Oxford University Press's Blog, page 778

August 7, 2014

Paul Otlet, Google, Wikipedia, and cataloging the world

As soon as humanity began its quest for knowledge, people have also attempted to organize that knowledge. From the invention of writing to the abacus, from medieval manuscripts to modern paperbacks, from microfiche to the Internet, our attempt to understand the world — and catalog it in an orderly fashion with dictionaries, encyclopedias, libraries, and databases — has evolved with new technologies. One man on the quest for order was innovator, idealist, and scientist Paul Otlet, who is the subject of the new book Cataloging the World. We spoke to author Alex Wright about his research process, Paul Otlet’s foresight into the future of global information networks, and Otlet’s place in the history of science and technology.

What most surprised you when researching Paul Otlet?

Paul Otlet was a source of continual surprise to me. I went into this project with a decent understanding of his achievements as an information scientist (or “documentalist,” as he would have said), but I didn’t fully grasp the full scope of his ambitions. For example, his commitment to progressive social causes, his involvement in the creation of the League of Nations, or his decades-long dream of building a vast World City to serve as the political and intellectual hub of a new post-national world order. His ambitions went well beyond the problem of organizing information. Ultimately, he dreamed of reorganizing the entire world.

What misconceptions exist regarding Paul Otlet and the story of the creation of the World Wide Web itself?

It’s temptingly easy to overstate Otlet’s importance. Despite his remarkable foresight about the possibilities of networks, he did not “invent” the World Wide Web. That credit rightly goes to Tim Berners-Lee and his partner (another oft-overlooked Belgian) Robert Cailliau. While Otlet’s most visionary work describes a global network of “electric telescopes” displaying text, graphics, audio, and video files retrieved from all over the world, he never actually built such a system. Nor did the framework he proposed involve any form of machine computation. Nonetheless, Otlet’s ideas anticipated the eventual development of hypertext information retrieval systems. And while there is no direct paper trail linking him to the acknowledged forebears of the Web (like Vannevar Bush, Douglas Engelbart, and Ted Nelson), there is tantalizing circumstantial evidence that Otlet’s ideas were clearly “in the air” and influencing an increasingly public dialogue about the problem of information overload – the same cultural petri dish in which the post-war Anglo-American vision of a global information network began to emerge.

What was the most challenging part of your research?

The sheer size of Otlet’s archives–over 1,000 boxes of papers, journals, and rough notes, much of it handwritten and difficult to decipher–presented a formidable challenge in trying to determine where to focus my research efforts. Fortunately the staff of the Mundaneum in Mons, Belgium, supported me every step of the way, helping me wade through the material and directing my attention towards his most salient work. Otlet’s adolescent diaries posed a particularly thorny challenge. On the one hand they offer a fascinating portrait of a bright but tormented teenager who by age 15 was already dreaming of organizing the world’s information. But his handwriting is all but illegible for long stretches. Even an accomplished French translator like my dear friend (and fellow Oxford author) Mary Ann Caws, struggled to help me decipher his nineteenth-century Wallonian adolescent chicken scratch. Chapter Two wouldn’t have been the same without her!

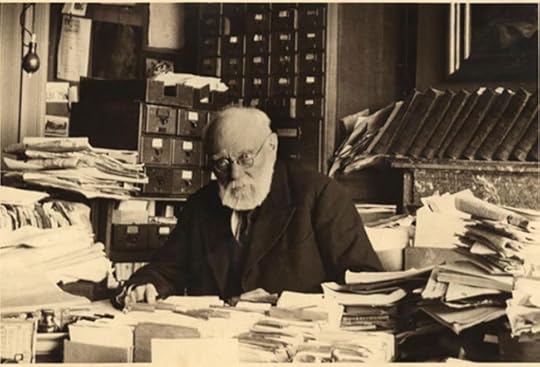

Photograph of Paul Otlet, circa 1939. Reproduced with permission of the Mundaneum, Mons, Belgium.

How do you hope this new knowledge of Otlet will influence the ways in which people view the Internet and information sites like Wikipedia?

I hope that it can cast at least a sliver of fresh light on our understanding of the evolution of networked information spaces. For all its similarities to the web, Otlet’s vision differed dramatically in several key respects, and points to several provocative roads not taken. Most importantly, he envisioned his web as a highly structured environment, with a complex semantic markup called the Universal Decimal Classification. An Otletian version of Wikipedia would almost certainly involve a more hierarchical and interlinked presentation of concepts (as opposed to the flat and relatively shallow structure of the current Wikipedia). Otlet’s work offers us something much more akin in spirit to the Semantic Web or Linked Data initiative: a powerful, tightly controlled system intended to help people make sense of complex information spaces.

Can you explain more about Otlet’s idea of “electronic telescopes” – whether they were feasible/possible, and to what extent they led to the creation of networks (as opposed to foreshadowing them)?

One early reviewer of the manuscript took issue with my characterization of Otlet’s “electric telescopes” as a kind of computer, but I’ll stand by that characterization. While the device he described may not fit the dictionary definition of a computer as a “programmable electronic device” – Otlet never wrote about programming per se – I would take the Wittgensteinian position that a word is defined by its use. By that standard, Otlet’s “electric telescope” constitutes what most of us would likely describe as a computer: a connected device for retrieving information over a network. As to whether it was technically feasible – that’s a trickier question. Otlet certainly never built one, but he was writing at a time when the television was first starting to look like a viable technology. Couple that with the emergence of radio, telephone, and telegraphs – not to mention new storage technologies like microfilm and even rudimentary fax machines – and the notion of an electric telescope may not seem so far-fetched after all.

What sorts of innovations would might have emerged from the Mundaneum – the institution at the center of Otlet’s “World City” – had it not been destroyed by the Nazis?

While the Nazi invasion signalled the death knell for Otlet’s project, it’s worth noting that the Belgian government had largely withdrawn its support a few years earlier. By 1940 many people already saw Otlet as a relic of another time, an old man harboring implausible dreams of international peace and Universal Truth. But Otlet and a smaller but committed team of staff soldiered on, undeterred, cataloging the vast collection that remained intact behind closed doors in Brussels’ Parc du Cinquantenaire. When the Nazis came, they cleared out the contents of the Palais Mondial, destroying over 70 tons worth of material, and making room for an exhibition of Third Reich art. Otlet’s productive career effectively came to an end, and he died a few years later in 1944.

It’s impossible to say quite how things might have turned out differently. But one notable difference between Otlet’s web and today’s version is the near-total absence of private enterprise – a vision that stands in stark contrast to today’s Internet, dominated as it is by a handful of powerful corporations.

Otlet’s Brussels headquarters stood almost right across the street from the present-day office of another outfit trying to organize and catalog the world’s information: Google.

Alex Wright is a professor of interaction design at the School of Visual Arts and a regular contributor to The New York Times. He is the author of Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age and Glut: Mastering Information through the Ages.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Paul Otlet, Google, Wikipedia, and cataloging the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesHow threatened are we by Ebola virus?Why are sex differences frequently overlooked in biomedical research?

Related StoriesWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesHow threatened are we by Ebola virus?Why are sex differences frequently overlooked in biomedical research?

Why you can’t take a pigeon to the movies

Films trick our senses in many ways. Most fundamentally, there’s the illusion of motion as “moving pictures” don’t really move at all. Static images shown at a rate of 24 frames per second can give the semblance of motion. Slower frame rates tend to make movements appear choppy or jittery. But film advancing at about 24 frames per second gives us a sufficient impression of fluid motion.

However, birds–such as pigeons–have a much higher threshold for detecting movement. A bird’s visual system is keenly sensitive to moving stimuli as this is essential to their survival. Whether swooping down to snatch live prey, fleeing from a predator, or zeroing in on a nest for a precise landing, birds must rely on their fine-tuned ability to hone in on moving targets. So the frame rate at which most of our films are shown is far too slow for birds to perceive continuous motion. Their threshold of visual processing exceeds the standard frame rate, allowing them to see component frames … and the illusion of motion pictures would be broken.

If a pigeon had been roosting in the theater where 19th century crowds first gaped at the Lumière Brothers’ steam train looming towards them, it may have been less than impressed — especially as early silent films were often played at only 16 frames per second.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Even a film shown at today’s industry standard of 24 frames per second would most likely look like a series of flashing slides to a pigeon. We’re mesmerized by Marilyn Monroe’s white skirts billowing over the subway grate in The Seven-Year Itch, but a pigeon may see something more like a slide show of the skirt in frozen increments.

Further, most humans cannot distinguish individual lights flashed at 60 cycles per second, perceiving instead a single continuous beam of light. This gives an impression of constant light while watching a film (despite the shutter actually shutting out light several times per frame). But birds have much higher critical flicker-fusion frequency, such as 90-100 cycles per second or higher (e.g., Lisney et al., 2011). So while humans do not perceive the flicker in a movie, a pigeon may see flashes like strobelights along with the jumpy frames of Marilyn’s airborne skirt.

One of the creepiest scenes in Hitchcock’s The Birds shows Melanie (Tippi Hedren) smoking on a bench in a school playground while birds are flocking on a jungle gym behind her. She finally spots a lone bird flying overhead and turns around to discover every rung of the jungle gym crowded with large black birds. Actually, Hitchcock used cardboard cut-outs for most of the “birds” on the jungle gym, figuring that most people would not notice these stationary objects if interspersed with live birds.

Birds in a school playground in Hitchcock’s (1964) The Birds

Indeed, the illusion works on most of us. We are also often tricked by illusory “crowds” in films–made of real people and dummies, or multiple images of the same people patched together to make a “crowd”. However birds are especially observant of the movement of other birds–and combined with the much faster ‘refresh rate’ of the avian visual system (as their visual information is “updated” more frequently than humans)–the jungle gym scene would not likely fool any birds.

Studies suggest that birds do perceive some information via video images (using video at 30 frames per second). For instance, a video of wild chickens feeding elicits feeding in birds of the same species (McQuoid & Galef, 1993); videos showing a hawk or raccoon elicit aerial and ground alarm calls respectively in roosters (Evans, Evans, and Marler, 1993); and video images of female pigeons elicit courtship displays in male pigeons (Shimizu, 1998).

So birds seem to pick up some information from video images, at a somewhat higher frame rate and screen-refresh rate than film–though color may be distorted (Wright & Cumming, 1971), and gaps in movement and flicker are likely perceived (Lea & Dittrich, 1999). These discrepancies would be much more pronounced for moving images on cinematic film.

A fine-tuned visual system gives birds of prey an advantage when pursuing a fast-moving target. And it allows pigeons those few extra seconds to peck at grubs and seeds–and flap away at the last moment possible when your car approaches.

Feral Rock Dove. Photograph by Andrew D. Wilson. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Nut their super-efficient processing of moving stimuli would make the cinematic experience as we know it less than spellbinding for the birds.

In conclusion: it’s interesting to note that film relies on certain limitations or imperfections of the human perceptual system for its magic to work!

Siu-Lan Tan is Associate Professor of Psychology at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA. She is primary editor of The Psychology of Music in Multimedia (Oxford University Press 2013), the first book consolidating the research on the role of music in film, television, video games, and computers. A version of this article also appears on Psychology Today. Siu-Lan Tan also has her own blog, What Shapes Film? Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why you can’t take a pigeon to the movies appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOK Go: Is the Writing on the Wall?How threatened are we by Ebola virus?Why are sex differences frequently overlooked in biomedical research?

Related StoriesOK Go: Is the Writing on the Wall?How threatened are we by Ebola virus?Why are sex differences frequently overlooked in biomedical research?

Why are sex differences frequently overlooked in biomedical research?

Despite the huge body of evidence that males and females have very different immune systems and responses, few biomedical studies consider sex in their analyses. Sex refers to the intrinsic characteristics that distinguish males from females, whereas gender refers to the socially determined behaviour, roles, or activities that males and females adopt. Male and female immune systems are not the same leading to clear sexual dimorphism in response to infections and vaccination.

In 2010, Nature featured a series of articles aimed at raising awareness of the inherent sex bias in modern day biomedical research and, yet, little has changed since that time. They suggested journals and funders should insist on studies being conducted in both sexes, or that authors should state the sex of animals used in their studies, but, unfortunately, this was not widely adopted.

Even before birth, intrauterine differences begin to differentially shape male and female immune systems. The male intrauterine environment is more inflammatory than that of females, male fetuses produce more androgens and have higher IgE levels, all of which lead to sexual dimorphism before birth. Furthermore, male fetuses have been shown to undergo more epigenetic changes than females with decreased methylation of many immune response genes, probably due to physiological differences.

The X chromosome contains numerous immune response genes, while the Y chromosome encodes for a number of inflammatory pathway genes that can only be expressed in males. Females have two X chromosomes, one of which is inactivated, usually leading to expression of the wild type gene. X inactivation is incomplete or variable, which is thought to contribute to greater inflammatory responses among females. The immunological X and Y chromosome effects will begin to manifest in the womb leading to the sex differences in immunity from birth, which continue throughout life.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) regulate physiological processes, including cell growth, differentiation, metabolism and apoptosis. Males and females differ in their miRNA expression, even in embryonic stem cells, which is likely to contribute to sex differences in the prevalence, pathogenesis and outcome of infections and vaccination.

Females are born with higher oestriol concentrations than males, while males have more testosterone. Shortly after birth, male infants undergo a ‘mini-puberty’, characterised by a testosterone surge, which peaks at about 3 months of age, while the female effect is variable. Once puberty begins, the ovarian hormones such as oestrogen dominate in females, while testicular-derived androgens dominate in males. Many immune cells express sex hormone receptors, allowing the sex hormones to influence immunity. Very broadly, oestrogens are Th2 biasing and pro-inflammatory, whereas testosterone is Th1 skewing and immunosuppressive. Thus, sex steroids undoubtedly play a major role in sexual dimorphism in immunity throughout life.

Sex differences have been described for almost every commercially available vaccine in use. Females have higher antibody responses to certain vaccines, such as measles, hepatitis B, influenza and tetanus vaccines, while males have better antibody responses to yellow fever, pneumococcal polysaccharide, and meningococcal A and C vaccines. However, the data are conflicting with some studies showing sex effects, whereas other studies show none. Post-vaccination clinical attack rates also vary by sex with females suffering less influenza and males experiencing less pneumococcal disease after vaccination. Females suffer more adverse events to certain vaccines, such as oral polio vaccine and influenza vaccine, while males have more adverse events to other vaccines, such as yellow fever vaccine, suggesting the sex effect varies according to the vaccine given. The existing data hint at higher vaccine-related adverse events in infant males progressing to a female preponderance from adolescence, suggesting a hormonal effect, but this has not been confirmed.

If male and female immune systems behave in opposing directions then clearly analysing them together may well cause effects and responses to be cancelled out. Separate analysis by sex would detect effects that were not seen in the combined analysis. Furthermore, a dominant effect in one of the sexes might be wrongly attributed to both sexes. For drug and vaccine trials this could have serious implications.

Given the huge body of evidence that males and females are so different, why do most scientific studies fail to analyse by sex? Traditionally in science the sexes have been regarded as being equal and the main concern has been to recruit the same number of males and females into studies. Adult females are often not enrolled into drug and vaccine trials because of the potential interference of hormones of the menstrual cycle or risk of pregnancy; thus, most data come from trials conducted in males only. Similarly, the majority of animal studies are conducted in males, although many animal studies fail to disclose the sex of the animals used. Analysing data by sex adds the major disadvantage that sample sizes would need to double in order to have sufficient power to detect significant sex effects. This potentially means double the cost and double the time to conduct the study, in a time when research funding is limited and hard to obtain. Furthermore, since the funders don’t request analysis by sex, and the journals do not ask for it, it is not a major priority in today’s highly competitive research environment.

It is likely that we are missing important scientific information by not investigating more comprehensively how males and females differ in immunological and clinical trials. We are entering an era in which there is increasing discussion regarding personalised medicine. Therefore, it is quite reasonable to imagine that females and males might benefit differently from certain interventions such as vaccines, immunotherapies and drugs. The mindset of the scientific community needs to shift. I appeal to readers to take heed and start to turn the tide in the direction whereby analysis by sex becomes the norm for all immunological and clinical studies. The knowledge gained would be of huge scientific and clinical importance.

Dr Katie Flanagan leads the Infectious Diseases Service at Launceston General Hospital in Tasmania, and is an Adjunct Senior Lecturer in the Department of Immunology at Monash University in Melbourne. She obtained a degree in Physiological Sciences from Oxford University in 1988, and her MBBS from the University of London in 1992. She is a UK and Australia accredited Infectious Diseases Physician. She did a PhD in malaria immunology based at Oxford University (1997 – 2000). She was previously Head of Infant Immunology Research at the MRC Laboratories in The Gambia from 2005-11 where she conducted multiple vaccine trials in neonates and infants.

Dr Katie Flanagan’s editorial, ‘Sexual dimorphism in biomedical research: a call to analyse by sex’, is published in the July issue of Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene publishes authoritative and impactful original, peer-reviewed articles and reviews on all aspects of tropical medicine.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Man and woman arm wrestling, © g_studio, via iStock Photo.

The post Why are sex differences frequently overlooked in biomedical research? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat are the costs and impacts of telecare for people who need social care?How threatened are we by Ebola virus?World Hepatitis Day: reason to celebrate

Related StoriesWhat are the costs and impacts of telecare for people who need social care?How threatened are we by Ebola virus?World Hepatitis Day: reason to celebrate

August 6, 2014

There are more ways than one to be thunderstruck

On 20 November 2013, I discussed the verbs astonish, astound, and stun. Whatever the value of that discussion, it had a truly wonderful picture of a stunned cat and an ironic comment by Peter Maher on the use of the word stunning. While rereading that short essay, I decided that I had not done justice to the third verb of the series (stun) and left out of discussion a few other items worthy of consideration. The interested readers may look upon this post as Part 2, a continuation of the early one.

Astonish and astound, despite the troublesome suffix -ish in the first of them and final -d in the second, are close cognates. Both go back to a Romance form reconstructed as ex-tonare. Latin tonare meant “to thunder”; tone, intone, and tonality contain the same root. To quote Ernest Weekley, “Some metaphors are easy to track. It does not require much philological knowledge to see that astonish, astound, and stun all contain the idea of ‘thunder-striking’, Vulgar Latin *ex-tonare.” (The asterisk designates an unattested form reconstructed by linguists.) Those lines saw the light in 1913. A century later “philological knowledge” has reached such a stage among the so-called general public that people’s readiness to draw any conclusions about the history of language should be taken with caution. But as regards the content, Weekley was right: the idea behind astonish ~ astound is indeed “thunderstruck.”

Thor, the thunder god (Bronzestatue „Christ or Þor“ aus dem isländischen Nationalmuseum, Photo by L3u, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

Weekley did not explain how a-s-toun- and thun-der are related. The hyphenation above shows that a- is a prefix. The root stoun- has a diphthong because the original vowel was long. Likewise, down, house, now, and many other words with ou (ow) had “long u” (the vowel of poo) in Middle English. The change is regular. Initial s- in stoun- is what is left of the prefix ex-; Old French already had estoner (Modern French lost even the last crumb: étonner). A Germanic correspondence of Latin t is th, as in tres ~ three, pater ~ father, and so forth; hence thunder (d has no claim to antiquity). All this is trivial. However, there are two suspicious details in our story: German staunen “to be amazed” and Engl. stun.

In my 2013 post, I followed old sources and called staunen a respectable relative of astonish and stun. However, its respectability and even relatedness to the English group has been rejected by modern scholars, so that an explanation is in order. (I am “astonished” that no one offered a correction. Usually the slightest misstep on my part—real or imaginary—arouses immediate protest.) Staunen, a verb borrowed by the Standard from Swiss German, originally meant “to stare” and has been compared with several words like stare that have nothing to do with thunder. “Stare; look dreamily” yielded, rather unexpectedly, the modern sense “to be amazed.” The recorded history of staunen “to be amazed” and erstaunen “amaze” cannot be questioned, but their etymology looks a bit strained, and I wonder whether some foreign influence could contribute to the similarity between astound and staunen.

A much thornier question concerns the history of Engl. stun. Old English had the verb stunian “crash, resound, roar; impinge; dash.” It looks like a perfect etymon of stun. Skeat thought so at the beginning of his etymological career and never changed his opinion. He compared stunian with a group of words meaning “to groan”: Icelandic stynja, Dutch stenen, German stöhnen, and their cognates elsewhere. Those are almost certainly related to thunder. Apparently, the congeners of tonare did not always denote a great amount of din.

The presence of s- in stenen and the rest is not a problem. This strange sound is like a barnacle: it attaches itself to the first consonant of numerous roots, though neither its function nor its origin has been explained in a satisfactory way. Such a good researcher as Francis A. Wood even mocked those who believed in its existence. Only a good name for this “parasite” exists (s mobile), and it has become a recognized linguistic term. S mobile disregards linguistic borders: doublets abound in the same language, as well as in closely and remotely related languages and outside it. For instance, the German for sneeze is niesen. Similar examples can be cited by the hundred.

This is not a phenomenon that happens only in old languages: in modern dialects, such doublets are also common. That is why some scholars who, in the past, tried to discover the origin of the word slang believed that they were dealing with French langue and s mobile; compare the modern jocular blend slanguage. (A convincing etymology of slang, which does not depend on s mobile, has been known for more than a hundred years, but dictionaries are unaware—fiction writers and journalists like to say blissfully unaware—of this fact.) Consequently, s-tun can be related to thunder—that is, if we recognize the existence of the capricious s mobile, an entity of the type “now you see it, now you don’t.”

However, stun “daze, render unconscious” surfaced in texts only in the early fourteenth century, while stunian “crash, etc.” does not seem to have survived into Middle English; only stonien “make a noise” has been recorded. The first edition of the OED stated cautiously that stun goes back to Old French estoner. (This word has yet to be revised for the new edition on OED Online.) The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology gives the solution endorsed by Murray and Bradley as certain. The Century Dictionary followed Skeat but admitted confusion with the French verb that yielded astonish and astound. Other respectable sources hedge, copy from their great predecessors, and prefer to stay noncommittal.

I have returned to my old post for one reason only. In investigating the history of stun, astound, and its look-alikes, we encounter the well-known difficulty: a word resembles another word in the same or another language, and it is hard to decide where, in making a connection, we hit the nail on its proverbial head and where we are on a false tack.

In 2013, I mentioned an old hypothesis according to which stun is related to stone. This hypothesis cannot be defended: at present we have sufficient means to disprove it. (In etymology it is usually easier to show that some conclusion is untenable than that it is true.) But in two other cases we may or should hesitate. Astound and staunen are so much alike in sound and sense that rejecting their affinity unconditionally may be too hasty. The situation is even more complicated with stun. Tracing it to Old French without a footnote produces the impression that ultimate clarity has been attained, but it has not. In etymology, the door is only too often open for legitimate doubt.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post There are more ways than one to be thunderstruck appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for July 2014Which witch?Living in a buzzworld

Related StoriesMonthly etymology gleanings for July 2014Which witch?Living in a buzzworld

Children learning English: an educational revolution

Did you know that the introduction of languages into primary schools has been dubbed the world’s biggest development in education? And, of course, overwhelmingly, the language taught is English. Already the world’s most popular second language, the desire for English continues apace, at least in the short term, and with this desire has come a rapid decrease in the age at which early language learning (ELL) starts. From the kindergartens of South Korea to classes of 70+ in Tanzania, very young children are now being taught English. So is it a good idea to learn English from an early age? Many people believe that in terms of learning language, the younger the better. However, this notion is based on children learning in bilingual environments in which they get a great deal of input in two or more languages. Adults see children seemingly soaking up language and speaking in native-like accents and think that language learning for children is easy. However, most children do not learn English in this kind of bilingual environment. Instead, they learn in formal school settings where they are lucky if they get one or two hours of English tuition a week. In these contexts, there is little or no evidence that an early start benefits language learning. Indeed, it has been argued that the time spent teaching English is better spent on literacy, which has been shown to develop children’s language learning potential.

So why are children learning from so young an age? One answer is parent power. Parents see the value of English for getting ahead in the global world and put pressure on governments to ensure children receive language tuition from an early age. Another answer is inequality. Governments are aware that many parents pay for their children to have private tuition in English and they see this as disadvantaging children who come from poorer backgrounds. In an attempt to level the playing field, they introduce formal English language learning in primary schools. While this is admirable, research shows that school English is not generally effective, particularly in developing countries, and in fact tends to advantage those who are also having private lessons. Another argument for sticking to literacy teaching?

Of course, government policy eventually translates into classroom reality and in very many countries the introduction of English has been less than successful. One mammoth problem is the lack of qualified teachers. Contrary to popular belief, and despite representations in film and television programmes, being able to speak English does not equate to an ability to teach English, particularly to very young children. Yet in many places unqualified native English speaking teachers are drafted into schools to make good the shortfall in teacher provision. In other countries, local homeroom teachers take up the burden but may not have any English language skills or may have no training in language teaching. Other problems include a lack of resources, large classes and lack of motivation leading to poor discipline. Watch out Mr Gove — similar problems lie in store for England in September 2014! (When the new national curriculum for primary schools launches, maintained primary schools will have to teach languages to children, and yet preparation for the curriculum change has been woefully inadequate.)

Why should we be in interested in this area of English language teaching when most of it happens in countries far away from our own? David Graddol, our leading expert on the economy of English language teaching, suggests that the English language teaching industry directly contributes 1.3 billion pounds annually to the British economy and up to 10 billion pounds indirectly through English language education related activities. This sector is a huge beneficiary to the British economy, yet its importance is widely unacknowledged. For example, in terms of investigating English language teaching, it is extremely difficult in England to get substantial funding, particularly when the focus is on countries overseas.

From the perspective of academics interested in this topic, which we are, the general view that English language teaching is not a serious contender for research funding is galling. However, the research funding agencies are not alone. Academic journals rarely publish work on teaching English to young learners, which has become something of a Cinderella subject in research into English language teaching. There are numerous studies on adults learning English in journals of education and applied linguistics, but ELL is hardly represented. This might be because there is little empirical research or because the area is not considered important. Yet as we suggest, there are huge questions to be asked (and answered). For example, in what contexts are children advantaged and disadvantaged by learning English in primary schools? What are the most effective methods for teaching languages to children in particular contexts? What kind of training in teaching languages do primary teachers need and what should their level of English be? The list of questions, like the field, is growing and the answers would support both the UK English language industry and also our own approach to language learning in primary schools, where there is very little expertise.

ELT Journal is a quarterly publication for all those involved in English Language Teaching (ELT), whether as a second, additional, or foreign language, or as an international Lingua Franca. The journal links the everyday concerns of practitioners with insights gained from relevant academic disciplines such as applied linguistics, education, psychology, and sociology. A Special Issue of the ELT Journal, entitled “Teaching English to young learners” is available now. It showcases papers from around the world that address a number of key topics in ELL, including learning through online gaming, using heritage languages to teach English, and the metaphors children use to explain their language learning.

Fiona Copland is Senior Lecturer in TESOL in the School of Languages and Social Sciences at Aston University, Birmingham, UK, where she is Course Director of distance learning MSc programmes in TESOL. With colleagues at Aston, Sue Garton and Anne Burns, she carried out a global research project titled Investigating Global Practices in Teaching English to Young Learners which led to the production of a book of language learning activities called Crazy Animals and Other Activities for Teaching English to Young Learners. She is currently working on a project investigating native-speaker teacher projects. Sue Garton is a Senior Lecturer in TESOL and Director of Postgraduate Programmes in English at Aston University. She worked for many years as an English language teacher in Italy before joining Aston as a teacher educator on distance learning TESOL programmes. As well as leading the British Council funded project on investigating global practices in teaching English to young learners, she has also worked on two other British Council projects, one looking at the transition from primary to secondary school and the other, led by Fiona Copland, on investigating native-speaker teacher schemes. They are editors of the ELT Journal Special Issue on “Teaching English to young learners.“

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Student teacher in China by Rex Pe. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Children learning English: an educational revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEducation and crime over the life cycleA revolution in trauma patient careTransforming conflict into peace

Related StoriesEducation and crime over the life cycleA revolution in trauma patient careTransforming conflict into peace

The British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part one)

Fifty years ago, a wave of British performers began showing up on The Ed Sullivan Show following the dramatic and game-changing appearances by The Beatles. That spring, a number of “beat” groups made the transatlantic leap and scored hits on American charts prompting many pop pundits to declare (not for the last time) that the Beatles’ fifteen-minutes of fame had elapsed. The first pretenders to the throne were London’s The Dave Clark Five with “Glad All Over” (sung and written by organist Mike Smith with Dave Clark), which anticipated the many other British pop records that would find a place on American charts in the mid sixties. Soon, Liverpudlian performers The Searchers (“Needles and Pins”), Gerry and the Pacemakers (“Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying”), and Billy J. Kramer (“Bad to Me”) followed fellow Merseysiders The Beatles and debuted on the Sullivan’s Sunday-night show, even as other American networks scrambled to get their piece of the British pop pie.

Publicity photo of The Dave Clark Five from their cameo performing appearance in the US film Get Yourself a College Girl. 27 November 1964. (c) MGM. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Over the course of that year, the success of acts like these changed both American impressions of British music and, importantly, British musicians’ attitudes about themselves. After an era of economic hardship and the occasional geopolitical embarrassment (e.g., the Suez Crisis of 1956), Britain came out of its postwar cultural funk to the soundtrack of pop music. At least two interrelated trends in this music emerged. First, British artists followed the long-established practice of white performers covering music created by African Americans and, second, they began to explore their own versions of what those traditions might sound like. Often, their approach was to take material previously performed acoustically and reinterpret it with electric guitars and keyboards accompanied by drums. They also applied production forces that had not been available to the original performers. Ultimately, British producers, songwriters, and musicians began to find the confidence—sometimes tinged with arrogance—that they could compete with Americans.

“House of the Rising Sun.” This traditional ballad (collector Alan Lomax had recorded an Appalachian version in the thirties) about a life gone wrong in New Orleans had been included on Bob Dylan’s eponymous first album. The Animals from Newcastle had already extracted and interpreted a song that appears on that album for British charts (“Baby Let Me Take You Home”), applying blues-rock aesthetics to a folk ballad. In a way, The Animals’ version of “House of the Rising Sun” was an early example of folk rock.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Guitarist Hilton Valentine and keyboardist Alan Price found ways to update and electrify the instrumental accompaniment of “House of the Rising Sun,” and Eric Burdon gave it a convincing and ultimately defining interpretation. The session unfolded at the unglamorous hour of eight AM after the band had traveled overnight from a gig in Liverpool, arriving at Kingsway Studios (opposite the Holborn Underground station) tired, but excited to be recording again. The band ran through the arrangement they had been playing in clubs and did two takes; but the second proved unnecessary. Mickie Most, the artist-and-repertoire manager on the session, knew he had a hit. Most later told Spencer Leigh, “Everything was in the right place, the planets were in the right place, the stars were in the right place and the wind was blowing in the right direction. It only took 15 minutes to make.”

Most’s role in the success of mid-sixties British rock and pop cannot be overstated. He would produce recordings by Herman’s Hermits, the Nashville Teens, Donovan, the Yardbirds, and many others. In the case of “House of the Rising Sun,” Most made the unconventional call to press all 4 minutes and 28 seconds of the recording. The combination of microgroove technology and vinyl allowed for longer playing times and a cleaner sound from a 45 rpm disc, even if most singles still followed the industry norm of 2:30 established by 78 rpm shellac discs. Most concluded that, if the recording and the performance were good, the length would not matter. He was proved right, even if MGM (the American distributor) would break the recording up into two parts for radio play. Released on June 19th, the record would hit number 1 on British charts in July 1964 and soon proved successful on American charts as well such that the Animals would debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in October with a hit.

“Doo Wah Diddy Diddy.” Named after South African keyboardist Manfred Lubowitz’s stage persona, the London band Manfred Mann got their break when asked to write theme music for the popular ITV television show, Ready, Steady, Go! EMI artist-and-repertoire manager John Burgess had signed them and “5, 4, 3, 2, 1” — their second release — had become a hit, albeit one that derived its success through its association with a television show. Their self-penned follow-up—“Hubble Bubble (Toil and Trouble)”—rose to a respectable #11 on UK charts, but they hoped for a piece of the transatlantic prize that The Beatles, The Dave Clark Five, and others were enjoying. As with many British performers at the time, the band and their producer decided to cover a tune that had already been released by an American singing group.

Written by Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich in New York, The Exciters’ version of “Do Wah Diddy” featured a very basic instrumental backing and had been a regional success; but it had been unable to capture a national market. Indeed, recordings by African Americans often found release only on small independent labels that lacked national distribution and promotion structures. Burgess would have guessed that his band could give it a different spin and, with the current hunger for British acts in the US and parent company EMI’s growing clout, a good promotion and distribution arrangement would ensure success.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Paul Jones gives a constrained performance, his singing style featuring a much more constricted and nasal quality when compared to the original’s open-throated joyfulness. Burgess with Norman Smith (who also served as the balance engineer on Beatles recordings in this era) capture a slightly more elaborate instrumental performance that included timpani and Mann’s electronic keyboard prominently in the mix. More importantly, Smith’s soundscape for the recording adds a depth that was lacking in the original production by the Exciters. “Doo Wah Diddy Diddy” would not be the band’s last American hit, but it would be their biggest.

“It’s All Over Now.” The Rolling Stones had had hits in the UK with a covers of Chuck Berry’s “Come On,” Lennon and McCartney’s “I Wanna Be Your Man,” and Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away”; but success had largely evaded them in the US in the first half of 1964. The summer had not bode well for the Rolling Stones, with The Daily Mirror at the end of May describing them as the “ugliest group in Britain.” But manager Andrew Oldham, if nothing else, had ambitious plans for the band.

In anticipation of their short inaugural American tour, he released one of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards’ earliest attempts at songwriting (the poppish “Tell Me,” which the songwriters had intended only as a demo) in the US to very modest regional success, but they had yet to get to the number-one spot in either the UK or the US. Once the two-week American tour began in June 1964, they played to half-empty houses and an indifferent press. If the Stones were on the road to success, it was beginning to look unpleasant.

When the tour stopped in Chicago, Oldham arranged for them to record at the studios for Chess Records. American legends who loomed large in the band’s imagination had recorded here: Chuck Berry, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, and others had all spent time at 2120 South Michigan Avenue. With Ron Malo selecting and positioning microphones before setting levels, The Stones felt they were tapping into history, while manager Andrew Oldham understood a good marketing opportunity when he saw one.

One of the tunes they had heard in New York seemed like just the thing to record during this session. Bobby and Shirley Womack had written “It’s All Over Now” for Bobby’s band, the Valentinos, but again the disc had failed to achieve much success. Their version had something of Chuck Berry’s “Memphis, Tennessee” to its grove and feel, and a prominent bass line that drove the recording along provided a sense of humor and irony.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Rolling Stones sped their version up and added an arpeggiated guitar part, while Mick Jagger delivered the lyrics as an angry victim who gains vindication, a role he would develop extensively in the coming years. When released in Britain on the June 26th, it would prove to be the Stones’ first chart topper the week after “House of the Rising Sun” had occupied that spot in July.

Click here to view the embedded video.

When asked the previous year about why British teens liked The Rolling Stones’ blues and rhythm-and-blues covers, Jagger acknowledged that their audiences liked white faces better. Indeed, British artists (including The Beatles) relied heavily on music originally created in the US by either African Americans or by rural whites.

As 1964 unfolded, songwriters, musicians, music directors, recording engineers, and artist-and-repertoire managers would gain self-confidence and begin producing something more identifiably British.

Gordon R. Thompson is Professor of Music and Chair of the Department of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Gordon Thompson will be speaking at a number of Capital District venues in February. His lecture, “She Loves You: The Beatles and New York, February 1964,” will contextualize that band’s historic relationship with the Empire State. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part one) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTransparency at the FedSharks, asylum seekers, and Australian politics

Related StoriesTransparency at the FedSharks, asylum seekers, and Australian politics

Why do prison gangs exist?

On 11 April 2013, inmate Calvin Lee stabbed and beat inmate Javaughn Young to death in a Maryland prison. They were both members of the Bloods, a notorious gang active in the facility. The day before Lee killed Young, Young and an accomplice had stabbed Lee three times in the head and neck. They did so because Lee refused to accept the punishment that his gang ordered against him for breaking “gang rules.” Lee didn’t report his injuries to officials. Instead, he waited until the next day and killed Young in retribution.

While this might seem to provide evidence that gangs are inherently violent, that’s not so. The story is more complicated. Gangs enforce a variety of rules that they design to establish order. Lee violated these rules by giving his cellmate—who had a dispute with a rival gang—a knife. Many inmates would see this as encouraging violence, which gangs seek to control. The situation provides a glimpse at a major role played by prison gangs. They don’t form to promote chaos, but to limit spontaneous acts of violence.

Many people are surprised to learn about the extent to which gangs regulate inmate life. Not only do many inmates feel they must join a gang, but gangs even issue written rules about appropriate social conduct. These include who you may eat lunch with, which shower to use, who may cut your hair, and where and when violence is acceptable. One gang gives new inmates a written list of 28 rules to follow. Many gangs even require new inmates to provide a letter of introduction from gang members at other prisons. Moreover, gangs also encourage cooperation within their group by relying on elaborate written constitutions. These often include elections, checks and balances, and impeachment procedures.

Fence and lights. © JordiDelgado via iStockphoto.

Besides setting rules, prison gangs promote social order by adjudicating conflict. Inmates can’t turn to officials to provide this when dealing in illicit goods and services. An inmate can’t rely on a prison warden to resolve a dispute over the quantity or quality of heroin. They can’t turn to officials if someone steals their marijuana stash.

In short, prison gangs form to provide extralegal governance. They enforce property rights and promote trade when formal governance mechanisms don’t. The provide law for the outlaws.

Yet, gangs’ dominance today stands in stark contrast with the historical record. In California, the prison system existed for more than a century before prison gangs emerged. If gangs are so important today, then why didn’t they exist for more than 100 years?

A major cause of the growth of prison gangs is the unprecedented growth in the prison population in the last 40 years. The United States locks up a larger number and proportion of its residents than any other country. This amounts to about 2.2 million people (707 out of every 100,000 residents). With such large prison populations, officials can’t provide all the governance that inmates’ desire. Mass incarceration thus creates fertile conditions for the rise of organized prison gangs.

David Skarbek is a Lecturer in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London. He is the author of The Social Order of the Underworld: How Prison Gangs Govern the American Penal System, which is available on Oxford Scholarship Online. Read the introductory chapter ‘Governance Institutions and the Prison Community’ for free for a limited time.

Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO) is a vast and rapidly-expanding research library, and has grown to be one of the leading academic research resources in the world. Oxford Scholarship Online offers full-text access to scholarly works from key disciplines in the humanities, social sciences, science, medicine, and law, providing quick and easy access to award-winning Oxford University Press scholarship.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why do prison gangs exist? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA decade of change: producing books in a digital worldEducation and crime over the life cycleElectronic publications in a Mexican university

Related StoriesA decade of change: producing books in a digital worldEducation and crime over the life cycleElectronic publications in a Mexican university

Transparency at the Fed

By Richard S. Grossman

As an early-stage graduate student in the 1980s, I took a summer off from academia to work at an investment bank. One of my most eye-opening experiences was discovering just how much effort Wall Street devoted to “Fed watching”, that is, trying to figure out the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy plans.

If you spend any time following the financial news today, you will not find that surprising. Economic growth, inflation, stock market returns, and exchange rates, among many other things, depend crucially on the course of monetary policy. Consequently, speculation about monetary policy frequently dominates the financial headlines.

Back in the 1980s, the life of a Fed watcher was more challenging: not only were the Fed’s future actions unknown, its current actions were also something of a mystery.

You read that right. Thirty years ago, not only did the Fed not tell you where monetary policy was going but, aside from vague statements, it did not say much about where it was either.

Given that many of the world’s central banks were established as private, profit-making institutions with little public responsibility, and even less public accountability, it is unremarkable that central bankers became accustomed to conducting their business behind closed doors. Montagu Norman, the governor of the Bank of England between 1920 and 1944 was famous for the measures he would take to avoid of the press. He adopted cloak and dagger methods, going so far as to travel under an assumed name, to avoid drawing unwanted attention to himself.

The Federal Reserve may well have learned a thing or two from Norman during its early years. The Fed’s monetary policymaking body, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), was created under the Banking Act of 1935. For the first three decades of its existence, it published brief summaries of its policy actions only in the Fed’s annual report. Thus, policy decisions might not become public for as long as a year after they were made.

Limited movements toward greater transparency began in the 1960s. By the mid-1960s, policy actions were published 90 days after the meetings in which they were taken; by the mid-1970s, the lag was reduced to approximately 45 days.

Since the mid-1990s, the increase in transparency at the Fed has accelerated. The lag time for the release of policy actions has been reduced to about three weeks. In addition, minutes of the discussions leading to policy actions are also released, giving Fed watchers additional insight into the reasoning behind the policy.

More recently, FOMC publicly announces its target for the Federal Funds rate, a key monetary policy tool, and explains its reasoning for the particular policy course chosen. Since 2007, the FOMC minutes include the numerical forecasts generated by the Federal Reserve’s staff economists. And, in a move that no doubt would have appalled Montagu Norman, since 2011 the Federal Reserve chair has held regular press conferences to explain its most recent policy actions.

The Fed is not alone in its move to become more transparent. The European Central Bank, in particular, has made transparency a stated goal of its monetary policy operations. The Bank of Japan and Bank of England have made similar noises, although exactly how far individual central banks can, or should, go in the direction of transparency is still very much debated.

Despite disagreements over how much transparency is desirable, it is clear that the steps taken by the Fed have been positive ones. Rather than making the public and financial professionals waste time trying to figure out what the central bank plans to do—which, back in the 1980s took a lot of time and effort and often led to incorrect guesses—the Fed just tells us. This make monetary policy more certain and, therefore, more effective.

Greater transparency also reduces uncertainty and the risk of violent market fluctuations based on incorrect expectations of what the Fed will do. Transparency makes Fed policy more credible and, at the same time, pressures the Fed to adhere to its stated policy. And when circumstances force the Fed to deviate from the stated policy or undertake extraordinary measures, as it has done in the wake of the financial crisis, it allows it to do so with a minimum of disruption to financial markets.

Montagu Norman is no doubt spinning in his grave. But increased transparency has made us all better off.

Richard S. Grossman is a Professor of Economics at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, USA and a visiting scholar at Harvard University’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science. His most recent book is WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Federal Reserve, Washington, by Rdsmith4. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) European Central Bank, by Eric Chan. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Transparency at the Fed appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe long journey to StonewallThe danger of ideologyIs Islamic history in danger of becoming irrelevant?

Related StoriesThe long journey to StonewallThe danger of ideologyIs Islamic history in danger of becoming irrelevant?

Sharks, asylum seekers, and Australian politics

By Matthew Flinders

We all know that the sea is a dangerous place and should be treated with respect but it seems that Australian politicians have taken things a step (possibly even a leap) further. From sharks to asylum seekers the political response appears way out of line with the scale of the risk.

In the United Kingdom the name Matthew Flinders will rarely generate even a glint of recognition, whereas in Australia Captain Matthew Flinders (1774-1814) is (almost) a household name. My namesake was not only the intrepid explorer who first circumnavigated and mapped the continent of Australia but he is also a distant relative whose name I carry with great pride. But having spent the past month acquainting myself with Australian politics I can’t help wonder how my ancestor would have felt about what has become of the country he did so much to put on the map.

The media feeding frenzy and the political response surrounding shark attacks in Western Australia provides a case in point. You are more likely to be killed by a bee sting than to be killed by a shark attack while swimming in the sea off Perth or any of Western Australia’s wonderful beaches. Hundreds of thousands of people enjoy the sea and coastline every weekend but what the media defined as ‘a spate’ of fatal shark attacks (seven to be exact) in between 2010-2013 led the state government to implement no less than 72 baited drum lines along the coast. Australia’s Federal Environment Minister, Greg Hunt, granted the Western Australian Government a temporary exemption from national environment laws protecting great white sharks, to allow the otherwise illegal acts of harming or killing the species. The result of the media feeding frenzy has been the slow death of a large number of sharks. The problem is that of the 173 sharks caught in the first four months none were Great Whites and the vast majority were Tiger Sharks – a species that has not been responsible for a fatal shark attack for decades.

The public continues to surf and swim, huge protests have been held against the shark cull and yet the Premier of Western Australia, Colin Barnett, insists that it is the public reaction against the cull that is ‘ludicrous and extreme’ and that it will remain in place for two years.

If the political approach to sharks appears somewhat harsh then the approach to asylum seekers appears equally unforgiving. At one level the Abbott government’s ‘Stop the Boats’ policy has been a success. The end of July witnessed the first group of asylum seekers to reach the Australian mainland for seven months. In the same period last year over 17,000 people in around 200 boats made the treacherous journey across the ocean in order to claim asylum in Australia. ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’ has therefore ‘solved’ a political problem that many people believe simply never existed. The solution – as far as one exists – is actually a policy of ‘offshore processing’ that uses naval intervention to direct boats to bureaucratic processing plants on Manus, Nauru, or Christmas Island. Like modern day Robinson Crusoe, thousands of asylum seekers find themselves marooned on the most remote outposts of civilization. But then again – out of sight is out of mind.

The 157 people (including around fifty children) who made it to the mainland last week exemplify the harsh treatment that forms the cornerstone of the current approach. After spending nearly a month at sea on an Australian customs vessel they were briefly flown to the remote Curtin Detention Centre but when the asylum seekers refused to be interviewed by Indian officials they were promptly dispatched to the island of Nauru and its troubled detention centre (riots, suicides, self-mutilation, etc.). Those granted asylum will be resettled permanently on Nauru while those refused will be sent back to Sri Lanka (the country that most of the asylum seekers were originally fleeing via India). Why does the government insist on this approach? Could it be the media rather than the public that are driving political decision-making? A recent report by the Australian Institute of Family Studies found that the vast majority of refugees feel welcomed by the Australian public but rejected by the Australian political institutions. How can this mismatch be explained? The economy is booming and urgently requires flexible labor, the asylum seekers want to work and embed themselves in communities; the country is vast and can hardly highlight over-population as the root of the problem.

There is an almost palpable fear of a certain type of ‘foreigner’ within the Australian political culture. Under this worldview the ocean is a human playground that foreign species (i.e. sharks) should not be allowed to visit. The world is changing as human flows become more fluid and fast-paced – no borders are really sovereign any more. And yet in Australia the political system remains wedded to ‘keeping the migration floodgates closed’, apparently unaware of just how cruel and unforgiving this makes Australia look to the rest of the world. What would Captain Matthew Flinders think about this state of affairs almost exactly 200 years after his death?

From sharks to asylum seekers Australian politics seems ‘all at sea’.

Matthew Flinders is Founding Director of the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics at the University of Sheffield and also

Visiting Distinguished Professor in Governance and Public Policy at Murdoch University, Western Australia. He is also Chair of the Political Studies Association of the United Kingdom and the author of Defending Politics (2012). Matthew is giving a public lecture entitled ‘The DisUnited Kingdom: The Scottish Independence Referendum and the Future of the United Kingdom’ on Monday 25 August. The lecture takes place at the Constitutional Centre of Western Australia at 6pm BST.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Great white shark, by Terry Goss. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Sharks, asylum seekers, and Australian politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs Islamic history in danger of becoming irrelevant?Five myths about the “surge” of Central American immigrant minorsDo we have too much democracy?

Related StoriesIs Islamic history in danger of becoming irrelevant?Five myths about the “surge” of Central American immigrant minorsDo we have too much democracy?

August 5, 2014

How threatened are we by Ebola virus?

By Peter C. Doherty

The Ebola outbreak affecting Guinea, Sierra Leone, Nigeria and now Liberia is the worst since this disease was first discovered more than 30 years back. Between 1976 and 2013 there were less than 1,000 known infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and prevention (CDC), March to 23 July 2014 saw 1201 likely cases and 672 deaths. The ongoing situation for these four West African countries is extremely dangerous, and there are fears that it could spread more widely in Africa. The relatively few intensive care units are being overwhelmed and the infection rate is likely being exacerbated by the fact that some who become ill are, on hearing that there is no specific treatment, electing to die at home surrounded by their family. The big danger is that very sick patients bleed, and body fluids and blood are extremely infectious.

American Patrick Sawyer, who was caring for his ill sister in Nigeria, has died of the disease. Working with the Christian AID Agency Samaritan’s Pulse in Monrovia, Dr Kent Brantly from Texas and Nancy Writebol from North Carolina are thought to have been infected following contact with a local staff member. Both are symptomatic but stable as I write this (July 31).

Ebola cases are classically handled by isolation, providing basic fluid support, and “barrier nursing”. Ideally, that means doctors and nurses wear disposable gowns, quality facemasks, eye protection and (double) latex gloves. That’s why it is so dangerous for patients to be cared for at home. And, even when professionals are involved, the highest incidence of infection is normally in health care workers. A number of doctors have died in the current outbreak. If there’s any suspicion that travelers returning from Africa may be infected, it is a relatively straightforward matter in wealthy, well-organized countries like the USA to institute appropriate isolation, nursing, and control. That’s why the CDC believes that the threat to North America is minimal. As for so many issues, the problem in Africa is exacerbated by poverty and the social disruption that goes with a lack of basic resources.

The fight against Ebola in West Africa… 4 months after the first case of Ebola was confirmed in Guinea, more than 1200 people have been infected across 3 West African countries. This biggest Ebola outbreak ever recorded requires an intensification of efforts to avoid it from spreading further and claiming many more lives. Photo credits: ©EC/ECHO/Jean-Louis Mosser. EU Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection. CC BY-ND 2.0 via European Commission DG ECHO Flickr.

Given that this disease is not a constant problem for humans, where does it hide out? Fruit bats are thought to be the natural and asymptomatic reservoir, though, unlike the hideous and completely unrelated Hendra and Nipah viruses that have caused somewhat similar symptoms in Australia and South East Asia, there is no Ebola virus in bats from those regions. And, while Hendra and Nipah are lethal for horses and pigs respectively, Ebola is killing off the great apes including our close and endangered primate relatives, the Chimpanzees and Gorillas. The few human Hendra infections have been contracted from sick horses that were, in turn, infected from fruit bats. An “index” (first contact) human Ebola case could result from exposure to bat droppings, or from killing wild primates for “bush meat” a practice that is, again, exacerbated by poverty. And, unlike Hendra, Ebola is known to spread from person to person.

The early Ebola symptoms of nausea, fever, headaches, vomiting, diarrhea, and general malaise are not that different from those characteristic of a number of virus infections, including severe influenza. But Ebola progresses to cause the breakdown of blood vessel walls and extensive bleeding. Also, unlike the fast developing influenza, the Ebola incubation period can be as long as two to three weeks, which means that there must be a relatively long quarantine period for suspected contacts. Fortunately, and unlike influenza and the hideous (fictional) bat-origin pathogen depicted in the recent movie Contagion, Ebola is, in the absence of exposure to contaminated body fluids, not all that infectious. Unlike most such Hollywood accounts, Contagion is relatively realistic and describes how government public health laboratories like the CDC operate. It’s worth seeing, and has been described as “the thinking person’s horror movie.”

Along with comparable EEC agencies and the WHO, the CDC currently has about 20 people “on the ground” in West Africa. Other support is being provided by organizations like Doctors Without Borders, the International Red Cross, and so forth. At this stage, there are no antiviral drugs available and no vaccine, though there are active research programs in several institutions, including the US NIH Vaccine Research Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Though there is no product currently available, it would be a big plus if all African healthcare workers could be vaccinated against Ebola. Apart from develop specific “small molecule” drugs, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that bind to proteins on the surface of the virus may be useful for emergency treatment and to give those in contact “passive” protection for three or four weeks. Such “miraculous mAbs” can now be developed and produced quickly, though they are very expensive.

What is being done? Neighboring African countries are closing their borders. International agencies and governments are providing more professionals and other resources to help with treatment and tracking cases and contacts. Global companies have been withdrawing their workers and all nations are maintaining a close watch on air travelers who are arriving from, or have recently been in, these afflicted nations.

What is this Ebola catastrophe telling us? In these days of global cost-cutting, we must keep our National and State Public Health Services strong and maintain the funding for UN Agencies like the OIE, the WHO, and the FAO. High security laboratories (BSL4) at the CDC, the NIH and so forth are a global resource, and their continued support along with the training and resourcing of the courageous, dedicated physicians and researchers who work with these very dangerous pathogens, is essential. Humanity is constantly challenged by novel, zoonotic viruses like Ebola, Hendra, Nipah, Sin Nombre, SARS, and MERS that emerge out of wildlife reservoirs, with the likelihood of such events being increased by extensive forest clearing, ever increasing population size and rapid air travel. We must be indefatigably watchful and prepared. Throughout history, nature is our worst bioterrorist.

Peter C. Doherty has appointments at the University of Melbourne, Australia, and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis. He is the 2013 author of Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know, which looks at the world of pandemic viruses and explains how infections, vaccines and monoclonal antibodies work . He shared the 1996 Nobel Prize for Physisology or Medicine for his discoveries concerning “The Cellular Immune Defense”.

What Everyone Needs to Know (WENTK) series offers a balanced and authoritative primer on complex current event issues and countries. Written by leading authorities in their given fields, in a concise question-and-answer format, inquiring minds soon learn essential knowledge to engage with the issues that matter today.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How threatened are we by Ebola virus? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLimiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemicThe long journey to StonewallIs Islamic history in danger of becoming irrelevant?

Related StoriesLimiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemicThe long journey to StonewallIs Islamic history in danger of becoming irrelevant?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers