Oxford University Press's Blog, page 773

August 18, 2014

Challenges facing UK law students

Making the leap between school and university can be a stretch at the best of times, but for UK law students it can be a real struggle. As there is no requirement to study law at school before beginning an undergraduate programme, many new law students have a very limited knowledge of how the law works and what they can expect from their studies.

We asked a group of 77 law students from around the UK about how they prepared for their courses. It turns out, only a third of them did any reading before starting, but a vast majority would have done, if only their university had given them a bit of advice.

The post Challenges facing UK law students appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe OUP and BPP National Mooting CompetitionThe First World War and the development of international lawPublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journal

Related StoriesThe OUP and BPP National Mooting CompetitionThe First World War and the development of international lawPublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journal

The First World War and the development of international law

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated in Sarajevo, setting off a six week diplomatic battle that resulted in the start of the First World War. The horrors of that war, from chemical weapons to civilian casualties, led to the first forays into modern international law. The League of Nations was established to prevent future international crises and a Permanent Court of International Justice created to settle disputes between nations. While these measures did not prevent the Second World War, this vision of a common law for all humanity was essential for international law today. To mark the centenary of the start of the Great War, and to better understand how international law arose from it, we’ve compiled a brief reading list.

The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law, Edited by Bardo Fassbender, Anne Peters, and Simone Peter

How did international law develop from the 15th century until the end of World War II? This 2014 ASIL Certificate of Merit winnor looks at the history of international law in relation to themes such as peace and war, the sovereignty of states, hegemony, and the protection of the individual person. It includes Milos Vec’s ‘From the Congress of Vienna to the Paris Peace Treaties of 1919′ and Peter Krüger’s ‘From the Paris Peace Treaties to the End of the Second World War’.

Formalizing Displacement: International Law and Population Transfers by Umut Özsu

A detailed study into the 1922-34 exchange of minorities between Greece and Turkey, supported by the League of Nations, in which two million people were forcibly relocated. Check out the specific chapters on: Wilson and international law; US jurisprudence and international law in the wake of WWI; and the failed marriage of the US and the League of Nations and America’s reaction of isolationism through WWII.

The Birth of the New Justice: The Internationalization of Crime and Punishment, 1919-1950 by Mark Lewis

How could the world repress aggressive war, war crimes, terrorism, and genocide in the wake of the First World War? Mark Lewis examines attempts to create specific criminal justice courts to address these crimes, and the competing ideologies behind them.

A History of Public Law in Germany 1914-1945 by Michael Stolleis, Translated by Thomas Dunlap

How did the upheaval of the first half of the 20th century impact the creation of public law within and across states? Germany offers an interesting case given its central role in many of the events.

“Neutrality and Multilateralism after the First World War” by Aoife O’ Donoghue in the Journal of Conflict and Security Law

What exactly did ‘neutrality’ mean before, during, and after the First World War? The newly independent Ireland exemplified many of the debates surrounding neutrality and multilateralism.

The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, 28th June 1919 by William Orpen. Imperial War Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, 28th June 1919 by William Orpen. Imperial War Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.“What is Aggression? : Comparing the Jus ad Bellum and the ICC Statute” by Mary Ellen O’Connell and Mirakmal Niyazmatov in the Journal of International Criminal Justice

The Treaty of Versailles marked the first significant attempt to hold an individual — Kaiser Wilhelm — accountable for unlawful resort to major military force. Mary Ellen O’Connell and Mirakmal Niyazmatov discuss the prohibition on aggression, the Jus ad Bellum, the ICC Statute, successful prosecution, Kampala compromise, and protecting the right to life of millions of people.

“Delegitimizing Aggression: First Steps and False Starts after the First World War” by Kirsten Sellars in the Journal of International Criminal Justice

Following the First World war, there was a general movement in international law towards the prohibition of aggressive war. So why is there an absence of legal milestones marking the advance towards the criminalization of aggression?

“The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia: The Third Wang Tieya Lecture” by Mohamed Shahabuddeen in the Chinese Journal of International Law

What is the bridge between the International Military Tribunal, formed following the Treaty of Versailles, and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia? Mohamed Shahabuddeen examines the first traces of the development of international criminal justice before the First World War and today’s ideas of the responsibility of the State and the criminal liability of the individual.

“Collective Security, Demilitarization and ‘Pariah’ States” by David J. Bederman in the European Journal of International Law

When are sanctions doomed to failure? David J. Bederman analyzes the historical context of the demilitarization sanctions imposed against Iraq in the aftermath of the Gulf War of 1991 from the 1919 Treaty of Versailles through to the present day.

“Peace Treaties after World War I” by Randall Lesaffer, Mieke van der Linde in the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

How did legal terminology and provisions concerning hostilities, prisoners of war, and other wartime-related concerns change following the introduction of modern warfare during the First World War?

“League of Nations” by Christian J Tams in the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

What lessons does the first body of international law hold for the United Nations and individual nations today?

“Alliances” by Louise Fawcett in the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

Peace was once ensured through a complex web of diplomatic alliances. However, those same alliances proved fatal as they ensured that various European nations and their empires were dragged into war. How did the nature of alliances between nations change following the Great War?

“International Congress of Women (1915)” by Freya Baetens in the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

In the midst of tremendous suffering and loss, suffragists continued to march and protest for the rights of women. How did the First World War hinder the women’s suffrage movement, and how did it change many of the demands and priorities of the suffragists?

“History of International Law, World War I to World War II” by Martti Koskenniemi in the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

A brief overview of the development of international law during the interwar period: where there was promise, and where there was failure.

Headline image credit: Stanley Bruce chairing the League of Nations Council in 1936. Joachim von Ribbentrop is addressing the council. Bruce Collection, National Archives of Australia. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The First World War and the development of international law appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRemembering 100 years: Fashion and the outbreak of the Great WarThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorshipWorld Refugee Day Reading List

Related StoriesRemembering 100 years: Fashion and the outbreak of the Great WarThe Lady: One woman against a military dictatorshipWorld Refugee Day Reading List

A Fields Medal reading list

One of the highest points of the International Congress of Mathematicians, currently underway in Seoul, Korea, is the announcement of the Fields Medal prize winners. The prize is awarded every four years to up to four mathematicians under the age of 40, and is viewed as one of the highest honours a mathematician can receive.

This year sees the first ever female recipient of the Fields Medal, Maryam Mirzakhani, recognised for her highly original contributions to geometry and dynamical systems. Her work bridges several mathematic disciplines – hyperbolic geometry, complex analysis, topology, and dynamics – and influences them in return.

We’re absolutely delighted for Professor Mirzakhani, who serves on the editorial board for International Mathematics Research Notices. To celebrate the achievements of all of the winners, we’ve put together a reading list of free materials relating to their work and to fellow speakers at the International Congress of Mathematicians.

“Ergodic Theory of the Earthquake Flow” by Maryam Mirzakhani, published in International Mathematics Research Notices

Noted by the International Mathematical Union as work contributing to Mirzakhani’s achievement, this paper investigates the dynamics of the earthquake flow defined by Thurston on the bundle PMg of geodesic measured laminations.

“Ergodic Theory of the Space of Measured Laminations” by Elon Lindenstrauss and Maryam Mirzakhani, published in International Mathematics Research Notices

A classification of locally finite invariant measures and orbit closure for the action of the mapping class group on the space of measured laminations on a surface.

“Mass Forumlae for Extensions of Local Fields, and Conjectures on the Density of Number Field Discriminants” by Majul Bhargava, published in International Mathematics Research Notices

Manjul Bhargava joins Maryam Mirzakhani amongst this year’s winners of the Fields Medal. Here he uses Serre’s mass formula for totally ramified extensions to derive a mass formula that counts all étale algebra extentions of a local field F having a given degree n.

“Model theory of operator algebras” by Ilijas Farah, Bradd Hart, and David Sherman, published in International Mathematics Research Notices

Several authors, some of whom speaking at the International Congress of Mathematicians, have considered whether the ultrapower and the relative commutant of a C*-algebra or II1 factor depend on the choice of the ultrafilter.

“Small gaps between products of two primes” by D. A. Goldston, S. W. Graham, J. Pintz, and C. Y. Yildrim, published in Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society

Speaking on the subject at the International Congress, Dan Goldston and colleagues prove several results relating to the representation of numbers with exactly two prime factors by linear forms.

“On Waring’s problem: some consequences of Golubeva’s method” by Trevor D. Wooley, published in the Journal of the London Mathematical Society

Wooley’s paper, as well as his talk at the congress, investigates sums of mixed powers involving two squares, two cubes, and various higher powers concentrating on situations inaccessible to the Hardy-Littlewood method.

Image credit: (1) Inner life of human mind and maths, © agsandrew, via iStock Photo. (2) Maryam Mirzakhani 2014. Photo by International Mathematical Union. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A Fields Medal reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMiles Davis’s Kind of BluePublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journalEngaged Buddhism and community ecology

Related StoriesMiles Davis’s Kind of BluePublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journalEngaged Buddhism and community ecology

August 17, 2014

Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue

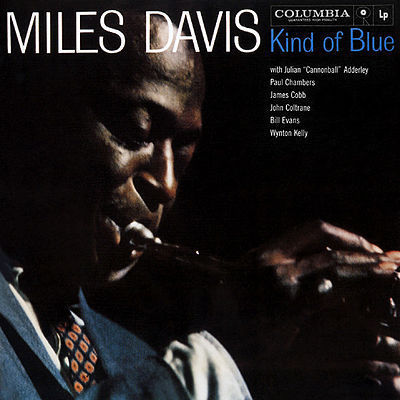

What is a classic album? Not a classical album – a classic album. One definition would be a recording that is both of superb quality and of enduring significance. I would suggest that Miles Davis’s 1959 recording Kind of Blue is indubitably a classic. It presents music making of the highest order, and it has influenced — and continues to influence — jazz to this day.

Cover art for Kind of Blue by the artist Miles Davis (c) Columbia Records via Wikimedia Commons.

Cover art for Kind of Blue by the artist Miles Davis (c) Columbia Records via Wikimedia Commons.There were several important records released in 1959, but no event or recording matches the importance of the release of the new Miles Davis album Kind of Blue on 17 August 1959. There were people waiting in line at record stores to buy it on the day it appeared. It sold very well from its first day, and it has sold increasingly well ever since. It is the best-selling jazz album in the Columbia Records catalogue, and at the end of the twentieth century it was voted one of the ten best albums ever produced.

But popularity or commercial success do not correlate with musical worth, and it is in the music on the recording that we find both quality and significance. From the very first notes we know we are hearing something new. Piano and bass draw in the listener into a new world of sound: contemplative, dreamy and yet intense.

The pianist here is Bill Evans, who was new to Davis’s band and a vital contributor to the whole project. Evans played spaciously and had an advanced harmonic sense. His sound was floating and open. The lighter sound and less crowded manner were more akin to the understated way in which Davis himself played. “He plays the piano the way it should be played,” said Davis about Bill Evans. And although Davis’s speech was often sprinkled with blunt Anglo-Saxon expressions, he waxed poetic about Evans’s playing: “Bill had this quiet fire. . . . [T]he sound he got was like crystal notes or sparkling water cascading down from some clear waterfall.” The admiration was mutual. Evans thought of Davis and the other musicians in his band as “superhumans.”

Evans makes his mark throughout the album, though Wynton Kelly substitutes for him on the bluesier and somewhat more traditional second track “Freddie Freeloader.”

Musicians refer to the special sound on Kind of Blue as “modal.” And the term “modal jazz” is often found in writings about jazz styles and jazz history. What exactly is modal jazz? There are two characteristic features that set this style apart. The first is the use of scales that are different from the standard major and minor ones. So the first secret of the special sound on this album is the use of unusual scales. But the second characteristic is even more noticeable, and that is the way the music is grounded on long passages of unchanging harmony. “So What” is an AABA form in which all the A sections are based on a single harmony and the B sections on a different harmony a half step higher.

A [D harmony]

A [D harmony]

B [Eb harmony]

A [D harmony]

Unusual scales are most clearly heard on “All Blues.”

And for hypnotic and meditative, you can’t do better than “Flamenco Sketches,” the last track, which brings the modal conception to its most developed point. It is based upon five scales or modes, and each musician improvises in turn upon all five in order. A clear analysis of this track is given in Mark Gridley’s excellent jazz textbook Jazz Styles.)

An aside here:

It is possible — even likely — that the titles of these two tracks are reversed. In my Musical Quarterly article (link below), I suggest that “Flamenco Sketches” is the correct title for the strumming medium-tempo music on the track that is now known as “All Blues” and that “All Blues” is the correct title for the last, very slow, track on the album. I also show how the mixup occurred in 1959, just as the album was released.

Perhaps the most beautiful piece on the album is the Evans composition “Blue in Green,” for which Coltrane fashions his greatest and most moving solo. Of the five tracks on the album, four are quite long, ranging from nine to eleven and a half minutes, and they are placed two before and two after “Blue in Green.” Regarding the program as a whole, therefore, one sees “Blue in Green” as the small capstone of a musical arch. But “Blue in Green” itself is in arch form, with a palindromic arrangement of the solos. The capstone of this arch upon an arch is the thirty seconds or so of Coltrane’s solo.

Saxophone (Coltrane)

Piano Piano

Trumpet Trumpet

Piano Piano

“Blue in Green”

“Freddie Freeloader” “All Blues”

“So What” “Flamenco Sketches”

Kind of Blue

The great strength of Kind of Blue lies in the consistency of its inspiration and the palpable excitement of its musicians. “See,” wrote Davis in his autobiography, “If you put a musician in a place where he has to do something different from what he does all the time . . . that’s where great art and music happens.”

The post Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journalJob: A Masque for Dancing by Ralph Vaughan WilliamsThe rise of choral jazz

Related StoriesPublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journalJob: A Masque for Dancing by Ralph Vaughan WilliamsThe rise of choral jazz

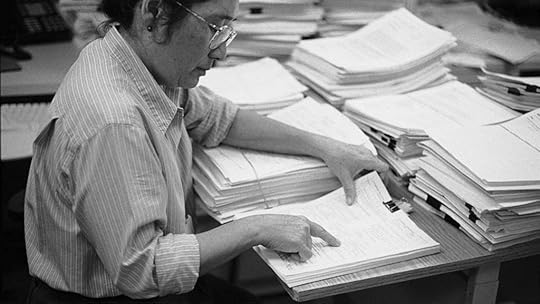

Publishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journal

One of the most common questions that scholars confront is trying to find the right journal for their research papers. When I go to conferences, often I am asked: “How do I know if Political Analysis is the right journal for my work?”

This is an important question, in particular for junior scholars who don’t have a lot of publishing experience — and for scholars who are nearing important milestones (like contract renewal, tenure, and promotion). In a publishing world where it may take months for an author to receive an initial decision from a journal, and then many additional months if they need to revise and resubmit their work to one or more subsequent journals, selecting the most appropriate journal can be critical for professional advancement.

So how can a scholar try to determine which journal is right for their work?

The first question an author needs to ask is how suitable their paper is for a particular journal. When I meet with my graduate students, and we talk about potential publication outlets for their work, my first piece of advice is that they should take a close look at the last three or four issues of the journals they are considering. I’ll recommend that they look at the subjects that each journal is focusing on, including both substantive topics and methodological approaches. I also tell them to look closely at how the papers appearing in those journals are structured and how they are written (for example, how long the papers typically are, and how many tables and figures they have). The goal is to find a journal that is currently publishing papers that are most closely related to the paper that the student is seeking to publish, as assessed by the substantive questions typically published, the methodological approaches generally used, paper framing, and manuscript structure.

Potential audience is the second consideration. Different journals have different readers — meaning that authors can have some control over who might be exposed to their paper when they decide which journals to target for their work. This is particularly true for authors who are working on highly interdisciplinary projects, where they might be able to frame their paper for publication in related but different academic fields. In my own work on voting technology, for example, some of my recent papers have appeared in journals that have their primary audience in computer science, while others have appeared in more typical political science journals. So authors need to decide in many cases which audience they want to appeal two, and make sure that when they submit their work to a journal that appeals to that audience that the paper is written in an appropriate manner for that journal.

Peer reviewer for Scientific Review by Center for Scientific Review. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Peer reviewer for Scientific Review by Center for Scientific Review. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.However, most authors will want to concentrate on journals in a single field. For those papers, a third question arises: whether to target a general interest journal or a more specialized field journal. This is often a very subjective question, as it is quite hard to know prior to submission whether a particular paper will be interesting to the editors and reviewers of a general interest journal. As general interest journals often have higher impact factors (I’ll say more about impact factors next), many authors will be drawn to submit their papers to general interest journals even if that is not the best strategy for their work. Many authors will “start high”, that is begin with general interest journals, and then once the rejection letters pile up, they will move to the more specialized field journals. While this strategy is understandable (especially for authors who are nearing promotion or tenure deadlines), it may also be counterproductive — the author will likely face a long and frustrating process getting their work published, if they submit first to general interest journals, get the inevitable rejections, and then move to specialized field journals. Thus, my advice (and my own practice with my work) is to avoid that approach, and to be realistic about the appeal of the particular research paper. That is, if your paper is going to appeal only to readers in a narrow segment of your discipline, then send it to the appropriate specialized field journal.

A fourth consideration is the journal’s impact factor. Impact factors are playing an increasingly important role in many professional decisions, and they may be a consideration for many authors. Clearly, an author should generally seek to publish their work in journals that have higher impact than those that are lower impact. But again, authors should try to be realistic about their work, and make sure that regardless of the journal’s impact factor that their submission is appropriate for the journal they are considering.

Finally, authors should always seek the input of their faculty colleagues and mentors if they have questions about selecting the right journal. And in many fields, journal editors, associate editors, and members of the journal’s editorial board will often be willing to give an author some quick and honest advice about whether a particular paper is right for their journal. While many editors shy away from giving prospective authors advice about a potential submission, giving authors some brief and honest advice can actually save the editor and the journal a great deal of time. It may be better to save the author (and the journal) the time and effort that might get sunk into a paper that has little chance at success in the journal, and help guide the author to a more appropriate journal.

Selecting the right journal for your work is never an easy process. All scholars would like to see their work published in the most widely read and highest impact factor journals in their field. But very few papers end up in those journals, and authors can get their work into print more quickly and with less frustration if they first make sure their paper is appropriate for a particular journal.

Heading image: OSU William Oxley Thompson Memorial Library Stacks by Ibagli. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Publishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journal appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImproving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna AtkesonTransforming conflict into peaceChildren learning English: an educational revolution

Related StoriesImproving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna AtkesonTransforming conflict into peaceChildren learning English: an educational revolution

The OUP and BPP National Mooting Competition

Oxford University Press and BPP Law School are proud to co-sponsor this national mooting competition which provides law students from around the country with the opportunity to practise and hone their advocacy skills. The event is now one of the most prestigious mooting competitions in the UK, where student advocates debate a fictitious case in a mock court of appeal in front of a judge. Over 140 law students embark on the contest each October; run on a knock-out basis they are whittled down over 4 rounds to the 4 who compete in the nail-biting final.

The final of the OUP and BPP National Mooting Competition 2013-2014 took place on Thursday 10th July, and proved to be a very enjoyable night of mooting indeed. Teams from Aston University, the London School of Economics, Kaplan Law School and Queen Mary, University of London battled it out for the top prize, with Theodore Anthony Meddick Dyson and Darren Low of Queen Mary, University of London emerging as worthy moot champions.

His Honour Judge Charles Gratwicke of Chelmsford Crown Court presided over the final and kept the students on their toes with some keen questioning. In his summing up, Judge Gratwicke praised the hard work and depth of knowledge the students demonstrated, saying: “You have displayed an exceptionally high standard of advocacy skills and the differences between the teams are paper-thin. You will all be successful because people of quality always find their niche”.

Preparing for the competition

An audience member at the final of the OUP and BPP National Mooting Competition 2013-2014.

Lorna Badham (Kaplan Law School)

Lorna Badham (Kaplan Law School) presenting her submissions to the Mooting final.

His Honour Judge Gratwicke

His Honour Judge Gratwicke presiding over the second moot of the evening.

Competition notes

A trial bundle prepared by a competitor for the moot.

Gerard Pitt (Kaplan Law School)

Respondents from Queen Mary University of London watch as Gerard Pitt (Kaplan Law School) delivers his submissions

Darren Low (Queen Mary)

Junior counsel for Queen Mary, Darren Low, faces His Honour Judge Gratwicke

The moot court

The moot court in session with Darren Low facing His Honour Judge Gratwicke

Drinks reception

The attendees at the drinks reception

Malvika Jaganmohan (LSE)

Malvika Jaganmohan (LSE) talks with friends after the moot

Adam Shaw-Mellors (Aston University)

Senior counsel from Aston University, Adam Shaw-Mellors, awaits the result

Awaiting the result

Friends and family watch on as His Honour Judge Gratwicke announces the winners

The winners

The 2014 winners from Queen Mary, Darren Low and Theodore Anthony Meddick Dyson, with His Honour Judge Gratwicke

All photos by Arnaud Stephenson.

The post The OUP and BPP National Mooting Competition appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe French burqa banThe terror metanarrative and the Rabaa massacreDefining intransigence and recognizing its merits

Related StoriesThe French burqa banThe terror metanarrative and the Rabaa massacreDefining intransigence and recognizing its merits

The French burqa ban

On 1 July 2014, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) announced its latest judgment affirming France’s ban on full-face veil (burqa law) in public (SAS v. France). Almost a decade after the 2005 controversial decision by the Grand Chamber to uphold Turkey’s headscarf ban in Universities (Leyla Sahin v. Turkey), the ECHR made it clear that Muslim women’s individual rights of religious freedom (Article 9) will not be protected. Although the Court’s main arguments were not the same in each case, both judgments are equally questionable from the point of view of protecting religious freedom and of the exclusion of Muslim women from public space.

The recent judgment was brought to the ECHR by an unnamed French woman known only as “SAS” against the law introduced in 2011 that makes it illegal for anyone to cover their face in a public place. Although the legislation includes hoods, face-masks, and helmets, it is understood to be the first legislation against the full-face veil in Europe. A similar ban was also passed in Belgium after the French law. France was also the first country to ban the wearing of “conspicuous religious symbols” – directed at the wearing of the headscarf in public high schools — in 2004. Since then several European countries have established policies restricting Muslim religious dress.

The French law targeted all public places, defined as anywhere not the home. Penalties for violating the law include fines and citizenship lessons designed to remind the offender of the “republican values of tolerance and respect for human dignity, and to raise awareness of her penal and civil responsibility and duties imposed life in society.”

SAS argued the ban on the full-face veil violated several articles of the European Convention and was “inhumane and degrading, against the right of respect for family and private life, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of speech and discriminatory.” She did not challenge the requirement to remove scarves, veils and turbans for security checks, also upheld by the ECHR. The ECHR rejected her argument and accepted the main argument made by the government: that the state has a legitimate interest in promoting a certain idea of “living together.”

By now, it is clear that Article 9 of the European Convention does not protect freedom of religion when the subject is a woman and the religion is Islam. While this may seem harsh, consider the ECHR’s 2011 judgment in Lautsi v. Italy, which found the display of the crucifix in Italian state schools compatible with secularism.

In Lautsi case, the Court argued that the symbol did not significantly impact the denominational neutrality of Italian schools because the crucifix is part of Italian culture. Human rights scholars have not missed the contrast between the Italian case and the earlier 2005 decision in Leyla Sahin v Turkey where the Court found that the wearing of the headscarf by students was not compatible with the principle of laicité or secularism.

The Court did not make a value judgment in SAS case about Islam, women’ rights in Islamic societies, or gender equality, as it did in earlier cases where they upheld bans on the wearing of the headscarf by teachers and students in France, Turkey and Switzerland. In all cases involving Islamic dress codes, the ECHR emphasized the “margin of appreciation” rule, which permits the court to defer to national laws.

The ECHR acted politically and opportunistically not to challenge France’s strong Republicanism and principles of laicité, sacrificing the rights of the small minority of Muslims who wear the full-face veil. Rather than protecting the individual freedom of the 2000 women, the ECHR protected the majority view of France.

The ECHR is the most powerful supra national human rights court and its decisions have widespread impact. Several countries in Europe, such as Denmark, Norway, Spain, Austria, and even the UK, have already started to discuss whether to create similar laws banning the burqa in public places. This raises concerns that cases related to the cultural behavior and religious practices of minorities could shift public opinion dangerously away from the principles of multiculturalism, democracy, human rights and religious tolerance.

Libyan girl wearing a niqab, by ليبي صح. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Libyan girl wearing a niqab, by ليبي صح. Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsThe most recent law bans the full-face veil, but tomorrow, the prohibitions may be against halal food, circumcision, the location of a mosque or the visibility of a minaret; even religious education might be banned for reasons of public health, security or cultural integration. Muslims, Roma, and to some extent Jews and Sikhs, are already struggling to be accepted as equal citizens in Europe, where right wing extremism is rising, in a situation of economic crisis.

The ECHR should be extremely careful in its decisions, given the growth of nationalism, xenophobia, and anti-immigrant sentiment in Europe.Considering this context, the EHCR’s main argument in this latest judgment is worrisome, since it accepted France’s view that covering the face in public runs counter to the society’s notion of “living together,” even though this is not one of the principles of the European Convention.

The Court recognized that the concept of “living together” was problematic (Para 122). And, even in using the “wide margin of appreciation” rule, the Court acknowledged that it should “engage in a careful examination” to avoid majority’s subordination of minorities. Considering the Court’s own rules, the main reasoning for the full face veil ban—“living together” seems to be inconsistent with the Court’s own jurisprudence.

Further concerns were raised about Islamophobic remarks during the adoption debate of the French Burqa Law, and evidence that prejudice and intolerance against Muslims in French society influenced the adoption of the law. Such concerns were more strongly raised by the two dissenting opinions. The dissent found the Court’s insensitivity to what’s needed to ensure tolerance between the vast majority and a small minority could increase tensions (Para 14). The dissenting opinion was especially critical of prioritizing “living together,” not even a Convention principle, over “concrete individual rights” guaranteed by the Convention.

While the integration of Muslims and other immigrants across Europe is a legitimate concern, it is vitally important the ECHR’s constructive role. The decision in SAS v France is a dangerous jurisprudential opening for future cases involving the religious and cultural practices of minorities. The French burqa law has created discomfort among Muslims. By upholding the law, the European court deepens the mistrust between the majority of citizens and religious minorities.

Headline image credit: Arabic woman in Muslim religious dress, © Vadmary, via iStock Photo..

The post The French burqa ban appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe terror metanarrative and the Rabaa massacreVeils and the choice of societyDefining intransigence and recognizing its merits

Related StoriesThe terror metanarrative and the Rabaa massacreVeils and the choice of societyDefining intransigence and recognizing its merits

August 16, 2014

Remembering 100 years: Fashion and the outbreak of the Great War

In August 2014 the world marks the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War.

A time of great upheaval for countless aspects of society, social, economic and sexual to name a few, the onset of war punctured the sartorial mold of the early 20th century and resulted in perhaps one of the biggest strides to clothing reform that women had ever seen.

The turn of the century began with a feeling of unease and fevered anticipation regarding the changing political climate; the ‘new woman’ of the fin-de-siècle and the clothes associated with her threatened to disrupt conservative gender values of the middle and upper classes. But the position of women was about to take an even sharper turn. As it soon became necessary to recruit women into the war effort, hemlines got shorter, cuts became looser, and the two-piece suit took centre stage for the first time, making way for more practical attire. Women experienced a relative degree of liberation, entering professions and industries previously dominated by men, which created the need for an entirely new ‘working wardrobe’.

Official Yeowoman’s Costume of the US Navy 1101 Delineator, November 1918. Commercial Pattern Archive, University of Rhode Island. Joy Emery explores the development of US service uniforms and the introduction of women’s trousers during the First World War in her authoritative

A History of the Paper Pattern Industry

(Bloomsbury, 2014).

Official Yeowoman’s Costume of the US Navy 1101 Delineator, November 1918. Commercial Pattern Archive, University of Rhode Island. Joy Emery explores the development of US service uniforms and the introduction of women’s trousers during the First World War in her authoritative

A History of the Paper Pattern Industry

(Bloomsbury, 2014).Permeating mainstream and avant-garde fashion and fuelling the rise of the female’s role in the public sphere, fashion was about to move in a new, androgynous direction. Practical clothing influenced by men’s tailoring led the way and the suit, newly composed of jackets and skirts, developed its own identity as a women’s garment with soft, loose lines. In the world of high fashion, Paul Poiret and his taste for the ‘exotic’ firmly established the innovative trend for the tube-like silhouette, which reverberated throughout the fashion sphere more broadly. The kimono similarly burst onto the scene, reflecting the sentiment for looser and freer garments. Also, perhaps less well-remarked is the rapid development of the department store in Europe, which acknowledged the increasingly varied roles of women and made ready-made garments more available than ever before.

The changes were not only evident in Britain. Relationships between Germany and the French houses that dominated the fashion scene became increasingly fraught at the outbreak of war. As Irene Guenther remarks in Nazi Chic?, “the war was viewed as providing the perfect opportunity to unseat France, militarily and sartorially, from its throne. Because the conflict had slowed down the French fashion machine, a space had developed that the German nation was eager and ready to fill.” Luxury items imported from France, including silk, lace, and leather gloves were forbidden and a culture of “make do and mend” was established, which was set to echo throughout the Second World War that was to follow.

The Great War and its disruptions, dislocations, and recastings is rarely remembered for its creative output, but the war made way for innovative fashions and manufacturing techniques to suit a rapidly changing society and the new roles for the women and men who inhabited it. The sartorial changes witnessed in this turbulent decade became visual signifiers of the larger upheavals facing British and European society more generally, and we only have to look to our sartorial history from this period to sneak a peek at the way in which societal roles were uprooted and the face of women’s fashion markedly changed.

The post Remembering 100 years: Fashion and the outbreak of the Great War appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Fair Toxophilities and Daniel Deronda1914: The opening campaignsPolitical map of Who’s Who in World War I [infographic]

Related StoriesThe Fair Toxophilities and Daniel Deronda1914: The opening campaignsPolitical map of Who’s Who in World War I [infographic]

Getting to know Exhibits Coordinator Erin Hathaway

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into work in our offices around the globe, so we are excited to bring you an interview with Erin Hathaway, a Marketing and Exhibits Coordinator at Oxford University Press. We spoke to Erin about her life here at OUP — which includes organizing over 250 conferences that our marketers attend each year.

When did you start working at OUP?

I started working at OUP in May 2012.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

I spend most of my day working with our Exhibits Management System (EMS), our database that helps us coordinate and prepare for the over 250 conferences that our team manages each year. Our work also involves closely monitoring conference budgets and making sure we’ve covered all the bases in regards to our booth set up, attendance, AV needs and book lists. In those few months out of each year when the conference load lightens up, I do some fiscal analysis and create training documentation to help our conference stakeholders.

Erin Hathaway

Erin HathawayWhat is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

It’s a three-way tie between a Transformer, a painted skull, and a Wonder Woman metal poster.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Read my email to check for any conference emergencies or time sensitive deadlines. Then I go get a cup of tea.

What’s your favorite book?

The Black Company by Glenn Cook.

What is the most exciting project you have been part of while working at OUP?

We recently transitioned the storage of our journals from a third party warehouse into our warehouse in Cary, North Carolina. While difficult at times, the move has saved us both financially and logistically by allowing us to combine our books and journals onto one pallet for a given conference. This project allowed me to work closely with people from different areas of OUP, from the Journals Production team to the Cary warehouse staff. Everyone was extremely helpful in getting this transition underway and it was exciting to see a project long imagined come to fruition.

What is your favorite word?

I like the word “tactile.”

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

I love strategy meetings with the Exhibits team where we dream up ways to make our systems more efficient.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

A Kindle filled with many books, my chainmail jewelry kit (a side business of mine), and a comfortable pillow. I’m assuming basic necessities have been covered, otherwise my choices are not very smart.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

After working here for over six years, I’m constantly amazed by how much things have changed. In the moment, it feels like change comes so slowly. Yet, when I look back on how OUP was organized and the systems we were using when I started in 2008, I’m amazed by how committed OUP is to making our company more efficient and incorporating new technology.

Headline image credit: Oxford University Press by George Sylvain. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Getting to know Exhibits Coordinator Erin Hathaway appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGetting to know Product Marketer Erin McAuliffeCatching up with Alyssa BenderDefining intransigence and recognizing its merits

Related StoriesGetting to know Product Marketer Erin McAuliffeCatching up with Alyssa BenderDefining intransigence and recognizing its merits

Defining intransigence and recognizing its merits

On any given day, a Google search finds the word “intransigent” deployed as though it automatically destroyed an opponent’s position. Charles Blow of the New York Times and Jacob Weisberg (no relation to the present writer) of Slate are only two of many, especially on the political left, who label Republicans “intransigent” and thereby assume they have won the argument against them.

The first intransigents, however, were on the extreme left. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the usage “intransigent” to 1873, when an extreme left party in the Spanish Cortes called themselves “los intransigentes.” Interestingly, the Spaniards did not think their self-description worked any harm to their political positions, which they felt deserved to be stated forthrightly, without compromise, and passionately.

By the early 1880s, Democrats in the United States reversed the political origins of the word when they pinned “intransigence” (as a noun) on “an uncompromising republican”. Since then, the left more than the right has mapped “intransigence” onto “extremism,” often assuming without substantive analysis that an unwillingness to compromise a position makes it not only untenable but also bizarre.

Of course, we live in a world that unhesitatingly accepts flexibility and compromise as basically good and even as a goal unto itself. However, a willingness – too often made into a norm – to compromise strongly held viewpoints has repetitively brought on destruction and death. Wouldn’t the outcome have been better if Neville Chamberlain at Munich in 1938 had dealt obstinately and inflexibly with Adolf Hitler? Shouldn’t post 9/11 Americans have been less elastic in their willingness to negotiate away our country’s prior taboo on torture?

So it turns out that intransigence is not always bad and should not be used as a pejorative until the writer defines substantively the position he is attacking. Holding firm is sometimes good and sometimes bad, exactly as being flexible can be terribly wrong if what we give away to prove we are flexible is actually something that was good.

I define intransigence as “a resistance to the urge to shift malleably from positions thought to be sound.” This definition is neutral as to the merits or demerits of the deeply held viewpoint. That part is up to all of us, who should think through what is vitally important to us individually, stick to it, fight for it, and abandon the fallacy that even those whose positions we detest are clearly wrong because they, too, are intransigent. If we are right and they are wrong, the matter will be decided because of the position we take and not our inflexibility in propounding it.

President Obama has just publicly recognized that we should not have collectively caved in on the practice of torture. Those few people who adamantly refused from 9/12 onwards to compromise that taboo deserve to be called both correct and intransigent.

Headline image: Fist. Photo by George Hodan. Public domain via PublicDomainPictures.net.

The post Defining intransigence and recognizing its merits appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHobby Lobby and the First AmendmentThe terror metanarrative and the Rabaa massacreEngaged Buddhism and community ecology

Related StoriesHobby Lobby and the First AmendmentThe terror metanarrative and the Rabaa massacreEngaged Buddhism and community ecology

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers