Oxford University Press's Blog, page 827

April 5, 2014

A doctrine of ‘market sovereignty’ to solve international law issues on the Internet?

One of the most prominent features of jurisdictional rules is a focus on the location of actions. For example, the extraterritorial reach of data privacy law may be decided by reference to whether there was the offering of goods or services to EU residents, in the EU.

Already in the earliest discussions of international law and the Internet it was recognised that this type of focus on the location of actions clashes with the nature of the Internet – in many cases, locating an action online is a clumsy legal fiction burdened by a great degree of subjectivity.

I propose an alternative: a doctrine of ‘market sovereignty’ determined by reference to the effective reach of ‘market destroying measures’. Such a doctrine can both delineate, and justify, jurisdictional claims in relation to the Internet.

It is commonly noted that the real impacts of jurisdictional claims in relation to the Internet is severally limited by the intrinsic difficulty of enforcing such claim. For example, Goldsmith and Wu note that:

“[w]ith few exceptions governments can use their coercive powers only within their borders and control offshore Internet communications only by controlling local intermediaries, local assets, and local persons” (emphasis added)

However, I would advocate the removal of the word ‘only’. From what unflatteringly can be called a cliché, there is now a highly useful description of a principle well-established at least 400 years ago.

The word ‘only’ gives the impression that such powers are of limited significance for the overall question, which is misleading. The power governments have within their territorial borders can be put to great effect against offshore Internet communications. A government determined to have an impact on foreign Internet actors that are beyond its directly effective jurisdictional reach may introduce what we can call ‘market destroying measures’ to penalise the foreign party. For example, it may introduce substantive law allowing its courts to, due to the foreign party’s actions and subsequent refusal to appear before the court, make a finding that:

that party is not allowed to trade within the jurisdiction in question;

debts owed to that party are unenforceable within the jurisdiction in question; and/or

parties within the control of that government (e.g. residents or citizens) are not allowed to trade with the foreign party.

In light of this type of market destroying measures, the enforceability of jurisdictional claims in relation to the Internet may not be as limited as it may seem at a first glance.

In this context, it is also interesting to connect to the thinking of 17th century legal scholars, exemplified by Hugo de Groot (better known as Hugo Grotius). Grotius stated that:

“It seems clear, moreover, that sovereignty over a part of the sea is acquired in the same way as sovereignty elsewhere, that is, [...] through the instrumentality of persons and territory. It is gained through the instrumentality of persons if, for example, a fleet, which is an army afloat, is stationed at some point of the sea; by means of territory, in so far as those who sail over the part of the sea along the coast may be constrained from the land no less than if they should be upon the land itself.”

A similar reasoning can usefully be applied in relation to sovereignty in the context of the Internet. Instead of focusing on the location of persons, acts or physical things – as is traditionally done for jurisdictional purposes – we ought to focus on marketplace control – on what we can call ‘market sovereignty’. A state has market sovereignty, and therefore justifiable jurisdiction, over Internet conduct where it can effectively exercise ‘market destroying measures’ over the market that the conduct relates to. Importantly, in this sense, market sovereignty both delineates, and justifies, jurisdictional claims in relation to the Internet.

The advantage market destroying measures have over traditional enforcement attempts could escape no one. Rather than interfering with the business operations worldwide in case of a dispute, market destroying measures only affect the offender’s business on the market in question. It is thus a much more sophisticated and targeted approach. Where a foreign business finds compliance with a court order untenable, it will simply have to be prepared to abandon the market in question, but is free to pursue business elsewhere. Thus, an international agreement under which states undertake to only apply market destroying measures and not seek further enforcement would address the often excessive threat of arrests of key figures, such as CEOs, of offending globally active Internet businesses.

Professor Dan Jerker B. Svantesson is Managing Editor of the journal International Data Privacy Law. He is author of Internet and E-Commerce Law, Private International Law and the Internet, and Extraterritoriality in Data Privacy Law. Professor Svantesson is a Co-Director of the Centre for Commercial Law at the Faculty of Law (Bond University) and a Researcher at the Swedish Law & Informatics Research Institute, Stockholm University.

Combining thoughtful, high level analysis with a practical approach, International Data Privacy Law has a global focus on all aspects of privacy and data protection, including data processing at a company level, international data transfers, civil liberties issues (e.g., government surveillance), technology issues relating to privacy, international security breaches, and conflicts between US privacy rules and European data protection law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Ethernet cable with a padlock symbolising internet security. © SKapl via iStockphoto.

The post A doctrine of ‘market sovereignty’ to solve international law issues on the Internet? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineElinor and Vincent Ostrom: federalists for all seasonsIs there a “cyber war” between Ukraine and Russia?

Related StoriesWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineElinor and Vincent Ostrom: federalists for all seasonsIs there a “cyber war” between Ukraine and Russia?

April 4, 2014

Is Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?

The Amanda Knox case is complex in view of Italy’s complicated procedure in matters involving serious crimes. These crimes are tried before a special court called the Court of Assizes. These courts have two professional judges and six lay judges, much like a jury in Anglo-American cases. But, in Italy, the lay judges sit alongside the ordinary judges and decide on questions of law and fact. In the Italian system, a conviction or an acquittal can be appealed to the Court of Appeals, which can either examine the merits of the case and hold a new hearing on the facts or decide on the proper application of law, or both. It can also remand a case to the trial court for a new trial. Such appeals are trials de novo, but the Appeals Court of Assizes seldom hears witnesses again, though it can. Usually, it decides on the record both questions of facts and law. Any case can be appealed to the Court of Cassation. If any court certifies there is a constitutional question at issue, that court can refer the case to the Constitutional Court. This complex procedure is designed to benefit the rights of the accused.

The Facts and the Procedural History of the Case

Amanda Knox, a US citizen, was a student at the University of Perugia in November 2007 when she was arrested for the murder of her British roommate, Meredith Kercher. The two women were studying in Perugia, Italy. Meredith Kercher was found dead in the apartment she shared with Knox with her throat slit and with evidence of a sexual assault. Knox, her Italian boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito, and Rudy Guede from the Ivory Coast, an acquaintance of the couple, were all charged with murder and sexual violence.

2009 – The Perugia Trial Court of Assizes convicted Amanda Knox for murder and slander.

All three pled innocent but were convicted by the Assizes Trial Court in December of 2009 for murder and sexual violence. Amanda Knox was also convicted for slander, having accused Mr. Patrick Lumumba (the owner of the bar in which she occasionally worked) as the murderer. Amanda Knox was sentenced to 26 years in jail, Raffaele Sollecito to 25 years, and Rudy Guede (who had opted for the accelerate procedure) to 30 years (a conviction now affirmed by the Italian Court of Cassation, but with a reduction of the sentence to 16 years).

The convictions of Knox and Sollecito were due to the court not being convinced of Knox’s story that she and Sollecito were not in the apartment the night of the murder but were instead at Sollecito’s apartment. Witnesses testified that they had seen Knox and Sollecito near the apartment where Meredith Kercher’s body was found at around 23.00 hours; and the main scientific exhibits—specifically, Exhibit 36, a 6.5 inch knife found in Sollecito’s apartment with Knox’s DNA on the handle and Meredith Kercher’s DNA on the blade (low quantity of DNA)—were compatible with the wounds according to court experts, and Exhibit 165, a clasp, was found on the murder scene with Meredith Kercher’s DNA and Sollecito’s DNA.

2011 – Amanda Knox appealed to the Appeals Court of Assizes of Perugia, which acquitted her of murder and affirmed her conviction for slander.

In October 2011, the Appeals Court of Assizes of Perugia acquitted both Knox and Sollecito after questions were raised by the defense regarding the protocol followed by the Italian police while gathering the forensic evidence that was used to convict them in 2009. The court’s judgment was also based on new scientific examinations that were previously requested by the defense during the first trial but were not authorized by the trial court. This evidence, according to the defense, would have disproved the presence of Knox and Sollecito at the crime scene. The appeals court concluded that the evidence that proved persuasive to the Perugia Trial Court of Assizes was obtained in a contaminated environment. More specifically, the appeals court concluded that (1) certain footprints initially attributed to Sollecito were also compatible with the size of Rudy Guede’s feet and (2) subsequent analysis on the 6.5 inch kitchen knife supposedly used to slit Meredith Kercher’s throat showed that the kitchen knife did not contain Knox’s DNA and that the kitchen knife could not have been the murder weapon.

2013 – The Prosecution appealed that decision to the Court of Cassation (Supreme Court), which remanded the case to the Appeals Court of Assizes of Florence.

Following the acquittal by the first appeals court in 2011, Knox left Italy and returned to the United States. In March 2013, the Prosecution in the Knox and Sollecito cases appealed to the Court of Cassation, Italy’s Supreme Court, which remanded the case to the Appeals Court of Assizes in Florence for reconsideration on the basis that there were discrepancies in testimony, inconsistencies, omissions, and contradictions in the ruling of the Appeals Court of Assizes of Perugia in 2011. The Court of Cassation upheld each of the grounds raised by the Perugia Chief Prosecutor. The Court of Cassation concluded that the Assizes Court of Appeals of Perugia, which reversed the murder conviction for Amanda Knox in 2011, had weighed the evidence in an inconsistent and piecemeal fashion.

2014 – The Appeals Court of Assizes of Florence overturned the acquittal by the Court of Appeals of Perugia for murder and affirmed the previous conviction of the trial court for murder and slander.

The case was then assigned to the Appeals Court of Assizes of Florence, which, on 30 January 2014, overturned the acquittals of the Perugia Assizes Court of Appeal based on the Court of Cassation’s previous judgment. This appeals court convicted Knox in absentia and sentenced her to 28 years and six months of imprisonment and sentenced Sollecito to 25 years of imprisonment. The Presiding Judge of the Florence Court has 90 days as of January 30, 2014 to write his judgment (with reasons) on the ruling. Lawyers for Knox and Sollecito have stated that as soon as the judgment is filed, they will appeal it to the Court of Cassation. The judgment is not final until the Court of Cassation rules on the eventual appeal of Knox and Sollecito.

Extradition from the United States to Italy

Italy is one of the few countries with this complex procedure, which it does not consider to be in violation of the constitutional prohibition of ne bis in idem (double jeopardy) reflected in article 649 of the Italian Code of Criminal procedure. The prohibition of ne bis in idem is included in the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, but, so far, the European Court for Human Rights (ECHR) has not interpreted Italian law as violating the European Convention. Thus, the procedure described above has not been found to be in violation of ne bis in idem under the ECHR.

The 1983 U.S.–Italy Extradition Treaty states in article VI that extradition is not available in cases where the requested person has been acquitted or convicted of the “same acts” (in the English text) and the “same facts” (in the Italian text). Treaty interpretation needs to ascertain the intentions of the parties by relying on the plain language and meaning of the words. Italy’s law prohibiting ne bis in idem specifically uses the words stessi fatti, which are the same words used in the Italian version of article VI, meaning “same facts.” Because fatti, or “facts,” may include multiple acts, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals applied the test of “same conduct” in Sindona v. Grant, citing international extradition in US law and practice, based on this writer’s analysis.

Whatever the interpretation of article VI may be—“same act,” “same facts,” or the broader “same conduct”—Amanda Knox would not be extraditable to Italy should Italy seek her extradition because she was retried for the same acts, the same facts, and the same conduct. Her case was reviewed three times with different outcomes even though she was not actually tried three times. In light of the jurisprudence of the various circuits on this issue, it is unlikely that extradition would be granted.

The US Supreme Court can also make a constitutional determination under the Fifth Amendment of the applicability of double jeopardy to extradition cases, particularly with respect to a requesting state’s right to keep on reviewing its request for the same acts or facts in the hope of obtaining a conviction. But, no such interpretation was given to the Fifth Amendment in any extradition case to date. Surprising as it may be, neither the Supreme Court nor any Circuit Court has yet held that the Fifth Amendment’s “double jeopardy” provision applies to extradition. So far, double jeopardy defenses have been dealt with as they arise under the applicable treaty.

Conclusion: Amanda Knox’s extradition from the United States to Italy under existing jurisprudence is not likely.

M. Cherif Bassiouni is Emeritus Professor of Law at DePaul University where he taught from 1964-2012, where he was a founding member of the International Human Rights Law Institute (established in 1990), and served as President from 1990-2007, and then President Emeritus. He is also President, International Institute of Higher Studies in Criminal Sciences, Siracusa, Italy since 1989. He is the author of International Extradition: United States Law and Practice, Sixth Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: PERUGIA, ITALY – NOVEMBER 24: Amanda Knox is led away from Perugia’s Court of Appeal by police officers after the first session of her appeal against her murder conviction on November 24, 2010 in Perugia, Italy. © EdStock via iStockphoto.

The post Is Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineChina’s exchange rate conundrumThe economics of sanctions

Related StoriesWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineChina’s exchange rate conundrumThe economics of sanctions

Philosophy and its history

If you go into a mathematics class of any university, it’s unlikely that you will find students reading Euclid. If you go into any physics class, it’s unlikely you’ll find students reading Newton. If you go into any economics class, you probably won’t find students reading Keynes. But if you go a philosophy class, it is not unusual to find students reading Plato, Kant, or Wittgenstein. Why? Cynics might say that all this shows is that there is no progress in philosophy. We are still thrashing around in the same morass that we have been thrashing around in for over 2,000 years. No one who understands the situation would be of this view, however.

So why are we still reading the great dead philosophers? Part of the answer is that the history of philosophy is interesting in its own right. It is fascinating, for example, to see how the early Christian philosophers molded the ideas of Plato and Aristotle to the service of their new religion. But that is equally true of the history of mathematics, physics, and economics. There has to be more to it than that—and of course there is.

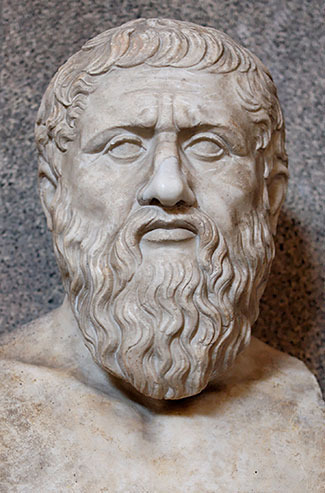

Plato, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican

Great philosophical writings have such depth and profundity that each generation can go back and read them with new eyes, see new things in them, apply them in different ways. So we study the history of philosophy that we may do philosophy.

One of my friends said that he regards the history of philosophy as rather like a text book of chess openings. Just as it is part of being a good chess player to know the openings, it is part of being a good philosopher to know standard views and arguments, so that they can pick them up and run with them.

There is a lot of truth in this analogy, but it sells the history of philosophy short as well. Chess is pursued within a fixed and determinate set of rules. These cannot be changed. But part of good philosophy (like good art) involves breaking the rules. Past philosophers may have played by various sets of rule; but sometimes we can see their projects and ideas can fruitfully (perhaps more fruitfully) be articulated in different frameworks—perhaps frameworks of which they could have had no idea—and so which can plumb their ideas to depths of which they were not aware.

Such is my view anyway. It is certainly one that I try to put into practice in my own teaching and writing. I find that using the tools of modern formal logic is a particularly fruitful way of doing this. Let me give a couple of examples.

One debate in contemporary metaphysics concerns how the parts of an object cooperate to produce the unity which they constitute. The problem was put very much on the agenda by the great 19th century German philosopher and logician Gottlob Frege. Consider the thought that Pheidippides runs. This has two parts, Pheidippides and runs. But the thought is not simply a list, <Pheidippides, runs>. Somehow, the two parts join together. But how? Frege’s answer (we do not need to go in the details) ran into apparently insuperable problems.

Aristotle went part of the way to solving the problem over two millenia ago. He suggested that there must be something which joins the parts together, the form (morphe), F, of the proposition. But that can be only a start, as a number of the Medieval European philosophers noted. For <Pheidippides, F, runs> seems just as much a list as our original one, so there has to be something which joins all these things together—and we are off on a vicious infinite regress.

The regress is broken if F is actually identical with Pheidippides and runs. For then nothing is required to join F and Pheidippides: they are the same. Similarly for F and runs. But Pheidippides and runs are obviously not identical. So identity is not, as logicians say, transitive. You can have a=b and b=c without a=c. It is not clear that this is even a coherent possibility. Yet it is, as modern techniques in a branch of logic called paraconsistent logic can be used to show. I spare you the details.

A quite different problem concerns the topic in modern metaphysics called grounding. Some things depend for their existence on others. Thus, a chair depends for its existence on the molecules which are its parts; these, in turn, depend for their existence on the atoms which are their parts; and so on.

It contemporary debates, it is standardly assumed that this process must ground out in some fundamental bedrock of reality. That idea was attacked by the great Buddhist philosopher Nāgārjuna (c. 2c CE), with a swathe of arguments. Ontological dependence never terminates: everything depends on other things. Again, it is not clear, Nāgārjuna’s arguments notwithstanding, that the idea is coherent. If everything depends on other things, we have an obvious regress; and, it might well be thought, the regress is vicious. In fact, it is not. It can be shown to be coherent by a mathematical model employing mathematical structures called trees, all of whose branches may be infinitely long. Again, I spare you the details.

Of course, in explaining my two examples, I have slid over many important complexities and subtleties. However, they at least illustrate how the history of philosophy provides a mine of ideas. The ideas are by no means dead. They have potentials which only more recent developments—in the case of my examples, in contemporary logic and mathematics—can actualize. Those who know only the present of philosophy, and not the past, will never, of course, see this. That is why philosophers study the history of philosophy.

Graham Priest was educated at St. John’s College, Cambridge, and the London School of Economics. He has held professorial positions at a number of universities in Australia, the UK, and the USA. He is well known for his work on non-classical logic, and its application to metaphysics and the history of philosophy. He is author of One: Being an Investigation into the Unity of Reality and of its Parts, including the Singular Object which is Nothingness.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images: Bust of Plato, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Image of a graph as mathematical structure showing all trees with 1, 2, 3, or 4 leaves, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosophy and its history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhen science stopped being literatureLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsA question of consciousness

Related StoriesWhen science stopped being literatureLogic and Buddhist metaphysicsA question of consciousness

A question of consciousness

By Susan Blackmore

The problem of consciousness is real, deep and confronts us any time we care to look. Ask yourself this question ‘Am I conscious now?’ and you will reply ‘Yes’. Then, I suggest, you are lured into delusion – the delusion that you are conscious all the time, even when you are not asking about it.

Now ask another question, ‘What was I conscious of a moment ago?’ This may seem like a very odd question indeed but lots of my students have grappled with it and I have spent years playing with it, both in daily life and in meditation. My conclusion? Most of the time I do not know what I was conscious of just before I asked.

Try it. Were you aware of that faint humming in the background? Were you conscious of the birdsong? Had you even noticed the loud drill in the distance that something in your brain was trying to block out? And that’s just sounds. What about the feel of your bottom on the chair? My experience is that whenever I look I find lots of what I call parallel backwards threads – sounds, touch, sights, that in some way I seem to have been listening to for some time – yet when I asked the question I had the odd sensation that I’ve only just become conscious of it.

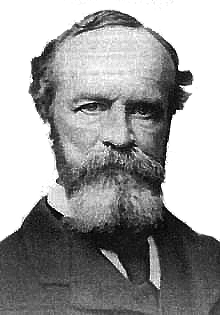

Back in 1890 William James (one of my great heroes of consciousness studies) remarked on the sounds of a chiming clock. You notice the chiming after several strikes. At that moment you can look back and count one, two, three, four and know that now it has reached five. But it was only at four that you suddenly became conscious of the sound.

William James

What’s going on?

This, I suggest, is just one of the many curious features of our minds that lead us astray. Whenever we ask ‘Am I conscious now? we always are, so we leap to the conclusion that there must always be something ‘in my consciousness’, as though consciousness were a container. I reject this idea. Instead, I think that most of the time our brains are getting on with their amazing job of processing countless streams of information in multiple parallel threads, and none of those threads is actually ‘conscious’. Consciousness is an attribution we make after the fact. We look back and say ‘This is what I was conscious of’ and there is nothing more to consciousness than that.

Are we really so deluded? If so there are two important consequences: One spiritual and one scientific.

Many contemplative and mystical traditions claim we are living in illusion; that we need to throw off the dark glasses of the false self who seems to be in control, who seems to have consciousness and free will; that if we train our minds through meditation and mindfulness we can see through the illusion and live in clearly awareness right here and now. I am most familiar with Zen and I love such sayings as, ‘Actions exist and also their consequences but the person that acts does not’. Wow! Letting go of the person who sees, thinks, and decides is not a trivial matter and many people find it outrageous that one would even want to try. Yet it is quite possible to live without assuming that you are consciously making the decisions – that you are a persisting entity that has consciousness and free will.

From the scientific point of view, throwing off these illusions would totally transform the ‘hard problem of consciousness’. This is, as Dave Chalmers, the Australian philosopher, describes it, the question of ‘how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experience’. This is a modern version of the mind-body problem. Almost everyone who works on consciousness agrees that dualism does not work. There cannot be a separate spirit or soul or persisting inner self that is something other than ordinary matter. The world cannot be divided, as Descartes famously thought, into mind and matter – subjective and objective, physical material and mental thoughts. Somehow the two must ultimately be one – But how? This ‘nonduality’ is what mystical traditions have long described, but it is also the hope that science is grappling with.

And something strange is happening in the science of consciousness. The last few decades have seen fantastic progress in neuroscience. Yet paradoxically this makes the problem of consciousness worse, not better. We now know that decisions are initiated in part of the frontal lobe, actions are controlled by areas as far apart as the motor cortex, premotor cortex and cerebellum, visual information is processed in multiple parallel pathways at different speeds without ever constructing a picture-like representation that could correspond to ‘the picture I see in front of my eyes’. The brain manages all these amazing tasks in multiple parallel processes. So what need is there for ‘me’? And what need is there for subjective experience? So what is it and why do we have it?

Perhaps inventing an inner conscious self is a convenient way to live; perhaps it simplifies the brain’s complex task of keeping us alive; perhaps it has some evolutionary purpose. Whatever the answer, I am convinced that all our usual ideas about mind and consciousness are false. We can throw them off in the way we live our lives, and we must throw them off if our science of consciousness is ever to make progress.

Susan Blackmore is a freelance writer, lecturer and broadcaster, and a Visiting Professor at the University of Plymouth. She is the author of Consciousness: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The post A question of consciousness appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs our language too masculine?Law and the quest for justiceOUP to publish Root Vegetables: A Very Short Introduction

Related StoriesIs our language too masculine?Law and the quest for justiceOUP to publish Root Vegetables: A Very Short Introduction

April 3, 2014

Western (and other) perspectives on Ukraine

Untangling recent and still-unfolding events in Ukraine is not a simple task. The western news media has been reasonably successful in acquainting its consumers with events, from the fall of Yanukovich on the back of intensive protests in Kiev, by those angry at his venality and signing a pact with Russia over one with the EU, to the very recent moves by Russia to annex Crimea.

However, as is perhaps inevitable where space is compressed, messages brief and time short, a habit of talking about Ukraine in binaries seems to be prevalent. Superficially helpful, it actually hinders a deeper understanding of the issues at hand – and any potential resolution. Those binaries, encouraged to some extent by the nature of the protests themselves (‘pro-Russian’ or ‘pro-EU/Western’), belie complex and important heterogeneities.

Ironically, the country’s name, taken by many to mean ‘borderland’, is one such index of underlying complexity. Commentators outside the mainstream news, including specialists like Andrew Wilson, have long been vocal in pointing out that the East-West divide is by no means a straightforward geographic or linguistic diglossia, drawn with a compass or ruler down the map somewhere east of Kiev, with pro-Western versus pro-Russian sentiment ‘mapped’ accordingly. Being a Russian-speaker is not automatically coterminous with following a pro-Russian course for Ukraine; and the reverse is also sometimes true. In a country with complex legacies of ethnic composition and ruling regime (western regions, before incorporation into the USSR, were ruled at different times in the modern period by Poland, Romania and Austria-Hungary), local vectors of identity also matter, beyond (or indeed, within) the binary ethnolinguistic definition of nationality.

The Bridge to the European Union from Ukraine to Romania. Photo by Madellina Bird. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via madellinabird Flickr.

Just as slippery is the binary used in Russian media, which portrays the old regime as legitimately elected and the new one as basically fascist, owing to its incorporation of Ukrainian nationalists of different stripes. First, this narrative supposes that being legitimately elected negates Yanukovich’s anti-democratic behaviours since that election, including the imprisonment of his main political opponent, Yulia Tymoshenko (whatever the ambivalence of her own standing in the politics of Ukraine). Second, the warnings about Ukrainian fascism call to mind George Bernard Shaw’s comment about half-truths as being especially dangerous. As well-informed Ukraine watchers like Andreas Umland and others have noted, overstating the presence of more extreme elements sets up another false binary as a way of deligitimising the new regime in toto. This is certainly not to say that Ukraine’s nationalist elements should escape scrutiny, and here we have yet another warning against false binaries: EU countries themselves may be manifestly less immune to voting in the far right at the fringes, but they still may want to keep eyes and ears open as to exactly what some of Ukraine’s coalition partners think and say about its history and heroes, the Jews, and much more.

So much for seeing the bigger picture, but events may well still take turns that few historians could predict with detailed accuracy. What we can see, at least, from the perspective of a maturing historiographic canon in the west, is that Ukraine is a country that demands a more sophisticated take on identity politics than the standard nationalist discourse allows – a discourse that has been in existence since at least the late nineteenth Century, and yet one which the now precarious-seeming European idea itself was set up to moderate.

Robert Pyrah is author of the recent review article, “From ‘Borderland’ via ‘Bloodlands’ to Heartland? Recent Western Historiography of Ukraine” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the English Historical Review. Robert Pyrah is a Member of the History Faculty and a Research Associate at the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages at the University of Oxford

First published in January 1886, The English Historical Review (EHR) is the oldest journal of historical scholarship in the English-speaking world. It deals not only with British history, but also with almost all aspects of European and world history since the classical era.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Western (and other) perspectives on Ukraine appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe economics of sanctionsIs there a “cyber war” between Ukraine and Russia?Elinor and Vincent Ostrom: federalists for all seasons

Related StoriesThe economics of sanctionsIs there a “cyber war” between Ukraine and Russia?Elinor and Vincent Ostrom: federalists for all seasons

China’s exchange rate conundrum

In late February, the slow appreciation of China’s currency was interrupted by a discrete depreciation from 6.06 to 6.12 yuan per dollar. Despite making front page headlines in the Western financial press, this 1% depreciation was too small to significantly affect trade in goods and services—and hardly anything compared to how floating exchange rates change among other currencies. Why then the great furor? And what should China’s foreign exchange policy be?

Foreign governments and influential pundits continually pressure China to appreciate the yuan in the mistaken belief that China’s large trade—read: saving—surplus would decline. This pressure is often called China bashing. And since July 2008 when the exchange rate was 8.28 yuan/dollar (and had been held constant for 10 years), the People’s Bank of China has more or less complied. So even the small depreciation was upsetting to foreign China bashers.

But an unintended consequence of sporadically appreciating the yuan, even by very small amounts, is (was) to increase the flow of “hot” money into China. With US short-term interest rates near zero, and the “natural” rate of interbank interest rate in the more robustly growing Chinese economy closer to 4%, an expected rate of yuan appreciation of just 3% leads to an “effective” interest rate differential of 7%. This profit margin is more than enough to excite the interest of carry traders: speculators who borrow in dollars, and try to circumvent the China’s exchange controls on financial inflows, to buy yuan assets. True, the 4% interest differential alone is enough to bring hot money into China (and into other emerging markets). But the monetary control problem is more acute when foreign economists and politicians complain that the Chinese currency is undervalued and the source of China’s current account surplus.

However, China’s current account surplus with the United States does not indicate that the yuan is undervalued. Rather the trade imbalance reflects a big surplus of saving over investment in China, and a bigger saving deficiency—as manifest in the ongoing fiscal deficit—in the United States. Indeed, the best index for tradable goods prices in China, the WPI, has been falling at about 1.5% per year—as if the yuan were slightly overvalued.

Although movements in exchange rates are not helpful in correcting net trade (saving) imbalances between highly open economies, they can worsen hot money flows. Thus, to minimize hot money flows, the People’s Bank of China (PBC) should simply stabilize the central rate at whatever it is today, say 6.1 yuan per dollar, to dampen the expectation of future appreciation. Upsetting the speculators by introducing more uncertainty into the exchange system, as with the temporary mini devaluation of the yuan in late February, is a distant second-best strategy for China to minimize inflows of hot money.

In addition, there is a second, less well recognized argument for keeping the yuan-dollar rate stable. In a rapidly growing economy like China’s with large gains in labor productivity, wage levels become quite flexible because wage growth is so high. That is, if wages grow at 15% instead of 10% per year (roughly the range of wage growth in China in recent years), the wage level moves up much faster. But wage growth better reflects productivity gains if the yuan/dollar rate is kept stable. If an employer (particularly in an export industry) fears future yuan appreciation, he will hesitate to increase workers’ pay by the full increase in their productivity. Otherwise, the firm could go bankrupt if the yuan did appreciate.

In addition, there is a second, less well recognized argument for keeping the yuan-dollar rate stable. In a rapidly growing economy like China’s with large gains in labor productivity, wage levels become quite flexible because wage growth is so high. That is, if wages grow at 15% instead of 10% per year (roughly the range of wage growth in China in recent years), the wage level moves up much faster. But wage growth better reflects productivity gains if the yuan/dollar rate is kept stable. If an employer (particularly in an export industry) fears future yuan appreciation, he will hesitate to increase workers’ pay by the full increase in their productivity. Otherwise, the firm could go bankrupt if the yuan did appreciate.

Thus, to better balance international competitiveness by having Chinese unit labor costs approach those in the mature industrial economies, China should encourage higher wage growth by keeping the yuan-dollar rate stable and so take away the threat of future appreciation. Notice that in the mature, not to say stagnant, industrial economies, macroeconomists typically assume that wages are inflexible or “sticky”. They then advocate flexible exchange rates to overcome wage stickiness. But for high-growth China, flexible wages become the appropriate adjusting variable if the exchange rate is stable. Unlike exchange appreciation, wages can grow quickly without attracting unwanted hot money inflows.

China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) has now accumulated over $4 trillion in exchange reserves because of continual intervention to buy dollars by the PBC. This stock of “reserves” is far in excess of any possible Chinese emergency need for international money, i.e., dollars. In addition, the act of intervention itself often threatens to undermine the PBC’s monetary control. When it buys dollars with yuan, the supply of base money in China’s domestic banking system expands and threatens price inflation or bubbles in asset prices such as real property.

Thus to sterilize the domestic excess monetary liquidity from foreign exchange interventions, the PBC frequently sells central bank bonds to the commercial banks—or raises the required reserves that the commercial banks must hold with the central bank—in order to dampen domestic credit expansion. Both sterilization techniques undermine the efficiency of the commercial banks’ important role as financial intermediaries between domestic savers and investors. Currently in China, this sterilization also magnifies the explosion in shadow banking by informal institutions not subject to reserve or capital requirements, or interest rate ceilings.

To better secure domestic monetary control, why doesn’t the PBC just give up intervening to set the yuan/dollar rate and let it float, i.e., be determined by the market? If the PBC withdrew from the foreign exchange market, the yuan would begin to appreciate without any well-defined limit. The upward pressure on the yuan has two principal sources:

Extremely low, near-zero, short interest rates in the United States, United Kingdom, the European Union, and Japan. With the more robust Chinese economy having naturally higher interest rates, unrestricted hot money would flow into China. Once the yuan began to appreciate, carry traders would see even greater short-term profits from investing in yuan assets.

China is an immature international creditor with underdeveloped domestic financial markets. Although China has a chronic saving (current account) surplus, it cannot lend abroad in its own currency to finance it.

Why not just lend abroad in dollars? Private (nonstate) banks, insurance companies, pension funds and so on, have a limited appetite for building up liquid dollar claims on foreigners when their own liabilities—deposits, insurance claims, and pension obligations— are in yuan. Because of this potential currency mismatch in private financial institutions, the PBC (which does not care about exchange rate risk) must step in as the international financial intermediary and buy liquid dollar assets on a vast scale as the counterpart of China’s saving surplus.

Even if there was no hot money inflow into China, the yuan would still be under continual upward pressure in the foreign exchanges because of China’s immature credit status (under the absence of a natural outflow of financial capital to finance the trade surplus). That is, foreigners remain reluctant to borrow from Chinese banks in yuan or issue yuan denominated bonds in Shanghai. This reluctance is worsened because of the threat from China bashing that the yuan might appreciate in the future. Thus the PBC has no choice but to keep intervening in the foreign exchanges to set and (hopefully) stabilize the yuan/dollar rate.

Superficially, the answer to China’s currency conundrum would seem be to fully liberalize its domestic financial markets by eliminating interest rate restrictions and foreign exchange controls. Then China could become a mature international creditor with natural outflows of financial capital to finance its trade surplus. Then the PBC need not continually intervene in the foreign exchanges.

This “internationalization” of the yuan may well resolve China’s currency conundrum in the long run. However, it is completely impractical—and somewhat dangerous—to try it in the short run. With near-zero short term interest rates in the mature industrial world, China would be completely flooded out by inflows of hot money, which would undermine the PBC’s monetary control and drive China’s domestic interest rates down much too far. China is in a currency trap. But within this dollar trap, China has shown that its GDP can grow briskly with even more rapid growth in wages—as long as the yuan-dollar rate remains reasonably stable. And China’s government must recognize that there is no easy way to spring the trap.

Ronald McKinnon is the William D. Eberle Professor Emeritus of International Economics at Stanford University, where he has taught since 1961. For a more comprehensive analysis of how the world dollar standard works, and China’s ambivalent role in supporting it, see Ronald McKinnon’s The Unloved Dollar Standard from Bretton Woods to the Rise of China, Oxford University Press (2013), and the Chinese translation from China Financial Publishing House (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Beijing skyline and traffic jam on ring road, China. Photo by coryz, iStockphoto.

The post China’s exchange rate conundrum appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe economics of sanctionsThe political economy of policy transitionsDementia on the beach

Related StoriesThe economics of sanctionsThe political economy of policy transitionsDementia on the beach

Dementia on the beach

Would you take a person with dementia to the beach?

This might not really be an idea you would think of. There are several possible constraints: difficulty with travel, for example, being one. And what if, having succeeded in getting the dementia sufferer there and back, the next day you asked if they enjoyed their day out and he or she just stared at you with a confused gaze as if to ask, ‘what are you talking about?’

If you think it makes little sense to take persons with dementia to the beach, it will surprise you that a nursing home in Amsterdam has built a Beach room. In this room, residents can enjoy the feeling of sitting in the sun with their bare feet in the sand. The room is designed to improve the well-being of these residents. The garden room at the centre of the home has recently been converted into a true ‘beach room’, complete with sand and a ‘sun’ which can be adjusted in intensity and heat output. A summer breeze blows occasionally and the sounds of waves and seagulls can be heard. The décor on the walls is several metres high, giving those in the room the impression that they are looking out over the sea. There are five or six chairs in the room where the older residents can sit. There are also areas of wooden decking on which wheelchairs can be parked. The designers have even managed to replicate the impression of sea air.

Multisensory ‘Beach room’ in the Vreugdehof care centre, Amsterdam.

Visits to the beach room appear to have calming and inspiring effects on residents of the nursing home. One male resident used to go to the beach often in the past and now, after initially protesting when his daughter collected him from his bedroom, feels calm and content in the beach room. His dementia hinders us from asking him whether he remembers anything from the past, but there does appear to be a moment of recognition of a familiar setting when he is in there.

Evidence is building through studies into the sensorial aspects of memorizing and reminiscing by frail older persons in nursing and residential homes. Several experimental studies have noted the positive effects of sense memories on the subjective well-being of frail older persons. For instance, one study showed that participants of a life review course including sensory materials had significantly fewer depressive complaints and felt more in control of their lives than the control group who had watched a film.

The Beach Room is an example of a multisensory room that emanates from a specific sensorial approach to dementia. The ‘Snoezelen’ approach was initiated in the Netherlands in the late 1970s. The word ‘Snoezelen’ is a combination of two Dutch words: ‘doezelen’ (to doze) and ‘snuffelen’ (to sniff ). Snoezelen takes place in a specially equipped room where the nature, quantity, arrangement, and intensity of stimulation by touch, smells, sounds and light are controlled. The aim of these multisensory interventions is to find a balance between relaxation and activity in a safe environment. Snoezelen has become very popular in nursing homes: around 75% of homes in the Netherlands, for example, have a room set aside for snoezelen activities.

On request by health care institutions, artists have taken up the challenge to design multisensory rooms or redesign the multisensory space of wards (e.g. distinguished by smells) and procedures (cooking and eating together instead of individual microwave dinners). Besides a few scientific evaluations, most evidence is actually acquired from collaborations of artists and health professionals at the moment. The senses are often a better way of communicating with people affected by deep dementia. Like the way that novelist Marcel Proust opened the joys of his childhood memories with the flavour of a Madeleine cake dipped in linden-blossom tea, these artistic health projects open windows to a variety of ways of using sensorial materials to reach unreachable people.

So, would you take a person with dementia to the beach? Yes, take them to the beach! It can evoke Proust effects and enhance their joy and well-being. Although, we still do not know what the Proust effect does inside the minds of people with dementia, we can oftentimes observe the result as an enhanced state of calmness with perhaps a little smile on their face. People with dementia who have lost so much of their quality of life can still experience moments of joy and serenity through their sense memories.

Cretien van Campen is a Dutch author, scientific researcher and lecturer in social science and fine arts. He is the founder of Synesthetics Netherlands and is affiliated with the Netherlands Institute for Social Research and Windesheim University of Applied Sciences. He is best known for his work on synesthesia in art, including historical reviews of how artists have used synesthetic perceptions to produce art, and studies of perceived quality of life, in particular of how older people with health problems perceive their living conditions in the context of health and social care services. He is the author of The Proust Effect: The Senses as Doorways to Lost Memories.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Multisensory ‘Beach room’ in the Vreugdehof care centre, Amsterdam. Photo: Cor Mantel, with permission from Vreugdehof.

The post Dementia on the beach appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brainFrom art to autism: a Q&A with Uta FrithWhen science stopped being literature

Related StoriesDopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brainFrom art to autism: a Q&A with Uta FrithWhen science stopped being literature

When science stopped being literature

We tend to think of ‘science’ and ‘literature’ in radically different ways. The distinction isn’t just about genre – since ancient times writing has had a variety of aims and styles, expressed in different generic forms: epics, textbooks, lyrics, recipes, epigraphs, and so forth. It’s the sharp binary divide that’s striking and relatively new. An article in Nature and a great novel are taken to belong to different worlds of prose. In science, the writing is assumed to be clear and concise, with the author speaking directly to the reader about discoveries in nature. In literature, the discoveries might be said to inhere in the use of language itself. Narrative sophistication and rhetorical subtlety are prized.

This contrast between scientific and literary prose has its roots in the nineteenth century. In 1822 the essayist Thomas De Quincey broached a distinction between the ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power.’ As De Quincey later explained, ‘the function of the first is to teach; the function of the second is to move.’ The literature of knowledge, he wrote, is left behind by advances in understanding, so that even Isaac Newton’s Principia has no more lasting literary qualities than a cookbook. The literature of power, on the other hand, lasts forever and draws out the deepest feelings that make us human.

The effect of this division (which does justice neither to cookbooks nor the Principia) is pervasive. Although the literary canon has been widely challenged, the university and school curriculum remains overwhelmingly dominated by a handful of key authors and texts. Only the most naive student assumes that the author of a novel speaks directly through the narrator; but that is routinely taken for granted when scientific works are being discussed. The one nineteenth-century science book that is regularly accorded a close reading is Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859). A number of distinguished critics have followed Gillian Beer’s Darwin’s Plots in attending to the narrative structures and rhetorical strategies of other non-fiction works – but surprisingly few.

It is easy to forget that De Quincey was arguing a case, not stating the obvious. A contrast between ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power’ was not commonly accepted when he wrote; in the era of revolution and reform, knowledge was power. The early nineteenth century witnessed remarkable experiments in literary form in all fields. Among the most distinguished (and rhetorically sophisticated) was a series of reflective works on the sciences, from the chemist Humphry Davy’s visionary Consolations in Travel (1830) to Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-33). They were satirised to great effect in Thomas Carlyle’s bizarre scientific philosophy of clothes, Sartor Resartus (1833-34).

These works imagined new worlds of knowledge, helping readers to come to terms with unprecedented economic, social, and cultural change. They are anything but straightforward expositions or outdated ‘popularisations’, and deserve to be widely read in our own era of transformation. Like the best science books today, they are works in the literature of power.

James Secord is Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge, Director of the Darwin Correspondence Project, and a fellow of Christ’s College. His research and teaching is on the history of science from the late eighteenth century to the present. He is the author of the recently published Visions of Science: Books and Readers at the Dawn of the Victorian Age.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Charles Darwin. By J. Cameron. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post When science stopped being literature appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSherlock Holmes’ beginnings“A peaceful sun gilded her evening”Entitling early modern women writers

Related StoriesSherlock Holmes’ beginnings“A peaceful sun gilded her evening”Entitling early modern women writers

April 2, 2014

Etymology as a profession

Two or three times a year I receive questions about what the profession of an etymologist entails. I usually answer them briefly in my “gleanings,” and once I even devoted a post to this subject. Perhaps it won’t hurt if I return to the often-asked question again.

Etymology purports to explain why the words we use have the meanings familiar to us. Why is a tree called “tree,” why do we say man, winter, nine, and so forth? People have always been interested in the origin of things. Numerous myths explain how the world was created, how the first people came into being, why it rains, and why winds blow. There is no myth about the origin of the faculty of speech. We don’t know how human language originated. It is not even quite clear what we are looking for. How complicated should signals be to deserve the name of language? Are we looking for intelligible primordial cries or a well-formed vocabulary, or coherent syntax? The wide use of the term language (compare the language of art, of music, and the like) makes the search even more complicated. We constantly hear about some bright chimpanzees mastering language at the level of a two-year-old child, about the language of bees, dolphins, and others. This is all very interesting but not particularly helpful.

Numerous attempts have been made to obtain the answer about the origin of language from a study of the languages of “primitive peoples.” Alas, the level of material culture proves no clue to the level of the speakers’ language sophistication. The concept of primitive people has been compromised for all times, and, when it comes to the Indo-European languages, the more ancient a language is, the more complex its structure turns out to be. A language of primordial cries has not been found. The chasm between the first words of humanity and the words at the disposal of modern linguists is impossible to bridge. Our records span only a few millennia, and there is no certainty that any of the truly ancient words are still current today. The Semitic languages developed more slowly than the languages of the Indo-European family, but even with Aramaic and Hebrew we are incalculable centuries away from the beginning.

Consequently, we are better qualified to discover the origin of the words of Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, English, and other “extant” languages than the origin of the elusive first words. But even this task is often unattainable. Some words are among the oldest known, and we have no idea how long they had existed before they surfaced in written records. They are simply signs to us. One of such words is the numeral one. In all the Indo-European languages its cognates mean the same, and at some early time it probably sounded as oinoz. The form is unrevealing. Did it refer to the thumb or the little finger, or some single object? We feel more comfortable when it comes to derivatives. Thimble is related to thumb, and we only have to find out whether thimbles were ever worn on the thumb. We also notice that the German for thumb is Daumen and wonder why the English word has b at the end. Such questions can usually be answered quite well. It follows that an etymologist has to be informed about the properties of the things whose names are being discussed. Sometimes the answer is almost on the surface, but more often it is not. For example, German einladen means “to invite,” while laden means “to load.” What does loading have to do with invitation? This is a fairly complicated problem. The trouble with one is typical. Scholars collected all the forms related to it. The search presupposed the existence of certain nontrivial rules. They asked how people counted at the dawn of civilization and, to do this, traveled all over the world. The result is a mass of conflicting hypotheses, and a method is needed to decide which of them are especially promising. Hundreds of pages have been written about the origin of numerals.

The only junk worth admiring.

Other words are late. They too are the product of human creativity, but, even while dealing with recent coinages, we often fail to discover their sources. It may amuse non-specialists to see how many people have tried to find the origin of jazz and how uncertain even the best results are. Bigot (the subject of a recent post), like jazz, must also have arisen as a slang word. The circumstances in which a certain word comes into being may be so inconspicuous that we have little chance of discovering them. For a long time I have been planning to write a series of short essays on the words jink “to dodge a blow,” high jinks, I’ll be jiggered, and jingo, and their possible connections with jiggle (jink looks like a nasalized version of jiggle, and by jingo! is as emotional as high jinks). Unfortunately, too little is known about their history. Does junk belong with them? Is junk something that is avoided, “jinked”? Compare the vowel alternation in sink ~ sunk and drink ~ drunk. One should tread gingerly, that is, gently on this marshy ground. In a British journal for 1928, I read: “The taxi-drivers of London have announced that they are going to call the new two-seaters jixis, after the licencing House Secretary, Sir Williams Joynson-Hickes.” I am glad I know it. Otherwise, I may have proposed a profound theory of jixi being related to the jink words. In fact, it is a blend of Joynson and taxi (still not jaxi!).

So what are the qualifications of an etymologist? There is a thin layer of late words like jixi that requires no expertise in linguistics. Quite naturally, journalists prefer to write mainly about them, though the history of slang is often irritatingly opaque (capricious coinages, borrowings, and so forth). Work with the other words presupposes familiarity with historical phonetics, historical grammar, and historical semantics. If a language has a long written record, the specialist should be able to read old texts. Comparison is the backbone of linguistic reconstruction. Therefore, an etymologist is expected to have at least a passive knowledge of related and unrelated languages. Since words are the names of things, it is important to feel at home among both things and words. One may ask whether there are or have been people who met the requirements mentioned above. Yes, and rather many. Thanks to them we have an array of excellent etymological dictionaries. To the extent that a complicated etymology is a reward for weighing probabilities, it is seldom final and, by definition, can be superseded by a better one. But the assertion that nothing is final in this area of knowledge misses the mark. It is the end that tends to elude us, for a hunter cannot always be successful.

Occasionally I am asked whether there are job opportunities for etymologists. Paid jobs for experts in word history are few, though great dictionaries usually need editors who revise the etymological part of the entries. The OED has a group of professional etymologists, but this case is exceptional. Even university courses in etymology are rare, because historical linguistics has fallen into desuetude on our campuses. However, the public has a healthy interest in word origins, and books on etymology find a good market. Blogs dealing with etymology have a wide readership, and a stream of questions sent to bloggers never dries up. As long as people exist, they will want to know where words come from, and the world will need specialists who are able to satisfy their curiosity. However, a student aspiring to be an etymologist should remember that etymology is a respectable but not a lucrative occupation. Pre-etym is not quite the same thing as pre-med and pre-law.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A Chinese junk depicted in Travels in China. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology as a profession appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for March 2014Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 3

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for March 2014Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 3

Monuments Men and the Frick

At rare moments in time a library can have a singular impact on history. The recent release of George Clooney’s film Monuments Men (2014) has triggered an interest in the role that the Frick Art Reference Library played in the preparation of maps identifying works of art at risk in Nazi-occupied Europe. For the first time in history a belligerent was taking care of cultural treasures in a war zone.

![Bill Burke and Jane Mull, members of the Committee of the American Council of Learned Societies on the Protection of Cultural Treasures in War Areas, working with Gladys Hamlin, draftswoman, at the Frick Art Reference Library on a map of Paris. circa 1943-44. The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Photographs. [National Archives photograph]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1396549787i/9150446.jpg)

Bill Burke and Jane Mull, members of the Committee of the American Council of Learned Societies on the Protection of Cultural Treasures in War Areas, working with Gladys Hamlin, draftswoman, at the Frick Art Reference Library on a map of Paris. circa 1943-44. The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Photographs. (National Archives photograph)

Initially, the concern was that Allied bombing might damage or even destroy irreplaceable cultural treasures. This was articulated first by the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) who in June 1943 accepted Helen Clay Frick’s offer of the use of the Frick Art Reference Library, 10 East 71st Street, New York, which Helen had founded in 1920, in their endeavors. This was the only time in its history that the Library was closed to the public (15 July 1943- 4 January 1944).Under the auspices of William B. Dinsmoor (1886-1973), Chair of ACLS Committee on the Protection of Cultural Treasures in War Areas, which predated the Roberts Commission, lists of cultural treasures were drawn up at the Library using its guidebooks — Baedeker, Touring Club Italiano, Guide Bleu etc. — and other resources, supplemented by what could be seen as an early form of crowd-sourcing, i.e. questionnaires sent out to academics and others who had recently visited Europe. Lists of monuments and art objects were compiled and marked on maps of the relevant area — the maps supplied by the Library of Congress, the Army Map Service, or the American Geographical Society. Some of the monuments were rated higher in importance than others: it is interesting to speculate what the criteria might have been. The monuments were numbered and their locations marked on a gridded tracing paper overlay over the map. These were re-photographed by the Library photographers, Ira Martin and Thurman Rotan. The photographic studio where this was done is now the Library’s conservation facility.

Sample questionnaire from the ACLS Committee on the Protection of Cultural Treasures, c.1943. The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives.

Used by bomber pilots and navigators, then by soldiers on the ground directing artillery after the invasion of mainland Italy in September 1943 and France in June 1944, the maps were also incorporated into the Army’s Civil Affairs handbooks, which were issued to all officers on the ground. Later the lists and maps of treasures were used in the continuing struggle to return looted and confiscated portable treasures the rightful owners and their heirs. The Library’s resources including its Photoarchive are still used today for this very purpose.

Some 700 “Frick” or “Treasure” maps were made, and in a letter, dated 12 October 1943, to Dinsmoor, Monuments Man, Theodore Sizer praised their usefulness in the field and the work of “those magnificent women in the Frick”.

Dr. Stephen Bury is the Andrew W. Mellon Chief Librarian of the Frick Art Reference Library, New York, and is the Advisory Editor of the Benezit Dictionary of Artists.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Monuments Men and the Frick appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTreasures from Old Holland in New AmsterdamGeorges Pierre des Clozets: the 17th century conmanPolitics to reconnect communities

Related StoriesTreasures from Old Holland in New AmsterdamGeorges Pierre des Clozets: the 17th century conmanPolitics to reconnect communities

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers