Oxford University Press's Blog, page 784

July 25, 2014

The vote for women bishops

By Linda Woodhead

By Linda Woodhead

There are two kinds of churches. The ‘church type’, as the great sociologist Ernst Troeltsch called it, has fuzzy boundaries and embraces the whole of society. The ‘sect type’ has hard boundaries and tries to keep its distance. Until recently, the Church of England has been the former – a church ‘by law established’ for the whole nation. Since the 1980s, however, the Church has veered towards sectarianism. It’s within this context that we have to understand the significance of the recent vote for women bishops.

Robert Runcie (Archbishop of Canterbury 1980 to 1991) was the last leader to have no doubts about the Church’s role as a pillar of society. That didn’t mean he was a flunky of the social establishment. When he prayed for the dead on both sides of the Falklands War, or commissioned the Faith in the City report which criticised the Thatcher government, he did so from a confident position at the centre of things rather than as critic standing on the margins.

A shift away from this stance began under Runcie’s successor, George Carey (Archbishop from 1991-2002). Carey was part of the modern evangelical wing of the Church, some of whose members were already pushing for the Church to keep its distance from ‘secular’ society, but it was under Archbishop Rowan Williams (2002-2012) that the really decisive shift took place.

The background was a British society whose values were changing rapidly. My recent surveys of British beliefs and values reveal a remarkably swift liberalisation of attitudes. In this context, liberalism is the conviction that all adults should be equally free to make up their minds about choices which affect them directly. Its opposite is not conservatism but paternalism – the view that one should defer to higher authorities.

In the 1960s and ‘70s the Church of England was travelling with society in a broadly liberal direction, with prominent Anglicans supporting the liberalisation of laws relating to abortion, homosexuality, and divorce. But after Runcie, Anglican leaders made a U-turn. The extension of equal rights to women and gay people proved hardest for them to swallow. At stake for evangelicals was God-ordained male headship, and for Anglo-Catholics, an exclusively male priesthood extending back to Christ himself, and good relations with Rome.

Under the leadership of Rowan Williams and John Sentamu, the Church of England campaigned successfully to be exempted from provisions of the new equality legislation, took a hard line against homosexual practice and gay marriage, and made continuing concessions to the opponents of women’s progress in the Church (women had first been ordained priests in 1994, expecting that the office of bishop would be opened to them soon after).

Williams often behaved like an outsider to mainstream English society. He was a fierce critic of liberal ‘individualism’, and thought that religious people should huddle together against the chilly winds of secularism (hence his support for sharia law). He favoured the moral conservatism of African church leaders over the liberalism of American ones, and made disastrous compromises with illiberal factions in the Church. It was the latter which led to the failure of the last vote for women bishops in 2012 – shortly before Williams stepped down.

Williams’ supporters can say that he maintained Anglican unity, both at home and abroad. But the cost has been enormous. Church of England numbers have collapsed, and it has become more marginal to society and most people’s lives than ever before.

So the vote to allow women bishops is a turning-point which may see the Church re-engage the moral sentiments of the majority of its members and the country as a whole. But the sectarian tendency remains strong. Although Archbishop Welby supports women bishops, he remains opposed to same-sex marriage and assisted dying, and takes very seriously the relationship with African churches and their leaders. The sectarian fringes of the Church remain influential, and the bishops remain isolated from the views of ordinary Anglicans. The Church as a whole creaks under the weight of historic buildings, unimaginative mangerialism, and sub-democratic structures.

Over the last few decades the Church of England has missed a great opportunity to reinvent itself as a genuinely liberal form of religion in a world suffering from an excess of sectarian religion of illiberal and paternalistic kinds. It lost its nerve at the crucial moment, forgetting that liberalism has Christian as well as secular roots, and reading Britain’s drive towards greater freedom and toleration as permissive rather than moral.

To task Anglican clergywomen with putting all this right is to ask too much. But the vote for women bishops strikes a blow against sectarian ‘male’ Christianity. And if the Church is serious about drawing closer to the people it is meant to serve, then becoming representative of half the population and an even bigger proportion of Anglicans has to count as a significant step in the right direction.

Linda Woodhead is Professor of Sociology of Religion at Lancaster University, UK. Her research interests lie in the entanglements of religion, politics, and economy, both historically and in the contemporary world. Between 2007 and 2013 she directed the Religion and Society Programme http://www.religionandsociety.org.uk, the UK’s largest ever research investment on religion. She is the author of Christianity: A Very Short Introduction, which comes out in its second edition in August. She tweets from @LindaWoodhead.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Common Worship Books, by Gareth Hughes (Own work). CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post The vote for women bishops appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTen landscape designers who changed the worldCameron’s reshufflePractical wisdom and why we need to value it

Related StoriesTen landscape designers who changed the worldCameron’s reshufflePractical wisdom and why we need to value it

July 24, 2014

The month that changed the world: Friday, 24 July 1914

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

By mid-day Friday heads of state, heads of government, foreign ministers, and ambassadors learned the terms of the Austrian ultimatum. A preamble to the demands asserted that a ‘subversive movement’ to ‘disjoin’ parts of Austria-Hungary had grown ‘under the eyes’ of the Serbian government. This had led to terrorism, murder, and attempted murder. Austria’s investigation of the assassination of the archduke revealed that Serbian military officers and government officials were implicated in the crime.

A list of ten demands followed, the most important of which were: Serbia was to suppress all forms of propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary; the Narodna odbrana was to be dissolved, along with all other subversive societies; officers and officials who had participated in propaganda were to be dismissed; Austrian officials were to participate in suppressing the subversive movements in Serbia and in a judicial inquiry into the assassination.

When Sazonov saw the terms he concluded that Austria wanted war: ‘You are setting fire to Europe!’ If Serbia were to comply with the demands it would mean the end of its sovereignty. ‘What you want is war, and you have burnt your bridges behind you’. He advised the tsar that Serbia could not possibly comply, that Austria knew this and would not have presented the ultimatum without the promise of Germany’s support. He told the British and French ambassadors that war was imminent unless they acted together.

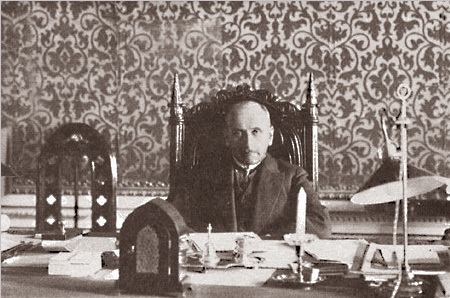

Sergey Sazonov, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

But would they? With the French president and premier now at sea in the Baltic, and with wireless telegraphy problematic, foreign policy was in the hands of Bienvenu-Martin, the inexperienced minister of justice. He believed that Austria was within its rights to demand the punishment of those implicated in the crime and he shared Germany’s wish to localize the dispute. Serbia could not be expected to agree to demands that impinged upon its sovereignty, but perhaps it could agree to punish those involved in the assassination and to suppress propaganda aimed at Austria-Hungary.

Sir Edward Grey was shocked by the extent of the demands. He had never before seen ‘one State address to another independent State a document of so formidable a character.’ The demand that Austria-Hungary be given the right to appoint officials who would have authority within the frontiers of Serbia could not be consistent with Serbia’s sovereignty. But the British government had no interest in the merits of the dispute between Austria and Serbia; its only concern was the peace of Europe. He proposed that the four ‘disinterested powers’ (Britain, Germany, France and Italy) act together at Vienna and St Petersburg to resolve the dispute. After Grey briefed the cabinet that afternoon, the prime minister concluded that although a ‘real Armaggedon’ was within sight, ‘there seems…no reason why we should be more than spectators’.

Nothing that the Austrians or the Germans heard in London or Paris on Friday caused them to reconsider their course. In fact, their general impression was that the Entente Powers wished to localize the dispute. Even from St Petersburg the German ambassador reported that Sazonov’s reference to Austria’s ‘devouring’ of Serbia meant that Russia would take up arms only if Austria seized Serbian territory and that his wish to ‘Europeanize’ the dispute indicated that Russia’s ‘immediate intervention’ need not be anticipated.

Berchtold made his position clear in Vienna that afternoon: ‘the very existence of Austria-Hungary as a Great Power’ was at stake; Austria-Hungary must give proof of its stature as a Great Power ‘by an outright coup de force’. When the Russian chargé d’affaires asked him how Austria would respond if the time limit were to expire without a satisfactory answer from Serbia, Berchtold replied that the Austrian minister and his staff had been instructed in such circumstances to leave Belgrade and return to Austria. Prince Kudashev, after reflecting on this, exclaimed ‘Alors c’est la guerre!’

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Friday, 24 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 13 July to Sunday, 19 July 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 13 July to Sunday, 19 July 1914

Polygamous wives who helped settle the west

Happy Pioneer Day! The morning of 24 July in downtown Salt Lake City, thousands of Westerners watch the “Days of ’47” parade celebrating the 1847 arrival of Mormon pioneers; in the afternoon, they attend a rodeo or take picnics to the canyons; at night they launch as many fireworks as they did for Fourth of July.

What may be less known than the role of Brigham Young in all this is the contribution made by polygamous women. When Brigham Young parceled out Salt Lake City land plots, he allowed polygamous husbands to draw a lot for each of their wives, and this pattern continued exponentially as polygamous wives sometimes moved without their husbands to settlements in Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico, supporting themselves as teachers, hat-makers, landlords, post mistresses, boarding house proprietors, laundresses, venders, and farmers.

Martha Heywood. Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society, all rights reserved.

For example, in 1850 not long after 39-year-old Martha Spence Heywood arrived in Salt Lake City, she became the third wife of the 35-year-old captain of her wagon train. After a few months of living in the family’s Salt Lake house, Martha moved 90 miles south to the new settlement of Nephi where she had the first of two babies in a wagon with one Church sister attending. She tried to establish herself as a teacher but wrote in her diary that there were “considerably hard feelings” against her “as a school teacher,” maybe because she was sometimes sick or maybe because townspeople resented her husband who did not live in Nephi but had a supervisory role in their struggling settlement. Along with teaching, Martha made hats that her husband advertised in the Salt Lake Deseret News. After a few years in Nephi, she moved to southern Utah and claimed a vacant “good adobe” house. Once again taking up school teaching, she even accepted produce as payment so that any child could attend school and, over the years, established herself as a legendary school teacher. The Heywood family owned homes in three towns.

Mary Ann Hafen. Courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Starting in 1890, Mormons no longer officially sanctioned new polygamous marriages, but those who were already married like second wife Mary Ann Hafen carried on until the polygamous generation died out. In 1891, she moved 50 miles away from her “general merchant” husband John (who lived in Santa Clara, Utah, with his first wife) to Bunkerville, Nevada, where they could get cheaper land. Mary Ann wrote in her autobiography that in the “first year” when she and her children were “just getting started” in Bunkerville, her husband came down from Santa Clara “frequently” and “helped [them] a good deal.” But as time went on, “he had his hands full taking care of his other [three] families,” so she cared “for her seven children mostly by [her]self” because, as she explained, “I did not want to be a burden on my husband, but tried with my family to be self-supporting.” John had provided them with “a house, lot, and land and furnished some supplies.” Mary Ann rented out her twenty-five-acre farm up the road—the 1900 census listed her as a “landlord.” Sometimes she and her children used the farm to grow cotton and sorghum cane that she could exchange at mills for cloth and sorghum sweetener. She sewed the family’s clothing on the White sewing machine she saved up for. They preserved peaches and green tomatoes and ate from their large garden, and they kept a couple of pigs, a cow, and some chickens.

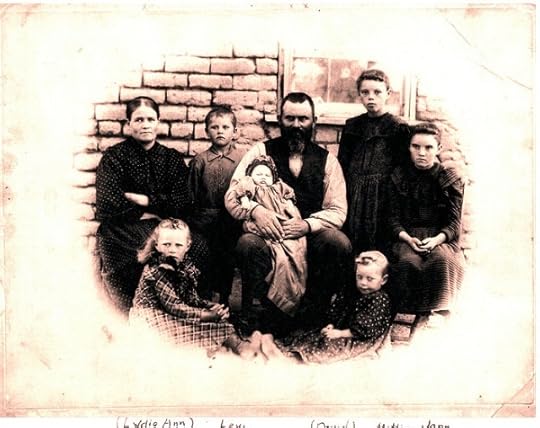

David and Lydia Ann Brinkerhoff Family. Courtesy of Joanne Hadden, family descendant.

In yet another example, first wife Lydia Brinkerhoff settled in the town of Holbrook, Arizona, while the second wife Vina and their husband settled on farmland outside town—the two locations multiplied the family’s financial prospects. In town, Lydia took in boarders, did laundry for hotels, sold vegetables from the farm, and managed the town’s mail contract.

Settling new land was not easy, and, in general, frontier women worked hard sewing linens and clothing, churning butter, making cheese, raising chickens, planting vegetable gardens, preserving jams and jellies, curing meat, cooking, producing soap and candles, and washing clothes. Mormon polygamous wives also took seriously their responsibility to nurture their children into their faith.

During the historical reflection that accompanies Pioneer Day, we can see how polygamous wives also participated in the Western American dreams of independence and expanding land ownership.

Paula Kelly Harline has been teaching college writing for over 20 years for the University of Idaho, Brigham Young University, and Utah Valley University. She has also worked as a freelance writer and artist. She currently lives with her husband, Craig, in Provo, Utah. She is the author of The Polygamous Wives Writing Club: From the Diaries of Mormon Pioneer Women.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Polygamous wives who helped settle the west appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMormon women “bloggers”: a long traditionMormon pioneer polygamous wives [infographic]What is consciousness?

Related StoriesMormon women “bloggers”: a long traditionMormon pioneer polygamous wives [infographic]What is consciousness?

Echoes of Billie Holiday in Fancy Free

When Leonard Bernstein first arrived in New York, he was unknown, much like the artists he worked with at the time, who would also gain international recognition. Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War looks at the early days of Bernstein’s career during World War II, and is centered around the debut in 1944 of the Broadway musical On the Town and the ballet Fancy Free. This excerpt from the book describes the opening night of Fancy Free.

When the curtain rose on the first production of Fancy Free, the audience at the old Metropolitan Opera House did not hear a pit orchestra, which would have followed a long-established norm in ballet. Rather, a recorded vocal blues wafted from the stage. Those attending must have been caught by surprise, as they were drawn into a contemporary sound world. The song was “Big Stuff,” with music and lyrics by Bernstein. It had been conceived with the African American jazz singer Billie Holiday in mind, even though it ended up being recorded for the production by Bernstein’s sister, Shirley. At that early point in Bernstein’s career, he lacked the cultural and fiscal capital to hire anyone as famous as Holiday. The melody and piano accompaniment for “Big Stuff” contained bent notes and lilting rhythms basic to urban blues, and the lyrics summoned up the blues as an animate force, following a standard rhetorical mode for the genre:

So you cry, “What’s it about, Baby?”

You ask why the blues had to go and pick you.

Talk of going “down to the shore” vaguely referred to the sailors of Fancy Free, as the lyrics became sexually explicit:

So you go down to the shore, kid stuff.

Don’t you know there’s honey in store for you, Big Stuff?

Let’s take a ride in my gravy train;

The door’s open wide,

Come in from out of the rain.

“Big Stuff” spoke to youth in the audience by alluding to contemporary popular culture. It boldly injected an African American commercial idiom into a predominantly white high-art performance sphere, and its raunchiness enhanced the sexual provocations of Fancy Free. “Big Stuff” also blurred distinctions between acoustic and recorded sound. It marked Bernstein as a crossover composer, with the talent to write a pop song and the temerity to unveil it within a high-art context.

Billie Holiday by William P. Gottlieb, c. February 1947. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Billie Holiday was “one of [Bernstein’s] idols,” according to Humphrey Burton. He admired her brilliance as a performer, and he was also sympathetic to her progressive politics. In 1939, Holiday first recorded “Strange Fruit,” a song about a lynching that became one of her signatures. With biracial and left-leaning roots, “Strange Fruit” was written by the white teacher and social activist Abel Meeropol. Holiday performed “Strange Fruit” nightly at Café Society, a club that enforced a progressive desegregationist agenda both onstage and in the audience. Those performances marked “the beginning of the civil rights movement,” recalled the famed record producer Ahmet Ertegun (founder of Atlantic Records). Barney Josephson, who ran Café Society, famously declared, “I wanted a club where blacks and whites worked together behind the footlights and sat together out front.”

Bernstein had experience on both sides of Café Society’s footlights. In the early 1940s, he performed there occasionally with The Revuers, and he played excerpts from The Cradle Will Rock in at least one evening session with Marc Blitzstein. Bernstein also hung out at the club with friends, including Judy Tuvim, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green, listening to the jazz pianist Teddy Wilson and boogie-woogie pianists Pete Johnson and Albert Ammons. Thus Bernstein had ample opportunities to witness the intentional “blurring of cultural categories, genres, and ethnic groups” that historian David Stowe has called the “dominant theme” of Café Society.

Robbins also had an affinity for the work of Billie Holiday. In the summer of 1940, he choreographed Holiday’s recording of “Strange Fruit” and performed it with the dancer Anita Alvarez at Camp Tamiment. “Strange Fruit was one of the most dramatic and heart-breaking dances I have ever seen—a masterpiece,” remembered Dorothy Bird, a dancer there that summer.

As a result of these experiences, the music of Billie Holiday had crossed the paths of both Robbins and Bernstein before “Big Stuff” opened their first ballet. While Billie Holiday’s voice was not heard the evening of Fancy Free’s premiere, only seven months passed before she recorded “Big Stuff” with the Toots Camarata Orchestra on November 8, 1944. The fact that Holiday made this recording so soon after the premiere of Fancy Free bore witness to the rapid rise of Bernstein’s clout within the music industry. Over the next two years, Holiday made six more recordings of “Big Stuff,” and when Bernstein issued the first recording of Fancy Free with the Ballet Theatre Orchestra in 1946, Holiday’s rendition of “Big Stuff” opened the disc. Both she and Bernstein recorded for the Decca label. Holiday recorded her final three takes of “Big Stuff” for Decca on March 13, 1946, and that label released Fancy Free the same year.

Musically, “Big Stuff” links closely to the worlds of George Gershwin and Harold Arlen, whose songs drew on African American idioms. Like some of the most beloved songs by these composers — whether Arlen’s “Stormy Weather” of 1933 or Gershwin’s “Summertime” of 1935 from Porgy and Bess – “Big Stuff” used a standard thirty-two-bar song form. With a tempo indication of “slow & blue,” “Big Stuff” has a lilting one-bar riff in the bass, a classic formulation for a jazzbased popular song of the day. The riff retains its shape throughout, as is also typical, while its internal pitch structure shifts in relation to the harmonic motion. Both the accompaniment and melody are drenched with signifiers of the blues, especially with chromatically altered third, fourth, sixth, and seventh scale degrees, and the overall downward motion of the melody is also characteristic of the blues, with a weighted sense of being ultimately earthbound.

Carol J. Oja is William Powell Mason Professor of Music and American Studies at Harvard University. She is author of Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War and Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s (2000), winner of the Irving Lowens Book Award from the Society for American Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to onyl music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Echoes of Billie Holiday in Fancy Free appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn remembrance of Elaine StritchContested sites on India’s Deccan PlateauThe month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914

Related StoriesIn remembrance of Elaine StritchContested sites on India’s Deccan PlateauThe month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914

If you’re so smart, why aren’t you happy?

‘I know these will kill me, I’m just not convinced that this particular one will kill me.’

–Jonathan Miller to Dick Cavett on his lit cigarette, backstage at the 92nd Street Y in New York

Jonathan Miller’s problem is actually a practical form of the central problem of ancient Greek philosophy (a problem that continues to haunt philosophy up to the present day): the essential relationship between the abstract and the particular. Miller is right. No particular cigarette can harm a person, either now or later. Only what is essentially an abstraction (the relationship between rate of smoking and health) will harm him. Can it be that Miller is just not a very smart person incapable of understanding abstractions? No way. He is a “public intellectual,” a British theater and opera director, actor, author, humorist, and sculptor. And on top of that a medical doctor.

No matter how smart we are, we all tend to focus on the particular when it comes to our own behavior. Only when we observe someone else’s behavior or when circumstances compel us to experience the long-term consequences of our own behavior, are we able to feel their force.

Cigarette Butts. Photo by Petr Kratochvil. Public Domain (CC0) via publicdomainpictures.net.

How then can we use our brains to bring our behavior under the control of its wider consequences? First, and most obviously, to control our behavior we have to know what exactly that behavior is. That is, we must make ourselves experts on our own behavior. It is this step – self-monitoring – that is by far the most difficult part of self-control. Modern technology can make self-monitoring easier, but I myself prefer to just write things down. At points in my life where I need to control my weight I keep a calorie diary in which I write down everything I eat, its caloric content, and the sum of the calories I eat each day. Then I make summaries each week. If I were trying to control my smoking I would record each cigarette and the time of day I smoked it – or, each glass of scotch, each heroin injection, each cocaine snort, each hour spent watching television or doing crossword puzzles when I should be writing, etc. Every instance goes down in the book. There is no denying it – this is hard to do. For one thing, it is socially difficult. You don’t want to interrupt a dinner party by running into the bathroom every five minutes to write down that you’ve bitten your nails again. This is one reason it’s good to be married (I’m serious). Your spouse (whose objective view is necessarily better than your own subjective view) will remember until you get home. Or you can (and should) train yourself to remember over short periods.

You may say that by recording your behavior you are constricting your freedom, but in this regard it is good to remember the poet Valerie’s advice: “Be light like a bird and not like a feather.”

This first step – self-monitoring – is so important, and so difficult, that it should not be mixed up with actual efforts at habit change. First make yourself an expert on yourself. Make charts; make graphs, if that comes naturally. But at least write everything down and make weekly and monthly summaries. Sometimes this step alone, without further effort, will effect habit change. But do not at this point try in any way to change whatever habit you are trying to control. Once you become an expert on yourself, you will be 90% there. The rest is all downhill.

After you have gained self-observational skill, you are ready to proceed to the second step. For example, Jonathan Miller’s problem is that, so to speak, each particular cigarette weighs too little. How could he have given it more weight? Let us say that Miller has already completed Step 1 and is recording each cigarette smoked and the time it was smoked. (Note that this already gives the cigarette weight. It doesn’t just go up in smoke but is preserved in his log.) Let us say further that the day of his encounter with Cavett was a Monday. On that day Miller smokes as much as he wants to. He makes no effort to restrict his smoking in any way. (He is still recording each instance.) However, on Tuesday he must force himself to smoke exactly the same number of cigarettes as he did on Monday. If necessary he must sit up an extra hour on Tuesday to smoke those 2 or 3 cigarettes to make up the total. Then on Wednesday he is free again, and on Thursday he has to mimic Wednesday’s total. Now, when he lights a cigarette on Monday he is in effect lighting up two cigarettes – one for Monday, and one for Tuesday. As he keeps to this schedule, and organizes his behavior into 2-day patterns, it should be coming under control of the wider contingencies. Once this pattern is firmly established, he can extend the pattern to three days, duplicating his Monday smoking on Tuesday and Wednesday, then Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, etc., always continuing to record his behavior. Eventually, each cigarette he lights up on Monday will effectively be 7 cigarettes – one for each day of the week. The weight of each cigarette will thus increase to the point where he no longer can say, “I’m not convinced that this particular cigarette will kill me.”

At no point is he trying to reduce his smoking or exerting his willpower. Willpower is not a muscle inside the head that can be exerted. It is bringing behavior under the control of wider (and more abstract) contingencies. This is a power that anyone can do who has the intelligence and is willing to invest the effort and time. And the exercise of this power can make a smart person happy.

Note: There is yet a third step – or rather a flight of steps. I have not mentioned social support. I have not mentioned exercise. Both of these are economic substitutes for addictions of various kinds. If either is lacking in an addict’s life, programs need to be established for its institution. I am assuming that we’re talking about the happiness of someone who already has an active social life, who already is as physically active as conditions allow. Addiction is not an isolated thing. It has to be regarded in the context of a complete life.

Howard Rachlin was trained as an engineer at Cooper Union and as a psychologist at The New School University and Harvard University. He has taught at Harvard University and at Stony Brook University. His current research, supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, lies in the development of methods for fostering human self-control and social cooperation. He is the author of The Escape of the Mind.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post If you’re so smart, why aren’t you happy? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy we don’t go to the moon anymoreThe month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914What is consciousness?

Related StoriesWhy we don’t go to the moon anymoreThe month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914What is consciousness?

The Great War letters of an Oxford family

The First World War has survived as part of our national memory in a way no previous war has ever done. Below is an extract from Full of Hope and Fear: The Great War Letters of an Oxford Family, a collection of letters which lay untouched for almost ninety years. They allow a unique glimpse into the war as experienced by one family at the time, transporting us back to an era which is now slipping tantalizingly out of living memory. The Slaters – the family at the heart of these letters – lived in Oxford, and afford a first-hand account of the war on the Home Front, on the Western Front, and in British India. Violet and Gilbert’s eldest son Owen, a schoolboy in 1914, was fighting in France by war’s end.

Violet to Gilbert, [mid-October 1917]

I am sorry to only write a few miserable words. Yesterday I had a truly dreadful headache which lasted longer than usual but today I am much better . . . I heard from Katie Barnes that their Leonard has been very dangerously wounded they are terribly anxious. But are not allowed to go to him. Poor things it is ghastly and cruel, and then you read of the ‘Peace Offensive’ articles in the New Statesman by men who seem to have no heart or imagination. I cannot understand it . . . You yourself said in a letter to Owen last time that [the Germans] had been driven back across the Aisne ‘We hope with great loss.’ Think what it means in agony and pain to the poor soldiers and agony and pain to the poor Mothers or Wives. It is useless to pretend it could not be prevented! We have never tried any other way . . . No other way but cruel war is left untried. I suppose that there will be a time when a more advanced human being will be evolved and we have learnt not to behave in this spirit individually towards each other. If we kept knives & pistols & clubs perhaps we should still use them. Yesterday Pat & I went blackberrying and then I went alone to Yarnton . . . the only ripe ones were up high so I valiantly mounted the hedges regardless of scratching as if I were 12 & I got nice ones. Then I went to the Food Control counter & at last got 5 lbs. of sugar . . . It was quite a victory we have to contend with this sort of sport & victory consists in contending with obstacles.

Gilbert to Owen, [9 February 1918]

I have been so glad to get your two letters of Dec. 7th & 18th and to hear of your success in passing the chemistry; and also that you got the extension of time & to know where you are . . . I am looking forward to your letters which I hope will make me realise how you are living. Well, my dear boy, I am thinking of you continually, and hoping for your happiness and welfare. I have some hope that your course may be longer than the 4 months. I fear now there is small chance of peace before there has been bitter fighting on the west front, and little chance of peace before you are on active service. I wonder what your feelings are. I don’t think I ever funked death for its own sake, though I do on other accounts, the missing a finish of my work, and the possible pain, and, very much more than these, the results to my wife & bairns. I don’t know whether at your age I should have felt that I was losing much in the enjoyment of life, not as much as I hope you do. I fear you will have to go into peril of wounds, disease and death, yet perhaps the greater chance is that you will escape all three actually; and, I hope, when you have come through, you will feel that you are not sorry to have played your part.

Second Lieutenant Owen Slater ready for service in France. Photo courtesy of Margaret Bonfiglioli. Do not reproduce without permission.

Owen to Mrs Grafflin, [3 November 1918]

This is just a very short note to thank you for the knitted helmet that Mother sent me from you some time ago. It is very comfortable & most useful as I wear it under my tin hat, a shrapnel helmet which is very large for me & it makes it a beautiful fit.

We are now out at rest & have been out of the line for several days & have been having quite a good time though we have not had any football matches & the whole company is feeling rather cut up because our O.C. [Officer Commanding] has died of wounds. He was an excellent [word indecipherable] father to his men & officers.

Margaret Bonfiglioli was born in Oxford, where she also read English. Tutoring literature at many levels led to her involvement in innovative access courses, all while raising five children. In 2008 she began to re-discover the hoard of family letters that form the basis of Full of Hope and Fear. Her father, Owen Slater, is one of the central correspondents. After eleven years tutoring history in the University of Oxford, James Munson began researching and writing full-time. In 1985 he edited Echoes of the Great War, the diary of the First World War kept by the Revd. Andrew Clark. He also wrote some 50 historical documentaries for the BBC.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Great War letters of an Oxford family appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914What can poetry teach us about war?Why we don’t go to the moon anymore

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Monday, 20 July to Thursday, 23 July 1914What can poetry teach us about war?Why we don’t go to the moon anymore

July 23, 2014

Which witch?

To some people which and witch are homophones. Others, who differentiate between w and wh, distinguish them. This rather insignificant phenomenon is tackled in all books on English pronunciation and occasionally rises to the surface of “political discourse.” In the thirties of the past century, an irritated correspondent wrote to the editor about “the abuse of such forms as what, when, which, wheel, and others”: “Dictionaries in vain lay down the law that the h should be heard in such words. If heard at all it will probably come from the lips of Scotsmen, as they do give full value to the h. In this way the difference of a nationality can, as a rule, be detected. Long ago I had to be present at King’s College when the prizes were given away. A Mr. Wheeler was a winner of the Elocution prize; but he was called out as Mr. Weeler by, save the mark, the Professor of Elocution himself.” We’ll save the mark and go on.

In Old English, many words began with hl-, hn-, hr-, and hw-. In the beginning, the letter h stood for ch, as in Scots loch or gh as in the family name McLaughlin. Later it was weakened to h and lost. The same change occurred in the other Germanic languages, except Icelandic and, if I am not mistaken, Faroese. Sounds seldom disappear without a trace. Thus, when h was shed, it devoiced the consonant after it. In Icelandic, voiceless l, n, and r can easily be heard, but elsewhere they merged with l, n, and r in other positions. Only hw developed differently. It either stayed in some form or devoiced w.

It has never been explained why consonants tend to disappear before l, n, r, and w. A classic example of this process, not related to the subject being discussed here, is the fate of kn- and gn-, as in knock and gnaw. One can of course say that such groups are rare and inconvenient for pronunciation. But such an explanation is illusory, because it presents the result of the change as its cause. Outside English, kn- and gn- cause speakers no trouble. Besides, the loss of k- and g- happened at a certain time. Why did it “suddenly” become inconvenient to articulate the groups that had not bothered the previous generations? We will accept the history of hw as we find it and leave it to others to account for the change.

The reverse spelling (wh- for hw-) goes back to Middle English and can only confuse those who believe that modern spelling is a good guide to etymology. The letter writer, whose displeasure with dictionaries we have just witnessed, made no mistake. The speakers of London, where in the late Middle Ages the Modern English norm was being forged, lost h before w and accepted voiced w (this happened as early as the end of the fourteenth century), while northern England, Scotland, Ireland, and, to some extent, American English have either hw or voiceless w.

Yet some authorities who taught as late as the first half of the eighteenth century insisted on the necessity to enunciate h before w. They may have trusted the written image of the words in question. In 1654 and the subsequent decades, such opinions could no longer be heard. After voiced w had won the victory in southern speech, the “true” (historical) pronunciation was often recommended as correct and returned to solemn recitation and sometimes even to everyday speech. Such cases are not too rare. Consider the pronunciation often and fore-head, which owe their existence to modern spelling. Some people believe that the more “letters” they pronounce, the more educated they will sound. “Ofen” and “forid,” rhyming with soften and horrid, strike them as slipshod.

It is instructive to look at some Modern English words beginning with wh-. Quite a few, including when, where, what, and why, did once have hw- at the beginning. As a result, southerners have homophones like which ~ witch, when ~ wen, whither ~ wither, whale ~ wail, and so forth. (Shakespeare could not know that woe and wail are related, but his ear and instinct made him write the unforgettable alliterating line in Sonnet 30: “And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste.”)

The pernicious habit of writing wh, sometimes for no obvious reason, resulted in the creation of several unetymological spellings. Whore, from Old English hore (a common Germanic noun), is akin to Latin carus “dear” (Italian caro, etc.). The Old English for whole was hal (with a long vowel). According to the OED, the spelling with wh-, corresponding to a widespread dialectal pronunciation with w, appeared in the sixteenth century. But why should this dialectal pronunciation have prevailed to such an extent that the spelling of an old and very common word was affected? Home also has a dialectal variant whoam, but, luckily, we still stay at home, rather than at whome. Equally puzzling is whelk (from weolc); here the influence of welk “pimple” has been pressed into service. Whig traces, though in a circuitous way, to a verb meaning “to drive”. Its wh- has no justification in history. Naturally, whim was bound to cause trouble, the more so as its earliest attested meaning is “pun”; no record of whim predates the seventeenth century. Then there is whiffler “an attendant armed with a weapon to keep the way clear for a procession,” from wifle “javelin” (Od Engl. wifel).

The consonant group hw- must always have made people think of blowing and light sweeping motions. Whistle, whisper, and whisk are rather obvious sound-imitating words (which does not mean that whisky ~ whiskey, from Gaelic, should have wh-; whisker, however, is derived for whisk, and its original sense was “brush”). Whir and whirl seem to belong with other onomatopoeic formations. Whew, an exclamation of astonishment, is an onomatopoeia pure and simple. Wheedle is late and has an obscure history.

Inglewhite, Lancashire. (Cowfield. Grazing south of Langley Lane. Photo by Chris Shaw. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.)

By way of conclusion, I may mention several thw- words in which thw- once alternated with hw-. Today we remember only the verb thwart, but the adjective thwart “obstinate, perverse” also existed, and over-hwart has been attested. Another archaic word thwite “to cut” is a cognate of whittle. Thwack and whack used to alternate, and thwack is a synonym of dialectal thack. Apparently, thw- too had a sound-imitative value. In the place name Inglewhite (Lancashire), the second element was thwaite “meadow.” The last name Applewhite goes back to the place name Applethwaite in Cumberland. The change of thwaite to white is a product of folk etymology.

All this is very interesting, except that wh- is often an unnecessary embellishment. For the benefit of those who like learned words I may say that this group is sometimes otiose.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Which witch? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for June 2014, part 2Marquises and other important people keeping up to the markA globalized history of “baron,” part 2

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for June 2014, part 2Marquises and other important people keeping up to the markA globalized history of “baron,” part 2

Roll over, Rimbaud: P. F. Kluge, Walt Whitman, and Eddie and the Cruisers

Ask folks who came of age in the 1980s what they remember about the movie Eddie and the Cruisers and one of the following responses is likely:

It spawned the great rock-radio staple “On the Dark Side” and briefly made MTV stars of the improbably named John Cafferty and the Beaver Brown Band.

It was such a shameless Bruce Springsteen rip-off that Boss fans considered it as sacrilegious as devout Christians do Jesus Christ Superstar.

It had a whiplash-inducing twist ending that Roger Ebert called “so frustrating, so dumb, so unsatisfactory that it gives a bad reputation to the whole movie.”

It was a box-office flop that thirty years ago this month shocked Hollywood by becoming a surprise HBO hit.

It was a movie you rented repeatedly during the decade’s video boom because it fit perfectly VHS’s promise of cheap home entertainment: undemanding, toe-tapping, and eminently re-watchable, it was an ideal 99-cent diversion that helped you forget VCRs cost $500 and were as boxy as Samsonite suitcases.

What you’re less likely to hear, unfortunately: it was based on one of the best, most criminally underappreciated rock ‘n’ roll novels ever.

In a preface to Overlook Press’s 2008 reissue (the book’s first widely available trade paperback), no less than Sherman Alexie admits he never knew Eddie was originally a novel by P. F. Kluge until deep into his own career, long after “obsessing” over the movie as a high-schooler. It’s indicative of how the film overshadows its source material that Kluge’s Eddie doesn’t even make this supposedly comprehensive list of rock novels published since the 1950s.

The novel’s relative obscurity is a shame, for as Alexie notes, it has literary “ambitions and secrets and qualities” that far surpass the movie’s “mainstream” pleasures. Director Martin Davidson, who co-wrote the script with his wife, Arlene, made several changes to Kluge’s tale of a Jersey rock star who may or may not be haunting former bandmates twenty years after his supposed death. The most significant is seemingly the most cosmetic. Whereas Kluge conceived hero Eddie Wilson as a Dion-esque doo-wop rocker, Davidson turned him into an awkward splice of Springsteen and Jim Morrison. In so doing, the filmmaker altered the literary inspiration that in Kluge gives the musician a model for imagining rock ‘n’ roll as an art form instead of mere entertainment. The change is decisive to how differently each version of Eddie depicts the purpose of popular music.

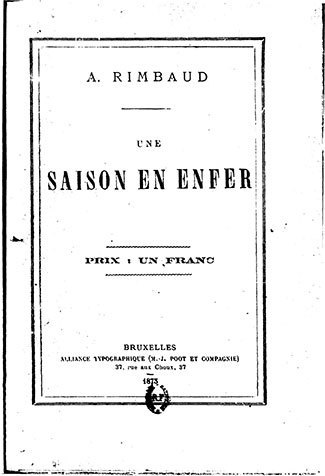

Une saison en enfer, Arthur Rimbaud, Bruxelles, Alliance typographique, 1873. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In the movie, college dropout Frank “Wordman” Ridgeway, the story’s Nick Carraway, introduces Eddie to the 19th-century French symboliste Arthur Rimbaud. Literature spurs the hunky frontman to make “serious” music instead of cranking out bar-band favorites for Jersey beachgoers: “I want songs that echo,” Eddie insists. “The [music] we’re doing now is like bed sheets. Spread ’em, soil ’em, ship ’em out to laundry. Our songs — I like to fold ourselves up in them forever.” Soon enough, Eddie pens a concept album called A Season in Hell, after Rimbaud’s most famous work. His slimy record-company owner refuses to release it, however, because the music sounds “like a bunch of jerkoffs making weird sounds.” The rejection sends Eddie squealing away in his ’57 Chevy, which hurtles off the Raritan Bridge, either an accident or a suicide. The Cruisers are forgotten for two decades later until an Entertainment Tonight-type reporter begins hyping Hell as an ominous foreshadowing of the late sixties, “a new age, an age of confusion, an age of passion, of commitment!” Suddenly, someone claiming to be the dead rock star is stalking the surviving Cruisers, intent on finally releasing the missing opus so the public can recognize Eddie’s brilliance.

Serious scholarly papers have drawn parallels between Eddie and Rimbaud, but the script’s invocation of the poet never really rises above literary window dressing. Davidson mainly uses Rimbaud to allude to Morrison, who idolized the literary libertine and who, according to a farcical urban legend, faked his 1971 death to escape the rock biz (much as Rimbaud abandoned literature before he was twenty). The movie asks us to believe that the Beatlemania-era Eddie predicted the Dionysian extremes of the Doors’ “The End” or (God help us) “Horse Latitudes,” but the song that’s supposed to illustrate his visionary genius, “Fire,” hardly qualifies as “weird sounds”. It’s merely an arthritic gloss on Springsteen’s “Adam Raised a Cain” with none of the Boss’s blistering vitality.

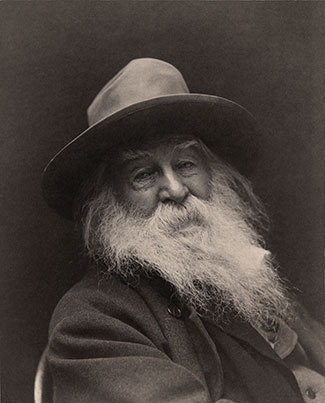

Walt Whitman. Photo by George C. Cox, restoration by Adam Cuerden. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

For Kluge’s Eddie, by contrast, the spirit father isn’t Rimbaud but Walt Whitman, and Eddie’s magnum opus is Leaves of Grass. Having seen Leaves appropriated to do everything from woo interns to expose unlikely meth kingpins, I’ll be the first to say that the Good Gray Poet’s popularity as the Go-To Lit Reference sometimes leaves me craving a Longfellow revival. Yet his role in Kluge isn’t gratuitous. Whitman inspires Eddie to reimagine rock ‘n’ roll as the vox populi, a medium not for becoming famous but for creating the true song of democracy. To produce his rock version of Leaves, Eddie recruits black and white greats from Elvis to Sam Cooke to Buddy Holly (the novel is set in 1957-58, a half-decade earlier than the film). Their mission is to snip the American barbed wire of segregation through a series of secret jam sessions designed to “to bring off the impossible, some fantastic union of black and white music.” What breakthroughs Eddie achieved before his supposed death is as compelling a page-turner as the mystery of who’s harassing the surviving Cruisers. (Spoiler alert: Eddie does not predict “Ebony and Ivory”).

In ditching Whitman for Rimbaud, Davidson’s film became a story not about the Gordian knot of race in American music but about rock-star greatness and fame. That point is bashed home like a gong by the movie’s trick ending, which reveals Eddie is indeed alive but indifferent to the hullaballoo the media creates when his masterwork is finally released. Despite the adaptation’s defects, Kluge speaks appreciatively of it, and rightly so: as a cult favorite, the movie kept the novel’s name alive during the decades the book was out of print. Besides, when the other movie based on your writing is Dog Day Afternoon, you can afford to be generous.

Nevertheless, the lack of attention Book Eddie receives feels like a missed opportunity for rock novels in general. The genre is a diverse, unruly one. Some of its entries are romans à clef that do little more than pencil fictional names into legends rock fans already know by heart (Paul Quarrington’s Brian Wilson-retelling Whale Music). Many others are coming-of-age novels in which that form’s traditional theme of lost innocence plays out like a Behind the Music episode, all downward-spiral cocaine and coitus. Still others are less about music-making than about the grotesquery of fame and fan worship (Don DeLillo’s Great Jones Street). What rock novels aren’t nearly as often about is race — or, at least, the alchemies of ethnic interchange explored in such great nonfiction music histories as Peter Guralnick’s Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom (1986). A handful of exceptions do come to mind, Alexie’s own Reservation Blues (1995) most notably. Yet for the most part storylines about ahead-of-their-time geniuses predominate, and frankly, the plot of making personal art instead of appeasing a hits-happy public is as tired as the playlist at my local oldies station.

The idea of rock ‘n’ roll as both the promise and impasse of a racially egalitarian barbaric yawp, on the other hand… That’s a song in fiction we still don’t hear nearly enough.

Kirk Curnutt is professor and chair of English at Troy University’s Montgomery, Alabama, campus, where Scott Fitzgerald met Zelda Sayre in 1918. His publications include A Historical Guide to F. Scott Fitzgerald (2004), the novels Breathing Out the Ghost (2008) and Dixie Noir (2009), and Brian Wilson (2012). He is currently at work on a reader’s guide to Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not. Read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Roll over, Rimbaud: P. F. Kluge, Walt Whitman, and Eddie and the Cruisers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIn remembrance of Elaine StritchWhat is consciousness?Contested sites on India’s Deccan Plateau

Related StoriesIn remembrance of Elaine StritchWhat is consciousness?Contested sites on India’s Deccan Plateau

What is the role of governments in climate change adaptation?

Adaptation to climate change is currently high on the agenda of EU bureaucrats exploring the regulatory scope of the topic. Climate change may potentially bring about changes in the frequency of extreme weather events such as heat waves, flooding or thunder storms, which in turn may require adaptation to changes in our living conditions. Adaptation to these conditions cannot stop climate change, but it can reduce the cost of climate change. Building dikes protects the landscape from an increase in sea level. New vaccines protect the population from diseases that may spread due to the change in the climate. Leading politicians, the media and prominent interest groups call for more efforts in adaptation.

But who should be in charge? Do governments have to play a leading role in adaptation? Will firms and households make the right choices? Or do governments have to intervene to correct insufficient or false adaptation choices? If intervention is necessary, will the policy have to be decided on a local level or on a national or even supranational (EU) level? In a recent article we review the main arguments for government intervention in climate change adaptation. Overall, we find that the role of the state in adaptation policy is limited.

In many cases, adaptation decisions can be left to private individuals or firms. This is true if private sector decision-makers both bear the cost and enjoy the benefits of their own decisions. Superior insulation of buildings is a good example. It shields the occupants of a building from extreme temperatures during cold winters and hot summers. The occupants – and only the occupants – benefit from the improved insulation. They also bear the costs of the new insulation. If the benefit exceeds the cost, they will invest in the superior insulation. If it does not pay off, they will refrain from the adaptation measure (and they should do so from an efficiency point of view). There is no need for government intervention in the form of building regulation or rehabilitation programmes.

In some other cases, adaptation affects an entire community as in the case of dikes. A single household will hardly be able – nor have the incentive – to build a dike of the appropriate size. But the local municipality can and should be able to so. All inhabitants of the municipality can share the costs and appropriate the benefit from flood protection. The decision on the dike could be made on the state level if not at the municipal level. The local population will probably have a long-standing experience and superior knowledge about the flood events and its potential damages. The subsidiarity principle, which is a major principle of policy task assignment in the European Union, suggests that the decisions should be made on the most decentralized level for which there are no major externalities between the decision-makers. In the case of the dike, the appropriate level for the adaptation measure would be the municipality. Again there is no need for intervention from upper-level governments.

So what role is left for the upper echelons of government in climate change adaptation? Firstly, the government has to help in improving our knowledge. Information about climate change and information about technical adaptation measures are typical public goods: the cost of generating the information has to be incurred once, whereas the information can be used at no additional cost. Without government intervention, too little information would be generated. Therefore, financing basic research in this area is one of the fundamental tasks for a central government.

Secondly, the government has to provide the regulatory framework for insurance markets. The economic consequences of natural disasters can be cushioned through insurance markets. However, the incentives to buy insurance are insufficient for several reasons. For instance, whenever a major disaster threatens the economic existence of a larger group of citizens, the government is under social pressure and will typically provide help to all those in need. By anticipating government support in case of a disaster, there is little or no incentive to buy insurance in the market. Why should they pay the premium for private insurance, or invest in self-insurance or self-protection measures if they enjoy a similar amount of free protection from the government? If the government wants to avoid being pressured for disaster relief, it has to make disaster insurance mandatory. And to induce citizens to the appropriate amount of self-protection, insurance premiums have to be differentiated according to local disaster risks.

Thirdly, fostering growth helps coping with the consequences of climate change and facilitates adaptation. Poor societies and population groups with low levels of education have the highest exposure to climate change, whereas richer societies have the means to cope with the implications of climate change. Hence, economic growth – properly measured – and education should not be dismissed easily as they act as powerful self-insurance devices against the uncertain future challenges of climate change.

Kai A. Konrad is Director at the Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance. Marcel Thum is Professor of Economics at TU Dresden and Director of ifo Dresden. They are the authors of the paper ‘The Role of Economic Policy in Climate Change Adaptation’ published in CESifo Economic Studies.

CESifo Economic Studies publishes provocative, high-quality papers in economics, with a particular focus on policy issues. Papers by leading academics are written for a wide and global audience, including those in government, business, and academia. The journal combines theory and empirical research in a style accessible to economists across all specialisations.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Flooding, July 2007, by Mat Fascoine. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What is the role of governments in climate change adaptation? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in QatarWhy measurement mattersIs the past a foreign country?

Related StoriesWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in QatarWhy measurement mattersIs the past a foreign country?

Why are women still paid less than men?

The recent firing of Jill Abramson, the first female executive editor of the New York Times, after less than three years on the job focused the news cycle on gender inequity, with discussions of glass cliffs (women get shorter leashes even when they get the top jobs) and reports showing the persistence of glass ceilings and pay disparities (e.g. Abramson was paid less than her male predecessor). In the United States, women now represent a substantial majority of those earning advanced degrees. Yet as we look higher and higher up the ladders of career attainment, we see smaller and smaller percentages of women – as well as the persistence of pay gaps for women, even in senior positions. In other words, even as women break through one glass ceiling, they encounter another on the next rung.

Take law firms. Women make up almost half of US law school graduates (up from 5% in 1950). But they represent only 20% of US law firm partners and an even smaller share (16%) of the more elite class of equity partners. And the higher one looks within the partnership stratosphere, the less diverse it gets. Furthermore, the leaders of the profession, as well as clients of law firms, express frustration with the slow pace of progress in generating more gender and ethnic equality at the top of the profession. These efforts can be aided by improving our understanding of the work and career processes within law firms and, by extension, partnerships in other professional fields, such as accounting, consulting, and investment banking.

So how exactly do partners rise to different levels within the partnership hierarchy, and how do those processes challenge female partners? To date, researchers have analyzed the challenge of becoming a partner, but we know curiously little about how professional careers unfold after that. Although partners at large law firms may all be one-percenters, they are certainly not equal, with distinctions made between equity and non-equity partners, and recent surveys showing some “super-partners” earn up to 25 times more than their peers.

To get at these questions, we studied how partners gain power within a partnership, as measured by their “book of business” – the fees paid to the firm by clients with whom the partner holds the primary relationship. The more client revenue that a partner is responsible for, the more that partner will hold influence in their firm, command respect, and generate career mobility options in the wider profession. To understand power in a partnership, then, is to understand how partners come to obtain books of business.

What we found was intriguing. In short, although women may be disadvantaged in a primary “path to power” in the partnership, they may have opportunities along a second pathway of growing importance.

The primary pathway involves “inheriting” clients from an established power partner. To build a book of business, one needs to either pursue that strategy, or the alternative of “making rain” by bringing new clients to the firm. A newly minted partner thus needs to decide which path to invest in—or how much to invest in each path. Do you spend time working for clients of power partners nearing retirement—or pounding the pavement (or the cocktail circuit) seeking new clients of your own? Of course, each path has its risks. Investing in the inheritance path can backfire, for example, if a retiring benefactor bequeaths a client to a rival partner. And the rainmaking strategy can backfire if nibbles of new-client business don’t eventually turn into a large revenue stream for the firm. Since both investments require time and energy, what’s the optimal career strategy?

Deepening the puzzle, both paths are also likely to pose particular challenges to female attorneys, as they depend on forming social relationships with either the senior power partners or with decision makers at potential new client firms. Much research shows the existence of “homophily” in interpersonal relationships, or the tendency for people to be drawn to and feel greater affinity for people who are like themselves in terms of race and gender. So where senior partners and/or client decision makers are largely male, female junior partners may be at a disadvantage in forming the bonds of affinity or trust that help win the client business.

Analysis of the internal records of law firms shows, unsurprisingly, that female partners have smaller books of business than their male peers. More interestingly, though, we are finding that the rate of return on investments in the two paths to power differs between men and women. In fact, the inheritance strategy appears to be a particularly poor investment for women. For women, larger investments in the inheritance path are associated with lower future books of business. Why? We speculate this could be because of “selective affinity.” That is, when it comes time for the power partners to pass on their clients, they may unconsciously favor partners who are more demographically similar to them.

Yet, when it comes to the rainmaking strategy, the opposite may be true. For female partners, investments in the rainmaking path appear to pay handsomely. In fact even better than for male partners. Why could that be? Perhaps female partners recruit new clients in different ways than male partners, or perhaps “selective affinity” can actually favor female partners in the open marketplace (rather than the closed ecosystem of the firm’s internal networks).

What does it all mean? First off, for partnerships, there may be considerable value in studying the inheritance and rainmaking processes going on in their own organizations. Virtually all firms now have the relevant internal data waiting to be analyzed. Second, our findings are important for managing diversity in partnerships. For example, the results suggest there could be a “double payoff” to supporting rainmaking efforts for newly-made female partners – double in the sense of the firm’s overall revenue generation as well as diversity goals.

Forrest Briscoe is an Associate Professor of Management in the Smeal College of Business, Pennsylvania State University. His research focuses on careers, networks, and management processes in professional organizations, as well as on the factors that promote and inhibit changes within organizational fields. Andrew von Nordenflycht is an Associate Professor at Simon Fraser University’s Beedie School of Business. His research focuses on the challenges of managing professional services firms, the patterns of professional careers, and the impact of different organizational forms on the performance, creativity, and ethics of professionals. Andrew is the author of the paper ‘Does the emergence of publicly traded professional service firms undermine the theory of the professional partnership? A cross-industry historical analysis’ published in the Journal of Professions and Organization.

The Journal of Professions and Organization (JPO) aims to be the premier outlet for research on organizational issues concerning professionals, including their work, management and their broader social and economic role.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Fresh and confident corporate businesswoman, © Squaredpixels, via iStock Photo.

The post Why are women still paid less than men? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in QatarWhy measurement mattersProfessionals’ implication in corporate corruption

Related StoriesWorld Cup puts spotlight on rights of migrant workers in QatarWhy measurement mattersProfessionals’ implication in corporate corruption

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers