Caught in the vortex of inadequate recognition and ineffective protection, are the communal intellectual property rights of indigenous communities, centred on traditional knowledge (TK), traditional cultural expressions (TCE), expressions of folklore (EoF), and genetic resources (GR).

The fundamental incompatibility between current intellectual property rights regimes and the rights of indigenous peoples stems largely from the lack of understanding of the driving forces that have led to the development of traditional knowledge, traditional cultural expressions, expressions of folklore, and genetic resources – that of the protection of whole indigenous cultures through the preservation of the traditional knowledge acquired by these communities as a whole.

The issues are complex. Professor James Anaya’s 2014 keynote speech at the 26th Session of the Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore at WIPO highlighted the differences governing the intangible rights of indigenous peoples generally, and why these world views have so often been left out of the current mainframe of intellectual property rights. Whereas, the majority view of IPRs tends to focus on the rights of the individual and their protection as such, indigenous cultures are inherently built over centuries and across generations on communal understandings and organic exchanges of knowledge, making it practically impossible to ascribe the ownership of a certain set of IPRs to one or a few individuals.

Apache Dancers at the exhibit ‘Dignity – Tribes in Transition’. United States Mission Geneva Photo: Eric Bridiers. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via US Mission Geneva Flickr.

As Professor Anaya articulates and the other contemplate, the similarities between the inadequacies of the protection of tangible rights of indigenous peoples (e.g. indigenous land rights) and that of their intangible rights protection (including intellectual property rights) tend to stem from a common source – the failure to acknowledge the “inherent logic of indigenous peoples’ world views”.

Perhaps the solutions lie not just in finding ways to include indigenous intellectual property rights in current IPR regimes, but through the facilitation of an entire paradigm shift to capture the nuances of these issues both effectively and precisely. How, for instance, can indigenous IPRs be valued commercially, and how may adequate compensation models be developed in exchange for the commercial use of these rights? A key to increasing the recognition of the inherent value of indigenous IPRs within their traditional cultural settings may lie in developing methods to properly value this worth in tangible terms. What seems necessary is a model to adequately measure the significance of indigenous IPRs, starting at the source (the indigenous community), and finding ways of translating this value into benefit systems that can be returned to the communities from which the IPRs were sourced. Hence recognition is attributed to the crucial part these IPRs play within the cultures from which they are derived.

The strength of intellectual property law lies in its ability to meet the demands of a frenetically changing world, thus affording it vast amounts of power in shaping the law of the future; but this brings with it the challenge – can that power be harnessed to adequately protect rights of the past? Even if the answer is in the affirmative, it does not necessarily follow that the purpose of intellectual property rights protection should be to reduce IPRs to protectable commodities solely for the purpose of commercial exploitation. Protection of IPRs might be secured for any number of reasons, including the recognition of the right for ownership of those rights to be retained within the community. IPRs thus have the capacity to function both as shields and swords. Such weaponry however brings with it obligations: “With great power, comes great responsibility.”

Keri Johnston and Marion Heathcote are the guest editors of the Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice special issue on “The Quest for ‘Real’ Protection for Indigenous Intangible Property Rights”. The authors would like to thank Mekhala Chaubal, student-at-law, for her assistance. It is reassuring to know that a new generation of lawyers is willing and able. Keri AF Johnston is managing partner of Johnston Law in Toronto and Marion Heathcote is a partner with Davies Collison Cave in Sydney.

The Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice (JIPLP) is a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to intellectual property law and practice. Published monthly, coverage includes the full range of substantive IP topics, practice-related matters such as litigation, enforcement, drafting and transactions, plus relevant aspects of related subjects such as competition and world trade law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The quest for ‘real’ protection for indigenous intangible property rights appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOvercoming everyday violence [infographic]A doctrine of ‘market sovereignty’ to solve international law issues on the Internet?Western (and other) perspectives on Ukraine

Related StoriesOvercoming everyday violence [infographic]A doctrine of ‘market sovereignty’ to solve international law issues on the Internet?Western (and other) perspectives on Ukraine

Parent practices: change to develop successful, motivated readers

Oxford University Press is a proud sponsor of the 2014 World Literacy Summit, taking place this April. The Summit will provide a central platform for champions of literacy from around the globe to come together and exchange points of view, knowledge, and ideas. We asked literacy experts Jamie Zibulsky and Anne E. Cunningham to discuss the importance of literacy on this occasion.

By Jamie Zibulsky and Anne E. Cunningham

Being literate involves much more than the ability to sound out the words on a page, but acquiring that skill requires years of development and exposure to the world of words. Once children possess the ability to sound out words, read fluently, and comprehend the words on a page, they have limitless opportunities to learn about new concepts, places, and people. To say that becoming a reader gives one the power to change is an understatement. In fact, attempting to detail the many ways that reading can foster personal growth and development without writing an entire book on the topic is truly challenging!

Children’s capacities to build the many skills required to access text are, to a large degree, determined by their environments. Parents and teachers play a critical role in introducing children to the sounds of words, the print on a page, the ideas and concepts that provide the background for comprehension, and the structure of stories. For these reasons, if we want to ensure that all children have the opportunity to become successful, motivated readers, we need to think about the power the adults in their lives have to change children’s literacy trajectories.

The language and literacy experiences of young children are largely social in nature, and both the environment and the adults that care for them initially guide children’s development. In fact, psychologists point out that language development occurs first as a social act between people and then later as an individual act, as we gradually internalize the directions, strategies, and advice of more skilled others by verbalizing them to ourselves. Similarly, to make sense of the written symbols used to convey any language, children need guidance from the adults in their lives. Talking and reading together with children is a powerful way to help them gain entry to the world of words, and doing so most effectively may require parents to change their current practices.

The kids reading together. Photo by Valerie Everett. CC BY-SA 2.0 via valeriebb Flickr.

Here are some powerful tips that families can use to make shared reading time supportive and effective for young children learning a variety of languages:

Let your child take the lead during reading time. We often think of reading together as a time when a parent reads a story to a child straight through, page by page. Instead, let your child take more of an active role by using the pictures to narrate the story, answering your questions about aspects of the book, or sounding out some words independently. This may feel like you and your child are swapping your regular reading roles. And that’s exactly what we want you to do. Even before children are able to read independently, they are ready to be active participants in book reading experiences. Giving them these opportunities helps children build stronger language skills, and provides some insight into their skills and interests.

Give your child hints, rather than providing the answer, when he is struggling. This support helps the child solve the problem in a way that allows him to feel competent and to learn from the situation, but also lets the adult to guide the child through the problem-solving process. In addition, it gives him the chance to successfully experience tasks he would not have been able to tackle alone, or that would otherwise make him become frustrated and give up.

Identify your child’s strengths, and those reading skills he or she already possesses. Providing experiences that build on the skills your child already possesses will allow her to enhance her learning capacities. If you think about almost any activity you expect your child to complete, you can probably think back to a time when you completed that activity for her. Gradually, over time, she took more responsibility and was able to do more of the task independently. This is not only true for activities like getting dressed and tying shoes, but also for language and literacy tasks, as well as tasks that require memory and concentration.

Label the behavior that you want your child to display, and praise it specifically. Praise and encouragement from parents is a powerful motivational tool. Because shared reading is such a social activity, much of your child’s initial pleasure in reading together may come not primarily from the stories that he hears, but from the joy of sitting in your lap and spending time together. Your child values the time you spend together and will, over time, begin to value the books in front of him and the strategies needed to make sense of them. You can help him build his reading motivation by praising specific skills he displays, like listening carefully, sounding out words, and making great predictions.

Each of these tips helps set the stage for a successful shared reading experience, but may require change on the part of parents to help foster a powerful and engaged reader. These changes, though, help empower children to identify themselves as readers from the time they are young. And this strong foundation prepares them for so many challenges they will face in the future, so doing everything one can to raise a successful, motivated reader is one of the best gifts a parent can give any child.

Anne E. Cunningham, Ph.D. and Jamie Zibulsky, Ph.D. are the authors of Book Smart: How to Develop and Support Successful, Motivated Readers. Anne Cunningham is Professor of Cognition and Development at University of California Berkeley Graduate School of Education and Jamie Zibulsky is Assistant Professor of Psychology at Fairleigh Dickinson University. Learn more at Book Smart Family.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Parent practices: change to develop successful, motivated readers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCommon Core Standards, universal pre-K, and educating young readersBe Book Smart on National Reading DayWhat is clinical reasoning?

Related StoriesCommon Core Standards, universal pre-K, and educating young readersBe Book Smart on National Reading DayWhat is clinical reasoning?

What is clinical reasoning?

It is easy to delineate what clinical decision-making is not. It is not evidence-based medicine; it is not critical thinking; it is not eminence-based medicine; it is not one of many other of its many attributes; and it stands alone, with many contributions from all these fields. It is far more difficult to characterize what clinical reasoning is and very difficult to define.

But the clinicians among us deal with it every day and, I think, recognize it when we do it and observe it.

Evidence-based medicine is a mantra. But it is a difficult mantra. No one wants to say, “I reject evidence: I am a quack.” But it is complex and difficult. Evidence from the research in psychiatry comes from clinical trials, neural imaging, genetics, and other fields. Clinical trials can be read and understood. They are viewed as the sine qua non of evidence-based medicine. But the trials are conducted on patients without any other clinical conditions and are usually of very brief duration. The clinician, on the other hand, is often dealing with patients with many other syndromes and a great deal of chronicity. It is hard to make a claim, based on evidence, that the excellent clinical trial of Drug X applies to such a patient.

Neural imaging is far more difficult. It is a very complex methodology, and psychiatric studies which use it include as investigators physicists, neuroradiologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and others. The work is so interdisciplinary that, usually, none of the authors understands the entire paper. This is a huge question, I believe, for philosophy of science. Most of these studies are conducted on a small N, with very complex statistics, and few have been replicated. What is the clinician to do with them? Many clinicians make the assumption that the spectroscopic findings somehow translate to clinical “facts”, but that is generally not a safe assumption, nor one on which to base treatment decisions as yet.

Similarly, genetics studies are also very difficult, especially because of the completely central statistical analyses which are necessary to understanding the papers — and which few clinicians have time to read or sufficient training to understand.

Many clinicians try hard to be “evidence-based”, but it is very difficult for anyone to truly sort through the evidence in order to make an on-the-spot clinical decision which will affect the health of a patient. Some journals and digests attempt to do this in order to assist clinicians, but reliance on them implies a trust in their employees which may or may not be justified.

For all these reasons, “eminence-based” reasoning has some attraction. The clinician should base his decisions on recommendations of experts rather than her or his own scrutiny of the literature. But many of the experts are quite old and have been removed from day-to-day clinical interactions for many years.

A couple of years ago I encountered a young patient with a severe, atypical depression. My immediate response was, “This patient reminds me of another patient, who had a superb response to a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, so perhaps I should try one.” This is a poor rationale for a clinical decision until it is parsed, but, in fact, the young man’s depression was categorically similar to that of the other patient, neither had responded to more traditional treatment, and there was a supportive literature for the use of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor in this type of clinical situation. The patient in fact responded well to this treatment. I believe that this type of clinical decision-making is common and that it is based on science and evidence, though sometimes the science and evidence are not immediately apparent unless the clinician thinks about it.

Clinical reasoning requires consideration of the evidence and efforts to assess it, good critical thinking, and also, in my view, the experience of interacting with and treating many patients over time. It is not a laboratory exercise but one which involves a doctor, a patient, and the world around them.

Lloyd A. Wells, Ph.D., M.D., is Consultant Emeritus at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, USA. While there, he chaired the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for nineteen years and was the Department of Psychiatry’s Education Chair for twelve years. He is co-editor, with Christian Perring, of Diagnostic Dilemmas in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Wooden Sculpture of Science Genetics, by epSos.de, CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Sorrowing Old Man, by Vincent van Gogh, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What is clinical reasoning? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA conversation with Alberto GallacePagán’s planarians: the extraordinary world of flatwormsDementia on the beach

Related StoriesA conversation with Alberto GallacePagán’s planarians: the extraordinary world of flatwormsDementia on the beach

April 12, 2014

The Mexican-American War and the making of American identity

Few Americans today would have difficulty imagining a United States where the citizens disagree over the wisdom of immigration, question the degree to which Mexicans can be fully American, and dispute about the value of religious pluralism. But what if the America in question was not that of 2014 but rather the 1830s and 1840s? Along with being a high point of anti-Catholic nativism, these two decades witnessed the Texas Revolution, the US annexation of Texas, violence in US cities against Catholic immigrants, and the Mexican-American War. As Americans struggled to negotiate their identity as a people in terms of race, religion, and political culture, the war with Mexico clarified and for one century afterward cemented American identity as a Protestant, Anglo-Saxon republic.

Manifest Destiny held that American Anglo-Saxons, by reason of their cultural and racial superiority, were destined to overtake the western hemisphere. This Anglo-Saxonism was not so much based on attributes like skin color, as it was on unique attitudinal traits that predisposed Anglo-Saxons to be the most effective guardians of liberty. From this innate love of freedom had sprung Protestantism and republicanism—the religion and government for free men.

While the majority of Americans condemned a series of mob attacks against Catholic convents, churches, and schools in Boston and in Philadelphia, they nevertheless agreed with nativists that Catholicism was incompatible with representative—or what they called, “republican”—government. Politically unstable Mexico, they said, was proof of this.

When the United States and Mexico went to war in 1846, doubts quickly surfaced about the patriotic fortitude of foreign-born, Irish-Americans in a war against a Catholic nation. Irish immigrant soldier John Riley fled the US army on 12 April 1846, about two weeks before the first battle of the war. American authorities suspected that in September 1846 he was the leader of a group of mostly Irish and Catholic deserters at the Battle of Monterey. These rumors were true, and in late 1847 the US Army captured the San Patricios, or Saint Patrick Battalion. In the United States, debate ensued over the San Patricios’ motives and goals. At stake was the question of immigrant Catholic loyalty to the United States.

So, what were the factors in the San Patricio desertion? Abuse by nativist American officers was one of them. For a given crime, officers would sometimes merely demote native-born soldiers while imprisoning, whipping, or dishonorably discharging foreign-born men. Atrocities, church looting, and violence against priests by some American troops aggravated the fear that the Protestant United States was attacking not just Mexico but the Catholic faith.

The causes of this desertion, however, were not a one-sided affair. Mexican propaganda enticed Americans to leave their ranks. One broadside was addressed to “Catholic Irishmen” by General Antonio López de Santa Anna but the writer probably was Riley. It beckoned Americans to “Come over to us; you will be received under the laws of that truly Christian hospitality and good faith which Irish guests are entitled to expect and obtain from a Catholic nation.” It then asked, “Is religion no longer the strongest of all human bonds? Can you fight by the side of those who put fire to your temples in Boston and Philadelphia”?

It is most accurate, then, to say that while religion was involved in the defection, most of the San Patricios deserted because of intense abuse by officers, not for love of Mexico or the Catholic Church. This includes Riley. In all, 27 San Patricios were hanged.

Hanging of the San Patricios following the Battle of Chapultepec. Painted in the 1840s by Sam Chamberlain. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The capture and punishment of the San Patricios may have been dramatic, but the questioning of Catholic loyalty was just one small part of religion’s interplay with the war. Religious rhetoric constituted an integral piece of nearly every major argument for or against the war. This civil religious discourse was so universally understood that recruiters, politicians, diplomats, journalists, soldiers, evangelical activists, abolitionists, and pacifists used it. It helped shape everything from debates over annexation to the treatment of enemy soldiers and civilians. Religion also was the primary tool used by Americans to interpret Mexico’s fascinating but alien culture.

More than any other event during the nineteenth century, the Mexican-American War clarified the anti-Catholic assumptions inherent to American identity. At the same time, from the crucible of war emerged an American civil religion that can only be described as a triumphalist Protestant and white, anti-Catholic republicanism. That civil religion lasted well into the twentieth century. The degree to which it is still alive today in current debates over Latino immigration is debatable, but one can hardly miss the resemblance and connection between the issues of the 1840s and those of 2014.

John C. Pinheiro is Associate Professor of History at Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He has written two books on the Mexican-American War. His newest book is Missionaries of Republicanism: A Religious History of the Mexican-American War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Mexican-American War and the making of American identity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDoes torture really (still) matter?Disposable captivesRoberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetry

Related StoriesDoes torture really (still) matter?Disposable captivesRoberto Bolaño and the New York School of poetry

Does torture really (still) matter?

The US military involvement in Iraq has more or less ended, and the war in Afghanistan is limping to a conclusion. Don’t the problems of torture really belong to the bad old days of an earlier administration? Why bring it up again? Why keep harping on something that is over and done with? Because it’s not over, and it’s not done with.

Torture is still happening. Shortly after his first inauguration in 2009, President Obama issued an executive order forbidding the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques” and closing the CIA’s so-called “black sites.” But the order didn’t end “extraordinary rendition”—the practice of sending prisoners to other countries to be tortured. (This is actually forbidden under the UN Convention against Torture, which the United States signed in 1994.) The president’s order didn’t close the prison at Guantánamo, where to this day, prisoners are held in solitary confinement. Periodic hunger strikes are met with brutal force feeding. Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel described the experience in a New York Times op-ed in April 2013:

I will never forget the first time they passed the feeding tube up my nose. I can’t describe how painful it is to be force-fed this way. As it was thrust in, it made me feel like throwing up. I wanted to vomit, but I couldn’t. There was agony in my chest, throat and stomach. I had never experienced such pain before.

Nor did Obama’s order address the abusive interrogation practices of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) which operates with considerably less oversight than the CIA. Jeremy Scahill has ably documented JSOC’s reign of terror in Iraq in Dirty Wars: The World Is a Battlefield. At JSOC’s Battlefield Interrogation Facility at Camp NAMA (which reportedly stood for “Nasty-Ass Military Area”) the motto—prominently displayed on posters around the camp—was “No blood, no foul.”

Torture also continues daily, hidden in plain sight, in US prisons. It is no accident that the Army reservists responsible for the outrages at Abu Ghraib worked as prison guards in civilian life. As Spec. Charles A. Graner wrote in an email about his work at Abu Ghraib, “The Christian in me says it’s wrong, but the corrections officer in me says, ‘I love to make a grown man piss himself.’” Solitary confinement and the ever-present threat of rape are just two forms of institutionalized torture suffered by the people who make up the world’s largest prison population. In fact, the latter is so common that on TV police procedurals like Law & Order, it is the staple threat interrogators use to prevent a “perp” from “lawyering up.”

We still don’t have a full, official accounting. As yet we have no official government accounting of how the United States has used torture in the “war on terror.” This is partly because so many different agencies, clandestine and otherwise, have been involved in one way or another. The Senate Intelligence Committee has written a 6,000-page report just on the CIA’s involvement, which has never been made public, although recent days have seen moves in this direction. Nor has the Committee been able to shake loose the CIA’s own report on its interrogation program. Most of what we do know is the result of leaks, and the dogged work of dedicated journalists and human rights lawyers. But we have nothing official, on the level, say, of the 1975 Church Committee report on the CIA’s activities in the Vietnam War.

Frustrated because both Congress and the Obama administration seemed unwilling to demand a full accounting, the Constitution Project convened a blue-ribbon bipartisan committee, which produced its own damning report. Members included former DEA head Asa Hutchinson, former FBI chief William Sessions, and former US Ambassador to the United Nations Thomas Pickering. The report reached two important conclusions: (1) “[I]t is indisputable that the United States engaged in the practice of torture,” and (2) “[T]he nation’s highest officials bear some responsibility for allowing and contributing to the spread of torture.”

No high-level officials have been held accountable for US torture. Only enlisted soldiers like Charles Graner and Lynndie England have done jail time for prisoner abuse in the “war on terror.” None of the “highest officials” mentioned in the Detainee Task Force report (people like Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, and George W. Bush) have faced any consequences for their part in a program of institutionalized state torture. Early in his first administration, President Obama argued that “nothing will be gained by spending our time and energy laying blame for the past,” but this is not true. Laying blame for the past (and the present) is a precondition for preventing torture in the future, because it would represent a public repudiation of the practice. What “will be gained” is the possibility of developing a public consensus that the United States should not practice torture any longer. Such a consensus about torture does not exist today.

Tolerating torture corrupts the moral character of the nation. We tend to think of torture as a set of isolated actions—things desperate people do under desperate circumstances. But institutionalized state torture is not an action. It is an ongoing, socially-embedded practice. It requires an infrastructure and training. It has its own history, traditions, and rituals of initiation. And—importantly—it creates particular ethical habits in those who practice it, and in any democratic nation that allows it.

Since the brutal attacks of 9/11/2001, people in this country have been encouraged to be afraid. Knowing that our government has been forced to torture people in order to keep us safe confirms the belief that each of us must be in terrible danger—a danger from which only that same government can protect us. We have been encouraged to accept any cruelty done to others as the price of our personal survival. There is a word for the moral attitude that sets personal safety as its highest value: cowardice. If as a nation we do not act to end torture, if we do not demand a full accounting from and full accountability for those responsible, we ourselves are responsible. And we risk becoming a nation of cowards.

Rebecca Gordon received her B.A. from Reed College and her M.Div. and Ph.D. in Ethics and Social Theory from Graduate Theological Union. She teaches in the Department of Philosophy and for the Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good at the University of San Francisco. She is the author of Letters From Nicaragua, Cruel and Usual: How Welfare “Reform” Punishes Poor People, and Mainstreaming Torture: Ethical Approaches in the Post-9/11 United States.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Does torture really (still) matter? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOvercoming everyday violence [infographic]Disposable captivesA conversation with Alberto Gallace

Related StoriesOvercoming everyday violence [infographic]Disposable captivesA conversation with Alberto Gallace

Overcoming everyday violence [infographic]

The struggle for food, water, and shelter are problems commonly associated with the poor. Not as widely addressed is the violence that surrounds poor communities. Corrupt law enforcement, rape, and slavery (to name a few), separate families, destroys homes, ruins lives, and imprisons the poor in their current situations. Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros, authors of The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence, have experience in the slums, back alleys, and streets where violence is a living, breathing being — and the work to turn those situations around. Delve into the infographic below and learn how solutions like media coverage and business intervention have begun to positively change countries like the Congo, Cambodia, Peru, and Brazil.

Download a copy of the infographic.

Gary A. Haugen and Victor Boutros are co-authors of The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence. Gary Haugen is the founder and president of International Justice Mission, a global human rights agency that protects the poor from violence. The largest organization of its kind, IJM has partnered with law enforcement to rescue thousands of victims of violence. Victor Boutros is a federal prosecutor who investigates and tries nationally significant cases of police misconduct, hate crimes, and international human trafficking around the country on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email .or RSS.

The post Overcoming everyday violence [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe relationship between poverty and everyday violenceA world in fear [infographic]Make the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting: pass H.R. 4085

Related StoriesThe relationship between poverty and everyday violenceA world in fear [infographic]Make the tax system safe for interstate telecommuting: pass H.R. 4085

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers