Oxford University Press's Blog, page 776

August 10, 2014

Technologies of sexiness

What does it mean for a woman to “feel sexy”? In our current consumer culture, the idea of achieving sexiness is all-pervasive: an expectation of contemporary femininity, wrapped up in objects ranging from underwear, shoes, sex toys, and erotic novels. Particular celebrities and “sex symbol” icons, ranging throughout the decades, are said to embody it: Marilyn Monroe, Brigitte Bardot, Farrah Fawcett, Madonna, Sharon Stone, Pamela Anderson, Kim Kardashian, Miley Cyrus, Megan Fox. Ways of achieving sexiness are suggested by new sex experts, confidence and self-esteem advocates, and make-up aficionados, who tell us how to “Have Better Sex!”, “Seduce Your Man!!”, “Look Sexy, Feel Sexy!!!”

All this expectation to be sexy, and to be constantly working on becoming sexy, has created a high level of cultural anxiety around sexiness — not to mention that this should remain “naturally” sexy, as though no work had gone into it at all (see, for example Jennifer Lopez’s “ordinary” sexy selfie in a bath full of rose petals).

Alongside these pressures, women’s feelings of sexiness now also take place in a period that’s been defined as “post-feminist.” It’s become culturally normative to assume the battles of the feminist period have been won, and that women now have equality with men. This means that, ironically, we are told how to do, think, act and feel sexy, as long as we’re doing it for ourselves. The expectation to feel sexy becomes as contradictory as a “Question Authority” bumper sticker.

How do women make sense of sexiness as part of feeling like a woman in the 21st Century? More importantly, one has to understand how generation figures into the equation, in terms of the “discursive repertories” that different age groups would have at their disposal in the context of “post-feminism.” How do women at different life stages negotiate the pressures to be sexy? Is sexiness achievable, or is the expectation too much? Do all women have an equal right to feel sexy? Who is missing from contemporary understandings of sexiness? How does the culture of sexiness interact with how women feel about themselves?

During the research stage of our book, we spoke to two groups of white, heterosexual women, whom we called the “Pleasure Pursuers” (aged 25-35) and the “Functioning Feminists” (aged 45-55). Our discussions with these women were filled with stories of pleasure, pain, anxiety, fun, concern, disgust, and support. However, what was interesting was how both groups made sense of sexiness as a way of defining themselves as ‘good’ people: either as “good” new sexual subjects (fun and pleasure-seeking) or as “good” feminists (critical and nostalgic). Both allowed women to understand themselves in affirmative, authoritative ways. But the actual experience to feel sexy was something to work towards, or something that had already passed. Neither groups talked about feeling sexy in the here and now.

What it means to feel sexy now, today, is political. It folds together spheres of governmental policy, consumer culture, identity, and new digitally-driven feminist activism. The idea of a powerful and self-defined sexually confident woman has a strong pull for feminist researchers, as do calls to respect women’s “voice” and agency. However a consumer culture that sells confidence, choice and self-determination to women is way more difficult to defend. What we did find, though, through our discussions with women, was that their positions were slippery, contested full of contradiction, and never fully formed. For us, this spoke volumes about how to make sense of sexiness today, as a political construct, and as feminist academics and researchers.

Whether we’re pursuing the post-feminist promise of the sassy, sexy, self-determined, self-knowing feminine identity, or critically reacting against it, wishing it was replaced with more “authentic” feminist notions of sexiness, the cultural impulse to be sexy is side stepped. In a similar argument, Nina Power, author of One Dimensional Woman, warned us not to “be misled: The imperative to “Enjoy!” is omnipresent, but pleasure and happiness are almost entirely absent.” What it means for women to feel sexy today is what’s missing — and it’s these missing places, gaps, and contradictions, that deserve more critical inquiry and inter-generational dialogue.

Adrienne Evans is a Senior Lecturer in Media at Coventry University. Her main research interest is in exploring women’s contemporary sexual identities. Her current work continues in contemporary gender relations and the use of creative methods in research and teaching. She has published this work in the European Journal of Women’s Studies, Journal of Gender Studies, Men and Masculinities, Teaching in Higher Education, and Feminism and Psychology. She is co-author of Technologies of Sexiness: Sex, Identity, and Consumer Culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Postmodern Sleeping Beauty by Helga Weber. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Technologies of sexiness appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesYouth and the new media: what next?My client’s online presenceSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Related StoriesYouth and the new media: what next?My client’s online presenceSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Nicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistry

The past couple of years have seen the celebration of a number of key developments in the history of physics. In 1913 Niels Bohr, perhaps the second most famous physicist of the 20th century after Einstein, published is iconic theory of the atom. Its main ingredient, which has propelled it into the scientific hall of fame, was it’s incorporation of the notion of the quantum of energy. The now commonplace view that electrons are in shells around the nucleus is a direct outcome of the quantization of their energy.

Between 1913 and 1914 the little known English physicist, Henry Moseley, discovered that the use of increasing atomic weights was not the best way to order the elements in the chemist’s periodic table. Instead, Moseley proposed using a whole number sequence to denote a property that he called the atomic number of an element. This change had the effect of removing the few remaining anomalies in the way that the elements are arranged in this icon of science that is found on the walls of lecture halls and laboratories all over the world. In recent years the periodic table has even become a cultural icon to be appropriated by artists, designers and advertisers of every persuasion.

But another scientist who was publishing articles at about the same time as Bohr and Moseley has been almost completely forgotten by all but a few historians of physics. He is the English mathematical physicist John Nicholson, who was in fact the first to suggest that the momentum of electrons in an atom is quantized. Bohr openly acknowledges this point in all his early papers.

Nicholson hypothesized the existence of what he called proto-elements that he believed existed in inter-stellar space and which gave rise to our familiar terrestrial chemical elements. He gave them exotic names like nebulium and coronium and using this idea he was able to explain many unassigned lines in the spectra of the solar corona and the major stellar nebulas such as the famous Crab nebula in the constellation of Orion. He also succeeded in predicting some hitherto unknown lines in each of these astronomical bodies.

The really odd thing is that Nicholson was completely wrong, or at least that’s how his ideas are usually regarded. How it is that supposedly ‘wrong’ theories can produce such advances in science, even if only temporarily?

Image Credit: Bio Lab. Photo by Amy. CC BY 2.0 via Amy Loves Yah Flickr.

Science progresses as a unified whole, not stopping to care about which scientist is successful or not, while being only concerned with overall progress. The attribution of priority and scientific awards, from a global perspective, is a kind of charade which is intended to reward scientists for competing with each other. On this view no scientific development can be regarded as being right or wrong. I like to draw an analogy with the evolution of species or organisms. Developments that occur in living organisms can never be said to be right or wrong. Those that are advantageous to the species are perpetuated while those that are not simply die away. So it is with scientific developments. Nicholson’s belief in proto-elements may not have been productive but his notion of quantization in atoms was tremendously useful and the baton was passed on to Bohr and all the quantum physicists who came later.

Instead of viewing the development of science through the actions of individuals and scientific heroes, a more holistic view is better to discern the whole process — including the work of lesser-known intermediate figures, such as Nicholson. The Dutch economist Anton den Broek first made the proposal that elements should be characterized by an ordinal number before Moseley had even begun doing physics. This is not a disputed point since Moseley begins one of his key papers by stating that he began his research in order to verify the van den Broek hypothesis on atomic number.

Another intermediate figure in the history of physics was Edmund Stoner who took a decisive step forward in assigning quantum numbers to each of the electrons in an atom while as a graduate student at Cambridge. In all there are four such quantum numbers which are used to specify precisely how the electrons are arranged first in shells, then sub-shells and finally orbitals in any atom. Stoner was responsible for applying the third quantum number. It was after reading Stoner’s article that the much more famous Wolfgang Pauli was able to suggest a fourth quantum number which later acquired the name of electron spin to describe a further degree of freedom for every electron in an atom.

Eric Scerri is a full-time chemistry lecturer at UCLA. Eric Scerri is a leading philosopher of science specializing in the history and philosophy of the periodic table. He is also the founder and editor in chief of the international journal Foundations of Chemistry and has been a full-time lecturer at UCLA for the past fifteen years where he regularly teaches classes of 350 chemistry students as well as classes in history and philosophy of science. He is the author of A Tale of Seven Elements, The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance, and The Periodic Table: A Very Short Introduction.

Chemistry Giveaway! In time for the 2014 American Chemical Society fall meeting and in honor of the publication of The Oxford Handbook of Food Fermentations, edited by Charles W. Bamforth and Robert E. Ward, Oxford University Press is running a paired giveaway with this new handbook and Charles Bamforth’s other must-read book, the third edition of Beer. The sweepstakes ends on Thursday, August 14th at 5:30 p.m. EST.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Nicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistry appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe health benefits of cheeseExtending patent protections to discover the next life-saving drugsYouth and the new media: what next?

Related StoriesThe health benefits of cheeseExtending patent protections to discover the next life-saving drugsYouth and the new media: what next?

The health benefits of cheese

Lipids (fats and oils) have historically been thought to elevate weight and blood cholesterol and have therefore been considered to have a negative influence on the body. Foods such as full-fat milk and cheese have been avoided by many consumers for this reason. This attitude has been changing in recent years. Some authors are now claiming that consumption of unnecessary carbohydrates rather than fat is responsible for the epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Most people who do consume milk, cheese, and yogurt know that the calcium helps with bones and teeth, but studies have shown that consumption of cheese and other dairy products appears to be beneficial in many other ways. Remember that cheese is a concentrated form of milk. Milk is 87% water and when it is processed into cheese, the nutrients are increased by a factor of ten. The positive attributes of milk are even stronger in cheese. Here are some examples involving protein:

Some bioactive peptides in casein (the primary protein in cheese) inhibit angiotensin-converting enzyme, which has been implicated in hypertension. Large studies have shown that dairy intake reduces blood pressure.

Cheese helps prevent tooth decay through a combination of bacterial inhibition and remineralization. Further, Lactoferrin, a minor milk protein found in cheese, has anticancer properties. It appears to keep cancer cells from proliferating.

Vitamins and minerals in cheese may not get enough credit. A meta-analysis of 16 studies showed that consumption of 200 g of cheese and other dairy products per day resulted in a 6% reduction of risk of T2DM, with a significant association between reduction of incidence of T2DM and intake of cheese, yogurt, and low-fat dairy products. Much of this may be due to vitamin K2, which is produced by bacteria in fermented dairy products.

Metabolic syndrome increases the risk for T2DM and heart disease, but research showed that the incidence of this syndrome decreased as dairy food consumption increased, a result that was associated with calcium intake.

There is evidence that lipids in cheese are not unhealthy after all. Recent research has shown no connection between the intake of milk fat and the risk of cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, or stroke. A meta-analysis of 76 studies concluded that the evidence does not clearly support guidelines that encourage high consumption of polyunsaturated fatty acids and low consumption of total saturated fats.

Participants in a study who ate cheese and other dairy products at least once per day scored significantly higher in several tests of cognitive function compared with those who rarely or never consumed dairy food. These results appear to be due to a combination of factors.

Seemingly, the opposite of what people believe about cheese turns out to be the truth. Studies involving thousands of people over a period of years revealed that a high intake of dairy fat was associated with a lower risk of developing central obesity and a low dairy fat intake was associated with a higher risk of central obesity. Higher consumption of cheese has been associated with higher HDL (“good cholesterol”) and lower LDL (“bad cholesterol”), total cholesterol, and triglycerides.

All-cause mortality showed a reduction associated with dairy food intake in a meta-analysis of five studies in England and Wales covering 509,000 deaths in 2008. The authors concluded that there was a large mismatch between evidence from long-term studies and perceptions of harm from dairy foods.

Yes, some people are allergic to protein in cheese and others are vegetarians who don’t touch dairy products on principle. Many people can’t digest lactose (milk sugar) very well, but aged cheese contains little of it and lactose-free cheese has been on the market for years. But cheese is quite healthy for most consumers. Moderation in food consumption is always the key: as long as you eat cheese in reasonable amounts, you ought to have no ill effects while reaping the benefits.

Michael Tunick is a research chemist with the Dairy and Functional Foods Research Unit of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service. He is the author of The Science of Cheese. You can find out more things you never knew about cheese.

Chemistry Book Giveaway! In time for the 2014 American Chemical Society fall meeting and in honor of the publication of The Oxford Handbook of Food Fermentations, edited by Charles W. Bamforth and Robert E. Ward, Oxford University Press is running a paired giveaway with this new handbook and Charles Bamforth’s other must-read book, the third edition of Beer. The sweepstakes ends on Thursday, August 14th at 5:30 p.m. EST.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Hand milking a cow, by the State Library of Australia. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The health benefits of cheese appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesExtending patent protections to discover the next life-saving drugs18 facts you never knew about cheeseYouth and the new media: what next?

Related StoriesExtending patent protections to discover the next life-saving drugs18 facts you never knew about cheeseYouth and the new media: what next?

The Fair Toxophilities and Daniel Deronda

By K. M. Newton

The painting The Fair Toxophilites: English Archers by W. P. Frith, dating from 1872, is one of a series representing contemporary life in England. Frith wrote that his”

“desire to discover materials for my work in modern life never leaves me … and, though I have occasionally been betrayed by my love into themes somewhat trifling and commonplace, the conviction that possessed me that I was speaking – or rather painting – the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, rendered the production of real-life pictures an unmixed delight. In obedience to this impulse I began work on a small work suggested by some lady-archers, whose feats had amused me at the seaside … The subject was trifling, and totally devoid of character interest; but the girls are true to nature, and the dresses will be a record of the female habiliments of the time.”

After Gwendolen Harleth’s encounter with Daniel Deronda in Leubronn in Chapters 1 and 2, there’s a flashback to Gwendolen’s life in the year leading up to that meeting, with Chapters 9 to 11 focusing on the Archery Meeting, where she first meets Henleigh Grandcourt, and its consequences. In the England of the past archery was the basis of military and political power, most famously enabling the English to defeat the French at Agincourt. In the later nineteenth century it is now a leisure pursuit for upper-class women. This may be seen as symptomatic of the decline or even decadence of the upper class since it is now associated with an activity which Frith suggests is “trifling and commonplace.” A related symptom of that decline is the devotion of aristocratic and upper-class men, such as Grandcourt and Sir Hugo Mallinger, to a life centred on hunting and shooting.

The Frith painting shows a young female archer wearing a fashionable and no doubt extremely expensive dress and matching hat. This fits well with the novel for Gwendolen takes great care in her choice of a dress that will enhance her striking figure and make her stand out at the Archery Meeting, since “every one present must gaze at her” (p. 89), especially Grandcourt. The reader may similarly be inclined to gaze at the figure in the painting. One might say that together with her bow and arrow Gwendolen dresses to kill, an appropriate expression for arrows can kill though in her case she wishes only to kill Grandcourt metaphorically: “My arrow will pierce him before he has time for thought” (p. 78). Readers of the novel will discover that light-hearted thoughts about killing Grandcourt will take a more serious turn later.

With the coming of Grandcourt into the Wancester neighbourhood through renting Diplow Hall, the thoughts of young women and especially their mothers turn to thoughts of marriage – there is obvious literary allusion to the plot of Pride and Prejudice in which Mr Bingley’s renting of Netherfield Park creates a similar effect. The Archery Meeting is the counterpart to the ball in Pride and Prejudice since it is an opportunity for women to display themselves to the male gaze in order to attract eligible husbands and no man is more eligible than Grandcourt. Whereas Mr Darcy eventually turns out to be the perfect gentleman, in Eliot’s darker vision Grandcourt has degenerated into a sadist, “a remnant of a human being” (p. 340), as Deronda calls him. Though Gwendolen is contemptuous of the Archery Meeting as marriage-market, she cannot help being drawn into it as she believes at this point that ultimately a woman of her class, background, and upbringing has no viable alternative to marriage.

While Grandcourt’s moving into Diplow Hall together with his likely attendance of the Archery Meeting become the central talking points of the neighbourhood among Gwendolen and her circle, the narrator casually mentions another matter that is being ignored – “the results of the American war” (p. 74). Victory for the North in the Civil War established the United States as a single nation, one which would ultimately become a great power. There is a similar passing reference later to the Prussian victory over the Austrians at “the world-changing battle of Sadowa” (p. 523), a major step towards the emergence of a unified German nation. While the English upper class are living trivial lives the world is changing around them and Britain’s time as the dominant world power may be ending.

Though the eponymous Deronda does not feature in this part of the novel, he is in implicit contrast to Gwendolen and the upper-class characters as he is preoccupied with these larger issues and uninvolved in trivial activities like archery or hunting and finally commits himself to the ideal of creating a political identity for the Jews. When he tells Gwendolen near the end of the novel of his plans, she is at first uncomprehending but is forced to confront the existence and significance of great events that she previously had ignored through being preoccupied with such “trifling” matters as making an impression at the Archery Meeting: “… she felt herself reduced to a mere speck. There comes a terrible moment to many souls when the great movements of the world, the larger destinies of mankind … enter like an earthquake into their own lives — when the slow urgency of growing generations turns into the tread of an invading army or the dire clash of civil war” (p. 677). She will no longer be oblivious of something like “the American war.” By the end of the novel the reader looking at the painting on the front cover may realize that though this woman who resembles Gwendolen remains trapped in triviality and superficiality, the character created in the mind of the reader by the words of the novel has moved on from that image and undergone a fundamental alteration in consciousness.

K. M. Newton is Professor Emeritus at the University of Dundee. He is the editor, with Graham Handley, of the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of Daniel Deronda by George Eliot.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Fair Toxophilites by W. P. Frith. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The Fair Toxophilities and Daniel Deronda appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 questions for Ammon SheaFive questions for Rebecca MeadGaming the system

Related Stories10 questions for Ammon SheaFive questions for Rebecca MeadGaming the system

August 9, 2014

My client’s online presence

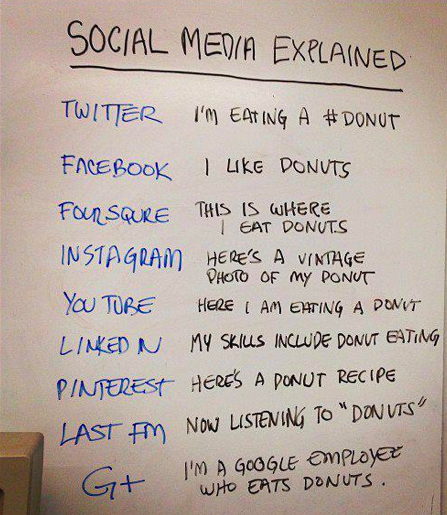

Social media and other technologies have changed how we communicate. Consider how we coordinate events and contact our friends and family members today, versus how we did it 20 or 30 years ago. Today, we often text, email, or communicate through social media more frequently than we phone or get together in person.

Now contrast that with psychotherapy, which is still about two people getting together in a room and talking. Certainly, technology has changed psychotherapy. There are now apps for mental health issues. There are virtual reality treatments. Psychotherapy can now be provided through videoconferencing (a.k.a. telehealth). But still, it’s usually simply two people talking in a room.

Our psychotherapy clients communicate with everyone else they know through multiple technological platforms. Should we let them “friend” us on social media? Should we link to them on professional networking sites? Is it ok to text with them? What about email? When are these ok and not ok?

Social Media Explained (with Donuts). Uploaded by Chris Lott. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Some consensus is emerging about these issues. Experts agree that psychotherapists should not connect with current or former clients on social media. This is to help preserve the clients’ confidentiality. Emailing and texting are fine for communicating brief messages about the parameters of the session, such as confirming the appointment time, or informing the psychotherapist that the client is running late. Research has shown that emotional tone is frequently miscommunicated in texting and email, so emotion-laden topics are best discussed during the session.

How do we learn about new people we’ve met? In the past, we’d talk directly to them, and maybe also talk to people we knew in common. Now everyone seems to search online for everyone else. This happens frequently with first dates, college applicants, and job applicants.

Again, contrast this with psychotherapy. Again, two people are sitting in a room, talking and learning about each other. When is it ok for a psychotherapist to search for information about a client online? What if the psychotherapist discovers important information that the client withheld? How do these discoveries impact the psychotherapy?

No clear consensus has emerged on these issues. Some experts assert that psychotherapists should almost never search online for clients. Other experts respond that it is unreasonable to expect that psychotherapists should not access publicly available information. Others suggest examining each situation on a case-by-case basis. One thing is clear: psychotherapists should communicate with their clients about their policies on internet searches. This should be done in the beginning of psychotherapy, as part of the informed consent process.

When we’ve voluntarily posted information online–and when information about us is readily available in news stories, court documents, or other public sources–we don’t expect this information to be private. For this reason, I find the assertion that psychotherapists can access publically available information to be more compelling. On my intake forms, I invite clients to send me a link to their LinkedIn profile instead of describing their work history, if they prefer. If a client mentions posting her artwork online, I’ll suggest that she send me a link to it or ask her how to find it. I find that clients are pleased that I take an interest.

What about the psychotherapist’s privacy? What if the client follows the psychotherapist’s Twitter account or blog? What if the client searches online for the psychotherapist? What if the client discovers personal information about the psychotherapist by searching? Here’s the short answer: psychotherapists need to avoid posting anything online that we don’t want everyone, including our clients, to see.

Ways to communicate online continue to proliferate. For example, an app that sends only the word “Yo” was recently capitalized to the tune of $2.5 million and was downloaded over 2 million times. Our professional ethics codes are revised infrequently (think years), while new apps and social media are emerging monthly, even daily. Expert consensus on how to manage these new communications technologies emerges slowly (again, think years). But psychotherapists have to respond to new communications technologies in the moment, every day. All we can do is keep the client’s well-being and confidentiality as our highest aspiration.

Jan Willer is a clinical psychologist in private practice. For many years, she trained psychology interns at the VA. She is the author of The Beginning Psychotherapist’s Companion, which offers practical suggestions and multicultural clinical examples to illustrate the foundations of ethical psychotherapy practice. She is interested in continuing to bridge the notorious research-practice gap in clinical psychology. Her seminars have been featured at Northwestern University, the University of Chicago, and DePaul University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post My client’s online presence appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesYouth and the new media: what next?Rebooting PhilosophySupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Related StoriesYouth and the new media: what next?Rebooting PhilosophySupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Quebec French and the question of identity

A brief history of the French language in Quebec

The French language came to North America with the first French settlers in the 17th century. French and British forces had long been at war before the final victory of Britain in the mid 18th century; after the loss of New France, France lost contact with its settlers and Quebec French became isolated from European French. The two languages evolved in different ways, leaving Quebec French with older forms of pronunciation and expressions that later died out in France. Until the emergence of radio and television broadcasting, French Canadian society had been completely dominated by English, which was the language of the ruling class.

During the 1960s, Quebec went through a period of intense change called the Révolution tranquille (Quiet Revolution). This period marked the transition from political conservatism and sociocultural immobility, mainly orchestrated by the Roman Catholic Church, to a modern era characterized by major social development and an increase of Quebecois control over the province’s economy. The Quiet Revolution was also characterized by the affirmation of the Quebecois identity, closely related to their linguistic affirmation.

The French language spoken in Quebec was no longer a simple linguistic matter, but became an ideological, political, academic, and economic issue — the symbol of a society willing to get rid of its alienated minority status. The modernization of Quebec society had repercussions on the language itself, which was seen by the francophone elite as underdeveloped and corrupted by its contact with English. Laws were voted to promote French as the only official language of the province of Quebec, and plans to replace pervasive English terminology were supported by the Office Québécois de la Langue Française. At the same time, an eager desire to standardize and to improve Quebec French in line with the Metropolitan French norm was observed. This drew criticism from a lot of Quebecois, who claimed that their language was an integral part of their identity. Today, even if the status of Quebec French still remains slightly ambiguous, the Quebecois have mainly lost their feeling of inferiority toward Metropolitan French. The media now uses what is called ‘standard Quebec French’, and people are proud of its deviations from European French.

Quebec French and Metropolitan French

There are several types of differences between Metropolitan French (MF) and Quebec French (QF). Besides phonetic differences that will not be addressed here, the more obvious ones are lexical. Here is an overview of what they look like.

There are plenty of words in QF that are falling out of use or sound old-fashioned in MF: for example, soulier (shoe) rather than chaussure in MF, bas (socks) instead of chaussette in MF. We can also observe some small discrepancies that can cause confusion, since word meanings are not always completely equivalent. For example, “birthday” is anniversaire in MF but more commonly fête in QF, while fête in MF (meaning “party”) is party in QF (pronounced as [paʀte]). Thus, the expression fête d’anniversaire (“birthday party”) is usually party de fête in QF. In QF foulard is the equivalent of both écharpe (scarf) and foulard (light scarf) in MF. Where MF requires a precise word for each relationship, the informal word chum in QF can encompass husband, common-law husband, and boyfriend.

But differences between these two forms of French go beyond the lexical level. Although some Quebecois tend to deny it, there are also some syntactic differences. One can observe the use of prepositions in QF where MF would not allow them. For instance, in QF il vient à tous les soirs (he comes every night) is il vient tous les soirs in MF. Twenty years ago, the verb aider (to help) was still a transitive verb with an indirect object: aider à quelqu’un instead of aider quelqu’un.

While the use of the interrogative pronoun in a declarative sentence such as je ne sais pas qu’est ce qu‘il faut faire is seen as an uneducated mistake in MF (where people say je ne sais pas ce qu’il faut faire), this form is commonly used in QF.

Finally, more surprisingly, morphological differences can be noticed between the two languages. While trampoline is a feminine noun in QF, it is a masculine one in MF. On the contrary, moustiquaire (mosquito net) is a feminine noun in MF and a masculine one in QF. Cash machine is translated as distributeur de billets in MF and distributrice de billets in QF. Some recent linguistic borrowings have different genders too: feta and mozzarella are feminine nouns in MF but masculine ones in QF; job is a masculine noun in MF and a feminine one in QF, and so forth. One can also observe some nouns with a floating gender in QF, for instance, sandwich is either feminine or masculine.

Quebec French and English

About two thirds of Montreal’s population are francophones, most of whom are bilingual. However, in Quebec City and rural Quebec, even the youngest aren’t necessarily fluent in English. Some people do not have any knowledge of English whatsoever. Yet, since the province of Quebec is surrounded by English-speaking regions (i.e. the rest of Canada and the United States), even if people fiercely fight it, QF is inevitably and strongly influenced by the English language. Some Anglicisms are so commonly used that they have become assimilated into the particularities of QF: for example, tomber en amour literally means “to fall in love,” and prendre une marche is literally “to take a walk.” There are a lot of mispronounced English words that have been introduced to QF, such as gagne from gang, bécosse (toilet) from back house, bobépine from bobby pin, paparmanne from peppermint, and pinotte from peanut.

One can observe some Anglicisms that are not the same as those in MF. We find in QF être conservateur (to be conservative), faire le party (to party), and avoir une date avec quelqu’un (to have a date with someone), where in MF one would say être prudent, faire la fête, and avoir un rendez-vous (galant). Instead of week-end, parking, and email commonly used in MF, QF uses fin de semaine, stationnement, and courriel respectively.

Even if the Office Québécois de la Langue Française has done a very good job of promoting French terminology in many technical areas, some of them are still dominated by English. For instance, a lot of Quebecois, even the non-English speakers, do not know the French equivalent for “windshield,” “muffler,” or “clutch.”

In asserting itself, Quebec French faces two issues: it stands between the ongoing invasion of English and the will to fight against it, and also between a desire to conform itself to Metropolitan French and to claim proudly its own particularities. Over the years, Quebec French has moved from a very popular English-mixed dialect to a valuable distinct and recognized French language. The Quebecois like to consider it as a true language and are eager to protect it, since it guarantees the liveliness of their particular culture in an English-speaking North America.

This article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Anne-Laure Jousse works as a lexicographer for Druide Informatique Inc. (Antidote) in Montreal after having studied French linguistics at both Paris VII and University of Montreal.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Quebec City, Canada via Shutterstock.

The post Quebec French and the question of identity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe first rule of football is… don’t call it soccerHow I created the languages of Dothraki and Valyrian for Game of ThronesKotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of language

Related StoriesThe first rule of football is… don’t call it soccerHow I created the languages of Dothraki and Valyrian for Game of ThronesKotodama: the multi-faced Japanese myth of the spirit of language

Improving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna Atkeson

I recently had the opportunity to talk with Lonna Atkeson, Professor of Political Science and Regents’ Lecturer at the University of New Mexico. We discussed her opinions about improving survey methodology and her thoughts about how surveys are being used to study important applied questions. Lonna has written extensively about survey methodology, and has developed innovative ways to use surveys to improve election administration (her 2012 study of election administration is a wonderful example).

In the current issue of Political Analysis is the Symposium on Advances in Survey Methodology, which Lonna and I co-edited; in addition to the five research articles in the Symposium, we wrote an introduction that puts each of the research articles in context and talks about the current state of research in survey methodology. Also, Lonna and I are co-editing the Oxford Handbook on Polling and Polling Methods, which is in initial stages of development.

It’s well-known that response rates for traditional telephone surveying have declined dramatically. What’s the solution? ow can survey researchers produce quality data given low response rates with traditional telephone survey approaches?

What we’ve learned about response rates is they are not the be all or end all as an evaluative tool for the quality of the survey, which is a good thing because response rates are ubiquitously low! There is mounting evidence that response rates per se are not necessarily reflective of problems in nonresponse. Nonresponse error appears to be more related to the response rate interacting with the characteristic of the nonrespondent. Thus, if survey topic salience leads to response bias then nonresponse error becomes a problem, but in and of itself response rate is only indirect evidence of a potential problem. One potential solution to falling response rates is to use mixed mode surveys and find the best contact and response option for the respondent. As polling becomes more and more sophisticated, we need to consider best contact and response methods for different types of sample members. Survey researchers need to be able to predict the most likely response option for the individual and pursue that strategy.

Close up of a man smiling on the line through a headset. © cenix via iStockphoto.

Much of your recent work uses “mixed-mode” survey methods. What’s a “mixed-mode” survey? What are the strengths and weaknesses of this approach?

Mixed mode surveys use multiple methods to contact or receive information from respondents. Thus, mixed mode surveys involve both mixtures of data collection and communications with the respondent. For example, a mixed mode survey might contact sample members by phone or mail and then have them respond to a questionnaire over the Internet. Alternatively a mixed mode survey might allow for multiple forms of response. For example, sample frame members may be able to complete the interview over the phone, by mail, or on the web. Thus a respondent who does not respond over the Internet may in subsequent contact receive a phone call or a FTF visit or may be offered a choice of response mode on the initial contact.

When you see a poll or survey reported online or in the news media, how do you determine if the poll was conducted in a way that has produced reliable data? What indicates a high-quality poll?

This is a difficult question because all polls are not created equally and many reported polls might have problems with sampling, nonresponse bias, question wording, etc. The point being that there are many places where error creeps into your survey not just one and to evaluate a poll researchers like to think in terms of total survey error, but the tools for that evaluation are still in the development stage and is an area of opportunity for survey researchers and political methodologists. We also need to consider a total survey error approach in how survey context, which now varies tremendously, influences respondents and what that means for our models and inferences. This is an area for continued research. Nevertheless, the first criteria for examining a poll ought to be its transparency. Polling data should include information on who funded the poll, a copy of the instrument, a description of the sampling frame, and sampling design (e.g. probability, non-probability, the study size, estimates of sampling error for probability designs, information on any weighting of the data, and how and when the data were collected). These are basic criteria that are necessary to evaluate the quality of the poll.

Clearly, as our symposium on survey methodology in the current issue of Political Analysis discusses, survey methodology is at an important juncture. What’s the future of public opinion polling?

Survey research is a rapidly changing environment with new methods for respondent contacting and responding. Perhaps the biggest change in the most recent decade is the move away from predominantly interviewer driven data collection methods (e.g. phone, FTF) to respondent driven data collection methods (e.g. mail, Internet, CASI), the greater use of mixed mode surveys, and the introduction of professional respondents who participate over long periods of time in discontinuous panels. We are just beginning to figure out how all these pieces fit together and we need to come up with better tools to assess the quality of data we are obtaining. The future of polling and its importance in the discipline, in marketing, and in campaigns will continue, and as academics we need to be at the forefront of evaluating these changes and their impact on our data. We tend to brush over the quality of data in favor of massaging the data statistically or ignoring issues of quality and measurement altogether. I’m hoping the changing survey environment will bring more political scientists into an important interdisciplinary debate about public opinion as a methodology as opposed to the study of the frequencies of opinions. To this end, I have a new Oxford Handbook, along with my co-editor Mike Alvarez, on polling and polling methods that will take a closer look at many of these issues and be a helpful guide for current and future projects.

In your recent research on election administration, you use polling techniques as tools to evaluate elections. What have you learned from these studies, and based on your research what do you see are issues that we might want to pay close attention to in this fall’s midterm elections in the United States?

We’ve learned so much from our election administration work about designing polling places, training poll workers, mixed mode surveys and more generally evaluating the election process. In New Mexico, for example, we have been interviewing both poll workers and voters since 2006, giving us five election cycles, including 2014, that provide an overall picture of the current state of election administration and how it’s doing relative to past election cycles. Our multi-method approach provides continuous evaluation, review, and improvement to New Mexico elections. This fall I think there are many interesting questions. We are interested in some election reform questions about purging voter registration files, open primaries, the straight party ballot options and felon re-enfranchisement. We are also especially interested in how voters decide whether to vote early or on Election Day and on Election Day where they decide to vote if they are using voting convenience centers instead of precincts. This is an important policy question, but where we place vote centers might impact turnout or voter satisfaction or confidence. We are also very interested in election lines and their impact on voters. In 2012 we found that voters on average can fairly easily tolerate lines of about ½ an hour, but feel there are administrative problems when lines grow longer. We want to continue to drill down on this question and examine when lines deter voters or create poor experiences that reduce the quality of their vote experience.

Lonna Rae Atkeson is Professor of Political Science and Regents’ Lecturer at the University of New Mexico. She is a nationally recognized expert in the area of campaigns, elections, election administration, survey methodology, public opinion and political behavior and has written numerous articles, book chapters, monographs and technical reports on these topics. Her work has been supported by the National Science Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trusts, the JEHT Foundation, the Galisano Foundation, the Bernalillo County Clerk, and the New Mexico Secretary of State. She holds a BA in political science from the University of California, Riverside and a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Colorado, Boulder.

R. Michael Alvarez is a professor of Political Science at Caltech. His research and teaching focuses on elections, voting behavior, and election technologies. He is editor-in-chief of Political Analysis with Jonathan N. Katz.

Political Analysis chronicles the exciting developments in the field of political methodology, with contributions to empirical and methodological scholarship outside the diffuse borders of political science. It is published on behalf of The Society for Political Methodology and the Political Methodology Section of the American Political Science Association. Political Analysis is ranked #5 out of 157 journals in Political Science by 5-year impact factor, according to the 2012 ISI Journal Citation Reports. Like Political Analysis on Facebook and follow @PolAnalysis on Twitter.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and political science articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Improving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna Atkeson appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOral history, historical memory, and social change in West Mount AiryHate crime and community dynamicsSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Related StoriesOral history, historical memory, and social change in West Mount AiryHate crime and community dynamicsSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Extending patent protections to discover the next life-saving drugs

At the end of last year, Eli Lilly’s mega-blockbuster antidepressant Cymbalta went off patent. Cymbalta’s generic version, known as duloxetine, rushed in to the market and drove down the price, making it more affordable.

Great news for everyone, right? Well, not quite.

Indeed, generic competition is a great boon to the payer and the patient. On the other hand, the makers of the brand medicine can lose about 70% of the revenue. Without sustained investment in drug discovery and development, there will be fewer and fewer lifesaving drugs, not really a scenario the patient wants. Cymbalta had sales of $6.3 billion last year. Combined with Zyprexa, which lost patent protection in 2011, Lilly lost $10 billion in annual sales from these two drugs alone. The company responded by freezing salaries and slashing 30% of its sales force.

Prescription Prices. Photo by Chris Potter, StockMonkeys.com. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Lilly is not alone in this quandary. In 2011, Pfizer lost its $13 billion drug Lipitor, the best-selling drug ever, which made “merely” $2.3 billion in 2013. Of course Pfizer became the number one drug company by swallowing Warner-Lambert, Pharmacia, and Wyeth, shutting down many research sites that were synonyms to the American pharmaceutical industry, and shedding tens of thousands of jobs. Meanwhile, Merck lost its US marketing exclusivity of its asthma drug Singulair (montekulast) in 2012 and saw a 97% decline in US sales in 4Q12 compared with 4Q11. Merck announced in October last year that it would cut 8,500 jobs on top of the 7,500 layoffs planned earlier. Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Plavix (clopidogrel)’s peak sales were $7 billion, ranking the second best-selling drug ever. After Plavix lost its patent protection in May 2012, the sales were $258 million last year. Meanwhile BMS has shrunk from 43,000 to 28,000 employees in the last decade.

Generics competition is not the only woe that big Pharma are facing. Outsourcing Pharma jobs to China and India, M&A, and economic downturn rendered thousands of highly paid and highly educated scientists to scramble for alternative employments, many outside the drug industry. With numerous site closures, outsourcing cost reductions, and downsizing, some 150,000 in Pharma lost their jobs from 2009 through 2012, according to consulting firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas. Such a brain drain makes us the lost generation of American drug discovery scientists, including this author. In contrast, Japanese drug companies refused to improve the bottom line through mass layoffs of R&D staff, a decision will likely benefit productivity in the long run.

What can we do to ensure the health of the drug industry and sustain the output of lifesaving medicines? Realizing that there is no single prescription for this issue, one could certainly begin talking about patent reform.

Current patent system is antiquated as far as innovative drugs are concerned. Decades ago, 17 years of patent life was somewhat adequate for the drug companies to recoup their investment in R&D because the life cycle from discovery to marketing at the time was relatively short and the cost was lower. Today’s drug discovery and development is a completely new ballgame. First of all, the low-hanging fruits have been harvested, and it is becoming increasingly challenging to create novel drugs, especially the ones that are “first-in-class” medicines. Second of all, the clinical trials are longer and use more patients, increasing the cost and eating into patent life. The latest statistics say that it takes $1.3 billion to take a drug from idea to market after taking the failed drugs’ costs into account. This is the major reason why prescription drugs are so expensive because pharmaceutical companies need to recoup their investment so that they will have money to invest in discovering future new life-saving medicines. Therefore, today’s patent life of 20 years (the patent life was extended from 17 years to 20 since 1995) is insufficient for medicines, especially the ones that are “first-in-class.”

Therefore, patent life for innovative medicines should be extended because the risk is the highest, as is the failure rate. Since the life cycle from idea to regulatory approval is getting longer and longer, it would make more sense if the patent clock started ticking after the drug is approved while exclusivity is still provided after the filing

The current compensation system for the discovery of lifesaving drugs is in a dire need of reform as well. Top executives are receiving millions in compensation even as the company is laying off thousands of employees to reduce cost. Recently, Glaxo Smith Kline announced that the company will pay significant bonuses to scientists who discover drugs. This is a good start.

The phenomenon of blockbuster drugs was a harbinger of the golden age of the pharmaceutical industry. Patients were happy because taking medicines was vastly cheaper than staying in the hospital. Shareholders were happy because huge profit was made and stocks for big Pharma used to be considered a sure bet.

Perhaps most importantly, the drug industry expanded and employed more and more scientists to its workforce. That employment in turn encouraged academia to train more students in science. America’s Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics education was and still is the envy of the rest of the world. Maintaining that important reputation depends on a thriving pharmaceutical industry to provide jobs for our leading scientists and researchers. In turn they will reward us by discovering the next life-saving drugs.

Dr. Jie Jack Li is an associate professor at the University of San Francisco. He is the author of over 20 books on history of drug discovery, medicinal chemistry, and organic chemistry. His latest book being Blockbuster Drugs, The Rise and Decline of the Pharmaceutical Industry.

Chemistry Giveaway! In time for the 2014 American Chemical Society fall meeting and in honor of the publication of The Oxford Handbook of Food Fermentations, edited by Charles W. Bamforth and Robert E. Ward, Oxford University Press is running a paired giveaway with this new handbook and Charles Bamforth’s other must-read book, the third edition of Beer. The sweepstakes ends on Thursday, 14 August 2014 at 5:30 p.m. EST.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Extending patent protections to discover the next life-saving drugs appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow medical publishing can drive research and careYouth and the new media: what next?Why hope still matters

Related StoriesHow medical publishing can drive research and careYouth and the new media: what next?Why hope still matters

Gaming the system

2014 is the year of role-playing…November marks the 10th anniversary of World of Warcraft, the first truly global online game, and in January gamers celebrated the 40th anniversary of Dungeons & Dragons, the fantasy game of elves and dwarves, heroes and villains, that changed the world.

When Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) became popular in the late 1970s and early 1980s, many commentators lambasted the game as a gateway to amorality, witchcraft, Satanism, suicide, and murder. Of course, such accusations were no more substantive than the claim that vicious tricksters put needles in Halloween candy, and eventually everyone saw through them. In fact, the only thing that D&D’s detractors got right is that D&D competed against the conservative religions that attacked them.

Those original D&D books were and remain sacred texts. Finding an out-of-print copy of Deities and Demigods was a religious experience in the 1980s. It was impossibly rare, appearing once a year behind the counter at the comic book shop and with a plastic bag protecting it from the mundane dust, dirt, and fingerprints that could sully its sacred value (and it’s high price). The magic of Unearthed Arcana could inspire the spirit, renewing a love of the game through new rules and new treasures. Like any good sacred text, the handbooks of D&D enthralled the players and gave them dreams worth dreaming. In doing so, they gave them opportunities to be more than anyone else had ever hoped. Dungeons & Dragons made heroes of us all.

As the devoted fans of D&D grew up and, more often than not, gave up the game and its requisite all-night forays against evil, fueled by junk food, soda, or beer, they nevertheless carried it with them in their hearts and their minds. Dungeons and Dragons never changed people into Satanists and murderers, but it did change them. All of those years carrying a Player’s Handbook or a Dungeon Master’s Guide couldn’t help but reshape the bodies that lugged them around or the minds that fixated upon their contents. Those books encouraged adventure, and a desire to go one step further, even in the face of cataclysmic danger. Let the mysterious be understood, for there is always another mystery to uncover.

Dungeons & Dragons was a revelation. It didn’t come—as far as we know—from any gods, but it revealed the future. Today more than 90% of high school students play videogames and the demographics just keep getting better for the manufacturers. Every time a new Marvel comics-themed movie hits the theaters, it goes radioactive, raking in many times over its enormous cost to film. The religions of Star Trek and Star Wars have played a part in this cultural turn, and they get most of the mainstream credit. But it was the subtler impact of D&D that really re-shaped the world. Dungeons & Dragons provided the intellectual and imaginative space that has produced many of today’s great writers, technology entrepreneurs, and even academics. The game is a game of imagination, and its players—whether they gave up when they graduated high school or college or whether they play now with their friends and their children—never forgot what it means to imagine a world. They’ve been re-imagining this one into their image of it and we should all be thankful for the opportunity to play in their world.

Robert M. Geraci is Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at Manhattan College. He was the principle investigator on a National Science Foundation grant to study virtual worlds and the recipient of a Fulbright-Nehru Senior Research Award (2012-2013), which allowed him to investigate the intersections of religion and technology at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. He is the author of Apocalyptic AI: Visions of Heaven in Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, and Virtual Reality; Virtually Sacred: Myth and Meaning in World of Warcraft and Second Life; and many essays that analyze the ways in which human beings use technology to make the world meaningful.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Dungeons and Dragons (meets Warhammer…) by Nomadic Lass. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Gaming the system appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesYouth and the new media: what next?Gods and mythological creatures of the Odyssey in artHate crime and community dynamics

Related StoriesYouth and the new media: what next?Gods and mythological creatures of the Odyssey in artHate crime and community dynamics

Hate crime and community dynamics

Hate crimes are offences that are motivated by hostility, or where some form of demonstration of hostility is made, against the victim’s identity. Such crimes can have devastating impacts, both on those directly victimised and on other community members who fear they too may be targeted. While much has been written about the impacts of hate crime victimisation, there has been little which has focused on how the criminal justice system can effectively address the consequences of hate — other than through criminalising and punishing offenders.

A relatively new theory and practice of criminal justice is that of “Restorative Justice” (RJ). RJ seeks to bring the “stakeholders” of an offence together via inclusive dialogue in order to explore what has happened, why it happened, and how best those involved in the offence can repair the harms caused. There is now a substantial body of research into the effectiveness of RJ for violent and non-violent offences. Yet there has been little attention paid to whether such a process can effectively address crimes motivated by identity-based prejudice.

The harms caused by prejudice-motivated crime can relate both to the individual traumas experienced by victims, and the structural harms faced by many marginalised communities. The individual and structural harms caused by hate crime are not easily remedied. The current approach to combating hate crime via criminalisation and enhanced penalties, while important symbolically to the combatting of hate crime, does little to directly repair harm or challenge the underlying causes of hate-motivated offending.

In order to understand more about the reparative qualities of Restorative Justice for hate crime an empirical study of RJ projects was conducted where practices were used to address the causes and consequences of hate crime offences. The 18 month project involved 60 qualitative interviews with victims, restorative practitioners, and police officers who had participated in a restorative practice. In addition, 18 RJ meetings were observed, many of which involved face-to-face dialogue between victim, offender, and their supporters. One such project, administered by the Hate Crimes Project at Southwark Mediation Centre, South London, used a central restorative practice called Community Mediation, which employs a victim-offender or family group conferencing model. The cases researched involved “low-level” offences (including crimes aggravated by racial, religious, sexual orientation, and disability hostility) such as causing harassment, violence, or common assault, as well as more serious forms of violence including several cases of actual bodily harm and grievous bodily harm.

In the Southwark Hate Crimes Project, the majority of complainant victims (17/23) interviewed stated that the mediation process directly improved their emotional wellbeing. Further exploration of the process found that the levels of anger, anxiety, and fear that were experienced by almost all victims were reduced directly after the mediation process. Victims spoke at length about why the dialogical process used during mediation helped to improve their emotional wellbeing. First and foremost, participants felt they could play an active role in their own conflict resolution. This was especially important to most victims who felt that they had previously been ignored by state agencies when reporting their experiences of victimisation. Many noted that they were finally being listened to and their victimisation was now being taken seriously.

It was of utmost importance to victims that the perpetrator signed an agreement promising to desist from further hate incidents. In terms of desistance, 11 out of 19 separate cases of ongoing hate crime incidents researched in Southwark ceased directly after the mediation process had taken place (participants were interviewed at least six months after the mediation process ended). In a further six cases incidents stopped after the community mediator included other agencies within the mediation process, including schools, social services, and community police officers.

Unfortunately, the positive findings reported from Southwark were not repeated for the restorative policing measures used for low-level offences by Devon and Cornwall Police. Just half of the 14 interviewees stated that they were satisfied with the outcome of their case, where an alternative restorative practice, called Restorative Disposal was used. There were several reasons for lower levels of harm reparation at Devon and Cornwall, most of which were directly linked to the (lack of) restorativeness of the intervention. For example, several participants felt pressured by the police to agree to the intervention which had direct implications for the voluntariness of the process – a key tenet of restorative justice theory and practice.

Collectively, these results suggested that where restorative justice is implemented by experienced practitioners committed to the values of “encounter,” “repair,” and “transformation” it could reduce some of the harms caused by hate. However, where Restorative Justice was done “on the quick” by facilitators who were not equipped with either the time or resources to administer RJ properly, victims will be left without adequate reparation for the harms they have endured.

Another key factor supporting the reparative qualities of restorative practice, is reconceptualising the central notion of “community”. It is important to understand the complex dynamics of “community” by recognising that it may have certain invidious qualities (that are causal to hate-motivated offences) as well as more benevolent virtues. Equally, “community” may provide a crucial conduit through which moral learning about “difference” can be supported and offenders can be reintegrated into neighbourhoods less likely to reoffend.

Although the notion of community is an elusive concept, it is important for the future use of restorative practices for practitioners to view community organisations as important components of local neighbourhoods. These organisations (including neighbourhood policing teams, housing associations, schools, colleges, and social services) have an important role to play in conflict resolution, and must work together using a multi-agency approach to addressing hate crime. Such an approach, if led by a restorative practitioner, allows the various agencies involved in tackling hate victimisation to combine their efforts in order to better support victims and manage offenders. Hence, Restorative Justice may have scope to not only mitigate against the traumas of direct victimisation but also some of the structural harms that marginalised groups continue to experience.

Dr Mark Austin Walters is a Senior Lecturer in Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at the University of Sussex, and the Co-Director of the International Network of Hate Studies. He is the author of Hate Crime and Restorative Justice: Exploring Causes and Repairing Harms, which includes a full analysis of the impacts of hate crime, the use of restorative justice, multi-agency partnerships and the importance of re-conceptualising “community” in restorative discourse in cases involving “difference”. A full text of the book’s introduction ‘Readdressing Hate Crime’ can be accessed online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Southwark bridge at night, by Ktulu. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Hate crime and community dynamics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy do prison gangs exist?Supporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central AmericaTransforming conflict into peace

Related StoriesWhy do prison gangs exist?Supporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central AmericaTransforming conflict into peace

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers