Oxford University Press's Blog, page 789

July 14, 2014

Tracking down a slow loris

Slow lorises are enigmatic nocturnal primates that are notoriously difficult to find in the wild. The five species of slow loris that have been evaluated by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species are classified as threatened or critically endangered with extinction. So, how did one end up recently on the set of Lady Gaga’s music video? Lorises don’t make good pets or video props, especially as they are the world’s only venomous primates. But, unfortunately, it is easier to see a loris as an exotic pet in a Youtube video or on Rihanna’s shoulder as a photo prop than it is to see them in the wild.

In my current research at the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation at the American Museum of Natural History, my team is surveying for Bengal (Nycticebus bengalensis) and pygmy slow lorises (N. pygmaeus) in Vietnam to determine their population status – how many lorises remain across different key sites in Vietnam, and how their current numbers compare to previous surveys. I have written before about the challenges my team has faced searching for these elusive creatures, but this time, I’d like to discuss the broader difficulties of searching for low-density, rare animals, and how knowledge gaps about these creatures can preclude the development of effective management plans for their conservation.

Intensive fieldwork on Vietnam’s primates only began in the mid-1990s, focusing on those species assessed to be the most in danger of extinction, especially gibbons (Nomascus spp.) and colobines such as snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus avunculus), doucs (Pygathrix spp.), and leaf monkeys (Trachypithecus spp.). Comparatively little research to date has focused on species assumed to be common such as the macaques (Macaca spp.) and the nocturnal lorises (Nycticebus spp.). These groups are presumed common because they seem to be able to persist in more diverse habitats including agroforest and regenerating forest, while gibbons, doucs, snub-nosed and leaf monkeys are found in established primary or secondary forests, which are rapidly depleting in Vietnam. As a result of this assumption, very few studies have focused on macaques or lorises in Vietnam and thus, there is very little if any information available to accurately assess their conservation status.

Now that researchers have started collecting data more intensively on slow lorises in Vietnam, we are finding that they are at such low densities that it is difficult to accurately calculate their density with statistical precision. However, as more and more researchers choose to focus on nocturnal, rare mammals like lorises across the globe (from owl monkeys to galagos to colugos), we can synthesize across our efforts to learn from each other, refine our methods, and generate more appropriate statistical models. In addition to continuing our surveys, we also working to raise awareness about threats to slow loris populations in Vietnam, and we are training local forest rangers and researchers to conduct ongoing population monitoring.

Ironically, in this case, there was the least information available about the animals assumed to be the most common. Without fundamental data on population status or distribution, it is difficult to either build effective conservation management plans for slow lorises or attract the federal and private funding necessary to implement such plans. And as such, major conservation actions in the region to date have focused on higher profile primate species, for which there is more information about conservation status. We are finally moving towards having enough scientific information to design a plan of action for improved conservation management of slow loris populations in Vietnam.

In Indonesia, at least 15,000 lorises are trafficked each year for the exotic pet trade. Numbers are not available for Vietnam or other countries in Mainland Southeast Asia, but our work so far suggests that pressure from the trade remains quite high. Our upcoming work in Vietnam, funded by the US National Science Foundation, will expand our research to include social science approaches to better inform policy makers about the underlying social and economic drivers of illicit trade in lorises. You can learn more about what other intrepid loris researchers are doing and how you can help to raise awareness and decrease demand for these endangered animals as exotic pets and photo props.

Dr. Mary Blair is the Assistant Director for Research and Strategic Planning at the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation at the American Museum of Natural History. Her research explores how knowledge of evolutionary processes can inform conservation planning. Her work in Vietnam is supported in part by the Disney Worldwide Conservation Fund and by a US National Science Foundation Science, Engineering, and Education for Sustainability Fellowship under Grant No. NSF-CHE-1313908. Mary has blogged about her work in Vietnam for the Museum’s Fieldwork Journal and for the New York Times, and is the author of Primate Ecology and Conservation. You can follow Mary on Twitter @marye_blair. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) A pygmy slow loris (Nycticebus pygmaeus) at the Endangered Primate Rescue Center in Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam. Photo by Dr. Mary Blair. Do not reproduce without permission. (2) A Bengal slow loris (Nycticebus bengalensis) at the Endangered Primate Rescue Center in Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam. Photo by Nolan Bett, used with permission.

The post Tracking down a slow loris appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRebooting PhilosophyCatching up with Mark Johnson, pain science specialistPractical wisdom and why we need to value it

Related StoriesRebooting PhilosophyCatching up with Mark Johnson, pain science specialistPractical wisdom and why we need to value it

July 13, 2014

Fútbol and faith: the World Cup and Ramadan

As 16 teams reached the knockout stage of the World Cup, the blasts of canons sounded to signal the beginning of Ramadan, the holy month in the Islamic lunar calendar in which Muslims are to abstain from food, drink, smoking, sex, and gossiping from sunrise to sunset. The World Cup offers Muslims an opportunity to celebrate both their faith and fútbol with the world.

Muslim soccer players and Muslim fans inevitably are impacted. Although only two national teams from countries with a significant Muslim population (Algeria and Nigeria) competed in the knockout stage, Muslim players are also representing European nations. Islamic religious leaders have given Muslim athletes permission to abstain from fasting during Ramadan, but it remains the player’s decision.

However, Ramadan involves more than physical deprivation; it is a time of personal spiritual evaluation and renewal. Ramadan is a month of reflection in which Muslims assess their behavior in light of religious teachings with a goal of cultivating religious piety. Hardships Muslims endure during fasting (such as hunger, thirst, desire, etc.) facilitate this internal examination. In their self-reflection, Muslims consider their responsibility to follow God’s will: do good, avoid wrongdoing, strive for social justice, and seek peaceful relations with others. However, in a world filled with distractions, like the World Cup, cultivating these practices is difficult.

Feira de domingo. Curitiba – Paraná. Photo by Gilmar Mattos 2008. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via gijlmar Flickr.

For a small minority of ultra-conservative Muslims, soccer games are considered a “public abomination” that promote cursing, gambling, profiteering, excess partying, and hostility between fans of opposing teams. As a result, Yasser Borhami, a Salafi preacher and leader of the Egyptian al-Daawa Movement claims, “World Cup matches distract Muslims from performing their [religious] duties. They include forbidden things that could break the fast in Ramadan as well as [other forbidden things] in Islam like intolerance and wasting time.”

The vast majority of Muslims, however, reject such a position. Instead, as the Grand Imam of al-Azhar Ahmed al-Tayeb noted in a speech he submitted to World Cup officials at the invitation of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, the games are “an opportunity to spread peace and equality among the people, to transmit feelings of love and brotherhood, to get rid of injustice, evil and discrimination among humanity, to help the weak, the poor, the patient and the underprivileged.” The values that al-Tayeb encouraged World Cup enthusiasts to embody lie at the heart of Ramadan observance.

Brazilian Muslims are taking measures to help Muslim sports fans minimize distractions that might arise during the games (such as breaking fasts, missing prayers, and/or engaging in un-Islamic entertainment) that could hinder this self-analysis. The Federation of Muslims Associations in Brazil (FAMBRAS) printed The Guide – Muslim Fan, a 28-page booklet providing Muslim tourists with essential information about Brazil and Islam. This pamphlet includes a history of Islam in Brazil, embassy addresses of Arab and Islamic countries, and brief city profiles of game locations. Local times for the five daily prayers and addresses of mosques in each area are highlighted. In addition to the booklet, FAMBRAS operates a 12-hour telephone hotline and provides a smartphone app to offer information on halal restaurants and entertainment options. Their efforts are twofold: helping Muslims observe Islam and enjoy the World Cup.

Muslims visiting the World Cup are not alone in facing potential soccer distractions. In the Arab world, the evening hours of Ramadan are prime time for the television industry. Networks are altering programming to accommodate World Cup games broadcast in these time slots. Since kick-off times coincide with peak television viewing hours in the Middle East, Africa, and Europe, FIFA officials anticipate higher viewership for the 2014 World Cup than the 3.2 billion people who tuned in to the 2010 games. The establishment of public viewing centers in countries with large Muslim populations, such as in Indonesia, Nigeria, and Algeria, suggest additional Muslim viewers will watch this year.

Although Muslims watching these games may not overtly discuss religious themes, their friendships and engagement with others over an international sporting event provides a foundation for deeper spiritual reflections. Thus, it’s possible for Muslims to celebrate their love of fûtbol and their faith during Ramadan.

Ramadan Kareem.

Melanie Trexler is a Ph.D. candidate in theological and religious studies at Georgetown University. Originally from Richmond, Kentucky, Melanie completed her B.A. at Furman University where she double-majored in political science and religion. She continued her education at Vanderbilt University, receiving a Masters of Divinity in 2007 before entering Georgetown’s Ph.D. program in theological and religious studies with a focus in religious pluralism. She studies Islam and Christianity, concentrating on Muslim-Christian relations in the United States and in the Arab world.

Oxford Islamic Studies Online is an authoritative, dynamic resource that brings together the best current scholarship in the field for students, scholars, government officials, community groups, and librarians to foster a more accurate and informed understanding of the Islamic world. Oxford Islamic Studies Online features reference content and commentary by renowned scholars in areas such as global Islamic history, concepts, people, practices, politics, and culture, and is regularly updated as new content is commissioned and approved under the guidance of the Editor in Chief, John L. Esposito.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Fútbol and faith: the World Cup and Ramadan appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe first rule of football is… don’t call it soccerFootball arrives in BrazilSongs for the Games

Related StoriesThe first rule of football is… don’t call it soccerFootball arrives in BrazilSongs for the Games

Donor behaviour and the future of humanitarian action

After a short lull in the late 2000s, global refugee numbers have risen dramatically. In 2013, a daily average of 32,200 people (up from 14,200 in 2011) fled conflict and persecution to seek protection elsewhere, within or outside the borders of their own country. On the current trajectory, 2014 will be even worse. In Syria, targeting of civilians and large-scale destruction have led to 2.5 million (and counting) refugees fleeing the country since 2011. The vast majority shelter in neighbouring Lebanon (856,500), Jordan (641,900), and Turkey (609,300). As I write, hundreds of thousands are fleeing the advancing forces of the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) in neighbouring Iraq. And civil wars and ethnic violence have resurged in many parts of Central Africa and the African Horn.

What future for humanitarian action in this dire scenario? This question was raised on the fifth of May by the UN Secretary-General, Ban-Ki Moon, when he launched a programme of global consultations, which will culminate in the first ever World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul in 2016, poised to “set a new agenda for global humanitarian action”. The UN has raised four sets of challenges, to deliver humanitarian aid more efficiently, effectively, innovatively, and robustly.

The launch of these consultations is timely, but it avoids an important challenge to the future of humanitarian action: the policies of donor governments.

At first glance, this may seem like a strange assertion. After all, although needs continue to surpass the ability to provide, donor funding for humanitarian operations has skyrocketed. From less than US$1 billion in 1989, the global humanitarian budget stood at US$22 billion in 2013. Most of these funds come from a small number of Western donor states. But coupled with this rise in funds comes a donor agenda that risks, even if unintentionally, undermining the humanitarian ideal. This challenge is far from the only one posed to humanitarian action — much worse for the security of humanitarian workers are the terrorist groups that target them, leading to the killing of an estimated 152 aid workers in 2013. But because humanitarian action depends on a moral consensus over its meaning and worth, the current trajectory of donor policies is worrisome.

The humanitarian ideal is based on international solidarity: that outsiders can and should provide aid and protection in a principled, non-partisan, needs-based manner to civilian casualties of war and political violence. This ideal of politically disinterested solidarity with fellow human beings caught up in war and violence, regardless of who or where they are, has always been at some remove from the reality of humanitarian operations, but a consensus has nevertheless existed that it is an ideal worth aspiring to. Recently, though, donor governments have been increasingly open and unapologetic about using humanitarian aid to further their own political or security objectives.

One such objective is to keep immigration down. Since most man-made humanitarian crises have displacement as a core component, one objective of Western donor support of humanitarian aid to refugees is to contain population movement. The vast majority of refugees — people who have fled for their lives across international borders — remain within their near region, in camps or regional cities. Only a small proportion attempt the long journey to Europe, Australia, or North America in hope of jobs and a better future. Western humanitarian donors would prefer that even fewer asylum seekers make it to their own shores, while refugee host states in the Global South would like burden-sharing and solidarity to mean more than monetary charity from the well-off to the poorer.

Containment strategies seem to be working. While refugee numbers are increasing overall, including in industrialized states, the proportion of refugees hosted by developing states has grown over the past ten years from 70 percent to 86 percent. In Lebanon, there are 178 Syrian refugees for every thousand Lebanese inhabitants (in Jordan, the number is 88 per thousand). But efforts by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to resettle particularly vulnerable Syrian refugees have had lukewarm responses. This donor attitude of charity from afar coupled with hostility to asylum seekers and unwanted migrants in general, undermines the moral underpinnings of humanitarianism. After all, the Good Samaritan, often put forward as the embodiment of the humanitarian spirit, did not leave a few coins with the battered traveller he found by the wayside. He took him home and nursed him.

Another trend undermining the humanitarian ideal is the increased, and increasingly unapologetic, strategic use of aid to further donors’ own foreign and security policy objectives. There is a clear increase in the past couple of decades in the earmarking of funds and channelling of resources, not necessarily to the neediest of humanitarian victims, but to those deemed more relevant to donor interests. The ‘hearts and minds’ campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s are the starkest representatives of this trend. As US-led intervention forces aimed to win over local populations by disbursing aid, the overall share of US overseas aid channelled through the US Department of Defense rose from 5.6 percent in 2002 to 21.7 percent in 2005.

These donor trends of openly pursuing domestic, foreign, and security policy goals through humanitarian aid are detrimental to the long-term future of humanitarian action, since they undermine the consensus and the ethical values underpinning the humanitarian ideal. While other challenges also loom, the strategies (and strategizing) of donors should have been included as a core topic of the Global Consultations.

Dr Anne Hammerstad, University of Kent, is author of The Rise and Decline of a Global Security Actor: UNHCR, Refugee Protection and Security. She writes and tweets on refugees, humanitarianism, conflict, and security. You can follow her on Twitter at @annehammerstad.

To learn more about refugees, conflict, and how countries are responding, read the Introduction to The Rise and Decline of a Global Security Actor: UNHCR, Refugee Protection and Security, available via Oxford Scholarship Online. Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO) is a vast and rapidly-expanding research library. Launched in 2003 with four subject modules, Oxford Scholarship Online is now available in 20 subject areas and has grown to be one of the leading academic research resources in the world. Oxford Scholarship Online offers full-text access to academic monographs from key disciplines in the humanities, social sciences, science, medicine, and law, providing quick and easy access to award-winning Oxford University Press scholarship.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: United Nations Flags by Tom Page. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Donor behaviour and the future of humanitarian action appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJohn Calvin’s prophetic calling and the memoryWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in QatarThe #BringBackOurGirls rallying point

Related StoriesJohn Calvin’s prophetic calling and the memoryWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in QatarThe #BringBackOurGirls rallying point

The month that changed the world: Monday, 13 July to Sunday, 19 July 1914

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Two weeks after the assassination, by Monday, 13 July, Austria’s hopes of pinning the guilt directly on the Serbian government had evaporated. The judge sent to investigate reported that he had been unable to discover any evidence proving its complicity in the plot. Perhaps the Russian foreign minister was right to dismiss the assassination as having been perpetrated by immature young men acting on their own. Any public relations initiative undertaken by Austria to justify making harsh demands on Serbia would have to rely on its failure to live up to the promises it had made five years ago to exist on good terms with Austria-Hungary.

Few anticipated an international crisis. Entente diplomats remained convinced that Germany would restrain Austria, while the British ambassador in Vienna still regarded Berchtold as ‘peacefully inclined’ and believed that it would be difficult to persuade the emperor to sanction an ‘aggressive course of action’. Triple Alliance diplomats found it difficult to envision a robust response from the Entente powers to any Austrian initiative: the cities of western Russia were plagued by devastating strikes; the possibility of civil war in Ulster loomed as a result of the British government’s home rule bill; the French public was already absorbed by the upcoming murder trial of the wife of a cabinet minister.

Austria and Germany tried to maintain an aura of calm. The chief of the Austrian general staff left for his annual vacation on Monday; the minister of war joined him on Wednesday. The chief of the German general staff continued to take the waters at a spa, while the Kaiser was encouraged not to interrupt his Baltic cruise. But behind the scenes they were resolved to act. On Tuesday Tisza assured the German ambassador that he was now ‘firmly convinced’ of the necessity of war: Austria must seize the opportunity to demonstrate its vitality; together with Germany they would now ‘look the future calmly and firmly in the face’. Berchtold explained to Berlin that the presentation of the ultimatum would be have to be delayed: the president and the premier of France would be visiting Russia on the 20-23 of July, and it was not desirable to have them there, in direct contact with the Russian government, when the demands were made. But Berchtold wanted to assure Germany that this did not indicate any ‘hesitation or uncertainty’ in Vienna. The German chancellor was unwavering in his support: he was determined to stand by Austria even if it meant taking ‘a leap into the dark’.

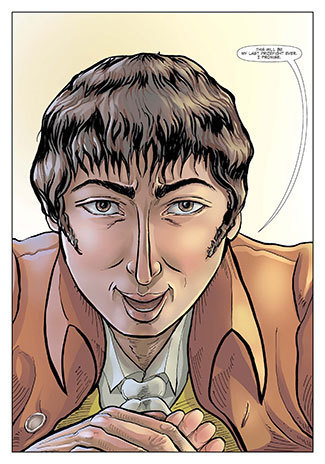

German statesman and diplomat Gottlieb von Jagow

One of the few discordant voices was heard from London, where Prince Lichnowsky was becoming more assertive: he tried to warn Berlin of the consequences of supporting an aggressive Austrian initiative. British opinion had long supported the principle of nationality and their sympathies would ‘turn instantly and impulsively to the Serbs’ if the Austrians resorted to violence. This was not what Berlin wished to hear. Jagow replied that this might be the last opportunity for Austria to deal a death-blow to the ‘menace of a Greater Serbia’. If Austria failed to seize the opportunity its prestige ‘will be finished’, and its status was of vital interest to Germany. He prompted a German businessman to undertake a private mission to London to go around the back of his ambassador.The German chancellor remained hopeful. Bethmann Hollweg believed that Britain and France could be used to restrain Russia from intervening on Serbia’s behalf. But the support of Italy was questionable. In Rome, the Italian foreign minister argued that the Serbian government could not be held responsible for the actions of men who were not even its subjects. Italy could not offer assistance if Austria attempted to suppress the Serbian national struggle by the use of violence – or at least not unless sufficient ‘compensation’ was promised in advance.

From London Lichnowsky continued to insist that a war would neither solve Austria’s Slav problem nor extinguish the Greater Serb movement. There was no hope of detaching Britain from the Entente and Germany faced no imminent danger from Russia. Germany, he complained, was risking everything for ‘mere adventure’.

These warnings fell on deaf ears: instead of reconsidering Germany’s options the chancellor lost his confidence in Lichnowsky. Instead of recognising that Italy would fail to support its allies in a war, the German government pressed Vienna to offer compensation to Italy sufficient to change its mind. By Saturday, the secretary of state was explaining that this was Austria’s last chance for ‘rehabilitation’ and that if it were to fail its standing as a Great Power would disappear forever. The alternative was Russian hegemony in the Balkans – something that Germany could not permit. The greater the determination with which Austria acted, the more likely it was that Russia would remain quiet. Better to act now: in a few years Russia would be prepared to fight, and then ‘she will crush us by the number of her soldiers.’

On Sunday morning the ministers of the Austro-Hungarian common council gathered secretively at Betchtold’s private residence, arriving in unmarked cars. This time there was no controversy. After minimal discussion the terms of the ultimatum to be presented to Serbia were agreed upon. Count Hoyos recorded that the demands were such that no nation ‘that still possessed self- respect and dignity could possibly accept them’. They agreed to present the note containing them in Belgrade between 4 and 5 p.m. on Thursday, the 25th. If Serbia failed to reply positively within 48 hours Austria would begin to mobilize its armed forces.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Gottlieb von Jagow, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 13 July to Sunday, 19 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 27 June 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 27 June 1914

Countries of the World Cup: Germany

Today is the conclusion of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, and our highlights about the final four competing nations with information pulled right from the pages of the latest edition of Oxford’s Atlas of the World. The final two teams, Germany and Argentina, go head-to-head on Sunday, 13 July to determine the champion.

Like many of its European neighbors, Germany is a country that loves football, and is one of the most competitive football-playing nations in the world. Attesting to that is their success in the semi-finals in this year’s Cup. Here are eight interesting facts you might not have known about the country that bruised Brazil’s ego.

Like FIFA host country Brazil, Germany also elected its first female leader in recent years when Angela Merkel became Chancellor in 2005.

In addition to bringing mankind the likes of Albert Einstein and Johan Gutenberg, inventor of the first printing press in Europe, Germany provides 20.6% of the world’s motor vehicles and 17% of our pharmaceuticals.

Uranium was first discovered by a German chemist, Markin Klaproth, in 1789 and boasts the fourth largest industrial output (from mining, manufacturing, construction, and energy) in the world.

Germany had a rough go of things for a while after World War II with its division into East and West factions, as well as the Cold War. The two were reunited on 3 October 1990 and adopted West Germany’s official name, the Federal Republic of Germany.

Deutschland is a leading member of the European Union as well as the 17-member Eurozone, the economic and monetary union of nations that utilize the Euro as their sole form of currency.

In terms of religion, Germany is mostly a Protestant and Roman Catholic country with a representation of 34% of the population.

Although a leading producer of nuclear power (Germany ranks sixth in the world for 4.1% of global production), following the 2011 Fukushima disaster, the country has begun phasing out its nuclear power production.

Germany is a primary refugee destination, ranking first in Europe and fourth in the world after Pakistan, Iran, and Syria.

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The milestone Twentieth Edition is full of crisp, clear cartography of urban areas and virtually uninhabited landscapes around the globe, maps of cities and regions at carefully selected scales that give a striking view of the Earth’s surface, and the most up-to-date census information. The acclaimed resource is not only the best-selling volume of its size and price, but also the benchmark by which all other atlases are measured.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Flag of Germany. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Countries of the World Cup: Germany appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCountries of the World Cup: ArgentinaCountries of the World Cup: BrazilFootball arrives in Brazil

Related StoriesCountries of the World Cup: ArgentinaCountries of the World Cup: BrazilFootball arrives in Brazil

Veils and the choice of society

On 1 July 2014, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights held that France’s ban on wearing full-face veils in public pursued a legitimate aim because it reflected a “choice of society”. Although the Court found that the blanket prohibition amounted to an interference with the religious rights of the minority in France that wore the full-face veil, it was justified because it protected the rights of others to have the option of facial interaction with that minority. The Court accepted that this right of potential facial interaction forms part of the minimum standards of “living together” in French society and outweighs the right of the minority to express their religious beliefs through wearing a full-face veil.

The result of the decision is that ‘SAS’, the applicant Muslim woman in the case, was held not to have suffered a violation of her religious rights under the European Convention on Human Rights. S.A.S. v France is another recent example of the controversies which can arise in the field of law and religion but its significance goes beyond that: the case has given rise to a full and carefully-reasoned judgment from the Strasbourg Court which revisits and, in places, develops its jurisprudence in this difficult area of the law.

The Decision

Article 9 is the principal protection available for religious freedom under the Convention. When examining a potential Article 9 violation, the Strasbourg Court must establish whether the act complained of – in this case, the ban on the veil – interferes with the applicant’s religious rights. If so, the Court will then consider whether or not that interference is: (1) prescribed by law; (2) pursuant to a legitimate aim; and (3) necessary and proportionate in a democratic society.

In S.A.S, the Court found that the ban was prescribed by French law (the Law No. 2010-1192) and constituted an interference with the applicant’s religious beliefs. The critical issues for the Court were whether or not the blanket prohibition was: (i) in pursuit of a legitimate aim; and, if so, (ii) necessary in a democratic society, that is to say, proportionate.

The second paragraph of Article 9 sets out the only legitimate grounds on which religious rights can be interfered with: public safety, public order, health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. The Court dismissed the French Government’s arguments based on public safety, and considered the other three arguments put forward – that the veil fell short of the minimum requirements of life in society; that it harmed equality between men and women; and that it was a manifestation of disrespect for human dignity – under the heading of the ‘rights and freedoms of others’. The Court rejected the dignity and gender equality arguments, and focused on whether the requirements of “living together” could be a legitimate aim. The Court found that they could. The core of its reasoning is at §122 of the judgment:

“[The Court] can understand the view that individuals who are present in places open to all may not wish to see practices or attitudes developing in those places which would call into question the possibility of open interpersonal relationships, which, by virtue of an established consensus, forms an indispensable element of community life within the society in question. The Court is therefore able to accept that the barrier raised against others by a veil concealing the face is perceived by the respondent State as breaching the right of others to live in a space of socialisation which makes living together easier.”

The Court’s assessment of proportionality ultimately came down to the fact that the sanctions were, in the Court’s view, light (albeit criminal) and reflected a choice of society. France’s margin of appreciation in this area was such that it could, and should, make this choice without interference from an international court.

The Dissent

The joint partly dissenting opinion of Judges Nussberger and Jäderblom voiced a number of criticisms of the majority approach, of which the following are an important few:

The concept of ‘living together’ as a right is ‘far-fetched and vague’.

It seems unlikely that the veil itself is at the root of the French ban, rather than the philosophy linked to it. French parliamentary reports revealed that the true concerns are linked to the meaning of the veil: as ‘a form of subservience’, because of its ‘dehumanising violence’, and because of the fact that it represents ‘the self-confinement of any individual who cuts himself off from others whilst living among them’.

The opinion of the majority is wrong to ignore an individual’s right to express herself, or her beliefs, in a way that shocks others. The Court’s mandate is to protect expressions of rights which ‘offend, shock and disturb’, as well as those that are favourably received.

A Group of Women Wearing Burkas. Afghanistan women wait outside a USAID-supported health care clinic. Photo by Nitin Madhav (USAID). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Discussion

Some actions, whether religiously motivated or otherwise, could be so objectively offensive to the operation of society that they require limitation in the name of ‘living together’. However, where the action in question is non-violent and generally without external impact, extreme care must be exercised in establishing why society’s right not to be exposed to an act outweighs the individual’s right to perform it. This is all the more so the case where the action in question is an expression of a religion which, as the judgment acknowledges, can too often be subject to social prejudice.

One of the key difficulties with the opinion of the majority in S.A.S is the extent to which the Strasbourg Court allows ‘society’s choice’ to govern state action where distinctly unpopular rights are threatened. The Convention seeks to establish and to enforce European standards of protection for the rights of every individual. The Convention is an instrument which supports ‘democratic societies’. This is not in the political sense of allowing the dominant collective voice to decide the fate of all; societies are capable of achieving that without assistance. The Convention should ensure that the voices of all groups and individuals in the society – popular or otherwise – are heard, and afforded proportionate weight where state aims threaten individual rights.

As the partly dissenting opinion points out, Western societies are fearful of what the veil connotes. The grounds of argument rejected by the Court were in all likelihood the more honest ones: there was clear social discomfort about a practice which ran counter to ideas of gender equality and human dignity. The Court rightly discounted such arguments where the applicant could show that wearing the veil was a matter of choice. Absent the issue of force, it is simply a question of whether covering the face is so offensive to others that it outweighs the religious importance of the action. Some may well ask whether or not the S.A.S judgment has explained why the alleged social offence caused is more important than the interference with a right which is at the core of international protection.

The majority judgment is significant also for the arguments that the Court rejected. Gender equality was not accepted as a legitimate aim by the Court. This is a shift. In its previous case law on the Islamic headscarf, the Court had stated that “it appears difficult to reconcile the wearing of an Islamic headscarf with the message of tolerance, respect for others and, above all, equality and non-discrimination”: Dahlab v Switzerland; Leyla Sahin v Turkey. The position has changed:

“a State Party cannot invoke gender equality in order to ban a practice that is defended by women […] in the context of the exercise of rights enshrined in those provisions, unless it were to be understood that individuals could be protected on that basis from the exercise of their own fundamental rights and freedoms” (S.A.S., §119).

Similarly, the Court rejected the State’s public safety argument, finding that in the absence of a general threat to public safety, a blanket ban was a disproportionate interference with the applicant’s Article 9 right. That finding is in contrast to the Court’s earlier decision in Mann Singh v France, when the Court accepted France’s restrictions of religious rights on the grounds of public safety without requiring evidence of the necessity of the restriction.

Although this decision accords with the Court’s general approach to the protection of religious dress under Article 9, it significantly shifts the focus onto the choices of individual societies as legitimate restrictions on religious rights. Much attention was given by the Court to the particular consensus of French society as a counterbalance to the identified right of a religious minority; this could represent a considerable enhancement of the scope of the ‘rights and freedoms of others’ limitation under Article 9(2). It remains to be seen how the Strasbourg Court will define the limits of the democratic choice of Member States in future decisions: this is, and will remain, a difficult and developing area of the law.

Can Yeginsu is a barrister at 4 New Square Chambers in London. He is the co-author (with Sir James Dingemans, Tom Cross and Hafsah Masood) of The Protections for Religious Rights: Law and Practice. Jessica Elliott is a barrister at One Crown Office Row Chambers in London.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Veils and the choice of society appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMormon women “bloggers”: a long traditionOK Go: Is the Writing on the Wall?Free speech, reputation, and the Defamation Act 2013

Related StoriesMormon women “bloggers”: a long traditionOK Go: Is the Writing on the Wall?Free speech, reputation, and the Defamation Act 2013

July 12, 2014

Countries of the World Cup: Netherlands

As we gear up for the third place finalist match of the 2014 FIFA World Cup today — the Netherlands face the host country Brazil — we’re highlighting some interesting facts about one of the competing nations with information pulled right from the pages of the latest edition of Oxford’s Atlas of the World. Germany (tomorrow’s country highlight) and Argentina go head-to-head on Sunday, 13 July to determine the champion.

The Netherlands, located in the western end of Northern Europe is widely known for its rich Dutch culture. The population is 83% Dutch, with a smaller percentage made up of Indonesian, Turkish, and Moroccan ethnicities. The nation has two official languages: Frisian, spoken mainly by inhabitants of the northern province of Friesland, and Dutch.

The country has a vast history, dating back earlier than the 16th century when it saw a multitude of foreign rulers including the Romans, the Germanic Franks, the French, and the Spanish. After building up a great overseas empire, the Dutch lost control of the seas to England in the 18th century, and were under French control until 1815. After remaining neutral through World War I, and being occupied by Germany in World War II, they went on after the wars to become active in West European affairs.

In 1957, the Netherlands became a founding member of the European Economic Community, now known as the European Union, and continues to be a leader in industry and commerce. Exports currently account for over 50% of the country’s GDP and include natural gas, machinery and electronic equipment, and chemicals. A highly industrialized country, it is also a major trading nation as it imports many of the materials their industries require.

With a constitutional monarchy, the Netherlands saw its Queen Beatrix abdicate the thrown in 2013 in favor of her son Prince Willem Alexander. She had served a 33-year reign.

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The milestone Twentieth Edition is full of crisp, clear cartography of urban areas and virtually uninhabited landscapes around the globe, maps of cities and regions at carefully selected scales that give a striking view of the Earth’s surface, and the most up-to-date census information. The acclaimed resource is not only the best-selling volume of its size and price, but also the benchmark by which all other atlases are measured.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A panorama of the Erasmus Bridge and the River Meuse in the Dutch city of Rotterdam. Photo by Massimo Catarinella. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Countries of the World Cup: Netherlands appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCountries of the World Cup: BrazilCapitalism doesn’t fall apartFootball arrives in Brazil

Related StoriesCountries of the World Cup: BrazilCapitalism doesn’t fall apartFootball arrives in Brazil

Daniel Mendoza: born on the 4th of July (249 years ago)

This past 5 July was Daniel Mendoza’s 250th birthday. Or was it? Most biographical sources say that Mendoza was born in 1764. The Encyclopedia Britannica, the Encyclopedia Judaica, Chambers Biographical Dictionary, and the Encyclopedia of World Biography all give 1764 for Mendoza’s year of birth, as do the the websites of the International Boxing Hall of Fame, the International Jewish Hall of Fame, WorldCat, and Wikipedia. The blue plaque on the house in Bethnal Green where Mendoza lived states that he was born in 1764. Indeed, Mendoza’s own memoirs claim that he was born on 5 July 1764.

But the records of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue at Bevis Marks in London indicate that Mendoza was actually born in 1765. Thanks to the work of Lewis Edwards, who reported his findings in a lecture to the Jewish Historical Society of England in 1938, and whose paper was subsequently published in the Transactions of that society, we know that the Mendoza was circumcised on 12 July 1765, 249 years ago today. Jewish law requires infant boys to be circumcised on the eighth day after birth, and this would suggest a birth date of 4 July 1765. (Edwards writes that “we must take the date of birth to have been 5 July 1765,” but in that case Mendoza would only have been seven days old when he was circumcised, which would have violated Jewish law.) It would be quite a coincidence if another Daniel Mendoza had been born on 4 July 1765, and our Daniel Mendoza, whose family belonged to the same synagogue, had been missing from the circumcision records of the previous year. It is equally unlikely that Mendoza would have been circumcised at the age (almost exactly) of one year. Moreover, Edwards consulted the records of the Grand Lodge of Freemasons and found that “Daniel Mendoza, tobacconist, of Bethnal Green, aged 22,” was initiated into the society at some time between 29 October 1787 and 12 February 1788. We know from his memoirs that Mendoza had worked in a tobacconist’s shop between 1782 and 1787, and letters he wrote to the newspapers in 1788 gave his address as “Paradise-Row, Bethnal Green.” So it is reasonable to assume that the new initiate was Daniel Mendoza the pugilist.

Is it possible that Mendoza was mistaken about his own birth date? This seems unlikely, since if he knew he was 22 in late 1787 or early 1788 when he registered with the Freemasons, he should have known he was born in 1765. A printer’s error is more likely the cause. One can easily imagine a printer, or an apprentice, switching the type and accidently entering his “5” after “July” and placing his “4” after “176,” thereby changing 4 July 1765 to 5 July 1764. Whatever the reason for the error, once it was made it was bound to be repeated. When reporting on Mendoza’s death in September 1836, the Morning Post wrote that the boxer “had reached his 73rd year,” as did Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, when in fact he died in his 72nd. And the proliferation of this false information in the years following Mendoza’s death made made it “common knowledge.” Despite Edwards’s careful research, most of the people who have written about Mendoza in the last three quarters of a century have repeated the earlier mistake.

Why does any of this matter? What difference does it make if Mendoza was 21 and not 22 when he defeated Martin the Butcher? Probably not much. Am I being pedantic by trying to determine the exact date of Mendoza’s birth? Not entirely. If historians are less than rigorous with details that “don’t matter,” we are likely to be lax when they do matter. Moreover, there is a case to be made that Mendoza’s birth year does matter. After all, we are dealing with a commemoration. The bicentennary of the French Revolution was commemorated in 1989, and any attempt to move it up to 1988 would have been seen as misguided. Similarly, Americans would have balked at the suggestion that they celebrate the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1975 rather than 1976. The birth of a famous boxer is in a different category of world-historical importance, to be sure, but commemoration is commemoration, and it obeys certain rules. Centuries and half-centuries are more important than decades, which take precedence over individual years. How would you feel if you went to celebrate your grandmother’s 100th birthday only to find out when you arrived at the party that she was 99 (and that her birthday was the previous day)? You would wish her well, but somehow it wouldn’t be the same.

Why does any of this matter? What difference does it make if Mendoza was 21 and not 22 when he defeated Martin the Butcher? Probably not much. Am I being pedantic by trying to determine the exact date of Mendoza’s birth? Not entirely. If historians are less than rigorous with details that “don’t matter,” we are likely to be lax when they do matter. Moreover, there is a case to be made that Mendoza’s birth year does matter. After all, we are dealing with a commemoration. The bicentennary of the French Revolution was commemorated in 1989, and any attempt to move it up to 1988 would have been seen as misguided. Similarly, Americans would have balked at the suggestion that they celebrate the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1975 rather than 1976. The birth of a famous boxer is in a different category of world-historical importance, to be sure, but commemoration is commemoration, and it obeys certain rules. Centuries and half-centuries are more important than decades, which take precedence over individual years. How would you feel if you went to celebrate your grandmother’s 100th birthday only to find out when you arrived at the party that she was 99 (and that her birthday was the previous day)? You would wish her well, but somehow it wouldn’t be the same.

So let’s find some fitting way to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Mendoza’s birth, but let’s do it next year, and on the 4th of July.

Ronald Schechter is Associate Professor of History at the College of William and Mary. He is the author of Obstinate Hebrews: Representations of Jews in France, 1715-1815 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003) and translator of Nathan the Wise by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing with Related Documents (Boston and New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004). He is author of the graphic history Mendoza the Jew: Boxing, Manliness, and Nationalism, illustrated by Liz Clarke. His research interests include Jewish, French, British, and German history with a focus on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images from Mendoza the Jew: Boxing, Manliness, and Nationalism, illustrated by Liz Clarke. Do not use without permission.

The post Daniel Mendoza: born on the 4th of July (249 years ago) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWriting a graphic history: Mendoza the JewIllustrating a graphic history: Mendoza the JewCountries of the World Cup: Brazil

Related StoriesWriting a graphic history: Mendoza the JewIllustrating a graphic history: Mendoza the JewCountries of the World Cup: Brazil

Songs for the Games

Behind the victory anthems to be used by the competing teams at the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games, which open on 23 July, lie stories both of nationality and authorship. The coronation of Edward VII in 1902 prompted the music antiquary William Hayman Cummings (1831-1915) to investigate the origin and history of ‘God Save the King’. While the anthem had become ‘a sacred part of our national life’, Cummings could find no reliable trace of single authorship of its words, though concluded that the aptly-named organist and court musician John Bull (1559×63-1628) had the strongest claim to have composed its tune.

What, though, of the anthems of the nations of the United Kingdom, each separately represented at the Commonwealth Games? The national anthem itself was only gradually adopted as such after its first recorded performance in September 1745. Half-a-century later, its standing was sufficiently established to attract subversive parody. ‘God Save Great Thomas Paine’ was penned in 1793 by a Jacobin sympathiser, the Sheffield balladeer Joseph Mather (1737-1804), who was later subject to criminal proceedings which, for a year, prevented him from performing in public. By the late nineteenth century, public performances of ‘God Save the Queen’ itself provoked occasional hostile reactions in Ireland and Wales, as was noted by the encyclopaedist of music Percy Scholes (1877-1958), author of a definitive study (1954) of what he dubbed ‘the world’s first national anthem’. Political nationalism and cultural revivalism, respectively, inspired alternatives.

‘God Save Ireland’ (1867), written by the journalist and MP Timothy Daniel Sullivan (1827-1914), was rapidly adopted as a de facto national anthem. The more militant ‘A Soldier’s Song’ written in 1907 by the Irish revolutionary Peadar Kearney (1883-1942) did not initially catch on – it was said to be difficult to sing – but in the wake of the Easter Rising in 1916, it eclipsed Sullivan’s anthem and was later adopted by the Irish Free State and its successor Republic of Ireland. Remaining within the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland in turn adopted ‘Danny Boy’ (1912), a ballad composed by a west of England barrister and prolific, commercially-successful songwriter Frederic Edward Weatherly (1848-1929) and set to the traditional ‘Londonderry Air’.

‘Land of my fathers’ (‘Hen wlad fy nhadau’), the national anthem of Wales, dates from 1856 when James James [Iago ap Ieuan] (1832-1902), an innkeeper, composed music to accompany words written by his father Evan James [Ieuan ap Iago] (1809-1878), a cloth weaver from Pontypridd. Like other anthems, its adoption was gradual, but its enthusiastic reception by people of Welsh descent around the world signified its status. ‘O land of our birth’, the anthem of the Isle of Man, also represented at the Commonwealth Games, was composed by William Henry Gill (1839-1923) of Manx parentage and education, who spent most of his life as a civil servant resident in the south of England. A Ruskinian folk revivalist, he visited the island at the end of the nineteenth century to collect folk songs, one of which he used for the musical setting of the anthem, first performed in 1907.

The early twentieth century was a fertile period for patriotic song writing, most obviously ‘Land of Hope and Glory’, written in 1902 by the schoolmaster and don Arthur Christopher Benson (1862-1925) as a Coronation Ode to Edward VII, and sometimes proposed as a national anthem for England. Team England will instead use ‘Jerusalem’, whose musical origins lie in the Great War when, in early 1916, at the request of the ‘Fight for Right’ movement which sought to ’brace’ the nation to pursue the war in the face of mounting losses, Sir Hubert Parry (1848-1918) set William Blake’s words to music.

At the Commonwealth Games between 1962 and 2006 Team Scotland used ‘Scotland the Brave’, whose lyrics were written by the Glasgow journalist Cliff Hanley (1922-1999). Recent research has established that they were a product of Hanley’s writing for the variety stage in Glasgow, and were originally performed as a rousing patriotic finale to the first act of a pantomime during the winter of 1952-3. Both the words and music of ‘Flower of Scotland’, the current anthem of Team Scotland, and a leading contender for an official national anthem, were written in about 1964 by Roy Williamson (1936-1990), a former art student in Edinburgh, and a leading figure in the city’s folk music revival. By 1990 hostility to the playing of ‘God Save the Queen’ at rugby internationals when England played Scotland at Murrayfield, Edinburgh, prompted the Scottish Rugby Football Union to seek a more acceptable sporting anthem. The choice of ‘Flower of Scotland’, with its echoes of Bannockburn, heralded a memorable Scottish rugby victory over England that year.

A musical acknowledgement of the multi-national basis of the United Kingdom awoke early morning listeners to BBC Radio 4 for nearly thirty years at the end of the twentieth century. The day’s broadcasts began with ‘UK Theme’, a medley of tunes representing the constituent parts of the United Kingdom, including Rule Britannia, Scotland the Brave, Men of Harlech, and the Londonderry Air, composed and conducted by Fritz Spiegl (1926-2003), an Austrian refugee from Nazism. It was removed from the schedule in 2006.

Dr Mark Curthoys is the Oxford DNB’s Research Editor for the nineteenth and twentieth century.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is a collection of 59,102 life stories of noteworthy Britons, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Oxford DNB is freely available via public libraries across the UK, and many libraries worldwide. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to gain access free, from home (or any other computer), 24 hours a day. You can also sample the ODNB with its changing selection of free content: in addition to the podcast; a topical Life of the Day, and historical people in the news via Twitter @odnb.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Union Jack face paint on girl, by Nathanx1, via iStock Photo.

The post Songs for the Games appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800How much do you know about the First World War?John Calvin’s prophetic calling and the memory

Related StoriesEnglish convent lives in exile, 1540-1800How much do you know about the First World War?John Calvin’s prophetic calling and the memory

Rebooting Philosophy

When we use a computer, its performance seems to degrade progressively. This is not a mere impression. An old version of Firefox, the free Web browser, was infamous for its “memory leaks”: it would consume increasing amounts of memory to the detriment of other programs. Bugs in the software actually do slow down the system. We all know what the solution is: reboot. We restart the computer, the memory is reset, and the performance is restored, until the bugs slow it down again.

Philosophy is a bit like a computer with a memory leak. It starts well, dealing with significant and serious issues that matter to anyone. Yet, in time, its very success slows it down. Philosophy begins to care more about philosophers’ questions than philosophical ones, consuming increasing amount of intellectual attention. Scholasticism is the ultimate freezing of the system, the equivalent of Windows’ “blue screen of death”; so many resources are devoted to internal issues that no external input can be processed anymore, and the system stops. The world may be undergoing a revolution, but the philosophical discourse remains detached and utterly oblivious. Time to reboot the system.

Philosophical “rebooting” moments are rare. They are usually prompted by major transformations in the surrounding reality. Since the nineties, I have been arguing that we are witnessing one of those moments. It now seems obvious, even to the most conservative person, that we are experiencing a turning point in our history. The information revolution is profoundly changing every aspect of our lives, quickly and relentlessly. The list is known but worth recalling: education and entertainment, communication and commerce, love and hate, politics and conflicts, culture and health, … feel free to add your preferred topics; they are all transformed by technologies that have the recording and processing of information as their core functions. Meanwhile, philosophy is degrading into self-referential discussions on irrelevancies.

The result of a philosophical rebooting today can only be beneficial. Digital technologies are not just tools merely modifying how we deal with the world, like the wheel or the engine. They are above all formatting systems, which increasingly affect how we understand the world, how we relate to it, how we see ourselves, and how we interact with each other.

The ‘Fourth Revolution’ betrays what I believe to be one of the topics that deserves our full intellectual attention today. The idea is quite simple. Three scientific revolutions have had great impact on how we see ourselves. In changing our understanding of the external world they also modified our self-understanding. After the Copernican revolution, the heliocentric cosmology displaced the Earth and hence humanity from the centre of the universe. The Darwinian revolution showed that all species of life have evolved over time from common ancestors through natural selection, thus displacing humanity from the centre of the biological kingdom. And following Freud, we acknowledge nowadays that the mind is also unconscious. So we are not immobile, at the centre of the universe, we are not unnaturally separate and diverse from the rest of the animal kingdom, and we are very far from being minds entirely transparent to ourselves. One may easily question the value of this classic picture. After all, Freud was the first to interpret these three revolutions as part of a single process of reassessment of human nature and his perspective was blatantly self-serving. But replace Freud with cognitive science or neuroscience, and we can still find the framework useful to explain our strong impression that something very significant and profound has recently happened to our self-understanding.

Since the fifties, computer science and digital technologies have been changing our conception of who we are. In many respects, we are discovering that we are not standalone entities, but rather interconnected informational agents, sharing with other biological agents and engineered artefacts a global environment ultimately made of information, the infosphere. If we need a champion for the fourth revolution this should definitely be Alan Turing.

The fourth revolution offers a historical opportunity to rethink our exceptionalism in at least two ways. Our intelligent behaviour is confronted by the smart behaviour of engineered artefacts, which can be adaptively more successful in the infosphere. Our free behaviour is confronted by the predictability and manipulability of our choices, and by the development of artificial autonomy. Digital technologies sometimes seem to know more about our wishes than we do. We need philosophy to make sense of the radical changes brought about by the information revolution. And we need it to be at its best, for the difficulties we are facing are challenging. Clearly, we need to reboot philosophy now.

Luciano Floridi is Professor of Philosophy and Ethics of Information at the University of Oxford, Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute, and Fellow of St Cross College, Oxford. He was recently appointed as ethics advisor to Google. His most recent book is The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Alan Turing Statue at Bletchley Park. By Ian Petticrew. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Rebooting Philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOK Go: Is the Writing on the Wall?Scenes from the Odyssey in Ancient ArtFree speech, reputation, and the Defamation Act 2013

Related StoriesOK Go: Is the Writing on the Wall?Scenes from the Odyssey in Ancient ArtFree speech, reputation, and the Defamation Act 2013

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers