Oxford University Press's Blog, page 792

July 7, 2014

Theodicy in dialogue

Imagine for a moment that through a special act of divine providence God assembled the greatest theologians throughout time to sit around a theological round table to solve the problem of evil. You would have many of the usual suspects: Athanasius, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Karl Barth. You would have the mystics: Gregory of Nyssa, Julian of Norwich, Catherine of Sienna, Teresa of Ávila, and Thomas Merton. You would have the scholastics: Anselm, Peter Lombard, Bonaventure, and John Duns Scotus. You would have the newcomers: Jürgen Moltmann, Sarah Coakley, and Miroslav Volf. You might even have some unknown names and faces. Feel free to place your favorite theologian around the table. With these diverse and dynamic minds, you could expect to have a spirited conversation.

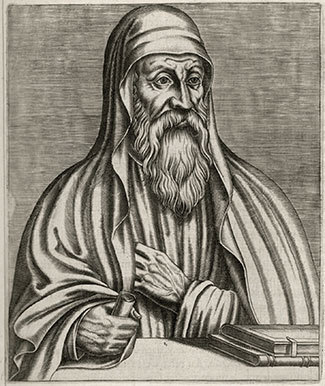

If you were to moderate the discussion around our massive oak table you would have the daunting task of keeping pace with these agile intellects and perhaps of negotiating a few inflated egos. It might be difficult to get a word in edgewise. Augustine would be affable and loquacious. Aquinas would be precise and ponderous. Luther would be humorous and polemical. But where would Origen of Alexandria (c. 185-254) fit in, the greatest theologian of Eastern Christianity? What would he say about the problem of evil? All agree he deserves an honored seat at the table, but often others around the table suck all the oxygen out of the room, leaving little air for his profound insights, particularly on the problem of evil, which anticipate later developments while also reflecting his distinctive intellectual milieu. Let’s imagine how the conversation might go.

![Disputa di Santo Stefano fra i Dottori nel Sinedrio by Vittore Carpaccio [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1404911468i/10298266._SX540_.jpg)

Disputa di Santo Stefano fra i Dottori nel Sinedrio by Vittore Carpaccio [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Thomas Aquinas: “Welcome all. I’ve been asked to begin our discussion. Let me say first that the problem of evil represents the most formidable conceptual challenge to theism.”Augustine: “I agree, but the problem’s resolved once we realize that evil doesn’t exist per se, like a malevolent substance, it’s simply the privation of the good. At any rate, God doesn’t create evil, we do, and God eventually brings good out of evil, so evil doesn’t have the final say.”

Sarah Coakley: “It can’t be settled that easily. I’m suspicious of grand theological narratives that simplify conceptual complexities. Let’s retrieve some neglected voices on the problem.”

Gregory of Nazianzus: “I’ve written a theological poem about it that I’d like to share.”

Basil of Caesarea: “Please don’t. I can’t sit through another one of your theological poems.”

Gregory of Nazianzus: “Fine. I’m out of here. I didn’t want to come in the first place.”

Jürgen Moltmann: “That was a little rude, Basil, you know Greg’s sensitive, especially about his theological poetry, but let’s get back to the topic at hand. We can’t answer the theodicy question in this life, but we can’t discard it either. All we can do is turn to the God who suffers with, from, and for the world for solidarity with us in our suffering. Only the suffering God can help.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer: “I couldn’t have said it better myself.”

Karl Rahner: “The problem of evil is a fundamental question of human existence.”

John of the Cross: “I have endured many dark nights agonizing over it.”

Julian of Norwich: “Fear not, brother John, all will be well.”

John Calvin: “Not for those predestined to the fires of hell, but that’s part of the mystery of divine providence, which is inviolable, so in a refined theological sense, all will be well.”

Julian of Norwich: “I think we have different visions of what wellness means.”

Martin Luther: “You’re all crazy casuists. We’re probing into the deeps of divine mystery. We’re way out of our depth. We’re just small, sinful worms: we can’t possibly solve these riddles.”

F. D. W. Schleiermacher: “Settle down, Martin, we’re just talking. What do you think, Karl?”

Karl Barth and Karl Rahner (simultaneously): “Which Karl?”

Miroslav Volf: “Let’s give the Karls a pass. We heard enough from them last time, and we want to make room for others. Barth would probably just talk about ‘nothingness’ anyway.”

Hans Urs von Balthasar: “Origen, you’ve been quiet, and you haven’t touched your food, what are your thoughts on the problem of evil? Won’t you give us the benefit of your deep erudition?”

Origen. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Origen: “I’ve often pondered the question of the justice of divine providence, especially when I observe the unfair conditions people inherit at birth. Some suffer more than others for no apparent reason, and some are born with major disadvantages, such as blindness or poverty.”

Dorthee Sölle: “I appreciate your attentiveness to the lived experience of suffering, Origen, and not just the theoretical problem of how to reconcile divine goodness and omnipotence with evil.”

Gregory of Nyssa: “Me too, but how do you account for the disparity of fortunes in the world? How do you preserve cosmic coherence in the face of so much injustice and misfortune?”

Origen: “I’ll tell you a plausible story that brings many of these theological threads together. Before the dawn of space and time, God created disembodied rational minds, including us. We existed in perfect harmony and happiness until through either neglect or temptation or both we drifted away from God. Since all reality participated in God’s goodness, we were in danger of drifting out of existence altogether the further we strayed from our original goodness, so God, in his benevolence, created the cosmos to catch us and to enable our ascent back to God. Our lot in life, therefore, reflects the degree of our precosmic fall, which preserves divine justice. The world, you see, exists as a schoolroom and hospital for fallen souls to return to God. Eventually, all may return to God, since the end is like the beginning, but not until undergoing spiritual transformation. We must all traverse the stages of purification, illumination, and union, both here and in the afterlife, until our journey back to God is complete and God will be all in all.”

John Hick: “That makes perfect sense to me.”

Irenaeus: “Should you really be here, John? That’s a little far out there for me, Origen.”

Athanasius: “Origen clearly has a complex, subtle mind that doesn’t lend itself to simplification. It’s a trait of Alexandrian thinkers, who are among the best theologians in church history.”

John Chrysostom: “Spare me.”

Augustine: “I think I see what Origen means, especially about the origin and ontological status of evil and God’s goodness. It’s not too far from my thoughts, except for his speculative flights.”

Thomas Aquinas: “Our time is up. We haven’t solved the problem of evil, but we seem confident that God ultimately brings good out of evil, however dire things seem, and that’s a start.”

Francis of Assisi: “Let’s end in prayer.”

Thank goodness Hans Urs von Balthasar asked for Origen’s opinion, since I doubt he would have offered it otherwise. What our imaginary theological roundtable and fictitious dialogue reveals, hopefully, is that there are a variety of voices in theology that speak to the problem of evil. Some, such as Augustine and Aquinas, are well known. Others, such as Origen, have been neglected, partly because of his complicated reception, and partly because of the subtlety and originality of his thought.

Mark Scott is an Arthur J. Ennis Postdoctoral Fellow at Villanova University. He has published on the problem of evil in numerous peer-reviewed journals in addition to his book Journey Back to God: Origen on the Problem of Evil.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Theodicy in dialogue appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of JulyThe month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914True or false? Ten myths about Isaac Newton

Related StoriesRhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of JulyThe month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914True or false? Ten myths about Isaac Newton

Poetic justice in The German Doctor

Film is a powerful tool for teaching international criminal law and increasing public awareness and sensitivity about the underlying crimes. Roberta Seret, President and Founder of the NGO at the United Nations, International Cinema Education, has identified four films relevant to the broader purposes and values of international criminal justice and over the coming weeks she will write a short piece explaining the connections as part of a mini-series. This is the final one, following The Act of Killing, Hannah Arendt, and The Lady.

By Roberta Seret

One can say that Dr. Josef Mengele was the first survivor of Auschwitz, for he slipped away undetected in the middle of the night on 17 January 1945, several days before the concentration camp was liberated. Weeks later, he continued his escape despite being detained in two different Prisoner of War detention camps.

He made his way to Rome, a sanctuary for Nazi war criminals, where he obtained a new passport from Vatican officials. Continuing to Genoa with the help of the International Red Cross and a Fascist network, he embarked on the North King ship in 1949 to Buenos Aires under the alias of Helmut Gregor.

President Juan Peron had 10,000 blank Argentine passports for the highest Nazi bidders. Buenos Aires became their home; there Mengele lived, respected and comfortable, until 1960 when Eichmann was kidnapped by the Mossad just streets away. Afraid he’d be next, Mengele decided it would be safer for him in Paraguay with the support of the pro-Nazi dictator, Alfredo Stroessner. He stayed in Asunción for one year.

The Argentine film, The German Doctor (2014), takes us in media res to 1960 Patagonia and Bariloche, a beautiful mountain oasis in the Andes that reminds Mengele of “home.” This fictional addition to his biography, serves as a six-month stopover before he escapes to Paraguay.

Lucia Puenzo, Argentine filmmaker, has adapted her own novel, Wakolda, for the screen. She adroitly mixes fiction with history and truth with imagination in a tight, tense-filled interpretation that keeps us mesmerized. Yet, as we watch the scenes unfold, we wonder which ones are based on fact and how far should poetic justice substitute for historical accuracy.

The director takes advantage of our “collective conscience” of morality and memory regarding the identity of Dr. Mengele. Despite not once hearing his name, we know who he is, although the characters do not. The director uses our associating him with evil to enhance tension and catapult plot – a clever device that works well.

What is biographically accurate in the film is that Mengele continues his experiments on human beings in order to create the perfect race. The director uses this premise, then extrapolates to fiction and sets the stage with a family that Mengele befriends. The doctor sees an opportunity to experiment with charming Lilith, the under-developed twelve-year-old and injects into her stomach growth hormones that work for cattle. He also gives “vitamins” to the girl’s pregnant mother, Eva, once he realizes she is carrying twins. When the babies are born, he continues his experiments by putting sugar in the formula for the weaker of the two. As the infant cries dying and Mengele studies the reaction, we shudder that the Angel of Death has once again achieved Evil.

The experiments on people that Mengele is obsessed with in the film, is a continuation of his sadistic work at Auschwitz with pregnant women, twins, and genetics. His lab experiment on a mother who had just given birth was notorious. He taped her lactating breasts while taking notes on how long the infant would cry without receiving her milk. When he left for dinner, the distraught mother desperately found morphine for her dying baby.

Mengele was also known to inject dye into the iris of prisoners’ eyes (without anesthesia) to see if he could change the brown to an Aryan blue. He documented his results by pinning each eyeball to a wooden board.

And there were more experiments on thousands of human beings.

Josef Mengele, from 1943-45, appeared each day at Auschwitz’s train station for Selektion. Wearing white gloves, polished high black boots, and carrying a stick, his evil hand pointed Left and Right to order more than 400,000 souls to leave this world through chimneys as ashes. His crimes against humanity can never be forgotten.

After living more than 30 years undetected in South America, Mengele died in 1979 of a heart attack while swimming in the warm waters near São Paulo. This peaceful death for such a monster reinforces his ultimate crime. Film director, Lucia Puenzo, would have been well-inspired to have finished The German Doctor with this horrific and true scene.

Roberta Seret is the President and Founder of International Cinema Education, an NGO based at the United Nations. Roberta is the Director of Professional English at the United Nations with the United Nations Hospitality Committee where she teaches English language, literature and business to diplomats. In the Journal of International Criminal Justice, Roberta has written a longer ‘roadmap’ to Margarethe von Trotta’s film on Hannah Arendt. To learn more about this new subsection for reviewers or literature, film, art projects or installations, read her extension at the end of this editorial.

The Journal of International Criminal Justice aims to promote a profound collective reflection on the new problems facing international law. Established by a group of distinguished criminal lawyers and international lawyers, the journal addresses the major problems of justice from the angle of law, jurisprudence, criminology, penal philosophy, and the history of international judicial institutions.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Poetic justice in The German Doctor appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorshipHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityPsychodrama, cinema, and Indonesia’s untold genocide

Related StoriesThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorshipHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityPsychodrama, cinema, and Indonesia’s untold genocide

You can save lives and money

There is a truism in the world that quality costs, financially. There is a grain of truth in this statement especially if you think in a linear way. In healthcare this has become embedded thinking and any request for increasing quality is met with a counter-request for more money. In a cash-strapped system the lack of available money then results in behaviour that limits improvement. However, as an ex-colleague once said “we have plenty of money, we just choose to spend it in the wrong places”. This implies that if we were to un-spend it in the wrong place we would have plenty of spare cash.

The problem in healthcare, as in most service organisations, is that the system that delivers client value (in this case healthcare to patients) isn’t visible to those working in it. Indeed the only person that see’s the invisible system is the patient receiving that care. Our first task is to make the system visible and we can do this by producing a process map; a series of boxes describing the various activities all linked by one or more arrows. These maps can range from very high level to extremely detailed; the trick is to choose wisely and to look at the process from the patient’s perspective. Having produced your map the next step is to put some data onto it. Once you understand the process you can then start to hypothesise a different way of undertaking the work. Ask yourself;

would pay your own money for a particular step; if not, then question why it exists

are the steps in the right order?

do they require roughly equal amounts of resource

are there any bottlenecks?

Some four years ago, supported by a grant from the Health Foundation, we started to ask ourselves some of these questions in relation to the delivery of care to frail elderly patients. The answers were, in some cases, completely counter-intuitive. We found that some elderly patients stayed in hospital for many weeks after they could have left. There were many and varied reasons for this but none of them were related to acute hospital care. It was the wider disjointed system with its multiple hand-offs and traditional organisational rules that governed this. It was no-one’s fault, yet it was everyone’s problem.

So like eating the proverbial elephant we decided to start somewhere. It needed an individual clinician to put their hand up and take that first step. That first step was to try something different for one day; if it didn’t work then nothing was lost. The step was tried and the world didn’t end. Instead we found out that changing our normal system of “batching emergency admissions together so that they could all be seen the next day thus maximising consultant efficiency” to “let’s see them as they come in” meant that we reduced the time from arrival to senior specialty review by half. We also found opportunity to remove potential harm.

Having repeated this three times a few other consultants chose to take the trip with us and we repeated the same test over three days. That worked. So we tried for a full week. That also worked. By this time, and we were now almost six months into the journey, a range of staff including consultants, nurses, therapists, ambulance staff, managers and secretaries had all been involved in the tests and had all in their own way contributed to testing the new design and delivery.

The next steps were profound. A suggestion from the clinical director that all the consultants should change their job plans (on the same day) to deliver the new service was met with no dissent. A first in my experience. The physical manifestation of the change, the birth of the Frailty Unit then followed a few weeks later.

What was the cost of this? In terms of real life spend very little. The physical reconfiguration was largely cash neutral. Yes we spent some real money on service improvement support and staff invested their time; in the great scheme of things this was petty cash. But did it really change anything? Some hard metrics showed that we increased the number of patients who were discharged within 48 hrs from 18% to 24% and we reduced the number of total specialty beds by almost a quarter. We didn’t increase our readmissions and our biggest surprise was that we decreased our in-hospital mortality. In softer terms we now see many patients on the day that they arrive; we know how to potentially change our outpatient service and the staff on the Frailty Unit have become masters of caring for Frail Elderly patients.

Involving staff + Improvement science = Better outcomes + Lower Cost

Paul Harriman MBA, TDCR, FETC, HDCR, DCR(R). Paul originally trained as a Diagnostic Radiographer at the Middlesex Hospital qualifying in 1977. He worked in a number of hospitals and obtained his HDCR and TDCR qualifications before coming to Sheffield in 1986. Whilst working as a Superintendent Radiographer at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital, he undertook an MBA and was also selected to join the General Management Scheme. He has since held a number of posts within the Trust working both within clinical directorates and corporate functions.

Paul has major interests in system thinking, improvement science, the use of data for decision making and has been working with Statistical Process Control charts for over 20 years. The main focus of his current work is supporting Geriatric and Stroke Medicine, to understand, analyse and challenge the current work processes. He and Kate Silvester were part of the Flow, Cost, Quality programme sponsored by the Health foundation. He is a co-author of the paper ‘Timely care for frail older people referred to hospital improves efficiency and improves mortality without the need for extra resources‘ for the journal Age and Ageing.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Blue tone of beds and machines in hospital. By pxhidalgo, via iStockphoto.

The post You can save lives and money appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow to prevent workplace cancerThe significance of gender representation in domestic violence unitsThe unseen cost of policing in austerity

Related StoriesHow to prevent workplace cancerThe significance of gender representation in domestic violence unitsThe unseen cost of policing in austerity

July 5, 2014

The unseen cost of policing in austerity

It will not come as news to say that the public police are working under challenging conditions. Since the coalition government came to power in 2010, there have been wide-ranging and deep cuts to the funding of public services, the police included. This was the institution which once enjoyed a privileged position as the “go-to” service for political parties to improve themselves in the eyes of the electorate by being “tough on crime” through ever increasing police numbers. Numbers of police officers and staff rose year on year from 2000 to 2010, an increase of 13.7%. All that has now changed, and the most recent statistics show that the police service has now reduced in size by 11%, and is roughly equivalent to where it was in 2001. While police officers themselves cannot be made redundant, vacant positions are not being filled when officers leave or retire. Police and Community Support Officers (PCSOs) can be made redundant, and this has happened in a few areas, as well as vacancies not being filled. What does this mean for being “tough on crime”?

Well, to be honest, not much on face value. As any good first year Criminology student should be able to tell you, the overall crime rate has been falling more or less steadily since 1995. This drop in crime started before police numbers rose, and occurred in other countries as well where police numbers may not have changed to the degree they did in England and Wales. The cause for the drop in crime is the subject of much debate, and will not be pursued in depth here. However, what is clear is that the sheer number of police officers in a police force does not have a direct link with the amount of crime that area experiences. What is more important is what is done with those officers, and this is where my concern with the current state of policing lies.

While the last Labour government regularly pumped up the number of officers to redress their image of being soft on crime, they also made two significant changes to policing practice. One was the introduction of PCSOs in 2002 and the other was the national roll-out of Neighbourhood Policing in 2008. While both may have been derided in the beginning as being more for show than of any real substance, I feel both have made significant changes in the relationship of the police to many local areas and with this has come a reorientation to the police occupational culture itself. Research I have conducted on partnership work and PCSOs suggests that these changes have made some sections of the police more open to working with those outside of their organisation, has enhanced the commitment the police have to crime prevention and long-term problem solving, and has led to better information sharing and relationships between the police and local residents.

To be clear – I am not arguing that all is fine and well in policing. However, the situation we have now is far better than what was the case in the 1980s and 1990s. Rather than “community policing” referring to police officers in panda cars whizzing through residential areas, going from job to job, we now have officers and staff who walk their beats, get to know many of the people and places within it and have the time to attend to the “small stuff”. By this I mean the anti-social, low-level crimes and incivilities which may not set performance targets on fire, but which mean a great deal to the daily lives of thousands of people. Officers, usually PCSOs, can take the time to find out about these concerns and either address the matter themselves or find the most appropriate partner agency to do so (the staff of which they know by name and often have their numbers programmed into their mobile phones). In return, residents start to build trust in their local neighbourhood team, which may develop over time into information sharing of interest to constables and detectives.

However, all this is now in danger of being eroded. The budget cuts mean that the officers and staff who remain in neighbourhood teams have much heavier workloads, including the PCSOs. It is far more difficult now to attend to the “small stuff” and to conduct visible patrols. Partner agencies are also facing severe budget cuts and this will impact on their ability to work collaboratively with the police as they have fewer resources to share. This means that the police lose opportunities to make connections in their local communities and build valuable social capital. Residents are not getting the attention they desire from their local police and so will have fewer reasons to trust them. In addition to these losses to police practice and community relationships is a much less visible but no less significant loss – the reorientation of the police occupational culture. Police officers became more open to working with partners, PCSOs, residents and to consider long-term problem solving once they had experienced the benefits of doing so. Many of the traditional hostilities towards the “other” were reducing noticeably among the neighbourhood officers with whom I have conducted research. This widening of the police world view will, I fear, also be lost in the current budget structures. This is not a savings for policing – it is a very high cost indeed.

Dr Megan O’Neill is the Chair of the British Society of Criminology Policing Network, and a lecturer at the Scottish Institute of Policing Research, University of Dundee. She is the author of “Ripe for the Chop or the Public Face of Policing? PCSOs and Neighbourhood Policing in Austerity” (available to read for free for a limited time) in Policing.

The full article will be available this June in Policing, A Journal of Policy and Practice, volume 8.3. This peer-reviewed journal contains critical analysis and commentary on a wide range of topics including current law enforcement policies, police reform, political and legal developments, training and education, patrol and investigative operations, accountability, comparative police practices, and human and civil rights

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: UK police vehicles at the scene of a public disturbance. © jeffdalt via iStockphoto.

The post The unseen cost of policing in austerity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTracking the evidence for a ‘mythical number’10 things you may not know about the Police FederationThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorship

Related StoriesTracking the evidence for a ‘mythical number’10 things you may not know about the Police FederationThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorship

The first rule of football is… don’t call it soccer

The United States and Great Britain are two countries separated by a common language – a phrase commonly attributed to Shaw sometime in the 1940s, although apparently not to be found in any of his published works. Perhaps another way of looking at it is to say that they are two countries separated by a different ball – a sentiment that is particularly apt when football’s World Cup comes around.

Of course, it isn’t quite as simple as that. For years we’ve heard how football is becoming ever more popular in the USA. Major League Soccer’s profile continues to build, and indeed, the US even hosted the World Cup in 1994, and has twice won the FIFA Women’s World Cup. But despite this, football pales into insignificance compared with other big US sports. The National (American) Football League brought in 9 billion dollars in revenue in 2013, whereas Major League Soccer earned only about half a billion; even the National Hockey League earned over 3 billion. If you’re one of those Americans who hasn’t yet become a diehard fan, here’s a potted (and tongue) guide to bluffing your way into sounding knowledgeable about the beautiful game.

The first rule of football is…

…don’t call it soccer, certainly not within earshot of someone who thinks of it as ‘proper’ football. This is probably the most crucial element in giving the impression that you’ve been into this game for decades. Naturally this can be difficult if you are trying to differentiate between two different sports (in the UK it is easy – American football v football). Soccer, the word, comes from an abbreviation for Association (from Association Football, the ‘official’ name for the game) plus the addition of the suffix -er. This suffix (originally Rugby School slang, and then adopted by Oxford University), was appended to ‘shortened’ nouns, in order to form jocular words. Rugger is probably the most common example, but other examples included in the Oxford English Dictionary are brekker (for breakfast), bonner (for bonfire), and cupper (a series of intercollegiate matches played in competition for a cup).

Apart from its origins being decidedly British, you will find plenty of examples of soccer being used by British people over the decades. But in terms of the history of the language, it’s something of a 19th-century johnny-come-lately: by contrast, football has been used since the 1400s. In modern usage, in order to blend in with the diehard fans, it’s preferable to stick to football – and, when speaking to these fans, never, ever call it Association Football.

A quick reference to sound like a football native:

Match vs game

Match is used in relation to football, but game (used in American Football) is actually the older sense. Game, meaning a competitive activity governed by rules of play, is found in Old English – while match in a similar sense dates to the 16th century. (The word match is also found in Old English, with reference to spouses or people of equal standing.)

Pitch vs field

Pitch, meaning ‘the area of play in a field game’ and used in football, is quite a recent addition to English — currently first found in the late 19th century — and field (with a similar definition, used for American football) predates it by over 150 years. Yet fashions change, and you should refer to a football pitch if you want to be accepted by aficionados in Britain.

Boots vs cleats / shoes

The distinction between boots (used in football) and shoes (in American football) isn’t particularly noteworthy, but the use of cleats is more intriguing. It’s actually an example of synecdoche: the part is used to represent the whole. This becomes clear if you realize that cleats are the projections on the sole of a shoe, designed to prevent the wearer losing their footing (which are commonly called studs in British English).

Extra time vs overtime

As the name suggests, extra time is a further period of play in football, added on to a game if the scores are equal and the match must be decided (not to be confused with injury time, added to compensate for time lost dealing with injuries). Overtime describes the same event in North American games, drawing on the older sense of ‘time worked in addition to one’s normal working hours’. The first use of both terms is currently dated to the early 20th century, with extra time coming first.

To mark vs to guard vs to cover

Guarding in basketball, and marking in a variety of British games including football, means keeping close to an opponent in order to prevent them from getting or passing the ball. To add to the international confusion, in Australian Rules Football, marking a ball means catching it from a kick of at least ten metres and is to be celebrated – whereas, unless you’re the goalkeeper (or in the crowd), catching the ball at all in football is a handball and a foul. In American football, a defensive player will cover an offensive player.

Kit vs uniform

A uniform (worn for American sports) may sound more militaristic than a kit (worn in football), but the latter actually has fairly regimental (albeit more informal) origins – the sense comes from kit as the equipment of a solider (also known as articles of kit). This sense, in turn, relates to an earlier sense of kit as a container for carrying commodities – from the Dutch kitte, a wooden vessel made of hooped staves.

There’s no other way

In American Football, there are numerous ways to score. In football, there is only one. If the ball ends up in the back of the net (provided there has been no infringement of the rules), it’s a goal. Whether scored by a header, from the penalty spot, a volley, route one, scissor kick, after a glorious mazy run from one end of the pitch to the other, or even if it hits a defending player on the bottom/knee/shoulder and deflects past the goalkeeper into the goal, it’s just a goal, and only counts for one point.

0-0 can be exciting

It’s probably a bit of an urban myth that Americans bemoan the fact that it’s perfectly possible to sit through 90 minutes of football, and for the end result to be 0-0. Meaning that no one scored. While any self-respecting football fan will have witnessed the dourest of dour games which end up as a goalless draw, there are action-packed games which inexplicably end up goalless due to one or more goalies playing a blinder. You’ll just have to believe us on this. While you can’t immediately tell from the numbers written as symbols, that ‘0-0’ is nil-nil rather than zero-zero. A good way to expose your ignorance amongst football fans is to refer to a result being two-zero, as the 0 is always termed nil in football. Nil is a contraction of the Latin nihil, meaning ‘nothing’, and also to be found in the word nihilism (the belief that nothing in the world has a real existence).

And last, but not least, don’t worry too much about explaining the offside rule. Plenty of people can’t.

A version of this post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Fiona McPherson is a Senior Editor with the Oxford English Dictionary.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Soccer Balls Net 7-22-09 1 by Steven Depolo. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The first rule of football is… don’t call it soccer appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFootball arrives in BrazilHow social media is changing languageTourism and the 2010 World Cup

Related StoriesFootball arrives in BrazilHow social media is changing languageTourism and the 2010 World Cup

Catching up with Alyssa Bender

In an effort to get to know our Oxford University Press staff better, we’re featuring interviews with our staff in different offices. Read on for our Q&A with Alyssa Bender, marketing coordinator for our religion and theology Academic/Trade books and Bibles in New York.

When did you start working at OUP?

When did you start working at OUP?

July 2011.

What is the most important lesson you learned during your first year on the job?

Take notes on everything! From training sessions for programs to meetings where I had no idea what anyone was talking about, filling up my notebook (and constantly revisiting later) was my saving grace.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

How many books we come out with every year. Never could have guessed we publish the volume that we do.

What’s the least surprising?

While it surprised me at first, it really shouldn’t have—everyone here is so intelligent and talented. It’s likely that those are just the type of people who are drawn to work at university presses, but it’s still great to work with such smart people every day.

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place? What do you think about that now?

It was a job in publishing! Those are hard to come by when you’re first out of school. Luckily, it turned out to be an awesome job with a great team. Still is.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Open my inbox and sort the emails by priority.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

Lots of answering emails. Also, lots of meetings. In between emails and meetings, there’s creating marketing plans, pulling sales reports, gathering social media content, proofing newsletters and catalogs, updating website copy, submitting review copy requests, making flyers…the list goes on.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

A 3D paper pear made out of note paper. A gift from my manager, who brought it back from her trip to Japan.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your job?

Seeing my efforts pay off when a book does really well.

What’s the most difficult part of your job?

Determining reprint quantities. No matter how much research you do, you can still be way off in your estimates. It’s one of the many aspects of my job that only gets easier the more experience you have doing it.

What is the most exciting project you have been part of while working at OUP?

Helping to launch the @OUPMusic Twitter, back when I still worked on the music team. It was really fun to be a part of the strategy conversations and learn what goes on behind the scenes of company Twitter accounts. It was also fun to be behind some of the tweets and interact with the followers.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments at work.

Pulling off a successful American Academy of Religion/Society for Biblical Literature conference this past November. As the team leader for the conference, I was responsible for organizing almost every detail about our presence there, from deciding the booth layout, to determining the books we would bring (and how many of each), to making sure enough people were present for set-up/tear down. It was my first AAR/SBL, and my first large meeting in general, and I was really happy with how it all turned out.

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

Cleaning my desk! So many piles of paper, bookmarked galleys, meeting notes, books, and folders everywhere!

Alyssa Bender joined Oxford University Press in 2011. She is currently a Marketing Coordinator for our religion and theology Academic/Trade books and Bibles in New York.

The post Catching up with Alyssa Bender appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Book of Common Prayer QuizGetting to know Grove Music Associate Editor Meghann WilhoiteMartyrdom and terrorism: a Q&A

Related StoriesThe Book of Common Prayer QuizGetting to know Grove Music Associate Editor Meghann WilhoiteMartyrdom and terrorism: a Q&A

What test should the family courts use to resolve pet custody disputes?

This is my dog Charlie. Like many pet owners in England and Wales I see my dog as a member of my family. He shares the ups and downs of my family life and is always there for me. But what many people don’t realise is that Charlie, like all pets, is a legal ‘thing’. He falls into the same category as my sofa. The law distinguishes between legal persons and legal things and Charlie is a legal thing and is therefore owned as personal property. If my husband and I divorce and both want to keep Charlie, our dispute over where Charlie will live would come within the financial provision proceedings in the family courts. What approach will the family courts take to resolve this dispute? It is likely that the courts will adopt a property law test and give Charlie to the person who has a better claim to the property title. This can be evidenced by whose name appears on the adoption certificate from the local dogs home or who pays the food and veterinary bills. Applying a property test could mean that if my husband had a better property claim, Charlie would live with him even if Charlie is at risk of being mistreated or neglected.

Charlie the dog. Photo courtesy of Deborah Rook

Property versus welfare

Case law from the United States shows that two distinct tests have emerged to resolving pet custody disputes: firstly, the application of pure property law principles as discussed above; and secondly, the application of a ‘best interests of the animal’ test which has similarities to the ‘best interests of the child’ test used in many countries to determine the residency of children in disputes between parents. On the whole, the courts in the United States have used the property law test and rejected the ‘best interest of the animal’ test. However, in a growing number of cases the courts have been reluctant to rely solely on property law principles. For example, there are cases where one party is given ownership of the dog, having a better claim to title, but the other is awarded visitation rights to allow them to visit. There is no other type of property for which an award of visitation rights has been given. In another case the dog was given to the husband even though the wife had a better claim to title on the basis that the dog was at risk of severe injury from other dogs living at the wife’s new home.

Pets as sentient and living property

What the US cases show is that there is a willingness on the part of the courts to recognise the unique nature of this property as living and sentient. A sentient being has the ability to experience pleasure and pain. I use the terminology ‘pet custody disputes’ as opposed to ‘pet ownership disputes’ because it better acknowledges the nature of pets as living and sentient property. There are important consequences that flow from this recognition. Firstly, as a sentient being this type of property has ‘interests’, for example, the interest in not being treated cruelly. In child law, the interest in avoiding physical injury is so fundamental that in any question concerning the residency of a child this interest will prevail and a child will never be knowingly placed with a parent that poses a danger to the child. A pet is capable of suffering pain and has a similar relationship of dependence and vulnerability with its owners to that which a child has with its parents. Society has deemed the interest a pet has in avoiding unnecessary suffering as so important as to be worthy of legislation to criminalise the act of cruelty. There is a strong case for arguing that this interest in avoiding physical harm should be taken into account when deciding the residency of a family pet and should take precedence, where appropriate, over the right of an owner to possession of their property. This would be a small, but significant, step to recognising the status of pets at law: property but a unique type of property that requires special treatment. Secondly, strong emotional bonds can develop between the property and its owner. It is the irreplaceability of this special relationship that means that the dispute can’t be resolved by simply buying another pet of the same breed and type. This special relationship should be a relevant consideration in resolving the future residency of the pet and in some cases may prevail over pure property law considerations.

I argue that the unique nature of this property — the fact that it has an interest in not suffering pain and the fact that it has an ability to form special relationships — requires the adoption of a test unique to pet custody disputes: one that fits within the existing property category but nevertheless recognises the special nature of this living and sentient property and consequently permits consideration of factors that do not normally apply to other types of property in family law disputes.

Deborah Rook is a Principal lecturer in Law at the School of Law, Northumbria University and specialises in animal law. She is the author of ‘Who Gets Charlie? The Emergence of Pet Custody Disputes in Family Law: Adapting Theoretical Tools from Child Law’ (available to read for free for a limited time) in the International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family.

The subject matter of the International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family comprises the following: analyses of the law relating to the family which carry an interest beyond the jurisdiction dealt with, or which are of a comparative nature; theoretical analyses of family law; sociological literature concerning the family and legal policy; social policy literature of special interest to law and the family; and literature in related disciplines (medicine, psychology, demography) of special relevance to family law and research findings in the above areas.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What test should the family courts use to resolve pet custody disputes? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorshipHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityPsychodrama, cinema, and Indonesia’s untold genocide

Related StoriesThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorshipHannah Arendt and crimes against humanityPsychodrama, cinema, and Indonesia’s untold genocide

July 4, 2014

Rhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of July

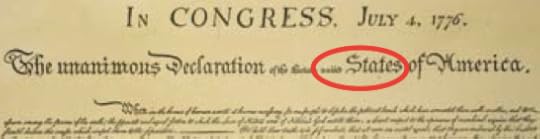

Ever since 4 July 1777 when citizens of Philadelphia celebrated the first anniversary of American independence with a fireworks display, the “rockets’ red glare” has lent a military tinge to this national holiday. But the explosive aspect of the patriots’ resistance was the incendiary propaganda that they spread across the thirteen colonies.

Sam Adams understood the need for a lively barrage of public relations and spin. “We cannot make Events; Our Business is merely to improve them,” he said. Exaggeration was just one of the tricks in the rhetorical arsenal that rebel publicists used to “improve” events. Their satires, lampoons, and exposés amounted to a guerilla war—waged in print—against the Crown.

Cover of Common Sense, the pamphlet. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

While Independence Day is about commemorating the “self-evident truths” of the Declaration of Independence, the path toward separation from England relied on a steady stream of lies, rumor, and accusation. As Philip Freneau, the foremost poet-propagandist of the Revolution put it, if an American “prints some lies, his lies excuse” because the important consideration, indeed perhaps the final consideration, was not veracity but the dissemination of inflammatory material.In place of measured discourse and rational debate, the pyrotechnics of the moment suited “the American crisis”—to invoke the title of Tom Paine’s follow-up to Common Sense—that left little time for polite expression or logical proofs. Propaganda requires speed, not reflection.

Writing became a rushed job. Pamphlets such as Tom Paine’s had an intentionally short fuse. Common Sense says little that’s new about natural rights or government. But what was innovative was the popular rhetorical strategy Paine used to convey those ideas. “As well can the lover forgive the ravisher of his mistress, as the continent forgive the murders of Britain,” he wrote, playing upon the sensational language found in popular seduction novels of the day.

The tenor of patriotic discourse regularly ran toward ribald phrasing. When composing newspaper verses about King George, Freneau took particular delight in rhyming “despot” with “pisspot.” Hardly the lofty stuff associated with reason and powdered wigs, this language better evokes the juvenile humor of The Daily Show.

The skyrockets that will be “bursting in air” this Fourth of July are a vivid reminder of the rhetorical fireworks that galvanized support for the colonists’ bid for independence. The spread of political ideas, whether in a yellowing pamphlet or on Comedy Central, remains a vital part of our national heritage.

Russ Castronovo teaches English and American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His most recent book is Propaganda 1776: Secrets, Leaks, and Revolutionary Communications.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Rhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of July appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

1776, the First Founding, and America’s past in the present

When a nation chooses to celebrate the date of its birth is a decision of paramount significance. Indeed, it is a decision of unparalleled importance for the world’s “First New Nation,” the United States, because it was the first nation to self-consciously write itself into existence with a written Constitution. But a stubborn fact stands out here. This new nation was created in 1787, and the Fourth of July that Americans celebrate today occurred on a different summer eleven years before.

The united States (capitalization, as can be found in the Declaration of Independence, is advised) declared themselves independent on 4 July 1776, but the nation was not yet to be. An act of severance did not a nation make. These united States would only become the United States when the idea of a collective We the People was negotiated and formally set on parchment in the sweltering summer of 1787. This means that while every American celebrates the revolution against government every July 4th, pro-government liberals do not quite have an equivalent red-letter day to celebrate and to mark the equally auspicious revolution in favor of government that transpired in 1787. Perhaps this is why the United States remains exceptional among all developed countries in her half-hearted attitude toward positive liberty, the welfare state, and government regulation on the one hand, and her seeming addiction to guns, individual rights, and negative liberty, on the other. In part because the nation’s greatest national holiday was selected to commemorate severance and not consolidation, (at least half of) America remains frozen in the euphoric tide of the 1770s rather than the more pragmatic, nation-building impulse of the 1780s.

The Fourth of July was only Act One of the creation of the American republic. In the interim years before the nation’s elders (the imprecise but popular nomenclature is “founders”) came together again—this time not to address the curse of the royal yolk, but to discuss the more mundane post-revolutionary crises of interstate conflict especially in matters of trade and debt repayment—the states came to realize that the threat to liberty comes not always from on high by way of royal governors, but also sideways courtesy of newfound friends. In the mid-1780s, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and their compatriots came together to design a more perfect union: a union with the power to lay and collect taxes, to raise and support armies, and an executive to wage war. This was Act Two, or the Second American Founding.

Custom and the convenience of having a bank holiday during the summer when the kids are out of school has hidden the reality of the Two Foundings. We now refer to a single founding, and a set of founders, but this does great injustice to the rich experiential tapestry that helped forge the United States. It denies the very substantive philosophic reasons for why one half of America is so convinced that liberty consists in rejecting government, but one half also thinks that flogging that dead horse with the King long slain seems needlessly self-defeating. As Turgot, the Abbé de Mably, put it in a letter to Dr. Richard Price in 1778, “by striving to prevent imaginary dangers, they have created real ones.” To many Europeans, that the citizens of United States have devoted so much energy—waging even a Civil War—against its own central government and fortifying themselves against it indicates a revolutionary nation in arrested development; a self-contradictory denial that the government of We the People is of, by, and for us.

The United States is thoroughly and still vividly ensconced in the original dilemma of civil society today, whether liberty is best achieved with government or without it. Conservatives and liberals are each so sure that they are the true inheritors of the “founding” because they can point to, respectively, the principles of the First and the Second Foundings to corroborate their account of history. And they will continue to do so for as long as the sacred texts of each of the Two Foundings, the Declaration and the Constitution, stand side by side, seemingly at peace with the other, but in effect in mutual tension.

This Fourth of July, Americans should not despair that the country seems so fundamentally divided on issues from healthcare to Iraq. For if to love is divine, to quarrel is American; and we have been having at it for over two centuries.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and is the author of The Lovers’ Quarrel: The Two Foundings and American Political Development and The Anti-Intellectual Presidency. He blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 1776, the First Founding, and America’s past in the present appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyMapping the American RevolutionWhat can poetry teach us about war?

Calvin Coolidge, unlikely US President

The Fourth of July is a special day for Americans, even for our presidents. Three presidents — John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe — died on the Fourth of July, but only one — Calvin Coolidge — was born on that day (in 1872). Interestingly, Coolidge was perhaps the least likely of any of these to have attained the nation’s highest elective office. He was painfully shy, and he preferred books to people. Nonetheless, he successfully pursued a life in politics, becoming Governor of Massachusetts followed by two years as Warren Harding’s Vice-President. When Harding died of a heart attack, Coolidge became an unlikely president. Perhaps even more unlikely, he became not only an enormously popular one, but also the one whom Ronald Reagan claimed as a model.

Helen Keller with Calvin Coolidge, 1926. National Photo Company Collection. Public domain via Library of Congress.

Coolidge faced more than the usual challenge vice-presidents face when they have ascended to the presidency upon the death of an incumbent. They have not been elected to the presidency in their own right and must somehow secure the support of the American people and other national leaders on a basis other than their own election. Coolidge surprisingly handled this challenge well through his humility, quirky sense of humor, and, perhaps most importantly, integrity. Upon becoming president, Coolidge inherited one of the worst scandals ever to face a chief executive. He quickly agreed to the appointment of two special counsel charged with investigating the corruption with his administration and vowed to support their investigation, regardless of where it lead. Coolidge kept his word, clearing out of the administration any and all of the corruption uncovered within the administration, including removing Harding’s Attorney General. He went further to become the first president to hold as well as to broadcast regular press conferences. His actions won widespread acclaim and eased the way to Coolidge’s easy victory in the 1924 presidential election.Over the course of his presidency, Coolidge either took or approved several initiatives, which have endured and changed the nature of the federal government. He was the first president to authorize federal regulation of aviation and broadcasting. He also signed into law the largest disaster relief authorized by the federal government until Hurricane Katrina. Moreover, he supported the creation of both the World Court and a pact, which sought (ultimately in vain) to outlaw war. Along the way, he became infamous for a razor-sharp sense of humor and peculiar commitment to saying as little as possible (in spite of his constant interaction with the press) and advocating as little regulation of business as possible. His administration became synonymous with the notion that the government that governs best governs least.

Coolidge, nonetheless, has become largely forgotten, partly because of his own choices and partly because of circumstances beyond his control. Just before his reelection, his beloved son died from blood poisoning originating from a blister on his foot. Coolidge never recovered and the presidency lost its luster. By 1928, he had no interest in running again for the presidency or in helping his Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover succeed him in office.

Despite the successes he had in office, including his popularity, Coolidge paid little attention to racial problems and growing poverty during era. When the Great Depression hit, the nation and particularly the next president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, construed it as a reflection of the failed policies and foresight of both Hoover and his predecessor. Despondent over his son’s death, Coolidge did little to protect his legacy and respond to critics throughout the remainder of Hoover’s term. When he died shortly before Franklin Roosevelt’s inauguration, he was largely dismissed or forgotten as a president whose time had come and gone. Nevertheless, on this Fourth of July, do not forget that when conservative leaders deride the growth of the federal government and proclaim the need for less regulation, they harken back not only to President Reagan but also to the man whom Reagan regarded as the model of a conservative leader. Calvin Coolidge’s birthday is as good a time as any to remember that his ideals are alive and well in America.

Michael Gerhardt is Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. A nationally recognized authority on constitutional conflicts, he has testified in several Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and has published five books, including The Forgotten Presidents and The Power of Precedent. Read his previous blog posts on the American presidents.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Calvin Coolidge, unlikely US President appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyWhat can poetry teach us about war?Mapping the American Revolution

Related StoriesJuly 4th and the American Dream in a season of uncertaintyWhat can poetry teach us about war?Mapping the American Revolution

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers