Oxford University Press's Blog, page 801

June 17, 2014

Composer and cellist Aaron Minsky in 12 questions

We asked our composers a series of questions based around their musical likes and dislikes, influences, challenges, and various other things on the theme of music and their careers. Each month we will bring you answers from an OUP composer, giving you an insight into their music and personalities. Today, we share our interview with composer and cellist Aaron Minsky. Visit his YouTube channel for an insight into the man and his music.

We asked our composers a series of questions based around their musical likes and dislikes, influences, challenges, and various other things on the theme of music and their careers. Each month we will bring you answers from an OUP composer, giving you an insight into their music and personalities. Today, we share our interview with composer and cellist Aaron Minsky. Visit his YouTube channel for an insight into the man and his music.

Which of your pieces are you most proud of and holds the most significance for you?

I am most proud of my concerto, The Conqueror. It utilizes the experience of 30 years of cello performing and composing plus a lifetime of study of the great orchestral works. Written during the immensely threatening Hurricane Sandy, it is imbued with drama and power. The piece is loosely based on the life of Genghis Khan and contains Mongolian-type melodies synthesized with rock cello concepts. I am thrilled with the prospect of seeing it performed in major concert halls. I gave the world premiere this spring in New York City with the Staten Island Philharmonic.

Which composer were you most influenced by and which of their pieces has had the most impact on you?

My solo cello works reveal my debt to J. S. Bach. I considered his Cello Suites the ‘Bible’ of cello composing and loved how he utilized the range of the instrument to create self-standing contrapuntal gems. As great as his suites are, I wanted to create new suites with modern musical influences to carry on the tradition. I knew I could never match the loftiness of Bach, but I felt I could fill a gap in the repertoire with new techniques and styles, and do it with an emphasis on joy!

Can you describe the first piece of music you ever wrote?

Most of my early pieces were songs, but my very first composition was in the style of Mozart. I was aware of the great composers even before I became influenced by the music of my generation.

Have the challenges you face as a composer changed over the course of your career?

The biggest challenge is staying relevant. It’s hard to believe that my first publication with OUP dates back to the 1980s. The Cold War was ending, the dollar was strong, and the Soviet Union was in shambles. The popularity of the United States was at a high and American culture was embraced around the world. In this climate, Ten American Cello Etudes was a perfect fit. Then globalization took hold, multiculturalism became the byword, and Ten International Cello Encores reflected this change. Most recently, Pop Goes the Cello proposes a new popular style of cello playing beyond the confines of any particular region.

If you could have been present at the premiere of any one work (other than your own) which would it be?

The most inspiring premiere that ever took place had to have been Beethoven‘s Ninth. A previous OUPblog describes it this way: ‘Back to the audience, facing the orchestra, the composer steadily marked the tempo with his hands. He was not conducting, though — he was deaf. Thus it was that, when the orchestra and chorus finished, he could not hear the applause and cheers of the Vienna audience. When a musician turned him around so he could see the joy on listeners’ faces, Ludwig van Beethoven bowed in gratitude — and wept.’

What is the last piece of music you listened to?

Whatever was on the radio. I tend to surf around and listen to a wide range of music — from the classics to rock to jazz to world music.

What might you have been if you weren’t a composer?

I might have been a rock star. My early influences were bands that combined classical music with rock such as the Beatles. I was also influenced by improvising bands, like the Grateful Dead. While still in high school I became a professional guitarist. Feeling that Hendrix, Clapton, and a few others had done just about all one could with a guitar I saw the cello as open territory. I was ready to plant my flag when, due to changing musical currents, the curtain fell on experimental rock ending my dream. I remember around that time staring at a picture of Fernando Sor (the great guitar etude writer) and thinking, I may never become a rock star but I bet I could preserve my melodies in cello etudes. Thus the composer seed was planted.

What piece of music have you discovered lately?

After my trip to England last year I was inspired to dig into its great symphonic heritage. I listened to the complete symphonies of Vaughan Williams among others. I have particularly enjoyed Vaughan Williams’s London Symphony (in which I hear shades of one of my heroes, George Gershwin).

Is there an instrument you wish you had learned to play and do you have a favourite work for that instrument?

I wish I had studied keyboards earlier. That would have been helpful for my composing. There are so many great pieces. If I had to pick a favorite I’d say Brahms‘ Second Piano Concerto. But I love many instruments including the french horn, the English horn, the bass clarinet, even the contra-bassoon — all of which are featured in my concerto!

Is there a piece of music you wish you had written?

Of course I wish I had written the Dvořák Cello Concerto. But I am glad to have composed the Minsky and am honored to be following in his footsteps.

What would be your desert island play list? (three pieces)

I would do what I usually do when I travel — listen to the music from where I am. Since this island would be surrounded by the ocean I would listen to the music of the sea! First on my list would be La Mer by Debussy, which captures the bluster of the glorious, churning sea. Then I’d pick A Sea Symphony of Vaughan Williams for its depth and powerful exploration of emotions connected with the sea. Finally, I would pick Jimi Hendrix’s 1983 A Merman I Should Turn to Be for its imaginative depiction of life under the sea.

How has your music changed throughout your career?

This is best answered by taking a trip to my website. I have audio clips of myself as young as 13 years old jamming out on guitar in every rock style I could muster. Some of the songs I wrote at age 14 have held up pretty well. You can hear in the tapes I made from age 16, the onset of classical influences. You can also hear the birth of the ‘celtar’. In the tapes from my college years you hear the influence of jazz, world music, and improvisation. We also hear the early days of my career as a classical cellist. From there my move back into rock can be heard with clips of the Von Cello Band. The website pretty much ends with Von Cello but will soon be updated to show how I have moved back toward classical, especially in my compositions … which brings us back to the first question about which piece I am most proud. I hope my concerto will be just the first step in the next chapter of my life: Aaron Minsky — orchestral composer.

American cellist, Aaron Minsky’s compositions are standard repertoire, his music appearing in the curriculums of the ABRSM, the American String Teachers’ Association, and the Australian Music Examinations Board. Aaron has given masterclasses and performances in the United States, England and Ireland, and has an Australian tour planned for later this summer. Also known as Von Cello, Aaron has appeared on radio and television and has performed with a wide range of artists from David Bowie and Tony Bennett to Mstislav Rostropovitch. Aaron’s ‘celtar’ style (which combines cello and guitar technique) has entered both the popular and classical musical worlds. He had a broad musical education, studying with Harvey Shapiro and Channing Robbins of Juilliard, Jonathan Miller of the Boston Symphony, George Saslow, Einar Holm, and David Wells of Manhattan School of Music where he obtained a Master of Music degree. More at Aaron Minsky’s website.

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the United States by Peters Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of Aaron Minsky.

The post Composer and cellist Aaron Minsky in 12 questions appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPost-Hay Festival bluesBehind-the-scenes tour of film musical historySongs of the Alaskan Inuit

Related StoriesPost-Hay Festival bluesBehind-the-scenes tour of film musical historySongs of the Alaskan Inuit

June 16, 2014

A thought on poets, death, and Clive James. And heroism.

Whatever else we think of poets, we don’t tend to see them as heroes.

There are exceptions, of course – Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon famously won the Military Cross, and some three hundred years earlier, Sir Philip Sidney was praised for his dash and gallantry at the Battle of Zutphen; then there’s Keith Douglas from World War II, one of the few deserters ever to abandon his post to get into a battle, who was killed shortly after the D-Day invasion.

There are exceptions, of course – Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon famously won the Military Cross, and some three hundred years earlier, Sir Philip Sidney was praised for his dash and gallantry at the Battle of Zutphen; then there’s Keith Douglas from World War II, one of the few deserters ever to abandon his post to get into a battle, who was killed shortly after the D-Day invasion.

It’s not a long list, and those on it performed their acts of heroism in, so to speak, their time off. They were heroes who happened to be poets as well. Poetry, by and large, is a solitary craft: it’s not easy to perform acts of derring-do when you’re hunched on your own over a desk. The greatest battle most poets fight is the unequal struggle against a blank sheet of paper.

But there’s another sort of heroism that poets can achieve, in honour of their talent and their craft – the courage to stare death in the face, and to keep on writing, honestly and truthfully.

Vernon Scannell managed it. After months of illness, shuffling from room to room and from oxygen cylinder to oxygen cylinder, he gave up and took to his bed — often, in the sick and ailing, a sure sign that death is approaching. Instead, he started writing again, and produced Last Post, maybe the best volume of his life:

“There’s something valedictory in the way

My books gaze down on me from where they stand

In disciplined disorder and display

The same goodwill that wellwishers on land

Convey to troops who sail away to where

Great danger waits …”

A couple of months later, he was dead.

And now there’s Clive James. Poems like Sentenced to Life and Holding Court chart James’s progress towards what he calls “dropping off the twig” with clear-eyed courage. There’s sadness and regret, but not a shred of self-pity. Approaching death, he seems to say, brings its compensations:

“Once, I would not have noticed; nor have known

The name for Japanese anemones,

So pale, so frail. But now I catch the tone

Of leaves. No birds can touch down in the trees

Without my seeing them. I count the bees.”

The Daily Mirror, never far from the front of the pack in the race to find a crass and clumsy phrase, quotes James (inaccurately, as far as I can see) as saying that he has “lost his battle with cancer”. Not so.

We all, as one of Shakespeare’s less well known characters points out, owe God a death, and getting better from cancer can only ever put off the final reckoning. But facing it down, as Scannell did and as James is doing – sending back poems like dispatches from the last frontier any of us will ever cross – is the only battle we can win. Catching the tone of leaves as the world closes in is what a real poet does, and if it’s not heroism, then I don’t know what is.

This article originally appeared on andrewtaylor.uk.net.

Andrew Taylor is the author of ten books, including Walking Wounded: The Life and Poetry of Vernon Scanell, biographies of the Arabian traveller Charles Doughty and the 16th Century cartographer Gerard Mercator, as well as books on language, literature, poetry and, history. He studied English Literature at Oxford University and worked as a Fleet Street and BBC television journalist in London and the Middle East before returning to Britain in the 1990s to concentrate on his writing career.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Selective focus on gold pen over hand written letter. Focus on tip of pen nib. © AmbientIdeas via iStockphoto.

The post A thought on poets, death, and Clive James. And heroism. appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe decline of evangelical politicsMartyrdom and terrorism: a Q&AThe appeal of primitivism in British Georgia

Related StoriesThe decline of evangelical politicsMartyrdom and terrorism: a Q&AThe appeal of primitivism in British Georgia

Racial diversity and government funding of nonprofit human services

Does the government fund nonprofit human service organizations that serve and locate in the neighborhoods with the greatest needs? This is an important question, as much of the safety net now takes the form of human services delivered, for the most part, by nonprofit organizations. Access to government benefits therefore relies increasingly on the location of nonprofits that are awarded government funds to provide human services. While conventional wisdom holds that the partnership between government and the nonprofit sector does direct government benefits to poor areas, recent research finds an opposite effect in poor neighborhoods that are substantially African American.

The prevailing model of government-nonprofit relations argues that privatization of human services is a “win-win” partnership, because nonprofits need government support if they are to survive in resource-poor neighborhoods, and government fulfills its mandate to serve poor people by funding these organizations. Indeed, research shows heavy dependence on government funding among nonprofit human service organizations that serve poor populations and locate in poor neighborhoods.

Yet, this research does not take into consideration the influence of race on the distribution of government benefits. A recent study using data from a probability sample of nonprofit human service organizations in Los Angeles County examined the likelihood that organizations received government funding. It found that greater levels of neighborhood poverty improved the chances that nonprofit human services located in them received government funding — unless those neighborhoods were substantially African American.

As shown in the graph below, the analysis compared neighborhoods with small shares of African Americans to neighborhoods in which the share of African Americans exceeded 20 percent of all residents — the “tipping point” at which whites tend to view the neighborhood as being “too African American” and avoid it. In neighborhoods that are less than or equal to 20 percent African American, the likelihood that the organization will receive government support increases along with rising poverty, consistent with the partnership model of government-nonprofit relations. In neighborhoods that exceed 20 percent African American, however, the relationship between neighborhood poverty and government funding reverses. As neighborhood poverty increases, the likelihood that nonprofit human service organizations receive government funding decreases.

Interaction between percent living in poverty and percent African American residents in location

The analysis also examined the relationship between the poverty rate and receipt of government funding for organizations in census tracts with different percentages of Latina/os, another minority group in Los Angeles County that experiences high levels of poverty. As shown in the figure below, higher neighborhood poverty seems to encourage government to fund local nonprofit human services regardless of the percentage of Latina/os in the neighborhood.

Interaction between percent living in poverty and percent Latina/o residents in location

What accounts for the failure of the partnership model in poor African American neighborhoods? First, and consistent with research that demonstrates a pattern of systematic government disinvestment in programs for vulnerable minority populations, the findings suggest that the allocation of government funding to nonprofits is subject to discriminatory forces. It could be that policymakers and public officials are reluctant to channel funding to neighborhoods that are negatively constructed and widely viewed as undeserving of government largesse, and direct limited funding to neighborhoods that are viewed as more deserving. It could also be that supposedly “color-blind” grant and contract programs that rely on competition tend to shut out historically oppressed minority neighborhoods that lack competitive advantages.

Yet, this does not explain why government is relatively responsive to poor neighborhoods with a high percentage of Latina/os. After all, Latina/os, like African Americans, are subject to discrimination in the American stratification system. The difference may lie in the relative electoral power of blacks and Latina/os in Los Angeles County. Political representation should influence allocation decisions, because groups with political power cannot be ignored even if they are negatively constructed. In Los Angeles County, African Americans represent a small percentage of the electorate — about 8 percent in 2010 — and their numbers have been shrinking in recent decades. By comparison, the percentage of Latina/os in the county, which stood at about 48 percent in 2010, is relatively large and increasing. Given their diminished electoral clout, poor African American neighborhoods may be more disadvantaged than poor Latina/o neighborhoods when it comes to attracting government funds.

The findings are particularly disturbing given that African American are more likely than other minority groups to live in neighborhoods that are both poor and highly segregated from whites. Indeed, the racial dynamics uncovered in this study suggests that the privatized welfare state may underserve neighborhoods where the need is greatest.

Eve E. Garrow is Assistant Professor of Social Work at the University of Michigan. Her research focuses on the implications of privatization of human services for poor and marginalized groups, especially racial minorities, and the commercialization of human services. She has published and presented works on government funding of human services, the role of nonprofit advocacy in promoting social rights, and the risk of client exploitation in nonprofit social enterprises that use clients as labor. Her most recent article, “Does Race Matter in Government Funding of Nonprofit Human Service Organizations? The Interaction of Neighborhood Poverty and Race,” was published in the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory.

The Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory serves as a bridge between public administration and public management scholarship on the one hand and public policy studies on the other. Its multidisciplinary aim is to advance the organizational, administrative, and policy sciences as they apply to government and governance. The journal is committed to diverse and rigorous scholarship and serves as an outlet for the best conceptual and theory-based empirical work in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Racial diversity and government funding of nonprofit human services appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPuzzling about political leadershipEight facts about the gun debate in the United StatesPolitics and cities: looking at the roots of suburban sprawl

Related StoriesPuzzling about political leadershipEight facts about the gun debate in the United StatesPolitics and cities: looking at the roots of suburban sprawl

Psychodrama, cinema, and Indonesia’s untold genocide

Film is a powerful tool for teaching international criminal law and increasing public awareness and sensitivity about the underlying crimes. Roberta Seret, President and Founder of the NGO at the United Nations, International Cinema Education, has identified four films relevant to the broader purposes and values of international criminal justice and over the coming weeks she will write a short piece explaining the connections as part of a mini-series. This is the first one.

By Roberta Seret

American director, Joshua Oppenheimer, has merged theatre, psychology, and film in his innovative documentary, The Act of Killing, Jagal in Indonesian, meaning Butcher. (BAFTA Award for Best Documentary of 2013.)

We are taken to Indonesia 1965 when more than 500,000 citizens and thousands of Chinese residents were massacred because they were communists or communist sympathizers or born Chinese.

By 1965, there were 3 million communists in Indonesia and they had the strongest communist party outside the Soviet Union and China. During this time, the political and economic situation throughout the Archipelago was unstable with an annual inflation of 600% and impoverished living conditions. General Soeharto overthrew Soekarno, took control of the army and government, and led a ruthless anti-communist purge.

For eight years (2003-2011), director Joshua Oppenheimer, lived in Indonesia, learned the language, and set himself to expose in cinema this untold genocide.

The Act of Killing recreates scenes of mass execution in Indonesia from 1965-66. The main actor, Anwar Congo, and his auxiliary protagonist, Adi Zulkadry, are perpetrators from the past who re-enact their crimes. In reality, during 1965, they were both gangsters who were promoted from selling black market movies to leading death squads in North Sumatra. Anwar, before the camera, boasts that he killed approximately 1,000 people by strangling them with wire. “Less blood that way. Less smell,” he reminisces with a smile.

The initial question for the director is what structure to choose for his documentary? How to recreate this history 47 years later on the screen to viewers who will learn about these horrors for the first time?

Oppenheimer has been influenced by Luigi Pirandello’s structure as found in the play, Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921). Pirandello’s theatre of a play within a play merges drama and psychology (psychodrama/ group therapy). And Oppenheimer, a true master, takes this form to cinema. He becomes the leader, director of the action, and asks questions to his actors so they can re-enact the history. In turn, the actors use props and improvisation to respond. Scenes unfold in unpredictable ways and the actors, without realizing it, are taken back to the past. This structure of psychodrama is the director’s secret vehicle to open up the subconscious of his characters and free their suppressed memory.

For Oppenheimer, as for Pirandello almost 100 years before, it is Art that becomes a conduit for Truth. It is Art that reveals the Reality between the Self and the outside world. Oppenheimer has achieved this on a stage while filming his actors. He uses Pirandello’s role playing and re-experiencing to expose the truth to the actors and to the world about Indonesia’s horrific genocide and impunity for such crimes.

After Anwar and his co-actors voyage deep into their past, we see them as they see themselves – criminals with blood on their hands, monsters overwhelmed with fear that the ghosts of the past will curse them.

At the end of the journey, Anwar becomes victim. The act of filming the act of killing has made him realize the 1,000 deaths he had committed. The line between acting and reality becomes blurred and there is only one Truth that emerges.

Anwar’s last scene is his response to this intense journey. He gives us a guilt-ridden soliloquy reminiscent of Shakespeare and a scene of vomiting where he tries to purge himself of his victims’ blood. Oppenheimer does not rush this scene. He lets the power of film take over as the camera documents for history the criminal’s realization that he is a Butcher of Humanity.

Roberta Seret is the President and Founder of International Cinema Education, an NGO based at the United Nations. Roberta is the Director of Professional English at the United Nations with the United Nations Hospitality Committee where she teaches English language, literature and business to diplomats. In the Journal of International Criminal Justice, Roberta has written a longer ‘roadmap’ to Margarethe von Trotta’s film on Hannah Arendt. To learn more about this new subsection for reviewers or literature, film, art projects or installations, read her extension at the end of this editorial.

The Journal of International Criminal Justice aims to promote a profound collective reflection on the new problems facing international law. Established by a group of distinguished criminal lawyers and international lawyers, the journal addresses the major problems of justice from the angle of law, jurisprudence, criminology, penal philosophy, and the history of international judicial institutions.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Psychodrama, cinema, and Indonesia’s untold genocide appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow much do you know about the Law of the Sea?We’re all data nowRussia’s ‘spring’ of 2014

Related StoriesHow much do you know about the Law of the Sea?We’re all data nowRussia’s ‘spring’ of 2014

The appeal of primitivism in British Georgia

The ideal of primitivism was common feature in eighteenth-century British society whether in architecture, art, economics, landscape gardening, literature, music, or religion. Nicholas Hawksmoor’s six London neo-classical churches are one example of the primivitist ideal in architecture and religion.

Primitivism featured prominently in the plans the Georgia Trustees in the founding of the last of the thirten American colonies in 1732. The Trustees, who governed Georgia for its first twenty years, chose the motto Non sibi sed aliis (Not for self, but for others) for their official seal. This in itself was an indication of their attraction to primitivism as the Latin phrase was derived from the closing words of St Augustine’s De Doctrina Christiana (On Christian Doctrine).

The motto also helped the Trustees to express the philanthropic intention at the heart of their establishment of Georgia. This slogan interpreted within the context of the eighteenth-century economic debates on trade and luxury, illustrates the Trustees’ appeal to a traditional classical notion of virtue. And it was in their economic ideals for the new colony that the Trustees’ appeal to primitivism can be seen most clearly.

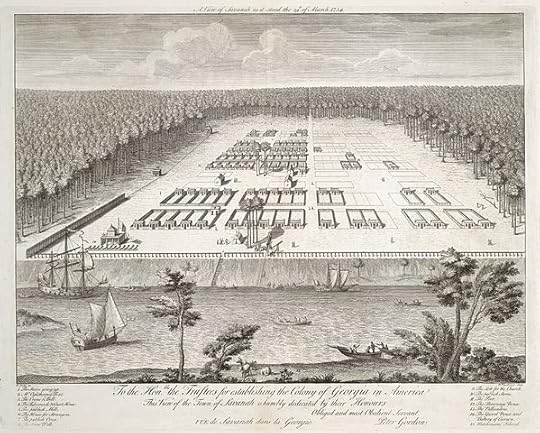

A view of Savannah as it stood the 29th of March 1734. By Pierre Fourdrinier and James Oglethorpe. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The ideal of disinterested charity was enshrined in the colony’s charter which prevented the Trustees “and their Successors from receiving any Salary, Fee, Perquisite, or Profit whatsoever by or from this undertaking.” The Trustees’ philosophy of disinterested charity was intimately bound up with their overarching ideal of economic primitivism. Much of the promotional literature for the Georgia colony appealed to the primitivist ideal widely espoused in eighteenth-century Britain, especially by Tory opposition to the Walpole government. The opposition polemic advocated a return to a mythical age when all people worked together primarily for the good of the community rather than for their own prosperity.

The Georgia colony was designed to avoid the twin dangers of luxury and idleness through a return to primitive community based economic life. For the Trustees, this was exemplified by the proper balance between moral and economic development achieved in ancient Rome. Though in obvious conflict with the reality of life in ancient Rome, the Trustees prohibited rum, slavery, and large landholdings with the aim of restoring ancient virtue. They believed that proper social restraints needed to be in place in order to militate against vice and encourage civic responsibility. By critiquing British luxury, the Georgia colony was intended to be an example of a more pure and primitive form of community oriented economic life.

This was all undergirded by a clear religious motive. For the Trustees, economic primitivism, as a means of imitating Christ, was conceived of as an expression of their Christian faith. Their desire was for Georgia to be a religious utopia modelled on the ideal of reviving a lost age of primitive Christian virtue. Toward this aspiration they sought divine blessing on their endeavours by implementing notions of economic biblical communitarianism. They also consciously modelled the town plan of Savannah on biblical and classical patterns.

Was the Trustees’ vision achievable? Was it doomed to fail when brought into contact with the realities of a colony in an undeveloped primitive wilderness? While often sympathizing with the Trustees’ ideals, many historians of colonial Georgia have answered the latter question in the affirmative. For example, the Trustees’ determination to manage social life in Georgia combined with their distrust of the colonists’ ability to govern themselves led to weak and often ineffective social structures such as the dysfunctional court which habitually became a centre of conflict when de facto governor James Oglethorpe was absent from the colony.

The Trustees’ idealistic policies, in part, led a loose group they labelled ‘malcontents’ to advocate for the reversal of the banns on rum, slavery, and large landholdings which were central to the Trustees’ hopes of moulding Georgia into a primitive utopia. In A True and Historical Narrative of the Colony of Georgia in America (1741) discontented colonists mocked the Trustees for giving them “the opportunity of arriving at the integrity of the Primitive Times, by entailing a more than Primitive Poverty on us … As we have no Properties to feed Vain-Glory and beget Contention.” Over time the Trustees grudgingly gave up on their prohibitions of rum, slavery, and large landholdings.

John Wesley (1703-1791). Public domain via Library of Congress

In the midst of the conflict between the Trustees’ lofty ideals and the realities of life in early Georgia, John Wesley, the co-founder of Methodism, arrived in the colony in 1736. Wesley himself was a primitivist of a slightly different order than the Trustees. Having spent much of the last fifteen years in the academic surroundings of Oxford, Wesley arrived in Georgia with a burning passion to restore the doctrine, discipline, and practice of the primitive church in the primitive Georgia wilderness.While his motivation was primarily religious, and was driven by a High Church Anglican ideal, he sympathized with the Trustees’ economic primitivism. The authors of A True and Historical Narrative claimed that he “frequently declared, that he never desired to see Georgia a Rich, but a Religious Colony.” Ironically, however, in the minds of some Trustees, Wesley became a ‘malcontent’ who undermined their authority by becoming an advocate for poor colonists whom he believed were being oppressed by the magistrates and court in Savannah.

The early years of colonial Georgia provide a fascinating case study to observe attempts to apply the eighteenth-century British cultural phenomenon of primitivism in a primitive environment.

Geordan Hammond is Senior Lecturer in Church History and Wesley Studies at the Nazarene Theological College, Manchester, UK. He is the author of John Wesley in America: Restoring Primitive Christianity. He is co-organizer of the June 2014 ‘George Whitefield at 300′ conference. He serves as co-editor of the journal Wesley and Methodist Studies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The appeal of primitivism in British Georgia appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe decline of evangelical politicsEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800Martyrdom and terrorism: a Q&A

Related StoriesThe decline of evangelical politicsEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800Martyrdom and terrorism: a Q&A

June 15, 2014

The decline of evangelical politics

Has the evangelical era of American politics run its course? Two terms into the Obama administration, and nearly four decades since George Gallup Jr. declared 1976 the “Year of the Evangelical,” it is tempting to say yes.

During the run-up to the 2008 election, Barack Obama went out of his way to court moderate and progressive evangelicals, such as Jim Wallis of Sojourners. Yet their role in his administration has not been remotely comparable to that of the Christian Right just ten years ago. Joshua DuBois and Melissa Rogers (respectively the previous and present heads of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships) are hardly talk show fodder in the manner of the Bush administration evangelical lightning rods John Ashcroft and Monica Goodling.

The Bush years sparked books like Chris Hedges’s American Fascists. The Obama years tend to inspire pieces with titles like “The Changing Face of Christian Politics.” The point, made by former Obama administration official Michael Wear, is that Christian politics has a new lease on life.

President Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan with Billy Graham, 1981. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

This new life comes at the expense of evangelical relevance, however. Evangelical political capital is quite scattered — useful for building fresh coalitions on immigration, while still holding the line on abortion. This configuration happens to resemble the world-view of Pope Francis. He is in the news a lot more than evangelist Franklin Graham, the son of Billy Graham.

Such is the view from on high, at least. In many statehouses, evangelical influence is alive and well. Even in red-state America, though, we see a defensive posture that spells retreat, if not outright defeat.

In a proliferating number of legislative initiatives, gay civil rights is cast as a threat to religious liberty. Rather than protesting excessive church-state separation, these efforts embrace an expansive interpretation of religious free exercise.

The contention, while not novel, is telling: conscience trumps open access. Here, conscience applies to commercial property, as in the case of caterers that refuse to serve gay weddings (as opposed to not inviting a couple over for Sunday dinner). This radical view of property rights does Kentucky Senator Rand Paul proud, even though he is often touted as the libertarian antidote to evangelical hegemony in the GOP.

At first glance, the religious liberty angle looks like a savvy strategy. After all, active Christians (including many Catholics and other non-evangelicals) far outnumber avowed secularists. But it is something of a leap of faith to believe that millions of Christian voters will prioritize religious liberty over, say, health care or education.

Thanks to former Christian Coalition head Ralph Reed, religious freedom was a clarion rallying cry during the 2012 campaign. Yet it has always been a supplementary theme within the Christian Right. Back in the 1990s, Reed made waves by proclaiming that Christians should not be relegated to the “back of the bus.” Reed’s use of a Civil Rights Movement analogy (a habit that continues) turned critical attention away from his more important goal: electing social conservatives to office.

Another form of social conservative defense involves appeals to social science data. Several well-funded studies — most notoriously, one by University of Texas sociologist Mark Regnerus — are cited to suggest that children raised in heterosexual households fare better than those raised by gay parents.

Unsurprisingly, the research has sparked controversy. Touting the superiority of straight marriage for the purpose of keeping the playing field uneven seems the height of tautology. One can plausibly hypothesize that legalized gay marriage will lead to stronger same-sex households. Besides, in what universe are heterosexual households suddenly renowned for their stability?

Such strategic flailing does not mean that the Christian Right is over—far from it. Yet, as these defensive messages indicate, it has abandoned the pretense of being a moral majority. This is no small shift in a winner-takes-all democracy.

Social conservatives (evangelical or otherwise) are no longer only battling liberal elites. They are contending with a growing real majority of Americans who either vigorously disagree with them or do not see what the fuss is all about. These Americans have long separated their workplaces from their places of worship. They likewise assume the separation of church and health care (notwithstanding the names of their neighborhood hospitals). Some of them support increased access to contraception precisely because they are uncomfortable with abortion.

Many evangelicals affirm these common-sense approaches, of course. The Christian Right does not represent them; in most cases, it never did. Now, though, evangelical conservatives are having a harder time getting away with claiming to speak for all evangelicals, never mind for Christians as a whole.

We are witnessing the public de-coupling of “evangelical” from “Christian” when it comes to politics. Born-again Christianity is no longer the standard against which religion’s role in public life is measured. This is a pivot from forty years of Carter, Falwell, Robertson, and Dobson, and it seems unlikely to be reversed anytime soon.

Steven P. Miller, Ph.D., is the author of The Age of Evangelicalism: America’s Born-Again Years, which is published by Oxford University Press USA this month. His first book, Billy Graham and the Rise of the Republican South, appeared in 2009. Miller lives in St. Louis, where he teaches History at Webster University and Washington University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The decline of evangelical politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMartyrdom and terrorism: a Q&AEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800Derrida on the madness of our time

Related StoriesMartyrdom and terrorism: a Q&AEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800Derrida on the madness of our time

Puzzling about political leadership

Since Machiavelli, political leadership has been seen as the exercise of practical wisdom. We can gain insights through direct personal experience and sustained reflection. The core intangibles of leadership — empathy, intuition, creativity, courage, morality, judgement — are largely beyond the grasp of ‘scientific’ inquiry. Understanding leadership comes from living it: being led, living with and advising leaders, doing one’s own leading.

In sharp contrast, a ‘science of leadership’ has sprung up in the latter half of the twentieth century. Thousands of academics now make a living treating leadership as they would any other topic in the social sciences, and political leadership is no exception. These scholars treat it as an object of study, which can be picked apart and put together. Their papers fill journals, handbooks, conference programs, and lecture theatres. Some work in the real world of political leadership as consultants and advisers, often well paid. This buzzing, blooming confusion would not persist if such knowledge did not help in grasping at least some of the puzzles that leaders face and leadership poses. And there are puzzles aplenty.

The first puzzle is whether we are looking at the people we call leaders, or at the process we call leadership? Leader-centred analysis has proved hugely popular but many now prefer to understand political leadership as a two-way street; an interaction between leaders and followers, leaders and media, leaders and mass publics.

The second puzzle is whether we are studying democrats or dictators. Democracy needs good leadership yet the idea of leadership potentially conflicts with democracy’s egalitarian ethos. Political leaders holding office in democratic societies live in a complex moral universe. Other heads of government gained power by undemocratic means. They sometimes govern by fear, intimidation, and blackmail. Is that leadership? However, even such ‘leaders’ may aim for widely shared and morally acceptable goals and rule with the tacit consent of most of the population. Understanding leadership requires us to take in all its shades of grey: leading and following, heroes and villains, the capable and the inept, winners and losers.

The third puzzle ponders whether political leadership matters. Leaders use their political platforms to inject words, ideas, ambitions and emotions into the public arena, to shape public policies and transform communities and countries. But when do they make a difference? What stops them from being a force in society? Or are political leaders a product of their societies? Finding out who gets to lead can teach us much, not just about those leaders, but about the societies in which they work. So, we ask who becomes a political leader, how and why? What explains their rise and fall?

The fourth puzzle explores the relative importance of their personal characteristics and behaviour compared to the context in which they work. Sometimes political leaders are frail humans afloat on a sea of storms and sometimes they survive at the helm when few thought that possible. They achieve policy reforms and social changes against the odds, and the inherited wisdom perishes. How do political leaders escape the dead hand of history?

The fifth puzzle wonders if the success of leaders stems from their special qualities or traits – the so-called ‘great man’ theory of leadership. However, we have to entertain the possibility that these allegedly ‘great’ leaders might have been just plain lucky; that is they get what they want without trying. They are ‘systematically lucky’.

The sixth puzzle is about success and failure. How do we know when a political leader has been successful? The temptation is always to credit their success to their special qualities, but no public leader ever worked alone. Behind every ‘great’ leader are indispensable collaborators, advisers, mentors, and coalitions; the building blocks of the leader’s achievements.

Political leadership is both art and profession. Political leaders gain office promising to solve problems but more often than not they are defeated by our puzzles. There is no unified theory of leadership to guide them. There are too many definitions, and too many theories in too many disciplines. We do not agree on what leadership is, or how to study it, or even why we study it. The subject is not just beset by dichotomies; it is also multifaceted, and essentially contested. Leaders are beset by contingency and complexity, which is why so many leaders’ careers end in disappointment.

R. A. W. Rhodes and Paul ‘t Hart are the editors of The Oxford Handbook of Political Leadership. R. A. W. Rhodes is Professor of Government at both the University of Southampton (UK); and Griffith University (Brisbane, Australia). He is the author or editor of some 35 books including recently Lessons of Governing. A Profile of Prime Ministers’ Chiefs of Staff (with Anne Tiernan, Melbourne University Press 2014); and Everyday Life in British Government (Oxford University Press 2011). Paul ‘t Hart is Professor of Public Administration at the Utrecht School of Governance; associate Dean at The Netherlands School of Government in The Hague; and a core faculty member at the Australia New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). He is the author or editor of some 35 books including recently Understanding Public Leadership (Palgrave Macmillan 2014); and Prime Ministerial Leadership: Power, Parties and Performance (co-edited with James Walter and Paul Strangio (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Woodcut from the title page of a 1499 pamphlet published by Markus Ayrer in Nuremberg. It depicts Vlad III “the Impaler” dining among the impaled corpses of his victims. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Puzzling about political leadership appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEight facts about the gun debate in the United StatesMay 2014: a ‘political earthquake’?Martyrdom and terrorism: a Q&A

Related StoriesEight facts about the gun debate in the United StatesMay 2014: a ‘political earthquake’?Martyrdom and terrorism: a Q&A

When is a book a tree?

The obvious answer to ‘when is a book a tree?’ is ‘before it’s been made into a book’ – it doesn’t take a scientist to know that (most) paper comes from trees – but things get more complex when we turn our attention to etymology.

The word book itself has changed very little over the centuries. In Old English it had the form bōc, and it is of Germanic origin, related to for example Dutch boek, German Buch, or Gothic bōka. The meaning has remained fairly steady too: in Old English a bōc was a volume consisting of a series of written and/or illustrated pages bound together for ease of reading, or the text that was written in such a volume, or a blank notebook, or sometimes another sort of written document, such as a charter.

By Bruce Marlin. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The argument for…

The pages of books in Anglo-Saxon times were made out of parchment (i.e. animal skin), not paper. But nonetheless a long-standing and still widely accepted etymology assumes that the Germanic base of book is related ultimately to the name of the beech tree. Explanations of the semantic connection have varied considerably. At one point, scholars generally focused on the practice of scratching runes (the early Germanic writing system) onto strips of wood, but more recent accounts have placed emphasis instead on the use of wooden writing tablets.

Words in other languages have followed this semantic development from ‘material for writing on’ to ‘writing, book’. One example is classical Latin liber meaning ‘book’ (which is the root of library). This is believed to have originally been a use of liber meaning ‘bark’, the bark of trees having, according to Roman tradition, been used in early times as a writing material. Compare also Sanskrit bhūrjá- (as masculine noun) ‘birch tree’, and (as feminine noun) ‘birch bark used for writing’.

The argument against…

This explanation has troubled some scholars. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, the words for ‘book’ and ‘beech’ in the earliest recorded stages of various Germanic languages belong to different stem classes (which determine how they form their endings for grammatical case and number), and the word for ‘book’ shows a stem class that is often assumed to be more archaic than that shown by the word for ‘beech’.

Secondly, in Gothic (the language of the ancient Goths, preserved in important early manuscripts) bōka in the singular (usually) means ‘letter (of the alphabet)’. In the plural, Gothic bōkōs does also mean ‘(legal) document, book’, but some have argued that this reflects a later development, modelled on ancient Greek γράμμα (gramma) ‘letter, written mark’, also in the plural γράμματα (grammata) ‘letters, literature’ (this word ultimately gives modern English grammar), and also on classical Latin littera ‘letter of the alphabet, short piece of writing’, also in the plural litterae ‘document, text, book’ (this word ultimately gives modern English literature).

In light of these factors, some have suggested that book and its Germanic relatives may show a different origin, from the same Indo-European base as Sanskrit bhāga- ‘portion, lot, possession’ and Avestan baga ‘portion, lot, luck’. The hypothesis is that a word of this origin came to be used in Germanic for a piece of wood with runes (or a single rune) inscribed on it, used to cast lots (a practice described by the ancient historian Tacitus), then for the runic characters themselves, and hence for Greek and Latin letters, and eventually for texts and books containing these.

However, many scholars remain convinced that book and beech are ultimately related, and argue that the forms and meanings shown in the earliest written documents in the various Germanic languages already reflect the results of a long process of development in word form and meaning, which has obscured the original relationship between the word book and the name of the tree. For some more detail on this, and for references to some of the main discussions of the etymology of book, see the etymology section of the entry for book in OED Online.

This article first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Philip Durkin is Deputy Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, and the author of Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English .

Language matters. At Oxford Dictionaries, we are committed to bringing you the benefit of our language expertise to help you connect with your world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post When is a book a tree? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA globalized history of “baron,” part 1Fishing in the “roiling” waters of etymologySmall triumphs of etymology: “oof”

Related StoriesA globalized history of “baron,” part 1Fishing in the “roiling” waters of etymologySmall triumphs of etymology: “oof”

June 14, 2014

Martyrdom and terrorism: a Q&A

Martyrdom and terrorism are not new ideas, and in fact have been around for thousands of years, often closely tied to religion. We sat down with Jolyon Mitchell to discuss the topic of martyrdom and how it relates to terrorism in the past and today.

How did you get into working on martyrdom and related topics?

Before moving to the University of Edinburgh, I worked as a producer and journalist with BBC World Service. While there I was part of a team who covered a number of news and human interest stories relating to martyrdom, terrorism and hostage-taking. For example, we interviewed a number of Western hostages (such as Terry Waite and Brian Keenan) soon after they were freed from several years of captivity in Lebanon. Listening to their stories led me to think further about the motivations of those who had captured and had then held them for many months. I would later investigate why some of their number would go further and resort to acts of violence or terror against Westerners, while others would be prepared to give up their lives to promote their cause. It became clear then to me that one community’s martyr can be another community’s terrorist.

What fascinates you so much about the topic of martyrdom?

In Media Violence and Christian Ethics, I investigated how different people remembered, responded to and interacted with images of violence. I became fascinated with how different audiences handled “dangerous memories,” including memories of martyrdom. This work led in turn to research trips to countries such as Rwanda and Iran. In Tehran I found myself surrounded by stories and images of martyrdom, which went back many hundreds of years. In Rwanda, I investigated sites of martyrdom from the genocide in 1994. I am also fascinated by the different ways in which martyrdom is interpreted. For some, a martyr and a martyrdom are objective empirical realities that can be studied as isolated phenomena, for others they are largely created by later communities. From both perspectives there can be many different kinds of martyrdom. Who makes a martyr and their martyrdom is a more complicated question than it at first appears. Some suicide bombers embrace death in such a way as to lay the foundations for their ends to be described as a martyrdom and themselves to be thought of as martyrs. Some actively pursued martyrdom while others, when they realized death was inevitable, became more considered in their actions, writing, or speech. Some individuals such as Charles I or Jose Rizal, the founding martyr of the modern state of the Philippines, may have lost control of their lives, but they attempted to control the way their deaths would be remembered. Others did not have the luxury or time to be able to try to influence their earthly afterlives. The way in which later communities describe and then interpret a death influences whether it is remembered as a martyrdom. This diversity of interpretations and perspectives are rich topics for analysis.

How far has militant martyrdom become increasingly secular?

There are different kinds of martyrdom and different motivations for being prepared to offer one’s life to promote a particular cause. Those who are prepared to die, and take other lives, are described by some as martyrs and by others as murderers. There is a tradition of “secular martyrs” who are motivated not by religious belief, but by political objectives. For example, the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka used suicide bombing as a way of promoting their own cause. Their deaths were celebrated by many local Tamils as seeds of freedom. Nevertheless, in other contexts such as in the Middle East some individuals are prepared to die to kill for both religious and political reasons.

Why is it so important to look at connections between martyrdom and terrorism today?

While it can be useful to make a distinction between active and passive martyrdoms, predatory and peaceful martyrdoms, military and non-violent martyrdoms, there is clearly a close connection for many between martyrdom and terrorism. In Martyrdom: A Very Short Introduction, I suggest that over the last few years martyrdom has gone digital. The digitization of martyrdom is changing the way martyrs are commemorated, remembered, and interpreted. Audiences now have direct access to countless original martyrdom stories, texts and martyrologies (lists of martyrs). Online images of martyrs are now widely accessible. A few taps on a computer or mobile phone and anyone can see the faces of those named as martyrs. They criss-cross the globe weaving unexpected patterns, leaving traces of deaths that otherwise might be forgotten. As memories of martyrdom are remembered and re-presented digitally, images of martyrs and martyrdoms can “bear witness” both to practices of violence and peace.

Your chapter in Martyrdom and Terrorism: Pre-Modern to Contemporary Perspectives is about filming the ends of martyrdom. How far is a film like Cecil B. Demille’s The Sign of the Cross (1932) only a period piece or does it still have something important to tell us?

Every film reflects the historical and cultural context out of which it was produced. Cecil B. Demille’s The Sign of the Cross is no exception. To our CGI-trained eyes, like most black and white films from the 1930s, this films looks like a window onto a foreign land. The dialogue, the shots, and the narrative all seem peculiar or certainly idiosyncratic. Nevertheless, this film, like several other films touching on martyrdom, raises important questions pertinent to discussions about martyrdom today. For example, why do some people embrace death for their faiths? How do state powers attempt to control the bodies of their subjects? And what role does religious belief have in the making of martyrs?

Film still from Cecil B. DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross (1932), reproduced courtesy of Paramount and the Kobal Collection, ref. SIG001CC.

In your chapter you also mention the movie Becket, which includes another notable cinematic martyrdom. What kinds of materials have been used to preserve the story of King Henry III and the knights who killed archbishop Thomas Becket in his own cathedral in 1070?

Following the murder of Thomas à Becket (c.1118-1170) by four of King Henry II’s (1133-1189) knights in Canterbury Cathedral on 29 December 1170 his remains were buried at the eastern end of the Cathedral’s crypt. Concerned that his body might be stolen, the monks ensured that the burial was carried out swiftly, with a stone placed over his tomb. At least one hole was cut through the stone so that pilgrims would be able to kiss the place where Becket was buried. Becket was canonised in 1173 by Pope Alexander III (c.1100-1181), just three years after his murder. Thousands of pilgrims were soon visiting the shrine of the former Archbishop of Canterbury. Here was a Northern European Norman saint whose remains became a magnet for visitors. The significant increase in the number of visiting pilgrims substantially augmented the wealth of the Cathedral and the city of Canterbury. When alive, Becket’s manner as Archbishop had won him few friends, but when dead he was venerated as a saint and a martyr. As such he could pray for the living, so becoming a focal point for generous giving. Pilgrims, for example, were able to purchase Becket badges or tokens marking their pilgrimage. By 1220, his bones were transferred into a jewelled golden shrine on a raised platform in the Cathedral’s specially constructed Trinity Chapel, where offerings also increased.

Both relics and images of Becket travelled swiftly in the first few decades after his death. It was not long before stained glass, wall paintings and manuscripts were being illustrated with scenes of his life and martyrdom. The V&A’s director in London, Alan Borg, claims that there was “a sort of Becket mania” that “spread across Europe.” Evidence suggests that within a few decades of his death, the spread of Becket’s martyr cult stretched from Iceland and Scotland to Palestine and Italy. Becket’s memory touched many people’s lives, though by the time the humanist Erasmus (c. 1466-1536) visited the shrine at Canterbury in the early sixteenth century he was bemused at the wealth and showmanship of one of his guides introducing him to the relics. The story of Beckett would later become the subject of plays (notably T.S. Elliot’s “Murder in the Cathedral”) and films. In this way the story of Beckett’s martyrdom has been amplified, elaborated and translated into new materials.

Dominic Janes, Alex Houen, and Jolyon Mitchell are the co-editors of Martyrdom and Terrorism: Pre-Modern to Contemporary Perspectives. Dominic Janes is Reader in Cultural History and Visual Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. In addition to a spell as a lecturer at Lancaster University, he has been a research fellow at London and Cambridge universities. His latest book project is Queer Martyrdom from John Henry Newman to Derek Jarman. Alex Houen is Senior University Lecturer in Modern Literature in the Faculty of English, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of Pembroke College. He is author of Terrorism and Modern Literature, as well as various articles and book chapters on literature and political violence. Jolyon Mitchell is Professor Communications, Arts and Religion at University of Edinburgh .

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Martyrdom and terrorism: a Q&A appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBehind-the-scenes tour of film musical historyEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800Derrida on the madness of our time

Related StoriesBehind-the-scenes tour of film musical historyEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800Derrida on the madness of our time

English convent lives in exile, 1540-1800

In the two and a half centuries following the dissolution of the monasteries in England in the 1530s, women who wanted to become nuns first needed to become exiles. The practice of Catholicism in England was illegal, as was undertaking exile for the sake of religious freedom.

Despite the heavy penalties and risks, nearly 4,000 women joined monastic communities in continental Europe and North America between the years 1540 and 1800, known as the exile period. Until recently, their stories had been virtually unknown — absent from studies of literature, history, art history, music, and theology. But thanks to the recent work of scholars such as Caroline Bowden of the Who were the nuns? project, and its resulting publications, the English nuns in exile are now gaining scholarly attention, individually, as founders, leaders, and chroniclers, and collectively as members of a transnational religious community.

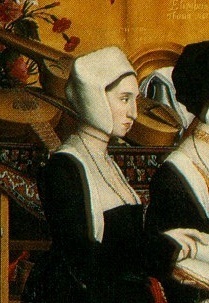

Margaret Clement, 16th century, Nostell Priory, Nr. Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The majority of nuns in the exile period professed (that is, took their vows to enter a religious order) at convents that were founded expressly for English and Irish women. However, in the early decades of exile — in the mid to later-sixteenth century — women such as Margaret Clement (1539-1612), joined established continental houses. Clement, a descendant of Sir Thomas More, rose to prominence at the Flemish Augustinian convent of St. Ursula’s in Louvain, and was elected prioress at the age of thirty, despite being ten years too young to hold the post, and being one of only two English women in that community. She was fluent in Greek, Latin, English, and Flemish, and was renowned for her spiritual guidance and strict regulation at the convent.

The educational accomplishments of Margaret Clement are remarkable, but by no means unique. The majority of “choir nuns” — those responsible for singing the Latin office each day — were required to be Latinate: not merely to be able to sing the words, but to understand them. We find copious examples of well-read women who employed their time translating and composing original devotional works, governance documents, chronicles, and letters. Take, for example, Barbara Constable (1617-1684), the translator and author of spiritual guidance manuals written for nuns, monks, priests, and lay people. From her exile in Cambrai, Constable aspired through her writing to re-establish a sense of Catholic heritage and identity that the Reformation had suppressed. Others include Winefrid Thimelby (1618/19-1690), whose letters — written first as a choir nun at St. Monica’s, Louvain, and later as its prioress — offer insights on religious practice and convent management; and Joanne Berkeley (1555/6-1616), the first abbess of the Convent of the Assumption of Our Blessed Lady, Brussels, whose house statutes were used well into the nineteenth century. The learning and accomplishments of these women overturns long-held assumptions by scholars that Catholics were not as well read as their Protestant peers.

Nuns’ surviving literature reveals the difficulties and dangers of exile. Elizabeth Sander (d.1607), a Bridgettine nun and writer of the community of Syon Abbey, was imprisoned at Bridewell in Winchester in 1580 while on a return journey to England. Her crime: possession of Catholic books. Sander escaped several times, once by means of a “rope over the castle wall,” but returned to prison upon the advice of priests who urged her to obey English law. She escaped again, and travelled under a pseudonym to the continent, where she rejoined her community at Rouen, and later wrote about her experience of imprisonment and flight.

Nuns throughout the exile period faced similar perils to those narrated by Sander. The Catholic convert, Catherine Holland (1637-1720), defied her Protestant father and ran away from the family home in England in 1662, in order to join a convent in Bruges where she penned her lively autobiographical conversion narrative. Other nuns, such as the Carmelite Frances Dickinson (1755-1830), travelled to North America to establish new communities, in Dickinson’s case the Port Tobacco Carmel, Maryland. Dickinson’s narrative of her transatlantic journey, undertaken in 1790, is one of the few extant accounts of its kind written by a woman in the eighteenth century.

Mt Carmel Monestery and Chapel, Port Tobacco, Maryland, by Pubdog. Public domain from Wikimedia Commons.

Once within their convents, life was often no less exciting for exiled nuns. These were years of political and military turmoil in much of continental Europe. Women religious frequently endured sieges, famine, plagues, and floods, and were sometimes forced to move on in the aftermath of religio-political violence, as in the case of the Irish Poor Clare abbess, Mary Browne (d.1694?), who professed in Rough Lee, before relocating to Galway in 1642 during the English Civil War and then to Madrid after 1653, the year the convent at Galway was dissolved by Cromwell’s forces. Browne’s history of the Poor Clare order offers a lively account of these events and is now the sole surviving chronicle of its kind relating to early modern Ireland.

Convents could also serve as safe-houses or stopping off points for English exiles on the continent. These included not just the friends and family of the nuns, but kings and their courts — including the future Charles II in the 1650s and the Jacobite king-in-waiting, James III — who relied on the generosity and hospitality of several English convents to sustain their time away from Britain. Many exiles bequeathed money, gifts, and relics to the convents, including embalmed hearts, as Geoffrey Scott reveals in his biography of Anne Throckmorton (1664-1734), prioress of the Convent of Our Blessed Lady of Syon, Paris. Throckmorton’s receipt of the hearts of Jacobite “martyrs” is indicative of her support for the Stuart cause, which also saw her petition the French government for penniless political exiles.

Prayer was, of course, central to the nuns’ vocation, but convent life was multifaceted. In the wake of the Reformation, convents in exile offered many opportunities for Catholic women. They could pursue their own education, usually in languages, medicine, and religious studies, and they could also teach, by taking on the roles of novice mistress and school mistress. A notable educationist is Christina Dennett (1730-1781) who, as prioress of the Holy Sepulchre, Liège, expanded the convent’s small school with the intention of providing Catholic girls with “the same advantages which they would have in the great schools in England.” The school’s registers for 1770-94 include the names of 350 pupils from six nationalities, studying a wide range of subjects. Many of the nuns who held teaching positions went on to become financial managers, abbesses, sub-prioresses, and prioresses. In these positions they controlled budgets, built new premises, and commissioned art works. They were integral members of their local communities in continental Europe and America, and to the post-Reformation English and Irish Catholic diaspora.

Of the nearly 4,000 English women religious who went into exile from the mid-sixteenth century, many are known to us only by name. But for some, such as those described here, it is possible to write full biographies thanks to their surviving papers, contemporary accounts and obituaries, and to the notable role they played in creating, defending, managing, and expanding their communities. In several instances their legacy to convent life continues in the survival of their houses, as in the case of Frances Dickinson’s Carmel of Port Tobacco (now located in Baltimore) or the English Augustinian Convent in Bruges, where Catherine Holland professed in 1664.

Other houses, founded in exile, came to England in the mid-1790s as they sought to escape fresh persecution following the French Revolution. Among these was the Benedictine Convent of Brussels (whose first prioress Joanne Berkeley had been installed in 1599) and Our Lady of Consolation, Cambrai, where Catherine Gascoigne had served as abbess for 44 years. The latter, and its 1651-2 Paris filiation, continue today as Stanbrook Abbey, Wass, North Yorkshire and St Mary’s Abbey, Colwich, Staffordshire — as does as Christina Dennett’s convent school at Liège, which is now the New Hall School, Chelmsford.

Dr Victoria Van Hyning is Digital Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow, at Zooniverse, based at the University of Oxford. In 2013-14 she was the advisory editor for the Oxford DNB’s research project on the women religious and convents in exile, and is an assistant editor for English Convents in Exile, 1550-1800, 6 vols. (Pickering & Chatto, 2012-13).

The 20 new biographies of early modern nuns appear as part of the May 2014 update of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is a collection of 59,102 life stories of noteworthy Britons, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Oxford DNB is freely available via public libraries across the UK, and many libraries worldwide. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to gain access free, from home (or any other computer), 24 hours a day. You can also sample the ODNB with its changing selection of free content: in addition to the podcast; a topical Life of the Day, and historical people in the news via Twitter @odnb.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post English convent lives in exile, 1540-1800 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories1914-1918: the paradox of semi-modern warEighteenth-century soldiers’ slang: “Hot Stuff” and the British ArmyReflecting on the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings

Related Stories1914-1918: the paradox of semi-modern warEighteenth-century soldiers’ slang: “Hot Stuff” and the British ArmyReflecting on the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers