Oxford University Press's Blog, page 786

July 20, 2014

The month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

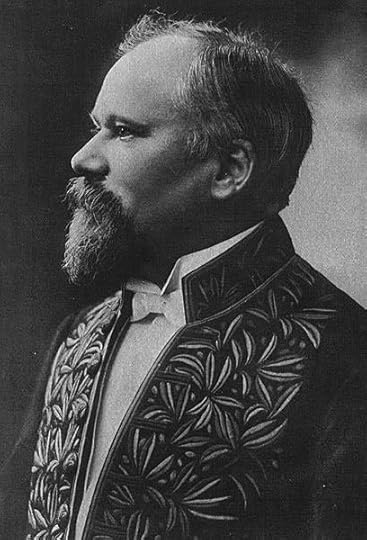

The French delegation, led by President Raymond Poincaré and the premier/foreign minister René Viviani, finally arrived in Russia. They boarded the imperial yacht, the Alexandria, while a Russian band played the ‘Marseillaise’ – that revolutionary ode to the destruction of royal and aristocratic privilege. The tsar and his foreign minister welcomed the visitors before they travelled to Peterhof where a spectacular banquet awaited them.

While the leaders of republican France and tsarist Russia were proclaiming their mutual admiration for one another, the Habsburg emperor was approving the terms of the ultimatum to be presented to Serbia three days later. No one was to be forewarned, not even their allies: Italy was to be told on Wednesday only that a note would be presented on Thursday; Germany was not to be given the details of the ultimatum until Friday – along with everyone else.

In London, Sir Edward Grey remained in the dark. He was optimistic; he told the German ambassador on Monday that a peaceful solution would be reached. It was obvious that Austria was going to make demands on Serbia, including guarantees for the future, but Grey believed that everything depended on the form of the demands, whether the Austrians would exercise moderation, and whether the accusations of Serb government complicity were convincing. If Austria kept its demands within ‘reasonable limits’ and if the necessary justification was provided, it ought to be possible to prevent a breach of the peace; ‘that any of them should be dragged into a war by Serbia would be detestable’.

Raymond Poincaré, President of France, public domain

On Tuesday the Germans complained that the Austrians were keeping them in the dark. From Berlin, the Austrian ambassador offered Berchtold his ‘humble opinion’ that the Germans ought to be given the details of the ultimatum immediately. After all, the Kaiser ‘and all the others in high offices’ had loyally promised their support from the first; to treat Germany in the same manner as all the other powers ‘might give offence’. Berchtold agreed to give the German ambassador a copy of the ultimatum that evening; the details should arrive at the Wilhelmstrasse by Wednesday.That same day the French visitors arrived in St Petersburg, where the mayor offered the president bread and salt – according to an old Slavic custom – and Poincaré laid a wreath on the tomb of Alexander III ‘the father’ of the Franco-Russian alliance. In the afternoon they travelled to the Winter Palace for a diplomatic levee. Along the route they were greeted by enthusiastic crowds: ‘The police had arranged it all. At every street corner a group of poor wretches cheered loudly under the eye of a policeman.’ Another spectacular banquet was held that evening, this time at the French embassy.

Perhaps the presence of the French emboldened the Russians. The foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov, warned the German ambassador that he perceived ‘powerful and dangerous influences’ might plunge Austria into war. He blamed the Austrians for the agitation in Bosnia, which arose from their misgovernment of the province. Now there were those who wanted to take advantage of the assassination to annihilate Serbia. But Russia could not look on indifferently while Serbia was humiliated, and Russia was not alone: they were now taking the situation very seriously in Paris and London.

But stern warnings in St Petersburg were not repeated elsewhere. In Vienna the French ambassador believed as late as Wednesday that Russia would not take an active part in the dispute and would try to localize it. The Russian ambassador there was so confident of a peaceful resolution that he left for his vacation that afternoon. The Russian ambassador in Berlin had already left for vacation and had yet to return; the French ambassador there returned on Thursday. The British ambassador was also absent and Grey saw no need to send him back to Berlin.

In Rome however, San Giuliano had no doubt that Austria was carefully drafting demands that could not be accepted by Serbia. He no longer believed that Franz Joseph would act as a moderating influence. The Austrian government was now determined to crush Serbia and seemed to believe that Russia would stand by and allow Serbia to ‘be violated’. Germany, he predicted, ‘would make no effort’ to restrain Austria.

By Thursday, 23 July, twenty-five days had passed since the assassination. Twenty-five days of rumours, speculations, discussions, half-truths, and hypothetical scenarios. Would the Austrian investigation into the crime prove that the instigators were directed from or supported by the government in Belgrade? Would the Serbian government assist in rooting out any individuals or organizations that may have provided assistance to the conspirators? Would Austria’s demands be limited to steps to ensure that the perpetrators would be brought to justice and such outrages be prevented from recurring in the future? Or would the assassination be utilized as a pretext for dismembering, crushing or abolishing the independence of Serbia as a state? Was Germany restraining Austria or goading it to act? Would Russia stand with Serbia in resisting Austrian demands? Would France encourage Russia to respond with restraint or push it forward? Would Italy stick with her alliance partners, stand aside, or join the other side? Could Britain promote a peaceful resolution by refusing to commit to either side in the dispute, or could it hope to counterbalance the Triple Alliance only by acting in partnership with its friends in the entente? At last, at least some of these questions were about to be answered.

At ‘the striking of the clock’ at 6 p.m. on Thursday evening the Austrian note was presented in Belgrade to the prime minister’s deputy, the chain-smoking Lazar Paču, who immediately arranged to see the Russian minister to beg for Russia’s help. Even a quick glance at the demands made in the note convinced the Serbian Crown Prince that he could not possibly accept them. The chief of the general staff and his deputy were recalled from their vacations; all divisional commanders were summoned to their posts; railway authorities were alerted that mobilization might be declared; regiments on the northern frontier were instructed to prepare assembly points for an impending mobilization. What would become the most famous diplomatic crisis in history had finally begun.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Raymond Poincaré, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 13 July to Sunday, 19 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 13 July to Sunday, 19 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 29 June to Sunday, 5 July 1914

Hobby Lobby and the First Amendment

The recent Hobby Lobby decision, which ruled that corporations with certain religious beliefs were no longer required to provide insurance that covers contraception for their female employees — as mandated by Obamacare — hinged on a curious piece of legislation from 1993. In a law that was unanimously passed by Congress and signed by President Clinton, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) stated that “Government shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion.” The intention of RFRA was to offer an opportunity for religious people to challenge ordinary laws, state or federal, that had some adverse impact on their faith. The RFRA was a direct response to a case three years earlier, when the Supreme Court decided that laws that applied to everybody were acceptable even if they burdened a religious community. RFRA was Congress’ scream of protest to the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence.

By passing the RFRA in 1993, Congress was trying to steal the Supreme Court’s thunder. It was not fixing physical infrastructures; it was fixing a fellow branch of government. It was not over-ruling what it considered to be a faulty judicial reading of its own statutes; it was changing an interpretation of the Constitution itself. But isn’t the Court, for better or worse, the ultimate authority on the First Amendment? Didn’t the principle of separation of powers prevent the legislative branch from amending, by mere majority vote within its own chambers, the Constitution as understood by the justices at any given time?

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, US Supreme Court Justice. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States. Photographer: Steve Petteway. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Indeed, the Supreme Court went on to strike down RFRA in 1997, but only in part. It ruled that the states were not covered by RFRA’s change, but that the federal government was. This provided the opening for the Hobby Lobby decision, where several for-profit closely held corporations sought to defeat a federal regulation about contraception that applied generally to businesses, but offended their own belief systems.

Most discussion of Hobby Lobby, including even Justice Ginsburg’s dissent, has flexibly adapted to the idea that RFRA is constitutional, despite its extraordinary usurpation of judicial power. Her dissent correctly points out that her colleagues in the majority go even further than Congress in permitting religious belief to trump democratically passed legislation. Yes: the majority went much too far in holding that a corporation can “believe” anything or that free exercise rights are violated even when the central beliefs or practices of the religious are not directly implicated; but far worse was its acceptance, without discussion, of Congress’s power grab under RFRA. And the dissents doubled down on that departure from firm and fine traditions we call separation of powers.

Two examples of flexibility, however otherwise opposed, do not add up to the uncompromising defense of our Constitution needed at all times and perhaps especially now. The Supreme Court needed intransigently to re-assert its own power as a separate branch of government. Hobby Lobby’s attempt to veto part of Obamacare that offended its “corporate faith” would and should have been shut down immediately. Our Constitutional system of checks and balances required a clear statement. The Court, on both sides of Hobby Lobby, gave us the ambiguities that muddy the waters when compromise replaces principle.

Richard H. Weisberg, professor of Constitutional Law at Cardozo Law School, is the author of In Praise of Intransigence: The Perils of Flexibility.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Hobby Lobby and the First Amendment appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat are most important issues in international criminal justice today?Donor behaviour and the future of humanitarian actionWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in Qatar

Related StoriesWhat are most important issues in international criminal justice today?Donor behaviour and the future of humanitarian actionWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in Qatar

Why we don’t go to the moon anymore

Today marks the forty-fifth anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing. To understand Apollo’s place in history, it might be helpful to go back forty-four rather than forty-five years, to the very first anniversary of the event in 1970. That July, several newspapers conducted informal surveys that revealed large majorities of Americans could no longer remember the name of Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon. This does not mean they forgot the event — few who watched it ever forgot the event — but it suggests that we need to reconsider what Apollo meant to Americans at the time, and what it can tell us about the history of the 1960s and 1970s.

Dave Eggers’s new novel, Your Fathers, Where Are They? And the Prophets, Do They Live Forever?, opens with a disturbed man peppering an astronaut he has kidnapped with questions about why the United States has not revisited the moon since the early 1970s. America, Eggers’s protagonist complains, is not living up to its promise — a failure seen clearly in its betrayal of the space program. This is a common complaint among the many Americans who yearn to return to an aggressive program of human exploration, and to whom it makes no sense that the United States called it quits after the Apollo program ended in 1972.

The truth is, sending men to the moon in 1969 did not make sense to a majority of Americans in the first place, let alone continuing with an ambitious effort to send astronauts on to Mars or permanent space colonies, as advocates urged. In fact, with the exception of a brief period following Apollo 11, poll after poll in the late 1960s revealed a public that disapproved of the high cost of the moon race, the rush to complete it before 1970, and the misplaced priorities it represented. Beneath all the celebratory rhetoric and vague notions that Apollo somehow changed everything was a realization that it really had not changed much at all. It certainly did not inaugurate any “new era” in history, as many assumed it would. Instead, Americans grew indifferent to the program shortly after the first landing, as the rapid dismissal of Armstrong from the national consciousness indicated. In 1970, the final three planned Apollo missions — what would have been Apollos 18, 19, and 20 — were cancelled, and few Americans complained.

What happened? Why didn’t Apollo even complete its original plan of ten moon landings, let alone fundamentally alter history? There are some obvious reasons. The Cold War, Apollo’s original impetus, had eased considerably by the late 1960s, and with the moon race won there was little interest in continuing an expensive crash program of exploration. There were also more pressing social issues (and a divisive war) to deal with at the time, eroding NASA’s budget and scuttling any ambitious post-Apollo agenda.

But there is another significant reason why human space exploration not only waned after Apollo but also why Apollo itself failed to have the impact most expected it would: cultural changes in the late 1960s undermined interest in the kind of progress Apollo symbolized. By 1969, the Space Age values that were associated with Apollo — faith in rational progress, optimism that science and technology would continue to propel the nation toward an ever brighter future — were being challenged not just by a growing skepticism of technology, which was expressed throughout popular and intellectual culture, but by a broader anti-rationalist backlash that first emerged in the counterculture before becoming mainstream by the early 1970s.

Space advocates in the 1970s envisioned a near future of Mars missions and permanent space colonies, like the one pictured here. With public and political support dwindling, however, NASA had to settle for the technologically impressive but much less ambitious shuttle program. Courtesy NASA Ames Research Center.

This anti-rationalism, and its penetration into mainstream culture, can be seen in the reaction to Apollo of one well-known American: Charles Lindbergh. Life — the magazine of Middle America — in 1969 asked Lindbergh to pen a reflection on Apollo. He refused, and instead sent a letter that Life published in which he claimed he no longer believed rationality was the proper path to understanding the universe. “In instinct rather than intellect lay the cosmic plan of life,” he wrote, anticipating not further space travel of the Apollo variety, but, in language reminiscent of the mystical ending of the contemporaneous 2001: A Space Odyssey, “voyages inconceivable by our 20th century rationality . . . through peripheries untouched by time and space.” “Will we discover that only without spaceships can we reach the galaxies?” he asked in closing, and his answer was yes: “To venture beyond the fantastic accomplishments of this physically fantastic age, sensory perception must combine with the extrasensory. . . . I believe it is through sensing and thinking about such concepts that great adventures of the future will be found.”

Lindbergh was far from alone with these sentiments, as evidenced by the overwhelmingly positive letters to the editor they drew. American culture by 1969 was moving away from the rationality that undergirded the Apollo missions, as Americans began investing more importance in non-rational perspectives — in religion and mysticism, mystery and magic; in meditation or ecstatic prayer rather than in shooting men to the moon; in journeys of personal discovery over journeys to other planets. Apollo was thrilling to most who watched it, but it failed to offer sufficient deeper meaning in a culture that was beginning to eschew the rationalist version of progress it represented.

So, why didn’t Apollo make a bigger splash? Why did it mark the end of an era of human exploration rather than the beginning? In short, “the Sixties” happened, and the space program has never recovered. It is entirely possible that, when viewed from its 100th or (if we last so long) 1000th anniversary, Apollo will indeed be considered the beginning of a space-faring era that is yet to come. In the meantime, understanding the retreat away from the Space Age’s rationalist culture not only helps us understand what happened to the space program after Apollo, but also what happened to the United States in that maelstrom we call “the Sixties.”

Matthew Tribbe is a Visiting Assistant Professor of History at the University of Connecticut, and the author of No Requiem for the Space Age: The Apollo Moon Landings and American Culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why we don’t go to the moon anymore appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn the anniversary of air conditioningFrailty and creativitySame-sex marriage now and then

Related StoriesOn the anniversary of air conditioningFrailty and creativitySame-sex marriage now and then

What is consciousness?

The philosopher Descartes set out to escape doubt and to find certainties. From the premise that he was thinking, even if falsely, he argued to what he took to be the certain conclusion that he existed. Cogito ergo sum. He is as well known for concluding that consciousness is not physical. Your being conscious right now is not an objective physical fact. It has a nature quite unlike that of the chair you are sitting on. Your consciousness is different in kind from objectively physical neural states and events in your head.

This mind-body dualism persists. It is not only a belief or attitude in religion or spirituality. It is concealed in standard cognitive science or computerism. The fundamental attraction of dualism is that we are convinced, since we have a hold on it, that consciousness is different. There really is a difference in kind between you and the chair you are sitting on, not a factitious difference.

But there is an awful difficulty. Consciousness has physical effects. Arms move because of desires, bullets come out of guns because of intentions. How could such indubitably physical events have causes that are not physical at all, for a start not in space?

Some philosophers used to accomodate the fact that movements have physical causes by saying conscious desires and intentions aren’t themselves causal but they go along with brain events. Epiphenomenalism is true. Conscious beliefs themselves do not explain your stepping out of the way of joggers. But epiphenomenalism is now believed only in remote parts of Australia, where the sun is very hot. I know only one epiphenomenalist in London, sometimes seen among the good atheists in Conway Hall.

A decent theory or analysis of consciousness will also have the recommendation of answering a clear question. It will proceed from an adequate initial clarification of a subject. The present great divergence in theories of consciousness is mainly owed to people talking about different things. Some include what others call the unconscious mind.

Crystal mind By Nevit Dilmen (Own work) CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

But there are also the criteria for a good theory. We have two already — a good theory will make consciousness different and it will make consciousness itself effective. In fact consciousness is to us not just different, but mysterious, more than elusive. It is such that philosopher Colin McGinn has said before now that we humans have no more chance of understanding it than a chimp has of doing quantum mechanics.There’s a lot to the new theory of Actualism, starting with a clarification of ordinary consciousness in the primary or core sense as something called actual consciousness. Think along with me just of one good piece of the theory. Think of one part or side or group of elements of ordinary consciousness. Think of consciousness in ordinary perception — say seeing — as against consciousness in just thinking and wanting. Call it perceptual consciousness. What is it for you to perceptually conscious now, as we say, of the room you’re in? Being aware of it, not thinking about it or something in it? Well, the fact is not some internal thing about you. It’s for a room to exist.

It’s for a piece of a subjective physical world to exist out there in space — yours. That is something dependent both on the objective physical world out there and also on you neurally. A subjective physical world’s being dependent on something in you, of course, doesn’t take it out of space out there or deprive it of other counterparts of the characteristics you can assemble of the objective physical world. What is actual with perceptual consciousness is not a representation of a world — stuff called sense data or qualia or mental paint — whatever is the case with cognitive and affective consciousness.

That’s just a good start on Actualism. It makes consciousness different. It doesn’t reduce consciousness to something that has no effects. It also involves a large fact of subjectivity, indeed of what you can call individuality or personal identity, even living a life. One more criterion of a good theory is naturalism — being true to science. It is also philosophy, which is greater concentration on the logic of ordinary intelligence, thinking about facts rather than getting them. Actualism also helps a little with human standing, that motive of believers in free will as against determinism.

Ted Honderich is Grote Professor Emeritus of the Philosophy of Mind and Logic at University College London. He edited The Oxford Companion to Philosophy and has written about determinism and freedom, social ends and political means, and even himself in Philosopher: A Kind of Life. He recently published Actual Consciousness.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What is consciousness? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA question of consciousnessApproaching peak skepticismCertainty and authority

Related StoriesA question of consciousnessApproaching peak skepticismCertainty and authority

July 19, 2014

What is the Islamic state and its prospects?

The What Everyone Needs to Know (WENTK) series offers a balanced and authoritative primer on complex current event issues and countries. Written by leading authorities in their given fields, in a concise question-and-answer format, inquiring minds soon learn essential knowledge to engage with the issues that matter today. Starting this July, OUPblog will publish a WENTK blog post monthly.

By James Gelvin

ISIS—now just the “Islamic State” (IS)–is the latest incarnation of the jihadi movement in Iraq. The first incarnation of that movement, Tawhid wal-Jihad, was founded in 2003-4 by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Al-Zarqawi was not an Iraqi: as his name denotes, he came from Zarqa in Jordan. He was responsible for establishing a group affiliated with al-Qaeda in response to the American invasion of Iraq. Over time, this particular group began to evolve as it took on alliances with other jihadi groups, with non-jihadi groups, and as it separated from groups with which it had been aligned. Tawhid wal-Jihad thus evolved into al-Qaeda in Iraq, which had strained relations with “al-Qaeda central.” These strains were caused by the same factors that have created strains between IS and al-Qaeda central. Zarqawi had adopted the tactic of sparking a sectarian war in Iraq by blowing up the Golden Mosque in Samarra, thus instigating Shi’i retaliations against Iraq’s Sunni community, which, in turn, would get mobilized, radicalized, and strike back, joining al-Qaeda’s jihad

What this demonstrates is a long term problem al-Qaeda central has had with its affiliates. Al-Qaeda has always been extraordinarily weak on organization and extraordinarily strong on ideology, which is the glue that holds the organization together.

The ideology of al-Qaeda can be broken down into two parts: First, the Islamic world is at war with a transnational Crusader-Zionist alliance and it is that alliance–the “far enemy”–and not the individual despots who rule the Muslim world–the “near enemy”–which is Islam’s true enemy and which should be the target of al-Qaeda’s jihad. Second, al-Qaeda believes that the state system that has been imposed on the Muslim world was part of a conspiracy hatched by the Crusader-Zionist alliance to keep the Muslim world weak and divided. Therefore, state boundaries are to be ignored.

These two points, then, are the foundation for the al-Qaeda philosophy. It is the philosophy in which Zarqawi believed and it is also the philosophy in which the current head of IS, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, believes as well.

Islamic states (dark green), states where Islam is the official religion (light green), secular states (blue) and other (orange), among countries with Muslim majority. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

We don’t know much about al-Baghdadi. We know his name is a lie–he was not born in Baghdad, as his name denotes, but rather in Samarra. We know he was born in 1971 and has some sort of degree from Baghdad University. We also know he was imprisoned by the Americans in Camp Bucca in Iraq. It may have been there that he was radicalized, or perhaps upon making the acquaintance of al-Zarqawi.

Over time, al-Qaeda in Iraq evolved into the Islamic State of Iraq which, in turn, evolved into the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. This took place in 2012 when Baghdadi claimed that an already existing al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra, was, in fact, part of his organization. This was unacceptable to the head of Jabhat al-Nusra, Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani. Al-Jawlani took the dispute to Ayman al-Zawahiri who ruled in his favor. Zawahiri declared Jabhat al-Nusra to be the true al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, ordered al-Baghdadi to return to Iraq, and when al-Baghdadi refused al-Zawahiri severed ties with him and his organization.

There is a certain irony in this, inasmuch as Jabhat al-Nusra does not adhere to the al-Qaeda ideology, which is the only thing that holds the organization together. On the other hand, IS, for the most part does, although al-Qaeda purists believe al-Baghdadi jumped the gun when he declared a caliphate in Syria and Iraq with himself as caliph—a move that is as likely to split the al-Qaeda/jihadi movement as it is to unify it under a single leader. Whereas al-Baghdadi believes there should be no national boundaries dividing Syria and Iraq, al-Jawlani restricts his group’s activities to Syria. Whereas the goals of al-Baghdadi (and al-Qaeda) are much broader than bringing down an individual despot, Jabhat al-Nusra’s goal is the removal of Bashar al-Assad. And whereas al-Baghdadi (and al-Qaeda) believe in a strict, salafist interpretation of Islamic law, Jabhat al-Nusra has taken a much more temperate position in the territories it controls. The enforcement of a strict interpretation of Islamic law–from the veiling of women to the prohibition of alcohol and cigarettes to the use of hudud punishments and even crucifixions—has made IS extremely unpopular wherever it has established itself in Syria.

The recent strategy of IS has been to reestablish a caliphate, starting with the (oil-rich) territory stretching from Raqqa to as far south in Iraq as they can go. This is a strategy evolved out of al-Qaeda first articulated by Abu Musab al-Suri. For al-Suri (who believed 9/11 was a mistake), al-Qaeda’s next step was to create “emirates” in un-policed frontier areas of the Muslim world from which an al-Qaeda affiliate might “vex and exhaust” the enemy. For al-Qaeda, this would be the intermediate step that will eventually lead to a unification of the entire Muslim world. What would happen next was never made clear—Al-Qaeda has always been more definitive about what it is against rather than what it is for.

IS has demonstrated in the recent period that it is capable of dramatic military moves, particularly when it is assisted by professional military officers, such as the former Baathist officers who planned the attack on Mosul. This represents a potential problem for IS: After all, the jailors are unlikely to remain in a coalition with those they jailed after they accomplish an immediate goal. But this is not the limit of IS’s problems. Mao Zedong once wrote that in order to have an effective guerrilla organization you have to “swim like the fish in the sea”–in other words, you have to make yourself popular with the local inhabitants of an area who you wish to control and who are necessary to feed and protect you. Wherever it has taken over, IS has proved itself to be extraordinarily unpopular. The only reason IS was able to move as rapidly as it did was because the Iraqi army simply melted away rather than risking their lives for the immensely unpopular government of Nouri al-Maliki.

However it scored its victory, it should be remembered that taking territory is very different from holding territory. It should also be remembered that by taking and attempting to hold territory in Iraq, ISIS has concentrated itself and set itself up as a target.

IS has other problems as well. It is fighting on multiple fronts. In Syria, it is battling most of the rest of the opposition movement. It is also a surprisingly small organization–8,000-10,000 fighters (although recent victories might enable it to attract new recruits). The Americans used 80,000 troops in its initial invasion of Iraq in 2003 and was still unable to control the country. In addition, we should not forget the ease with which the French ousted similar groups from Timbuktu and other areas in northern Mali last year. As battle-hardened as the press claims them to be, groups like IS are no match for a professional army.

Portions of this article ran in a translated interview on Tasnim News.

James L. Gelvin is a Professor of History at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is the author of The Arab Uprisings: What Everyone Needs to Know, The Modern Middle East: A History and The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War.

The What Everyone Needs to Know (WENTK) series offers concise, clear, and balanced primers on the important issues of our time. From politics and religion to science and world history, each book is written by a leading authority in their given field. The clearly laid out question-and-answer format provides a thorough outline, making this acclaimed series essential for readers who want to be in the know on the essential issues of today’s world. Find out what you need to know with OUPblog and the WENTK series every month by RSS or email.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What is the Islamic state and its prospects? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFelipe VI, Spain’s new king: viva el reyEight facts about the gun debate in the United StatesCan we end poverty?

Related StoriesFelipe VI, Spain’s new king: viva el reyEight facts about the gun debate in the United StatesCan we end poverty?

Contested sites on India’s Deccan Plateau

Power and memory combined to produce the Deccan Plateau’s built landscape. Beyond the region’s capital cities, such as Bijapur, Vijayanagara, or Golconda, the culture of smaller, fortified strongholds both on the plains and in the hills provides a fascinating insight into its history. These smaller centers saw very high levels of conflict between 1300 and 1600, especially during the turbulent sixteenth century when gunpowder technology had become widespread in the region. Below is a selection of images of architecture and monuments, examined through a mix of methodologies (history, art history, and archaeology), taken from our new book Power, Memory, and Architecture: Contested Sites on India’s Deccan Plateau, 1300-1600.

Raichur. Kati Darwaza gateway (as reconstructed c. 1520)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

When an important fort changed hands in the early modern Deccan, victors often gave its gates “face-lifts” to publicize their possession of the site. When Krishna Raya of Vijayanagara seized Raichur from Bijapur, he erased features of this gate that were associated with Bijapur and stamped it with architectural markings of his own dynasty.

Yadgir Fort, Cannon no. 4 (late 1550s)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In the mid-16th century the sultanate of Bijapur made notable advances in gunpowder technology, marking in some respects a local “Military Revolution”. This is seen in the crude adaptation of the idea of small swivel cannons to very large guns that were placed on high bastions and could be maneuvered both laterally and vertically.

Hyderabad: southern portal of the Char Kaman ensemble (1592)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Though conventionally thought to have been patterned on “Islamic” models of urban design, Hyderabad was actually modeled on the Kakatiya capital of Warangal, indicating that dynasty’s lasting memory. Thus, four portals were positioned around the famous Charminar just as four toranas had been positioned around Warangal’s cultic center, the Svayambhu Shiva temple (see first image).

Warangal Fort: Panchaliraya temple, assembled by Shitab Khan (16th c.)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In 1504 Shitab Khan, an upstart local chieftain, seized the city of Warangal from its Bahmani governor and at once associated himself with the memory of the illustrious Kakatiya dynasty, which had ruled from this city two centuries earlier. To this end, he made several architectural interventions, including assembling this temple from reused structural elements dating to Kakatiya rule.

Bijapur: Inner courtyard of citadel’s gateway

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Like their Vijayanagara rivals to the south, the sultans of Bijapur also revered the memory of the imperial Chalukyas. This is seen in the twenty-four reused Chalukya columns that, in the early 16th century, they inserted in the citadel’s entrance courtyard, their capital’s most prominent site.

Vijayanagara: two-storeyed hall at the end of Virupaksha bazaar

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

To identify themselves with Chalukya glory, rulers of Vijayanagara in the 16th century inserted into this hall’s lower storey finely polished reused Chalukya columns, carved from blue-green schist. By contrast, the hall’s less visible upper storey exhibits columns in the style of Vijayanagara’s own period, crudely carved from nearby granite.

Kuruvatti. Bracket figure from the Malikarjuna temple, ca. 11th c.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Just as the memory of Roman imperial splendor inspired Europeans for centuries after the collapse of Rome, the memory of the Deccan’s prestigious Chalukya dynasty (10th-12th c.), preserved by material remains such as this stunning sculpture, inspired actors four or five centuries later to identify their own regimes with Chalukya glory.

Warangal fort: Remains of the Tughluq congregational mosque

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Architecture and power are interwoven in the remains of this mosque, built in the former capital of the Kakatiya dynasty. Foreground: rubble of the temple of the Kakatiyas’ state deity, Svayambhu Shiva, destroyed in the early 14th century by armies of the Delhi Sultanate. Background: one of the temple’s four majestic gateways (torana) that the conquerors preserved in order to frame the mosque.

Richard M. Eaton is Professor of History at the University of Arizona, Tucson. Phillip B. Wagoner is Professor of Art History at Wesleyan University. They are authors of Power, Memory, Architecture: Contested Sites on India’s Deccan Plateau, 1300-1600.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Contested sites on India’s Deccan Plateau appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesScenes from the Odyssey in Ancient ArtSame-sex marriage now and thenWindow into the last unknown place in New York City

Related StoriesScenes from the Odyssey in Ancient ArtSame-sex marriage now and thenWindow into the last unknown place in New York City

Getting to know Product Marketer Erin McAuliffe

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into work in our offices around the globe, so we are excited to bring you an interview with Erin McAuliffe, a Product Marketing Coordinator for Oxford’s online products. We spoke to Erin about her life here at Oxford University Press — which includes marketing a range of digital resources including Oxford Bibliographies, Oxford Islamic Studies Online, Oxford Competition Law, and more.

What is the most important lesson you learned during your first year on the job?

To be flexible when relying on others. I am a little bit of a control freak so learning to go with the flow was a challenge.

When did you start working at OUP?

I was an intern on the Online Product Marketing team during the Summer of 2010 and then returned as a full-time employee on the same team one year later in June 2011.

Erin McAuliffe, Marketing Coordinator, at her desk in the New York office.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

When all my meetings are over and I can sit down and check projects off my to-do list! Or when I finish a to-do list!

What’s the least enjoyable?

9:00 a.m. conference call meetings.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

Four different pictures of Ryan Gosling and a cheeseburger mouse pad.

What was your first job in publishing?

This one!

What are you reading right now?

The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd; it’s just okay.

What’s your favorite book?

This is impossible to answer but my favorite book that I have read recently was Columbine which is a non-fiction book written by journalist Dave Cullen who covered the Columbine shooting and its impact on the community and families over the next 12 years. It was the most honest, heartbreaking, and complex book I’ve read in a long time.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

Probably working for a media or ad agency.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Put my lunch in the fridge and then scan Internet news while my email loads.

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

I will be coding the public page update of Oxford Bibliographies. I had to teach myself HTML when I started working here and now I love it. It’s cathartic and systematic and you get to be creative.

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

Probably Barack Obama. I think having that much responsibility and pressure would put a lot of things I worry about in perspective.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

A book, some sunscreen, and a regenerating frozen drink cooler.

What is the most exciting project you have been part of while working at OUP?

Probably the creation of an interactive author map for Oxford Bibliographies. It was a project that I thought of, got approved, and executed in a short amount of time and it was something completely new and different for OUP and for the online products.

What is your favorite word?

What is in your desk drawer?

Shoes, A Fondue Set, a stockpile of napkins, and a large amount of blank USBs.

Most obscure talent or hobby?

I can juggle, though not very well.

Longest book ever read?

IT by Stephen King, a little over 1100 pages. Close second is World Without End by Ken Follet which I think is just under 1100 pages.

Erin McAuliffe is Global Product Marketing Coordinator, Digital at Oxford University Press. She works across a range of online products including Oxford Bibliographies, Oxford Islamic Studies Online, Oxford Competition Law, and more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Getting to know Product Marketer Erin McAuliffe appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCatching up with Alyssa BenderPreparing for BIALL 2014Living in a buzzworld

Related StoriesCatching up with Alyssa BenderPreparing for BIALL 2014Living in a buzzworld

Animals could help reveal why humans fall for illusions

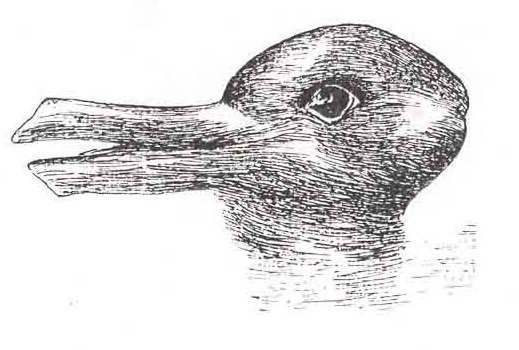

Visual illusions, such as the rabbit-duck (shown below) and café wall are fascinating because they remind us of the discrepancy between perception and reality. But our knowledge of such illusions has been largely limited to studying humans.

That is now changing. There is mounting evidence that other animals can fall prey to the same illusions. Understanding whether these illusions arise in different brains could help us understand how evolution shapes visual perception.

For neuroscientists and psychologists, illusions not only reveal how visual scenes are interpreted and mentally reconstructed, they also highlight constraints in our perception. They can take hundreds of different forms and can affect our perception of size, motion, colour, brightness, 3D form and much more.

Artists, architects and designers have used illusions for centuries to distort our perception. Some of the most common types of illusory percepts are those that affect the impression of size, length, or distance. For example, Ancient Greek architects designed columns for buildings so that they tapered and narrowed towards the top, creating the impression of a taller building when viewed from the ground. This type of illusion is called forced perspective, commonly used in ornamental gardens and stage design to make scenes appear larger or smaller.

As visual processing needs to be both rapid and generally accurate, the brain constantly uses shortcuts and makes assumptions about the world that can, in some cases, be misleading. For example, the brain uses assumptions and the visual information surrounding an object (such as light level and presence of shadows) to adjust the perception of colour accordingly.

Known as colour constancy, this perceptual process can be illustrated by the illusion of the coloured tiles. Both squares with asterisks are of the same colour, but the square on top of the cube in direct light appears brown whereas the square on the side in shadow appears orange, because the brain adjusts colour perception based on light conditions.

These illusions are the result of visual processes shaped by evolution. Using that process may have been once beneficial (or still is), but it also allows our brains to be tricked. If it happens to humans, then it might happen to other animals too. And, if animals are tricked by the same illusions, then perhaps revealing why a different evolutionary path leads to the same visual process might help us understand why evolution favours this development.

The idea that animal colouration might appear illusory was raised more than 100 years ago by American artist and naturalist Abbott Thayer and his son Gerald. Thayer was aware of the “optical tricks” used by artists and he argued that animal colouration could similarly create special effects, allowing animals with gaudy colouration to apparently become invisible.

In a recent review of animal illusions (and other sensory forms of manipulation), we found evidence in support of Thayer’s original ideas. Although the evidence is only recently emerging, it seems, like humans, animals can perceive and create a range of visual illusions.

Animals use visual signals (such as their colour patterns) for many purposes, including finding a mate and avoiding being eaten. Illusions can play a role in many of these scenarios.

Great bowerbirds could be the ultimate illusory artists. For example, their males construct forced perspective illusions to make them more attractive to mates. Similar to Greek architects, this illusion may affect the female’s perception of size.

Animals may also change their perceived size by changing their social surroundings. Female fiddler crabs prefer to mate with large-clawed males. When a male has two smaller clawed males on either side of him he is more attractive to a female (because he looks relatively larger) than if he was surrounded by two larger clawed males.

This effect is known as the Ebbinghaus illusion, and suggests that males may easily manipulate their perceived attractiveness by surrounding themselves with less attractive rivals. However, there is not yet any evidence that male fiddler crabs actively move to court near smaller males.

We still know very little about how non-human animals process visual information so the perceptual effects of many illusions remains untested. There is variation among species in terms of how illusions are perceived, highlighting that every species occupies its own unique perceptual world with different sets of rules and constraints. But the 19th Century physiologist Johannes Purkinje was onto something when he said: “Deceptions of the senses are the truths of perception.”

In the past 50 years, scientists have become aware that the sensory abilities of animals can be radically different from our own. Visual illusions (and those in the non-visual senses) are a crucial tool for determining what perceptual assumptions animals make about the world around them.

Laura Kelley is a research fellow at the University of Cambridge and Jennifer Kelley is a Research Associate at the University of Western Australia. They are the co-authors of the paper ‘Animal visual illusion and confusion: the importance of a perceptual perspective‘, published in the journal Behavioural Ecology.

Bringing together significant work on all aspects of the subject, Behavioral Ecology is broad-based and covers both empirical and theoretical approaches. Studies on the whole range of behaving organisms, including plants, invertebrates, vertebrates, and humans, are welcomed.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Duck-Rabbit illusion, by Jastrow, J. (1899). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.<

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

The post Animals could help reveal why humans fall for illusions appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInequalities in life satisfaction in early old ageOK Go: Is the Writing on the Wall?You can save lives and money

Related StoriesInequalities in life satisfaction in early old ageOK Go: Is the Writing on the Wall?You can save lives and money

July 18, 2014

In remembrance of Elaine Stritch

Oxford University Press is saddened to hear of the passing of Broadway legend Elaine Stritch. We’d like to present a brief extract from Eddie Shapiro’s interview with Elaine Stritch in November/December 2008 in Nothing Like a Dame that illustrates her tremendous life and vitality.

“What’s this all about, again?!” came Elaine Stritch’s unmistakable rattle of a voice, part Rosalind Russell, part dry martini, part cheese grater, on the other end of the phone. I was taken aback. After all, we had spoken the day before and the day before that. On the first call, she had told me that she was swamped but really wanted to get this interview out of the way. “Well,” I had offered, “there’s no great rush. I would rather you do this when you feel relaxed than when you are cramming it in.” “Don’t you worry about my disposition,” came the steely reply. “I’ll worry about my disposition.” She hated me, I thought, until the second call, during which she called me “dear” and apologized twice for her schedule. So now, on call number three, when it seemed we were back at square one, I didn’t know what to say. “Well, it’s the interview for my book, Nothing Like a Dame,” I explained. “You asked me to call today.” “And when did you want to do this,” came the deliberate reply. “Well, you asked me about today.” “Today? I can’t possibly do today.” “That’s fine. It’s just that when you called me on Friday, you said you wanted to get it done this weekend.” “I don’t recall saying that to anyone. Gee, Ed, I hate to leave you hanging like this. How about Thanksgiving?” “Thanksgiving Day?” “Yeah, before dinner. You could come for tea.” “That would be fine.” “But I tell you what, give me a call on Wednesday night after 11:00, just to confirm. And I promise I’ll remember.” And that is how I ended up having tea with irascible, cantankerous, outspoken, and utterly charming Elaine Stritch at The Carlyle Hotel on Thanksgiving Day.

Elaine Stritch was born outside of Detroit in 1925. She came to New York to study under Erwin Piscator at The New School, where her classmates included Marlon Brando and Bea Arthur (with whom she’d compete for a Tony Award sixty years later. And win.). She made her musical debut in Angel in the Wings, singing the absurd “Bongo, Bongo, Bongo (I Don’t Want to Leave the Congo)” before her long run as Ethel Merman’s understudy in Call Me Madam. Since Merman never missed a performance, Stritch never went on, and felt safe simultaneously taking a one-scene part in the hit 1952 revival of Pal Joey a block away. “I was close if they needed me,” she says, “which they never did.” When Call Me Madam went out on national tour, though, Stritch, all of twenty-five, was leading the company. Goldilocks followed, before Noel Coward wrote the role of Mimi Paragon in Sail Away just for Stritch. Mimi, like her inspiration, knew her way around an arched eyebrow and a sarcastic bon mot. Not surprisingly, Stritch was a sensation. It nonetheless took almost a decade for her next Broadway musical, but this one was legendary.

Elaine Stritch in her dressing room at the Savoy Theatre, London. 1973. Photo by Allan Warren, via WikiCommons.

As Joanne in Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s Company, Stritch bellowed the searing eleven o’clock number, “The Ladies Who Lunch.” To this day, it is considered one of the all-time greatest interpretations of any musical theater song. Hal Prince’s acclaimed 1994 revival of Show Boat was another triumph but the best was still to come. In 2001, under the direction of George C. Wolfe, Stritch premiered Elaine Stritch at Liberty, an autobiographical one-woman show in which Stritch gossiped, confessed, kvetched, cajoled, and reveled in a musical tour of her life and career. For At Liberty, she finally took home a Tony Award, before playing the show for years in New York, London, and on tour. In 2010, she successfully, if improbably, succeeded Angela Lansbury in A Little Night Music.

Of all the women in [Nothing Like a Dame], she was the only one I was scared to meet. The phone calls didn’t assuage my fears, nor did the Carlyle’s waiter who, upon hearing I was there to meet Stritch laughingly said, “Good luck!” But I needn’t have worried. Stritch isn’t mean, she’s just blunt to a degree that’s so unusual it’s occasionally unnerving. As Bebe Neuwirth says of her, “She doesn’t know how to lie, on or offstage.” And she doesn’t suffer fools well. But once she trusts, she’s delightful. And warm enough to have extended an invitation to Thanksgiving dinner.

…

In your show, Elaine Stritch: At Liberty, you said that you didn’t know why you wanted to be an actress. But you did choose to pursue acting over anything else. What gave you the instinct that you’d be any good?

I don’t think it’s an instinct, I don’t think that’s the right word. I don’t have an answer to that today.

Calling?

Those are all two-dollar words. I don’t believe in all of that, “calling” and “career.” I wasn’t thinking about . . . I think if I was really dead-honest, I was . . . everybody else was going away to college and I didn’t want to. I don’t know the reason why that was, either. I thought I’d rather learn by experience all of the subjects they were going to teach me in college. That’s a dumb statement. But I didn’t want to go to college. I wanted to be an actress but I still can’t tell you why. I think I’m . . . I don’t think I’m really a happy camper inside and I think it’s an escape for me. I’ve gotten to like myself a lot better as the years go by, but I’m still not hung up on myself.

You have actually said that it’s really hard for you to play yourself. During Elaine Stritch: At Liberty, you said that a vacation would be putting on a costume and playing someone else.

At the time I was doing Elaine Stritch: At Liberty I wasn’t thinking about philosophizing my position and what I would or wouldn’t like to do. This was a tremendously courageous thing for me to do, but it was good. Just like I read a good play—I read a Tennessee Williams play, an Edward Albee play—I read what I wrote and what John Lahr wrote and I liked it. I thought, “This is a good part for me.” That sounds like a joke but it was a good part for me to play. It was the first time I had an opportunity to put myself on the stage. Because I am a really true-blue actress. When I take on a part I play the part. Of course I bring Elaine Stritch to it, that’s why they hire me. But I am interpreting another, I am inside somebody else’s skin. So, you know, acting is . . . I don’t know what it is. I don’t think it’s given enough credit in the arts. I think it’s a real art form, acting. I don’t know. I don’t think a lot of people have the talent—my kind of talent—to be an actress. But there are a lot of good ones out there. I am always so thrilled when I go to the theater and see a performance. I just think that’s the best. There was a marvelous expression in the Times the other day in the review of Australia. They talked about all of the epic qualities of the movie but they said a very simple thing about Nicole Kidman, who I think is a very good actress. They said: “she gave a performance.” And I thought, “what a wonderful notice.” I hope she appreciates it.

I want to go back to your early days, you came to New York for whatever reason you . . .

For whatever reason. Look, it’s not as complicated as all that. I was not going steady with someone. My beau had already gone to New York to become an actor. He was a writer named James Lee. He wrote [the play] Career and he also wrote for television; he was one of the writers on Roots. So what was I gonna do? I didn’t want to go to college. I wasn’t in love. I mean, I loved Jimmy but I wasn’t interested in getting married. I wish it would stop there. I wanted to become an actress. Why? I don’t know. I think you deal with that better than I deal with it. I’d like to be able to answer it better. But I do think that I wasn’t too hung up on myself and I wanted to be everybody else I could think of.

The reason I used the word “instinct” is because I think sometimes people have a desire or gut feeling that isn’t calculated, but they know that something speaks to them.

Something stirring.

Yeah.

I see what you mean. Yes. And I also wanted out of Michigan. I love Michigan but I didn’t want to spend all my life there, I wanted to see the world. Another answer I’ve given to the question, “why did you want to become an actress” is that I wanted higher ceilings. It’s as good an answer as any. I once played a game at a party and we all had to give the best answer for “why did you become an actor.” Mine was, “to get a good table at 21.” Ho ho ho. I think “higher ceilings” would have won at that party but I hadn’t thought of that yet. [The actor] Marti Stevens gave the best answer ever. Actually, the question was, “why did you go on the stage” and Marti Stevens said, “to get out of the audience.” That’s a great answer.

Once you were in New York and at The New School, how did you get work and audition?

I was going to school.

Yes, but you were cast in Loco pretty quickly after school. Did that seem like a fluke to you or were your peers also getting work easily? Did it feel like a struggle?

I don’t know.

Did you have to work for money?

I waited tables at The New School, but I did it not because I needed the money; I did it for the experience.

The human experience?

Yeah.

Did it work?

Yeah. And I did it to show off to Marlon Brando.

Did that work?

Yeah. I was showing that I wasn’t just this rich girl from Michigan. I could be a waitress, too. You see there’s a little Joan Crawford/Mildred Pierce in all of us! It was all of those things. . . . I am very honest about things like that today. Then I wasn’t.

In what ways are you honest now that you were not then?

Well, I wish I could have laughed and told Marlon Brando that I was trying to influence him. But you don’t do that at seventeen. You wait ’til you’re in your eighties ’til you get that kind of honesty. I think I could do a lot of things today that I couldn’t do then as far as being straight- forward and on the level with people. I figured it out that none of us have anything to hide. There’s nothing about me that I couldn’t tell everybody in the world. There really isn’t. And that’s a good way to be. I love the expression “secrets are dangerous.” I really think they are. “Don’t tell anybody, but . . .” is the most boring line in the world. It really is. If you don’t want them to tell anybody, don’t tell them!

In saying secrets are dangerous, do you mean that the truth frees you?

Absolutely. And I think what has transpired without your knowing it is that you kind of, at last, dig yourself.

…

I need a Judy Garland story.

I’d have to look ’em up, Honey.

For people like me, it’s like sitting at my grandmother’s lap and listening to family legend.

I know, I know. Judy Garland, when she came to the opening night party of Sail Away, I made up my mind not to drink at all at that party. There were a lot of famous people there. Before I knew it I saw Judy leaving the Noel Coward suite, and she was going home. I thought, “My God, I haven’t talked to her, she hasn’t told me how she liked the show, and I really want to hear what she thought more than anyone.” They had those see-through elevators at the Savoy Hotel. I ran out to the hall and she was just on the elevator and it was starting to disappear. And before her head got out of view from me, she went, “Elaine, about your fucking timing . . . ” and then she disappeared. It was absolutely brilliant. She knew what she was doing! Her timing was divine! And music to my ears, of course.

Do you have any stories about working with George Abbott on Call Me Madam?

Oh, he was a marvelous director, a wonderful man and an extraordinary human being. I loved him. He did one great thing once with me. When I came down to get notes before opening night, I had a scotch and soda in a coffee mug. Of course I was making it very believable. ’Cause while he was giving the notes I was blowing on the coffee. I was blowing on the scotch. And all of sudden George Abbott said to me, “Can I have a taste of that Elaine? Is that coffee?” And my voice went up two octaves and I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Could I have a taste?” And I said, “Sure.” I’ll tell you what a great guy he was. He took the coffee mug from me and he blew on it and then he took a sip. And then he handed it back to me and said, “Man that’s good coffee.”

Do you have Richard Rodgers stories?

Oh, I loved him. But he didn’t like me. He was an alcoholic, you know, and alcoholics resent other alcoholics. He paid me a great compliment once, though. He said, “I would give her the lead in a show but I just don’t think she could handle it. Because when she does a number, it is so good that I never think she can do it again.” It’s a great compliment but it isn’t very conducive to working.

It is a back-handed compliment.

Well he was a back-handed kind of fellow. He is a hard person to talk about.

Did you think it was personal?

Oh no, he liked me very much. But I made him nervous because I drank. That would make any director or producer—but the funny thing with him was that he drank twice as much as I did.

Did he recognize that?

No, he didn’t at all.

Both Abbott and Rodgers knew that you were drinking . . .

It never bothered George Abbott because I didn’t drink too much. Well, I probably did drink too much, but I was never drunk on the stage in my life.

Was drinking in the theater more commonplace in general?

Absolutely. Everybody had booze in their dressing room. Nobody does anymore. In London, in the theater you have cocktail parties at intermission. It’s a big deal having a little sherry or a little of this or that. But too many people have abused the privilege in this country. All of our great actors were huge drinkers. Tallulah Bankhead, John Barrymore, Bela Lugosi. So many. Lots and lots of people.

The people you mention famously got seriously drunk. That was never you, though.

No, absolutely not. Maybe a couple of times my timing was off because I had three instead of two drinks, but nothing to write home about.

…

Do you read reviews?

Oh yes, I can’t wait. Terrified to read them and thrilled to death when they are good. I haven’t gotten a lot of bad reviews; I’ve gotten a few in my life but nothing that upset me terribly.

There are a lot of actors who . . .

I can’t believe that they don’t read their reviews.

Do you go to the theater today?

Yeah, I go. But I am not going to see The Little Mermaid if that’s what you mean. I like Jane Krakowski, I think she’s good. And I like Kristin Chenoweth. I’m getting very excited about the opening of Pal Joey because my good friend Stockard Channing is in it. The theater is not what it was. It’s the fabulous invalid. It’s having a tough time because of the economy but it will come back. I worry about Maxwell [her nephew, a twenty-nine-year-old actor who just moved to New York]. Nobody who comes here to get into the theater can get an agent. It takes years. You have to go on those cattle calls. This is a tough racket. It really is a tough racket.

…

If performing hadn’t worked out for you, do you have any notion of what you might have been doing?

Supposition is really boring but I’ll give it a shot: Stay home!!

Is there anyone you’ve never worked with who you wish you had?

If I am supposed to, it’ll happen. I reiterate: supposition to me is a long yawn.

I think the word is “boring.”

[Laughs] OK, whatever you think is fair.

Excerpted from Nothing Like a Dame: Conversations with the Great Women of Musical Theater by Eddie Shapiro. Shapiro is a freelance writer and theater journalist whose work has appeared in Out Magazine, Instinct, and Backstage West. He is the author of Queens in the Kingdom: The Ultimate Gay and Lesbian Guide to the Disney Theme Parks.

The post In remembrance of Elaine Stritch appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLiving in a buzzworldElectronic publications in a Mexican universityCertainty and authority

Related StoriesLiving in a buzzworldElectronic publications in a Mexican universityCertainty and authority

Is the past a foreign country?

My card-carrying North London media brother, Ben, describes himself on his Twitter feed as a ‘recovering Northerner’.

In my case the disease is almost certainly incurable. Despite spending a good deal of last year in cosmopolitan London — beautiful, exciting and diverse as it is — I found myself on occasions near tears of joy as my feet hit the platform at King’s Cross.

“I need to know I can be at the coast or in miles of open countryside within 20 minutes,” I told Ben.

“I need to know I can get Vietnamese food at 3.00 a.m.,” he replied.

While mine is clearly the healthier individual craving, the gulf in population health outcomes between the North and South of England, or, perhaps more accurately, between the provinces and the capital and its South Eastern sprawl, remains as wide as ever.

On examining the distribution of age-standardised mortality for Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics regions, the United Kingdom remains the most starkly unequal of European nations. This is starkly illustrated in our new analyses of the North South divide in England, when compared with the experience of East and West Germany following the fall of the Berlin Wall. After that great political upheaval, notably for women, life expectancy in East Germany began to climb rapidly. Twenty years on, it is indistinguishable from that of the former West Germany.

In contrast, the gap between the North East of England and London, which in 1990 was similar to that between East and West Germany, remains just as wide in the most recent figures. Of course, life expectancy has risen markedly in both countries and their regions; modern North East English life expectancy is significantly higher than that which obtained in 1990 for West Germany. But the English failure to narrow its inequality gap despite overt national efforts signals that those efforts are simply too light-touch to be effective.

As Johan Mackenbach has commented, in reflecting on the English strategy from 1997-2010:

“it did not address the most relevant entry-points, did not use effective policies and was not delivered at a large enough scale for achieving population-wide impacts. Health inequalities can only be reduced substantially if governments have a democratic mandate to make the necessary policy changes, if demonstrably effective policies can be developed, and if these policies are implemented on the scale needed to reach the overall targets.”

Of course, fundamental to this problem is economics. The wealth of London and the South East in comparison to, well just about anywhere else in the UK, is now extraordinarily stark. London now feels more alien to my Northern sensibilities than much of Europe, and the reason is not people but cash.

The difference is illustrated rather well by the contrasting artistic expectations of the South Bank Centre — close by the Waterloo offices of Public Health England, for whom I worked last year — and the Culture budget of the City of Newcastle — for whom I now work as Director of Public Health.

On consecutive days in 2013, the Guardian and BBC reported the Southbank Centre’s unveiling of its £100m redevelopment plans (6 March), having made a successful first stage bid for £20m from the Arts Council, and Newcastle City Council was reported (7 March) as having cut its £2.5m culture budget by 50%. This comparison could equally be drawn in many other ways: for transport and infrastructure, investment in business, development of academic institutions (why did the Crick Institute need to be in King’s Cross?). And it all matters because, despite the cleaner air and wide open spaces, the English provinces and in particular the North, are losing out — on culture, mobility, urban environment, jobs, and crucially on health.

The English North has many charms, both for its natives and many who come upon its joys by accident (see this delightful, recent New York Times piece). For too many, however, it remains a place of shorter and poorer lives. The German experience suggests that it need not be so.

Prof. Eugene Milne became Director of Public Health for Newcastle upon Tyne earlier this year, after working nationally for Public Health England as Director for Adult Health and Wellbeing. He is an Honorary Professor in Medicine and Health at the University of Durham, and joint-editor, with his colleague Prof. Ted Schrecker, of the Journal of Public Health. He has research interests in health improvement, inequalities and ageing.

The Journal of Public Health invites submission of papers on any aspect of public health research and practice. We welcome papers on the theory and practice of the whole spectrum of public health across the domains of health improvement, health protection and service improvement, with a particular focus on the translation of science into action. Papers on the role of public health ethics and law are welcome.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Angel of the North, Gateshead, by NickyHall5. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is the past a foreign country? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInequalities in life satisfaction in early old ageYou can save lives and moneyHow to prevent workplace cancer

Related StoriesInequalities in life satisfaction in early old ageYou can save lives and moneyHow to prevent workplace cancer

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers