Oxford University Press's Blog, page 815

May 5, 2014

Whaling in the Antarctic Australia v. Japan (New Zealand intervening)

After four years of anticipation the International Court of Justice delivered a Judgment in the whaling case. The Judgment raises many issues of ecological nature. It also analyses and interprets the provisions of the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) thus enriching the law of treaties.

Historically whaling has been a contentious issue. Even early attempts at its international regulation were contested. The need for the regulation of whaling was brought to the League of Nations attention in 1925 by M. José Suarez in his report on Codification Questionnaire no. 7 ‘Exploitation of the Products of the Sea’ in which observed that the modern whaling industry was ‘rapidly exterminating the whale’. Before the Second World War there two Conventions attempted to regulate the whaling. The Convention for Regulation of Whaling was opened for signature in Geneva on 24 September 1931 and signed by 31 States (with only eight ratifications), and 1937 Agreement for the Regulation of Whaling and Final Act was signed on 8 June 1937.

The 1946 ICRW had a double purpose: the protection of whales and the orderly regulating of the whaling industry, which at the time of this Convention was thriving. However, with the passage of time the ecological purpose of the Convention started to play the more prominent role, culminating in the establishment of the 1982 moratorium on commercial whaling (“zero quotas” effective in 1985-86 season). That decision lead to the amendment of the Schedule (para. 10e) that is an integral part of the Convention. However, Norway opted out of this decision on moratorium and Iceland appended a reservation after the re-joining the Convention, thus both States still continue commercial whaling, setting their own national quotas outside the jurisdiction of the International Whaling Commission (IWC), the Convention’s regulatory body. Japan initially opted out of moratorium but later withdrew it.

The IWC consists of eighty-nine States, the majority of which are non-whaling States, making it a rather unusual international institution. It would be a simplification to argue that there is only a handful of States opposing resuming of the commercial whaling. The IWC is in a permanent crisis due to its policies. These tensions were expressed in the 2006 St Kitts and Nevis Declaration, in which several States stated “their concern that the IWC has failed to meet its obligations under the terms of the ICRW” and declared their “commitment to normalize the functions of the IWC based on the terms of the ICRW and other relevant international law, respect for cultural diversity and traditions of coastal peoples and the fundamental principles of sustainable use of resources.”

The ICRW permits three types of whaling: commercial, scientific, and aboriginal (subsistence) whaling — all of them very complex legally and contentious. After 1986 Japan has conducted whaling operations in the Southern Ocean under the auspices of the scientific research or special permit. Whale Research Program under Special Permit in the Antarctic‟ (JARPA I) began in the year following the 1986 moratorium. The JARPA II began in 2005.

A Minke whale and her 1-year-old calf are dragged aboard the Nisshin Maru, a Japanese whaling vessel. Photo by Australian Customs and Border Protection Service, 6 February 2008. CC BY-SA 3.0 Australia via Wikimedia Commons.

The subject-matter of the recent Judgment of the International Court of Justice was Japanese scientific whaling based on Article VIII of the ICRW, which permits State parties to issue special permits authorizing the taking and killing of whales for scientific purposes. This type of whaling (unlike commercial and aboriginal) is regulated by national authorities, not the IWC. State parties issuing permits under Article VIII have only a procedural requirement of reporting to the IWC.

In very broad brushstrokes the case was based on Australia’s allegation that Japanese scientific whaling was in fact a disguised commercial whaling; moreover, Australia alleged bad faith on the part of Japan. Japan relied in its pleadings on a long tradition of eating whale meat and arguing that in fact the analysis of the ICRW permits sustainable whaling. The case also has certain jurisdictional issues. The court unanimously found it had jurisdiction to hear the case, and by 12 votes to 4 found that special permits granted by Japan in connection with the program, JARPA II, did not fall within the IWC convention.

From the point of view of the law of treaties, the interpretation of Article VIII of the ICRW was of fundamental importance. The Court noted that taking into account the Preamble and other provisions of the ICRW, neither a restrictive not an expansive interpretation of Article VIII is justified. The Court observed that the programmes for purposes of scientific research should foster scientific knowledge. They may pursue an aim other than either conservation or sustainable exploitation of whale stocks. The Court, however, has not provided the definition of scientific research but analysed and interpreted the phrase “for purposes of”.

The Court concluded that although Art. VIIII of the ICRW exempts from the Convention grant of special permits, scientific whaling is not outside of the Convention. Therefore the ‘margin of appreciation’ of States (members of IWC in such a type of whaling as pleaded by Japan) is not unlimited and must conform with an objective standard (para 62 of the Judgment). The Court raised doubts over increased sample sizes between the country’s first whaling program and JARPA II. It also noted lack of transparency in how its sample sizes were determined and found that Japan has not sufficiently substantiated the scale of lethal sampling. The Court stated that JARPA II involves activities that in broad terms can be characterized as scientific research, but that “the evidence does not establish that the design and implementation of the Program are reasonable in relation to achieving its stated objectives.” The Court concluded that JARPA II is not “for purposes of scientific research” pursuant to Article VIII (1) of the Convention and that Japan violated the three relevant provisions (paragraphs 7(b), 10 (d) and (e)) of the schedule.

Most importantly, the Court has emphasized the lack of Japan’s willingness to cooperate with the IWC in the use of non-lethal scientific methods which became available intervening years.

The ICJ therefore ordered revoking by Japan any pending authorization, permit or license to kill, take or treat whales in relation to JARPA II, and refraining from granting any further permits under Article VIII (1) of the Convention, in pursuance of that Program. Japan said it would abide by the decision but added it “regrets and is deeply disappointed by the decision”.

The Judgment of the Court does not impact of future scientific whaling of Japan and the Court noted that Japan will rely on Judgment’s findings ‘as it evaluates the possibility of granting any future permits under Article VIII, paragraph 1, of the Convention’ (para. 246 of the Judgment).

By judicial necessity, the Court only discussed the case at hand but as a result it has not submitted any definition of scientific whaling and declined to adopt a specific set of criteria to this effect. It declined to discuss commercial whaling and also indigenous whaling. It made some general observations as to linking scientific whaling to the whole nexus of rights and obligations of States under the ICRW and clarified the issue of the margin of appreciation regarding the issuance of special permits, both are a very useful observations but of certain complexity in implementation. It also admitted the possibility of future Japanese whaling, as indeed it cannot be prohibited. In the meantime Japanese scientific whaling in northwestern Pacific is to continue (as well as Icelandic). The Judgment has not resolved the basic conflicts and has not addressed general issues.

There have been a wide-spread applaud as to the Court’s Judgment, which of course is fully understandable. However, there are many questions which were raised by this Judgement relating to the law of treaties and whaling itself. For example there is a question of the choice of the canons of the interpretation of an international legal instrument: the classical rule of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties or much more daring and contentious evolutionary interpretation (applied with varying degree of success by the European Court of Human Rights), which is closely connected to the issue of consent. The textual interpretation of the ICRW clearly indicates that it allows scientific whaling and commercial whaling. Does the development of general international environmental law, including the preservation and protection of fauna and flora permit a different, evolutionary interpretation that prohibits these activities?

Japan agreed to abide by the Judgment but theoretically it could leave the Convention on commercial whaling, which would defeat the purpose of the Judgment. It can also leave and later re-join the Convention with a reservation (as Iceland did). What about Icelandic scientific whaling? It wasn’t challenged before the Court but it exists and the Judgement will not make any difference to it.

However, the Judgment has provided a very fertile ground for further studies.

Malgosia Fitzmaurice is the co-editor of The IMLI Manual on International Maritime Law, Volume I: The Law of the Sea with David Attard and Norman Martinez. She is a Professor of Public International Law at Queen Mary, University of London. She specialises in international environmental law, treaties, indigenous peoples and Arctic law and has published widely on these subjects.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Whaling in the Antarctic Australia v. Japan (New Zealand intervening) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUkraine and the fall of the UN systemASIL/ILA 2014 retrospectiveIs the planet full?

Related StoriesUkraine and the fall of the UN systemASIL/ILA 2014 retrospectiveIs the planet full?

Do immigrant immigration researchers know more?

The political controversies over immigration intensify across Europe. Commonly, the arguments centre around its economic costs and benefits, and they reduce the public perception of immigrants to cheap workforce. Yet, increasingly, these workers are highly skilled professionals, international students, and academics. Their presence transforms not only labour markets but also the production of knowledge and, in the end, it changes the way we all perceive immigrants and immigration.

US American scholars were first to draw attention to how immigrant scholars influence the academic field. The historian of migration Nancy Foner claimed a decade ago that the increasing group of students and faculty who study and work abroad — immigrants to the United States — heavily change the way immigration is perceived in social sciences. Immigrant scholars — according to Herbert J. Gans, a German-born American sociologist — contributed to the paradigm shift in American migration studies, from assimilationist to retentionist approach. They did so, because they were ‘insiders’ to the groups they studied; they were immigrant researchers researching immigrants.

A century ago, public interest (and funds) fueled studies on immigration by sociologists, demographers, economists and historians. The results of their studies were widely spread by journalists, novelists and mass entertainment industries. Now, budget cuts in higher education, and the increase of impact-seeking funding of the European Union, foster the concern about the societal benefits of social sciences. Paradoxically, the public interest in research on immigrants seems to fall, and academics apparently lose their capability of influencing broad publics and the politics in Europe, the boats on Lampedusa being a symbol of this problem.

For scholars who reply to short-term concerns of national public policy, the urgent question is the effectiveness of transfer of knowledge between academic and other systems that is driven by the hope for formulating better policies. Some scholars are yet reluctant to actively participate in public debates because they see their scientific objectivity in danger. The position of those scholars researching immigration who are immigrants themselves is no less ambivalent: they may play the ‘ethnic card’ to secure funding for research and access to people whom they want to study. Financial reasons may compel many to do research in their native country and they also meet the suspicion of fellow academics that tend to suspect they might lack scientific distance and objectivity.

What societal roles are available for immigrant researchers researching immigrants? Too often we look for answers to this question by tracking the processes of policy decision making, by investigating the “big-P”-politics. We are used to thinking of production of ideas and texts as separate from the impact we think they will have. Yet the way that knowledge is being negotiated during the production of texts is a key to understanding the role migration researchers studying immigrants play for the society.

Let us imagine a research situation, an interview, which is undoubtedly the most widely applied technique for conducting systematic social inquiry: a researcher typically asks questions and listens carefully to the stories the respondent tells. While one of them may say less and the other more, they interact. Interviews are interactional, and during this situation, both the researcher and the researched subject negotiate the meaning they assign to norms, values, ideas, other people, their behaviour, etc. Let’s assume both parties in this situation are immigrants. From my personal experience as an interviewer and immigrant, I recall multiple research encounters during which my interview partners prompted me to confirm their views: “you surely know, you are also an immigrant” or “you do understand me, you are also from Poland”. They presume that because of our common origin, we have a lot in common, that being an immigrant might bring us together, foster mutual understanding of problems, or even make us share the same norms and values.

But common origin does not produce ‘common individuals’, and each migration trajectory is different. It matters that I am born in Warsaw in a middle class family, have university education and work as a professor at a German university while my research subjects come from rural areas in Poland, left school early and perform manual jobs in United Kingdom. Each time I ask a question and they answer it, each time I prompt them — seemingly impersonally and in a highly controlled fashion — to continue narrating, my interview partners and I question the latent national and ethnic categories of commonality. Unintentionally, in the course of such research encounter, when confronted with misunderstandings or incomprehension, we revisit our gendered, ethnic, class, or professional identities.

For most researchers, such experiences are common and obvious. But they reflect on them in a self-referential fashion, addressing the issue to colleagues subscribing to journals on methodology of qualitative research. They aim at improving the quality of research but the meaning of this self-reflection is deeper and should be communicated to wider audiences.

It matters that when the researcher is an immigrant herself: it influences the research process, the access to research subjects and funding, and the way results of the studies are interpreted (because the researcher is sympathetic, or empathetic, to particular problems of her respondents). More importantly, immigrant immigration researchers are capable and predisposed to reveal the artificiality of fixed categorisations assigning people to places on the map and positions in social hierarchies. When they do so, they show us a possibility for new, better, modes of societal integration. In countries like Germany that have long been shaped by low-skilled immigration and public discourses around it, there is a minor but growing interest in the perspectives of immigrant researchers. Through stronger engagement in dialogue with wider audiences, the immigrant researchers can accelerate this trend. This much needed change of perspective has a chance of becoming mainstream if immigrant researchers talk about their work and research experiences with more self-confidence.

Prof. Dr. Magdalena Nowicka is from Humboldt-University in Berlin. She is a co-author of the paper ‘Beyond methodological nationalism in insider research with migrants‘, which appears in the journal Migration Studies.

Migration Studies is an international refereed journal dedicated to advancing scholarly understanding of the determinants, processes and outcomes of human migration in all its manifestations, and gives priority to work presenting methodological, comparative or theoretical advances.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Visa application. By VIPDesignUSA, via iStockphoto.

The post Do immigrant immigration researchers know more? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe ‘internal’ enlargement of the European Union – is it possible?Ukraine and the fall of the UN systemWhen science stopped being literature

Related StoriesThe ‘internal’ enlargement of the European Union – is it possible?Ukraine and the fall of the UN systemWhen science stopped being literature

May 3, 2014

Is the planet full?

Is the planet full? Can the world continue to support a growing population estimated to reach 10 billion people by the middle of the century? And how can we harness the benefits of a healthier, wealthier and longer-living population?

Professor Ian Golding, together with leading academics Professor Sarah Harper, Dr Toby Ord, Professor Robyn Norton, and Professor Charles Godfray, introduced this topical subject at the Oxford Literary Festival 2014. While it is common to hear about the problems of overpopulation, there might be unexplored benefits of increasing numbers of people in the world. Find out more about this intriguing themes watching the panel at the Oxford Martin School of academics debating the intended and unintended impacts of population and economic growth.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Ian Goldin is the Director of the Oxford Martin School and Professor of Globalisation and Development at Oxford University. From 2001 to 2006 he was at the World Bank, first as Director of Policy and then as Vice President. Previously, he was advisor to President Mandela and Chief Executive of the Development Bank of Southern Africa. He has been knighted by the French Government. Professor Goldin has published over fifty articles and eighteen books, including Exceptional People: How Migration Shaped our World and Will Define our Future, Globalization for Development: Meeting New Challenges, Divided Nations: Why global governance is failing and what we can do about it. He is the editor of Is the Planet Full?.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Is the planet full? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBanning Sterling makes a lot of cents for the NBADiscussing proprietary estoppel: promises and principlesJustice, revenge, and the law after Osama bin Laden

Related StoriesBanning Sterling makes a lot of cents for the NBADiscussing proprietary estoppel: promises and principlesJustice, revenge, and the law after Osama bin Laden

What do Otis Redding and Roberto Carlos have in common?

Soul’s latest incarnation comes in the guise of St. Paul and the Broken Bones. St. Paul is not really a saint. He is Paul Janeway of a new band that is hot on the rise. When you listen to him sing it evokes memories of a time past. But the most impressive part is that he does not look the part. People wonder how someone who looks nothing like Otis Redding can sound just like him. So how is it that this Drew Carey look-a-like ended up sounding so soulful? The answer comes from his early childhood.

Janeway grew up hearing gospel music and went to church on Sundays. His parents made a conscious decision to not allow him to hear anything but gospel and soul music. Church also contained quite a bit of gospel. He sung to a number of records and was immersed in this genre of music. He continued in his life and was actually almost ready to graduate from college when the opportunity to sing appeared once again. His band began to receive praise for their singing and the rest is history.

Like Paul Janeway, I also grew up with a childhood music that I would come to rediscover many years later. During my childhood summer trips to Mexico, I would often listen to music. One of the most famous pop singers in Mexico was Roberto Carlos, a native from the northeastern part of Brazil. He had some success in Brazil but nothing like the huge following he had in Latin America, where his accent sounded exotic in Spanish sung songs.

On one of our record hunting excursions in the Mission District in San Francisco my dad found a record that looked just like the one I had at home, except that the cover was white not pink — Portuguese version of the record I already had. My curiosity piqued, I began to listen to these songs and soon enough I was singing them with a very thick Spanish accent. I probably sung to the record for about a year or two before I grew older and took on other musical interests.

That very thick Spanish accent remained for me when I took Portuguese as a college student and it did not go away during my first few months in Brazil. However, over time the thick accent disappeared entirely and I came to speak with the accent of a Paulista, as those from Sao Paulo, Brazil’s economic capital are called.

Many years later I decided to sing a Brazilian lullaby from that Roberto Carlos album to my son Nikolas. And the day I sung it my accent in Portuguese stood in strong contrast to the Paulista that I had grown accustomed to as an adult. I realized that I sounded like a northeastern Brazilian, the same accent that Roberto Carlos had sung with in my childhood. All those years later, the early memory of that song had persisted and it surprised me when it came out. Like Paul Janeway, my exposure to an early set of sounds had created a vocal imprint that reappeared many years later.

People often ask if earlier is better. Well, there is one case where this is almost always true and it has to do with our accent in a language. So if you want to sound like Otis Redding or Roberto Carlos it is better to start working on it earlier in life.

Arturo Hernandez is currently Professor of Psychology and Director of the Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience graduate program at the University of Houston. He is the author of The Bilingual Brain. His major research interest is in the neural underpinnings of bilingual language processing and second language acquisition in children and adults. He has used a variety of neuroimaging methods as well as behavioral techniques to investigate these phenomena which have been published in a number of peer reviewed journal articles. His research is currently funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development. You can follow him on Twitter @DrAEHernandez.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Young boy removing headphones giving thumbs up sign. © stu99 via iStockphoto.

The post What do Otis Redding and Roberto Carlos have in common? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for April 2014Why nobody dreams of being a professorJustice, revenge, and the law after Osama bin Laden

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for April 2014Why nobody dreams of being a professorJustice, revenge, and the law after Osama bin Laden

Ukraine and the fall of the UN system

Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula and its continuing military pressure on Ukraine demonstrates that the United Nations-centered system of international law has failed. The pressing question is not whether Russia has violated norms against aggression — it has — but how the United States and its allies should respond in a way that will strengthen the international system.

It should be clear that Russia has violated the UN Charter’s restrictions on the use of force. It has resorted to “the use of force against the territorial integrity” and “political independence” of Ukraine in violation of Article 2(4) of the Charter’s founding principles. Russia has trampled on the fundamental norm that the United States and its allies have built since the end of World War II: that nations cannot use force to change borders unilaterally.

Like the League of Nations in the interwar period, the current system of collective security has failed to maintain international peace and security in the face of great power politics. According to widely-shared understandings of the UN Charter, nations can use force only in their self-defense or when authorized by the Security Council. Great powers with permanent vetoes on the Security Council (the United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia, and China) can always block formal efforts to respond to their own uses of force. Hence, the United Nations remains as powerless now as when Vladimir Putin ordered the 2008 invasion of Georgia.

Perevalne, Ukraine – March 4, 2014: Russian soldier guarding an Ukrainian military base near Simferopol city. The Russian military forces invaded Ukrainian Crimea peninsula on February 28, 2014. © AndreyKrav via iStockphoto

The United Nations and its rules have not reduced the level of conflict between the great powers. That doesn’t mean there has not been a steep drop in conflict, despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. From 1945 to the present, deaths due to great power wars have fallen to a level never seen under the modern nation-state system. Collective security, however, is not the agent of this “Long Peace,” as diplomatic historian John Lewis Gaddis has called it. Rather, the deterrent of nuclear weapons and stable superpower competition reduced conflict during the Cold War. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the United States has continued to supply the global public goods of security and free trade on its own. Democratic nations’ commitment to maintaining that liberal international order, not the collective security of the UN Charter, has kept peace among the great powers.

As someone who worked in the Bush administration during the 2003 Iraq War, I am struck by today’s absence of criticism for Russia’s violations of international law and its effective neutering of the United Nations. About a decade ago, criticism of the United States reached unprecedented heights for its failure to win a second Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force. The United States and its allies claimed that it already had authority from Iraq’s refusals to obey its obligations at the end of the 1991 Gulf War and its continuing threat to regional peace. Some of the United States’ closest European allies, such as France and Germany, violently disagreed — although these nations seem to urge compromise today with Russia. Even though the United States went to war without Security Council authorization, it sought to build a legal case in support.

UN rules only constrain democracies that value the rule of law, while autocracies seem little troubled by legal niceties. Paralysis continues to afflict the democratic response to the invasion of Ukraine. The United States responded to the invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea with the symbolic measures of sanctioning a few members of Vladimir Putin’s inner circle, kicking Moscow out of the G-8, and halting NATO-US military cooperation. Russian officials mocked the United States and raised the price of natural gas sold to Ukraine, an implicit warning to other European nations that depend on Russian natural gas. The Russian and US stock markets sighed with relief that no serious economic disruptions would follow.

Now Russian intelligence agencies are apparently fomenting unrest in eastern Ukraine and Russian troops have massed on the border. It should be clear that Putin sees Russia’s relationship with the Western democracies as one of competition, not cooperation. Putin has used the goal of restoring Russia’s great power status to win popularity at home. He has never ridden so high in domestic opinion polls as now. One response, in keeping with international law, should be to remove Russia from a position of superpower equality, which would only recognize Russia’s steep decline in military capability, its shrinking population, and its crumbling economy (which now relies on commodity prices for growth).

The United States could take the first step by terminating treaties with Russia that treat the former superpower as a current one. It can send a clear signal by withdrawing from the New START treaty, which placed both the United States and Russian nuclear arsenals under the same limits. There is no reason to impose the same ceiling of 1,550 nuclear warheads on Russia, which can no longer afford to project power beyond its region, and the United States, which has a world-wide network of alliances and broader responsibilities to ensure international stability.

Next, the United States could restore the anti-ballistic missile defense systems in Eastern Europe. Concerned about Iran’s push for ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons, the Bush administration had begun the process for deploying advanced ABM systems in Poland and the Czech Republic. As part of its effort to reset relations with Russia, the Obama administration canceled the program without any reciprocal benefits from Moscow or Iran. Re-deploying the missile defense systems would provide an important signal of American support for its NATO allies, especially those on the front lines with Russia, and raise the costs on Russia if it seeks to keep pace.

Another point where the White House should downgrade Russia’s status is in Syria. After threatening to bomb the Assad regime for using chemical weapons on the rebels, the United States leapt for a Russian to jointly oversee the destruction of Syria’s chemical arsenal. Bashar Assad has taken advantage of the withdrawal of American threats to seize the momentum in the civil war, backed up by Russian and Iranian support. The United States should not consider Russia an equal and joint partner on any matter, but certainly not on whether to allow the Assad regime and Iran to continue to destabilize the Middle East.

President Obama might even undertake a longer-lasting and more effective blow against Russia’s claims to great power status: ejecting Russia from the United Nations Security Council. Along with China, Russia has used its veto to act as the defense attorney for oppressive regimes throughout the world. Of course, the United States cannot amend the UN Charter to remove Russia from the Security Council. But it can develop an alternative to the Security Council, which has become an obstacle to the prevention of harms to international security and global human welfare. The United States could establish a new Concert of Democracies to take up the responsibility for international peace, which would pointedly exclude autocracies like Russia and China. Approval by such a Concert, made up of the world’s democracies, would convey greater legitimacy for military force and would signal that nation’s that resort to aggression to seize territory and keep their populations oppressed will not have a voice in the world’s councils.

John Yoo is Emanuel Heller Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley and a Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of Point of Attack: Preventive War, International Law, and Global Welfare (Oxford University Press, 2014), and co-author (with Julian Ku) of Taming Globalization: International Law, the U.S. Constitution, and the New World Order (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ukraine and the fall of the UN system appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe ‘internal’ enlargement of the European Union – is it possible?Felon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacyASIL/ILA 2014 retrospective

Related StoriesThe ‘internal’ enlargement of the European Union – is it possible?Felon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacyASIL/ILA 2014 retrospective

May 2, 2014

Justice, revenge, and the law after Osama bin Laden

On 2 May 2011, as news spread that a US Navy SEAL team had killed Osama bin Laden, Americans across the country erupted in spontaneous celebrations. Cameras showed the world images of jubilant crowds in Washington, DC and at New York City’s Ground Zero, reveling in the long-awaited payback against America’s nemesis. With bin Laden’s death, nearly ten years after the fall of the Twin Towers, a conflict-weary nation had its revenge. Many now expected closure to the trauma of 9/11 and the costly, decade-long “war on terror.”

But would Americans find the closure they sought in bin Laden’s demise? A new psychological study by international researchers indicates that some haven’t. According to it, many Americans indeed reported feeling that the killing of bin Laden was “vicarious revenge” for the victims of the 9/11 attacks and that justice had been served. These respondents were not just satisfied with bin Laden’s death itself, but were especially pleased that American forces — not accident, natural causes, or allies — had finally gotten him. Interestingly, however, the study concluded that those who expressed these sentiments the strongest desired further retribution against any others deemed somehow responsible for those September atrocities. So, three years on, bin Laden’s killing has not wholly slaked the collective thirst for revenge. This study’s findings suggest that the “long decade” after 9/11 has an additional psychological component that goes beyond the themes discussed by that volume’s contributors. If this is so, the changes in law occurring over this transformative period could be manifestations not just of a pervasive fear of another attack, but of a latent, still aggressive revanchism.

Flag-waving in Times Square on the night Osama bin Laden killed. Photo by Josh Pesavento. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Thus, while public attitudes towards the “war on terror” continue to shift, it remains uncertain just how they relate to the significant, long-term legal developments brought about by that conflict. In the years immediately after 2001 — alongside the military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan — the United States and Britain, in particular, introduced controversial counter-terrorism measures as part of a transnational effort to fight the unconventional threat of terrorism, prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and reassert national security interests in a globalized world where the nation-state had suddenly lost its monopoly on highly destructive, political violence. While these challenges were clear after 9/11, the best means of tackling them were not — especially in ways compatible with existing norms of liberal democracy, such as a respect for constitutional governance, the rule of law, and human rights. Extreme, often covert measures like military detention, torture, and extraordinary rendition directly challenged and raised doubts about our commitments to these fundamental principles. While the worst practices have since come to an end, other controversial, if less dramatic, counter-terrorism measures remain in effect. Preventive restrictions on liberty, use of secret courtroom evidence, drone strikes, and widespread surveillance, for example, are just some of the national security powers that have taken root over this long decade. Once touted by politicians as necessary but temporary, such powers now appear to be permanent with no sign of rollback. By and large, the public has accepted and sometimes welcomed many of these strategies for defeating terrorism, even as its skepticism towards government security policies has grown.

At this point, it might be too simplistic to say that these legal changes persist because the “war on terror” also does; to do so is to imagine that the pre-9/11 world can somehow be recaptured, that we remain in a suspended state of exception from the normal, and that this conflict with terrorism still has a definite, if yet un-seeable, end. Sadly, as the aftermath of Osama bin Laden’s death shows, this is all probably untrue. The threat of terrorism is likely inextricable from the globalized world in which we now live and the increasing securitization of our democracies belie a return to liberal norms as once understood. Military withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan signal an end neither to political instability nor insecurity in the region. Al Qaeda and Islamists still call for jihad against the West three years after the fall of bin Laden, their martyred standard-bearer. Nor does it seem that the fires of revenge for 9/11 have yet gone cold in us since his killing; if those coals still smolder — as researchers claim they do — then we risk embracing a new age of perpetual conflict and suspicion. In this age, neither victory nor justice will be achievable, but what we were fighting for will have been forever lost.

David Jenkins is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Copenhagen. He holds a JD from Washington & Lee School of Law and a Doctor of Civil Law degree from the McGill University Institute of Comparative Law. Along with Amanda Jacobsen and Anders Henriksen he is the Editor of The Long Decade: How 9/11 Changed the Law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Justice, revenge, and the law after Osama bin Laden appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFelon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacyWindow into the last unknown place in New York CityThe ‘internal’ enlargement of the European Union – is it possible?

Related StoriesFelon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacyWindow into the last unknown place in New York CityThe ‘internal’ enlargement of the European Union – is it possible?

The 9/11 memorial and the Aeneid: misappropriation or sincere sentiment?

The National September 11 Memorial Museum will be opened in a few weeks. On the otherwise starkly bare wall at the entrance is a 60-foot-long inscription in 15-inch letters made from steel salvaged from the twin towers: NO DAY SHALL ERASE YOU FROM THE MEMORY OF TIME. This noble sentiment is a quotation from Virgil’s Aeneid, one of mankind’s highest literary achievements, but its appropriateness has been questioned. In the context of the Aeneid, Virgil is commemorating a homosexual pair of warriors killed while making a bloody surprise attack on their sleeping enemies’ camp. Three years ago, an article in the New York Times suggested that “anyone troubling to take even a cursory glance at the quotation’s context will find the choice offers neither instruction nor solace.” But the museum was unmoved by such objections, and its director has recently defended the choice, asserting, perhaps rather cryptically, that the quotation characterizes the “museum’s overall commemorative context.”

It is unfortunate that this controversy has arisen, especially since so few people nowadays know about the context of the quote in the Aeneid. Those who lost family members or friends in the attacks should not have their thoughts and feelings distracted in this way. The sentiments expressed on national monuments aim to be strongly and unambiguously assertive of a view held by the whole community, but perhaps they are inherently vulnerable to controversial interpretations. Ideally, of course, such quotations should resonate more deeply than the meaning of the actual words, but would it not be best to accept the obviously sincere intentions of the museum’s committee and let the matter drop?

A religion reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

A religion reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Statistics and big data

By David J. Hand

Nowadays it appears impossible to open a newspaper or switch on the television without hearing about “big data”. Big data, it sometimes seems, will provide answers to all the world’s problems. Management consulting company McKinsey, for example, promises “a tremendous wave of innovation, productivity, and growth … all driven by big data”.

An alien observer visiting the Earth might think it represents a major scientific breakthrough. Google Trends shows references to the phrase bobbing along at about one per week until 2011, at which point there began a dramatic, steep, and almost linear increase in references to the phrase. It’s as if no one had thought of it until 2011. Which is odd because data mining, the technology of extracting valuable, useful, or interesting information from large data sets, has been around for some 20 years. And statistics, which lies at the heart of all of this, has been around as a formal discipline for a century or more.

Or perhaps it’s not so odd. If you look back to the beginning of data mining, you find a very similar media enthusiasm for the advances it was going to bring, the breakthroughs in understanding, the sudden discoveries, the deep insights. In fact it almost looks as if we have been here before. All of this leads one to suspect that there’s less to the big data enthusiasm than meets the eye. That it’s not so much a sudden change in our technical abilities as a sudden media recognition of what data scientists, and especially statisticians, are capable.

Of course, I’m not saying that the increasing size of data sets does not lead to promising new opportunities – though I would question whether it’s the “large” that really matters as much as the novelty of the data sets. The tremendous economic impact of GPS data (estimated to be $150-270bn per year), retail transaction data, or genomic and bioinformatics data arise not from the size of these data sets, but from the fact that they provide new kinds of information. And while it’s true that a massive mountain of data needed to be explored to detect the Higgs boson, the core aspect was the nature of the data rather than its amount.

Moreover, if I’m honest, I also have to admit that it’s not solely statistics which leads to the extraction of value from these massive data sets. Often it’s a combination of statistical inferential methods (e.g. determining an accurate geographical location from satellite signals) along with data manipulation algorithms for search, matching, sorting and so on. How these two aspects are balanced depends on the particular application. Locating a shop which stocks that out of print book is less of an inferential statistical problem and more of a search issue. Determining the riskiness of a company seeking a loan owes little to search but much to statistics.

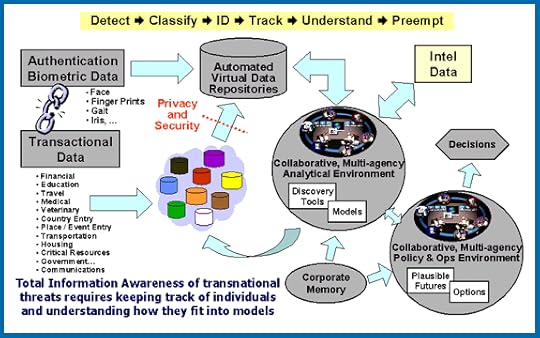

Diagram of Total Information Awareness system designed by the Information Awareness Office

Some time after the phrase “data mining” hit the media, it suffered a backlash. Predictably enough, much of this was based around privacy concerns. A paradigmatic illustration was the Total Information Awareness project in the United States. Its basic aim was to search for suspicious behaviour patterns within vast amounts of personal data, to identify individuals likely to commit crimes, especially terrorist offences. It included data on web browsing, credit card transactions, driving licences, court records, passport details, and so on. After concerns were raised, it was suspended in 2003 (though it is claimed that the software continued to be used by various agencies). As will be evident from recent events, concerns about the security agencies monitoring of the public continues.

The key question is whether proponents of the huge potential of big data and its allied notion of open data are learning from the past. Recent media concern in the UK about merging of family doctor records with hospital records, leading to a six-month delay in the launch of the project, illustrates the danger. Properly informed debate about the promise and the risks is vital.

Technology is amoral — neither intrinsically moral nor immoral. Morality lies in the hands of those who wield it. This is as true of big data technology as it is of nuclear technology and biotechnology. It is abundantly clear — if only from the examples we have already seen — that massive data sets do hold substantial promise for enhancing the well-being of mankind, but we must be aware of the risks. A suitable balance must be struck.

It’s also important to note that the mere existence of huge data files is of itself of no benefit to anyone. For these data sets to be beneficial, it’s necessary to be able to use the data to build models, to estimate effect sizes, to determine if an observed effect should be regarded as mere chance variation, to be sure it’s not a data quality issue, and so on. That is, statistical skills are critical to making use of the big data resources. In just the same way that vast underground oil reserves were useless without the technology to turn them into motive power, so the vast collections of data are useless without the technology to analyse them. Or, as I sometimes put it, people don’t want data, what they want are answers. And statistics provides the tools for finding those answers.

David J. Hand is Professor of Statistics at Imperial College, London and author of Statistics: A Very Short Introduction

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook. Subscribe to on Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only mathematics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Image credit: Diagram of Total Information Awareness system designed by the Information Awareness Office. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Statistics and big data appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesKerry On? What does the future hold for the Israeli-Palestinian peace process?Very short talksWriting as technology

Related StoriesKerry On? What does the future hold for the Israeli-Palestinian peace process?Very short talksWriting as technology

May 1, 2014

Window into the last unknown place in New York City

New York City, five boroughs boasting nine million people occupying an ever-expanding concrete jungle. The industrial hand has touched almost every inch of the city, leaving even the parks over manicured and uncomfortably structured. There is, however, a lesser known corner that has been uncharacteristically left to regress to its natural state. North Brother Island, a small sliver of land situated off the southern coast of the Bronx, once housed Riverside Hospital, veteran housing, and ultimately a drug rehabilitation center for recovering heroin addicts. In the 1960s the island, once full with New Yorkers, became deserted and nature has been slowly swallowing the remaining structures ever since. Christopher Payne, the photographer behind North Brother Island: The Last Unknown Place in New York City, was able to access the otherwise prohibited to the public island, and document the incredible phenomenon of the gradual destruction of man’s artificial structures.

Tuberculosis Pavilion, Spring

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

St. John by-the-sea Church

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Classroom, Service Building

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Old Coal House

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Library Books in a Male Dormitory

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

View of Manhattan Dusk, High Tide

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

North Brother Island: The Last Unknown Place in New York City: Photographs by Christopher Payne, A History by Randall Mason, and Essay by Robert Sullivan (A Fordham University Press Publication). Christopher Payne, a photographer based in New York City, specializes in the documentation of America’s vanishing architecture and industrial landscape. Trained as an architect, he has a natural interest in how things are purposefully designed and constructed, and how they work. Randall Mason is Associate Professor and Chair of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design. He worked previously at the Getty Conservation Institute, University of Maryland, and Rhode Island School of Design. Robert Sullivan is the author of numerous books, including The Meadowlands: WildernessAdventures at the Edge of a City; Rats: Observations on the History and Habitat of the City’s Most Unwanted Inhabitants; The Thoreau You Don’t Know: The Father of Nature Writers on the Importance of Cities, Finance, and Fooling Around; A Whale Hunt, and, most recently, My American Revolution. His stories and essays have been published in magazines such asNew York, The New Yorker, and A Public Space. He is a contributing editor to Vogue.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Window into the last unknown place in New York City appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIllustrating a graphic history: Mendoza the JewOxford University Press during World War IThe Illyrian bid for legitimacy

Related StoriesIllustrating a graphic history: Mendoza the JewOxford University Press during World War IThe Illyrian bid for legitimacy

Pauline Hall recalls her early years and how her teaching career began

I spent my first seven years living in Amen Court in the City of London, 100 metres from the northwest corner of St Paul’s Cathedral. I still have vivid memories of this time including recollections of lavish children’s parties given by Dean Inge (the so-called Gloomy Dean) for the cathedral choristers, hearing the call of the cats’ meat man who fed the rat-catching office cats, and the daily round of the lamplighter who tolerated the ‘help’ of a seven year-old assistant.

St. Paul’s Cathedral, London by Mark Fosh. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Then my family moved to Yorkshire where I had my first piano lessons. My teacher was Isobel Purdon who I now realize was a first-rate (if eccentric) musician. She knitted throughout lessons but still managed to hear all my mistakes, and I remember seeing her on her way to the Stranraer ferry (probably 200 miles away) with the neck of her double bass sticking out of the roof of her Austin 7. At music festivals she would conduct the school orchestra with a knitting needle; very embarrassing for the young orchestra members but it didn’t stop us winning more often than not.

On leaving school I studied piano and violin at The Royal Academy of Music. It was war time and buzz bombs were falling regularly over central London. We often had to dive under tables as the air raid warnings sounded–one notable occasion was right in the middle of my first violin exam.

After graduating, I embarked on my teaching career. After a year teaching very young children I felt the lack of inspirational music for this age group and so began to write a piano method which was logical, well-paced, and at the same time attractive and enjoyable. Producing a simple tutor for young children that addresses all these needs is a challenge, but as I was already a teacher I had the opportunity to learn on the job, so to speak, and all the pieces were tried and tested. As a piano teacher, a mother of three, and the wife of a busy doctor, time was scarce and my first drafts were written sitting at the ironing-board. Those initial sketches grew into the Piano Time series, a method used by many thousands of teachers and pupils across the globe today.

Tarantella

Click here to view the embedded video.

Dinosaurs’ Bedtime March

Click here to view the embedded video.

On Parade

Click here to view the embedded video.

Playful Plesiosaurs

Click here to view the embedded video.

At this point I would like to mention that however dedicated the piano teacher is, and however rewarding their teaching career, there will be times when it can seem like drudgery. The late Philip Cranmer, who had a long and distinguished career as a teacher, once put an interesting proposition. Are you a piano teacher and have you ever taught Für Elise? Here is Philip Cranmer’s proposition:

“Let there be a teacher who has taught the piano for 40 years on an average for 44 weeks in each year. And at any time during that period let there be one of that teacher’s pupils learning Für Elise, playing it through twice at each lesson. Then the teacher will have heard the E/Sharp seesaw 180,000 times. The actual figure arrived at by multiplying out is 179,520, but the extra 480 takes account of all the times the pupil has played one too many because he has miscounted the beat.”

Although there are moments of drudgery, the rewards of introducing young pupils to the infinite joy of music making must make this one of the most satisfying and fulfilling of all careers.

Pauline Hall is the author of Piano Time, Oxford University Press’s award-winning series for young pianists. Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the United States by Peters Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Pauline Hall recalls her early years and how her teaching career began appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCreative ways to perform your music: tips for music students10 facts about the saxophone and its playersHasidic drag in American modern dance

Related StoriesCreative ways to perform your music: tips for music students10 facts about the saxophone and its playersHasidic drag in American modern dance

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers