Oxford University Press's Blog, page 832

March 21, 2014

What Coke’s cocaine problem can tell us about Coca-Cola Capitalism

In the 1960s, Coca-Cola had a cocaine problem. This might seem odd, since the company removed cocaine from its formula around 1903, bowing to Jim Crow fears that the drug was contributing to black crime in the South. But even though Coke went cocaine-free in the Progressive Era, it continued to purchase coca leaves from Peru, removing the cocaine from the leaves but keeping what was left over as a flavoring extract. By the end of the twentieth century it was the single largest purchaser of legally imported coca leaves in the United States.

Yet, in the 1960s, Coke feared that an international counternarcotics crackdown on cocaine would jeopardize their secret trade with Peruvian cocaleros, so they did a smart thing: they began growing coca in the United States. With the help of the US government, a New Jersey chemical firm, and the University of Hawaii, Coca-Cola launched a covert coca operation on the island of Kauai. In 1965, growers in the Pacific paradise reported over 100 shrubs in cultivation.

How did this bizarre Hawaiian coca operation come to be? How, in short, did Coca-Cola become the only legal buyer of coca produced on US soil? The answer, I discovered, had to do with the company’s secret formula: not it’s unique recipe, but its peculiar business strategy for making money—what I call Coca-Cola capitalism.

What made Coke one of the most profitable firms of the twentieth century was its deftness in forming partnerships with private and public sector partners that helped the company acquire raw materials it needed at low cost. Coca-Cola was never really in the business of making stuff; it simply positioned itself as a kind of commodity broker, channeling ecological capital between producers and distributors, generating profits off the transaction. It thrived by making friends, both in government and in the private sector, friends that built the physical infrastructure and technological systems that produced and transported the cheap commodities needed for mass-marketing growth.

In the case of coca leaf, Coca-Cola had the Stepan chemical company of Maywood, New Jersey, which was responsible for handling Coke’s coca trade and “decocainizing” leaves used for flavoring extract (the leftover cocaine was ultimately sold to pharmaceutical firms for medicinal purposes). What Coke liked about its relationship with Stepan was that it kept the soft drink firm out of the limelight, obfuscating its connection to a pesky and tabooed narcotics trade.

But Stepan was just part of the procurement puzzle. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) also played a pivotal role in this trade. Besides helping to pilot a Hawaiian coca farm, the US counternarcotics agency negotiated deals with the Peruvian government to ensure that Coke maintained access to coca supplies. The FBN and its successor agencies did this even while initiating coca eradication programs, tearing up shrubs in certain parts of the Andes in an attempt to cut off cocaine supply channels. By the 1960s, coca was becoming an enemy of the state, but only if it was not destined for Coke.

In short, Coca-Cola—a company many today consider a paragon of free-market capitalism—relied on the federal government to get what it wanted.

An old Coca-Cola bottling plant showing some of the municipal pipes that these bottlers tapped into. Courtesy of Robert W. Woodruff Papers, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Coke’s public partnerships extended to other ingredients. Take water, for example. For decades, the Coca-Cola Company relied on hundreds of independently owned bottlers (over 1,000 in 1920 alone) to market its products to consumers. Most of these bottlers simply tapped into the tap to satiate Coke’s corporate thirst, connecting company piping to established public water systems that were in large part built and maintained by municipal governments.

The story was much the same for packaging materials. Beginning in the 1980s, Coca-Cola benefited substantially from the development of curbside recycling systems paid for by taxpayers. Corporations welcomed the government handout, because it allowed them to expand their packaging production without taking on more costs. For years, environmental activists had called on beverage companies to clean up their waste. In fact, in 1970, 22 US congressmen supported a bill that would have banned the sale of nonreturnable beverage containers in the United States. But Congress, urged on by corporate lobbyists, abandoned the plan in favor of recycling programs paid for by the public. In the end, Coke and its industry partners were direct beneficiaries of the intervention, utilizing scrap metal and recycled plastic that was conveniently brought to them courtesy of municipal reclamation programs.

In all these interwoven ingredient stories there was one common thread: Coke’s commitment to outsourcing and franchising. The company consistently sought a lean corporate structure, eschewing vertical integration whenever possible. All it did was sell a concentrated syrup of repackaged cheap commodities. It did not own sugar plantations in Cuba (as the Hershey Chocolate Company did), coca farms in Peru, or caffeine processing plants in New Jersey, and by not owning these assets, the company remained nimble throughout its corporate life. It found creative ways to tap into pipes, plantations, and plants managed by governments and other businesses.

In the end, Coca-Cola realized that it could do more by doing less, extending its corporate reach, both on the frontend and backend of its business, by letting other firms and independent bottlers take on the risky and sometimes unprofitable tasks of producing cheap commodities and transporting them to consumers.

This strategy for doing business I have called Coca-Cola capitalism, so-named because Coke modeled it particularly well, but there were many other businesses, in fact some of the most profitable of our time, that followed similar paths to big profits. Software firms, for example, which sell a kind of information concentrate, have made big bucks by outsourcing raw material procurement responsibilities. Fast food chains, internet businesses, and securities firms—titans of twenty-first century business—have all demonstrated similar proclivities towards the Coke model of doing business.

Thus, as we look to the future, we would do well to examine why Coca-Cola capitalism has become so popular in the past several decades. Scholars have begun to debate the causes of a recent trend toward vertical disintegration, and while there are undoubtedly many causes for this shift, it seems ecological realities need to be further investigated. After all, one of the reasons Coke chose not to own commodity production businesses was because they were both economically and ecologically unsustainable over the long term. Might other firms divestment from productive industries tied to the land be symptomatic of larger environmental problems associated with extending already stressed commodity networks? This is a question we must answer as we consider the prudence of expanding our current brand of corporate capitalism in the years ahead.

Bart Elmore is an assistant professor of global environmental history at the University of Alabama. He is the author of “Citizen Coke: An Environmental and Political History of the Coca-Cola Company” (available to read for free for a limited time) in Enterprise and Society. His forthcoming book, Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism, is due out with W. W. Norton in November of 2014.

Enterprise & Society offers a forum for research on the historical relations between businesses and their larger political, cultural, institutional, social, and economic contexts. The journal aims to be truly international in scope. Studies focused on individual firms and industries and grounded in a broad historical framework are welcome, as are innovative applications of economic or management theories to business and its context.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What Coke’s cocaine problem can tell us about Coca-Cola Capitalism appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBumblebees in English gardensMonetary policy, asset prices, and inflation targetingSuper Bowl ads and American civil religion

Related StoriesBumblebees in English gardensMonetary policy, asset prices, and inflation targetingSuper Bowl ads and American civil religion

Can the Académie française stop the rise of Anglicisms in French?

It’s official: binge drinking is passé in France. No bad thing, you may think; but while you may now be looking forward to a summer of slow afternoons marinating in traditional Parisian café culture, you won’t be able to sip any fair trade wine, download any emails, or get any cash back – not officially, anyway.

How so? Are the French cheesed off with modern life? Well, not quite: it’s the “Anglo-Saxon” terms themselves that have been given the cold shoulder by certain linguistic authorities in favour of carefully crafted French alternatives. And if you approve of this move, then here’s a toast to a very happy journée internationale de la francophonie on 20 March. But just who are these linguistic authorities, and do French speakers really listen to them?

The Académie française

You may not be aware that 2014 has been dedicated to the “reconquête de la langue française” by the Académie française, that esteemed assembly of academics who can trace their custody of the French language back almost four centuries to pre-revolutionary France. While the recommendations of the académie carry no legal weight, its learned members advise the French government on usage and terminology (advice which is, to their chagrin, not always heeded). The thirty-eight immortels, as they are known (there are currently two vacant fauteuils), maintain that la langue de Molière has been under sustained attack for several generations, from a mixture of poor teaching, poor usage, and – most notoriously – “la montée en puissance de l’anglo-saxon”. Although French can still hold its own as a world language in terms of number of speakers (220 million) and learners (it’s the second most commonly taught language after – well, no prizes for guessing), this frisson of fear is understandable if we cast our eyes back to 1635, when the Académie was formally founded.

At that time, French enjoyed considerable cachet throughout Europe as the medium of communication par excellence for the cultural elite. But in France, where regional languages such as Breton and Picard were widely spoken, the académiciens had the remarkably democratic ambition of pruning and purifying their national tongue in order that it should be clear, elegant, and accessible to all. They nobly undertook to “draw up certain rules for [the] language, and to render it pure, eloquent, and capable of dealing with arts and sciences”. In practical terms, this meant writing a dictionary.

The Académie française, Paris.

Looking up le mot juste

Published nearly 60 years later in 1694, the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française was not the first dictionary of the French language, but it was the first of its kind: a dictionary of “words, rather than things”, which focused on spelling, syntax, register, and above all, “le respect du bon usage”. Intended to advise the honnête homme what (and what not) to say, it has survived three centuries and nine editions to finally appear online as a fascinating record of the evolution of the French language.

You may be tempted to draw parallels between the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française (DAF) and our own Oxford English Dictionary (OED), but in many ways they are fundamentally different. In the English-speaking world, there is no equivalent of the Académie française and its sweeping, egalitarian vision. The OED was conceived (centuries after the DAF) as a practical response to the realization that “existing English language dictionaries were incomplete and deficient” and is generally regarded as a descriptivist dictionary, recording the ways in which words are used, while the DAF is more of a prescriptivist dictionary, recording the ways in which words should be used. While the OED’s entries are liberally sprinkled with literary citations as examples of usage, the DAF has no need for them. And as a historical dictionary, the OED doesn’t ever delete a word from its (digital) pages, whereas the DAF will happily remove words deemed obsolete (and is quite transparent about doing so). Consequently, the OED, with roughly 600,000 headwords, is around ten times bigger than the DAF.

Faux pas in French

However, the digital revolution has allowed both dictionaries to reach out to their readers, albeit in tellingly different ways. While the OED staff appeal to the public for practical help with antedating, the académiciens, faithful to their four-hundred-year-old mission, have pledged to respond to their readers’ questions on usage and grammar in an online forum dedicated to “des esclaircissemens à leurs doutes”.The result, “Dire, Ne Pas Dire”, is a fascinating read, ranging from semantics (can a shaving mirror actually be called a shaving mirror, given that it is not used as a razor?) to politics (a debate over the validity of the trendy English phrase “save the date” on wedding invitations). And it doesn’t take long to see that the Académie’s greatest bête noire by far is the “menace” of the “péril anglais”.

Plus ça change

There may be a sense of déjà-vu here for the académiciens, because grievances over the Anglicization of the French language date back to at least 1788. Some stand firm in their belief that French, with its rich syntax, logical rules, and “impérieuse précision de la pensée”, will eventually triumph again over English, a “divided” language which, in their opinion, risks fragmenting anarchically due its very global nature: “It may well be that, a century from now, English speakers will need translators to be able to understand each other.” Touché.

But many have reached an impasse of despair: the académiciens regularly deplore the “scourges” inflicted on their native tongue by “la langue anglaise qui insidieusement la dévore de l’intérieur” (the English language which is insidiously devouring it from the inside), rendering much French discussion into a kind of “jargon pseudo-anglais” with terms like updater, customiser, and être blacklisté brashly elbowing their way past their French equivalents (mettre à jour, personnaliser, and figurer sur une liste noire respectively). One immortel fears that the increasing use of English is pushing French into a second-class language at home, urging francophones to go on strike.

The Commission générale de terminologie et de néologie

And académiciens are not alone in their attempts to halt the sabotage of the French language: other authorities, with considerably more legal power, are hard at work too. The French government has introduced various pieces of legislation over the past forty years, the most far-reaching being the 1994 Toubon Law which ruled that the French language must be used – although not necessarily exclusively – in a range of everyday contexts. Two years later, the French ministry of culture and communication established the Commission générale de terminologie et de néologie, whose members, supervised by representatives from the Académie, are tasked with creating hundreds of new French words every year to combat the insidious and irresistible onslaught of Anglo-Saxon terminology. French speakers point out that in practice, most of these creations are not well-known and, if they ever leap off the administrative pages of the Journal officiel, rarely survive in the wild. There are, however, a few notable exceptions, such as logiciel and – to an extent – courriel, which have caught on: the English takeover is not quite yet a fait accompli.

Vive la différence

It’s worth remembering, too, that language change does not always come from a conservative – or a European – perspective. It was the Québécois who pioneered the feminization of job titles (with “new” versions such as professeure and ingénieure) in the 1970s. Two decades later, the Institut National de la Langue française in France issued a statement giving its citizens carte blanche to choose between this “Canadian” approach and the “double-gender” practice (allowing la professeur for a female teacher, for example). While the Académie française maintain that such “arbitrary feminization” is destroying the internal logic of the language, research among French speakers shows that the “double-gender” approach is gaining in popularity, but also that where there was once clarity, there is now uncertainty over usage.

Perhaps yet more controversially, France has recently outlawed that familiar and – some might argue – quintessentially French title, Mademoiselle, on official documentation: “Madame” should therefore be preferred as the equivalent of “Monsieur” for men, a title which does not make any assumptions about marital status”, states former Prime Minister François Fillon’s ostensibly egalitarian declaration from 2012.

Après moi, le déluge

Meanwhile, the English deluge continues, dragging the French media and universities in its hypnotic wake, both of which are in thrall to a language which – for younger people, at least – just seems infinitely more chic. But the académiciens need not abandon all hope just yet. The immortel Dominique Fernandez has proposed what seems at first like a completely counter-intuitive suggestion: if the French were taught better English to start with, then they could “leave [it] where it ought to be, in the English language, and not in Anglicisms, that hybrid ruse of ignoramuses,” he asserts. Perhaps compulsory English for all will actually bring about an unexpected renaissance of the French language, the language of resistance, in its own home. And if we all end up speaking English instead? Well, c’est la vie.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Joanna Rubery is an Online Editor at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: The Académie française via iStockphoto via OxfordWords blog.

The post Can the Académie française stop the rise of Anglicisms in French? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?Farmily album: the rise of the felfieBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4

Related StoriesHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?Farmily album: the rise of the felfieBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4

Ice time

By Jamie Woodward

On 23rd September 1840 the wonderfully eccentric Oxford geologist William Buckland (1784–1856) and the Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz (1809–1873) left Glasgow by stagecoach on a tour of the Scottish Highlands. The old postcard below provides a charming hint of what their horse-drawn jaunt through a tranquil Scottish landscape might have been like in the autumn of 1840. It shows the narrow highway snaking through a rock-strewn Hell’s Glen not far from Loch Fyne. Even though Buckland had already recognised glacial features in Dumfriesshire earlier that month, it can be argued that this was the first glacial fieldtrip in Britain. These geological giants were searching for signs of glacial action in the mountains of Scotland and they were not disappointed.

Image from edinphoto.org.uk. Used with permission.

This tour was an especially important milestone in the history of geology because it led to the first reports of the work of ancient glaciers in a country where glaciers were absent. Agassiz wasted no time in communicating these revelations to the geological establishment. The following is an extract from his famous letter to Robert Jameson (1774–1854) that was published in The Scotsman on 7th October 1840 and in The Manchester Guardian a week later:

“… at the foot of Ben Nevis, and in the principal valleys, I discovered the most distinct morains and polished rocky surfaces, just as in the valleys of the Swiss Alps, in the region of existing glaciers ; so that the existence of glaciers in Scotland at earlier periods can no longer be doubted.”

These discoveries initiated new debates about climate change and the extent to which the actions of glaciers had been important in shaping the British landscape. These arguments continued for the rest of the century. In 1840 Buckland and Agassiz had no means of establishing the age of the glaciation because the scientific dating of landscapes and geological deposits only became possible in the next century. They could only state that glaciers had existed at “earlier periods”.

At the end of the previous century, in his Theory of the Earth (1795), Scotsman James Hutton became the first British geologist to suggest that the glaciers of the Alps had once been much more extensive. He set out his ideas on the power of glaciers and proposed that the great granite blocks strewn across the foothills of the Jura had been dumped there by glaciers. This was several decades before Agassiz put forward his own grand glacial theory. Hutton did not speculate about the possibility of glaciers having once been present in the mountains of his homeland.

Following the widespread use of radiocarbon dating in the decades after the Second World War, it was established that the last Scottish glaciers disappeared about 11,500 years ago at the close of the last glacial period. Many of the cirques of upland Britain are now occupied by lakes and peat bogs which began to form soon after the ice disappeared. By radiocarbon dating the oldest organic deposits in these basins, it was possible to establish a minimum age for the last phase of glaciation. A good deal of this work was carried out by Brian Sissons and his graduate students at the University of Edinburgh. Sissons published The Evolution of Scotland’s Scenery in 1967.

Geologists now have an array of scientific dating methods to construct timescales for the growth and decay of past glaciers. The most recent work in some of the high cirques of the Cairngorms led by Martin Kirkbride of Dundee University has argued that small glaciers may have been present in the Highlands of Scotland during the Little Ice Age – perhaps even as recently as the 18th Century. These findings are hot off the press and were published in January 2014 at the same time as The Ice Age: A Very Short Introduction. Kirkbride’s team employed a relatively new geological dating technique that makes use of the build-up of cosmogenic isotopes in boulders and bedrock exposed at the Earth’s surface. This allows direct dating of glacial sediments and landforms.

Photograph from Tarmachan Mountaineering. Used with permission.

So in 2014 we have a fresh interpretation of parts of the British landscape and a new debate about the climate of the Scottish mountains during The Little Ice Age. This latest chapter in the study of Scottish glaciation puts glacial ice in some of the highest mountains about 11,500 years later than previously thought. The Scottish uplands receive very heavy snowfalls as the superb photograph of Beinn Mheadoin peak (1182 m) and Shelter Stone Crag in the centre of the Cairngorms range very clearly shows. Many snow patches with a northerly aspect survive until late summer. But could small glaciers have formed in these mountains as recently as The Little Ice Age? Some glacier-climate models calibrated with cooler summers suggest that they could.

This latest work is controversial and, like the findings of Agassiz and Buckland in 1840, it will be contested, in due course, in the academic literature. Whatever the outcome of this latest glacial debate, it is undoubtedly a delightful notion that only a century or so before Buckland and Agassiz made their famous tour, and when a young James Hutton, the father of modern geology, was beginning to form his ideas about the history of the Earth, a few tiny glaciers may well have been present in his own backyard.

Jamie Woodward is Professor Physical Geography at The University of Manchester. He has published extensively on landscape change and ice age environments. He is especially interested in the mountain landscapes of the Mediterranean and published The Physical Geography of the Mediterranean for OUP in 2009. He is the author of The Ice Age: A Very Short Introduction. He tweets @Jamie_Woodward_ providing a colourful digital companion to The Ice Age VSI.

Jamie Woodward will be appearing at the Oxford Literary Festival on Saturday 29 March 2014 at 1:15 p.m. in the Blackwell’s Marquee to provide a very short introduction to The Ice Age. The event is free to attend.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) With permission from edinphoto.org.uk (2) With permission from Tarmachan Mountaineering

The post Ice time appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThinking more about our teethNations and liberalism?Will caloric restriction help you live longer?

Related StoriesThinking more about our teethNations and liberalism?Will caloric restriction help you live longer?

March 20, 2014

Will caloric restriction help you live longer?

The idea of extending life expectancy by modifying diet originated in the mid-20th century when the effects of caloric restriction were found. It was first demonstrated on rats and then confirmed on other model organisms. Fasting activists like Paul Bragg or Roy Walford attempted to show in practice that caloric restriction also helps to prolong life in humans.

For a long time the crucial question in this research concerned finding a molecular mechanism that demonstrated how caloric restriction might promote longevity. The discovery of such a mechanism is possible with very simple organisms whose genetics were well understood and whose genes could be switched on or off. For example, the budding yeast, nematodes and fruit flies are windows into the complicated genetics of longevity. Several discoveries have been made in recent years, including resveratrol, sirtuins, insulin growth factor, methuselah gene, Indy mutation.

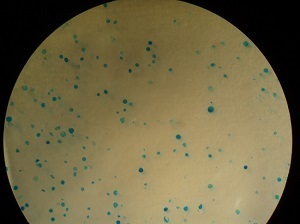

Capillary feeding assay, developed in the laboratory of Seymour Benzer at Caltech, which allows tracking of consumed food

The effects of caloric restriction may be more complex than anticipated. Protein-to-carbohydrate ratio has been shown to play a large role in diet response. Additionally, medical concerns about danger of refined sugar and fructose for health have gained recognition, typically relating to high-mortality diseases and disorders, such as diabetes, diabetic complications, and obesity.

Following an initial study of antioxidant system of the budding yeast, we turned our sights to biogerontological studies after the discovery of possible molecular mechanism of resveratrol action in yeast model. However, we quickly realized that the fruit fly (specifically Drosophila) is likely a better model because we could then also investigate behavioural outcome and food intake. How would caloric restriction and the amount of carbohydrates in the diet affect the longevity of fruit flies?

Food with a dye enables measurement of food intake

Analysis of faecal spots left by fruit flies allows life-long measurement of medium ingestion

We posed the question of whether the type of carbohydrate fed would affect mortality in fruit flies, including fructose, glucose, a plain mixture of the two, and sucrose (a disaccharide composed from monomers, fructose and glucose). We wanted to see whether fructose is a “poison” or “toxicant” as can be found in publications or popular lectures of Professor Robert Lustig.

We found, surprisingly, that flies fed on sucrose ceased to lay eggs after several weeks of adult life, and sucrose shortened their mean life span at all concentrations above 0.5% total carbohydrate. On the other hand, we found that fruit flies were quite well adapted for living on fructose. Furthermore, this effect was not observed for plain mixture of fructose and glucose.

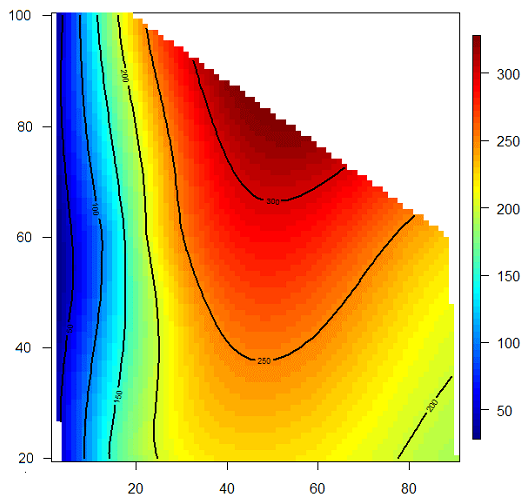

Dietary response surface where concentrations of protein and carbohydrate ingested are put on X and Y axes, while Z is any physiological parameter which may depend on protein-to-carbohydrate ratio

The results were surprising because sucrose is routinely used in laboratory recipes of fly food. Lower fecundity on sucrose was also unexpected. However, we realized that the effects we had observed in the study would not lead us to immediate sugar denialism. The fly food used in the study was quite different from usual fly food, and in human context resembled likely a spicy marmalade diet.

Nonetheless, it is known that egg laying in Drosophila is promoted by dietary proteins (taken up mostly from yeasts). The diets of our flies contained a very small amount of protein, and yet this deficiency did not interfere with egg laying on monosaccharides while disaccharide sucrose caused dramatic loss in fecundity.

Is it possible to apply our current data to human physiology? It seems to be rather difficult to build assumptions on healthy diet of humans based on the data obtained for insects. The insect physiology with their specific development hormones, probably different metabolism and metabolic demands stands far away from that of humans. Nevertheless, the general message is that the influence of diet on ageing cannot be reduced to simply amount of calories, or macronutrient balance. The quality of nutrients, the micronutrients, the peculiarities of digestion, including gut microbiota, should also be taken into account. While scientists are often forced to simplify models, to gain a better understanding of molecular, biochemical, genetic, and physiological grounds of ageing, our understanding would likely benefit from bringing a variety of researchers, from ecologists and mathematicians, into the discussion.

Dr. Dmytro Gospodaryov is Assistant Professor and Dr Oleh Lushchak is a researcher at the Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology at Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University. They are the co-authors of “Specific dietary carbohydrates differentially influence the life span and fecundity of Drosophila melanogaster” in The Journal of Gerontology: Biological Sciences. Their research interests comprise the influence of dietary components on survival, oxidative modification of proteins, and roles of different redox-active compounds within cells.

The Journals of Gerontology® were the first journals on aging published in the United States. The tradition of excellence in these peer-reviewed scientific journals, established in 1946, continues today. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A® publishes within its covers The Journal of Gerontology: Biological Sciences and The Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images courtesy of the authors. Do not use without permission.

The post Will caloric restriction help you live longer? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBumblebees in English gardensFrom art to autism: a Q&A with Uta FrithAn interview with I. Glenn Cohen on law and bioscience

Related StoriesBumblebees in English gardensFrom art to autism: a Q&A with Uta FrithAn interview with I. Glenn Cohen on law and bioscience

Grand Piano: the key to virtuosity

“Play one wrong note and you die!” The recently-released feature film Grand Piano, directed by Eugenio Mira and starring Elijah Wood, is an artsy and rather convoluted thriller about classical music and murder. Wood plays a concert pianist plagued by an overwhelming case of stage fright; it doesn’t help that there’s a sniper in the audience threatening to assassinate both him and his glamorous wife if he misses a single note in the “unplayable” composition that has proven to be his undoing before. Looking past the silly plot, however, it’s revealing to see how this movie plays into a number of persistent popular culture tropes around Romantic pianism. It’s even possible to read the story as a parable about the pressures of a performing career in the world of classical music today.

First consider the grand piano itself as portrayed in the film’s evocative opening credits. The camera takes us deep into this menacing mechanical contraption of piano keys, metal strings, tuning pins, and tiny gears turning like clockwork while the accompanying music thuds, slithers, and slashes with ominous import. Wait, grand pianos don’t have tiny gears turning inside. This must be quite an unusual piano, as the first scene of the film clarifies.

Grand Piano stars Elijah Wood as a concert pianist contending with both stage fright and a sniper in the audience. Image: Elijah Wood in Grand Piano, a Magnet Release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures via Magnet Releasing.

We see moving guys in a creepy old mansion rolling this instrument out of storage while the thunder rumbles overhead on a blustery overcast day. There’s always been something mysterious about grand pianos, since the large black coffin-like case hides the mechanics inside from the listener’s view as the pianist plays on one side of it. There’s some kind of ghost in the machine of the Romantic pianist’s intriguing instrument.

There’s also the ghost of the pianist’s deceased mentor, Godureaux, the eccentric teacher who had composed that unplayable composition and designed that mysterious instrument. He stares out from large posters in the lobby looking like a cross between Rachmaninoff and Rasputin. “La Cinquette” is the title of his notoriously difficult and “terrifying” piece that has something especially problematic about its last four bars. Maybe the title refers to the fact that it is Godureaux’s op. 5, or that it requires “five little” fingers of each hand to play it to perfection. (The film’s closing credits scroll over an unexpected delight: the song “Ten Happy Little Fingers” from the 1953 film musical The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T, written by Theodor Seuss Geisel, a.k.a. Dr. Seuss. Displeasure over wrong notes begins quite early in the young pianist’s career.) Fortunately our hero-virtuoso is equipped with “the fastest, most agile fingers of any pianist alive,” indeed there are only “a few people who can play it, who can move their fingers that fast and spread them that wide.”

Fingers take on symbolic meanings around the male virtuoso pianist; these appendages have frequently been represented in popular culture as signifiers of a muscular technique and masculinity. “You need to ease up!” the sniper instructs our hero as he begins to play that challenging piece. “You’re going to tire out your fingers!” Indeed, this performance is framed as our hero’s opportunity not only to redeem his career, but his identity as well: “I’m offering you the chance to become your own man again.” Elijah Wood’s wide-eyed stare easily conveys the crisis of masculinity implied by the pianist’s uncertainty over his playing technique, while his body language conveys a nervousness and an impotence (see his scared-stiff kiss with his wife at intermission) that also reflect these familiar tropes.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Wood has spoken publicly about the off-screen technical challenges of making this film. At a discussion session at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, he described his own skills on the instrument remembered from piano lessons when he was young, but also how he worked with pianist Mariam Nazarian in Los Angeles for three weeks to learn to make it look like he knew how to play; in Barcelona he worked with the hand double for this film (the credits list Toni Costa as hand double, and John Lenehan as the soundtrack recording pianist). Wood recalls practicing first on a real piano (“the sound helped me to know if I was on the right track”) and then filming to the recording on a dummy piano, which made it possible to act out his gestures without worrying if he were hitting all the correct notes. It was also useful for Wood to watch a video of the real pianist’s hands from the pianist’s point-of-view, then to imitate what he saw as he watched his own hands on the keyboard. Some critics have noted the impressive “hand-synching” in this film production (see Eric Snider’s write-up) and the actor’s learning curve with this playback technique (see Clark Collis’ interview). One of the movie’s selling points, in fact, is our persistent fascination with virtuoso technique (see Harleigh Foutch’s interview): “So the main thing I walked away from this movie thinking was how damn difficult this part must have been for you.”

Serious pianists and pianophiles will probably roll their eyes over the inane plot and the unrealistic playing scenes in this movie. Which concertos have tutti sections so long that the pianist can run off-stage so often for urgent business? Why wouldn’t the professional pianist play from memory? Perhaps there ought to be a law against texting while playing! The moral of the story might be about that perfectionism we’ve come to expect in this era of note-perfect recordings. “I want you to play the most flawless concert of your life,” the sniper exhorts the virtuoso. “Just consider me the voice in your head telling you that good is not good enough tonight.” The conductor tries to comfort the anxious pianist by saying about the audience, “If you’re going to play music this dense, you’re going to hit a wrong note, and they won’t know. They never do.” The critics-as-snipers might notice and mark down your technique, but the real crisis is the Romantic pianist’s musical reproducibility. As the conductor points out, “you make your living playing stuff other people write.” The concert virtuoso has become “a genius puppet,” as he puts it, a technological wonder that stays close enough to the notes of the score and just far enough from the great recordings to sound like a unique epitome of a time-honored tradition. “Do you really want to be the thousandth guy to give me a respectable Bach,” the conductor asks, “‘cause you can keep that. I don’t need respectable.” This pianist saves his life by literally changing the score.

Ivan Raykoff is Associate Professor of Music in the interdisciplinary arts program at Eugene Lang College, The New School for Liberal Arts in New York. He is author of Dreams of Love: Playing the Romantic Pianist.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Grand Piano: the key to virtuosity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesComposer Hilary Tann in eight questionsHarry Nilsson and the MonkeesBeyond Ed Sullivan: The Beatles on American television

Related StoriesComposer Hilary Tann in eight questionsHarry Nilsson and the MonkeesBeyond Ed Sullivan: The Beatles on American television

From art to autism: a Q&A with Uta Frith

Dame Uta Frith was the neuroscientist who first recognised autism as a condition of the brain rather than the result of cold parenting. Here she takes Lance Workman on a journey through her collection of memories.

Lance Workman: I believe you initially began your studies with history of art in Germany, but then became interested in psychology, and autism in particular.

Uta Frith: At school I was not particularly good at science subjects and much better arts and languages. No wonder these were the subjects I was expected to study at university. But looking back, this is a common situation for girls to be in, and it was a bit of a trap. Actually, I had many diverse interests. So, one thing I love to tell girls in a similar situation is that you can escape the trap. You can change your mind about what you’d like to study. The school I went to in Germany gave me a nice all-round education, including nine years of Latin and six years of Greek. I absolutely loved it. I dreamt my future would be to study ancient civilisations – finding treasures and deciphering texts in some long-lost language! By comparison, art history is far more down-to-earth. The art history courses offered at my university were fascinating. They allowed me to explore different artists, different times, places and materials. But I was very curious about what was on offer elsewhere. I went to lots of different lectures and remember my timetable being completely full up. This seemed to me the best thing about being a student: soaking up learning while being inspired by the commitment that eminent scholars bring to their subjects.

Uta Frith

At that point I only had a very nebulous and indeed misguided idea of what psychology was about. But I happened to drift into a lecture on analysis of variance. Far from being put off, the idea that you could use stats to measure psychological abilities strangely appealed to me. For the first time I learned that it was possible to do experiments about how people remember things, and how they solved problems, or rather how they failed to solve them. So I went to the psychology department and asked if they would take me on as a student. I ended up doing more and more psychology and less and less art history, mainly because the psychology course was well structured with an exam at the end. This certainly gave me some focus. It occurred to me gradually that it was the mind I was interested in, and even more gradually that this included the brain. As part of the psychology course I took similar courses to the medics. I have to admit that the physiology lab classes were rather tough for me. There were some alarming moments involving spinal frogs. Better by far were the lectures and case demonstrations in the university psychiatric clinic. This was more than exciting – it was the most intellectually thrilling experience that I ever had. The professor was renowned for his ability to present cases to students. He clearly enjoyed himself in these demonstrations, and the patients he selected played along good-naturedly. I very much wanted to understand what was the matter with them, why they suffered from invisible and intangible phenomena. So, if anything, that was what got me totally hooked into psychology.

Lance Workman: You came to England around this time. How did that come about?

Uta Frith: Well, I needed to learn English to read the textbooks and journals – and so I came to London. I found I liked it even more than Paris, and that was saying something. I went to visit the Institute of Psychiatry, because I had heard of Hans-Jürgen Eysenck, who was the head of department. I was extremely taken with his books that were debunking the woolly end of psychology and psychoanalysis. Like everyone else I had read Freud and swallowed it wholesale. But Eysenck’s books threw a different light on things. Where was the evidence for Freud’s theories? If the evidence was in the patients that were cured, then it was very thin indeed. If the patients did not get better, then apparently this was because they resisted. Something was not quite right here. It seemed a suspiciously circular argument. I saw Professor Eysenck only very briefly, but he seemed happy enough for me to stay around to see if I could do odd jobs. One of the lecturers, Reg Beech, gave me some data to analyse from an experiment he had done with patients who had obsessive compulsive disorder.

My job was quite basic – correlations, that sort of thing – but I enjoyed doing it. It was an exciting environment where psychologists tested hypotheses, and treated patients, not with psychotherapy, but with methods based on learning theory. I found out that there was a unique course in clinical psychology, and I was longing to be able to do this course. So I went to the head – Monte Shapiro – and asked if he would take me on. Amazingly, he did, and I am for ever grateful to him. Then I had to tell my parents. I knew I imposed a heavy financial burden on them, because the exchange rate between the pound and the Deutschmark was extremely poor at that time. However, they were always unbelievably supportive of me and of anything I decided to do. So they accepted my sudden change of plan.

At some point during the course I found out about autism. I was completely fascinated as soon as I met the first autistic child, and have been ever since. By sheer luck, the Institute of Psychiatry was the place to be for anyone interested in autism – Mike Rutter, Lorna Wing, Neil O’Connor and Beate Hermelin; all these heroes were there at that time.

Lance Workman: Things were really very different then. What was the prevailing view on autism during the 1960s and 70s in terms of causes?

Uta Frith: The prevailing view was that something in psychosocial relations had gone wrong during early development, and that this caused the state of autism. Still, at the Institute there was also the view that autism should be seen in the context of mental deficiency. This was a term for conditions thought to be due to brain pathology. To me, however, the autistic children didn’t look like other children with mental disabilities. Was there a hidden intelligence? Many of the children I met had no language. Could they perhaps learn to speak? Would they then grow out of their autism? The children with Down’s syndrome I met did have language and were quite social – but the autistic children were so strange, so different.

Lance Workman: You once described autistic children as being like the ones in John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos – later made into the film Village of the Damned.

Uta Frith: This is one of the romantic images about autistic children I have toyed with. I freely admit that some of my fascination was fed by romantic notions. At first I thought it would be very difficult to study autistic individuals in a strict experimental fashion. Perhaps case studies were the only way. Then I happened to read a paper by Beate Hermelin and Neil O’Connor and realised that it was after all possible to do experiments with these children. I plucked up courage and managed to talk to them a couple of times. One day they asked me whether I would like to do a PhD. I didn’t hesitate for a second. I immediately knew that this is what I wanted to do.

This whole area of research into disorders of cognitive development was only just beginning, and I happened to be in the right place. When people asked what I was doing and I said I studied autistic children, they invariably thought I was studying artistic children! When I did explain about autism, they generally thought it was odd to study something that was so very rare.

Lance Workman: Things changed radically, with you as one of the people that suggested autistic children couldn’t mentalise. Did that happen overnight or was it an idea that gradually emerged?

Uta Frith: The ground for the idea was well prepared in many ways. The rigorous experimental approach to autism pioneered by Hermelin and O’Connor was one thing, and so was the finding that the really critical feature of autism was not people’s aloofness, but their strange failure in reciprocal communication. ‘Theory of mind’ was an idea which just then surfaced and inspired developmental psychologists Heinz Wimmer and Josef Perner. It only needed these strands bringing together. There was a sort of insight moment: If young children needed a ‘theory of mind’ in order to understand pretend play, as Alan Leslie argued, then it was possible that autistic children who had recently been found to lack pretend play, did not have a ‘theory of mind’. Simon Baron-Cohen started his PhD at this time and carried out the critical experiments. One of them has become a classic experiment with the Sally-Ann False Belief Task. Simon found that autistic children aged 9–10 years failed this task when children with Down’s syndrome and ordinary five year-olds succeeded. John Morton suggested the novel term ‘mentalising’, short for ‘the ability to use mental states such as intentions and beliefs to predict behaviour of others and self’. So we all continued to work on the idea that mentalising failure might be key to the social impairments in autism.

Autistic Teen

Lance Workman: You found that specific deficit?

Uta Frith: Yes we did find a specific deficit in social cognitive processing, and we designed other tests to show that there was no general cognitive impairment that would explain the results. But it was very difficult to get these ideas accepted. We wanted to claim that there was a neural basis to this specific deficit and that this might help us to identify a cause of autism in the brain. At the time brain imaging had just emerged. It was almost like science fiction. Here was an amazing technique that promised to make thinking in the brain visible. What about thinking about mental states? Of course, I could not have dreamt of doing brain imaging studies on my own. But fortunately [my husband] was very much involved in the early development of functional imaging techniques, and he was brave enough to give it a go. His colleagues have told me since that, at the time, they thought he was completely mad to do this. It took about 10 years for other centres to take up these crazy ideas and pursue them further. Today it is taken for granted that there is a mentalising system in the brain. What we still don’t know, however, is in what way this system is or is not working in autism. This has proved very elusive. I still remember that we expected to get an immediate and clear answer to this question. How naive!

Lance Workman: You have also suggested that autistic individuals might have some cognitive advantages?

Uta Frith: At least 10% have outstanding talents, and possibly as many as 30% have superior abilities in quite specific areas, and it is important to explain these. My hope was that one single cause might explain these special abilities and at the same time the undeniable weaknesses that show up in tests such as ‘Comprehension’. That’s how I arrived at the theory of weak central coherence. Weak central coherence is when you can’t see the wood for the trees. This can be both an advantage and a disadvantage. There are tasks where it is important to resist the pull of the big picture, for example when you need to find a hidden object. Amitta Shah, another of my brilliant PhD students, showed that autistic children are good at finding hidden figures, and can easily see how to segment a picture in the Block Design Test. On the other hand, they may often miss the main point of a question in the ‘Comprehension’ test. Then Francesca Happé came along and showed that you don’t have to be autistic to have a detail-focused processing style. Sarah White, a more recent PhD student, found that it is only a subgroup of autistic children who show weak central coherence. To my mind these are the children I used to see long ago, very much like the ones Kanner described. They are the classic cases that still exist, but now they are only a small part of the whole autism spectrum. We still don’t know how to explain the amazing talent seen in some autistic individuals, but one ingredient may be the ability to zoom in easily on a small detail and stay there until it is mastered by countless repeats.

Lance Workman: The film Rainman brought autism to the attention of the public in the 1980s. Do you think that was a good portrayal of an autistic individual?

Uta Frith: It was an outstanding portrayal, even though the character of Rainman was based on a composite of a number of autistic people. Apparently, Dustin Hoffman studied these people carefully, and managed to convey for the first time their endearing naivety and their charming social faux pas. The film increased the awareness of the condition, especially in adults. It may also have increased the unrealistic expectation of outstanding talent. Most importantly, it helped to lessen any feelings of fear and dread about autism.

Lance Workman: You mentioned your husband earlier, Chris Frith. When I interviewed him, one question I asked was How do you feel about working with your wife? I’m curious if I ask you the same question about him to see whether you give the same answer?

Uta Frith: It’s a marvellous feeling. We have always talked to each other about our work and have read each other’s papers in early drafts. We have always been interested in each other’s work, and it helped that it was different. It was no accident that we were in separate departments and were pursuing different projects. It is only really in recent years that we have been working together. We found that we enjoy it! I think writing together has worked very much to my advantage. Chris often starts drawing out a structure and puts down rough ideas. Then I just have to do a bit of editing and expanding. It seems like a free ride.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Psychologist.

Uta Frith is a developmental psychologist working at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London. She is author of Autism and Talent, Autism: A Very Short Introduction, and Autism: Mind and Brain.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Uta Frith at an Ada Lovelace Day editathon in the Royal Society. Photo by Katie Chan. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Autistic Teenage Girl. Photo by Linsenhejhej. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post From art to autism: a Q&A with Uta Frith appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBumblebees in English gardensMemories of Andy CalderBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4

Related StoriesBumblebees in English gardensMemories of Andy CalderBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4

Bumblebees in English gardens

Urban gardens are increasingly recognised for their potential to maintain or even enhance biodiversity. In particular the presence of large densities and varieties of flowering plants is thought to support a number of pollinating insects whose range and abundance has declined as a consequence of agricultural intensification and habitat loss. However, many of our garden plants are not native to Britain or even Europe, and the value of non-native flowers to local pollinators is widely disputed.

We tested the hypothesis that bumblebees foraging in urban gardens preferentially visited plants species with which they share a common biogeography (i.e. the plants evolved in the same regions as the bees that visit them). We did this by conducting summer-long surveys of bumblebee visitation to flowers seen in front gardens along a typical Plymouth street, dividing plants into species that naturally co-occur with British bees (a range extending across Europe, north Africa, and northern Asia – collectively called the Palaearctic by biologists), those that co-occur with bumblebees in other regions such as southern Asia, and North and South America (Sympatric), and plants from regions (Southern Africa and Australasia) where bumblebees are not naturally found (Allopatric).

Rather than discriminating between Palaearctic-native and non-native garden plants when taken together, bees simply visited in proportion to flower availability. Indeed, of the six most commonly visited garden plants, only one Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea – 6% of all bee visits) was a British native and only three garden plants were of Palaearctic origin (including the most frequently visited species Campanula poscharskyana (20.6% of visits) which comes from the Balkans). The remaining ‘most visited’ garden plants were from North America (Ceanothus 11% of visits) and Asia (Deutzia Spp 7% of visits), while the second most visited plant, Hebe × francisciana (18% of visits) is a hybrid variety with parents from New Zealand (H. speciosa) and South America (H. elliptica).

However a slightly different pattern emerges when we consider the behaviour of individual bumblebee species. This is important because we know from work done in natural grassland ecosystems that different bumblebees vary greatly in their preference for native plant species. Some bumblebees visit almost any flower, while others seem to have strict preferences for certain plants. The latter group (‘dietary specialists’) include bees with long tongues that allow them to access the deep flowers of plants belonging to the pea and mint families that short-tongued bees cannot. One of these dietary specialists, the aptly named ‘garden bumblebee’ (Bombus hortorum), showed a strong preference for Palaearctic-origin garden plant species (78% of flower visits by this species); although we also saw this species feeding on the New Zealand-native, Cordyline australis. Even more interesting was the fact that our most common species the ‘buff-tailed bumblebee’ (B. terrestris) appeared to favour non-Palaearctic garden plants (70% of all visits) over garden plants with which it shares a common evolutionary heritage (i.e. Palaearctic plants). So it seems that any preference for plants from ‘home turf’ varies between different bumblebees; just like in natural grasslands, some bees are fussy about where they forage, and others not.

So what should gardeners do to encourage pollinators? Our results suggest that it is not simply a question of growing native species even if this is desirable for other reasons, but that any ‘showily-flowered’ plant is likely to offer some forage reward. There are caveats, however. Garden plants that have been subject to modification to produce ‘double’ flowers that replace or obscure the anthers and carpels that yield pollen and nectar (e.g. Petunias, Begonias, and Hybrid Tea roses) are known to offer little or no pollinator reward. A spring to autumn supply of flowers of different corolla lengths is important to provide both long- and short-tongued bumblebees with nectar. A reliable pollen supply is particularly important during nest founding through to the release of queen and male bees at the end of the nest cycle. Roses and poppies are obvious choices, but early season willows also offer pollen for nest-founding queens. Potentially most crucial of all however, are the pea family as they offer higher quality pollen vital for the success of the short-nest cycle, specialist bumblebees such as B. hortorum. It is also important that access to what gardeners refer to as ‘weeds’ is available. Where possible gardeners can set aside a small area to allow native brambles, vetches, dead nettles, and clovers to grow, but as long as some native weed species are available in nearby allotments, parks, or other green spaces, we suggest that a combination of commonly-grown garden plants will help support our urban bumblebees for future generations.

Dr Michael Hanley is Lecturer in Terrestrial Ecology at the University of Plymouth. He is co-author of the article ‘Going native? Flower use by bumblebees in English urban gardens’, which is published in the Annals of Botany.

Annals of Botany is an international plant science journal that publishes novel and substantial research papers in all areas of plant science, along with reviews and shorter Botanical Briefings about topical issues. Each issue also features a round-up of plant-based items from the world’s media – ‘Plant Cuttings’.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bumblebee on apple tree. By Victorllee [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Bumblebees in English gardens appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn interview with I. Glenn Cohen on law and bioscienceNeanderthals may have helped East Asians adapting to sunlightConservation physiology of plants

Related StoriesAn interview with I. Glenn Cohen on law and bioscienceNeanderthals may have helped East Asians adapting to sunlightConservation physiology of plants

March 19, 2014

Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4

Apart from realizing that each of the three words in question (beggar, bugger, and bigot) needs an individual etymology, we should keep in mind that all of them arose as terms of abuse and sound somewhat alike. The Beguines, Beghards, and Albigensians have already been dealt with. Before going on, perhaps I should say that Johannes Laurentius Mosheim’s book De Beghardis et Beguinabus Commentarius, published by Weidmann in Leipzig, 1790, is still a most useful work to consult. The first chapter (a hundred pages) is devoted to the names Beguina, Beguinus, Begutta, and Beghardus. If I am not mistaken, this commentary, unlike his Ecclesiastic History…, has not been translated into any major European language and is available only in the original Latin.

Mosheim listed the following hypothetical sources on the derivation of Beguine and the rest: bonus-garten “good cultivator;” St. Begga, the founder of a cloister; Lambert le Bègue (the stammerer), the founder of the order; the word beguin occurring in the old dictionaries by Cotgrave and Florio (“skullcap; a kind of coarse gray cloth poor religious men wore”); the Latin adjective benignum “benign” (neuter); the German verb beginnen “begin” (because the beguttæ were about to enter monastic life); the verbs began ~ biggan “worship”; the verb began “to beg,” either as members of the mendicant orders do or perhaps from their earnest prayer to God; and finally, bi Gott. Some of those hypotheses have circulated much later (the bi Gott tale proved to be especially popular) and have been discussed in my posts. Others are too naïve to deserve our attention today, and still others, by modern scholars, will also be known to the readers of this miniseries and of the essay “Nobody wants to be a bigot.” Those interested in the way from “earnest praying” to mocking names may look up the origin of Lollard.

Mosheim listed the following hypothetical sources on the derivation of Beguine and the rest: bonus-garten “good cultivator;” St. Begga, the founder of a cloister; Lambert le Bègue (the stammerer), the founder of the order; the word beguin occurring in the old dictionaries by Cotgrave and Florio (“skullcap; a kind of coarse gray cloth poor religious men wore”); the Latin adjective benignum “benign” (neuter); the German verb beginnen “begin” (because the beguttæ were about to enter monastic life); the verbs began ~ biggan “worship”; the verb began “to beg,” either as members of the mendicant orders do or perhaps from their earnest prayer to God; and finally, bi Gott. Some of those hypotheses have circulated much later (the bi Gott tale proved to be especially popular) and have been discussed in my posts. Others are too naïve to deserve our attention today, and still others, by modern scholars, will also be known to the readers of this miniseries and of the essay “Nobody wants to be a bigot.” Those interested in the way from “earnest praying” to mocking names may look up the origin of Lollard.

The core of the problem is the similarity between the three words: bigot, beggar, and bugger. It can but need not be accidental. In the 2012 post, I made much of Maurice Grammont’s connection between bigot and Albigenses and wondered why such a good idea had escaped lexicographers. Since then I have run into several earlier passing references to this connection, which means that Grammont was not the first to trace bigot to the name of the religious order. Yet I have not seen this etymology in any dictionary. It won’t be too bold to suggest that bugger takes us to Bulgarian in its French guise (possibly confused with a homonymous swearword), bigot to Albigenses, and beggar to Beguine. The semantic root is the same, namely “heretic,” hence “pervert; scoundrel; scum,” with further specification to “fanatic” (bigot), “sodomite” (bugger), and “mendicant” (beggar). But, to repeat, it may not be fortuitous that all three words sound so much alike. The reason for the similarity seems to be the onomatopoeic complex b-g ~ b-k (the hyphen stands for any short vowel).

In various Romance Standard languages and especially dialects one finds words like bécqueter “to peck,” bégayer “to stammer” (a stammerer “pecks” at words, as it were, unable to pronounce them), bégauder “to vomit,” and Old French le gesier begaie “to split.” Part of the scene is dominated by the word for “goat” and nouns, verbs, and adjectives more or less clearly derived from it, including devices resembling the goat (either its frame or two horns). Such are bigue and bique “goat” (even the diminutive bigot “goat” and the adjective bigot “lame, limping” have been recorded); bigorna “bigot” and “lame”; bigorner “to squint.” More troublesome is Italian sbigottire “dismay, bewilder” (s-, as always, goes back to ex-) and French faire bigoter “irritate.” One is reminded of the English idiom to get one’s goat. Did it surface as a bilingual joke among the French or less probably Italian Americans? The few current explanations of this phrase strike me as fanciful. Related to sbigottire are bigollone “simpleton, fool; idler” (contrary to common sense, domestic animals—goats, cows, and rams—often epitomize foolishness, at least in idioms) and, to prove the opposite, bigatto “cunning.”

Still another bigot means “mattock; hoe.” In its vicinity we find biga ~ viga “beam’ (along with Italian biga “chariot”) and a whole world of long, elongated, split in two, and cylindrical objects: bigot (masculine plural) “spaghetti,” bigolini “short hair,” bigo “worm,” bigolo “penis” (of course: is there any verbal sphere without “penis,” or membrum virile, as the well-behaved linguists of the past glossed it?), numerous words denoting “moustache,” and quite possibly French bigoudi “hair curler” (the descendant of curl papers). My sources have been Leo Spitzer, Gerhard Rolfs, and Francesca M. Dovetto, who cite dozens of such words.

Only the names for “goat” seem to be fully transparent from an etymological point of view. Goats are often called big-big and bik-bik, even though for bleating mek and its likes occur more often than b-words. Some paths from “goat” are more easily recoverable than others. But if we stay with the idea that big- attaches itself to “stupid animals,” fools, and idlers, we will realize that, once a derogatory term for “heretic” was coined, it received strong reinforcement from many sound symbolic or sound imitative formations with negative characteristics. In such words vowels vary frequently, so that big-, beg-, and bug- were always at speakers’ “beck and call.” It was easy to humiliate a person by calling him a beggar or a bugger, regardless of the precise sense implied. The inspiration came from France. Very soon the offensive names found a new home in the Dutch-speaking world and from there traveled to England.

The words for “beak” and “pecking” can also be traced to the sound imitative complexes discussed above, which should not surprise us. While dealing with onomatopoeia, one cannot apply the terms “related” and “homonymous.” The complex b-g ~ b-k is almost universal, and its range is impossible to predict. In the Germanic languages, it often refers to swelling, as in Engl. big, bag, and bug. Swollen things burst, make a lot of noise, and frighten people; hence bugaboo, bogey, and the rest. As we have seen, the b-g ~ b-k group is used widely in coining “goat words” and terms of abuse. I would add bicker, the theme of still another recent post, to the b-k list. Its immediate source seems to have been the German, originally perhaps Dutch, word bickel, a gambling term. It would be risky to say definitely what exactly bickel meant, because in the Middle Ages the same word often meant the board game and the die (a classic example is the Latin gloss alea “a die”). Rather probably, bickel is another coinage of French descent, but where exactly it belongs among so many b-g ~ b-k nouns would be hard to tell.

We will now let the curtain fall over the history of religious prejudice, bigotry, persecution, and gambling. It is customary to admire the world of medieval and early modern carnivals. Carnivals certainly existed as a supplement to cruelty and an unbridled gratification of animal instincts. To some very small extent, this world has been subdued, but the evil words we have inherited do not allow us to forget how people lived many centuries ago. There are few windows to the past like etymology.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Johann Lorenz von Mosheim (1694-1755), Kupferstich / copper engraving 1735. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 4 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 2Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 3Monthly gleanings for February 2014

Related StoriesBeggars, buggers, and bigots, part 2Beggars, buggers, and bigots, part 3Monthly gleanings for February 2014

Ovid the naturalist

Ovid was born on the 20th of March (two thousand and fifty-some years ago): born on the cusp of spring, as frozen streams in the woods of his Sulmo cracked and melted to runnels of water, as coral-hard buds beaded black stalks of shrubs, as tips of green nudged at clods of earth and rose, and rose, and released tumbles of blooms.

The extraordinariness of living-change: this would be the life-breath of Ovid’s great Metamorphoses. In his poem are changes as real as being born, falling in love for the first time, or dying. In it, too, are changes that seem fantastical: a boy becomes a spotted newt; a girl becomes a myrrh. But is it so much more surprising to see a feather sprout from your fingertip than to look between your legs, at twelve, and find a new whorl of hairs? Or feel, growing in your belly, another small body? Many of even the fantastic transformations in Ovid’s poem are equations for natural change, as if to make us see anew. To portray his transmutations, both fantastic and real, Ovid studied closely the natural shifts in forms all around him.

He looked at the effects of warm blood rising within skin, for instance, or sunrays streaming through cloth. Here’s Arachne, caught in a moment of brashness:

A sudden blush filled her face–

she couldn’t control it–but vanished as fast,

just as the sky grows plum when dawn first comes

but with sunrise, soon glows white.

Atalanta, mosaic, 3rd or 4th century. Scala / Art Resource, NY

Or Atalanta as she runs races to avoid being married:

A flush runs over the girl’s pearly skin,

as when a red awning over a marble hall

suffuses it with the illusion of hue.

Several mythical girls in Ovid’s poem turn into springs. How render this? Byblis cries uncontrollably once her brother has refused her love:

Just as drops weep from the trunk of a pine tree

or oily bitumen oozes from soil

or ice loosens to liquid under the sun

when a warm breeze gently breathes from the west,

so Byblis slowly resolved into tears, slowly

she slipped into stream.

Cyane is overcome, too, when she can’t save a girl who’s been stolen:

In her silent mind grew

an inconsolable wound. Overwhelmed by tears,

she dissolved into waters whose mystic spirit

she’d recently been. You could see limbs go tender,

her bones begin bending, her nails growing soft.

Her slimmest parts were the first to turn liquid,

her ultramarine hair, legs, fingers, and feet

(for the slip from slender limbs to cool water

is slight). Then her shoulders, back, hips, and breasts

all melted and vanished in rivulets.

At last instead of living blood clear water flowed

through her loosened veins, with nothing left to hold.

And how might new forms come to be? Ovid considered coral:

But a sprig of seaweed–still wet with living pith–

touches Medusa’s head, feels her force, and hardens,

stiffness seeping into the strand’s fronds and pods.

The sea-nymphs test the wonder on several sprigs

and are so delighted when it happens again

they throw pods into the sea, sowing seeds for more.

And even now this is the nature of coral.

At the touch of air it petrifies: a supple

sprig when submarine in air turns into stone.

For a new flower to be born and be a yearly testament to Venus’ grief when her lover, Adonis, is gored to death, Ovid thought of peculiarly animate earth:

Venus sprinkled

scented nectar on Adonis’ blood. With each drop

the blood began to swell, as when bubbles rise

in volcanic mud. No more than an hour had passed

when a flower the color of blood sprang up,

the hue of a pomegranate hiding ruby seeds

inside its leathery rind.

And in the story of Myrrha, Ovid elides psychological, naturalistic, and fantastic transformations. Myrrha has seduced her father and, pregnant, fled into the wilds. When her child is about to be born, she cannot bear to live inside her own skin, so she prays:

“If alive I offend the living

and dead I offend the dead, throw me from both zones:

change me. Deny me both life and death.”

Some spirit was open to her words, some god

willing to grant her last prayer. For soil spread

over her shins as she spoke, and her toenails split

into rootlets that sank down to anchor her trunk.

Her bones grew dense, marrow thickened to pith,

her blood paled to sap, arms became branches

and fingers twigs; her skin dried and toughened to bark.

Now the growing wood closed on her swollen womb

and breast and was just encasing her throat–

but she couldn’t bear to wait anymore and bent

to the creeping wood, buried her face in the bark.

Her feelings have slipped away with her form

but still Myrrha weeps, warm drops trickling from the tree.

Yet there’s grace in these tears: the myrrh wept by the bark

keeps the girl’s name, which will never be left unsaid.

Then the baby that was so darkly conceived grew

inside its mother’s bark until it sought a way

out; on the trunk, a belly knob, swollen.

The pressure aches, but Myrrha’s pain has no words,

no Lucina to cry as she strains to give birth.

As if truly in labor the tree bends and moans

and moans more, the bark wet with sliding tears.

Then kind Lucina comes and strokes the groaning

limbs, whispering words to help the child slip free.

The bark slowly cracks, the trunk splits, and out slides

the live burden: a baby boy wails.

A panoply of metamorphoses, fantastical and real, shifting from life to loss to life again. And the baby just born is Adonis, who, though adored by Venus, will die, and his blood will sink into the earth–but then bubble up as an anemone, and it will be springtime, again, and again.

Jane Alison is author of Change Me: Stories of Sexual Transformation from Ovid. Her previous works on Ovid include her first novel, The Love-Artist (2001) and a song-cycle entitled XENIA (with composer Thomas Sleeper, 2010). Her other books include a memoir, The Sisters Antipodes (2009), and two novels, Natives and Exotics (2005) and The Marriage of the Sea (2003). She is currently Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Virginia. She is speaking at the Viriginia Book Festival today at 4:00 p.m.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ovid the naturalist appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“You’ll be mine forever”: A reading of Ovid’s AmoresLove: First sights in OvidGloomy terrors or the most intense pleasure?

Related Stories“You’ll be mine forever”: A reading of Ovid’s AmoresLove: First sights in OvidGloomy terrors or the most intense pleasure?

Monetary policy, asset prices, and inflation targeting

The standard arguments against monetary policy responding to asset prices are the claims that it is not feasible to identify asset price bubbles in real time, and that the use of interest rates to restrain asset prices would have big adverse effects on real economic activity. So what happened with central banks and house prices prior to the financial crisis of 2007-2008?

Looking in detail at what the Federal Reserve Board (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) thought and said about house prices from the beginning of the 2000s, it appears that the Fed was so convinced of the standard line (monetary policy should not respond to asset prices but just stand ready to mop up if a bubble bursts) that it did not allocate much time or resources to discussing what was happening.

The BoE, on the other hand, while equally committed to that orthodoxy, felt the need to argue it out, at least up till 2005, and a number of speeches by Steve Nickell and others explained why they believed that the rises in house prices were a response to changes in the fundamentals (notably, the much lower levels of inflation and interest rates from the mid-1990s) and were therefore not a cause for concern. But after 2005 the BoE seems to have lost interest in the issue even to that extent.

Bank of England headquarters, London