Oxford University Press's Blog, page 818

April 25, 2014

‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchange

Silence, interrogation, confession, chronology, and stories. The Oral History Review (OHR) Volume 41, Issue 1 is now online and coming to mailboxes soon, and along with it Alexander Freund’s article, “Confessing Animals”: Toward a Longue Durée History of the Oral History Interview.” OHR Editorial Board Member Erin Jessee spoke with the University of Winnipeg professor over his novel approach to the oral history interview. Below is a small excerpt from their conversation, with more to come soon.

Erin Jessee: I found your article very provocative (in the best possible way) and am eager to be a part of this dialogue. Perhaps an appropriate starting point for this email exchange would be for you to tell me about the story behind this article.

* * * * *

Alexander Freund: You are right: In the case of this article in particular, it makes sense to start with its genesis.

Ever since I conducted my first oral history interview in 1993, I have been surprised at how forthcoming many people are in telling their stories, including intimate details and “family secrets.” Originally I thought this was the result of my interviewing skills, but I also soon noticed some specific interviewing dynamics that I have found to be increasingly troubling. Silence was one of these dynamics. As interviewers, we remain silent to give our narrators space to reflect, reminisce, recall, and re-organize their memories. But silence makes people uncomfortable and they try to fill it with words. Even though I always told my interviewees to expect silences and not be alarmed by them, there were several instances when people told me information they had not planned on disclosing.

Sometime after 2000, I began to notice larger social phenomena in Canada and the United States that seemed to be shaped by similar dynamics. Storytelling, for example, became a big hype in all kinds of fields, from arts to therapy to business management. (Google ‘storytelling’ and you will be surprised by what you find.) From personal experience in participatory educational programs and documentaries, I saw that many of the group activities were intended to “liberate” participants from anonymity and social restrictions.

A few years ago, coincidence led me to Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality, Vol. 1. As soon as I hit the chapter “Scientia Sexualis,” all of my thoughts and concerns about interviewing and the storytelling craze of late came together and made sense. It was a real “Aha!” moment! I think every oral historian should read this short passage. I would be surprised if anyone with just a little bit of interviewing experience did not see the “interviewer” in Foucault’s description of the confessor-confessant relationship.

‘Storytelling’ by Jim Pennucci. CC BY 2.0 via pennuja Flickr.

As I write in the article, this is only the beginning of an exploration that our field needs to undertake as a whole. The article raises more questions than it can answer. The question that currently intrigues me the most is the rise of public confession since the end of the Cold War and the rise of the Internet. There seems to be an insatiable desire, not just in the West and not just among the young, to share one’s most intimate experiences and feelings with the world. Much of this is driven by the digital technology and media industries that profit from this new demand for public confession.

But why is it important for oral historians to critically examine and understand this culture?

First, much of this culture draws on the generic term “storytelling” to somehow give it legitimacy and credibility. Oral historians have increasingly begun to use the term storytelling to describe their practice. And vice versa, a great range of storytelling projects and products have described their practices as oral history. There is, no doubt then, the opportunity to conflate all of these different practices of “storytelling.” In the multi-billion dollar market of “storytelling,” however, oral history is bound to come out at the losing end. This is not about excluding people from oral history, but rather to insist on the importance of our best practices.

Second, and this is even more important, we now live in a culture of “digital storytelling” and similar cultural practices. We may think that as oral historians we are worlds apart from the examples above, but except for the higher production values of multi-million dollar outfits like television stations, we use the same tools and technologies: interviews, audio and video recorders, online dissemination platforms like YouTube. Furthermore, we share (or at least appear to share) the underlying assumption that to help people “put it out there” is somehow good.

I am not a defeatist. I simply argue that learning more about the long history of our instruments and methods will help us better understand and appreciate our own accomplishments, continue to be critical of our methods, and enable us to resist the vortex of confessional culture and the storytelling industry. I would be interested to hear how things are playing out in the regions of the world you are familiar with. For example, how does storytelling and other confessional practices figure into the memorialization and commemoration of the genocides you have studied?

* * * * *

Erin Jessee: To be honest, one of the challenges I’ve been having with this exchange is how to talk about some of the experiences I’ve had and encounters I’ve observed as an oral historian in different settings. I’d shifted from forensic archaeology to oral history and anthropology precisely because I became aware of the violence that could be done to communities in the official pursuit of justice – typically defined in relation to Canadian or international criminal law. With few exceptions, it seemed that the needs of communities in the aftermath of mass violence were often subsumed to the need for justice. In the process, tools like forensic exhumations and international criminal trials became yet another form of violence in the everyday lives of these communities.

I’m reminded of a talk I recently attended given by Amy Tooth Murphy at the Scottish Oral History Centre. She was discussing chrononormativity as a source of discomposure in her work with women in the LGBTQ community. In brief, she found that her efforts to adhere to a life history interview format that moved chronologically from past to present created a narrative rupture between the lives these women had lived and the heteronormative society that surrounded them. It also created uncomfortable silences between the heteronormative ideals they adhered to in public and the lesbian relationships they engaged in in private.

I’ve observed similar discomposure in working with genocide survivors in places like Rwanda and Bosnia, where when faced with the option of moving chronologically through their life history people become mute. The prospect of starting their narratives with their childhood experiences – often positively recalled in relation to the mass violence that followed – can be very painful as it reminds them of what has been lost and inevitably sets the stage for a difficult interview experience for the interviewee. Over time, I learned to abandon the chronological interview format and began starting interviews with open-ended questions like “Tell me about yourself” or “Tell me about your life.” Provided with the option of starting their narratives anywhere they chose and working through their experiences in their own terms, people seemed far more comfortable with the interview experience. And while I’d hesitate to say that any catharsis was achieved, the interview experience appeared to be more positive for my interviewees, though it certainly makes the process of analysis, and the creation of narratives that Westerners would recognize as “good storytelling” more complicated.

* * * * *

To be continued…

Alexander Freund is a professor of history and holds the Chair in German-Canadian Studies at the University of Winnipeg, where he is also co-director of the Oral History Centre. He is co-president of the Canadian Oral History Association and co-editor of Oral History Forum d’histoire orale. With Alistair Thomson, he edited Oral History and Photography (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). He is the author of “Confessing Animals”: Toward a Longue Durée History of the Oral History Interview” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the latest issue of the Oral History Review.

Erin Jessee, in addition to serving on the OHR Editorial Board, is an assistant professor affiliated with the Scottish Oral History Centre (Department of History) at the University of Strathclyde. Her research interests include mass atrocities, nationalized commemoration, spiritual violence, transitional justice, mass grave exhumations, and the ethical and methodological challenges surrounding qualitative fieldwork amid highly politicized research settings. Erin is in the final stages of writing a book manuscript (under consideration with Palgrave MacMillan’s Studies in Oral History series) tentatively titled Negotiating Genocide: The Politics of History in Post-Genocide Rwanda.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow their latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post ‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchange appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTrauma happens, so what can we do about it?A call for oral history bloggersOral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nuns

Related StoriesTrauma happens, so what can we do about it?A call for oral history bloggersOral history, collective memory, and community among cloistered nuns

How to write a classic

By Mark Davie

Torquato Tasso, who died in Rome on 25 April 1595, desperately wanted to write a classic. The son of a successful court poet who had been brought up on the Latin classics, he had a lifelong ambition to write the epic poem which would do for counter-reformation Italy what Virgil’s Aeneid had done for imperial Rome. From his teenage years on, he worked on drafts of a poem on the first crusade which had ‘liberated’ Jerusalem from its Muslim rulers in 1099, a subject which he deemed appropriate for a Christian epic. His ambition reflected the climate in which he grew up: his formative years (he was born in 1544) saw a newly assertive orthodoxy both in literary theory (dominated by Aristotle’s Poetics, published in a Latin translation in 1536) and in religion (the Council of Trent, convened to meet the challenge of Luther’s revolt, was in session intermittently between 1545 and 1563). Those who saw Aristotle’s text as normative insisted that an epic must deal with a single historical theme in a uniformly elevated style, while the decrees emanating from Trent re-asserted the authority of the church and took an increasingly hard line against heresy. As he worked on his poem, Tasso was nervously anxious not to offend either of these constituencies.

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, a multilayered narrative loosely (very loosely) located in the historical setting of Charlemagne’s wars against the Moors in Spain, was published in 1532, and was written in more easy-going times. Ariosto could criticize the Italian rulers of his day, including the papacy, and introduce episodes into his poem which provocatively questioned conventional values, whether rational, social, or sexual, without worrying about the consequences. He could be equally casual about literary proprieties: his freewheeling poem indulged in constant romantic deviations from its main plot, such as it was, and its tone was teasingly elusive, always maintaining an ironic distance between the narrator and his subject-matter.

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, a multilayered narrative loosely (very loosely) located in the historical setting of Charlemagne’s wars against the Moors in Spain, was published in 1532, and was written in more easy-going times. Ariosto could criticize the Italian rulers of his day, including the papacy, and introduce episodes into his poem which provocatively questioned conventional values, whether rational, social, or sexual, without worrying about the consequences. He could be equally casual about literary proprieties: his freewheeling poem indulged in constant romantic deviations from its main plot, such as it was, and its tone was teasingly elusive, always maintaining an ironic distance between the narrator and his subject-matter.

The Orlando furioso was hardly a model for the poem Tasso set out to write; and yet it was hugely popular, and Tasso clearly read and admired it as much as anyone. So Tasso’s poem, as he reluctantly agreed to publish it in 1581 after 20 years of writing and rewriting, embodies the tension between his declared aim and the poem his instincts impelled him to write. It would be hard to argue that the Gerusalemme liberata (The Liberation of Jerusalem) is an unqualified success as a celebration of counter-reformation Christianity; instead it is something much more interesting, an expression of the inner contradictions of late sixteenth-century culture as they were felt by a sensitive – sometimes hyper-sensitive – and gifted poet.

Some of Tasso’s drafts had leaked out during the poem’s long gestation and had been published without his consent, so the poem was eagerly awaited, and it immediately had its devotees. Not everyone, however, was impressed. Among those who were not was Galileo, who wrote a series of acerbic notes on the poem some time before 1609. His criticisms are mostly on details of language and style, but in one revealing comment he compares Tasso’s poetic conceits to ostentatiously difficult dance steps, which are pleasing only if they are ‘carried through with supreme accomplishment, so that their gracefulness overrides their affectation’. Grazia versus affettazione: the terms are taken from Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, that indispensable guide to Renaissance manners which decreed that the courtier’s accomplishments should be displayed with an appearance of effortless nonchalance. Tasso’s offence against courtly manners was that he tried too hard.

The Gerusalemme liberata is indeed full of unresolved tensions – between historical chronicle and romantic fantasy, sensuality and solemnity, the broad sweep of history and the playing out of individual passions. They are what bring the poem to life today, long after the crusades have lost their appeal as a topic for celebration. Galileo rebukes one of Tasso’s heroes for being too easily deflected from his duty by love: ‘Tancredi, you coward, a fine hero you are! You were the first to be chosen to answer Argante’s challenge, and then when you come face to face with him, instead of confronting him you stop to gaze on your lady love’. Tancredi does admittedly cut a rather ludicrous figure when he is transfixed by catching sight of Clorinda just as he is about to accept the Saracen champion’s challenge, but what Galileo didn’t realise was that the very vehemence of his indignation was a testimony to the effectiveness of Tasso’s writing. Plenty of poets wrote about how love mocks the pretentions of would-be heroes, but few dramatised it so effectively – and only Tasso could have written the scene, memorably set to music by Monteverdi, where Tancredi meets Clorinda in single combat, her identity (and her gender) concealed under a suit of armour, and recognises her only when he has mortally wounded her and he baptises her before she dies in his arms.

Galileo was wrong about Tasso’s poem. The very qualities which he deplored make it a classic which inspired poets from Spenser and Milton to Goethe and Byron, composers from Monteverdi to Rossini, and painters from Poussin to Delacroix, and which is still a compelling read today.

Mark Davie taught Italian at the Universities of Liverpool and Exeter. His interests focus particularly on the relation between learned and popular culture, and between Latin and the vernacular, in Italy in the Renaissance. In Oxford World’s Classics he has written the introduction and notes to Max Wickert’s translation of The Liberation of Jerusalem, and has translated (with William R. Shea) the Selected Writings of Galileo.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Statue of Torquato Tasso by Luigi Chiesa. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post How to write a classic appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA religion reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsMoney mattersSherlock Holmes’ beginnings

Related StoriesA religion reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsMoney mattersSherlock Holmes’ beginnings

Arbor Day: an ecosystem perspective

We benefit from forests in ways that go well beyond our general understanding. So, I would like to begin by suggesting that as we responsible citizens observe Arbor Day 2014, we look at forests as more than simply numerous trees growing in stands. Rather, we need to look at forests as ecosystems that are not only important in and of themselves, but also provide essential functions—so-called ecosystem services—to sustain the quality of human life.

For those not totally familiar with its beginnings, Arbor Day began in an area not usually thought as forested. In the 1870s, J. Sterling Morton and his wife moved to the Nebraska Territory (it was not yet a state at that time) and observed the paucity of trees relative to their Michigan roots. And so it was, as the first of more than one million trees were planted 10 April 1872 in the state of Nebraska, that Arbor Day was born. The Mortons’ perspectives greatly anticipated the environmental ethics of Aldo Leopold of the 20th Century—consider this quote from Morton: “Each generation takes the earth as trustees.” What a wonderfully profound sentiment regarding stewardship of nature and natural resources!

Although my family was not participating in an official Arbor Day activity at the time, I have a personal Arbor Day-like experience, one the benefits of which are reaped daily by my wife and me. We moved to our current home in Huntington, West Virginia in 1997, a time when our children were quite young. Now Huntington has the distinction of being the largest Tree City USA city in the state, according to the Arbor Day Foundation. That’s indeed quite notable, considering that West Viriginia is the 3rd most forested state (~77% forested) in the US, exceeded only by Maine (~86%) and New Hampshire (~78%) (Nebraska ranks 46th at ~2%). I took note of that immediately, seeing (primarily) oak trees throughout our new neighborhood. Not surprisingly, my children had never seen so many acorns that first fall, and I encouraged them to find one and plant it in the front yard. Nearly 20 years hence, we have a pin oak (Quercus palustris) as tall as our house, or more—all from that single acorn! That tree provides shade for the front of our house, mitigating summer heat, and it offers food and housing for animals, such as squirrels (and hummingbirds when we hang a feeder on the lower branches). It even allows us to plant shade-tolerant perennials, such as ferns, in our front yard.

But back to the ecosystem perspective. As ecosystems, forests provide a wide variety of services, all of which are essential in maintaining the quality of life on earth. They improve both air and water quality, and they provide some of the greatest biodiversity in the biosphere, comprising an impressive number of life forms and species. Indeed, forests are far more than just trees. Even plants as diminutive as those of the herbaceous layer—what one sees when looking down while walking in the forest—can play a role well beyond their apparent size. Despite its small physical stature, the herb layer comprises up to 90% of the plant diversity of the forest. I often refer to these plants collectively as “the forest between the trees.”

So, this Arbor Day 2014, we should all plant trees indeed! But as we do, let’s also keep in mind that our forests our essential to our own survival—and let’s treat them that way.

Frank Gilliam is a professor of biological sciences at Marshall University, and author of the second edition of The Herbaceous Layer in Forests of Eastern North America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: (1) Barn Red Landscape Clouds Trees Sky Nature Field. Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) Creek and old-growth forest-Larch Mountain. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Arbor Day: an ecosystem perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is ‘lean psychiatry’?The amoeba in the roomNew perspectives on the history of publishing

Related StoriesWhat is ‘lean psychiatry’?The amoeba in the roomNew perspectives on the history of publishing

What is ‘lean psychiatry’?

In 1987, Esmin Green, a patient on the psychiatry ER floor of Kings County Hospital Center, died. International news coverage, lawsuits, and a US Department of Justice investigation ensued. The Behavioral Health department was to ensure the full and timely compliance with the resultant court decrees for drastic improvements in the care of the mentally ill at the hospital.

Our “initial state” was described as a mental health system operating in crisis mode, focused on putting out “fire” after “fire.” We were operating our numerous services in seven old buildings spread over a 44-acre campus. We were short-staffed; a good number of staff had been transferred to our service from other parts of the hospital and unfamiliar with work with psychiatric patients. Morale was low given the seemingly unending onslaught of negative publicity.

The prevailing culture was largely complacent and dispirited. Staff could be described as exhibiting signs of learned helplessness or hopelessness. They were largely not patient-centered or looking to empower patients, and not functioning as a coordinated interdisciplinary team. We lacked a leadership infrastructure and operated with an antiquated care delivery model. Inpatient units operated without “unit chiefs” and records were kept on paper without a system of chart review for quality and compliance. There were no interdisciplinary training programs in place that brought clinicians together with a unified vision of care delivery. There was no model or hunger for change as a result of this learned helplessness that overtook many.

Kings County Behavioral Health needed to dramatically transform all services at Kings County Hospital Center’s behavioral health programs. We envisioned a totally transformed psychiatric ER as well as an inpatient and outpatient infrastructure adequately staffed by caring, competent professionals. We wanted our new building to both symbolize as well as actualize a true transformation from the “snake pit” featured in the New York tabloids to the city’s “flagship” public hospital. Quality and safety processes had to change, and outcomes had to be radically improved with leadership and line staff trained in the profession’s best practices for assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and aftercare. The use of technology and data was seen as a tool to help us lead, manage, and deliver the needed improvement in quality care.

Looking east along Winthrop at Kings County Hospital Center on a sunny late afternoon. Downstate Medical Center is south (right) of this building. Photo by Jim Henderson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

How were we to accomplish this? Where should be begin? How were we to proceed? To guide us along this seemingly impossible journey, it was decided to adopt the principles and practices embodied by lean.

No, “lean” isn’t a euphemism for managed care. Lean refers to a philosophy of management involving the process of identifying value vs. waste in what is delivered to the customer – our patient. Lean empowers the staff that directly does the work to identify waste and inefficiencies and to create solutions to the problems identified. The results are put into effect very quickly, usually within days not months or years later.

We assembled a leadership team, who in turn needed to recruit adequate numbers of competent staff to join our ranks. Then we had to ensure their training so they both understood what was required by the court and had the competencies to deliver what was required by the many policies and procedures that were produced or reviewed and revised to attain compliance. As the senior team was assembled, every former clinical discipline director eventually was replaced with new leaders. Surprisingly, the negative publicity about Kings County seemed to attract, not deter, exceptional leaders and staff, especially when during interviews the senior team displayed openness and a lack of defensiveness about the past, the current challenges and the vast potential for the Behavioral Health Service’s future. It was gratifying to hear the newly recruited leadership speak passionately about their desire to join the challenge of redefining the mental health care system for a population as large as central Brooklyn, seeing it as a once-in-a-career opportunity. Most of our new leadership came from other inner-city hospitals and were familiar both with our community culture and with the many challenges presented in such settings.

We have learned that even if you invest in the right number of sufficient staff, if your processes are faulty your people will fail. Ultimately, we needed to integrate each of the many fragmented services into one seamless continuum that improved access to care and delivered state of the art care in a timely and cost-effective way: better health, better quality care, and reduced overall cost.

Kings County Hospital Center Behavioral Health Services now has the tools, experience, and mentoring to achieve and sustain our gains, utilizing the philosophy and methodology of lean. We will continue to add value, decrease waste, improve performance, and become a center of excellence for our community.

Joseph P. Merlino, MD, MPA is the chief executive for behavioral health services and Director of Psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, where he leads the transformation efforts of one of the largest public hospitals in New York. He is the co-editor of Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story with Joanna Omi and Jill Bowen.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What is ‘lean psychiatry’? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNew sodium intake research and the response of health organizationsThe continuing threat of nuclear weaponsNew perspectives on the history of publishing

Related StoriesNew sodium intake research and the response of health organizationsThe continuing threat of nuclear weaponsNew perspectives on the history of publishing

Kerry On? What does the future hold for the Israeli-Palestinian peace process?

By Martin Bunton

It may be premature to completely write off the recent round of the US-sponsored Israeli-Palestinian peace process. The talks faltered earlier this month when Israel failed to release a batch of prisoners, part of the initial basis for holding the negotiations launched last July. The rapidly disintegrating diplomacy may yet be salvaged. But the three main actors have already made it known they will pursue their own initiatives.

They each may think that their actions will allow them to accumulate more leverage, maybe help position themselves in anticipation of a resumption of bilateral negotiations which, for over twenty years now, has been directed towards establishing a Palestinian state living peacefully alongside Israel. But it is also possible that the steps the parties take will instead deepen the despair of a two state framework ever coming to fruition.

Benjamin Netanyahu

The United States will focus their attention to other pressing issues, such as securing a deal on Iran’s nuclear program. Progress on this front may encourage, perhaps even empower, the Obama administration to resume Israeli-Palestinian negotiations later in its term. But the chances of their success will depend less on yet another intense round of shuttle diplomacy by US Secretary of State John Kerry, and more on whether a distracted Obama presidency will be prepared to pressure Israel to end its occupation. True, Obama enjoys the freedom of a second term presidency (unconcerned about the prospects of re-election). So far however he hasn’t appeared at all inclined to challenge Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

As for Israel, the Netanyahu government will take steps to make life even harder for Palestinians under occupation, and no doubt further entrench its settlement infrastructure in the West Bank, the territory on which Palestinians want to build their own state. Netanyahu, now one of the longest serving prime ministers in Israeli history, has provided very few indications that he is willing to enable the Palestinians to build a viable and contiguous state. He appears confident that the status quo is tenable, and that occupation and settlement of the West Bank can continue to violate international law without facing any serious repercussions. The more likely outcome of such complacency, however, is the irrevocable damage inflicted on the prospects of a two state solution and the harm done to Israel’s security, possibly subjecting it to a wide ranging international boycott movement.

Meanwhile, the Palestinian government, led by Mahmoud Abbas, will desperately strive to ensure that the breakdown of talks not lead to the collapse of his Palestinian Authority. Abbas may seek to use this opportunity to lessen the overall reliance on US sponsorship and achieve Palestinian rights in international bodies such as the UN and the International Court of Justice. This move may placate the growing number of Palestinians who until now have angrily dismissed Abbas’ participation in American-sponsored bilateral negotiations as doing little more than provide political cover to the on-going Israeli occupation, begun almost 50 years ago. But the majority of Palestinians will continue to disparage of how the pursuit of their national project has been paralysed by the weakness and corruption of their leaders and the absence of a unified government and coherent strategy.

Mahmoud Abbas

Though no side wants to be blamed for the collapse of negotiations, it is easy to see how a cycle of action and recrimination could scupper all attempts to revitalize them. More to the point, however, is to ask whether the steps taken will end up burying the very prospects of a two-states solution to the century long conflict which the negotiations are supposed to achieve.

Martin Bunton is an Associate Professor in the History Department of the University of Victoria and author of the recently published The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2013).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Benjamin Netanyahu. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons; (2) Mahmoud Abbas. By World Economic Forum from Cologny, Switzerland (AbuMazem). CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Kerry On? What does the future hold for the Israeli-Palestinian peace process? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesVery short talksA question of consciousnessIn memoriam: Ariel Sharon

Related StoriesVery short talksA question of consciousnessIn memoriam: Ariel Sharon

April 24, 2014

Vaccines: thoughts in spring

Every April, when the robins sing and the trees erupt in leaves, I think of Brad — of the curtain wafting through his open window, of the sounds of his iron lung from within, of the heartache of his family. Brad and I grew up at a time when worried mothers barred their children from swimming pools, the circus, and the Fourth of July parade for fear of paralysis. It was constantly on everyone’s minds, cast a shadow over all summertime activities. In spite of the caution, Brad got polio — bad polio, which further terrorized our mothers. It still haunts me. If, somehow, he had managed to avoid the virus for a couple years until the Salk vaccine arrived, none of that — the iron lung, the shriveled limbs, the sling to hold up his head — would have happened.

In 1954, many children in my town, myself included, became “Polio Pioneers” because our parents made us participate in the massive clinical trial of the Salk vaccine. Some of us received the shot of killed virus, others received a placebo. We were proud, albeit scared, to get those jabs, to be part of a big, important experiment. Our moms and dads would have done anything to rid the country of that dreaded disease.

Because the vaccine is so effective, mothers today aren’t terrified of polio. Children in our neighborhoods aren’t growing up in iron lungs or shuffling to school in leg braces. We seem so safe. But our world is smaller than it used to be. The oceans along our coasts can’t stop a pestilence from reaching us from abroad. A polio virus infecting a child in Pakistan, Nigeria, or Afghanistan can hop a plane to New York or Los Angeles or Frankfurt or London, find an unimmunized child, and spread to other unimmunized people. Our earth is not yet free of polio.

Germs are like things that go bump in the night. They can’t been seen, they lurk in familiar places, they are sometimes very harmful, and they instill great fear—some justified, some not.

Fear of measles, like fear of polio, is justified. In the old days, one in twenty children with measles developed pneumonia, one or two in a thousand died. The vaccine changed all that in the developed world. But, measles continues to rage in underdeveloped countries. In a race for very high contagiousness, the measles virus ties the chickenpox virus (which causes another vaccine-preventable childhood infection). Both viruses can catch a breeze and fly. Or they may linger in still air for over an hour. They, too, ride airplanes. This year alone, outbreaks of measles started by imported cases have occurred in New York, California, Massachusetts, Washington, Texas, British Columbia, Italy, Germany, and Netherlands.

Fear of whooping cough (aka pertussis) is also justified. In the pediatric hospital where I work, two young children have died of this infection in the past several years and many others have suffered from the disease, which used to be called “the one-hundred day cough.” It lasts a long time and antibiotic treatment does nothing to shorten the course. Young children with pertussis may quit breathing, have seizures, or bleed into their eyes. It spreads like invisible smoke around high schools and places where people gather … and cough on each other.

On the other hand, fear of vaccines — immunizations against measles, polio, chickenpox, or whooping cough — is hard to understand. In the grand scheme of things, any of these serious infections is a much greater threat than the minimal side effects of a vaccine to prevent them. Just ask the mothers of the children who died of pertussis in my hospital. It’s true that the absolute risk of these infections in resource rich areas is small. But, for even rare infections, a 0.01% risk of disease translates into hundreds of healthy children who don’t have to be sick, or worse yet die, of a preventable infection.

In spite of the great success of vaccines, they aren’t perfect. Perfection is a tall order. Still we can do better. Fortunately, because of the work of my medical and scientific colleagues, new vaccines under development hold promise to be more effective with fewer doses, to provide increased durability of vaccine-induced immunity, and to be even freer of their already rare side effects. And, we’re creating vaccines against respiratory syncytial virus, Staphylococcus aureus, group A Streptococcus, herpes virus, and HIV, to name a few.

Brad would be proud of how far we have come in protecting our children from the horrible affliction that crippled him. He’d also be furious at our failure to vaccinate all our children. Every single one of them. He’d tell us that no child should ever be sacrificed to the ravages of polio or measles or chicken pox or whooping cough.

Janet R. Gilsdorf, MD is the Robert P. Kelch Research Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School and pediatric infectious diseases physician at C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Ann Arbor. She is also professor of epidemiology at the University of Michigan and President-elect of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Her research focuses on developing new vaccines against Haemophilus influenzae, a bacterium that causes ear infections in children and bronchitis in older adults. She is the author of Inside/Outside: A Physician’s Journey with Breast Cancer and the novel Ten Days.

To raise awareness of World Immunization Week, the editors of Clinical Infectious Diseases, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, and Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society have highlighted recent, topical articles, which have been made freely available throughout the observance week in a World Immunization Week Virtual Issue. Oxford University Press publishes The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, and Open Forum Infectious Diseases on behalf of the HIV Medicine Association and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society on behalf of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS).

The Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (JPIDS), the official journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, is dedicated to perinatal, childhood, and adolescent infectious diseases. The journal is a high-quality source of original research articles, clinical trial reports, guidelines, and topical reviews, with particular attention to the interests and needs of the global pediatric infectious diseases communities.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Vaccination. © Sage78 via iStockphoto.

The post Vaccines: thoughts in spring appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBreastfeeding and infant sleepTrauma happens, so what can we do about it?The continuing threat of nuclear weapons

Related StoriesBreastfeeding and infant sleepTrauma happens, so what can we do about it?The continuing threat of nuclear weapons

An intriguing, utterly incomplete history of Louis Armstrong

April is Jazz Appreciation Month, honoring an original American art form. Across the United States and the world, jazz lovers are introducing people to the history and heritage of jazz as well as extraordinary contemporary acts. To celebrate, here are eight songs from renowned jazz singer and trumpeter Louis Armstrong‘s catalog, along with some lesser-known facts about the artist.

Heebie Jeebies (1926)

One of Armstrong’s first recordings as bandleader was a series of singles released under the name Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five, which were later regarded as a watershed moment in the history of jazz. “Heebie Jeebies” in particular gained fame, and historical importance, for its improvised “scat” chorus; according to legend, this off-the-cuff vocal part was the result of Armstrong dropping his sheet music during the recording.

Struttin’ With Some Barbecue (1927)

Armstrong’s second wife, Lil Hardin Armstrong, was instrumental in orchestrating his rise to prominence. Hardin was also an accomplished jazz pianist and composer, frequently collaborating with Armstrong; “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue” is one of her most-beloved contributions to the jazz canon.

Muggles (1928)

Long before J.K. Rowling transformed the word, “muggles” was a slang term for marijuana, a drug of which Armstrong was a lifelong enthusiast. This highly-esteemed composition by Armstrong was recorded with a group of the day’s foremost jazz talents, among them the legendary pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines.

Ain’t Misbehavin’ (1929)

Although Armstrong had achieved renown among black listeners through his work in the ‘20s, it was this song, performed between acts during the Broadway musical Hot Chocolates, which arguably gained him his first crossover success. Originally written as an excuse to have Armstrong sing from the orchestra pit, its success led the producers to rewrite the script in order to bring him onstage, then send him to the studio to record the production’s hits.

Where The Blues Were Born In New Orleans (1947)

The film New Orleans featured Armstrong alongside Billie Holiday, in her only film role; the pair portrayed musicians who develop a romantic relationship. This track includes a lengthy section in which Armstrong introduces his ensemble, featured in the film, which was loaded with the day’s biggest names: Kid Ory, Zutty Singleton, Bud Scott, and more.

Mack the Knife (1955)

In the later decades of his career, Armstrong’s lip muscles no longer allowed him to perform the same kind of trumpet pyrotechnics he’d become known for earlier in his career. As a result, he began to rely more on pop vocal performances, such as this, one of his best-known songs of all time. Taken from The Threepenny Opera, Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s anticapitalist stage drama, “Mack” became a major pop success (although it did not achieve the same recognition as the white singer Bobby Darin’s #1 version, released four years later).

Hello, Dolly (1964)

Probably the biggest hit of Armstrong’s career, this song, taken from the eponymous musical, took the #1 spot on the pop charts from the Beatles during the height of Beatlemania.

What a Wonderful World (1967)

Perhaps surprisingly, this song — perhaps the tune most closely associated with Armstrong — was not a hit in America upon its release, selling only about 1000 copies. Over time, owing to its frequent use in films and numerous cover versions, the song would eclipse all others in Armstrong’s discography to become his signature recording, but not until long after his death in 1971.

Grove Music Online has made several articles available freely to the public, including its lengthy entry on the renowned jazz singer and trumpeter Louis Armstrong. Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Louis Armstrong, jazz trumpeter, 1953. World-Telegram staff photographer. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An intriguing, utterly incomplete history of Louis Armstrong appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCreative ways to perform your music: tips for music studentsApril Fool’s! Announcing winner of the second annual Grove Music spoof contest25 recent jazz albums you really ought to hear

Related StoriesCreative ways to perform your music: tips for music studentsApril Fool’s! Announcing winner of the second annual Grove Music spoof contest25 recent jazz albums you really ought to hear

New perspectives on the history of publishing

There is a subtle shift occurring in the examination of the history of the book and publishing. Historians are moving away from a history of individuals towards a new perspective grounded in social and corporate history. From A History of Cambridge University Press to The Stationers’ Company: A History to the new History of Oxford University Press, the development of material texts is set in a new context of institutions.

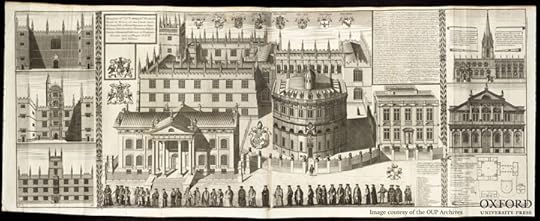

The University processes in fron of the Sheldonian Theatre and Clarendon Printing House, 1733 (William Williams, Oxonia depicta, plate 6).

Recently, Dr Adam Smyth, Oxford University Lecturer in the History of the Book, spoke with Ian Gadd, Professor of English Literature at Bath Spa University and the editor of Volume I: From its beginnings to 1780 of the History of Oxford University Press, about the early modern history of the book. They discuss the evolution of university presses, the relationship between Oxford and the London book trade, navigating the division of learned and scholarly publishing and commercial work, and some new insights into the history of the Press, such as setting William Laud’s vision of the Press in the context of university reform and the role of the University’s legal court in settling trade disputes.

Podcast courtesy of the University of Oxford Podcasts.

Ian Gadd is Professor of English Literature at Bath Spa University. He is editor of The History of Oxford University Press, Volume 1: From its beginnings to 1780.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image courtesy of OUP Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post New perspectives on the history of publishing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy are money market funds safer than the Bitcoin?The politics of green shoppingA bookish slideshow

Related StoriesWhy are money market funds safer than the Bitcoin?The politics of green shoppingA bookish slideshow

Mini maestro mystifies me

Sometimes you think you can explain something, and then it turns out you really can’t. This remarkable video was posted last year but only went viral in the US in the last few weeks, approaching 5 million hits in a short time. When I first saw it, I was immediately enchanted.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Dubbed by the press as ‘the Mini Maestro’ (although to be correct, she would be a maestra), the video shows little Lara Glozou with a church choir in Kyrgyzstan. She’s the young daughter of one of the choir members and often attends rehearsal.

After watching a few times, I thought I knew what might be happening. This must be an observant child who’s mirroring the actions of a conductor standing in front of the choir, interspersed with a little improvisation of her own. I thought she was a remarkable imitator, not just able to capture the conductor’s motions, but also the emotions.

But then I found another video. It shows the choir rehearsing the same song from another angle, allowing us to see the conductor’s motions of the right hand while Lara is gesturing expressively in the far right corner by the piano.

Click here to view the embedded video.

I was amazed to see that the conductor is not making the same kinds of motions as Lara after all. Even though the conductor’s gestures may be outlining the regularity of the beat and phrasing, many of Lara’s gestures and body movements—the forward lean, the hand to the chest, the sway of the body, and the dips and turns of the head—seem to be her own.

To be fair, Lara is not really “conducting.” If she were directing, her motions would come slightly before the events in the music, in anticipation of them in order to cue the choir. Her movements are more like an expression of the music. However, as an expression or sensitive interpretation of the music, I find her gestures to be remarkable. Truly extraordinary. For instance, her gestures are fewer and more prolonged during the female solo up to 0:21 (on the first video). They are a series of poses. But at 0:22 when the choir comes in, she immediately shifts to grand sweeping gestures. The variety of shapes that she forms with her hands alone express a rainbow of emotions and tone colors.

I am in awe of this little girl’s ability not only to reflect peaks and valleys in the melody of the music, and momentum of the phrases, but also the shape of the sound. For the last note of the song, she curves her left and right hands into the widest arcs for a broad final tone — a lion’s roar — rather than the kind of ending that gradually fades away.

This small child has had so little time on earth to experience falling in love, the sting of heartbreak, betrayal, triumph, grief, pain, and the rest of the great emotional topography of life. How is she able to convey the semblance of emotional depth and angst? Where is she getting her musical sensitivity? Do some young children just have an old soul?

As a former music major, I took Conducting 101. My spine was rigid, my gestures were tiny and angular. As a music student in my 20s, I had none of the intensity and theatrical weight of this little girl. More recently, I have written about how infants begin to spontaneously respond to music in bodily ways, nodding their heads and waving arms to rhythmic music once they are able to sit freely at about six months. Later, bobbing up and down with knee-bends, and spinning around in circles to music between one and two years, after they become mobile.

However, they do so for only short bursts, and most of the movements of two- and three-year-old children don’t really match the music in time (Moog, 1976; Malbrán, 2000). Although Lara is not always synchronized with the music, her deep expressive gestures capture the musical events in a broad way, even anticipating some musical moments, as she is familiar with this piece.

Little is known about young children’s interpretation of music. In one of the few studies in this area, Boone & Cunningham (2001) showed that four-year-olds can move a flexible teddy bear in dance-like fashion, to express emotion in music through movement. However the musical emotions they recognized and expressed were basic emotions (such as happiness, or sadness, or anger). What we seem to observe in Lara is much more nuanced. How is she able to capture this depth in music?

I spoke with a grown-up maestro that I greatly admire, Andrew Koehler, Music Director of the Kalamazoo Philharmonia. He said, “It’s really astonishing. Lara moves in a way that shows that she recognizes agogic accents“ (longer durations of tones, which give natural stress to music). She often reflects this with larger, more expansive motions of her arms that mark those accents.

Her gestures also capture finer details. At 0:45 to 0:47 in the first video, Koehler points out how a higher tone of greater tension resolves to a lower tone of lower tension. The toddler reflects this: “Lara leans into the music, her right hand pushing into it with a claw-like motion [capturing high tone and high tension in the music]. Then both left and right arms make downward motions as her posture goes back to an upright position again [lower tone, lower tension].”

And then there’s Jonathan Okseniuk. Here he is at three years old, appearing to ‘conduct’ a recording of the last movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in his home in Mesa, Arizona.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Even if he appears to be getting some coaxing off camera, this is a remarkable three-year-old.

Here is Jonathan again at age four, conducting a live orchestra in a rousing rendition of Khachaturian’s ‘Sabre Dance’. “This is a more challenging arena,” explains Koehler, “which would require Jonathan to anticipate what will happen in the music as opposed to simply responding to it.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

There are many other videos of Jonathan on the web, conducting Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart, and Strauss with different orchestras.

How an understanding of music blooms so early in some young ones astonishes me. This mini-maestra’s sensitive expression of music and mini-maestro’s early conducting chops have left me perplexed.

Siu-Lan Tan is Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA. She is primary editor of The Psychology of Music in Multimedia (Oxford University Press 2013), the first book consolidating the research on the role of music in film, television, video games, and computers. A version of this article also appears on Psychology Today. Siu-Lan Tan also has her own blog, What Shapes Film? Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mini maestro mystifies me appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat’s the secret to high scores on video games?Expressing ourselves about expressiveness in musicThe amoeba in the room

Related StoriesWhat’s the secret to high scores on video games?Expressing ourselves about expressiveness in musicThe amoeba in the room

The amoeba in the room

The small picture is the big picture and biologists keep missing it. The diversity and functioning of animals and plants has been the meat and potatoes of most natural historians since Aristotle, and we continue to neglect the vast microbial majority. Before the invention of the microscope in the seventeenth century we had no idea that life existed in any form but the immediately observable. This delusion was swept away by Robert Hooke, Anton van Leeuwenhoek, and other pioneers of optics who found that tiny forms of life looked a lot like the cells that comprise our own tissues. We were, they showed, constructed from the same essence as the writhing animalcules of ponds and spoiled food. And yet this revelation was somehow folded into the continuing obsession with human specialness, allowing Carolus Linnaeus to catalogue plants and big animals and ignore the lilliputian majority. When microbiological inquiry was restimulated by Louis Pasteur in the nineteenth century, it became the science of germs and infectious disease. The point was not to glory in the diversity of microorganisms but exterminate them. In any case, as before, most of life was disregarded.

Things are changing very swiftly now. Molecular fishing expeditions in which raw biological information is examined using metagenomic methods have discovered an abundance of cryptic life forms. This research has made it clear that we are a very long way, centuries perhaps, from comprehending biodiversity properly.

Revelation of the human microbiome, the teeming trillions of bacteria and archaea in our guts that affect every aspect of our wellbeing, is the best publicized part of the inquiry. We are walking ecosystems, farmed by our microbes and dependent upon their metabolic virtuosity. There is much more besides, including the fact that a single cup of seawater contains 100 million cells, which are in turn preyed upon by billions of viruses; that a pinch of soil teems with incomprehensibly rich populations of cells; and that 50 megatons of fungal spores are released into our air supply every year. Even the pond in my Ohio garden is filled with unknowable riches: the most powerful techniques illuminate the genetic identity of only one in one billion of the cells in its shallow water.

Most biologists continue to be concerned with animals and plants, the thinnest slivers of biological splendor, and students are taught this macrobiology—with the occasional nod toward the other things that constitute almost all of life. Practical problems abound from this nepotism. Ecologists study things muscled and things leafed and conservationists worry most about animals, arguing for expensive stamp-collecting exercises to register the big bits of creation before they go extinct. This is a predicament of considerable importance to humanity. Consider: A single kind of photosynthetic bacterium absorbs 20 billion tons of carbon per year, making this minuscule cell a stronger refrigerant than all of the tropical rainforests.

Surveying our planet for its evolutionary resources, the perceptive extraterrestrial would report that Earth is swarming with viral and bacterial genes. The visitor might comment, in passing, that a few of these genes have been strung together into large assemblies capable of running around or branching toward the sunlight. It is time for us to embrace this kind of objectivity and recognize that the macrobiological bias that drives our exploration and teaching of biology is no more sensible than attempting to evaluate all of English Literature by reading nothing but a Harry Potter book. The science of biology would benefit from a philosophical reboot.

Nicholas P. Money is Professor of Botany and Western Program Director at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. He is the author of more than 70 peer-reviewed papers on fungal biology and has authored several books. His new book is The Amoeba in the Room: Lives of the Microbes.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Scanning electron micrograph of amoeba, computer-coloured mauve. By David Gregory & Debbie Marshall, CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0, via Wellcome Images.

The post The amoeba in the room appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEarth Day, 44 years onGlobal responsibility, differentiation, and an environmental rule of law?New sodium intake research and the response of health organizations

Related StoriesEarth Day, 44 years onGlobal responsibility, differentiation, and an environmental rule of law?New sodium intake research and the response of health organizations

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers