Oxford University Press's Blog, page 830

March 28, 2014

Is our language too masculine?

As Women’s History month comes to a close, we wanted to share an important debate that Simon Blackburn, author of Ethics: A Very Short Introduction, participated in for IAITV. Joined by Scottish feminist linguist Deborah Cameron and feminist psychologist Carol Gilligan, they look at what we can do to build a more feminist language.

Is our language inherently male? Some believe that the way we think and the words we use to describe our thoughts are masculine. Looking at our language from multiple points of views – lexically, philosophically, and historically – the debate asks if it’s possible for us to create a gender neutral language. If speech is fundamentally gendered, is there something else we can do to combat the way it is used so that it is no longer – at times – sexist?

Watch more videos on iai.tv

What do you think can be done to build a more feminist language?

Simon Blackburn is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. Until recently he was Edna J. Doury Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at the University of North Carolina, and from 1969 to 1999 a Fellow and Tutor at Pembroke College, Oxford. He is the author of Ethics: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

>Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Is our language too masculine? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLaw and the quest for justiceIs love real?Ice time

Related StoriesLaw and the quest for justiceIs love real?Ice time

March 27, 2014

Unlearned lessons from the McMartin Preschool case

It was the longest criminal trial in American history and it ended without a single conviction. Five people were charged with child sexual abuse based on extremely flimsy evidence. Some parents came to believe outlandish stories about ritual abuse and tunnels underneath the preschool. It is no wonder that the McMartin Preschool case, once labeled the largest “mass molestation” case in history, has come to be called a witch-hunt. In a commentary to a Retro Report in the New York Times earlier this month, Clyde Haberman, former Times reporter, repeated the view that the McMartin case was a witch-hunt that spawned a wave of other cases of “dubious provenance.” But does that description do justice to the facts?

A careful examination of court records reveals that the witch-hunt narrative about the McMartin case is a powerful but not entirely accurate story. For starters, critics have obscured the facts surrounding the origins of the case. Richard Beck, quoted as an expert in the Retro Report story, recently asserted that the McMartin case began when Judy Johnson “went to the police” to allege that her child had been molested. Debbie Nathan, the other writer quoted by Retro Report, went even further, asserting that “everyone overlooked the fact that Judy Johnson was psychotic.”

Both of these claims are false.

Judy Johnson did not bring her suspicions to the police; she brought them to her family doctor who, after examining the boy, referred him to an Emergency Room. That doctor recommended that the boy be examined by a child-abuse specialist. The pediatric specialist is the one who reported to the Manhattan Beach Police Department that “the victim’s anus was forcibly entered several days ago.”

Although Judy Johnson died of alcohol poisoning in 1986, making her an easy target for those promoting the witch-hunt narrative, there is no evidence that she was “psychotic” three years earlier. A profile in the now-defunct Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, published after Johnson died, made it clear that she was “strong and healthy” in 1983 and that she “jogged constantly and ate health food.” The case did not begin with a mythical crazy woman.

Retro Report also disposed of the extensive medical evidence in the McMartin case with a single claim that there was no “definitive” evidence. But defense lawyer Danny Davis allowed that the genital injuries on one girl were “serious and convincing.” (His primary argument to the jury was that much of the time that this girl attended McMartin was outside the statute of limitations.) The vaginal injuries on another girl, one of the three involved in both McMartin trials, were described by a pediatrician as proving sexual abuse “to a medical certainty.” Were the reporter and fact-checkers for Retro Report aware of this evidence?

None of this is to defend the charges against five (possibly six) teachers in the case. Nor is it an endorsement of claims, made by some parents, that scores of children had been ritually abused. Rather, it is a plea to treat the case as something that unfolded over time and the children as individuals, not as an undifferentiated mass. As it turns out, there are credible reasons that jurors in both trials voted in favor of a guilty verdict on some counts. Those facts do not fit the witch-hunt narrative. Instead, they portray the reality of a complicated case.

When the story of prosecutorial excess overshadows all of the evidence in a child sexual abuse case, children are the ones sold short by the media. That is precisely what Retro Report did earlier this month. The injustices in the McMartin case were significant, most of them were to defendants, and the story has been told many times. But there was also an array of credible evidence of abuse that should not be ignored or written out of history just because it gets in the way of a good story.

The witch-hunt narrative has replaced any complicated truths about the McMartin case, and Retro Report, whose mission is to bust media myths, just came down solidly on the side of the myth. It wasn’t all a witch-hunt.

Ross E. Cheit is professor of political science and public policy at Brown University. He is an inactive member of the California bar and chair of the Rhode Island Ethics Commission. His forthcoming book, The Witch-Hunt Narrative: Politics, Psychology, and the Sexual Abuse of Children (OUP 2014), includes a 70-page chapter on the McMartin case.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: “Face In The Shadow” by George Hodan c/o PublicDomainPictures. Public domain via pixabay.

The post Unlearned lessons from the McMartin Preschool case appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play byExpressing ourselves about expressiveness in music‘You can’t wear that here’

Related StoriesThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play byExpressing ourselves about expressiveness in music‘You can’t wear that here’

Mark Vail remembers synth pioneer Bob Moog

While I wasn’t born early enough to know Antonio Stradivari, Henry E. Steinway, or Adolphe Sax personally, I did see 95-year-old Leon Theremin from afar at an outdoor Stanford University concert on 29 September 1991. Not many people have the opportunity to meet in person, or speak on the phone with, someone who designed and built a special musical instrument. I have been fortunate to have many such experiences with pioneers of my favorite instrument, the synthesizer, along with those who have invented other products used in the field of electronic music.

Synthesizers first stole my interest as a senior in high school when I read an article by Wendy Carlos in 1973’s The Last Whole Earth Catalog. In the making of Switched-On Bach and other early albums, Carlos used a Moog synthesizer, so naturally I wanted one too. In late 1976 I bought my first synthesizer, a Minimoog — America’s best-selling analog monophonic synthesizer of the 20th century.

In January 1988, in my first assignment as a member of Keyboard magazine’s editorial staff, I flew to Anaheim to attend my first Winter NAMM show, the biggest music convention in the Western hemisphere. Music merchants introduce their latest instruments, dealers and store owners comb the exhibition booths for items to sell, and other interested attendees play instruments, gather documentation, and greet old friends.

On the first day of the four-day event, my new boss — Editor-in-chief Dominic Milano — asked me if I wanted to meet synthesizer pioneer Bob Moog. Who wouldn’t? Just before the introduction, I switched the cassette recorder in my shirt pocket into record mode. I’ve since lost that tape, but thankfully before he passed at the young age of 71 in August of 2005, I became good friends with Bob.

Bob wrote for several Keyboard columns, including one called “Vintage Synths.” His first appeared in the September 1989 issue, and it was appropriately about the Minimoog. This and subsequent columns fueled a fire of interest in a technology that had been mostly abandoned through much of the decade: analog synthesis. Bob wrote three more vintage columns over the next five months then, following his January 1990 column on E-mu’s early lineup of modular synths, told Dominic that he preferred looking forward into the future instead of toward the past. Wonder of wonders, the “Vintage Synths” column fell right into my lap. I consider that one my luckiest days because it turns out that writing about old stuff – even if considered obsolete by some – never goes out of style.

Years later, in July 2004, I had the great fortune to visit and spend a few days with Bob in Asheville, North Carolina. During the tour through the Moog Music office, I spotted an odd device with knobs and jacks sitting on a shelf and asked Bob what it was. He said he didn’t know, but grabbed and posed with it.

Synthesizer pioneer Bob Moog poses with an unknown device in the Moog Music office in July 2004. Photo courtesy of Mark Vail.

Many NAMM attendees yearned to meet Bob Moog, especially after he had legally recovered the right to use his own name on musical instruments again in 2002 and developed a Minimoog for the 21st century, the Voyager. During the January 2005 convention, two friends and I were determined to have dinner with Bob, but we more or less had to kidnap him from the Moog Music booth where dozens were waiting for his autograph. We had to convince several of the autograph seekers to return on Sunday to meet Bob, and quickly whisked him away from the scene.

The four of us—synthesists Amin Bhatia and Dave Gross, plus Bob and I—got into my car with no idea where we were going to eat. Our clueless excursion through Anaheim first took us past a flashy bordello, which Bob kiddingly said might be fun, before finding a quiet but festively painted Vietnamese restaurant where we enjoyed a wonderful dinner.

From left to right, author Mark Vail, synth pioneer Bob Moog, Seattle synthesist Dave Gross, and synthesist/composer Amin Bhatia. Photo courtesy of Mark Vail.

At the time, Amin Bhatia was working on an all-electronic version of Ravel’s “Bolero,” using a series of renowned vintage synthesizers and drum machines that he wanted Bob to introduce in a voiceover for the music. Bob loved the early snippets of Amin’s music and was thrilled by the idea, but within a few months the news came that Bob was battling brain cancer, which eventually took his life on 21 August 2005. I dearly miss my brilliant and jovial friend Bob Moog, whose business card listed him as the Grand Poobah.

Building on his life-long interest in music, Mark Vail discovered synthesizers in 1973 and bought his first in 1976. After earning an MFA in electronic music in 1983, he served on the editorial staff at Keyboard magazine from 1988 to 2001. The author of Vintage Synthesizers, The Hammond Organ: Beauty in the B, and The Synthesizer, Mark is internationally acknowledged as a foremost authority on synthesizers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mark Vail remembers synth pioneer Bob Moog appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGrand Piano: the key to virtuosityExpressing ourselves about expressiveness in musicMonthly etymology gleanings for March 2014

Related StoriesGrand Piano: the key to virtuosityExpressing ourselves about expressiveness in musicMonthly etymology gleanings for March 2014

Expressing ourselves about expressiveness in music

Picture the scene. You’re sitting in a box at the Royal Albert Hall, or the Vienna Musikverein. You have purchased tickets to hear Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony performed by an internationally-renowned orchestra, and they are playing it in a way that sounds wonderful. But what makes this such a powerful performance?

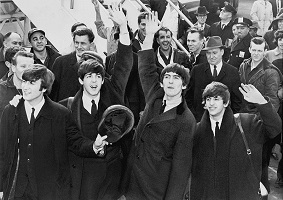

What is expressiveness? Let’s start by looking at these images …

Do you notice what they all have in common? They are all displaying different kinds of expression. Just as facial expressions communicate different information to us, musicians playing the same piece will still produce slight differences. You can’t hear the musicians in these pictures, but they may both be playing the same piece in a way that is not exactly the same as the other group of musicians.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Click here to view the embedded video.

People say music is expressive. They usually say it is expressive of emotions and therein lays its power. But is this true of all music in all cultures and historical periods? Does it matter how it’s performed and how it’s experienced?

Philosophers, psychologists, and musicians have been pondering these questions for centuries. Over the last hundred years psychologists have contributed much to developing an empirically-based understanding of the mechanisms at play. The distinction between what may be “in the music” and what the performer “adds” became a fundamental assumption leading to various theories and definitions of “expressiveness in music performance.”

Ever since the pioneering work of Carl Seashore in the 1930s psychologists have been studying individual performers to find out “what it is that a performer brings to a piece of music.” So what is it that One Direction does when covering “All You Need Is Love” that makes their performance expressive? Are they more expressive than the Beatles are in this clip? Is it the song that is expressive or does it matter how it is performed?

For those educated in western classical music, Seashore’s working definition of what is expressiveness seems reasonable: You are listening to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and different orchestras and conductors make it sound more or less dramatic, uplifting, emotional, riveting. But if we pause for a moment and think of all those ever listening to this great icon of western musical culture, is it reasonable to believe that they know what is “the music”, i.e. Beethoven’s composition, and what the performers “bring to it”? What about an audience who have never experienced the piece before? How do they know what is “the music” and what is the contribution of the musician? This dilemma is even more obvious in other styles, like jazz, traditional, popular, or world music.

One, wordier definition of expressiveness in music performance is “the micro-deviations from the notated dictates of the score a performer executes while playing.” So, if the notes of a score are played literally, the piece will sound dull and inexpressive — like an old MIDI notation player, or a student playing precisely in time with a metronome. The result is a “neutral” performance, like the computer image of the face above. But is this an acceptable definition? What about musicians who do not use a music score – improvisers, people who play music by ear?

Recent empirical work has shown that listeners tend to be unable to say if the expressiveness they are hearing originates from the composition or the performance. Studying the experience of professional musicians highlights how differently they approach their performance. For them the score is never just notes on paper but already music imagined as sound. This imagination depends on their socio-cultural, historical position, personality, and education. They use metaphors and heuristics, short-cuts that package up accumulated knowledge and speeds up problem solving in preparation for and during performance. They rarely speak of specific emotions to be conveyed but conceive of music as “emotional,” “dramatic,” “uplifting,” or “turbulent,” for instance.

This is true of music and musicians of other artistic traditions, like classical Hindustani music. According to the dhrupad singer Uday Bhawalkar, “Music without emotion is not music at all, but we cannot name this emotion, these emotions, we cannot specify them.” The sentiments or emotions that we encounter in daily life become transformed into aesthetic experiences in theatre.

Empirical work in the area of jazz and popular music shows the importance of rhythm, vocal gestures, persona, and the role of technology to create meaning through sound effects. One fascinating finding regarding the culturally construed nature of what is “expressiveness in music performance” comes from a study of the Bedzan Pygmies. They live in very small communities with 40-60 kilometres distance between them and come together only for large festivities like weddings and funerals. When singing together in intricate polyphony, each singer varies his or her line at will while maintaining the overall identity of the song. For them “expressiveness” increased when they could detect more voices in the ensemble.

Expressiveness is an important part of music performance and perception, and although we have an intuitive understanding of what expressiveness in music means, as it turns out expressiveness in music performance seems too malleable and slippery to be defined in a singular way. So what is more important is to formulate the perspective of future research and discussion, to reorient our approach and reconstruct the object of investigation.

Dorottya Fabian, Renee Timmers, and Emery Schubert, are all researchers and lecturers in music psychology. Their book Expressiveness in Music Performance offers a variety of approaches to talk meaningfully about expressiveness and music within a cross-cultural context, providing disciplinary overviews, discussion papers and case studies to show that debates of importance across the humanities and social sciences can be conducted in a richly evidence-based manner.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Guilty Face, by Barry Langdon-Lassagne, CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Your Smiling Face, by Sibelle77, CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Изображение-Портреты-Михайлова Елена Владимировна, by участница Udacha, CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (4) Addys Mercedes Kult 02, by Schorle, CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (5) Adam Romański 1, by Konrad Wawrzkiewicz (Shannon5), CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons. (6) One Direction Glasgow, by Fiona McKinlay, CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (7) The Beatles in America, by United Press International, photographer unknown, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Expressing ourselves about expressiveness in music appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDiscussing Josephine Baker with Anne ChengFrom art to autism: a Q&A with Uta FrithBritain, France, and their roads from empire

Related StoriesDiscussing Josephine Baker with Anne ChengFrom art to autism: a Q&A with Uta FrithBritain, France, and their roads from empire

Global Opioid Access: WHO accelerates the pace, but we still need to do more

With the WHO Executive Board recently adopting the resolution ‘Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment within the continuum of care’, which is to be referred to the World Health Assembly for ratification in May, Nathan Cherny puts the current global situation in perspective and lays out the next steps needed in this crucial campaign to end suffering to millions.

By Nathan Cherny

In the curious trail that has been my life thus far, some would say that there was a certain inevitability that I would end up working for cancer patients’ right to access medication for adequate relief of their suffering. As a medical student I suffered terrible cancer-related pain from a thoracotomy to remove lung metastases for testicular cancer. As an oncologist and palliative care physician in the Middle East, my current work allows me to look after both Israeli and Palestinian patients. My profession has also taken me to caring for many “medical tourists” from Eastern Europe as well as foreign workers from Thailand, India, Nepal, and the Philippines. Oh, and I was born on Human Rights Day, 10 December 1958!

I hate pain. I am appalled by the global scope of untreated and unrelieved cancer pain. At the initiative of its Palliative Care Working Group, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has taken this on board as a global priority issue. ESMO facilitated the first comprehensive study to evaluate the barriers to pain relief in Europe, which highlighted the distressing situation in many Eastern European counties.

Nathan Cherny

In follow-up, a large collaborative group was formed for an even more ambitious study. The Global Opioid Policy Initiative (GOPI) combined the work and talents of ESMO, the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), the Pain and Policies Study Group (PPSG) of the University of Wisconsin, and the World Health Organization (WHO), and 17 other leading oncology and palliative care societies worldwide.

The GOPI studied opioid availability and accessibility for cancer patients in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean. The results were published in a special supplement of the Annals of Oncology in December 2013. The seven manuscripts in the special issue highlighted the global problem of excessively restrictive regulations regarding the prescribing and dispensing of opioids — ‘catastrophe born out of good intentions’.

In order to prevent abuse and diversion, most patients with genuine need to relieve severe cancer pain cannot access the appropriate medication. Millions of people around the world end their lives racked in pain, harming not only the patients but also their families who bear witness to this torturous tragedy.

On 23 January 2014, the WHO Executive Board adopted a stand-alone resolution on palliative care which will be referred to the World Health Assembly for ratification in May 2014. This is great news for all those campaigning to improve access to medication to end suffering to millions. There is still much to be done on this long, winding road, yet we can still be proud. Thanks to our united efforts and the evidence provided by the GOPI data, our voices are being heard.

Overregulation of opioids is not the only problem impeding global relief of cancer pain. In many places around the world there is major need to: educate clinicians in the assessment and management of pain; educate the public regarding the effectiveness and safety of opioid analgesia in the management of cancer pain; and secure supplies of affordable medications.

The next steps: The GOPI Collaborative Group is now writing to Ministers of Health in the many countries where we have identified major over-regulation with a 10 point plan to help redress the problem, covering education, restrictions, limits, professional standards, monitoring, and prescription.

Tell us what actions you can take to incorporate these next steps in your country. Can you contact your Ministry of Health? What could be inspirational for others to know? We make more noise if we all shout together.

Nathan Cherny was the Chair of the ESMO Palliative Care Working Group since 2008 and has been a member of the working group since its inception in 1999. He was the main driving force in the creation of the ESMO Designated Centre of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care Programme which was launched in 2003 and last year had its 10th Anniversary. Nathan also wrote the ESMO 2003 Position Paper: ESMO Policy on Supportive and Palliative Care. Watch the Advocacy in Action 2013 video on: Palliative Care & Quality Of Life Care: Redefining Palliative Care.

Opioid availability and accessibility for the relief of cancer pain in Africa, Asia, India, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean: Final Report of the International Collaborative Project was published as an Annals of Oncology supplement in December 2013.

Annals of Oncology is a multidisciplinary journal that publishes articles addressing medical oncology, surgery, radiotherapy, paediatric oncology, basic research and the comprehensive management of patients with malignant diseases. Follow them on Twitter at @Annals_Oncology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Photo of Nathan Cherny, via ESMO; (2) GOPI banner, via Global Opioid Policy Initiative/ESMO

The post Global Opioid Access: WHO accelerates the pace, but we still need to do more appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWorld TB Day 2014: Reach the three millionCancer therapy: now it’s getting personalThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wettemann Jr. - Enclosure

Related StoriesWorld TB Day 2014: Reach the three millionCancer therapy: now it’s getting personalThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wettemann Jr. - Enclosure

March 26, 2014

Monthly etymology gleanings for March 2014

Beguines.

The origin of Beguine is bound to remain unknown, if “unknown” means that no answer exists that makes further discussion useless. No doubt, the color gray could give rise to the name. If it were not so, this etymology would not have been offered and defended by many scholars. But, as a rule, such names develop from terms of abuse (see also Stephen Goranson’ comment). I would also like to refer to pattern congruity, though in etymology it is a dangerous tool. The three words—beggar, bugger, and bigot, as well as bicker—sound alike and refer (at least the nouns do) to the same semantic sphere. To be sure, one can string together deceptively similar words that do not belong together and get wrong results. For example, the name of the protagonist in one of the most famous Icelandic sagas is Grettir. Several episodes in the saga (and even the wording) have unmistakable analogs in the Old English poem Beowulf. For this reason, Grettir and Grendel have sometimes been compared. Yet the comparison is not feasible. So to repeat, the question remains open; as usual, we are dealing with probabilities. I only hope that the picture I have drawn is not fanciful. As for the medieval Bulgarians, I think they are called Orthodox in the loosest sense of the word, that is, “not belonging to the Roman Church.” The word Beguine is Old French, and the chance of a German feminine suffix having been appended to it is vanishingly low.

Our cliché-ridden English.

Last month I touched on the buzzwords many people detest. Here (and in the next paragraph) are some more responses that I received and examples I found myself. For the reason unknown to me, I was invited to attend a demonstration of cutting edge hearing instruments. Do I need such devices in any part of my body? But unless you are, like, cutting-edge, innovative, competitive, interdisciplinary, and diverse, how can you assume the position of leadership in your branch and who will need you, you know? I have no idea, but, to quote an unrelated letter to the editor, “let’s you and I frame the discussion.”

Tongue-tied eloquence.

Nature, they say, does not tolerate void. The language of the young is full of empty holes, and it is amazing or, conversely, depressing or pathetic (chose your favorite buzzword) to observe how desperately kids try to fill them. In the capacity as a committee member I have recently looked through several hundred evaluations students at my university, from freshmen to seniors, write at the end of the courses they take (different departments, various majors, most diverse subjects). My colleagues have been praised in many ways, and it is the subtle (another buzzword) choice of epithets that impressed me most. Everybody around turned out to be awesome, just awesome. Those students who were truly overwhelmed and whose vocabulary was more nuanced wrote awesome! and awesome!! Even awesome!!! turned up once. A single fly in this awe-inspiring ointment was the writers’ predilection for calling their instructors “proffesors,” though perhaps, when one is in love, the overall number of letters in a word matters more than their distribution. The next most frequent words in the evaluations were passionate and fun. Students really enjoyed the passion for the subjects we profess and really found some of us to be helpful, especially those who are fun professors ~ proffesors, that is, the numerous “fabulous” teachers “who made it fun” or “super fun,” for, if you provide fun throughout the semester, along with occasional food and constant feedback, the students will really and “definately” miss your course “alot.” Not to be forgotten: If the assignments are clearly “layed out,” you may be called a fantastic dude or the coolest guy ever.

Foreigners complain that the vocabulary of English is almost impossible to master. They don’t realize how much can be said with very few words and that young native speakers of English find the best literature in their language so hard that they can no longer read it. Publishers cater to them and bring out books containing only the vocabulary they are able to understand, so that, to quote a perennial classic, there begins a regular competition for stupidity, with everyone trying to look even more stupid than they really are.

Gleanings in winter

Are toys “us” or “them”?

This question occurred to me when I read the following ad sent by Walter Turner:

“Another very good deed done by *** Service [no comma] which confirms their commitment to help all of us to do their family’s histories and honor them for their rich contributions to our lives.”

Of course we should do all we can to make their (= our) lives meaningful! When in trouble, always say they and their. The following excerpt will confirm the validity of this safety rule (from the Associated Press):

“Some [students] said the police response was excessive, one person said their nose was broken by a beer bottle that someone threw and another said they were ‘teargassed’.”

A good title for a thriller in the spirit of Gogol: A Person and Their Nose. Their (the person’s, the Nose’s, and collectively) problems are many.

The mood of the stories are gloomy.

Under this title, borrowed from a student paper, I occasionally quote examples of the ineradicable rule of American English that says: “Make the verb agree with the noun next to it.” In a story of the missing plane, the Associated Press informs its readers that “[a] string of previous clues have led nowhere.” Let no one tell me that string is a collective noun. Not in this case!

Language change.

I have noted in the past that the use of the agreement as in the mood of the stories are gloomy is so pervasive that one may state the rise of a new norm in American English (I don’t know how “new” it is). This is the way of language change. For example, at a certain moment, the people who have no trouble distinguishing between he and him feel at a loss when it comes to who and whom and begin to say the doctor whom we believe saved the patient. Editors and teachers fight the trend but soon they too forget what is right and what is wrong, and the more advanced (“popular”) usage takes over.

Here is an example of illogical syntax, which, if I am not mistaken, has won the day. “As a pediatrician, your editorial resonated with me,” “As an undergraduate, Prof. X showed me her handout,” and “As a valued ***customer, we have important news for you about….” I can stomach the first sentence (“I am a pediatrician, and the article has resonated with me”), but Nos. 2 and 3 strike me as nonsense: Professor X did not show the writer her handout when she, the professor, was an undergraduate. Nor is the company a valued customer. But as, among other things, means “when,” so that instead of saying “When I was an undergraduate, Professor X… showed me…,” people cut corners and say “As an undergraduate, Processor X….” Fortunately or unfortunately, the world goes its way without caring about teachers’ opinions. Change is natural (otherwise we would still be speaking Proto-Indo-European, which would be a catastrophe for historical linguists), but some sentences are so awkward that hardly anyone will like them: “I am an unwavering advocate of greater student participation in and control of student fees….” Well-meant but ugly.

My winter gleanings are over. I congratulate our readers on the coming of spring. Please send more questions and comments. In spring everybody and everything wakes up.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Wolf and the Shepherds by Valentin Serov, 1898. Public domain via Wikipaintings.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for March 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 2Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 3

Related StoriesBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 2Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 3

‘You can’t wear that here’

When a religious believer wears a religious symbol to work can their employer object? The question brings corporate dress codes and expressions of religious belief into sharp conflict. The employee can marshal discrimination and human rights law on the one side, whereas the employer may argue that conspicuous religion makes for bad business.

The issue reached the European Court of Human Rights in 2013 in a group of cases (Eweida and Others v. United Kingdom), following a lengthy and unsuccessful domestic legal campaign, brought by a group of employees who argued their right of freedom of religion and belief (under Article 9 of the Convention) had not been protected when the UK courts favoured their employers’ interests.

Nadia Eweida, an airline check-in clerk, and Shirley Chaplin, a nurse, had been refused permission by their respective employers, British Airways and an NHS trust, to wear a small cross on a necklace so that it was visible to other people. The employer’s rationale in each case was rather different. British Airways wanted to maintain a consistent corporate image so that no ‘customer-facing staff’ should be permitted to wear jewellery for any reason. The NHS trust argued that there was a potential health and safety risk if jewellery were worn by nursing staff – in Ms Chaplin’s case a disturbed patient might ‘seize the cross’ and harm either themselves or indeed Ms Chaplin.

Nadia Eweida, an airline check-in clerk, and Shirley Chaplin, a nurse, had been refused permission by their respective employers, British Airways and an NHS trust, to wear a small cross on a necklace so that it was visible to other people. The employer’s rationale in each case was rather different. British Airways wanted to maintain a consistent corporate image so that no ‘customer-facing staff’ should be permitted to wear jewellery for any reason. The NHS trust argued that there was a potential health and safety risk if jewellery were worn by nursing staff – in Ms Chaplin’s case a disturbed patient might ‘seize the cross’ and harm either themselves or indeed Ms Chaplin.

Both applicants argued that their sense of religious obligation to wear a cross outweighed the employer’s normal discretion in setting a uniform policy. They also argued that their respective employers had also been inconsistent because their uniform policies made a number of specific accommodations for members of minority faiths, such as Muslims and Sikhs.

A major difficulty for both Eweida and Chaplin was the risk that their cross-wearing could be dismissed as a personal preference rather than a protected manifestation of their beliefs. After all many – probably most – Christians do not choose to wear the cross. The UK domestic courts found that the practice was not regarded as a mandatory religious practice (applying a so-called ‘necessity’ test) but rather one merely ‘motivated’ by religion and not therefore eligible for protection. This did not help either Eweida or Chaplin as both believed passionately that they had an obligation to wear the cross to attest to their faith (in Chaplin’s case this was in response to a personal vow to God). The other major difficulty for both applicants was that the Court had also historically accepted a rather strange argument that people voluntarily surrender their right to freedom of religion and belief in the workplace when they enter into an employment contract, and so the employer has discretion to set its policies without regard to interfering with its employees religious practices. If an employee found this too burdensome, then he or she could protect their rights by resigning and finding another job. This argument, ignoring the realities of the labour market and imposing a very heavy burden on religious employees, has been a key reason why so few ‘workplace’ claims have been successful before the European Court.

Arguably the most significant aspect of the judgment was that the religious liberty questions were in fact considered by the Court rather than being dismissed as being inapplicable in the workplace (as the government and the National Secular Society had both argued). The Court specifically repudiated both the necessity test and the doctrine of ‘voluntary surrender’ of Article 9 rights at work. As a result, it has opened the door both to applications for protection for a much wider group of religious practices in the future and for claims relating to employment. From a religious liberty perspective this is surely something to welcome.

Nadia Eweida’s application was successful on its merits. It is now clear therefore that an employer cannot over-ride the religious conscience of its staff due to the mere desire for uniformity. However, Chaplin was unsuccessful, the Court essentially finding that ‘health and safety’ concerns provided a legitimate interest allowing the employer to over-ride religious manifestation. This is disappointing, particularly since evidence was presented that the health and safety risks of a nurse wearing a cross were minimal and that, in this case, Chaplin was prepared to compromise to reduce them still further. Hopefully this aspect of the judgment (unnecessary deference to national authorities in the realm of health and safety) will be revisited in future.

Whether that happens or not it is clear that religious expressions in the workplace now need to be approached differently after the European Court’s ruling. The idea that employees must leave their religion at the door has been dealt a decisive blow From now on, if corporate policy over-rides employees’ religious beliefs, then employers will be under a much greater obligation to demonstrate why, if at all, this is necessary.

Andrew Hambler and Ian Leigh are the authors of “Religious Symbols, Conscience, and the Rights of Others” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the Oxford Journal of Law and Religion. Dr Andrew Hambler is senior lecturer in human resources and employment law at the University of Wolverhampton. His research focusses on how the manifestation of religion in the workplace is regulated both at an organisational and at a legal level. Andrew is the author of Religious Expression in the Workplace and the Contested Role of Law, a monograph due for publication in November 2014. Ian Leigh is a Professor of Law at Durham University. He has written extensively on legal and human rights questions concerning religious liberty. He is co-author of Rex Ahdar and Ian Leigh, Religious Freedom in the Liberal State (2nd edition, OUP, 2013).

The Oxford Journal of Law and Religion is hosting its second annual Summer Academy in Law and Religion this coming June. The title of this year’s academy is “Versions of Secularism – Comparative and International Legal and Foreign Policy Perspectives on International Religious Freedom.” The meeting will take place June 23 – 27 at St. Hugh’s College, Oxford. Click for more details about the conference, confirmed speakers, and registration.

The Oxford Journal of Law and Religion publishes a range of articles drawn from various sectors of the law and religion field, including: social, legal and political issues involving the relationship between law and religion in society; comparative law perspectives on the relationship between religion and state institutions; developments regarding human and constitutional rights to freedom of religion or belief; considerations of the relationship between religious and secular legal systems; empirical work on the place of religion in society; and other salient areas where law and religion interact (e.g., theology, legal and political theory, legal history, philosophy, etc.).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Fresh photo of girl’s neck with cross necklace. © tomasmikulas via iStockphoto.

The post ‘You can’t wear that here’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesVictims of slavery, past and presentCSI: Oral History - EnclosureThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wettemann Jr. - Enclosure

Related StoriesVictims of slavery, past and presentCSI: Oral History - EnclosureThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wettemann Jr. - Enclosure

Who signed the death warrant for the British Empire?

The rapid dissolution of the European colonial empires in the middle decades of the 20th century were key formative events in the background to the contemporary global scene. As the British Empire was the greatest of the imperial structures to go, it is worth considering who signed the death warrant. I suggest there are five candidates.

The first is the Earl of Balfour, Prime Minister 1902-1905, who later penned the exquisite ‘status formula’ of 1926 to describe the relations of Britain and its self-governing white settler colonies, then known as Dominions. They were ‘equal in status’ though ‘freely co-operating’ under a single Crown. The implications were that they were as independent as they wanted to be and this was marked in the preamble to the Statute of Westminster five years later. Some visionaries at this time suggested that places like India or Nigeria might be Dominions, too, suggesting that here was an agreed exist route from empire.

India, indeed, took the route in 1947 when Clement Attlee, the second candidate, announced that the Raj would end. The jewel in the imperial crown was removed when the Raj was partitioned into the Dominions of India and Pakistan. They were followed into independence a year later by Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Burma (Myanmar). With the ending of the Raj it was evident that empire’s days were numbered.

Harold Macmillan

Harold Macmillan, our third candidate, extended independence more widely to Africa. His celebrated ‘Wind of Change’ speech to the South African Parliament in 1960 marked a firm foot on the decolonization accelerator pedal. Macmillan’s conservative governments, 1957-1963, granted independence to fourteen colonies (eleven in Africa).It looked as if the process would be completed by the fourth candidate, Harold Wilson, whose ‘Withdrawal from East of Suez’ and abolition of the Colonial Office ran in parallel to Britain’s preparations to enter the European Communities. Although the conservative government of Edward Heath, 1970-1974, delayed the withdrawal for a few years, Heath announced to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Singapore in 1971 that the empire was ‘past history’. And, as part of his application of the baleful disciplines of business management to government, he ordered a ‘Programme Analysis and Review’ of all the remaining dependent territories. This process, conducted over 1973-74, concluded that the dependencies were liabilities rather than assets and that a policy of ‘accelerated decolonization; should be adopted in many small island countries in the Pacific, Indian Ocean, and Caribbean previously deemed too small and incapable of being sovereign states.

Although the Heath government never managed to approve this policy before it was ejected from office after the miner’s strike in 1974, the second Wilson government went ahead. It was Jim Callaghan, as Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs who signed the death warrant on 13 June 1975 in the form of a despatch to administrators suggesting that the dependencies had been ‘acquired for historical reasons that were no longer valid’. To avoid the charge of colonialism being made by the anti-imperialist majority in the United Nations, Britain adopted ‘accelerated decolonization’ in the Pacific Islands. During the late 1970s and the 1980s most of the remaining dependent territories moved rapidly to independence. An empire acquired over half-a-millennium was dissolved in less than half-a-century.

W. David McIntyre was educated at Peterhouse, Cambridge, the University of Washington, Seattle, and the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. After teaching for the Universities of Maryland, British Columbia, and Nottingham, he became Professor of History at the University of Canterbury New Zealand between 1966 and 1997. As Honorary Special Correspondent of The New Zealand International Review he reported on Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings from 1987 to 2011. His latest book is Winding up the British Empire in the Pacific Islands.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Harold Macmillan. By Vivienne (Florence Mellish Entwistle) [Open Government Licence], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Who signed the death warrant for the British Empire? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGloomy terrors or the most intense pleasure?Britain, France, and their roads from empireCelebrating Women’s History Month

Related StoriesGloomy terrors or the most intense pleasure?Britain, France, and their roads from empireCelebrating Women’s History Month

March 25, 2014

Victims of slavery, past and present

Today, 25 March, is International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. But unfortunately, the victims of slavery were not all in the distant past. Contemporary forms of slavery and forced labor remain serious problems and some reputable human rights organizations estimate that there are some 21-30 million people living in slavery today. The issue is not limited to just a few countries, but involves complex transnational networks that facilitate human trafficking. Just as in the past, international cooperation is necessary to end this international problem.

International law played a key role in ending the transatlantic slave trade in the 19th century. In the year 1800, slavery and the slave trade were cornerstones of the Atlantic world and had been for centuries. Tens of thousands of people from Africa were carried across the Atlantic each year, and millions lived in slavery in the new world. In 1807, legislatures in both the United States and Britain — two countries whose ships had been key participants in the trade — banned slave trading by their citizens. But two countries alone could not stop what was a truly international traffic, which quickly shifted to the ships of other nations. International cooperation was required.

Beginning in 1817, Britain negotiated a series of bilateral treaties banning the slave trade and creating international courts to enforce that ban. These were, I suggest, the first permanent international courts and the first international courts created with the aim of enforcing a legal rule designed to protect individual human rights. The courts had jurisdiction to condemn and auction off ships involved in the slave trade, while freeing their passengers. The crews of navy ships that captured the illegal slave vessels were entitled to a share of the proceeds of the sale of the vessels, creating an incentive for vigorous policing. By 1840, more than twenty nations — including all the major maritime powers involved in the transatlantic trade — had signed treaties of various sorts (not all involving the international courts) committing to the abolition of slave trading. By the mid-1860s, the slave trade from Africa to the Americas had basically ceased, and by 1900, slavery itself had been outlawed in every country in the Western Hemisphere.

“East African enslaved people rescued by the British naval ship, HMS Daphne (1869)” via The National Archives UK on Flickr.

While treaties today prohibit slavery and the slave trade, international efforts at eradicating modern forms of slavery and forced labor trafficking are inadequate. Looking to the lessons of the past, international policy makers should consider implementing a more robust system for dismantling modern day slavery. A system of property condemnation with economic incentives for whistleblowers could again be used to leverage enforcement power; someone who turns in a human trafficker could be entitled to a share of the proceeds of a sale of the trafficker’s assets. Similarly, international courts could be used in especially severe cases. Enslavement is a crime against humanity under the statute of International Criminal Court, and severe cases involving transnational trafficking networks with large numbers of victims might meet the criteria for ICC jurisdiction. Violent acts in wartime are more visible international crimes, but the human impact of enslavement is no less severe or deserving of international justice.

It is not enough to remember past victims of enslavement; to truly honor their memory, we must do something to help those who are enslaved today.

Jenny S. Martinez is Professor of Law and Justin M. Roach, Jr., Faculty Scholar at Stanford Law School. A leading expert on international courts and tribunals, international human rights, and the laws of war, she is also an experienced litigator who argued the 2004 case Rumsfeld v. Padilla before the U.S. Supreme Court. Martinez was named to the National Law Journal’s list of “Top 40 Lawyers Under 40.” She is the author of The Slave Trade and The Origins of International Human Rights Law (OUP 2012), now available in paperback.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Victims of slavery, past and present appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn international law reading list for the situation in CrimeaThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play byWhat does the economic future hold for Spain?

Related StoriesAn international law reading list for the situation in CrimeaThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play byWhat does the economic future hold for Spain?

What does the economic future hold for Spain?

The good news is that Spain has finally come out of a five-year recession that was triggered by the bursting of its property bubble. The bad news is that the unemployment rate remains stubbornly high at a whopping 26%, double the European Union average.

The scale of the property madness was such that in 2006 the number of housing starts (762,214) was more than that of Germany, France, and Italy combined. This sector, to borrow the title of a novel by Gabriel García Márquez, was a Chronicle of a Death Foretold. There are still an estimated more than one million new and second hand unsold homes.

The excessive concentration on the property sector, as the motor of an economy that boomed for a decade, created a lopsided economic model and fertile ground for corruption. When the sector crashed as of 2008 and house prices plummeted, 1.7 million people lost their jobs in construction out of a total of 3.7 million job losses in the last six years, households were left with mortgages they could not pay and property development companies unable to service their bank loans. This, in turn, severely weakened parts of the banking system which had to be rescued by the European Stability Mechanism with a €42 billion bailout programme. Spain exited the bail-out in January, but bad loans still account for more than 13% of total credit, up from a mere 0.7% in 2006.

Spain has emerged from recession thanks largely to an impressive export performance, achieved through an “internal devaluation” (lower unit labour costs stemming from wage cuts or a wage freeze and higher productivity). As a euro country, Spain cannot devalue. Merchandise exports rose from €160 billion in 2009 to €234 billion in 2013, an increase equivalent to more than 7% of GDP. This growth has been faster than the pace of powerhouse Germany, albeit from a smaller base. Exports of goods and services rose from 27% of GDP in 2007 to around 35% last year. The surge in exports combined with the drop in imports and a record year for tourism, with 60 million visitors, turned around the current account, which was in surplus for the first time in 27 years. In 2007, the current account recorded a deficit of 10%, the highest in relative terms among developed countries.

Unemployment is the most pressing problem. The depth of the jobs’ crisis is such that Spain, which represents 11% of the euro zone’s economy and has a population of 47 million, has almost 6 million unemployed (around one-third of the zone’s total jobless), whereas Germany (population 82 million and 30% of the GDP) has only 2.8 million jobless (15% of the zone’s total). Germany’s jobless rate is at its lowest since the country’s reunification, while Spain’s is at its highest level ever.

Mariano Rajoy

Young Spanish adults, particularly the better qualified, are increasingly moving abroad in search of a job, though not in the scale suggested by the Spanish media which gives the impression there is a massive exodus and brain drain. One thing is the large flow of those who go abroad, especially to Germany, and return after a couple of months; another the permanent stock of Spaniards abroad (those who stay beyond a certain amount of time), which is surprisingly small. According to research conducted by the Elcano Royal Institute, Spain’s main think tank, between January 2009 and January 2013, the worst years of Spain’s recession, the stock of Spaniards who resided abroad increased in net terms by a mere 40,000, which is less than 0.1% of Spain’s population, to 1.9 million. These figures are based on official Spanish statistics cross-checked with data in the countries where Spaniards reside. The number of Spaniards living abroad is less than one-third the size of Spain’s foreign-born population of 6.4 million (13.2% of the total population). Immigrants in Spain are returning to their country of origin, particularly Latin Americans.

Spain’s crisis has also resulted in a long overdue crackdown on corruption. There are around 800 cases under investigation, most of them involving politicians and their business associates. Spain was ranked 40th out of 177 countries in the 2013 corruption perceptions ranking by the Berlin-based Transparency International, down from 30th place in 2012. Its score of 59 was six points lower. The nearer to 100, the cleaner the country. Spain was the second-biggest loser of points, and only topped by war-torn Syria. The country is in for a long haul.

William Chislett, the author of Spain: What Everyone Needs to Know, is a journalist who has lived in Madrid since 1986. He will be talking on his book at the Oxford Literary Festival on 29 March. He covered Spain’s transition to democracy (1975-78) for The Times of London and was later the Mexico correspondent for the Financial Times (1978-84). He writes about Spain for the Elcano Royal Institute, which has published three books of his on the country, and he has a weekly column in the online newspaper El Imparcial. He has previously written on Spanish unemployment and Gibraltar for the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Spanish Falg By Iker Parriza. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons (2) Mariano Rajoy By Gilad Rom. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post What does the economic future hold for Spain? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play byMonetary policy, asset prices, and inflation targetingA hidden pillar of the modern world economy

Related StoriesThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play byMonetary policy, asset prices, and inflation targetingA hidden pillar of the modern world economy

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers