Oxford University Press's Blog, page 785

July 22, 2014

The downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17

The downing of the Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17 on 17 July 2014 sent shockwaves around the world. The airliner was on its way from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur when it was shot down over Eastern Ukraine by an surface to air missile, killing all people on board, 283 passengers including 80 children, and 15 crew members. The victims were nationals of at least 10 different states, with the Netherlands losing 192 of its citizens.

With new information being released hourly strong evidence seems to indicate that the airliner was downed by a sophisticated military surface to air missile system, the SA-17 BUK missile system. This self-propelled air defence system was introduced in 1980 to the Armed Forces of the then Soviet Union and which is still in service with the Armed forces of both Russia and Ukraine. There is growing suspicion that the airliner was shot down by pro-Russian separatist forces operating in the area, with one report by AP having identified the presence of a rebel BUK unit in close proximity of the crash site. The United States and its intelligence services were quick in identifying the pro-Russian separatists as having been responsible for launching the missile. This view is supported further by the existence of incriminating communications between the rebels and their Russian handlers immediately after the aircraft hit the ground and also a now deleted announcement on social media by the self declared Rebel Commander, Igor Strelkov. This evidence points to the possibility that MH17 was mistaken for an Ukrainian military plane and therefore targeted. Given that two Ukrainian military aircraft were shot down over Eastern Ukraine in only two days preceding 17 July 2014 a not unlikely possibility.

It will be crucial to establish the extent of Russia’s involvement in the atrocity. While there seems to be evidence that the rebels may have taken possession of BUK units of the Ukrainian, it seems unlikely that they would have been able to operate these systems without assistance from Russian military experts and even radar assets.

Makeshift memorial at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport for the victims of the Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 which crashed in the Ukraine on 18 July 2014 killing all 298 people on board. Photo by Roman Boed. CC BY 2.0 via romanboed Flickr.

Russia was quick to shift the blame on Ukraine itself, asking why civil aircraft hadn’t been barred completely from overflying the region, directly blaming Ukraine’s aviation authorities during the emergency meeting on the UN Security Council (UNSC) on 18 July 2014. Russia even went so far to blame Ukraine indirectly of shooting down MH17 by comparing the incident with the accidental shooting down of a Russian civilian airliner en route from Tel Aviv to Novosibirsk in 2001. Despite Russia’s call for an independent investigation of the incident, Moscow’s rebels reportedly blocked actively international observers from OSCE to access the site.

While any civilian airliner crash is a catastrophe, and in cases of terrorist involvement an international crime, the shooting down of passenger jets by a state are particularly shocking as they always affect non combatants and resemble acts which are always outside the parameters of the legality of any military action (such as distinction, necessity, and proportionality). Any such act would lead to global condemnation and would hurt the perpetrator state’s international reputation. Consequently, there have only been few such incidents over the last 60 years.

What could be the possible consequences? The rebels are still formally Ukrainian citizens and as such subject to Ukraine’s criminal judicial system, according to the active personality principle. Such a prosecution could extent to the Russian co-rebels as Ukraine could exercise its jurisdiction as the state where the crime was committed, under the territoriality principle. In addition prosecutions could be initiated by the states whose citizens were murdered, under the passive personality principle of international criminal law. With Netherlands as the nation with the highest numbers of victims having a particularly strong interest in swift criminal justice, memories of the Pan Am 103 bombing come to mind, where Libyan terrorists murdered 270 humans when an airliner exploded over Lockerbie in Scotland. Following international pressure, Libya agreed to surrender key suspects to a Scottish Court sitting in the Netherlands.

The establishment of an international(-ised) criminal forum for the prosecution of the perpetrators would require Russia’s cooperation, something which seems to be unlikely given Putin’s increasing defiance of the international community’s call for justice. A prosecution by the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague under its Statute, the Rome Statute, is unlikely to happen as neither Russian nor Ukraine have ratified the Statute. An UNSC referral to the ICC — if one accepts that the murder of 298 civilians would amount to a crime which qualifies as a crime against humanity or even a war crime under Article 5 of the ICC Statute — would fail given that Russia and its new strategic partner China are Veto powers on the Council and would veto any resolution for a referral.

Other responses could be the imposing of unilateral and international sanctions and embargos against Moscow and high profile individuals. Related to such economic countermeasures is the possibility to hold Russia as a state responsible for its complicity in the shooting down of MH17; the International Court of Justice (ICJ) would be the forum where such a case against Russia could be brought by a state affected by the tragedy. An example for such an interstate case arising from a breach of international law can be found in the ICJ case Aerial Incident of 3 July 1988 (Islamic Republic of Iran v. United States of America), arising from the unlawful shooting down of Iran Air Flight 655 by the United States in 1988. The case ended with an out of Court settlement by the US in 1996. Again, it seems quite unlikely that Russia will accept any ruling by the ICJ on the matter and even less likely would be any compliance with an damages order by the court.

One alternative could be a true US solution for the accountability gap of Russia’s complicity in the disaster. If the US Congress was to qualify the rebel groups as terrorist organizations then this would make Russia a state sponsor of terrorism, and as such subject to US federal jurisdiction in a terrorism civil litigation case brought under the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA-18 USC Sections 2331-2338) as an amendment to the Alien Torts Statute (ATS/ATCA – 28 USC Section 1350). The so-called “State Sponsors of Terrorism” exception to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA Exception-28 USC Section 1605(a)(7)), which allows lawsuit against so-called state sponsors of terrorism. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) Exception of 1996 limits the defense of state immunity in cases of state sponsored terrorism and can be seen as a direct judicial response to the growing threat of acts of international state sponsored terrorism directed against the United States and her citizens abroad, as exemplified in the case of Flatow v. Islamic Republic of Iran (76 F. Supp. 2d 28 (D.D.C. 1999)). Utilising US law to bring a civil litigation case against Russia as a designated state sponsor of international terrorism would certainly set a strong signal and message to Putin; it remains to be seen whether the US call for stronger unified sanctions against Russia will translate into such unilateral action.

Time will tell if the downing of MH17 will turn out to be a Lusitania moment (the sinking of the British passenger ship Lusitania with significant loss of US lives by a German U-boat led to the entry of the US in World War I) for Russia’s relations with the West, which might pave the way to a new ‘Cold War’ along new conflict lines with different allies and alliances. What has become clear already today is Russia’s potential new role as state sponsor of terrorism.

Sascha-Dominik Bachmann is an Associate Professor in International Law (Bournemouth University); State Exam in Law (Ludwig-Maximilians Universität, Munich), Assessor Jur, LL.M (Stellenbosch), LL.D (Johannesburg); Sascha-Dominik is a Lieutenant Colonel in the German Army Reserves and had multiple deployments in peacekeeping missions in operational and advisory roles as part of NATO/KFOR from 2002 to 2006. During that time he was also an exchange officer to the 23rd US Marine Regiment. He wants to thank Noach Bachmann for his input. This blog post draws from Sascha’s article “Targeted Killings: Contemporary Challenges, Risks and Opportunities” in the Journal of Conflict Security Law and available to read for free for a limited time. Read his previous blog posts.

The Journal of Conflict & Security Law is a refereed journal aimed at academics, government officials, military lawyers and lawyers working in the area, as well as individuals interested in the areas of arms control law, the law of armed conflict and collective security law. The journal aims to further understanding of each of the specific areas covered, but also aims to promote the study of the interfaces and relations between them.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in QatarWhat are most important issues in international criminal justice today?Poetic justice in The German Doctor

Related StoriesWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in QatarWhat are most important issues in international criminal justice today?Poetic justice in The German Doctor

The exaltation of Christ

Every Good Friday the Christian church asks the world to contemplate a Christ so helpless, so in thrall to the powers of this age, that one might easily forget the Christian belief that through it all, God was with him and in him. Therein lies the danger of serious misunderstanding: for if any were so distracted by the pain of the crucifixion as to forget that it was God who in Christ consented to be there humiliated, then, from a Christian point of view, they would have robbed the event of its chief significance. If God were not in Christ on that first Good Friday, then Jesus’ cross was simply another of the world’s griefs, one more item in that tally of blood and violence that marks our history from the biblical murder of Abel, through Auschwitz and Hiroshima, to the latest act of inhumanity in our own time. The cross of Jesus is different precisely because in a unique way God was involved in it. Good Friday shows Christians what prophets and psalmist had spoken of through the ages: the pathos of God, who is afflicted in all our afflictions.

But then, as the climax of Easter, the church at Ascensiontide presents the world with an altogether different picture: a picture of Jesus “exalted with triumph” and “ascended far above all heavens,” as the various Collects associated with the Ascension have it. This is a picture so full of divine glory that one might be tempted to fall into the opposite error. One might be tempted to forget that amid this glory it is humanity—our humanity—which is here raised to the right hand of God. From a Christian point of view, if it is not our humanity that is here exalted, then the Ascension is no more than the pleasing story of a god, and has little to do with us. The exaltation of Jesus means that humanity is bound to God in God’s glory. The Ascension of Jesus is therefore a promise, a sign, and a first-fruit of our human destiny.

The Ascension by Giotto (c. 1305). Public domain via WikiArt.

To put it another way, Christ’s ascension reminds Christians that the risen life that they are promised will have a purpose, just as this life has a purpose. That purpose is union with God. Human beings in all their evident fragility are, as Second Peter puts it, to be “partakers of the divine nature,” perfectly united with the ascended Christ and with each other, beholders of and sharers in the glory which was (according to the Fourth Evangelist) Christ’s before the foundation of the world. Of course Christians do not claim to know yet what that will mean, though many would suggest that from time to time they catch glimpses of it—in the noblest human endeavors (which as often as not come from the humblest among us), in the greatest of human art and performance, and (in another way) in the gospels’ accounts of the Transfiguration of Christ. Christians are, however, assured of this: that, as Saint Paul says, the risen life will have a glory to which the sufferings of this present age are “not worth comparing.” Perhaps First John puts it best of all, “My little children, already we are God’s children, and it is not yet manifest what we shall be. But we do know this, that when he is manifested we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is.”

It is in the light of that promise that Christians dare open their hearts to the Spirit of God and attempt those lunatic gestures to which the gospel invites them, such as forgiving their enemies, doing good to those who do evil to them, and turning the other cheek. They do not attempt this behavior because they think it leads to successful lives as the world counts success, or because they think it leads to clear consciences. If they did, they would be very naïve. Most likely such living leads to a cross, if they are good at it; or to a continuing sense of their own guilt and failure if (as is more usual) they are not. Why then try it at all? Simply because they believe that God is like this, forgiving those who do evil, and causing gracious rain to fall on the just and the unjust alike. And they try to be like God because as Christians they believe that that is their destiny.

Christopher Bryan is a sometime Woodward Scholar of Wadham College, Oxford. He was ordained deacon in Southwark Cathedral on Trinity Sunday 1960, and priest in 1961. He taught New Testament at the University of the South until his semi-retirement in 2008. He continues to write, teach, and serve local parishes as a priest. He is presently editor of the Sewanee Theological Review. In 2012 The University of the South awarded him the degree of Doctor of Divinity honoris causa. He is the author of several books on the Bible, including Listening to the Bible and The Resurrection of the Messiah, and also two novels, Siding Star and Peacekeeper.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The exaltation of Christ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRadical faith answers radical doubtApproaching peak skepticismCertainty and authority

Related StoriesRadical faith answers radical doubtApproaching peak skepticismCertainty and authority

Antislavery history and antislavery activism converge in Philadelphia

This past weekend, the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic held its thirty-sixth annual meeting in Philadelphia. Members attended conference sessions, browsed the book exhibit, and met up with colleagues old and new. But one group of SHEAR members also caught up with supporters and officers of Historians Against Slavery (HAS), a non-profit antislavery organization whose Board will hold its semi-annual meeting on Friday.

The coincidence of these two meetings is fitting, since HAS traces some of its intellectual and organizational roots to the 2005 annual meeting of SHEAR, also held in Philadelphia. On that occasion, James Brewer Stewart, the distinguished historian of American abolitionism and then president of SHEAR, delivered a presidential address entitled, “Reconsidering the Abolitionists in an Age of Fundamentalist Politics.” Stewart’s lecture, later published in the Journal of the Early Republic, urged historians in attendance to pay more attention to the role of evangelical abolitionists in the coming of the Civil War, citing the political success of present-day evangelical activists as evidence that grassroots movements can affect electoral and party politics.

Yet the address also had two larger questions in view: what is the legacy of nineteenth-century American antislavery in the present, and which present-day activists (if any) can rightly claim to wear the abolitionists’ mantle? While contemporary evangelicals on the Religious Right often claim to be descended from the abolitionists, Stewart challenged that pedigree, pointing to significant theological and political differences between the two movements. In 2005, Stewart left unanswered the question of which, if any, contemporary activists were the rightful heirs to the antislavery movement. He focused instead on the historiography of the sectional crisis. But from its opening lines, Stewart’s appeal to historians of the early republic to think about the intersection between their work and the present rang out like a clarion call: “Consider for a moment our own time.”

Iron mask, collar, leg shackles and spurs used to restrict slaves. Illus. in: The penitential tyrant / Thomas Branagan. New York : Samuel Wood, 1807. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division

In the years that followed, Stewart continued to consider “our own time” in relationship to his historical work. One result was Historians Against Slavery, which he founded in January 2011 after attending a large anti-trafficking conference the previous year. At that meeting, Stewart found a new group of activists claiming to be “modern-day abolitionists.” Some, but not all, hailed from the same circles of evangelical politics he had alluded to in his 2005 SHEAR address. As before, Stewart found that these would-be heirs were often ignorant of what earlier abolitionists believed, what they were up against, and what actions had contributed to their success. But if Stewart found that he had things to teach “modern-day abolitionists,” these activists also taught him much about the present. As Stewart learned more about the scale of contemporary forms of enslavement and human trafficking, he began to envision HAS as a vehicle for productive conversations between historians of slavery and abolitionism and contemporary antislavery activists—an organization that could help use history to make slavery history.

In the few short years since that vision took shape, Historians Against Slavery has become much more than a one-man show. When Stewart retires from the Board later this year, he will return to the ranks of a thriving organization now led by co-directors Randall Miller and Stacey Robertson, along with a seven-person Board. The Society now oversees a speakers bureau, a book series, a platform for organizing student antislavery groups called The Free Project, and a blog, Twitter feed, and Facebook page, which offer intellectual and practical resources for scholars, activists, and teachers. Plans are also underway for the Society’s second national conference in 2015, which will build on the success of a 2013 Conference held at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center.

Historians Against Slavery has also recently expanded its reach overseas, following in the footsteps of early transatlantic abolitionists. But SHEAR also continues to serve as a natural base for the collaborations between scholars and students that HAS seeks to foster. At last year’s meeting in St. Louis, historians packed the room for an HAS-sponsored session to hear Yale historian Edward Rugemer and others discuss how to teach the “long history of slavery.” And many of the new society’s Board Members, speakers, and supporters also hail from SHEAR.

This overlap in membership can be explained partly by the fact that some of the most influential scholarship on American abolitionism and slavery in the last thirty years got its start at SHEAR meetings or in SHEAR publications. That tradition continues this weekend in Philadelphia where, as the Junto blog pointed out in a preview, there were sessions on “the emancipation process,” antislavery petitions, and the politics of slavery. (The complete program is available online.)

Meanwhile, in the audience, on the panels, and gathered at post-session watering-holes around the City of Brotherly Love, Historians Against Slavery also heeds James Brewer Stewart’s original call to “consider for a moment our own time.”

Consider, for example, questions like this: How might we reconsider the abolitionists or early emancipation efforts in the antebellum North in an age when, according to one reputable, recent estimate, nearly 30 million people remain enslaved? To quote from the final pages of the final volume of David Brion Davis’s magisterial study of the problem of slavery, published just this year, what do the “shocking estimates of the number of women and men held today in different kinds of bondage” tell us about the history of slaveries that came before, and vice versa? How might activist work against slavery in all its forms , and how might historical expertise better inform activism in the present?

Those, among others, are the kinds of questions Historians Against Slavery are eager to ask and answer. Hopefully, by the time the thirty-sixth annual meeting of HAS rolls around, the organization will have followed in the footsteps of SHEAR in more ways than one, growing as SHEAR did from the vision of a few into an organization that embraces hundreds of dedicated citizen-scholars. Even more hopefully, however, in thirty-six years time, antislavery historians will be able to look back on decades of significant progress in the fight against human bondage.

As historians, though, we know from the past that such progress will hardly be inevitable. For, as David Brion Davis again reminds us, if the history of slavery abolition teaches any lesson, it is that moral progress, when it comes, must be “willed.”

W. Caleb McDaniel is the author of The Problem of Democracy in the Age of Slavery: Garrisonian Abolitionists and Transatlantic Reform (LSU Press, 2013), which won a Merle Curti Award from the Organization of American Historians. He is assistant professor of history at Rice University and a Board Member for Historians Against Slavery. He tweets at @wcaleb.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Antislavery history and antislavery activism converge in Philadelphia appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn the anniversary of air conditioningContested sites on India’s Deccan PlateauSame-sex marriage now and then

Related StoriesOn the anniversary of air conditioningContested sites on India’s Deccan PlateauSame-sex marriage now and then

Mindful Sex

Mindfulness seems to be everywhere in North American society today. One of the more interesting developments of this phenomenon is the emergence of mindful sex—the ability to let go of mental strain and intrusive thoughts so once can fully tap into sexual intercourse.

But how do we truly let go of various pervading thoughts and completely immerse ourselves in the sexual moment? Mindful sex is practiced in a variety of medical, religious, and spiritual ways.

In my research I’ve noticed three broad streams for the mindful sex movement. The first category is the scientific discussion of using mindfulness to treat sexually-related problems in a patient or client population. In the past six years more than a dozen clinical studies of the effectiveness of mindfulness in treating sexual problems have been published in respected peer-reviewed medical and psychological journals.

A leader in this field is Dr. Lori Brotto. She created a program for women who experienced lowered levels of sexual arousal following treatment for gynecologic cancers, and mindfulness meditation was a primary element. As Brotto explains, “After a foundation of mindfulness skills was established, we introduced more sensually-focused mindfulness exercises in which women were encouraged to notice sensations in the body while engaged in a progressive series of activities, for instance while having a bath, while examining her genitals in a mirror, while applying light touch to her genitals… Finally, they were introduced to erotic tools such as visual erotica, fantasy, and vibrators as reliable methods of boosting the sexual arousal response followed by a mindfulness of body sensations immediately afterward while they took note of any triggered arousal sensations in the body.” Initial results were encouraging, and subsequent studies seemed to support the assertion that mindfulness practice can help mitigate some problems for women experiencing significant sex-related conditions, especially decreased interest in sexual activity due to psychological or medical trauma.

Detail of the hands of an ancient stone Buddha statue. © Natalia_Kalyatina via iStockphoto

Studies such as Brotto’s are designed for the consumption of elite audiences with sophisticated training in the study and treatment of serious human maladies. They use Buddhist practices for clinical purposes, hoping to move their patients away from the effects of disease and biomedical treatment, defined in these studies as greater ability to engage in sexual activity and reduction of sex-related pain.

The second category of works on mindful sex—those belonging to the self-help genre—take these impulses further. These books and articles are often written by medical doctors, therapists, and other specialists, but their target audience is mainstream North Americans without any particular credentials or connection to the health industries. As such, they reach a vastly larger audience than the medicalized mindfulness studies. Books in this category are no strangers to the bestseller lists, and these mindful sex promoters tout their expertise on impressive websites and through popular TED talks.

A good example of this category is A Tired Woman’s Guide to Passionate Sex, by Dr. Laurie Mintz. As she states, “If you are among the astonishingly large group of women whose chief complaint is that chronic fatigue and stress from balancing multiple demands has led to a disinterest in sex, this book is designed to help you. The goal of this book is to get you feeling sexual again.” How does one achieve this goal? You guessed it: mindful sex. As Mintz explains, “Mindful sex is sex in which you are totally and completely immersed in the physical sensations of your body.”

The goal here is taken beyond dealing with serious medical illness, as in the scientific studies, and reoriented now toward providing what Mintz calls “awesome sex.” Using Buddhist practices in pop cultural applications, these promoters try to move their audience closer to a state of well-being, defined as getting past the regular difficulties of mainstream North American life and achieving more and better orgasms, along with increased emotional intimacy with one’s partner.

The third category is spiritual applications of Buddhist mindfulness to sex. These are typically promoted by people without formal medical or psychological credentials who operate outside of overtly Buddhist institutions. They offer mindful sex as part of a package of techniques and perspectives for personal enhancement.

An example is Orgasmic Yoga. As co-founder Bruce Gether explains in his manifesto, Nine Golden Keys to Mindful Masturbation:

“Mindful masturbation is a simple, yet powerful practice. It requires dedication, and becomes its own reward. Just pay full attention while you masturbate. Don’t let yourself get distracted by imagination. Keep your primary focus on yourself, your own body, your penis and your own sensations. This path of self-pleasure can take you into realms of ecstasy you have never before experienced.”

Mindful sex is framed in religious language here, rather than medical or psychological ones. As Gether says, “your penis is sacred… Your penis is an organ designed to provide you with the awareness that you are one with all things.” These spiritual applications of mindful sex go even further than the self-help ones, using Buddhist practices to help initiates achieve self-growth and transcendental bliss.

What are the points that I want to make with all of this? First, North Americans use Buddhist practices to enhance their desires, rather than retreat from or conquer them. Mindfulness of the body used to be an ascetic monastic practice designed to eliminate sexual feelings and break down the erroneous sense of an enduring personal self. Mindful sex is a pleasure-enhancing practice designed for laypeople to rekindle their sexual fires, promote self-esteem, and variously lead the practitioner to mind-blowing orgasm, greater bonding, or perhaps metaphysical oneness with all.

This transformation may be seen as ironic, but it is not without precedent, as Buddhism has been used for achieving these-worldly benefits more or less since its creation, be they faith-healing, safe childbirth, protection from harm, and so on. This sort of flexibility is what allows complex religious traditions such as Buddhism to cross cultural borders and find niches in new societies. By appearing in scientific, self-help, and spiritual modes, mindfulness is able to influence a far larger percentage of North Americans than the relatively small number of formal Buddhist adherents.

Jeff Wilson is Associate Professor of Religious Studies and East Asian Studies at Renison University College (University of Waterloo). He is the author of Mourning the Unborn Dead: A Buddhist Ritual Comes to America, Dixie Dharma: Inside a Buddhist Temple in the American South, and Mindful America: The Mutual Transformation of Buddhist Meditation and American Culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mindful Sex appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRadical faith answers radical doubtApproaching peak skepticismContested sites on India’s Deccan Plateau

Related StoriesRadical faith answers radical doubtApproaching peak skepticismContested sites on India’s Deccan Plateau

Debussy and the Great War

When war was declared in the summer of 1914, Claude Debussy was fifty-one. Widely regarded as the greatest living French composer, he lived in Paris in a fashionable, elegant neighborhood near the Bois de Boulogne. Politics had never held much interest for him, and as the movement toward war increased in both France and Germany, Debussy’s focus was on more personal matters. He worried about his growing debt, a result of consistently living beyond his means. And he was frightened by his lack of productivity: in the past few years he’d produced only a handful of compositions.

When France’s armies were mobilized, Debussy was genuinely astonished by the fervor it aroused. He himself was not a flag-waver, and took some pride in observing that he had never “had occasion to handle a gun.” But he was drawn into a more active role as family and friends became involved, and as the German invasion threatened to overrun Paris.

That September he witnessed the repulse of the German forces from temporary asylum in Angers, and grew increasingly horrified by daily reports in the French press of “Hun atrocities” against civilians in Belgium and France. The violation of Belgian neutrality by the Germans (“the rape of Belgium”) served as the basis for what became a well-organized propaganda campaign, one that soon drew on Debussy’s fame.

One of the first publications intended to broaden support for the Allies appeared in November 1914: King Albert’s Book. A Tribute to the Belgian King and People from Representative Men and Women Throughout the World. The popular English novelist, Hall Caine, was listed as “general organizer,” and there were more than 200 contributors from all branches of the arts, including Edward Elgar, Jack London, Edith Wharton, Walter Crane, Maurice Maeterlinck, and Anatole France. Debussy was one of the few composers approached to be part of the project, and contributed a short piano piece, Berceuse héroïque. He described it as as “melancholy and discreet . . . with no pretensions other than to offer a homage to so much patient suffering.”

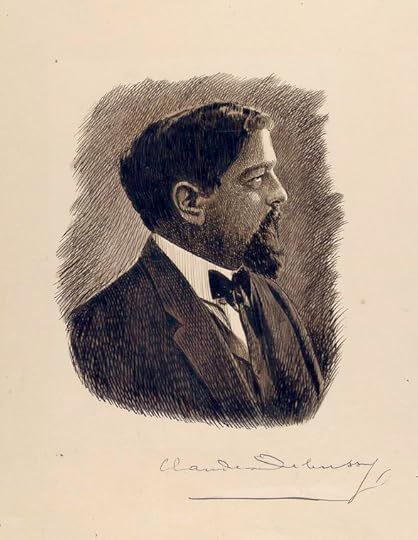

Claude Debussy. Ink drawing by Joseph Muller. Digital ID: 1147651. New York Public Library.

The Berceuse was followed by two brief piano pieces similar in intent: Page d’album and Elégie. Page d’album was composed in June 1915 for a concert series created to supplying clothing for the wounded. Debussy’s wife, Emma, was involved with the project, and that helps to explain his participation. The Elégie, a simple and solemn piece, was published six months later in Pages inédites sur la femme et la guerre. Profits from sale of the book were intended for war orphans.

That same month Debussy completed his final work directly inspired by the war effort: Noël des enfants qui n’ont plus des maisons (Christmas for Homeless Children). Here Debussy presented children as an illustration of the horror and atrocities of war. He composed both words and music. Its recurrent refrain—“Revenge the children of France!”—gives an indication of its mood. (The following year Debussy started work on a cantata about Joan of Arc, Ode à la France, set in Rheims—whose cathedral, destroyed by German shelling, had become a symbol both of French fortitude and German barbarity—but completed only a few sketches.)

Life in Paris during the war years became more and more of a challenge, with increasing shortages of food and fuel, and a steady escalation in their cost. In time it became difficult for Debussy simply to earn a living. Concert life was reduced, as were commissions for new compositions. Debussy’s last surviving, musical autograph—a short, improvisatory piano piece—was presented as a form of payment to his coal-dealer, probably in February or March 1917.

It came as a surprise to Debussy that, in the midst of all these hardships, he began to compose more than he had in years, including works more substantial in size and broader in their appeal. Among them were En Blanc et Noir (for two pianos), the Etudes (for solo piano), and a set of sonatas, including ones for violin and cello. These were not propagandistic pieces, but the war affected them nonetheless. They were created, Debussy confided to a friend, “not so much for myself, [but ]to offer proof, small as it may be, that 30 million Boches can not destroy French thought . . . I think of the youth of France, senselessly mowed down by those merchants of ‘Kultur’ . . . What I am writing will be a secret homage to them.” For the sonatas, the last compositions completed before his death, he provided a new signature: “Claude Debussy, musicien français”—an indication not just of Debussy’s nationalism during a time of war, but of the heritage he drew upon in writing them.

Debussy died of cancer on 21 March 1918, at a time when Paris was under attack as part of a mammoth, final German offensive. But by that time his perception of the war had altered. The years of carnage had made a straight-forward patriotic stance simplistic. “When will hate be exhausted?” Debussy wrote. “Or is it hate that’s the issue in all this? When will the practice cease of entrusting the destiny of nations to people who see humanity as a way of furthering their careers?”

Eric Frederick Jensen received a doctorate in musicology from the Eastman School of Music. He has written widely in his areas of expertise: German Romanticism, and nineteenth- and early twentieth-century French music. His studies of Debussy and Robert Schumann are in the Master Musicians Series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Debussy and the Great War appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn remembrance of Elaine StritchContested sites on India’s Deccan PlateauWilliam Mathias (1934-92) by his daughter, Rhiannon

Related StoriesIn remembrance of Elaine StritchContested sites on India’s Deccan PlateauWilliam Mathias (1934-92) by his daughter, Rhiannon

How much do you know about investment arbitration?

Investment arbitration is a growing and important area of law, in which states and companies often find themselves involved in. In recognition of the one year anniversary of Investment Claims moving to a new platform, we have created a quiz we hope will test your knowledge of arbitration law and multilateral treaties. Good luck!

Investment arbitration is a growing and important area of law, in which states and companies often find themselves involved in. In recognition of the one year anniversary of Investment Claims moving to a new platform, we have created a quiz we hope will test your knowledge of arbitration law and multilateral treaties. Good luck!

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Investment Claims (IC) is an acclaimed service for both practitioners and academic users. Regular updates mean that subscribers have access to a fully integrated suite of current and high quality content. This content comes with the guarantee of preparation and validation by experts.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in arbitration law, including Investment Claims, latest books from thought leaders in the field, and a range of other journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas, from international commercial arbitration to investment arbitration, dispute resolution and energy law, developing outstanding resources to support practitioners, scholars, and students worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the Commercial Law team @OUPCommLaw, and the International Law team @OUPIntLaw on Twitter.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: ICJ Robes, by International Organisation. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How much do you know about investment arbitration? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPreparing for International Council for Commercial Arbitration 2014Donor behaviour and the future of humanitarian actionWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in Qatar

Related StoriesPreparing for International Council for Commercial Arbitration 2014Donor behaviour and the future of humanitarian actionWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in Qatar

July 21, 2014

10 questions for Jenny Davidson

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 22 July 2014, Jenny Davidson, Professor of English at Columbia University, leads a discussion on Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park.

What was your inspiration for choosing this book?

What was your inspiration for choosing this book?

The book I’ll be talking about is Jane Austen’s novel Mansfield Park. It doesn’t tend to be a favorite with readers, though I’ve always loved it; I especially appreciated it when I was a graduate student, as there is something about the status of the novel’s protagonist Fanny Price as hanger-on and dependent relation that resonated with my own station in life! I write a little bit in my new book Reading Style: A Life in Sentences about how there is a perfect Austen novel for every stage of life: I loved Pride and Prejudice the most when I was young, Sense and Sensibility as a teenager, Emma in bossy adulthood, and Persuasion now that I have fully come into my own professionally as a literary critic. I am not a huge fan of Northanger Abbey, but I do love Austen’s juvenilia, the short tales like Love and Friendship and so forth. I think in many ways they show us how we might want to read the novels of Austen’s adulthood.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

I wanted to write books for as long as I can remember. (Here is the evidence: it’s my first known work, age three or so, as dictated to my mother.) I wrote compulsively throughout childhood and adolescence, but it wasn’t until my first year of college that I realized that though I really still wanted to write novels as well, my true vocation would be as a professor of literature. It still seemed an almost insurmountably long road, but from that point onward I was sure what direction I should point myself in.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

Well, many authors would have been very poor teachers – but I would have to say Anthony Burgess, whose book 99 Novels: The Best in English Since 1939 was my guide for reading throughout my teenage years. He would have been disreputable – unreliable, frequently hungover – but brilliant. Gore Vidal would have been another interesting one to have in the classroom.

What is your secret talent?

Punctuality. I have a very bad sense of direction – all places look the same to me, and I can get lost even in places I know very well – but it is easy for me to be on time and also to have a sense of how time’s passing. You would have to ask my students to know if this is really true, but I pride myself on not wasting their time in class and ending a little early whenever possible.

What word or punctuation mark do you most identify with?

The exclamation point! I do have a soft spot for the semi-colon, of course, and I can’t do without commas and periods. I am also rather partial to the em-dash and the hyphen, each of which has its own charms. I will hyphenate whenever possible.

Where do you do your best writing?

The truthful answer: anywhere with no Internet! I like to go to a cafe where there’s a bit of background buzz – easier for me to concentrate against a backdrop of minor noise than in full silence – and either write by longhand, with no distractions in the way of the internet.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

No, but I sometimes have to look up something or remind myself of what exactly I said in the past. My novel The Explosionist was written because I’d fallen in love with Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials books and Garth Nix’s Sabriel books, and was haunting the bookstore wishfully hoping for something similar. When there really wasn’t anything new along those lines, I realized that I would have to write it myself.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

I am still on longhand for a lot of draft-writing. Occasionally I have a project that seems to call out for typing rather than handwriting, but it’s less common. The couple things I always write on the computer, that come easily and enjoyably and wouldn’t feel the same in handwriting: blog posts and lectures.

What book are you currently reading? (And is it in print or on an e-Reader?)

Just finishing Alice Goffman’s wonderful On the Run, which I highly recommend. I love my Kindle Paperwhite, and read most of my pleasure reading on it these days. My apartment is also full of stacks of library books right now that I’m dipping into to make a new fall-semester syllabus.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

I have toyed with the idea of taking up “kitten socializer at animal shelter” as a secondary job description. More seriously: neurologist; epidemiologist; copy editor. It would be hard for me not to be an academic of one kind or another, though I suspect I’d be in the hard sciences, computer programming or mathematics if I weren’t a humanist.

Jenny Davidson is a Professor of English at Columbia University in the City of New York. She is interested in eighteenth-century British literature and culture; cultural and intellectual history, especially history of science; and the contemporary novel. He latest book is Reading Style: A Life in Sentences. She blogs at Light reading.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook. Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image couresty of Jenny Davidson.

The post 10 questions for Jenny Davidson appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive questions for Rebecca MeadSo you think you know Jane Austen?On Great Expectations

Related StoriesFive questions for Rebecca MeadSo you think you know Jane Austen?On Great Expectations

Bioscience, flies, and the future of teleportation

In pondering how rapidly animal, plant, microbial, viral, and human genetic and regulatory sequences travel around the world over wireless and fiber optic networks, I’m transported back to the sci-fi movie The Fly I watched as a boy. Released in 1958, the film was based on a story George Langelaan published in Playboy. In it, an experiment has gone awry: a matter transporter device called the disintegrator-integrator manages to hybridize the scientist who built it with a housefly. The fly sneaks into the action while the scientist is trying to dematerialize and transport himself from one chamber to another nearby. Two creatures result: a man with the head and left arm of a fly — the head retaining the scientist’s mental faculties — and a fly with a man’s miniature head and left arm.

Hybrid life forms are nothing new in biology. When neuroscientists outfitted laboratory mice with human brain cells, it prompted fears of “nightmare scenarios in which a human mind might be trapped in an animal head,” nightmare scenarios like that of The Fly. Leo Furcht and I noted the ethical concerns surrounding experiments that fused human embryonic cells with rabbit eggs, and human DNA with cow eggs, in The Stem Cell Dilemma. Ananda Chakrabarty, whose name is associated with the 1980 US Supreme Court decision ruling that genetically modified organisms can be patented, raised the question “What is human? This is not a question of the moral dilemma to define a human but is a legal requirement as to how much (human) material a chimpanzee must have before it is declared a part human….”

Hermann Muller employed radioactivity to induce point mutations in the fruit fly Drosophila, sometimes with bizarre results, though there is no evidence (of which I am aware) that George Langelaan was influenced by such experiments in conceiving his story. The technologies that captured Langelaan’s imagination had more to do with communications and information. Communications and culture run the show in his story: the telephone, a constant annoyance that drives the scientist to search for an escape; the typewriter, which he turns to when his voice is altered by the failed experiment; and above all a metamorphic miscommunication made possible by a crude teleporter and a fly. Science and culture scholar Bruce Clarke sees Langelaan’s story and the film as an allegory of modern media.

Another allegory of modern media was the 1960s TV series Star Trek. Gene Roddenberry, its creator, had not read or viewed The Fly when he initially conceived of the “beam me up, Scotty” transporter that Star Trek made famous. Quantum physics tells us it’s not quite that simple to convert a person or object into energy, beam the energy to a target, and then reconvert it into matter. But physicist and author Michio Kaku has predicted that a teleportation device similar to that in Star Trek would be invented by the early 22nd century. (Roddenberry’s fictional device was invented in the early 22nd century by Dr. Emory Erickson.)

[image error]

The “transporter” on the Starship Enterprise. Photo by Konrad Summers. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

J. Craig Venter, who led teams that sequenced the genomes of both the fly (Drosophila) and Homo sapiens, described a “biological teleporter” in Life at the Speed of Light. What he and his research team created is manifestly not a matter disintegrator-integrator but a biological code conversion system. The machine, called a digital biological converter, transforms digital-biological information transmitted in electromagnetic waves into proteins, viruses, and even single microbial cells. Unlike the teleporting machines Langelaal and Roddenbery imagined, Venter’s is based on what is actually known about biology, physics, chemistry, materials science, and informatics. Venter’s converter incorporates a variety of technologies including nucleotide synthesis and 3D bioprinting. Though enveloped in myth, the biological teleporter/converter “is not a myth,” says Venter, whose project was funded by DARPA’s “Living Foundries” program. It is already being used to develop and produce vaccines over great distances, and in short order.

On the subject of great distances, Venter wants to use his system to detect life on Mars and bring it to earth. “Although the idea conjures up ‘Star Trek,’ the analogy is not exact,” the New York Times reported. “The transporter on that program actually moves Captain Kirk from one location to another. Dr. Venter’s machine would merely create a copy of an organism from a distant location — more like a biological fax machine.”

The technology timeline above shows the accelerating growth of biological technologies and their convergence with other technologies. Unlike Michio Kaku we do not speculate about human teleportation. We suggest that a self-replicating microbe created entirely from computer code may make its debut in the not-too-distant future. Teleporting it to Mars should be eminently feasible with existing technology. It would be a modest step until the day when mechanisms for our own disintegration and distant reintegration become available, mechanisms equipped with regulatory safeguards to protect us against complications posed by house pests.

William Hoffman has been a writer and editor in the University of Minnesota Medical School for more than three decades. He is the co-author of The Biologist’s Imagination: Innovation in the Biosciences with Leo T. Furcht. He has worked closely with faculty in genetics and bioengineering and with the medical technology and bioscience industries. He has also coauthored books and articles on genetics, stem cell research, and heart disease.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Bioscience, flies, and the future of teleportation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLiving in the shadows of healthFrailty and creativityIn remembrance of Elaine Stritch

Related StoriesLiving in the shadows of healthFrailty and creativityIn remembrance of Elaine Stritch

“How absurd!” The Occupation of Paris 1940-1944

In the Epilogue to his penetrating, well-documented study, Nazi Paris, Allan Mitchell writes “Parisians had endured the trying, humiliating, and essentially absurd experience of a German Occupation.” Odd as it may sound, “absurd” is exactly right. Both the word and the sense of absurdity come up again and again in the diary kept by a remarkable French intellectual during those “dark years,” as he called them. For the absurd is not only laughable: it can be dangerous. Here is a sampling of the absurdities Jean Guéhenno noted in his Diary of the Dark Years 1940-1944.

24 October 1940

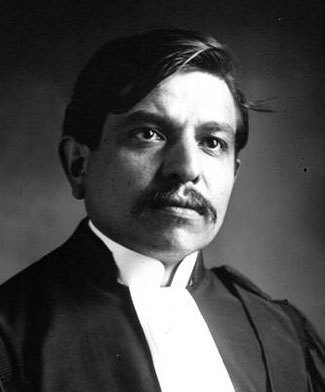

French politician Pierre Laval (1883-1945) as lawyer in 1913. Agence de presse Meurisse Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Yesterday evening all the newspapers were shouting out the great news: “M. Pierre Laval has met with the Führer.” . . . For what price did he sell us down the river? As early as 9 PM, the English radio was announcing the conditions of the deal: but what can we really know about it? Did the Marshal reject them? Are we going to be forced to put all our hopes on the resistance of that old man? This tyranny is too absurd, and its absurdity is too obvious to too many people for it to last.

For we have been plunged into vileness, that much is certain, but still more into absurdity.

29 November 1940

The newspapers are lamentably empty. This morning, however, I find the speech that Alfred Rosenberg, the high priest of Nazism, delivered yesterday from the podium of our Chamber of Deputies. For it is from there that Nazism is to hold sway over France . . . The history of the 19th century, he claims, is nothing but the struggle of blood against gold. “But today, blood is victorious at last . . . which means the racist, creative strength of central Europe.” I am recopying it exactly . . . Race? Claiming to rebuild Europe on a fable like that — how absurd!

7 January 1941

. . . my deepest reason for hope: it’s just that all this is too absurd. Something as absurd as this cannot possibly last. It seems to me I can read their embarrassment on the faces of the occupying forces. Every day, they are increasingly obliged to feel like foreigners. They don’t know what to do in the streets of Paris or whom to look at. They are sad and exiled. The jailor has become the prisoner. If he were sincere and he could speak, he would apologize for being here. No doubt that pitiable revolver he carries at his side reduces us to silence. And so? For how long will he be carrying it — will he have to carry it? For, without a revolver . . . Will he be condemned to wear it forever and live in this exile, without any other justification, any other joy than that little revolver?

10 February 1941

Every evening at the Opera, I am told, German officers are extremely numerous. At the intermissions, following the custom of their country, they walk around the lobby in ranks of three or four, all in the same direction. Despite themselves, the French join the procession and march in step, unconsciously. The boots impose their rhythm.

11 March 1941

M. Darlan is proclaiming “Germany’s generosity.” It is the height of absurdity: these vanquished generals have become our masters, and because of their very defeat, they must fear England’s victory and the restoration of France above all.

17 September 1941

I went on a trip to Brittany for a change of air and to try to get supplies of food, for life here has become increasingly wretched . . . Everywhere I found the same absurdity . . . On the sea, on the moors, in the forest, . . . just when I was going to forget about him, suddenly the gray soldier was there in front of me, with his rifle and his face of an all-powerful, barbaric moron. But it is impossible that he himself cannot feel how vain is the terror he is wielding. The sailors of Camaret make fun of him openly . . . He will go away as he came; he will have gone on a long, absurd trip.

Paris Opera Palais Garnier by Smtunli, Svein-Magne Tunli. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

22 February 1943

. . . those officers one meets around the Madeleine and the Opera in their fine linen greatcoats, with their vain, high caps, that look of proud stupidity on their faces and those nickel-plated daggers joggling around their bottoms. Then there are [the] busy little females — those mailwomen or telephone operators who look like Walkyries: one can sense their vanity and emptiness. The other day on the Place de la Concorde in front of the Ministry of the Navy I stopped to watch the sentries — those unchanging puppets who have stood there on each side of the door for more than two years, without drinking, eating or sleeping, like the symbol of deadly, mechanical [German] order right in the middle of Paris. I stood looking at them for a while as they pivoted like marionettes. But one tires of the Nuremberg clock . . .

29 May 1944

A torrent of stupidity. Two movie actors had put on Racine’s Andromaque in the Édouard VII Theater. Their interpretation of the play seemed immoral. Andromaque has been banned. This morning, the newspapers are publishing the following note: “The French Militia is concerned about the intellectual protection of France as well as public morality. That is why the regional head of the for the Militia of the Paris region notified the Prefect of Police that it was going to oppose the production of the scandalous play by Messieurs Jean Marais and Alain Cuny now playing at the Édouard VII Theater. The Prefect of Police issued a decree immediately banning the play.

David Ball is Professor Emeritus of French and Comparative Literature, Smith College. He is the editor and translator of Diary of the Dark Years, 1940-1944: Collaboration, Resistance, and Daily Life in Occupied Paris.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post “How absurd!” The Occupation of Paris 1940-1944 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLife in occupied Paris during World War IIBritain, France, and their roads from empireOn the anniversary of air conditioning

Related StoriesLife in occupied Paris during World War IIBritain, France, and their roads from empireOn the anniversary of air conditioning

When simple is no longer simple

Cognitive impairment is a common problem in older adults, and one which increases in prevalence with age with or without the presence of pathology. Persons with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) have difficulties in daily functioning, especially in complex everyday tasks that rely heavily on memory and reasoning. This imposes a potential impact on the safety and quality of life of the person with MCI as well as increasing the burden on the care-giver and overall society. Individuals with MCI are at high risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s diseases (AD) and other dementias, with a reported conversion rate of up to 60-100% in 5-10 years. These signify the need to identify effective interventions to delay or even revert the disease progression in populations with MCI.

At present, there is no proven or established treatment for MCI although the beneficial effects of physical activity/exercise in improving the cognitive functions of older adults with cognitive impairment or dementia have long been recognized. Exercise regulates different growth factors which facilitate neuroprotection and anti-inflammatory effects on the brain. Studies also found that exercise promotes cerebral blood flow and improves learning. However, recent reviews reported that evidence from the effects of physical activity/exercise on cognition in older adults is still insufficient.

Surprisingly, studies have found that although numerous new neurons can be generated in the adult brain, about half of the newly generated cells in the brain die during the first 1-4 weeks. Nevertheless, research also found that spatial learning or exposure to an enriched environment can rescue the newly generated immature cells and promote their long-term survival and functional connection with other neurons in the adult brain

It has been proposed that exercise in the context of a cognitively challenge environment induces more new neurons and benefits the brain rather than the exercise alone. A combination of mental and physical training may have additive effects on the adult brain, which may further promote cognitive functions.

Daily functional tasks are innately cognitive-demanding and involve components of stretching, strengthening, balance, and endurance as seen in traditional exercise programs. Particularly, visual spatial functional tasks, such as locating a key or finding the way through a familiar or new environment, demand complex cognitive processes and play an important part in everyday living.

In our recent study, a structured functional tasks exercise program, using placing/collection tasks as a means of intervention, was developed to compare its effects on cognitions with a cognitive training program in a population with mild cognitive impairment.

Patients with subjective memory complaint or suspected cognitive impairment were referred by the Department of Medicine and Geriatrics of a public hospital in Hong Kong. Older adults (age 60+) with mild cognitive decline living in the community were eligible for the study if they met the inclusion criteria for MCI. A total of 83 participants were randomized to either a functional task exercise (FcTSim) group (n = 43) or an active cognitive training (AC) group (n = 40) for 10 weeks.

We found that the FcTSim group had significantly higher improvements in general cognitive functions, memory, executive function, functional status, and everyday problem solving ability, compared with the AC group, at post-intervention. In addition, the improvements were sustained during the 6-month follow-up.

Although the functional tasks involved in the FcTSim program are simple placing/collection tasks that most people may do in their everyday life, complex cognitive interplays are required to enable us to see, reach and place the objects to the target positions. Indeed, these goal-directed actions require integration of information (e.g. object identity and spatial orientation) and simultaneous manipulation of the integrated information that demands intensive loads on the attentional and executive resources to achieve the ongoing tasks. It is a matter of fact that misplacing objects are commonly reported in MCI and AD.

Importantly, we need to appreciate that simple daily tasks can be cognitively challenging to persons with cognitive impairment. It is important to firstly educate the participant as well as the carer about the rationale and the goals of practicing the exercise in order to initiate and motivate their participation. Significant family members or caregivers play a vital role in the lives of persons with cognitive impairment, influencing their level of activities and functional interaction in their everyday environment. Once the participants start and experience the challenges in performing the functional tasks exercise, both the participants and the carer can better understand and accept the difficulties a person with cognitive impairment can possibly encounter in his/her everyday life.

Furthermore, we need to aware that the task demands will decrease once the task becomes more automatic through practice. The novelty of the practicing task has to be maintained in order ensure a task demand that allows successful performance and maintain an advantage for the intervention. Novelty can be maintained in an existing task by adding unfamiliar features, and therefore performance of the task will remain challenging and not become subject to automation.

Dr. Lawla Law is a practicing Occupational Therapist for more than 24 years, with extensive experience in acute and community settings in Hong Kong and Tasmania, Australia. She is currently the Head of Occupational Therapy at the Jurong Community Hospital of Jurong Health Services in Singapore and will take up a position as Lecturer in Occupational Therapy at the University of Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia in August 2014. Her research interests are in Geriatric Rehabilitations with a special emphasis on assessments and innovative interventions for cognitive impairment. Dr. Law is an author of the paper ‘Effects of functional tasks exercise on older adults with cognitive impairment at risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised controlled trial’, published in the journal Age and Ageing.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Brain aging. By wildpixel, via iStockphoto.

The post When simple is no longer simple appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs the past a foreign country?You can save lives and moneyInequalities in life satisfaction in early old age

Related StoriesIs the past a foreign country?You can save lives and moneyInequalities in life satisfaction in early old age

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers