Oxford University Press's Blog, page 775

August 13, 2014

The history of the word “qualm”

Once John Cowan suggested that I touch on the murky history of the noun qualm and try to shed light on it. To the extent that I can trust my database, this word, which is, naturally, featured in all dictionaries, hardly ever appears in the special scholarly literature. The OED online opens the entry on qualm with a long discussion, weighs arguments on its origin, but offers no definitive solution. Everybody, including Elmar Seebold, the editor of Kluge’s etymological dictionary of German, believes that the early history of qualm is “obscure.” In my opinion, the obscurity is considerably less impenetrable than it seems to most. Below I’ll risk saying what I think about the subject without any support of our best authorities, past or present.

The facts are as follows. Engl. qualm turned up in texts in the sixteenth century. It meant “a sudden fit, impulse, or pang of sickening, misgiving, despair; a fit or sudden access of some quality, principle, etc.; a sudden feeling or fit of faintness or sickness” (OED). The first sense is still alive. Nowadays, the plural occurs more often, as in qualms of conscience, she had no qualms about…, and the like. Even when, as happens in this case, an English word has an almost unquestionable Germanic etymology but surfaces so late, there is a good chance that it is a borrowing.

German Qualm means “(a thick) smoke, vapor,” but the first recorded sense was “daze, stupefaction.” It too appeared in texts only in the sixteenth century, and the same conclusion must be valid for it as for its English look-alike. German researchers are positive that the word came to their Standard from Low (northern) German, and we should agree with them. “(Thick) smoke” and “sickness, nausea” are not incompatible: the first can cause the second. “Stupefaction” must be a later sense, and it is close to “a sudden pang of sickness” found in English.

In Soest (Westphalia, northern Germany), qualm means “a great quantity” (for example, of birds). This was noticed by Friedrich Holthausen, a native of Soest. A leading philologist for many decades, he briefly discussed the local form in a journal article and later cited all the relevant words in his etymological dictionary of Old English. He also recorded the dialectal verb quullern “to gush (out, forth),” perhaps a cognate of Old Engl. collen “swollen,” known only as the first element of two compounds. Quull-er-n is obviously allied to German quell-en “to pour, stream” (the noun Quelle means “spring, source”). It does not look like a daring hypothesis to reconstruct the initial meaning of this family of words as “a mass of water or vapor (smoke) rising to the surface.” This may explain the sense of dialectal qualm “a great quantity,” with its reference to a flock of birds in the air.

Specification came later: from “smoke” to “suffocating smoke” and even further, as in the related German noun Qual, to “torment, pain, agony.” Old Engl. cwellan “to kill,” a congener but not the etymon of kill, continues into the modern language, though with a weakened meaning, as quell “extinguish.” Qual and Qualm are cognate. “Torment” and “daze, stupefaction” are close; final -m in Qualm is a suffix well-attested in Old Germanic and causes no trouble. Old Engl. cwelm ~ cwealm, derived from the same root, meant “pain, pestilence.”

The question about the origin of qualm (or rather of its German etymon) would have been settled once and for all but for the existence of another word, namely Old High German twalm “thick vapor; stupefaction,” an unexpected twin of Qualm with a different initial consonant group. It is the relation of twalm and Qualm that is supposed to be the real crux. Twalm, which did not survive the Middle High German period, has an instructive Old English cognate: dwalma “chaos” (Engl. d regularly corresponds to German t, as in do [Old Engl. don] ~ tun; Old Saxon had dwalm). Stupefaction and stupidity figure prominently in both Old English and German, as follows from Old Engl. dol “foolish,” dwol “heretical,” dwola “error, heresy,” dwolian “go astray,” dwolman “one who is in error, heretic,” and several compounds like dwolgod “false god, idol.” Modern Engl. dull is a borrowing of the cognate Middle Low German dul. All those words are related to the verb dwell, from dwellan “go astray, lead astray, deceive.”

Quark (cheese) blintzes with blackberries. Photo by Susánica Tam. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Quark (cheese) blintzes with blackberries. Photo by Susánica Tam. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.As we can see, Old English had cwellan “kill” and dwellan “deceive.” Two German nouns correspond to them: Qualm (recorded late but, most probably, old) and twalm (an old word, now extinct). The groups—dwellan ~ dwalm ~ twalm and cwellan ~ qualm—are not related. But in scholarship some questions tend to live a dull, almost heretical life of their own. In a few German words, one of them being Quark, sometimes loosely glossed as “curds, cottage cheese” but often left untranslated, kw- arose by the change tw- to kw-, and the question haunts researchers whether qualm could also be the product of that sound change. Perhaps it could, but Occam’s razor exists expressly for such cases and advises us not to multiply moves unless necessary: the fewer superfluous assumptions are made, the better. Since we have a convincing derivation of qualm, why raise the ghost of its going back to twalm? Let us grant each of those words its independent existence. To be sure, two such nouns, which sounded alike and often had similar meanings, could interact, but, since this process cannot be observed or reconstructed, it need not bother us.

Here then is my summary. From the root cwell- (or kwell-) “gush forth” the noun cwal-m (or kwal-m, qual-m) was derived. Its initial meaning must have been approximately “a mass of fluid or vaporous substance rising (forcefully) to the surface.” Later the noun acquired negative and figurative connotations, such as “thick, suffocating smoke; nausea; torment; daze, stupefaction.” A parallel formation had no suffix (qual). The root dwell- yielded a similar-sounding noun: dwalm (twalm). The meanings of qualm and dwalm sometimes overlapped, but those were distinct (unrelated) words. English borrowed qualm from Low German. The same seems to be true of High German Qualm and of the related Scandinavian nouns, which I have not discussed here, for their history would not have added anything to what we already know.

If the above looks like dry stuff, it has the advantage of offering a solution rather than a vague reference to complexity and ignorance. To make amends, here is a supplement. At one time, the Modern English verb quail “to lose heart, falter, cower” was traced to Old Engl. cwelan “die” and cwellan “kill.” Hensleigh Wedgwood disagreed. He identified quail “falter” with quail “to curdle” and traced it to Latin coagulare “coagulate.” Skeat knew his opinion but believed that the two verbs were homonyms. (The bird name quail is distinct, though it too was once drawn into the picture.)

It is amusing to quote A. L. Mayhew, a good language historian and bellicose critic. With reference to those who treated cwelan or cwellan as the etymon of quail, he wrote (1906): “It never seems to have occurred to these scholars that such an etymology is quite inadmissible, as the vowel sound of quail cannot be made to correspond with the original vowel of Old English cwelan or cwellan. Wedgwood didn’t care a brass button about phonetic laws, but he had a very keen sense for what is probable in the connection and the etymology of our word quail. He says: ‘To quail, as when we speak of one’s courage failing, is probably a special application of quail in the sense of curdle.’…It is the same word as Fr. cailler, to curdle, coagulate, a sister form of which is Ital. cagliare.” The same argument has been made more than once, and Skeat reluctantly changed his opinion.

This brings my blood-curdling story to an end.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The history of the word “qualm” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThere are more ways than one to be thunderstruckMonthly etymology gleanings for July 2014Which witch?

Related StoriesThere are more ways than one to be thunderstruckMonthly etymology gleanings for July 2014Which witch?

The environmental case for nuclear power

Time is running short. When the IPCC published its first scientific report in 1990 on the possibility of human-caused global warming, the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) was 354 ppm. It is now 397 ppm and rising. In spite of Kyoto, Copenhagen, Cancun, Durban, and Doha, atmospheric CO2 continues its inexorable upward path.

And the earth continues to warm. Each of the last four decades has been warmer than the previous one. Sea levels continue to rise, the oceans are acidifying, glaciers and ice sheets continue to melt, the Arctic will likely be ice-free during the summer sometime this century, and weather extremes have become commonplace around the earth. We are playing a dangerous game with the earth and ignoring the potential consequences. It is time to get serious about recognizing what we are doing to the earth and drastically reduce our production of CO2.

Forty percent of all energy used in the US is devoted to producing electricity. In spite of energy conservation, the EIA expects the use of electricity to increase by 30% in 2040, while total energy consumption is expected to increase by 12%. The big question is: can we generate the electricity in a manner that drastically reduces the production of CO2?

Coal is the big problem for electricity generation, and carbon capture and storage technology is not going to solve the problem. Coal needs to be essentially eliminated as a power source because of its multitude of health and environmental consequences. Coal provides about 43% of our electricity, and the actual amount of coal used is expected to increase through 2040, even though the percentage of electricity generated by coal would be slightly decreased by then. That is untenable if we want to reduce CO2 emissions. Coal usage generates about two billion tons of CO2 annually in the United States. Natural gas generates about half the CO2 as coal, but fugitive emissions of methane reduce or eliminate its usefulness, and fracking is controversial.

Renewable energy can help. But energy from the sun and wind have major difficulties associated with intermittency, location relative to population centers, footprint, and cost that limit their contributions to about 20% or less of electricity production. Even worse, they do not effectively contribute to the baseload electricity that coal provides. Baseload is the minimum electrical demand over a 24-hour day that must be provided by a constant source of electricity. Solar and wind power contribute principally to the intermediate demand that fluctuates during the day, but they still require backup — usually with natural gas power plants — for when they are not available. An increase from the current 4% to 20% of electricity would be an enormous help. But it does not solve the coal problem.

Nuclear power is the only alternative to coal for stable baseload power that can truly cut the emissions of CO2 to nearly zero. It currently provides 20% of electricity in the United States. It would take about 175 Generation III nuclear reactors to replace all of the coal-fired power plants in the United States. This would take a major national effort, but it would also require a major national effort to get 20% of electricity from wind and solar and that would not reduce coal usage. Neither of these goals will be achieved unless there is a cost associated with CO2 production through some kind of carbon tax. And that will only happen if there is a strong public demand that we get serious about reducing CO2 emissions and halting global warming.

What about the risks of nuclear power? The reality is that nuclear power has a much better safety record than coal. Since the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident (that killed no one), US coal mining caused 1,969 direct deaths. Deaths from black lung (pneumoconiosis) were over 2,500 in 1979 alone and continue to be hundreds per year. Deaths in the general public from lung disease are estimated to be in the thousands per year. No one in the United States has ever died from a nuclear power reactor accident in over 3,500 reactor-years of experience. It is vastly worse in China where several thousand miners die yearly, and several hundred thousand people die from respiratory diseases related to coal burning.

The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear accident caused 31 immediate deaths, 19 delayed deaths in emergency workers and 15 children who died from thyroid cancer. The best scientific estimates are that 4,000 more people may ultimately die from cancer. The tsunami that caused the nuclear accident in Fukushima in 2011 killed nearly 19,000 people and destroyed or damaged over a million buildings. No one has died from the nuclear accident, and it is likely that very few ever will. Even with these accidents, nuclear power has a far safer record than coal.

I am an environmentalist but most environmental groups are opposed to nuclear power. I challenge environmentalists to look at the environmental cost of depending on coal and measure that against the actual risks from nuclear power. Even in the worst accident — Chernobyl — the effects were localized, but the atmospheric effects of burning coal are worldwide. If environmentalists continue to oppose nuclear power, coal will still be providing most of the world’s electricity 50 years from now and the earth will be on a path to catastrophic warming.

The choice is ours. I believe the best choice is to reduce global warming by replacing most coal power plants with nuclear power. I hope we have the wisdom to take that path.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Dukovany Nuclear Power Station, Czech Republic. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The environmental case for nuclear power appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe life of oceans: a history of marine discoveryIf it’s 2014, this must be SacramentoNicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistry

Related StoriesThe life of oceans: a history of marine discoveryIf it’s 2014, this must be SacramentoNicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistry

The gender gap in pay in Spanish company boards

Is there gender gap in pay on the boards of listed Spanish firms? If there is, what are the factors behind the gender gap in pay? We sought to find out the answers to these questions.

Over the last few decades, payments for men have been consistently higher than those for women, even when they hold the same post and have been educated to the same level. This has created a gender gap in pay. Several studies have analysed the existence of such gender gaps in pay in national and international contexts and have shown that this gender gap in pay was caused by occupational segregation and various other factors that can be explained by human capital theory. Occupational segregation meant that women were being excluded from certain kinds of work, and tended to be concentrated in occupations with low salaries (Bayard et al., 1999; De la Rica, 2007). On the other hand, the human capital approach is focused on individuals investing themselves; i.e. adopting certain strategies to increase their own knowledge, experience and skills over the years (Amarante and Espino, 2002; Varela et al., 2010).

Spanish society was traditionally characterized by a strong ideology based on the idea that women should be dedicated to family life, which explained the low numbers of women in the labour market. However, between the 1970s and the 1990s, many changes in legislation governing the treatment of men and women were introduced. There has long been a general belief that one of the fundamental characteristics of the Spanish labour market was, and is, the persistent and strong wage gender discrimination in similar jobs: men are clearly paid more than women. To solve this problem, organisms and regulators have developed a set of standards and regulations to guarantee that women are employed under equal conditions to men and to prevent male-female director’s compensation discrimination. Among these regulations, Article 14 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978, the Workers’ Statute Act of 1980, the 3rd Plan for Equal Opportunities for Men and Women (1997-2000) and the Act 3/2007 for Equality Law have all been produced.

We posit that the percentage of female directors on boards, the presence of female directors on Nomination and Compensation Committees, the presence of well-qualified independent female directors on boards of directors (BDs), the firm sector and the geographical region have an effect on the gender wage gap. When we observe the variable presence of women on the Nomination and Compensation Committee, we find that there is a gender gap in pay in Spanish listing firms. However, the presence of well-qualified independent women directors on BDs reduces the gender gap in pay. A similar pattern occurs with the firm sector since the male-female compensation difference between directors is smaller in the boards of financial services and property sector firms. The remainder of variables analysed have no effect on the gender gap in pay.

This has special relevance in a country like Spain because the previous literature is based on that of English-speaking nations, as well as certain Eastern European and Asian countries. Moreover, previous empirical findings on the gender gap in pay use data from the European Structure of Earnings Survey (ESES).

Our results provide evidence that there is gender gap in pay in Spanish BDs. This study should encourage regulators and politicians to strive to bring about changes in legislation in order to reduce or eliminate the gender gap in pay. Moreover, they need to provide effective and strong sanctions for non-compliance with laws.

Image credit: Madrid, Cuatro Torres Business Area, by Hakan Svensson. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The gender gap in pay in Spanish company boards appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEducation and crime over the life cycleWhat is the role of governments in climate change adaptation?Improving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna Atkeson

Related StoriesEducation and crime over the life cycleWhat is the role of governments in climate change adaptation?Improving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna Atkeson

Anthropology and Christianity

The relationship between anthropologists and Christian identity and belief is a riddle. I first became interested in it by studying the intellectual reasons for the loss of faith given by figures in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. There are an obvious set of such intellectual triggers.

They were influenced by David Hume or Tom Paine, for example. Or, surprisingly often, it was modern biblical criticism. The big intellectual guns, of course, were figures such as Darwin, Marx, and Freud (and perhaps we can also squeeze Nietzsche in as a kind of d’Artagnan alongside those Three Musketeers). The so-called acids of modernity eat away at traditional religious claims.

As I accumulated and analyzed actual life stories, however, I hit one such trigger that had not been explored by scholars: the discipline of anthropology. It is not hard to find studies – sometimes daunting heaps of them – on Christianity and evolution or Christianity and Marxism and so on, but it was not clear to me what anthropology had to offer that was so unsettling to Christianity. Nor could I find where to go to read about it. Then there was the self-reporting of anthropologists. I’m a historian so I was coming at the discipline as an outsider. Every anthropologist I talked to, however, confidently told me that anthropology was and always had been from its very beginning a discipline that was dominated by scepticism and the rejection of faith.

Many were quite willing to go so far as to call it anti-Christian in ethos. They reported this whether they themselves were personally religious or hostile to religion – whether they self-identified as Catholic, evangelical, liberal Protestant, Jewish, secular, or atheist. If my random encounters were not profoundly unrepresentative, it seemed to be a consensus opinion. And it was not hard to find printed sources that also offered this assessment emphatically.

But then something strange began to happen. As I had shown interested in the relationship between anthropology and Christianity, my informants (to use an anthropological category!) would also casually mention as a kind of irrelevant, quirky novelty that a certain leading anthropologist was a Christian.

“Of course, dear old Mary Douglas was a devout Catholic, you know.” Purity and Danger Mary Douglas? One of the most influential anthropologists theorists of the second half of the twentieth century – no, I didn’t know. “Curiously, Margaret Mead, to the bemusement of her parents, chose to become an Episcopalian in her teens and was an active churchwomen for the rest of her life, even serving on the Commission on Church and Society of the World Council of Churches.” Coming of Age in Samoa Margaret Mead? One of the most prominent public intellectuals of twentieth-century America? That is curious.

“Strange to say, Victor Turner, who had been an agnostic Marxist, converted to Catholicism as an adult.” Really? The anthropologist who got us all talking about liminality and rites of passage and so on? The theorist behind the work of whole generations and departments of anthropology? Curiouser and curiouser.

“Oh, Catholic converts interest you? Well, of course, the presiding genius of the golden age of Oxford anthropology, E. E. Evans-Pritchard was one, as was Godfrey Lienhardt, and David Pocock, and . . .”

“What is that you say? What about Protestants? Well, Robertson Smith was an ordained minister in the Free Church of Scotland. Another fun fact was that the Primitive Methodist missionary Edwin W. Smith became the president of the Royal Anthropological Institute.” And so it went on.

What is one to make of the strong perception that anthropologists are hostile to religion with the reality of all these Christian anthropologists hiding in plain sight? The answer to such a question would no doubt be a complicated one with multiple, entangled factors. One of them, however, clearly relates to changing attitudes over time regarding the intellectual integrity and beliefs of people in traditional cultures.

Early anthropologists who rejected Christian faith such as E. B. Tylor (often called the father of anthropology) and James Frazer (of Golden Bough fame) were convinced that so-called “primitive” people had not yet reached a stage of progress in which they could be rational and logical. These pioneering anthropologists saw Christianity as a vehicle that was perniciously carrying into the modern world the superstitious, irrational ways of thinking of “savages”.

As the twentieth century unfolded, however, anthropologists learned to reject such condescending assumptions about traditional cultures. As they came to respect the people they studied, they often decided that their religious life and beliefs also had their own integrity and merit. This sometimes led them to reevaluate faith more generally—and even more personally. This connection is particularly strong in the life and work of E. E. Evans-Pritchard. He was both an adult convert to Catholicism and a major, highly influential champion of the notion that peoples such as the Azande were not “pre-logical” but rather deeply rational.

Victor and Edith Turner went into the field as committed Marxists and agnostics with a touch of bitterness in their anti-Christian stance (Edith had been raised by judgmental evangelical missionary parents). The Turners’ dawning conviction that Ndembu rituals had an irreducible spiritual reality, however, ultimately led them to receive the Christian faith as spiritually efficacious, true, and as their own spiritual home.

When anthropologists today glory in their discipline’s rejection of faith they often have in mind a very specific form of belief: a highly judgmental, narrowly sectarian version of religious commitment that condemns the indigenous people they study as totally cut off from any positive, authentic spiritual knowledge and experience. Evans-Pritchard and Victor Turner, however, are typical of numerous Christian anthropologists who were convinced that the traditional African cultures they studied possessed a natural revelation of God.

The riddle of anthropologists and the Christian faith is at least partially solved by distinguishing between “the wrong kind of faith”—the rejecting of which is a standard trope in the discipline—from an ethnographic openness to spirituality which can surprisingly often find expression in Christian forms for individual theorists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Old Christian Cross, by Filipov Ivo. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Anthropology and Christianity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAleister Crowley and ThelemaWhy study trust?The exaltation of Christ

Related StoriesAleister Crowley and ThelemaWhy study trust?The exaltation of Christ

August 12, 2014

The life of oceans: a history of marine discovery

It pays to be nice. One of the most absolutely, emphatically wrong hypotheses about the oceans was coined by one of the most carefree and amiable people in nineteenth century science. It should have sunk his reputation without trace. Yet, it did not. He thought the deep oceans were stone cold dead and lifeless. They’re certainly not that. Even more amazingly, it was clear that the deep oceans were full of life even before he proposed his hypothesis — and yet the idea persisted for decades. He is still regarded as the father of marine biology. There’s a moral in that somewhere.

Edward Forbes was born a Manxman who early developed a love of natural history. He collected flowers, seashells, butterflies with a passion that saw him neglect, then fail dismally in, his studies: first as an artist (he had a fine talent for drawing) then as a doctor. He drifted into becoming some kind of itinerant naturalist who naturally shook things up around him. Going to the British Association meeting in Birmingham, he reacted to the formal atmosphere by decamping to a local pub, the Red Lion, and taking a good deal of the membership with him. There, fueled by beef and beer, they debated the great scientific ideas of the day. They expressed agreement or disagreement with debating points not by a show of hands, but growling like lions and fluttering their coat-tails (Forbes’s technique with the coat-tails was held up as a model for the younger Lions).

In 1841, Forbes was on board a surveying ship, the HMS Beacon, in the Mediterranean. He noticed that as they dredged in deeper waters, the dredge buckets brought up fewer types of marine organism. He extrapolated from that to propose the “azoic hypothesis” — that the deep oceans were dead. It seemed not unreasonable — as one climbs higher up mountains, life diminishes, then disappears. For it to do the same in the oceans would show a nice symmetry. The azoic hypothesis took hold.

The trouble was, even then, commercial ships — with sounding lines far longer than the Beacon’s dredge buckets could go — were occasionally pulling up starfish and other animals from as much as two kilometers down. That should have killed the azoic hypothesis stone dead. But it didn’t. As luck had it, the first reports of such things happened to be sent in by ship’s captains who were either known for telling tall tales or who were plain bad-tempered. They couldn’t compete with Forbes’s eloquence or charm.

It took quite a few years before the weight of evidence finally dragged down the azoic hypothesis. We now know that the Earth’s deep oceans are alive, the thriving communities sustained by a rain of nutrients from above. Edward Forbes’s brainchild is simply one of many of the ideas through which we have gained — tortuously — a better understanding of the Earth’s oceans.

There have been other extraordinary characters, too, involved in this story. The scientists who concocted the inspired lunacy of the American Miscellaneous Society (AMSOC), for example, where every member automatically became a founding member, and where one of the rules was that there were no rules. Crazy as it was, AMSOC led to the Ocean Drilling Program, which revolutionized our knowledge of the deep ocean floors, of the history of global climate and of very much else. It’s also one of the great unsung revolutions of world science — but then there’s much that concerns the oceans that deserves to be more widely known.

There are extraordinary characters involved, too, in the new frontier of ocean science: the oceans that exist, or once existed, on other worlds. There’s the unfortunate Giordano Bruno, who imagined far-off worlds like our own — and who was burned at the stake for expounding these and other heresies. There’s Svante Arrhenius, who, a century ago, got Mars exactly right (no chance of canals, or water, he said) — but got Venus quite wrong (a thoroughly wet planet, he thought, and not the dry baking hell we now know it to be). There’s the wonderful mistake, too, of the contaminated detectors on a spacecraft on Venus — that led to the discovery of the oceans that likely once existed there.

We discover seas on other planets and moons, even as we still try to understand our own Earthly oceans. Just how have they lasted so long? And how will they change — in the next century, and in the next billion years? The story of oceans is really, truly never-ending.

Jan Zalasiewicz is Senior Lecturer in Geology and Mark Williams is Professor in Geology, both at the University of Leicester. They are also co-authors of Ocean Worlds: The story of seas on Earth and other planets.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images: Underwater sea life – Public Domain via Pixabay. Jellyfish – Public Domain via Pixabay

The post The life of oceans: a history of marine discovery appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIf it’s 2014, this must be SacramentoTechnologies of sexinessNicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistry

Related StoriesIf it’s 2014, this must be SacramentoTechnologies of sexinessNicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistry

The teenage exploits of a future celebrity

Rising to prominence at lightning speed during World War II, Leonard Bernstein quickly became one of the most famous musicians of all time, gaining notice as a conductor and composer of both classical works and musical theater. One day he was a recent Harvard graduate, struggling to earn a living in the music world. The next, he was on the front page of the New York Times for his stunning debut with the New York Philharmonic in November 1943. At twenty-five, Bernstein was the newly appointed assistant conductor of the orchestra, and he stepped in at the last minute to replace the eminent maestro Bruno Walter in a concert that was broadcast over the radio.

At the same time – and with the same blistering pace — Bernstein had two high-profile premieres in the theater: the ballet Fancy Free in April 1944, and the Broadway musical On the Town in December that same year. For both, he collaborated with the young choreographer Jerome Robbins, and the two men later became mega-famous for West Side Story in 1957. Added to that, the writers of the book and lyrics for On the Town were Bernstein’s close friends Betty Comden and Adolph Green, whose major celebrity came with the screenplay for Singin’ in the Rain in 1952.

So 1944 was a key year for Bernstein in the theater. Yet he already had considerable experience with theatrical productions, albeit with neighborhood kids in the Jewish community of Sharon, Massachusetts, south of Boston, where his parents had a summer home, and as a counselor at a Jewish summer camp in the Berkshires.

Some of these productions were charmingly outrageous, including a staging of Carmen in Sharon during the summer of 1934, when Bernstein was fifteen. Together with his male friend Dana Schnittken, Bernstein organized local teens in presenting an adaptation of Carmen in Yiddish, with the performers in drag. “Together we wrote a highly localized joke version of a highly abbreviated Carmen in drag, using just the hit tunes,” Bernstein later recalled in an interview with the BBC. “Dana played Micaela in a wig supplied by my father’s Hair Company—I’ll never forget his blonde tresses—and I sang Carmen in a red wig and a black mantilla and in a series of chiffon dresses borrowed from various neighbors on Lake Avenue, through which my underwear was showing. Don José was played by the love of my life, Beatrice Gordon. The bullfighter was played by a lady called Rose Schwartz.” Bernstein’s father, who was an immigrant to the United States, owned the Samuel J. Bernstein Hair Company in Boston, which not only prospered mightily during the Great Depression but also provided wigs for his son’s theatrical exploits.

Bernstein conducting the Camp Onota Rhythm Band. Courtesy of Library of Congress

The young Leonard’s summer performances also involved rollicking productions of operettas by Gilbert and Sullivan. In the summer of 1935, he directed The Mikado in Sharon. Bernstein sang the role of Nanki-Poo, and his eleven-year-old sister Shirley was Yum-Yum. Decades later, friends of Bernstein who were involved in that production—by then quite elderly—recalled going with the cast to a nearby Howard Johnson’s Restaurant to celebrate. After eating a hearty meal, they stole the silverware! Being upright young citizens, they quickly returned it.

In the summer of 1936, Bernstein and his buddies produced H.M.S. Pinafore. “I think the bane of my family’s existence was Gilbert and Sullivan, whose scores my sister Shirley and I would howl through from cover to cover,” Bernstein later reminisced to The Book of Knowledge.

As a culmination of this youthful activity, Bernstein produced The Pirates of Penzance during the summer of 1937, while he worked as the music counselor at Camp Onota in the Berkshires. His future collaborator Adolph Green was a visitor at the camp, and Green took the role of the Pirate King.

A photograph in the voluminous Bernstein Collection at the Library of Congress vividly evokes Bernstein’s experience at Camp Onota. There, the youthful Lenny stands next to a bandstand, conducting a rhythm band of even younger campers. This is clearly not a stage production. But there he is – an aspiring conductor, honing his craft in the balmy days of summer.

As it turned out, Bernstein’s transition from teenage artistic adventures to mature commercial success—from camp T-shirts to tux and tails—took place in a blink.

Carol J. Oja is William Powell Mason Professor of Music and American Studies at Harvard University. She is author of Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War and Making Music Modern: New York in the 1920s (2000), winner of the Irving Lowens Book Award from the Society for American Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The teenage exploits of a future celebrity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEchoes of Billie Holiday in Fancy FreeAleister Crowley and ThelemaOn unauthorized migrants and immigration outside the law

Related StoriesEchoes of Billie Holiday in Fancy FreeAleister Crowley and ThelemaOn unauthorized migrants and immigration outside the law

Aleister Crowley and Thelema

The twelfth of August marks the Feast of the Prophet and his Bride, a holiday that commemorates the marriage of Aleister Crowley and his first wife Rose Edith Crowley in the religion he created, Thelema. Born in 1875, Crowley traveled the world, living in Cambridge, Mexico, Cairo, China, America, Sicily, and Berlin. Here, using Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism as our trusted guide, we take a closer look at the man and his religion.

Aleister Crowley, Golden Dawn. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1898 Alesiter Crowley was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn as Frater Perdurabo. The teachings of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn were based upon an imaginative reworking of Hermetic writings further informed by nineteenth-century scholarship in Egyptology and anthropology. The order was structured around the symbolism of the kabbalah and organized into temples that were run on strictly hierarchical lines. Authority was vested in leading individuals, and initiates were given a rigorous and systematic training in the “rejected” knowledge of Western esotericism. They studied the symbolism of astrology, alchemy, and kabbalah; were instructed in geomantic and tarot divination; and learned the underpinnings of basic magical techniques.

Aleister Crowley as Magus, Liber ABA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Crowley’s magical self, Perdurabo, was a part of his concept of selfhood. In his own words:

As a member of the Second Order [of the Golden Dawn], I wore a certain jewelled ornament of gold upon my heart. I arranged that when I had it on, I was to permit no thought, word or action, save such as pertained directly to my magical aspirations. When I took it off I was, on the contrary, to permit no such things; I was to be utterly uninitiate. It was like Jekyll and Hyde, but with the two personalities balanced and complete in themselves.

The base camp of 1902 expedition for K2. Aleister Crowley is in setted in the middle. By Jules Jacot Guillarmod. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1902, Aleister Crowley was a part of the team who made the second serious attempt to climb the world’s second highest summit, K2.

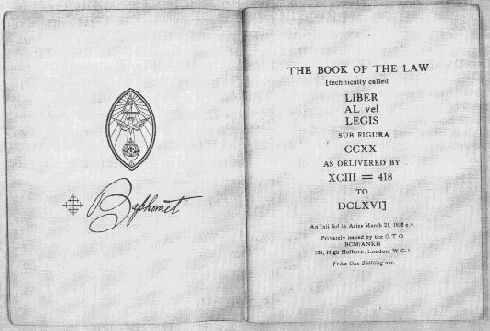

Frontpage from a published versions of Liber AL vel Legis. By Ordo Templi Orientis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In the spring of 1904, while on his honeymoon in Cairo, Egypt, he received a short prophetic text, which came to be known as Liber AL vel Legis or The Book of the Law. The book announces the doctrines of a new religion called Thelema, with Crowley—referred to in the book as “the prince-priest the Beast”—as its prophet.

The most important book of The Holy Books of Thelema, The Book of the Law is a channeled text that consists of 220 short verses divided into three chapters.

Aleister Crowley as Magus, Liber ABA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The core doctrines of this new creed of Thelema were expressed in three short dictums: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law,” “Love is the law, love under will,” and “Every man and every woman is a star.”

Thelema Abbey in Cefalù, Sicily, by Frater Kybernetes. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Thelema Abbey was established in the small Italian town of Cefalù in the period between 1920 and 1923. It consisted of one large house occupied by a small number of Crowley’s disciples and mistress(es). Life at the Abbey was for the most part Crowley’s attempt to translate his magical and Thelemic ideas into social reality. For the participants, the regime of life involved a great deal of occult and sex-magic activity as well as experiments with various mind-and mood-altering substances, such as hashish, cocaine, heroin, and opium.

Alyssa Bender is a marketing coordinator in Academic/Trade marketing, working on religion and theology titles as well as Bibles. She has worked in OUP’s New York office since July 2011.

Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism, edited by Henrik Bogdan and Martin P. Starr, is the first comprehensive examination of an understudied thinker and figure in the occult.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Aleister Crowley and Thelema appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGaming the systemOn unauthorized migrants and immigration outside the lawWhy study trust?

Related StoriesGaming the systemOn unauthorized migrants and immigration outside the lawWhy study trust?

August 11, 2014

If it’s 2014, this must be Sacramento

It is likely that most ecologists have their own stories regarding the annual meetings of the Ecological Society of America (ESA), the world’s largest organization of professional ecologists. Some revere it, whereas others may criticize it. There is, however, truth in numbers—growth in attendance has been seemingly exponential since my first meeting in the early 1980’s. So, it is without debate that the annual ESA meeting remains an integral part of the professional life of many ecologists throughout the world.

This year’s ESA meeting will take place in Sacramento, CA. Image credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

My first ESA meeting was at the Pennsylvania State University (note: we were small enough to meet on college campuses then) in 1982 while still a Ph.D. student at Duke University working with Norm Christensen on herb-layer dynamics of pine forests of the southeastern United States. I was understandably wide-eyed at seeing the actual human forms of ecologists walking around, giving talks, drinking beer—all of whom had only been names on papers and books I had read as I was writing my dissertation. Despite logistical errors regarding my talk (the projectionist insisted on placing my slides in the tray, rather than allowing me to do so; then promptly put them in backwards), my first ESA was an unmitigated success, allowing me to meet folks who would become lifelong friends and colleagues. Small surprise that I not only attended the next year, but have attended all meetings since then, save two—1991, when I could not afford to travel to Hawaii, and 2012, when my son was entering the United States Naval Academy.

Although I still recall high points of virtually all meetings through the years, the ones that stand out the most for me are those when I collaborated to organize symposia. There have been three of these: 1993 (University of Wisconsin—Madison), 1998 (Baltimore, Maryland), and 2006 (Savannah, Georgia). Although they were of somewhat contrasting themes, I took the same approach to all of them—I always thought that topics/presentations worthy of an ESA meeting were also worthy of some type of formal publication, whether in a peer-reviewed journal or a book.

My old Duke office mate/best friend/collaborator, Mark Roberts, and I organized a symposium on the effects of disturbance on plant diversity of forests for the 1993 meeting. Highly successful at the meeting, with very high attendance and vigorous question/answer periods following each talk, this symposium resulted in the publication of a Special Feature in Ecological Applications in 1995.

Mark and I used that first symposium as a kind of template for the one which was part of the 1998 meeting, well into the period where the number of attendees had outgrown college campuses, relegating ESA to convention centers. The 1998 symposium was on the ecology of herbaceous layer communities of contrasting forests of eastern North America. We had assembled what we felt was a very good group, including the late Fakhri Bazzaz, who was actually the first person I had contacted prior to writing the proposal for the Program Committee, also very successful in terms of attendance and questions. We were also pleased with our efforts on this topic following the symposium.

For the 2006 meeting, another friend and colleague of mine, Bill Platt, and I organized a symposium on the ecology of longleaf pine ecosystems. This experience was especially rewarding in that it was so closely connected with both the meeting theme of that Savannah (Uplands to Lowlands: Coastal Processes in a Time of Global Change), and the meeting’s geographic location in the main region of natural longleaf pine—the Coastal Plain of the southeastern United States. We published these talks in a Special Feature in Applied Vegetation Science.

Oh, there was another high point for me—one not related to symposia. It was with great pride that I accepted the nomination to become the Program Chair for the 2010 Annual Meeting of ESA in Pittsburgh, PA. I chose the following for the scientific theme: Global Warming: the Legacy of Our Past, the Challenge for Our Future. At a time when eastern US venues were not nearly as popular for attendance as were western ones, attendance at this meeting was surprisingly high. I was especially pleased to be able to thank the Society publicly and collectively when I addressed them at the beginning of the meeting.

Since my arrival in 1990 here at Marshall University—a public school small state (West Virginia ranks 38th among the 50 United States) and with limited direct access to colleagues doing similar research—annual ESA meetings have provided me a lifeline, if you will, connecting me with ecologists, especially biogeochemists and vegetation scientists, from throughout North America and, indeed, the world. Most of my contributions to the field of ecology, including peer-reviewed publications, book chapters, and books, have been products of this event that has not only become an annual summer tradition of mine, but also has been invaluable to my career as a plant ecologist.

It’s 2014, folks—see you in Sacramento!

Frank S. Gilliam is a professor of biological sciences, teaching courses in ecology and plant ecology, at Marshall University. He is also the editor of the second edition of The Herbaceous Layer in Forests of Eastern North America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post If it’s 2014, this must be Sacramento appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTechnologies of sexinessNicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistryThe health benefits of cheese

Related StoriesTechnologies of sexinessNicholson’s wrong theories and the advancement of chemistryThe health benefits of cheese

On unauthorized migrants and immigration outside the law

From news stories about unaccompanied minors from Central America to invisible workers without legal standing, immigration continues to stir debate in the United States. The arguments framing the issue are often inflected with distorted ideas and words. We sat down with Hiroshi Motomura, the author of Immigration Outside the Law, to discuss this contentious topic.

You use the term “unauthorized migrants” instead of “illegal” or “undocumented” immigrants. Why this choice of words?

This is a topic that is so controversial that even the labels provoke deep disagreement. The words “illegal” or “undocumented” often reflect very strong views. Because my goal is to explain what makes these debates so heated and then to analyze the issues carefully, I start with neutral terms, like “unauthorized” and “immigration outside the law.” I reach some firm conclusions about the nature of unauthorized migration and the best policy responses, but I try hard to work through the many arguments on both sides, acknowledging my own assumptions and taking all views seriously. This effort requires that I start with neutral terms.

What was the influence of the landmark 1982 US Supreme Court decision in Plyler v. Doe on our current discussion of immigration policy?

Plyler was pivotal. The Court said that the state of Texas couldn’t keep kids out of public schools just because they are in the United States unlawfully. It was a 5–4 decision, and we can debate whether the Court would come out the same way today. But Plyler it is much more than constitutional law. Plyler turned on three questions that remain at the heart of controversy. First, what does it mean to be in the United States lawfully––is “illegal” or “undocumented” more apt? Second, what is the state and local role in immigration policy? Third, should unauthorized migrants be integrated into US society—are they “Americans in waiting”?

A photograph of the May 1st, “Day without an Immigrant” demonstration in Los Angeles, California. © elizparodi via iStockphoto.

Are unauthorized migrants “Americans in waiting”?

Many unauthorized migrants are Americans in waiting, meaning that their integration into American society should be recognized and fostered. Unauthorized migrants have contributed to US society, especially through work, often over a long period of time. Their contributions justify lawful immigration status and a path to citizenship. An argument that is just as strong, though less often heard, is that unauthorized migrants have come to the United States as part of an economic system that depends on them — to be tolerated when we need them and exposed to discretionary enforcement when we don’t. These two arguments aren’t mutually exclusive, and both find support in history and the reality of today’s America.

Can unauthorized migrants currently assert their rights within the US legal system?

Unauthorized migrants can assert rights in many settings. They can sue if an employer refuses to pay them. They have a right to due process in the courts. In many states, unauthorized residents are eligible for driver’s licenses and in-state tuition rates at public colleges and universities. They are not relegated to oblivion. Why not? These rights recognize in small ways that unauthorized migrants are Americans in waiting. To be sure, broad scale legalization proposals in Congress attract a lot of attention, but mini-legalizations take place every day in settings where decision-makers at all levels of government acknowledge the place of unauthorized migrants in American society.

What have state and local governments done to address immigration outside the law?

The state government authority was at the heart of Plyler, and the state and local role has been controversial ever since. States and localities have tried to enforce federal immigration laws directly or indirectly. Arizona’s SB 1070 is a prominent example. At the same time, other states and localities try to integrate unauthorized migrants, through driver’s licenses, ID cards, and access to higher education, and by curtailing cooperation with federal immigration enforcement. Does federal immigration authority displace both types of state or local laws? I think not. The compelling reason to limit state and local enforcement is preventative––so state and local officials can’t enforce immigration laws in ways that are selective and discriminatory. This concern doesn’t apply when states and localities recognize or foster the integration of unauthorized migrants.

A version of this article will appear in the UCLA School of Law alumni magazine.

Hiroshi Motomura is Susan Westerberg Prager Professor of Law at UCLA. He is the author of Immigration Outside the Law and Americans in Waiting.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post On unauthorized migrants and immigration outside the law appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy study trust?Hate crime and community dynamicsSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Related StoriesWhy study trust?Hate crime and community dynamicsSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Why study trust?

In many countries, including Britain, the Euro-elections in May showed that a substantial minority of voters are disillusioned with mainstream parties of both government and opposition. This result was widely anticipated, and all over Europe media commentators have been proclaiming that the public is losing trust in established politicians. Opinion polls certainly support this view, but what are they measuring when they ask questions about trust? It is a slippery concept which suggests very different things to different people. Social scientists cannot reach any kind of consensus on what it means, let alone on what might be undermining it. Yet most people would agree that some kind of trust in the political process is essential to a stable and prosperous society.

Social scientists have had trouble with the concept of trust because most of them attempt to reach an unambiguous definition of it, distinguishing it from all other concepts, and then apply it to all societies at different times and in different parts of the world. The results are unsatisfactory, and some are tempted to ditch the term altogether. Yet there self-evidently is such a thing as trust, and it plays a major role in our everyday life. Even if the word is often misused, we should not abandon it. My approach is different: I use the word as the focus of a semantic milieu which includes related concepts such as confidence, reliance, faith and belief, and then see how they work in practice in different historical settings.

The original impulse for Trust came from a specific historical setting: Russia during the 1990s. There I observed, at first hand, the impact on ordinary Russians of economic and political reforms inspired by Western example and in some cases directly imposed by the West. Those reforms rested on economic and political precepts derived from Western institutions and practices which dated back decades or even centuries – generating habits of mutual trust which had become so ingrained that we did not notice them anymore. In Russia those institutions and practices instead aroused wariness at first, then distrust, then resentment and even hatred of the West and its policies.

I learnt from that experience that much social solidarity derives from forms of mutual trust which are so unreflective that we are no longer aware of them. Trust does not always spring from conscious choice, as some social scientists affirm. On the contrary, some of its most important manifestations are unconscious. They are nevertheless definitely learned, not an instinctive part of human nature. It follows that forms of trust which we take for granted are not appropriate for all societies.

Despite these differences, human beings are by nature predisposed towards trust. Our ability to participate in society depends on trusting those around us unless there is strong evidence that we should not do so. We all seek to trust someone, even – perhaps especially – in what seem desperate situations. To live without trusting anyone or anything is intolerable; those who seek to mobilise trust are therefore working with the grain of human nature.

We also all need trust as a cognitive tool, to learn about the world around us. In childhood we take what our parents tell us on trust, whereas during adolescence we may well learn that some of it is untrue or inadequate. Learning to discriminate and to moderate both trust and distrust is extraordinarily difficult. The same applies in the natural sciences: we cannot replicate all experiments carried out in the past in order to check whether they are valid. We have trust most of what scientists tell us and integrate it into our world picture.

Because we all need trust so much, it tends to create a kind of herd instinct. We have a strong tendency to place our trust where those around us do so. As a senior figure in the Royal Bank of Scotland commented on the widespread profligacy which generated the 2008 financial crisis: “The problem is that in banks you have this kind of mentality, this kind of group-think, and people just keep going with what they know, and they don’t want to listen to bad news.”

Trust, then, is necessary both to avoid despair and to navigate our way through life, and it cannot always be based on what we know for certain. When we encounter unfamiliar people – and in the modern world this is a frequent experience – we usually begin by exercising an ‘advance’ of trust. If it is reciprocated, we can go on to form a fruitful relationship. But a lot depends on the nature and context of this first encounter. Does the other person speak in a familiar language, look reassuring and make gestures we can easily ‘read’? Trust is closely linked to identity – our sense of our own identity and of that of those around us.

On the whole the reason we tend to trust persons around us is because they are using symbolic systems similar to our own. To trust those whose systems are very different we have to make a conscious effort, and probably to make a tentative ‘advance’ of trust. This is the familiar problem of the ‘other’. Overcoming that initial distrust requires something close to a leap in the dark.

Whether we know it or not, we spend much of our social life as part of a trust network. Such networks can be very strong and supportive, but they also tend to erect around themselves rigid boundaries, across which distrust is projected. When two or more trust networks are in enmity with one another, an ‘advance’ of trust can only work satisfactorily if it proves possible to transform negative-sum games into positive-sum games. However, an outside threat helps two mutually distrusting networks to find common ground, settle at least some of their differences and work together to ward off the threat. When the threat is withdrawn, they may well resume their mutual enmity.

During the twentieth century the social sciences – and following them history – were mostly dominated by theories derived from the study of power and/or rational choice. We still talk glibly of the struggle between democracy and authoritarianism, without considering the kinds of social solidarity which underlie both forms of government. I believe we need to supplement political science with a kind of ‘trust science’, which studies people’s mutual sympathy, their lively and apparently ineradicable tendency to seek reciprocal relationships with one another, and also what happens when that tendency breaks down. It is supremely important to analyse forms of social solidarity which do not derive directly from power structures and/or rational choice. Among other things, such an analysis might help us to understand why certain forms of trust have become generally accepted in Western society, and why they are in crisis right now.

Geoffrey Hosking is Emeritus Professor of Russian History at University College London. A Fellow of the British Academy and an Honorary Doctor of the Russian Academy of Sciences, he was BBC Reith Lecturer in 1988. He has written numerous books on Russian history and culture, including Russian History: A Very Short Introduction and Trust: A History.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: David Cameron, by Valsts kanceleja. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why study trust? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHate crime and community dynamicsImproving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna AtkesonSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Related StoriesHate crime and community dynamicsImproving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna AtkesonSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers