Oxford University Press's Blog, page 829

March 31, 2014

“A peaceful sun gilded her evening”

On 31 March 1855 – Easter Sunday – Charlotte Brontë died at Haworth Parsonage. She was 38 years old, and the last surviving Brontë child. In this deeply moving letter to her literary advisor W. S. Williams, written on 4 June 1849, she reflects on the deaths of her sisters Anne and Emily.

My dear Sir

I hardly know what I said when I wrote last—I was then feverish and exhausted—I am now better—and—I believe—quite calm.

Anne Brontë by Charlotte Brontë, 1845

You have been informed of my dear Sister Anne’s death—let me now add that she died without severe struggle—resigned—trusting in God—thankful for release from a suffering life—deeply assured that a better existence lay before her—she believed—she hoped, and declared her belief and hope with her last breath.—Her quiet Christian death did not rend my heart as Emily’s stern, simple, undemonstrative end did—I let Anne go to God and felt He had a right to her.

I could hardly let Emily go—I wanted to hold her back then—and I want her back hourly now—Anne, from her childhood seemed preparing for an early death—Emily’s spirit seemed strong enough to bear her to fullness of years—They are both gone—and so is poor Branwell—and Papa has now me only—the weakest—puniest—least promising of his six children—Consumption has taken the whole five.

For the present Anne’s ashes rest apart from the others—I have buried her here at Scarbro’ to save papa the anguish of return and a third funeral.

I am ordered to remain at the sea-side a while—I cannot rest here but neither can I go home—Possibly I may not write again soon—attribute my silence neither to illness nor negligence. No letters will find me at Scarbro’ after the 7th. I do not know what my next address will be—I shall wander a week or two on the east coast and only stop at quiet lonely places—No one need be anxious about me as far as I know—Friends and acquaintance seem to think this the worst time of suffering—they are sorely mistaken—Anne reposes now—what have the long desolate hours of her patient pain and fast decay been?

Why life is so blank, brief and bitter I do not know—Why younger and far better than I are snatched from it with projects unfulfilled I cannot comprehend—but I believe God is wise—perfect—merciful.

I have heard from Papa—he and the servants knew when they parted from Anne they would see her no more—all try to be resigned—I knew it likewise and I wanted her to die where she would be happiest—She loved Scarbro’—a peaceful sun gilded her evening.

Yours sincerely

C. Brontë

The Oxford World’s Classics edition of Charlotte Brontë’s Selected Letters is edited by Margaret Smith, with an introduction by Janet Gezari.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Anne Brontë – drawing in pencil by Charlotte Brontë, 1845. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “A peaceful sun gilded her evening” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEntitling early modern women writersAn Irish literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsA classic love story reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Related StoriesEntitling early modern women writersAn Irish literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsA classic love story reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

March 30, 2014

The political economy of policy transitions

The long fight to end slavery, led by William Wilberforce, among many others, culminated in Britain with the enactment of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. This Act made provision for a payment of £20 million (almost 40% of the British budget at the time) in compensation to plantation owners in many British colonies — about US$21 billion in present day value. Moreover, only slaves below the age of six were initially freed while others were re-designated as “apprentices”, who were to be freed in two stages in 1838 and 1840. Wilberforce and many other abolitionists accepted that compensation and phased implementation was required to ensure enactment of the legislation, particularly by the House of Lords where plantation owners were strongly represented among the aristocracy.

Whenever governments change policies — whether tax, expenditure, or regulatory policies — even when the changes are on net socially beneficial, there will typically be losers. There will be people who have made investments predicated on or even deliberately induced by the pre-reform set of policies. Very few policy changes make somebody better off and nobody worse off according to their own subjective valuations (the economist’s concept of Pareto efficiency). The issue of whether and when to mitigate the costs associated with policy changes — whether through explicit government compensation, grandfathering, or phased or postponed implementation — is ubiquitous across the policy landscape.

Changes in land use regulations often exempt existing non-conforming structures. Environmental regulations, such as energy efficiency requirements for motor vehicles, are often phased in over time. More stringent requirements for qualification for entry into various professions often grandfather existing members of these professions. Stricter gun control laws often grandfather existing gun owners. In post-conflict nation building exercises, a qualified line in the sand is often drawn under past atrocities committed by antagonists.

Unfinished portrait of the MP and abolitionist William Wilberforce by the English artist Thomas Lawrence, dated 1828. National Portrait Gallery, London.

The need to take transition cost mitigation strategies seriously, as a matter of political economy, stands in relatively sharp contrast to two long-standing traditions in economics which tend to marginalize this issue. Economists, from a normative welfare economics perspective, often publish academic studies that document the gross inefficiencies associated with various existing public policies. However, it is unrealistic to assume that once these inefficiencies are revealed, well-intentioned but unenlightened political representatives will immediately espouse the proposed reforms, or that alternatively an aroused citizenry will appropriately discipline venal political leaders that have been captured by rent-seeking interest groups.

An alternative positive tradition in economics — public choice theory — does take politics seriously but tends to view the existing policy outcomes of the political process as the best we can achieve in a world not populated by angels. An austere version of this theory offers few prospects that existing political equilibria can be disrupted; the iron triangle of incestuous relationships between politicians, regulators/bureaucrats, and rent-seeking interest groups is largely impermeable to change. This view is hard to square with the privatization of many state-owned enterprises and the deregulation of many industries in many countries from the 1980s onwards, and the dramatic growth in environmental, health and safety, and other forms of social regulation over this period, often over the opposition of concentrated interests.

I view the political process as much more fluid and malleable. Significant policy reforms are politically feasible with political leadership committed to judicious combinations of transition cost mitigation policies and astute framing of issues so as to engage not only the interests but also the values of a broad cross-section of a country’s citizens.

Michael J. Trebilcock is Professor of Law and Economics at the University of Toronto School of Law and the author of Dealing with Losers: The Political Economy of Policy Transitions. He specializes in law and economics, international trade law, competition law, economic and social regulation, and contract law and theory. He has won awards for his work, including the 1989 Owen Prize by the Foundation for Legal Research for his book, The Common Law of Restraint of Trade, which was chosen as the best law book in English published in Canada in the past two years.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The political economy of policy transitions appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUnlearned lessons from the McMartin Preschool caseVictims of slavery, past and presentDopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brain

Related StoriesUnlearned lessons from the McMartin Preschool caseVictims of slavery, past and presentDopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brain

Dopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brain

Before I wrote my last blog entry, I got a Twitter account to start tracking reactions to that entry. I was surprised to see that people that I had never met favorited my post. Some even retweeted it. Within a day, I started to check my email to see if someone else had picked up on it. It felt so good to know that people that I had never met from all over the world were paying attention to me.

The addictiveness of Twitter is not specific to me. There have been articles about getting Justin Bieber to follow you as a form of addiction. But the problem is much more pervasive than that.

Many of the symptoms associated with cocaine addiction are popping up in people who are simply on the Internet. The toxic effects of cocaine addiction have been known for years. Studies find that rats will self-administer cocaine to the point of death over a period of time. The pharmacological effects are also well known; cocaine magnifies the effects of dopamine chemically. The interesting part is that Twitter, Facebook, and video games seem to have a similar effect as well. Thus, dopamine is part of a reward system.

Interestingly, dopamine is also known to play a role in the brain systems that are used to control our mental focus. Recent work has found that dopamine plays a role in the connection between the frontal areas that are involved in cognitive control and the posterior areas of the brain involved in processing incoming information from the senses.

And here, work in bilingual literature might have found an antidote to the plague of Internet addiction. Ellen Bialystok and her colleagues have found that bilinguals tend to be better at switching between tasks and at using inhibition — what researchers call cognitive control. Theoretical work by Stocco, Pratt and colleagues proposes that the use of two languages on a regular basis helps to strengthen the use of brain areas that are highly linked to dopamine. Many of the same frontal areas have been shown to be involved in control in bilinguals. Thus, it is logical to conclude that dopamine which leads to increased addiction may also be involved in giving bilinguals an edge in focusing. It is a classic U-shaped function where too little and too much are bad but somewhere in the middle is just right.

So what happens when a bilingual faces the onslaught of Internet addiction. Is s/he more resistant? I don’t know the ultimate answer to that question. But I was struck by how quickly the Twitter craze that had me checking my page every minute faded. Perhaps it is the four languages that I have learned that serve to protect me more and allow me to stop the urge to check my page again. Today, I am happy to report that I have written this blog entry with the understanding that any benefit will come long term. And I have my language learning history to thank for that.

But, please, favorite this; please, retweet it. Please, please, please!

Arturo Hernandez is currently Professor of Psychology and Director of the Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience graduate program at the University of Houston. He is the author of The Bilingual Brain. His major research interest is in the neural underpinnings of bilingual language processing and second language acquisition in children and adults. He has used a variety of neuroimaging methods as well as behavioral techniques to investigate these phenomena which have been published in a number of peer reviewed journal articles. His research is currently funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development. Read his previous blog posts and follow him on Twitter @DrAEHernandez.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Apple’s iPhone 4 with a busy home screen on the grass with chamomile flowers. © ZekaG via iStockphoto.

The post Dopamine, Twitter, and the bilingual brain appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy nobody dreams of being a professorWhat the bilingual brain tells us about language learningThe never-ending assault by microbes

Related StoriesWhy nobody dreams of being a professorWhat the bilingual brain tells us about language learningThe never-ending assault by microbes

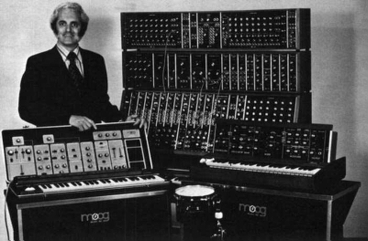

Eight facts about the synthesizer and electronic music

The invention of the synthesizer in the mid-20th century inspired composers and redesigned electronic music. The synthesizer sped up the creation process by combining hundreds of different sounds, and composers were inspired to delve deeper into the possibilities of electronic music.

1. Electronic music was first attempted in the United States and Canada in the 1890s. Its creation process was difficult. To create just a few minutes of music, with perhaps a hundred different sounds, could take weeks to finalize.

2. The first true synthesizer was released to the public in 1956. It was made up of an array of electronic tone generators and processing devices that controlled the nature of the sounds.

3. That synthesizer played itself in traveling patterns that could be repeated or not. It was controlled by a system of brush sensors that responded to patterns of pre-punched holes on a rotating paper roll.

4. The most well-known and celebrated electronic pieces in the 1950s are Eimert’s Fünf Stücke, Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge, Krenek’s Spiritus Intelligentiae Sanctus, Berio’s Mutazioni, and Maderna’s Notturno.

Robert Moog and his synthesizer via Wikimedia Commons

5. The first electronic concert was given in the Museum of Modern Art, NY on 28 October 1953 by Ussachevsky and Luening.

6. Two Americans, Robert Moog and Donald Buchla, created separate companies to manufacture synthesizers in the 1960s. Robert Moog’s synthesizer was released in 1965 and is considered a major milestone for electronic music.

7. They were followed by others and soon synthesizers that were voltage-controlled and portable were available for studio and on stage performances.

8. In the 1980s, commercial synthesizers were produced on a regular basis. Yamaha released the first all-digital synthesizer in 1983.

Maggie Belnap is a Social Media intern at Oxford University Press. She attends Amherst College.

Oxford Reference is the home of reference publishing at Oxford. With over 16,000 photographs, maps, tables, diagrams and a quick and speedy search, Oxford Reference saves you time while enhancing and complementing your work.

Subscribe to OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Eight facts about the synthesizer and electronic music appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMark Vail remembers synth pioneer Bob MoogWomen of 20th century musicEntitling early modern women writers

Related StoriesMark Vail remembers synth pioneer Bob MoogWomen of 20th century musicEntitling early modern women writers

March 29, 2014

What is academic history for?

Writing on Saturday in The Age, popular historian Paul Ham launched a frontal assault on “academic history” produced by university-based historians primarily for consumption by their professional peers.

In his article, Ham muses on whether these writings ever “enlightened or defied anyone or just pinged the void of indifference” Lamenting its alleged inaccessibility and narrow audience, Ham asks with incredulity:

What is academic history for?

Ham’s is only the latest in a steady stream of attacks castigating historians and other scholars for their inability to engage the general public effectively. New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof sent American academia into a collective apoplectic fit with a February column imploring academics to make a greater contribution to policy debates as public intellectuals.

Less convinced than Ham of the purposeful obscurantism of academic writing, Kristof nonetheless met with a sharp rebuke from the academy, which defended its track record for engagement and faulted Kristof for pointing only to the highest profile venues to judge scholars’ participation in debates beyond the Ivory Tower.

As political scientist Corey Robin observes:

there are a lot of gifted historians. And only so many slots for them at The New Yorker.

Scholar-turned-Buzzfeed-contributor Anne Helen Petersen notes that, in combination with a shortage of academic jobs, “the rise of digital publishing has ironically yielded an exquisite, flourishing community of public intellectuals”, as The Conversation itself attests.

But the opening up of a raft of new, online avenues for smart, serious commentary and analysis has no corollary in the book business. If Kristof’s cardinal sin is an elitist reluctance to look beyond the most venerable establishment periodicals, Ham’s central failure is a seemingly wilful blindness to the role market forces play in the publishing industry.

Academic historians fail to make their way into Amazon’s Top 100 list not because they are unable or, as Ham asserts, unwilling to write accessibly. I doubt there are many academic historians who, whether out of passion for their subject or sheer ambition, would turn down the opportunity to enjoy a moment in the limelight.

But the path of popular history is closed to most historians because of the very subjects of their investigation. No amount of finesse with the written word would have put my first book, on the history of medicine and public health in Soviet Kazakhstan, on the shelves of Dymock’s. The publishing of popular history is driven not by how scholars write, but by what readers are willing to buy.

A Baroque library, Prague. © Jorge Royan / http://www.royan.com.ar / CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia

Is there value to scholarship that falls outside the narrow parameters of what is financially feasible for a commercial press? Of course there is, not least because scholarly studies, though often narrowly conceived, nonetheless inform the work of those engaged in topics of broader interest.

Take, for example, the work of popular American presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin. She investigates first-hand the relevant primary sources, but she also supports her analysis by drawing on works that delve deeply into the more slender crevices of history. The research of perhaps hundreds of historians informs her understanding of the world in which her protagonists operate.

No-one would expect every scientist to produce work that was at once highly sophisticated and accessible to the lay reader. There is a depth and detail of analysis that is only of interest to the specialist but necessary for the field’s advancement; we value American astrophysicist Neil Degrasse Tyson’s ability to distill that vast, dense body of scholarship and present it to us with crystal clarity on the TV series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey.

And when he turns to evolutionary biology, far from his own area of expertise, he leans entirely on the research of others. Similarly, Kearns Goodwin and her fellow popular historians rely on the solid, vetted works of academic historians to tell their more accessible stories for popular audiences. That act of translation does not render the original scholarship superfluous, but rather attests to its impact.

Publications are, of course, only one measure of public engagement. Through work in the classroom, academic historians translate and interpret scholarly writings for and alongside students.

They are also out in the community, sharing their expertise in public talks designed for general audiences at museums, at schools, at retirement communities, and elsewhere, such as at the Making Public Histories Seminar Series run by Monash University and the History Council of Victoria and held at the State Library of Victoria.

Not only are academic historians clearly far more engaged with the public than they appear at a first, blinkered glance, but there seems to be ample room for and value in a wide range of intellectual activity. Perhaps it’s time to set aside pot shots and straw men and recognise that the changing terrain of public engagement allows for a multiplicity of voices and forms of expression.

It’s not all about making the bestseller list.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Paula A. Michaels is Senior Lecturer of history and international studies at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia and is the author of Curative Powers: Medicine and Empire in Stalin’s Central Asia and most recently Lamaze: An International History.

Disclosure statement: Paula Michaels does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What is academic history for? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive interesting facts about John TylerThe American Red Cross in World War IUnlearned lessons from the McMartin Preschool case

Related StoriesFive interesting facts about John TylerThe American Red Cross in World War IUnlearned lessons from the McMartin Preschool case

Five interesting facts about John Tyler

John Tyler remains one of the most interesting, active, and constitutionally significant presidents we have ever had.

To begin with, he is the first vice president to be elevated to the presidency because of the death of the incumbent, William Henry Harrison. Harrison died 31 days after his inauguration in 1841. Many congressional leaders and the cabinet believed that the vice president, Tyler, did not automatically become the president upon Harrison’s death. They argued that he merely became the acting president or remained the vice president but was eligible to use some of the powers of the presidency with the full power and authority of the office. Tyler contested the claim. In his first meeting with Harrison’s cabinet, he convinced them to accept the legitimacy of his claim to take the presidential oath. He persuaded skeptical congressional leaders as well. In doing so, he established a practice and understanding that was later enshrined within the Constitution in the Twenty-fifth Amendment and is still followed to this day.

Second, John Tyler is the only American president whose party expelled him while he was the president. Tyler had been a life-long Democrat who left his party to become the running mate of William Henry Harrison, a Whig, in 1840. After Tyler became the president, Whigs did not trust him. After he exercised power in ways that Whigs did not approve, they formally expelled him from the party. For the remainder of his presidency, Tyler was, as he himself said, a man “without a party.”

Third, throughout his presidency, Tyler battled successfully against congressional efforts to thwart a number of unique presidential powers. As a result, he successfully consolidated the nominating, removal, and veto powers of future presidents.

Fourth, Tyler was also the only president to have had virtually all of his cabinet resign in protest over his actions. When Tyler vetoed a tariff bill, which his entire cabinet thought he should sign, all but Secretary of State Daniel Webster resigned in protest. Tyler happily accepted their resignations and replaced all but Webster with people who actually supported him politically.

Fifth, Tyler set a record for the numbers of cabinet and Supreme Court nominations that were rejected or forced to be withdrawn. In fact, he made eight nominations to fill two Supreme Court vacancies, only one of which the Senate confirmed.

As a bonus, Tyler also took unilateral action to clear the path for Texas to become a state. Though the Senate refused to ratify a treaty which would have made Texas statehood possible, Tyler got a majority in the House and a majority in the Senate to approve an annexation bill. Tyler signed the annexation bill three days before leaving office.

Through all of these and other actions, Tyler made the presidency stronger, but at the cost of his own political fortunes. He left office widely politically unpopular and ended his days as a member of the Confederate Congress.

Michael Gerhardt is Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. A nationally recognized authority on constitutional conflicts, he has testified in several Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and has published five books, including The Forgotten Presidents and The Power of Precedent. Read his previous blog posts on the American presidents.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: “Official White House Portrait of John Tyler” by George Peter Alexander Healy, February 1859. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Five interesting facts about John Tyler appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe American Red Cross in World War IFive things you didn’t know about Franklin PierceOral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nuns

Related StoriesThe American Red Cross in World War IFive things you didn’t know about Franklin PierceOral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nuns

The American Red Cross in World War I

President Barack Obama has proclaimed March 2014 as “American Red Cross Month,” following a tradition started by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1943. 2014 also marks the 100-year anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War in Europe. Although the United States would not officially enter the war until 1917, the American Red Cross (ARC) became deeply involved in the conflict from its earliest days. Throughout World War I and its aftermath, the ARC and its volunteers carried out a wide array of humanitarian activities, intended to alleviate the suffering of soldiers and civilians alike.

In honor of American Red Cross Month, and in commemoration of the First World War’s centennial, here’s a list of things you might not have known about the World War I era history of the American Red Cross:

In honor of American Red Cross Month, and in commemoration of the First World War’s centennial, here’s a list of things you might not have known about the World War I era history of the American Red Cross:

(1) On 12 September 1914, just over a month after the First World War erupted in Europe, the American Red Cross sent its first relief ship to the continent. Christened the Red Cross, the ship carried units of physicians and nurses, surgical equipment, and hospital supplies to seven warring European nations. This medical aid reached soldiers on both sides of the conflict.

(2) After the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the ARC’s intervention in Europe expanded enormously. Over the next several years, the ARC’s leaders established humanitarian activities in roughly two-dozen countries in Europe and the Near East. The organization provided emergency food and medical relief on the battlefields and on the European home front, but ARC staff and volunteers also took on more constructive projects. They built hospitals, health clinics and dispensaries, libraries, playgrounds, and orphanages. They organized public health campaigns against diseases like typhus and tuberculosis. They took steps to reform sanitation in many countries and introduced nursing schools in several major cities. The ARC’s efforts for Europe, in other words, went well beyond immediate material relief to include long-term, comprehensive social welfare projects.

(3) During World War I, the American Red Cross experienced astronomical growth. On the eve of war, ARC membership hovered around 10,000 US citizens. By 1918, the last year of the war, roughly 22 million adults and 11 million children – approximately 1/3 of the total US population at that time – had joined the American Red Cross and contributed at least $1.00 to the organization.

(4) In 1917, the wartime leaders of the American Red Cross established an auxiliary body for US children—the Junior Red Cross (JRC). During the war, American Juniors put on plays and organized bazaars to raise money for the war effort, collected scrap metal and other essential war supplies, and helped produce over 371,500,000 relief articles for US and Allied soldiers and refugees, valued at nearly $94,000,000. After the war ended, postwar leaders transformed the JRC’s mission, moving away from relief efforts and towards international education initiatives. They established pen-pal programs for between US and European schoolchildren and published monthly magazines to teach US students about the culture, geography, and histories of other nations.

(4) In 1917, the wartime leaders of the American Red Cross established an auxiliary body for US children—the Junior Red Cross (JRC). During the war, American Juniors put on plays and organized bazaars to raise money for the war effort, collected scrap metal and other essential war supplies, and helped produce over 371,500,000 relief articles for US and Allied soldiers and refugees, valued at nearly $94,000,000. After the war ended, postwar leaders transformed the JRC’s mission, moving away from relief efforts and towards international education initiatives. They established pen-pal programs for between US and European schoolchildren and published monthly magazines to teach US students about the culture, geography, and histories of other nations.

(5) As President of the United States, President Woodrow Wilson was also the President of the American Red Cross. Wilson proved to be a tireless promoter of the ARC. Through many speeches and press releases, he urged all US citizens to join the ARC, defining this as nothing less than a patriotic duty. Wilson also lent his face to ARC posters, magazine covers, and other forms of fundraising publicity. It was on 18 May 1918, perhaps, that Wilson made his commitment to the ARC most visible: on that day, he led a 70,000-person American Red Cross parade down Fifth Avenue in New York City. The visible support of Wilson and his administration played a critical role in defining the ARC as the United States’ leading humanitarian organization—a status that it continues to hold 100 years later.

Julia F. Irwin is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of South Florida. She specializes in the history of US relations with the 20th century world, with a particular focus on the role of humanitarianism in US foreign affairs. She is the author of Making the World Safe: The American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening. Her current research focuses on the history of US responses to global natural disasters.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) “Help the Red Cross.” Public domain via U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (2) “In the Name of Mercy – Give.” Albert Herter. Public domain

The post The American Red Cross in World War I appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBritain, France, and their roads from empireWho signed the death warrant for the British Empire?Spies and the burning Reichstag

Related StoriesBritain, France, and their roads from empireWho signed the death warrant for the British Empire?Spies and the burning Reichstag

March 28, 2014

Oral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nuns

This week, managing editor Troy Reeves speaks with scholar and artist Abbie Reese about her recently published book, Dedicated to God: An Oral History of Cloistered Nuns. Through an exquisite blend of oral and visual narratives, Reese shares the stories of the Poor Clare Colettine Order, a multigenerational group of cloistered contemplative nuns living in Rockford, Illinois. Among other issues, Reese’s photographs and interviews raise valuable questions about collective memory formation and community building in a space marked by anonymity and silence.

A metal grille is the literal and symbolic separation and reflection of the nuns’ vow of enclosure. The Poor Clare Colettine nuns film Abbie Reese for a collaborative ethnographic documentary. Courtesy of Abbie Reese.

In her interview with Troy, Reese talks about how popular culture sparked her interest in nuns and what it was like to work with the real women of the Poor Clare Colettine Order. Reese also discusses how she came to incorporate oral history into her work as a visual artist and her next, upcoming project.

Reese was also kind enough to share an excerpt from an interview with Sister Mary Nicolette. When sending the clip, Reese noted, “Her voice is hoarse from the interview because the nuns observe monastic silence, speaking only what is necessary to complete a task.”

You can see and hear more from the Poor Clare Colettine Order at Reese’s online exhibit Erased from the Landscape: The Hidden Lives of Cloistered Nuns.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Poor Clare Colettine nuns return to the monastery after a funeral service on the premises, in 2010, for a cloistered nun who served in WWII; Sister Ann Frances joined an active order of nuns before she transferred to the cloistered contemplative order at the Corpus Christi Monastery. Courtesy of Abbie Reese.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In keeping with the nuns' vow of enclosure and to limit the need for workers to enter the cloistered monastery, Poor Clare Colettine nuns undertake repairs and maintenance themselves, including cleaning the boiler while wearing the full habit. Coutesy of Abbie Reese.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Two nuns work in the wood shop of the Corpus Christi Monastery in Rockford, Ill. The Poor Clare Colettine nuns make vows of poverty, chastity, obedience, and enclosure. Courtesy of Abbie Reese.

Abbie Reese is an independent scholar and interdisciplinary artist who utilizes oral history and ethnographic methodologies to explore individual and cultural identity. She received an MFA in visual arts from the University of Chicago and was a fellow at the Columbia University Oral History Research Office Summer Institute. She is the author of Dedicated to God: An Oral History of Cloistered Nuns, and her multimedia exhibit, Erased from the Landscape: The Hidden Lives of Cloistered Nuns, has been shown in galleries and museums.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow the latest Oral History Review posts on the OUPblog via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nuns appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCSI: Oral History - EnclosureThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wettemann Jr. - EnclosureOral histories of Chicago youth violence - Enclosure

Related StoriesCSI: Oral History - EnclosureThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wettemann Jr. - EnclosureOral histories of Chicago youth violence - Enclosure

Entitling early modern women writers

As Women’s History Month draws to a close in the United Kingdom, it is a good moment to reflect on the history of women’s writing in Oxford’s scholarly editions. In particular, as one of the two editors responsible for early modern writers in the sprawling collections of Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO), I have been going through the edited texts of women writers included in the OSEO project, and thinking about how well even the most celebrated women writers from the period 1500 – 1700 are represented in this new digital format. In short, early modern English women writers have fared, perhaps predictably, badly.

The essayist, philosopher, and historian Francis Bacon has his place, in the Oxford Francis Bacon in fifteen volumes; but the philosopher and poet and essayist and dramatist and prose writer Margaret Cavendish, duchess of Newcastle, does not. Philip Sidney, famous for his pastoral poems, appeared in a stunningly erudite Oxford edition by William Ringler, Jr. in 1962, now like the Bacon edition a part of OSEO; Katherine Philips, also famous for her pastoral poetry, limps in to the Oxford fold in a 1905 text lightly edited by George Saintsbury, which also includes the minor Caroline poets Patrick Hannay, William Chamberlayne, and Edward Benlowes. Aphra Behn, one of the most prolific writers of the Restoration, hardly figures at all in OSEO, and the Oxford list does not include complete works for Isabella Whitney, Mary Herbert, Amelia Lanyer, or Mary Wroth.

Among those lyric poems and short works by women that are included in OSEO, many return to the silencing of a woman’s voice, the disabling of her love, and the banishment of her person. Typical is Mary Wroth’s “83 Song”, first published in Peter Davidson’s anthology, Poetry and Revolution: An Anthology of British and Irish Verse 1625-1660. Recognising that “the time is come to part” with her “deare”, the woman speaker of the poem gives up not only her own happiness, but his unhappiness. She goes to “woe”, while he goes to “more joy”:

Where still of mirth injoy thy fill,

One is enough to suffer ill:

My heart so well to sorrow us’d,

Can better be by new griefes bruis’d. (ll. 5-8)

The woman lover’s habituation to grief gives her a capacity for further bruising that, not without irony, she embraces as an ethical duty. Hers is a voice constructed for loss and for complaint, so much so that she cannot escape from this loss, and the woes that “charme” her, except by death – as the concluding stanza of the song suggests:

And yett when they their witchcrafts trye,

They only make me wish to dye:

But ere my faith in love they change,

In horrid darknesse will I range. (ll. 17-20)

For Wroth’s loving, jilted woman speaker, identity is constructed out of a wronged fidelity; the two options remaining to her are complaint and oblivion.

Complaint was still a powerful mode for women writers during the Restoration – certainly a mode that modern editors have much privileged in anthologies. A poem by Aphra Behn, “A Paraphrase on Oenone to Paris”, has slipped in to OSEO‘s corpus through its inclusion in John Kerrigan’s wonderful anthology, Motives of Woe: Shakespeare and ‘Female Complaint’: A Critical Anthology.

In this poem the shepherdess Oenone challenges the Trojan prince Paris, who had won her love while keeping flocks on the slopes of Mount Ida; afterward discovering his true birthright, Paris has abandoned her, and sails for Sparta, there to ravish Menelaus’ queen, Helen, and set in train the events that will lead to the Trojan War. Toward the end of Behn’s long poem of complaint, Oenone reprehends her lover for his faithlessness with an argument that seems to gesture at Behn’s own public reputation:

How much more happy are we Rural Maids,

Who know no other Palaces than Shades?

Who want no Titles to enslave the Croud,

Least they shou’d babble all our Crimes aloud;

No Arts our good to show, our Ills to hide,

Nor know to cover faults of Love with Pride.

I lov’d, and all Loves Dictates did persue,

And never thought it cou’d be Sin with you.

To Gods, and Men, I did my Love proclaim

For one soft hour with thee, my charming Swain,

Wou’d Recompence an Age to come of Shame,

Cou’d it as well but satisfie my Fame.

But oh! those tender hours are fled and lost,

And I no more of Fame, or Thee can boast!

‘Twas thou wert Honour, Glory, all to me:

Till Swains had learn’d the Vice of Perjury,

No yielding Maids were charg’d with Infamy.

‘Tis false and broken Vows make Love a Sin,

Hadst thou been true, We innocent had been. (ll. 265-83)

The “Titles” that Oenone disclaims are those of honour, the courtly ranks and degrees to which women might be raised by their paternity, or by their advantageous marriages; wanting titles, shepherdesses can sport in the shades of innocence, their sexual crimes unremarked and undisplayed. The shame and infamy that now await Oenone spring directly from Paris’ perjury, for the woman’s reputation for immodesty flows from the exposure accomplished by her jilting. To her way of thinking, a crime is no crime until it is published; this is a logic she has learned from men, who cover up their own crimes with “Pride”. But “Titles” may also be those of published books, and the “Arts” Oenone lacks may be just those powers of “Pride” that always enable men to abandon women – in a broad sense, the power to speak falsely. What women do, cries Behn’s Oenone, has been betrayed by what men say; what can a woman write, that will not collude in her own untitling?

Early modern women writers have not been much or widely published. There are many reasons, of course, for this history of omission and scant commission. But so long as we continue to anthologize selections from the works of women writers from this period, and to bundle them in mixed fardels, we collude in a history or pattern of dis-titling, of allowing early modern women poets to complain, but not to speak in their more diverse collected works. This pattern is changing: important new editions of Wroth and Behn have appeared in the last few decades, and – closer to home – the works of the translator and poet Lucy Hutchinson, in a meticulously edited text from David Norbrook and Reid Barbour, have recently joined the Oxford list and the OSEO fold. Other early modern women writers will surely follow. As Women’s History Month comes to an end, it’s high time we put a period to infamy, shame, oblivion, and bruising.

Andrew Zurcher is a Fellow and Director of Studies in English at Queens’ College, Cambridge, and a member of the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) editorial board.

Scholarly editions are the cornerstones of humanities scholarship, and Oxford University Press’s list is unparalleled in breadth and quality. Now available online, Oxford Scholarly Editions Online provides an interlinked collection of these authoritative editions. Discover more by taking a tour of the site.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Aphra Behn by Mary Beale. Image available on public domain via WikiCommons

The post Entitling early modern women writers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesI’m dreaming of an OSEO ChristmasIs our language too masculine?Ovid the naturalist

Related StoriesI’m dreaming of an OSEO ChristmasIs our language too masculine?Ovid the naturalist

The never-ending assault by microbes

It is almost impossible to read a daily newspaper or listen to news reports from television and radio without hearing about an outbreak of an infectious disease. On 13 March 2014, the New York City Department of Health investigated a measles outbreak. Sixteen cases including nine pediatric cases were detected, probably caused by a failure to vaccinate the victims. On 12 February, an outbreak of a common microbial pathogen known as C.difficile occurred in several hospitals in Great Britain. This pathogen induces severe cases of gastrointestinal distress including diarrhea, fever, and stomach cramps. One of the main problems with a number of microbial pathogens like C.difficile is that they have become completely resistant to many known drugs.

How did this occur? Antibiotics, complex substances produced by certain types of microbes that destroy other microbes, were hailed as miracle drugs when the first one (penicillin) was discovered more than 70 years ago by Alexander Flemming. Although over 70 useful antibiotics have been discovered since penicillin, many can no longer be used because microbial pathogens have become resistant to them through evolution. In fact, over two million people in the United States become infected with antibiotic resistant pathogens every year, leading to 23,000 deaths according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). New non-antibiotic drugs are always being sought to treat infectious diseases (mostly microbial because viral diseases are not susceptible to antibiotics). One such new discovery is a commonly used pain medication called Carprofen which inhibits antibiotic resistant pathogens. Thus, the “war against” infectious diseases remains an ongoing focus of medical research.

Of course there are many other pathogens (both microbial and viral) besides those mentioned above that assault us and our body defenses constantly. They include pneumonia, dysentery, tuberculosis, tetanus, diphtheria, scarlet fever, ulcers, typhoid, meningitis, plague, cholera (bacterial), polio, HIV (AIDS), rabies, influenza, measles, mumps, the common cold, yellow fever, and chicken pox (viral). Nevertheless, all of us are not equally “susceptible” to each infectious disease — a poorly understood term that determines why some of us get one disease but not another, or why some diseases occur in the winter while others occur in the summer.

This brings us to an important concept, namely, that there is no way to be free of microbes that inhabit every “nook and cranny” of our bodies. Of the approximately ten million cells that make up the human body, there are billions of microbes that come along with them. Most microbes that inhabit our bodies are necessary for our existence. Together they make up what is called the “microbiome” consisting of a diverse group of microbes that help keep each of us healthy. Most of them are found in the gastrointestinal tract where they aid digestion; synthesize vitamins and other necessary biochemicals our cells cannot make; attack and destroy pathogens; and stimulate our immune system to act in the same way.

Nevertheless, with this constant assault, one might wonder how it is possible we have survived for so long. There are a number of other variables besides the “microbiome’ that are responsible and that are still poorly understood. These include an ability of a host (us) to coexist with a pathogen (we keep them at bay or limit their spread internally like tuberculosis), an ability to mount a furious immunological attack on the pathogen to destroy them, or an innate ability to remain “healthy” (a vague term that really signifies the fact that all of our metabolic systems are operating optimally most of the time like digestion, excretion, blood circulation, neurological or brain function, and healthy gums and teeth among other systems).

Where does this innate ability come from? Simply put, genetic phenomena (both in microbes and in humans). These traits are not only inherited under the control of genes but their functions are also controlled by such genes. Different pathogens have different sets of genes which act to produce a specific disease in a susceptible host. However, it is also why individual hosts (humans) are more or less resistant to such infectious diseases.

How does the body interact with these “foreign” entities? The immune system must protect the body from attack by pathogens and also from the formation of abnormal cells which could turn cancerous. Two types of immune responses exist. One is under the control of antibodies (proteins which circulate in the blood stream) that resist and inactivate invading pathogens by binding to them. The other is mediated by a certain type of white blood cell called a lymphocyte that destroys abnormal (potentially cancerous) cells and viral infected cells. Together, with other white blood cells, they present a formidable defense against infection and abnormality.

It takes time for an immune response by antibodies to develop during a pathogenic invasion because there are many components involved in the activity. They are usually divided into primary and secondary responses. The primary response represents the first contact with the antigen which after a period of time results in an increased production of specific antibodies that react only to that antigen (which by the way are also produced by certain lymphocytes called “B” or plasma cells). Once the infection is controlled, antibody levels fall considerably. If, however, another infection occurs in the future by the same pathogen, a much more vigorous response will result (called the secondary response) producing a much faster development and a higher level of antibodies. Why is the secondary response so much faster and vigorous? This phenomenon is due to a remarkable property of the immune system in which the primary response is “remembered” after its decrease by the preservation of “memory” “B” lymphocytes that circulate until the secondary response occurs, no matter how long it takes.

William Firshein is the Daniel Ayers Professor of Biology, Emeritus and author of The Infectious Microbe. He chaired the Biology Department at Wesleyan University for six years and published over 75 original research papers in the field of Molecular Microbiology of Pathogens. He was the recipient of several million dollars of grant support from various public and private research agencies and taught over 6,000 graduate and undergraduate students during his 48 year career.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The never-ending assault by microbes appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOne billion dogs? What does that mean?Will caloric restriction help you live longer?Unlearned lessons from the McMartin Preschool case

Related StoriesOne billion dogs? What does that mean?Will caloric restriction help you live longer?Unlearned lessons from the McMartin Preschool case

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers