Oxford University Press's Blog, page 804

June 8, 2014

How much do you know about the Law of the Sea?

Of the many things in our world that require protection, we sometimes forget the vast expanses of the oceans. However, they are also vulnerable and deserve our protection, including under the law. In recognition of World Oceans Day, we pulled together a collection of international law questions on the Law of the Sea from our books, journals, and online products. Test your knowledge of maritime law!

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How much do you know about the Law of the Sea? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWe’re all data nowWhaling in the Antarctic Australia v. Japan (New Zealand intervening)ASIL/ILA 2014 retrospective

Related StoriesWe’re all data nowWhaling in the Antarctic Australia v. Japan (New Zealand intervening)ASIL/ILA 2014 retrospective

June 7, 2014

What is a book? (humour edition)

As the Amazon-Hachette debate has escalated this week, taking a notably funny turn on the Colbert Report, we’d like to share some funnier reflections on books and the purposes they serve. Here are a few selections from the Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations, Fifth Edition.

“Book–what they make a movie out of for television”

–Leonard Louis Levinson 1904-74: Laurence J. Peter (ed) Quotations for our Time (1977)

“If you don’t find it in the Index, look very carefully through the entire catalogue.”

–Anonymous: in Consumer’s Guide, Sears, Roebuck and Co. (1897); Donald E. Knuth Sorting and Searching (1973)

“Books and harlots have their quarrels in public.”

–Walter Benjamin 1892-1940 German philosopher and critic: One Way Street (1928)

“My desire is … that mine adversary had written a book.”

–Bible: Job

“The covers of this book are too far apart.”

–Ambrose Bierce 1842-c.1914 American writer; C.H. Grattam Bitter Bierce (1929)

“When the [Supreme] Court moved to Washington in 1800, it was provided with no books, which probably explains the high quality of early opinions.”

–Robert H. Jackson 1892-1954 American lawyer: The Supreme Court in the American System of Government (1955)

“One man is as good as another until he has written a book.”

–Benjamin Jowett 1817-93 English classicist: Evelyn Abbott and Lewis Campbell (eds.) Life and Letters of Benjamin Jowett (1897)

“This is not a novel to be tossed aside lightly. It should be thrown with great force.”

–Dorothy Parker 1893-1967 American critic and humorist: R.E. Drennan Wit’s End (1973)

“A thick, old-fashioned heavy book with a clasp is the finest thing in the world to throw at a noisy cat.”

–Mark Twain 1835-1910 American writer: Alex Ayres The Wit and Wisdom of Mark Twain (1987)

“An index is a great leveller.”

–George Bernard Shaw 1856-1950 Irish dramatist: G.N. Knight Indexing (1979); attributed, perhaps apocryphal

“Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine;–they are the life, the soul of reading;–take them out of this book for instance,–you might as well take the book along with them.”

–Laurence Sterne 1713-68 English novelist: Tristram Shandy (1759-67)

“In every first novel the hero is the author as Christ or Faust.”

–Oscar Wilde 1854-1900 Irish dramatist and poet: attributed

Writer, broadcaster, and wit Gyles Brandreth has completely revised Ned Sherrin’s classic collection of wisecracks, one-liners, and anecdotes. With over 1,000 new quotations throughout the media, it’s easy to find hilarious quotes on subjects ranging from Argument to Diets, from Computers to the Weather. Add sparkle to your speeches and presentations, or just enjoy a good laugh in the company of Oscar Wilde, Mark Twain, Joan Rivers, Kathy Lette, Frankie Boyle, and friends. Gyles Brandreth is a high profile comedian, writer, reporter on The One Show and keen participant in radio and TV quiz shows.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bookcase. Public domain via Pixababy.

The post What is a book? (humour edition) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is a book?How did writing begin?Which book changed your life?

Related StoriesWhat is a book?How did writing begin?Which book changed your life?

What kind of Lena Younger would Diahann Carroll have been?

In February, fans learned that Diahann Carroll had withdrawn from A Raisin in the Sun. The most recent revival of Lorraine Hansberry’s award-winning 1959 drama opened in April, and is now nominated for five Tony awards. Carroll relinquished her role as Lena Younger, the widowed matriarch in an African-American family living on the South Side of Chicago, due to the “demands of the vigorous rehearsal schedule and the subsequent eight-performances-a-week playing schedule,” according to a spokesperson for Raisin. The 78-year-old Carroll’s choice is easy to understand, but it also invites the question — what kind of Lena Younger might Carroll have been? How would an actress long known for her elegance and haute couture wardrobe have shed the trappings of high fashion to take on the part of a working class black mother who wants to use her dead husband’s insurance money to buy a home and improve the life of her family?

Diahann Carroll in 1976. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Last August, when the news broke that Carroll and Denzel Washington would have lead roles in this version of Raisin—with Carroll as mother to Washington’s Walter Lee Younger—much was made of their combined star power and the iconic Carroll’s return to Broadway for the first time in 30 years (as well as Washington’s age; the 59-year old portrays a much younger man, though the character has “aged” in this version). In some ways, though, it’s hard to know why the producers looked to Carroll in the first place. Carroll is older than most actresses who have played Lena Younger. Even more, ever since a still-teenage Carol Diahann Johnson changed her name to Diahann Carroll and left the home of her middle class parents, she has been known as a “chic chanteuse.” The link between Carroll and glamour became entrenched as her career ascended: when she sang at the Persian Room or the Plaza Hotel in the late 1950s, in her role as a high class and well-dressed model in the Broadway show No Strings in 1962 (for which she earned a Tony award), and when she portrayed a respectable, and well-dressed school teacher who travels to Paris with her white friend in the film Paris Blues in 1964 (alongside costars Sidney Poitier, Paul Newman, and Joanne Woodward). But the singer and actress soared to national prominence with Julia, a television series that ran from 1968-1971. Here Carroll was cast as the well-dressed middle class nurse and widowed mother of a young boy (her husband was killed in Vietnam). Julia was one of the first television series in which a black woman had a starring role and was not a maid or domestic. The show was an opportunity for Carroll to gain unprecedented exposure on a number-one ranking series — one that was “slightly controversial” she said, because it integrated the living rooms of white audiences through television, but was not controversial enough to “interfere with the ratings.”If Julia cemented Carroll’s reputation as a barrier-breaking international celebrity, it also in some senses profoundly limited her career. Indeed, the first time Carroll played against type after Julia, her efforts had mixed results. In 1974, she starred in Claudine. The film was set in Harlem, and Carroll portrayed the 36-year-old single mother of six on welfare who struggles to combine motherhood and romance (with James Earl Jones, as garbage man Rupert Marshall). Claudine was notable for its critique of a welfare system that policed working class black women, and its portrayal of a single black mother who loves and cares for her children even if she also curses and beats her daughter in one scene. More remarkably, for the time, the film showed that a poor black unmarried woman could be sexually active and a good mother. With its largely African American cast and urban landscape, and with a contemporary soundtrack featuring Gladys Knight and the Pips, Claudine stood out as a rare alternative to the more violent and (mostly) male-centered blaxploitation films that were popular in the early 1970s. A critic in the Chicago Defender applauded it as a film that could “uplift” those who had “been ignored on film until now, the ADC mother” (ADC was the acronym for Aid to Dependent Children, and shorthand for welfare in that era). Carroll’s performance as Claudine earned her an Academy Award nomination for best actress in a leading role—only the fourth time a black woman had ever been nominated in that category.

But fans and critics were divided in their response to Carroll, precisely because the role was such a departure. Some applauded her for being willing and able to take on the role of Claudine. (She inherited the part from actress Diana Sands, ill with cancer in the 1970s but who had starred in the original production of Raisin in 1959, another link between Claudine and Raisin.) A “deglamorized Diahann Carroll is surprisingly effective as a 36-year old city wise and world weary mother who battles welfare department bureaucracy,” wrote one reviewer. Many more came to the opposite conclusion, asserting that Carroll did not have the life experiences to represent working class black women and could not tell their stories with any degree of authenticity. “Even without makeup, she still looks and acts like Julia,” wrote one; Time attacked the star for a “slumming expedition by a woman best known for playing the upwardly mobile Julia on TV.” With her family’s middle class background and her long association with well-dressed and glamorous heroines, Carroll simply could not “presume to speak for all black women.” The Oscar nomination was a significant milestone, but it did not open many doors thereafter; Carroll later said that she felt that her career floundered after Claudine.

Certainly, the question of who gets to tell black women’s stories is no less fraught in 2014 than it was in 1974—as critiques of the film The Help (2011) for hijacking black women’s voices, protests that actress Zoe Saldana is not the right artist to portray singer Nina Simone in a forthcoming biopic, and more recent debates about Beyoncé all begin to suggest. For decades, Diahann Carroll has been at the center of these debates—from her role as a model in an interracial romance in the Broadway play No Strings, to her role as Dominque Deveraux on the nighttime soap opera Dynasty in the 1980s– the “first black bitch on television” as Carroll herself put it. Would Carroll have encountered the same resistance today that she did forty years earlier? Would she have been able to navigate that chasm between her off-stage aura of glamour and an on-stage role of a weary yet strong working class woman who dreams about owning a home more easily in 2014 than she did in 1974? And would media-savvy audiences today, tuned into the ways that any public person is always performing some version of him or herself, have been more open to Carroll and what she could have brought to Lena with her decades of stardom than they were to the former “Julia” when she transformed into the working class Claudine? I respect Carroll’s choice to withdraw from Raisin, and the splendid Latanya Richardson Jackson has infused the part of Lena Younger with a humanity and dignity. But with the Tony awards season underway and with Carroll’s under-rated but sensitive and subversive portrayal of a poor black woman in the film Claudine in mind, I also can’t help but regret what we’ve all missed out on.

Ruth Feldstein is Associate Professor of History at Rutgers University, Newark. She is the author of How it Feels to Be Free: Black Women Entertainers and the Civil Rights Movement.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only theatre and dance articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What kind of Lena Younger would Diahann Carroll have been? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy we watch the Tony AwardsJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever sawDiscussing Josephine Baker with Anne Cheng

Related StoriesWhy we watch the Tony AwardsJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever sawDiscussing Josephine Baker with Anne Cheng

1914-1918: the paradox of semi-modern war

The looming centennial of the Great War has inspired a predicable abundance of conferences, books, articles, and blog posts. Most are built on a familiar meme: the war as a symbol of futility. Soldiers and societies alike are presented as victims of flawed intentions and defective methods, which in turn reflected inability or unwillingness to adapt to the spectrum of innovations (material, intellectual, and emotional), that made the Great War the first modern conflict. That perspective is reinforced by the war’s rechristening, backlit by a later and greater struggle, as World War I—which confers a preliminary, test-bed status.

[image error]

Homeward bound troops pose on the ship’s deck and in a lifeboat, 1919. The original image was printed on postal card (“AZO”) stock. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In point of fact, the defining aspect of World War I is its semi-modern character. The “classic” Great War, the war of myth, memory, and image, could be waged only in a limited area: a narrow belt in Western Europe, extending vertically five hundred miles from the North Sea to Switzerland, and horizontally about a hundred miles in either direction. War waged outside of the northwest European quadrilateral tended quite rapidly to follow a pattern of de-modernization. Peacetime armies and their cadres melted away in combat, were submerged by repeated infusions of unprepared conscripts, and saw their support systems, equine and material, melt irretrievably away.

Russia and the Balkans, the Middle East, and East Africa offer a plethora of case studies, ranging from combatants left without rifles in Russia, to the breakdown of British medical services in Mesopotamia, to the dismounting of entire regiments in East Africa by the tsetse fly. Nor was de-modernization confined to combat zones. Russia, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and arguably Italy, strained themselves to the breaking point and beyond in coping with the demands of an enduring total war. Infrastructures from railways to hospitals to bureaucracies that had functioned reasonably, if not optimally, saw their levels of performance and their levels of competence tested to destruction. Stress combined with famine and plague to nurture catastrophic levels of disorder, from the Armenian genocide to the Bolshevik Revolution.

Semi-modernity posed a corresponding and fundamental challenge to the wartime relationship of armed forces to governments. In 1914, for practical purposes, the warring states turned over control to the generals and admirals. This in part reflected the general belief in a short, decisive war—one that would end before the combatants’ social and political matrices had been permanently reconfigured. It also reflected civil authorities’ lack of faith in their ability to manage war-making’s arcana—and a corresponding willingness to accept the military as “competent by definition.”

Western Battle Front 1916. From J. Reynolds, Allen L. Churchill, Francis Trevelyan Miller (eds.): The Story of the Great War, Volume V. New York. Specified year 1916, actual year more likely 1917 or 1918. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The extended stalemate that actually developed had two consequences. A major, unacknowledged subtext of thinking about and planning for war prior to 1914 was that future conflict would be so horrible that the home fronts would collapse under the stress. Instead, by 1915 the generals and the politicians were able to count on unprecedented –and unexpected–commitment from their populations. The precise mix of patriotism, conformity, and passivity underpinning that phenomenon remains debatable. But it provided a massive hammer. The second question was how that hammer could best be wielded. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, neither soldiers nor politicians were up to the task. In Germany the military’s control metastasized after 1916 into a de facto dictatorship. But that dictatorship was contingent on a victory the armed forces could not deliver. In France and Britain, civil and military authorities beginning in 1915 came to more or less sustainable modi vivendi that endured to the armistice. Their durability over a longer run was considered best untested.Even in the war’s final stages, on the Western Front that was its defining theater, innovations in methods and technology, could not significantly reduce casualties. They could only improve the ratio of gains. The Germans and the Allies both suffered over three-quarters of a million men during the war’s final months. French general Charles Mangin put it bluntly and accurately: “whatever you do, you lose a lot of men.” In contemplating future wars—a process well antedating 11 November 1918—soldiers and politicians faced a disconcerting fact. The war’s true turning point for any state came when its people hated their government more than they feared their enemies. From there it was a matter of time: whose clock would run out first. Changing that paradigm became—and arguably remains—a fundamental challenge confronting a state contemplating war.

Dennis Showalter is professor of history at Colorado College, where he has been on the faculty since 1969. He is Editor in Chief of Oxford Bibliographies in Military History, wrote “World War I Origins,” and blogged about “The Wehrmacht Invades Norway.” He is Past President of the Society for Military History, joint editor of War in History, and a widely-published scholar of military affairs. His recent books include Armor and Blood: The Battle of Kursk (2013), Frederick the Great: A Military History (2012), Hitler’s Panzers (2009), and Patton and Rommel: Men of War in the Twentieth Century (2005).

Developed cooperatively with scholars worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 1914-1918: the paradox of semi-modern war appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReflecting on the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landingsJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever sawFootball arrives in Brazil

Related StoriesReflecting on the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landingsJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever sawFootball arrives in Brazil

June 6, 2014

Which book changed your life?

We’re continuing our examination of what a book is this week, following the cultural debate that the Amazon-Hachette dispute has set off, with something a little closer to our hearts. We’ve compiled a brief list of books that changed the lives of Oxford University Press staff. Please share your books in the comments below.

Jonathan Kroberger, Publicist:

Jonathan Kroberger, Publicist:

A Wrinkle In Time by Madeleine L’Engle

A Wrinkle In Time was the first book to change my life, the one that set me up for all the others that continue to do so. My parents read to me for as long as I can remember but this was the first book I found independently in the school library. It sounds cliché, but reading it felt absolutely like stumbling onto a place that was just my own. That feeling of reading as independence continues to be one of the main reasons I value reading as much as I do.

Annabel Daly, Senior Marketing Manager:

Gift from the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh

This paragraph, while not necessarily my favourite, reminds me of why I love it and why it changed me:

And then, some morning in the second week, the mind wakes, comes to life again. Not in a city sense – no – but beach-wise. It begins to drift, to play, to turn over in gentle careless rolls like those lazy waves on the beach. One never knows what chance treasures these easy unconscious rollers might toss up, on the smooth white sand of the conscious mind; what perfectly rounded stone, what rare shell from the ocean floor. Perhaps a channelled whelk, a moon shell, or even an argonaut.

Ryan Cury, Assistant Marketing Manager:

An Actor Prepares by Constantin Stanislavski

When I was 14 years old, merely a freshman in high school, I had the opportunity to portray Jem Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird at the Barter Theater–the state theater of Virginia, located in the small town of Abingdon, Virginia where I grew up. As a child actor, I was assigned an adult actor who would serve as a mentor to me throughout the entirety of the run of the show: from costume fittings to the final bow. This mentor would be a leader, an older “brother” or “sister,” essentially someone to look up to. The week before we opened the show, my mentor (who was portraying Boo Radley), gave me the book An Actor Prepares by Constantin Stanislavski–a critical read to every actor’s beginning. I flew through the book. Every page. While I don’t act regularly anymore, I continue to reference this book and always prominently place it up front on my book shelf. Inside the front cover reads a note from my mentor that I will always cherish. It brings me to a place where I learned to be vulnerable and grow not only as an actor, but as an individual.

Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth

Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth

A revolutionary book was placed into my lap as one of my first projects here at Oxford University Press. A resource book to the transsexual community: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth. As an out, gay male in his 20s, this book continues to considerably have a positive effect on me–the energy behind the scenes is palpable. The cast of characters who built the book, the amazing editor who pieced each intricate story together, and the wonderful teams who work to get the book out there: this title goes far beyond work, standing out to me personally. I understand this community and completely respect the impact it will have in the world. Having had the opportunity to attend the book’s launch party, I will always remember the tears of joy from contributors, guests, and friends. It reminded me that I am not alone in this endeavor. I am very excited to be a part of this book and look forward to see it take off once publishing.

Yasmin Spark, Digital Assistant:

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

The book that changed my life was The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. The novel uses the protagonist to confront the complex internal mechanisms that young black women have to process as they deal with growing up in a society still dominated by state and institutional racism and the way this impacts their self-esteem. Not only was it fantastically written but it was the first empowering black female character I had ever come across. My mum passed it to me and I fully intend to pass it down to my daughters!

Barney Cox, Marketing Executive:

Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

Describing David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas is a near-impossible task. The book is a series of stories set in six different periods — including Colonial Australia, a dystopian clone-filled Seoul, and a post-apocalyptic future of tribes and cannibals — each featuring a protagonist with a comet-shaped birthmark. The time periods could not feel more different from the other, but as you read more, the novel unfurls itself, slowly giving up its secrets, and you begin to realise how the stories and the lives within them are linked together across time and space. “Souls cross ages like clouds cross skies” is the central premise — and it’s a heart-breakingly beautiful one, the idea of lovers meeting again and again in different worlds and times, of people linked to each other across hundreds and thousands of years, or of having lived past lives they’re only dimly aware of. I haven’t done it justice in this description, but it’s just the tonic for whenever I might have a bad case of the existentialist blues. In one scene, a character angrily tells another that his life will only amount to “one drop in a limitless ocean”, to which the other replies “Yet, what is any ocean but a multitude of drops?” Enough said.

Hannah Charters, Senior Marketing Executive:

His Dark Materials trilogy by Philip Pullman

I always had a love of reading as a child, but the book (or set of books) which turned that love into a passion that formed my future choices (from a university degree in English Literature to my career path in publishing) was Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy. This set of three books (Northern Lights, The Subtle Knife, and The Amber Spyglass) is based in a universe where humans have dæmons, an animal-shaped being who represents the true inner-self, polar bears are armoured and can talk, and witches roam the skies. I got lost in these books that followed two children, Lyra and Will, through parallel worlds, discovering along with them what they learnt: about themselves, their world, and the people around them. I learnt more later, as I grew older, about the religious significances and literary undertones (much of the plot is influenced by John Milton’s Paradise Lost), furthering my love of the books, their characters, and the literary world they sat in.

Andy Allen, Marketing Manager:

Andy Allen, Marketing Manager:

The Beach by Alex Garland

When I read this book, I think I was looking for something to read on a long train journey or something and this just happened to be around. I think the fact that I was at a loose end after finishing university was perfect timing, as it contributed to me deciding to then go traveling around Southeast Asia for a few months. Even though it wasn’t the best book I have ever read it probably has been the most influential. (I didn’t find any secret beaches.)

The 4-Hour Work Week by Timothy Ferriss

While I haven’t read this book, the title alone has sold it to me, and if true, would actually be a life changer! Although I guess you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover; maybe I am a sucker for a get rich quick scheme.

Caitie-Jane Cook, Marketing Executive:

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh

Growing up in Scotland, I felt a sense of distance when told that I would be studying English Literature as a core subject. Although “Scottish play” Macbeth had a pivotal role in the higher curriculum, I was disappointed there wasn’t anything closer to home, more ‘real’. When given free rein to select texts for my final-year portfolio, I was immediately drawn towards Trainspotting. Although sometimes brutal, I found Irvine Welsh’s representation of Mark Renton and friends’ experience of heroin addiction captivating and oddly charming. Most importantly, it was written primarily in Scots. I then went on to study English Language at university, taking special interest in the relative status of the Scots language and why it’s often dismissed as “slang”. I now recognise Welsh’s writing as the source of this linguistic fascination; Trainspotting made me realise that Scots is a language worthy of its own literature.

Ibrahim Siddo, Data Controller:

L’Étrange destin de Wangrin by Amadou Hampaté Bâ

I have selected this one because it’s basically one of the first books I read (I am sure it was over 15 years ago!). It’s about the fortunes (destiny) of an interpreter during the French West African colonial period who had to live between two ‘worlds’ and take/make difficult decisions/choices…

« Wangrin était filou, certes, mais son âme n’était pas insensible. Son cœur était habité par un intense volonté de gagner de l’argent par tous les moyens afin de satisfaire une convoitise innée, mais il n’était point dépourvu de bonté, de générosité et même de grandeur. Les pauvres et tous ceux auxquels ils étaient venus en aide dans le secret en savaient quelque chose. Son comportement, cynique envers les puissants et les favorisés de la fortune, ne manquait cependant jamais d’une certaine élégance. »

Kirsty Doole, Publicity Manager:

Kirsty Doole, Publicity Manager:

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Reading Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë when I was 16 is an experience that has stayed with me. Being 16 and a goth, I thought I understood it in a way that no one else ever had, ever. Of course, that was nonsense, but it was still the book that ignited my interest in Victorian novels — something that I went on to study at university — and it remains a firm favourite of mine. I love the characters, the multi-generational scope, and, of course, Emily’s powerful descriptions of the Yorkshire moors. Going back to it, as I do periodically, is like meeting up with an old friend again.

Alyssa Bender, Marketing Coordinator:

The Harry Potter series

Not necessarily one book that I’d say changed my life but seven: the Harry Potter series. I can single-handedly attribute my love of reading to these books. They turned me into a voracious reader and turned me on to so many other books over the years. As I grew up and the later books started coming out, they provided a fun online community as well as endless conversations and release parties with high school friends. Now, they are a source of nostalgia and are immensely enjoyable every time I return to them. I don’t think I would be the avid reader I am today without them.

Alana Podolsky, Associate Publicist:

1984 by George Orwell

When assigned George Orwell’s 1984 in ninth grade, I probably joined my fellow classmates in groans when the tome hit our desks. That quickly changed for me. I remember 1984 as the book that transformed me from a young reader interested only in plot and character to an adult reader that values art as politics and narrative construction. Orwell of course is brilliant, but 1984 went farther in teaching me that reading can be political and that through reading, you can experience the world.

Georgia Mierswa, Marketing Coordinator:

Brokeback Mountain by Annie Proulx

Regardless of its unassuming size, or its status as a “short story,” Annie Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain moved me beyond words. The surprise of this story, for me, was not that two cowboys fell in love; rather, that Proulx successfully paints a complex thirty-year-long relationship, one based on anger, guilt, and fear of being found out, in less than 60 pages. Their love is violent and pained: when they kiss, they draw blood. A hug turns into a wrestling match in which Jack’s knee connects with Ennis’ nose. These small moments speak volumes about their internal struggle—as trapped men in a prejudiced place. When I reached Ennis’s final line, a quote as gut-wrenching and unrealized as their affair (“Jack, I swear—”), I was in tears. Brokeback Mountain is more honest about love, and the anguish of forbidden relationships, than any work I’ve ever read.

Jacqueline Baker, Senior Commissioning Editor, Literature:

Jacqueline Baker, Senior Commissioning Editor, Literature:

Mara and Dann by Doris Lessing

I picked up a copy of Doris Lessing’s Mara and Dann (first published in the UK in 1999) in a scuffed paperback edition sitting on the shelves of a holiday apartment in the hot and dry region of the Var in the south of France in the summer of 2005. I had packed books that I intended to read in my suitcase, but felt like something different and was perusing the resident bookcase. Mara and Dann, brother and sister, live at the southern end of all large land mass called Ifrik. It’s an imagined place set in a post-cataclysmic era and the reader has to piece together the background to their decision to flee from their home and family in the middle of the night. They find themselves in a poor rural village and join the general fight to survive the hardships of a life threatened by drought, wild animals, and hostility from the Rock People. Reading it in the south of France in the extreme arid heat and a foreboding sense of climate change hanging over me as the helicopters circled attempting to put out forest fires must have enhanced the impact of the book – Mara and Dann have to migrate north, away from the southern lands that are turning to dust. All sorts of odd things happen to them, in extremis, and they are separated at several points in the narrative. The odd bond between brother-sister is rather like that between Maggie Tulliver and her brother in George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, but this time life is nightmarish and civilisation a half-remembered human state the only remaining traces of which – a few surviving books – are completely mysterious and undecipherable. The world is returned to its primitive state, but we know that we’re really in the future. It’s a dark, haunting book but there is an extraordinary relationship at its core. The mood and world of the book has stayed with me ever since.

Seth Bitter, Library Sales Associate:

The Lamp from the Warlock’s Tomb by John Bellairs

The first book that I can accurately recall having a profound impact on my life would have to be The Lamp from the Warlock’s Tomb by John Bellairs. I was already an avid reader by the time I came across it, but I was mostly reading the same books that my older siblings had read, and those that were available on our bookshelves at home. The discovery of John Bellairs and his gothic mysteries was one of the first independent steps I took. It gave me a section of the library to dart towards whenever we made our weekly trip, and the ghostly cover illustrations by Edward Gorey only helped to cement their place in my mind.

Alice Northover, Social Media Marketing Manager:

Animal Farm by George Orwell

I wasn’t a great reader as a child, despite my family’s ability to exhaust the local library or our weekly classroom trips to the school library. My childhood was filled with books that people thought I ought to read, whether classics like Black Beauty or the Babysitters Club series, but I never found any of those books appealing. There were certainly a few that touched me (how could you fail to cry at the end of Where the Red Fern Grows?), yet something kept turning me away. Perhaps the weight of expectations in those books left me cold — whether as school assignments, or gifts, or suggestions from kind librarians, or the creeping, patronizing tones of children’s authors I found in so many. Other children loved those books, so clearly I was the problem. So when I was assigned Animal Farm for summer reading at 12-years-old, students were supposed to hate it, to fail to understand it, to find it too advanced (they had a terrible way of introducing summer reading). I was supposed to identify with the other assignment, an insipid — if award-winning — book about some teenager envious of her cancer-stricken sister. Animal Farm was the first book, however, that truly challenged and engaged me. It spoke about systems of power, complex and contradictory people, societies in flux, and politics, real politics; about a world outside my claustrophobic suburbia. And George Orwell did not speak down to me (I doubt he thought 12-year-olds would be reading it in the first place); he expected me to think, to try to understand, and argue, and fight. And it was that expectation that drove me to books, more books, better books, books beyond the expectations of others. It made me a reader.

Which book changed your life? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: A Wrinkle in Time. Trans Bodies, Trans Selves. The Beach. Wuthering Heights.

The post Which book changed your life? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow did writing begin?What is a book?The point of view of the universe

Related StoriesHow did writing begin?What is a book?The point of view of the universe

Reflecting on the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings

In the early morning of 6 June 1944, thousands of men stood in Higgins boats off the coast of Normandy. They could not see around them until the bow ramp was lowered — when it was time for them to storm the Gold, Juno, Sword, Utah, and Omaha beaches. Over 10,000 of them would die in the next 24 hours. The largest amphibious invasion the world has ever seen took place seventy years ago today.

In the videos below, Craig L. Symonds, author of Neptune: The Allied Invasion of Europe and the D-Day Landings, discusses the planning and execution of the invasion. Numerous, often contentious, discussions took place behind the scenes between the United States and the United Kingdom regarding the D-Day invasion strategy. And while most people believe that strategy is the key focus on winning a war, this is not often the case. Rather the concept of logistics often plays a key role in victory, and in this instance, in helping forces succeed in the storming of Normandy beach. Symonds also reveals why it’s so important to learn about the personal histories of those involved in and affected by the allied invasions of World War II, and the story of a remarkable lieutenant by the name of Dean Rockwell who played a pivotal role in the D-Day invasion. You can also learn more by entering our giveaway for signed copies of Craig Symonds’ new book.

What was the Anglo-American debate over invasion strategy?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Why did logistics trump strategy on 6 June 1944?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Why are lesser known personal accounts important to understanding the history of D-Day?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Were there any individual accounts that demonstrated the circumstantial pressures of the invasion?

Click here to view the embedded video.

For the 70th anniversary of D-Day, Oxford University Press is giving away 15 signed copies of Neptune: The Allied Invasion of Europe and the D-Day Landings, by Craig L. Symonds. The contest ends on June 6, 2014, at 5:30pm.

Craig L. Symonds is Professor of History Emeritus at the United States Naval Academy. He is the author of many books on American naval history, including Neptune: The Allied Invasion of Europe and the D-Day Landings, The Battle of Midway and Lincoln and His Admirals, co-winner of the Lincoln Prize in 2009.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Reflecting on the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow did writing begin?Politics and cities: looking at the roots of suburban sprawlAfter the storm: failure, fallout, and Farage

Related StoriesHow did writing begin?Politics and cities: looking at the roots of suburban sprawlAfter the storm: failure, fallout, and Farage

Apples and carrots count as well

By David A. Bender

The food pyramid shows fruits and vegetables as the second most important group of foods in terms of the amount to be eaten each day: 3-5 servings of vegetables and 2-4 servings of fruit. This, and the associated public health message to consume at least 5 servings of fruit and vegetables a day, is based on many years of nutritional research. Fruits and vegetables are rich in vitamins and minerals, as well as many other potentially protective compounds, and low in fat (and especially saturated fat). There is excellent evidence from a great many epidemiological studies that people who consume 5 servings of fruit and vegetables a day are less likely to suffer from atherosclerosis, heart disease, high blood pressure, and many cancers.

Things have changed in my local supermarket now, but until a year or so ago, the “five a day” message appeared above the aisles containing exotic (and expensive) fruits such as mangoes and papaya, but not those containing apples and pears, carrots and parsnips. Now, however, I find a more disturbing difference. If I buy a packet of tomatoes, there is nutritional information on the package, telling me what nutrients are present, and what percentage of my daily requirement a serving contains. Some packages also tell me how much of the produce will provide one of my five servings a day. By contrast, if I buy loose tomatoes there is no nutritional information available. Similarly, when I bought a pineapple last week there was a label around the neck of the fruit, not only telling me it was a pineapple (which I knew), but where it was grown and what nutrients it contained. The next shelf contained mangoes. These had only a small bar code label that would be decoded into a price at the checkout. Three onions in a string bag were labelled with nutrition information; loose onions were not.

All this suggests that I might be misled into believing that while packaged fruits and vegetables are a source of nutrients, loose produce that I select myself from the trays is free from nutrients. Of course, this is not so, but there is anecdotal evidence to suggest that many consumers do indeed believe that unpackaged fresh produce (and indeed unpackaged meat and fish from the counter) are not nutritious, since there is no associated labelling.

It is difficult to know what to do about this. It is not likely that shoppers would read a list of nutrition information on a poster above the loose produce – indeed, it would be very annoying if people were standing reading the posters above the produce that I wanted to select. It is annoying enough when someone blocks my access to the shelves by phoning home to ask whether we should have this or that for dinner tonight. One answer might be to expand the labels on loose fruits and vegetables to include a QR code that can be read into a smart phone. I notice that my pineapple label contains a QR code that will download recipes to use pineapple to my smart phone. Perhaps QR codes could be printed on the supermarket receipt – but that is long enough already, listing every item, how much I have saved by buying special offers and “twofers”, how many loyalty points I have earned to date, how many points I have donated to charity by using my own bags, etc.

Another trend is the marketing of some fruits and vegetables as superfoods, implying that they are in some way more nutritious than other produce. Of course, different fruits and vegetables do indeed differ in their nutrient content. Blackcurrants and acerola cherries are extremely rich sources of vitamin C, containing very much more than strawberries or apricots. However, this does not imbue them with “super” status as part of a mixed diet.

The concept of superfoods was developed in the USA in 2003-4 and was introduced in Britain by an article in the Daily Mail on 22 December 2005. Superfoods are just ordinary foods that are especially rich in nutrients or antioxidants and other potentially protective compounds, including polyunsaturated fatty acids and dietary fibre.

Scanning through a handful of websites thrown up by a Google search for “superfoods” gives the following list almonds, apples, avocado, baked beans, bananas, beetroot, blueberries, Brazil nuts, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, carrots, cocoa, cranberries, flax seeds, garlic, ginger, kiwi, mango, olive oil, onions, oranges, peppers, pineapple, pumpkin, red grapes, salmon, soy, spinach, strawberries, sunflower seeds, sweet potato, tea, tomatoes, watercress, whole grain seeded bread, whole grains, wine, yoghurt.

There are very few surprises in this list (apart perhaps from the inclusion of wine as a superfood, although red wine is a rich source of antioxidants, and there is some, limited, evidence that modest alcohol consumption is beneficial). Most of these are foods that nutritionists and dietitians have talked about for years as being nutrient dense – i.e. they have a high content of vitamins and minerals. The nuts, seeds, and olive oil are an exception, but they are all good sources of polyunsaturated fatty acids.

The labelling and marketing of the foods as superfoods seems disingenuous (or a clever marketing strategy), but if such marketing leads people to eat more fruit and vegetables and reduce their saturated fat, salt and sugar intake then it can only help to reinforce the message that the nutrition and public health communities have been preaching for more than a quarter of a century.

David Bender graduated in Biochemistry from the University of Birmingham in 1968 and gained his PhD in Biochemistry from the University of London in 1971. From 1968 until his retirement in 2010 he was a member of academic staff of the Middlesex Hospital Medical School, and then, following a merger, of University College London, teaching nutrition and biochemistry, mainly to medical students. He is Emeritus Professor of Nutritional Biochemistry at University College London. He is the author of Nutrition: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Food Pyramid, drawn by the author David Bender

The post Apples and carrots count as well appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMorality, science, and Belgium’s child euthanasia lawTen landscape designers who changed the world15 facts on African religions

Related StoriesMorality, science, and Belgium’s child euthanasia lawTen landscape designers who changed the world15 facts on African religions

June 5, 2014

How did writing begin?

We’re continuing our discussion of what is a book today with some historical perspective. The excerpt below by Andrew Robinson from The Book: A Global History gives some interesting insight into how the art of writing began.

Without writing, there would be no recording, no history, and of course no books. The creation of writing permitted the command of a ruler and his seal to extend far beyond his sight and voice, and even to survive his death. If the Rosetta Stone did not exist, for example, the world would be virtually unaware of the nondescript Egyptian king Ptolemy V Epiphanes, whose priests promulgated his decree upon the stone in three scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and (Greek) alphabetic.

How did writing begin? The favoured explanation, until the Enlightenment in the 18th century, was divine origin. Today, many—probably most—scholars accept that the earliest writing evolved from accountancy, though it is puzzling that such accounts are little in evidence in the surviving writing of ancient Egypt, India, China, and Central America (which does not preclude commercial record-keeping on perishable materials such as bamboo in these early civilizations). In other words, some time in the late 4th millennium bc, in the cities of Sumer in Mesopotamia, the ‘cradle of civilization’, the complexity of trade and administration reached a point where it outstripped the power of memory among the governing elite. To record transactions in an indisputable, permanent form became essential.

Fragment of an inscripted clay cone of Urukagina (or Uruinimgina), lugal (prince) of Lagash. circa 2350 BC. terracotta. Musée du Louvre. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Some scholars believe that a conscious search for a solution to this problem by an unknown Sumerian individual in the city of Uruk (biblical Erech), c .3300 bc, produced writing. Others posit that writing was the work of a group, presumably of clever administrators and merchants. Still others think it was not an invention at all, but an accidental discovery. Many regard it as the result of evolution over a long period, rather than a flash of inspiration. One particularly well-aired theory holds that writing grew out of a long-standing counting system of clay ‘tokens’. Such ‘tokens’—varying from simple, plain discs to more complex, incised shapes whose exact purpose is unknown—have been found in many Middle Eastern archaeological sites, and have been dated from 8000 to 1500 bc. The substitution of two-dimensional symbols in clay for these three dimensional tokens was a first step towards writing, according to this theory. One major difficulty is that the ‘tokens’ continued to exist long after the emergence of Sumerian cuneiform writing; another is that a two-dimensional symbol on a clay tablet might be thought to be a less, not a more, advanced concept than a three-dimensional clay ‘token’. It seems more likely that ‘tokens’ accompanied the emergence of writing, rather than giving rise to writing.

Apart from the ‘tokens’, numerous examples exist of what might be termed ‘proto-writing’. They include the Ice Age symbols found in caves in southern France, which are probably 20,000 years old. A cave at Pech Merle, in the Lot, contains a lively Ice Age graffiti to showing a stenciled hand and a pattern of red dots. This may simply mean: ‘I was here, with my animals’—or perhaps the symbolism is deeper. Other prehistoric images show animals such as horses, a stag’s head, and bison, overlaid with signs; and notched bones have been found that apparently served as lunar calendars.

‘Proto-writing’ is not writing in the full sense of the word. A scholar of writing, the Sinologist John DeFrancis , has defined ‘full’ writing as a ‘system of graphic symbols that can be used to convey any and all thought’—a concise and influential definition. According to this, ‘proto-writing’ would include, in addition to Ice Age cave symbols and Middle Eastern clay ‘tokens’, the Pictish symbol stones and tallies such as the fascinating knotted Inca quipus, but also contemporary sign systems such as international transportation symbols, highway code signs, computer icons, and mathematical and musical notation. None of these ancient or modern systems is capable of expressing ‘any and all thought’, but each is good at specialized communication (DeFrancis, Visible Speech, 4).

Andrew Robinson is the author of some 25 books in the arts and sciences including Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction and Cracking the Egyptian Code: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion. He is a contributor to The Book: A Global History, edited by Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H. R. Woudhuysen.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How did writing begin? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is a book?Mormon pioneer polygamous wives [infographic]The point of view of the universe

Related StoriesWhat is a book?Mormon pioneer polygamous wives [infographic]The point of view of the universe

The point of view of the universe

We are constantly making decisions about what we ought to do. We have to make up our own minds, but does that mean that whatever we choose is right? Often we make decisions from a limited or biased perspective.

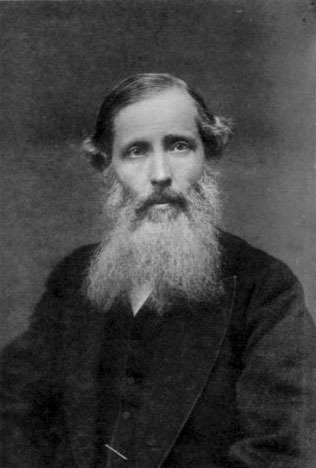

The nineteen century utilitarian philosopher Henry Sidgwick thought that it is possible for us to reach, by means of reasoning, an objective standpoint that is detached from our own perspective. He called it “the point of view of the universe”. We used this phrase as the title of our book, which is a defense of Sidgwick’s general approach to ethics and to utilitarianism. On one important problem we suggest a correction that we believe makes it possible to overcome a difficulty that greatly troubled him.

We argue that reason is capable of presenting us with objective, impartial, non-natural reasons for action. We agree with Sidgwick that only the presupposition that reasons are objective enables us to make sense of the disagreements we have with other people about what we ought to do, and the way in which we respond to them by presenting them with reasons for our views. Those who deny that we can have objective reasons for action claim that all reasons for action start from desires or preferences.

If we were to accept this view, we would also have to accept that if we have no preferences about the welfare of distant strangers, or of animals, or of future generations, then we have no reason to do anything to help them, or to avoid harming them (as, for example, we are harming future generations by continuing to emit greenhouse gases). We hold that people do have reasons to help distant strangers, animals, and future generations, irrespective of our preferences regarding their welfare.

If objective moral reasoning is possible, how does it get started? Sidgwick’s answer is, in brief, that it starts with a self-evident intuition. He does not mean by this, however, the intuitions of what he calls “common sense morality.” To see what he does mean, we must draw a distinction between intuitions that are self-evident truths of reason, and a very different kind of intuition. This distinction will become clearer if we look at an objection to the idea of moral intuition as a source of moral truth.

If objective moral reasoning is possible, how does it get started? Sidgwick’s answer is, in brief, that it starts with a self-evident intuition. He does not mean by this, however, the intuitions of what he calls “common sense morality.” To see what he does mean, we must draw a distinction between intuitions that are self-evident truths of reason, and a very different kind of intuition. This distinction will become clearer if we look at an objection to the idea of moral intuition as a source of moral truth.

Sidgwick was a contemporary of Charles Darwin, so it is not surprising that already in his time the objection was raised that an evolutionary view of the origins of our moral judgments would completely discredit them. Sidgwick denied that any theory of the origins of our capacity for making moral judgments could discredit the very idea of morality, because he thought that no matter what the origin of our moral judgments, we will still have to decide what we ought to do, and answering that question is a worthwhile enterprise.

On the other hand, he agreed that some accounts of the origins of particular moral judgments might suggest that they are unlikely to be true, and therefore discredit them. We defend this important insight, and press it further. Many of our common and widely shared moral intuitions are the outcome of evolutionary selection, but the fact that they helped our ancestors to survive and reproduce does not show them to be true.

This might be taken as a ground for skepticism about morality as a whole, but our capacity for reasoning saves morality from this skeptical critique. The ability to reason has, of course, evolved, and clearly confers evolutionary advantages on those who possess it, but it does so by making it possible for us to discover the truth about our world, and this includes the discovery of some non-natural moral truths.

Sidgwick thought that his greatest work was a failure because it concluded by accepting that both egoism and universal benevolence were rational. Yet they pointed to different conclusions about what we ought to do. We argue that the evolutionary critique of some moral intuitions can be applied to egoism, but not to universal benevolence. The principle of universal benevolence can be seen as self-evident, once we understand that our own good is, from “the point of view of the universe” of no more importance than the similar good of anyone else. This is a rational insight, not an evolved moral intuition.

In this way, we resolve the so-called “dualism of practical reason.” This leaves us with a utilitarian reason for action that can be presented in the form of a utilitarian principle: we ought to maximize the good generally.

What is this good thing that we should maximize? Is my having a positive attitude towards something enough to make bringing it about good for me? Preference utilitarians have argued that it is, and one of us has, for many years, been well-known as a representative of that view.

Sidgwick, however, rejected such theories, arguing that the good must be, not what I actually desire but what I would desire if I were thinking rationally. He then develops the view that the only things that it is rational to desire for themselves are desirable mental states, or pleasure, and the absence of pain.

For those who hold that practical reasoning must start from desires, it is hard to understand the idea of what it would be rational to desire – or at least, that idea can be understood only in relation to other desires that the agent may have, so as to produce a greater harmony of desire.

This leads to a desire-based theory of the good.

One of us, for many years, became well-known as a defender of one such desire-based theory, namely preference utilitarianism. But if reason can take us to a more universal perspective, then we can understand the claim that it would be rational for us to desire some goods, even if we have no present desire for them. On that basis, it becomes more plausible to argue for the view that the good consists in having certain mental states, rather than in the satisfaction of desires or preferences.

Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek is a Polish utilitarian philosopher, working as an assistant professor at the Institute of Philosophy at the University of Lodz. Peter Singer is Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University, and a Laureate Professor at the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics at the University of Melbourne; in 2005 Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world. Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer are authors of The Point of View of the Universe.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Henry Sidgwick. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The point of view of the universe appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is a book?Why we watch the Tony AwardsFishing in the “roiling” waters of etymology

Related StoriesWhat is a book?Why we watch the Tony AwardsFishing in the “roiling” waters of etymology

Why we watch the Tony Awards

Awards season brings out everyone’s inner analyst. The moment that nominations are announced, everyone starts trying to figure out what the list of nominees says about the state of whatever medium is being lauded. During the Grammy, Emmy, Academy, and Tony Awards seasons, critics use the nominees to analyze the state of the art, fans align themselves in solidarity behind performers both honored and snubbed, and everyone rushes to hear or see whatever they have missed.

Then, during the awards shows, journalists, bloggers, scholars and fans take to their couches, and break the Internet with rapid-fire opinions about every damn thing on the screen. The next morning, talk centers on who wore what and who said what and who deserved what. People dish in the office and on the phone and on the web. And then, by midweek, no one cares anymore and we’ve all moved on.

While the Tonys (airing this year on Sunday, 8 June at 8 p.m. on CBS) are never watched by as many people as are the Academy Awards, the Emmys, or the Grammys (or even the Country Music Awards, which attracted nearly double the audience of the Tonys in 2013), the same rules apply. This year, Tony talk is particularly fevered because the nominations seem so random. Since late April, journalists, bloggers, and — ahem — scholars have weighed in on what this strange roster says about the sanity of the nominating committee, the implications of the current season for the future of the industry, and, of course, what it means for the State of Commercial Theater in New York.

I’ve seen many of the shows that were nominated this year, along with quite a few that were not, and I can assert — with scholarly authority — that I have absolutely no idea who is going to win anything, or what this year’s nominations say about the State of Commercial Theater in New York or, indeed, on Earth. Don’t believe anyone who claims they do.

Some background: Last year, many nominations went to a relative handful of commercially and critically successful shows like Matilda, Kinky Boots, and Pippin. This year’s list features no clear frontrunners and does not cluster around a handful of top-grossing productions or clear standout performances.

Maybe that is because this year has been comparatively disappointing, at least as far as monster-hit musicals go. The most anticipated spectacles — Rocky, If/Then, and The Bridges of Madison County — failed to connect solidly with critics or audiences. (To be fair, Rocky seems to have connected with people who enjoy watching half-naked guys belt out tunes while punching meat and other half-naked guys. I suppose that counts for something?) As a result, nominations in the Best Musical category went to shows that were reasonably well-received—like Beautiful and A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder—if not critically or commercially ecstatic or particularly aesthetically groundbreaking.

The cast of Beautiful: The Carole King Musical, nominated for Best Musical, photo by Joan Marcus, via BeautifulonBroadway.com

As for plays, while one was completely shut out (Will Eno’s The Realistic Joneses), most have gotten at least a few nods, if not for best play or revival, then for actress, actor, or supporting roles. The biggest surprise to some is the clutch of nominations that went to the Shakespeare’s Globe all-male Twelfth Night, a big hit this past fall. This is particularly big news to people who presume that (a) Broadway audiences are morons, (b) Tony voters are morons, or (c) Shakespeare was a moron.

The other big surprise was the omission of Denzel Washington and Daniel Radcliffe from the Best Leading Actor in a Play category. This might have more to do with the large number of prominent male roles on offer this year than anything else, though New York Times theater critic Ben Brantley gamely suggested recently that Radcliffe and Washington were passed over because they are so very, very good in their roles. Sure, Ben, whatever.

Here’s the thing: While I am sure Radcliffe and Washington were irked by the oversight — along with the producers of If/Then and Rocky and Bridges of Madison County and the rest of the snubbed — the Tonys don’t matter. At least not in the way that people seem to want them to matter.

The awards themselves say nothing, in the long run, about the State of Commercial Theater in New York or, indeed, on Earth. The awards ceremony is meaningful. The actual winning and losing? Not so much. What makes any awards ceremony important is the care and love people put into it. For better or worse, we Americans are world-famous for our commercial entertainment, and in honoring it, we celebrate ourselves.

Tonys are particularly sweet because they give us a break from endless laments about how the theater is dead or dying, too expensive, too inaccessible. For a few weeks in the late spring, we get to celebrate the very fact that Broadway continues to matter at all, regardless of what kind of season it’s been or who walks away with laurels.

So instead of offering a list of predictions, I will tell you what I am hoping to see and celebrate during the festivities on 8 June 2014:

(1) Audra McDonald

The ludicrously talented McDonald could become the first performer to win six Tonys for acting. Also, since Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar and Grill is being considered as a play and not a musical, McDonald could also become the first person to win a Tony in each of the four acting categories (she’s won in the past for Best Actress in a Musical, Best Featured Actress in a Musical, and Best Featured Actress in a Play). This would be great to see, it’s certainly well deserved, and as an added extra, I bet some lucky contractor will be hired to expand her mantelpiece, yet another way that commercial theater boosts the city’s economy! When Audra wins, everybody wins. And if she doesn’t win this year, you can bet she’ll still perform during the broadcast and be typically thrilling, so no one will suffer overmuch one way or the other.

(2) Kelli O’Hara

Like McDonald, O’Hara has been astounding us for quite a while. I would pay to watch her knit a scarf. She even managed to convince me that The Bridges of Madison County — a loathsome novel made into an even more loathsome movie — actually has a right to exist. But unlike McDonald, O’Hara has yet to take home a Tony, which is absolutely unacceptable. O’Hara has been nominated for Best Actress in Musical five times. If she doesn’t win this time around, I can’t promise I won’t fly into an uncontrollable rage and take out my frustration on some poor, unsuspecting soul, probably Robert James Waller.

(3) Mark Rylance

Rylance is nominated for Best Actor (Richard III) and Best Actor in a Featured Role (Twelfth Night). Both times he won in the past, he recited verses by the Minnesota poet Louis Jenkins in lieu of a formal acceptance speech. The poems are irreverent and sweet and often hilarious, and so is Rylance. I hope we get to hear another. Again, though, if he doesn’t win this time, we’ll all survive.

Samuel Barnett (left) and Liam Brennan (right) appear in the Shakespeare’s Globe productions of Twelfth Night and Richard III, via Shakespeare Broadway.

(4) Actors Who Got the Shaft

Last year, Alan Cumming (Macbeth) and Scarlett Johansson (Cat on a Hot Tin Roof) weren’t nominated, but they showed up for the awards ceremony anyway; so did Bebe Neuwirth and Nathan Lane when they were passed over for their work in The Addams Family in 2010. They joked about their respective slights before graciously reading the nominations and handing out trophies. Their grace and aplomb remind us that theater is as often a collaborative art form that depends on trust and sharing as it is a vicious snake-pit of betrayal and recrimination. I hope that Denzel Washington, Daniel Radcliffe, Ian McKellan, and Patrick Stewart all get invited to hand out hardware, and agree to do so, setting aside any ego for the night. Bonus points if Captain Picard and Gandalf appear in their bowler hats, holding hands.

(5) Neil Patrick Harris and Hugh Jackman

If these two men took over the world and repopulated it entirely with their love-children, no one would mind. I hope they hold a fabulous throw-down, judged by the equally awesome and beloved Lin-Manuel Miranda.

In sum: this year’s scattershot nominations make predicting winners tough, but it doesn’t matter. What matters is that the Tony ceremony is going to be on the TV, and I’ll be watching (and snarking, and snacking, and tweeting) with a couple million other people. That strikes me as cause enough for celebration.

Liz Wollman is Associate Professor of Music at Baruch College in New York City, and author of The Theater Will Rock: A History of the Rock Musical, from Hair to Hedwig and Hard Times: The Adult Musical in 1970s New York City.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only theatre and dance articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Poster for Twelfth Night and Richard III from Shakespeare Broadway. Photo of cast of Beautiful by Joan Marcus, via BeautifulonBroadway.com.

The post Why we watch the Tony Awards appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever sawQ&A with James Keller, author of Chamber Music: A Listener’s GuideWhat is a book?

Related StoriesJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever sawQ&A with James Keller, author of Chamber Music: A Listener’s GuideWhat is a book?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers