Oxford University Press's Blog, page 780

August 4, 2014

Did Napoleon cause his own downfall?

On 9 April 1813, only four months after his disastrous retreat from Moscow, Napoleon received the Austrian ambassador, Prince Schwarzenberg, at the Tuileries palace in Paris. It was a critical juncture. In the snows of Russia, Napoleon had just lost the greatest army he had ever assembled – of his invasion force of 600,000, at most 120,000 had returned. Now Austria, France’s main ally, was offering to broker a deal – a compromise peace – between Napoleon and his triumphant enemies Russia and England. Schwarzenberg’s visit to the Tuileries was to start the negotiations.

Schwarzenberg’s description of the meeting is one of the most revealing insights into Napoleon’s character from any source. In place of the imperious conqueror of only ten months before, Schwarzenberg now saw a man who feared ‘being stripped of the prestige he [had] previously enjoyed; his expression seemed to ask me if I still thought he was the same man.’

To Schwarzenberg’s dismay, when it came to peace Napoleon still showed his old obstinacy and unwillingness to make concessions. The reason for this, however, was unexpected. It concerned not diplomacy or the military situation, but Napoleon’s domestic position in France. He told Schwarzenberg:

“If I made a dishonourable peace I would be lost; an old-established government, where the links between ruler and people have been forged over centuries can, if circumstances demand, accept a harsh peace. I am a new man, I need to be more careful of public opinion … If I signed a peace of this sort, it is true that at first one would hear only cries of joy, but within a short time the government would be bitterly attacked, I would lose … the confidence of my people, because the Frenchman has a vivid imagination, he is tough, and loves glory and exaltation.”

Napoleon’s reluctance to make peace at this key moment has been generally ascribed to his gambling instinct, a refusal to accept that Destiny might desert him, and a desperate belief he could still defeat his enemies in battle even now. The idea that fear might also have played a part seems so alien to Napoleon’s character that it has rarely been considered.

Napoleon, by Paul Delaroche. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Napoleon was convinced, as his words to Schwarzenberg made clear, that the best way of anchoring any new régime was through military glory. Nowhere was this truer, he felt than in France, which had just undergone a revolution of unprecedented scale and violence. He genuinely feared that a sudden loss of international prestige could reopen the divisions he had spent fifteen years trying to close.

This fear may well have originated in a particular early experience. On 10 August 1792, as a young officer, Napoleon had witnessed one of the climactic moments of the French Revolution, the storming of the Tuileries by the Paris crowd and the overthrow of King Louis XVI. It was the first fighting he had ever seen. He had been horrified by the subsequent massacre of the Swiss Guards and the accompanying atrocities. For Napoleon, this trauma also held a political lesson. Louis XVI had been dethroned because he had failed to show sufficient enthusiasm for a revolutionary war, and because his people had come to susepct his patriotism. Napoleon’s words to Schwarzenberg two decades later show his determination not to make the same mistake.

Significantly, when the prospect of a compromised peace appeared close during 1813 and 1814, Napoleon always used this same argument to counter it: his own rule over France would not survive an inglorious peace. He did this most dramatically on 7 February 1814. With France already invaded, his enemies offered to let him keep his throne if he renounced all of France’s conquests since the Revolution. His closest advisers urged him to accept, but he burst out: “What! You want me to sign such a treaty … What will the French people think of me if I sign their humiliation? … You fear the war continuing, but I fear much more pressing dangers, to which you’re blind.” That night, he wrote an apocalyptic letter to his brother Joseph, making it clear that he preferred his own death, and even that of his son and heir, to such a prospect.

Napoleon himself obviously believed that peace without victory would seriously threaten his dynasty. Was he right? My own view, based on researching the state of French public opinion at the time, is that he was not. The overwhelming majority of reports show the French people in 1814 as exhausted by endless war and its burdens. They were desperate for peace. Ironically, it was not concessions for the sake of peace, but his determination to go on fighting, that eventually undermined Napoleon’s domestic support. By refusing to recognize this, Napoleon did indeed cause his own downfall.

Munro Price is a historian of modern French and European history, with a special focus on the French Revolution, and is Professor of Modern European History at Bradford University. His publications include The Fall of the French Monarchy: Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and the baron de Breteuil, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions, and The Road to Apocalypse: the Extraordinary Journey of Lewis Way (2011). Napoleon: The End of Glory publishes this month.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Did Napoleon cause his own downfall? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914The month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914The month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914

August 3, 2014

Transforming conflict into peace

My research has focused on the use of participatory media in conflict-affected communities. The aim has been to demonstrate that involving community members in a media production provides them with a platform to tell their story about the violence they have experienced and the causes they believe led to it. This facilitates the achievement of a shared understanding of the conflict between groups that were fighting and lays the foundations for the establishment of a new social fabric that encompasses peace.

This is, by no means, an easy process. It is also one that requires the co-implementation of different types of interventions that strive to rebuild peace in those areas. However, what is often lacking in post-conflict contexts is a communication channel that allows people to reconnect. In the aftermath of civil violence, communities are left divided and in need of information to make sense of the brutality they have undergone. Victims and perpetrators live side by side as neighbours, and dynamics based on resentment and hatred hinder the return to a peaceful environment. The mass media are often unable to address the tensions that have remained within communities as a legacy of the conflict; hence, it is crucial to provide a platform where formerly opposing groups can articulate their views.

By drawing on the experience of a participatory video project conducted in the Rift Valley of Kenya after the 2007/2008 Post-Election Violence, when the country underwent a period of intense ethnic violence, I was able to demonstrate the potential of Communication for Social Change in post-conflict settings through the use of participatory video.

Social change is a process that seeks to transform the unequal power relations that affect a community. The literature on conflict studies tells us that, in order to achieve social change, what firstly needs to be targeted in conflict interventions is change both at the individual and relational level. Changing individuals requires adjusting their feelings and behaviours towards other groups, while changing relationships is about creating a meaningful interaction between members opposing groups, which results in the improvement of inter-group relations. This can be represented as follows:

I argue that, from a communication perspective, these changes can be achieved when people participate in the production of a media story that allows them to both reflect upon and become aware of their situation, as well as to share their experience and create an understanding among groups.

In particular, collaborating towards the creation of media content, listening to one another and becoming producers of their own story, allows communities to transform conflict at all levels:

Individual change – participatory video activities contribute to instating participants’ confidence in re-establishing peace, helping them identify themselves as agents of change, and also guiding them in the discovery of new skills. The storytelling process people engage with encourages reflection on their actions during the violence and greater awareness of their present situation and the need to rebuild peace.

Relational change – the participatory video-making process can establish harmony among those who work together in the mixed-tribe workshops. These involve both those who are in front of the camera but also who cover other roles during the production process. Those who watch the final videos through public screenings can exchange views and develop an understanding of the situation for both victims and perpetrators.

Social change – Thanks to the power shifts resulting from newly-developed perceptions of the conflict and of their post-conflict environment, members of different groups begin to engage in dialogue. The existence of different realities of the violence and of the need to move forward are acknowledged, laying the foundations that are needed to begin to build a new social fabric.

A Communication for Social Change approach to peacebuilding recognises how changes at the individual and relational level can be addressed both through the media content production process and the screening of the final media outputs in the community. Within this context, participatory video is seen as a catalyst that can initiate processes of conflict transformation that lead to a wider social change.

Valentina Baú is completing a PhD at Macquarie University (Sydney, Australia). Both as a practitioner and as a researcher, her work has focused on the use of communication in international development. Valentina has collaborated with different international NGOs, the United Nations and the Italian Development Cooperation, in various African countries. Her doctoral research has looked at the use of Communication for Development in Peacebuilding, particularly through the use of participatory media. Valentina Baú is the author of ‘Building peace through social change communication: participatory video in conflict-affected communities‘, in the Community Development Journal.

Community Development Journal is the leading international journal in its field, covering a wide range of topics, reviewing significant developments and providing a forum for cutting-edge debates about theory and practice. It adopts a broad definition of community development to include policy, planning and action as they impact on the life of communities.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social work articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Flow chart of social change, by Valentina Baú. Do not re-use without permission.

The post Transforming conflict into peace appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Q&A with Professor Stefan AgewallWhat are the costs and impacts of telecare for people who need social care?Education and crime over the life cycle

Related StoriesA Q&A with Professor Stefan AgewallWhat are the costs and impacts of telecare for people who need social care?Education and crime over the life cycle

Five myths about the “surge” of Central American immigrant minors

Both the President and Senate Republicans have recently weighed in on what to do about the “surge” in undocumented minors arriving at the US border. Many of these undocumented youth come from the northern countries of Central America: Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Embedded in most arguments about what ought to be done are assertions about what prompted these minors to set out in the first place and what will become of them if they stay. But many of these assumptions miss the mark and the truth is a lot more complicated than the sloganeering that characterizes much of the debate.

Myth #1: The increase in migrating minors came about as a result of the rise of gang violence in Central America.

Gang violence in Central America is real and it has touched the lives of far too many Central American youth and families. But the gangs have been a major feature of urban life since at least the late 1990s and there is little evidence to argue that gangs have increased in strength, size, or activity during the past three years. Meanwhile, the increase in migration of minors has been stratospheric. Undeniably, some of the youth heading north are escaping gang violence or threats from the gangs, but even the UN’s special report Children on the Run found, after conducting interviews with a scientific sample of detained youth, that just under a third of the youth mentioned the gangs as a factor contributing to their decision to leave. Most of the youth citing gangs were from El Salvador and Honduras.

Myth #2: Violence is spiraling out of control throughout Central America.

Although they share a number of important characteristics, the governments of Central America have taken different paths in how to relate to gangs, drugs, and violent crime. These divergent policies have contributed to very distinct outcomes. Notably, Nicaragua, which never took an “iron fist” approach to the gangs, has a far lower homicide rate and lower gang membership than its neighbors to the north. But even Guatemala, which has been well-known for homicidal violence ever since the state-sponsored violence of the 1980s, has shown improvement in its violent crime rate. Homicides have generally declined in recent years, probably as a partial result of Guatemala’s efforts to improve its justice system. As the chart below illustrates, Honduras has more than double the homicidal violence of its neighbors:

Myth #3: Coyotes (sometimes called “human traffickers”) are “tricking” children into migrating by telling them that they will receive citizenship upon arrival in the United States.

This myth reveals the utterly low regard in which many North Americans hold the intelligence of Central Americans. Oscar Martinez, an award-winning investigative journalist from El Salvador, recently published a fascinating account of his interview with a Salvadoran coyote who has been guiding his compatriots to El Norte since the 1970s. (Oscar knows about migrating minors — he has written a celebrated book about his trips across Mexico in the company of Central American migrants.) Among other myths effectively debunked in that interview is the notion that Central Americans hold wildly optimistic views about Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In fact, most Central American youth and their relatives living in the United States are well aware that in all likelihood, they will, at best, become undocumented immigrants. But better to be close to family than suffer years of hardship while separated from parents, many of whom cannot travel “back” to their country of origin because of their own undocumented status. Of course, some of these youth are also escaping violence and the threat of violence as well as economic hardship and the crushing humiliation of living in generational poverty in some of the most unequal societies in the hemisphere. Thus, there are multiple factors at play when Central American youth (and their parents) consider whether or not to pay the US$7,000 charged by most coyotes for “guidance” across Mexico and over the US border. But few arrive under the illusion that they will attain legal status any time soon.

Myth #4: Central American youth who manage to stay in the United States as undocumented persons are likely to become part of a permanent underclass who represent a perpetual drain on the US economy.

Political conservatives often argue that our economy simply cannot sustain the weight of more undocumented Mexicans and Central Americans. In fact, research at the Pew Hispanic Center shows that 92% of undocumented men are active in the labor force (a higher proportion than among native men) and that most undocumented immigrants see modest improvements in their household income over time. Not surprisingly, those who eventually obtain legal status show far more substantial gains in their income and in the educational attainment of their children.

Myth #5: The situation in Central America is hopeless.

While it is true that many of the children who reach the US border have grown up in difficult and even dangerous situations and ought to be granted a hearing to determine whether or not they should be granted asylum, I have Central American friends (including some from Honduras) who might bristle at the suggestion that every child migrating northward is escaping life in hell itself. The idea that all Central American minors ought to be pronounced refugees upon arrival at the border rests on the mistaken assumption that these nations are hopelessly mired in violence and chaos, and it encourages the US government to throw in the towel with regard to advocating for economic and political improvements in the region.

True, a great deal of violence and hopelessness persists in the marginal urban neighborhoods of San Salvador and Tegucigalpa, but these communities did not evolve by accident. They are the result of years of under-investment in social priorities such as public education and public security compounded by the entrance in the late 1990s of a furious scramble among the cartels to establish and maintain drug movement and distribution networks across the isthmus in order to meet unflagging US demand. At the same time as we work to ensure that all migrant minors are treated humanely and with due process, we ought to use this moment to take a hard look at US foreign policy both past and present in order to build a robust aid package aimed at strengthening institutions and promoting more progressive tax policy so that these nations can promote human development, not just economic growth. It is time we take the long view with regard to our neighbors to the south.

Robert Brenneman is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Saint Michael’s College in Colchester, Vermont and the author of Homies and Hermanos: God and the Gangs in Central America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five myths about the “surge” of Central American immigrant minors appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy metaphor mattersHumanitarian protection for unaccompanied children from Central AmericaPhotography and social change in the Central American civil wars

Related StoriesWhy metaphor mattersHumanitarian protection for unaccompanied children from Central AmericaPhotography and social change in the Central American civil wars

The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

At 7 a.m. Monday morning the reply of the Belgian government was handed to the German minister in Brussels. The German note had made ‘a deep and painful impression’ on the government. France had given them a formal declaration that it would not violate Belgian neutrality, and, if it were to do so, ‘the Belgian army would offer the most vigorous resistance to the invader’. Belgium had always been faithful to its international obligations and had left nothing undone ‘to maintain and enforce respect’ for its neutrality. The attack on Belgian independence which Germany was now threatening ‘constitutes a flagrant violation of international law’. No strategic interest could justify this. ‘The Belgian Government, if they were to accept the proposals submitted to them, would sacrifice the honour of the nation and betray at the same time their duties towards Europe.’

Belgian Prime Minister Charles de Brocqueville. By Garitan CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

When the British cabinet reconvened later that morning at 11 a.m. there were now four ministers prepared to resign over the issue of British intervention. Their discussion lasted for three hours, at the end of which they agreed on the line to be taken by Sir Edward Grey when he addressed the House of Commons at 3 p.m. ‘The Cabinet was very moving. Most of us could hardly speak at all for emotion.’Grey began his address to the House by explaining that the present crisis differed from that of Morocco in 1912. That had been a dispute which involved France primarily, to whom Britain had promised diplomatic support, and had done so publicly. The situation they faced now had originated as a dispute between Austria and Serbia – one in which France had become engaged because it was obligated by honour to do so as a result of its alliance with Russia. But this obligation did not apply to Britain. ‘We are not parties to the Franco-Russian Alliance. We do not even know the terms of that Alliance.’

But, because of their now-established friendship, the French had concentrated their fleet in the Mediterranean because they were secure in the knowledge that they need not fear for the safety of their northern and western coasts. Those coasts were now absolutely undefended. ‘My own feeling is that if a foreign fleet engaged in a war which France had not sought, and in which she had not been the aggressor, came down the English Channel and bombarded and battered the undefended coasts of France, we could not stand aside and see this going on practically within sight of our eyes, with our arms folded, looking on dispassionately, doing nothing!’ The government felt strongly that France was entitled to know ‘and to know at once!’ whether in the event of an attack on her coasts it could depend on British support. Thus, he had given the government’s assurance of support to the French ambassador yesterday.

There was another, more immediate consideration: what should Britain do in the event of a violation of Belgian neutrality? He warned the House that if Belgium’s independence were to go, that of Holland would follow. And what…

‘If France is beaten in a struggle of life and death, beaten to her knees, loses her position as a great Power, becomes subordinate to the will and power of one greater than herself’? If Britain chose to stand aside and ‘run away from those obligations of honour and interest as regards the Belgian Treaty, I doubt whether, whatever material force we might have at the end, it would be of very much value…’

‘I do not believe for a moment, that at the end of this war, even if we stood aside and remained aside, we should be in a position, a material position, to use our force decisively to undo what had happened in the course of the war, to prevent the whole of the West of Europe opposite to us—if that had been the result of the war—falling under the domination of a single Power, and I am quite sure that our moral position would be such as to have lost us all respect.’

While Grey was speaking in the House the king and queen were driving along the Mall to Buckingham Palace in an open carriage, cheered by large crowds. In Berlin the Russian ambassador was being attacked by a mob wielding sticks, while the German chancellor was sending instructions to the ambassador in Paris to inform the French government that Germany considered itself to now be ‘in a state of war’ with France. At 6 p.m. the declaration was handed in at Paris:

‘The German administrative and military authorities have established a certain number of flagrantly hostile acts committed on German territory by French military aviators. Several of these have openly violated the neutrality of Belgium by flying over the territory of that country; one has attempted to destroy buildings near Wesel; others have been seen in the district of the Eifel, one has thrown bombs on the railway near Karlsruhe and Nuremberg.’

The French president welcomed the declaration. It came as a relief, Poincaré said, given that war was by this time inevitable.

‘It is a hundred times better that we were not led to declare war ourselves, even on account of repeated violations of our frontier…. If we had been forced to declare war ourselves, the Russian alliance would have become a subject of controversy in France, national [élan?] would have been broken, and Italy may have been forced by the provisions of the Triple Alliance to take sides against us.’

When the British cabinet met again briefly in the evening they had before them the text of the German ultimatum to Belgium and the Belgian reply to it. They agreed to insist that the German government withdraw the ultimatum. After the meeting Grey told the French ambassador that if Germany refused ‘it will be war’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914

A Q&A with Professor Stefan Agewall

As the European Society of Cardiology gets ready to welcome a new journal to its prestigious family, we meet the Editor-in-Chief, Professor Stefan Agewall, to find out how he came to specialise in this field and what he has in store for the European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy.

What encouraged you to pursue a career in the field of cardiology?

I qualified as a doctor at Göteborg University in Sweden in 1986. I became fascinated by emergency medicine early on in my career. I was soon drawn to cardiology as it covers such a broad spectrum of medicine, from acute emergency medicine to physiology, invasive and non-invasive examination and treatment techniques, pharmacology and cardiovascular prevention. I have mainly worked at coronary care units; first at the coronary care unit of Sahlgrenska University Hospital and then at Karolinska University Hospital in Sweden. At Karolinska, I was the head of the coronary care unit. In 2006 I became professor in Cardiology and moved to Oslo University Hospital.

What do you think are the challenges being faced in the field of cardiovascular pharmacotherapy today?

Professor Stefan Agewall, the new Editor-in-Chief of European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacological treatment is very good now and the mortality rate in patients with acute coronary syndrome is quite low. Clinical studies therefore need to be huge in order to demonstrate beneficial effects on hard end-points. We need to put more focus on quality of life in these larger studies and it is also extremely important that some emphasis is placed on preventive medicine, both with and without pharmacotherapy.

How do you see this field developing in the future?

Although the market place for cardiology-related journals is crowded and competitive, I believe the new publication will cover an area that has changed dramatically over the last few decades. This new journal will focus specifically on clinical cardiovascular pharmacology. The production of papers within this area is enormous; in Medline there are almost 500,000 references to the search term ‘cardiovascular pharmacology’ and the rate of publication in this field appears to be steadily increasing. Despite this fast development, we still need even more data from pharmacology studies aimed at improving prognosis for cardiovascular disease as it remains the most common cause of death world-wide.

What are you most looking forward to about being Editor-in-Chief for EHJ-Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy?

I am looking forward to launching this key new journal and establishing it as a member of the European Society of Cardiology journal family. I hope and believe the Journal will help readers to improve their knowledge in pharmacological treatment of patients with cardiovascular disease through the publication of high quality original research and reviews.

What does your typical day as the Editor-in-Chief look like?

Each day, I will start by handling new submissions and making decisions on papers which have been reviewed by experts within the field. If the submitted papers are of potential interest, they will be sent out for review. We have already recruited a fantastic editorial board, which guarantees a high quality review process. Time will be spent at different kinds of meetings to consider how to develop the journal, how to market it, and how to attract quality submissions from authors in the field.

How do you see the journal developing in the future?

The number of submissions to the journal will hopefully increase every year. In 2015 we aim for four issues and the number of issues will increase year on year. Monthly publication is a goal to achieve within five years. We will of course aim for an increasing impact factor and to become number one within the field of cardiovascular pharmacotherapy.

What do you think readers will take away from the journal?

We hope that by inviting respected and well-known authors, readers will be provided with excellent review papers. We want to provide readers with new information about cardiovascular therapy and, above all, we hope to help the readers to interpret and integrate new scientific developments within the area of cardiovascular pharmacotherapy.

European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy is an official journal of the European Society of Cardiology and the Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. This Journal will launch in 2015 and aims to publish the highest quality research, interpreting and integrating new scientific developments within the field of cardiovascular pharmacotherapy. The overarching goal of the Journal is to improve the care of patients with cardiovascular disease with a specific focus on cardiovascular pharmacotherapy.

Submit today to become part of this exciting new community. Read the Instructions to Authors for more information.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Headshot courtesy of Professor Stefan Agewall. Do not re-use without permission.

The post A Q&A with Professor Stefan Agewall appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat are the costs and impacts of telecare for people who need social care?A revolution in trauma patient careLimiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemic

Related StoriesWhat are the costs and impacts of telecare for people who need social care?A revolution in trauma patient careLimiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemic

Why metaphor matters

Plato famously said that there is an ancient quarrel between philosophy and poetry. But with respect to one aspect of poetry, namely metaphor, many contemporary philosophers have made peace with the poets. In their view, we need metaphor. Without it, many truths would be inexpressible and unknowable. For example, we cannot describe feelings and sensations adequately without it. Take Gerard Manley Hopkins’s exceptionally powerful metaphor of despair:

selfwrung, selfstrung, sheathe- and shelterless,

thoughts against thoughts in groans grind.

How else could precisely this kind of mood be expressed? Describing how things appear to our senses is also thought to require metaphor, as when we speak of the silken sound of a harp, the warm colours of a Titian, and the bold or jolly flavour of a wine. Science advances by the use of metaphors – of the mind as a computer, of electricity as a current, or of the atom as a solar system. And metaphysical and religious truths are often thought to be inexpressible in literal language. Plato condemned poets for claiming to provide knowledge they did not have. But if these philosophers are right, there is at least one poetic use of language that is needed for the communication of many truths.

In my view, however, this is the wrong way to defend the value of metaphor. Comparisons may well be indispensable for communication in many situations. We convey the unfamiliar by likening it to the familiar. But many hold that it is specifically metaphor – and no other kind of comparison – that is indispensable. Metaphor tells us things the words ‘like’ or ‘as’ never could. If true, this would be fascinating. It would reveal the limits of what is expressible in literal language. But no one has come close to giving a good argument for it. And in any case, metaphor does not have to be an indispensable means to knowledge in order to be as valuable as we take it to be.

Metaphor may not tell us anything that couldn’t be expressed by other means. But good metaphors have many other effects on readers than making them grasp some bit of information, and these are often precisely the effects the metaphor-user wants to have. There is far more to the effective use of language than transmitting information. My particular interest is in how art critics use metaphor to help us appreciate paintings, architecture, music, and other artworks. There are many reasons why metaphor matters, but art criticism reveals two reasons of particular importance.

Take this passage from John Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice. Ruskin describes arriving in Venice by boat and seeing ‘the long ranges of columned palaces,—each with its black boat moored at the portal,—each with its image cast down, beneath its feet, upon that green pavement which every breeze broke into new fantasies of rich tessellation’, and observing how ‘the front of the Ducal palace, flushed with its sanguine veins, looks to the snowy dome of Our Lady of Salvation’.

One thing Ruskin’s metaphors do is describe the waters of Venice and the Ducal palace at an extraordinary level of specificity. There are many ways water looks when breezes blow across its surface. There are fewer ways it looks when breezes blow across its surface and make it look like something broken into many pieces. And there are still fewer ways it looks when breezes blow across its surface and make it look like something broken into pieces forming a rich mosaic with the colours of Venetian palaces and a greenish tint. Ruskin’s metaphor communicates that the waters of Venice look like that. The metaphor of the Ducal palace as ‘flushed with its sanguine veins’ likewise narrows the possible appearances considerably. Characterizing appearances very specifically is of particular use to art critics, as they often want to articulate the specific appearance an artwork presents.

A second thing metaphors like Ruskin’s do is cause readers to imagine seeing what he describes. We naturally tend to picture the palace or the water on hearing Ruskin’s metaphor. This function of metaphor has often been noted: George Orwell, for instance, writes that ‘a newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image’.

Why do novel metaphors evoke images? Precisely because they are novel uses of words. To understand them, we cannot rely on our knowledge of the literal meanings of the words alone. We often have to employ imagination. To understand Ruskin’s metaphor, we try to imagine seeing water that looks like a broken mosaic. If we manage this, we know the kind of look that he is attributing to the water.

Imagining a thing is often needed to appreciate that thing. Knowing facts about it is often not enough by itself. Accurately imagining Hopkins’s despondency, or the experience of arriving in Venice by boat, gives us some appreciation of these experiences. By enabling us to imagine accurately and specifically, metaphor is exceptionally well suited to enhancing our appreciation of what it describes.

James Grant is a Tutorial Fellow in Philosophy at Exeter College, Oxford. He is the author of The Critical Imagination.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Hermann Herzog: Venetian canal, by Bonhams. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why metaphor matters appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of JulyA Q&A with John Ferling on the American RevolutionThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914

Related StoriesRhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of JulyA Q&A with John Ferling on the American RevolutionThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914

August 2, 2014

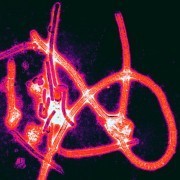

Limiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemic

With the Ebola virus in the news recently, you may be wondering what actions you can take to reduce the risk of contracting and spreading the deadly disease. Expert Peter C. Doherty provides valuable pointers on the best ways to stay safe and healthy in this excerpt from Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know answering: Is there anything that I can do personally to limit the possibility of a dangerous pandemic?

While pandemics are by their nature unpredictable, there are some things worth considering when it comes to the issue of personal safety and responsibility. The first point is to be a safe international traveler so that you don’t bring some nasty infection home with you. Protect yourself and you protect others. Though taking the available vaccines won’t prevent infection with some novel pathogen, it will contribute toward ensuring that you enjoy a successful vacation or business trip, and it should also put you in a “think bugs” mind-set. If, for instance, you are off to Africa for a wildlife safari, make an appointment at a travel clinic (or with your primary care physician) two to three months ahead of time to check your vaccine status and, if needed, receive booster shots to ensure that your antibody levels are high. Anyone who is visiting a developing country should make sure that he or she has indeed received the standard immunizations of childhood. Adolescents and young adults are much more likely to suffer severe consequences if, for instance, they contract commonplace infections like measles or mumps that have, because of herd immunity, become so unusual in Western countries that a minority of parents reject the collective responsibility of vaccinating their kids. If you’re younger and your parents are (or were) into alternative lifestyles, it may be wise to ask them very directly about your personal immunization history.

It’s also likely that, even if you were vaccinated early on, your level of immunity will have declined greatly and you will benefit from further challenge. Both possibilities will be covered if you go to a comprehensive travel clinic, as the doctors and nurses there will insist that you receive these shots (or a booster) if you don’t have a documented recent history. Any vaccination schedule should ideally be completed at least 3 to 4 weeks ahead of boarding your flight, the time needed for the full development of immunity. But this is one situation where “better late than never” applies. Should it have slipped your mind until the last minute, you should be vaccinated nevertheless. Even if you’ve never had that particular vaccine before, some level of protection could be there within 5 to 10 days, and a boosted, existing response will cut in more quickly. A travel clinic will also sell you a Gastro (gastroenteritis, not gastronomy) kit containing antibiotics to counter traveler’s diarrhea (generally a result of low-grade E. coli infection), something to decrease intestinal/gastric motility (Imodium), and sachets of salts to restore an appropriate fluid balance.

For the elderly, be aware of the decline in immunity that happens with age. You may not respond to vaccines as well as those who are younger, and you will be at greater risk from any novel infection. Depending on your proposed itinerary, it may also be essential to take anti-malarial drugs, which generally have to be started well ahead of arrival. Malaria is not the only mosquito-borne threat in tropical countries, so carry a good supply of insect repellant. In general, think about when and where you travel. Avoiding the hot, wet season in the tropics may be a good idea, both from the aspect that too much rain can limit access to interesting sites and because more standing water means more mosquitoes. Wearing long trousers, long-sleeved shirts, and shoes and socks helps to protect against being bitten (both by insects and by snakes), while also minimizing skin damage due to higher UV levels. Then, before you make your plans and again prior to embarking, check the relevant websites at the CDC, the WHO, and your own Department of Foreign Affairs (Department of State in the United States) for travel alerts. Especially if they’re off to Asia, many of my medical infectious disease colleagues travel with one or other of the antiviral drugs (Relenza and Tamiflu) that work against all known influenza strains. These require a prescription, but they’re worth having at home anyway in case there is a flu pandemic. If that happens, the word will be out that influenza is raging and stocks in the pharmacies and drugstores will disappear very quickly. But don’t rely on self-diagnosis if you took your Tamiflu with you to some exotic place; see a doctor. What you may think is flu could be malaria.

For those who may be sexually active with a previously unknown partner, carry prophylactics (condoms) and behave as responsibly as possible. Excess alcohol intake increases the likelihood that we will do something stupid. Dirty needles must be avoided, but don’t inject drugs under any circumstances. Blood-borne infections with persistently circulating viruses (HIV and hepatitis B and C) are major risks, while insect-transmitted pathogens (dengue, Chikungunya, Japanese B encephalitis) can also be in the human circulation for 5–10 days. Apart from that, being caught with illegal drugs can land you in terrible trouble, particularly in some Southeast Asian nations. No matter what passport you carry, you are subject to the laws of the country. Be aware that rabies may be endemic and that animal bites in general can be dangerous.

Can you really trust a tattooist to use sterile needles? Even if the needles are clean, what about the inks? How can they be sterilized to ensure that they are not, as has been known to occur, contaminated with Mycobacterium chelonae, the cause of a nasty skin infection? And that was in the United States, not in some exotic location where there may be much nastier bugs around.

Peter C. Doherty is Chairman of the Department of Immunology at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, and a Laureate Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Melbourne. He is the author of Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know, The Beginner’s Guide to Winning the Nobel Prize: Advice for Young Scientists, Their Fate is Our Fate: How Birds Foretell Threats to Our Health and Our World, and A Light History of Hot Air.

What Everyone Needs to Know (WENTK) series offers a balanced and authoritative primer on complex current event issues and countries. Written by leading authorities in their given fields, in a concise question-and-answer format, inquiring minds soon learn essential knowledge to engage with the issues that matter today. Starting July 2014, OUPblog will publish a WENTK blog post monthly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Ebola virus particles by Thomas W. Geisbert, Boston University School of Medicine. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Limiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemic appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIndependence, supervision, and patient safety in residency trainingColostrum, performance, and sports dopingWhat is the Islamic state and its prospects?

Related StoriesIndependence, supervision, and patient safety in residency trainingColostrum, performance, and sports dopingWhat is the Islamic state and its prospects?

A Q&A with John Ferling on the American Revolution

John Ferling is one of the premier historians on the American Revolution. He has written numerous books on the battles, historical figures, and events that led to American independence, most recently with contributions to The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook. Here, he answers questions and discusses some of the lesser-known aspects of the American Revolution.

What was the greatest consequence of the American Revolution?

The greatest consequence of the American Revolution stemmed from Jefferson’s master stroke in the Declaration of Independence. His ringing declaration that “all men are created equal” and all possess the natural right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” has inspired generations hopeful of realizing the meaning of the American Revolution.

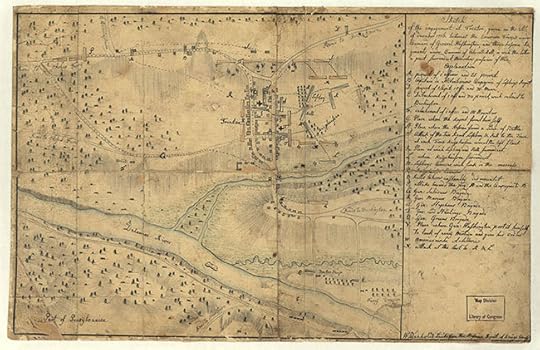

What was the most underrated battle of the Revolutionary War?

King’s Mountain often gets lost in the shuffle, but if Washington’s brilliant Trenton-Princeton campaign was crucially important, King’s Mountain was no less pivotal. Washington’s victory was America’s first in nearly a year, King’s Mountain the first of significance in three years. Trenton-Princeton was vital for recruiting a new army in 1777; King’s Mountain stopped Britain’s recruitment of southern Tories in its tracks. Enemy losses were nearly identical at Trenton-Princeton and King’s Mountain. Finally, Sir Henry Clinton thought the defeat at King’s Mountain was pivotal, and soon thereafter he told one of his generals that with the setback “all his Dreams of Conquest quite vanish’d.”

Sketch of the Battle of Trenton by Andreas Wiederholt (b. 1752?). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

What’s the one unanswered question about the American Revolution you’d most like answered?

The war in the South in 1780 and 1781 is shot through with mysteries. Why did Benjamin Lincoln stay put in Charleston in 1780? He might have withdrawn to the interior, as did those defending against Burgoyne’s invasion, or he might have made a stand behind the Ashley River — as Washington did on the Brandywine — and then retreated to the interior.

Why in the summer that followed did Horatio Gates immediately take the field when his army was so unprepared and he faced no immediate threat? Why did Gates in August at Camden position his men so that the militia faced Cornwallis’s regulars?

Why in 1781 did not Sir Henry Clinton order General Cornwallis back to the Carolinas or summon him and most of his army to New York?

With all the mistakes, maybe the biggest mystery of the war is how anyone won.

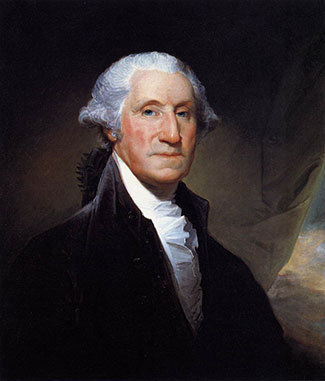

What is your favorite quote by a Revolutionary?

George Washington by Gilbert Stuart. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Aside from the egalitarian and natural rights portions of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, I have two favorite quotations from revolutionaries. One is that of Captain Levi Preston of Danvers, Massachusetts. When asked why he had soldiered on the first day of the war, he responded: “[W]hat we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we always had governed ourselves and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.” My second favorite is Washington’s remark on learning of Lexington and Concord: a “Brother’s Sword has been sheathed in a Brother’s breast.”

Aside from John and Abigail, what was the best husband-wife duo of the Revolution?

If “best” means the duo that best aided the American Revolution, I am sure there must have been countless nameless men who bore arms while their spouses at home made bullets. But of those with whom I am familiar, I opt for Joseph and Esther Reed. He played an important role in Pennsylvania’s insurgency, served in the army and as Washington’s secretary, played a crucial role in the Continental Army’s escape after the Second Battle of Trenton, sat in the Continental Congress, and was the chief executive of his state for three years. She organized the Ladies Organization in Philadelphia in 1780 and published a broadside urging women not to purchase unnecessary consumer items, but instead to donate the money that they saved to aid the soldiery in the Continental army. Altogether, her campaign raised nearly $50,000 in four states.

What was the most important diplomatic action of the war?

The greatest consequence of the American Revolution stemmed from Jefferson’s master stroke in the Declaration of Independence. His ringing declaration that “all men are created equal” and all possess the natural right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” has inspired generations hopeful of realizing the meaning of the American Revolution.

What is your favorite Revolutionary War site (battlefield, home, museum, etc.) to visit today?

If limited to choosing only one site, it would be Mount Vernon. For one thing, George Washington seemed to have a hand in almost everything that occurred in America from 1753 until his death in 1799. In addition, he was a farmer, a pursuit that is alien to most of us today. Mount Vernon includes an informative museum, a functioning distillery and mill, farm land, animals, gardens, and of course the mansion, which opens a window onto the life of a wealthy Virginia planter. Those who lived there as slaves are not overlooked and slavery at Mount Vernon is not whitewashed. Nearly a full day is required to take in everything and at day’s end a visitor who comes without much understanding of the man and his time will leave having received a decent and illuminating introduction to Washington and eighteenth century life and culture.

Mount Vernon by Ad Meskens. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Propaganda was important during the Revolution. What is your favorite propaganda item?

Had there been an Abraham Zapruder armed with a motion picture camera on Lexington Green on 19 April 1775, we might know precisely what occurred when the first shot was fired in the Revolutionary War. But we will never know if that shot was fired accidentally, whether it was fired by British soldiers following orders, or as some alleged if it was fired by a colonist in hiding. What is known is that soon after that historic day the Massachusetts Committee of Safety deposed witnesses of the bloody event, from which it cobbled together an account showing that the regulars opened fire after being commanded to “Fire, by God, Fire.” That account circulated before the official British report was published. In a day when knowledge of who fired the first shot to launch a war was still important, the Massachusetts radicals had scored a propaganda master stroke.

If you could time travel and visit any American city, colony, or state for one year between 1763 and 1783, which would you choose?

I would choose to be living in Boston in 1763. I would like to know what people in the city were thinking about Anglo-America prior to the Sugar and Stamp Acts and how many had ever heard of The Independent Whig. I would like to visit grog shops to discover whether there was a hint of rebellion among the workers and whether they thought Samuel Adams would ever amount to anything. While there, perhaps I could catch a game at Fenway when the St. Louis Browns come to town.

In your opinion, what was George Washington’s biggest blunder of the war?

A book about Washington’s blunders would be large, but his most baffling mistake occurred in September and October 1776. Although fully aware that he was soon to be trapped in Harlem Heights by a superior British army and utterly dominant Royal Navy, Washington made no attempt to escape his snare. His letters at the time indicate an awareness of his dilemma. They also suggest that in addition to his customary indecisiveness, Washington was not just thoroughly exhausted, but in the throes of a black depression. These assorted factors likely explain his potentially fatal torpor. He and the American cause were saved from the looming disaster by the arrival of General Charles Lee, whose advice Washington still respected. Lee took one look and urged Washington to get the army out of the trap. Washington listened, and escaped.

In your opinion, who was the most overrated revolutionary?

Franklin is the most overrated. He was not unimportant – indeed, I think he was a very great man – but as he was abroad for years, he played a minor role in the insurgency between 1765 and 1775. Furthermore, while Franklin was popular in France, Vergennes was a realist who acted in the interest of his country. It is ludicrous to think that Franklin pulled his strings.

Who was the most underrated revolutionary?

General Nathanael Greene is so underrated that many today are unaware of him. But he was the general that Washington turned to for good advice, made personal sacrifices to try to straighten out the quartermaster corps, and waged an absolutely brilliant campaign in the Carolinas between January and March 1781. It was his heroics in the South that helped drive Cornwallis to take his fateful step into Virginia, and to his doom. Had it not been for Greene, it is difficult to envision a pivotal allied victory on the scale of Yorktown in 1781, and without Yorktown the war would have had a different ending, possibly one that did not include American independence.

Was American independence inevitable?

Chatham and Burke knew how independence could be avoided, but it involved surrendering much of Parliament’s power over the colonists. Burke also glimpsed the possibility of using proffered concessions to play on the divisions in the Continental Congress, which included many delegates who opposed a break with Britain. Burke’s notion might have worked. But from the beginning the great majority in Parliament thought that in a worst case scenario the use of force would bring the colonists to heel. Given the political realities of the day, war appears to have been virtually inevitable. Even so, independence very likely would have been prevented had Britain had an adequate number of troops in America in April 1775 or a capable general to lead the campaign for New York in 1776, someone like Earl Cornwallis.

A version of this Q&A first appeared on the Journal of the American Revolution.

John Ferling is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of West Georgia. He is a leading authority on late 18th and early 19th century American history. His latest book, Jefferson and Hamilton: The Rivalry that Forged a Nation, was published in October 2013. He is the author of many books, including Independence, The Ascent of George Washington, Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence, Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution, John Adams: A Life, and A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. He lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A Q&A with John Ferling on the American Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn the 95th anniversary of the Chicago Race RiotsThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914

Related StoriesOn the 95th anniversary of the Chicago Race RiotsThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914

The month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Confusion was still widespread on the morning of 2 August 1914. On Saturday Germany and France had joined Austria-Hungary and Russia in announcing their general mobilization; by 7 p.m. Germany appeared to be at war with Russia. Still, the only shots fired in anger consisted of the bombs that the Austrians continued to shower on Belgrade. Sir Edward Grey continued to hope that the German and French armies might agree on a standstill behind their frontiers while Russia and Austria proceeded to negotiate a settlement over Serbia. No one was certain what the British would do – especially not the British.

Shortly after dawn Sunday German troops crossed the frontier into the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Trains loaded with soldiers crossed the bridge at Wasserbillig and headed to the city of Luxembourg, the capital of the Grand-Duchy. By 8.30 a.m. German troops occupied the railway station in the city centre. Marie-Adélaïde, the grand duchess, protested directly to the kaiser, demanding an explanation and asking him to respect the country’s rights. The chancellor replied that Germany’s military measures should not be regarded as hostile, but only as steps to protect the railways under German management against an attack by the French; he promised full compensation for any damages suffered.

The neutrality of Luxembourg had been guaranteed by the Powers in the Treaty of London of 1867. The prime minister immediately protested the violation at Berlin, Paris, London, and Brussels. When Paul Cambon received the news in London at 7.42 a.m. he requested a meeting with Sir Edward Grey. The French ambassador brought with him a copy of the 1867 treaty – but Grey took the position that the treaty was a ‘collective instrument’, meaning that if Germany chose to violate it, Britain was released from any obligation to uphold it. Disgusted, Cambon declared that the word ‘honour’ might have ‘to be struck out of the British vocabulary’.

The cabinet was scheduled to meet at 10 Downing Street at 11 a.m. Before it convened Lloyd George held a small meeting of his own at the chancellor’s residence next door with five other members of cabinet. They were untroubled by the German invasion of Luxembourg and agreed that, as a group, they would oppose Britain’s entry into the war in Europe. They might reconsider under certain circumstances, however, ‘such as the invasion wholesale of Belgium’.

When they met the cabinet found it almost impossible to decide under what conditions Britain should intervene. Opinions ranged from opposition to intervention under any circumstances to immediate mobilization of the army in anticipation of despatching the British Expeditionary Force to France. Grey revealed his frustration with Germany and Austria-Hungary: they had chosen to play with the most vital interests of civilization and had declined the numerous attempts he had made to find a way out of the crisis. While appearing to negotiate they had continued their march ‘steadily to war’. But the views of the foreign secretary proved unacceptable to the majority of the cabinet. Asquith believed they were on the brink of a split.

After almost three hours of heated debate the cabinet finally agreed to authorize Grey to give the French a qualified assurance. The British government would not permit the Germans to make the English Channel the base for hostile operations against the French.

While the cabinet was meeting in the afternoon a great anti-war demonstration was beginning only a few hundred yards away in Trafalgar Square. Trade unions organized a series of processions, with thousands of workers marching to meet at Nelson’s column from St George’s circus, the East India Docks, Kentish Town, and Westminster Cathedral. Speeches began around 4 p.m. – by which time 10-15,000 had gathered to hear Keir Hardie and other labour leaders, socialists and peace activists. With rain pouring down, at 5 p.m. a resolution in favour of international peace and for solidarity among the workers of the world ‘to use their industrial and political power in order that the nations shall not be involved in the war’ was put to the crowd and deemed to have carried.

Andrew Bonar Law, British leader of the opposition. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

If the British cabinet was divided, so however were the people of London. When the crowd began singing ‘The Red Flag’ and the ‘Internationale’ they were matched by anti-socialists and pro-war demonstrators singing ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Rule Britannia’. When a red flag was hoisted, a Union Jack went up in reply. Part of the crowd broke away and marched a few hundred feet to Admiralty Arch where they listened to patriotic speeches. Several thousand marched up the Mall to Buckingham Palace, singing the national anthem and the Marseillaise. The King and the Queen appeared on the balcony to acknowledge the cheering crowd. Later that evening demonstrators gathered in front of the French embassy to show their support.The anti-war sentiment, which was still strong among labour groups and socialist organizations in Britain, was rapidly dissipating in France. On Sunday morning the Socialist party announced its intention to defend France in the event of war. The newspaper of the syndicalist CGT declared ‘That the name of the old emperor Franz Joseph be cursed’; it denounced the kaiser ‘and the pangermanists’ as responsible for the war. In Germany three large trade unions did a deal with the government: in exchange for promising not to go on strike, the government promised not to ban them. In Russia, organized opposition to war practically disappeared.

Shortly before dinner that evening the British cabinet met once again to decide whether they were prepared to enter the war. The prime minister had received a promise from the leader of the Unionist opposition, Andrew Bonar Law, that his party would support Britain’s entry into the war. Now, if the anti-war sentiment in cabinet led to the resignation of Sir Edward Grey – and most likely of Asquith, Churchill and several others along with him – there loomed the likelihood of a coalition government being formed that would lead Britain into war anyway.

While the British cabinet were meeting in London they were unaware that the German minister at Brussels was presenting an ultimatum to the Belgian government at 7.00 p.m. The note contained in the envelope claimed that the German government had received reliable information that French forces were preparing to march through Belgian territory in order to attack Germany. Germany feared that Belgium would be unable to resist a French invasion. For the sake of Germany’s self-defence it was essential that it anticipate such an attack, which might necessitate German forces entering Belgian territory. Belgium was given until 7 a.m. the next morning – twelve hours – to respond.

Within the hour the prime minister took the German note to the king. They agreed that Belgium could not agree to the demands. The king called his council of ministers to the palace at 9 p.m. where they discussed the situation until midnight. The council agreed unanimously with the position taken by the king and the prime minister. They recessed for an hour, resuming their meeting at 1 a.m. to draft a reply.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 27 July 1914

August 1, 2014

The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

The choice between war and peace hung in the balance on Saturday, 1 August 1914. Austria-Hungary and Russia were proceeding with full mobilization: Austria-Hungary was preparing to mobilize along the Russian frontier in Galicia; Russia was preparing to mobilize along the German frontier in Poland. On Friday evening in Paris the German ambassador had presented the French government with a question: would France remain neutral in the event of a Russo-German war? They were given 18 hours to respond – until 1 p.m. Saturday. In St Petersburg the German ambassador presented the Russian government with another demand: Russia had 12 hours – until noon Saturday – to suspend all war measures against Germany and Austria-Hungary or Germany would mobilize its forces.

But they were also extraordinarily close to peace. Russia and Austria had resumed negotiations in St Petersburg at the behest of Britain, Germany, and France. Austria had declared publicly and repeatedly that it did not intend to seize any Serbian territory and that it would respect the sovereignty and independence of the Serbian monarchy. Russia had declared that it would not object to severe measures against Serbia as long its sovereignty and independence were respected. Surely, when the two of them were agreed on the fundamental principles involved, a settlement was still within reach?

In London the cabinet met at 11 a.m. for 2 1/2 hours. The discussion was devoted exclusively to the crisis. Ministers were badly divided. Winston Churchill was the most bellicose, demanding immediate mobilization. At the other extreme were those who insisted that the government should declare it would not enter the war under any circumstances. According to the prime minister, Asquith, this was ‘the view for the moment of the bulk of the party’. Grey threatened to resign if the cabinet adopted an uncompromising policy of non-intervention.

H. H. Asquith, British Prime Minister 1908-1916. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

One cabinet minister proposed a solution to their dilemma: they should put the onus on Germany. Intervention should depend on whether Germany launched a naval attack on the northern coast of France or violated the independence of Belgium. But his suggestion raised more questions: did Britain have the duty, or merely the right, to intervene if Belgian neutrality were violated? If German troops merely ‘passed through’ Belgium in order to attack France, would this constitute a violation of neutrality? The meeting was inconclusive.

In Berlin the Kaiser was approving the note to be handed to Russia later that day, if it failed to respond positively to the demand that it demobilize: ‘His Majesty the Emperor, my August Sovereign, accepts the challenge in the name of the Empire, and considers himself as being in a state of war with Russia’.

An hour after despatching this telegram another arrived in Berlin from the tsar. Nicholas said he understood that, under the circumstances, Germany was obliged to mobilize, but he asked Wilhelm to give him the same guarantee that he had given Wilhelm: ‘that these measures DO NOT mean war’ and that they would continue to negotiate ‘for the benefit of our countries and universal peace dear to our hearts’.

After meeting with the cabinet, Grey continued to believe that peace might be saved if only a little time could be gained before shooting started. He wired Berlin to suggest that mediation between Austria and Russia could now commence. While promising that Britain abstain from any act that might precipitate matters, he refused to promise that it would remain neutral.

But Grey also refused to promise any assistance to France: Germany appeared willing to agree not to attack France if France remained neutral in a war between Russia and Germany. If France was unable to take advantage of this offer ‘it was because she was bound by an alliance to which we were not parties, and of which we did not know the terms’. Although he would not rule out assisting France under any circumstances, France must make its own decision ‘without reckoning on an assistance that we were not now in a position to give’.

The French ambassador was shocked. He refused to transmit to Paris what Grey had told him, proposing instead to tell his government that the British cabinet had yet to make a decision. He complained that France had left its Atlantic coast undefended because of the naval convention with Britain in 1912 and that the British were honour-bound to assist them. His complaint fell on deaf ears. He staggered from Grey’s office into an adjoining room, close to hysteria, ‘his face white’. Immediately after the meeting he met with two influential Unionists, bitterly declaring ‘Honour! Does England know what honour is’? ‘If you stay out and we survive, we shall not move a finger to save you from being crushed by the Germans later.’

Earlier in Paris General Joffre, chief of the general staff, threatened to resign if the government refused to order mobilization. He warned that France had already fallen two days behind Germany in preparing for war. The cabinet, although divided, agreed to distribute mobilization notices that afternoon at 4 p.m. They agreed, however, to maintain the 10-kilometre buffer zone: ‘No patrol, no reconnaissance, no post, no element whatsoever, must go east of the said line. Whoever crosses it will be liable to court martial and it is only in the event of a full-scale attack that it will be possible to transgress this order’.

By 4 p.m. Russia had yet to reply to the German ultimatum that expired at noon. Falkenhayn, the minister of war, persuaded Bethmann Hollweg to go with him to see the Kaiser and ask him to promulgate the order for mobilization. At 5 p.m., at the Berlin Stadtschloss, the mobilization order sat on a table made from the timbers of Nelson’s Victory. As the Kaiser signed it, Falkenhayn declared ‘God bless Your Majesty and your arms, God protect the beloved Fatherland’.

News of the German declaration of war on Russia spread quickly throughout St Petersburg immediately following the meeting between Pourtalès and Sazonov. Vast crowds began to gather on the Nevsky Prospekt; women threw their jewels into collection bins to support the families of the reservists who had been called up. By 11.30 that night around 50,000 people surrounded the British embassy calling out ‘God save the King’, ‘Rule Britannia’, and ‘Bozhe Tsara Khranie’ [God save the Tsar].

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Sunday, 26 July 1914The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 28 July 1914

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers