Oxford University Press's Blog, page 777

August 8, 2014

Oral history, historical memory, and social change in West Mount Airy

There are many exciting things coming down the Oral History Review pipeline, including OHR volume 41, issue 2, the Oral History Association annual meeting, and a new staff member. But before we get to all of that, I want to take one last opportunity to celebrate OHR volume 41, issue 1 — specifically, Abigail Perkiss’ “Reclaiming the Past: Oral History and the Legacy of Integration in West Mount Airy, Philadelphia.” In this article, Abigail investigates an oral history project launched in her hometown in the 1990s, which sought to resolve contemporary tensions by collecting stories about the area’s experience with racial integration in the 1950s. Through this intriguing local history, Abigail digs into the connection between oral history, historical memory, and social change.

Abigail Perkiss. Photo credit: Laurel Harrish Photography

If that weren’t enough to whet your academic appetite, the article also went live the same week her first daughter, Zoe, was born.

How awesome is that?

But back to business. Earlier this month I chatted with Abigail about the article and the many other projects she has had in the works this year. So, please enjoy this quick interview and her article, which is currently available to all.

How did you become interested in oral history?

I’ve been gathering people’s stories in informal ways for as long as I can remember, and as an undergraduate sociology major at Bryn Mawr College, my interests began to coalesce around the intersection of storytelling and social change. I took classes in ethnography, worked as a PA on a few documentary projects, and interned at a documentary theater company. All throughout, I had the opportunity to develop and hone my skills as an interviewer.

I began taking history classes my junior year, and through that I started to think about the idea of oral history in a more intentional way. I focused my research around oral history, which culminated in my senior thesis, in which I interviewed several folksingers to examine the role of protest music in creating a collective memory of the Vietnam War, and how that memory was impacting the way Americans understood the war in Iraq. A flawed project, but pretty amazing to speak with people like Pete Seeger, Janis Ian, and Mary Travers!

After college, I studied at the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies in Portland, Maine, and when I began my doctoral studies at Temple University, I knew that I wanted to pursue research that would allow me to use oral history as one of the primary methodological approaches.

What sparked your interest in the Mount Airy project?

When I started my graduate work at Temple, I was pursuing a joint JD/PhD in US history. I knew I wanted to do something in the fields of urban history and racial justice, and I kept coming back to the Mount Airy integration project. I actually grew up in West Mount Airy, and even as a kid, I was very much aware of the lore of the neighborhood integration project. There was a real sense that the community was unique, special.

I knew that there had to be more to the utopian vision that was so pervasive in public conversations about the neighborhood, and I realized that by contextualizing the community’s efforts within the broader history of racial justice and urban space in the mid-twentieth century, I would be able to look critically about the concept and process of interracial living. I could also use oral history as a key piece of my research.

Your article focuses on an 1990s oral history project led by a local organization, the West Mount Airy Neighbors. Why did you choose to augment the interviews they collected with your own?

The 1993 oral history project was a wonderful resource for my book project (from which this article comes); but for my purposes, it was also incomplete. Interviewers focused largely on the early years of integration, so I wasn’t able to get much of a sense of the historical evolution of the efforts. The questions were also framed according to a very particular set of goals that project coordinators sought to achieve — as I argue, they hoped to galvanize community cohesion in the 1990s and to situate the local community organization at the center of contemporary change.

So, while the interviews were quite telling about the West Mount Airy Neighbors’ efforts to maintain institutional control in the neighborhood, they weren’t always useful for me in getting at some of the other questions I was trying to answer: about the meaning of integration for various groups in the community, about the racial politics that emerged, about the perception of Mount Airy in the city at large. To get at those questions, it was important for me to conduct additional interviews.

Is there anything you couldn’t address in the article that you’d like to share here?

As I alluded to above, it is part of a larger book project on postwar residential integration, Making Good Neighbors: Civil Rights, Liberalism, and Integration in Postwar Philadelphia (Cornell University Press, 2014). There, I look at the broader process of integrating and the challenges that emerged as the integration efforts coalesced and evolved over the decades. Much of the research for the book came from archival collections, but the oral histories from the 1990s, and the ones I collected, were instrumental in fleshing out the story and humanizing what could otherwise have been a rather institutional history of the West Mount Airy Neighbors organization.

Are you working on any projects the OHR community should know about?

I’ve spent the past 18 months directing an oral history project on Hurricane Sandy, Staring out to Sea, which came about through a collaboration with Oral History in the Mid-Atlantic Region (remember them?) and a seminar I taught in Spring 2013. That semester, I worked intensively with six undergraduates, studying the practice of oral history and setting up the project’s parameters. The students developed the themes and questions, recruited participants, conducted and transcribed interviews. They then processed and analyzed their findings, looking specifically at issues of race, power and representation in the wake of the storm.

In addition to blogging about their experience, the students presented their work at the 2013 OHMAR and OHA meetings. You can read a bit more about that and the project in Perspectives on History. This fall, I’ll be working with Professor Dan Royles and his digital humanities students to index the interviews we’ve collected and develop an online digital library for the project. I’ll also be attending to the OHA annual meeting this year to discuss the project’s transformative impact on the students themselves.

Excellent! I look forward to seeing you (and the rest of our readers) in Madison this October.

Caitlin Tyler-Richards is the editorial/media assistant at the Oral History Review. When not sharing profound witticisms at @OralHistReview, Caitlin pursues a PhD in African History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research revolves around the intersection of West African history, literature and identity construction, as well as a fledgling interest in digital humanities. Before coming to Madison, Caitlin worked for the Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown University.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow their latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oral history, historical memory, and social change in West Mount Airy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRe-thinking the role of the regional oral history organizationA call for oral history bloggersSchizophrenia and oral history

Related StoriesRe-thinking the role of the regional oral history organizationA call for oral history bloggersSchizophrenia and oral history

Youth and the new media: what next?

Now that the Internet has been with us for over 25 years, what are we to make of all the concerns about how this new medium is affecting us, especially the young digital natives who know more about how to maneuver in this space than most adults?

Although it is true that various novel media platforms have invaded households in the United States, many researchers still focus on the harms that the “old” media of television and movies still have on youth. The effects of advertising on promoting the obesity epidemic highlight how so much of those messages are directed to children and adolescents. Jennifer Harris noted that children ages 2 to 11 get nearly 13 food and beverage ads every day while watching TV, and adolescents get even more. Needless to say, many of these ads promote high-calorie, low-nutrition foods. Beer is still heavily promoted on TV with little concern about who is watching, and sexual messages are rampant across both TV and movie screens. None of this is new, but the fact that these influences remain so dominant today despite the powerful presence of new media is testament enough that “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

When it comes to the new media, researchers are more balanced. Sonia Livingston from the UK reported on a massive study done in Europe that found a lot of variation in how countries are dealing with the potential harms on children. But when all was said and done, she concluded that the risks there were no more prevalent than those that kids have confronted in their daily lives offline. What has changed there is the talk about the “risks,” without much delving into whether those risks actually materialize into harms. Many kids are exposed to hurtful content in this new digital space, but many also learned how to cope with them.

2013 E3 – XBOX ONE Killer Instinct B. Uploaded by – EMR -. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The perhaps most contentious of the new media influences is the emergence of video gaming, either via the Internet or on home consoles. The new DSM-5, which identifies mental disorders for psychiatrists, suggests that these gaming activities can become addictive. Research summarized by Sara Prot and colleagues suggests that about 8% of young people exhibit symptoms of this potential disorder. At the same time, we still don’t know whether gaming leads to the symptoms or is just a manifestation of other problems that would emerge anyway.

Aside from the potential addictive properties of video games, there is considerable concern about games that invite players to shoot and destroy imaginary attackers. Many young men play these violent video games and some of them are actually used by the military to prepare soldiers for battle. One could imagine that a young man with intense resentment toward others could see these games as a release or even worse as practice for potential harmdoing. The rise in school shootings in recent years only adds to the concern. The research reviewed by Prot is quite clear that playing the games can increase aggressive thoughts and behavior in laboratory settings. What remains contentious is how much influence this has on actual violence outside the lab.

On the positive side, other researchers have noted how much good both the old and new media can provide to educators and to health promoters. It is helpful to keep in mind that many of the concerns about the new media may merely reflect the age old wariness that adults have displayed regarding the role of media in their children’s behavior. In a recent review of the effects of Internet use on the brain, Kathryn Mills of University College London pointed out that even Socrates was skeptical of children learning to write because it would reduce their need to develop memory skills. Here again, the more things change, the more they remain the same.

Daniel Romer is the Director of the Adolescent Communication and Health Institutes of the Annenberg Public Policy Center. He directs research on the social and cognitive development of adolescents with particular focus on the promotion of mental and behavioral health. His research is currently funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. He regularly serves on review panels for NIH and NSF and consults on federal panels regarding media guidelines for coverage of adolescent mental health problems, such as suicide and bullying. He is the author of Media and the Well-Being of Children and Adolescents.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Youth and the new media: what next? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central AmericaWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesWhy hope still matters

Related StoriesSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central AmericaWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesWhy hope still matters

Why hope still matters

Someone asked me at a recent book talk why I chose to write about hope and children in poverty. They asked whether it was frivolous to write about such a topic at a time when children are experiencing the challenges associated with poverty and economic disadvantage at high rates. As I thought about that question, I began to reflect on the stories of people I know and families I’ve worked with who, despite the challenges they experienced, were managing their lives successfully. I also reflected on popular figures who shared stories in the media about the ways in which they overcame early adversity in their lives.

As I reflected on these stories, it occurred to me that a common theme among these individuals was hope. I began to see the various ways in which hope is a highly influential and motivating force in their lives. This kind of hope is not passive—it is not merely wishing for a better life, but it is active. It involves thinking, planning, and acting on those thoughts and plans to achieve desired outcomes. It is the driving force that keeps us moving despite the adversity and allows us to adapt and to be resilient in the midst of these circumstances. In reflecting on these themes, I decided that I wanted to tell these stories and to link the stories with theoretical frameworks that help illuminate why I believe hope is so important. Most of the theories and ideas I discuss are well known to those of us who study children and families. However, it occurred to me that practitioners and policymakers may not be so familiar with these ideas and may find them useful in planning their work with children and families. My goal is to foster understandings of hope and resilience in practical terms so that together researchers, practitioners, and policymakers alike can help more children and families manage their circumstances and chart pathways toward well-being.

I Hope You Dance. Photo by Lauren Hammond. CC BY 2.0 via sleepyjeanie Flickr.

So when I think about a response to the question “Why focus on hope?” — I respond “Why not?” Why not focus on strengths rather than deficits? Why not focus our interventions, legislative activities, and funding priorities on processes that will motivate individuals to strive for the best outcomes for themselves and their children? In so doing, we can formulate an action agenda on behalf of children and families that first assumes they can and will succeed in rising above their circumstances.

As I learned from the families I interviewed, success means different things to different families. For some, success is being able to keep their family together—have dinner together, talk with each other, and support each other. For other families, success means being able to be a good parent– to go to bed at night realizing that you’ve provided for your child emotionally, spiritually as well as materially, and that by doing so, your child might have an even better opportunity than you did to achieve success. These individuals are truly courageous. They have overcome many obstacles and are striving to continue along that path. There are countless other courageous individuals who may never have the opportunity to tell their stories or to have their experiences validated with concepts and theories I discuss from the psychological literature. I hope this volume will represent their lives too. I challenge those of us who work with children and families and who advocate for or legislate on their behalf, to have the courage to “ hope” and to allow that hope to be a motivating and unrelenting force in our efforts to foster resilience and well-being in these families.

Dr. Valerie Maholmes has devoted her career to studying factors that affect child developmental outcomes. Low-income minority children have been a particular focus of her research, practical, and civic work. She has been a faculty member at the Yale Child Study Center in the Yale School of Medicine where she held the Irving B. Harris Assistant Professorship of Child Psychiatry, an endowed professorial chair. She is the author of Fostering Resilience and Well-Being in Children and Families in Poverty.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why hope still matters appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central AmericaWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesMichael Jackson, 10,000 hours, and the roots of creative genius

Related StoriesSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central AmericaWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesMichael Jackson, 10,000 hours, and the roots of creative genius

Michael Jackson, 10,000 hours, and the roots of creative genius

That any person could become an expert in something if they simply spend about 3 hours per day for ten years learning it is an appealing concept. This idea, first championed by Ericsson and brought to prominence by Gladwell, has now taken root in the popular media. It attempts to discuss these differences in terms of the environment. The idea is that practice with the purpose of constantly gathering feedback and improving can lead any person to become an expert. If becoming an expert requires 10,000 hours, does a prodigy need 20,000.

Lets consider, Michael Jackson, as an example of a prodigy. He grew up in a musical family in Gary, Indiana just outside Chicago. His father Joe played in an R&B band. All of his siblings played music in one way or another. Unlike his siblings and father, Jackson did not really play any instruments. However, he would compose songs in his head using his voice. One morning he came in and had written a song which eventually became ‘Beat It’. In the studio, he would sing each of the different parts including the various instruments. Then the producers and artists in the studio would work on putting the song together, following his arrangements.

Work in cognitive neuroscience has begun to shed light on the brain systems involved in creativity as being linked to psychometric IQ. Work by Neubauer and Fink suggests that these two different types of abilities, psychometric IQ and expertise, involve differential activity in the frontal and parietal lobes. They also appear for different types of tasks. In one study, taxi drivers were split into a high and low group depending on their performance on a paper and pencil IQ test. The results showed that both groups did equally well on familiar routes. The differences appeared between groups when they were compared on unfamiliar routes. In this condition, those with high IQs outperformed those with low IQ. So expertise can develop but the flexibility to handle new situations and improvise requires more than just practice.

Reports of Michael Jackson’s IQ are unreliable. However, he is purported to have had over 10,000 books in his reading collection and to have been an avid reader. His interviews reveal a person who was very eloquent and well spoken. And clearly he was able to integrate various different types of strands of music into interesting novel blends. If we were to lay this out across time, we have perhaps the roots of early genius. It is a person who has an unusual amount of exposure in a domain that starts at an early age. This would lead to the ability to play music very well.

Jackson came from a family filled with many successful musicians. Many were successful as recording artists. Perhaps Michael started earlier than his siblings. One conclusion we can draw from this natural experiment is that creative genius requires more than 10,000 hours. In the case of Michael Jackson, he read profusely and had very rich life experiences. He tried to meld these experiences into a blended musical genre that is uniquely his and yet distinctly resonant with known musical styles.

The kind of creativity is not restricted to prodigies like Michael Jackson. Language, our ultimate achievement as a human race, is something that no other animal species on this planet shares with us. The seeds of language exist all over the animal kingdom. There are birds that can use syntax to create elaborate songs. Chinchillas can recognize basic human speech. Higher primates can develop extensive vocabularies and use relatively sophisticated language. But only one species was able to take all of these various pieces and combine them into a much richer whole. Every human is born with the potential to develop much larger frontal lobes which interconnect with attention, motor, and sensory areas of the brain. It is in these enlarged cortical areas that we can see the roots of creative genius. So while 10,000 hours will create efficiency within restricted areas of the brain, only the use of more general purpose brain areas serve to develop true creativity.

Arturo Hernandez is currently Professor of Psychology and Director of the Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience graduate program at the University of Houston. He is the author of The Bilingual Brain. His major research interest is in the neural underpinnings of bilingual language processing and second language acquisition in children and adults. He has used a variety of neuroimaging methods as well as behavioral techniques to investigate these phenomena which have been published in a number of peer reviewed journal articles. His research is currently funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development. You can follow him on Twitter @DrAEHernandez. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Michael Jackson with the Reagans, by White House Photo Office. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Michael Jackson, 10,000 hours, and the roots of creative genius appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat do Otis Redding and Roberto Carlos have in common?Why you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Related StoriesWhat do Otis Redding and Roberto Carlos have in common?Why you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

How medical publishing can drive research and care

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a very frequent cause of harmless but unpleasant vertigo and dizziness complaints. It is caused by dislodged otoconia floating into the semicircular canals, which measure angular accelerations of the head and initiate corrective eye movements during fast head movements. Otoconia are calcium-carbonate crystals functioning as weights in the miniature acceleration sensors in the inner ear, informing us about gravity and linear accelerations. If they fall into the canals, their erratic movements produce false information of angular accelerations when the head position is changed, and then we feel dizziness.

Currently, the diagnosis of BPPV depends on the presentation of jerking eye movements (nystagmus) in the provoking positions, for example head-hanging. Nystagmus is elicited when the fluid in the semicircular canal deflects the sensory cells by deforming the cupula, a soft diaphragm at one end of the canals. During the routine clinical examination of BPPV, the patient’s head is brought into hanging position (the “Dix-Hallpike maneuver”). Should there be any otoconia in the canal, this allows them and their movements to be registered by observing the elicited eye movements.

Last year, I tried to design a table about BPPV and its different forms when different semicircular canals are involved. Filling in the table, I noticed that a form that was probably very frequent had not been satisfactorily examined and explained in literature. I wondered what happens when otoconia dislodge but do not fall into the one of the semicircular canals. This might be a frequent scenario, if, for example, the patient is upright or the dislodged debris misses the canal openings. The debris should sink to the most inferior part, which is, by chance, the cupula, the structure housing the sensory cells of one of the canals, the inferior canal. The deflection of the cupula informs the nervous system about fluid movements in the canal, thereby measuring angular accelerations. When the otoconia fall into this space and attach themselves to the cupula, thereby loading it and causing chronic, unpleasant dizziness with every head movement, they, in fact should not cause any nystagmus when the patient is moved from sitting into the head hanging position. This is because the head hanging position does not change the position of the cupula at all.

I realized that I discovered a possible mechanism for a frequent type of BPPV, with typical positional complaints but without nystagmus. This variant, although frequently encountered, has not been acknowledged so far. In theory it should be frequent, because, when dislodged in upright position (not in sleep but during daily activities), the otoconia should sink into the most inferior part of the vestibulum (which are the sensory cells of the inferior canal). This concept has been mentioned (but not explained) in literature. In a recent paper, for instance, South Korean doctors wanted to recruit a hundred patients with a diagnosis of BPPV for a study about vitamin D. During selection, 84 patients who reported a typical history suggestive of BPPV but did not exhibit nystagmus were excluded. This would mean that in the paper, 40% of patients with typical BPPV symptoms may have had complaints elicited by the mechanism described above. Currently, according to the classical criteria, in these cases, no diagnosis was possible.

Since I had not previously matched the theory against the opinion of peer-reviewers, we included this theory in a chapter with a title “Controversial issues” that was published in Otology Neurotology, the journal of the American Otological Society.

When verified by other authors, these ideas will be accepted and it will be possible to make diagnosis in cases which seem to be mysterious today. Although not so dramatic as overt BPPV with nystagmus, the patients with slight, chronic BPPV complaints feel ill enough to see a doctor and these cases may be frequent, considering the how frequent BPPV is.

Béla Büki is an ENT-specialist at Krems County Hospital, Austria. He is co-author of Vertigo and Dizziness, and his special interests include otoacoustic emissions, electrocochleography, non-invasive intracranial pressure measurements and neurotology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Vertigo 08018, by Nevit Dilmen. CC BY-SA 3.0. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How medical publishing can drive research and care appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central AmericaBoxes and paradoxesPaul Otlet, Google, Wikipedia, and cataloging the world

Related StoriesSupporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central AmericaBoxes and paradoxesPaul Otlet, Google, Wikipedia, and cataloging the world

1914: The opening campaigns

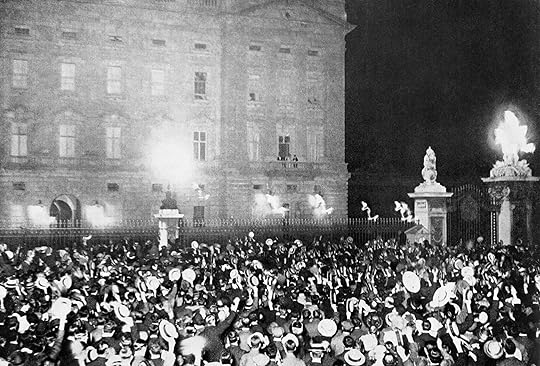

To mark the outbreak of the First World War, this week’s Very Short Introductions blog post is an extract from The First World War: A Very Short Introduction, by Michael Howard. The extract below describes the public reaction to the outbreak of war, the government propaganda in the opening months, and the reasons behind each nation going to war.

The outbreak of war was greeted with enthusiasm in the major cities of all the belligerent powers, but this urban excitement was not necessarily typical of public opinion as a whole. The mood in France in particular was one of stoical resignation – one that probably characterized all agrarian workers who were called up and had to leave their land to be cultivated by women and children. But everywhere peoples were supportive of their governments. This was no ‘limited war’ between princely states. War was now a national affair. For a century past, national self-consciousness had been inculcated by state educational programmes directed to forming loyal and obedient citizens. Indeed, as societies became increasingly secular, the concept of the Nation, with all its military panoply and heritage, acquired a quasi-religious significance. Conscription assisted this indoctrination process but was not essential to it: public opinion in Britain, where conscription was not introduced until 1916, was as keenly nationalistic as anywhere on the Continent. For thinkers saturated in Darwinian theory, war was seen as a test of ‘manhood’ such as soft urban living no longer afforded. Such ‘manhood’ was believed to be essential if nations were to be ‘fit to survive’ in a world where progress was the result, or so they believed, of competition rather than cooperation, between nations as between species. Liberal pacifism remained influential in Western democracies, but it was also widely seen, especially in Germany, as a symptom of moral decadence.

Such sophisticated belligerence made the advent of war welcome to many intellectuals, as well as to members of the old ruling classes, who accepted with enthusiasm their traditional function of leadership in war. Artists, musicians, academics, and writers vied with each other in offering their services to their governments. For artists in particular, Futurists in Italy, Cubists in France, Vorticists in Britain, Expressionists in Germany, war was seen as an aspect of the liberation from an outworn regime that they themselves had been pioneering for a decade past. Workers in urban environments looked forward to finding in it an exciting and, they hoped, a brief respite from the tedium of their everyday lives. In the democracies of Western Europe mass opinion, reinforced by government propaganda, swept along the less enthusiastic. In the less literate and developed societies further east, traditional feudal loyalty, powerfully reinforced by religious sanctions, was equally effective in mass mobilization.

Crowds outside Buckingham Palace cheer King George, Queen Mary and the Prince of Wales following the Declaration of War in August 1914. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

And it must be remembered that all governments could make out a plausible case. The Austrians were fighting for the preservation of their historic multinational empire against disintegration provoked by their old adversary Russia. The Russians were fighting for the protection of their Slav kith and kin, for the defence of their national honour, and to fulfil their obligations to their ally France. The French were fighting in self-defence against totally unprovoked aggression by their traditional enemy. The British were fighting to uphold the law of nations and to pre-empt the greatest threat they had faced from the Continent since the days of Napoleon. The Germans were fighting on behalf of their one remaining ally, and to repel a Slavic threat from the east that had joined forces with their jealous rivals in the west to stifle their rightful emergence as a World Power. These were the arguments that governments presented to their peoples. But the peoples did not have to be whipped up by government propaganda. It was in a spirit of simple patriotic duty that they joined the colours and went to war.

Writing at the end of the nineteenth century the German military writer Colmar von der Goltz had warned that any future European war would see ‘an exodus of nations’, and he was proved right. In August 1914 the armies of Europe mobilized some six million men and hurled them against their neighbours. German armies invaded France and Belgium. Russian armies invaded Germany. Austrian armies invaded Serbia and Russia. French armies attacked over the frontier into German Alsace-Lorraine. The British sent an expeditionary force to help the French, confidently expecting to reach Berlin by Christmas. Only the Italians, whose obligations under the Triple Alliance covered only a defensive war and ruled out incurring British hostility, prudently waited on events. If ‘the Allies’ (as the Franco-Russo-British alliance became generally known) won, Italy might gain the lands she claimed from Austria; if ‘the Central Powers’ (the Austro-Germans), she might win not only the contested borderlands with France, Nice and Savoy, but French possessions in North Africa to add to the Mediterranean empire she had already begun to acquire at the expense of the Turks. Italy’s policy was guided, as their Prime Minister declared with endearing frankness, by sacro egoismo.

This extract was taken from The First World War: A Very Short Introduction, by Michael Howard. The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 1914: The opening campaigns appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Tuesday, 4 August 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914

Related StoriesThe month that changed the world: Tuesday, 4 August 1914The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914The month that changed the world: Saturday, 1 August 1914

August 7, 2014

Gods and mythological creatures of the Odyssey in art

The gods and various mythological creatures — from minor gods to nymphs to monsters — play an integral role in Odysseus’s adventures. They may act as puppeteers, guiding or diverting Odysseus’s course; they may act as anchors, keeping Odysseus from journeying home; or they may act as obstacles, such as Cyclops, Scylla and Charbidis, or the Sirens. While Gods like Athena are generally looking out for Odysseus’s best interests, Aeolus, Poseidon, and Helios beg Zeus to punish Odysseus, but because his fate is to return home to Ithaca, many of the Gods simply make his journey more difficult. Below if a brief slideshow of images from Barry B. Powell’s new free verse translation of Homer’s The Odyssey depicting the god and other mythology.

Kirkê

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Kirkê is the goddess of magic, also referred to as a witch or enchantress. Odysseus’ arrival to her island is described as follows, “the house of Kirkê, made of polished stone, in an open meadow. There were wolves around it from the mountains, and lions whom Kirkê had herself enchanted by giving them potions” (10.197-199). When several of Odysseus’ men enter through her doors, she turns them into “beings with the heads of swine, and a pig’s snort and bristles and shape, but their minds remained the same” (10.225-227). However, Odysseus receives assistance from Hermes when he is given a powerful herb that wards off the effect any of Kirke’s potions. Odysseus stays with her for one year, and then decides that he must go back home to Ithaca. As mentioned previously, Kirkê tells him that he must sail to Hades, the realm of the dead, to speak with the spirit of Tiresias.

Kirkê Offering the Cup to Ulysses by John William Waterhouse. 1891. Oil on canvas. Dimensions 149 cm × 92 cm (59 in × 36 in). Gallery Oldham, Oldham.

Kalypso

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Shipwrecked from the storm that Zeus conjures up to punish him, Odysseus manages to float over to Ogygia where he encounters the nymph and beautiful goddess Kalypso with whom Odysseus embarks on a seven-year relationship with. She is a nymph, or a nature spirit, who acts as a barrier between Odysseus fulfilling his destiny and returning home to Ithaca. In Book 5, Athena says to Zeus, “he lies on an island suffering terrible pains in the halls of great Kalypso, who holds him against his will. He is not able to come to the land of his fathers” (5.12-14).

Kalypso receiving Telemachos and Mentor in the Grotto detail by William Hamilton. 18th century.

Helios

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Odysseus and his men take refuge on the island of Thrinacia (the island of the sun) during their journey. They remain there for a month, but the crew's provisions eventually run out, and Odysseus' crew members slaughter the cattle of the Sun. When the Sun god (Helios) finds out, he asks Zeus to punish Odysseus and his men. Helios demands, “If they do not pay me a suitable recompense for the cattle, I will descend into the house of Hades and shine among the dead!” (12.364-366). Zeus agrees and strikes Odysseus’ ship with lightning and kills all of Odysseus’ crew members.

Head of Helios, middle Hellenistic period. Holes on the periphery of the cranium are for inserting the metal rays of his crown. The characteristic likeness to portraits of Alexander the Great alludes to Lysippan models. Archaeological Museum of Rhodes.

Herakles

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Odysseus and Herakles meet in the Underworld, and also encounters Herakles’ daughter Megara and mother Amphitryon. Odysseus recalls seeing Herakles and says, “Herakles was like the dark night, holding his bare bow and an arrow on the string, glaring dreadfully, a man about to shoot. The baldric around his chest was awesome—a golden strap in which were worked wondrous things, bears and wild boars and lions with flashing eyes, and combats and battles and the murders of men. I would wish that the artist did not make another one like it!” (11.570-576).

Herakles crowned with a laurel wreath, wearing the lion-skin and holding a club and a bow, detail from a scene representing the gathering of the Argonauts. From an Attic red-figure calyx-krater, ca. 460–450 BC. From Orvieto (Volsinii).

Ino (Leucothea)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Shipwrecked after Poseidon sinks his ship, Odysseus encounters Ino (Leucothea) who takes pity on him. She leads him toward the land of the Phaeacians and says, “Here, take this immortal veil and tie it beneath your breast. You need not fear you will suffer anything. And when you get hold of the dry land with your hands, untie the veil and throw it into the wine-dark sea, far from land. Then turn away” (5.320-324).

Leucothea (1862), by Jean Jules Allasseur (1818-1903). South façade of the Cour Carrée in the Louvre palace, Paris.

Aiolos

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In Book 10, The Achaeans sail from the land of the Cyclops to the home of Aiolus, ruler of the winds. He gifts Odysseus with a bag containing all of the winds in order to guide Odysseus and his crew home. However, the winds escape from the bag due to Odysseus’ men believing that the bag contains gold and silver, and end up bringing Odysseus and his men back to Aiolia. Aiolos provides Odysseus with no further help from then on, as he says, “It is not right that I help or send that man on his way who is hated by the blessed gods” (10.72-73). This is to say that Aiolos judges Odysseus’ return as a bad omen.

This image is a Roman mosaic from the House of Dionysos and the Four Seasons, 3rd century AD, Roman city of Volubilis, capital of the Berber king Juba II (50 BC-24 AD) in the province of Mauretania, Morocco. The Romans loved to decorate their floors with themes taken from Greek myth, and many have survived.

Picture7

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Athena is the most influential goddess, and a catalyst for the events in the story the Odyssey. She is not only the goddess of wisdom, but also of strategy, law and justice, and inspiration among others, and is referred to consistently in the book as “flashing-eyed Athena.” At times in Homer’s epic poem, she acts as a puppeteer throughout Odysseus’ journey as she guides his movements and modifies his and her own appearance to accommodate Odysseus’ circumstances advantageously.

Marble, Roman copy from the 1st century BC/AD after a Greek original of the 4th century BC, attributed to Cephisodotos or Euphranor. Related to the bronze Piraeus Athena.

Aphrodite and Ares

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Referred to as the “godlike” visitor, Odysseus is honored during a Phaeacian celebration hosted by Nausicaä’s parents. During the ceremony, a poet named Demdokos plays a song on his lyre, “the love song of Ares and fair-crowned Aphrodite, how they first mingled in love, in secret, in the house of Hephaistos” (8.248-250).

The adultery of Ares and Aphrodite. Clad only in a gown that comes just above her pubic area, Aphrodite holds a mirror while her half-naked lover, Ares, sitting on a nearby bench, embraces her and touches her breast. The device that imprisoned them is visible as a cloth stretched above their heads. Such paintings were especially popular in Roman brothels in Pompeii. Roman fresco from Pompeii, c. AD 60.

Artemis

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Approaching the Phaeacian princess Nausicaä for the first time, Odysseus asks, “are you a goddess, or a mortal? If you are a goddess, one of those who inhabit the broad heaven, I would compare you in beauty and stature and form to Artemis, the great daughter of Zeus” (6.139-142).

Wearing an elegant dress and a band about her hair, Artemis carries a torch in her left hand and a dish for drink offerings in her right hand (phialê), not her usual attributes of bow and arrows. She is labeled POTNIAAR, “lady Artemis.” An odd animal, perhaps a young sacrificial bull, gambols at her side. Athenian white-ground lekythos, c. 460-450 BC, from Eretria.

Poseidon

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Poseidon holding a trident. Poseidon is the Greek god of the Sea, or as referred to in the epic poem, “the earth-shaker.” The god is long haired and bearded and wears a band around his head. The trident may in origin have been a thunderbolt, but it has been changed into a tuna spear. Corinthian plaque, from Penteskouphia, 550–525 BC. Musée du Louvre, CA 452

Hades

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

When Odysseus is on the witch-goddess Kirkê’s island (discussed later), she tells him that he must sail to Hades, the realm of the dead, to speak with the spirit of Tiresias. The underworld is described by Odysseus as a place where “total night is stretched over wretched mortals” (11.18-19). While we do not meet the god Hades directly, his realm is explored by Odysseus. During his time spent in the underworld, Odysseus meets many different people who he had met or been directly influenced by at different points in his life, including his former shipmate Elpenor, his mother Anticleia, and warriors such as Agamemnon, Achilles, Ajax, Minos, Orion, and Heracles.

Hades with Cerberus (Heraklion Archaeological Museum)

Hermes

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Hermes weighing souls (psychostasis). In Book 5, Hermes, messenger of the gods, is sent to tell the nymph Kalypso to allow Odysseus to leave so he can return home after several years of being detained on the island of Ogygia. Hermes is also known as the god of boundaries, and as such he is Psychopompos, or “soul-guide”: He leads the souls of the dead to the house of Hades. In a sense, Odysseus is dead, imprisoned on an island in the middle of the sea by Kalypso, the “concealer.” Here the god is shown with winged shoes (in Homer they are “immortal, golden”) and a traveler’s broad-brimmed hat, hanging behind his head from a cord. In his left hand he carries his typical wand, the caduceus, a rod entwined by two copulating snakes. In his right hand he holds a scale with two pans, in each of which is a psychê, a “breath-soul” represented as a miniature man (scarcely visible in the picture). Athenian red-figure amphora from Nola, c. 460 BC, by the Nikon Painter.

Zeus

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Zeus is the ruler of Mount Olympus and all of its inhabitants, and is referred to as “the son of Kronos, god of the dark cloud who rules over everything” in the Odyssey (13.26-27). Though he does not have a predominant role in the Odyssey, his presence is felt as he is the main consulting force of the other deities. He makes an important declaration about the notion of free will in Book 1, and goes on to point out that he sent his messenger Hermes to warn Aigisthos not to kill Agamemnon, but yet the mortal chose not to follow the advice. Zeus says, “And now he has paid the price in full,” in response to Aigisthos’ death. In other words, he believes that the gods can only intervene to a certain degree, but the mortal world has the ultimate control over their own fate.

Statue of a male deity, brought to Louis XIV and restored as a Zeus ca. 1686 by Pierre Granier, who added the arm raising the thunderbolt.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His new free verse translation of The Odyssey was published by Oxford University Press in 2014. His translation of The Iliad was published by Oxford University Press in 2013. See previous blog posts from Barry B. Powell.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Gods and mythological creatures of the Odyssey in art appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCharacters of the Odyssey in Ancient ArtTelemachos in IthacaScenes from the Odyssey in Ancient Art

Related StoriesCharacters of the Odyssey in Ancient ArtTelemachos in IthacaScenes from the Odyssey in Ancient Art

Supporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America

Since 1 October 2013, the United States has detained over 57,000 unaccompanied minors from Central America crossing the border from in an attempt to escape severe violence. Makeshift immigration shelters emerged, with emergency responders providing medical attention and care. Meanwhile, the government must now identify a response to what is now considered a humanitarian crisis, with an estimated 90,000 unaccompanied minors expected to cross the border in 2014.

Do we have a moral obligation to offer asylum or refugee status to people escaping violence or political persecution? What if they are children?

Should the children be deported to their families? If not, where will they go? Who will care for them?

Who bears the financial responsibility for meeting their needs?

The country seems split in its views. While most do not outright say these children should be returned to a country where their lives and well-being are in danger, concern remains about the country’s ability to sustain support for them physically, socially, emotionally, academically, and occupationally. In polls, some Americans say displaced families place a burden on housing, health care, and other public service industries, whereas as the majority believes they should be allowed to stay if it is unsafe for them to return home. As the debate continues, many of these children have arrived at the doors of our local schools hoping to enroll with minimal information or supports, with more anticipated to arrive as the new school year begins. Meeting their educational needs will be difficult, and according to the Department of Education, mandatory.

In May, the Federal Department of Education published Guidance on enrolling students regardless of immigration status. This guidance outlined the legal requirements concerning school districts’ responsibilities to enroll all students, regardless of immigration status. They did not include guidance in reference to provision of essential services that would lead to a successful education experience for these students. What is clear from this guidance, however, is that local school systems will be responsible for enrolling and educating the surge of students using local resources.

Immigrant and refugee students who arrive at the school house door after leaving their homes have typically experienced multiple adverse events prior to leaving and multiple adverse events during their travels. These adverse events can be traumatizing to students, not to mention navigating an unfamiliar country, sometimes with a completely unfamiliar language and low literacy, without parents or immediate family support available (resettlement stress). This often leads to serious disruptions in their access to education and their mental status upon arrival. Educators and school support personnel can mitigate some of the issues associated with these adverse events, and perhaps are among the most equipped and qualified to do so.

Many school districts and agencies have wide ranging experiences with displaced children. While the majority of children of immigrants are US-born citizens, over 15% are first generation immigrants, among which over one-third cross the border as victims of trafficking or seeking asylum. It’s safe to assume that many school districts have enrolled these students at some point. Even beyond immigration, following Hurricane Katrina, schools absorbed a high number of displaced students amidst extremely stressful conditions. Schools provide stable educational opportunities, exposure to trusting adults, an opportunity to interact with peers, and access to school employed mental health professionals. Many districts have partnered with communities to develop comprehensive supports and services to ease transitions and mitigate the effects of potentially traumatic experiences.

No matter what the circumstances that led displaced students to classrooms, there are a few strategies that can be implemented that will help in providing support to help these students learn and adapt positively to their new environment. As with many traumatized students, school personnel have to reframe the presenting problems as a result of their experiences rather than an indication of something being wrong with the child. For example, they must:

develop a structured daily routine is a foundation for support

connect students with other children of immigrants enrolled in schools (it is reasonable to expect that most schools in the country have displaced or immigrant families already in the community)

recognize and build on strengths, such as strong family ties, optimism, strong socio-centric values, resilience, and cultural diversity

acknowledge potential stigma associated with mental health supports

engage family or extended family as much as possible.

Providing these supports and other strategies require a coordinated effort between all school staff, including teachers, administrators, and specialized instructional support personnel. Doing so goes beyond a legal mandate from the Department of Education; it’s a moral and ethical obligation to provide the best available supports to all children, especially those with the greatest needs.

Robert Hull ED.S., MHS. is a school psychologist in Prince Georges County Maryland, He has worked for over 30 years in schools addressing trauma concerns. In addition to his degrees in School Psychology he also holds a graduate degree in Public Health from Johns Hopkins University. Eric Rossen is a nationally certified school psychologist and licensed psychologist in Maryland. He currently serves as Director of Professional Development and Standards at the National Association of School Psychologists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: International School Meals Day at Harmony Hills Elementary School in Silver Spring, MD by USDA. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Supporting and educating unaccompanied students from Central America appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesSharks, asylum seekers, and Australian politicsFive myths about the “surge” of Central American immigrant minors

Related StoriesWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesSharks, asylum seekers, and Australian politicsFive myths about the “surge” of Central American immigrant minors

Boxes and paradoxes

It was eerie, a gift from the grave. But I thank serendipity, not spooks. The gift, it turns out, was given forty years ago. When Dorothy Wrinch cleared out her office in the Smith College Science Center, she left her books for the library, her burgeoning notebooks and contentious correspondence for the archives, and three boxes of crystal models and model parts for me. But I was on sabbatical, and whoever stashed the boxes in the basement never told me. They’d be there still had a young colleague not gone rummaging for something else last fall and found them, “For Mrs. Senechal” pencilled on the top. And so they reached me at last. Forty years ago, I would have treasured these models as she had. But what can I do with them now?

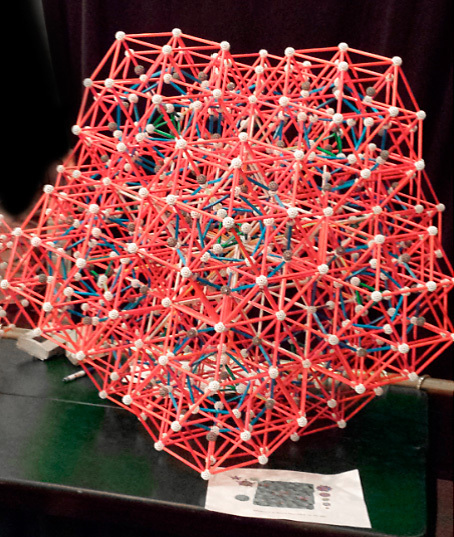

Bring them to Montreal for show-and-tell? Crystallographers from all over the world are gathering there for their triennial Congress. The year 2014 is a special anniversary. On the eve World War I, an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge, William Lawrence Bragg, walking along the river behind his college, found the Rosetta Stone of the solid state. The then-recent discovery that crystals scatter x-rays had solved for the x: the mysterious rays are waves, like light. Bragg turned this around, deciphering the structures of simple crystals from the patterns in their scattered rays. Today’s textbooks trace the path from his work on table salt and diamond to the double helix, modern drug design, and the highest of high-tech materials. We forget that the path was neither easy nor straight. The boxes of chipped and scattered model parts Wrinch left me bear witness to the early years, when scientists argued over whether salt is really the 3-D atomic checkerboard Bragg said it was, whether proteins are chains or rings as Wrinch said they were, and how to interpret the diffraction patterns of mind-bogglingly complicated crystals.

But the boxes are bulky and too heavy for airlines that charge by the ounce. So what should I do with them? I’m deeply touched by the gift; I won’t throw them out. But if they were ever user-friendly, they aren’t anymore. It’s hard to fit the rods into the balls, and the paint on the balls is flaking. And who needs real models now, when we have vivid, interactive computer graphics on our iPads? (Let’s get that one out of the way: real models are still working tools for me and I’m not alone.) No, it’s not their aged parts, it’s their aged ideas that make these models obsolete.

Figure 1. A ball from the box of model parts that Dorothy Wrinch left for me.

One book Wrinch didn’t leave for the library was a massive, gilded tome called Grammar of Ornament. It’s a cornerstone of the decorative arts, a veritable catalogue of rectangular swatches of floor, wall, and ceiling patterns created by people in all times and places. She loved this book because ornaments are like 2-D crystals. This analogy was crystallography’s chief paradigm, questioned by no one: the atoms in crystals repeat periodically in space. If you know one swatch (crystallographers call it a unit cell), you know the whole thing. A Grammar of Crystals would be a catalogue of swatches of 3-D atomic patterns. But that was then. Swatches are to modern crystallography as Pythagoras’s whole-number ratios are to √2 and pi. They’re still useful, but they’re not the whole story. The world of crystals, like the world of numbers, turns out to be bigger than anyone imagined.

Look closely at Wrinch’s wooden balls (Figure 1). The holes are drilled at the corners of squares, and at the centers of those squares, and at the centers of their edges. Six squares make a cube; if you picked up a ball and turned it around, you’d see the cubic pattern. With balls like these and rods to connect them, you can build 3-D swatches that stack like bricks to fill space. And that’s all you can build. But as the last century drew to a close, this paradigm crumbled. There are crystals, we now know, whose atomic patterns don’t repeat like ornaments. They spring surprises at every turn (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Left: To create this pattern, just fit the swatches together. Right: How would you extend this swatchless pattern?

Aperiodic crystals have opened a new chapter; what will its paradigms be? At this still-early stage, we conjecture, argue, explore the new terrain from every angle. It’s fitting, and telling, that the Montreal Congress will be a double celebration. If ever a scientific discovery changed the world, x-ray crystallography did. But, paradoxically, the Congress will give its plums and prizes this year to the scientists who consigned its paradigm to history’s basement and sent us back to basics.

Figure 3. Compare the flexibility of this modern Zome Tool connector with its rigid ancestor in Figure 1.

Figure 4. A model of an actual non-repeating crystal structure made with Zome Tools by my students at the Park City Mathematics Institute, July 2014. Though aperiodic, this pattern of atoms can be extended in space.

I’ll put Wrinch’s models back in storage. She wouldn’t mind. “A science which hesitates to forget its founders is lost,” Alfred North Whitehead declared in 1916. A mature science, he explained, reconfigures itself as a logical structure from which the arguments and passions that built it are erased. Dorothy, then a student of his colleague Bertrand Russell, took the logical structure of science as a challenge. Later, when she ventured into less abstract realms, their reconfiguration was her mission. She would be delighted, I think, that so much of crystallography is automated today, and that the Grammar of Crystals is a databank. She would be delighted by new vistas to be reconfigured with modern models. And she would be delighted that crystallographers are still arguing.

Marjorie Senechal is the Louise Wolff Kahn Professor Emerita in Mathematics and History of Science and Technology, Smith College, and Co-Editor of The Mathematical Intelligencer. She is author of I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science. She will be attending the International Union Of Crystallography Congress in Montreal 5-12 August 2014.

Chemistry Giveaway! In time for the 2014 American Chemical Society fall meeting and in honor of the publication of The Oxford Handbook of Food Fermentations, edited by Charles W. Bamforth and Robert E. Ward, Oxford University Press is running a paired giveaway with this new handbook and Charles Bamforth’s other must-read book, the third edition of Beer. The sweepstakes ends on Thursday, August 14th at 5:30 p.m. EST.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Photos by Marjorie Senechal.

The post Boxes and paradoxes appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPaul Otlet, Google, Wikipedia, and cataloging the worldWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesThe British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part two)

Related StoriesPaul Otlet, Google, Wikipedia, and cataloging the worldWhy you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesThe British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part two)

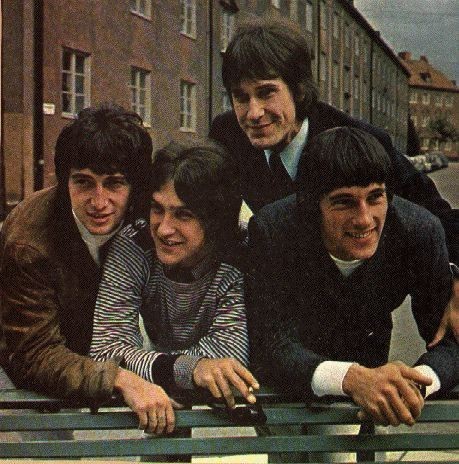

The British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part two)

In the opening months of 1964, The Beatles turned the American popular music world on its head, racking up hits and opening the door for other British musicians. Lennon and McCartney demonstrated that—in the footsteps of Americans like Buddy Holly and Chuck Berry—British performers could be successful songwriters too. In the summer, “A Hard Day’s Night” would prove that their success had not been a winter fluke or a momentary bit of post assassination frenzy.

It wasn’t that the Brits had been absent from the very profitable American market: Joe Meek had had success with the Tornados’ “Telstar” at the end of 1962. But before The Beatles, few in America cared much at all about what the British recording industry released. Indeed, British irrelevancy lay behind Capitol’s decision not to release recordings by The Beatles until news coverage got ahead of them.

In the wake of the Beatles, some of the evolving diversity of British songwriting emerged and the first stage came from composers associated with the heart of London’s music publishing world: Denmark Street. Publishers and musical instrument stores still call that short stretch of pavement home, but in the early to mid-sixties, everyone from the Beatles to the Kinks had been there. You could record at Regent Sound Studios (as did The Rolling Stones and The Who), you could grab a coffee with session musicians at Julie’s Café, or buy an ad at either Melody Maker or The New Musical Express. Indeed, The Beatles had gotten a huge break through publisher Dick James whose offices were at the corner of Denmark Street and Charing Cross Road.

A promotional photo of British rock group The Kinks, taken in Stockholm, Sweden, ca. 2 September 1965. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1963, Lennon and McCartney’s major competitor was Mitch Murray who had had a string of hits with Gerry and the Pacemakers (“How Do You Do It?”) and Freddie and the Dreamers (“I’m Telling You Now”). Murray’s forte was the simple, catchy lyric and tune, purchased and consumed in an instant, paid for by happy teens who eagerly waited for the next release. His songs had proved so successful in 1963 that John Lennon jokingly (perhaps) suggested that another challenge to the Lennon-McCartney catalogue could result in bruises for their competitor. Notably in this period, both the Liverpudlians and this Londoner published through Dick James Music.

However a particularly interesting composition emerged from the pen of another Denmark Street songwriter, this time associated with Southern Music. The twenty-nine-year-old Geoff Stephens was never much of a musician, but he had an ear for lyrics and tunes and “The Crying Game” had begun as a title and a premise. The title “seemed the perfect seed from which to grow a very good pop song,” he recalled. “We all know what it’s like to cry and have deep feelings.” Still, the song’s convoluted melody and irregular prosody made it an unlikely hit for 1964, but succeed it did.

Click here to view the embedded video.

A winning interpretation would come through Dave Berry whose breathy and exposed voice served as the perfect instrument for the melody, even if he initially thought the music inappropriate for him. (He saw himself as a rhythm-and-blues artist.) Decca producer Mike Smith (who had auditioned the Beatles back in 1962) brought in Reg Guest to serve as music director who, in turn, hired guitarist Big Jim Sullivan to complement Berry’s emotive interpretation. Employing a foot pedal meant for a steel guitar that controlled both tone and volume, Sullivan put the musical equivalent of crying into the recording. The result deeply impressed Beatle George Harrison who sought to find out how to recreate the sound (something he would accomplish the next year on songs like “I Need You” and “Yes It Is”).

Not all non-performer songwriters in this era had deep ties to Denmark Street. Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley had met at University College School as teens, sported proper academic degrees, had worked at the BBC, and were active participants in the intellectual world of late fifties and early sixties London. In 1964 they collaborated on the song “Have I the Right” and in a tavern found the Sheritons whom they believed were perfect to deliver their plea for love. The musical and lyrical materials are simple, but catchy, and demanded a distinctive sound and interpretation.

No one could better create a distinctive sound in London at the time than the enigmatic Joe Meek in his home studio on Holloway Road in North London. In order to create a sound around the band and the song, Meek turned to the four-on-the-floor musical grooves that had been popular that year (notably heard on recordings by another North London group, the Dave Clark Five). Meek recorded clipped microphones to the stairs outside his studio and had the band stomp in time with the music, perhaps in imitation of the Dave Clark Five’s “Bits and Pieces.” Next, he repeatedly overdubbed a guitar part and played with the tape speed to give it a wavering bell-like quality.

Howard and Blaikley would lease the recording to Louis Benjamin at Pye Records, who thought that the Sheritons needed a new name. Seeing the band’s female hairdresser-drummer Honey Lantree as its visual distinction and marketing hook, he renamed the band, The Honeycombs. The song topped British charts late in the summer and successfully climbed American charts that fall. The songwriters would become the band’s managers and continue to write music for them, although they never quite duplicated their success.

Click here to view the embedded video.

But where were British songwriters who also performed their own material? Jagger and Richards of The Rolling Stones had written “As Tears Go By,” but had decided to give it to Marianne Faithful. (They didn’t think it appropriate for themselves to release, at least as a single.) The band had also recorded a demo of another Jagger-Richards tune, “Tell Me,” at Regent Sound Studios in Denmark Street, only to discover that their manager Andrew Oldham had released it in America. Despite its modest success, Richards has since cited this recording as evidence of how little control they had over their career at this stage. They wouldn’t record their first real self-penned success early the next year with “The Last Time.”

More significantly during the summer of ‘64, one of the most important British artists of the era woke up every garage band on both continents, simultaneously frightening parents and the custodians of culture.

In July 1964 at IBC Studios in London, Shel Talmy prepared to give an unlikely group of musicians their last chance to have a hit. Talmy was a Los Angeles transplant, an outsider to the London recording scene who preferred to work as an independent artist-and-repertoire manager. Through hard work, good luck, and a bit of bluff, he had managed almost immediate success, much to the jealousy of the locals.

The group on whom he was gambling had the Davies Brothers as its leaders who had beaten the odds to get a recording contract, but who had struck out with their first two releases. The Kinks’ version of Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” had the misfortune of comparison with The Beatles, who were now using the tune to close their shows and who would soon release their own version of it. Their next attempt was a composition by Ray Davies. “You Still Want Me” carries all the hallmarks of early sixties British pop and, consequently, had very little that would distinguish The Kinks from everyone else.

“You Really Got Me” would be the song that lifted them to success. They arrived to record it at IBC Studios in July 1964 after already taping a slower and more bluesy version. Davies and Talmy (although they might disagree about the process later) agreed that a faster version could be more successful and booked time at the studio late at night. To insure success, Talmy had engaged session drummer Bobby Graham, who was already known around professional circles as at least one of the drummers on the Dave Clark Five records. He also brought in the veteran bandleader Art Greenslade to play piano.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Graham and Greenslade had been at a previous recording session earlier that night where a contractor had asked them to do a second session. After a pint or two and a bite to eat, they showed up at IBC for a date with the Kinks. Their first reaction, according to Greenslade, was a one of slightly restrained horror at the sight of the band; but, after a short rehearsal, they settled into a good working relationship. The band’s drummer, Mick Avory, settled into playing the tambourine.

Knowing full well, that you get six sides to get a hit, Ray Davies remembered years later the tension that night. “When that record starts it’s like… doing the four-minute mile; there’s a lot of emotion.” He remembers shouting at Dave, “willing him to do it, saying it was the last chance we had.” Brother Dave apparently responded with an expletive and launched into what must be one of the original punk guitar solos played through a ripped speaker. Talmy, for his part, tried to capture the sound and to shape it in a distinctive way, employing the young Glyn Johns and Bob Auger as his engineers.

The recording of “You Really Got Me” would establish The Kinks as one of Britain’s most important bands and Ray Davies as a songwriter to be watched.

Gordon R. Thompson is Professor of Music and Chair of the Department of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Gordon Thompson will be speaking at a number of Capital District venues in February. His lecture, “She Loves You: The Beatles and New York, February 1964,” will contextualize that band’s historic relationship with the Empire State. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part two) appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part one)Why you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesPaul Otlet, Google, Wikipedia, and cataloging the world

Related StoriesThe British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part one)Why you can’t take a pigeon to the moviesPaul Otlet, Google, Wikipedia, and cataloging the world

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers