Oxford University Press's Blog, page 794

July 2, 2014

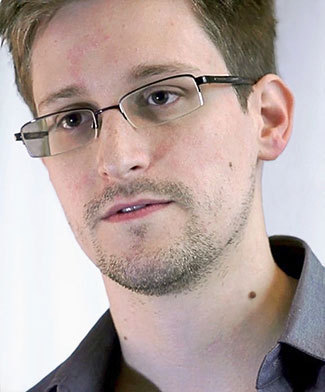

For social good, for political interest: the case of Edward Snowden

When Edward Snowden obtained documents as an employee of Booz Allen Hamilton and made them public, the information disclosed was covered by secrecy under US law. That obligation was part of his employment contract, and such disclosure constituted a crime.

He first disclosed this material to Glenn Greenwald of The Guardian in early June of 2013. On 14 June, the Department of Justice filed a complaint against Snowden, charging him with unauthorized disclosure of national defense information under the 1917 Espionage Act, unauthorized disclosure of classified communication intelligence, and theft of government property.

He first disclosed this material to Glenn Greenwald of The Guardian in early June of 2013. On 14 June, the Department of Justice filed a complaint against Snowden, charging him with unauthorized disclosure of national defense information under the 1917 Espionage Act, unauthorized disclosure of classified communication intelligence, and theft of government property.

Snowden made these disclosures while in Hong Kong, and it is reported that the United States sought his extradition pursuant to the treaty it has with Hong Kong, which contains a provision for the exclusion of political offenses. This brings into question the nature of Snowden’s offence.

The Snowden case is inherently simple, and comes down to whether Snowden’s actions were politically motivated or based on social interest. There was no harm to human life, and there was no general social harm. On the contrary, it revealed abuses of secret practices that violate the constitutional right of privacy. Harm to the “national security” is not only subjective but it is also dependent upon who decides what is and what is not part of “national security.”

When it comes to extradition, both the nature of the crime and the motive of the requesting state are taken into account. If the crime for which the person is requested is of a political nature and there is no human or social harm, extradition may be denied on the grounds that it is a purely political offense. This theory is extended to what is called the “relative political offense exception,” when, as incidental to a “purely political offense exception” an unintended social harm results. For example, if someone exercises freedom of speech by speaking loudly in the middle of a square and is charged with disturbing the peace, flees the country, and is sought for extradition, that is a purely political offense exception. If, in the course of fleeing the park they accidentally knock over an aged person who is injured and the state charges him with assault and battery, which would be a relative political offense exception. But the fact that Snowden himself maintains that he did not make public any information that could put intelligence officers in harm’s way, or reveal sources to foreign rivals of the United States means that under extradition law, his case is purely political.

Almost all states allow for the purely political offense exception to apply. Those that do not, bypass the exception for political reasons. This explains why Snowden went to Russia, though the UK would have found it difficult to extradite him too. It helps to look back to the case of Julian Assange, who was sought by the United States when in the UK. When the UK could not extradite Assange because of the purely political offense exception doctrine, the United States had Sweden seek his extradition from the UK for what was a criminal investigation into a common crime (sexual assault). This is what led Assange to seek refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy.

The fact that the purely political offence exception doctrine arose with respect to the Snowden case, assuming it would be the subject of extradition proceedings, is curious to say the least. Would a government official of, say, the Comoros Islands be the subject of similar international attention for the disclosure of some secret skullduggery that the government had classified as top secret? The answer is of course no. What makes this case a cause célèbre is that it has to do with the United States, because it embarrasses the United States, and because it reveals that the government of the United States and at least one of its most important agencies (the NSA) has engaged in violations of the Constitution and laws on the protection of individual privacy. It has shown abuses of the powers by the executive branch to obtain information from private sector companies, which would not be otherwise obtainable without a proper court order. This of course is what makes the Snowden case so extraordinary since it is about a US citizen doing what he believed was right to better serve his country and whose very government was violating its constitution and laws.

M. Cherif Bassiouni is Emeritus Professor of Law at DePaul University where he taught from 1964-2012, where he was a founding member of the International Human Rights Law Institute (established in 1990), and served as President from 1990-2007, and then President Emeritus. He is also President, International Institute of Higher Studies in Criminal Sciences, Siracusa, Italy since 1989. He is the author of International Extradition: United States Law and Practice, Sixth Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Screenshot of Edward Snowden by Laura Poitras/Praxis Films. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post For social good, for political interest: the case of Edward Snowden appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?Sovereign debt in the light of eternityMargot Asquith’s Great War diary

Related StoriesIs Amanda Knox extraditable from the United States to Italy?Sovereign debt in the light of eternityMargot Asquith’s Great War diary

The danger of ideology

By Richard S. Grossman

What do the Irish famine and the euro crisis have in common?

The famine, which afflicted Ireland during 1845-1852, was a humanitarian tragedy of massive proportions. It left roughly one million people—or about 12 percent of Ireland’s population—dead and led an even larger number to emigrate.

The euro crisis, which erupted during the autumn of 2009, has resulted in a virtual standstill in economic growth throughout the Eurozone in the years since then. The crisis has resulted in widespread discontent in countries undergoing severe austerity and in those where taxpayers feel burdened by the fiscal irresponsibility of their Eurozone partners.

Despite these widely differing circumstances, these crises have an important element in common: both were caused by economic policies that were motivated by ideology rather than cold hard economic analysis.

The Irish famine came about when the infestation of a fungus, Phythophthora infestans, led to the decimation of the potato crop. Because the Irish relied so heavily on potatoes for food, this had a devastating effect on the population.

At the time of the famine, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. Britain’s Conservative government of the time, led by Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, swiftly undertook several measures aimed at alleviating the crisis, including arranging a large shipment of grain from the United States in order to offer temporary relief to those starving in Ireland.

More importantly, Peel engineered a repeal of the Corn Laws, a set of tariffs that kept grain prices high. Because the Corn Laws benefitted Britain’s landed aristocracy—an important constituency of the Conservative Party, Peel soon lost his job and was replaced as prime minister by the Liberal Party’s Lord John Russell.

Russell and his Liberal Party colleagues were committed to an ideology that opposed any and all government intervention in markets. Although the Liberals had supported the repeal of the Corn Laws, they opposed any other measures that might have alleviated the crisis. Writing of Peel’s decision to import grain, Russell wrote: “It must be thoroughly understood that we cannot feed the people. It was a cruel delusion to pretend to do so.”

Contemporaries and historians have judged Russell’s blind adherence to economic orthodoxy harshly. One of the many coroner’s inquests that followed a famine death recommended that a charge of willful murder be brought against Russell for his refusal to intervene in the famine.

The euro was similarly the result of an ideologically based policy that was not supported by economic analysis.

In the aftermath of two world wars, many statesmen called for closer political and economic ties within Europe, including Winston Churchill, French premiers Edouard Herriot and Aristide Briand, and German statesmen Gustav Stresemann and Konrad Adenauer.

The post-World War II response to this desire for greater European unity was the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Economic Community, and eventually, the European Union each of which brought increasingly closer economic ties between member countries.

By the 1990s, European leaders had decided that the time was right for a monetary union and, with the Treaty of Maastricht (1993), committed themselves to the establishment of the euro by the end of the decade.

The leap from greater trade and commercial integration to a monetary union was based on ideological, rather than economic reasoning. Economists warned that Europe did not constitute an “optimal currency area,” suggesting that such a currency union would not be successful. The late German-American economist Rüdiger Dornbusch classified American economists as falling into one of three camps when it came to the euro: “It can’t happen. It’s a bad idea. It won’t last.”

The historical experience also suggested that monetary unions that precede political unions, such as the Latin Monetary Union (1865-1927) and the Scandinavian Monetary Union (1873-1914), were bound to fail, while those that came after political union, such as those in the United States in 18th century, Germany and Italy in the 19th century, and Germany in the 20th century were more likely to succeed. The various European Monetary System arrangements in the 1970s, none of which lasted very long, also provided evidence that European monetary unification was not likely to be smooth.

Concluding that it was a mistake to adopt the euro in the 1990s is, of course, not the same thing as recommending that the euro should be abandoned in 2014. German taxpayers have every reason to resent the cost of supporting their economically weaker—and frequently financially irresponsible—neighbors. However, Germany’s prosperity rests in large measure on its position as Europe’s most prolific exporter. Should Germany find itself outside the euro-zone, using a new, more expensive German mark, German prosperity would be endangered.

What we can say about the response to the Irish Famine and the decision to adopt the euro is that they were made for ideological, rather than economic reasons. These—and other episodes during the last 200 years—show that economic policy should never be made on the basis of economic ideology, but only on the basis of cold, hard economic analysis.

Richard S. Grossman is a Professor of economics at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, USA and a visiting scholar at Harvard University’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science. His most recent book is WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Irish potato famine, Bridget O’Donnel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Sir Robert Peel, portrait. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The danger of ideology appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesChanging focusDoes the “serving-first advantage” actually exist?Sovereign debt in the light of eternity

Related StoriesChanging focusDoes the “serving-first advantage” actually exist?Sovereign debt in the light of eternity

Do we have too much democracy?

By Matthew Flinders

It’s finally happened! After years of watching and (hopeful) waiting, tomorrow is the day that I finally step into the TEDx arena alongside an amazing array of speakers to give a short talk about ‘an idea worth spreading’. The theme is ‘Representation and Democracy’ but what can I say that has not already been said? How can I tackle a big issue in just a few minutes? How do I even try and match-up to the other speakers when they include people like the pro-democracy campaigner and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi? Dare I suggest the problem is ‘too much’ democracy rather than ‘too little’?

The ‘three-minute thesis test’ is a relatively new form of professional training in which Ph.D. students need to provide a clear and succinct account of their thesis and why it matters in just 180 seconds. The aim is to not only make the students think and focus on the core intellectual ‘hook’ of their research but also to hone their communication skills so they can talk to multiple audiences in multiple ways about their research. This is all jolly good and to be encouraged. TEDx talks, however, represent something of the ‘über-three minute thesis test’ in the sense that not only must you tackle a big issue but you must also do so in a way that is sophisticated yet accessible, entertaining but serious and thought provoking but not ridiculous. You get eight minutes to do this, not three, but you only get one shot at giving the talk in front of a large live audience and an even larger online audience of many millions. This is reputational poker. Here is the essence of my pitch.

The title of my talk is ‘The Problem with Democracy’. However, the problem with even talking about ‘the problem with democracy’ is that it is a loaded statement. Loaded in the sense that it suggests that (1) there is a single ‘problem’ when it might be argued a discussion of ‘the problems’ [plural] with democracy might offer a more rounded and sophisticated set of answers; and (2) loaded in the sense that it accepts that ‘a problem’ exists. I want to take on and challenge each of these assumptions in turn but before this I want to make the rather unfashionable – even heretical – suggestion [and this is my ‘hook’] that one of the problems with contemporary democracy might be that in some parts of the world we have too much democracy rather than too little. Let’s call this problem ‘hyper-democracy’.

Something seems to have gone wrong in the relationship between the governors and the governed. Recent elections at all levels display not only low turnouts but also a shift towards more extreme populist parties that offer a general message of anti-politics and a mantra of ‘If only we could get rid of all the terrible politicians then everything would be fine!’ The problem is that you cannot have democracy without politics and you cannot have politics without politicians.

For all sorts of reasons, politics is increasingly viewed as little more than a spectator sport or a retail activity. Yet, democratic politics is not a ‘click-and-collect’ online shopping channel where you make your choice and expect your goods to arrive. And if you don’t get what you want, it has become too easy to heckle – or should I say to tweet or blog – from the sidelines. Could it be that we have too much of the wrong kind of democracy and too little of the right kind of democracy? Democracy is about compromise and a sense of proportion. We don’t always get what we want, as individuals or specific groups, in a democracy but that’s just the price we pay for living in a free society as opposed to a fear society (this might be a good time to remind you that, as the research of Freedom House illustrates, most of the world’s population do not live in democratic regimes).

We may have hit a point where our political system has become too sensitive to the public’s opinions and anxieties. Just think about the second half of the twentieth century; the growth in the number and range of ‘sleazebusters’, watchdogs, and audit bodies, the increasing role of the courts and the judicialization of politics, not to mention the role of the internet and an increasingly aggressive media in holding political processes and politicians to account. This is all good. It’s democratic progress. It’s part of John Keane’s wonderful book The Life and Death of Democracy and he calls this stage of far greater popular controls over politicians ‘monitory democracy’. But you could call this ‘hyper-democracy’ because the 24/7 news-cycle creates a perpetual storm of scandal and intrigue.

Could it be that we need to give those politicians we elect just a little more leeway and ‘space’ in order to allow them to focus on delivering their promises? Could it be that politicians have become too sensitive to the immediate demands of the loudest sectional groups or the latest focus group or what’s trending on twitter? The reason I dare to ask this question is for the simple reason that ‘hyper-democracy’ does not seem to be producing contented democrats but disaffected democrats. It seems to be fuelling increasing mistrust and mass misrepresentation by the media.

However, on the one hand I am criticizing the public for not getting involved themselves and viewing politics as a spectator sport, but on the other hand I am emphasizing that politicians need a little breathing space. How do I square this circle in a manner that offers a solution to the problem of democracy? I do it like this: the problem with hyper-democracy is too much of a shallow, disengaged, and generally aggressive form of individualized market-democracy and too little of a deeper and more socially embedded model based on active and engaged citizenship. We need less shouting and more listening, less pessimism and more optimism, but most of all we need more people – from a broader range of backgrounds – to step into the arena in order to demonstrate just why democratic politics matters.

Matthew Flinders is Founding Director of the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics at the University of Sheffield

and also Visiting Distinguished Professor in Governance and Public Policy at Murdoch University, Western Australia. He is also Chair of the Political Studies Association of the United Kingdom and the author of Defending Politics (2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Five young people shouting into camera. © RapidEye via iStock Photo.

The post Do we have too much democracy? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLook beneath the voteMargot Asquith’s Great War diaryAfter the storm: failure, fallout, and Farage

Related StoriesLook beneath the voteMargot Asquith’s Great War diaryAfter the storm: failure, fallout, and Farage

July 1, 2014

Does the “serving-first advantage” actually exist?

Suppose you are watching a tennis match between Novak Djokovic and Rafael Nadal. The commentator says: “Djokovic serves first in the set, so he has an advantage.” Why would this be the case? Perhaps because he is then ‘always’ one game ahead, thus serving under less pressure. But does it actually influence him and, if so, how?

Now we come to the seventh game, which some consider to be the most important game in the set. But is it? Nadal serves an ace at break point down (30-40). Of course! Real champions win the big points, but they win most points on service anyway. At first, it may appear that real champions outperform on big points, but it turns out that weaker players underperform, so that it only seems that the champions outperform. And Nadal goes on to win three consecutive games. He is in a winning mood, the momentum is on his side. But does a ‘winning mood’ actually exist in tennis? (Spoiler: It does, but it is smaller than many expect.)

To figure out whether the “serving-first advantage” actually exists, we can use data on more than one thousand sets played at Wimbledon in order to calculate how often the player who served first also won the set. This statistic shows that for the men there is a slight advantage in the first set, but no advantage in the other sets.

On the contrary, in the other sets, there is actually a disadvantage: the player who serves first in the set is more likely to lose the set than to win it. This is surprising. Perhaps it is different for the women? But no, the same pattern occurs in the women’s singles.

It so happens that the player who serves first in a set (if it is not the first set) is usually the weaker player. This is so, because (a) the stronger player is more likely to win the previous set, and (b) the previous set is more likely won by serving the set out rather than by breaking serve. Therefore, the stronger player typically wins the previous set on service, so that the weaker player serves first in the next set. The weaker player is more likely to lose the current set as well, not because of a service (dis)advantage, but because he or she is the weaker player.

This example shows that we must be careful when we try to draw conclusions based on simple statistics. The fact that the player who serves first in the second and subsequent sets often loses the set is true, but this primarily concerns weaker players, while the original hypothesis includes all players. Therefore, we must control for quality differences, and statistical models enable us to do that properly. It then becomes clear that there is no advantage or disadvantage for the player who serves first in the second or subsequent sets; but it does matter in the first set, so it is wise to elect to serve after winning the toss.

Franc Klaassen is Professor of International Economics at University of Amsterdam. Jan R. Magnus is Emeritus Professor at Tilburg University and Visiting Professor of Econometrics at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. They are the co-authors of Analyzing Wimbledon: The Power of Statistics.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: “Wimbledon Centre Court Panoramic: Rafael Nadal vs Del Potro” (2011) by Rian (Ree) Saunders. CC BY 2.0 via 58996719@N07 Flickr

The post Does the “serving-first advantage” actually exist? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSovereign debt in the light of eternityThe role of communication at workThe Book of Common Prayer Quiz

Related StoriesSovereign debt in the light of eternityThe role of communication at workThe Book of Common Prayer Quiz

A Canada Day reading list

This Canada Day, we thought this would be an excellent opportunity to look back on some historical and fundamental books from the Canadian literary corpus.

Canadian Literature and Cultural Memory by Cynthia Sugars and Eleanor Ty

Explore aspects of historical remembering in Canadian literature on a range of topics from Canada’s earliest historical narratives to recent work. Essays are representative of the country’s regional character, as well as of the ongoing movement of peoples in immigration and diaspora. The book’s five parts (amnesia, postmemory, recovery work, trauma, and globalization) reflect the many ways the past infuses the present, and how the present adapts the past.

High Bright Buggy Wheels by Luella Creighton

Luella Creighton’s 1951 novel is one of the first published in Ontario to describe life inside the Mennonite community. Her characters, although from an isolated and insular world, are compelling, and details of daily life are fascinating. While Mennonites shun the aesthetic side of life, the novel accurately shows the feeling of community belonging and spiritual bonding that holds members together. The novel recounts an inquisitive young woman leaving the community to spend time in a nearby city, learning music and dressmaking. In the events that unfold, her intellectual and spiritual horizons expand, and she enters into a forbidden liaison. Ultimately, there is tragedy and eventually difficult reconciliation. In its detailing of the little-known daily life of Ontario Mennonites, Creighton’s novel is in a tradition of writers as diverse as Barbara Smucker and Miriam Toews.

Canada Day. Photo by Alejandro Mejía Greene. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via jubilo Flickr.

The Oxford Book of Canadian Verse by Wilfred Campbell

A century ago Oxford University Press published the first-ever anthology of Canadian poetry—a beautiful blue edition with gilt edges. “There are selections of verse in this volume which now appear for the first time in the pages of any Canadian anthology,” proudly writes volume editor and poet Wilfred Campbell, the first anthologist to wrestle with the question, “What is Canadian?” The result is an anthology that spans the capture of Quebec to the early twentieth century, containing little-known meditations and the early historical verse of Canada’s Confederation Poets.

The Ante-Room: Early Stages in a Literary Life by Lovat Dickson and Neville Thompson

Author and publisher (Horatio) Lovat Dickson (1902-87), known as Rache, wrote several biographical works. This short biography recounts Rache’s highly textured recollections of childhood experiences travelling from Australia to Rhodesia to England with a mining engineer father from a Canadian shipping family, followed by adventures and misadventures in Ottawa, Toronto, Montreal, and Temiskaming, until moving to Alberta to study literature under Edmund Broadus.

The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911 by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston

Discover L.M. Montgomery’s early adult years, including her work as a newspaper editor in Halifax, Nova Scotia, her publishing career taking flight, the death of her grandmother, and her forthcoming marriage to a local clergyman.

The Canadian Postmodern: A Study of Contemporary Canadian Fiction by Linda Hutcheon

Examine the theory and practice of postmodernism as seen through both contemporary cultural theory and the writings of Audrey Thomas, Michael Ondaatje, Robert Kroetsch, Margaret Atwood, Timothy Findley, Jack Hodgins, Aritha van Herk, Leonard Cohen, Susan Swan, Clark Blaise, George Bowering, and others.

No Passport: A Discovery of Canada, Revised Edition, by Eugene Cloutier and Joyce Marshall

A classic of Canadian travel literature, No Passport is Quebecois novelist and broadcaster Eugene Cloutier’s account of his discovery of his country. In the mid-1960s, Cloutier travelled from coast to coast, visiting every province as well as the Yukon. He describes his experiences with wit and elegance. The result is an affectionate portrait of a Canada many still recall but which is no more.

Which books would you add to the list?

Tara Kahn holds a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Wesleyan University and is currently completing her Masters in Anthropology at Columbia University. She is currently an intern in the Academic/Trade marketing department.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A Canada Day reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Book of Common Prayer QuizWars and the lies we tell about themThe top 10 historic places from the American Revolution

Related StoriesThe Book of Common Prayer QuizWars and the lies we tell about themThe top 10 historic places from the American Revolution

What is the American Dream?

In celebrating the founding of this country, many things come to mind when asked to describe the essence of America — its energy and innovation; the various liberties that Americans enjoy; the racial and ethnic mix of its people. But perhaps fundamental to the essence of America has been the concept of the American Dream. It has captured the imagination of people from all walks of life and represents the heart and soul of the country.

It can be found throughout our culture and history. It lies at the heart of Ben Franklin’s common wisdom chronicled in Poor Richard’s Almanack, in the words of Emma Lazarus etched onto the Statue of Liberty, the poetry of Carl Sandburg, or the soaring oratory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. It can be heard in the music of Aaron Copland or jazz innovator Charlie Parker. And it can be seen across skylines from Manhattan to Chicago to San Francisco.

Yet it can also be found in the most humble of places. It lies in the hopes of a single mother struggling on a minimum wage job to build a better life for herself and her children. It rests upon the unwavering belief of a teenager living down some forgotten back road that one day he or she will find fortune and fame. And it is present in the efforts and sacrifices of a first generation American family to see their kids through college.

So what exactly is this thing we call the American Dream? After talking with dozens of Americans and pouring over numerous social surveys, I have come to the conclusion that there are three basic elements to the Dream. The first is that the American Dream is about having the freedom to pursue one’s interests and passions in life. By doing so, we are able to strive toward our potential. Although the specific passions and interests that people pursue are varied and wide ranging, the freedom to engage in those pursuits is viewed as paramount. The ability to do so enables individuals to develop their talents and to truly live out their biographies. America, at its best, is a country that not only allows but encourages this to happen. As one of our interviewees put it when asked about the American Dream, “What I’ve always known it to be is being able to live in freedom, being able to pursue your dreams no matter what your dreams were, and having the opportunity to pursue them.”

A second core feature of the American Dream is the importance of economic security and well-being. This consists of having the resources and tools to live a comfortable and rewarding life. It includes working at a decent paying job, being able to provide for your children, owning a home, having some savings in the bank, and being able to retire in comfort. These are seen as just rewards for working hard and playing by the rules. Individuals frequently bring up the fact that hard work should lead to economic security in one’s life and in the life of one’s family. This is viewed as an absolutely fundamental part of the bargain of what the American Dream is all about.

Finally, a third key component of the American Dream is the importance of having hope and optimism with respect to seeing progress in one’s life. It is about moving forward with confidence toward the challenges that lie ahead, with the belief that they will ultimately be navigated successfully. Americans in general are an optimistic group, and the American Dream reflects that optimism. There is an enduring belief that our best days are ahead of us. This abiding faith in progress applies not only to one’s own life, but to the lives of one’s children and the next generation, as well as to the future of the country as a whole.

These three beliefs, then, constitute the core of the American Dream. They are viewed as the essential components for what a good life looks like in the United States. They remind us of what the sacrifices and struggles of all who came before us were about. And so as we celebrate the founding of our country, it is a time to also remind ourselves what is unique and memorable about the nation as a whole. The American Dream is surely one such feature.

Mark R. Rank is the Herbert S. Hadley Professor of Social Welfare at Washington University in St. Louis. He is the co-author of Chasing the American Dream: Understanding What Shapes Our Fortunes.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: US Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Dennis Cantrell. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What is the American Dream? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe top 10 historic places from the American RevolutionThe month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914Wars and the lies we tell about them

Related StoriesThe top 10 historic places from the American RevolutionThe month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914Wars and the lies we tell about them

Cultural memory and Canada Day: remembering and forgetting

Canada Day (Fête du Canada) is the holiday that suggests summer in all its glory for most Canadians — fireworks, parades, free outdoor concerts, camping, cottage getaways, beer, barbeques, and a few speeches by majors or prime ministers. For children, it is the end of a school year and the beginning of two months of summer vacation. For adults, it is a day off work, often a long week-end to catch up on gardening, getting together with family and friends, and relaxing. We wave flags, dress in red and white, and say happy birthday to Canada. After six months of complaining about the snow and the cold, we complain about the heat and mosquitoes.

Historically however, 1 July 1867 marked a more regional rather than national event. The occasion commemorates the joining of the British North American colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the Province of Canada (later to become Ontario and Quebec). Canada became a dominion of the British empire, and remained linked to Britain until 1982 when Canada became an independent nation, and when the holiday was renamed (from Dominion Day).

Unlike our US counterparts who find many occasions to show their patriotism, Canadians are more restrained in their expression of their love for their country. We become fiercely “Canadian” during the Olympics, when our writers (usually named Alice or Margaret) win Literary prizes, and when our hockey teams win the Stanley Cup. Our national holidays are still based mainly on the Christian calendar (Good Friday, Easter, Christmas), or else reveal the vestiges of our British heritage (Victoria Day). Canada Day is one of the few days we allow ourselves to indulge in national and civic pride.

Happy Canada Day! Photo by Ian Muttoo. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

However, Canada Day evokes different feelings for different people. Feminist activist Judy Rebick, who supported the “Idle No More” movement last year, reminds us that the British North America Act signed on 1 July was “based on the annihilation of most and marginalization of the rest of First Nations.” She says that she does not celebrate Canada Day and never has. Similarly, in a witty and ironic piece that satirizes the inadequacy of the reparations that have been made to First Nations and aboriginal people, playwright and filmmaker Drew Hayden Taylor writes a list of apologies (following the style of Stephen Harper who apologized to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis for the imposition and effects of the residential school system). Hayden Taylor’s tongue-in-cheek apologies include occupying land that “one day, your people would want” and for not staying in “India, where we were originally thought to have come from.” For Chinese Canadians, 1 July is remembered as “Humiliation Day” because in it was on this day in 1923 that the Chinese Immigration Act was enacted. This act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, banned Chinese immigration to Canada until it was repealed in 1947.

The point is that what we celebrate as a nation– the history, the symbols, the rituals, and the food—is selective. When we talk about the past, it is not necessarily about what happened, but the bits and pieces that we choose to remember, highlight, and to commemorate. It is significant that in 2012 Prime Minister Stephen Harper chose to highlight the War of 1812 as a “seminal event in the making of our great country” which he conveniently reconfigures as a “war that saw Aboriginal peoples, local and volunteer militias, and English and French-speaking regiments fight together to save Canada from American invasion.” Harper chooses not to talk about the dispossession of First Nations people from their lands, British administrators’ view of them as dependents and impediments to expansion at that time, but instead, embraces them in his inclusive, revisionary history.

Recent interest in memory, preservation, and heritage have made us become more aware of how history has been presented to us, to the ways our relationship with the past have been mediated by literature, films, images, and national commemorations. The “idea” of Canada can be seen as a consciously constructed culture of memory since its foundations. For example, Kimberly Mair looks at the way the ordering and spatial distribution of objects in a museum neutralizes the colonial and genocidal aspects of aboriginal history for visitors, while Shelley Hulan searches for references to First Nations in the stories of Alice Munro. Doris Wolf and Robyn Green look at works that challenge old ideas of Canada as a settler nation by focusing on the experiences of aboriginal peoples in residential schools.

Other fascinating aspects of memory are trauma and forgetting. Friedrich Nietzsche pointed out that although history is important, the ability to forget is a necessary part of happiness: “He would cannot sink down on the threshold of the moment and forget all the past, who cannot stand balanced like a goddess of victory, without growing dizzy and afraid, will never know what happiness is – worse, he will never do anything to make others happy.” Recently, Canadian diasporic authors such as Madeleine Thien, David Chariandy, Dionne Brand, and Esi Edugyan reveal what it means to be haunted by their past in a globalized age. By paying attention to how we remember, the roles played by literary and cultural representations in constructing our memories, we see how the present is not only influenced by the past, but how the present continues to rework and reshape our understanding of the past.

Eleanor Ty (鄭 綺 寧) is Professor of English & Film Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University in Ontario, Canada. She has published on Asian North American and on 18th Century literature. Author of Unfastened: Globality and Asian North American Narratives (U of Minnesota P, 2010), The Politics of the Visible in Asian North American Narratives (U Toronto P 2004), she has co-edited with Russell J.A. Kilbourn, The Memory Effect: The Remediation of Memory in Literature and Film (Wilfrid Laurier UP 2013), with Christl Verduyn a collection of essays, Asian Canadian Writing Beyond Autoethnography (Wilfrid Laurier UP 2008). With Cynthia Sugars, she has co-edited Canadian Literature and Cultural Memory.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Cultural memory and Canada Day: remembering and forgetting appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914The top 10 historic places from the American RevolutionWars and the lies we tell about them

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914The top 10 historic places from the American RevolutionWars and the lies we tell about them

Getting to know Grove Music Associate Editor Meghann Wilhoite

Since joining the Grove Music editorial team, Meghann Wilhoite has been a consistent contributor to the OUPblog. Over the years she has shared her knowledge and insights on topics ranging from football and opera to Monteverdi and Bob Dylan, so we thought it was about time to get to know her a bit better.

Do you play any musical instruments? Which ones?

In order of capability, I play the pipe organ, piano, synths, and guitar. I also sing a bit, but I gave up on my dream of being an opera singer long ago!

Organ Console, Holy Trinity, Buffalo, NY. Photo by Jarle Fagerheim. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Do you specialize in any particular area or genre of music?

As an organist, I mostly play Baroque music (I Matthew Hough, which we’ll get to recording as soon as we have the funding. As a pianist, I play lots of different stuff from Classical era onwards. As a synth player and guitarist I play indie rock, mostly stuff I’ve written or stuff I’ve collaborated on.

What artist do you have on repeat at the moment?

My current lifestyle sort of dictates what I listen to right now: I’m either on the subway or blocking out ambient sounds in the office (nothin’ but love for my fellow cube dwellers), which means it’s difficult to listen to stuff where there’s an extreme difference between the loudest and the softest sound. Thus, artists like Interpol, Cocteau Twins (Elizabeth Fraser swoon), and Grimes dominate my playlist; if I had more time in quieter spaces I would also be listening to more avant-garde stuff as well.

What was the last concert/gig you went to?

The last concert I went to was part of the series I help run called Music at First; we were presenting the music of Jerome Kitzke, and it was pretty wild.

How do you listen to most of the music you listen to? On your phone/mp3 player/computer/radio/car radio/CDs?

Phone on the subways, computer (Pandora or Spotify) at work.

Do you find that listening to music helps you concentrate while you work, or do you prefer silence?

Music definitely helps me concentrate while I work, with the exception of creative writing.

Has there been any recent music research or scholarship on a topic that has caught your eye or that you’ve found particularly innovative?

Actually, my most recent scholarship binge has been on historiography, specifically the white-washing of European history (there’s a great Tumblr called MedievalPOC that focuses on the white-washing of European art). I would love to do more research on people of color with regards to the Western music canon (you know, those same hundred or so pieces by the same twenty or so composers that every music history textbook teaches you about).

Who are a few of your favorite music critics / writers?

Anastasia Tsioulcas (NPR, et al.) and Steve Smith (Boston Globe) are two critics/writers whose work I admire. They give an honest take on the music they’re reviewing without getting polemical, and they both promote gender parity within the field.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Associate Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Getting to know Grove Music Associate Editor Meghann Wilhoite appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSongs of the Alaskan InuitJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever sawScoring independent film music

Related StoriesSongs of the Alaskan InuitJosephine Baker, the most sensational woman anybody ever sawScoring independent film music

Sovereign debt in the light of eternity

From Greece to the United States, across Europe and in South America – sovereign debt and the shadow of sovereign debt crisis have loomed over states across the world in recent decades. Why is sovereign debt such a pressing problem for modern democracies? And what are the alternatives? In this video Lee Buchheit discusses the emergence of sovereign debt as a global economic reality. He critiques the relatively recent reliance of governments on sovereign debt as a way to manage budget deficits. Buchheit highlights in particular the problems inherent in expecting judges to solve sovereign debt issues through restructuring. As he explores the legal, financial and political dimensions of sovereign debt management, Buchheit draws a provocative conclusion about the long-term implications of sovereign debt, arguing that “what we have done is to effectively preclude the succeeding generations from their own capacity to borrow”.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Buchheit speaks at the launch of Sovereign Debt Management, edited by Rosa M. Lastra and Lee C. Buchheit.

Lee C. Buchheit is a partner based in the New York office of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP. Dr Rosa María Lastra, who introduces Buchheit’s lecture, is Professor in International Financial and Monetary Law at the Centre for Commercial Law Studies (CCLS), Queen Mary, University of London.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Sovereign debt in the light of eternity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCan we finally stop worrying about Europe?Discussing proprietary estoppel: promises and principlesThe Book of Common Prayer Quiz

Related StoriesCan we finally stop worrying about Europe?Discussing proprietary estoppel: promises and principlesThe Book of Common Prayer Quiz

June 30, 2014

The Book of Common Prayer Quiz

We print many different types of bibles here at Oxford University Press, one popular line being our Book of Common Prayer. While this text is used worldwide, you may not know about its interesting history. From the fact that there are a half a dozen books in print with this title, or perhaps that it is not so much a collection of prayers as a sort of “script” to be used, there is much you may not know about this text. Take our quiz below to learn more.

We print many different types of bibles here at Oxford University Press, one popular line being our Book of Common Prayer. While this text is used worldwide, you may not know about its interesting history. From the fact that there are a half a dozen books in print with this title, or perhaps that it is not so much a collection of prayers as a sort of “script” to be used, there is much you may not know about this text. Take our quiz below to learn more.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Alyssa Bender is a marketing coordinator at Oxford University Press. She works on religion books in the Academic/Trade and Reference divisions, as well as Bibles.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Book of Common Prayer Quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFaith and science in the natural worldWhat price books?Wars and the lies we tell about them

Related StoriesFaith and science in the natural worldWhat price books?Wars and the lies we tell about them

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers