Oxford University Press's Blog, page 808

May 28, 2014

Tourism and the 2010 World Cup

The World Cup, the Olympics and other mega sporting events give cities and countries the opportunity to be in the world’s spotlight for several weeks, and the competition among them to host these events can be as fierce as the competition among the athletes themselves. Bids that had traditionally gone to wealthier countries have recently become a prize to be won by prospective hosts in the developing world. South Africa became the first African host of the FIFA World Cup in 2010, and this summer, Brazil is hosting the first South American World Cup in 35 years. Russia recently completed its first Winter Olympics in Sochi and will return to the international stage in 2018 when the World Cup heads to Eastern Europe for the first time.

On the surface, this might appear to be a leveling of the playing field, allowing developing countries to finally share in the riches that these events bring to their hosts. A closer look, however, shows that hosting these events is an enormously expensive and risky undertaking that is unlikely to pay off from a purely economic standpoint.

Because of the extensive infrastructure required to host the World Cup or the Summer or Winter Olympics, the cost of hosting these events can run into the tens of billions of dollars, especially for developing countries with limited sports and tourism infrastructure already in place. Cost estimates are often unreliable, but it is said that Brazil is spending a combined $30 billion to host the Olympics and World Cup, Beijing spent $40 billion on the 2008 summer games, and Russia set an all-time record with a $51 billion price tag on the Sochi games. Russia’s record is not likely to stand for long, however, as Qatar looks poised to spend upwards of $200 billion bringing the World Cup to the Middle East in 2022.

South Africa fan in Johannesburg during World Cup 2010

Why do countries throw their hat into the rings to host these events? Politicians typically claim that hosting will generate a financial windfall For example, the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, the focus of our paper, cost the country $3.9 billion including at least $1.3 billion in stadium construction costs. The consulting firm Grant Thornton initially predicted 483,000 international visitors would come to the country for the event and that it would generate “a gross economic impact of $12 billion to the country’s economy”. The firm later revised its figures downward, to 373,000 international visitors and lowered the estimated economic impact to $7.5 billion. Following the event, a FIFA report stated that “309,554 foreign tourists arrived in South Africa for the primary purpose of attending the 2010 FIFA World Cup.”Our analysis of monthly tourist arrivals into South Africa during the months of the event, however, suggests that the tourist arrivals were even lower than this. The expected crowds and congestion associated with the tournament reduced the number of non-sports fans traveling to the country by over 100,000 leaving the net increase in tourists to the country during the World Cup at just 220,000 visitors. This figure is less than half that of Grant Thornton’s early projections and a full third below even the lowest visitor estimates provided after the tournament. We estimate that the cost to the nation per World Cup visitor lies in the range $4,700 to $13,000.

Our results provide a cautionary tale for cities and countries bidding for mega-events. The anticipated crowds may not materialize, and the economic gains from the sports fans who do come to watch the games need to be weighed against the economic losses associated from other potential travelers who avoid the region during the event.

Thomas Peeters is a PhD-fellow of the Flanders Research Foundation at the University of Antwerp. His main research interests are industrial organization and labor issues related to professional sports leagues. His work has been published in journals such as Economic Policy, the International Journal of Industrial Organization and the Journal of African Economies. Victor Matheson is a professor of economics at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, USA. He is the author of numerous studies concerning the economic impact of major sporting events on host countries and is a member of the executive board of the North American Association of Sports Economists. Stefan Szymanski is the Stephen J. Galetti Professor of Sport Management at the University of Michigan. His research in the economics of sports includes work on the relationship between performance and spending in professional football leagues, the theory of contests applied to sports, the application of sports law to sports organizations, financing of professional leagues and insolvency, the costs and benefits of hosting major sporting events. They are the authors of the paper ‘Tourism and the 2010 World Cup: Lessons for developing countries’, which is published in the Journal of African Economies.

The Journal of African Economies is a vehicle to carry rigorous economic analysis, focused entirely on Africa, for Africans and anyone interested in the continent – be they consultants, policymakers, academics, traders, financiers, development agents or aid workers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: South Africa fan in Johannesburg during World Cup 2010. By Iscar Blanco [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Tourism and the 2010 World Cup appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesVirgil in RussiaSam sellsWhat is English?

Related StoriesVirgil in RussiaSam sellsWhat is English?

May 27, 2014

Five reasons why Spain has a stubbornly high unemployment rate of 26%

The Spanish economy roared along like a high-speed train for a decade until it slowed down dramatically in 2008. Only recently has it emerged from a five-year recession. But the jobless rate has tripled to 26% (four times the US level) and will not return to its pre-crisis level for up to a decade. Why is this?

(1) The economic model was excessively based on the shaky foundations of bricks and mortar.

Between 2000 and 2009, Spain accounted for around 30% of all new homes built in the European Union (EU), although its economy only generated around 10% of the EU’s total GDP. In one year alone (2006), the number of housing starts (762,214) was more than Germany, France, and Italy combined. After Spain joined the euro in 1999, interest rates were low, property was seen as a good investment in a country with very high home ownership (85%), and there was a high foreign demand for holiday and retirement homes due to the 60 million tourists who visited Spain annually.

When the property bubble burst, jobs were destroyed as quickly as they had been created. As construction is a labor intensive sector, its collapse reverberated through other areas of the economy. Between 2002 and 2007, the total number of jobholders, many of them on temporary contracts, rose by a massive 4.1 million, a much steeper rise than in any other EU country and more than three times higher than the number created in the preceding 16 years. Since 2008, more than 3 million jobs have been lost, around half of them in the construction and related sectors.

(2) Labor market laws were too rigid.

Spain has a dysfunctional labor market: even at the peak of the economic boom in 2007, the unemployment rate was 8%, a high rate by US standards. At the hiring end, Spain’s labor market laws were very flexible, largely as a result of widespread use and abuse of temporary contracts, but at the firing end, severance payments were higher than in comparable countries. This made employers reluctant to put workers on permanent contracts. The reforms approved in 2012 by the conservative government of the Popular Party, which returned to power at the end of 2011, lowered dismissal costs and gave companies the upper hand, depending on their financial health, in collective wage bargaining agreements between management and unions. The reforms have yet to have a discernible impact on job creation. They have, however, lowered the GDP growth threshold for net job creation from around 2% to 1.3%. The Spanish economy is expected to grow by more than 1% this year.

(3) The property sector caused a banking crisis and corruption to flourish.

The 45 regionally-based and unlisted savings banks, which accounted for around half Spain’s financial system, were closely connected to politicians and businessmen. Many of them made reckless loans to developers and were massively exposed to the property sector when it crashed. The reclassification of land for building purposes and the granting of building permits, in the hands of local authorities, created a breeding ground for corruption. Bad loans soared from 0.7% of total credit in 2007 to more than 13%. The European Stability Mechanism came to the rescue of some banks in 2012 with a €41 billion bail-out package in return for sweeping reforms. The number of savings banks has been reduced to seven, with high job losses. Spain exited the bail out in January.

Spain was ranked 40th out of 177 countries in the latest corruption perceptions ranking by the Berlin-based Transparency International, down seven places from the year before. Its score of 59 was six points lower than its previous score in 2012, in a numerical index where the cleanest countries are those closest to a score of 100. Spain lost more points than almost every other country, topped only by war-torn Syria.

(4) The education system is in crisis.

The education system is holding back the need to create a more sustainable economic model. One in every four people in Spain between the ages of 18 and 24 are early school leavers, double the EU average but down from a peak of one-third during the economic boom, when students dropped out of school at 16 and flocked in droves to work in the construction and related sectors. Almost one-quarter of 15-29 year-olds are not in education, training, or employment. Results in the OECD’s Pisa international tests in reading, mathematics, and scientific knowledge for 15-year-old students and for fourth-grade children in the TIMS and PIRLS tests are also poor. No Spanish university is among the world’s top 200 in the main academic rankings. Research, development and innovation spending, at 1.3% of GDP, is way below that of other developed economies. In these conditions, the creation of a more knowledge-based economy is something of a pipe dream, and the brightest young scientists and engineers are emigrating.

(5) Spain received more immigrants in a decade than any other European country.

Immigrants were lured to Spain when the economy began to expand rapidly. Their number soared from more than 900,000 in 1995 to 5.7 million in 2012, the largest increase in a European country in the shortest time. They were particularly needed in the construction and agricultural sectors, as there were not enough Spaniards prepared to work in them. At the peak of the boom in 2007, more than half of the 3.3 million non-EU immigrants in Spain worked in the construction sector. When the economy went into recession, immigrants bore a large part of the surge in the unemployment, as many of them were on temporary contracts and were the first to lose their jobs. The jobless rate among immigrants (37%) is much higher than that for Spaniards (24%). Immigrants only began to return to their countries in significant numbers in 2012 and Spain’s population declined by 500,000 in 2013, an unprecedented fall in the country’s modern history.

William Chislett is the author of Spain: What Everyone Needs to Know. He is a journalist who has lived in Madrid since 1986. He covered Spain’s transition to democracy (1975-78) for The Times of London and was later the Mexico correspondent for the Financial Times (1978-84). He writes about Spain for the Elcano Royal Institute, which has published three books of his on the country, and he has a weekly column in the online newspaper, El Imparcial.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: “Palacio Real” by Bepo2. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Five reasons why Spain has a stubbornly high unemployment rate of 26% appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAll (European) politics is nationalRestoring our innovation “vision”The politics of political science

Related StoriesAll (European) politics is nationalRestoring our innovation “vision”The politics of political science

The rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire in pictures

Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE), King of Macedonia, ruled an empire that stretched from Greece in the west to India in the east and as far south as Egypt. The Macedonian Empire he forged was the largest in antiquity until the Roman, but unlike the Romans, Alexander established his vast empire in a mere decade. As well as fighting epic battles against enemies that far outnumbered him in Persia and India, and unrelenting guerrilla warfare in Afghanistan, this charismatic king, who was worshiped as a god by some subjects and only 32 when he died, brought Greek civilization to the East, opening up East to West as never before and making the Greeks realize they belonged to a far larger world than just the Mediterranean.

Yet Alexander could not have succeeded if it hadn’t been for his often overlooked father, Philip II (r. 359-336), who transformed Macedonia from a disunited and backward kingdom on the periphery of the Greek world into a stable military and economic powerhouse and conquered Greece. Alexander was the master builder of the Macedonian empire, but Philip was certainly its architect. The reigns of these charismatic kings were remarkable ones, not only for their time but also for what — two millennia later — they can tell us today. For example, Alexander had to deal with a large, multi-cultural subject population, which sheds light on contemporary events in culturally similar regions of the world and can inform makers of modern strategy.

Battle of Granicus, 334 BCE

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

West met East violently when Alexander crossed from Europe to Asia in 334 BCE. In bitter fighting with massive casualties Alexander overcame enemy armies to establish the largest ancient empire before the Roman.

Alexander the Great

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Alexander III ('the Great') was born in 356, the son of Philip II and his 4th wife Olympias, and died in Babylon in June 323.

Map of Macedonia and Greece

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In far northern Greece, Macedonia was a political, military and economic backwater before the reign of Philip II (359-336); when he was assassinated in 336 he had conquered Thrace and Greece and doubled Macedonia's population.

Phalanx formation with sarissas

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Philip's military reforms created the formidable professional Macedonian army with new shock and awe tactics, training, and weaponry, including the deadly sarissa, a 14-16' spear with a sharp pointed iron head that impaled enemy infantrymen.

Bust of Aristotle

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

When his son Alexander was 14, Philip hired Aristotle, foremost intellectual of the day, as his tutor. Aristotle taught Alexander for 3 years, turning him into an intellectual who spread Greek culture in the East.

Mosaic of Alexander the Great, Pompeii

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Alexander the intellectual was nowhere near Alexander the warrior. In 333 BCE he battled Darius III, Great King of Persia, at Issus, forcing him to flee the battlefield. This was the beginning of the end for the ruling Achaemenid dynasty. This famous mosaic was discovered buried under Vesuvius' ash at Pompeii and is modelled on a contemporary painting showing Alexander bearing down on Darius, who is surrounded by the Macedonians' sarissas.

Death of Alexander the Great

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Alexander died in Babylon in June 323 BCE. he had not left an undisputed heir, so his generals carved up his empire among themselves, bringing to an end what Philip and Alexander had fought so hard to achieve. Alexander's legacy and his failing as a king and a man question whether he deserves to be called great.

Ian Worthington is Curators’ Professor of History and Adjunct Professor of Classical Studies at the University of Missouri. He is the author of numerous books about ancient Greece, including Demosthenes of Athens and the Fall of Classical Greece and By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images: 1. From By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire. Used with permission. 2. Bust of Alexander the Great at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek by Yair Haklai. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. 3. Map of Greece from By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire. Used with permission. 4. Macedonian phalanx by F. Mitchell, Department of History, United States Military Academy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 5. Aristotle Altemps Inv8575 by Jastrow. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. 6. Alexander Mosaic by Magrippa. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. 7. The Death of Alexander the Great after the painting by Karl von Piloty (1886). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire in pictures appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWas Alexander the Great poisoned?Kotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of languageVerdun: the longest battle of the Great War

Related StoriesWas Alexander the Great poisoned?Kotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of languageVerdun: the longest battle of the Great War

John Calvin’s authority as a prophecy

For some, it was no surprise to see a book claiming that John Calvin believed he was a prophet. This reaction arose from the fact that they had already thought he was crazy and this just served to further prove the point. One thing to say in favor of their reaction is that at least they are taking the claim seriously; they perceive correctly its gravity: Calvin believed that he spoke for God; that to disagree with him was to disagree with the Almighty ipso facto.

The belief may, of course, appear utterly astonishing and bizarre to us today. While I’m sympathetic with such astonishment, I don’t share it. This is not necessarily because I believe Calvin was a prophet. It’s rather because I know him well enough to know that such a belief is entirely in keeping with his character and I suppose I’ve grown accustomed to it. Most of what comes out of his mouth or flows from his pen carries with it, it seems patently clear to me, a prophetic tone and energy. There’s no question in my mind that he held that the heavens themselves opened when he opened his mouth.

I have friends who ask with some chagrin: “didn’t Calvin feel the same sense of utter uncertainty, confusion, and awkwardness with respect to his own place in the universe that people in the twenty-first century do? Wasn’t he aware of his own weaknesses?” If so, the logic follows, how could he have become convinced that he was a divine messenger since this assumes a certain sense of faultlessness? For one of us to believe ourselves a prophet seems impossible, so, what of Calvin? Didn’t his inner reservations and neuroses weigh on his self-conception and convince him that he couldn’t possibly be the mouthpiece of the Divine? My answer is a simple “no.” I don’t think he believed that he erred in his service of God. Ever.

John Calvin by Hans Holbein the Younger. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Let us recall that it’s Calvin who indicted the greatest theologians with the charge that they had mixed hay with gold, stubble with silver, and wood with precious stones (a reference to the Apostle Paul’s warning to those who had corrupted their labors in God’s service in 1 Corinthians 3: 15). He indicted Cyprian, Ambrose, Augustine, and some from what he referred to as more recent times, such as Gregory and Bernard. He said of these individuals that they could only be saved on the condition that God wipe away their ignorance and the stain which corrupted their work. They could only be saved as through fire. He even said this of Augustine, the Theologian par excellence for everyone in Early Modern Europe. Let us recall as well that Calvin could write in 1562, just two years before he died, that if anyone were his enemy, then they were the enemies of Christ. He goes on in this writing, entitled Responsio ad Balduini Convicia, to say that he had never taken up a position out of a hostile personal motive or being prompted by spite. He insists, in fact, in language that is astounding to read that anyone who is his enemy feels this way about him because they oppose the good of the church and they hate godly teaching. This is Calvin. This is the prophet; the one to whom the mantle of Elijah had been passed.

The natural question to ask at this point is whether Calvin believed that his writings should be added to the canon of Scripture? It might seem only logical, according to what I’m arguing, that he did. However it would, of course, be extremely difficult to justify such a claim. But I don’t think that’s all that can be said on the question. For there is a logic to the idea that not only Calvin but also Zwingli, Luther, Knox, and others who believed themselves raised up as prophets might have thought this. There are, moreover, numerous vocational, temperamental, theological, strategic, psychological, doctrinal, and relational reasons that would need to be taken into account before drawing a conclusion one way or the other on the question. I don’t put it out of the realm of possibility that Calvin could have believed this, at least at some level. He did, after all, tell his fellow ministers on his death bed that they were to “change nothing,” suggesting that the foundation he had laid was perfect and, thus, that the repository representing that foundation—namely, his biblical commentaries, lectures, theological treatises, and magnum opus, The Institutes of the Christian Religion—should serve as the origin from which the Christian church was to be rebuilt. So I would not be utterly shocked if he did, in fact, believe that his oeuvre should be made part of the canon of Scripture. Unfortunately, we will never know.

Jon Balserak is currently Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Bristol. He is an historian of Renaissance and Early Modern Europe, particularly France and the Swiss Confederation. He also works on textual scholarship, electronic editing and digital editions. His latest book is John Calvin as Sixteenth Century Prophet (OUP, 2014).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post John Calvin’s authority as a prophecy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesVerdun: the longest battle of the Great WarKotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of language‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchange, part 2

Related StoriesVerdun: the longest battle of the Great WarKotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of language‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchange, part 2

May 26, 2014

What is English?

What is English? Ask any speaker of English, and the answer you get may be “it’s what the dictionary says it is.” Or, “it’s what I speak.” Answers like these work well enough up to a point, but the words that make it in the dictionary are not always the words we hear being used around us. And the language of any one English speaker can differ significantly in pronunciation and word order from the English of another, particularly today, when two out of three English speakers have learned English as a second or third language. In What Is English? And Why Should We Care?, Tim Machan addresses these deceptively complex questions in order to suggest the ways in which definitions of English always depend on speakers’ definitions of themselves.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Tim Machan is Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame. His books include What Is English? And Why Should We Care?, English in the Middle Ages, Language Anxiety, and Vafþrúðnismál.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What is English? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesVerdun: the longest battle of the Great WarKotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of languageSmall triumphs of etymology: “oof”

Related StoriesVerdun: the longest battle of the Great WarKotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of languageSmall triumphs of etymology: “oof”

Does the mafia ever die?

The mafia never dies; the state can destroy mafiosi but not the mafia – such proclamations are common, especially among mafiosi, who believe the Thing, the Organization, is always out there ready to sanction them. Few law enforcement officials or criminologists are prepared to declare any mafia dead either. For the former, the mafia makes for a colourful enemy, while the latter would have a hard time knowing whether a mafia, as a secretive organization that attempts to sell protection and regulate illegal and legal markets, truly has died. Police departments can get extra funding and government support by playing up to the threat of a conspiratorial, hydra-headed mafia monster. Governments can blame shadowy mafia figures or immigrant alien conspiracies for problems of crime and violence and other failings, while ‘transnational organized crime’ can be invoked to demonize and justify meddling in other countries, particularly in the age of the ‘war on terror’.

Nevertheless, states do occasionally attack mafia-like organizations. There are numerous examples of anti-mafia policies from different countries all with varying levels of success. One such case is the post-Soviet republic of Georgia. An anti-mafia campaign launched there in 2005 has been heralded an overall success. This is curious given how weak the Georgian state is and the supposed embeddedness of organized crime in the post-Soviet part of the world. This leads to a puzzle then: what factors might weaken the strength of mafias and cause their decline, if not their death?

Many studies focus on state-centric factors to explain decline. Governments must make strategic decisions about when to attack the mafia as it may prove to be an expensive activity which reaps few gains in crime control or at the ballot box. In some countries, governments face violent backlashes if the mafia is challenged. In Brazil for example, the First Command of the Capital (the PCC, a prison gang that controls illegal markets on the streets) is able to virtually shut down the city of Sao Paolo if it chooses to oppose the state. Thus, mafias and states often simply exist in wary equilibrium of each other, often maintaining a negotiated connection through corrupt links on local levels. Still, at certain moments states can launch full out attacks on mafias, though success is rarely a given.

In Italy and the United States, anti-mafia legislation has enabled greater punitive measures against those who order the commission of crime and engage in patterned acts of racketeering. In Italy, law enforcement reform as well as civil society mobilization, emerging after the mob killings of the judges Falcone and Borsellino in 1992, has been relatively effective, at least in Sicily. These measures include new law enforcement techniques and heightened police coordination, including longer investigation times, the greater use of wire-tapping, entrapment, state’s witnesses, and confiscation of mafia assets and the criminalization of activities that aid the mafia. Such state policies have been recreated elsewhere, for example and most recently, in post-Soviet Georgia.

However, a simple emphasis on the policies of the state and the changes in the socio-economic environment does not account for the vulnerabilities or resilient qualities that decide whether a mafia survives or succumbs to state attack. In Georgia, I argue that, regardless of the state’s anti-mafia policy, internal contradictions within a group called the ‘thieves-in-law,’ a particularly fearsome mafia, was the real reason for the decline of this network of mafiosi there.

Strength in recruitment, for example, is a key variable in survival. Just like any organization mafias require a flow of high quality individuals to reproduce themselves. The thieves-in-law failed to do this. This failure was due to maladaptive institutional change in difficult conditions: wider criminal conflict in conditions of state-collapse led to quicker recruitment and lower quality human capital. The video embedded below discusses this in more detail.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Similarly, internal and external structuring of relations is vital for robust organization, effective adaptation, flows of information, and efficient monitoring and sanctioning. Yet the organization of criminal activities is often risky, and constantly changing in conditions of permanent insecurity and uncertainty. The thieves-in-law in Georgia did not negotiate the violent, difficult conditions of state collapse that occurred in Georgia in the 1990s at all well. It affected their ability to coordinate and regulate their network. All that was then required was the political will to go on the offensive against what was in fact disorganized crime.

The general conclusions from the Georgian case then are: rather than enjoying a vacuum of state power as we might expect, the mafia actually abhors one. Moreover, focusing on organizational vulnerabilities of organized criminals might aid our understanding of how best to tackle established and seemingly indestructible mafia groups, helping to explode the myth that the mafia is forever.

Dr Gavin Slade is an Assistant Professor in Criminology at the University of Toronto, Canada, having gained his PhD in Law from the University of Oxford in 2011. He is primarily interested in organized crime and prison sociology; in particular, criminological questions arising from post-Soviet societies, having lived and worked in Russia and Georgia for almost seven years. He maintains a broad interest in criminal justice reform in transitional contexts and has also worked on such issues in the non-governmental sector in Georgia. He is the author of Reorganizing Crime: Mafia and Anti-Mafia in Post-Soviet Georgia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Historical building in the center of Batumi, Georgia. © Kenan Olgun via iStockphoto.

The post Does the mafia ever die? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTracking the evidence for a ‘mythical number’10 things you may not know about the Police FederationRestoring our innovation “vision”

Related StoriesTracking the evidence for a ‘mythical number’10 things you may not know about the Police FederationRestoring our innovation “vision”

Psychology, veterans, war, and remembrance

My daily walk to work takes me through West Point’s cemetery. Founded in 1817, the cemetery includes the graves of soldiers who fought in the American Revolution, and in all of the wars our country has fought since. I often stop and reflect on the lives of these men and women who are interred here. Many headstones are of West Point graduates who were killed in World War II, including several on D-Day. Others fell in the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, and Korea and Vietnam. One section holds special significance for me, since it contains the graves of former cadets and colleagues I have known in the past 14 years who died in Iraq or Afghanistan. No matter how preoccupied I may be with the vagaries of day to day life, a sense of peace and calm envelopes me as I stroll among the headstones. I feel I am among friends and comrades and there is a sense of connectedness with the past.

One of the soldiers interred at West Point is Lieutenant Christopher Kurkowsi. Chris graduated from West Point in 1986 with a degree in Engineering Psychology. He became an artillery officer and was killed on 26 February 1988 when the helicopter he was in crashed while on a routine training mission. At the time of the accident, Chris’s academic mentor at West Point, Lieutenant Colonel Timothy O’Neil, had initiated paperwork to send Chris to graduate school in psychology with a follow-on assignment to his old department at West Point. According to Lieutenant Colonel O’Neil, Chris would have made a tremendous psychologist and professor. Chris’s death exemplifies the loss of talent and potential of all of the soldiers buried at West Point.

Earlier this month, West Point held its annual “Inspiration to Serve” cemetery tour. All members of the West Point Class of 2016, who are finishing their second of four years of academic study and military training at West Point, participated. On this day, classmates, family, or friends of the fallen stand by a gravesite, and tell the story of the deceased to the cadet attendees. Of special interest this year, MaryEllen Picciuto, one of Chris Kurkowski’s classmates, told his story of service and sacrifice. The cadets stood respectfully and listened intently, as Ms. Picciuto brought Chris back to life through her remembrances. As she did this, other cadets stood by other graves, hearing the life story of other West Point graduates who gave their lives in the service of our country.

As a Nation, our move to an all volunteer force has distanced most Americans from direct experience and knowledge of the military and the men and women who serve. Cognitive psychologists make a distinction between semantic and episodic memory. The former is memory of generalized facts that are not part of our own personal experience. The latter, in contrast, are of events personally experienced. Think about your own memories. Those that are episodic are likely more vivid and tangible, and perhaps have more meaning in your own life story. You “know” from semantic memories, but you can “feel” in episodic memories.

Perhaps this Memorial Day, in between picnics and family activities, you can visit a veterans cemetery. Walk among the headstones, read the inscriptions, and reflect on what these men and women sacrificed for our Nation. Like Lieutenant Kurkowski, they had dreams, ambitions, life goals, and family and friends who loved them. Through such a visit, perhaps you can form an episodic memory by honoring the fallen for their service, and in doing so forge a more personal connection with these American heroes.

Note: The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect the position of the United States Military Academy, the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense.

Michael D. Matthews is Professor of Engineering Psychology at the United States Military Academy. Collectively, his research interests center on soldier performance in combat and other dangerous contexts. He has authored over 200 scientific papers and is the co-editor of the Oxford Handbook of Military Psychology (Oxford University Press, 2012). Dr. Matthews’ most recent book is Head Strong: How Psychology is Revolutionizing War (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Photos courtesy of Michael D. Matthews. Used with permission.

The post Psychology, veterans, war, and remembrance appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat role does symmetry play in the perception of 3D objects?Helping yourself to emotional healthSome highlights of the BPS conference 2014 Birmingham

Related StoriesWhat role does symmetry play in the perception of 3D objects?Helping yourself to emotional healthSome highlights of the BPS conference 2014 Birmingham

Virgil in Russia

In 1979 one of the most prominent Russian classical scholars of the later part of the twentienth century, Mikhail Gasparov stated: “Virgil did not have much luck in Russia: they neither knew nor loved him . . .”. This lack of interest in Virgil on Russian soil Gasparov mostly blamed on the absence of canonical Russian translations of Virgil, especially the Aeneid. There have been several attempts at translating the Roman epic into Russian, four of them most notable and significant. In the 18th century Vasilii Petrov (1730-1778), the court poet of Catherine the Great was the first poet to undertake this monumental task. His translation, however, although highly praised by Catherine and the newly established Russian Academy, was ridiculed by the educated elite as a feeble shadow of the great Roman poem. Another attempt at translating the whole epic did not happen until late nineteenth century and was undertaken by a prominent Russian poet Afanasii Fet (1820-1892) who together with a Russian philosopher Vladimir Solov’ev (1853-1900) attempted to finally bring the Aeneid to the Russian reading public. While this translation was received much more favorably, it still did not acquire the desired canonical status. Valerii Briusov (1873-1924), one of the founders of Russian Symbolism and an accomplished translator, devoted most of his life to yet another translation of the Aeneid, but also fell short of the mark because the final version of his translation exhibited many ‘foreignizing’ tendencies replete with incomprehensible Latinisms, which rendered the text almost unreadable. Sergei Osherov (1931-1983), a Russian classical scholar, who undertook another translation during the era of ‘socialist realism’ took a more liberal approach to the Virgilian text, one that rendered it significanltly more readable by a wider audience but steered away from the poetic intricacies and complexity of the Latin text.

This is the situation Gasparov was referrring to when alluding the failure of Virgil to provoke interest in Russian reading public. And yet the importance of Virgil for the formation of Russian literary identity remained consistent as Russian writers partcipated in building their national literary canon.

Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Russian consciousness formed its connection to Rome and thus to Virgil through two venues: one was through the great but pagan Roman empire – that was the political claim that entailed imperial power and expansion. Another was via Byzantine Rome and the piety associated with its Orthodoxy. Even Catherine the Great who prided herself on her secularism and association with Voltaire and Montesquieu, had in mind the leadership of Russia as the religious and political ideal of a unified ecumenical Orthodoxy under which all the Orthodox East would be politically united.

Virgil came to be seen as the answer to both discourses and to encompass both the imperial rhetoric and the spiritual quest for a Russian Christian soul.

The eighteenth century Virgilian reception was mainly concerned with the imperial aspirations as the initial reaction to the text of the Aeneid in Russian literature. Antiokh Kantemir’s (1708-1744), Mikhailo Lomonosov’s (1711-1765), and Nikolai Kheraskov’s (1733-1807) failed attempts at a national heroic epic were encouraged by the Russian ruling family but failed to elicit any interest in the reading public. In the same way Vasilii Petrov’s first unfortunate translation of the Aeneid reflected the tendency to glorify and idealize the ruling monarch as a way to promote national pride but was found lacking in adequately reflecting the poetic genius of Virgil in Russian.

As Russian literary figures of the eighteenth century were experimenting with different approaches to a national epic, there emerged a quite influential and popular genre of travesitied epics. In opposition to the courtly attempts to glorify the house of the Romanovs through Virgilian reception, Nikolai Osipov wrote his burlesque Aeneid Turned Upside Down (1791-6) where following the European examples of French Paul Scarron and German Aloys Blumauer he made Aeneas speak the base language of the Russian everyday man and cast his adventures in a less than heroic light.

Epic, however, was not the only genre through which Russian literati tried to bringVirgil to Russia. As with the most European receptions of the Aeneid, the tragic pathos of Dido’s love and suicide attracted attention already in the eighteenth century at the same time with the epics. Iakov Kniazhnin’s ((1758-1815) play Dido (1769), which stands at the very beginnings of Russian mythological tragedy, offered his readers an unusual and politicized interpretation of Book 4 of the Aeneid combined with French and Italian influences on his Virgilian reception.

With Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837) Russian literature entered yet another stage of Virgilian reception. The courtly literature was long forgotten and so were the monumental attempts at epic grandeur. Pushkin refrained from any open allusion to or evocation of Virgil limiting them usually to a few passing jokes. Instead he penned his own diminutive epic of national pride, the Bronze Horseman in which he conteplated the same issues pondered by Virgil two thousand years earlier. At the center of his poem is the confrontation between the man and a state, individual happiness and civic duty, which Pushkin approaches in ways familiar to the readers of Virgil.

While the connection of Virgilian reception with Russia’s ‘messianic’ Orthodox mission manifested itself intermittently in secular court literature and even in Petrov’s translation, the specific and pointedly deliberate articulation of that mission occured in the literature at the beginning of the twentieth century and is represented by such formative thinkers as Vladimir Solov’ev (1853-1900), Viacheslav Ivanov (1866-1949), and Georgii Fedotov (1886-1951), who saw Virgil in messianic and prophetic light and as the source of answers for Russian spiritual quest both at home and abroad.

With Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996) the Russian Virgil entered the stage of post-modernism. Brodsky’s Virgilian allusions are numerous and persist in Brodsky’s poetics through its entire evolution. However, the monumental themes of either imperial pride or messianic mission become replaced in Brodsky by simpler, mundane, and even base themes. Brodsky reshaped Virgil’s Arcadia into a snow covered terrain and his Aeneas is a man tormented by the brutalizing price of his heroic destiny. As Brodsky reconfigured different episodes from the Virgilian texts through the lyric prism of human emotion, Virgil remained a constant presence both in his poetry and his essays as the poet moved with ease between ancient and modern, between emotion and detachment, between Russian and English, providing a remarkable closure to the Russian Virgil in the twentieth century.

Zara Martirosova Torlone is an Associate Professor of Classics and on the Core Faculty at the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies at Miami University (Ohio, USA). She received her B.A. from Moscow State University, Russia and her Ph.D. from Columbia University in New York. Her publications include Russia and the Classics: Poetry’s Foreign Muse (2009) and Vergil in Russia: National Identity and Classical Reception (2014). She has edited a special issue of Classical Receptions Journal, entitled ‘Classical Reception in Eastern and Central Europe’ to which she also contributed an essay on Joseph Brodsky’s reception of Virgil’s Eclogues.

Classical Receptions Journal covers all aspects of the reception of the texts and material culture of ancient Greece and Rome from antiquity to the present day. It aims to explore the relationships between transmission, interpretation, translation, transplantation, rewriting, redesigning and rethinking of Greek and Roman material in other contexts and cultures. It addresses the implications both for the receiving contexts and for the ancient, and compares different types of linguistic, textual and ideological interactions.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Virgil in Russia appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy literary genres matterThe 9/11 memorial and the Aeneid: misappropriation or sincere sentiment?How to write a classic

Related StoriesWhy literary genres matterThe 9/11 memorial and the Aeneid: misappropriation or sincere sentiment?How to write a classic

May 25, 2014

The Normal Heart and the resilience of the AIDS generation

On 25 May 2014 and nearly 30 years after first appearing on the stage, Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart will be aired as a film on HBO. This project, which has evolved over the course of the last three decades, documents those first few harrowing years of the AIDS epidemic in New York City. The Normal Heart debuts at a time when much attention is being cast upon the early days of AIDS and the lives of gay men, who survived the physical and emotional onslaught of this disease in a society that often shunned us because we were gay and because we were afflicted with this disease.

Now a generation of gay men, my generation—the AIDS Generation—stands proudly as testament to our individual and collective resilience which has brought us all into middle age. Certainly there have been huge hurdles along the way—too many deaths to enumerate, the havoc that the complications of this disease wreaked on our bodies, the lack of support. Even today, darkness and disrespect lurks in every corner, and no one is immune. For some in our society, identifying what is wrong with us as gay men comes to easily. We are reminded of it daily as right wing zealots fight against marriage equality, as young boys take their lives. Despite these conditions, despite the inaction of our national and local politicians, and despite a large yet ever-shrinking segment of our society that continues to view us as weak and sick, we stand together as a testament to the fortitude of our bodies, minds, and spirits.

The theme of resistance or resilience permeates the words, the thoughts, and the actions of the protagonists in The Normal Heart and many depictions of the AIDS epidemic.

Taylor Kitsch as GMHC President President Burce Niles in HBO’s The Normal Heart. (c) HBO via thenormalheart.hbo.com

Behavioral and psychological literature has attempted to delineate sources of resilience. Dr. Gail Wagnild posits that social supports in the form of families and communities foster resilience in individuals. I also adhere to this idea. Although the sources of resilience are still debated in the literature, there is general agreement that resilience is a means of maintaining or regaining mental health in response to adversity the ability to respond to and/or cope with stressful situations such as trauma, conditions that characterize the life of the men of the AIDS Generation.

For many of the men of the AIDs Generation, grappling with their sexuality was closely tied to the development of their resilience. In other words, resilience developed in their childhoods as young men grappling with their sexuality as stated by Christopher: “I also think that wrestling with my own sexuality and trying to navigate through that in my teenage years taught me how to just ‘keep pushing’ and to do what needed to be done.” Some, including myself, found support among our families. Even if parents were loving and supportive, this did not ameliorate the burdens experienced being raised in a heteronormative and often-discriminatory world in which men were portrayed as weak, effeminate, and sickly.

As we watch The Normal Heart, we will be reminded of those dark, confusing early days of the epidemic. And while we must celebrate the resilience of a generation of gay men to fight this disease, we must also be reminded of our obligation to create a better world for a new generation of gay men, who despite our social and medical advances, need the love and support of their community of elders as the navigate the course of their lives.

Perry N. Halkitis, PhD, MS, MPH is Professor of Applied Psychology and Public Health (Steinhardt School), and Population Health (Langone School of Medicine), Director of the Center for Health, Identity, Behavior & Prevention Studies, and Associate Dean (Global Institute of Public Health) at New York University. Dr. Halkitis’ program of research examines the intersection between the HIV epidemic, drug abuse, and mental health burden in LGBT populations, and he is well known as one of the nation’s leading experts on substance use and HIV behavioral research. He is the author of The AIDS Generation: Stories of Survival and Resilience. Follow him on Twitter @DrPNHalkitis.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Normal Heart and the resilience of the AIDS generation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat role does symmetry play in the perception of 3D objects?“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to EuropeMake your own percussion instruments

Related StoriesWhat role does symmetry play in the perception of 3D objects?“There Is Hope for Europe” – The ESC 2014 and the return to EuropeMake your own percussion instruments

May 24, 2014

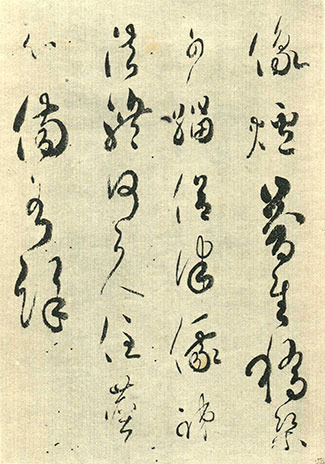

Kotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of language

In Japan, there is a common myth of the spirit of language called kotodama (言霊, ことだま); a belief that some divine power resides in the Japanese language. This belief originates in ancient times as part of Shintoist ritual but the idea has survived through Japanese history and the term kotodama is still frequently mentioned in public discourse. The notion of kotodama is closely linked with Japanese linguistic identity, and the narrative of kotodama has been repeatedly reinterpreted according to non-linguistic factors surrounding Japan, as well as the changing idea of “purity” of language in Japan.

Ancient face

The term kotodama literally means “the spirit of language” (koto = language, dama (tama) = spirit or soul). It is a belief based on the idea of Shintoism, the indigenous religion of Japan which worships divinity in all natural creation and phenomena. In ancient Japan, language was believed to have a spirit, which gives positive power to positive words, negative power to negative words, and impacts a person’s life when his or her name is pronounced out loud. Wishes or curses were thus spelled out in a particular manner in order to communicate with the divine powers. According to this ancient belief, the spirit of language only resides in “pure” Japanese that is unique and free from foreign influence. Therefore, Sino-Japanese loanwords, which were numerous by then and had a great impact on the Japanese language, were eschewed in Shintoist rituals and Japanese native vocabulary, yamatokotoba, was preferred. Under the name of kotodama, this connection between spiritual power and pure language survived throughout Japanese history as a looser concept and was reinvented multiple times.

War-time face

Koku Saityou shounin, written by Emperor Saga. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most significant historical moments in which the myth of kotodama was reinvented was during the Second World War. In order to strengthen national solidarity, the government reintroduced the idea of kotodama, coupling it with the idea of kokutai (国体, こくたい, koku = country or nation, tai = body), the Japanese national polity. The government promoted the idea that the use of “pure” and traditional Japanese language was at the core of the national unity and social virtue that is unique to Japan, while failing to use the right language would lead to violation of the national polity. Under the belief of kotodama, proposals to abolish or reduce the use of kanji (Chinese characters), which had been introduced since the modernization of the country in the second half of the nineteenth century, were fiercely rejected. Instead, the use of kanji as well as traditional non-vernacular orthographic style was encouraged. Furthermore, based on the kotodama myth, the use of Western loanwords was strictly banned as they belonged to the language of the enemy (tekiseigo) and those words were replaced by Sino-Japanese words. For example, the word ragubî, which is the loan from the English word “rugby,” was replaced by tôkyû, a Sino-Japanese word meaning “fight ball.” The word anaunsâ, which is the loan from the English word “announcer,” was replaced by hôsôin, a Sino-Japanese word meaning “broadcasting person.”

It is interesting to note that the kotodama myth was reinvented to encourage the use of Sino-Japanese elements, whereas in the ancient belief the myth promoted the Japanese native elements and eschewed Sino-Japanese elements. In other words, Sino-Japanese was redefined as the essential element of the “pure” and “traditional” Japanese language. Even the movements to simplify the Japanese orthographic system by abolishing the use of Chinese characters and using only kana (phonetic syllabaries) to write Japanese were considered to be violations of kotodama, despite the fact that kana was invented in Japan. This complete reversal of the position of Sino-Japanese elements can be explained by the belief that the increasing use of Western loanwords was creating a new threat to the Japanese linguistic identity. The idea of kokutai, along with other militarist propaganda, was stigmatized in post-war Japanese society and faded away. However, the idea of kotodama survived through the post-war democratization period into contemporary Japan with yet another face.

Contemporary face

You still hear the word kotodama today. A song titled “Ai no Kotodama [Kotodama of Love] – Spiritual Message” performed by a Japanese pop rock band, Southern All Stars, is a well-known hit which has sold over a million since it was recorded in 1996. Above all, one frequently sees the term kotodama used in public debates on the subject of foreign loanwords (gairaigo, which excludes Sino-Japanese loans). For example, an article from a nationwide newspaper stated that “loanwords are threatening the country of kotodama.” Thus the idea of kotodama is still linked to the purity of language in contrast to Western loanwords but, unlike the link between kotodama and political identity of the country made during World War Two, it seems that the myth is now linked to its cultural and social identity while recent waves of globalization have increased the diversity within the contemporary Japan.

The diversity of Japanese society goes hand in hand with the diversity of its vocabulary, which we can see from the rapid increase of loanwords in Japanese. However, at the same time, this increases a sense of insecurity in relation to the linguistic and cultural identity of Japan. As a result, the ancient myth of kotodama has been reinvented as a way to manifest Japanese linguistic identity through the idea of a “pure” language. Kotodama has no fixed definition, and continues to transform as Japanese society undergoes changes. It is questionable if the Japanese still really believe in the spiritual power of language — however, the myth of linguistic purity persists in the mind of the Japanese through the word kotodama.

Naoko Hosokawa is a DPhil candidate in Japanese sociolinguistics at the University of Oxford. A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Kotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of language appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHenry James, or, on the business of being a thingSmall triumphs of etymology: “oof”Charting Amelia Earhart’s first transatlantic solo flight

Related StoriesHenry James, or, on the business of being a thingSmall triumphs of etymology: “oof”Charting Amelia Earhart’s first transatlantic solo flight

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers