Oxford University Press's Blog, page 836

March 11, 2014

Female artists and politics in the civil rights movement

In the battle for equal rights, many Americans who supported the civil rights movement did not march or publicly protest. They instead engaged with the debates of the day through art and culture. Ruth Feldstein, author of How it Feels to Be Free: Black Women Entertainers and the Civil Rights Movement, joined us in our New York offices to discuss the ways in which culture became a battleground and to share the stories of the female performers who played important but sometimes subtle roles in the civil rights movement.

Ruth Feldstein on the ways artists used their art to advance the civil rights movement:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Ruth Feldstein on Lena Horne’s legacy:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Nina Simone as an activist:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Ruth Feldstein is Associate Professor of History at Rutgers University, Newark. She is the author of How it Feels to Be Free: Black Women Entertainers and the Civil Rights Movement and Motherhood in Black and White: Race and Sex in American Liberalism, 1930-1965.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Female artists and politics in the civil rights movement appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhen art coaxed the soul of America back to lifeDeclaration of independenceSounds of justice: black female entertainers of the Civil Rights era

Related StoriesWhen art coaxed the soul of America back to lifeDeclaration of independenceSounds of justice: black female entertainers of the Civil Rights era

March 10, 2014

Changes in the DSM-5: what social workers need to know

Social workers that provide therapeutic and other services to children and adolescents can expect to find some major changes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition: in their placement within the DSM-5, the conceptualization of the disorders, the criteria for the disorders, the elimination of disorders, and the inclusion of some new diagnoses.

Where to find diagnoses: The separate chapter on disorders usually found in childhood and adolescents (that was in the DSM IV) no longer exists. Instead, the DSM-5 provides a life span development approach to diagnosis meaning that disorders for children and adolescents are scattered throughout the manual. Chapters and groupings of mental disorders have also been organized differently. The diagnosis of ADHD, for example, has been moved to the new chapter, Neurodevelopmental Disorders and has added symptom criteria for ages 17 and older. In the same chapter you will also find specific learning disorders, Autism Spectrum Disorder, motor disorders, Tourette disorder, and Intellectual Disability (Intellectual Developmental Disorder), which replaces the term ‘mental retardation’ that was in the DSM IV. The diagnosis for Reactive Attachment Disorder now exists within a new chapter on Trauma and Stress Related Disorders. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder is further covered in this chapter (instead of the Anxiety Disorders chapter as it was in DSM IV) and has new criteria for children under the age of six.

Changes in criteria: Symptoms and specifiers have changed for several disorders. Criteria for Intellectual Disability, for example, has changed to dis-include the establishing of severity levels through cutting points that were shown for IQ test scores — emphasizing instead that considerable clinical judgment is needed in interpreting those tests and in accurately making the diagnosis. In order to determine the levels of severity (mild, moderate, severe, and profound) that are associated with Intellectual Development Disorder, practitioners are directed to assess a client’s functioning across conceptual, social, and practical domains of functioning. The childhood diagnosis of Conduct Disorder (now found in the Disruptive, Impulse Control and Conduct Disorders chapter) has added the specifier “with limited prosocial emotions”: to demonstrate lack of empathy, guilt, and shallow affect that may show considerable aggression, thrill seeking, and callous behavior.

New diagnoses: Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder is perhaps one of the most debated disorders that was added to the DSM-5 and was included to try and decrease the numbers of children and adolescents being diagnosed with Bi-polar disorders. It was also a goal of the DSM-5 task force to reduce the numbers of children and adolescents that were being prescribed psychotropic medications. Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder is found in the chapter on Depressive Disorders — while criteria for the Bi-polar I & II disorders are now in a different chapter on Bi-polar and Related Disorders. The core symptoms of Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder is the chronic and persistent irritability that is severe accompanied with temper outbursts that occur 2-3 times a week across different settings. Another disorder that was added to the DSM-5 is the Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder that describes children who are overly friendly and familiar with strangers. The criteria for this disorder describes a lack of reticence to go with strangers, a lack of social boundaries, and decreased checking in with adults. This new disorder is seen in children and adolescents that have experienced difficult upbringing and that do not have their basic needs met from caretakers.

Elimination of disorders: Removed diagnoses that apply to children include: (1) Feeding Disorder of infancy and early childhood, (2) Rett’s Disorder, (3) Learning Disorder NOS, (4) Childhood Disintegrative Disorder, (5) Asperger’s Disorder, and (6) Pervasive Developmental Disorder NOS. The removal of Asperger’s syndrome was the most controversial. Now children and adolescents receiving this diagnosis are diagnosed along the mild dimension of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Or they may be diagnosed with Social Communication Disorder if a person does not meet the specific criteria for impairments in restrictive and repetitive behavior patterns that are associated with the Autism Spectrum Disorders diagnosis.

How disorders are reported: The DSM-5 does not use the Axis 1-5 structure that was used in the DSM IV for recording diagnoses, but instead encourages a case conceptualization approach that allows practitioners to record multiple mental disorder diagnoses. A primary diagnosis may be indicated, and health conditions may also be included. Conditions that are not mental disorders per se but may be a focus of clinical attention, that were taken from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-Clinical Modification) and the ICD-10, may also be diagnosed. Child maltreatment or neglect problems, economic problems, education problems, and problems related to social environment are examples of diagnosable clinical condition categories. The Global Assessment of Functioning scale that was a part on Axis V of the DSM IV has further been replaced by several cross cutting measures that may be used as screening and assessment tools.

While adapting to the new DSM-5 may be a challenge for many social workers, it is an opportunity to provide clients with a more nuanced approach to their situation – emphasizing more cultural, social, and developmental issues that may be associated with mental disorders. The diagnosis of clinical conditions that are not mental disorders, but are often a focus of clinical attention, also provides social workers with an opportunity to more thoroughly explain the cultural, social, and family circumstances of clients.

Cynthia Franklin, PhD, LCSW is the Stiernberg/Spencer Family Professor in Mental Health and Assistant Dean for Doctoral Education in School of Social Work at the University of Texas at Austin. She is Editor in Chief of the Encyclopedia of Social Work Online.

Learn more about the DSM-5 changes and new developments in social work with the Encyclopedia of Social Work Online, the first continuously updated online collaboration between the National Association of Social Workers (NASW Press) and Oxford University Press (OUP). Building off the classic reference work, a valuable tool for social workers for over 85 years, the online resource of the same name offers the reliability of print with the accessibility of a digital platform. Over 400 overview articles, on key topics ranging from international issues to ethical standards, offer students, scholars, and practitioners a trusted foundation for a lifetime of work and research, with new articles and revisions to existing articles added regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social work articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post Changes in the DSM-5: what social workers need to know appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMad politicsWhen art coaxed the soul of America back to lifeThe rise of music therapy

Related StoriesMad politicsWhen art coaxed the soul of America back to lifeThe rise of music therapy

When art coaxed the soul of America back to life

Writing in the New York Times recently, art critic Holland Cotter lamented the fact that the current billionaire-dominated market system, “is shaping every aspect of art in the city; not just how artists live, but also what kind of art is made, and how art is presented in the media and in museums.” “Why,” he asks, “in one of the most ethnically diverse cities, does the art world continue to be a bastion of whiteness? Why are African-American curators and administrators, and especially directors, all but absent from our big museums? Why are there still so few black — and Latino, and Asian-American — critics and editors?”

It wasn’t always like this. During the 1930s under the New Deal, the arts were democratized, made accessible to ordinary people who lacked the means to buy paintings worth hundreds of thousands of dollars or to attend Broadway shows at over $100 a ticket. The New Deal’s support for the arts is one of the most interesting and unique episodes in the history of American public policy.

The federal arts programs initiated in the 1930s were intended to alleviate the economic hardships of unemployed cultural workers, to popularize art among a much wider segment of the population, and to boost public morale during a time of deep stress and pessimism, or as New Deal artist Gutzon Borglum remarked, to “coax the soul of America back to life.”

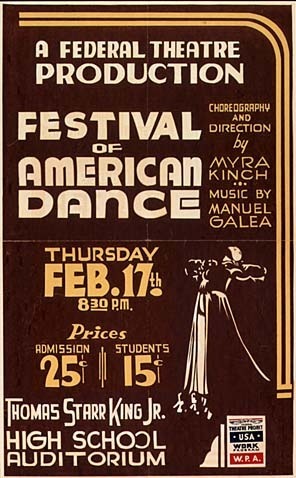

WPA Federal Art Project Poster, 1936. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The best known of all the programs that were enacted during the Depression was the WPA (Works Progress Administration) Art Project. It consisted of four distinct projects: a Federal Art Project, a Federal Writers’ Project, a Federal Theatre Project, and a Federal Music Project.

Paintings were given to government offices, while murals, sculptures, bas relief, and mosaics were seen on the walls of schools, libraries, post offices, hospitals, courthouses, and other public buildings. Over the course of its eight years, the WPA commissioned over five hundred murals for New York City’s public hospitals alone. Among the now well-known artists supported by these programs were painters such as Thomas Hart Benton, Jackson Pollack, Willem de Kooning, Raphael and Moses Soyer, and the sculptor, Louise Nevelson.

The print workshops set up by the WPA prepared the ground for the flowering of the graphic arts in the United States, which until that time had been limited in both media and expression. Moreover, since prints were portable and cheap, they became a vehicle for broadening the public’s understanding and appreciation of the creative arts.

Some 100 community art centers, which included galleries, classrooms, and community workshops, were established in twenty-two states–but particularly where opportunities to experience and make art were scarce. Through this effort individuals who may never have seen a large painted scene or a piece of sculpture were given the opportunity to experience not only a finished work of art but to participate in the creative process. In the New York City area alone, an estimated 50,000 people participated in classes under the Federal Art Project auspices each week. According to Smithsonian author, David A. Taylor, “the effect was electric. It jump-started people beginning careers in art amid the devastation.”

The Federal Writers’ project provided employment and experience for editors, art critics, researchers, and historians, a number of whom later became famous for their novels and poetry, such as Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Studs Terkel, and Saul Bellow. They were put to work writing state and regional guidebooks that were to portray the social, economic, industrial, and historical background of the country. These guidebooks represented a vast treasury of Americana from the ground up, including facts and folklore, history and legend, and histories of the famous, the infamous, and the excluded. There were also seventeen-volumes of oral histories of the last people who had lived under slavery. An additional set of folklore and oral histories of 10,000 people from all regions, occupations, and ethnic groups were collected and are now held in the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress.

Federal Theater Project poster, 1938. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Federal Theatre Project was the first and only attempt to create a national theatre in the United States, producing all genres of theater, including classical plays, circuses, puppet shows, musical comedies, vaudeville, dance performances, children’s theatre, and experimental plays. They were performed wherever people could gather—not only in theaters, but in parks, hospitals, convents, churches, schools, armories, circus tents, universities, and prisons. Touring companies brought theater to parts of the country where drama had been non-existent, and provided training and experience for thousands of aspiring actors, directors, stagehands, and playwrights, among them, Orson Wells, Eugene O’Neill, and Joseph Houseman.

The program emphasized preserving and promoting minority cultural forms. At a time of strict racial segregation with arts funding non-existent in African American communities, black theatre companies were established in many cities. Foreign language companies performed works in French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Yiddish.

The Federal Theatre Project also brought controversial issues to the foreground, making it one of the most embattled of all the New Deal programs. Its “Living Newspaper” section produced plays about labor disputes, economic inequality, racism, and similar issues, which infuriated a growing chorus of conservative critics who succeeded in eliminating the program in 1939.

The Federal Music Project employed 15,000 instrumentalists, composers, vocalists, and teachers as well as providing financial assistance for existing orchestras and creating new ones in places that had never had an orchestra. Many other musical forms—opera, band concerts, choral music, jazz, and pop–were also performed. Most of the concerts were either free to the public or offered at very low cost, and free music classes were open to people of all ages and abilities.

In addition to the arts programs, the Farm Security Administration’s photography program oversaw the production of more than 80,000 photographs, as part of the effort to make the nation aware of the plight of displaced rural populations. These images–produced by photographers such as Walker Evans, Gordon Parks, and Dorothea Lange helped humanize the verbal and statistical reports of the terrible poverty and turmoil in the agricultural sector of the economy and brought documentary photography into the cultural pantheon of the nation.

Between 1933 and 1942 ten thousand artists produced some 100,000 easel paintings, 18,000 sculptures, over 13,000 prints, 4,000 murals, over 1.6 million posters, and thousands of photographs. Over a thousand towns and cities now boasted federal buildings embellished with New Deal murals and sculpture. Some 6,686 writers produced more than a thousand books and pamphlets, and the Federal Theatre Project thousands of plays. More than the quantity of the output, however, is the way in which these programs shaped Americans’ understanding of who they were as a people and their country’s possibilities. Before the New Deal, the notion that government should support the arts was unheard of, but thanks to the New Deal, art had been democratized and, for a time, de-commodified, made accessible to the great majority of the American people.

Perhaps Roosevelt himself best summed up the significance of the New Deal arts programs:

A few generations ago, the people of this country were often taught . . . to believe that art was something foreign to America and to themselves . . . But . . . within the last few years . . . they have discovered that they have a part. . . . They have seen in their own towns, in their own villages, in schoolhouses, in post offices, in the back rooms of shops and stores, pictures painted by their sons, their neighbors—people they have known and lived beside and talked to. . . some of it good, some of it not so good, but all of it native, human, eager, and alive–all of it painted by their own kind in their own country, and painted about things that they know and look at often and have touched and loved. The people of this country know now . . . that art is not something just to be owned but something to be made: that it is the act of making and not the act of owning that is art. And knowing this they know also that art is not a treasure in the past or an importation from another land, but part of the present life of all the living and creating peoples—all who make and build; and, most of all, the young and vigorous peoples who have made and built our present wide country.

New Deal support for the arts had coaxed the soul of America back to life, but we are in danger of losing it again. Under the obsession with deficits, arts programs in the public schools are being cut, federal funding for the arts has dropped dramatically, and even private funding has been reduced. Without art, we are ill-equipped as a people with the collective imagination that is needed if we are to resolve the enormous challenges that confront us in the twenty-first century. Who or what will there be to coax this generation back to life?

Sheila D. Collins is Professor of Political Science Emerita, William Paterson University and editor/author with Gertrude Schaffner Goldberg of When Government Helped: Learning from the Successes and Failures of the New Deal. She serves on the speakers’ bureau of the National New Deal Preservation Association, the Research Board of the Living New Deal and the board of the National Jobs for All Coalition, is a member of the Global Ecological Integrity Group and co-chairs two seminars at Columbia University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post When art coaxed the soul of America back to life appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDeclaration of independenceHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?What Kerry and Obama could learn from FDR on the environment

Related StoriesDeclaration of independenceHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?What Kerry and Obama could learn from FDR on the environment

Sovereignty disputes in the South and East China Sea

Tensions in the South and East China Seas are high and likely to keep on rising for some time, driven by two powerful factors: power (in the form of sovereignty over and influence in the region) and money (from the rich mineral deposits that lurk beneath the disputed waters). Incidents, such as the outcry over China’s recently announced Air Defence Identification Zone, have come thick and fast the last few years. One country’s historic right is another country’s attempt at annexation. Every new episode in turn prompts a wave of scholarly soul-searching as to the lawfulness of actions taken by the different countries and the ways that international law can, or cannot, help resolve the conflicts.

Maritime claims in the South China Sea by Goran tek-en. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

In order to help keep track of debate in blogs, journals, and newspapers on the international law aspects of the various disputes, we have created a debate map which indexes who has said what and when. It follows on from our previous maps on the use of force against Syria and the prosecution of heads of state and other high-profile individuals at the International Criminal Court. Blog posts in particular have a tendency to disappear off the page once they are a few days old, which often means that their contribution to the debate is lost. The debate maps reflect a belief that these transient pieces of analysis and commentary deserve to be remembered, both as a reflection of the zeitgeist and as important scholarly contributions in their own right.

To help readers make up their own minds about the disputes, the map also includes links to primary documents, such as the official positions of the countries involved and their submissions to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.

One striking aspect of the map is how old some of the articles are, originating from the early 1970s. Controversies which seem new now actually go back some 40 years. In conflicts such as these, which cannot be understood without their history and where grievances often go back centuries, this awareness is key.

Another surprising feature is the uncertainty surrounding the legal basis of China’s claim to sovereignty over most of the South China Sea—its famous nine-dash line. Semi-official or unofficial statements by Chinese civil servants, or in one case by the Chinese Judge at the International Court of Justice, are seized on as indications of what China’s justifications are for its expansive maritime claims. A clearer official position, and more input from Chinese scholars, would significantly improve the debate.

Ultimately, the overlapping maritime claims and sovereignty disputes in the South and East China Seas are unlikely to be solved any time soon, and will keep commentators busy for years to come. We will keep the map up to date to facilitate and archive the debate. Your help is indispensable: please get in touch if you have any suggestions for improvements or for new blog posts and articles we can link to.

Merel Alstein is a Commissioning Editor for international law titles at Oxford University Press. She recently compiled a debate map on disputes in the South and East China Seas. Follow her on Twitter @merelalstein.

Oxford Public International Law is a comprehensive, single location providing integrated access across all of Oxford’s international law services. Oxford Reports on International Law, the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, and Oxford Scholarly Authorities on International Law are ground-breaking online resources working to speed up research and provide easy access to authoritative content, essential for anyone working in international law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Sovereignty disputes in the South and East China Sea appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTransparency in investor-state arbitrationWhole life imprisonment reconsideredThe case law of the ICJ in investment arbitration

Related StoriesTransparency in investor-state arbitrationWhole life imprisonment reconsideredThe case law of the ICJ in investment arbitration

Declaration of independence

Finishing a book is a burden lifted accompanied by a sense of loss. At least it is for some. Academic authors, stalked by the REF in Britain and assorted performance metrics in the United States, have little time these days for either emotion. For emeriti, however, there is still a moment for reflecting upon the newly completed work in context—what were it origins, what might it contribute, how does it fit in? The answer to this last query for an historian of colonial America with a collateral interest in Britain of the same period is “oddly.” Somehow the renascence of interest in the British Empire has managed to coincide with a decline in commitment in the American academy to the history of Great Britain itself. The paradox is more apparent than real, but dissolving it simply uncovers further paradoxes nested within each other like so many homunculi.

Begin with the obvious. If Britain is no longer the jumping off point for American history, then at least its Empire retains a residual interest thanks to a supra-national framework, (mostly inadvertent) multiculturalism, and numerous instances of (white) men behaving badly. The Imperial tail can wag the metropolitan dog. But why this loss of centrality in the first place? The answer is also supposed to be obvious. Dramatic changes, actual and projected, in the racial composition of late twentieth and early twenty-first century America require that greater attention be paid to the pasts of non-European cultures. Members of such cultures have in fact been in North America all along, particularly the indigenous populations of North America at the time of European colonization and the African populations transported there to do the heavy work of “settlement.” Both are underrepresented in the traditional narratives. There are glaring imbalances to be redressed and old debts to be settled retroactively. More Africa, therefore, more “indigeneity,” less “East Coast history,” less things British or European generally.

The British Colonies in North America 1763 to 1776

The all but official explanation has its merits, but as it now stands it has no good account of how exactly the respective changes in public consciousness and academic specialization are correlated. Mexico and people of Mexican origin, for example, certainly enjoy a heightened salience in the United States, but it rarely gets beyond what in the nineteenth century would have been called The Mexican Question (illegal immigration, drug wars, bilingualism). Far more people in America can identify David Cameron or Tony Blair than Enrique Peña Nieto or even Vincente Fox. As for the heroic period of modern Mexican history, its Revolution, it was far better known in the youth of the author of this blog (born 1942), when it was still within living memory, than it is at present. That conception was partial and romantic, just as the popular notion of the American Revolution was and is, but at least there was then a misconception to correct and an existing interest to build upon.

One could make very similar points about the lack of any great efflorescence in the study of the Indian Subcontinent or the stagnation of interest in Southeast Asia after the end of the Vietnam War despite the increasing visibility of individuals from both regions in contemporary America. Perhaps the greatest incongruity of all, however, is the state of historiography for the period when British and American history come closest to overlapping. In the public mind Gloriana still reigns: the exhibitions, fixed and traveling, on the four hundredth anniversary of the death of Elizabeth I drew large audiences, and Henry VIII (unlike Richard III or Macbeth) is one play of Shakespeare’s that will not be staged with a contemporary America setting. The colonies of early modern Britain are another matter. In recent years whole issues of the leading journal in the field of early American history have appeared without any articles that focus on the British mainland colonies, and one number on a transnational theme carries no article on either the mainland or a British colony other than Canada in the nineteenth century. Although no one cares to admit it, there is a growing cacophony in early American historiography over what is comprehended by early and American and, for that matter, history. The present dispensation (or lack thereof) in such areas as American Indian history and the history of slavery has seen real and on more than one occasion remarkable gains. These have come, however, at a cost. Early Americanists no longer have a coherent sense of what they should be talking about or—a matter of equal or greater significance–whom they should be addressing.

Historians need not be the purveyors of usable pasts to customers preoccupied with very narrow slices of the present. But for reasons of principle and prudence alike they are in no position to entirely ignore the predilections and preconceptions of educated publics who are not quite so educated as they would like them to be. In the world’s most perfect university an increase in interest in, say, Latin America would not have to be accompanied by a decrease in the study of European countries except in so far as they once possessed an India or a Haiti. In the current reality of rationed resources this ideal has to be tempered with a dose of “either/or,” considered compromises in which some portion of the past the general public holds dear gives way to what is not so well explored as it needs to be. Instead, there seems instead to be an implicit, unexamined indifference to an existing public that knows something, is eager to know more, and, therefore, can learn to know better. Should this situation continue, outside an ever more introverted Academy the variegated publics of the future may well have no past at all.

Stephen Foster is Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus (History), Northern Illinois University. His most recent publication is the edited volume British North America in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The British Colonies 1763 to 1776. By William R. Shepherd, 1923. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Declaration of independence appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBeyond Ed Sullivan: The Beatles on American televisionHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?Minority women chemists yesterday and today

Related StoriesBeyond Ed Sullivan: The Beatles on American televisionHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?Minority women chemists yesterday and today

March 9, 2014

Jane Austen and the art of letter writing

No, the image to the left is not a newly discovered picture of Jane Austen. The image was taken from my copy of The Complete Letter Writer, published in 1840, well after Jane Austen’s death in 1817. But letter writing manuals were popular throughout Jane Austen’s lifetime, and the text of my copy is very similar to that of much earlier editions of the book, published from the mid-1750s on. It is possible then that Jane Austen might have had access to one. Letter writing manuals contained “familiar letters on the most common occasions in life”, and showed examples of what a letter might look like to people who needed to learn the art of letter writing. The Complete Letter Writer also contains an English grammar, with rules of spelling, a list of punctuation marks and an account of the eight parts of speech. If Jane Austen had possessed a copy, she might have had access to this feature as well.

No, the image to the left is not a newly discovered picture of Jane Austen. The image was taken from my copy of The Complete Letter Writer, published in 1840, well after Jane Austen’s death in 1817. But letter writing manuals were popular throughout Jane Austen’s lifetime, and the text of my copy is very similar to that of much earlier editions of the book, published from the mid-1750s on. It is possible then that Jane Austen might have had access to one. Letter writing manuals contained “familiar letters on the most common occasions in life”, and showed examples of what a letter might look like to people who needed to learn the art of letter writing. The Complete Letter Writer also contains an English grammar, with rules of spelling, a list of punctuation marks and an account of the eight parts of speech. If Jane Austen had possessed a copy, she might have had access to this feature as well.

But I doubt if she did. Her father owned an extensive library, and Austen was an avid reader. But in genteel families such as hers letter writing skills were usually handed down within the family. “I have now attained the true art of letter-writing, which we are always told, is to express on paper what one would say to the same person by word of mouth,” Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra on 3 January 1801, adding, “I have been talking to you almost as fast as I could the whole of this letter.” But I don’t think George Austen’s library contained any English grammars either. He did teach boys at home, to prepare them for further education, but he taught them Latin, not English.

So Jane Austen didn’t learn to write from a book; she learnt to write just by practicing, from a very early age on. Her Juvenilia, a fascinating collection of stories and tales she wrote from around the age of twelve onward, have survived, in her own hand, as evidence of how she developed into an author. Her letters, too, illustrate this. She is believed to have written some 3,000 letters, only about 160 of which have survived, most of them addressed to Cassandra. The first letter that has come down to us reads a little awkwardly: it has no opening formula, contains flat adverbs – “We were so terrible good as to take James in our carriage”, which she would later employ to characterize her so-called “vulgar” characters – and even has an unusual conclusion: “yours ever J.A.”. Could this have been her first letter?

Cassandra wasn’t the only one she corresponded with. There are letters to her brothers, to friends, to her nieces and nephews as well as to her publishers and some of her literary admirers, with whom she slowly developed a slightly more intimate relationship. There is even a letter to Charles Haden, the handsome apothecary who she is believed to have been in love with. Her unusual ending, “Good bye”, suggests a kind of flirting on paper. The language of the letters shows how she varied her style depending on who she was writing to. She would use the word fun, considered a “low” word at the time, only to the younger generation of Austens. Jane Austen loved linguistic jokes, as shown by the reverse letter to her niece Cassandra Esten: “Ym raed Yssac, I hsiw uoy a yppah wen raey”, and she recorded her little nephew George’s inability to pronounce his own name: “I flatter myself that itty Dordy will not forget me at least under a week”.

It’s easy to see how the letters are a linguistic goldmine. They show us how she loved to talk to relatives and friends and how much she missed her sister when they were apart. They show us how she, like most people in those days, depended on the post for news about friends and family, how a new day wasn’t complete without the arrival of a letter. At a linguistic level, the letters show us a careful speller, even if she had different spelling preferences from what was general practice at the time, and someone who was able to adapt her language, word use and grammar alike, to the addressee.

All her writing, letters as well as her fiction, was done at a writing desk, just like the one on the table on the image from the Complete Letter Writer, and just like my own. A present from her father on her nineteenth birthday, the desk, along with the letters written upon it, is on display as one of the “Treasures of the British Library”. The portable desk traveled with her wherever she went. “It was discovered that my writing and dressing boxes had been by accident put into a chaise which was just packing off as we came in,” she wrote on 24 October 1798. A near disaster, for “in my writing-box was all my worldly wealth, 7l”.

Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade has a chair in English Sociohistorical Linguistics at the University of Leiden Centre for Linguistics (Leiden, The Netherlands). Her most recent books include In Search of Jane Austen: The Language of the Letters, The Bishop’s Grammar: Robert Lowth and the Rise of Prescriptivism, and An Introduction to Late Modern English. She is currently the director of the research project “Bridging the Unbridgeable: Linguists, Prescriptivists and the General Public”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Image of Jane Austen from The Complete Letter Writer, public domain via Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2) Photo of writing desk, Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade.

The post Jane Austen and the art of letter writing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow the Humanities changed the worldThe great Oxford World’s Classics debateWhat does he mean by ‘I love you?’

Related StoriesHow the Humanities changed the worldThe great Oxford World’s Classics debateWhat does he mean by ‘I love you?’

How do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?

For 20 years, 14 of those in England, I’ve been giving lectures about the social power afforded to dictionaries, exhorting my students to discard the belief that dictionaries are infallible authorities. The students laugh at my stories about nuns who told me that ain’t couldn’t be a word because it wasn’t in the (school) dictionary and about people who talk about the Dictionary in the same way that they talk about the Bible. But after a while I realized that nearly all the examples in the lecture were, like me, American. At first, I could use the excuse that I’d not been in the UK long enough to encounter good examples of dictionary jingoism. But British examples did not present themselves over the next decade, while American ones kept streaming in. Rather than laughing with recognition, were my students simply laughing with amusement at my ridiculous teachers? Is the notion of dictionary-as-Bible less compelling in a culture where only about 17% of the population consider religion to be important to their lives? (Compare the United States, where 3 in 10 people believe that the Bible provides literal truth.) I’ve started to wonder: how different are British and American attitudes toward dictionaries, and to what extent can those differences be attributed to the two nations’ relationships with the written word?

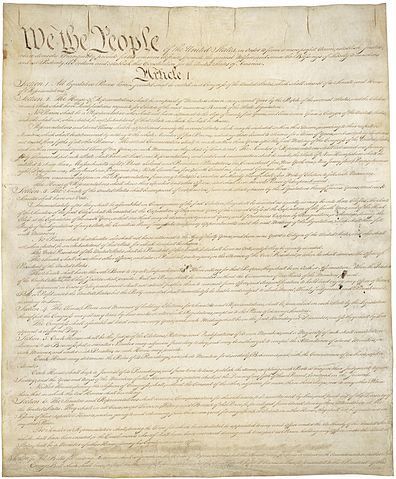

Constitution of the United States of America. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Our constitutions are a case in point. The United States Constitution is a written document that is extremely difficult to change; the most recent amendment took 202 years to ratify. We didn’t inherit this from the British, whose constitution is uncodified — it’s an aggregation of acts, treaties, and tradition. If you want to freak an American out, tell them that you live in a country where ‘[n]o Act of Parliament can be unconstitutional, for the law of the land knows not the word or the idea’. Americans are generally satisfied that their constitution — which is just about seven times longer than this blog post — is as relevant today as it was when first drafted and last amended. We like it so much that a holiday to celebrate it was instituted in 2004.

Dictionaries and the law

But with such importance placed on the written word of law comes the problem of how to interpret those words. And for a culture where the best word is the written word, a written authority on how to interpret words is sought. Between 2000 and 2010, 295 dictionary definitions were cited in 225 US Supreme Court opinions. In contrast, I could find only four UK Supreme court decisions between 2009 and now that mention dictionaries. American judicial reliance on dictionaries leaves lexicographers and law scholars uneasy; most dictionaries aim to describe common usage, rather than prescribe the best interpretation for a word. Furthermore, dictionaries differ; something as slight as the presence or absence of a the or a usually might have a great impact on a literalist’s interpretation of a law. And yet US Supreme Court dictionary citation has risen by about ten times since the 1960s.

No particular dictionary is America’s Bible—but that doesn’t stop the worship of dictionaries, just as the existence of many Bible translations hasn’t stopped people citing scripture in English. The name Webster is not trademarked, and so several publishers use it on their dictionary titles because of its traditional authority. When asked last summer how a single man, Noah Webster, could have such a profound effect on American English, I missed the chance to say: it wasn’t the man; it was the books — the written word. His “Blue-Backed Speller”, a textbook used in American schools for over 100 years, has been called ‘a secular catechism to the nation-state’. At a time when much was unsure, Webster provided standards (not all of which, it must be said, were accepted) for the new English of a new nation.

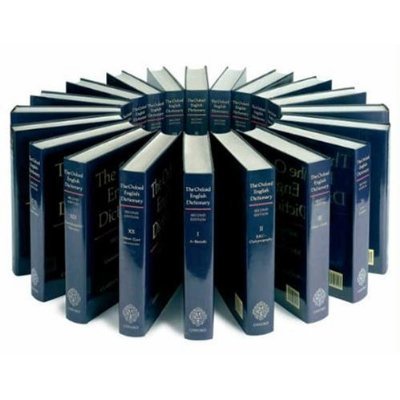

American dictionaries, regardless of publisher, have continued in that vein. British lexicography from Johnson’s dictionary to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has excelled in recording literary language from a historical viewpoint. In more recent decades British lexicography has taken a more international perspective with serious innovations and industry in dictionaries for learners. American lexicographical innovation, in contrast, has largely been in making dictionaries more user-friendly for the average native speaker.

The Oxford English Dictionary, courtesy of Oxford Dictionaries. Do not use without permission.

Local attitudes: marketing dictionaries

By and large, lexicographers on either side of the Atlantic are lovely people who want to describe the language in a way that’s useful to their readers. But a look at the way dictionaries are marketed belies their local histories, the local attitudes toward dictionaries, and assumptions about who is using them. One big general-purpose British dictionary’s cover tells us it is ‘The Language Lover’s Dictionary’. Another is ‘The unrivalled dictionary for word lovers’.

Now compare some hefty American dictionaries, whose covers advertise ‘expert guidance on correct usage’ and ‘The Clearest Advice on Avoiding Offensive Language; The Best Guidance on Grammar and Usage’. One has a badge telling us it is ‘The Official Dictionary of the ASSOCIATED PRESS’. Not one of the British dictionaries comes close to such claims of authority. (The closest is the Oxford tagline ‘The world’s most trusted dictionaries’, which doesn’t make claims about what the dictionary does, but about how it is received.) None of the American dictionary marketers talk about loving words. They think you’re unsure about language and want some help. There may be a story to tell here about social class and dictionaries in the two countries, with the American publishers marketing to the aspirational, and the British ones to the arrived. And maybe it’s aspirationalism and the attendant insecurity that goes with it that makes America the land of the codified rule, the codified meaning. By putting rules and meanings onto paper, we make them available to all. As an American, I kind of like that. As a lexicographer, it worries me that dictionary users don’t always recognize that English is just too big and messy for a dictionary to pin down.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Lynne Murphy, Reader in Linguistics at the University of Sussex, researches word meaning and use, with special emphasis on antonyms. She blogs at Separated by a Common Language and is on Twitter at @lynneguist.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFarmily album: the rise of the felfieHave you heard? Oxford DNB releases 200th episode in biography podcastBeyond Ed Sullivan: The Beatles on American television

Related StoriesFarmily album: the rise of the felfieHave you heard? Oxford DNB releases 200th episode in biography podcastBeyond Ed Sullivan: The Beatles on American television

March 8, 2014

Minority women chemists yesterday and today

As far as we know, the first African American woman PhD was Dr. Marie Daly in 1947. I am still searching for an earlier one.

Women chemists, especially minority women chemists, have always been the underdogs in science and chemistry. African American women were not allowed to pursue a PhD degree in chemistry until the late in the twentieth century, while white women were pursuing that degree in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Racial prejudice was a major factor. Many African American men were denied access to this degree in the United States. The list of those who were able to receive a PhD in chemistry is short. The Knox brothers were able to receive PhDs in chemistry from MIT and Harvard in the 1930s. Some men had to go abroad to get a degree; Percy Julian obtained his from the University of Vienna in Austria.

In 1975, the American Association for the Advancement of Science sponsored a meeting of minority women scientists to explore what it was like to be both a woman and minority in science. The meeting resulted in a report entitled The Double Bind: The Price of being a Minority woman in Science. Most of the women experienced strong negative influences associated with race or ethnicity as children and teenagers but felt more strongly the handicaps for women as they moved into post-college training in graduate schools or later in careers. When the women entered their career stage, they encountered both racism and sexism.

STS-47 Mission Specialist Mae Jemison in the center aisle of the Spacelab Japan (SLJ) science module aboard the Earth-orbiting Endeavour, Orbiter Vehicle (OV) 105. NASA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This is still true today in some respects, but it is often unconscious. For example, the organizers of an International Conference for Quantum Chemistry recently posted a list of the speakers. They were all men (the race of the speakers is not known). Three women who are pillars in the field protested and started a petition to add women to the speakers list. The organizers retracted the speaker list.

In 2009 the National Science Foundation sponsored a Women of Color conference. When I attended the meeting and listened to the speakers, it sounded as if not much had changed for women in science. There is still racism and sexism. Even Asian-American women, who do not constitute a minority within the field, were experiencing the same problems.

The 2010 Bayer Facts of Science Education XIV Survey polled 1,226 female and minority chemists and chemical engineers about their childhood, academic, and workplace experiences. The report stated that, girls are not encouraged to study STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) field early in school, 60% colleges and universities discourage women in science, and 44% of professors discourage female students from pursing STEM degrees.

The top three reasons for the underrepresentation are:

Lack of quality education in math and science in poor school districts

Stereotypes that the STEM isn’t for girls

Financial problems related to the cost of college education

In spite of all the negative information in these reports, women are pursuing STEM careers. In the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers (NOBCChE) women dominate the organization. Years ago, men dominated that organization. The current vice president of the organization is a woman chemical engineer, who is is striving to make the organization better. Many of the NOBCChE female members went to Historically Black Colleges (HBCUs) for undergraduate degree before getting into major universities to obtain their PhD. The HBCUs are the savior for African American students because the professors and administration strive to help them succeed in college.

I am amazed at all these African American women scientists have done in spite of racism and sexism — succeeding and thriving in industry, working as professors and department chairs in major research universities, and providing role models to young women and men who are contemplating a STEM career.

Jeannette Elizabeth Brown is the author of African American Women Chemists. She is a former Faculty Associate at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. She is the 2004 Société de Chimie Industrielle (American Section) Fellow of the Chemical Heritage Foundation, and consistently lectures on African American women in chemistry.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Minority women chemists yesterday and today appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories8 марта 1979: Women’s Day in the Soviet UnionA record-breaking lunar impactCollective emotions and the European crisis

Related Stories8 марта 1979: Women’s Day in the Soviet UnionA record-breaking lunar impactCollective emotions and the European crisis

8 марта 1979: Women’s Day in the Soviet Union

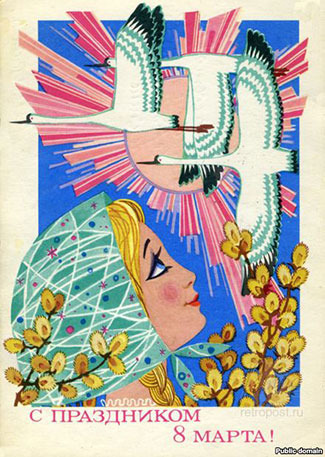

“March 8 is Women’s Day, a legal holiday,” I wrote to my mother from Moscow. “This is one of the many cute cards that is on sale now, all with flowers somewhere on them. We hope March 8 finds you well and happy, and enjoying an early spring! Alas, here it is -30° C again.”

Soviet-era Women’s Day card. Public Domain via Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty.

I spent the 1978-79 academic year working in Moscow in the Soviet Academy of Science’s Institute of Crystallography. I’d been corresponding with a scientist there for several years and when I heard about the exchange program between our nations’ respective Academies, I applied for it. Friends were horrified. The Cold War was raging, and Afghanistan rumbled in the background. But scientists understand each other, just like generals do. I flew to Moscow, family in tow, early in October. The first snow had fallen the night before; women in wool headscarves were sweeping the airport runways with birch brooms.

None of us spoke Russian well when we arrived; this was immersion. We lived on the fourteenth floor of an Academy-owned apartment building with no laundry facilities and an unreliable elevator. It was a cold winter even by Russian standards, plunging to -40° on the C and F scales (they cross there). On weekdays, my daughters and I trudged through the snow to the broad Leninsky Prospect. The five-story brick Institute sat on the near side, and the girls went to Soviet public schools on the far side, behind a large department store. The underpass was a thriving illegal free-market where pensioners sold hard-to-find items like phone books, mushrooms, and used toys. Nearing the schools, we ran the ever-watchful Grandmother Gauntlet. In this country of working mothers, bundled bescarved grandmothers shopped, cooked, herded their charges, and bossed everyone in sight: Put on your hat! Button up your children!

At the Institute, I was supposed to be escorted to my office every day, but after a few months the guards waved me on. I couldn’t stray in any case: the doors along the corridors were always closed. Was I politically untouchable?

But the office was a friendly place. I shared it with three crystallographers: Valentina, Marina, and the professor I’d come to work with. We exchanged language lessons and took tea breaks together. Colleagues stopped by, some to talk shop, some for a haircut (Marina ran a business on the side). Scientists understand each other. My work took new directions.

I also tried to work with a professor from Moscow State University. He was admired in the west and I had listed him as a contact on my application. But this was one scientist I never understood. He arrived late for our appointments at the Institute without excuses or apologies. I was, I soon surmised, to write papers for him, not with him. I held my tongue, as I thought befits a guest, until the February afternoon he showed up two weeks late. Suddenly the spirit of the grandmothers possessed me. “How dare you!” I yelled in Russian. “Get out of here and don’t come back!” “Take some Valium” Valentina whispered; wherever had she found it? But she was as proud as she was worried. The next morning I was untouchable no more: doors opened wide and people greeted me cheerily, “Hi! How’s it going?”

International Women’s Day, with roots in suffrage, labor, and the Russian Revolution, became a national holiday in Russia in 1918, and is still one today. In 1979, the cute postcards and flowers looked more like Mother’s Day cards, but men still gave gifts to the women they worked with. On 7 March I was fêted, along with the Institute’s female scientists, lab technicians, librarians, office staff, and custodians. I still have the large copper medal, unprofessionally engraved in the Institute lab. “8 марта” — 8 March — it says on one side, the lab initials and the year on the other. The once-pink ribbon loops through a hole at the top. Maybe they gave medals to all of us, or maybe I earned it for throwing the professor out of the Institute.

Women’s Day medal, courtesy of Marjorie Senechal.

I’ve returned to Russia many times; I’ve witnessed the changes. Science is changing too; my host, the Academy of Sciences founded by Peter the Great in 1724, may not reach its 300th birthday. But my friends are coping somehow, and I still feel at home there. A few years ago I flew to Moscow in the dead of winter for Russia’s gala nanotechnology kickoff. A young woman met me at the now-ultra-modern airport. She wore smart boots, jeans, and a parka to die for. “Put your hat on!” she barked in English as she led me to the van. “Zip up your jacket!”

Marjorie Senechal is the Louise Wolff Kahn Professor Emerita in Mathematics and History of Science and Technology, Smith College, and Co-Editor of The Mathematical Intelligencer. She is author of I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 8 марта 1979: Women’s Day in the Soviet Union appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInternational Women’s Day: a time for actionA record-breaking lunar impactHow much could 19th century nonfiction authors earn?

Related StoriesInternational Women’s Day: a time for actionA record-breaking lunar impactHow much could 19th century nonfiction authors earn?

International Women’s Day: a time for action

On Saturday, 8 March, we celebrate International Women’s Day. But is there really anything to celebrate?

Last year, the United Nations declared its theme for International Women’s Day to be: “A promise is a promise: Time for action to end violence against women.” But in the United Kingdom in 2012, the government’s own figures show that around 1.2 million women suffered domestic abuse, over 400,000 women were sexually assaulted, 70,000 women were raped, and thousands more were stalked.

So, why is there violence against women?

The United Nations talks about a context of deep-rooted patriarchal systems and structures that enable men to assert power and control over women.

In a nutshell, this means that men’s violence against women is simply the most extreme manifestation of a continuum of male privilege, starting with domination of public discourse and decision-making, taking the lion’s share of global income and assets, and finally, controlling women’s actions and agency by force if necessary.

Throughout history and in most cultures, violence against women has been an accepted way in which men maintain power. In this country, the traditional right of a husband to inflict moderate corporal punishment on his wife in order to keep her “within the bounds of duty” was only removed in 1891. Our lingering ambivalence over the rights and wrongs of intervening in the face of domestic violence (“It’s just a domestic” as the police used to say) continues more than a century later. An ICM poll in 2003 found more people would call the police if someone was mistreating their dog than if someone was mistreating their partner (78% versus 53%). Women recognise this culture of condoning and excusing violence against them in their reluctance even today to exert their legal rights and make an official complaint. The most recent figures from the Ministry of Justice show that only 15% of women who have been raped report it to the police. And when they do, they’re likely to be disbelieved: the ‘no-crime’ rate (where a victim reports a crime but the police decide that no crime took place) for overall police recorded crime is 3.4%; for rape it’s 10.8%. All this adds up to a culture of impunity in which violence can continue.

And it’s exacerbated by our media. When the End Violence against Women Coalition, along with some of our members, were invited to give evidence to the Leveson Inquiry, we argued that:

“reporting on violence against women which misrepresents crimes, which is intrusive, which sensationalises and which uncritically blames ‘culture’, is not simply uninformed, trivial or in bad taste. It has real and lasting impact – it reinforces attitudes which blame women and girls for the violence that is done to them, and it allows some perpetrators to believe they will get away with committing violence. Because such news reporting are critical to establishing what behaviour is acceptable and what is regarded as ‘real’ crime, in the long term and cumulatively, this reporting affects what is perceived as crime, which victims come forward, how some perpetrators behave, and ultimately who is and is not convicted of crime.”

When do states become responsible for private

acts of violence against women?

acts of violence against women?

The UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) says in its General Recommendation No. 19 that states may be responsible for private acts “if they fail to act with due diligence to prevent violations of rights or to investigate and punish acts of violence.”

Due diligence means that states must show the same level of commitment to preventing, investigating, punishing and providing remedies for violence against women as they do other crimes of violence. Arguably, our poor rates of reporting and prosecution suggest that the UK is not fulfilling this obligation.

What are some possible policy solutions to eliminate violence against women?

The last Government developed a national strategy to tackle this problem and the current Government has followed suit, adopting a national action plan that aims to coordinate action at the highest level. This has had the single-minded backing of the Home Secretary, Theresa May — who of course happens to be a woman. Under this umbrella, steps have been taken to focus on what works — although much more needs to be done, for example on the key issue of prevention –changing the attitudes that create a conducive environment for violence. Research by the UN in a number of countries recently showed that 70-80% of men who raped said did so because they felt entitled to; they thought they had a right to sex. Research with young people by the Children’s Commissioner has highlighted the sexual double standard that rewards young men for having sex while passing negative judgment on young women who do so. We need to rethink constructions of gender, particularly of masculinity.

What will the End Violence Against Women Campaign focus on this year?

End Violence Against Women welcomes the fact that the main political parties now recognize that this is a key public policy issue, and we’ll be using the upcoming local and national elections in 2014 and 2015 to question candidates on their practical proposals for ending violence against women and girls. We need to make sure that women’s support services are available in every area. And we’ll be working on our long-term aim of changing the way people talk and think about violence against women and girls — starting in schools, where children learn about gender roles and stereotypes — much earlier than we think. We hope Michael Gove will back our Schools Safe 4 Girls campaign. We also look forward to a historic milestone in April, when the UN special rapporteur on violence against women makes a visit to the UK to assess progress.

On International Women’s Day this year, what is the most urgent issue for the world to focus on?

As Nelson Mandela said: “For every woman and girl violently attacked, we reduce our humanity. Every woman who has to sell her life for sex we condemn to a lifetime in prison. For every moment we remain silent, we conspire against our women.” While women across the world are raped and murdered, systematically beaten, trafficked, bought and sold, ending this “undeclared war on women” has to be our top priority.

Janet Veitch is a member of the board of the End Violence against Women Coalition, a coalition of activists, women’s rights and human rights organisations, survivors of violence, academics and front line service providers calling for concerted action to end violence against women. She is immediate past Chair of the UK Women’s Budget Group. She was awarded an OBE for services to women’s rights in 2011.

On 22 March 2014, the University of Nottingham Human Rights Law Centre will be hosting the 15th Annual Student Human Rights Conference ‘Mind the Gender Gap: The Rights of Women,’ and Janet Veitch will be among the experts on the rights of women who will be speaking. Full details are available on the Human Rights Law Centre webpage.

Human Rights Law Review publishes critical articles that consider human rights in their various contexts, from global to national levels, book reviews, and a section dedicated to analysis of recent jurisprudence and practice of the UN and regional human rights systems.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Crying woman sitting in the corner of the room, with phone in front of her to call for help. © legenda via iStockphoto.

The post International Women’s Day: a time for action appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhole life imprisonment reconsideredA record-breaking lunar impactFluoridation of drinking water supplies: tapping into the debate

Related StoriesWhole life imprisonment reconsideredA record-breaking lunar impactFluoridation of drinking water supplies: tapping into the debate

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers