Oxford University Press's Blog, page 782

July 30, 2014

On the 95th anniversary of the Chicago Race Riots

On 27 July 1919, a black boy swam across an invisible line in the water. “By common consent and custom,” an imaginary line extending out across Lake Michigan from Chicago’s 29th Street separated the area where blacks were permitted to swim from where whites swam. Seventeen-year-old Eugene Williams crossed that line. He may have strayed across it by accident or may have challenged it on purpose. We do not know his motives because the whites on the beach reacted by throwing stones and Eugene Williams drowned. Police at the beach arrested black bystanders, infuriating other blacks so much that one black man shot at the police, who returned fire, shooting into the crowd of blacks. The violence spread from there. Over the next week, in the middle of that hot summer of 1919, 38 people died, 537 were hospitalized, and approximately 1,000 were left homeless. White and black Chicagoans fought over access to beaches, parks, streetcars, and especially residential space. The burning of houses, during this riot, inflamed passions almost as much as the killing of people. It took a rainstorm and the state militia to end the violence in July 1919, which nevertheless simmered just below the surface, erupting in smaller clashes between blacks and whites throughout the next four decades, especially every May, during Chicago’s traditional moving season.

Family leaving damaged home after 1919 Chicago race riot by Chicago Commission on Race Relations. Negro in Chicago: The Negro in Chicago; a study of race relations and a race riot (1922). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The 1910s were the first decade of the Great Migration, a decade when 70,000 blacks had moved to Chicago, more than doubling the existing black population. This was also a decade when the lines of Chicago’s residential apartheid were hardening. Historically, Chicago’s blacks found homes in industrial suburbs such as Maywood and Chicago Heights, domestic service hubs such as Evanston and Glencoe, rustic owner-built suburbs such as Robbins and Dixmoor, and some recently-annexed suburban space such as Morgan Park and Lilydale. Increasingly, though, blacks were confined to a narrow four-block strip around State Street on Chicago’s South Side known as the Black Belt. Half of Chicago’s blacks lived there in 1900, while 90% of Chicago’s blacks lived there by 1930.

The Black Belt was a crowded space where two or three families often squeezed into one-room apartments, landlords neglected to repair rotting floors or hinge-less doors, schools eventually ran on shifts so that each child was educated for only half a day, and the police tolerated gamblers and brothels. It was so unhealthy that Richard Wright called it “our death sentence without a trial.” Blacks who tried to move beyond the Black Belt were met with vandalism, arson, and bomb-throwers, including 24 bombs thrown in the first half of 1919 alone.

Earlier, some Chicago neighborhoods had welcomed black homeowners, but after the First World War there was an increasingly widespread belief that blacks hurt property values. Chicago realtor L. M. Smith and his Kenwood and Hyde Park Property Owners Association spread the notion that any black moving into a neighborhood was akin to a thief, robbing that street of its property values. By the 1920s, Chicago Realtors prohibited members from introducing any new racial group into a neighborhood and encouraged the spread of restrictive covenants, legally barring blacks while also consolidating ideas of whiteness. As late as 1945, two Chicago sociologists reported that, while “English, German, Scotch, Irish, and Scandinavian have little adverse effect on property values[,] Northern Italians are considered less desirable, followed by Bohemians and Czechs, Poles, Lithuanians, Greeks, and Russian Jews of the Lower class. Southern Italians, along with Negroes and Mexicans, are at the bottom of the scale.” As historians of race recognize, many European immigrants were considered not quite white before 1950. Those immigrants eventually joined the alliance of groups considered white partly because realtors, mortgage lenders, and housing economists established a bright line between the property values of “whites” and those of blacks.

The lines established in 1919 have lingered. As late as 1990, among Chicago’s suburban blacks, almost half of them lived in the same fourteen suburbs that blacks had lived in before 1920: they had not gained access to newer spaces. It was black neighborhoods that suffered disproportionately from urban renewal and the construction of tall-tower public housing in the twentieth century, further reinforcing the overlaps between race and space in Chicago. Many whites inherit property whose value has increased because of the racist real-estate policies founded after the violence of 1919. Recently, Ta-Nehisi Coates has recently used the history of Chicago’s property market to publicize “The Case for Reparations,” after generations of denying blacks access to homeowner equity.

It is worth remembering the events of 95 years ago, when Eugene Williams and 37 other people died, as Chicagoans clashed in the streets over emerging ideas of racialized property values.

Elaine Lewinnek is a professor of American Studies at California State University, Fullerton and the author of The Working Man’s Reward: Chicago’s Early Suburbs and the Roots of American Sprawl.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post On the 95th anniversary of the Chicago Race Riots appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHumanitarian protection for unaccompanied children from Central AmericaHow much do you know about early Hollywood’s leading ladies?Memory and the Great War

Related StoriesHumanitarian protection for unaccompanied children from Central AmericaHow much do you know about early Hollywood’s leading ladies?Memory and the Great War

Humanitarian protection for unaccompanied children from Central America

We are approaching World Humanitarian Day, an occasion to honor the talents, struggles, and sacrifices of tens of thousands of humanitarian workers serving around the world in situations of armed conflict, political repression, and natural disaster. The nineteenth of August is also a day to recognize the tens of millions of human beings living and dying in situations of violence and displacement in West Africa, the Middle East, Central America, and every corner of the globe.

The notion of humanitarianism is linked to humanitarian law, the law of armed conflict or jus in bello, which strives to lessen the brutality of war, guided by the customary principles of distinction, necessity, proportionality, and humanity. But humanitarian workers animate these humanitarian principles on the ground in situations of human catastrophe that span the continuum of human and natural causation and overwhelm our capacity to categorize human suffering.

Today, humanitarian workers are active in every country in the world: from International Committee of the Red Cross workers in Nigeria helping displaced persons from communities attacked by Boko Haram insurgents; to UN High Commissioner for Refugees staff in Jordan and Lebanon assisting refugees from the civil war in Syria and Iraq; to Catholic Charities volunteers and staff in Las Cruces, New Mexico, United States sheltering women and children fleeing gang violence, human trafficking, and entrenched poverty in Central America.

US/Mexico border fence near Campo, California, USA. © PatrickPoendl via iStockphoto.

Humanitarian emergencies, whether defined in military, political, economic or environmental terms, have certain basic commonalities: life and livelihood are threatened; communities and families are fractured; farms and food stores are destroyed; and people are forced to move — from village to village, from rural to urban area, from city to countryside, or from one country or continent to another.

Humanitarian workers who engage with communities in crisis are not limited to one legal toolkit. Rather, they stand on a common ground shared by humanitarian law, human rights law, and refugee law. Their life-affirming interventions remind us that all these frameworks are animated by the same fundamental concern for people in trouble. Whether we look to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the principle of protecting the civilian population; to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its norms of family unity and child welfare; to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its prohibition against the forced return or refoulement of individuals to threatened persecution; or to the enhanced protections accorded unaccompanied children in the United States under the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008, the essential rules are remarkably similar. Victims and survivors of war, repression, and other forms of violence are worthy of legal and social protection. It is humanitarian workers who strive to ensure that survivors of violence enjoy the safety, shelter, legal status, and economic opportunities that they require and deserve.

For the unaccompanied children from Central America seeking refuge in the United States, humanitarian protection signifies that they should have the opportunity to integrate into US communities, to have access to social services, to reunify with their families, and to be represented by legal counsel as they pursue valid claims to asylum and other humanitarian forms of relief from deportation. When the US Congress passed the Refugee Act in 1980, it was in recognition of our humanitarian obligations under international refugee law. As a signatory to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, the United States pledged not to penalize refugees for their lack of legal status, but rather to protect them from deportation to threatened persecution. These humanitarian obligations preexist, animate, and complement specific provisions of federal law, including those that facilitate the granting of T visas to trafficking victims, humanitarian parole to individuals in emergency situations, and asylum to refugees. When new emergencies arise, our Congress, our executive, and our courts fashion the appropriate remedies, not out of grace, but to ensure that as a nation we fulfill our obligations to people in peril.

As an American looking forward to World Humanitarian Day, I am thinking about the nearly 70,000 unaccompanied children from Central America apprehended by the US Customs and Border Protection agency over the past 10 months; the 200 Honduran, Salvadoran and Guatemalan women and children who have stayed at the Project Oak Tree shelter in the border city of Las Cruces, New Mexico this month; and the over 400 children and families detained within the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in the small town of Artesia, New Mexico this very week. These kids and their families are survivors of poverty, targets of human trafficking, victims of gang brutality, and refugees from persecution. They have much in common with the displaced children of Northern Nigeria, Syria, and Iraq. Like their counterparts working with refugees and displaced persons throughout the world, the shelter volunteers, community residents, county social workers, immigration attorneys, and federal Homeland Security personnel who help unaccompanied children from Central America in the United States are all humanitarian workers. But so are our elected officials and legislators. And so are we. How will we honor World Humanitarian Day?

Jennifer Moore is on the faculty of the University of New Mexico School of Law. She is the author of Humanitarian Law in Action within Africa (Oxford University Press 2012). Read her previous blog posts.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Humanitarian protection for unaccompanied children from Central America appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17Education and crime over the life cycleMemory and the Great War

Related StoriesThe downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17Education and crime over the life cycleMemory and the Great War

Education and crime over the life cycle

Crime is a hot issue on the policy agenda in the United States. Despite a significant fall in crime levels during the 1990s, the costs to taxpayers have soared together with the prison population. The US prison population has doubled since the early 1980s and currently stands at over 2 million inmates. According to the latest World Prison Population List (ICPS, 2013), the prison population rate in 2012 stood at 716 inmates per 100,000 inhabitants, against about 480 in the United Kingdom and the Russian Federation – the two OECD countries with the next highest rates – and against a European average of 154. The rise in the prison population is not just a phenomenon in the United States. Over the last twenty years, prison population rates have grown by over 20% in almost all countries in the European Union and by at least 40% in one half of them. The pattern appears remarkably similar in other regions, with a growth of 50% in Australia, 38% in New Zealand and about 6% worldwide.

In many countries – such as the United States and Canada – this fast-paced growth has occurred against a backdrop of stable or decreasing crime rates and is mostly due to mandatory and longer prison sentencing for non-violent offenders. But how much does prison actually cost? And who goes to jail?

The average annual cost per prison inmate in the United States was close to 30,000 dollars in 2008. Costs are even higher in countries like the United Kingdom and Canada. Punishment is an expensive business. These figures have prompted a shift of interest, among both academics and policymakers, from tougher sentencing to other forms of intervention. Prison populations overwhelmingly consist of individuals with poor education and even poorer job prospects. Over 70% of US inmates in 1997 did not have a high school degree. In an influential paper, Lochner and Moretti (2004) establish a sizable negative effect of education, in particular of high school graduation, on crime. There is also a growing body of evidence on the positive effect of education subsidies on school completion rates. In light of this evidence, and given the monetary and human costs of crime, it is crucial to quantify the relative benefits of policies promoting incarceration vis-à-vis alternatives such as boosting educational attainment, and in particular high school graduation.

When it comes to reducing crime, prevention may be more efficient than punishment. Resources devoted to running jails could profitably be employed in productive activities if the same crime reduction could be achieved through prevention.

Establishing which policies are more efficient requires a framework that accounts for individuals’ responses to alternative policies and can compare their costs and benefits. In other words, one needs a model of education and crime choices that allows for realistic heterogeneity in individuals’ labor market opportunities and propensity to engage in property crime. Crucially, this analysis must be empirically relevant and account for several features of the data, in particular for the crime response to changes in enrollment rates and the enrollment response to graduation subsidies.

The findings from this type of exercise are fairly clear and robust. For the same crime reduction, subsidizing high school graduation entails large output and efficiency gains that are absent in the case of tougher sentences. By improving the education composition of the labor force, education subsidies increase the differential between labor market and illegal returns for the average worker and reduce crime rates. The increase in average productivity is also reflected in higher aggregate output. The responses in crime rate and output are large. A subsidy equivalent to about 9% of average labor earnings during each of the last two years of high school induces almost a 10% drop in the property crime rate and a significant increase in aggregate output. The associated welfare gain for the average worker is even larger, as education subsidies weaken the link between family background and lifetime outcomes. In fact, one can show that the welfare gains are twice as large as the output gains. This compares to negligible output and welfare gains in the case of increased punishment. These results survive a variety of robustness checks and alternative assumptions about individual differences in crime propensity and labor market opportunities.

To sum up, the main message is that, although interventions which improve lifetime outcomes may take time to deliver results, given enough time they appear to be a superior way to reduce crime. We hope this research will advance the debate on the relative benefits of alternative policies.

Giulio Fella is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Economics and Finance at Queen Mary University, United Kingdom. Giovanni Gallipoli is an Associate Professor at the Vancouver School of Economics (University of British Columbia) in Canada. They are the co-authors of the paper ‘Education and Crime over the Life Cycle‘ in the Review of Economic Studies.

Review of Economic Studies aims to encourage research in theoretical and applied economics, especially by young economists. It is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journal, with a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers, and is essential reading for economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Prison, © rook76, via iStock Photo.

The post Education and crime over the life cycle appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat is the role of governments in climate change adaptation?Why are women still paid less than men?A revolution in trauma patient care

Related StoriesWhat is the role of governments in climate change adaptation?Why are women still paid less than men?A revolution in trauma patient care

The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

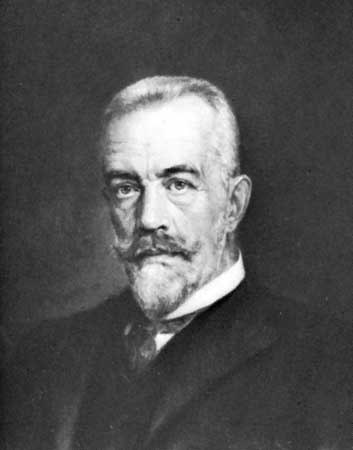

As the day began a diplomatic solution to the crisis appeared to be within sight at last. The German chancellor had insisted that Austria agree to negotiate directly with Russia. While Germany was prepared to fulfill the obligations of its alliance with Austria, it would decline ‘to be drawn wantonly into a world conflagration by Vienna’. Bethmann Hollweg was also promising to support Sir Edward Grey’s proposed conference to mediate the dispute. He told the Austrians that their political prestige and military honour could be satisfied by an occupation of Belgrade. They could enhance their status in the Balkans while strengthening themselves against the Russians through the humiliation of Serbia.

But a third initiative, the direct line of communication between the Kaiser and the Tsar, was running aground. Attempting to reassure Wilhelm, Nicholas explained that the military measures now being undertaken had been decided upon five days ago – and only as a defence against Austria’s preparations. ‘I hope from all my heart that these measures won’t in any way interfere with your part as mediator which I greatly value.’

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, Chancellor of the German Empire, 1909-1917. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Wilhelm erupted. He was shocked to discover first thing on Thursday morning that the ‘military measures which have now come into force were decided five days ago’. He would no longer put any pressure on Austria: ‘I cannot agree to any more mediation’; the Tsar, while requesting mediation, ‘has at the same time secretly mobilized behind my back’.The German ambassador in Vienna presented Bethmann’s directive to a ‘pale and silent’ Berchtold over breakfast. Austria, with guarantees of Serbia’s good behaviour in the future as part of the mediation proposal, could attain its aims ‘without unleashing a world war’. To refuse mediation completely ‘was out of the question’.

Berchtold did as he was told. He explained to the Russians that his apparent rejection of mediation talks was an unfortunate misunderstanding and that he was now prepared to discuss ‘amicably and confidentially’ all questions directly affecting their relations. He warned, however, that he would not yield on any of points in the note to Serbia.

At noon, Russia announced that it was initiating a partial mobilization. But the Austrian ambassador assured Vienna that this was a bluff: Sazonov dreaded war ‘as much as his Imperial Master’ and was attempting ‘to deprive us of the fruits of our Serbian campaign without going to Serbia’s aid if possible’.

In Berlin, the chief of the German general staff began to panic. A few hours after the Russian announcement he pleaded with the Austrians to mobilize fully against Russia and to announce this in a public proclamation. The only way to preserve Austria-Hungary was to endure a European war. ‘Germany is with you unconditionally’. Moltke promised that a German mobilization would immediately follow Austria’s.

In St. Petersburg the war minister and the chief of the general staff tried to persuade Nicholas over the telephone that partial mobilization was a mistake. The Tsar refused to budge. When Sazonov met with the Tsar at Peterhof at 3 p.m. he argued that general mobilization was essential; war was almost inevitable because the Germans were resolved to bring it about. They could easily have made the Austrians see reason if they had desired peace. The Tsar gave way. At 5 p.m. the official decree announcing general mobilization was issued.

In Paris the French cabinet was also deciding to take military steps. They agreed that – for the sake of public opinion – they must take care that ‘the Germans put themselves in the wrong’. They would try to avoid the appearance of mobilizing while consenting to at least some of the requests being made by the army. Covering troops could take up their positions along the German frontier from Luxembourg to the Vosges mountains, but were not to approach closer than 10 kilometres. No train transport was to be used, no reservists were to be called up, no horses or vehicles were to be requisitioned. Joffre, the chief of the general staff, was displeased. These measures would make it difficult to execute the offensive thrust of his war plan. Nevertheless, the orders went out at 4.55 p.m.

In London Grey bluntly rejected Bethmann’s neutrality proposal of the day before: ‘that we should bind ourselves to neutrality on such terms cannot for a moment be entertained’. Germany was asking Britain to stand by while French colonies were taken and France was beaten in exchange for Germany’s promise to refrain from taking French territory in Europe. Such a proposal was unacceptable ‘for France could be so crushed as to lose her position as a Great Power, and become subordinate to German policy’. On the other hand, if the current crisis passed and the peace of Europe preserved, Grey promised to endeavour to promote an arrangement by which Germany could be assured ‘that no hostile or aggressive policy would be pursued against her or her allies by France, Russia, and ourselves, jointly or separately’.

Shortly before midnight a telegram from King George arrived at Potsdam. Responding to an earlier telegram from the Kaiser’s brother, the King assured him that the British government was doing its utmost to persuade Russia and France to suspend further military preparations. This seemed possible ‘if Austria will consent to be satisfied with [the] occupation of Belgrade and neighbouring Servian territory as a hostage for [the] satisfactory settlement of her demands’. He urged the Kaiser to use his great influence at Vienna to induce Austria to accept this proposal and prove that Germany and Britain were working together to prevent a catastrophe.

The Kaiser ordered his brother to drive into Berlin immediately to inform Bethmann Hollweg of the news. Heinrich delivered the message to the chancellor at 1.15 a.m. and had returned to Potsdam by 2.20. Wilhelm planned to answer the King on Friday morning. The Kaiser noted, happily, that the suggestions made by the King were the same as those he had proposed to Vienna that evening.

Surely a peaceful resolution was at hand?

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Wednesday, 29 July 1914The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Wednesday, 29 July 1914The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914

July 29, 2014

How much do you know about early Hollywood’s leading ladies?

Clara Bow, whose birthday falls on 29 July, was the “it” girl of her time, making fifty-two films between 1922 and 1930. “Of all the lovely young ladies I’ve met in Hollywood, Clara Bow has ‘It,’” noted novelist Elinor Glyn. According to her entry in American National Biography, “With Cupid’s bow lips, a hoydenish red bob, and nervous, speedy movement, Bow became a national rage, America’s flapper. At the end of 1927 she was making $250,000 a year.”

Clara Bow by Paramount Photos. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In recognition of the numerous leading ladies of the early days of Hollywood, the American National Biography team has put together a quiz to test your knowledge of early Hollywood and its stars. Film buff or not, the experiences of these iconic actresses may surprise you.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Sarah Rahman is a Digital Product Marketing Intern at Oxford University Press. She is currently a rising junior pursuing a degree in English literature at Hamilton College.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How much do you know about early Hollywood’s leading ladies? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 191410 fun facts about the banjoCharting Amelia Earhart’s first transatlantic solo flight

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 191410 fun facts about the banjoCharting Amelia Earhart’s first transatlantic solo flight

Memory and the Great War

In honor of the 100th anniversary of World War I, we’re sharing an excerpt of Sir Hew Strachan’s The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. Get a sense of what it was like to live through this historic event and how its global effects still impact the world today.

The Great War haunted the last century; it haunts us still. It continues to inspire imaginative endeavour of the highest order. It invites pilgrimage and commemoration surrounded by palpable sadness. Almost a hundred years after the war, ‘The Last Post’, intoned every evening at the Menin Gate in Ypres, still summons tears. We wish it all had not happened.

We associate the war with the loss of youth, of innocence, of ideals. We are inclined to think that the world was a better and happier place before 1914. If the last century has been one of disjunction and endless surprise rather than of the mounting predictability many expected at the next-to-last fin-de-siècle, the Great War was the greatest surprise of all. The war stands, by most historical accounts, as the portal of entry to a century of doubt and agony, to our dissatisfaction.

Its extremes of emotion, both the initial jubilation and subsequent despair, are seen as a preface to the politics of extremism that took hold in Europe in the aftermath; its mechanized killing is regarded as a necessary prelude to the even greater ferocity of the Second World War and to the Holocaust; its assault on the values of the Enlightenment is seen as a nexus between indeterminacy in the sciences and the aesthetics of irony. Monty Python might never have lived had it not been for the Great War. The war unleashed a floodtide of forces that we have been unable ever since to stem. ‘Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet, Lest we forget—lest we forget!’ How in the world, Mr Kipling, are we to forget?

Figure 11.1 from the Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. Used with permissions from Oxford University Press.

The enthusiasm surrounding the outbreak of war many described as a social and spiritual experience beyond compare. Engagement was the hallmark of the day. ‘We have,’ wrote Rupert Brooke, ‘come into our heritage.’ The literate classes, and by then they were the literate masses—teachers, students, artists, writers, poets, historians, and indeed workers, of the mind as well as the fist—volunteered en masse. School benches and church pews emptied. Those past the age of military service enrolled in the effort on the home front.

Words, literary words, visible on the page, flowed as they had never flowed before, in the trenches, at home, and across the seven seas. The Berlin critic Julius Bab estimated that in August 1914 50,000 German poems were being penned a day. Thomas Mann conjured up a vision of his nation’s poetic soul bursting into flame. Before the wireless, before the television, this was the great literary war. Everyone wrote about it, and for it.

Not surprisingly, the Great War turned immediately into a war of cultures. To Britain and France, Germany represented the assault, by definition barbaric, on history and law. Brutality was Germany’s essence. To Germany, Britain represented a commercial spirit, and France an emphasis on outward form, that were loathsome to a nation of heroes. Treachery was Albion’s name. Hypocrisy was Marianne’s fame.

But the war was also an expression of social values. The intense involvement of the educated classes led to a form of warfare, certainly on the western front, characterized by the determination and ideals of those classes. Trench warfare was not merely a military necessity; it was a social manifestation. It was to be, in a sense, the great moral achievement of the European middle classes. It represented their resolve, commitment, perseverance, responsibility, grit—those features and values the middle classes cherished most.

And here for dear dead brothers we are weeping.

Mourning the withered rose of chivalry,

Yet, their work done, the dead are sleeping, sleeping

Unconscious of the long lean years to be.

Those lines from the Wykehamist, the journal of Winchester College, of July 1917 evoked both the passing of an age and the crisis of a culture.

‘The bourgeoisie is essentially an effort,’ insisted the French bourgeois René Johannet. The Great War was essentially an effort too. The American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald would call the war on the western front ‘a love battle—there was a century of middle-class love spent here. All my beautiful lovely safe world blew itself up here with a great gust of high-explosive love.’ Fitzgerald’s ‘lovely safe world’ was one of empire, imperial ideas, and imperial dreams. It was a world of confidence, of religion, and of history. It was a world of connections. History was a synonym for progress.

Sir Hew Strachan is a professor of the History of War at the University of Oxford, Commonwealth War Graves Commissioner, and a Trustee of the Imperial War Museum. He also serves on the British, Scottish, and French national committees advising on the centenary of the First World War. He is the editor of The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War.

We’re giving away ten copies of The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War to mark the 100th anniversary of World War I. Learn more and enter for a chance to win. For even more exclusive content, visit the US ‘World War I: Commemorating the Centennial’ page or UK ‘First World War Centenary’ page to discover specially commissioned contributions from our expert authors, free resources from our world-class products, book lists, and exclusive archival materials that provide depth, perspective, and insight into the Great War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Memory and the Great War appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914The month that changed the world: Wednesday, 29 July 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914The month that changed the world: Wednesday, 29 July 1914

The month that changed the world: Wednesday, 29 July 1914

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Before the sun rose on Wednesday morning a new hope for a negotiated settlement of the crisis was initiated. The Kaiser, acting on the advice of his chancellor, wrote directly to the Tsar. He hoped that Nicholas would agree with him that they shared a common interest in punishing all of those ‘morally responsible’ for the dastardly murder of the Archduke, and he promised to exert his influence to induce Austria to deal directly with Russia in order to arrive at an understanding.

At 1 a.m. Nicholas appealed to Wilhelm for his assistance: ‘An ignoble war has been declared on a weak country.’ The indignation that this had caused in Russia was enormous and he anticipated that he would soon be overwhelmed by the pressure being brought to bear upon him, forcing him to take ‘extreme measures’ that would lead to war. To avoid this terrible calamity, he begged Wilhelm, in the name of their old friendship, ‘to do what you can to stop your allies from going too far.’

The question of the day on Wednesday was whether Austria-Hungary and Russia might undertake direct discussions to settle the crisis before further military steps turned a local Austro-Serbian war into a general European one.

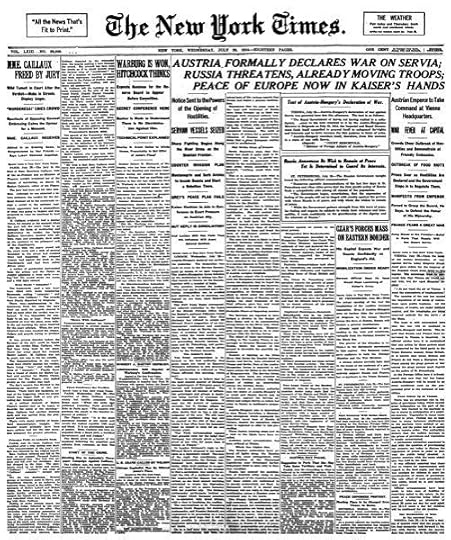

The New York Times, 29 July 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The German general staff summarized its view of the situation: the crime of Sarajevo had led Austria to resort to extreme measures ‘in order to burn with a glowing iron a cancer that has constantly threatened to poison the body of Europe’. The quarrel would have been limited to Austria and Serbia had not Russia begun making military preparations. Now, if the Austrians advanced into Serbia, they would face not only the Serbian army but the vastly superior strength of Russia. Thus, they could not contemplate fighting Serbia without securing themselves against an attack by Russia. This would force them to mobilize the other half of their army – at which point a collision between Austria and Russia would become inevitable. This would force Germany to mobilize, which would lead Russia and France to do the same – ‘and the mutual butchery of the civilized nations of Europe would begin’.

In other words, unless a negotiated settlement could be reached quickly, war seemed inevitable.

Berchtold pleaded with Berlin that only ‘plain speech’ would restrain the Russians, i.e. only the threat of a German attack would stop them from taking military action against Austria. And there were signs that Russia was wary of war. The Austrian ambassador reported that Sazonov was desperate to avoid a conflict and was ‘clinging to straws in the hope of escaping from the present situation’. Sazonov promised that if they were to negotiate on the basis of Sir Edward Grey’s proposal, Austria’s legitimate demands would be recognized and fully satisfied.

At the same time, Sazonov was pleading for British support: the only way to prevent war now was for Britain to warn the Triple Alliance that it would join its entente partners if war were to break out.

But Grey refused to make any promises. When he met with the French ambassador later that afternoon, he warned him not to assume that Britain would again stand by France as it had in 1905. Then it had appeared that Germany was attempting to crush France; now, ‘the dispute between Austria and Serbia was not one in which we felt called to take a hand’. Earlier that day the British cabinet had decided not to decide; Grey was to inform both sides that Britain was unable to make any promises.

At 4 p.m. the German general staff received intelligence that Belgium was calling up reservists, raising the numbers of the Belgian army from 50,000 to 100,000, equipping its fortifications and reinforcing defences along the frontier. Forty minutes later a meeting at the Neue Palais in Potsdam, the Kaiser and his advisers decided to compose an ultimatum to present to Belgium: either agree to adopt an attitude of ‘benevolent neutrality’ towards Germany in a European war or face dire consequences.

Simultaneously, Bethmann Hollweg decided to launch a bold new initiative. He proposed to the British ambassador that Britain agree to remain neutral in the event of war in exchange for a German promise not to seize any French territory in Europe when it ended. He understood that Britain would not allow France to be crushed, but this was not Germany’s aim. When asked whether his proposal applied to French colonies as well, the chancellor replied that he was unable to give a similar undertaking concerning them. Belgium’s integrity would be respected when the war ended –as long as it had not sided against Germany.

Yet another German initiative was taken in St Petersburg. At 7 p.m. the German ambassador transmitted a warning from the chancellor that if Russia continued with its military preparations Germany would be compelled to mobilize, in which case it would take the offensive. Sazonov replied that this removed any doubts he may have had concerning the real cause of Austria’s intransigence.

The Russians found this confusing, as they had just received another telegram from the Kaiser containing a plea that he should not permit Russian military measures to jeopardize German efforts to promote a direct understanding between Russia and Austria. It was agreed that the Tsar should wire Berlin immediately to ask for an explanation of the apparent discrepancy. At 8.20 p.m. the wire asking for clarification was sent. Trusting in his cousin’s ‘wisdom and friendship’, Tsar Nicholas suggested that the ‘Austro-Serbian problem’ be handed over to the Hague conference.

A message announcing a general mobilization in Russia had been drafted and ready to be sent out by 9 p.m. Then, just minutes before it was to be sent out, a personal messenger from the Tsar arrived, instructing that it the general mobilization be cancelled and a partial one re-instituted. The Tsar wanted to hear how the Kaiser would respond to his latest telegram before proceeding. ‘Everything possible must be done to save the peace. I will not become responsible for a monstrous slaughter’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Wednesday, 29 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914The month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914The month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914

July 28, 2014

The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Kaiser Wilhelm received a copy of the Serbian reply to the Austrian demands in the morning. Reading it over, he concluded that the Habsburg monarchy had achieved its aims and that the few points Serbia objected to could be settled by negotiation. Their submission represented a humiliating capitulation, and with it ‘every cause for war’ collapsed. A diplomatic solution to the crisis was now clearly within sight. Austria-Hungary would emerge triumphant: the Serbian reply represented ‘a great moral success for Vienna’.

In order to assure Austria’s success, to turn the ‘beautiful promises’ of the Serbs into facts, the Kaiser proposed that Belgrade should be taken and held hostage by Austria. ‘The Serbs,’ he pointed out, ‘are Orientals, and therefore liars, fakers and masters of evasion.’ An occupation of Belgrade would guarantee that the Serbs would carry out their promises while satisfying satisfying the honour of the Austro-Hungarian army. On this basis the Kaiser was willing to ‘mediate’ with Austria in order to preserve European peace.

In Vienna that morning the German ambassador was instructed to explain that Germany could not continue to reject every proposal for mediation. To do so was to risk being seen as the instigator of the war and being held responsible by the whole world for the conflagration that would follow.

Berchtold began to worry that German support was about to evaporate. He responded by getting the emperor to agree to issue a declaration of war on Serbia just before noon. For the first time in history war was declared by the sending of a telegram.

The bombardment of Belgrade by Austro-Hungarian monitor. By Horace Davis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The German chancellor undertook a new initiative to place the responsibility for a European war on Russia: he encouraged Kaiser to write directly to the Tsar, to appeal to his monarchical sensibilities. Such a telegram would ‘throw the clearest light on Russia’s responsibility’. At the same time he rejected Sir Edward Grey’s proposal for a conference in London in favour of ‘mediation efforts’ at St Petersburg, and trusted that his ambassador in London could get Grey ‘to see our point of view’.

At the Foreign Office in London they were skeptical. Officials concluded that the Austrians were determined to find the Serbian reply unsatisfactory, that if Austria demanded absolute compliance with its ultimatum ‘it can only mean that she wants a war’. What Austria was demanding amounted to a protectorate. Grey denied the German complaint that he was proposing an ‘arbitration’ – what he was suggesting was a ‘private and informal discussion’ that might lead to suggestion for settlement. But he agreed to suspend his proposal as long as there was a chance that the ‘bilateral’ Austro-Russian talks might succeed.

The news that Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia reached Sazonov in St Petersburg late that afternoon. He immediately arranged to meet with the Tsar at the Peterhof. After their meeting the foreign minister instructed the Russian chief of the general staff to draft two ukazes – one for partial mobilization of the four military districts of Odessa, Kiev, Moscow and Kazan, another for general mobilization. But the Tsar, who remained steadfast in his determination to do nothing that might antagonize Germany, would go no further than authorize a partial mobilization aimed at Austria-Hungary. He did so in spite of the warnings from his military advisers who told him that such a mobilization was impossible: a partial mobilization would result in chaos, make it impossible to prosecute a successful war against Austria-Hungary and render Russia vulnerable in a war with Germany.

A partial mobilization would, however, serve the requirements of Russian diplomacy. Sazonov attempted to placate the Germans by assuring them that the decision to mobilize in only the four districts indicated that Russia had no intention of attacking them. Keeping the door open for negotiations, he decided not to recall the Russian ambassador from Vienna – in spite of Austria’s declaration of war on Serbia. Perhaps there was still time for the bilateral talks in St Petersburg to save the situation.

That night Belgrade was bombarded by Austro-Hungarian artillery: two shells exploded in a school, one at the Grand Hotel, others at cafés and banks. Offices, hotels, and banks had been closed. The city had been left defenceless.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914The month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 25 July 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914The month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 25 July 1914

World Hepatitis Day: reason to celebrate

After years of intense basic and clinical research, hepatitis C is now curable for the vast majority of the millions of people who have it. The major barrier is access (diagnosis, getting care, and paying for it), because the scientific problem has been solved.

Not only that — but the situation will soon get even better.

For those who haven’t followed this medical miracle closely, here’s a Spark Notes version to bring you up to speed:

Pre-1989: Many blood transfusion recipients, injection drug users, and people with hemophilia have a form of chronic hepatitis, but they test negative for hepatitis A or B. Their infection is cleverly called “non-A, non-B hepatitis,” kind of a placeholder for a future discovery.

1989: A government-industry collaboration discovers the virus that causes “NANB hepatitis” (as it is sometimes further abbreviated). Good thing for that placeholder, because the new virus is called “hepatitis C”, abbreviated “HCV.” A few years later, a reasonably accurate blood test arrives, helping protect the blood supply and also giving us a much better sense of the natural history of HCV (generally slow but progressive liver disease), and finding a vast number of people infected, most of them unaware of it.

1990s: Remarkably, interferon therapy alone sometimes cures hepatitis C. That’s right, cures it. Unlike HIV and hepatitis B, HCV has no phase where it’s integrated into the host genome, so clearance of the virus completely occurs, provided the host and treatment factors are right. That’s the good news, but the rest, not so much: cure rates are terrible (generally

Late 1990s: Ribavirin — a mysterious antiviral whose mechanism of action still remains unclear — is added to interferon treatment, boosting cure rates up to 30-40% for genotype 1, 70% or higher for genotypes 2 and 3. Cause for celebration? Usually not, for several reasons: ribavirin has its own tricky side effects (hemolytic anemia, for one, and severe teratogenicity), so treatment is even more difficult than with interferon alone. Furthermore, the viral kinetics of successful treatment remain poorly defined, and hence patients are often given months of toxic therapy before it is ultimately stopped for “futility”.

Early 2000s: Attaching polyethylene glycol (PEG) to interferon greatly slows its clearance, so injections are now required only once a week. These “pegylated” forms of interferon plus ribavirin increase cure rates a bit further, as the reduced frequency of injections markedly improves adherence. (They also engender one of the best trade names ever for a drug – what marketing genius thought of Pegasys?) Side effects, alas, are no better. “I feel like I’m slowly killing myself,” says one of my patients, memorably, as he abandons treatment after 36 weeks of fatigue, snapping at his wife and co-workers, and general misery because his blood tests still show a bit of detectable virus – with no guarantee that continuing on to week 48 will cure him.

2011: The first “directly acting antivirals” (DAAs) are approved, the HCV protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir. For patients completing treatment with these drugs — again, in addition to interferon and ribavirin — cure rates for genotype 1 reach 70-80%. Certainly a big improvement, yes, but a few major caveats: first, though the treatment can sometimes (but not always) be shortened to 24 weeks with these three rather than two drugs, interferon and ribavirin side effects remain extremely problematic, with some of them (in particular the cytopenias) made even worse. Second, these first-generation protease inhibitors have their own set of nasty toxicities (anemia, rashes, taste disturbance, diarrhea, pain with defecation — another memorable patient quote: “I feel like I’m shitting glass shards.”) Third, both drugs have a high pill burden and, with telaprevir, stringent food requirements, making adherence extremely challenging.

Given the limitations of interferon (pegylated or not), ribavirin, telaprevir and boceprevir, it’s not surprising that many clinicians and patients decide it’s best to wait for better treatments to come. In fact, the cure rates from clinical trials are huge overestimates of the proportions actually cured in clinical practice, since there is intense clinician and patient self-selection about who should launch into these tough treatments. Meanwhile, research is proceeding rapidly (competition in this field is a good thing) to find other anti-HCV drugs, and several promising early clinical trials results are presented at academic meetings.

The practical culmination of this research finally arrives in late 2013 with the approval of first simeprevir — another protease inhibitor, only given as just one pill a day and with very few side effects — and, a few weeks later, sofosbuvir. The first HCV nucleotide polymerase inhibitor, sofosbuvir is also one pill a day, is highly potent, has few side effects or drug interactions, and is so effective it can help you get a better deal on your car insurance. (That last part was made up, but for the price — $1000 a pill — sofosbuvir better be pretty good.)

Simeprevir and sofosbuvir have been studied together in the COSMOS study and the bottom line is that more than 90% of genotype 1 patients are cured with 12 weeks of therapy. Some of the patients in COSMOS received no ribavirin, and most importantly none received interferon. It’s a small study, yes, and so we can’t take that response rate as applicable to everyone – some very difficult to treat individuals have already failed “SIM-SOF,” as the combination is being called by the HCV cognoscenti. But both in the clinical trial and thus far in clinical practice, this two-pill, once-daily regimen has shockingly few side effects.

So what’s next? How can this happy state of affairs get even better? Within the next 12 months, we’ll have a combination pill that gives HCV treatment as one pill a day. Some patients will be cured in 8 rather than 12 weeks. Other options (here and here) will arrive that have the same astounding cure rates – because a greater than 90% response is the price of entry into this HCV treatment arena. It’s hoped (and expected by many) that these expanded options will bring the cost of HCV therapy down, because that’s the way markets are supposed to work.

More than 90% cured. Sure beats the 9% rate from the interferon-only days.

And that, my friends, is reason to celebrate World Hepatitis Day.

Paul Edward Sax, MD is Clinical Director of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. He is the editor-in-chief of the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s new peer-reviewed, open access journal, Open Forum Infectious Diseases (OFID).

Open Forum Infectious Diseases provides a global forum for the rapid publication of clinical, translational, and basic research findings in a fully open access, online journal environment. The journal reflects the broad diversity of the field of infectious diseases, and focuses on the intersection of biomedical science and clinical practice, with a particular emphasis on knowledge that holds the potential to improve patient care in populations around the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: World Hepatitis Day logo via World Hepatitis Alliance.

The post World Hepatitis Day: reason to celebrate appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA revolution in trauma patient careOccupational epidemiology: a truly global disciplineWhen simple is no longer simple

Related StoriesA revolution in trauma patient careOccupational epidemiology: a truly global disciplineWhen simple is no longer simple

Does pain have a history?

It’s easy to assume that we know what pain is. We’ve all experienced pain, from scraped knees and toothaches to migraines and heart attacks. When people suffer around us, or we witness a loved one in pain, we can also begin to ‘feel’ with them. But is this the end of the story?

In the three videos below Joanna Bourke, author of The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers, talks about her fascination with pain from a historical perspective. She argues that the ways in which people respond to what they describe as ‘painful’ have changed drastically since the eighteenth century, moving from a belief that it served a specific (and positive) function to seeing pain as an unremitting evil to be ‘fought’. She also looks at the interesting attitudes towards women and pain relief, and how they still exist today.

On the history of pain

Click here to view the embedded video.

How have our attitudes to pain changed?

Click here to view the embedded video.

On women and pain relief

Click here to view the embedded video.

Joanna Bourke is Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London. She is the prize-winning author of nine books, including histories of modern warfare, military medicine, psychology and psychiatry, the emotions, and rape. Her book An Intimate History of Killing (1999) won the Wolfson Prize and the Fraenkel Prize, and ‘Eyewitness’. She is also a frequent contributor to TV and radio shows, and a regular newspaper correspondent. Her latest book is The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Does pain have a history? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 25 July 1914A revolution in trauma patient care

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 25 July 1914A revolution in trauma patient care

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers