Oxford University Press's Blog, page 811

May 17, 2014

A different Noah, but the same God

Aronofsky’s Noah movie has aroused many criticisms for the ways it has rewritten the biblical story of the Flood. It is observed that not only has the movie added extra materials to, as well as removed original elements from, the biblical account, but more seriously it has also modified and darkened the character of Noah and even of God.

The degree by which the movie has adapted the biblical story and the characterisations of the characters has offended the religious and theological sensibilities of many who have watched the movie that others who haven’t watched it are reluctant or refuse to watch it.

In analyzing the rewriting of the biblical account, one can point out several factors involved: interpretation, elaboration, engagement with contemporary issues, exploration of certain biblical and theological issues, and dramatic representations.

The movie has faithfully followed the Bible by interpreting the Flood from a moralistic perspective. It has highlighted the violence of Cain’s descendents, especially in their brutal killing and devouring of animals.

By contrast, Noah’s family is depicted as herbivore, which is evidently based on the fact that the permission to eat animals was only given by God after the Flood in the biblical account. The emphasis the movie gives to this issue suggests that the producer intends to engage viewers on relevant issues such as food production and consumption in modern society.

Click here to view the embedded video.

There are a number of instances where the movie has creatively interpreted the Bible to make the Flood story more coherent, believable, or dramatic. For example, to connect the Flood with the creation, the movie has portrayed Noah dropping the magic seed (presumably brought from the Garden of Eden) in the barren soil. This instantly brought out an Eden-like eco-system, from which Noah drew resources to build his ark.

The movie also portrays six stone colossi–the Watchers (possibly based on the Nephilims in the Book of Genesis)–helping Noah and his family build the ark and defend them from the hostile people. Without such superhuman assistance, it would be difficult, in the view of the movie maker, to fathom how they could have achieved the task and have done so without interruption from the hostile people. Furthermore, the animals in the ark were put in hibernation mode under the effect of the herbal medicine in order to ensure that they would stay still and don’t have to devour each other.

The most salient divergence between the Bible and the movie is how Noah is characterised in relation to God and his family. This divergence starts to unfold in the movie when Noah obeyed God and only chose to take his three sons (Shem, Ham and Japheth), his wife, and their adopted daughter (Ila) into the ark (whereas in the biblical account, God commanded Noah to take his sons, his wife, and his sons’ wives with him, which Noah did).

This act of obedience leads to the following conflict between Noah and his family. Though Shem and Ila were in love, Ila was barren. As far as Noah could see, despite the family was spared from the Flood, without the ability to reproduce it (and the entire human race) would not be able to carry on. Ham, seized by the fear of not being able to have a spouse and children, approached Noah for solutions. Noah responded by saying that he trusted that God would provide. But facing reality, he acquiesced when Ham decided to go out to search for a wife.

Though the search seemed successful at first, the girl whom Ham planned to bring on board was caught in an animal trap and had to be abandoned in order for Noah and Ham to flee from the approaching crowd who tried to kill them. The resentment Ham harboured against Noah eventually led him to allow Tubal-Cain to remain hiding in the ark and even to conspire with the latter to kill his father as an act of revenge for abandoning his prospective wife. Clearly, this episode is a creative rewriting of the Flood story in an attempt to explain the obscure tension between Noah and Ham and his son Canaan, as in the Genesis.

Though the search seemed successful at first, the girl whom Ham planned to bring on board was caught in an animal trap and had to be abandoned in order for Noah and Ham to flee from the approaching crowd who tried to kill them. The resentment Ham harboured against Noah eventually led him to allow Tubal-Cain to remain hiding in the ark and even to conspire with the latter to kill his father as an act of revenge for abandoning his prospective wife. Clearly, this episode is a creative rewriting of the Flood story in an attempt to explain the obscure tension between Noah and Ham and his son Canaan, as in the Genesis.

As Ila’s barrenness was healed through the blessing of Noah’s grandfather Methuselahand she became pregnant through Shem, the movie shows another clash between Noah and his family. For Noah, having the offspring went against God’s will which seems to terminate the human race. As an act of obedience to God’s command, he tried to kill his two granddaughters Ila gave birth to, regardless of the bitter petition and opposition of the rest of the family. It was only in the last moment when he raised the knife over his granddaughters that his mind changed because his heart was suddenly full of love for them.

Some reviewers argue that Noah misinterpreted God’s will in the movie and became a cold-blooded monster and a religious fanatic. But those who are versed in the Book of Genesis would recognise that the movie is trying to explore a crucial theme in biblical religion: obedience by transporting the story of testing of Abraham into the story of Noah (though this merging has created some problem with the coherence of the movie).

Notice the parallel between Sarah and Ila who were barren at first and then were given the ability to conceive. And just like Isaac to Abraham, the two granddaughters were provided by God, presumably as prospective wives for Ham and Japheth, to extend the family line of Noah and the rest of humanity. As in God’s testing of Abraham, in the movie it seems that God’s testing of Noah’s obedience only concluded when Noah was just about to kill his granddaughters. Similar to the biblical account of the offering of Isaac, the movie tries to explore the extent by which one has to be willing to sacrifice in order to obey God’s will.

The fact that, unlike the biblical story of Abraham, there was no apparent divine voice to guide or command Noah makes the testing more real and acute. Though Noah didn’t end up killing his granddaughters, his relationship with his family was seriously damaged (a consequence which is not addressed in the biblical story of Abraham).

The fact that, unlike the biblical story of Abraham, there was no apparent divine voice to guide or command Noah makes the testing more real and acute. Though Noah didn’t end up killing his granddaughters, his relationship with his family was seriously damaged (a consequence which is not addressed in the biblical story of Abraham).

As a result of his alienation from his family, he resorted to alcoholism—a creative interpretation of the episode of Noah’s drunkenness after the Flood in the Book of Genesis. All of these prove the price or cost Noah was willing to, and indeed did pay for his radical obedience to God.

The innovative ways the Noah movie has rewritten the biblical Flood story may be new, and even disturbing, to many modern viewers. But for those who are acquainted with post-biblical traditions and interpretations, such style of rewriting biblical stories was common, especially during the Second Temple period (516 BC–AD 70), see James Kugel, Traditions of the Bible (1998). For example, in the Testament of Abraham (Recension A) , the biblical figure of Abraham was recharacterised in the light of Moses, Elijah and Elisha to address the theological issues of divine justice and mercy. The ways the Noah movie has adapted the Bible may be unfamiliar to the modern audience, but the central issue it addresses is fundamentally biblical (see also the teaching of Jesus on the cost of discipleship).

If the Noah in the movie is no longer the same Noah as found in the Bible it is because in the latter half of the movie he began to behave like Abraham; the God in the movie, however, remains the same.

This is the God who abhors sin and wickedness, who would purge corruption by drastic measures in order to preserve his creation and his chosen people, and who is ready to test the limits of the obedience of his followers in order, ultimately, not to harm, but to give them hope and a future.

Y. S. Chen is Research Fellow in Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Wolfson College, University of Oxford. His recent research focuses on the conceptual, literary and socio-political processes and mechanisms through which ancient Mesopotamian and biblical traditions related to the origins of the world and early world history developed. His monograph The Primeval Flood Catastrophe: Origins and Early Development in Mesopotamian Traditions was published through Oxford University Press (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Noah’s Ark By Sakotch. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) By FUJISHIMA Takeji (1867 – 1943). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post A different Noah, but the same God appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe American Noah: neolithic superhero“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to EuropeLittle triumphs of etymology: “pedigree”

Related StoriesThe American Noah: neolithic superhero“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to EuropeLittle triumphs of etymology: “pedigree”

Churchill, Hitler, and Stalin’s strategy in World War II

Today, 17 May, is Armed Forces Day in the United States, celebrating the service of military members to their country. To mark the occasion, we present a brief excerpt from Lawrence Freedman’s Strategy: A History.

While Churchill’s approach to purely military affairs could be impetuous, he had a natural grasp of coalition warfare. Coalitions were always going to be central to British strategy. The empire contributed significantly to the war effort in terms of men and materiel, and its special needs had to be accommodated. The United States had the unequivocal potential to tip the scales when a European confrontation reached a delicate stage. Almost immediately after taking office, Churchill saw that the only way to a satisfactory conclusion of the war was “to drag the United States in,” and this was thereafter at the center of his strategy. His predecessor Neville Chamberlain had not attempted to develop any rapport with President Franklin Roosevelt. Churchill began at once what turned into a regular and intense correspondence with Roosevelt, although so long as Britain’s position looked so parlous and American opinion remained so anti-war, little could be expected from Washington. His first letter was if anything desperate, warning of the consequences for American security of a British defeat. If Britain could hang on, something might turn American opinion. Churchill was even prepared to believe that this might happen if the country was invaded.

At the time, Hitler’s choices appeared more palatable and easier. German victories had confirmed his reputation as a military genius with unquestioned authority. Yet he recognized the difficulty of following the defeat of France with an invasion of Britain. A cross-channel invasion would be complicated and risky. There were also other options for getting Britain out of the war. The first was to push it out of the Mediterranean, further affecting its prestige and influence and interfering with its source of oil. Whether or not this would have had the desire effects, Hitler was wary of his regional partners – Mussolini’s Italy, Franco’s Spain, and Vichy France. They all disagreed with each other, and none could be considered reliable. Mussolini, for example, used German victories to move a reluctant country into war. He then demonstrated his independence from Hitler by launching a foolhardy invasion of Greece. This left him weakened and Hitler furious. Germany had to rescue the Italian position in Greece and then North Africa, leading to a major diversion of attention and resources from Hitler’s main project, the invasion of the Soviet Union.

US soldiers take cover under fire somewhere in Germany. US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

He considered a war with the Soviet Union to be not only inevitable but also the culmination of his ambitions, allowing him to establish German dominion over continental Europe and deal once and for all with the twin—and, in his eyes, closely related – threats of the Jews and Communism. If he was going to go to war with Russia anyway, it was best to do so while the country was still weak following Josef Stalin’s mass purges of the army and communist party in the 1930’s. A quick defeat of Russia would achieve Hitler’s essential objective and leave Britain truly isolated. But Hitler also had a view about how the war was likely to develop. Britain, he assumed, only resisted out of a hope that the Russians would join the war. Of course, without a quick win, Hitler faced the dreaded prospect of a war on two fronts –something good strategists were supposed to avoid—as well as increasing strain on national resources. He needed to conquer the Soviet Union to sustain the war and to gain access to food supplies and oil. With the Soviet Union defeated, he reasoned, Britain would realize that the game was up and seek terms. If Hitler had accepted that the Soviet Union could not be defeated, his only course would have been to seek a limited peace with Britain that would have matched neither the scale of his prior military achievements nor his pending political ambition.

Another reason for acting quickly was that the Americans were likely to come into the war eventually, but not—he assumed—until 1942 at the earliest. Getting Russia out of the way quickly would limit the possibility of a grand coalition building up against him. In this Stalin helped. The Soviet leader refused to listen to all those who tried to warn him about Hitler’s plans. He assumed that the German leader would stick to the script that Stalin had worked out for him, providing clues of the imminence of attack. Churchill’s warnings were dismissed as self-serving propaganda, intended to provoke war between the two European giants to help relieve the pressure on Britain. Unlike Tsar Alexander in 1912, Stalin compounded the problem by having his armies deployed on the border, making it easier for the German army to plot a course that would cut them off before they could properly engage. The result was a military disaster from which the Soviet Union barely escaped. Yet a combination of the famous and fierce Russian winter and some critical German misjudgments about when and where to advance let Stalin recover from the blow. Once defeat was avoided, industrial strength slowly but surely revived, and the vast size of the Russian territory was too much for the invaders. The virtuoso performances of German commanders could put off defeat, but they could not overcome the formidable limits imposed by a flawed grand strategy.

Germany’s first blow against the Soviet Union depended on surprise (as did Japan’s against the United States), but it was not a knockout. The initial advantage did not guarantee a long-term victory. The stunning German victories of the spring 1940 and the bombing of British cities that began in the autumn approximated the possibilities imagined by Fuller, Liddell Hart, and the airpower theorists, but they were not decisive. They moved the war from one stage to another, and the next stage was more vicious and protracted. The tank battles became large scale and attritional, culminating in the 1943 Battle of Kursk. Populations did not crumble under air attacks but endured terrific devastation, culminating in the two atomic bombs dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—the war’s shocking finale. Our discussion of American military thought in the 1970s and 1980s will demonstrate the United States’ high regard for the German operational art and recall that this was not good enough to win the war.

Approaching Omaha Beach, Normandy Invasion. Photograph from the Army Signal Corps Collection, US National Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

When it came to victory, what mattered most was how coalitions were formed, came together, and were disrupted. This gave meaning to battles. The Axis was weak because Italy’s military performance was lackluster, Spain stayed neutral, and Japan fought is own war and tried to avoid conflict with the Soviet Union. Britain’s moment of greatest peril came when France was lost as an ally, but started to be eased when Germany attacked the Soviet Union. Churchill’s hopes rested on the United States, sympathetic to the British cause but not in a belligerent mood.

It was eighteen months before America was in the war. As soon as America entered the fray, Churchill rejoiced. “So we had won after all!…How long the war would last or in what fashion it would end, no man could tell, nor did I at this moment care … We should not be wiped out. Our history would not come to an end.”

Lawrence Freedman has been Professor of War Studies at King’s College London since 1982, and Vice-Principal since 2003. Elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1995 and awarded the CBE in 1996, he was appointed Official Historian of the Falklands Campaign in 1997. He was awarded the KCMG in 2003. In June 2009 he was appointed to serve as a member of the official inquiry into Britain and the 2003 Iraq War. Professor Freedman has written extensively on nuclear strategy and the cold war, as well as commentating regularly on contemporary security issues. He is the author of Strategy: A History. His book, A Choice of Enemies: America Confronts the Middle East, won the 2009 Lionel Gelber Prize and Duke of Westminster Medal for Military Literature. Follow Lawrence Freedman on Twitter @LawDavF.

Subscribe to OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Churchill, Hitler, and Stalin’s strategy in World War II appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDevelopment theories and economic miraclesReflections on World War IInternational Holocaust Remembrance Day reading list

Related StoriesDevelopment theories and economic miraclesReflections on World War IInternational Holocaust Remembrance Day reading list

May 16, 2014

Ros Bandt, Grove Music Online

We invite you to explore the biography of Australian composer Ros Bandt, as it is presented in Grove Music Online.

By Warren Burt

(b Geelong, Victoria, 18 Aug 1951). Australian composer, performer, installation and sound artist, instrument inventor, writer, educator, and researcher. Her early education consisted of high school in both Australia and Canada, followed by a BA (1971, Monash University), Dip Ed (1973, Monash), MA (1974, Monash), and PhD (1983, Monash). An interest in experimental music is apparent from her earliest compositions, many of which involve performance in specific places, improvisation, electronics, graphic notation, and the use of self-built and specially built instruments. These include Improvisations in Acoustic Chambers, 1981, and Soft and Fragile: Music in Glass and Clay, 1982. By 1977 an interest in sound installation and sound sculpture had become well established in her work (Winds and Circuits, Surfaces and Cavities), and is an area in which she has continued to the present day, having presented nearly 50 sound installations worldwide.

Johnson’s Map of Australia. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Bandt has also been involved in creating electro-acoustic works, often in collaboration with broadcasting organizations; work for or with radio forms a significant portion of her output. Many of these works, while using real-world elements, take a more narrative or illustrative approach to their material compared to the abstractionism of much electro-acoustic work. An electro-acoustic work such as Mungo (1992), made of sounds collected in the Lake Mungo region of New South Wales, presents soundscape as illustration; that is, the sounds are presented as important in themselves, rather than as material for formalistic musical development. In other electro-acoustic works, such as Thrausmata: Ancient Greek Fragments, 1997, the concern for narrative, and presenting endangered elements of the soundscape (in this case, disappearing languages) emerge as paramount. Other electro-acoustic works present sounds from specific environmental sites, such as Genesis (1983), for microtonally-tuned zither and pre-recorded speed-changed zither, both recorded in the same large resonant environment, and Stack (2000), made entirely from sounds collected from a large cylindrical tunnel exhaust stack in Melbourne. Of her compositions for instruments, Ocean Bells (1982) uses the Flagong, a glass instrument made by Bandt modelled on Harry Partch’s Cloud Chamber Bowls. The sculpture Aeolian Harps (1987) was a large wind powered string instrument, which was also recorded and those sounds used in a number of other works. Her recent Tragoudia II uses the tarhu, a 12-string spike fiddle (4 strings played, 8 sympathetic) invented by Australian luthier Peter Biffin, as well as pre-recorded sounds recorded in Crete. Tin Rabbit (2009–10) for wind-up rabbits, pre-recorded soundscape, music boxes, and tin suitcase shows a more whimsical side of her installation work. Free Diving (2008) for recorder orchestra and pre-recorded soundscape shows an integration of her interests in environmental sound with that of composing for traditional instruments.

Bandt has been equally active in collaborative work with musicians, dancers, and artists. She has been part of the groups La Romanesca (early music performance), LIME (improvisation), Back to Back Zithers (cross-cultural improvisation and composition), and Carte Blanche (a digital media duo with Brigid Burke), among others. She has also worked on many collaborative projects, such as Hear the Dance, See the Music (1989), a collaborative music-dance-technology performance; The White Room (1992), an installation for Warsaw Autumn, produced with Vineta Lagzdina, Warren Burt, Ernie Althoff, and Alan Lamb; and an ongoing series of collaborations with the German sound artist Johannes S. Sistermanns.

Bandt has written several books, including Sound Sculpture: Intersections in Sound and Sculpture in Australian Artworks (Sydney, 2001), the first comprehensive treatment of this kind of work in Australia. With Michelle Duffy and Dolly MacKinnon, she edited the anthology Hearing Places: Interdisciplinary Writings on Sound, Place, Time and Culture (Cambridge, 2007). She is also the director of the Australian Sound Design Project, the first comprehensive website and on-line resource, documenting over 130 Australian sound designers, composers, and sound sculptors. She has received grants from the Australian Research Council, The Australia Council, the Victorian Ministry for the Arts, the Australian Network for Art and Technology, and a number of other organizations. Her work has been broadcast on, and commissioned by ORF Austria, WDR Germany, ABC Australia, and Japanese Radio and TV, among others. Recordings of her work are available on the Move, New Albion, Ars Acustica, Sonic Art Gallery, and Au Courant labels, among others.

Writings

Sounds In Space: Windchimes and Sound Sculptures (Melbourne, 1985)

Creative Approaches to Interactive Technology in Sound Art (Geelong, 1990)

Sound Sculpture, Intersections in Sound and Sculpture in Australian Artworks (Sydney, 2001)

Edited with M. Duffy and D. MacKinnon: Hearing Places: Interdisciplinary Writings on Sound, Place, Time and Culture (Cambridge, 2007) [incl. CD]

The Australian Sound Design Project

Bibliography

M. Atherton: ‘Ros Bandt’, Australian Made Australian Played (Sydney, 1990), 90–92

B. Broadstock: ‘Ros Bandt’, Sound Ideas – Australian Composers born since 1950 (Sydney, 1995), 42–7

J. Jenkins: ‘Ros Bandt’, 22 Australian Composers (Melbourne, 1988), 9–21

A. McLennan: ‘A brief topography of Australian Sound Art and experimental broadcasting’, Continuum, viii (1994), 302–18 (electronic arts in Australia issue, ed. N. Zurbrugg)

R. Coyle: Sound In space (Sydney, 1995), 8–16

P. Read: ‘Silo Stories’, Haunted Earth (Sydney, 2003), 93–110

Ros Bandt website

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ros Bandt, Grove Music Online appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to EuropeAn intriguing, utterly incomplete history of Louis ArmstrongCreative ways to perform your music: tips for music students

Related Stories“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to EuropeAn intriguing, utterly incomplete history of Louis ArmstrongCreative ways to perform your music: tips for music students

Ricky Swallow, Grove Art Online

We invite you to explore the biography of Australian artist Ricky Swallow, as it is presented in Grove Art Online.

By Rex Butler

The Victorian College of The Arts. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

(b San Remo, Victoria, 1974). Australian conceptual artist, active also in the USA. Swallow came to prominence only a few years after completing his Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne, by winning the prestigious Contempora 5 art prize in 1999. Swallow could be said to have ushered in a wholly new style in Australian art after the appropriation art of the 1980s and 1990s. His first mature work was a hammerhead shark made out of plaid, later followed by such objects as bicycles and telescopes made out of plastic. These were not hyperreal simulacra in the manner of Pop artist George Segal or sculptor Ron Mueck. Rather, in remaking these objects in altered materials, Swallow wanted to open up a whole series of associations around memory and obsolescence. In one of the works for Contempora 5, Model for a Sunken Monument (1999), Swallow made a vastly scaled-up version of the mask Darth Vader wore in the Star Wars movies, fabricated out of sectioned pieces of fibreboard, which produced the effect of a melting or compression or indeed a diffraction, as though the piece were being looked at under water. Swallow also made a series of works that featured death as a subject, including iMan Prototypes (2001), which involved a number of skulls made of coloured plastic that looked like computer casings, and Everything is Nothing (2003), in which a carved wooden skull lies on its side inside an Adidas hood. In 2005, he was selected as Australia’s representative at the Venice Biennale, for which he produced Killing Time (2005). In this piece Swallow carved an extraordinary still-life of a table covered with a series of objects (fish, lobster, lemon), seemingly out of a single piece of Jelutong maple, in the manner of the Dutch vanitas painters of the 17th century. Swallow’s artistic lineage would undoubtedly include Jasper Johns, in particular his 1960 casting of two beer cans in bronze. His work could also be compared to contemporary Australian artist Patricia Piccinini and international artist Tom Friedman. Without a doubt, Swallow belongs to a generation of Australian artists who make work outside of any national tradition and without reference to the by-now exhausted critical questions associated with Post-modernism.Bibliography

E. Colless: ‘The World Ends When Its Parts Wear Out’, Memory Made Plastic (exh. cat., Sydney, Darren Knight Gallery, 2000)

J. Patton: Ricky Swallow: Field Recordings (Roseville, 2005)

A. Gardner: ‘Art in the Face of Fame: Ricky Swallow’s Refection of Reputation’, Reading Room: A Journal of Art and Culture, i (2007), pp. 60–79

A. Geczy: ‘Overdressed for the Prom’, Broadsheet, xxxvi/3 (2007), pp. 60–79

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ricky Swallow, Grove Art Online appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnnouncing the winners of the street photography competitionA conversation with Alodie Larson, Editor of Grove Art OnlineLudovico Sforza, Duke of Milan from Grove Art Online

Related StoriesAnnouncing the winners of the street photography competitionA conversation with Alodie Larson, Editor of Grove Art OnlineLudovico Sforza, Duke of Milan from Grove Art Online

Photography and social change in the Central American civil wars

Many hope, even count on, photography to function as an agent of social change. In his 1998 book, Photojournalism and Foreign Policy: Icons of Outrage in International Crises, communications scholar David Perlmutter argues, however, that while photographs “may stir controversy, accolades, and emotion,” they “achieve absolutely nothing.”

Camera Lens, by Jkimxpolygons. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

In my current research project, I examine the difficult question of what contribution photography has made to social change through an examination of images documenting events from the Central American civil wars — El Salvador and Nicaragua, more specifically — that circulated in the United States in the 1980s. Rather than measure the influence of these photographs in terms of narrowly conceived causal relationships concerning issues of policy, I argue that to understand what these images did and did not achieve, they need to be situated in terms of their broader social, political, and cultural effects — effects that varied according to the ever shifting relations of their ongoing reproduction and reception. Below are three platforms across which photographs from the wars in Central America circulated and recirculated in the United States in the 1980s.

(1) In the early 1980s, the US government adopted a dual policy of military support in Central America. In El Salvador, they provided aid against the guerilla forces or FMLN while in Nicaragua they backed the contra war against the Sandinistas. Many Americans learned and formulated opinions about these policies through photographs that circulated in the news media. The cover of the 22 March 1982 issue of Time, for instance, featured a photograph of a gunship flying over El Salvador. Taken by US photojournalist Harry Mattison, the editors at Time used the photograph as part of their cover story questioning the use by the US government of aerial reconnaissance photographs of military installations in Nicaragua to establish a causal link between the leftist insurgents in El Salvador and Communist governments worldwide.

(2) In addition to these reconnaissance photographs, the Reagan administration also turned to photography in an eight-page State Department white paper entitled Communist Interference in El Salvador, which was released to the American public on 23 February 1981. In this white paper, the US government included two sets of military intelligence photographs of captured weapons, which they believed would help them to further provide the American public with “irrefutable proof” of Communist involvement via Russia and Cuba in Central America, and thereby justify the escalation of US military and economic aid to the supposedly moderate Salvadoran government. The aforementioned article in Time also questioned the validity of the sources used in this document.

(3) While photography played a prominent role in debates over the existence of a communist threat in Central America, beginning in 1983, a number of artists and photographers — Harry Mattison, Susan Meiselas, Group Material, Marta Bautis, Mel Rosenthal, among others — put photographs from the Central American conflicts, some of which had circulated directly in the aforementioned contexts and others which had not, to a different use. Rather than employ photographs to perpetuate or even question the accuracy of communist aggression in the region, these artists and photographers instead used the medium to examine the imperialist underpinning of the Reagan administration’s foreign policy in Central America as well as the longstanding geopolitical and historical implications of US involvement there. To this end, they produced the following: the 1983 photography book and exhibition El Salvador: Work of Thirty Photographers, which was edited by Harry Mattison, Susan Meiselas, and Fae Rubenstein and toured various US cities in 1984 and 1985; Group Material’s 1984 multi-media installation Timeline: A Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America, on view at the P.S. Contemporary Art Center in Queens, New York, as part of the ad hoc protest organization Artists Call Against US Intervention in Central America; and the exhibition The Nicaragua Media Project that toured various US cities in 1984 and 1985. Together these three photography books and art exhibitions provided, what I call, a “living” history for photographs from the Central American civil wars.

In his 1978 essay “Uses of Photography” that was anthologized in his 1980 book About Looking, cultural critic John Berger argues that for photographs to “exist in time,” they need to be placed in the “context of experience, social experience, social memory.” Using Berger’s definition of a “living” history as a model, my research project offers a novel way to think about how, within the contexts of these exhibitions and books, photographs from the conflicts in El Salvador and Nicaragua functioned as dynamic, even affective objects, whose mobility and mutability could empower contemporary viewers to look beyond the so-called communist threat in the region that was perpetuated through the Reagan administration as well as the news media and begin to think more carefully about past histories of US imperialism and global human oppression in Central America.

Erina Duganne is Associate Professor of Art History at Texas State University where she teaches courses in American art, photography, and visual culture. She is the author of The Self in Black and White: Race and Subjectivity in Postwar American Photography (2010) as well as a co-editor and an essayist for Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain (2007). She has also written about her current research project for the blog In the Darkroom.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Photography and social change in the Central American civil wars appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnnouncing the winners of the street photography competitionUnknown facts about five great Hollywood directors“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to Europe

Related StoriesAnnouncing the winners of the street photography competitionUnknown facts about five great Hollywood directors“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to Europe

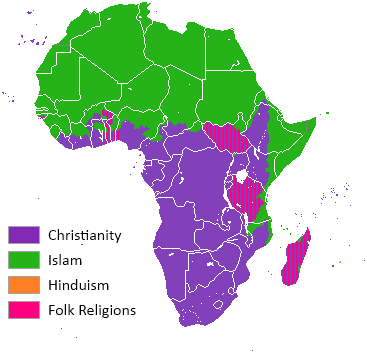

15 facts on African religions

African religions cover a diverse landscape of ethnic groups, languages, cultures, and worldviews. Here, Jacob K. Olupona, author of African Religions: A Very Short Introduction shares an interesting list of 15 facts on African religions.

By Jacob K. Olupona

African traditional religion refers to the indigenous or autochthonous religions of the African people. It deals with their cosmology, ritual practices, symbols, arts, society, and so on. Because religion is a way of life, it relates to culture and society as they affect the worldview of the African people.

Traditional African religions are not stagnant but highly dynamic and constantly reacting to various shifting influences such as old age, modernity, and technological advances.

Traditional African religions are less of faith traditions and more of lived traditions. They are less concerned with doctrines and much more so with rituals, ceremonies, and lived practices.

When addressing religion in Africa, scholars often speak of a “triple heritage,” that is the triple legacy of indigenous religion, Islam, and Christianity that are often found side by side in many African societies.

While those who identify as practitioners of traditional African religions are often in the minority, many who identify as Muslims or Christians are involved in traditional religions to one degree or another.

Though many Africans have converted to Islam and Christianity, these religions still inform the social, economic, and political life in African societies.

Traditional African religions have gone global! The Trans-Atlantic slave trade led to the growth of African-inspired traditions in the Americas such as Candomblé in Brazil, Santería in Cuba, or Vodun in Haïti. Furthermore, many in places like the US and the UK have converted to various traditional African religions, and the importance of the diaspora for these religions is growing rapidly. African religions have also become a major attraction for those in the diaspora who travel to Africa on pilgrimages because of the global reach of these traditions.

There are quite a number of revival groups and movements whose main aim is to ensure that the tenants and practice of African indigenous religion that are threatened survive. These can be found all over the Americas and Europe.

The concerns for health, wealth, and procreation are very central to the core of African religions. That is why they have developed institutions for healing, for commerce, and for the general well-being of their own practitioners and adherents of other religions as well.

Indigenous African religions are not based on conversion like Islam and Christianity. They tend to propagate peaceful coexistence, and they promote good relations with members of other religious traditions that surround them.

Today as a minority tradition, it has suffered immensely from human rights abuses. This is based on misconceptions that these religions are antithetical to modernity. Indeed indigenous African religions have provided the blueprint for robust conversations and thinking about community relations, interfaith dialogue, civil society, and civil religion.

Women play a key role in the practice of these traditions, and the internal gender relations and dynamics are very profound. There are many female goddesses along with their male counterparts. There are female priestesses, diviners, and other figures, and many feminist scholars have drawn from these traditions to advocate for women’s rights and the place of the feminine in African societies. The traditional approach of indigenous African religions to gender is one of complementarity in which a confluence of male and female forces must operate in harmony.

Indigenous African religions contain a great deal of wisdom and insight on how human beings can best live within and interact with the environment. Given our current impending ecological crisis, indigenous African religions have a great deal to offer both African countries and the world at large.

African indigenous religions provide strong linkages between the life of humans and the world of the ancestors. Humans are thus able to maintain constant and symbiotic relations with their ancestors who are understood to be intimately concerned and involved in their descendants’ everyday affairs.

Unlike other world religions that have written scriptures, oral sources form the core of indigenous African religions. These oral sources are intricately interwoven into arts, political and social structure, and material culture. The oral nature of these traditions allows for a great deal of adaptability and variation within and between indigenous African religions. At the same time, forms of orature – such as the Ifa tradition amongst the Yoruba can form important sources for understanding the tenants and worldview of these religions that can serve as analogs to scriptures such as the Bible or the Qur’an.

Jacob K. Olupona is Professor of African Religious Traditions at Harvard Divinity School, with a joint appointment as Professor of African and African American Studies in Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. A noted scholar of indigenous African religions, his books include African Religions: A Very Short Introduction, City of 201 Gods: Ilé-Ifè in Time, Space, and the Imagination, Òrìsà Devotion as World Religion: The Globalization of Yorùbá Religious Culture, co-edited with Terry Rey, and Kingship, Religion, and Rituals in a Nigerian Community: A Phenomenological Study of Ondo Yoruba Festivals. In 2007, he was awarded the Nigerian National Order of Merit, one of Nigeria’s most prestigious honors.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: A map of the Africa, showing the major religions distributed as of today. Map shows only the religion as a whole excluding denominations or sects of the religions, and is colored by how the religions are distributed not by main religion of country etc. By T.L. Miles via Wikimedia Commons via the Public Domain.

The post 15 facts on African religions appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy literary genres matterA religion reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsStatistics and big data

Related StoriesWhy literary genres matterA religion reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsStatistics and big data

May 15, 2014

A tale of two fables: Aesop vs. La Fontaine

Jean de La Fontaine’s verse fables turned traditional folktales into some of the greatest, and best-loved, poetic works in the French language. His versions of stories such as “The Shepherd and the Sea” and “The Hen that Laid the Eggs of Gold” are witty and sophisticated, satirizing human nature in miniature dramas in which the outcome is unpredictable. Here we compare La Fontaine’s versions to the enduring tradition of Aesop’s fables from the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Aesop’s Fables.

THE SHEPHERD AND THE SEA

Jean de La Fontaine

A neighbour of the goddess of the deep

lived free of care on earnings from his sheep,

content with what he had, which to be sure

was modest, though it was at least secure.

He liked to watch the ships return to land,

unloading treasures on the strand.

They tempted him; at last he sold his flock,

and traded all the money on the main;

he lost it when the vessel struck a rock.

The trader went to tend the flocks again,

not as the owner that he used to be,

when sheep of his had grazed beside the sea;

not Corydon or Tircis as before,

just Peterkin and nothing more.

In time he had enough, from what he gained,

to buy some of the creatures clad in fleece.

And then, when winds blew gentle and restrained,

to let the ships unload their goods in peace,

this shepherd could be heard to say:

“You want our money, Madam Sea;

apply to someone else, I pray,

for on my faith, you’re getting none from me.”

This is no idle tale that I invent;

it is the truth that I have told,

which through experience is meant

to show you that a coin you hold

is worth a dozen that you hope to see;

that with their place and rank men must agree;

that thousands would do better to ignore

the counsels of ambition and the sea,

or else they suffer; one perhaps may thrive.

The oceans promise miracles and more,

but if you trust them, storms and thieves arrive.

THE SHEPHERD AND THE SEA

Aesop

There was a shepherd tending his flocks in a place beside the sea. When he saw that the sea was calm and mild, he decided that he wanted to make a voyage. He sold his flocks and bought some dates which he loaded into a ship. He then set sail, but a fierce storm blew up and capsized the ship. The shepherd lost everything and barely managed to get to shore. Later on when the sea had grown calm once again, the shepherd saw a man on the beach praising the sea for her tranquility. The shepherd remarked, “That’s just because she’s after your dates!”

THE HEN THAT LAID THE EGGS OF GOLD

Jean de La Fontaine

Wanting it all will lose it all,

and avarice does that. So let me call,

to give some evidence for what I say,

on him who owned a chicken who would lay

(or so in fable we are told)

a golden egg each day.

Deciding that inside her she must hold

a treasure-house of gold,

he killed her, opened her, and found the same

as in the hens from which no riches came.

He had destroyed the jewel of his store.

Those people always seeking more

can learn a lesson from this dunce.

How many of them recently have passed

from wealthy man to pauper all at once

because they wanted wealth too fast!

THE MAN AND THE GOLDEN EGGS

Aesop

A man had a hen that laid a golden egg for him each and every day. The man was not satisfied with this daily profit, and instead he foolish;y grasped for more. Expecting to find a treasure inside, the man slaughtered the hen. When he found that the hen did not have a treasure inside her after all, he remarked to himself, “While chasing after hopes of a treasure, I lost the profit I held in my hands!”

Jean de La Fontaine (1621-95) followed a career as a poet after early training for the law and the Church. He came under the wing of Louis XIV’s Finance Minister, Nicolas Fouquet, and later enjoyed the patronage of the Duchess of Orléans and Mme de La Sablière. His Fables were widely admired, and he was already regarded in his lifetime as one of the greatest poets of his age. Christopher Betts was Senior Lecturer in the French Department at Warwick University. In 2009 he published an acclaimed translation of Perrault’s The Complete Fairy Tales.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Images from Selected Fables. Used with permission via the public domain.

The post A tale of two fables: Aesop vs. La Fontaine appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSelected fables about wolves and fishermenA Mother’s Day reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsHow to write a classic

Related StoriesSelected fables about wolves and fishermenA Mother’s Day reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsHow to write a classic

Brian Eno, the influential “non-musician” at 66

Brian Eno turns 66 today. It has become a cliché to start every profile of Eno by noting the eclecticism and longevity of his musical career. After all, here is a man who made his performance debut smashing a piece of wood against an open piano frame (La Monte Young, X (Any Integer) for Henry Flynt) and went on to produce award-winning albums for chart-topping bands. Nonetheless, it is still startling to realize that a quick game of One Degree of Brian Eno can bring together musicians as diverse as Cornelius Cardew, Luciano Pavarotti, Nico, Karl Hyde, and Coldplay. Eno’s credits include composer, singer, keyboardist, producer, clarinetist, video artist, and app designer; his music has been heard in concert halls, arenas, airports, movie theaters, and art galleries. Thanks to the start-up sounds he wrote for Windows 95, Eno might well have been the most-played composer of the 1990s. Not bad for someone who has embraced the label of “non-musician.”

It is impossible to give a brief yet coherent overview of a career that continues to be so rich and wide-ranging. Instead, and in honor of his 66th birthday, here are six of my favorite Eno contributions to our musical world.

(1) Richard Strauss, Also sprach Zarathustra from Portsmouth Sinfonia Plays the Popular Classics

Click here to view the embedded video.

Formed in 1970 by composer Gavin Bryars, the Portsmouth Sinfonia opened its membership to all–instrumental competence is not required. Its distinctive sounds come from the resulting mix of complete neophytes and trained musicians. Eno played the clarinet with them on and off for four years, and produced two of their three albums. The Sinfonia’s performance of Also sprach Zarathustra is typical in its chaotic, yet recognizable, attempt to play only the most famous part of Strauss’s half-hour tone poem.

(2) Eno, Discreet Music (1975)

Click here to view the embedded video.

Discreet Music is Eno’s first foray into what he would later call “ambient music.” In a now-famous anecdote, Eno claims its genesis in a failure of technology. While recovering at home after a serious accident, Eno was left with a recording that was playing too softly and only out of one channel. Unable to get up to fix the sound, he listened to barely audible output and discovered a new way of hearing. After Discreet, music no longer had to be the center of attention. It could be loops of deliberately simple music that become “part of the ambience of the environment just as the color of the light and the sound of the rain were parts of that ambience.”

(3) Penguin Café Orchestra, “Chartered Flight,” from Music from the Penguin Café (released in 1976 on Obscure; Eno, executive producer)

Click here to view the embedded video.

In 1975, following the success of Eno’s solo albums, Island Records created the Obscure label for him. Although short-lived (ten albums in three years), Obscure gave Eno the opportunity to introduce to a wider audience music they might not otherwise encounter. The quirky and charming Music from Penguin Café Orchestra was Obscure 7.

(4) U2, “The Unforgettable Fire” from The Unforgettable Fire, produced by Eno and Daniel Lanois (1984)

Click here to view the embedded video.

Given the critical and commercial enormous success Eno and U2 have enjoyed together, it is easy to forget that many–including Eno himself–found this an odd and risky collaboration when they first came together on The Unforgettable Fire. U2 famously brought Eno in so his “arty” and “weird” influence could change the band’s sound. (Bono: “We didn’t go to art school, we went to Brian.”) The album’s title track shows Eno’s introduction of a more atmospheric soundscape to U2’s previously straight-forward anthemic rock style.

(5) Eno, “This” from Another Day on Earth (2005)

Click here to view the embedded video.

Another Day on Earth was Eno’s first solo album of songs since the 1970s. Appropriately for Eno’s first album as a soloist for over a quarter of a century, the opening track “This” features not just his voice, but his voice multi-tracked as he intones the title over thirty times in this three-minute song. The result is an impossibly catchy tune that pairs Eno’s solemn, almost hypnotic singing with an infectiously catchy rhythmic accompaniment.

(6) Eno and Peter Chilvers, “Bloom” (2008)

“Bloom” brings Eno’s interests in ambient music and generative music to the iPhone. Billed as “an endless music machine” and a “music box for the 21st century,” this app allows you to create soundscapes reminiscent of Eno’s ambient experiments of the 1970s and 1980s by simply tapping on the screen. If you so choose, you can also experience your musical creation as a part of your ambience by allowing a generative player to take over. “Bloom” manages to be both addictive and soothing at the same time.

Happy birthday, Brian Eno. Our current musical landscape would be so much less interesting without you.

Cecilia Sun is an Assistant Professor of musicology in the Department of Music at the University of California, Irvine. She updated the Brian Eno entry for The Grove Dictionary of American Music, and she has an essay on Eno and the experimental tradition in the forthcoming collection Brian Eno: Oblique Strategies.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Brian Eno, the influential “non-musician” at 66 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to EuropeCreative ways to perform your music: tips for music studentsAn intriguing, utterly incomplete history of Louis Armstrong

Related Stories“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to EuropeCreative ways to perform your music: tips for music studentsAn intriguing, utterly incomplete history of Louis Armstrong

The financial consequences of terrorism

Within moments of the terrorist attacks in London on the morning of 7 July 2005, news of the unfolding crisis on public transport had reached traders in the City. The London Stock Exchange index, the FTSE 100, lost 3.5% of its total value within just 90 minutes of the trading session that day as a direct result of the bombings – equivalent to a total de-capitalisation of around £44,000,000,000. This immediate economic impact is staggering in and of itself, especially when you consider it only cost the British home-grown Al Qaeda terrorist cell £1,000 to finance their attack.

In the immediate aftermath of the 7/7 coordinated bombings, financial investors concentrated their sales orders on shares related to the tourist sector, fearful of travellers opting to cancel their stay in London. However, and even though the large airlines and tour operators, such as Lufthansa, gave their customers the option of cancelling or postponing their trips to London, there was no significant number of cancellations. The London Stock Exchange recovered its losses very quickly and by the close of trading on 7 July they had been restored. This was a remarkable achievement, serving to limit the potential impact of the home-made bombs that were detonated earlier that day.

Paternoster Square, home of the London Stock Exchange

The swift recovery from the potential economic losses during 7/7 had been pre-planned; the terrorist response in the City of London had not been left to chance. There were three important factors that were instrumental in restoring trading confidence in London so swiftly. The first was the British Government’s suggestion to the London Stock Exchange to suspend electronic trading in order to avoid a ‘deluge of orders’. This immediate counter-measure undoubtedly contributed to reducing losses, although the stock exchange operators had to face the almost impossible task of processing all orders by telephone.

The second factor which proved essential in restoring trading confidence in London was directly related to the impact of the attacks on the London’s infrastructure which was considered slight when compared to the catastrophic terrorist attacks in the United States of 9/11. In New York, many of the companies in the World Trade Center sustained huge losses, personal and financial. Canto Fitzgerald, whose footprint spanned the 101st to the 105th floor of the North Tower, lost 658 employees in the attack. The impact of losing such an influential trader and investor alongside others such as Morgan Stanley, the Atlantic Bank of New York, Bank of America, Fuji Bank, Lehman Brothers and Ashai Bank in New York itself, who represented just some of the financial institutions operating in the Twin Towers, served to exasperate the economic repercussions of Al Qaeda’s attack. The impact upon the New York Stock Market was devastating. Altogether, the United States Stock Market posted losses in terms of de-capitalisation of the Dow Jones Industrial and NASDAQ of $1.7 billion.

The third factor which proved instrumental in restoring trading confidence in London was that in the wake of 9/11, most financial institutions headquartered in London had developed ‘emergency evacuation plans’ which would enable them to transfer their business within a very short time-frame from central City of London locations to premises outside the urban area. These crisis contingencies provided confidence to investors and traders of business continuity; it appeared that the learning from 9/11 by government and financial security experts had served to minimise the economic impact of 7/7.

The economic repercussions of terrorist attacks reveals the short, medium, and long term consequences of terrorism. The sheer size, scale and scope of the economic impact of terrorism provides evidence to support the notion that terrorism in itself needs to be distinguished from other types of criminality, as it reaches far beyond the human, social and economic impact of other crimes. First and foremost terrorism is a crime, a crime which has serious consequences and one which requires to be distinguished from other types of crime, but a crime nonetheless. Terrorism seeks to undermine state legitimacy, freedom and democracy, the very fabric of our collective community values in Britain. These are a very different set of motivations and outcomes when compared against other types of crime. This is the reason why tackling terrorism is different to countering other types of criminality and why it requires a dedicated and determined approach to prevent it.

As the UK begins to observe the green shoots of economic recovery, we can be thankful to those in authority who quietly and patiently counter the threat to keep our communities and economic interests safe. A major terrorist event specifically targeted towards creating economic instability in the UK committed during the recent period of our financial vulnerability could have had a substantial impact – a catastrophic attack from which we may not have recovered so quickly with far-reaching economic repercussions. That being said, all in authority are required to note that the threat from terrorism remains substantial and complacency based upon the absence of a major terrorist attack remains misplaced and unwise.

Andrew Staniforth is Senior Research Fellow at the Centre of Excellence for Terrorism, Resilience, Intelligence and Organised Crime Research (CENTRIC). He is the author of Preventing Terrorism and Violent Extremism, part of the Blackstone’s Practical Policing series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Paternoster Square, London. By konstantin32, via iStockphoto.

The post The financial consequences of terrorism appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Oracle of Omaha warns about public pension underfundingIs the planet full?Tinderbox drenched in vodka: alcohol and revolution in Ukraine

Related StoriesThe Oracle of Omaha warns about public pension underfundingIs the planet full?Tinderbox drenched in vodka: alcohol and revolution in Ukraine

May 14, 2014

Little triumphs of etymology: “pedigree”

If I find enough material, I may tell several stories about how after multiple failures the ultimate origin of a common English word has been found to (almost) everybody’s satisfaction. The opening chapter in my prospective Decameron will deal with pedigree, which surfaced in English texts in the early fifteenth century. Many competing spellings have been recorded: pedigre, pedigrew, petigree, and their variants with -ee, -tt-, and -y- (the latter in place of -i-). Although no word resembles it, the French or Latin origin was proposed early on. The first students of English etymology realized that pedigree must be a compound and tried to recover the disguised elements. Strangely, unlike cap-a-pe(e), pedigree has never been spelled as a word group.

This is indeed a pedigree.

Perhaps those elements are par and degrés “by degrees,” with an allusion to descending from one generation to another? Not a fanciful guess, but what happened to r, the last sound of par or per? Or is the sought-for etymon degrés des pères “the rank or degree of forefathers”? But in pedigree the proposed elements appear in reverse order! Or Latin petendo gradum “deriving (seeking, pursuing) the descent”? Or a pede gradus, “like the Jesse window at Dorchester or others of that kind” (with reference to the Jesse tree showing the genealogy of Jesus)? In that etymology, pede, the dative of Latin pes “foot,” was taken to mean the stem of the tree; an analog would be German Stammbaum “genealogy, family tree, pedigree,” literally, “stem tree.” Or pied de greffe, that is, “the stem of the graft” = “the stem on which later branches were grafted”? Or “the table of degrees” (= of relationships)? Or pee de crue “the foot of the increase”? Or Greek país “child” and Latin gradus “degree”? C. A. F. Mahn, the reviser of the 1864 edition of Webster’s dictionary, who mentioned this etymology in a special publication (I have not seen it anywhere else), referred to A. Wagner. Such irritating references were all over the place in the past. I have no clue to the source and would be grateful to those of our readers who could tell me where A. Wagner (and which of the great multitude of A. Wagners) proposed that truly hopeless etymology.As early as 1769 pedigree was decomposed into pied de grue “the foot of the crane.” The reference would have been to the pedigrees drawn in the form resembling a crane standing on one leg, a position resembling the heraldic genealogical tree. Mahn knew this etymology, rejected it, and chose Stephen Skinner’s par degrés (Skinner’s dictionary appeared in 1671). Apparently, Augustin Thierry, the French historian, shared the crane’s foot idea, but I am not sure where he said so (allegedly, in his book on the Norman Conquest) and would again appreciate a tip.

Does the current etymology of pedigree have a leg to stand on?

Skeat, though at one time he was ready to accept Wedgwood’s “table of relationships” (Hensleigh Wedgwood occupied center stage in English etymological studies until Skeat displaced him). However, soon he felt convinced that the variants with -ew ~ -ewe were particularly revealing and tried to understand what the crane (French grue) had to do with genealogy or descent. He discovered the Old French proverb à pied de grue, glossed in a dictionary as “in suspence, on doubtful tearms” (I am retaining the contemporary orthography of the gloss). “Thus,” he said, “it is just conceivable that a pedigree was named from its doubtfulness, in derision.” In a survey of the conjectures on the pedigree of the word pedigree, J. Horace Round, a historian and genealogist of the medieval period, wrote (1887): “With reference to Professor Skeat’s suggestion, which is gravely advanced in his Dictionary, I cannot but wonder that so eminent an etymologist should have seriously put forward so far-fetched a derivation, and one so strangely out of the spirit of that age in which the word was formed.” The first edition of The Century Dictionary copied Skeat’s guess. However, Skeat soon gave it up and offered a convoluted but equally unconvincing new etymology, which Round again ridiculed. Unfortunately, Skeat expressed his strong confidence that a neater etymology than the one he proposed cannot be found. He who never thought twice before castigating his opponents preferred to be praised rather than taken to task (a pardonable attitude) and commented drily on a “not very courteous manner by Mr. Round.”In 1895 Charles Sweet, the brother of the famous Henry Sweet, and Round put forward the same explanation: according to them, the mark used in old pedigrees had the shape of a so-called broad arrow, that is, a vertical short line and two curved ones radiating from a common center, like three toes of a crane’s foot, with an allusion to the branching out of the descendants from the paternal stock. (In 1887 Round still believed in the source being a crane standing on one leg.) This explanation has become dogma. It can be found in all modern reference works, including the second edition of The Century Dictionary, the last edition of Skeat’s dictionary, and the OED. This situation justifies my title about small triumphs of etymology: after centuries of intelligent guessing, the right solution was found and satisfied nearly everybody.

As some contemporary critics pointed out, several flies stick in the otherwise admirable ointment. We have seen that the letter -g- in the middle of the word pedigree alternated with -c- (pronounced as k) and -d- alternated with -t-. The surnames Pettigrew and Pettygrew bear witness to the popularity of the -t- form. Those variants have never been explained. Also, the modern form is pedigree rather than pedigru(e). Obviously, people did not understand the derivation of that noun and changed -gru to something that looked like degree (as we have seen, many researchers also took -gre at face value). The alternation g ~ c is equally puzzling. At one time, Skeat traced the word to cru- “increase” and believed that the sound of k had acquired voice between two vowels. But the story appears to have begun with gru-, and there was no reason for -g- to turn into k! If the 1410 Latin example (the earliest one known) has value, the form Pedicru in it testifies to the antiquity of c (k) in pedigree.

I suspect that the original editors of the OED followed the Round-Sweet etymology without much enthusiasm, for they quoted Skeat (the latest version) and Sweet and seemed to have accepted their explanation for want of a better one. The OED online suggests that pedi- perhaps shows assimilation to petty or petit, but why should pedigree arouse associations with something small? (Are we ready to return to the idea of “small steps,” so that -gru- will emerge as an alteration of -gre-?) And if -gru- changed to -gre- and pedi- changed to peti- under the influence of degree and petty respectively, why did pedigree become so opaque so early? Speakers begin to indulge in folk etymological games when the word’s form becomes impenetrable through wear and tear. When was our word or the metaphorical phrase transparent and how long did it remain such? As far as we can judge, its provenance was Anglo-French, for on the continent its analogs did not exist (only much later did Engl. pedigree make its way into Modern French). It also remains unclear why the Anglo-Normans needed a neologism for a well-developed concept. Round suggested that pedigree began its life as slang. Perhaps it did. The upper classes do have their jargon. Is then the word centuries older than its first attestation (dignified compositions tend to avoid slang), so that by the fifteenth century no one could recognize the elements of the compound?

Such are etymological triumphs. In Rome, when a triumph was celebrated, a clown ran along the chariot and denigrated the conqueror. In the study of word origins our chariot is still rolling through the streets of Ancient Rome to the shrieks of a comedian.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Jesse window in Dorchester abbey. Photo by Bill Tyne. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Bill Tyne Flickr. (2) Zuiganji Sugito. Painting on sliding door (sugito) c. 1620. Hasegawa Toin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Little triumphs of etymology: “pedigree” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCasting a last spell: After Skeat and BradleyHenry Bradley on spelling reformUnsung heroes of English etymology: Henry Bradley (1845-1923)

Related StoriesCasting a last spell: After Skeat and BradleyHenry Bradley on spelling reformUnsung heroes of English etymology: Henry Bradley (1845-1923)

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers