Oxford University Press's Blog, page 813

May 11, 2014

Unknown facts about five great Hollywood directors

Today, 11 May, marks the anniversary of the founding of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1927. It wouldn’t be until 1928 until the award selection and nomination process was established, but this elite group of actors, directors, writers, technicians, and producers were leaders in the early film industry.

As a throwback to old Hollywood, we’ve rounded up five of our favorite American classic film directors from the American National Biography who have been recognized by the Academy as iconic. Whose style is your favorite?

Billy Wilder

Described as: “Witty, with a devilish sense of humor.” It has been said of Wilder films that audiences are never allowed to believe that all will be well ever after; they are presented with flawed people who will continue to struggle.

Best known for: Sunset Boulevard (1950), Sabrina (1954), Some Like It Hot (1959), The Apartment (1960)

Most underrated movie: Witness for the Prosecution (1957) a suspense thriller that pays tribute to Alfred Hitchcock

You may be surprised to learn that: “In his 20s, Wilder wrote numerous scenarios for Berlin’s silent-film industry, and his skill at dancing landed him a stint as a hired dance partner for older women. Wilder made the most of his years in Berlin, seeking out the company of prominent writers and artists like Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, George Grosz, Fritz Lang, Hermann Hesse, and Erich Maria Remarque, whom he saw daily at a celebrated bohemian hangout, the Romanisches Café.”

Oscar Nominations for Best Director: 8

Oscar Wins for Best Director: 2

Studio publicity photo of Billy Wilder and Gloria Swanson, circa 1950. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Ford

Described as: An artist. As John Wayne said “When he pointed that camera, he was painting with it.” Ford’s films were characterized by a strong artistic vision and frequently contained panoramas of magnificent outdoor settings that rendered the human actors almost insignificant.

Best known for: Stagecoach (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941), The Searchers (1956)

Most underrated movie: They Were Expendable (1945)

You may be surprised to learn that: “Throughout his career Ford tended to work with the same group of people again and again, as actors, writers, stagehands, and cameramen. He was known for his non-ostentatious dress, and he frequently had both a drink and a cigar with him on the set. He wore a black patch over one eye, which had been injured in an accident during the 1940s.”

Oscar Nominations for Best Director: 5

Oscar Wins for Best Director: 4

Director John Ford, who was also a Rear Admiral in the Navy Reserve, 1952. US Navy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Frank Capra

Described as: “Hollywood’s most sought-after director of the 1930s.” He is cited as establishing the screwball comedy as a genre, though his subsequent films, focused on more serious social or historical issues, and revolved around a formula: “an honest and idealistic hero encounters problems from corrupt men and institutions but ultimately prevails.”

Best known for: It Happened One Night (1934), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), It’s a Wonderful Life (1947)

Most underrated movie: Meet John Doe (1941)—produced with an independent filmmaker, after a dispute with the Hollywood studios about directors having artistic control over their work

You may be surprised to learn that: The Christmas classic It’s a Wonderful Life was Capra’s personal favorite, although it was initially unpopular with both critics and the public.

Oscar Nominations for Best Director: 6

Oscar Wins for Best Director: 3

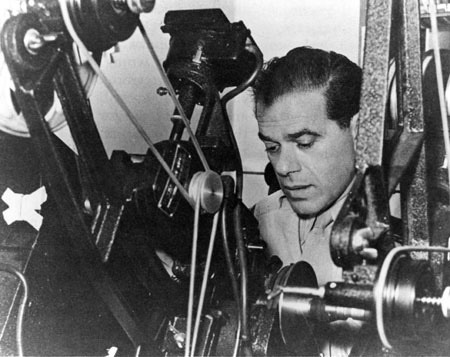

Frank Capra cuts Army film as a Signal Corps Reserve major during World War II, circa 1943. US Army. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Wyler

Described as: “Having a sympathetic approach to performance and an ability to create focused, dramatic moments.” He was praised for his careful handling of potentially incendiary themes and characters.

Best known for: Wuthering Heights (1939), The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), Roman Holiday (1953), Ben-Hur (1959) Funny Girl (1968)

Most underrated movie: The Children’s Hour (1961)

You may be surprised to learn that: With the United States in WWII in 1942, Wyler volunteered to make films for the armed forces. As an army major (later, lieutenant colonel), he produced two 16mm color films under combat conditions, serving as one of his own cinematographers (he ended the war permanently deaf in one ear as a result). The more notable of the two, Memphis Belle (1944), documented a B-17 bomber’s twenty-fifth and final mission over Germany

Oscar Nominations for Best Director: 12

Oscar Wins for Best Director: 3

Movie poster for The Heiress (1949). CC BY 2.0 via Nesster Flickr.

Robert Altman

Described as: “Idiosyncratic” and “iconoclastic”. His directorial style is known for its episodic storytelling, overlapping dialogue, and frequent improvisation.

Best known for: M*A*S*H (1970), Nashville (1975) and, more recently, The Player (1992)

Most underrated movie: Gosford Park (2001)

You may be surprised to learn that: The mellowness of A Prairie Home Companion may have reflected Altman’s recognition and final acceptance of mortality. Already suffering from cancer at the time of its release, he had been in precarious health since undergoing a heart transplant a decade earlier

Oscar Nominations for Best Director: 5

Oscar Wins for Best Director: 0 (But M*A*S*H was recognized for best screenplay)

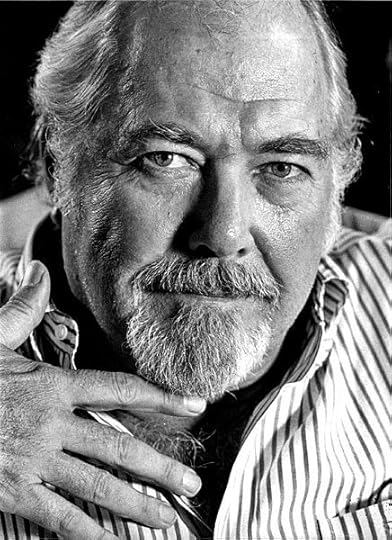

Publicity photo of Robert Altman, AP News, 1983. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Discover the lives of more than 18,700 men and women – from all eras and walks of life – who have influenced American history and culture in the acclaimed American National Biography Online. To supplement the thousands of biographies, many of which feature an image or illustration, Oxford is proud to announce a partnership with the Smithsonian that makes nearly 100 portraits from the National Portrait Gallery available to ANB users.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Unknown facts about five great Hollywood directors appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive facts about Dame Ethel SmythWriting a graphic history: Mendoza the JewGetting to know Sir Philip Sidney

Related StoriesFive facts about Dame Ethel SmythWriting a graphic history: Mendoza the JewGetting to know Sir Philip Sidney

Helping yourself to emotional health

The concept of psychological self-help, whether it is online, the traditional book, or the newer smartphone app, is one that elicits divided reactions. On the one hand, self-help is often the butt of jokes. Think Bridget Jones’s Diary, the comedy book and film about a single woman in her 30s, a self-confessed self-help devotee who consults numerous tomes in her pursuit to lose weight, get a man, and be happy. On the other hand, self-help is enormously popular – the sheer number of self-help resources consumed every year suggests that many of us like the idea of getting assistance with life’s problems in an easy, accessible, and low-cost way.

Psychological self-help resources are available for a whole range of topics, from general areas like happiness and self-esteem, to highly specific problem-focused topics such as coping with post-traumatic stress after a car accident, or parenting a child with Asperger’s syndrome. Some of the most popular include those that aim to help people manage anxiety, high stress, and depression — conditions that will affect approximately one in two people at some time in their life. But with so many self-help resources available, in both paper and digital form, it is worth reflecting on a few key questions. Does self-help for emotional health work? What should consumers look for when choosing self-help resources? And, in an age of increasing demand on health services, what role can self-help play in keeping our population well?

The short answer to the first question is “yes”. There are now many carefully conducted, scientific studies that show that people can learn to be less anxious, depressed, and stressed with the assistance of self-help materials. Much of this work has used printed books to deliver self-help advice, while some of the more recent research is based on Internet programs, and some very new work is beginning to assess the value of information delivered through smartphones. In all cases the effects are much the same. People who read and apply information they learn through self-help materials are consistently less anxious, stressed, or depressed than people in comparison groups.

Evidently, quality self-help tools can deliver enormous benefits. But how does the consumer best choose which self-help resources to use? If one does an Internet search of the words “stress,” “anxiety,” or “depression,” paired with the term “self-help,” thousands of options come up. What steps can the consumer take to make sure they are accessing quality and evidence-based advice?

Mediate Tapasya Dhyana. Photo by Lisa.davis. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

One simple way to narrow the options is to check whether the website, application, or book author is linked to a reputable institution. Do some background research into the qualifications and experience of the author/s, and check that these are relevant to the topic area. Keep a healthy dose of scepticism for “cure all” or “quick fix” claims, as well as those websites that encourage you to buy expensive products. Reputable self-help resources will acknowledge the limitations of their approach, and won’t claim that they can help everyone. Finally, check to see whether the advice has been tried and tested in well-conducted research. Unless it has, you are really just getting the author’s personal opinion. And don’t just take their word for it. Properly conducted scientific research is almost always published in reputable scientific journals where it is carefully checked by other scientists.

The emergence of quality and evidence-based self-help has important implications for broad scale health systems, as well as individuals. One example of this can be found in the United Kingdom. In 2006 a leading British economist, Richard Layard, released an influential report called, “The Depression Report”. Why would an economist write a report on depression? Well, because depression, like any other health condition, costs society money. Obviously, treatment incurs a cost. But, as Layard argues, the costs of not treating depression are vastly greater. When people feel depressed or anxious, they take more time off work. They don’t concentrate as well, and are less productive when they go to work. Where the symptoms are severe, they are often unable to work at all, relying on savings, family support, or welfare benefits to survive. So, Layard crunched the numbers and found that leaving depressed and anxious people untreated costs the economy 20 times the amount it would cost to provide an effective treatment service.

So what does this have to do with self-help? Well, the UK government paid attention to these figures, and decided to roll out a vast, nationwide project called “Improving Access to Psychological Therapies”. They made a commitment to providing effective help for depressed and anxious people living in the United Kingdom. The system they adopted is widely known as Stepped Care. Stepped Care means that people with mild to moderate depression, and those with anxiety, are given low intensity interventions first. They are generally not sent straight to a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist; they are not put on medication or not taken into an expensive treatment facility. Rather, they are often first given quality information and tools to help them manage their own symptoms… essentially, self-help. After they have tried this option, the person is reassessed by a health professional. Those that are still struggling with anxiety or depression are then given a higher intensity intervention, such as face-to-face psychological therapy and/or medication. But many do not need this higher intensity treatment. For a significant proportion, quality self-help is enough to get them feeling and functioning well.

This Stepped Care process has several advantages. First, more people are able to access the service, including those in rural and remote areas. Secondly, people are not “over-treated” – that is, they are not given more intense treatment than they require. Finally, the money saved when a proportion of people get better with self-help can then be spent on higher intensity interventions for those who really need them. The Stepped Care process recognises that different people have different needs, and that a one-size-fits all approach may not be the best one.

Clearly self-help does have a role to play when it comes to emotional health. When good resources are used, they can deliver great benefits to individual consumers and the broader community. So, the next time you encounter self-help, don’t just dismiss it as a Bridget Jones style joke. Take some time to evaluate its quality. It may help more than you think.

Sarah Perini, MA, is Director of the Emotional Health Clinic at Macquarie University in Australia, where she teaches post-graduate psychology students how to conduct effective treatment. She is an experienced clinical psychologist who has treated hundreds of stressed and anxious patients. She has also worked in a range of clinics and hospitals and has published several academic articles. She is the co-author of 10 Steps to Mastering Stress: A Lifestyle Approach, Updated Edition, with David H. Barlow, Ph.D. Ronald M. Rapee, Ph.D.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Helping yourself to emotional health appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive tips for getting into clinical psychology trainingQ&A with Susan Llewelyn and David MurphySome highlights of the BPS conference 2014 Birmingham

Related StoriesFive tips for getting into clinical psychology trainingQ&A with Susan Llewelyn and David MurphySome highlights of the BPS conference 2014 Birmingham

May 10, 2014

Reflections on World War I

As we approach the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the First World War, it’s important taking a look back at the momentous event that forever changed the course of world history. Here, Sir Hew Strachan, editor of The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, examines the importance of commemorating the Great War and how perspectives on the war have shifted and changed over the last 100 years.

What might we learn from the centenary commemoration of World War I?

Click here to view the embedded video.

What is the difference between commemorating the 50th anniversary and the centenary of the World War I?

Click here to view the embedded video.

What is the difference between the First and Second World Wars?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sir Hew Strachan, Chichele is a Professor of the History of War at the University of Oxford, Commonwealth War Graves Commissioner, and a Trustee of the Imperial War Museum. He also serves on the British, Scottish, and French national committees advising on the centenary of the First World War. He is the editor of The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. The first volume of his planned trilogy on the First World War, To Arms, was published in 2001, and in 2003 he was the historian behind the 10-part TV series, The First World War.

Visit the US ‘World War I: Commemorating the Centennial’ page or UK ‘First World War Centenary’ page to discover specially commissioned contributions from our expert authors, free resources from our world-class products, book lists, and exclusive archival materials that provide depth, perspective and insight into the Great War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Reflections on World War I appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOxford University Press during World War IA publisher before wartimeWriting a graphic history: Mendoza the Jew

Related StoriesOxford University Press during World War IA publisher before wartimeWriting a graphic history: Mendoza the Jew

May 9, 2014

Crowdfunding for oral history projects

OHR Editors’ Note: In April, we put out a call for oral history bloggers. We originally planned to run submissions starting this summer. However, we were so excited by the response that we decided to kick things off a bit early. Enjoy the first of many volunteer posts to come!

By Shanna Farrell

The cocktail is an American invention and was defined in 1806 as “a stimulating liquor composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters.” Cocktail culture took root on the West Coast around the Gold Rush; access to a specific set of spirits and ingredients dictated by trade roots, geography, and agriculture helped shape the West Coast cocktail in particular. We in UC Berkeley’s Regional Oral History Office (ROHO) are beginning a new oral history project about the legacy of the West Coast cocktail, which will explore the cultivation of the West Coast cocktail’s identity and how it has contributed to the return of bartending as a respectable profession. We consider documenting bar culture important, especially because of the current explosion of cocktail bars around the country. However, due to the nature of the topic, this project won’t qualify for academic or grant funding. ROHO has instead had to look for non-traditional funding opportunities, which has presented us with a set of complications that we had yet to experience.

The people involved in the bar and spirit industry have a unique perspective on the ways in which American life has unfolded and intersected around cocktails. When I first began developing this project I reached out to famed bartender Dale DeGroff, cocktail historian and journalist David Wondrich, and PUNCH co-founders Talia Baiocchi and Leslie Pariseau for their insight in identifying interview themes and potential narrators. They are all now serving as our project advisors. We conducted pilot interviews with three Bay Area-based female bartenders and recorded four hours with Wondrich himself. Even early on, themes of community, labor, gender, ethnicity, geography, culinary influence, storytelling and myth making, the dissemination of information, state laws and regulations, bartender/customer relationships, and popular culture have emerged. We hope to interview at least thirty people, including bar owners, bartenders, craft spirit distillers, and cocktail historians, to further unpack these topics.

As the project lead, I’ve encountered various issues planning and rolling out the project, especially because of funding. In an attempt to involve the cocktail community, garner interest in the project, and draw people into ROHO’s archives, we decided to raise money through crowdfunding. We’ve been working for several months to get administrative approval, build out partnerships and out network, choose engaging content from our pilot interviews, and build a project website. This has taken a lot of time and though we are optimistic about the success of the campaign, using this funding mechanism is a risk. We are up against a hard deadline to deliver a large amount of content at campaign’s launch on 3 June 2014 and during its following five-week run.

Crowdfunding campaigns usually have a short video (two to three minutes) explaining the concept of the project, the need for financial support, and establishing its legitimacy. We also need to deliver regular updates throughout the five weeks of the campaign to keep our audience interested in the project. This requires pulling clips from interviews that illustrate the project’s exciting topics and themes. For example, we have one story about how Wondrich discovered that pre-Prohibition cocktail recipes called for Holland gin, which is essentially flavored whiskey not readily available in the United States until the past few years, instead of London dry gin, which is flavored vodka and has dominated the domestic gin market for the past twenty years. This proved to be a revelation for Wondrich while writing the hugely influential book Imbibe!: From Absinthe Cocktail to Whiskey Smash, a Salute in Stories and Drinks to “Professor” Jerry Thomas, Pioneer of the American Bar (Perigee Trade, 2007).

Once the campaign is over we will need to share completed interviews with the public as soon as we can to demonstrate that we are using contributions for the intended purpose; this is critical for the project’s reputation if we plan to use this fundraising method in the future. Content will have to be continuously created and sent to narrators for quick approval, which can be difficult due to schedules, file compatibility, and familiarity with technological mediums. Getting clips to narrators in a timely fashion has necessitated our use of free cloud-based technology, such as SoundCloud and Vimeo. Thus far, we have created private tracks on SoundCloud and private channels on Vimeo to share the files in a fast and easily accessible way.

This project will serve as a test for ROHO in many ways: will we be able to produce content, get it to our narrators for approval, and share it publically on a timeline that keeps our audience engaged? Will long-term use of various media outlets like SoundCloud and Vimeo prove successful? Will funders feel satisfied with the level of accessibility of the interviews? Time will tell how the project and its various set of challenges will unfold, but we hope to use digital age techniques to work around the challenges which crowdfunding has presented.

Shanna Farrell is an oral historian in UC Berkeley’s Regional Oral History Office. She holds an MA in Oral History from Columbia University, an Interdisciplinary MA in Humanities and Social Thought from New York University, and a BA in Music from Northeastern University. Aside from her current project on the legacy of the West Coast cocktail, her studies have focused on environmental justice issues in communities impacted by water pollution. Her work includes a community history of the Hudson River, a documentary audio piece entitled “Hydraulic Fracturing: An Oral History” that explored the complexity of issues involved in drilling for natural gas, a study that examined the local politics of “Superfunding” the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, New York, and a landscape study of a changing neighborhood in South Brooklyn.

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the OHR editors.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow their latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: a midori sour on ledge over looking Coronado bay and San Diego. © AndrewHelwich via iStockphoto.

The post Crowdfunding for oral history projects appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchangeSuperstition and self-governanceTrauma happens, so what can we do about it?

Related Stories‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchangeSuperstition and self-governanceTrauma happens, so what can we do about it?

Five tips for getting into clinical psychology training

Clinical psychologists help a huge range of people, of all ages, with an increasing number of mental health problems. Here are my top tips for getting into clinical psychology training.

(1) Firstly, and probably most importantly, when you are at University, do your best consistently in your Psychology degree. Relevant experience can always be gained later down the line, but you only have a limited time to work on your degree and then your marks stay with you. Your degree transcript containing your marks from every module is used in selection.

(2) Once your degree is in the bag then you need to get relevant experience. Not just to put on your application form but to make sure that working in this field is really what you want to do. Getting a paid assistant psychologist posts is very competitive; in fact nowadays it is actually more competitive than getting onto a doctoral training course. If you can’t get a traditional assistant psychologist post, there is a wide range of other types of relevant clinical experience; nursing assistant posts and/or some voluntary work are also a useful first step on the ladder.

(3) When you do come to filling in your application form, try and communicate something about yourself, what you have learned, and what skills you have developed through your clinical experience and also in your other activities. Think of ways to set yourself apart from other applicants.

(4) Choose your referees wisely and support them. It’s true that you can’t write the references but you can choose who you ask and help your referee by providing them with information about what the courses are looking for, particularly if they are not used to writing forms for clinical psychology. It’s such a shame when you see a great form accompanied by a clinical reference from someone who has only recently met the applicant or who can’t really comment on their clinical work, or an academic reference from someone who appears to have forgotten all about the applicant. If this information is lacking then it makes it very difficult for a course to know whether or not you meet the selection criteria.

(5) Reflect and review. I’ve heard a lot of people say they were told not to even think about applying for Clinical Psychology training because of how competitive it is. Nevertheless, each year several hundred applicants do get places, so it is certainly possible. You may well not get a place on your first attempt but don’t let that put you off. However, you also need to be realistic and reflect on your progress. It’s true that you generally need to have 1-2 years of relevant experience to maximize your chances but if, after a number of attempts you find you still haven’t been successful, it is probably time to rethink. There are plenty of other ways in which you can apply your psychology degree within healthcare and also within many other fields.

Whatever way it turns out I wish you all the best!

David Murphy is the Joint Course Director of the University of Oxford Clinical Psychology Doctoral Training Programme, and co-editor of What is Clinical Psychology? He trained as a clinical psychologist at the Institute of Psychiatry in London and worked for over 20 years as a full-time clinical psychologist in acute hospital settings within the National Health Service before taking up his current position.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post Five tips for getting into clinical psychology training appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSome highlights of the BPS conference 2014 BirminghamWhat do Otis Redding and Roberto Carlos have in common?Casting a last spell: After Skeat and Bradley

Related StoriesSome highlights of the BPS conference 2014 BirminghamWhat do Otis Redding and Roberto Carlos have in common?Casting a last spell: After Skeat and Bradley

Tinderbox drenched in vodka: alcohol and revolution in Ukraine

If Ukraine is a volatile tinderbox of political instability, the situation in its Russian-speaking east is even more dangerous: a tinderbox drenched in vodka. Aspirations and allegiances aside, the most striking contrast between the pro-European protests on Kyiv’s Maidan square and the pro-Russian, anti-Maidan protests in the east is not simply that the latter tend to be armed and forcibly occupying government buildings (rather than protesting outside of them), but also that they have a higher likelihood of being drunk and disorderly, making the situation dramatically more volatile.

Especially amidst revolution, vodka and AK-47s don’t mix, especially in Russia and Ukraine.

Lost amidst all the talk of ethnic, linguistic, and cultural ties between Ukrainians and Russians at play in the Donbass area of southeastern Ukraine, the culture of alcoholism seems almost too cliche to garner mention; yet perhaps it explains all too well the different political trajectories in Ukraine’s east and west.

By Andreas Argirakis, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Today, both Russia and Ukraine consistently rank atop of the world’s heaviest drinking nations. Unlike moderate wine- and beer-drinking countries, they also share a “traditional vodka drinking culture,” marked by heavy intoxication, binge drinking of hard liquor, and a general acceptance of the public drunkenness that results. These patterns are not hard-wired into the DNA of Russians or Ukrainians. Instead, they are the result of centuries of autocratic rule under the Russian empire and its Soviet successor, both of which used vodka to debauch society at the expense of the state. Unfortunately, the revolutionary experiences that both the Russians and Ukrainians shared as part of those empires—most notably in 1917 and 1991—were heavily influenced by alcohol, in conditions that bear eerie similarities to the present circumstances in Ukraine.

* * *

Already three years into total war, and suffering widespread desertions from the front, in early 1917 Tsar Nicholas II was rapidly losing control of his country. Hearing word that his military would no longer follow orders—which included firing on its own unarmed civilians protesting in the streets—Nicholas hurried from the front line back to Petrograd to reassert control. He never made it. His train was stopped by mutinous soldiers and railway workers, who forced the tsar’s abdication in the February Revolution of 1917.

With the police in hiding or defying orders, Petrograd mobs laid siege to police stations and government ministries. Armed gangs looted homes, shops, and liquor stores. Some commandeered motor cars—which they promptly crashed, since few knew how to drive, especially through a haze of pilfered vodka. Hundreds died, and thousands more were injured in the February Revolution, yet there was a sense that things could have been much worse, were it not for the tsar’s prohibition decree at the outset of the war. “If vodka could have been found in plenty, the revolution could easily have had a terrible ending.”

With the tsar gone, political power lay with a weak Provisional Government led by Aleksandr Kerensky, while de facto power lay with the self-organized councils of workers and soldiers who manned the streets. With more demoralizing drubbings at the front, continued economic chaos, and the inability to broadcast power much beyond the walls of the Winter Palace, by October 1917, virtually no one was willing to defend the Provisional Government against the growing power of Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

The night of 24-25 October 1917 was relatively quiet, as the Bolsheviks discreetly took control of strategic assets: government offices, train stations, and telegraph posts. The Winter Palace itself was stormed by a relatively small and disorganized group of revolutionaries, many of whom bypassed the priceless artworks and looted instead the imperial wine cellars. Loud pops punctuated the Petrograd night—more often champagne corks than gunfire—while the snows snows were stained red: not with blood, but with burgundy wine.

Understanding that vodka was the means by which the old capitalist order enriched itself while keeping the worker drunk and subservient, Lenin and the early Bolsheviks were steadfast prohibitionists. Their equation of alcohol with “counterrevolution” was only reinforced by a series of drunken riots and pogroms in the streets of the capitol, which threatened their own tenuous hold on power. “What would you have?” the exasperated People’s Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatoly Lunacharsky, told a reporter. “The whole of Petrograd is drunk!”

“The bourgeoisie perpetuates the most evil crimes,” Lenin wrote to Felix Dzerzhinsky in December 1917, “bribing the cast-offs and dregs of society, getting them drunk for pogroms.” Lenin ordered that Dzerzhinsky’s newly formed All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combatting Counterrevolution and Sabotage—the “Cheka”—confront the vodka threat by any means necessary. All alcohol stores were to become property of the state, bootleggers were to be shot on sight, and wine warehouses were to be blown up with dynamite. And they were.

“The very nearest future will be a period of heroic struggle with alcohol,” proclaimed Leon Trotsky, the firebrand ideologue and founder of the Red Army. “If we don’t stamp out alcoholism, then we will drink up socialism and drink up the October Revolution.” Red Guard and Cheka detachments sworn to be “sober and loyal to the revolution” fought pitched street battles against unruly mobs and drunken military detachment—with heavy casualties on both sides—not only in in Petrograd and Moscow, but Saratov, Tomsk, Nizhny Novgorod, and beyond. Russia paid a heavy price for its drunkenness and disorder in the throes of revolution. Other legacies were even more nefarious: Dzerzhinsky’s Cheka security force was subsequently rebranded the NKVD and later the KGB—the secret police force complicit in the darkest days of Soviet totalitarianism.

* * *

While prohibition in the Soviet Union died with Vladimir Lenin, the KGB and the Soviet dictatorship endured another seven decades. While 1989 saw the peaceful end of the Cold War and the euphoric toppling of the Berlin Wall, the communist autocracy lurched ahead for another two years in the Soviet Union itself. Amid economic chaos and political dissatisfaction, the liberation of the East European satellite states emboldened nationalists in the Soviet Baltic, Caucasus, Ukrainian, and even Russian republics. With pressures for national self-determination threatening to tear the Soviet Union apart, Mikhail Gorbachev proposed a new treaty that would remake the USSR into something of a confederation, bequeathing sovereignty to the autonomous national republics. For Soviet hardliners this was too much to bear.

On 19 August 1991—the day before the new treaty—a hard-line “State Emergency Committee” led by Vice President Gennady Yanayev staged a coup d’etat: imposing martial law and putting Gorbachev under house arrest at his Crimean retreat.

The previous night, both Yanayev and Prime Minister Valentin Pavlov had been out drinking with friends when they were summoned to the Kremlin by KGB chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov, who set the plan in motion. “Yanayev wavered and reached out for the bottle,” Gorbachev later wrote in his Memoirs. Along with the other conspirators, it is doubtful that Yanayev was sober at any time during the bungled three-day coup.

Co-conspirator Defense Minister Dmitry Yazov later confirmed that not only was Yanayev “quite drunk,” but so too were other plotters: KGB head Kryuchkov, Interior Minister Boris Pugo, and even Yazov himself. After chasing his blood pressure medications with alcohol, Prime Minister Pavlov had to be pulled unconscious from the bathroom. After that, “I saw him two or three times, and each time he was dead drunk,” Yazov testified. “I think he was doing this purposefully, to get out of the game.”

Drunk or not, the conspirators somehow forgot to neutralize their primary rival: the populist Boris Yeltsin, who’d just been elected president of the Russian republic—the largest and most important of the fifteen republics that constituted the USSR.

Yeltsin—whose own intemperance later became the stuff of legend—rallied his supporters at the legislature of the Russian Republic (the “White House”), where protesters were busy constructing protective barricades. Nonviolent protestors convinced the Soviet tank troops surrounding the White House to defect and instead defend Yeltsin and the Russian republic. In an iconic moment captured by the global news media, Yeltsin—defying threats of sniper fire—courageously clamored atop a tank turret to address the crowd, denouncing the coup and calling for a general strike. In those delicate moments when the whole country teetered on the brink of civil war, Yeltsin sternly rebuked offers of vodka, claiming “there was no time for a drink” at this moment of supreme crisis.

Yeltsin’s sober command stood in stark contrast to the coup leaders in the Kremlin—just a few miles to the east—where the irresolute putschists confronted a restive media at an ill-fated press conference. “A sniffling Gennady Yanayev, his face swollen by fatigue and alcohol, had a tough time fielding the combative questions,” recalled Russian history professor Donald J. Raleigh. “His trembling hands and quivering voice conveyed an image of impotence, mediocrity, and falsehood; he appeared a caricature of the quintessential, boozed-up Party functionary from the Brezhnev era.” That’s precisely who he was.

In the face of growing opposition and a military unwilling to follow orders, the coup collapsed on 21 August. Rather than surrender to the police, Interior Minister Pugo chose to shoot his wife before turning the gun on himself. Others sought refuge in the bottle: Prime Minister Pavlov was drunk when the authorities came to arrest him, “but this was no simple intoxication,” attested Kremlin physician Dmitry Sakharov, “He was at the point of hysteria.” When the incoherent Yanayev was carried out of his Kremlin office—its floor strewn with empty bottles—he was too drunk to even recognize his one-time comrades who had come to arrest him. Hours later, when President Gorbachev returned safely to Moscow, he’d effectively landed in a different country. Thanks to Yeltsin’s leadership in bringing down the hardline coup, legitimacy lay with Russia and the other union republics rather than Gorbachev’s USSR. The subsequent legal dissolution of the Soviet Union was only a formality.

* * *

What does this drunken history lesson have to do with the ongoing crisis in Ukraine? Quite a bit, actually. Both 1917 and 1991 demonstrate how political protests instantly become more complex and dangerous when mixed with a culture of extreme inebriation and general apathy toward public drunkenness. Moreover, given their shared imperial/Soviet cultural inheritance (including alcohol abuse) Ukraine is only slightly less immune from these revolutionary dynamics than is Russia.

While much ado has been made of Ukraine’s (arguably overblown) ethnic and linguistic divisions between the pro-EU, Ukrainian west and the pro-Russian east; there are palpable demographic divisions between east and west Ukraine. While on the whole, Ukraine’s health indices are lower than its European neighbors, the demographic situation deteriorates as you move from west to east across the country. Ukraine’s western provinces—which spent less time under the sway of the Russian/Soviet empires—generally have higher rates of fertility, lower rates of mortality, and higher average life expectancy than those eastern regions that have longer history of Russian domination. Perhaps not surprisingly, the eastern Donbass regions exhibiting the highest mortality and lowest life expectancy are also by far the hardest-drinking regions of an already hard-drinking nation, with cultural acceptance of inebriation most aligned with the Russian “norm” to their east. It may be only a rough approximation, but the further east you go in Ukraine, the more dangerous this revolutionary stage becomes.

So is it any surprise that—in Ukraine’s ongoing struggles between east and west—we should see different approaches to vodka, and the potential for destabilization that it presents first in Kyiv, then in Donetsk?

For context: in 2004, a horribly rigged election favoring the pro-Russian, Donetsk-based Viktor Yanukovych prompted a backlash of popular opposition, which culminated with massive protests on Kyiv’s Independence Square, or Maidan Nezalezhnosti. Building an encampment on the Maidan, the nonviolent protesters—often in excess of 100,000—endured the brutal winter to rally for free elections. Relenting to the popular demands of this so-called “Orange Revolution,” new elections swept in triumphant, pro-European factions. Unfortunately for Ukraine’s lackluster economy, these once allied political factions squabbled and split, while succumbing to Ukraine’s chronic corruption. The split in the pro-European bloc opened the door for the once-vanquished Yanukovych to emerge victorious in the freely-contested presidential election of 2010.

While in the long term the Orange Revolution may have ended in failure, in the short term, it provided perhaps the best exemplar of an effective, nonviolent, post-Soviet political protest, not the least because alcohol was explicitly forbidden in the sprawling tent cities as a bulwark against the easily foreseen drunken disturbances that were sure to result.

When the pro-European protesters again took to the Maidan against Yanukovych’s corrupt presidency in November 2013, their self-organized security forces put a premium on maintaining tranquility through sobriety. “If someone is drunk, he is out of here,” explained Evgeni Dudchenko, a security volunteer on the square, “Alcohol is forbidden here, and we don’t need any hooligans.”

That the Euromaidan protests—like those a decade earlier—remained peaceful for as long as they did can partly be attributed to this enforced sobriety. Even when the movement turned violent in the face of ever-tighter government crackdowns, culminating in the indefensible slaughter of civilian protesters by government gunmen on 22 February, there is a sense that—as with Russia’s February of 1917—Ukraine’s February Revolution could have been much, much worse. A mob of inebriate protesters meeting a drunken security battalion armed to the teeth could have multiplied the carnage many times over.

Following the government’s spilling the blood if its own people on that fateful day, the Ukrainian parliament impeached President Yanukovych, who by that time had already fled the country. Filling the leadership void in Kyiv was a weak interim government that is effectively unable to broadcast political power across the country, as evidenced by Russia’s subsequent non-invasion invasion of Crimea, and the destabilization of the Donbass and the Russian-speaking east.

Even after Yanukovych had been toppled and the regime’s police and military forces had melted away, the major confrontations—and even shootouts—between competing, armed Maidan factions had their roots in drunken disagreements. Still, at the very least, in the midst of a potentially revolutionary situation, the protesters on the Maidan acknowledged, confronted, and mitigated the potential destabilization from vodka, making the protests there far less dangerous than they could have been.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the more recent armed occupations in Ukraine’s heavy-drinking Donbass region that constitute the “anti-Maidan” movement. Beginning 6 April 2014 in the eastern cities of Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Luhansk, small numbers of violent activists—armed with everything from homemade clubs to firearms—clashed with local police, stormed and occupied regional administration buildings and other strategic installations, demanding greater political autonomy from Kyiv, and in some cases outright annexation by Russia in a repeat of the scenario in Crimea.

These protests differed not only in terms of aims and means, but also temperament. In Kharkiv, local residents complained that the protesters were not local, but rather that they were drunken hooligans dispatched from Russia to infiltrate and destabilize their town and intimidate their residents. Ukrainian special forces succeeded in clearing the separatists there, but not before they vandalized and torched the place, leaving behind a mess of garbage and empty liquor bottles. Yet the most noteworthy confrontations came further south in Donetsk—the former stronghold of ousted president Yanukovych.

In Donetsk, violent protesters fought their way into the local administration building, and displaced the Ukrainian flag with the black, blue and red tricolor of their newly declared “People’s Republic of Donetsk.” In a scene eerily reminiscent of the accounts of the drunken State Emergency Committee back in 1991, the organizers of this self-proclaimed mini-state in Donetsk appear to have done so while staggeringly drunk.

From the first clashes with police outside the building, many in the pro-Russian mob were drunk, in stark contrast to the sobriety of the Maidan. The party, it seems, continued once the separatists occupied the building, where thirty protesters were found completely drunk, and empty bottles of vodka, whisky, and tequila littered the stairways to the meeting rooms where the independent Donets Republic was proclaimed.

Manning the barricades outside the occupied Donetsk City Hall: armed protesters wandered freely, “while people lit fires in the street and drank beer and vodka.” Both outside the building and within, secessionists accosted the media while visibly drunk.

In his series of incredible reports from the region, Vice News reporter Simon Ostrovsky noted that at the beginning of “day two of the People’s Republic of Donetsk, it smells like there’s been a huge frat party here.” In something of a throwback to the press conference of the shaky State Emergency Committee, Ostrovsky then interviewed the leader of the Donetsk “Coordination Council” Vadim Chernyakov, who slurred through his speech, visibly hung over and slurring his speech—even admitting as much, apologizing for his “headache” as his eyes rolled back in his head.

It didn’t take long for the separatists to re-learn the historical lesson that alcohol and guns don’t mix in a revolutionary scenario: after recovering from their hangovers, the leadership decreed that the defenders of the building should dump all of their vodka and “follow a prohibition law” to maintain some semblance of order in such tumultuous times.

Still, in dispelling the false equivalence between the Maidan and anti-Maidan forces, the cultural context cannot be overlooked. “Unlike the pro-Europe protest movement in Kiev,” reports the New York Times, “the stirrings in Donetsk have so far attracted little support from the middle class and seem dominated by pensioners nostalgic for the Soviet Union and angry, and often drunk, young men.”

Whether or not discipline holds in Donetsk and throughout the Ukrainian east is yet to be seen, as Kyiv tries—in fits and starts—to reassert control over violent Russian-minded secessionists and local pro-autonomy protesters. Yet the task of all sides looking to bring stability to the region is made infinitely more difficult by the unpredictability generated by the region’s alcoholic inheritance. Recent events have demonstrated as much, as Vasily Krutov—the head of Kyiv’s counter-terrorism operation in the Donetsk region—was almost torn apart by a mob of Kramatorsk locals, some who were visibly intoxicated. Even more troubling—in one of his last dispatches before being kidnapped by the pro-Russian separatists in Slovyansk—Ostrovsky chronicled how a handful of the most drunken and agitated anti-Maidan protesters stumbled onto the Kramatorsk airbase, manned by heavily armed and understandably jittery soldiers. Such drunken provocation could easily have ended in tragedy—one that could have provoked even greater backlash locally, and even a pretext for greater Russian intervention in Ukraine.

The lamentable reality is that—in such times of revolutionary change and political crisis—we overlook that “cliche” of vodka only at our own peril.

Mark Lawrence Schrad is Assistant Professor of Political Science, Villanova University and author of Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Tinderbox drenched in vodka: alcohol and revolution in Ukraine appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUkraine and the fall of the UN systemCan we finally stop worrying about Europe?Putin in the mirror of history: Crimea, Russia, empire

Related StoriesUkraine and the fall of the UN systemCan we finally stop worrying about Europe?Putin in the mirror of history: Crimea, Russia, empire

Why literary genres matter

By William Allan

One of the most striking aspects of classical literature is its highly developed sense of genre. Of course, a literary work’s genre remains an important factor today. We too distinguish broad categories of poetry, prose, and drama, but also sub-genres (especially within the novel, now the most popular literary form) such as crime, romantic or historical fiction. We do the same in other creative media, such as film, with thrillers, horrors, westerns, and so on. But classical authors were arguably even more aware than writers of genre fiction are today what forms and conventions applied to the genre they were writing in. All ancient literary texts are written in a particular genre, such as epic, tragedy, or pastoral. This doesn’t mean that one genre can’t interact with another, and they often do, as in ‘tragic history’, that is, history written in the style of tragedy, as when Thucydides presents the Athenian empire’s disastrous attempt to conquer Sicily as a typically tragic story of hybris and ruin. Some modern theorists would argue that every text belongs to a genre and that it is impossible not to write in one: thus even those nifty writers who try to break free of convention and write the wackiest stuff are still caught up in ‘experimental’ literature. The invention of the major literary genres and their norms is the most significant effect of classical literature’s influence.

But what is a genre? The first thing to observe is that a genre is not a rigid mould which works must fit into, but a group of texts that share certain similarities – whether of form, performance context, or subject matter. For example, all the texts that make up the ancient genre of tragedy share certain ‘family resemblances’ (they are theatrical texts written in a particular poetic language, they reflect on human suffering, they show gods interacting with humans, and so on) that allow us to perceive them as a recognizable group. But although certain ‘core’ features characterize any given genre, the boundaries of each genre are fluid and are often breached for literary effect.

As can still be seen in modern literature and film, a genre comes with certain in-built codes, values, and expectations. It creates its own world, helping the author to communicate with the audience, as she deploys or disrupts generic expectations and so creates a variety of effects. Genres appeal to writers because they give a structure and something to build on, while they offer audiences the pleasure of the familiar and ingenious diversion from it. The best writers take what they need from the traditional form and then innovate, leaving their own imprint on the genre and changing it for future writers and audiences. In other words, genre is a source of dynamism and creativity, not a straitjacket, unless the writer is rubbish, i.e. unimaginative and unoriginal.

All ancient writers had an idea of who the top figures in their chosen genre were (Homer and Virgil in epic; Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides in tragedy, and so on), and their aim was to rival and outdo their predecessors. The key ancient terms for this process of interaction with the literary past are imitatio (‘imitation’) and aemulatio (‘competition’). ‘Imitation’ doesn’t mean slavish copying, but creative adaptation of the tradition; creative writing today still involves the reworking of previous literature, since writers are usually enthusiastic readers too. Of course, competing with the great writers of the past is a risky business – as Horace puts it, ‘Whoever strives to rival Pindar exposes himself to a flight as risky as that of Icarus’ (Odes 4.2.1-4, paraphrased) – but what characterizes the best writers of antiquity is their response to the great works of the past in the light of the present.

The central role of ‘imitation’ in classical literature also helps explain why ancient authors allude so frequently to other texts. With ‘the death of the author’ in postmodern thought, the wider term ‘intertextuality’ is now trendier than ‘allusion’, referring to the interconnections between texts, deliberate or not. Be that as it may, deliberate allusion is an important part of the writer’s meaning in classical literature, and the ideal reader of Virgil’s Aeneid, for example, an epic that draws on a variety of other genres (including tragedy, history, and love poetry, among others), will be able to appreciate how Virgil alludes to, and reworks, earlier texts in order to create his own meaning.

Mention of epic reminds us that classical literature is characterized by a hierarchy of genres, ranging from ‘high’ forms such as epic, tragedy, and history at one end through to ‘low’ forms such as comedy, satire, mime, and epigram at the other. ‘High’ and ‘low’ relate to how serious the subject matter is, how lofty the language, how dignified the tone, and so on. Many of the genres lower down on the hierarchy define themselves polemically in opposition to a higher form: thus writers of comedy, for example, poke fun at tragedy, presenting it as unrealistic and bombastic, in order to assert the value of their own work, while satire mocks the claims of epic and philosophy (among other genres) to offer meaningful guides to life. Finally, it is striking that some genres endure longer than others: Roman love elegy flourished for only half a century, while epic was always there, and always changing.

In conclusion, then, we can understand an ancient literary text properly only if we take into account where it comes in the evolution of its genre, and how it engages with and transforms the conventions it inherits. The same is true of our literature too, of course, not least because classical works, with their highly developed sense of genre, form the foundation of the Western literary tradition.

William Allan is McConnell Laing Fellow and Tutor in Classics at University College, Oxford. His publications include Classical Literature: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2014).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Theatrical masks of Tragedy and Comedy. Mosaic, Roman artwork, 2nd century CE. From the Baths of Decius on the Aventine Hill, Rome. Capitoline Museums. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Why literary genres matter appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow to write a classicThe 9/11 memorial and the Aeneid: misappropriation or sincere sentiment?Statistics and big data

Related StoriesHow to write a classicThe 9/11 memorial and the Aeneid: misappropriation or sincere sentiment?Statistics and big data

May 8, 2014

My democracy, which democracy?

I support democracy. I like to think I do so to the extent of willingness to fight and perhaps die for it. This is not so extravagant a claim, within living memory the men in my family were called upon to do exactly that.

Universal suffrage is consequently my birth-right, but what is it that I am being permitted to do with my vote, when the political parties have so adjusted the system to suit themselves?

In the coming elections for local councils and the European Parliament, two relatively recent changes have stripped away most of the choices voters had and given them to the political parties. The Local Government Act 2000 and the party list system, introduced for European elections in 1999, are both triumphs of management over content. Both shuffled power from an aggregate of the electors to a small number of people running the party machines.

When I first saw local government in action, as a junior reporter on a local paper, I felt admiration for the range of abilities and oratorical skill that leading councillors brought to their posts. They were people who not only worked unpaid, but often made real financial sacrifices in order to work for their locality. When I occasionally attend council meetings today I am struck by the poor quality of the debates, the inability to see the implications of policy beyond party advantage, the lack of intellectual rigour, the sheer irrelevance of most of this political process to the business of local government, which is now carried on by senior officers.

What happened in the interim? The Local Government Act 2000 did away with the old committee system that had run councils since 1835, through more than a century and a half of municipal progress. The government imposed a ‘leader and cabinet’ system. Active local democracy was ‘modernised’ into non-existence; only cabinet members now have any authority and even their role is merely advisory to the leader.

The leader appoints the cabinet; the rest of the councillors are supporters or impotent opponents. There is no political brake on the leader’s authority, but decisions can be criticised in retrospect by a ‘scrutiny committee.’ This is not local democracy but local autocracy.

Is it any wonder that people of quality are reluctant to come forward to be councillors when they have no influence except that can be garnered by toadying to the leader, who might then appoint them to the cabinet and put some money in their pockets? People of quality wanting to act in public affairs realise they could have more influence in pressure groups. Of course, there are still some meritorious councillors, just as under the old system there were some fools. My observation is that the balance has shifted and there are now fewer people of quality prepared to go through the system.

Voters were in fact given something of a choice over the introduction of the Local Government Act 2000: they could choose whether to have the directly elected mayor and cabinet system, or the leader and cabinet system. There was no option of retaining the tried and tested system of committees where every councillor had a voice. So it was a charade of a ballot where only votes in favour were requested and counted. This used to be called ‘guided democracy’ in east European countries.

As with every centralisation, those who already possessed power welcomed the developments of the Act with hands outstretched. It put more money into the system, gave senior officers more power (which, since it had to come from somewhere, meant commensurately less for elected representatives), paid councillors, and gave ever-increasing sums to cabinet members for special responsibilities.

In a few places the gimmick of directly elected leaders (confusingly referred to as mayors) was tried. The public were indifferent everywhere except London where candidates from both major parties have excelled as mayors, but London is more like a city state with a president than a municipal corporation. Elected mayors in four of thirty-two London boroughs have added to the cost of the process but contributed nothing to efficiency. Outside of London there are eleven directly elected mayors, with two other towns having tried but abandoned the system as an expensive flop. This local lack of democracy is one of the ways in which the system has become fragmented, the responsiveness of the elected moving further and further away from those they are supposed to represent and towards their party loyalty.

On a larger scale, there is the other election we face this month, for Members of the European Parliament, which has been entirely taken over by political parties. A system in which electors voted for a local MEP was replaced in 1999 by the European Party Elections Act with a party list system with the additionally unfriendly title of ‘closed list.’ That means voters can vote only for a party, and the first candidates on the list chosen by the party will get in — even if that person is heartily despised by their own supporters, so long as they are favoured by the party bosses.

This is not an arcane argument about supposed representation with no relevance to individuals. I have a property in Greece. I had a problem with the planning authorities there where I felt I was being discriminated against as a non-Greek. Contact my Member of the European Parliament, I thought. So who is that?

I found Greek MEPs with parties like the Popular Orthodox Rally or members of groupings such as the Nordic Green Left Confederation, but no member for the Dodecanese islands. After one and a half days of trying to make contact with people via the Internet, Brussels and party offices, I finally called a London MEP who had a Greek name so I supposed she might know something. She was in fact very helpful, but is this any way to run a representative democracy? I did not vote for this MEP, at best I might have voted for a party list on which she appeared somewhere.

In the UK we now have this party list system; single transferable votes (for directly elected mayors); the mixed member system for the Welsh assembly (don’t ask); regional proportional representation for the Scottish parliament and first past the post for general elections.

I still think I would still fight for democracy, but which democracy is that?

Jad Adams is an independent historian specializing in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He is a Research Fellow at the Institute of English, School of Advanced Study, University of London, and a Fellow of the Institute of Historical Research. His forthcoming book, Women and the Vote, is published by Oxford University Press and available from September 2014.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Westminster Bridge, Parliament House. Photo by Jiong Sheng, 25 September 2005. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post My democracy, which democracy? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUkraine and the fall of the UN systemDo immigrant immigration researchers know more?Prime Minister’s Questions

Related StoriesUkraine and the fall of the UN systemDo immigrant immigration researchers know more?Prime Minister’s Questions

Five facts about Dame Ethel Smyth

The 8th May marks the seventieth anniversary of the death of Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944), the pioneering composer and writer, at her home in Hook Heath, near Woking. In the course of her long and varied career, she composed six operas and an array of chamber, orchestral, and vocal works, challenging traditional notions of the place of women within music composition. In her later years she found a second calling as an author of auto/biographical and polemical writings, publishing ten books between 1919 and 1940.

Smyth led a fascinating and unconventional life. Having resolved at an early age to enter the music profession, she overcame opposition from her father (an army general) in order to enrol at the Leipzig Conservatorium in 1877. During her years in Continental Europe she came into contact with Brahms, Clara Schumann, Grieg, and Chaikovsky. Returning to England in the late 1880s, her compositions attracted much attention in the years and decades that followed, from influential figures including Empress Eugénie, Lady Mary Ponsonby, Queen Victoria, Princesse de Polignac, and, in the field of music, Thomas Beecham, Bruno Walter, Adrian Boult, Henry Wood, Donald Tovey, and George Bernard Shaw. She received honorary doctorates from the Universities of Durham and Oxford, and was awarded the DBE in 1922.

Ethel Smyth, 1908. Lewis Orchard Collection Ref.9180, courtesy of Surrey History Centre.

This intriguing artist has been a subject of my research for over a decade, leading to my article “Music and Literature: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and ‘The First Woman to Write an Opera’” recently published in The Musical Quarterly (itself a companion-piece to an article I published in another Oxford journal, Music & Letters, in 2004). My particular interest lies in Smyth’s relationship with the novelist Virginia Woolf (1882-1941), whom she befriended in 1930 and with whom she maintained a lively correspondence that provides many valuable insights into Smyth’s activities as memoirist and polemicist, and, more widely, into the differences between their respective disciplines.

Smyth may not have been the first ever woman to write an opera, as Woolf erroneously suggested in the quotation that inspired my article (that distinction goes to Francesca Caccini, over 250 years earlier). But she was nonetheless a pathbreaking individual in many different respects. To commemorate the anniversary of her passing, here follow five facts about Ethel Smyth, some well known, others less so, illustrating ways in which she made history in music, politics, and literature.

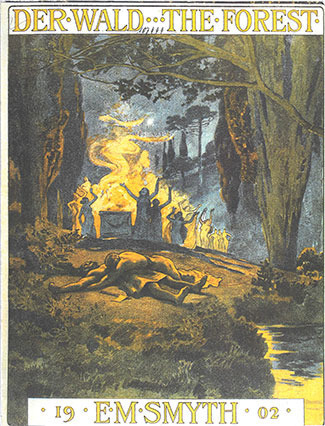

Front cover of Ethel Smyth Der Wald, 1902. Lewis Orchard Collection Ref.9180, courtesy of Surrey History Centre.

1. Smyth is the only woman composer to date to have presented an opera at The Met. The performances of her second opera, Der Wald (The Forest), on 11 and 20 March 1903 yield the only instance out of over 300 different works given at The Metropolitan Opera, New York City between October 1883 and July 2013 to have been composed by a woman. According to one contemporary account, the opera was attended by “one of the largest and most brilliant audiences” of the season, eliciting applause that “continued for ten or fifteen minutes, surpassing even the most generous for which the opera patrons are distinguished.”

2. Smyth withdrew one of her operas during its performance run in a move she believed to be “unique in the annals of Operatic History.” For the première of her third opera, Standrecht (The Wreckers), at the Neues Theater, Leipzig in November 1906, she stipulated that no revisions to the score should be made without her consent. However, she discovered the day before the dress rehearsal that Act III had been extensively cut, and her pleas for reinstatement of the excised material were in vain. In response, following the first performance she removed all of her music from the orchestra pit and took it to Prague, where the opera had already been accepted for performance — though this turned out to be a woefully under-rehearsed fiasco.

3. Smyth became a leading suffragette in the early 1910s. In September 1910 she met, and became enchanted by, Emmeline Pankhurst. She pledged to devote two years of her life to the women’s suffrage campaign, and a close friendship developed between the two women (Woolf even believed they had been lovers). Smyth’s work for the “Votes for Women” movement is reflected in much of the music she composed at that time, not least The March of the Women, which came to be adopted as the suffragette anthem. She was said to have once stormed into 10 Downing Street and hammered out the March on Prime Minister Asquith’s piano while the Cabinet was in session.

Image: Lewis Orchard Collection Ref.9180, courtesy of Surrey History Centre

4. Smyth served a jail sentence for her suffrage activity. She was one of some 200 women arrested on 4 March 1912 as a result of a co-ordinated window-smashing campaign across the West End of London, and was sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. Smyth had chosen to target the Berkeley Square home of the colonial secretary, Lewis Harcourt, in retaliation for a remark he had made along the lines that “if all women were as pretty and as wise as his own wife, [they] should have the vote tomorrow.” She recounted the episode on the BBC National Programme in 1937, in interview with the author Vera Brittain.

5. Smyth kept a series of dogs for over fifty years. Her first dog, given to her in 1888, was a St Bernard cross called Marco, who travelled everywhere with her. In 1901, a friend presented her with an Old English sheepdog puppy she named Pan, who became the first in the line of sheepdogs she successively numbered Pan II, Pan III, up to Pan VII. Her lesser-known book Inordinate (?) Affection: A Story for Dog Lovers (1936), a collected biography of some of her canine companions, stands alongside such classics as Virginia Woolf’s Flush and Jack London’s The Call of the Wild as famous examples of dogs in literature.

Christopher Wiley is Senior Lecturer in Music at the University of Surrey, UK. His research primarily examines musical biography and the intersections between music and literature. Other interests include music and gender studies, popular music studies, and music for television. He is author of “Music and Literature: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and ‘The First Woman to Write an Opera’” published in The Musical Quarterly. Follow Christopher Wiley on Twitter. Read his blog. He can also be found on Scoop.it!.

The Musical Quarterly, founded in 1915 by Oscar Sonneck, has long been cited as the premier scholarly musical journal in the United States. Over the years it has published the writings of many important composers and musicologists, including Aaron Copland, Arnold Schoenberg, Marc Blitzstein, Henry Cowell, and Camille Saint-Saens. The journal focuses on the merging areas in scholarship where much of the challenging new work in the study of music is being produced.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five facts about Dame Ethel Smyth appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSuperstition and self-governanceDo immigrant immigration researchers know more?‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchange

Related StoriesSuperstition and self-governanceDo immigrant immigration researchers know more?‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchange

Q&A with Susan Llewelyn and David Murphy

With the British Psychological Society Annual Conference underway, we checked in with Susan Llewelyn, Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Oxford, and David Murphy, Joint Course Director for Oxford Doctoral Course in Clinical Psychology. We spoke to the co-editors of What is Clinical Psychology? about psychosis, provision of care, and careers in clinical psychology.

When did you first become interested in clinical psychology?

Sue: When I was an undergraduate studying psychology, I realised clinical psychology was by far the most interesting aspect of psychology. I was particularly interested in psychosis and what “madness” was.

David: Although I covered aspects of mental health in my undergraduate degree, I don’t think I really decided to pursue clinical psychology as a career option until I began working as an assistant psychologist and saw the range of different roles for clinical psychologists in the NHS. I worked for a while in a residential centre for people with epilepsy and became fascinated with the relationship between the brain and behaviour.

What do you think has been the most important development in clinical psychology in the past 100 years?

Sue: Probably the articulation of the cognitive, or information processing model of human behaviour and emotion, to balance the biological or the psychodynamic.

David: Clinical psychology is still such a young discipline that almost all the developments were within the last 100 years and most within the last 50 years. I think the pioneering work in behaviour therapy by Vic Meyer and others, helped open up the notion that psychological therapy could be effective in severe and intractable psychiatric problems like OCD and really changed the role of the clinical psychologist.

What is the most pressing or controversial issue in clinical psychology right now?

Sue: How we can deliver high quality clinical psychology services to meet all the so far unmet need.

David: I agree with Sue, we know from epidemiological surveys that there are large numbers of people with mental health problems who don’t or cant access services. We need to be better at using the resources to provide the most effective and responsive services we can; this often means trying to intervene early.

How might your current research have an impact on the wider world?

Sue: I am not sure I can be that grandiose! But our work tries to show how psychologically grounded ideas can make a big difference in people’s lives, and how taking the psychological realm seriously can improve the nature of the health care that can be offered to people in distress.

David: I agree with Sue; hopefully reading about the applications of psychology in practice across a diverse range of settings might inspire the next generation of clinical psychologists to pursue what is quite a long and challenging path into the profession.

Which famous psychologist has been most influential to you?

Sue: My friend and colleague Professor Glenys Parry in Sheffield has helped me to understand two important areas of psychological functioning: first how broad social and political influences shape the psychological (particularly how social and political gender issues become internalised and intimately lived by individuals), and second, how both the insights of psychodynamic, interpersonal therapies and CBT therapies can be effective combined to maximise how much we can help people.

David: That’s a really tough one! I’ve been lucky enough to work with a number of really inspirational psychologists through my career to date and, of course, many psychologists I haven’t met have influenced me through their work. One person who stands out on a personal level to me is Padmal De Silva who was my clinical tutor during training in London. Padmal was an internationally renowned expert in an array of areas; obsessive compulsive disorder, sexual and marital therapy, post-traumatic stress and Buddhist psychology. One of the most intelligent people I have ever met, he was also one of the most kind and humble. He always seemed to have time for people, even us trainees, and was genuinely interested in what they had to say. I feel very privileged that now in Oxford I have responsibility for training the clinical psychologists of the future and I am fortunate to have Padmal and others as role-models to aspire to.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to specialize in your field?

Sue: Try to be open minded about ideas: you can gain insights about the human condition from so many places including the newspapers, politics, art and literature, and conversations with friends, as well as psychology textbooks.

David: Read my OUPblog post “Five top tips to getting into Clinical Psychology” tomorrow!

What do you see as being the future of research in your field in the next decade?

Sue: We may be able to track more carefully what are the important components of our interventions, so that we can tailor what we offer more precisely to our clients

David: Wow, there are no easy questions, are there! I think research in psychological therapies, at least, will need to be not only carried out with larger sample sizes with longer follow ups but also with very detailed analysis of individual factors and therapy process factors to really enable us to answer the question “what works for whom”.

If you weren’t teaching clinical psychology, what would you be doing?

Sue: Reading really beautifully written literature, and also walking with friends and family in the mountains

David: Learning about clinical psychology! I’ve always found teaching to be just a natural extension of learning and practicing, if I can pass on what I’ve learned to trainees then hopefully I will hopefully have contributed in some way to them going out and generating more knowledge and innovative practice. I do have a life outside Psychology though, and in that life I enjoy playing football (even though I’m still not very good at it) and travelling to new places with my family.

Susan Llewelyn is Professor of Clinical Psychology at Oxford University, and Senior Research Fellow, Harris Manchester College, Oxford. David Murphy is the Joint Course Director of the University of Oxford Clinical Psychology Doctoral Training Programme. They are co-editors of the new edition of What is Clinical Psychology?

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Teenage Girl Visits Female Doctor’s Office Suffering With Depression. © monkeybusinessimages via iStockphoto.

The post Q&A with Susan Llewelyn and David Murphy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat do Otis Redding and Roberto Carlos have in common?What is clinical reasoning?Nursing: a life or death matter

Related StoriesWhat do Otis Redding and Roberto Carlos have in common?What is clinical reasoning?Nursing: a life or death matter

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers