Oxford University Press's Blog, page 799

June 21, 2014

How much do you know about the First World War?

From Haig to Kitchener, and Vera Lynn to Wilfred Owen, how well you know the figures of the First World War? Who’s Who highlights the individuals who had an impact on the events of the Great War. Looking through Who’s Who, we are able to gain a snapshot of the talents and achievements of these individuals, and how they went on to influence history.

From Haig to Kitchener, and Vera Lynn to Wilfred Owen, how well you know the figures of the First World War? Who’s Who highlights the individuals who had an impact on the events of the Great War. Looking through Who’s Who, we are able to gain a snapshot of the talents and achievements of these individuals, and how they went on to influence history.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Who’s Who is the essential directory of the noteworthy and influential in every area of public life, published worldwide, and written by the entrants themselves. Who’s Who and Who Was Who 2014 includes autobiographical information on over 134,000 influential people from all walks of life. You can browse by people, education, and even recreation. Check out the latest feature article, which offers article content on those who shaped history between the years 1897 and 1940. For free lives of the day, follow Who’s Who on Twitter @ukwhoswho

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Field Marshal Douglas Haig. Image available via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How much do you know about the First World War? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800Eighteenth-century soldiers’ slang: “Hot Stuff” and the British Army1914-1918: the paradox of semi-modern war

Related StoriesEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800Eighteenth-century soldiers’ slang: “Hot Stuff” and the British Army1914-1918: the paradox of semi-modern war

June 20, 2014

Welcome to the OHR, Stephanie Gilmore

This summer, our editor-in-chief Kathy Nasstrom is taking a well-deserved break, and leaving the Oral History Review and related cat-herding in the hands of the extremely capable Stephanie Gilmore. As some may have read in the Oral History Association’s most recent newsletter, Stephanie is a multitalented historian who works to combat sexual assault on university campuses. With a PhD in comparative women’s history from the Ohio State University, she is the author of Groundswell: Grassroots Feminist Activism in Postwar America (Routledge, 2013), as well as many essays on sexuality and social activism. She serves as associate editor at The Feminist Wire and newsletter editor of the Committee of LGBT Historians’ biannual newsletter. She is also a member of the editorial collective at Feminist Studies.

A few weeks ago, I chatted with Stephanie about her experience with oral history, activist work and her plans for the OHR. I started with the most important and hard hitting question: “When did you first become interested in oral history?” Like many in the field, Stephanie told me she has always enjoyed listening to people talk about their lives and experience. She recalled one assignment in a undergrad women’s history course when she interviewed her own mother. While an admittedly simple approach to oral history, the experience drove home for Stephanie “that everyone has her own stories and experiences that can contribute to and complicate a larger history of a group.” This sentiment grew as Stephanie continued to work with women’s stories. She told me, “It was when I was working on my MA thesis on the Memphis chapter of NOW that I really came into the power and potential of oral histories. What I had learned about the women’s movement in its 1970s heydays was based on histories grounded in New York, Boston, and Chicago. These histories were often told as “national” histories of the US women’s movement. When I started studying feminist activism in Memphis, I discovered feminists whose lives were nothing like their counterparts in the North. The archival material was fairly rich, but only in talking to Memphis feminists about their lives and work did I actually learn how important southern identity was to them and to their activism.”

Stephanie had a similar experience working on her recently published book, Groundswell: “In Groundswell, I traced feminist activism through NOW in the 1970s and early 1980s in Memphis, Columbus, and San Francisco. Only through oral histories could I really understand how feminist activism shaped and was shaped by geographical location. For example, only in talking to Memphis feminists about their lives and work did I actually learn how important southern identity was to them and to their activism. But even more importantly, I found that archives could and would only tell me part of the histories I was looking to share and analyze. None of the people in my book are media ‘stars,’ but they were the rank-and-file movers of the women’s movement for equality and liberation. I could only find them by looking locally, and then by moving out of the archives and into people’s homes, coffeehouses, libraries, and other places I collected oral histories.”

Sophie Gilmore. © Sophie Gilmore. Do not reproduce without permission.

I learned that Stephanie uses oral history not only to study past feminists, but also to engage in her own activist work. After spending nearly a decade teaching, Stephanie became interested in issues outside the classroom — namely, how students react to and combat sexual violence in their everyday lives. At the moment, she is especially interested in understanding the gap between government and nonprofit research, which suggests approximately 1 in 5 women will experience sexual assault while at school, and Cleary Center documents, which report that little to no sexual assault occurs on university and college campuses. In order to understand the disconnect, Stephanie works with women, students of color and LGBTQ students who did not report their sexual assault experiences. She told me she did this for two reasons in particular, “On one hand, institutions can learn a great deal from these students and can start addressing the problem of underreporting sexual violence. But I also seek to elevate the voices of those who have been most marginalized in and beyond the academy. There is a tremendous amount of attention devoted to the issue of sexual violence on college campuses, and we are wise to listen to those who have been the victims of rape and other forms of sexual violence as we contemplate and enact solutions.” Stephanie also wanted to let readers know that she gives lectures and workshops on this topic. She welcomes anyone interested in learning more about her programs to contact her through her website, www.stephaniegilmorephd.com.

The more I learned about Stephanie, the clearer it became why OHA director Cliff Kuhn contacted her about the OHR position. When I asked how she felt about coming to work with the journal, she responded, “I’m delighted to think even more explicitly and historically about the connections between social movement activism and oral history as a legacy of social justice work. I owe so much of my own professional success to feminist, queer, and antiracist activism AND to oral history – and I have been able to learn and see how activism and history are intimately related. Editing a journal is a tremendous amount of work, but the opportunity to continue shaping the field of oral history as it relates to social justice activism is thrilling!”

She certainly sounded excited to join the OHR, but what exactly did she have in mind for the journal? “What’s in store? We will continue the short-form initiative that Kathy Nasstrom initiated – it is so exciting to hear from scholars, activists, and oral history practitioners about new developments, theoretical questions, and the like – things that are not quite a traditional article-length publication but relevant and important nonetheless. But we will also be taking on a couple of new ventures.”

Such as?

“The 50th anniversary of the Oral History Association is upon us, and Teresa Barnett has agreed to help facilitate a special section of the journal to commemorate; It is a good time to see where we’ve been, where we are, and where we are going. We are also calling for papers for a OHR special issue, “Listening to and Learning from LGBTQ Lives.” The immediate interest in the call suggests that we are onto a good idea here! And of course, we are always excited to see what our readers submit – so if people have ideas for short- or long-form articles, roundtables, or the like, please let me know!”

All in all readers, I think we’re in for a great time. Welcome to the team, Stephanie!

Caitlin Tyler-Richards is the editorial/media assistant at the Oral History Review. When not sharing profound witticisms at @OralHistReview, Caitlin pursues a PhD in African History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research revolves around the intersection of West African history, literature and identity construction, as well as a fledgling interest in digital humanities. Before coming to Madison, Caitlin worked for the Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown University.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow their latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Welcome to the OHR, Stephanie Gilmore appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchange, part 2‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchangeA call for oral history bloggers

Related Stories‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchange, part 2‘Storytelling’ in oral history: an exchangeA call for oral history bloggers

World Refugee Day Reading List

World Refugee Day is held every year on 20 June to recognise the resilience of forcibly displaced people across the world. For more than six decades, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has been tracking and assisting refugees worldwide. At the beginning of 2013, there numbered over 10.4 million refugees considered “of concern” to the UNHCR. A further 4.8 million refugees across the Middle East are registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).

To mark World Refugee Day 2014, we’ve compiled a short reading list about issues in international law arising from the forced displacement of persons, including definitions of refugees, asylum, and standards of protection, international refugee legislation, international human rights legislation, the roles of international organisations, and challenges arising from protracted refugee situations and climate change. Additionally, Oxford University Press has made select articles from refugee journals freely available for a limited time, including ten articles from the International Journal of Refugee Law.

Definitions

“Refugees” in The Human Rights of Non-Citizens by David Weissbrodt

Explore the legal definition of refugees and their rights under the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

Dieter Kugelmann on “Refugees” from The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

Survey several legal definitions of refugees, refugee status, and refugee rights.

The Refugee in International Law by Guy S. Goodwin-Gill and Jane McAdam

Explore three central issues of international refugee law: the definition of refugees, the concept of asylum, and the principles of protection.

The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, edited by Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Gil Loescher, Katy Long, and Nando Sigona

How did Refugee and Forced Migration Studies emerge as a global field of interest? What are the most important current and future challenges faced by practitioners working with and for forcibly displaced people?

Population fleeing their villages due to fighting between FARDC and rebel groups, Sake North Kivu, 30 April 2012. Photo by MONUSCO/Sylvain Liechti CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Refugee Legislation

The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol: A Commentary, edited by Andreas Zimmermann, Assistant editor Jonas Dörschner, and Assistant editor Felix Machts, including Part One Background: Historical Development of International Refugee Law by Claudena M. Skran

Analyze the Convention and Protocol that function as the indispensable legal basis of international refugee law. What provisions do they make for refugees?

Chapter 5 “Refugees” in International Migration Law by Vincent Chetail

Legislation relating to the movement of persons is scattered across numerous branches of international law. How does current law govern the movement of refugees, and how might legislation develop in the future?

Textbook on Immigration and Asylum Law, Sixth edition by Gina Clayton

How has the law relating to immigration and asylum evolved? And how does the asylum process operate for refugees and trafficking victims? Gina Clayton’s newly-revised volume provides clear analysis and commentary on the political, social, and historical dimensions of immigration and asylum law.

Climate Change, Forced Migration, and International Law by Jane McAdam

Climate change is forcing the migration of thousands of people. Should this kind of displacement be viewed as another facet of traditional international protection? Or is flight from habitat destruction a new challenge that requires more creative legal and policy responses?

Refugees and international human rights

“International refugee law” by Alice Edwards in D. Moeckli et al’s International Human Rights Law, Second Edition

Alice Edwards, Senior Legal Coordinator at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, examines international human rights laws relating to refugees.

Textbook on International Human Rights, Sixth Edition by Rhona Smith

Check chapter 22 “Group rights”, which focuses on four specific groups which are currently beneficiaries of dedicated human rights’ regimes: indigenous peoples, women, children, and refugees.

“Are Refugee Rights Human Rights? An Unorthodox Questioning of the Relations between Refugee Law and Human Rights Law” by Vincent Chetail in Human Rights and Immigration, edited by Ruth Rubio-Marín

While originally envisioned as two separate branches of law, refugee law and human rights law increasingly intersect as refugees are highly vulnerable and often victims of abuse. What framework can we use to ensure the best outcome for refugees?

The obligations of States and organizations

The Collective Responsibility of States to Protect Refugees by Agnès Hurwitz

What legal freedom of choice do refugees possess? Can they choose the countries that will decide their asylum claims? States have devised several arrangements to tackle the secondary movement of refugees between their countries of origin and their final destination. See the chapter ‘States’ Obligations Towards Refugees’, which assesses the limitations of current safe third country mechanisms.

Complementary Protection in International Refugee Law by Jane McAdam

What obligations do – and should – States have to forcibly displaced persons who do not meet the legal definition of ‘refugees’?

‘The European Union Qualification Directive: The Creation of a Subsidiary Protection Regime’ by Jane McAdam in Complementary Protection in International Refugee Law

How does the European Union address the rights of persons who are not legally refugees, but who still have need of some other form of international protection?

Göran Melander on ‘International Refugee Organization (IRO)’ from The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

What can the history of the IRO tell us about the development of international agencies working for refugees, and about its successor, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)?

Refugees in Africa

African Institute for Human Rights and Development (on behalf of Sierra Leonean refugees in Guinea) v Guinea, Merits, Comm no 249/2002, 36th ordinary session (23 November-7 December 2004), 20th Activity Report (January-June 2006), (2004) AHRLR 57 (ACHPR 2004), (2007) 14 IHRR 880, IHRL 2803 (ACHPR 2004), African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights [ACHPR] from ORIL

Case-study by the African Commission: was the treatment of Sierra Leonean refugees in Guinea in 2000 in violation of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights?

‘Human Security and the Protection of Refugees in Africa’ by Maria O’Sullivan in Protecting Human Security in Africa, edited by Ademola Abass

What is distinctive about refugee flows in Africa, what are the challenges arising from mass influx and ‘protracted’ refugee situations? What are the implications of new UNHCR initiatives to protect refugees?

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post World Refugee Day Reading List appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMaking World Refugee Day countMulticulturalism and international human rights lawPolitical apparatus of rape in India

Related StoriesMaking World Refugee Day countMulticulturalism and international human rights lawPolitical apparatus of rape in India

Making World Refugee Day count

There seems to be an international day for almost every issue these days, and today, 20 June, is the turn of refugees.

When the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) releases its annual statistics on refugees today, these are likely to make for gloomy reading. They will show that there are more refugees today than any previous year during the 21st century, well over 16 million. They will demonstrate how in three years Syria has become the single largest origin for refugees worldwide – around one in seven Syrians has now fled their country, including one million children.

The statistics will also show that solutions for refugees are becoming harder to achieve. Fewer refugees are able to return home. Palestinian refugees still do not have a home; there are still almost three million Afghan refugees, many of whom have been outside their country for generations. The number of refugees who are resettled to richer countries remains stable but small, while the number offered the chance to integrate permanently in host countries is dwindling.

Afghan Former Refugees at UNHCR Returnee Camp. Sari Pul, Afghanistan. UN Photo/Eric Kanalstein. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via United Nations Photo Library Flickr.

The risk of World Refugee Day, like other international days, is that it will raise awareness of these and other challenges for a few days, before the media cycle and public attention moves on. But there are at least three ways that even passing interest can make a lasting difference.

First, a global overview provides the opportunity to place national concerns in a wider context. Many people and countries fear that they are under siege; that there are more asylum seekers, fewer of whom are recognised as refugees, who pose challenges to the welfare system, education and housing, and even national security. What the statistics invariably show, however, is that the large majority of refugees worldwide are hosted by poorer countries. Iran and Pakistan have hosted over one million Afghan refugees for over 30 years; there are millions of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey. It is in these countries that refugees may have a real impact, on the environment or labour market or health services, for example, yet by and large these poorer countries and their citizens continue to extend hospitality to refugees.

Second, World Refugee Day should be the day not just to take stock of refugee numbers, but also to ask why their numbers are rising. Refugees are a symptom of failures in the international system. There is no end in sight for the current conflict in Syria. The withdrawal of most international troops from Afghanistan by the end of 2014 is likely to make the country more insecure and generate a further exodus. Persistent and recurrent conflicts in Somalia, Mali and the Democratic Republic of Congo continue to generate refugees. In all these countries poverty and inequality intersect with insecurity to drive people from their homes. Climate change is likely to exacerbate these effects.

In an effort to bring forth the latest research and make this World Refugee Day count, Oxford University Press has gathered a collection of noteworthy journal articles addressing the latest policies, trends and issues faced by refugees around the globe and made them freely available to you. Simply explore the map above for links to these free articles.

Third, World Refugee Day brings research to the fore. The statistics needs to be analysed and trends explained. The stories behind the statistics need to be explored. Why are so many asylum seekers risking their lives to travel long distances? What are the actual impacts – positive and negative – of asylum seekers and refugees? Researchers can also leverage passing media interest by providing evidence to correct misperceptions where they exist.

This is what I see as the purpose of the Journal of Refugee Studies: to publish cutting edge research on refugees; to correct public debate; to inform policy; and to maintain attention on one of the most pressing global issues of our time. Refugees deserve more than one day in the spotlight.

Dr. Khalid Koser is Deputy Director and Academic Dean at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy and Editor of the Journal of Refugee Studies. He was also recently appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his services to refugees and asylum seekers in the UK.

Journal of Refugee Studies aims to publish cutting edge research on refugees; to correct public debate; to inform policy; and to maintain attention on one of the most pressing global issues of our time. The Journal covers all categories of forcibly displaced people. Contributions that develop theoretical understandings of forced migration, or advance knowledge of concepts, policies and practice are welcomed from both academics and practitioners. Journal of Refugee Studies is a multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal, and is published in association with the Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Making World Refugee Day count appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPolitical apparatus of rape in IndiaA 2014 summer songs playlistPutting an end to war

Related StoriesPolitical apparatus of rape in IndiaA 2014 summer songs playlistPutting an end to war

The legacy of critical care

Over the last half century, critical care has made great advances towards preventing the premature deaths of many severely ill patients. The urgency, immediacy, and involved intimacy of the critical care team striving to correct acutely disturbed organ dysfunction meant that, for many years, physiological correction and ultimate patient survival alone was considered the unique measure of success. However, over the last quarter century, our survivor patients and their relatives have told us much more about what it means to have a critical illness. We work in an area of medicine where survival is a battle determined by tissue resilience, frailty, and the ability to recover, but this comes at a price. As our focus has moved beyond the immediate, we have learned about the ‘legacy of critical care’ and how having a critical illness impacts life after ICU through its consequential effects on physical and psychological function and the social landscape.

This fundamental cultural change in how we perceive critical care as a specialty and where our measure of a successful outcome includes the quality of life restored has come about through the sound medical approach of listening to our patients and families, defining the problems, and carefully testing through research hypotheses as to causation and possible therapeutic benefit. It not only has changed how patients are considered and cared for after intensive care, but, through the detailed knowledge of how patients are affected by the consequences of the critical illness, it has fostered fundamental research to improve the care and therapies we use during their stay. As with all sound clinical advances, it has helped shed light and ill-informed dogma and helped re-focus the research agenda to ensure that the long-term legacies of a critical illness are equally considered. Immobility, oft considered of little consequence, is now recognized to be a significant pathological participant and contributor to disability. Amnesia, in short-term anaesthesia considered a benefit, now has defined pathological significance, along with previously poorly recognized cognitive deficits and delusional experiences, all consequences of acute brain dysfunction. The family, often in the past merely a repository of information, is now recognized to play a much greater role in how patients recover and are themselves traumatized by the experience, so meriting help and support if they are to assist in rehabilitation.

Perhaps the purest achievement has been the bringing together of contributions not just from patients and their families, but form the wide breadth of professionals deeply involved in the care of the critically ill from across many continents. Not only have the doors of the intensive care unit been thrown open, but so too have the minds of those working for the best care of our patients. The reward of a visit some months later of a patient brought back from the brink of death is cherished by a critical care team. Added to this, the knowledge that our patients are now understanding what happened to them and they and their families are being given the help to recover their lives following the legacy of critical care is something of which our specialty should be justly proud. We cannot ignore the lessons we have learned.

Richard D. Griffiths is Emeritus Professor of Medicine (Intensive Care) and Honorary Consultant at the Institute of Aging and Chronic Disease, University of Liverpool. He is a contributor to Textbook of Post-ICU Medicine: The Legacy of Critical Care.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Doctor consults with patient by National Cancer Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The legacy of critical care appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating Trans Bodies, Trans SelvesFaith and science in the natural worldIn praise of Sir William Osler

Related StoriesCelebrating Trans Bodies, Trans SelvesFaith and science in the natural worldIn praise of Sir William Osler

What has changed in geopolitics?

By Klaus Dodds

If a week is a long time in politics then goodness knows what seven years represents in geopolitical terms. The publication of the second edition of the VSI to Geopolitics was a welcome opportunity to update and reflect on what has changed since its initial publication in 2007. Five issues loomed large for me in terms of the second edition.

First, the onset of a global financial crisis and the geopolitics of austerity deserved greater recognition. While much of the conversation focused on the failings of neoliberal globalisation and the banking/financial services sector, the financial crisis was also geographical and geopolitical in nature. Geographically, the impact and scope of crisis and austerity remains resolutely uneven with some communities and localities more exposed to debt, liability, loss and dispossession. The retrenchment of government spending and investment hit those communities highly dependent on public sector employment for example. Geopolitically, the financial crisis brought to the fore the manner in which some countries were represented and understood as financially reckless, political weak and incapable of reforming their economies. The so-called PIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain) within the European Union context might be one such example of this geopolitical profiling but another might be the manner in which Cyprus was depicted as a source of ‘hot money’ from Russia and China, which was disrupting the capacity of the Cypriot government to make ‘necessary’ fiscal and political reforms to its economy and society.

Second, the ongoing legacies of the War on Terror needed further exposition. The recent rise of Sunni Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) has generated a plethora of commentary much of which insists that the contemporary crises in Iraq and Syria are related to the deeply controversial invasion of Iraq in 2003 by a US-led coalition and a US-led strategy designed to use the invasion of Iraq as a way of introducing democratic transformation in the Middle East and Central Asia. What we now appear to face is a situation where the US and Iran might find they are able to collaborate with one another in a mutual goal of preserving the territorial integrity of Iraq (and perhaps also Syria). All of this seems far removed from the situation in January 2002 when President George W Bush described Iran as part of an ‘axis of evil’ with Iraq and North Korea. As critics noted at the time, this opportunistic labelling did not reflect the complex geopolitical circumstances surrounding those three states. And the refrain ‘states like these’ in the 2002 State of the Union Address by President Bush suggested that there might be even more to add to the list.

Third, the Edward Snowden revelations have highlighted the second edition had to talk more explicitly about an ‘invisible geopolitics’ or one perhaps barely visible to those of us not well connected to the intelligence community. While few would have been surprised by the rise of a surveillance culture post 9-11 in the US and UK (for example), it took these revelations to bring home quite how involved the communications sector was in enabling these mass surveillance cultures. Had popular culture, including films such as Enemy of the State (1998), offered us a pre-warning of the kind of surveillance capabilities that might be brought to bare on domestic citizens? What might the implications be for citizens to express geopolitical dissent in a world where telephone conversations and electronic conversation might be capable of being recorded, analysed and actioned?

Fourth, a new chapter on objects is introduced for the express purpose of focussing attention on the materiality of geopolitics. In other words, stuff. Whether it be either the CCTV camera on the high street or the flag being waved at an official ceremony, geopolitics is made possible by our relationship to objects. In the midst of the 2014 World Cup, it is difficult to avoid the sight of various national flags fluttering from buildings and cars, and being waved vigorously by supporters. In the contexts of mega events such as the Olympics and World Cups, the flag is an essential accomplice to host governments eager to capitalise on such global media exposure while at the same demanding ever more investment in security projects designed to safe-guard participants, spectators and the interests of government sponsors. But the flag can also matter in more mundane ways as well; the flag that might hang from someone’s house barely noticed but a powerful marker of geopolitical possibilities which extend far beyond national identification.

Fifth, and finally, the second edition was a welcome opportunity to remind readers that geopolitics is always embodied. It is not abstract. It is not something merely preoccupied with the global. It is a subject matter that is resolutely everyday. Geopolitics is about the various ways the geographies of politics are made to matter and the manner in which the local, national, regional and global co-constitute one another. Feminist geographers have been at the vanguard of this realisation and demonstrating how bodies, sites, objects and practices are inter-linked to one another and capable of producing very real consequences for people, communities and environments. The border and associated border regimes provide a rich source of material; linking border control/policing ideologies to the mobility and vulnerability of bodies. Sites and environments matter as anyone who has attempted to cross the US-Mexican border or the Mediterranean in a ramshackle boat would testify. For many of those migrants the journey itself will be one they won’t survive.

Professor Klaus Dodds is Professor of Geopolitics at Royal Holloway University of London. Since publication of Geopolitics: A Very Short Introduction, he has co-edited three books, Spaces of Security and Insecurity (2009), Observant States: Geopolitics and Visual Culture (2010), and The Ashgate Handbook on Critical Geopolitics (2012). He has also written The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction. The new edition of Geopolitics: A Very Short Introduction publishes this month.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: © Marie-Lan Nguyen / CC-BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The post What has changed in geopolitics? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDerrida on the madness of our timeApples and carrots count as wellTen landscape designers who changed the world

Related StoriesDerrida on the madness of our timeApples and carrots count as wellTen landscape designers who changed the world

June 19, 2014

Political apparatus of rape in India

Last week the Guardian reported, “A state minister from Indian prime minister Narendra Modi’s ruling party has described rape as a ‘social crime’, saying ‘sometimes it’s right, sometimes it’s wrong’, in the latest controversial remarks by an Indian politician about rape.” While horrified by these comments, I remembered that a book from OUP India’s office had recently landed on my desk and the author, Pratiksha Baxi, might be able to shed some light on the issue of rape in India for Westerners. Below is a post Baxi sent in response to my query following the story mentioned above. –Christian Purdy, Director of Publicity

By Pratiksha Baxi

In the wake of the Delhi gang rape protests in 2013-2014, a section of the western media was critiqued for representing sexual violence as a form of cultural violence. For instance, a white woman reporter said to a friend, ‘we are filming Indian women of all kinds. You look modern. Please, can you say—I am India’s daughter’. Not fazed by the angry refusal, the reporter found some other ‘modern’ looking woman to mime this script for the camera. The Delhi protests became a resource for a certain kind of racialized sexual politics, which looped back to a nationalist rhetoric decrying the tarnishing of the image of the country abroad. Indian politicians responded by blaming the media, feminists, and the protests for sensationalising rape, and producing the crisis now posed to the image of a globalising economy.

The national and international political debates ignore Indian feminists and law academics—who innovated new juridical categories such as custodial rape and power rape—leading the path to conceptualise rape as a specific technique of state and social dominance. They do not cite the learning of subaltern or Black feminists of the Global South. Nor are different jurisdictions compared to raise more serious questions about the cunning nature of law reform in neo-liberal contexts. Although there has been feminist research on rape, feminist interventions in international law and several global collaborations to combat violence against women, there seems to be an inability to carry the complexities of these debates in the national and international mainstream media.

Protests at Safdarjung Hospital. Photo by Ramesh Lalwani. CC BY-NC 2.0 via ramesh_lalwani Flickr.

In India, the political rhetoric on rape continues to deploy conventional scripts: boys will be boys; sometimes it’s right, sometimes it’s wrong; alcohol causes men to rape. There is a political refusal to recognise that rape is central to dominance, a routinized expression of sexualised power. Nor is it in political interest to displace the use of rape as a form of social control. Rather rape becomes a means of doing competitive party politics or as a technique of consolidating power.

Sexual assault is used as a means to control dissenting bodies. Rape is a technique of terror that is used with impunity to control social mobility, stifle dissent, reassert social control, gain political control, and target ‘hated’ communities. There is no serious attempt to challenge this kind of rape culture, which inhabits the cultures of policing. It is a political apparatus of sexual terror, not to be confused with theories of male sexuality or as evidence of cultural predispositions. Rather this rape culture rests on a political apparatus, which has several organised features.

First, it rests on a system of policing and law enforcement, which makes rape look like consensual sex, and consensual sex look like rape. For example, the use of the rape, kidnapping and abduction laws to criminalize love across caste or community is rampant, whilst rape as a form of caste dominance is scarcely taken seriously.

Second, the political apparatus of rape deploys violence to produce the public secrecy of rape: while everyone knows that women are raped, we are told no one must talk about it.

Third, this political apparatus rests on a scripted representational regime that attributes the blames of rape to women, alcohol, literacy, poverty, public access and so on—everything but the structures of dominance in a globalising economy. It institutionalises a politics of forgetting—from the traumatic histories of mass sexual violence to caste atrocities—we are told that there is no connection between everyday and mass scale sexual violence.

Fourth, it denies the link between the dispossession of the marginalised from property or land, and the growing rate of sexual violence. In the Baduan rape and lynching case, the children went out to the fields of the dominant caste to relieve themselves. The subsequent demand for bathrooms for dalit women is an expression of this dispossession, which makes them vulnerable to brutal sexual violence, murder and lynching.

Fifth, such a political apparatus acts as a thought police. It denies the right to sexual autonomy and choice. And it rewards those politicians who rape, riot, murder, censor or humiliate.

All this means that there is complicity between state and society in privileging rape as the expression of male power. The state conserves and even stokes the desire to rape as the foundational tool of male power. This is a political trait, not a cultural trait. There is an ever-expanding indifference to sexual violence survivors, which seems to be in inverse proportion to the anti-rape protests. For instance, even today a spare pair of clothes is not provided to rape survivors when their clothes are confiscated as evidence in police stations or hospitals.

Sexual violence can be prevented and redressed if this political apparatus is disbanded. To destroy this political apparatus, the doing of politics—local, national and international must change. Rather than engaging in an aggressive and masculine competition over crime statistics, politicians must engage seriously with the nature of institutional reform and response to sexual violence.

In the context of the international laws and policies on violence against women, the new government must allocate generous gender budgets to provide essential facilities to rape survivors and institute measures to prevent sexual violence. This must accompany zero tolerance for rape of women, men, sexual minorities and children. The recommendations to criminalise marital rape; repeal the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act and legislate against rape as a mass crime must be implemented. Section 377 IPC, a colonial law criminalizing homosexuality must be repealed. In other words, sexual autonomy and sexual dignity must be respected. This means that the conventional notions of sexual morality, which regulate women’s sexuality, pathologize queer sexuality and celebrate violent masculinity, must no longer lay the foundations of the Indian polity. National and international politics must recognise rape as political violence rather than cultural violence; substitute the language of ‘rescue’ with repatriation and learn from languages of social suffering rather than vocabularies of power.

Pratiksha Baxi is Associate Professor, Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and author of Public Secrets of Law: Rape Trials in India (OUP India, 2014)

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Political apparatus of rape in India appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFelipe VI, Spain’s new king: viva el reyPutting an end to warCelebrating Trans Bodies, Trans Selves

Related StoriesFelipe VI, Spain’s new king: viva el reyPutting an end to warCelebrating Trans Bodies, Trans Selves

Telemachos in Ithaca

How do you hear the call of the poet to the Muse that opens every epic poem? The following is extract from Barry B. Powell’s new free verse translation of The Odyssey by Homer. It is accompanied by two recordings: one of the first 105 lines in Ancient Greek, the other of the first 155 lines in the new translation. How does your understanding change in each of the different versions?

Sing to me of the resourceful man, O Muse, who wandered

far after he had sacked the sacred city of Troy. He saw

the cities of many men and he learned their minds.

He suffered many pains on the sea in his spirit, seeking

to save his life and the homecoming of his companions.

But even so he could not save his companions, though he wanted to,

for they perished of their own folly—the fools! They ate

the cattle of Helios Hyperion, who took from them the day

of their return. Of these matters, beginning where you want,

O daughter of Zeus, tell to us.

Now all the rest

were at home, as many as had escaped dread destruction,

fleeing from the war and the sea. Odysseus alone

a queenly nymph, Kalypso, a shining one among the goddesses,

held back in her hollow caves, desiring that he become

her husband. But when, as the seasons rolled by, the year came

in which the gods had spun the threads of destiny

that Odysseus return home to Ithaca, not even then

was he free of his trials, even among his own friends.

All the gods pitied him, except for Poseidon.

Poseidon stayed in an unending rage at godlike Odysseus

until he reached his own land. But Poseidon had gone off

to the Aethiopians who live faraway—the Aethiopians

who live split into two groups, the most remote of men—

some where Hyperion sets, and some where he rises.

There Poseidon received a sacrifice of bulls and rams,

sitting there and rejoicing in the feast.

The other gods

were seated in the halls of Zeus on Olympos. Among them

the father of men and gods began to speak, for in his heart

he was thinking of bold Aigisthos, whom far-famed Orestes,

the son of Agamemnon, had killed. Thinking of him,

he spoke these words to the deathless ones: “Only consider,

how mortals blame the gods! They say that from us

comes all evil, but men suffer pains beyond what is fated

through their own folly! See how Aigisthos pursued

the wedded wife of the son of Atreus, and then he killed

Agamemnon when he came home, though he well knew

the end. For we spoke to him beforehand, sending Hermes,

the keen-sighted Argeïphontes, to say that he should not kill

Agamemnon and he should not pursue Agamemnon’s wife.

For vengeance would come from Orestes to the son of Atreus,

once Orestes came of age and wanted to reclaim his family land.

So spoke Hermes, but for all his good intent he did not persuade

Aigisthos’ mind. And now he has paid the price in full.”

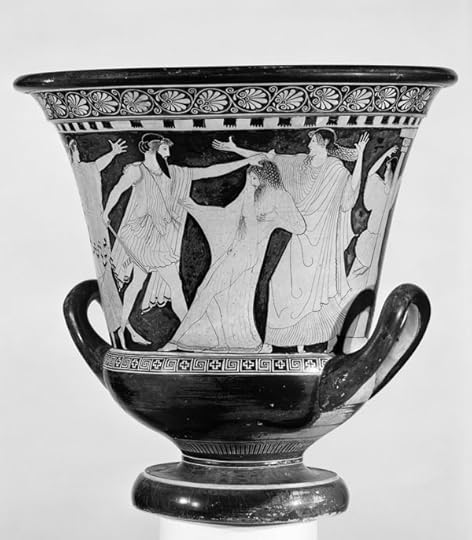

Aigisthos holds Agamemnon, covered by a diaphanous robe, by the hair while he stabs him with a sword. Apparently this illustration is inspired by the tradition followed in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, where the king is caught in a web before being killed. Klytaimnestra stands behind Aigisthos, urging him on, while Agamemnon’s daughter attempts to stop the murder (she is called Elektra in Aeschylus’ play). A handmaid flees to the far right. Athenian red-figure wine-mixing bowl, c. 500–450 BC. W. F. Warden Fund © Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 63.1246.

Then the goddess, flashing-eyed Athena, answered him:

“O father of us all, son of Kronos, highest of all the lords,

surely that man has fittingly been destroyed. May whoever

else does such things perish as well! But my heart

is torn for the wise Odysseus, that unfortunate man,

who far from his friends suffers pain on an island surrounded

by water, where is the very navel of the sea. It is a wooded

island, and a goddess lives there, the daughter of evil-minded

Atlas, who knows the depths of every sea, and himself

holds the pillars that keep the earth and the sky apart.

Kalypso holds back that wretched, sorrowful man.

Ever with soft and wheedling words she enchants him,

so that he forgets about Ithaca. Odysseus, wishing to see

the smoke leaping up from his own land, longs to die. But your

heart pays no attention to it, Olympian! Did not Odysseus

offer you abundant sacrifice beside the ships in broad Troy?

Why do you hate him so, O Zeus?”

Zeus who gathers the clouds

then answered her: “My child, what a word has escaped the barrier

of your teeth! How could I forget about godlike Odysseus,

who is superior to all mortals in wisdom, who more than any other

has sacrificed to the deathless goes who hold the broad heaven?

But Poseidon who holds the earth is perpetually angry with him

because of the Cyclops, whose eye he blinded—godlike

Polyphemos, whose strength is greatest among all the Cyclopes.

The nymph Thoösa bore him, the daughter of Phorkys

who rules over the restless sea, having mingled with Poseidon

in the hollow caves. From that time Poseidon, the earth-shaker,

does not kill Odysseus, but he leads him to wander from

his native land. But come, let us all take thought of his homecoming,

how he will get there. Poseidon will abandon his anger!

He will not be able to go against all the deathless ones alone,

against their will.”

Then flashing-eyed Athena, the goddess,

answered him: “O our father, the son of Kronos, highest

of all the lords, if it be the pleasure of all the blessed gods

that wise Odysseus return to his home, then let us send Hermes

Argeïphontes, the messenger, to the island of Ogygia, so that

he may present our sure counsel to Kalypso with the lovely tresses,

that Odysseus, the steady at heart, need now return home.

And I will journey to Ithaca in order that I may the more

arouse his son and stir strength in his heart to call the Achaeans

with their long hair into an assembly, and give notice to all the suitors,

who devour his flocks of sheep and his cattle with twisted horns,

that walk with shambling gait. I will send him to Sparta and to sandy

Pylos to learn about the homecoming of his father, if perhaps

he might hear something, and so that might earn a noble fame

among men.”

So she spoke, and she bound beneath her feet

her beautiful sandals—immortal, golden!—that bore her

over the water and the limitless land together with the breath

of the wind. She took up her powerful spear, whose point

was of sharp bronze, heavy and huge and strong,

with which she overcomes the ranks of warriors when she is angry

with them, the daughter of a mighty father. She descended

in a rush from the peaks of Olympos and took her stand

in the land of Ithaca in the forecourt of Odysseus, on the threshold

of the court. She held the bronze spear in her hand, taking on

the appearance of a stranger, Mentes, leader of the Taphians.

There she found the proud suitors. They were taking their pleasure,

playing board games in front of the doors, sitting on the skins

of cattle that they themselves had slaughtered. Heralds

and busy assistants mixed wine with water for them

in large bowls, and others wiped the tables with porous sponges

and set them up, while others set out meats to eat in abundance.

Godlike Telemachos was by far the first to notice

her as he sat among the suitors, sad at heart, his noble

father in his mind, wondering if perhaps he might come

and scatter the suitors through the house and win honor

and rule over his own household. Thinking such things,

sitting among the suitors, he saw Athena. He went straight

to the outer door, thinking in his spirit that it was a shameful thing

that a stranger be allowed to remain for long before the doors.

Standing near, he clasped her right hand and took the bronze

spear from her. Addressing her, he spoke words that went

like arrows: “Greetings, stranger! You will be treated kindly

in our house, and once you have tasted food, you will tell us

what you need!”

So speaking he led the way, and Pallas Athena

followed. When they came inside the high-roofed house,

Telemachos carried the spear and placed it against a high column

in a well-polished spear rack where were many other spears

belonging to the steadfast Odysseus. He led her in and sat her

on a chair, spreading a linen cloth beneath—beautiful,

elaborately-decorated—and below was a footstool for her feet.

Beside it he placed an inlaid chair, apart from the others,

so that the stranger might not be put-off by the racket and fail

to enjoy his meal, despite the company of insolent men.

Also, he wished to ask him about his absent father.

A slave girl brought water for their hands in a beautiful golden

vessel, and she set up a polished table beside them.

The modest attendant brought out bread and placed it before them,

and many delicacies, giving freely from her store. A carver

lifted up and set down beside them platters with all kinds

of meats, and set before them golden cups, while a herald

went back and forth pouring out wine for them.

In came the proud suitors, and they sat down in a row

on the seats and chairs, and the heralds poured out water for

their hands, and women slaves heaped bread by them in baskets,

and young men filled the wine-mixing bowls with drink.

The suitors put forth their hands to the good cheer lying before them,

and when they had exhausted their desire for drink and food,

their hearts turned toward other things, to song and dance.

For such things are the proper accompaniment of the feast.

A herald placed the very beautiful lyre in the hands of Phemios,

who was required to sing to the suitors. And he thrummed the strings

as a prelude to song.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His new free verse translation of The Odyssey was published by Oxford University Press in 2014.His translation of The Iliad was published by Oxford University Press in 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Telemachos in Ithaca appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFaith and science in the natural worldA 2014 summer songs playlistPutting an end to war

Related StoriesFaith and science in the natural worldA 2014 summer songs playlistPutting an end to war

A 2014 summer songs playlist

Now that summer is finally here – dog-eared paperbacks and sunglasses dusted off and put to good use – it’s also time to figure out what we should be listening to as we loll about in the sun. While the media seem more concerned with which current pop hit will become the unofficial “Song of the Summer” (Pharrell’s “Happy”? Iggy Azalea’s “Fancy”?), here at OUP, we have instead zeroed in on songs from summers past. Ranging all the way back to 1957 (for Ella and Louis’s take on Gershwin’s classic “Summertime”) and all the way over to Germany (for Dutch television host Rudi Carrell’s fanciful ode to sommer on the North Sea), we have pulled together a diverse and inspired set of tunes to take along to the beach, or the Pizza Hut, or the New York City streets, or wherever you should find yourself this summer!

“Summertime” – Kenny Chesney

I’ve been to his amazing concerts at MetLife Stadium for the past three years and this song has been my anthem ever since. “And it’s two bare feet on the dashboard / Young love and an old Ford / Cheap shades and a tattoo / And a Yoo-Hoo bottle on the floorboard.”

— Leslie Schaffer, Special Accounts Sales Rep

[image error]

The Lovin’ Spoonful, best known for their 1966 summer smash “Summer in the City,” make two appearances on our Summer Songs playlist. Public domain, via Wikimedia

“Summer in the City” – The Lovin’ Spoonful

Now that I live and work in New York City this song speaks to me. While the summer days are brutal and exhausting, the nights are wonderful. During the day we are tortured by sweltering sidewalks, oven-like subway stations, and loud construction noises, but at night the city cools off and comes alive again. There’s nothing I love more than drinks on a rooftop in the summer. In fact, I think that’s what I’ll do tonight.

— Christie Loew, Assistant Manager Accounts and Merchandising

“Summer of Panic” – Hanoi Janes

“Summer Bonfire” – Great Lakes Myth Society

“Summer Wine” – Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazlewood

“Vacation” – the Go-Gos

The song that’s been my summer anthem since it came out in 2010 is Hanoi Janes’s “Summer of Panic.” The song’s frenetic pace, distorted and muted vocals, and a mix of old school chords with what Pitchfork reviewer Jayson Greene called “swarms of wiggling B-movie lasers” make for a psychotic surf music vibe that can’t be beat. It perfectly captures my love-hate relationship with summer, where I feel such pressure to have fun while it lasts, that it becomes panic-inducing. Its companion piece, Great Lakes Myth Society’s “Summer Bonfire,” might sound less fraught with anxiety, but only because some of the verses trail off, leaving you to supply the missing rhyme that, for instance, turns “electric” into “electric chair.” But for those times when I am able to relax, Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazlewood’s “Summer Wine” is a must listen. Hazlewood plays the role of a cowboy whom Sinatra seduces, drugs, and eventually robs. Nevertheless, the languid tempo, their sultry vocal blend and the brass chorus somehow makes this odd song sound like a hot summer night. I am now considering that as my three favorite summer songs involve nervous breakdowns, capital punishment, and committing felonies, I might need a long summer vacation. There’s always the Go-Gos.

— Anna-Lise Santella, Editor, Grove Music/Oxford Music Online and Music Reference

“Jalapeno Lena” – Rockin’ Sidney

The Summer of ’88 was the first year I didn’t return home from college but stayed in Plattsburgh to live and work the summer away at two part-time jobs. In the morning I prepped at Pizza Hut, “makin’ it great.” That summer must have been around the time Dirty Dancing came out because the jukebox played “Time of My Life” by Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes ad nauseum. To break up the nauseum, my fellow prepper, Snooze Warner, and I would play any random, little-known songs we could find in that jukebox. Then one day we stumbled upon “Jalapeno Lena” by Rockin’ Sidney and we thought it was brilliant. Whenever someone played “Time of My Life,” we ran out and played “Jalapeno Lena.” It has a killer zydeco beat that helped us beat the heat of the summer of ’88, a hot summer in Plattsburgh, NY only made hotter by “Jalapeno Lena” and the ovens of Pizza Hut.

— Purdy, Director of Publicity

“See No Evil” – Television

Summer vacations back from college were all about driving up and down the coast of Maine in my dad’s old beat-up convertible, blasting Marquee Moon and Fun House and Unknown Pleasures and Blank Generation on burned CDs. The disc cartridge was in the trunk, so if you wanted to put in something different, you had to pull over and get out. Whenever I hear those records, that’s where I go.

— Owen Keiter, Associate Publicist

“Everybody Loves the Sunshine” – Roy Ayers

“I Get Lifted” – George McCrae

Breezy and light, “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” gets to the core of a lazy day in the sweltering sun. As for “I Get Lifted,” if I had a drop top in the city, this is what I would blast driving in July.

— Stuart Roberts, Editorial Assistant

“Feel Good Inc.” – Gorillaz

One of the hit singles from the cartoon band Gorillaz, this was song of the summer in 2005! According to Wikipedia it is the only song by any one of Damon Albarn’s several bands (including Blur and The Good, the Bad, and the Queen) to hit the Billboard Top 40.

— Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Publicity Manager

Click here to view the embedded video.

“Wann wird’s mal wieder richtig Sommer” – Rudi Carrell

This German Schlager favorite is sung to the tune of “City of New Orleans” and became summer song of the year in 1975. And this video version from Carrell’s TV show isn’t to missed. The lyrics describe a singer nostalgic for heat waves that he used to experience on the North Sea. (!)

— Norm Hirschy, Editor, Music Books

“Coconut Grove” – The Lovin’ Spoonful

“Summertime” – Jason Rebello

“Long Long Summer” – Dizzy Gillespie

There are a few Lovin’ Spoonful songs I could have chosen – “Summer in the City” being an obvious one – but it is “Coconut Grove” that reminds me most of sitting on a beach at sunset. As for George Gershwin’s “Summertime”, there are so many versions that many of them are classics themselves. But when I first heard Jason Rebello’s arrangement from his 1994 album Make it Real, it felt so new and exciting. And then Dizzy Gillespie’s sound is sunshine itself! I could have picked any number of his songs for this playlist, but this is the track that I play when the sun comes out.

— Miriam Higgins, Music Hire Librarian

“Sweet Amarillo” – Old Crow Medicine Show

Not to say that I’m at all over the rollicking Dylan-Old Crow collaboration that is “Wagon Wheel,” this next 40-years-in-the-making tune is equally excellent. According to OCMS frontman Ketch Secor, Dylan’s management company sent the band a cassette with the song fragment along with a set of instructions for how Dylan wanted the song to be completed, and – voilà! – Ketch and company make Americana magic once again!

— Taylor Coe, Marketing Associate, Academic/Trade Books

“Here’s to the Night” – Eve 6

When I was in high school, I spent every summer up in the Santa Cruz Mountains, working at a small summer camp called Forest Footsteps. That camp will always hold a special place in my heart and to this day, I still consider my fellow staff members and the campers as my extended family. On the last night of each week, we had a camp-wide “Boogie” with all the kids where we danced to an assortment of classic oldies and fun summer tunes. The final song was always “Here’s to the Night” by Eve 6 and as soon as the first few notes played, everyone would circle up in the middle of the dance floor and put their arms around one another, singing and swaying together as a group. Even the most introverted kids would find their way into the circle, embraced by their cabin mates. It was a really beautiful way to wrap up the week and that song still brings a tear to my eye, in the best possible way.

— Carrie Napolitano, Marketing Assistant, Academic/Trade Books

“Steal My Sunshine” – Len

Nothing says driving around town with the top down like this song.

— Sarah Hansen, Publicity Assistant

“Sunny Afternoon” – The Kinks

“Lazing on a sunny afternoon . . .” Need I say more?

— Louise Bowler, Senior Marketing Executive, Journals

“Postcards from Italy” – Beirut

My favorite summer song is “Postcards from Italy” by Beirut. It has such a romantic, old-timey feel to it. Even its title oozes summer – when I hear “postcards” and “Italy” I think of sunshine, the Mediterranean sea, and, of course, gelato! It also helps that the opening bars are played on a ukulele – the quintessential summer instrument! Bellisima.

— Mary Teresa Madders, Marketing Assistant, Journals

“Endless Summer” – The Jezabels

“Miami” – Will Smith

“April Come She Will” – Simon and Garfunkel

The summer-ness of The Jezabels’ “Endless Summer” comes down to this: You’re sixteen and the summer holidays are never going to end. You can practically feel the sweat run down your back as you laze on the beach with your holiday romance. And of course there’s “Miami,” the quintessential summer tune by the great Will Smith. Bringing rap to the masses, this accessible classic will have even your nan nodding her head. Or maybe she would prefer the short but sweet Simon and Garfunkel tune “April Come She Will,” which, with a hint of that classic Watership Down soundtrack, offers a bittersweet metaphor of birth, life, and death. Perfect for a pensive summer afternoon.

— Simon Turley, Marketing Assistant, Journals

“Summertime” – Ella Fitzgerald & Louis Armstrong

This song lulls like a summer afternoon, rocking on the back porch watching the day go slowly, gently by.

— Anna Hernandez-French, Assistant Editor, Journals

Taylor Coe is a Marketing Associate at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A 2014 summer songs playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMary Lou Williams, jazz legendAn intriguing, utterly incomplete history of Louis ArmstrongComposer and cellist Aaron Minsky in 12 questions

Related StoriesMary Lou Williams, jazz legendAn intriguing, utterly incomplete history of Louis ArmstrongComposer and cellist Aaron Minsky in 12 questions

Putting an end to war

War is hell. War kills people, mainly non-combatant civilians, and injures and maims many more — both physically and psychologically. War destroys the health-supporting infrastructure of society, including systems of medical care and public health services, food and water supply, sanitation and sewage treatment, transportation, communication, and power generation. War destroys the fabric of society and damages the environment. War uproots individuals, families, and often entire communities, making people refugees or internally displaced persons. War diverts human and financial resources. War reinforces the mistaken concept that violence is an acceptable way of resolving conflicts and disputes. And war often creates hatreds that are passed on from one generation to the next.

During the Korean War, a grief stricken American infantryman whose friend has been killed in action is comforted by another soldier. In the background, a corpsman methodically fills out casualty tags. Haktong-ni area, Korea. August 28, 1950. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

War is hell. Yet we, as a society, have sanitized the reality of “war” in many ways. In the absence of a draft, many of us have no direct experience of war and do not even personally know people who have recently fought in war. And the US Congress has long since ceded to the President its authority to declare war.

The government and the media infrequently use the word “war.” Instead, they use many euphemisms for “war,” such as “military campaign” and “armed conflict,” and for the tactics of war, like “combat operations” and “surgical strikes.” Nevertheless, we, as a society, often think in a war-like context. We use “war” as a metaphor: the War on Poverty, the War on Cancer, the War on Drugs. And militaristic metaphors pervade the language of medicine and public health: Patients battle cancer. Physicians fight AIDS. Health care providers addressing especially challenging problems work on the front lines or in the trenches. Public health workers target vulnerable populations. And the main office of the leading professional organization in public health is called “headquarters.”

We envision a world without war and see the need to develop the popular and political will to end war. To create a world without war, we, as a society, would need to stop using sanitized phrases to describe “war” and to stop thinking in a militaristic context. But much more would need to be done to create a world without war.

A central concept in public health for the prevention of disease is the use of a triangle, with its three points labeled “host,” “agents,” and “environment.” This concept could be applied for developing strategies to create a world without war — strategies aimed at the host (people), strategies aimed at agents (weapons of war and the military), and strategies aimed at the environment (the conditions in which people live).

Strategies aimed at people could include promoting better understanding and more tolerance among people and among nations, promoting economic and social interdependency among nations, promoting nonviolent resolution of disputes and conflicts, and developing the popular and political will to prevent war and promote peace.

Strategies aimed at weapons of war and the military could include controlling the international arms trade, eliminating weapons of mass destruction, reducing military expenditures, and intervening in disputes and conflicts to prevent war.

Strategies aimed at improving the conditions in which people live — which often contribute to the outbreak of war — could include protecting human rights and civil liberties, reducing poverty and socioeconomic inequalities, improving education and employment opportunities, and ensuring personal security and legal protections.

War is hell. A world without war would be heavenly.

Barry S. Levy, M.D., M.P.H. is an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Tufts University School of Medicine. Victor W. Sidel, M.D. is Distinguished University Professor of Social Medicine Emeritus at Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein Medical College, and an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College. Dr. Levy and Dr. Sidel are co-editors of the recently published second edition of Social Injustice and Public Health as well as two editions each of the books War and Public Health and Terrorism and Public Health, all of which have been published by Oxford University Press. They are both past presidents of the American Public Health Association.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Putting an end to war appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTorture: what’s race got to do with it?The long, hard slog out of military occupationThis empire of suffering

Related StoriesTorture: what’s race got to do with it?The long, hard slog out of military occupationThis empire of suffering

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers