Oxford University Press's Blog, page 817

April 28, 2014

Felon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacy

Nearly six million Americans are prohibited from voting in the United States today due to felony convictions. Six states stand out: Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia. These six states disfranchise seven percent of the total adult population – compared to two and a half percent nationwide. African Americans are particularly affected in these states. In Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia more than one in five African Americans is disfranchised. The other three are not far behind. Not only do individuals lose voting rights when they are incarcerated, on probation, or paroled, a common practice in many states, but some or all ex-felons are barred from voting. All six of these states have non-automatic restoration processes that make it difficult or impossible to have one’s rights restored. Not coincidentally, all of these states maintained a system of racial slavery until the Civil War.

Voters at the Voting Booths. ca. 1945. NAACP Collection, The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship, Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At the other end of the spectrum are northeastern states, mostly those in New England, which put up few obstacles to voting by convicted individuals. Maine and Vermont are the only states in the nation that do not disfranchise anyone for a crime, even individuals who are incarcerated. Among the remaining 48 states, Massachusetts and New Hampshire disfranchise the smallest percentage of convicted individuals. Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania are also far below the national average.Generalizations about regional difference are complex should be made cautiously. Although the six states with the highest rates of disfranchisement are all in the South, six other states also impose life-long disfranchisement for some or all felons. Arizona and Nevada have relatively high rates of felon disfranchisement. Midwestern states, particularly Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan, have low rates of felon disfranchisement, as does North Dakota. Nonetheless, the Northeast and South stand in stark contrast.

Regional differences in felon disfranchisement today are the result of regionally divergent histories of slavery and criminal justice. New England states had outlawed slavery by 1800. Soon, they also stopped treating convicts like slaves, barring state-administered corporal punishment for criminal offenses in the first few decades of the nineteenth century. Instead, northeastern states embraced an ideology of criminality that emphasized rehabilitation. This attitude toward both slavery and punishment led many citizens and lawmakers in the northeast to oppose disfranchisement of convicts or at least curb the reach of this punishment. In the colonial era, Connecticut limited the courts that could deny convicts the vote. Maine’s 1819 constitutional convention rejected a proposal to disfranchise for crime. Vermont ended the practice in 1832. In other northeastern states proponents of such disfranchisement measures faced strong opposition. For example, Pennsylvania’s 1873 constitutional convention restricted felon disfranchisement to those convicted of election-related crimes; an effort to disfranchise convicts in Maryland in 1864 passed only after a long debate.

In contrast in the nineteenth-century South two groups were permanently cast out of full citizenship: African Americans and convicts. Although the enslavement of African Americans ended in 1865, “infamy” – the legal status of those convicted of serious crimes – was imposed on a growing number of the new black citizens. Accusations of prior crimes were used in the 1866 election as one of the first tools used to deny the vote to former slaves. In the 1870s, nearly every state in the former Confederacy (Texas being the exception) modified its laws to disfranchise for petty theft, a move celebrated by white leaders as a step toward disfranchising African Americans.

The legacy of slavery and segregation in the South is important to this story but so is the different regional trajectory of criminal justice. All southern states except South Carolina and Georgia (states today that still have among the lowest rates of disfranchisement in the South) enacted laws disfranchising for crime between 1812 and 1838, and there is little evidence of dissent or debate over this punishment anywhere in the region. Furthermore, southern states rejected the concept of criminal rehabilitation and focused instead on punishment. After the Civil War “convict lease” systems replicated in many ways the system of slavery for those who fell into it, creating a class of mostly-black individuals who were subject to physical punishment, public abuse, and humiliation, and denied voting rights.

In the past, as is also true today, individuals with criminal convictions fought long battles to regain their voting rights. Far from being a population that is uninterested in politics, individuals barred from voting have challenged obstacles to re-enfranchisement and overcome tremendous hurdles to have their voting rights restored. Consider the case of Jefferson Ratliff, an African American farmer living in Anson County, North Carolina, who in 1887 paid the court an astounding $14 to have his citizenship rights restored, ten years after his conviction for larceny (including three years’ incarceration) for stealing a hog. In Giles County, Tennessee in 1888 a man named Henry Murray paid $2.70 in court costs in an unsuccessful effort to have his voting rights restored. In other cases, poor and illiterate individual petitioners facing a complicated legal process sought help from friends and neighbors. In Georgia, Lewis Price petitioned Governor William Y. Atkinson in 1895 for a pardon so that he could vote. He explained, “I am a poor ignorant negro and I have no money to pay to the lawyers to work for me. So I have to depend on my friends to do all of my writing.”

The historical record shows that state and local governments have consistently failed, throughout the nation’s history, to enforce these laws in a fair and uniform way. Coordinating voter registration lists with criminal court records and pardon records — difficult in today’s world of information technology — was nearly impossible in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. People who should have been able to vote were often denied the vote due to false allegations of disfranchising offenses; convictions were secured through suspect judicial processes prior to an election for partisan ends; and people who should have been disfranchised often voted. Sometimes these appear to have been honest mistakes made by officials charged with merging complicated statutory and constitutional requirements with voter registration data and court records. In many cases though, other agendas—partisan, racial, personal—seem to have been at work. In short, felon disfranchisement laws have long been subject to error and abuse.

Race both rationalized and motivated laws imposing lifelong disfranchisement for certain criminal acts in the post-Civil War period. Since then a variety of factors have led to the persistent sense, particularly in southern states, that individuals with prior criminal convictions are marked with a disgrace and contamination that is incompatible with full citizenship. Felon disfranchisement today preserves slavery’s racial legacy by producing a class of individuals who are excluded from suffrage, disproportionately impoverished, members of racial and ethnic minorities, and often subject to labor for below-market wages. In these six southern states, the ballot box is just as out of reach for former convicts as it was for enslaved African Americans two centuries ago.

Dr. Pippa Holloway is the author of Living in Infamy: Felon Disfranchisement and the History of American Citizenship, published Oxford University Press in December 2012. She is Professor of History at Middle Tennessee State University. Contemporary data comes from Christopher Uggen, Sara Shannon, Jeff Manza, “State-Level Estimates of Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States, 2010.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Felon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDiscussing proprietary estoppel: promises and principlesASIL/ILA 2014 retrospectiveOxford University Press during World War I

Related StoriesDiscussing proprietary estoppel: promises and principlesASIL/ILA 2014 retrospectiveOxford University Press during World War I

Getting to know Sir Philip Sidney

What does Sir Philip Sidney’s correspondence teach us about the man and his world? You have to realise what letters were, what they were like, and what they were for.

Some of them were like our e-mails: brief and to the point, sent for a practical reason. They were usually carried and delivered by a person known to the sender; so sometimes they are an introduction to the bearer, sometimes it’s the bearer who will tell the really sensitive news (frustrating for us!). These can tell us something about people and their specific interactions.

Other letters are long and more like a personal form of news media — meant to inform the recipient (often Sidney himself) about what is happening in the world of politics (with which religion is often mixed; it’s a time of religious wars). These are precious as sources for our knowledge of what happened. Take the example of the Turkish conquest of Tunis in the summer of 1574. One of Sidney’s correspondents, Wolfgang Zündelin, was a professional political observer in Venice, where all the news in the Mediterranean went first. So there is a series of letters from him recounting this huge amphibious victory by the Ottoman Turks, led by a converted Italian and a cruel Albanian, over the city of Tunis and its port La Goletta, defended by a mixed force of Spaniards and Italians, with a wealth of detail.

Most of us were taught about Sidney as the author of brilliant if rueful love-sonnets and of a long prose romance (ancestor of the novel) called the Arcadia. It is intriguing to meet the young man in these letters, in which poetry is never discussed and in which politics and governance are the paramount topics. We tend to forget how young he was. At 17 he went abroad and lived through a massacre in Paris; from there he travelled through Europe for nearly three years, studying in Padua, being painted by Veronese in Venice, and meeting princes from the King of France to Emperor Maximilian in Vienna.

At 22 he was chosen to head a ceremonial embassy (combined with confidential intelligence-gathering) to the new Emperor Rudolf II, which he carried off with enormous aplomb. The Emperor himself, brought up in Spain and very stiff, was not terribly impressed, but everyone else was.

Most of us know that Sidney was eventually killed in the Netherlands by a Spanish musket-ball at the age of 31; here we see him trying to manage the key port of Flushing (ceded to the English in return for their help to the Dutch against Spain), frustrated by lack of funds and support from England, trying not to despair of the Queen and hoping not only to deal the Spaniards a blow but to do some glorious deed in the process.

At the end there are three urgent lines, a scrawl really, now almost illegible in the National Archives, of a young man dying of gangrene and scribbling in bed a note calling for a German doctor he knows. Heartbreaking.

We know so much about him: more than about almost any other Englishman of his time. And yet there is still much we have to guess at. Nowhere does he state his thoughts, for instance, about religion, such a burning subject in his age. Nor does he write about literature, except to ask a friend to go on singing his songs and to tell his brother he will soon receive his, Philip’s, “toyful book”. There are no letters (that we know of) to his sister Mary, the Countess of Pembroke, herself a major poet; none to his two best friends Fulke Greville and Edward Dyer.

He was serious and charming, intense and cheerful, dutiful and ambitious. He wanted to do something for his country. Above all, he was fascinated by the idea of governance, not a word we use a lot. But for him it was everywhere. How do you govern yourself, in the face of those rebellious subjects, your passions? How do you govern a family? How do you govern soldiers, always underpaid and apt to plunder the countryside? How do you govern a country, help its allies, keep its enemies at bay? They are subjects not altogether irrelevant today; and reading his correspondence gives us an idea of the way they were viewed by a brilliant young man a mere four centuries ago.

But of course, this is not enough, in Philip Sidney’s case. We read about Sidney because we read Sidney. This astonishing young man mentioned above, in eight short years, wrote (a) the first great treatise of literary criticism in English, A Defence of Poesy (also known as An Apology for Poetry); (b) the first major sonnet-sequence in English, Astrophil and Stella; and (c) the first (then-)modern prose romance in English, Arcadia – which exists in two versions, the “Old” Arcadia, complete, and his unfinished revision of it, the “New” Arcadia.

Roger Kuin is Professor of English Literature (emeritus) at York University, Toronto, Canada. He is the editor of The Correspondence of Sir Philip Sidney (now available on Oxford Scholarly Editions Online). He has written extensively about Sidney and about Anglo-Continental relations in the later sixteenth century; lately he has been working on heraldic funerals, beginning with the very grand one of Sidney himself. He has a blog, Old Men Explore, and can be found on Facebook.

A range of Sir Philip Sidney editions available to subscribers of Oxford Scholarly Editions Online. Oxford’s scholarly editions provide trustworthy, annotated texts of writing worth reading. Overseen by a prestigious editorial board, Oxford Scholarly Editions Online makes these editions available online for the first time.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Sir Philip Sidney, the Bolton portrait. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Getting to know Sir Philip Sidney appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOxford University Press during World War IHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!Entitling early modern women writers

Related StoriesOxford University Press during World War IHappy 450th birthday William Shakespeare!Entitling early modern women writers

ASIL/ILA 2014 retrospective

In early April, the American Society of International Law and the International Law Association held a joint conference around the theme “The Effectiveness of International Law.” We may not have been able to do everything on our wishlist, but there are plenty of round-ups to catch up on all the news and events: ASIL Cables posted throughout the conference; the International Law Prof Blog wrote a piece on three female judges of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), who were honored at the conference; IntLawGrrls posted a group photo of all members attending this year’s conference; and DipLawMatic Dialogues blogged from a librarians perspective on the proceedings of ILA-ASIL, including a piece on the Clive Parry Consolidated Treaty Series.

We were delighted to see so many friendly faces. Below is a slideshow featuring some of the authors, editors, and contributors who stopped by to say hello during the week.

Sean Murphy

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Co-author of Litigating War

Cesare Romano

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Editor of the Oxford Handbook of International Adjudication

Ruti Teitel

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of Globalizing Transitional Justice

Anne Peters

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Co-Editor of the Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law

Ganesh Sitaraman

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of The Counterinsurgent's Constitution

Ben Saul

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Co-author of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Salvatore Zappala

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Editor of Journal of International Criminal Justice

Mike Newton

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of Proportionality in International Law

David Caron

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Co-author of the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules 2nd edition with OUP's very own Merel Alstein

Jean d'Aspremont

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of Formalism and the Sources of International Law

Pieter Jan Kuijper

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Co-author of the Law of EU External Relations

Duncan Hollis

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of the Oxford Guide to Treaties

Won Kidane

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Co-author of Litigating War: Mass Civil Injury and the Eritrea-Ethiopia Claims Commission

Guy S. Goodwin Gill

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Founding editor of International Journal of Refugee Law, celebrates 25 years since the journal first launched

Martins Paparinskis

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of the International Minimum Standard and Fair and Equitable Treatment, stops by the booth between his talks

Dieter Fleck

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Editor of the Handbook of International Humanitarian Law 3rd edition

Yuval Shany

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of Assessing the Effectiveness of International Courts

Antonios Tzanakopoulos

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of Disobeying the Security Council: Countermeasures against Wrongful Sanctions, and OUP's very own John Louth

Jane McAdam

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of Climate Change, Forced Migration, and International Law as well as editor of International Journal of Refugee Law

Kai Ambos

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Author of Treatise on International Criminal Law volumes I and II

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All photos courtesy of Oxford University Press staff./em>

The post ASIL/ILA 2014 retrospective appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesChallenges to the effectiveness of international lawPreparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meetingJus post bellum and the ethics of peace

Related StoriesChallenges to the effectiveness of international lawPreparing for the 2014 ASIL/ILA annual meetingJus post bellum and the ethics of peace

Discussing proprietary estoppel: promises and principles

What is the legal strength of a spoken promise? This thorny terrain is one of the major concerns of proprietary estoppel, a branch of land law that governs the rights to land without valid methods of transfer, such as a trust or a will. Ben MacFarlane, Professor of Law at University College London, discusses the different strands and principles within proprietary estoppel, and identifies interesting areas of development in this practice.

On ‘The Law of Proprietary Estoppel’

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the structure of the Law of Proprietary Estoppel

Click here to view the embedded video.

What are the different types of estoppel?

Click here to view the embedded video.

On Walton v Walton, and the law of proprietary estoppel

Click here to view the embedded video.

How proprietary estoppel relates to trust law

Click here to view the embedded video.

What are the new developments in proprietary estoppel?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Ben McFarlane is a Professor of Law, at University College London. He has taught in Oxford since 1999 and has published widely on proprietary estoppel, as well as addressing legal practitioners on the subject. He is the author of The Law of Proprietary Estoppel.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Discussing proprietary estoppel: promises and principles appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCan metaphors make better laws?The viability of Transcendence: the science behind the filmWhy are money market funds safer than the Bitcoin?

Related StoriesCan metaphors make better laws?The viability of Transcendence: the science behind the filmWhy are money market funds safer than the Bitcoin?

April 27, 2014

The viability of Transcendence: the science behind the film

In the trailer of Transcendence, an authoritative professor embodied by Johnny Depp says that “the path to building superintelligence requires us to unlock the most fundamental secrets of the universe.” It’s difficult to wrap our minds around the possibility of artificial intelligence and how it will affect society. Nick Bostrom, a scientist and philosopher and the author of the forthcoming Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, discusses the science and reality behind the future of machine intelligence in the following video series.

Could you upload Johnny Depp’s brain?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How imminent is machine intelligence?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Would you have a warning before artificial intelligence?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How could you get a machine intelligence?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Nick Bostrom is Professor in the Faculty of Philosophy at Oxford University and founding Director of the Future of Humanity Institute and of the Program on the Impacts of Future Technology within the Oxford Martin School. He is the author of some 200 publications, including Anthropic Bias, Global Catastrophic Risks, and Human Enhancement. His next book, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, will be published this summer in the UK and this fall in the US. He previously taught at Yale, and he was a Postdoctoral Fellow of the British Academy. Bostrom has a background in physics, computational neuroscience, and mathematical logic as well as philosophy.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The viability of Transcendence: the science behind the film appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInferring the unconfirmed: the no alternatives argument18 facts you never knew about cheeseFive facts on canonization for saint watchers and atheists who believe in miracles

Related StoriesInferring the unconfirmed: the no alternatives argument18 facts you never knew about cheeseFive facts on canonization for saint watchers and atheists who believe in miracles

Emerging adult Catholic types [infographic]

In their National Study of Youth and Religion, Christian Smith, Kyle Longest, Jonathan Hill, and Kari Christoffersen studied a sample of young people for five years, starting when they were 13 to 17 years old and completing the study when they were 18 to 23, a stage called “emerging adulthood.” As illustrated in this infographic, part of the focus was on Catholic emerging adults. As illustrated, the authors found discouraging numbers for young Catholics staying in the faith as they grew up.

Download a jpg or pdf of the infographic.

Christian Smith is William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Sociology at the University of Notre Dame, Director of the Center for the Study of Religion and Society, Director of the Notre Dame Center for Social Research, Principal Investigator of the National Study of Youth and Religion, and Principal Investigator of the Science of Generosity Initiative. Kyle Longest is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Furman University. Jonathan Hill is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Calvin College. Kari Christoffersen is a PhD candidate at the University of Notre Dame. They are co-authors of Young Catholic America: Emerging Adults In, Out of, and Gone from the Church.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Emerging adult Catholic types [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive facts on canonization for saint watchers and atheists who believe in miraclesReinventing rites of passage in contemporary AmericaInferring the unconfirmed: the no alternatives argument

Related StoriesFive facts on canonization for saint watchers and atheists who believe in miraclesReinventing rites of passage in contemporary AmericaInferring the unconfirmed: the no alternatives argument

Inferring the unconfirmed: the no alternatives argument

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” Thus Arthur Conan Doyle has Sherlock Holmes describe a crucial part of his method of solving detective cases. Sherlock Holmes often takes pride in adhering to principles of scientific reasoning. Whether or not this particular element of his analysis can be called scientific is not straightforward to decide, however. Do scientists use ‘no alternatives arguments’ of the kind described above? Is it justified to infer a theory’s truth from the observation that no other acceptable theory is known? Can this be done even when empirical confirmation of the theory in question is sketchy or entirely absent?

The Edinburgh Statue of Sherlock Holmes. Photo by Siddharth Krish. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The canonical understanding of scientific reasoning insists that theory confirmation be based exclusively on empirical data predicted by the theory in question. From that point of view, Holmes’ method may at best play the role of a side show; the real work of theory evaluation is done by comparing the theory’s predictions with empirical data.

Actual science often tells a different story. Scientific disciplines like palaeontology or archaeology aim at describing historic events that have left only scarce traces in today’s world. Empirical testing of those theories always remains fragmentary. Under such conditions, assessing a theory’s scientific status crucially relies on the question of whether or not convincing alternative theories have been found.

Just recently, this kind of reasoning scored a striking success in theoretical physics when the Higgs particle was discovered at CERN. Besides confirming the Higgs model itself, the Higgs discovery also vindicated the judgemental prowess of theoretical physicists who were fairly sure about the existence of the Higgs particle already since the mid-1980s. Their assessment had been based on a clear-cut no alternatives argument: there seemed to be no alternative to the Higgs model that could render particle physics consistent.

Similarly, string theory is one of the most influential theories in contemporary physics, even in the absence of favorable empirical evidence and the ability to generate specific predictions. Critics argue that for these reasons, trust in string theory is unjustified, but defenders deploy the no alternatives argument: since the physics community devoted considerable efforts to developing alternatives to string theory, the failure of these attempts and the absence of similarly unified and worked-out competitors provide a strong argument in favor of string theory.

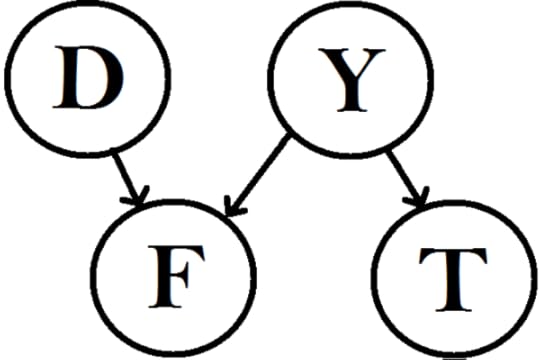

These examples show that the no alternatives argument is in fact used in science. But does it constitute a legitimate way of reasoning? In our work, we aim at identifying the structural basis for the no alternatives argument. We do so by constructing a formal model of the argument with the help of so-called Bayesian nets. That is, the argument is analyzed as a case of reasoning under uncertainty about whether a scientific theory H (e.g. string theory) is right or wrong.

A Bayes nets that captures the inferential relations between the relevant propositions in the no alternatives argument. D=complexity of the problem, F=failure to find an alternative, Y=number of alternatives, T=H is the right theory.

We argue that the failure of finding a viable alternative to theory H, in spite of many attempts by clever scientists, lowers our expectations on the number of existing serious alternatives to H. This provides in turn an argument that H is indeed the right theory. In total, the probability that H is right is increased by the failure to find an alternative, demonstrating that the inference behind the no alternatives argument is valid in principle.

There is an important caveat, however. Based on the no alternatives argument alone, we cannot say how much the probability of the theory in question is raised. It may be substantial, but it may only be a tiny little bit. In that case, the confirmatory force of the no alternatives argument may be negligible.

The no alternatives argument thus is a fascinating mode of reasoning that contains a valid core. However, determining the strength of the argument requires going beyond the mere observation that no alternatives have been found. This matter is highly context-sensitive and may lead to different answers for string theory, paleontology and detective stories.

Richard Dawid, Stephan Hartmann, and Jan Sprenger are the authors of “The No Alternatives Argument” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. Richard Dawid is lecturer (Dozent) and researcher at the University of Vienna. Stephan Hartmann is Alexander von Humboldt Professor at the LMU Munich. Jan Sprenger is Assistant Professor at Tilburg University. Their work focuses on the application of probabilistic methods within the philosophy of science.

For over fifty years The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science has published the best international work in the philosophy of science under a distinguished list of editors including A. C. Crombie, Mary Hesse, Imre Lakatos, D. H. Mellor, David Papineau, James Ladyman, and Alexander Bird. One of the leading international journals in the field, it publishes outstanding new work on a variety of traditional and cutting edge issues, such as the metaphysics of science and the applicability of mathematics to physics, as well as foundational issues in the life sciences, the physical sciences, and the social sciences.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Inferring the unconfirmed: the no alternatives argument appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchangeNew sodium intake research and the response of health organizationsVaccines: thoughts in spring

Related Stories‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchangeNew sodium intake research and the response of health organizationsVaccines: thoughts in spring

April 26, 2014

Oxford University Press during World War I

The very settled life of Oxford University Press was turned upside down at the outbreak of the First World War; 356 of the approximately 700 men that worked for the Press were conscribed, the majority in the first few months. The reduction of half of the workforce and the ever-present uncertainty of the return of friends and colleagues must have made the Press a very difficult place to work.

At the time, the man in charge of the Press was the Secretary Charles Cannan, and the Printer, responsible for the printing house, was Horace Hart (best remembered for Hart’s Rules). The steady dissolution of Hart’s workforce, made up of generations of men he had known for years from the close-knit community of Jericho, was thought to be too much for the Printer. He retired and sadly took his own life in 1916. Hart was succeeded by Frederick Hall, who served as Printer from 1915 to 1925.

Women filled many of the gaps in the workforce, both on the print floor and in the offices. Previously, women could only be found in the bindery, and this change must have been revolutionary for all those who worked at the Press, men and women alike.

The OUP Oxford War Memorial

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

On Active Service, War Work At Home 1914-1919

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

God Save the King sign erected at OUP Oxford

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Flower and Vegetable Show in the Oxford quad

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Printer Frederick Hall

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Printer Horace Hart

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Secretary Charles Cannan

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

OUP Oxford quadrangle, early 20th century

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

During the war, publishing continued at OUP, including Oxford Pamphlets, Shakespeare’s England (produced to mark 300 years since Shakespeare’s death in 1916), and also some secret document printing on the behalf of British Naval intelligence (much of which still remains a mystery). The Press also took on responsibility for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography during this time, which was bequeathed to it from another publishing house and proved to be a challenging task in bringing it up to the academic standards expected from OUP.

The remaining staff endeavoured to keep up a sense of community and morale; they started an annual Flower and Vegetable Show with produce they grew on the allotments allocated on the nearby Port Meadow. The growing of home produce was particularly essential to Britain after the German submarine blockades, which caused huge food shortages.

A number of the men from OUP were positioned on the front line during their service, and many others ended up in Greece, Egypt, and as far flung as Russia. For these men, the majority of whom had never been outside of Oxford, the experiences that awaited them abroad must have been overwhelming, and, for many, devastating. A total of 45 men were lost to the war; 44 on active service and one who died after his return from injuries sustained in battle. In 1920, the Press produced a book, On Active Service, War Work At Home 1914-1919 recording the events at the Press during the war and also giving the service record of all the men who were conscribed. A War Memorial to commemorate the soldiers who had died was also erected. The memorial still stands in the OUP Oxford quad today, and is still the centre for the Press’ own Remembrance Day each year.

Lizzie Shannon-Little is Community Manager at Oxford University Press. Martin Maw is an Archivist at Oxford University Press. The Archive Department also manages the Press Museum at OUP in Oxford. Watch the first in a series of videos with Martin, examining how life at the Press irrevocably changed between 1914-1919.

In the centenary of World War I, Oxford University Press has gathered together resources to offer depth, detail, perspective, and insight. There are specially commissioned contributions from historians and writers, free resources from OUP’s world-class research projects, and exclusive archival materials. Visit the First World War Centenary Hub each month for fresh updates.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oxford University Press during World War I appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA publisher before wartimeNew perspectives on the history of publishingSoldiers’ experiences of World War I in photographs

Related StoriesA publisher before wartimeNew perspectives on the history of publishingSoldiers’ experiences of World War I in photographs

18 facts you never knew about cheese

Have you often lain awake at night, wishing that you knew more about cheese? Fear not! Your prayers have been answered; below you will find 18 of the most delicious cheese facts, all taken from Michael Tunick’s recent book The Science of Cheese. Prepare to be the envy of everyone at your next dinner party – just try not to be too “cheesy”. Bon Appétit!

The world’s most expensive cheese comes from a Swedish moose farm and the cheese sells for £300 a pound.

You can’t make cheese entirely from human milk since it won’t coagulate properly.

The largest cheese ever made was a Cheddar weighing 56,850 pounds, in 1989.

97% of British people are ‘Lactose Persistent’ and are the most lactose tolerant population in the world.

Genuine Flor de Guia cheese must be made in the Canary Islands by women, otherwise it won’t be considered the genuine article.

The expression “cheesy” used to mean first-rate, but sarcastic use of the word has caused it to mean the opposite.

The bacteria used for smear-ripened cheeses are closely related to the bacteria that generates sweaty feet odour.

Cheese as we know it today was (accidentally) discovered over 8,000 years ago when milk separated into curds and whey.

Edam was used as cannonballs (and killed two soldiers) in a battle between Montevideo and Buenos Aires in 1841.

An odour found in tomcat urine is considered desirable in Cheddar.

Each American adult consumes an average of 33 pounds of cheese each year.

Descriptions of the defects in the eyes of Swiss-type cheeses include the terms “blowhole” and “frogmouth”.

There are over 1,265,000 dairy cows in the US state of Wisconsin alone.

A northern Italian bank uses Parmesan as loan collateral.

Sardinia’s Cazu Marzu, which means ‘rotten cheese’, is safe to eat only if it contains live maggots.

Cheese consumption in the United Kingdom is at a measly 24.0 pounds per capita.

This cheese consumption isn’t even close to Greece who lead the way with a whopping 68.4 pounds per capita.

Dmitri Mendeleev was a consultant on artisanal cheese production while he was also inventing the periodic table of the elements.

All of these cheese facts are taken from The Science of Cheese. The Science of Cheese is an engaging tour of the science and history of cheese, and the only book to discuss the actual chemistry, biology, and physics of cheese making. Author Michael Tunick is a research chemist with the Dairy and Functional Foods Research Unit of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Weichkaese Soft Cheese. Photo by Eva K. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 18 facts you never knew about cheese appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive facts on canonization for saint watchers and atheists who believe in miraclesArbor Day: an ecosystem perspectiveWhat is ‘lean psychiatry’?

Related StoriesFive facts on canonization for saint watchers and atheists who believe in miraclesArbor Day: an ecosystem perspectiveWhat is ‘lean psychiatry’?

Five facts on canonization for saint watchers and atheists who believe in miracles

On 27 April 2014, Pope Francis will canonize two of his predecessors, John XXIII and John Paul II. As the rules require, devotees have long been preparing for their recognition as saints, gathering biographical materials and evidence of miracles. This act brings the number of canonizations in his papacy to ten.

But on 3 April, Francis canonized three lesser known Blesseds, two of whom were French-born Canadians, the other a missionary to Brazil born in the Canary Islands. In the case of these three saints and John XXIII, Francis relied on an equivalent canonization without miracles.

The new round of saint making invites us to consider the role of miracles in the canonization process and ask if it is changing in our time. Below are five things you may not know about the canonization process.

(1) Miracles are used as evidence in the canonization process

Saint-making was once a local procedure, overseen by bishops. During the Counter Reformation, the church codified the analysis of causes through a special committee, the Sacra Rituum Congregatione (SRC). Launched in 1588, these rules were clarified in the 1730s by Prospero Lambertini (1675-1758), who became Pope Benedict XIV in 1740.

Three stages are necessary: first, veneration following an authoritative biography to establish a life of “heroic virtue”; second, beatification following miracles; finally, canonization following more miracles.

In the Catholic tradition, only God works miracles. Therefore, miracles received after appeals for intercession are taken as evidence that the candidates for sainthood are with God. Elements of due, canonical process, miracles also illustrate how the faithful experience illness.

Exemptions from miracles were allowed for rare individuals, especially martyrs—whose deaths were sufficient evidence of sanctity. Nevertheless, the Vatican archives holds many records of miracles ascribed to martyrs, such as the English and Welsh martyrs, Andrew Bobola, John de Brito, and the Jesuit saints of Canada.

The Miracle of Saint Donatus. Amiens, Museum of Picardy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(2) The majority of miracles over the last four centuries are healings from physical illness, for which scientific testimony is required.

In my study of 1,400 canonization miracles over four centuries, more than 95 per cent were healings from physical illness. The proportion of “medical miracles” increased to 99 per cent in the twentieth century.

Most investigations required testimony of physicians, some of whom were nonbelievers: treating doctors, expert consultants, and occasionally medical family members. In addition, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints (successor of the SRC) relies on a committee of distinguished physicians, the Consulta Medica, to evaluate the claims of postulants.

Most investigations seek evidence not only that the patient prayed, but also that she appealed to physicians who used up-to-date diagnostic and treatment strategies.

(3) Diseases that are healed miraculously change through time, reflect changes in science, epidemiology, and medical therapeutics.

The diseases healed by divine intercession reflect the major concerns of any period: fevers in the early period; tuberculosis in the nineteenth century; cancer, neurological, and heart diseases in our time.

Diseases healed by intercession often match characteristics of the new saint. For example, the first miracle ascribed to John Paul II was a French nun’s recovery from Parkinson’s disease. In the cause of Kateri Tekakwitha, whose face had been disfigured by smallpox, the final miracle was the survival of an American boy with native ancestry who suffered flesh-eating disease of his face.

The committee of expert physicians examines every miracle submitted for consideration, assessing the diagnosis, the quality of treatments, and plausible, scientific explanations for the cure.

If the diagnosis was unreliable, or the treatment short of contemporary standards, or the cure scientifically explicable, then the healing may be recognized as an act of grace, but not a miracle.

(4) Saint-making and recognition of miracles has been streamlined.

Many miracles were necessary for canonization in the past. Seventeenth-century causes saw an average of fifteen to twenty miracles. Benedict XIV emphasized quality and scientific scrutiny over quantity. Thereafter, the average number of miracles for each cause declined to approximately four, although some boasted many more.

For much of the twentieth century, a cause could not be considered until at least fifty years had elapsed following the death of the candidate. Also, the would-be saint should have interceded for two miracles before beatification, and another two for canonization.

During the papacy of John Paul II, the process was streamlined. The wait time was reduced to five years after death, and the miracle requirement, to only one for each of beatification and canonization.

(5) The need for miracles in the canonization process may be on the wane.

Gathering miracle evidence is expensive and time-consuming. Emerging nations rarely have elegant technologies, such as CT and MRI machines, demanded for exacting proof of diagnosis and healing. Finding witnesses and documenting illnesses long past is difficult.

Some churchmen worry that the emphasis on miracles and up-to-date medicine poses an unfair and unnecessary hurdle for people of developing nations who should be entitled to venerate exemplary lives of local champions. In causes from 1588 to 1999, only three hailed from Africa: all beatifications by John Paul II on the basis one medical miracle each; one of these three, Sudanese nun Josephine Bakhita (d. 1947), was canonized in 2000.

Similarly, some clerics are concerned that the emphasis on miracles skews the process away from its main mission: to celebrate inspirational, human lives. Miracles sensationalize a process intended to enhance the accessibility of faith in daily life.

They also argue that emphasizing miracles downplays the intrinsic merits of prayer. Most people who pray do not receive miracles. Nevertheless, prayer provides consolation, comfort, insight, and strength.

With his first canonizations, Pope Francis is bucking tradition in a manner consistent with his focus on person-centered simplicity. His April 2014 decision to canonize four saints without miracles is technically within “the rules.” But it bypasses the strict, centuries-old procedures of miracles in order to celebrate their intellectual lives, as well as their spirituality, by drawing attention to their contributions as educators and scholars for the disadvantaged.

Miracles notwithstanding, saint-making is and has always been a product of politics and diplomacy between the Vatican and flocks of the faithful.

Jacalyn Duffin is Professor in the Hannah Chair of the History of Medicine at Queen’s University in Kingston, where she has taught in medicine, philosophy, history, and law for more than twenty years. She has served as President of both the American Association for the History of Medicine and the Canadian Society for the History of Medicine. The author of seven other books and many research articles, she holds a number of awards and honours for research, writing, service, and teaching. She is the author of Medical Miracles; Doctors, Saints, and Healing, 1588-1999 and Medical Saints: Cosmas and Damian in a Postmodern World.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five facts on canonization for saint watchers and atheists who believe in miracles appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEaster rites of initiation bring good news for American CatholicsReinventing rites of passage in contemporary AmericaInitiation into America’s original megachurch

Related StoriesEaster rites of initiation bring good news for American CatholicsReinventing rites of passage in contemporary AmericaInitiation into America’s original megachurch

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers