Oxford University Press's Blog, page 770

August 25, 2014

A Woman’s Iliad?

Browsing my parents’ bookshelves recently, in the dog days that followed sending Anna Karenina off to press, I found myself staring at a row of small hardback volumes all the same size. One in particular, with the words Romola and George Eliot embossed in gold on the dark green spine, caught my attention. It was an Oxford World’s Classics pocket edition – a present to my grandmother from her younger sister, who wrote an affectionate inscription in curling black ink (“with Best Love to Dellie on her 20th birthday from Mabel, July 3rd 1917”), and forgot to rub out the price of 1 shilling and 3 pence pencilled inside the front cover. Inside the back cover, meanwhile, towards the bottom of a long list of World’s Classics titles, my heart missed a beat when I espied “Tolstoy, Anna Karenina: in preparation”: Louise and Aylmer Maude’s translation was first published only in 1918.

As I drove homethat night with Romola in my bag, I thought about my grandmother reading Eliot’s novel (unusually set in Florence during the Renaissance, rather than in 19th-century England), and I also thought about the seismic changes taking place in Russia at the time of her birthday in 1917. I wondered whether she was given the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of Anna Karenina for her 21st birthday, and was disappointed on a later visit to my parents to be presented with her copy of Nathan Haskell Dole’s pioneering but wholly inadequate translation, reprinted in the inexpensive Nelson Classics series. I pictured my grandmother struggling with sentences such as those describing Anna’s hostile engagement with her husband. After Karenin has begun upbraiding Anna for consorting too openly with Vronsky at the beginning of the novel (Part 2, chapter 9), we read, for example: ‘“Nu-s! I hear you,” she said, in a calm tone of banter’. The Maudes later translated this sentence into English (“Well, I’m listening! What next?” said she quietly and mockingly”), but they also changed Tolstoy’s punctuation, and the sarcastically deferential tone of Anna’s voice (Nu-s, ya slushayu, chto budet, – progovorila ona spokoino i nasmeshlivo – “Well, I’m ready to hear what is next,” she said coolly and derisively”).

Back in 1917, Oxford Word’s Classics “pocket editions” featured a line-drawn portrait of the author, but no other illustration. These days, nearly every edition of Anna Karenina has a picture of a woman on the cover, even if Tolstoy’s bearded face is absent opposite the title page. More often than not it will be a Russian woman, painted by a Russian artist, and while we know this is not Anna, it is as if the limits of our imagination are somehow curbed before we even start reading. The dust-jacket for the new hardback Oxford World’s Classics edition of Anna Karenina reproduces Sir John Everett Millais’ portrait of Louise Jopling. The fact that this is an English painting of an English woman already mitigates against identifying her too closely with Anna, but this particular portrait is an inspired choice for other reasons, as I began to understand when I researched its history. To begin with, it was painted in 1879, just one year after Anna Karenina was first published as a complete novel. And the meticulous notes compiled by Vladimir Nabokov which anchor the events of the narrative between 1872 and 1876 also enable us to infer that the fictional Anna Karenina was about the same age as the real-life Louise Jopling, who was 36 when she sat for Millais. Their very different life paths, meanwhile, throw an interesting light on the theme at the centre of Tolstoy’s novel: the predicament of women.

Louise Jane Jopling (née Goode, later Rowe), by Sir John Everett Millais. National Portrait Gallery, London: NPG 6612. Wikimedia Commons

Louise Jane Jopling (née Goode, later Rowe), by Sir John Everett Millais. National Portrait Gallery, London: NPG 6612. Wikimedia CommonsLouise Jopling was one of the nine children born into the family of a railway contractor in Manchester in 1843. After getting married for the first time in 1861 at the age of 17 to Frank Romer, who was secretary to Baron Nathaniel de Rothschild, she studied painting in Paris, but returned to London at the end of the decade when her husband was fired. By 1874, her first husband (a compulsive gambler) and two of her three children were dead, she had married for the second time, to the watercolour painter Joseph Jopling, exhibited at the Royal Academy, and become a fixture in London’s artistic life. To enjoy any kind of success as a female painter at that time in Victorian Britain was an achievement, but even more remarkable was Louise Jopling’s lifelong campaign to improve women’s rights. She founded a professional art school for women in 1887, was a vigorous supporter of women’s suffrage, won voting rights for women at the Royal Society of Portrait Painters after being elected, fought for women to be able to paint from nude models, and became the first woman member of the Royal Society of British Artists in 1902. None of these doors were open to Anna Karenina as a member of St. Petersburg high society, although we learn in the course of the novel that she has a keen artistic sense, is a discerning reader, writes children’s fiction, and has a serious interest in education. Tolstoy’s wife Sofya similarly was never given the opportunity to fulfil her potential as a writer, photographer, and painter.

Louise Jopling was a beautiful woman, as is immediately apparent from Millais’ portrait. In her memoirs she describes posing for him in a carefully chosen embroidered black gown made in Paris, and consciously donning a charming and typically feminine expression to match. On the third day she came to sit for Millais, however, the two friends chanced to talk about something which made her feel indignant, and she forgot to wear her “designedly beautiful expression”. What was finally fixed in the portrait was a defiant and “rather hard” look, which, as she acknowledges, ultimately endowed her face with greater character. This peculiar combination of beauty and defiance is perhaps what most recalls the character of Anna Karenina, who in Part 5 of the novel confronts social prejudice and hypocrisy head-on by daring to attend the Imperial Opera in the full glare of the high society grandes dames who have rejected her.

Louise Jopling’s concern with how she is represented in her portrait, as a professional artist in her own right, as a painter’s model, and as a woman, also speaks to Tolstoy’s detailed exploration of the commodification and objectification of women in society and in art (as discussed by Amy Mandelker in her important study Framing Anna Karenina). It is for this reason that we encounter women in a variety of different situations (ranging from the unhappily married Anna, to the betrayed and careworn housewife Dolly, the young bride Kitty, the unmarried companion Varenka, and the former prostitute Marya), and three separate portraits of the heroine, seen from different points of view. Ernest Rhys interestingly compares Anna Karenina to “a woman’s Iliad” in his introduction to the 1914 Everyman’s Library edition of the novel. Another kind of woman’s Iliad could also be woven from the differing stories of some of Tolstoy’s intrepid early translators, amongst them Clara Bell, Isabel Hapgood, Rochelle S. Townsend, Constance Garnett, Louise Maude, Rosemary Edmonds, and Ann Dunnigan, to whom we owe a debt for paving the way.

The post A Woman’s Iliad? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSong of AmiensThe Fair Toxophilities and Daniel Deronda10 questions for Ammon Shea

Related StoriesSong of AmiensThe Fair Toxophilities and Daniel Deronda10 questions for Ammon Shea

August 24, 2014

Five facts about women’s involvement in organized crime

Women are involved in many organized illegal activities, albeit in small numbers. Editors Rosemary Gartner and Bill McCarthy of The Oxford Handbook on Gender, Sex, and Crime have compiled important information about women’s involvement in organized crime. Here they’ve adapted some information from “Organized Crime: The Gender Constraints of Illegal Markets” by Valeria Pizzini-Gambetta (Chapter 23).

(1) Most organized crime falls into one of two distinct types – illegal industries and mafias — both of which are dominated by males. Illegal industries supply illegal commodities through networks that vary in shape and size according to the circumstances of the trade. Mafias are club-like groups defined by ritual entry, a territorially-based hierarchical structure, and the supply of extra-legal governance to illegal markets. Both types of activity have been dominated by men, but there are many historical examples where women also participated, particularly in illegal industries.

(2) There is historical evidence of mixed-gender groups of criminals. Several mixed-gender groups of criminals roamed the Netherlands and the German territories in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Some pirate groups in the Far East were also mixed-gender marauding communities. In the early nineteenth century, Chinese pirates were ruled by the widow of their late general for several years. They formed a nation at sea, in which junks were gender-mixed, with female captives and family members on board. Buccaneer and pirate communities in the Caribbean golden age were essentially gender-exclusive; nevertheless, a handful of women entered the world of sea piracy through love relationships, cross-dressing, and kinship.

(3) Female entrepreneurs have been involved in running illegal businesses in the modern period. Marcellina Cardena, Marie Debrizzi, and Stephanie St. Clair were part of the gender and racial blend that animated gambling in Harlem until the 1930s. These so-called “bankers” needed only cash and a network of policy vendors to conduct illegal gambling. They hired other women to go door to door to take dime bets in exchange for a small percentage of the win from both bankers and winners. Women have also played important roles in the drug trade. In Latin America, Eva Silverstein (arrested in 1917), Sadie Stock (arrested in 1920), and Maria Wendt (arrested in 1936) were part of international rings of traffickers that imported opium and its derivatives from China and Mexico for export to the United States and Europe. More recently, Mahalaxmi Papamani and her network of Tamil female neighbors managed an important share of the drug retailing market in Mumbai in the 1980s.

(4) Although less common, women have also formed gender-exclusive crime groups. The “Forty Elephants” was an all-female group that flourished in the shadow of The Elephant and Castle male gang in London throughout the nineteenth century and well into the 1950s. The young women of this group specialized in shoplifting in the West End. Their sorority was hierarchical and a “queen” was in charge of distributing targets among the group members.

(5) Women often play “traditional” female roles in organized crime. Women have been relatively less involved as active offenders in mafias; instead, traditional female roles remain the most important resource for this type of organized crime. Intelligence gathering, turf monitoring, and hiding illegal commodities or weapons are tasks that can be accomplished as part of women’s ordinary daily routines. In most groups, women are trusted auxiliaries in a number of capacities at times that are critical for the functioning of the group’s operations.

Headline image: Person in the Shadows with handgun, on natural wooden background. © Alexei Novikov via iStockphoto.

The post Five facts about women’s involvement in organized crime appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive important facts about honor killingsHate crime and community dynamicsAkbar Jehan and the dialectic of resistance and accommodation

Related StoriesFive important facts about honor killingsHate crime and community dynamicsAkbar Jehan and the dialectic of resistance and accommodation

Research replication in social science: reflections from Nathaniel Beck

Introduction from Michael Alvarez, co-editor of Political Analysis:Questions about data access, research transparency and study replication have recently become heated in the social sciences. Professional societies and research journals have been scrambling to respond; for example, the American Political Science Association established the Data Access and Research Transparency committee to study these issues and to issue guidelines and recommendations for political science. At Political Analysis, the journal that I co-edit with Jonathan N. Katz, we require that all of the papers we publish provide replication data, typically before we send the paper to production. These replication materials get archived at the journal’s Dataverse, which provides permanent and easy access to these materials. Currently we have over 200 sets of replication materials archived there (more arriving weekly), and our Dataverse has seen more than 13,000 downloads of replication materials.

Due to the interest in replication, data access, and research transparency in political science and other social sciences, I’ve asked a number of methodologists who have been front-and-center in political science with respect to these issues to provide their thoughts and comments about what we do in political science, how well it has worked so far, and what the future might hold for replication, data access, and research transparency. I’ll also be writing more about what we have done at Political Analysis.

The first of these discussions are reflections from Nathaniel Beck, Professor of Politics at NYU, who is primarily interested in political methodology as applied to comparative politics and international relations. Neal is a former editor of Political Analysis, chairs our journal’s Advisory Board, and is now heading up the Society for Political Methodology’s own committee on data access and research transparency. Neal’s reflections provide some interesting perspectives on the importance of replication for his research and teaching efforts, and shed some light more generally on what professional societies and journals might consider for their policies on these issues.

Research replication in social science: reflections from Nathaniel Beck

Replication and data access has become a hot topic throughout the sciences. As a former editor of Political Analysis and the chair of the Society for Political Methodology‘s Data Access and Research Transparency (DA-RT) committee, I have been thinking about these issues a lot lately. But here I simply want to share a few recent experiences (two happy, one at this moment less so) which have helped shape my thinking on some of these issues. I note that in none of these cases was I concerned that the authors had done anything wrong, though of course I was concerned about the sensitivity of results to key assumptions.

The first happy experience relates to an interesting paper on the impact of having an Islamic mayor on educational outcomes in Turkey by Meyerson published recently in Econometrica. I first heard about the piece from some students, who wanted my opinion on the methodology. Since I am teaching a new (for me) course on causality, I wanted to dive more deeply into the regression discontinuity design (RDD) as used in this article. Coincidentally, a new method for doing RDD was presented at the recent (2014) meetings of the Society for Political Methodology by Facebook experiment on social contagion. The authors, in a footnote, said that replication data was available by writing to the authors. I wrote twice, giving them a full month, but heard nothing. I then wrote to the editor of PNAS who informed me that the lead author had both been on vacation and was overwhelmed with responses to the article. I am promised that the check is in the mail.

What editor wants to be bothered by fielding inquiries about replication data sets? What author wants to worry about going on vacation (and forgetting to set a vacation message)? How much simpler the world would have been for the authors, editor, and me, if PNAS simply followed the good practice of Political Analysis, the American Journal of Political Science, the Quarterly Journal of Political Science, Econometrica, and (if rumors are correct) soon the American Political Science Review of demanding that authors post, either on the journal web site or the journal Dataverse, all replication materials before an article is actually published? Why does not every journal do this?

A distant second best is to require authors to post their replication on their personal website. As we have seen from my experience, this often leads to lost or non-working URLs. While the simple solution here is the Dataverse, surely at a minimum authors should provide a standard Document Object Identifier (DOI) which should persist even as machine names change. But the Dataverse solution does this, and so much more, that it seems odd in this day and age for all journals not to use this solution. And we can all be good citizens and put our own pre-replication standard datasets on our own Dataverses. All of this is as easy (and maybe) easier than maintaining private data web pages, and one can rest easy that one’s data will be available until either Harvard goes out of business or the sun burns out.

Featured image: BalticServers data center by Fleshas CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Research replication in social science: reflections from Nathaniel Beck appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journalImproving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna AtkesonNew words, new dialogues

Related StoriesPublishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journalImproving survey methodology: a Q&A with Lonna AtkesonNew words, new dialogues

Song of Amiens

The horror of the First World War produced an extraordinary amount of poetry, both during the conflict and in reflection afterwards. Professor Tim Kendall’s anthology, Poetry of the First World War, brings together work by many of the well-known poets of the time, along with lesser-known writing by civilian and women poets and music hall and trench songs.

This is a poem from that anthology, ‘Song of Amiens’ by T. P. Cameron Wilson. Wilson had been a teacher until war broke out, when he enlisted. He served with the Sherwood Foresters, and was killed during the great German assault of March 1918.

Song of Amiens

Lord! How we laughed in Amiens!

For here were lights and good French drink,

And Marie smiled at everyone,

And Madeleine’s new blouse was pink,

And Petite Jeanne (who always runs)

Served us so charmingly, I think

That we forgot the unsleeping guns.

Lord! How we laughed in Amiens!

Till through the talk there flashed the name

Of some great man we left behind.

And then a sudden silence came,

And even Petite Jeanne (who runs)

Stood still to hear, with eyes aflame,

The distant mutter of the guns.

War memorial. By Russ Duparcq, via iStockphoto.

War memorial. By Russ Duparcq, via iStockphoto.Ah! How we laughed in Amiens!

For there were useless things to buy,

Simply because Irène, who served,

Had happy laughter in her eye;

And Yvonne, bringing sticky buns,

Cared nothing that the eastern sky

Was lit with flashes from the guns.

And still we laughed in Amiens,

As dead men laughed a week ago.

What cared we if in Delville Wood

The splintered trees saw hell below?

We cared . . . We cared . . . But laughter runs

The cleanest stream a man may know

To rinse him from the taint of guns.

- T. P. Cameron Wilson (1888-1918)

Featured image: 8th August, 1918 by Will Longstaff, Australian official war artist. Depicts a scene during the Battle of Amiens. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Song of Amiens appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Fair Toxophilities and Daniel Deronda10 questions for Ammon Shea10 questions for Garnette Cadogan

Related StoriesThe Fair Toxophilities and Daniel Deronda10 questions for Ammon Shea10 questions for Garnette Cadogan

Moral pluralism and the dismay of Amy Kane

There’s a scene in the movie High Noon that seems to me to capture an essential feature of our moral lives. Actually, it’s not the entire scene. It’s one moment really, two shots — a facial expression and a movement of the head of Grace Kelly.

The part she’s playing is that of Amy Kane, the wife of Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper). Amy Kane is a Quaker, and as such is opposed to violence of any kind. Indeed, she tells Kane she will marry him only if he resigns as marshal of Hadleyville and vows to put down his guns forever. He agrees. But shortly after the wedding Kane learns that four villains have plans to terrorize the town, and he comes to think it is he who must try to stop them. He picks up his guns in preparation to meet the villains, and in so doing breaks his vow to Amy.

Unrelenting in her passivism, Amy decides to leave Will. She boards the noon train out of town. Then she hears gunfire, and, just as the train is about to depart, she disembarks and rushes back. Meanwhile, Kane is battling the villains. He manages to kill two of them, but the remaining two have him cornered. It looks like the end for Kane. Then one of them falls.

Amy has picked up a gun and shot him in the back.

We briefly glimpse Amy’s face immediately after she has pulled the trigger. She is distraught, stricken. When the camera angle changes to a view from behind, we see her head fall with great sadness under the weight of what she’s done.

What’s going on with Amy at that moment? It’s possible, I suppose, that she believes she shouldn’t have shot the villain, that she let her emotions run away with her, that she thinks she did the wrong thing. But I doubt that’s it. More likely is that when Amy heard the gunshots she decided that the right thing for her to do was return to town and help her husband in his desperate fight. But why then is Amy dismayed? If she performed the action she thought was right, shouldn’t she feel only moral contentment with what she has done?

Studio publicity still of Grace Kelly for the film Rear Window (1954). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Studio publicity still of Grace Kelly for the film Rear Window (1954). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Grace Kelly could have played it differently. She could have whooped with delight at having offed the bad guy, perhaps dropping some “hasta la vista”-like catchphrase along the way. Or she could have set her ample square jaw in grim determination and gone after the remaining villain, signaling to us her decision to discard namby-pamby pacifism for the robust alternative of visceral western justice. But Amy Kane’s actual reaction is psychologically more plausible — and morally more interesting. While she believes she’s done what she had to do, she’s still dismayed. Why?

What Amy’s reaction shows, I believe, is that morality is pluralist, not monist.

Monistic moral theories tell us that there is one and only one ultimate moral end. If monism is true, in every situation it will always be at least theoretically possible to justify the right course of action by showing that everything of fundamental moral importance supports it. Jeremy Bentham is an example of a moral monist.

He held that pleasure is the single ultimate end. Another example is Immanuel Kant, who held that the single base for all of morality is the Categorical Imperative. According to monists,successful moral justification will always ends at a single point (even if they disagree among themselves about what that point is).

Pluralist moral theories, in contrast, hold that there is a multitude of basic moral principles that can come into conflict with each other. David Hume and W.D. Ross were both moral pluralists. They believed that various kinds of moral conflict can arise — justice can conflict with beneficence, keeping a promise can conflict with obeying the law, courage can conflict with prudence — and that there are no underlying rules that explain how such conflicts are to be resolved.

If Hume and Ross are right and pluralism is true, even after you have given the best justification for a course of action that it is possible to give, you may sometimes have to acknowledge that to follow that course will be to act in conflict with something of fundamental moral importance. Your best justification may fail to make all of the moral ends meet.

With that understanding of monism and pluralism on board, let’s now return to Grace Kelly as Amy Kane. Let’s return to the moment her righteous killing of the bad guy causes her to bow her head in moral remorse.

If we assume monism, Amy’s response will seem paradoxical, weird, in some way inappropriate. If there is one and only one ultimate end, then to think that a course of action is right will be to think that everything of fundamental importance supports it. And it would be paradoxical or weird — inappropriate in some way — for someone to regret doing something in line with everything of fundamental moral importance. If the moral justification of an action ends at a single point, then what could the point be of feeling remorse for doing it?

But Amy’s reaction is perfectly explicable if we take her to have a plurality of potentially-conflicting basic moral commitments. Moral pluralists will explain that Amy has decided that in this situation saving Kane from the villains has a fundamental moral importance that overrides the prohibition on killing, even while she continues to believe that there is something fundamentally morally terrible about killing. For pluralists, there is nothing strange about feeling remorse toward acting against something one takes to be of fundamental moral importance.

Indeed, feeling remorse in such a situation is just what we should expect. This is why we take Amy’s response to be apt, not paradoxical or weird. We think that she, like most of us, holds a plurality of fundamental moral commitments, one of which she rightly acted on even though it meant having to violate another.

The upshot is this. If you think Grace Kelly played the scene right — and if you think High Noon captures something about our moral lives that “hasta la vista”-type movies do not — then you ought to believe in moral pluralism.

Headline image: General Store Sepia Toned Wild West Town. © BCFC via iStock

The post Moral pluralism and the dismay of Amy Kane appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRadiology and Egyptology: insights from ancient lives at the British MuseumDispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War IReading demeanor in the courtroom

Related StoriesRadiology and Egyptology: insights from ancient lives at the British MuseumDispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War IReading demeanor in the courtroom

August 23, 2014

Dispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War I

In the first autumn of World War I, a German infantryman from the 25th Reserve Division sent this pithy greeting to his children in Schwarzenberg, Saxony.

11 November 1914

My dear little children!

How are you doing? Listen to your mother and grandmother and mind your manners.

Heartfelt greetings to all of you!

Your loving Papa

He scrawled the message in looping script on the back of a Feldpostkarte, or field postcard, one that had been designed for the Bahlsen cookie company by the German artist and illustrator Änne Koken. On the front side of the postcard, four smiling German soldiers share a box of Leibniz butter cookies as they stand on a grassy, sun-stippled outpost. The warm yellow pigment of the rectangular sweets seems to emanate from the opened care package, flushing the cheeks of the assembled soldiers with a rosy tint.

Änne Koken, color lithographic postcard (Feldpostkarte) designed for the H. Bahlsen Keksfabrik, Hannover, ca. November 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Änne Koken, color lithographic postcard (Feldpostkarte) designed for the H. Bahlsen Keksfabrik, Hannover, ca. November 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.German citizens posted an average of nearly 10 million pieces of mail to the front during each day of World War I, and German service members sent over 6 million pieces in return; postcards comprised well over half of these items of correspondence. For active duty soldiers, postage was free of charge. Postcards thus formed a central and a portable component of wartime visual culture, a network of images in which patriotic, sentimental, and nationalistic postcards formed the dominant narrative — with key moments of resistance dispatched from artists and amateurs serving at the front.

The first postcards were permitted by the Austrian postal service in 1869 and in Germany one year later. (The Post Office Act of 1870 allowed for the first postcards to be sold in Great Britain; the United States followed suit in 1873.) Over the next four decades, Germany emerged as a leader in the design and printing of colorful picture postcards, which ranged from picturesque landscapes to tinted photographs of famous monuments and landmarks. Many of the earliest propaganda postcards, at the turn of the twentieth century, reproduced cartoons and caricatures from popular German humor magazines such as Simplicissimus, a politically progressive journal that moved toward an increasingly reactionary position during and after World War I. Indeed, the majority of postcards produced and exchanged between 1914 and 1918 adopted a sentimental style that matched the so-called “hurrah kitsch” of German official propaganda.

Walter Georgi, Engineers Building a Bridge, 1915. Color lithographic postcard (Feldpostkarte) designed for the H. Bahlsen Keksfabrik, Hannover. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Walter Georgi, Engineers Building a Bridge, 1915. Color lithographic postcard (Feldpostkarte) designed for the H. Bahlsen Keksfabrik, Hannover. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Beginning in 1914, the German artist and Karlsruhe Academy professor Walter Georgi produced 24 patriotic Feldpostkarten for the Bahlsen cookie company in Hannover. In a postcard titled Engineers Building a Bridge (1915), a pair of strong-armed sappers set to work on a wooden trestle while a packet of Leibniz butter cookies dangle conspicuously alongside their work boots.

These engineering troops prepared the German military for the more static form of combat that followed the “Race to the Sea” in the fall of 1914; they dug and fortified trenches and bunkers, built bridges, and developed and tested new weapons — from mines and hand grenades to flamethrowers and, eventually, poison gas.

Georgi’s postcard designs for the Bahlsen company deploy the elegant color lithography he had practiced as a frequent contributor to the Munich Art Nouveau journal Jugend (see Die Scholle).In another Bahlsen postcard titled “Hold Out in the Roaring Storm” (1914), Georgi depicted a group of soldiers wearing the distinctive spiked helmets of the Prussian Army. Their leader calls out to his comrades with an open mouth, a rifle slung over his shoulder, and a square package of Leibniz Keks looped through his pinkie finger. In a curious touch that is typical of First World War German patriotic postcards, both the long-barreled rifles and the soldier’s helmets are festooned with puffy pink and carmine flowers.

These lavishly illustrated field postcards, designed by artists and produced for private industry, could be purchased throughout Germany and mailed, traded, or collected in albums to express solidarity with loved ones in active duty. The German government also issued non-pictorial Feldpostkarten to its soldiers as an alternate and officially sanctioned means of communication. For artists serving at the front, these 4” x 6” blank cards provided a cheap and ready testing ground at a time when sketchbooks and other materials were in short supply. The German painter Otto Schubert dispatched scores of elegant watercolor sketches from sites along the Western Front; Otto Dix, likewise, sent hundreds of illustrated field postcards to Helene Jakob, the Dresden telephone operator he referred to as his “like-minded companion,” between June 1915 and September 1918. These sketches (see Rüdiger, Ulrike, ed. Grüsse aus dem Krieg: die Feldpostkarten der Otto-Dix-Sammlung in der Kunstgalerie Gera, Kunstgalerie Gera 1991) convey details both minute and panoramic, from the crowded trenches to the ruined fields and landmarks of France and Belgium. Often, their flip sides contain short greetings or cryptic lines of poetry written in both German and Esperanto.

Dix enlisted for service in 1914 and saw front line action during the Battle of the Somme, in August 1916, one of the largest and costliest offensives of World War I that spanned nearly five months and resulted in casualties numbering more than one million. By September of 1918, the artist had been promoted to staff sergeant and was recovering from injuries at a field hospital near the Western Front. He sent one of his final postcard greetings to Helene Jakob on the reverse side of a self-portrait photograph, in which he stands with visibly bandaged legs and one hand resting on his hip. Dix begins the greeting in Esperanto, but quickly shifts to German to report on his condition: “I’ve been released from the hospital but remain here until the 28th on a course of duty. I’m sending you a photograph, though not an especially good one. Heartfelt greetings, your Dix.” Just two months later, the First World War ended in German defeat.

The post Dispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War I appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRemembering 100 years: Fashion and the outbreak of the Great WarThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarThe First World War and the development of international law

Related StoriesRemembering 100 years: Fashion and the outbreak of the Great WarThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarThe First World War and the development of international law

Translating untranslatable words

For most language learners and lovers, translation is a hot topic. Should I translate new vocabulary into my first language? How can I say x in Japanese? Is this translated novel as good as the original? I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told that Pushkin isn’t Pushkin unless he’s read in Russian, and I have definitely chastised my own students for anxiously writing out lengthy bilingual wordlists: Paola, you’ll only remember trifle if you learn it in context!

Context-based learning aside, I’m all for translation: without it, we wouldn’t understand each other. However, I remain unconvinced that untranslatable words really exist. In fact, I wrote a blog post on some of my favorite Russian words that touched on this very topic. Looking at the responses it received both here and in the Twitterverse, I decided to set out on my own linguistic odyssey: could I wrap my head around ‘untranslatable’ once and for all?

It’s all Greek to me!

Many lovely people of the internet are in accordance: untranslatable words are out there, and they’re fascinating. A quick Google brings up articles, listicles, and even entire blogs on the matter. Goya, jayus, dépaysement — all wonderful words that neatly convey familiar concepts, but also “untranslatable” words that appear accompanied by an English definition. This English definition may well be longer and more complex than the foreign-language word itself (Oxford translates dépaysement as both “change of scenery” and “disorientation,” for example), but it is arguably a translation nonetheless. A lot of the coffee-break reads popping up on the internet don’t contain untranslatable words, but rather language lacking a word-for-word English equivalent. Is a translation only a translation if it is eloquent and succinct?

Genoveva in der Waldeinsamkeit by Hans Thoma. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Genoveva in der Waldeinsamkeit by Hans Thoma. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Translation vs. definition

When moving from one language to another, what’s a translation and what’s a definition — and is there a difference? Brevity seems to matter: the longer the translation, the more likely it is to be considered a definition. Does this make it any less of a translation? When we translate, we “express sense;” when we define, we “state or describe exactly the nature, scope, or meaning.” If I say that toska (Russian) means misery, boredom, yearning, and anguish, is that a definition or a translation? Or even both? It is arguably a definition — yet all of the nouns above could, dependent on context, be used as the best translation.

If we are to talk about what is translatable and what isn’t, we need to start talking about language, rather than words. The Spanish word duende often features in lists of untranslatable words: it refers to the mystical power by which an artist or artwork captivates its audience. Have I just defined duende, or translated it? I for one am not so sure anymore, but I do know that in context, its meaning is clear: un cantante que tiene duende becomes “a singer who has a certain magic about him.” The same goes for the French word dépaysement. By itself, dépaysement can mean many things, but in the phrase les touristes anglais recherchent le dépaysement dans les voyages dans les îles tropicales, it’s clear from context that the sense required is “change of scene” (“English tourists look for a change of scene on holidays to tropical islands”). Does this mean that all words are translatable, as long they are in context?

Saying no to stereotypes

One of my biggest beefs with untranslatable word memes is the suggestion that these linguistic treasure troves are loaded with cultural inferences. Most of the time they’re twee, rather than offensive: for example, the German word Waldeinsamkeit means “the feeling of being alone in the woods.” Gosh, how typical of those woodland-loving Germans, wandering around the Black Forest enjoying oneness with nature! The existence of an “untranslatable” word hints at some kind of cultural mystery that is beyond our comprehension — but does the lack of a word-for-word translation of Waldeinsamskeit mean that no English speaker (or French speaker, or Mandarin speaker) can understand the concept of being alone in the woods? Of course not! However, these misinterpretations of Waldeinsamskeit, Schadenfreude, Backpfeifengesicht et al. make me think: what about those words that really do have a particular cultural resonance? Can we really translate them?

Excuse me, can I borrow your word?

Specialized translation throws up its own variety of “untranslatable” words. For example, if you are translating a text about the Russian banya into a language where steam baths are not the norm, how do you go about translating nouns such as venik (веник)? A venik is a broom, but in the context of the banya it is a collection of leafy twigs (rather than dried twigs) that is used to beat those enjoying the restorative steam. Translating venik as “broom” here would be wildly inaccurate (and probably generate some amusing mental images). The existence of a word-for-word translation doesn’t provide the whole answer if cultural context is missing. We can find examples of “untranslatable” words in relation to almost any culture-specific event, be it American Thanksgiving, Spanish bullfighting, or Balinese Nyepi. If I were to translate an article about bullfighting and retain tienta rather than use “trial” (significantly less specific), does that mean that tienta in this context is really untranslatable?

So what has all this research taught me about translation? Individual words may not be translatable, but language is. And as for the accuracy of the translation? That often depends on how we, as speakers of a particular language, attribute our own meaning. Sometimes, the “translation” just has to be Schadenfreude.

What do you think? Are some words untranslatable? Share your thoughts in the “Translation and language-learning” board of the Oxford Dictionaries Community.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Featured image: Timeless Books by Lin Kristensen. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Translating untranslatable words appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesQuebec French and the question of identityHow I created the languages of Dothraki and Valyrian for Game of ThronesReading demeanor in the courtroom

Related StoriesQuebec French and the question of identityHow I created the languages of Dothraki and Valyrian for Game of ThronesReading demeanor in the courtroom

Remembering the slave trade and its abolition

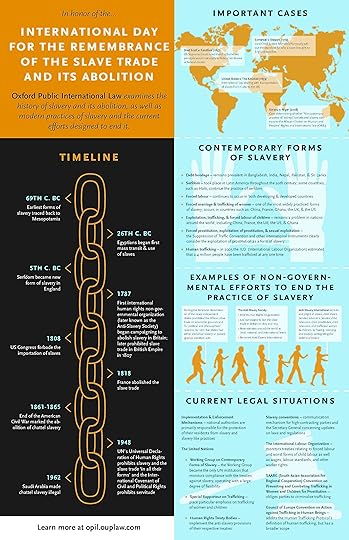

On August 23rd the United Nations observes the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. In honor of this day, we examine the history of slavery and its abolition, and shed light on contemporary slavery practices.

View the infographic below to learn more, or open it as a PDF to click through to freely available content from across our public international law resources.

Download a PDF copy of the infographic

Headline image credit: Photo by orythys, Public Domain CCo via pixabay

The post Remembering the slave trade and its abolition appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War IAn Oxford Companion to being the DoctorEarly Modern Porn Wars

Related StoriesDispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War IAn Oxford Companion to being the DoctorEarly Modern Porn Wars

Reading demeanor in the courtroom

When it comes to assessing someone’s sincerity, we pay close attention to what people say and how they say it. This is because the emotion-based elements of communication are understood as partially controllable and partially uncontrollable. The words that people use tend to be viewed as relatively controllable; in contrast, rate of speech, tone of voice, hesitations, and gestures (paralinguistic elements) have tended to be viewed as less controllable. As a result of the perception of speakers’ lack of control over them, the meanings conveyed via paralinguistic channels have tended to be understood as providing more reliable evidence of a speaker’s inner state.

Paradoxically, the very elements that are viewed as so reliable are consistent with multiple meanings. Furthermore, people often believe that their reading of another person’s demeanor is the correct one. Many studies have shown that people – judges included – are notoriously bad at assessing the meaning of another person’s affective display. Moreover, some research suggests that people are worse at this when the ethnic background of the speaker differs from their own – not an uncommon situation when defendants address federal judges, even in 2014.

The element of defendants’ demeanor is not only problematic for judges; it is also problematic for the record of the proceedings. This is due to courtroom reporters’ practice of reporting the words that are spoken and excluding input from paralinguistic channels.

One of the original Victorian Courtrooms at the Galleries of Justice Museum. Photo by Fayerollinson. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the original Victorian Courtrooms at the Galleries of Justice Museum. Photo by Fayerollinson. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.I observed one case in which this practice had the potential for undermining the integrity of the sentencing hearing transcript. In this case, the defendant lost her composure while making her statement to the court. The short, sob-filled “sorry” she produced mid-way through her statement was (from my perspective) clearly intended to refer to her preceding tears and the delays in her speech. The official transcript, however, made no reference to the defendant’s outburst of emotion, thereby making her “sorry” difficult to understand. Without the clarifying information about what was going on at the time – namely, the defendant’s crying — her “sorry” could conceivably be read as part of her apology to the court for her crime of robbing a bank.

Not distinguishing between apologies for the crime and apologies for a problem with delivery of one’s statement is a problem in the context of a sentencing hearing because apologies for crimes are understood as an admission of guilt. If the defendant had not already apologized earlier, the ambiguity of the defendant’s words could have significant legal ramifications if she sought to appeal her sentence or to claim that her guilty plea was illegal.

As the above example illustrates, the exclusion of meaning that comes from paralinguistic channels can result in misleading and inaccurate transcripts. (This is one reason why more and more police departments are video-recording confessions and witness statements.) If a written record is to be made of a proceeding, it should preserve the significant paralinguistic elements of communication. (Following the approach advocated by Du Bois 2006, one can do this with varying amounts of detail. For example, the beginning and ending of crying-while-talking can be indicated with double angled brackets, e.g., < < sorry > >.) Relatedly, if a judge is going to use elements of a defendant’s demeanor in court to increase a sentence, the judge should be prepared to defend this decision and cite the evidence that was employed. Just as a judge’s decision based on the facts of the case can be challenged, a decision based on demeanor evidence deserves the same scrutiny.

The post Reading demeanor in the courtroom appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTranslating untranslatable wordsRemembering the slave trade and its abolitionNew words, new dialogues

Related StoriesTranslating untranslatable wordsRemembering the slave trade and its abolitionNew words, new dialogues

August 22, 2014

New words, new dialogues

In August 2014, OxfordDictionaries.com added numerous new words and definitions to their database, and we invited a few experts to comment on the new entries. Below, Janet Gilsdorf, President-elect of Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, discusses anti-vax and anti-vaxxer. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Oxford Dictionaries or Oxford University Press.

It’s beautiful, our English language — fluid and expressive, colorful and lively. And it’s changeable. New words appear all the time. Consider “selfie” (a noun), “problematical” (an adjective), and “Google” (a noun that turned into verbs.) Now we have two more: “anti-vax” and “anti-vaxxer.” (Typical of our flexible vernacular, “anti-vaxxer” is sometimes spelled with just one “x.”) I guess inventing these words was inevitable; a specific, snappy short-cut was needed when speaking about something as powerful and almost cult-like as the anti-vaccine movement and its disciples.

When we string our words together, either new ones or the old reliables, we find avenues for telling others of our joys and disappointments, our loves and hates, our passions and indifferences, our trusts and distrusts, and our fears. The words we choose are windows into our minds. Searching for the best terms to use helps us refine our thinking, decide what, exactly, we are contemplating, and what we intend to say.

Embedded in the force of the new words “anti-vax” and “anti-vaxxer” are many of the tales we like to tell: our joy in our children, our disappointment with the world; our love of independence and autonomy, our hate of things that hurt us or those important to us; our passion for coming together in groups, our indifference to the worries of strangers; our trust, fueled by hope rather than evidence, in whatever nutty things may sooth our anxieties, our distrust in our sometimes hard-to-understand scientific, medical, and public health systems; and, of course, our fears.

Fear is usually a one-sided view. It is blinding, so that in the heat of the moment we aren’t distracted by nonsense (the muddy foot prints on the floor, the lawn that needs mowing) and can focus on the crisis at hand. Unfortunately, fear may also prevent us from seeing useful things just beyond the most immediate (the helping hands that may look like claws, the alternatives that, in the end, are better).

Image credit: Vaccination. © Sage78 via iStockphoto.

Image credit: Vaccination. © Sage78 via iStockphoto.For the anti-vax group, fear is the gripping terror that awful things will happen from a jab (aka shot, stick, poke). Of course, it isn’t the jab that’s the problem. Needles through the skin, after all, deliver medicines to cure all manner of illnesses. For anti-vaxxers, the fear is about the immunization materials delivered by the jab. They dread the vaccine antigens, the molecules (i.e. pieces of microbes-made-safe) that cause our bodies to think we have encountered a bad germ so we will mount a strong immune response designed to neutralize that bad germ. What happens after a person receives a vaccine is, in effect, identical to what happens after we recover from a cold or the flu — or anthrax, smallpox, or possibly ebola (if they don’t kill us first). Our blood is subsequently armed with protective immune cells and antibodies so we don’t get infected with that specific virus or bacterium again. Same for measles, polio, or chicken-pox. If we either get those diseases (which can be bad) or the vaccines to prevent them (which is good), our immune system can effectively combat these viruses in future encounters and prevent infections.

So what should we do with our new words? We can use them to express our thoughts about people who haven’t yet seen the value of vaccines. Hopefully, these new words will lead to constructive dialogues rather than attacks. Besides being incredibly valuable, words are among the most vicious weapons we have and we must find ways to use them responsibly.

The post New words, new dialogues appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRadiology and Egyptology: insights from ancient lives at the British MuseumThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarAn etymological journey paved with excellent intentions

Related StoriesRadiology and Egyptology: insights from ancient lives at the British MuseumThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarAn etymological journey paved with excellent intentions

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers