Oxford University Press's Blog, page 797

June 25, 2014

Undermining society – the Immigration Act 2014

Immigration it seems is always in the headlines. While UKIP and others make political waves with their opposition to European free movement, immigration is said to be one of the biggest issues of voter concern. However, the issues that make the headlines are only a tiny part of the picture. Restricting immigration is treated as an uncontroversial objective. Some air time, though less, is given to the damage done to migrants by restrictive laws and policies. Very little attention is given to the damage done to the social fabric by those same laws and policies, and to the reality that measures targeting migrants have an adverse effect on all of us.

In the last months of 2013 and the first of 2014 the Immigration Bill made its way through Parliament. Surprisingly, as immigration was a dominant political theme at that time, its provisions received minimal media attention. Provisions of the Immigration Act 2014 include:

All rights of appeal against immigration decisions are abolished, except where the decision is to refuse international protection or where removal would breach the Refugee Convention or the appellant’s human rights.

Banks and building societies are prohibited from opening accounts for individuals ‘who require leave to enter or remain in the UK but do not have it’.

Driving licences may not be issued to those who require leave but do not have it.

Charges for health care are to be levied on all migrants.

Landlords will be subject to penalties if they let property to individuals who ‘require leave to enter or remain in the UK but do not have it’.

The abolition of rights of appeal against immigration decisions comes after years of attrition of immigration appeal rights, and it is only this previous attrition that reduces the impact of these new measures.

Interestingly, an earlier episode of attrition of appeal rights was commented upon by Tony Blair in 1992:

“It is a novel, bizarre and misguided principle of the legal system that if the exercise of legal rights is causing administrative inconvenience, the solution is to remove the right. […] When a right of appeal is removed, what is removed is a valuable and necessary constraint on those who exercise original jurisdiction. That is true not merely of immigration officers but of anybody.”

Some effects of s.15 Immigration Act 2014 can be predicted:

There will be no independent remedy for an individual who has suffered due to a mistake.

There will be less incentive to improve Home Office decision-making.

Studies, work, and life plans of migrants and their families will be disrupted.

Employers and universities may lose employees and students.

Judicial review will likely proliferate.

When a student’s studies are prematurely ended or a specialist worker has to leave the country, not only they but others around them are affected. As well as the employer or university, friendships, treatment plans, agreements with landlords, voluntary work obligations, all are disrupted. Migrants do not live in isolation.

Most of us can accommodate to misfortune, but injustice is harder to live with. If our friend, our student or our colleague has not been able to put their case, what is the effect on our confidence in our own system of government? There is no right to be heard. Does this not have an impact on our belief in what are famously described as ‘British values’?

The prohibition on holding a driving licence, opening a bank or building society account not only affects the person who cannot get access to these basic features of ordinary life in the UK, it also affects the person who must decide whether to issue a licence or open an account.

A bank or building society employee must now assess a potential customer’s immigration status. Whether they wish to do so or not, the staff member is exercising a form of internal immigration control.

Bank and building society accounts have become essential to live ordinary life in the United Kingdom. People will be denied access to these facilities on faulty grounds. Bank and building society employees will find that their relationship with their customers has changed from service to scrutiny. All of us will be subject to immigration status checks.

The measures restricting access to private tenancies, bank and building society accounts and driving licences are not, as such, immigration control. They are penalties on those already resident. They apply not only to government matters but also to purely commercial and private transactions. They insert mutual surveillance into social relationships.

It was revealed by Sarah Teather MP that the government working group some of whose policies found their way into the Immigration Act was called ‘the Hostile Environment Working Group’. In the Immigration Act we are being recruited to the project of the hostile environment. We are required to treat other people as disentitled, not to a government benefit, which in the end we know is determined by government, but to a private facility. This asks us to change our perceptions of each other, and as such is hostile to us all.

Gina Clayton works on European asylum and migration projects, including reports for the Fundamental Rights Agency and the AIDA database, chairs refugee charities in South Yorkshire, and is an OISC adviser on asylum law. She is the author of Textbook on Immigration and Asylum Law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Gavel. By Kuzma, via iStockphoto.

The post Undermining society – the Immigration Act 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEconogenic harm, economists, and the tragedy of economicsClass arbitration at home and abroadNot learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia ago

Related StoriesEconogenic harm, economists, and the tragedy of economicsClass arbitration at home and abroadNot learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia ago

Econogenic harm, economists, and the tragedy of economics

In a recent editorial in the New York Times Harvard economist N. Gregory Mankiw acknowledged that economists have:

“only a basic understanding of how most policies work. The economy is complex, and economic science is still a primitive body of knowledge. Because unintended consequences are the norm, what seems like a utility maximizing policy can often backfire.”

Mankiw infers from this grave epistemic problem an ethical duty among economists to apply the Hippocratic principle “first do no harm” when assessing policy. On this basis he assails both the Affordable Care Act and new initiative in the US Congress to raise the legislated minimum wage. Both “fail the do-no-harm test”: the Affordable Care Act will lead to the termination of some insurance policies that don’t meet the standards required under the law, while raising the minimum wage “would disrupt some deals that workers and employers have made voluntarily.” But of course, applying the Hippocratic principle consistently would also require Mankiw to assail rather than support those policies to which he has an ideological affinity. Like free trade (which he supports), for instance, the harms of which to US workers surely exceed those of Obamacare. As J.R. Hicks recognized seventy-five years ago, any policy intervention that affects relative prices—which is to say, all interventions —“benefits those on one side of the market, and damages those on the other.” Surely Mankiw knows all this. What is troubling, then, is not Mankiw’s worry about the potential harm of the economic policies he opposes. He is quite right to expose the harms he associates with one policy or another. The problem is the ineptness and obvious bias with which he introduces ethical concerns into policy debate.

Now, it’s good to see an economist of Mankiw’s stature recognize in public view that economic science and policy analysis are fraught with uncertainty, and that there are risks of unintended harm to those whom economists purport to serve. Indeed, all professional practice entails a potential for harm to those whom professionals seek to serve, and to third parties. This is true in clinical medicine and public health, of course, but also in social work, engineering, law, and many if not most other professions. Partly in recognition of this fact some professions have established bodies of professional ethics in hopes of promoting responsible behavior by their members—behavior that minimizes the avoidable harms and that helps them manage appropriately the unavoidable harms that arise in the context of their practice. The medical profession is exemplary in this regard. In medical ethics we find the term “iatrogenesis” (from the Greek, “doctor-originating”) or “iatrogenic harm” which refers to the adverse effects or complications associated with medical treatment. The concept of iatrogenic harm captures physician- or clinic-induced harms ranging from those that are associated with malpractice to the unpreventable consequences of well-intentioned and expertly delivered medical interventions.

Economists, on the other hand, generally do not give sufficient attention to the ways that their own practice induces harm. We even lack the language to discuss economist-induced harm. There is no parallel in economics to the concept of medical malpractice, of course; economists are not held legally liable for their mistakes, no matter how severe the effects. More broadly, there is no economic analogue to the concept of iatrogenesis. There should be. We need a concept, and a corresponding term, to name what is as-of-yet unnamed. Let us refer to the harm economists cause with the term ‘econogenic harm.’

Why do we economists fail to examine sufficiently economic harm and econogenic harm, and why do they make such basic ethical errors when they do? First, economists recognize that harm is a regular and, likely, ineradicable feature of economic practice, as Hicks understood. It needs to be said plainly: economists are in the harm business. Almost always we cause harm as we try to do good. Hence, the Hippocratic directive “first, do no harm,” if taken as an inviolable mandate or a decision rule, has no relevance in economics since it would imply that economists can do nothing at all. Moreover, for over a century the economics profession has remained stubbornly uninterested in ethical matters.

The allergy to ethics manifests in part as a mistaken presumption that one can easily bifurcate economics into its ‘positive’ and ‘normative’ components, and that the economist should privilege positive science over normative speculations. But by its nature harm does not permit such a bifurcation. This is because all questions pertaining to harm—such as ascertaining when harm has occurred, the severity of harm, who or what is responsible for the harm, and which forms of harm are morally indictable and which are morally benign—all of these involve normative judgments. For instance, is a relatively poor person harmed by an economic policy like financial deregulation that overwhelmingly benefits the wealthy and exacerbates economic inequality (even if it doesn’t reduce her own income)? She may very well think so, and at least some economists such as Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, Thomas Piketty and Jamie Galbraith would validate her view on the matter. But many economists, including Mankiw, are apt to argue that the policy has not harmed anyone in any real sense provided no one’s income has been reduced. Who’s right in this case? Answering that question requires normative decisions about whether severe inequality induces harm to the disadvantaged and, if so, whether that harm is ethically worrisome; and about who should have the authority to answer that question—those actually affected by the policy, or the economist?

Finally, economics has been particularly dismissive of the idea of professional ethics. This attitude isn’t just unfortunate, it’s dangerous. Academic economists tend to think that their ethical duties are obvious—such as not stealing the ideas of others, not fabricating research results, and the like. Many don’t generally trouble themselves with the fact that the simplified blackboard economics that they use to instruct students in economic principles, which often presumes ideal background conditions, informs the simplistic manner in which many policymakers think about economic policy; and the related fact that their work can be misinterpreted and misapplied, with damaging consequences for others. Moreover, the large majority of economists in the United States today work outside of academia where they engage in applied work that bears directly on policy formation, regulation, and other government interventions; affects the outcome of legal disputes; entails consulting to private actors; influences financial market developments; etc. In all these areas the well-meaning economist can do substantial harm while trying to do good.

Yet, we have no professional economic ethicists, or any texts, journals, newsletters, curriculum, regular conferences, or other forums that explore systematically what it means to be an ethical economist, or what it means for economics to be an ethical profession. Unfortunately, the absence of professional economic ethics deprives us of a tradition of careful inquiry into the nature of and responsibility for econogenic harm.

This can’t be the proper attitude of a responsible profession that is committed to enhancing the welfare and freedoms of others. Instead, the prevalence and severity of econogenic harm carries an ethical burden for the economics profession to attend more carefully to the nature and distribution of the harms that its practice causes.

George F. DeMartino is the author of The Economist’s Oath: On the Need for and Content of Professional Economic Ethics . He is Professor of Economics at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. He writes widely on ethics and economics, as well as labor issues and political economy theory. The arguments that appear here are developed much more fully in “‘Econogenic Harm’: On the Nature of and Responsibility for the Harm Economists Do as they Try to Do Good,” to appear in George DeMartino and Deirdre McCloskey, eds., The Oxford University Press Handbook on Professional Economic Ethics (forthcoming).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: “Fall Hurricane Money Finance Currency Crisis” by Public Domain Pictures. Public domain via pixabay.

The post Econogenic harm, economists, and the tragedy of economics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNot learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia agoFixing the world after IraqCommon questions about shared reading time

Related StoriesNot learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia agoFixing the world after IraqCommon questions about shared reading time

How to prevent workplace cancer

Each year there are 1,800 people killed on the roads in Britain, but over the same period there are around four times as many deaths from cancers that were caused by hazardous agents at work, and many more cases of occupational cancer where the person is cured. There are similar statistics on workplace cancer from most countries; this is a global problem. Occupational cancer accounts for 5 percent of all cancer deaths in Britain, and around one in seven cases of lung cancer in men are attributable to asbestos, diesel engine exhaust, crystalline silica dust or one of 18 other carcinogens found in the workplace. All of these deaths could have been prevented, and in the future we can stop this unnecessary death toll if we take the right action now.

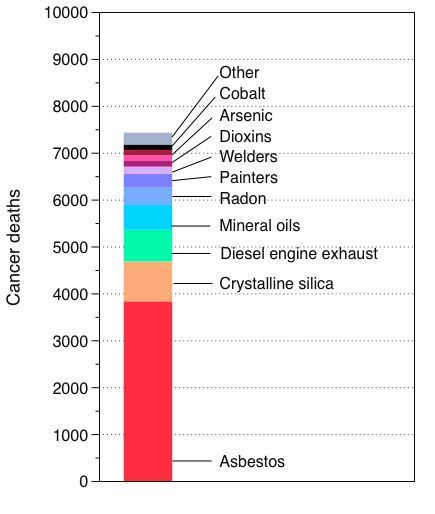

In 2009, I set out some simple steps to reduce occupational exposure to chemical carcinogens. The basis was the recognition that the overwhelming majority of workplace cancers from dusts, gases and vapours are caused by exposure to just ten agents or work circumstances, such as welding and painting (see chart). Focusing our efforts on this relatively short priority list could have a major impact.

Many of these exposures are associated with the construction industry. Almost all are generated as part of a process and are not being manufactured for industrial or consumer uses, e.g. diesel engine exhaust and the dust from construction materials that contain sand (crystalline silica).

The strategies to control exposure to these agents are well understood and so there is no need to invent new technological solutions for this problem. Use of containment, localized ventilation targeted at the source of exposure and other engineering methods can be used to reduce the exposures. If further control is needed then workers can wear personal protective devices, such as respirators, to filter out contaminants before they enter the body.

There are also robust regulations to ensure employers understand their obligations to employees, contractors and members of the public, both in Britain through the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) Regulations and in the rest of Europe via the Carcinogens and Mutagens Directive.

We know that as time goes on, most exposures in the workplace are decreasing by between about 5% and 10% each year. This seems to be true for many dusts, fibres, gases and vapours, and it is a worldwide trend. There is every reason to believe this is also true for the carcinogenic exposures we are discussing. This means that over a ten-year period the risk of future cancer deaths is may drop by about half. If we could increase the rate of decrease in exposure to 20% per annum then after 10 years the risk of future disease should have decreased by about 90%.

However, during the five years since my article was published, very little has been done to improve controls for carcinogens at work. Recent evidence from the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), the regulator in Britain, shows widespread non-compliance at worksites where there is exposure to respirable crystalline silica. Most people are still unaware of the cancer risks associated with being a painter or a welder and so no effective controls are generally put in place. There have been no effective steps taken to reduce exposure to diesel engine exhaust, or most of the other “top ten” workplace carcinogens. What is the barrier preventing change?

In my opinion, the main issue is that we don’t perceive most of these agents or situations as likely to cause cancer. For example, airborne dust on construction sites, which often contains crystalline silica and may contain other carcinogenic substances, is considered the norm. Diesel soot is ubiquitous in our cities and we all accept it even though it is categorized as a human carcinogen. In my paper I complained that there were ‘no steps taken to reduce the risk from diesel exhaust particulate emission for most exposed groups and no particular priority given to this by regulatory authorities.’ Nothing has changed in this respect. We need an agreed commitment from regulators, employers and workers to change for the better. Perhaps we need to consider requiring traffic wardens to wear facemasks and encourage painters to work in safer healthier ways. At least we should take a fresh look at what can reasonably be done to protect people.

We know that since 2008 the number of road traffic deaths in the United Kingdom has decreased by about a third and downward time trend seems relentless. Road traffic campaigners have envisaged a future of zero harm from motor vehicles. Similarly we know that the level of exposure to most workplace carcinogenic substances is decreasing. Can we not also consider a future world where we have eliminated occupational cancer or at least reduced the health consequences to a tiny fraction of today’s death toll? It will be a future that our children or their children will inhabit because of the long lag between exposure to the carcinogens and the development of the disease, but unless we act the danger is that we never see an end to the problem.

As a first step we need to have en effective campaign to raise awareness of the problem of workplace cancers and to start to change attitudes to the most pernicious workplace carcinogens.

John Cherrie is Research Director at the Institute of Occupational Medicine (IOM) in Edinburgh, UK, and Honorary Professor at the University of Aberdeen. He has been involved in several studies to estimate the health impact from carcinogens in the workplace. He is currently Principal Investigator for a study that will estimate the occupational cancer and chronic non-malignant respiratory disease burden in the constructions sector in Singapore. In 2014 he was awarded the Bedford Medal for outstanding contributions to the discipline of occupational hygiene. He is the author of the paper ‘Reducing occupational exposure to chemical carcinogens‘, which is published in the journal Occupational Medicine.

Occupational Medicine is an international peer-reviewed journal, providing vital information for the promotion of workplace health and safety. Topics covered include work-related injury and illness, accident and illness prevention, health promotion, occupational disease, health education, the establishment and implementation of health and safety standards, monitoring of the work environment, and the management of recognised hazards.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Graph provided by the author. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post How to prevent workplace cancer appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInvesting for feline futuresThe legacy of critical careWorld No Tobacco Day 2014: Raise taxes on tobacco

Related StoriesInvesting for feline futuresThe legacy of critical careWorld No Tobacco Day 2014: Raise taxes on tobacco

June 24, 2014

Common questions about shared reading time

Throughout the process of reading development, it is important to read with your child frequently and to make the experience fun, whether your child is a newborn or thirteen. This may not sound like news to many parents, but the American Academy of Pediatrics is just announcing their new recommendation that parents read with their children daily from infancy on, and it is expected that this announcement will serve as a reminder to many parents and a call for educators and policymakers to help parents who lack the time, resources, and skills to read with their children encourage reading development. We are so excited about this new development because the benefits of shared reading accrue over time and we believe that this announcement will create the energy needed to help many young children become successful, motivated readers.

Although reading together is important at all ages, the specific strategies parents use will change dramatically as their children get older. The strategies parents use will also be dependent upon their children’s interests, temperament, and abilities. There is no one “right” way to read together.

Figuring out the best way to engage in shared reading with a child while he or she is young gives parents an opportunity to use cuddle time together as a way to also help a child understand a book more deeply, and to simultaneously teach specific reading skills. Perhaps as important, children who have an enthusiastic reader as a role model may stay determined to learn to read, even when facing challenges, rather than becoming easily discouraged. The magic of shared reading comes from this combination of warm, interpersonal experiences, playful and captivating storytelling, and opportunities for learning. This winning combination helps children not only learn to read, but learn to love and value reading.

There are many questions that parents often ask about reading together with their children, and some of those questions are answered below. We hope that thinking through these issues inspires parents to start reading with their children regularly (even if they are already a bit older), and create family reading rituals that last a lifetime!

How can I get my child more engaged in reading time?

If you are having difficulty engaging your child in reading time, try searching for books on topics that she finds interesting (even if those topics are not ones that you find engaging). If your child enjoys looking at comic books, embrace this type of reading, rather than discouraging it. Although it might be surprising to hear, they include much richer language than we encounter in a typical day. Reading any printed material also helps children get comfortable turning pages, and give you the chance to talk with your child about new ideas and vocabulary words.

Many children also respond well to having some freedom and getting to make choices during reading time. You may want to let your child to choose the book you will be reading, whether you are picking books out in the library or off your own bookshelf. You can also let your child select where and when you will read…within reason, of course.

Most importantly, try to make the reading experience enjoyable by focusing on what goes well. Praise your child just for sitting down with you to read, even if she only wants to sit briefly. The next day, try to get her to sit through a few pages of the story and sit a bit longer. Reading time should be a time to relax and bond with your child. If she acts up, simply end reading time, but do so calmly and try again later.

How do I know if my child is actually listening while I am reading to him/her?

Asking questions throughout the story that actively engage your child in the reading process should encourage him to listen more closely while you are reading. If you think your child is not listening as you read, try asking a question or two on each page in order to get your child to interact with the story and actively express himself. If he seems particularly distracted, simply end reading time, but do so calmly and try again later.

Click here to view the embedded video.

How long should I spend trying to explain something to my child if they get frustrated?

Reading time should be a relaxing, bonding experience for both you and your child. Rather than trying to teach many new skills during any one reading session, pick just one idea to focus on each day, whether it is a new vocabulary word or letter to identify. Setting manageable reading goals will help make this time feel fun, rather than stressful, for you both.

If you ask a question about a book that your child is having trouble understanding, respond calmly and either restate your question in a simpler way or give a clue regarding the correct answer. If she seems to be frustrated, move on and return to the concept at another time. Story concepts might become clearer to children with repeated readings of the same story.

What if my child wants to read the same book every night?

Repeated readings of a story actually help children to more deeply understand the plot. In addition, your child will grow more familiar with the story and the words that make it up. You can even try having your child read to you. If he is familiar with the book, he might be able to decode words he would not be able to decode in an unfamiliar context. If your child is not ready to actually read the words on the pages, have him retell the story to you using the pictures and what he recalls from other readings of the story. By asking questions and making comments, you can continue to build his vocabulary and background knowledge, even while reading a familiar story.

Anne E. Cunningham, Ph.D. and Jamie Zibulsky, Ph.D. are the authors of Book Smart: How to Develop and Support Successful, Motivated Readers. Anne Cunningham is Professor of Cognition and Development at University of California Berkeley Graduate School of Education and Jamie Zibulsky is Assistant Professor of Psychology at Fairleigh Dickinson University. Learn more at Book Smart Family. Suggestions are adapted from Book Smart: How to Develop and Support Successful, Motivated Readers by Anne E. Cunningham and Jamie Zibulsky. Read their previous blog posts. Chelsea Schubart is a doctoral student in School Psychology at Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Common questions about shared reading time appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesParent practices: change to develop successful, motivated readersCommon Core Standards, universal pre-K, and educating young readersMusic parenting’s unexpected, positive benefits

Related StoriesParent practices: change to develop successful, motivated readersCommon Core Standards, universal pre-K, and educating young readersMusic parenting’s unexpected, positive benefits

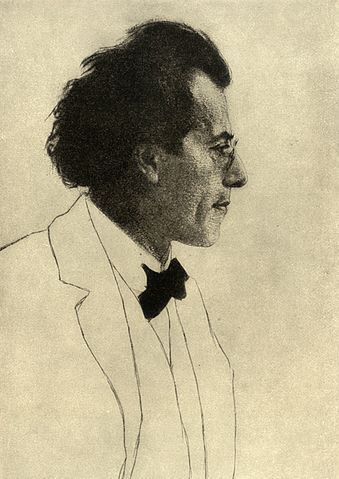

New questions about Gustav Mahler

For many years, scholarship on composer Gustav Mahler’s life and work has relied heavily on Natalie Bauer-Lechner’s diary. However, a recently discovered letter, introduced, translated, and annotated by Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling, and published for the first time in the journal The Musical Quarterly, sheds new light on the private life of the great composer. New revelations about various relationships, including Bauer-Lechner’s romantic involvement with the composer, sketch out his personal character and provide a more nuanced portrait. We spoke with Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling about the impact on Mahler scholarship.

Gustav Mahler, photo of the etching by Emil Orlik (1903), in the Groves Dictionary and New Outlook (1907). Collections Walter Anton. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

How will the publication of this letter affect the current body of Mahler scholarship?Natalie Bauer-Lechner is the primary witness to roughly 10 years of Gustav Mahler’s life; biographers and historians have continually relied on her accounts to shed light on Mahler’s works and thoughts, especially during the 1890s. In this letter, three main topics are discussed in ways never before documented in Mahler studies: (1) Mahler’s various romantic involvements before his marriage to Alma Schindler in 1902; (2) the role of Justine Mahler, the composer’s sister, in his personal interactions with these women; and (3) Natalie Bauer-Lechner’s two brief periods of sexual relations with Mahler, at the beginning and at the end of her 12-year relationship.

The implications go beyond the merely biographical, as it reveals the author in a liaison – long-suspected by some scholars – with the object of her recollections. How, then, do we evaluate her writings? How trustworthy is the information they claim to provide? Since Bauer-Lechner has heretofore been considered absolutely reliable, the ramifications of a revision of this stance could have far-reaching consequences.

How was this letter discovered, and what kept it from being published for so long?

The letter had been in private hands until it appeared in the shop of a Viennese rare books dealer and was sold to the Music Collection of the Austrian National Library in the fall of 2012. The authors first became aware of the document in the spring of 2012 when it became known that the owner had attempted (unsuccessfully) to sell the letter through the Dorotheum Auction House in Vienna in May 2011. How the letter ended up in this person’s possession has not (yet) been determined. Its authenticity is firmly established.

Does the publication of this letter vindicate, or just as equally cast into doubt, any previously published writing on Mahler?

This depends on one’s perspective. Some will conclude that Bauer-Lechner’s romantic interludes with the composer precluded any objectivity in her recollections of him and that her accounts must therefore be called into question. Others will point out that Bauer-Lechner’s diaries include much factual information corroborated by many other sources and that there is little reason to doubt the authenticity of her “Mahleriana” as a whole; indeed, her degree of objectivity is all the more remarkable given her emotional involvement. For discretion’s sake she declined to reveal the extent of her intimacy with Mahler in the pages of her diary that she intended to publish. But that Bauer-Lechner manipulated or fabricated information seems a contrived conclusion; that she was unable to avoid a certain partiality or missed certain details should hardly strike us as surprising.

Does the letter pose any new questions for future Mahler scholars?

The most imposing and immediate challenge that emerges from this letter is the need to collate all extant materials that Natalie Bauer-Lechner produced in her lifetime in connection with Gustav Mahler. The present authors are in the midst of precisely this project in an attempt to present the most complete account possible. This will facilitate a better informed evaluation of the value of her narrative, the extent of its objectivity, its shortcomings, and no doubt more information regarding Mahler. In particular, the content of the letter clearly indicates the need to reevaluate Alma Mahler’s claim that at the time of their marriage, Mahler “was extremely puritanical” and “had lived the life of an ascetic.”

Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling are the authors of “Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women: A Newly Discovered Document” in The Musical Quarterly. Morten Solvik is the Center Director of the International Education of Students (IES) Abroad Vienna where he also teaches music history. Stephen E. Hefling is a Professor of Music at Case Western Reserve University.

The Musical Quarterly, founded in 1915 by Oscar Sonneck, has long been cited as the premier scholarly musical journal in the United States. Over the years it has published the writings of many important composers and musicologists, including Aaron Copland, Arnold Schoenberg, Marc Blitzstein, Henry Cowell, and Camille Saint-Saens. The journal focuses on the merging areas in scholarship where much of the challenging new work in the study of music is being produced.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post New questions about Gustav Mahler appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityInvesting for feline futuresMusic parenting’s unexpected, positive benefits

Related StoriesHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityInvesting for feline futuresMusic parenting’s unexpected, positive benefits

Historical memory, woman suffrage, and Alice Paul

I saw a t-shirt the other day which brilliantly illustrated the ever-present contest over historical memory in America. The t-shirt featured the famous 1886 image of Geronimo with a few of his Apache followers, all holding weapons. The legend on the t-shirt? “HOMELAND SECURITY: Fighting Terrorism Since 1492.”

History depends on who’s telling the story. Winston Churchill once said, “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it myself.” Men have so dominated past histories that some feminist scholars suggest the term itself is suspect, that we need more “herstory.” Competing narratives are part and parcel of any country’s recording of its own history and struggles for dominance by elites vs. laypeople, dominant groups vs. minority groups are commonplace. In America, alternative versions of history have achieved increasing levels of prominence since the 1960s, as one social movement after another emerged. As the country’s mood shifted, perceptions of its past were re-examined. The “culture wars” generated discord into the 21st century. In the last twenty years, historians have grown particularly interested in documenting the transformation of both scholarly and public memory.

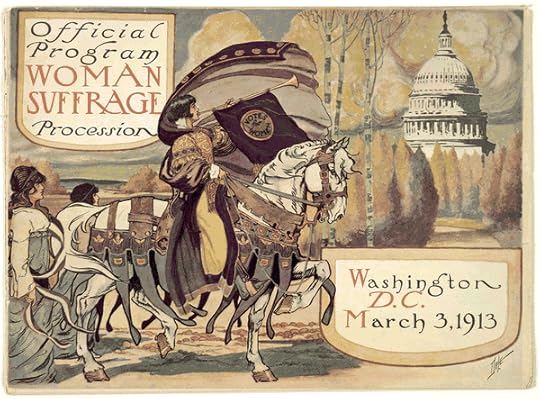

On 3 March 2013, we celebrated the centennial of the great 1913 woman suffrage procession in Washington, DC. The parade vaulted the votes-for-women cause to national prominence, thanks to the skill of its young organizer, Alice Paul, and the violence which marked the actual event. When police proved inadequate to protect the line of march, an aggressive crowd of spectators pushed, pulled, and roughed up suffragists. Most marchers soldiered on through the tumult, insisting on the right to display their desire to be accorded the most fundamental right of American citizenship: the right to consent to their government by voting. After the parade, suffragists put pressure on Congress to hold the miscreants responsible. The subsequent Senate hearing into the parade turmoil kept the suffrage cause in the spotlight for another month.

Official program – Woman suffrage procession, Washington, D.C. March 3, 1913. Library of Congress.

The procession was a landmark event in 1913, but time has further elevated its importance. The parade became the first successful national political demonstration down that quintessential corridor of American power, Pennsylvania Avenue. One earlier attempt at political protest, the 1894 “Coxey’s Army,” was seen as an assault on the capital and marchers were arrested. In the twenty-first century, organizations regularly use Pennsylvania Avenue and the Capitol mall as a site for political protest, few recognizing the brave women who first claimed full citizenship rights on the same thoroughfare in 1913.

The grand procession became a shining memory for suffragists. The experience of marching—or even reading about marching—inspired many women to give more of themselves to the drive to win the vote. It made them feel part of a feminist political community. Within a year after the procession, the suffrage movement split into militant and mainstream factions. Alice Paul was at the heart—some would say was the cause—of the rupture among activists. Her National Woman’s Party (NWP), numbering in the tens of thousands, hastened victory with spectacular political protests. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), boasting nearly a million members by the last years of the suffrage struggle, never agreed with the NWP’s unwomanly efforts. After women won the vote in 1920, they looked back on the parade as a time before differences among suffragists drove them apart.

The memoirs and histories of the woman suffrage movement appearing after 1920 mostly ignored the divisions in the movement. Alice Paul declined to write her own memoir but masterminded the first published suffrage histories. Jailed for Freedom by Doris Stevens, appeared in September 1920, a mere month after the 19th Amendment became the law of the land. A more comprehensive account of the NWP by Inez Haynes Irwin came out in 1921. Both books were received well but left in the dust when, in 1922, Ida Husted Harper published the final volume of the massive History of Woman Suffrage (HWS), work begun in the 19th century by Susan B. Anthony. This allegedly comprehensive account, together with NAWSA leader Carrie Chapman Catt’s memoir with Nettie Schuler, Woman Suffrage and Politics (C. Scribner’s, 1923), became the pre-eminent source of record on the woman suffrage movement. Neither the NAWSA nor the NWP accounts credited the other with much influence in the movement. But the size of the NWP, once advantageous for targeted protests, left it fewer defenders as well as a smaller book-buying audience.

Alice Paul would have the last laugh. She outlived other woman suffrage leaders and, as another women’s movement gathered strength in the early 1970s, she became a living link to the first wave of feminist activism. The Equal Rights Amendment, which she had authored in 1923 and promoted for decades, was taken up by the new generation. They carried banners proclaiming “Alice Paul, We’re Here” on ERA marches which themselves echoed the 1913 suffrage parade.

Alice Paul. Photo by Harris & Ewing. Library of Congress.

As modern activists and historians unearthed women’s history for themselves, Alice Paul’s brand of spectacular politics appealed to many, particularly those also already drawn into social protest by civil rights and anti-war demonstrations. It is no accident, then, that Paul’s historical reputation began to improve in the 1970s.

Eleanor Flexner’s Century of Struggle (1959) was the first sign of a revival of interest in the history of women. Flexner acknowledged the contributions of both NWP and NAWSA to the eventual suffrage victory, though she made clear her preferences for NAWSA’s methods.

By the early 1970s, a growing interest among the new generation’s scholars in Paul and the NWP generated fresh accounts of suffrage activism, both print and oral histories. The person who once seemed a dangerous force was reborn by historians as a charismatic, courageous leader. An increasing number of dissertations on the NWP gave rise to journal articles like Sidney R. Bland’s “New Life in an Old Movement: the Great Suffrage Parade of 1913 in Washington, D.C.,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society (1971), 657-78. Christine Lunardini’s From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights was the first dissertation published in book form, followed by Linda Ford’s Iron-Jawed Angels. Ford’s analysis of NWP militancy in particular embraced Paul’s assertive tactics as legitimate political strategy.

Also in the early 1970s, the Bancroft Library’s Regional Oral History Office recognized that suffrage activists were literally a dying breed. Alice Paul was among the surviving women who agreed to record lengthy oral histories for the Suffragists Oral History Project.

The public memory of Alice Paul was not erased by her death. A few years later, feminists in her home state took up the cause of her legacy. Members of the Alice Paul chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW) learned that Paul’s personal effects were to be auctioned by her sole heir, a nephew. The NOW women, led by Barbara Haney Irvine, formed the Alice Paul Centennial Foundation to raise the money to purchase Paul’s estate for deposit in the Smithsonian Institution and Boston’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women. They succeeded and several years later purchased the Paul family home in Mount Laurel, New Jersey. The Alice Paul Institute now operates as a center to preserve Paul’s historical memory and promote women’s leadership.

In 2004, the visibility of Alice Paul’s public memory reached new heights with the broadcast on HBO of the docudrama, Iron-Jawed Angels. Though many historians winced at certain popularizations, the film reached many people who knew little about the struggle for the vote or the leadership of Alice Paul. This visual recreation of women protesting and being imprisoned because they wanted to vote resonated enough to inspire continuing sales of the DVD and new viewings of the HBO drama as a means for feminist institutions to raise money.

As the centennial of the suffrage victory approaches in 2020, I expect to see more evidence that the memory of Alice Paul and the woman suffrage movement is contested territory. But that is the nature of historical memory.

J.D. Zahniser is an independent scholar. She holds a doctorate in American and Women’s Studies. She is the co-author of Alice Paul: Claiming Power with Amelia R. Fry, an oral historian at Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Historical memory, woman suffrage, and Alice Paul appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesNot learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia agoObama’s predicament in his final years as PresidentMusic parenting’s unexpected, positive benefits

Related StoriesNot learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia agoObama’s predicament in his final years as PresidentMusic parenting’s unexpected, positive benefits

Music parenting’s unexpected, positive benefits

When parents sign up kids for music lessons, probably first on the list of anticipated outcomes is that their youngsters’ lives will be enhanced and enriched by their involvement with music, possibly even leading to a lifelong love of music, whether the youngsters become performers (pro or amateur), teachers, or simply enthusiastic listeners, concert-goers, and music downloaders. Another perk that many parents may be counting on is the joy that they imagine they’ll feel while watching sons and daughters perform, whether at rough-edged but enthusiastic elementary school concerts or, later on, at more polished teen presentations. The soft glow of parental pride can help make the hard work of raising musical youngsters seem worthwhile, from the expense of music lessons to all the encouraging (and sometimes nagging) that’s required to nudge kids to practice, get to rehearsals on time, and not forget to bring their sheet music to all-county tryouts.

However, there can also be some pleasant surprises that a music parent may never have imagined would occur, according to parents I interviewed on the ups and downs of music parenting.

However, there can also be some pleasant surprises that a music parent may never have imagined would occur, according to parents I interviewed on the ups and downs of music parenting.

A broadening of musical horizons: It has “opened up a vast new world of music for us…. styles and composers that we weren’t [familiar with] before,” says Peter Maloney, father of two youngsters who take lessons in multiple instruments at a New Jersey community music school. “Our lives include so much music every day — the most wonderful experiences imaginable.” Jackie Yarmo, whose kids studied at a New Jersey School of Rock, agrees, “Our kids bring new music into the house that we haven’t heard and end up loving.”

A rekindled flame — or a new venture: Several parents pulled out old instrument cases they hadn’t opened in years and began practicing again. Or they sat down at the family piano and began picking out tunes they used to play before quitting lessons years earlier. Others joined a community choir — all because they saw how much fun their kids were having making music. “I hadn’t played my horn for almost twenty years,” says Kristin Bond, a Maine mom who bravely joined an ensemble at her church. “I started again, really awful at first, but it was good for my girls to see adults performing, some proficient and others less so. They see there’s a place for every level of ability to enjoy music.” Massachusetts mom Heather MacShane adds, “My daughter, who plays flute, convinced me to start flute lessons. I love it.”

A hedge against the dreaded empty-nest syndrome: “I knew I’d have an empty nest soon. I’ve been getting a running start preparing for it,” says Thanh Huynh. She began piano lessons again when her daughters were teenagers, hoping to become good enough in a few years to join a jazz ensemble at the Baltimore medical center where she was working. Cindy Buhse, who began playing viola again when her violist daughter was in middle school, joined a Missouri community orchestra when her daughter headed off to college, using an old viola her daughter left behind. “I go to orchestra once a week and have a good time,” she says. “It definitely helps with the empty nest.”

A way to connect: “Music can be a way to understand your child at times when they may otherwise be uncommunicative. I can tell when my teenager is unhappy by what she plays when she may not want to talk about it,” notes Ms. Yarmo. Kyle Todd, a Massachusetts father of two young adults who are pursuing nonmusical careers, says that music still remains “something that we hold in common. It continues to provide us with activities for shared experiences.”

Kids can also experience unexpected, positive benefits from immersing themselves in music, including some that are nonmusical in nature. More on that later.

Amy Nathan is an award-winning author of several books on music including The Music Parents’ Survival Guide: A Parent-to-Parent Conversation, and two earlier books for young people, The Young Musician’s Survival Guide: Tips From Teens and Pros, and Meet the Musicians: From Prodigy (or Not) to Pro. A Harvard graduate with master’s degrees from the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Columbia’s Teacher’s College, she is the mother of two musical sons: one a composer and the other a saxophone-playing political science graduate student. Read her previous OUPblog post.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A young Asian woman with her clarinet. Photo by tmarvin, iStockphoto.

The post Music parenting’s unexpected, positive benefits appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn Great ExpectationsNot learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia agoFixing the world after Iraq

Related StoriesOn Great ExpectationsNot learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia agoFixing the world after Iraq

Class arbitration at home and abroad

To paraphrase the Bard, the course of class arbitration never did run smooth. Ever since its inception in the early 1980s and 1990s, the development of class arbitration has been both complicated and controversial. For example, in 2003, the US Supreme Court decision in Green Tree Financial Corp. v. Bazzle, was read as providing implicit approval of class arbitration and resulted in the massive expansion of the procedure across the country. Seven years later, the Court took the opposite tack and decided to curtail the procedure with its opinion in Stolt-Nielsen S.A. v. Animal Feeds International Corp., which was followed by equally problematic decisions in AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, Oxford Health Plans LLC v. Sutter, and American Express Co. v. Italian Colors Restaurant.

One result of the Supreme Court’s recent activity has been the diminution in the number of class arbitrations that are being filed with arbitral institutions. However, the Court’s decisions have done little to silence either the policy debates or the litigation surrounding class arbitration. Indeed, approximately 80 federal court opinions and 40 state court opinions have been rendered on this subject in the last 12 months alone, which suggests that the United States’s struggle with large-scale arbitration is far from over.

Most observers recognize that the debate about class arbitration in the United States is closely tied to concerns about judicial class actions. However, other countries are beginning to expand the number and type of mechanisms used to provide relief for large-scale legal injuries at precisely the same time that the United States is pulling back from class actions and arbitrations. These other legal systems have created a variety of means of addressing mass injuries, including several types of large-scale arbitration. Furthermore, efforts to adopt large-scale arbitration in other jurisdictions typically do not generate the same type of animosity and opposition that is seen in the United States. This phenomenon suggests that there is much that the United States can learn by studying the mechanisms used in these other legal systems.

One jurisdiction that has come out strongly in favor of large-scale arbitration is Brazil, which has created a constitutional right to large-scale arbitration in labor disputes. The Brazilian legislature is also currently contemplating a bill (No. 5139/2009) that would extend the right to large-scale arbitration to other types of mass legal disputes. In many ways, Brazilian acceptance of class and collective arbitration is unsurprising, since Brazil also embraces various types of large-scale litigation. However, US courts and policymakers could find it useful to consider the way in which Brazil differentiates between matters that are appropriate for court and matters that are appropriate for arbitration, since some of these analyses may also be relevant in the United States.

Spain also provides for large-scale arbitration, although the Spanish procedure is statutory rather than constitutional in nature. The Spanish approach involves a non-representative collective procedure that addresses many of the concerns commonly enunciated by respondents, particularly with respect to the issue of consent. Because the Spanish statute on collective arbitration is limited to consumer disputes, the legislature was able to tailor the mechanism narrowly to suit the needs of the participants. This type of subject-specific approach could prove instructive to those in the United States who are concerned about the problems associated with a trans-substantive procedure or with questions of consent.

Some commentators have suggested that class arbitration in the United States has experienced difficulties because the procedure was created through non-democratic (i.e. judicial) means rather than through legislative measures. This theory would discount the usefulness of the Brazilian and Spanish procedures because they were implemented through democratic processes. However, other countries have adopted large-scale arbitration through judicial action and have nevertheless avoided the kinds of ongoing difficulties seen in the United States.

The Republic of Colombia was the first jurisdiction outside the United States to adopt large-scale arbitration through judicial means. Both the Supreme Court of Justice and the Constitutional Court have suggested that class claims are arbitrable, and at least one arbitral tribunal is known to have rendered an award in a group action. Although other jurisdictions, most notably Canada, have declined to adopt class arbitration through judicial means, Colombia’s acceptance of class arbitration suggests that the United States is not an outlier in terms of the way in which class arbitration has developed.

This conclusion is borne out by the fact that several other legal systems have authorized large-scale arbitration through judicial measures. For example, the German Federal Court of Justice authorized arbitration of shareholder disputes in 2009, after having decided against doing so in 1996. The earlier decision was based on the belief that the legislature should be the one to determine whether these types of issues were arbitrable. However, when the democratically elected officials failed to take action one way or another, the judicial branch decided to step in. As a result of the 2009 decision, the German Institution of Arbitration (DIS) created its Supplementary Rules for Corporate Law Disputes (DIS-SRCoLD), which allow for a unique type of non-representative collective arbitration. Although the rules are aimed primarily at so-called “traditional” multiparty disputes (i.e., those that involve only a handful of participants), some of the procedural elements could be usefully adopted in matters involving larger numbers of parties.

Large-scale proceedings have also been adopted by arbitral tribunals acting without the guidance of a court. The most well-known example of this phenomenon was seen in the context of investment arbitration. In 2011, the arbitral tribunal in Abaclat v. Argentine Republic allowed 60,000 Italian bondholders to join together and bring their claims in a single proceeding. The resulting procedure has been characterized as “mass” arbitration rather than class arbitration, since it contains both representative and aggregative features. Although no other mass arbitration has yet been seen in the investment realm, the award in Abaclat was cited with approval by the tribunal in Ambiente Ufficio v. Argentine Republic, which involved ninety claimants.

As the preceding suggests, large-scale arbitration takes many forms and arises in many different ways. Although the US Supreme Court has attempted to curtail one particular mechanism (class arbitration), there are a multitude of other means of allowing large numbers of similarly-situated parties to join together to assert their claims. Indeed, parties in the United States have already begun to experiment with various types of non-class arbitration. For example, some parties have successfully brought large-scale, non-representative (collective) arbitrations, while other parties have resorted to filing large numbers of bilateral arbitrations simultaneously so as to drive respondents to the settlement table. These techniques underscore the need for scholars, policy-makers and practitioners to continue to debate and discuss the various issues relating to large-scale arbitration in the United States. In so doing, a comparative analysis would be beneficial, since the best solution to these problems may be found in procedures developed in other jurisdictions.

S.I. Strong is Associate Professor of Law at the University of Missouri School of Law. She is the author of Class, Mass, and Collective Arbitration in National and International Law and Research and Practice in International Commercial Arbitration: Sources and Strategies .

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Austria – Göttweig Abbey. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Class arbitration at home and abroad appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityWorld Refugee Day Reading ListImportance of venue selection in international arbitration

Related StoriesHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityWorld Refugee Day Reading ListImportance of venue selection in international arbitration

June 23, 2014

On Great Expectations

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 24 June 2014, Maura Kelly, author of Much Ado About Loving, leads a discussion on Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations.

By Maura Kelly

Great Expectations is arguably Charles Dickens’s finest novel – it has a more cogent, concise plot and a more authentic narrator than the other contender for that title, the sprawling masterpiece Bleak House. It may also enjoy another special distinction – Best Title for Any Novel Ever. Certainly, it might have served as the name for any of Dickens’s other novels, as the critic G. K. Chesterson has noted before me. “All of his books are full of an airy and yet ardent expectation of everything … of the next event, of the next ecstasy; of the next fulfillment of any eager human fancy,” wrote Chesterson. What’s more, it might have been used for a number of the best novels written by any author – American novels in particular. Think of The Great Gatsby, Absalom, Absalom, Invisible Man, or Revolutionary Road. The same goes for Saul Bellow’s short tour de force, Seize the Day, or that of Henry James, The Beast in the Jungle. But think too of Balzac’s novel Lost Illusions, nearly a synonym for Dickens’s phrase, or another French book, Madame Bovary. Think of all the works of Jane Austen, with the various expectations that so many characters in every one of her books have about who should marry whom. And on and on.

But think too of most life stories, most personal narratives: Might they not also be called Great Expectations? For what are our lives but our attempts to realize our dreams about what we might become, and to either castigate or console ourselves if we don’t?

Miss Havisham, Pip, and Estella, in art from the Imperial Edition of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. Art by H. M. Brock. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In Pip, the hero of Great Expectations, we have a character who is something of a combination of a Gatsby and an Austen heroine. He is fixated on attaining romantic union that will, he believes, quiet his persistent feelings of self-loathing and inadequacy; he is also all too painfully aware that he is not of the right class to attract that person. As a youth, Pip feverishly hopes that he will miraculously come into money so that he might win the heart of his Daisy – the beautiful, haughty, wealthy Estella. If Pip were a character living in America, he might have done more than dream about getting rich quick – he might have gone the Gatsby route, or the route of any number of Horatio Alger protagonists. However, living in England as he does – where for centuries, people were either born into the aristocracy or they weren’t – Pip doesn’t do much more than fantasize. Nonetheless, thanks to the magic of Dickens’s narrative, through a turn of fate that seems quite plausible in the world of the novel, into money Pip does mysteriously come. And yet, despite his newfound wealth and status, he can’t “get the girl” – the girl who is not simply the person with the power to cure Pip of his terrible sickness of the soul, but the very same girl who inflicted him with that psychological malady when she disdained Pip as a child, calling him “coarse” and “common” and generally making it clear that she thought him beneath her.One more story that might have been called Great Expectations is that of Elliot Rodger, the young man with a BMW, a closet full not of silk shirts but Armani sweaters, and a trove of guns who killed six college students during a shooting spree in California a couple of weeks ago. Judging from the manifesto he left behind, he did not get the girls; he was scorned by beautiful women; his life had fallen woefully short of his expectations. Who can say just how that troubled young man developed his expectations, but he was what you might call a spawn by Hollywood; his parents met on a movie set, after all. And if there is any city in the world that might be called the city of Great Expectations, Los Angeles has to be it, where the world’s most visible examples of glamorous, glittering success serve as foils to some of the most desperate characters around – the red-eyed and unhinged hopefuls who have been hanging around for years or decades, hoping for the big break that never comes.

Rodger’s father seems to have had experiences on both ends of the success spectrum: Though he directed some extra shots for “The Hunger Games,” he also spent $200,000 of his own money on a documentary that sold only a “handful of tickets,” according to The New York Times. Rodger seems to have resented his father: “If only my failure of a father had made better decisions with his directing career instead wasting his money on that stupid documentary,” he wrote. And Pip, too, resents his multiple father figures – at first, at least. But unlike Rodger, Pip works through his resentment, and in doing so, finds his redemption.

When Pip’s biological father dies, he is adopted by his sister’s humble husband, the kindly if simple blacksmith Joe Gargery. Though Joe serves as the main source of comfort, happiness, and stability in Pip’s young life, when Estella infects Pip with shame, he becomes ashamed of Joe, too; thinking him too much a country bumpkin, Pip distances himself from Joe. He reacts in a similar way to the other father figure of the novel, Abel Magwitch. A good-hearted criminal, Magwitch bestows an honest fortune on the adult Pip out of gratitude for some help that a frightened young Pip had given him during an escape attempt he made years ago. Pip more or less recoils in horror when Magwitch explains that he’s the one who’s been funding Pip’s life as a gentleman. But Pip eventually pushes his through his feelings of mortification and revulsion in order to do the right thing. He repays Magwitch’s loving kindness with some loving kindness of his own, by helping the old convict attempt to evade capture after he returns to England despite threat of death, because he so much wants to see Pip.

Pip’s overcoming his lesser self in this way “is not a simple recovery from snobbery, but courage of a rare and fine kind,” according to critic A. E. Dyson. Scholar Sylvere Monod writes that the only reason Pip is able to propel himself to such courage is because he has been on a “groping quest … for the truth, not only about the world and the society among which he lives, but also, and more importantly, about himself.” That quest is what allows him to come to a greater acceptance of both himself, at the end of the novel, and his two adoptive fathers – men who, for all their lack of societal cache, have always done for Pip something that neither Estella nor Pip himself were able to: love Pip more or less unconditionally.

“Poor, miserable, fellow creature” : it is a phrase often repeated by humble Joe Gargery, and it helps to point to the lessons about empathy and acceptance that Pip must learn. While it likely would not have been possible for someone like Elliot Rodger to have derived much from Great Expectations, plenty of other readers – like this one – can continue to rely on it as a source of wisdom and comfort, as an inspiration for humility and a font of hilarity, as we grapple with our own feelings of doubt and worthlessness, with the disparity between our own great expectations and the disappointing realities of our lives. “This is the Dickens novel the mature and exigent are now likely to re-read most often and to find more and more in each time,” wrote British literary critic Q. D. Leavis in 1970, “perhaps because it seems to have more relevance outside its own age than any other of Dickens’s creative work.” That is as true now as it was when Great Expectations first appeared in serial form in 1860.

Maura Kelly writes personal essays, profiles and op-eds. Her new book, Much Ado About Loving: What Our Favorite Novels Can Teach You About Date Expectations, Not-So-Great Gatsbys and Love in the Time of Internet Personals, is a hybrid of memoir, lit crit and advice column. She graduated from Dartmouth College and received her MFA in fiction writing from George Mason University. She started her career with jobs at The Washington Post and Slate. She has been a staff writer for Glamour, a daily dating blogger for Marie Claire and a relationships columnist for amNew York. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Daily Beast, The Daily, The New York Observer, Salon, The Guardian, The Boston Globe Magazine, Rolling Stone, More and other publications and anthologies.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook. Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post On Great Expectations appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow much do you know about The Three Musketeers ?Not learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia agoFixing the world after Iraq

Related StoriesHow much do you know about The Three Musketeers ?Not learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia agoFixing the world after Iraq

Not learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia ago

Recent events in Iraq, as the militant group ISIS (or ISIL) strives to establish an Islamic state in the country that threatens to undo everything that western involvement achieved there after 9/11, illustrates well the volatility of the entire region and the interplay of religion and politics. Sunnis who felt cast aside to the periphery of political affairs by the Shiite government are rallying to ISIS. American-trained Iraqi forces (at a cost of several billions of dollars) have proved ineffectual, and who knows if the Iraqi government could fall, and what the country will look like — and be doing — in a year’s or even a matter of months’ time.

For well over a decade we have witnessed Western involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan, ostensibly to benefit the wellbeing of the native peoples and in the case of Iraq, to stamp out the exploitive and murderous dictatorship of Saddam Hussein. The result was going to be the introduction of democracy for an oppressed nation; the diverse factions and different religious faiths would unite, and ties with the West would thus enter a new (and grateful) phase. But the Iraqi war that Dick Cheney confidently asserted would take only six weeks and certainly not more than six months took far longer than that and cost an inexcusable number of lives. And the strategies to what might be called nation building failed miserably. The last few weeks are proving that. The campaign in Afghanistan likewise hasn’t met its objectives. Taliban influence remains strong and even growing, and as the death count for military and civilian personnel bloodily grew, people realized Afghanistan was the unwinnable war. So the question is inevitable: will Afghanistan go the way of Iraq as well?

There is a lot to be said for the phrase “history repeats itself,” and a lot of lessons to be learned from history. Although analogies have sometimes been made to the earlier and unsuccessful British and Russian involvement in Afghanistan, Alexander the Great’s campaigns in the former Persian Empire and Central Asia over two millennia ago need to be studied more. He was the first western conqueror in the east, and the problems he faced in dealing with a diverse subject population and the strategies he took to what might be called nation building shed light on contemporary events in culturally dissimilar regions of today’s world.

The Macedonian empire of the later fourth century BC was the largest empire in antiquity before the Roman, stretching from Greece to India (present-day Pakistan) including Syria, the Levantine coast, and Egypt. Yet it took less than 40 years to form thanks to Philip II of Macedonia and especially his son Alexander (the Great). Alexander’s conquests in Asia opened up economic and cultural contacts, spread Greek culture, and made the Greeks aware that they were part of a world far bigger than the Mediterranean. When Alexander crossed the Hellespont in spring 334 and landed on Asian soil he had a clear strategy in mind: to replace the Persian Empire with one of his own. A decade later in some spectacular battles and sieges against numerically greater foes, he had done just that. In 323 he was all set to invade Arabia when he died, just short of his 33rd birthday, at Babylon.

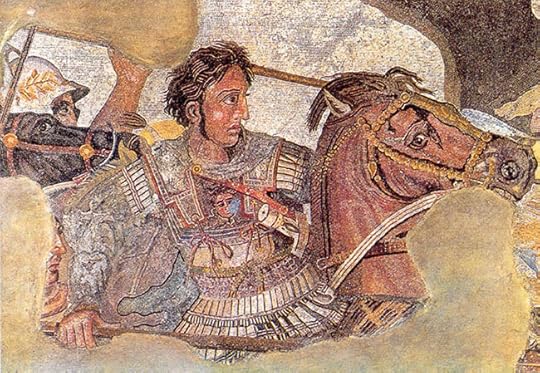

Detail of the Alexander Mosaic, representing Alexander the Great on his horse. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But as Alexander discovered to his detriment, and as makers of modern strategy know all too well, defeated in battle doesn’t mean conquered. Moreover, he hadn’t anticipated how he was going to rule a large and culturally diverse subject population, whose religious beliefs and social customs weren’t always understood by the invaders and even disregarded. When the last Great King of Persia, Darius III, was murdered, Alexander faced a dilemma: how to rule? There had never been a Macedonian king who was also ruler of Persia before. Alexander had to learn what to do on his feet, without a rulebook or foreign policy experts.

He couldn’t proclaim himself Great King as that would create stiff opposition from his men, who wanted only a traditional Macedonian warrior king. So he opted for a new title, King of Asia, and even a new style of dress, a combination of Macedonian and Persian clothing. In doing so he pleased no one — his men thought he had gone too far and the Persians not enough. Alexander also didn’t grasp — or didn’t bother about — the personal connection between the Zoroastrian God of Light, Ahura Mazda, and the Great Kings, whose right to rule was anchored in that connection. The religious significance of the great Persian palace centers were disregarded by the westerners, who saw them only as seats of power and home to vast treasuries. Then in what is now Afghanistan, Alexander banned the Bactrians’ custom of putting out their elderly and infirm to be eaten alive by dogs kept for this purpose. A barbaric practice to us, for sure, but another instance of high-handedness and imposition of western morality in a foreign land.

It is little wonder that Alexander was always seen as the invader, that his attempts to integrate his various subject peoples into his army and administration failed, and that “conquered” areas such as India and Afghanistan revolted as soon as he left so they could go back to how things used to be. Unwinnable wars indeed, then and now. Alexander’s dilemma of West meeting East set a pattern for history. He unashamedly set out to rule a great empire by force, and failed. Today, the West might embroil itself elsewhere to help spread democracy, but those best intentions can fall apart without understanding the peoples with whom you’re dealing. The problems Alexander faced in dealing with a multi-cultural subject population arguably can inform makers of strategy in culturally different regions of today’s world. But at the end of the day politics and religion are so tightly interwoven and misunderstood, and animosity towards the invader, be it Alexander then or the West now, so great, that for anyone from the West to talk of imposing stability and a new order is hubris. Iraq now is proving that, no different from the Persian Empire to outside rule two millennia ago.

Ian Worthington is Curators’ Professor of History and Adjunct Professor of Classical Studies at the University of Missouri. He is the author of numerous books about ancient Greece, including Demosthenes of Athens and the Fall of Classical Greece and By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Not learning from history: unwinnable wars and nation building, two millennia ago appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire in picturesObama’s predicament in his final years as PresidentFixing the world after Iraq

Related StoriesThe rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire in picturesObama’s predicament in his final years as PresidentFixing the world after Iraq

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers