Oxford University Press's Blog, page 820

April 21, 2014

Putin in the mirror of history: Crimea, Russia, empire

Contrary to those who believe that Vladimir Putin’s political world is a Machiavellian one of cynical “masks and poses, colorful but empty, with little at its core but power for power’s sake and the accumulation of vast wealth,” Putin often speaks quite openly of his motives and values—and opinion polls suggest he is strongly in sync with widespread popular sentiments. A good illustration is his impassioned speech on 18 March to a joint session of the Russian parliament about Crimea’s secession and union with Russia (an English translation is also available on the Kremlin’s website). The history of Russia as a nation and an empire are key themes:

“In Crimea, literally everything is imbued with our common history and pride. Here is ancient Chersonesus, where the holy Prince Vladimir was baptized. His spiritual feat of turning to Orthodoxy predetermined the shared cultural, moral, and civilizational foundation that unites the peoples of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. In Crimea are the graves of Russian soldiers, whose bravery brought Crimea in 1783 under Russian rule. Crimea is also Sevastopol, a city of legends and of great destinies, a fortress city, and birthplace of the Russian Black Sea fleet. Crimea is Balaklava and Kerch, Malakhov Kurgan and Sapun Ridge [major battle sites during the Crimean War and World War II]. Each one of these places is sacred for us, symbols of Russian military glory and unprecedented valor.”

No less revealing is his reflection on the relationships uniting the diverse peoples of Russia.

“Crimea is a unique fusion of the cultures and traditions of various peoples. In this, it resembles Russia as a whole, where over the centuries not a single ethnic group has disappeared. Russians and Ukrainians, Crimean Tatars, and representatives of other nationalities have lived and worked side by side in Crimea, each retaining their own distinct identity, tradition, language, and faith.”

How Russians have often understood their history as an “empire” (though the word is no longer favored) pervades these words and Putin’s thinking.

Try to figure out Putin’s mind—getting “a sense of his soul,” as George W. Bush famously thought he had seen after meeting Putin in 2001—has long been a political preoccupation, and has become especially urgent since the events in Crimea in March. Until now, most commentators viewed Putin as a rational and potentially constructive “partner” in international affairs. Even the growing crackdown on civil society and dissidence, though much criticized, did not undermine this belief. Russia’s annexation of Crimea shattered this confidence. German chancellor Angela Merkel declared that Putin seemed to be living “in another world.” Influential commentators in the United States declared that these events unmasked the real Putin, (Obama’s former national security advisor, Tom Donilon), revealing a revanchist desire “to re-establish Russian hegemony within the space of the former Soviet Union” (former US ambassador to the United Nations, John Bolton) by a “cynical,” power-hungry, “neo-Soviet” despot seeking to reclaim “the Soviet/Russian empire” (Matthew Kaminski of the Wall Street Journal). A less radical reassessment, but with roughly the same conclusion, is President Obama’s argument that Putin “wants to, in some fashion, reverse…or make up for” the “loss of the Soviet Union.” In this light, the key question becomes “how to stop Putin?”

History haunts arguments about what Putin thinks, how much further he might go, and what should be done. Some commentators focus on how Putin sees himself in history. The Republican chairman of the US House of Representative’s Intelligence Committee, Mike Rogers, told Meet the Press that “Mr. Putin…goes to bed at night thinking of Peter the Great and he wakes up thinking of Stalin.” The logical conclusion is that if we do not stop Putin “he is going to continue to take territory to fulfill what he believes is rightfully Russia.” Others think of historical analogies. The former US National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, for example, writing in the Washington Post, described Putin as “a partially comical imitation of Mussolini and a more menacing reminder of Hitler,” making the Crimea annexation, if West does not act, “similar to the two phases of Hitler’s seizure of the Sudetenland after Munich in 1938 and the final occupation of Prague and Czechoslovakia in early 1939.” Echoing these interpretations are scores of satirical images of Putin as Stalin and Hitler that have appeared at demonstrations and in social media (images of Putin as Peter the Great, more common once, are seen as too flattering now).

Putin himself has a lot to say about history in his 18 March 2014 speech. He points, as he often has, to the recent history of humiliation and insults suffered by Russia at the hands of “our western partners” who treat Russia not as “an independent, active participant in international affairs,” with “its own national interests that need to be taken into account and respected,” but as a backward or dangerous nation to dismiss and “contain.” Worse, the Western powers seem to believe in their own “chosenness and exceptionalism, that they can decide the fate of the world, that they alone are always right.” Rulers since Peter the Great have been fighting for Russia to be respected and included, and generally along the same two fronts: proving that Russia deserves equal membership in the community of “civilized” nations through modernizing and Europeanizing reforms, and winning recognition through demonstrations of political and military might, “glory and valor” (in Putin’s phrase). That Russia was famously disgraced during the original Crimean War, revealing levels of economic and military backwardness that inspired a massive program of reform, and that Western commentators now are expressing surprised admiration at the advances in technique and command seen among the Russian army since it was last seen in the field in Georgia, is not only surely gratifying to Putin (who has made military modernization a priority) but part of an important story about nation and history.

Putin also has a lot to say about empire. In the nineteenth century, a theme in Russian thinking about empire was that Russians rule the diversity of its peoples not with self-interest and greed, like European colonialists, but with true Christian love, bringing their subjects “happiness and abundance,” in Michael Pogodin’s words. As Nicholas Danilevsky put it in 1871, Russia’s empire was “not built on the bones of trampled nations.” The Soviet version of this imperial utopianism was the famous “friendship of peoples” (druzhba narodov) of the USSR. Putin, we see, echoes this ideal. He also directs it against ethnic nationalisms that suppress minorities (above all, Russian speakers in Ukraine). Hence his warnings about the role of “nationalists, neo-Nazis, Russophobes, and anti-Semites” in the Ukrainian revolution, and his declaration that Crimea under Russian rule would have “three equal state languages: Russian, Ukrainian, and Crimean Tatar,” in deliberate contrast to the decree of the post-Yanukovych Ukrainian parliament that Ukrainian would be the only official language of the country (later repealed).

Of course, the Russian empire and the Soviet Union were not harmonious multicultural paradises, nor is the Russian Federation, but the ideal is still an influence in Russian thinking and policy. At the same time, Putin contradicts this simple vision in worrisome ways. A good example is how he wavers in his March speech between defining Ukrainians as a separate “people” (narod, which also means “nation”) or as part of a larger Russian nation. Until the twentieth century, very few Russians believed that Ukrainians were a nation with their own history and language, and many still question this. Putin works both sides of this argument. On the one hand, he expresses great respect for the “fraternal Ukrainian people [narod],” their “national feelings,” and “the territorial integrity of the Ukrainian state.” On the other hand, he argues that what has been happening in Ukraine “pains our hearts” because “we are not simply close neighbors but, as I have said many times already, we are truly one people [narod]. Kiev is the mother of Russian [russkie] cities. Ancient Rus is our common source and we cannot live without each other.”

Putin’s frequent use of the ethno-national term russkii for “Russian,” rather than the more political term rossiiskii, which includes everyone and anything under the Russian state, is important. Even more ominous are Putin’s suggestions about where such an understanding of history should lead. Reminding “Europeans, and especially Germans,” about how Russia “unequivocally supported the sincere, inexorable aspirations of the Germans for national unity,” he expects the West to “support the aspirations of the Russian [russkii] world, of historical Russia, to restore unity.” This suggests a vision, shaped by views of history, that goes beyond protecting minority Russian speakers in the “near-abroad.”

Putinism often tries to blend contradictory ideals—freedom and order, individual rights and the needs of state, multiethnic diversity and national unity. Dismissing these complexities as cynical masks does not help us develop reasoned responses to Putin. Most important, it does not help people in Russia working for greater freedom, rights, and justice, who are marginalized (and often repressed) when Russia feels under siege. “We have every reason to argue,” he warned in his March speech, “that the infamous policy of containing Russia, which was pursued in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, continues today. They are constantly trying to sweep us into a corner.” Of course, Putin is not wrong to speak of Western arrogance toward Russia (though he is hardly a model of respect for international norms) nor to warn of the dangers of intolerant ethnic nationalism (though he looks the other way at Russia’s own “nationalists, neo-Nazis, and anti-Semites”). That he can be hypocritical and cynical does not mean his thinking and feelings are “empty,” much less that he has lost touch with reality or with the views of most Russians.

A version of this article originally appeared on HNN.

Mark D. Steinberg is Professor of History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He is the author or editor of books on Russian popular culture, working-class poetry, the 1917 revolution, religion, and emotions. His most recent books are Petersburg Fin-de-Siecle (Yale University Press, 2011) and the eighth edition of A History of Russia, with the late Nicholas Riasanovsky, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. He is currently writing a history of the Russian Revolution.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Vienna, Austria – March 30, 2014: A sign made up of a photo composite of Vladimir Putin and Hitler looms over protesters who have gathered in the main square in Vienna to protest Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine. © benstevens via iStockphoto.

The post Putin in the mirror of history: Crimea, Russia, empire appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineThe economics of sanctionsThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play by

Related StoriesWestern (and other) perspectives on UkraineThe economics of sanctionsThe Ukraine crisis and the rules great powers play by

The contours and conceptual position of jus post bellum

In our previous post, “Jus post bellum and the ethics of peace,” we introduced the concept of jus post bellum, including its history, functions, and varied definitions. Because jus post bellum can operate simultaneously with related but distinguishable concepts, it is important to keep the goals of related concepts clear. Jus post bellum may serve a particular function in facilitating choice among competing interests in the transition from armed conflict to peace.

Relationship to related concepts

Jus post bellum overlaps with Responsibility to Protect (R2P), Transitional Justice, and the law of peace. It is sometimes even argued that it forms part of these concepts, but there are differences.

The concept of transitional justice emerged in the context of the post-democratic transitions of the 1990s. Traditionally, it has a different focus than jus post bellum. It is geared towards accountability for past violations and the establishment of new political order that would prevent human rights violations from re-occurring. Jus post bellum is not a ‘human rights’ or ‘justice’ project per se. It is geared at peacebuilding more broadly, focusing on the organization of the interplay between actors, norms, and institutions in situations of transitions, and the establishment of sustainable peace.

Jus post bellum is also distinct from Responsibility to Protect. R2P was developed to provide authority for protective duties and response schemes, through a definition of sovereignty as responsibility. Its application is linked to atrocity crimes. This trigger has oriented the concept towards prevention and response to conflict. Ethics of care in the aftermath of conflict have been side-lined in its operation. Jus post bellum is tied to the ending of hostilities. It entails certain due diligence obligations towards intervention, but is mostly focused on the organization of post-conflict peace. It includes negative obligations (i.e. ‘do no harm’ principle) and positive duties. In some cases, conduct may be warranted by R2P (e.g. continued international presence), but sanctioned under jus post bellum, i.e. due to lack of consent (e.g. unlawful occupation).

Monrovia, Liberia – 24 February 2012: The abandoned Ministry of Defence building stands empty and ruined, a reminder of the civil war here not so long ago. © MickyWiswedel via iStockphoto.

Content

In just war theory, some attempts have been made to define the ideal content of a jus post bellum. Areas included in this checklist are:

Disarmament, Demilitarization, Re-integration (DDR)

Compensation

Punishment

Constitutional reform

Economic reconstruction

This ‘toolbox’ logic deserves critical scrutiny. These factors are typically tied to international armed conflicts, rather than dilemmas of internal armed conflicts, or mixed conflicts. More fundamentally, there is an inherent danger that jus post bellum might be used to tell what a ‘just society’ ought to look like.

An alternative way to think about content is to view jus post bellum as a mechanism to facilitate choice among competing interests. The concept provides an incentive to integrate the goal of sustainable peace into decision-making processes requiring a balancing of conflicting rationales. For example, this is relevant to peace arrangements, processes of governance, and redress for victims. How should ‘consent’ used in peace negotiation and peacebuilding efforts, and how inclusive should it be? What factors should be taken into account in the restoration of public authority and democratic rule? How can judicial reform be reconciled with ‘vetting’ of institutions? To what extent is there an adequate equilibrium between protection of fundamental freedoms and socio-economic rights in post-conflict settlements? Is damage repaired in a way that that addresses harm and needs of post-conflict societies?

Such choices require a certain ‘margin of appreciation’. In some areas, a deviation from peacetime standards may be acceptable. Classical examples are collective reparation, the focus on targeted accountability, or conditional amnesties.

Jus post bellum may also offer some guidance for specific procedures. One example is the permissibility of derogation from human rights, including their justification and declaration. Existing principles have been applied primarily in the context of human rights obligations of States. In the context of jus post bellum, such principles become relevant in relation to other entities, such as regional organizations, peace operations, or the Security Council.

Another example is ‘sequencing’ and coordination of the temporal application of specific responses. Under a ‘justice after war’ perspective, classical dilemmas of peace v. justice are at forefront of attention. In the context of peacebuilding, sequencing gains broader importance in additional areas, such as the timing of elections or the determination of status issues. Jus post bellum may further determine parameters for ‘exit’ after intervention.

The fundamental problems of minimizing the evils of war and building a robust peace are not new, but they are often treated as new. Too often, contemporary peacebuilding difficulties are treated as essentially unprecedented, when in fact legal history could serve as a valuable aide. A key thesis of jus post bellum is that the rich legal and philosophical traditions that guide the law of armed conflict and the general prohibition on the use of force could also inform the transition from war to peace. Unfortunately, these traditions are too often ignored. Rather than being depreciated or held sacred, those traditions must be refreshed and revisited if they are to be applied meaningfully to contemporary problems. We could extend the dualistic approach of jus ad bellum and jus in bello to a tripartite conception that includes jus post bellum. Such a conception would cover the entire process of entering into armed conflict, fighting, and exiting from armed conflict. This more comprehensive approach would improve our capacity to manage the enduring difficulties inherent in ending war and building peace. Jus post bellum does not offer the promise of a more comprehensive approach on its own, but only in combination with other, related concepts. Together, however, they offer the promise of transitions to peace that are both more just and more secure.

Carsten Stahn, Jennifer S. Easterday, and Jens Iverson are the editors of Jus Post Bellum: Mapping the Normative Foundations. Carsten Stahn is Professor of International Criminal Law and Global Justice and Programme Director of the Grotius Centre for International Studies, Universiteit Leiden. Jennifer S. Easterday is a Ph.D Researcher, Faculteit Rechtsgeleerdheid, Instituut voor Publiekrecht, Internationaal Publiekrecht, Universiteit Leiden. Jens Iverson is a Researcher for the ‘Jus Post Bellum’ project and an attorney specializing in public international law, Universiteit Leiden.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The contours and conceptual position of jus post bellum appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJus post bellum and the ethics of peaceChallenges to the effectiveness of international lawPreparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meeting

Related StoriesJus post bellum and the ethics of peaceChallenges to the effectiveness of international lawPreparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meeting

A religion reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

By Kirsty Doole

Religion has provided the world with some of the most influential and important written works ever known. Here is a reading list made up of just a small selection of the texts we carry in the series, covering religions across the globe.

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People – Bede

Bede’s most famous work was finished in 731, and deals with the history of Christianity in England, most notably, the tension between Roman and Celtic forms of Christianity. It is one of the most important texts in English history. As well as providing the authoritative Colgrave translation of the Ecclesiastical History, the Oxford World’s Classics edition includes a translation of the Greater Chronicle, in which Bede discusses the Roman Empire. Meanwhile, Bede’s Letter to Egbert gives further reflections on the English Church just before his death.

The Varieties of Religious Experience – William James

This work is William (brother of Henry) James’s classic survey of religious belief in its most personal aspects. Covering such topics as how we define evil to ourselves, the difference between a healthy and a divided mind, the value of saintly behaviour, and what animates and characterizes the mental landscape of sudden conversion, The Varieties of Religious Experience is a key text examining the relationship between belief and culture. At the time James wrote it, faith in organized religion and dogmatic theology was fading away, and the search for an authentic religion rooted in personality and subjectivity was something deemed an urgent necessity. With psychological insight, philosophical rigour, and a determination not to jump to the conclusion that in tracing religion’s mental causes we necessarily diminish its truth or value, in the Varieties James wrote a truly foundational text for modern belief.

On Christian Teaching – Saint Augustine

On Christian Teaching – Saint Augustine

This is one of Saint Augustine’s most important works on the classical tradition. Written to enable students to have the skills to interpret the Bible, it provides an outline of Christian theology. It also contains a detailed discussion of moral problems. Further to that, Augustine attempts to determine what elements of classical education are desirable for a Christian, and suggests ways in which Ciceronian rhetorical principles may help in communicating faith.

Along with the King James Bible, the words of the Book of Common Prayer have permeated deep into the English language all over the worldFor countless people, it has provided the framework for a wedding ceremony or a funeral. Yet this familiarity also hides a violent and controversial history. When it was first written, the Book of Common Prayer provoked riots, and it was banned before eventually being translated into a host of global languages. This edition presents the work in three different states: the first edition of 1549, which brought the Reformation into people’s homes; the Elizabethan prayer book of 1559, familiar to Shakespeare and Milton; and the edition of 1662, which embodies the religious temper of the nation down to modern times.

The Qur’an, the Muslim Holy Book, was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad over 1400 year ago. It is the supreme authority in Islam and the source of all Islamic teaching; it is both a sacred text and a book of guidance, that sets out the creed, rituals, ethics, and laws of Islam. The greatest literary masterpiece in Arabic, the message of the Qur’an was directly addressed to all people regardless of class, gender, or age, and this translation aims to be equally accessible to everyone.

Natural Theology – William Paley

Natural Theology is arguably as central to those who believe in Intelligent Design as Darwin’s Origin of Species is to those who come down on the side of evolutionary theory. In it, William Paley set out to prove the existence of God from the evidence of the order and beauty of the natural world. It famously starts by comparing our world to a watch, whose design is self-evident, before going on to provide examples from biology, anatomy, and astronomy in order to demonstrate the intricacy and ingenuity of design that could only come from a wise and benevolent deity. Paley’s work was both hugely successful, and extremely controversial, and Charles Darwin was greatly influenced by the book’s accessible style and structure.

‘I have heard the supreme mystery, yoga, from Krishna, from the lord of yoga himself.’

So ends the Bhagavad Gita, the best known and most widely read Hindu religious text in the Western world. It is the most famous episode from the great Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata. Across eighteen chapters Krishna’s teaching leads the warrior Arjuna from confusion to understanding, raising and developing many key themes from the history of Indian religions in the process.

It considers religious and social duty, the nature of action and of sacrifice, the means to liberation, and the relationship between God and human. It culminates in an awe-inspiring vision of Krishna as an omnipotent God, disposer and destroyer of the universe.

Kirsty Doole is Publicity Manager for Oxford World’s Classics.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Saint Augustine of Hippo. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post A religion reading list from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMoney mattersAn Irish literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsWilliam Godwin’s birthday

Related StoriesMoney mattersAn Irish literature reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsWilliam Godwin’s birthday

April 20, 2014

Easter rites of initiation bring good news for American Catholics

For many Catholics in America, waking up in the morning to find no news about the church is a relief. They won’t have to deal with stories about the lingering stench of the priest sexual abuse scandal, the consolidation of parishes and closing of schools, controversy over Catholic hospitals and the loss of Catholic youth, fewer and older nuns and more and younger “nones.”

But what if no news was not the only good news? What if Catholics turned on their TVs and opened their papers on Easter Sunday and heard some real good news instead?

Family watching television 1958. Image credit: CC 2.0 via Flickr.

At Easter Vigil Masses on Saturday night, 19 April, something truly remarkable will take place. Tens of thousands of adults in thousands of parishes across the United States became Catholic. For most of them, this rite of passage is the climax of a months- (and in some cases years-) long process of formation called the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA).

As I have written previously, the implementation of this modernized ancient process of initiation is an excellent example of the contemporary re-invention of rites of passage and a fruitful legacy of the Second Vatican Council. It is a Catholic success story.

Sign reserving pews for the Catechumens. Photo by John Ragai. CC 2.0 via Flickr.

Although based on a single, universal ritual text, the way the RCIA process is implemented differs from parish to parish. We do well to remember a variant on Tip O’Neill’s quip that “all politics is local.” All Catholicism is local. In some parishes we find elaborate and beautiful rituals, rich with fragrant oils and soaring hymns and full body immersion in the waters of baptism. In some parishes, we see minimalistic ceremonies that strain the use of the term ritual.

Regardless of the quality of the celebration, however, through the sacraments of initiation—baptism, confirmation, and Eucharist—individuals become Catholic. When the officiating minister speaks the words and performs the actions of the sacraments—“I baptize you…” and “Be sealed…” and “Receive the Body of Christ”—from the perspective of the church, they have the intended effect. It does not matter if the priest says the words excitedly, sincerely, or in a monotone while yawning under his breath. It does not matter if a team of 20 catechists and thousands of parishioners welcome the new Catholic warmly and profusely, or if a single deacon rushes through a minimalistic ceremony while a few dozen assembled individuals wait impatiently for communion. It does not matter if the symbols of the initiation ceremony are rich or sparse. An individual who receives the sacraments of initiation in a Catholic Church is a Catholic. The individual now can check the “Catholic” box, join a parish, receive communion, get married in the church, and so on.

Dark Side of the Moon album cover. Via pinkfloyd.com.

This fact reminds us that, at the same time that all Catholicism is local, we can also say that no Catholicism is only local. Without the universal church, there would be no RCIA process in local parishes. The Vatican II document Sacrosanctum Concilium (promulgated in 1963) led to the editio typica of the Ordo Initiationis Christianae Adultorum (issued in 1972), which led to the vernacular typical edition of the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (published in 1988), which has gradually been implemented in US parishes. Understanding this movement from universal to local is important. I think of this as being like the image on the cover of Pink Floyd’s album, “Dark Side of the Moon.” The album cover shows a beam of white light hitting a triangular prism, which refracts it to create a rainbow of colors. The culture and resources of local parishes do act as prisms, but without the light, you have no rainbow.

With unprecedented opportunities to choose a religion (or no religion) and to choose how to practice that religion (or not practice), the fact that tens of thousands of people still voluntarily chose Catholicism again this year is indeed good news for American Catholics.

David Yamane teaches sociology at Wake Forest University and is author of Becoming Catholic: Finding Rome in the American Religious Landscape. He is currently exploring the phenomenon of armed citizenship in America as part of what has been called “Gun Culture 2.0″—a new group of individuals (including an increasing number of women) who have entered American gun culture through concealed carry and the shooting sports. He blogs about this at Gun Culture 2.0. Follow him on Twitter @gunculture2pt0.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Easter rites of initiation bring good news for American Catholics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInitiation into America’s original megachurchReinventing rites of passage in contemporary AmericaPreparing for INTA 2014, the first annual meeting in Asia

Related StoriesInitiation into America’s original megachurchReinventing rites of passage in contemporary AmericaPreparing for INTA 2014, the first annual meeting in Asia

Is CBD better than THC?: exploring compounds in marijuana

Marijuana is the leafy material from Cannabis indica plant that is generally smoked. By weight, it typically contains 2%-5% delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive agent. However the plant also contains about fifty other cannabinoid-based compounds, including cannabidiol (CBD).

One Internet ad claims that “cannabidiol (CBD) can cure arthritis, multiple sclerosis, chronic pain, schizophrenia, and epilepsy.” CBD is the main non-psychotropic cannabinoid present in the Cannabis sativa plant, constituting up to 40% of its extract. Somehow this one particular component of the marijuana plant has become much more popular than all of the sixty (at least) other biologically active molecules that have been isolated from this plant, to the point where growers are breeding marijuana plants with significantly higher levels of CBD.

Why are people so excited about CBD? The answer lies in unpacking a series of complex truths, making distinctions between what is known and what is not known, and dispelling some false claims.

The human brain naturally possesses a pair of protein receptors that respond to endogenous marijuana-like chemicals. These receptors are incredibly common and are found throughout the human brain. When a person smokes marijuana, all of the various chemicals in the plant are inhaled, ultimately, into the brain where they find and bind to these receptors, similar to a key fitting into a lock. Which receptors are affected, and what parts of the brain are involved, differs for just about everyone, depending upon their genetic make-up, drug-taking history, and expectations regarding the experience; the last factor being commonly known as the placebo effect.

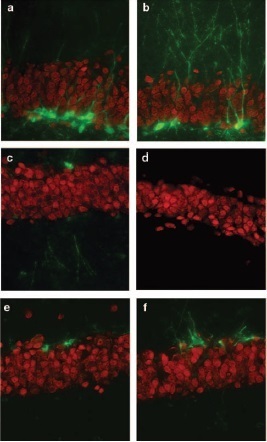

The images above come from Dr. Wenk’s research at Ohio State University, and demonstrate an increase in hippocampus neuron activity in rats following a cannabinoid treatment.

In addition, the chemicals inhaled into the brain also interact with a complex array of other neural systems; these interactions also contribute to the overall psychoactive experience, such as the marijuana’s ability to reduce anxiety, produce euphoria, or induce “the munchies.” My own research has demonstrated the positive effects of stimulation of the endogenous cannabinoid neural system in the aging brain.Both CBD and THC are capable of interacting with this complex variety of proteins. However, and this is where things get interesting, they do not do so with the same degree of effectiveness. Scientists have shown that THC is over one thousand times more potent than is CBD, meaning a person would need to consume 1,000 “joints” of the genetically modified CDB-marijuana plant to get high. This chemical property of CBD has led to the accurate claim that CBD does not make one feel “high.” However, the low potency of CBD may also indicate that, by itself, it offers limited clinical benefits – currently- no one knows. Animal studies have discovered many beneficial effects of CBD but only when administered at very high doses.

What has become quite apparent is that no single component of the plant is entirely good or bad, therapeutic or harmful, or deserving of our complete attention. To date, all of the positive evidence supporting the use of medical marijuana in humans has come from studies of the entire plant or experimental investigations of THC. Given the very low potency of CBD within the brain it is highly unlikely that CBD alone will provide significant clinical benefit. Some small clinical trials are being initiated; until rigorous scientific studies are completed no one can claim that CBD is better than THC.

Gary L. Wenk, PhD., a Professor of Psychology & Neuroscience & Molecular Virology, Immunology and Medical Genetics at the Ohio State University and Medical Center, is a leading authority on the consequences of chronic brain inflammation and animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. He is also the author of Your Brain on Food: How Chemicals Control Your Thoughts and Feelings.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: First image is from United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is CBD better than THC?: exploring compounds in marijuana appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe 4/20 updateThe continuing threat of nuclear weaponsIdentifying unexpected strengths in adolescents

Related StoriesThe 4/20 updateThe continuing threat of nuclear weaponsIdentifying unexpected strengths in adolescents

The 4/20 update

A lot has changed this year in cannabis prohibition. Science and policy march on. Legendary legalization laws in Colorado and Washington have generated astounding news coverage. Maryland is the latest state to change policies. A look at these states can reveal a lot about the research on relevant topics, too.

Colorado and Taxes

Colorado provides taxed and regulated access to recreational users for the first time since 1937’s Marijuana Tax Act. Money rolls into the state’s coffers (roughly $3.4 million in January and February) and the sky has yet to fall. Some observers grouse that the taxes on the recreational market are not generating as much as pundits predicted, as if economic wonks have never guessed wrong before. Apparently, fewer medical users switched from their medical sources to the recreational suppliers. Given that the tax on medical cannabis is 2.9% and the recreational sources cost an additional 25%, we shouldn’t be stunned. It’s nice to see that people behave rationally. It’s only been a few months (since 1 January 2014), but the anticipated spikes in emergency room visits, psychotic breaks, and teen use are nowhere to be found.

Washington and DUI

Washington State continues to hammer out details for how their legal market will work. A per se driving law there has generated controversy. All 50 states prohibit driving while impaired after using cannabis, but the majority require prosecutors to prove recent use and unsafe operation. In contrast, these per se laws essentially make it illegal to drive with a specified amount of cannabis metabolites in the blood. Perfectly competent, safe drivers with the specified amount of metabolites are still breaking the law. For Washington State, the specified amount is 5ng/ml. Unfortunately, this level does not say much about actual impairment and laws like these don’t decrease traffic fatalities. Medical users, who often have more than the specified amount of metabolites, are particularly worried. Though they have developed tolerance to the plant with frequent use and likely show fine driving skill, they remain open for arrest. Plenty of prescription and over-the-counter medications have the potential to impair driving, but comparable laws for these drugs are not on the books. Given the potential for biased enforcement, per se laws like these will undoubtedly face challenges. Standard roadside sobriety tests like those used for alcohol, though less than perfect, might be fairer.

Maryland and Rising Change

A few days ago, the governor of Maryland signed bills removing criminal penalties for possession of small amounts of cannabis and setting up medical distribution. Citizens there caught with 10 grams of the plant risk arrest, a criminal record, a $500 fine, and up to 90 days in jail. After 1 October 2014, they’ll get slapped with a $100 fine for their first offense. Decriminalization can mean different things in different states, especially given the varied styles of police enforcement in each area. But comparable laws appear in Alaska, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, and others. These laws have the potential to free up law enforcement time to decrease serious crimes.

Maryland will also become the 21st medical cannabis state. Over a third of the US population lives in states with medical cannabis laws now, but the details of distribution remain perplexing. Markedly fewer have access than this statistic would imply. Medical marijuana laws have provided the plant for the sickest of the sick, but without increasing teen use. They also appear to decrease traffic fatalities, perhaps by decreasing alcohol consumption. Medical marijuana laws appear to lower suicide rates in men by 5%, perhaps also via the impact on drinking.

Reaching the Public

A Pew Poll earlier this month suggests that data like these and changes in state laws accompany altered public opinion.

More people than ever (52%) support a legal market in the plant. Less than ¼ think possession should lead to jail time. Over 60% think that alcohol is more dangerous than cannabis. With attitudes like these, comparisons to the repeal of alcohol prohibition are loud and numerous. Though no one has a crystal ball and it’s impossible to guess the implications of policies that haven’t been around long, everyone agrees we’re in for an informative and wild ride in the years ahead.

Mitch Earleywine, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Clinical Science and Director of Clinical Training in Psychology at the University of Southern California. He is the author of Pot Politics: Marijuana and the Costs of Prohibition and Understanding Marijuana: A New Look at the Scientific Evidence. He has received nine teaching awards for his courses on drugs and human behavior and is a leading researcher in psychology and addictions. He is Associate Editor of The Behavior Therapist.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bush of a hemp. Lowryder 2. © Yarygin via iStockphoto.

The post The 4/20 update appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe continuing threat of nuclear weaponsIdentifying unexpected strengths in adolescentsA conversation with Craig Panner, Associate Editorial Director of Medicine Books

Related StoriesThe continuing threat of nuclear weaponsIdentifying unexpected strengths in adolescentsA conversation with Craig Panner, Associate Editorial Director of Medicine Books

Trauma happens, so what can we do about it?

Fifteen years ago, 20 April 1999, it happened in my community… at my son’s school. Two heavily armed seniors launched a deadly attack on fellow students, teachers, and staff at Columbine High School in Jefferson County, Colorado.

As the event played out live on broadcast TV, millions around the globe watched in horror as emergency responders evacuated survivors and transported the wounded. At first, a quiet sort of disbelief mixed with shock and anguish descended upon us. Hours later, when the final tally was released – 15 dead, 26 injured – the reality of the tragedy brought the entire community to its knees.

The Columbine shootings became a benchmark event for school violence in the United States. I thought surely this was the turning point; nothing like this would ever happen again. Yet, barely a month later, Conyers, Georgia was added to the list of communities devastated by a shooting. At an alarming rate more towns and neighborhoods join the list, which now includes shootings in theaters, youth camps, shopping malls, and churches.

In 1999, trauma counseling primarily addressed PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) among veterans and victims of domestic violence, abuse, or sexual assault. Few strategies addressed wholesale community trauma. Even less was available to help parents manage the day-to-day challenges of parenting traumatized teens or to advise traumatized educators on teaching students who had witnessed murder in their own school. My response to the situation was to learn as much as I could about what helps people recover from the crushing shock and grief that follows catastrophe, which led me to doctoral research and a continuing focus on trauma as a human experience.

Mass shootings like at Columbine, Sandy Hook, and Utøya, Norway are only one type of trauma we may face. Life has risk, and even the best planning doesn’t ensure invulnerability. Random events happen… accidents, sudden death of a loved one, natural disaster, assault; the list seems endless. Thankfully, effective approaches for promoting recovery are becoming more widely known.

Whenever a tragic event grabs headlines and non-stop media coverage, generous offers support and resources start flooding in. For personal traumas, the situation is different; survivors often suffer in silence as they try to find a way to a livable future alone.

Research that offers insight into trauma’s effects can help us better understand the challenges people face. Efforts to promote public awareness of trauma and recovery offer a genuine benefit. Many are unaware that trauma is a natural human condition, a biologic response to an experience in which the victim feels powerless and overwhelmed in the face of life-threatening or life-changing circumstance.

The human brain is charged with survival, and traumatic response is its attempt to learn from a threatening situation in order to survive threat in the future. Humans try to make sense of their world, and when everything turns to chaos, the brain struggles to learn to identify future risks and to regain a feeling of competence and comfort in the everyday. Behaviors associated with traumatic stress include hypervigilence; extreme sensitivity to smells, sights, and sounds connected to the event; flashbacks; anxiety; anger; depression; and memory problems.

The good news is that even in the face of such challenge, people can successfully integrate their trauma-experience into their own personal history and reclaim their life with a renewed sense of purpose. Victims and their families find that this process takes time and sensitivity. For some, caring friends, family, clergy, and social resources are enough. Others, not everyone, may develop clinical PTSD that best responds to professional counseling. Unfortunately, some may try to “just forget about it” and “get back to the way things used to be,” thereby short-circuiting the process of real recovery. Unresolved trauma can take a high toll on relationships and quality of life.

Trauma’s effect on our lives, as individuals and as communities, may be more widespread than commonly realized. It isn’t a problem faced only by the military; it is not uncommon among civilians. Estimates are that in the United States about 6 out of every 10 men (60%) and 5 of every 10 women (50%) experience at least one traumatic event in their life. For men, it is likely an accident, physical assault, combat, disaster, or witnessing death or injury. For women, the risk is more likely domestic violence, sexual assault, or abuse. A 2004 study reported by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network found that over 50% of children had experienced a traumatic event.

A sense of shame and perceived stigma from needing psychological counseling may keep people from seeking help. Perhaps with education to increase understanding of trauma, more will realize that traumatic response is not a sign of weakness or defect. Instead, it can be a sign of a healthy, normal attempt to reclaim a sense of well-being and safety.

Life after tragedy can bring a deeper sense of purpose and heightened appreciation for living. A former Columbine student I had first interviewed for Reclaiming School in the Aftermath of Trauma: Advice Based on Experience and again later for another study said,

I used to think I was a totally different person after Columbine. That there is no way I could have emerged without being radically altered. And trust me, I was. But what I realize now is that at my core, at my very center, there continues the essence of who I was before, and maybe more importantly, who I was meant to be.

Outcomes such as this are possible. People are slowly recognizing trauma as a critical health issue, not only in the United States but worldwide. Public dialogue can reduce the stigma and isolation felt in trauma’s aftermath. Increased recognition of the occurrence of trauma among civilians and the military, combined with greater awareness of trauma as a natural response, can make a profound difference in the lives of millions. That’s a goal that deserves attention.

Carolyn Lunsford Mears, Ph.D., is a founder of Sandy Hook-Columbine Cooperative, a non-profit foundation dedicated to trauma recovery and resilient communities. She is an award-winning author, speaker, and researcher. She is the author of “A Columbine Study: Giving Voice, Hearing Meaning.” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the Oral History Review. Her 2012 anthology, Reclaiming School in the Aftermath of Trauma, won a prestigious Colorado Book of the Year Award, given by the Colorado affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts, alliance member of the National Centre for Therapeutic Care, Fellow of the Planned Environment Therapy Trust, and Board of Directors member for the I Love You Guys Foundation, and adjunct faculty at the University of Denver.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow the latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images of the Columbine Memorial courtesy of Carolyn Lunsford Mears. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Trauma happens, so what can we do about it? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA call for oral history bloggersThe early history of the guitarTwenty years after the Rwandan Genocide

Related StoriesA call for oral history bloggersThe early history of the guitarTwenty years after the Rwandan Genocide

April 19, 2014

The continuing threat of nuclear weapons

Out of sight. Out of mind.

Nine countries, mainly the United States and Russia, possess 17,000 nuclear weapons, many of which are hundreds of times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki almost 70 years ago. An attack and counterattack in which fewer than 1% of these nuclear weapons were detonated could cause tens of millions of deaths and could disrupt climate globally, leading to crop failures and widespread famine. A greater conflagration could cause a “nuclear winter” and threaten the future of life on earth.

The recent tensions concerning Ukraine demonstrate that although 23 years have elapsed since the end of the Cold War, nuclear weapons remain a clear and present danger to humanity. Persistent threats include accidental launch of nuclear warheads, proliferation of nuclear weapons among nations, potential acquisition and use of nuclear weapons by non-state actors, and diversion of human and financial resources in order to maintain and modernize nuclear arsenals in the United States and other nations.

Despite safeguards, accidental detonation remains a real possibility. A few years ago, a US Air Force plane transported six missiles tipped with nuclear warheads, unbeknownst to the pilot and crew. Twice, in recent weeks, it was revealed that as many as half of navy and air force personnel who maintain nuclear-armed missiles and would be responsible for launching them if commanded to do so had cheated on their competency examinations. In 1995, Boris Yeltsin, then president of Russia, had only a few minutes to decide whether to launch Russian nuclear-armed missiles against the United States in response to what, on radar, looked like a US air attack with multiple re-entry vehicles (MERVs); it turned out to be a rocket launched by a team of Norwegian and US scientists to study the aurora borealis.

Another major concern is that the leaders of the nine nations that possess nuclear weapons each have absolute authority — unchecked by other government officials or institutions, even in the United States — to launch an offensive or allegedly defensive nuclear strike.

Furthermore, proliferation remains a serious threat. During the past decade North Korea obtained nuclear technology and fissile materials, and developed and tested one or more nuclear weapons. At least until recently, Iran apparently was — and may still be — on the path to developing nuclear weapons. Given the widespread knowledge about nuclear technology and the potential availability of fissile material, non-state actors could acquire and use nuclear weapons.

U.S. Air Force Staff Sgt. Betty Puma, from the 5th Munitions Squadron, reviews a nuclear weapons maintenance procedures checklist as part of the Nuclear Surety Inspection (NSI) May 19, 2009, at Minot Air Force Base, N.D. An NSI is designed to evaluate a unit’s readiness to execute nuclear operations. Areas to be evaluated during the NSI include operations, maintenance, security and support activities needed to ensure the wing performs its mission in a safe, secure and reliable manner. This no-notice inspection is expected to conclude May 22. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Miguel Lara III/Released). defenseimagery.mil

Highly-enriched uranium (HEU) — the fissile material used in nuclear weapons — is distributed globally, and used in nuclear reactors to perform research or power aircraft carriers and submarines. Converting to low-enriched uranium would eliminate the possibility of HEU being stolen or otherwise diverted to produce nuclear weapons.

Yet another major concern is the huge diversion of financial resources to maintain and modernize the US nuclear weapons arsenal, estimated over the next 30 years to be about $1 trillion. The proposed nuclear weapons budget of the US Department of Energy for fiscal year 2015 is higher than at any time during the Cold War. Meanwhile, substantial cuts have been proposed in programs to dismantle and prevent proliferation of nuclear weapons — and in programs to reduce poverty and protect human rights.

To most Americans, all of these concerns are out of sight and out of mind. Each of us has a responsibility to become more educated about these issues, increase the awareness of other people about them, and advocate for measures to reduce the dangers associated with nuclear weapons, including the abolition of nuclear weapons.

A longstanding proposal to eliminate all nuclear weapons is the Nuclear Weapons Convention (NWC). In 1997, a consortium of experts in law, science, public health, disarmament, and negotiation drafted a model convention. The Convention would require nations that possess nuclear weapons to destroy them in stages — taking them from high-alert status, removing them from deployment, removing warheads from delivery vehicles, disabling warheads by removing explosive “pits,” and placing fissile material under control of the United Nations. Such a convention has had wide public support throughout the world.

An immediate step that could pave the way to the Nuclear Weapons Convention and the eradication of nuclear weapons is a treaty banning nuclear weapons. Such a treaty could be negotiated with or without the participation of those nations possessing nuclear weapons. It could create an international norm of the illegality of nuclear weapons, similar to the norms that have been established concerning chemical and biological weapons, antipersonnel landmines, and cluster munitions. Such a treaty could put substantial pressure on the nations possessing nuclear weapons to comply with their disarmament obligations — which they have been unwilling to do thus far. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) has mobilized 300 civil-society organizations in 90 countries to campaign, on humanitarian grounds, for such a treaty banning nuclear weapons.

Given resurgent Cold-War-era arguments for revitalizing US nuclear-weapons capabilities to deter Russian actions in Ukraine, we must resist measures that would reset the “Doomsday Clock” to a point that places all humanity — and indeed all life on earth — in great peril of annihilation by nuclear weapons.

Barry S. Levy, M.D., M.P.H., and Victor W. Sidel, M.D., are co-editors of the recently published second edition of Social Injustice and Public Health as well as two editions each of the books War and Public Health and Terrorism and Public Health, all of which have been published by Oxford University Press. They are both past presidents of the American Public Health Association. Dr. Levy is an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Sidel is Distinguished University Professor of Social Medicine Emeritus at Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein Medical College and an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College. Victor W. Sidel was a member of the 1997 consortium of experts in law, science, public health, disarmament, and negotiation that drafted the model Nuclear Weapons Convention. Read their previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The continuing threat of nuclear weapons appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating the life of Nelson Mandela, continuing the quest for social justiceIdentifying unexpected strengths in adolescentsA conversation with Craig Panner, Associate Editorial Director of Medicine Books

Related StoriesCelebrating the life of Nelson Mandela, continuing the quest for social justiceIdentifying unexpected strengths in adolescentsA conversation with Craig Panner, Associate Editorial Director of Medicine Books

Henry James, or, on the business of being a thing

It is virtually impossible for an English-language lexicographer to ignore the long shadow cast by Henry James, that late nineteenth-century writer of fiction, criticism, and travelogues. We can attribute this in the first place to the sheer cosmopolitanism of his prose. James’s writing marks the point of intersection between registers and regions of English that we typically think of as mutually opposed: American and British, Victorian and modernist, intellectual and popular, even the simple good sense of Saxon-Germanicism and the fine silk shades of Franco-Romanticism. Thus, because his writing defies easy categories, it isn’t hard to suppose that James belongs in the back parlor of English-language history, a curiosity of passing interest, but one which, in its very idiosyncrasy, fails to capture the ‘ordinary, everyday’ language.

Henry James in the OED

Nevertheless, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) cites Henry James over one thousand times, often in entries for common English words like use, turn, come, do, and be. At least one explanation for this preponderance is the fact that, precisely because James’s prose incorporates elements from so many different kinds of English, it is uniquely positioned to exemplify—and even differentiate between—very subtle distinctions of usage and meaning. Thus, at green adj. James’s early novel The American provides a downright crystalline use of the phrase green in earth to mean ‘just buried’: ‘He thought of Valentin de Bellegarde, still green in the earth of his burial.’ By adding the final (semantically superfluous) three words, not only does James clarify the phrase’s context, he accentuates its poetic wordplay; its dependence on the double sense of green both as ‘new’ (sense 7a) and as ‘covered with vegetation’ (sense 2a) in order to conjure the renewal of the earth that is part and parcel of the burial rite. In this case, poeticism, often an obstacle to meaning, is actually the most probable explanation for the collocation’s longevity.

This old thing?

James’s ability to write prose that is both fastidiously discerning and euphemistically elliptical is not accidental, and cannot fail to intrigue someone whose business it is to describe words all day. In fact, despite clearly affectionate attachments to a number of words (presence and relation leap to mind), the one I would nominate as James’s absolute favorite is of great concern for lexicography—the thoroughly common word thing. Meaning quite literally any-thing from the genitals (sense 11 c) to a work of art (sense 13, complete with a James citation), thing is remarkably Jamesian in its ability to denote both the most concretely literal elements of reality and the most rarefied abstractions of human thought. And it is in just this respect that the word presents itself at the heart of perhaps the most naïve yet essential question that the lexicographer must answer: whether any particular meaning associated with a given word is actually ‘a thing.’ At times, this can be quite easy: it is not difficult to evaluate whether the physical object we mean when we say ‘smart phone’ is a ‘thing.’ But in many cases, the ‘thing’ referred to by a word is only conceptual. The existence of what we mean by ‘freedom’, for example, cannot be empirically proven. All we can say for sure is that the frequency and manner in which people use such words strongly suggests that they mean specific ‘things’.

Philosophically speaking, what makes ‘thing’ so interesting is that it straddles the gap between words that refer to physical objects and those that refer to abstract concepts, serving as a kind of verbal ‘junk drawer’ where items from both groups get casually tossed, only to wind up completely tangled and confused. Unsurprisingly, this confusion is just what James chooses to explore in his short story ‘The Real Thing.’ Its protagonist is an illustrator visited by two aristocrats, Major and Mrs. Monarch, who have fallen on hard times. They volunteer themselves as models for the artist, presuming that as bona fide members of society they are more suitable subjects for the aristocratic characters he depicts than the working-class types he typically employs. In fact, of course, the couple is awkward and unnatural, unable to embody the concept of aristocracy despite being literal examples of it.

Defining the tooth fairy

In just the same way, when a particular word is used ‘in the real world’, it will almost never be a perfect example of the concept it refers to. Consequently, it becomes the lexicographer’s job to improve upon ‘the real thing’, to illustrate a word more vividly than the real world can. This is especially clear when the word being defined refers to a fictional character, like the tooth fairy. To give wholesale priority to this term as a lexical object would render a definition like ‘a fairy that takes children’s baby teeth after they fall out and leaves a coin under the child’s pillow.’ This covers how the term is ordinarily used, since in everyday speech we are not in the habit of constantly remarking on the key conceptual detail that the tooth fairy is not real. Nevertheless, a definition that fails to note this misses, paradoxically enough, ‘the real thing.’ Just as Major Monarch doesn’t quite look like ‘the real thing’ he is, sometimes a word used in everyday speech doesn’t quite capture the thing it really is.

Jeff Sherwood is a US Assistant Editor for Oxford Dictionaries. Read more about Henry James with Oxford World’s Classics. A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Montage of Henry James Oxford World’s Classics editions.

The post Henry James, or, on the business of being a thing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWord histories: conscious uncouplingHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?Henry Bradley on spelling reform

Related StoriesWord histories: conscious uncouplingHow do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ?Henry Bradley on spelling reform

Reinventing rites of passage in contemporary America

“It has often been said that one of the characteristics of the modern world is the disappearance of any meaningful rites of initiation.”

Mircea Eliade made this comment in his 1956 Haskell Lectures on the History of Religions at the University of Chicago (subsequently published as Rites and Symbols of Initiation). The qualifier meaningful in Eliade’s statement is significant, because something so fundamental to human societies (across cultures and over time) as rites of initiation do not simply melt into air, modernity notwithstanding.

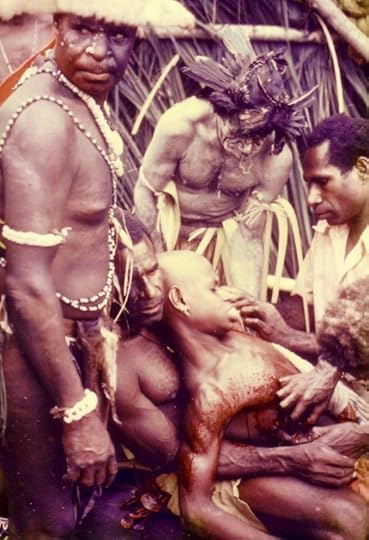

Initiation ritual along the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea in 1975. Photo by Franz Luthi. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Contemporary ritual studies luminary, Ronald Grimes, highlights a unique and contradictory aspect of Western industrialized societies when it comes to initiation, one perhaps implied by Eliade. “Initiation goes on all the time,” Grimes writes in his book, Deeply Into the Bone: Re-inventing Rites of Passage. But we lack “explicit or compelling initiation ceremonies.”

The centrifugal forces of modernity have rendered the initiation that does take place in Western industrial societies more diffuse, haphazard, individualized, and even sometimes only imaginary. In the face of this, some communities are attempting to create or re-create rites of passage that are mindful and intentional.

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, less than a decade after Eliade’s lectures, the leaders of the Roman Catholic Church meeting at the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) called for a restoration of the “catechumenate”—the ancient process for ritually initiating adults. As I noted yesterday, this culminated in the publication in 1972 of Ordo Initiationis Christianae Adultorum, subsequently translated into English in 1988 as Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults.

In his work on re-inventing rites of passage, Grimes does not mention the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA), but he could have. In “returning to the sources” in the ancient church for an earlier model of initiation (what French theologians call ressourcement), the creators of the contemporary RCIA engaged in the very process of reinvention that Grimes calls for.

Anointing with Holy Oil. Photo by John Ragai. CC 2.0 via Flickr.

When fully implemented, the RCIA process takes those considering becoming Catholic on a journey through four distinct periods of formation which are demarcated by three ritual transitions.

Period 1: Evangelization and Precatechumenate

The opening stage of the RCIA process is intended to introduce individuals to the Catholic faith and to answer questions about it. Also during this period individuals are paired with sponsors, members of the church who will accompany the individual on their journal toward initiation.

Ritual Transition 1: Rite of Acceptance into the Order of Catechumens

Those who decide to continue in the RCIA process go through this first of three major ritual transitions. During a liturgy individuals are asked to affirm their acceptance of the Gospel of Christ and the assembly is asked to affirm their support of the candidates. The passage to the status of “catechumen” is then ritually enacted by the priest, catechist, or sponsor tracing the sign of the cross on the forehead (and often also the ears, eyes, lips, chest, shoulders, hands, and feet) of the candidate.

Period 2: Catechumenate

This is the main time of formation for those seeking initiation. The purpose of this period is to give catechumens “suitable pastoral formation and guidance, aimed at training them in the Christian life” through catechesis, community, liturgy, and service (RCIA, no. 75). Once catechumens are ready to receive the sacraments of initiation they must publicly declare this and go through a ritual transition to become one of the “elect.”

Ritual Transition 2: Rite of Election

Typically held the first Sunday of Lent and presided over by the bishop, this ritual brings together individuals in the RCIA process from the entire diocese so that for the first time the candidates are able to see and experience the church writ large. In this rite, God “elects” those catechumens who are deemed ready to take part in the sacraments of initiation and who affirm their desire to do so. The candidates’ names are enrolled in the diocesan “Book of the Elect” which is countersigned by the bishop who declares them ready to begin their final period of preparation before initiation.

Period 3: Purification and Enlightenment

This period focuses on spiritual preparation for the rites of initiation and coincides with the 40 days preceding Easter, known as the season of Lent. As part of their spiritual cleansing, the elect undergo three public “scrutinies” which typically involve prayer over the elect and an “exorcism” enacted by a laying on of hands by the presider. The elect are also ritually presented the text of the Nicene Creed and Lord’s Prayer. At the conclusion of this period, the elect undergo the most significant ritual transition: the reception of the sacraments of initiation.

Ritual Transition 3: Reception of the Sacraments of Initiation

This moment of incorporation—literally becoming part of the body of the church—normatively and most often takes place during the Easter Vigil, what Augustine called “the mother of all holy vigils.” In and through this ritual, individuals receive the sacraments of initiation (baptism, confirmation, and eucharist) and in doing so become Catholic.

Period 4: Mystagogy

This is sometimes called the period of “post-baptismal catechesis” because it seeks to lead the newly initiated more deeply into reflection on the experience of the sacraments and membership in the church. It is a springboard from the RCIA community to the broader church community.

By the turn of the 21st century, more than 80% of American parishes were using some version of this RCIA process to initiate adults. Although it is not yet fully implemented in every parish, the RCIA is the officially recognized liturgical and catechetical process by which adults become Catholic today.

As a reinvented rite of passage, the RCIA process has been very successful at bringing individuals into the Catholic Church in a mindful, intentional, and compelling way. As I noted in my first OUPblog entry, it is also helping to shape the process of ritual initiation in other churches. I will suggest in my third and final entry that the RCIA, therefore, represents a bit of good news amid a lot of bad news for the Roman Catholic Church in the contemporary United States.

David Yamane teaches sociology at Wake Forest University and is author of Becoming Catholic: Finding Rome in the American Religious Landscape. He is currently exploring the phenomenon of armed citizenship in America as part of what has been called “Gun Culture 2.0″—a new group of individuals (including an increasing number of women) who have entered American gun culture through concealed carry and the shooting sports. He blogs about this at Gun Culture 2.0. Follow him on Twitter @gunculture2pt0.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Reinventing rites of passage in contemporary America appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInitiation into America’s original megachurchPreparing for INTA 2014, the first annual meeting in AsiaMoney matters

Related StoriesInitiation into America’s original megachurchPreparing for INTA 2014, the first annual meeting in AsiaMoney matters

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers