Oxford University Press's Blog, page 768

August 30, 2014

The burden of guilt and German politics in Europe

Since the outbreak of the First World War just over one hundred years ago, the debate concerning the conflict’s causes has been shaped by political preoccupations as well as historical research. Wartime mobilization of societies required governments to explain the justice of their cause, the “war guilt” clause of the treaty of Versailles became a focal point of German revisionist foreign policy in the 1920s, and the Fischer debate in West Germany in the 1960s took place against a backdrop of the Cold War and the efforts of German society to come to terms with the Nazi past. More recently critics of Sir Edward Grey’s foreign policy, such as Niall Ferguson and John Charmley, are writing in the context of intense debates about Britain’s relationship with Europe, while accounts that emphasise the strength of the great power peace before 1914 are informed in part by contemporary discussions of globalization and the improbability of a war between the world’s leading powers today – the conflict in the Ukraine notwithstanding.

The persistent political backdrop to debates about the origins of the war is evident in the reception of Christopher Clark’s best-selling work, The Sleepwalkers, particularly its resonance within Germany. Clark’s references to the Euro-crisis, 9/11, and the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s, dotted throughout the book, nod to the contemporary relevance of the collapse of the international system in 1914.

While Clark seeks to eschew debates about war guilt or responsibility, preferring to concentrate on the ‘how’ rather than the ‘why’, his conclusion contends that leaders in the capitals of the five Great Powers and in Belgrade bear somewhat equal responsibility for the war. This thesis has attracted considerable attention in Germany, where the last major public reckoning over the origins of the war took place in the 1960s, when Fritz Fischer’s thesis that German leaders planned for war from December 1912 and therefore bore the largest responsibility for its outbreak was the subject of intense and often vindictive debate. Fischer carried the day in the 1960s, but now Clark’s argument, comparative in a way that Fischer did not claim to be, has overturned what appeared to be a publicly accepted orthodoxy.

The centenary debate has also coincided with a particular moment in German political and cultural debate. The post-unification economic slowdown has now given way to a booming economy, while much of the rest of Europe is mired in austerity. In tandem with economic prosperity, German elites are displaying growing political confidence as Europe’s dominant state.

In this context Clark’s thesis about shared responsibility for the war has been read in two ways. One group, whose most notable advocates include Thomas Weber (Aberdeen/Harvard) and Dominik Geppert (Bonn), argue that the ongoing belief in German ‘war guilt’ is an historic fiction that damages both German and European politics. It has contributed to the unwillingness of successive German governments to take on greater leadership within Europe. The marginalization of the German national interest after 1945, they claim, is partly the product of a misinformed reading of history that holds the pursuit of the German national interest as responsible for two catastrophic global conflicts. This has resulted in a damaging approach to European politics, which holds that the national is inherently opposed to the European interest. By neglecting the national interest German leaders are creating instability within Europe and alienating many German citizens from participating in a European project that must take account of national diversity. Hence they welcome Clark’s book and the enormous public interest it has aroused in Germany.

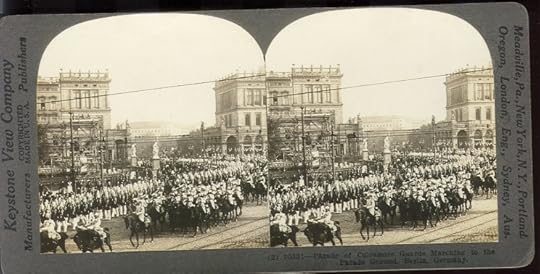

Parade of Cuirassier Guards Marching to the Parade Ground, Berlin, Germany. Keystone View Company, copyrighted Underwood & Underwood Public domain via via Wikimedia Commons.

Parade of Cuirassier Guards Marching to the Parade Ground, Berlin, Germany. Keystone View Company, copyrighted Underwood & Underwood Public domain via via Wikimedia Commons.However Clark’s thesis has not met with universal approval. Leading critics include Gerd Krumeich and John Röhl, both representatives of a generation of historians who came to the fore during and soon after the Fischer debate. They criticize Clark for downplaying the responsibility of German political and military leaders for the war, both by stressing the comparatively restrained character of German foreign policy up to the July crisis and by his criticisms of the aggressive nature of Russian, French, and British foreign policy before 1914. Not only do they take issue with Clark’s arguments, they also express concern that the ‘relativizing’ of German responsibility for the outbreak of the war will lead to a recrudescence of a more assertive German nationalism, undoing the successful integration of the Federal Republic into a community of democratic, European nations. From their perspective, a more assertive German nationalism, freed from the historic burden of war guilt, constitutes a potential danger.

The debate blends divergent generational perspectives on German national identity and European politics, as well as different interpretations of the sources and methodological approaches to studying the origins of the war. For the record, this author finds Clark’s account persuasive. On balance there is a greater risk in Germany not playing a leading role in European politics than there is of a re-assertion of a muscular German national interest and identity. Yet both groups may overestimate the significance of the “war guilt” in shaping perspectives in German and European politics. While the centenary has created a privileged space for the first world war in public discussion, the politics of history within Germany remain firmly fixed on the crimes of the Third Reich. When Europeans today think of Germany’s historical burden, they think primarily of the Nazi past. After all, disaffected protesters in countries hit by austerity after 2008 compared current German policies to those of the Third Reich, not the Kaiserreich. Grotesque and unfounded as the comparison was, it was striking that protesters did not think about Wilhelm II. While historians may revise their views of German responsibility for the First World War, no serious historian disputes the primacy of the Hitler’s regime in starting a genocidal war in Europe in 1939.

The post The burden of guilt and German politics in Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA preview of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarThe First World War and the development of international law

Related StoriesA preview of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingThe real story of allied nursing during the First World WarThe First World War and the development of international law

Time to see the end

Imagine that you’re watching a movie. You’re fully enjoying the thrill of different emotions, unexpected changes, and promising developments in the plot. All of a sudden, the projection is abruptly halted with no explanation whatsoever. You’re unable to learn how things unfold. You can’t see the end of the movie and you’re left with a sense of incompleteness you won’t ever be able to overcome.

Now imagine that movie is the existence of a human being which, out of the blue, is interrupted. Enforced disappearance cuts the life-flow of a person and it’s often impossible to discover how it truly ends. The secrecy that shrouds the fate of the disappeared is the distinctive element of this heinous practice and differentiates it from other crimes. All that you can imagine is that the end is not likely to be a happy one, but you will never give up hope. The impossibility to unveil the truth paralyses also the life of family members, friends, colleagues, and, to a certain extent, of society at large. If you don’t see the end, you’re unable to move on. You can’t grieve. You can’t rejoice. You’re trapped between hope and despair.

Today is the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances. Besides commemorating thousands of human beings who have been subjected to enforced disappearance throughout the world and honouring the memory of brave family members and human rights defenders who continue to combat against this scourge, is there anything to celebrate?

While the UN General Assembly decided to observe this Day beginning in 2011, associations of relatives of disappeared persons in Latin America had been doing so since 1981.

Over more than 30 years much has been done to eradicate enforced disappearance, both at domestic and international levels. Specific human rights bodies, such as the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) and the Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED) have been established. Legal instruments, both of international human rights law and of international criminal law, deal with this crime in-depth and establish detailed obligations and severe sanctions. Regional human rights courts and UN Treaty Bodies have developed a rich, although not always coherent, jurisprudence. Domestic courts have delivered some landmark sentences, holding perpetrators accountable.

Ceremony organised by the Asian Federation against Involuntary Disappearances, held in Manila on 30 August 2009, to commemorate the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances. Photo by Gabriella Citroni.

Ceremony organised by the Asian Federation against Involuntary Disappearances, held in Manila on 30 August 2009, to commemorate the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances. Photo by Gabriella Citroni.However, much remains to be done. First, the phenomenon has evolved: once mainly perpetrated in the context of military dictatorships, nowadays it is committed also under supposedly democratic regimes, and is being used to counter terrorism, to fight organised crime, or to suppress legitimate movements of civil protest. Enforced disappearance is practiced in a widespread and systematic manner in complex situations of internal armed conflict, as highlighted, among others, in the recent report “Without a Trace” concerning enforced disappearances in Syria.

During its latest session, held in February 2014, the WGEID transmitted 87 newly reported cases of enforced disappearance to 11 states. More than 43,000 cases, committed in a total of 84 states, remain under the WGEID’s active consideration.

Against this discouraging scenario, less than 15 states have codified enforced disappearance as an autonomous offence under their criminal legislation and thus lack the adequate legal framework to tackle this crime. Only a handful of states have adopted specific measures to regulate the legal situation of disappeared persons in field such as welfare, financial matters, family law and property rights. This causes additional anguish to the relatives of the disappeared and may also hamper investigation and prosecution. Amnesty laws or similar measures that have the effect of exempting perpetrators from any criminal proceedings or sanctions are in force in various countries and are in the process of being adopted in others. Recourse to military tribunals is often used to grant impunity.

Relatives of disappeared men from Lebanon and Algeria taking part in a gathering organised by the

Fédération Euro-méditerranéenne contre les disparitions forcées

in Beirut on 21 February 2013. Photo by Gabriella Citroni.

Relatives of disappeared men from Lebanon and Algeria taking part in a gathering organised by the

Fédération Euro-méditerranéenne contre les disparitions forcées

in Beirut on 21 February 2013. Photo by Gabriella Citroni.States do not seem to be proactive in engaging in a serious struggle against enforced disappearance at the international level either. Opened for signature in February 2007, the International Convention on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance has so far been ratified by 43 states, out of which only 18 have recognized the competence of the CED to receive and examine individual and inter-state communications.

Furthermore, states often fail to cooperate with international human rights mechanisms, hindering the fact-finding process, and proving reluctant in the enforcement of judgments. On their part, some of these international mechanisms, such as the European Court of Human Rights, narrowed their jurisprudence on enforced disappearance, undertaking a particularly restrictive approach when assessing their competence ratione temporis, when evaluating states’ compliance with their positive obligations to investigate on cases of disappearance, prosecute and sanction those responsible, and when awarding measures of redress and reparation.

One may wonder why 30 August was chosen by relatives of disappeared persons as the International Day against this crime. Purportedly, they picked a random date. They didn’t want it to be related to the enforced disappearance of anyone in particular: anyone can be subjected to enforced disappearance, anytime, and anywhere.

That was the idea back in 1981. Sadly, it still seems to be the case in 2014. It’s about time the obligations set forth in international treaties on enforced disappearance are duly implemented, domestic legal frameworks are strengthened, and legislative or procedural obstacles to investigation and prosecution are removed. It’s time to see the end of the movie. The end of enforced disappearance.

The post Time to see the end appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy referendum campaigns are crucialCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?A preview of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

Related StoriesWhy referendum campaigns are crucialCan changing how prosecutors do their work improve public safety?A preview of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

War poetry across the centuries

‘Poetry’, Wordsworth reminds us, ‘is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’, and there can be no area of human experience that has generated a wider range of powerful feelings than war: hope and fear; exhilaration and humiliation; hatred—not only for the enemy, but also for generals, politicians, and war-profiteers; love—for fellow soldiers, for women and children left behind, for country (often) and cause (occasionally).

So begins Jon Stallworthy’s introduction to his recently edited volume The New Oxford Book of War Poetry. The new selection provides improved coverage of the two World Wars and the Vietnam War, and new coverage of the wars of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Below is an extract of two poems from the collection.

JOHN MILTON 1608–1674 On the Late Massacre in Piedmont* (1673)

Avenge, O Lord, thy slaughtered saints, whose bones

Lie scattered on the Alpine mountains cold,

Even them who kept thy truth so pure of old

When all our fathers worshipped stocks and stones,

Forget not; in thy book record their groans

Who were thy sheep and in their ancient fold

Slain by the bloody Piedmontese that rolled

Mother with infant down the rocks. Their moans

and his Latin secretary, John Milton.

The vales redoubled to the hills, and they

To Heaven. Their martyred blood and ashes sow

O’er all th’ Italian fields where still doth sway

The triple tyrant, that from these may grow

A hundredfold, who having learnt thy way,

Early may fly the Babylonian woe.

* The heretical Waldensian sect, which inhabited northern Italy (Piedmont) and southern France, held beliefs compatible with Protestant doctrine. Their massacre by Catholics in 1655 was widely protested by Protestant powers, including Oliver Cromwell and his Latin secretary, John Milton.

LOUIS SIMPSON The Heroes (1955)

I dreamed of war-heroes, of wounded war-heroes

With just enough of their charms shot away

To make them more handsome. The women moved nearer

To touch their brave wounds and their hair streaked with gray.

I saw them in long ranks ascending the gang-planks;

The girls with the doughnuts were cheerful and gay.

They minded their manners and muttered their thanks;

The Chaplain advised them to watch and to pray.

They shipped these rapscallions, these sea-sick battalions

To a patriotic and picturesque spot;

They gave them new bibles and marksmen’s medallions,

Compasses, maps, and committed the lot.

A fine dust has settled on all that scrap metal.

The heroes were packaged and sent home in parts

To pluck at a poppy and sew on a petal

And count the long night by the stroke of their hearts.

Image credit: Menin Gate, Ypres, Belgium. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post War poetry across the centuries appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSong of AmiensWhat can poetry teach us about war?A back-to-school reading list of classic literature

Related StoriesSong of AmiensWhat can poetry teach us about war?A back-to-school reading list of classic literature

August 29, 2014

A preview of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

In a few months, Troy and I hope to welcome you all to the 2014 Oral History Association (OHA) Annual Meeting, “Oral History in Motion: Movements, Transformations, and the Power of Story.” This year’s meeting will take place in our lovely, often frozen hometown of Madison, Wisconsin, from 8-12 October 2014. I am sure most of you have already registered and booked your hotel room. For those of you still dragging your feet, hopefully these letters from OHA Vice President/President Elect Paul Ortiz and Program Committee co-chairs Natalie Fousekis and Kathy Newfont will kick you into gear.

* * * * *

Madison, Wisconsin. The capitol city of the Badger State evokes images of social movements of all kinds. This includes the famed “Wisconsin Idea,” a belief put forth during an earlier, tumultuous period of American history that this place was to become a “laboratory for democracy,” where new ideas would be developed to benefit the entire society. In subsequent years, Madison became equally famous for the Madison Farmers Market, hundreds of locally-owned businesses, live music, and a top-ranked university. Not to mention world-famous cafes, microbreweries, and brewpubs! [Editor’s note: And fried cheese curds!] Our theme, “Oral History in Motion: Movements, Transformations and the Power of Story,” is designed to speak directly to the rich legacies of Wisconsin and the upper Midwest, as well as to the interests and initiatives of our members. Early on, we decided to define “movements” broadly — and inclusively — to encompass popular people’s struggles, as well as the newer, exciting technological changes oral history practitioners are implementing in our field.

Creating this year’s conference has been a collaborative effort. Working closely with the OHA executive director’s office, our program and local arrangements committees have woven together an annual meeting with a multiplicity of themes, as well as an international focus tied together by our belief in the transformative power of storytelling, dialog, and active listening. Our panels also reflect the diversity of our membership’s interests. You can attend sessions ranging from the historical memories of the Haitian Revolution and the future of the labor movement in Wisconsin to the struggles of ethnic minority refugees from Burma. We’ll explore the legacies left by story-telling legends like Pete Seeger and John Handcox, even as we learn new narratives from Latina immigrants, digital historians and survivors of sexual abuse.

Based on the critical input we’ve received from OHA members, this year’s annual meeting in will build on the strengths and weaknesses of previous conferences. New participants will have the opportunity to be matched with veteran members through the OHA Mentoring Program. We will also invite all new members to the complimentary Newcomers’ Breakfast on Friday morning. Building on its success at last year’s annual meeting, we are also holding Interest Group Meetings on Thursday, in order to help members continue to knit together national—and international—networks. The conference program features four hands-on oral history workshops on Wednesday, and a “Principles and Best Practices for Oral History Education (grades 4-12)” workshop on Saturday morning. This year’s plenary and special sessions are also superb.

With such an exciting program, it is little wonder that early pre-registration was so high! I hope that you will join us in Madison, Wisconsin for what will be one of the most memorable annual meetings in OHA history!

In Solidarity,

Paul Ortiz

OHA Vice President/President Elect

* * * * *

The 2014 OHA Annual Meeting in Madison, Wisconsin is shaping up to be an especially strong conference. The theme, “Oral History in Motion: Movements, Transformations and the Power of Story,” drew a record number of submissions. As a result, the slate of concurrent sessions includes a wide variety of high quality work. We anticipate that most conference-goers will, even more so than most years, find it impossible to attend all sessions that pique their interest!

The local arrangements team in Madison has done a wonderful job lining up venues for the meeting and its special sessions, including sites on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus, the Wisconsin Historical Society and the Madison Public Library. The meeting will showcase some of Madison’s richest cultural offerings. For instance, we will open Wednesday evening in Sterling Hall with an innovative, oral-history inspired performance on the 1970 bomb explosion, which proved a key flashpoint in the Vietnam-era anti-war movement. After Thursday evening’s Presidential Reception, we will hear a concert by Jazz Master bassist Richard Davis — who will also do a live interview Saturday evening.

In keeping with our theme, many of our feature presentations will address past and present fights for social and political change. Thursday afternoon’s mixed-media plenary session will focus on the music and oral poetry of sharecropper “poet laureate” John Handcox, whose songs continue to inspire a broad range of justice movements in the U.S. and beyond. Friday morning’s “Academics as Activists” plenary session will offer a report from the front lines of contemporary activism. It will showcase an interdisciplinary panel of scholars who have emerged as leading voices in recent pushes for social change in Wisconsin, North Carolina and nationwide. The Friday luncheon keynote will feature John Biewen of Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, who has earned recognition for—among other things—his excellent work on disadvantaged groups. Finally, on Friday evening we will screen Private Violence, a film featured at this year’s Sundance festival. Private Violence examines domestic violence, long a key concern in women’s and children’s rights movements. The event will be hosted by Associate Producer Malinda Maynor Lowery, who is also Director of the University of North Carolina’s Southern Oral History Program.

Join us for all this and much more!

Natalie Fousekis and Kathy Newfont

Program Committee

* * * * *

See you all in October!

Headline image credit: Resources of Wisconsin. Edwin Blashfield’s mural “Resources of Wisconsin”, Wisconsin State Capitol dome, Madison, Wisconsin. Photo by Jeremy Atherton. CC BY 2.0 via jatherton Flickr.

The post A preview of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOral history, historical memory, and social change in West Mount AiryRe-thinking the role of the regional oral history organizationSchizophrenia and oral history

Related StoriesOral history, historical memory, and social change in West Mount AiryRe-thinking the role of the regional oral history organizationSchizophrenia and oral history

The unfinished fable of the sparrows

Owls and robots. Nature and computers. It might seem like these two things don’t belong in the same place, but The Unfinished Fable of the Sparrows (in an extract from Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence) sheds light on a particular problem: what if we used our highly capable brains to build machines that surpassed our general intelligence?

It was the nest-building season, but after days of long hard work, the sparrows sat in the evening glow, relaxing and chirping away.

“We are all so small and weak. Imagine how easy life would be if we had an owl who could help us build our nests!”

“Yes!” said another. “And we could use it to look after our elderly and our young.”

“It could give us advice and keep an eye out for the neighborhood cat,” added a third.

Then Pastus, the elder-bird, spoke: “Let us send out scouts in all directions and try to find an abandoned owlet somewhere, or maybe an egg. A crow chick might also do, or a baby weasel. This could be the best thing that ever happened to us, at least since the opening of the Pavilion of Unlimited Grain in yonder backyard.”

The flock was exhilarated, and sparrows everywhere started chirping at the top of their lungs.

Only Scronkfinkle, a one-eyed sparrow with a fretful temperament, was unconvinced of the wisdom of the endeavor. Quoth he: “This will surely be our undoing. Should we not give some thought to the art of owl-domestication and owl-taming first, before we bring such a creature into our midst?”

Replied Pastus: “Taming an owl sounds like an exceedingly difficult thing to do. It will be difficult enough to find an owl egg. So let us start there. After we have succeeded in raising an owl, then we can think about taking on this other challenge.”

“There is a flaw in that plan!” squeaked Scronkfinkle; but his protests were in vain as the flock had already lifted off to start implementing the directives set out by Pastus.

Just two or three sparrows remained behind. Together they began to try to work out how owls might be tamed or domesticated. They soon realized that Pastus had been right: this was an exceedingly difficult challenge, especially in the absence of an actual owl to practice on. Nevertheless they pressed on as best they could, constantly fearing that the flock might return with an owl egg before a solution to the control problem had been found.

Headline image credit: Chestnut Sparrow by Lip Kee. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The unfinished fable of the sparrows appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA back-to-school reading list of classic literatureTell me a storyEthics of social networking in social work

Related StoriesA back-to-school reading list of classic literatureTell me a storyEthics of social networking in social work

A back-to-school reading list of classic literature

With carefree summer winding to a close, we’ve pulled together some reading recommendations to put you in a studious mood. Check out these Oxford World’s Classics suggestions to get ready for another season of books and papers. Even if you’re no longer a student, there’s something on this list for every literary enthusiast.

If you liked Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller, you should read Timon of Athens by William Shakespeare. Like Miller’s Willy Loman, Timon does not enjoy an especially happy life, although from the outside it seems as though he should. Timon once had a good thing going, but creates his own misery after lavishing his considerable wealth on friends. He eventually grows to despise humanity and the play follows his slow demise.

If you liked Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown, you should read The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. DuBois. Many argue that each of these texts should be required reading in all American schools. The Souls of Black Folk sheds light on a dark and shameful chapter of history, and of the achievements, triumphs, and continued struggles of African Americans against various obstacles in post-slavery society.

If you liked Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut, you should read The Iliad by Homer. Written 2,700 years ago, The Iliad may just be the original anti-war novel, paving the way for books like Slaughterhouse-Five. Illustrating in poetic form the brutality of war and the many types of conflict that often lead to it, the periodic glimpses of peace and beauty that punctuate the story only serve to bathe the painful realities of battle in an even starker light.

If you liked Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut, you should read The Iliad by Homer. Written 2,700 years ago, The Iliad may just be the original anti-war novel, paving the way for books like Slaughterhouse-Five. Illustrating in poetic form the brutality of war and the many types of conflict that often lead to it, the periodic glimpses of peace and beauty that punctuate the story only serve to bathe the painful realities of battle in an even starker light.

If you liked The Lord of the Flies by William Golding, you should read Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens. This 19th century Victorian novel explores the survival of good, utilizing England’s workhouse system and an orphaned boy as vehicles to navigate its themes. Dickens was considered the most talented among his contemporaries at employing suspense and violence as literary motifs. The result was a classic work of literature that continues to be a favorite for many.

If you liked The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood you should read The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne. If strong female protagonists are your thing you will probably enjoy Hester Prynne, who endures public scorn after bearing a child out of wedlock, and faces a punishment of wearing a red “A” to designate her offense. Despite the severe sentence, Hester maintains her faith and personal dignity, all while continuing to support herself and her baby—not an easy feat in a 17th century puritan community.

If you liked The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood you should read The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne. If strong female protagonists are your thing you will probably enjoy Hester Prynne, who endures public scorn after bearing a child out of wedlock, and faces a punishment of wearing a red “A” to designate her offense. Despite the severe sentence, Hester maintains her faith and personal dignity, all while continuing to support herself and her baby—not an easy feat in a 17th century puritan community.

If you liked One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, you should read The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. A colorful and eclectic assortment of characters make the best of a long and arduous pilgrimage by entertaining each other with tall tales of every genre from comedy to romance to adventure. If you enjoy certain aspects of Garcia Marquez’s writing, namely the fantasy elements and large cast of characters in One Hundred Years, you will probably appreciate those same characteristics in this novel, which was written 600 years ago and is still admired today.

If you liked The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, you should read My Antonia by Willa Cather. A similar tale of survival in a harsh new land, My Antonia provides the context for a romance between two mufti-dimensional characters. Cather offers readers a glimpse into settler life in the nascent stages of American history, with vivid landscape descriptions and universal themes of companionship and family as added bonuses.

If you liked The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, you should read My Antonia by Willa Cather. A similar tale of survival in a harsh new land, My Antonia provides the context for a romance between two mufti-dimensional characters. Cather offers readers a glimpse into settler life in the nascent stages of American history, with vivid landscape descriptions and universal themes of companionship and family as added bonuses.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS. – See more at: http://blog.oup.com/2014/08/daniel-de...

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS. – See more at: http://blog.oup.com/2014/08/daniel-de...

If you liked One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey, you should read The Trial by Franz Kafka. Psychological thrillers don’t get much better than The Trial, a book that incorporates various themes including guilt, responsibility, and power. Josef K. awakens one morning to find himself under arrest for a crime that is never explained to him (or to the reader). As he stands trial, Josef gradually crumbles under the psychological pressure and begins to doubt his own morality and innocence, showing how Kafka used ambiguity brilliantly as a device to create suspense.

Featured image: Timeless books by Lin Kristensen. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A back-to-school reading list of classic literature appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSong of AmiensThe Fair Toxophilities and Daniel DerondaA Woman’s Iliad?

Related StoriesSong of AmiensThe Fair Toxophilities and Daniel DerondaA Woman’s Iliad?

Viking reinventions

The Vikings are having a good year. In March a blockbuster exhibition opened in the new BP Gallery at the British Museum and tens of thousands have flocked to see the largest collection of Viking treasure ever to be displayed in the British Isles. The centrepiece of the exhibition is the Viking longship known as Roskilde 6. This was excavated from the edge of the Roskilde fjord in Denmark in 1997, during construction of an extension of the Ship Museum, being built to house the previous ships to be found. The curators must have felt they were in a Catch22 dilemma, with each attempt to enlarge the museum unearthing yet more potential exhibits. Their solution has been to flat-pack the largest longship, IKEA-style, and to send it round Europe in a travelling exhibition. It started its journey in Copenhagen in 2013, before coming to London; in the Autumn it will travel to Berlin. Having been fortunate to see both exhibitions I must admit to preferring the Danish version. This was in a darkened hall, with spotlights on the objects, and the longship was displayed against an animated backdrop of a turbulent sea, culminating on a raid on a coastal monastery. At 37m long Roskilde 6 is the longest Viking warship ever found, and it would have held a crew of 60 warriors. Although only 20% has actually survived, the steel frame, the darkened hall, and background soundtrack of the sea, helped bring it back to life and, standing at the stern looking down its full length, it left me completely awestruck. In London, by contrast, the ship was displayed in a fully illuminated white space, whilst the smaller objects are difficult to see, given the crowds jostling round the small cases. The Vikings seemed to lack mystery, which was a shame. I look forward to see what the Germans make of it, when Vikings opens in Berlin in October.

What both Danish and British versions share is a re-emphasis on the violence of the Viking Age. During the 1980s there was a little too much stress on Vikings as peaceful traders, and it was high time that the pendulum swung the other way. In Copenhagen prominence was given to the leg irons of slaves, and a warrior’s skull with grooved teeth, designed to give him a fearsome grin. In London a case displays the tumbled bodies, maybe the remains of a Viking raiding party, stripped naked and slaughtered on Ridgeway Hill, near Weymouth in Dorset, before their bloodied corpses were thrown into an open pit. One interpretation is that these were the victims of the St Brice’s Day massacre of 1002 AD, when Æthelred the Unready ordered all Danes living in England to be slaughtered as a savage reprisal against a fresh wave of raiders. One skeleton has deep cuts to the forearms as the unarmed man tried to shield himself against the sword blows raining down.

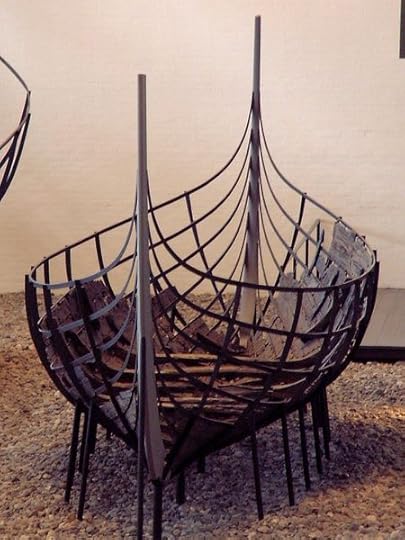

Skuldelev VI: Ein wikingerzeitliches Ruder- und Segelboot, das im Roskilde-Fjord in der Nähe von Skuldelev gefunden wurde. Photo by y Casiopeia. CC-BY-SA-2.0-de via Wikimedia Commons

Skuldelev VI: Ein wikingerzeitliches Ruder- und Segelboot, das im Roskilde-Fjord in der Nähe von Skuldelev gefunden wurde. Photo by y Casiopeia. CC-BY-SA-2.0-de via Wikimedia CommonsViking England was not always as cosy as visitors to the reconstructed Viking townscape in the Jorvik Viking Centre in York might have been led to believe. At a conference we held at the University of York in March this year, a recurring theme was the Viking Great Army that ravaged England, and Continental Europe, in the late ninth century. Unlike previous hit and run attacks on undefended coastal monasteries this much larger and highly mobile force made best use of the narrows draught of their longships to sail up the estuaries and English river system to penetrate deep inland. They were regularly reinforced by new war bands, eager for their own share of the loot, and ravaged southern and eastern England for over a decade, making camp each winter. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us where many of these camps were but until recently only one, at Repton in Derbyshire, the Viking base for the winter of 873-4 AD, had been investigated archaeologically, revealing a mass grave, as well as the graves of individual warriors (at least one of whom had met a brutal death), buried up against the walls of the royal Anglo-Saxon shrine to St Wystan. An adult male, buried with his sword, and a Thor’s hammer amulet around his neck, had been killed by a deep cut to his upper leg, and also a sword thrust through the eyepiece of his helmet, which penetrated deep into the eye socket. He may also have been disemboweled.

In recent years two more Viking camps have been located, both through the discovery by metal detector users, of Viking treasure, including concentrations of Arabic and Anglo-Saxon coins and Viking silver and gold, melted down into ingots. One of these is north of York and may be linked to the return of part of the Great Army to Tyneside, after they had departed from Repton in Derbyshire. The other, at Torksey in Lincolnshire, also on the banks of the River Trent, testifies to the winter camp of the previous year in 872-3 AD. A new project led by the Universities of Sheffield and York is now investigating the site, and we have already recorded more Arabic silver coins, or dirhams, than anywhere else in the British Isles. These finds reflect the loot that the war bands had collected, in Ireland, England, and previously in Francia, and which they were re-processing into portable treasure and status symbols whilst they over-wintered.

Every age seems to reinvent Vikings to reflect the spirit of its own age. In the 80s, as the European Common Market expanded, and free trade delivered new consumer goods to our homes we saw the Vikings as traders, bringing exotic goods from Europe and the Middle East to our shores. We have now had several reminders, from new discoveries of mass graves, fearsome warships, and looted possessions, that there was another side to their activities and that the arrival of the ‘dragon ships’ often did indeed bring pillage, rape, and death, and that if you were lucky you might be carried off into slavery. Maybe this year’s return of Vikings as warriors and slave traders is a depressing reflection of current headlines, with religious and ethnic genocides in Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere.

The post Viking reinventions appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories1914: The opening campaignsThe biggest threat to the world is still ourselvesBiting, whipping, tickling

Related Stories1914: The opening campaignsThe biggest threat to the world is still ourselvesBiting, whipping, tickling

August 28, 2014

Ethics of social networking in social work

Facebook celebrated its tenth anniversary in February. It has over 1.2 billion active users — equating to one user for every seven people worldwide. This social networking phenomenon has not only given our society a new way of sharing information with others; it’s changed the way we think about “liking” and “friending.” Actually, “friending” was not even considered a proper word until Facebook popularized its use. Traditionally, a friend is not just a person one knows, but a person with whom one shares personal affection, connection, trust, and familiarity. Under Facebook-speak, friending is simply the act of attaching a person to a contact list on the social networking website. One does not have to like, trust, or even know people in order to friend them. The purpose of friending is to connect people interested in sharing information. Some people friend only “traditional friends.” Others friend people on Facebook who are “mere acquaintances,” business associates, and even people with whom they have no prior relationship. On Facebook, “liking” is supposed to indicate that the person enjoys or is partial to the story, photo, or other content that someone has posted on Facebook. One does not have to be a friend to like someone’s content, and one may also like content on other websites.

Unbeknown to many Facebook users is how Facebook and other websites gather and use information about people’s friending and liking behaviors. For instance, the data gathered by Facebook is used to help determine which advertisements a particular user sees. Although Facebook does have some privacy protection features, many people do not use them, meaning that they are sharing private information with anyone who has access to the Internet. Even if a person tries to restrict information to “friends,” there are no provisions to ensure that the friends to not share the information with others, posting information in publically accessible places or simply sharing information in a good, old-fashioned manner – oral gossip. So, given what we know (and perhaps don’t know) about liking and friending, should social workers like their clients, encourage clients to like them, or friend their clients?

When considering the use of online social networking, social workers need to consider their ethical duties with respect to their primary commitment to clients, their duty to maintain appropriate professional boundaries, and their duty to protect confidential client information (NASW, Code of Ethics, 2008, Standards 1.01, 1.06, and 1.07). Allow me to begin with the actual situation that instigated my thinking about these issues. Recently, I saw a social worker’s Facebook page advertising her services. She encouraged potential clients to become friends and to like her. She offered a 10% discount in counseling fees for clients who liked her. What could possibly be a problem with providing clients with this sort of discount? The worker was providing clients with a benefit, and all they had to do was like her… they didn’t even have to become her friend.

In terms of 1.01, the social worker should ask herself whether she was acting in a way that promoted client interests, or whether she was primarily promoting her own interests. If her decision to offer discounts was purely a decision to promote profits (her interests), then she may be taking advantage (perhaps unintentionally) of her clients. If her clients were receiving benefits that outweighed the costs and risks, then she may be in a better position to justify the requests for friends and likes.

Woman in home office with computer and paperwork frowning. © monkeybusinessimages via iStockphoto.

Woman in home office with computer and paperwork frowning. © monkeybusinessimages via iStockphoto.With regard to maintaining appropriate boundaries, the worker should ask how clients perceive her requests for friends and likes. Do clients understand that the requests are in the context of maintaining a professional relationship, or might terms such as friending and liking blur the distinctions between professional and social relationships? If she truly wants to know whether clients value her services (as opposed to like), perhaps she should use a more valid and reliable measurement of client satisfaction or worker effectiveness. There are no Likert-type scales when it comes to liking on Facebook. You can only “like” or “do nothing.”

Confidentiality presents perhaps the most difficult issues when it comes to liking and friending. When a client likes a social worker who specializes in gambling addiction, for instance, does the client know that he may start receiving advertisements for gambling treatment services… or perhaps for casinos, gambling websites, or racetracks? Who knows what other businesses might be harvesting online information about the client. “OMG!” Further, does the client realize that the client’s Facebook friends will know the client likes the social worker? Although the client is not explicitly stating he is a client, others may draw this conclusion – and remember, these “others” are not necessarily restricted to the client’s trusted confidantes. They may include co-workers, neighbors, future employers, or others who may not hold the client’s best interests to heart.

One could say it’s a matter of consent – the worker is not forcing the client to like her, so liking is really an expression of the client’s free will. All sorts of businesses offer perks to people who like or friend them. Shouldn’t clients be allowed to pursue a discount as long as they know the risks? Hmmm… do they know the actual risks? Do they know that what seems like an innocuous act – liking – may have severe consequences one day? Consider, is it truly an expression of free will if the worker is using a financial incentive – particularly if clients have very limited income and means to pay for services? Further, young children and people with dementia or other mental conditions may not have the capacity to understand the risks and make truly informed choices.

Digital natives (people born into the digital age) might say these are the ramblings of an old curmudgeon (ok, they probably woudn’t use the term curmudgeon). When considering the ethicality of social work behaviors, we need to consider context. The context of Facebook, for instance, includes a culture where sharing seems to be valued much more than privacy. Many digital natives share intimate details of their life without grave concerns about their confidentiality. They have not experienced negative repercussions from posting details about their intimate relationships, break-ups, triumphs, challenges, and even embarrassments. They may not view liking a social worker’s website any riskier than liking their favorite ice cream parlor. So, to a large segment of Facebook users, is this whole issue much ado about nothing?

In the context of Internet risks, there are far more severe concerns than social workers asking clients to like them on Facebook. Graver Internet risks include cyber-bulling, identity theft, and hacking into national defense, financial institutions, and other important systems that are vulnerable to cyber-terrorism. Still, social workers should be cautious about asking clients to like them… on Facebook or otherwise.

The Internet offers social workers many different approaches to communicating with clients. Online communication should not be feared. On the other hand, social workers should consider all potential risks and benefits before making use of a particular online communication strategy. Social work and many other helping professions are still grappling with the ethicality of various online communication strategies with clients. What is hugely popular now – including Facebook – may continue to grow in popularity. However, with time and experience, significant risks may be exposed. Some technologies may lose popularity, and others may take their place.

Headline image credit: Internet icons and symbols. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Ethics of social networking in social work appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTell me a storyUnited Airlines and Rhapsody in BlueThe Queen whose Soul was Harmony - Enclosure

Related StoriesTell me a storyUnited Airlines and Rhapsody in BlueThe Queen whose Soul was Harmony - Enclosure

United Airlines and Rhapsody in Blue

As anyone who has flown United in the past quarter-century knows, the company has a long-standing history with George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. The piece appears in its television advertisements, its airport terminals, and even its pre-flight announcements. However, the history of United’s use of the piece is far from straight forward. This brand new safety video offers a compelling case in point:

Like recent videos by Air New Zealand and Delta Airlines, United’s safety briefing is designed to keep our attention as it reiterates the standard safety announcements that we know all too well. The video rewards paying close attention on multiple viewings. In fact, there are several airline-travel and United-specific “Easter Eggs.” A few of my favorites appear in the Las Vegas section. A tour bus traversing the Las Vegas Strip scrolls “lavatory occupied” and later “baggage on carousel 2.” Perhaps more subtle is a movie poster for a film titled “Elbow Room 2.” Look closely and you will see that it features a shot encountered later in the safety video as a James Bond-looking figure goes hand to hand against his nemesis a cable car—a clear reference to the 1979 film Moonraker for the alert viewer.

Under the banner “Safety is Global,” the familiar themes of the Rhapsody are musically arranged while diverse members of the United flight crew provide instructions from a series of specific and generic international locales. Certainly, the visuals play a key role in signaling our recognition of these surroundings: the Eiffel Tower and street corner cafe for Paris, a pagoda in front of Mt. Fuji for Japan, casinos and neon signs for Las Vegas, snow-covered peaks and a ski gondola for the Alps, kangaroos for Australia, a Vespa scooter and Mt. Edna for Italy, Chilean flamingos for the bird sanctuary, and palm trees and white-sands for the tropical beach.

But perhaps most important in drawing out the setting of each scene are the dramatic—if not clichéd—musical arrangements of Rhapsody in Blue. While in France a pair of accordions play the introductory bars of the piece while a pilot welcomes us aboard and reminds us to heed their instruction. A flight attendant hops a cab to Newark Airport (United’s East Coast hub) to the strains of a jazz combo setting of the love theme. A tenor saxophone improvises lightly around this most famous melody of the Rhapsody while she provides instruction on how to use the seatbelt from the bumpy backseat. A gong signals a move to Asia, where we encounter the ritornello theme of the Rhapsody on a plucked zither and bamboo flute. The bright-lights of the Las Vegas strip (where we learn about power outages) and a James Bond-inspired depiction of the Swiss Alps (where we learn about supplemental oxygen) are accompanied by the traditional symphonic arrangement of the Rhapsody created by Ferde Grofé. Curious kangaroos learn about life vests as the ritornello theme is heard on a harmonica punctuated by a didgeridoo and a rain stick. A mandolin plucks out the shuffle theme while a flight attendant extinguishes a volcano like a birthday candle—no smoking allowed! Finally, steel drums transport us to a Caribbean bird sanctuary and a tenor saxophone playing the stride theme to a laid-back, quasi-bossa nova groove relocates us to the beach.

Although each of these settings is somewhat stereotypical in its sonic and visual depiction of its respective locale, such treatment of the Rhapsody stands as less formulaic than past attempts at international representation by the airline. Both domestic and international advertisements have adapted the Rhapsody.

Although the video is a bit rough, by comparison to “Safety is Global,” the visuals and instrumentation choices are much more stereotypical. We clearly hear the “orientalist” signifiers at play: a taiko drum, a shakuhachi flute, a trio of pipas. But just as this commercial provides its American market with a glimpse at Asian cultures through the streamlined gaze of corporate advertising, a commercial aired in Japan in 1994 provides an equally reductive depiction of the United States.

The spot features a Japanese puppet of the traditional Bunraku style seated on an airplane as the voiceover announces a series of locales that travelers could visit at ever-increasing award levels. The puppet appears in a succession of wardrobes representative of each destination with arrangements of Rhapsody in Blue emphasizing each costume change: a shamisen accompanies the traditional Japanese kimono, an erhu for the silk Chinese robe, a Hawaiian slide guitar for a bright floral patterned shirt and yellow lei, a fiddle-driven two-step for a cowboy hat and bolo tie, and finally a calypso, steel drum for the white Italian sports coat and dark sunglasses—a clear reference to Don Johnson and Miami Vice. The commercial not only effectively promotes United’s frequent flyer program but also reinforces its corporate logos—both motto and music—to an international market. Through easily identifiable visual and sonic representations of destinations in the United States from Hawaii to Texas to Florida, it also promotes a positive—if not stereotypical—view of American culture using one of its most recognizable musical works.

And this is ultimately what the “Safety is Global” video accomplishes as well. By treating Rhapsody in Blue to a variety of musical arrangements, United Airlines has re-staked its claim on the Rhapsody not as its corporate theme music, but also as an international anthem. Its visualization of the Rhapsody over the course of time repositions the piece from a uniquely American (or specifically New Yorker) theme to one that aims to unite us all through the friendly skies.

Headline Image: Airplane Flying. Photo by Michael Stirling. CC0 1.0 Universal via Public Domain Pictures

The post United Airlines and Rhapsody in Blue appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Queen whose Soul was Harmony - EnclosureWhat can old Europe learn from new Europe’s transition?Aspirin the wonder drug: some food for thought

Related StoriesThe Queen whose Soul was Harmony - EnclosureWhat can old Europe learn from new Europe’s transition?Aspirin the wonder drug: some food for thought

Tell me a story

We all know that reading books to our young children is good for them. Teachers, pediatricians, and former First Ladies all tout the value of reading to kids. Contrary to conventional wisdom, however, reading books to children does not help them learn to read.

When we set aside our warm fuzzy images of a parent and child curled up in a rocking chair poring over a book together, and actually examine the data, we see a different picture. Sophisticated eye-tracking studies reveal that young children are looking pretty much everywhere but at the words when adults read a book to them. During the average book-reading session, a 4-year-old is looking at the print a mere 5% of the time. Numerous other studies, both correlational and experimental, tell us that shared book-reading does not directly help children’s letter recognition or word-reading abilities.

Does this mean we should throw the picture books out with the Etch-a-Sketch and the See ’n Say as amusing but not particularly useful educational tools? No. Shared book-reading sessions, particularly when adults make them interactive and fun, are excellent ways to promote children’s spoken language, their story skills, their understanding of the world, and their love of books. All of these skills will be absolutely vital later for children’s reading, when they are past the learning-to-read phase and entering the reading-to-learn phase at about age 8 or 9.

Father and Son. © Andrew Rich via iStockphoto.

Father and Son. © Andrew Rich via iStockphoto.What you may not know is that family storytelling is another way to help your child’s language skills. New research shows that telling stories together about everyday events promotes many of the same language skills as shared book-reading. For some families, telling stories together is actually a more effective way of enhancing preschool children’s storytelling skills. Family storytelling also helps young children’s understanding of other people’s mental states — their emotions and beliefs — an essential skill for social interactions. In one study, preschoolers whose mothers were taught to reminisce about emotions scored nearly twice as high on a test of understanding emotions compared to preschoolers whose mothers were taught to play in a more responsive way with their children.

One mother from my longitudinal research uses this “meta” talk about mental states when discussing the everyday event of going to a new playground with her 4-year-old daughter:

Mother: Okay, what else was at the playground?

Anna: Ummm, a bridge.

Mother: There was too. There was a bridge.

Anna: A wee house, two wee houses?

Mother: Were there? Ohh. What were the houses like? I don’t remember them.

Anna: They were, one made, there was one made out of wood and one made out of tires.

Mother: Oh right. I remember the tire one. You went inside it.

Anna: It’s stinky in there.

Mother: It was? Did Emily go on the slide? (Anna shakes head yes) Did she?

Anna: That’s why she knew.

Mother: Oh, that’s how she knew it was stinky. So did you enjoy that playground?

Anna: Yep.

Family storytelling is a natural practice that you can continue with your children for your whole life – long past the age most parents are reading books with their children. In my research, teens who knew more of their family’s stories communicated more openly with their friends and engaged in more prosocial acts, such as volunteering in their community. And when parents helped their young adolescents put a positive spin on negative events, as teens they were less depressed and had better self-esteem.

Here is the same parent talking with Anna at age 12 about a difficult tennis tournament:

Mother: How did you feel at the start of the tournament?

Anna: It was alright, I was kind of nervous.

Mother: It was your biggest tournament ever, wasn’t it?

Anna: Yeah. And then I played someone and I lost but I knew I’d lose so it didn’t matter. And then I played someone else and I thought I’d win but I didn’t and I was sad.

Mother: So that was the difference?

Anna: Yeah, and then I didn’t win any of the others and then I won the last one.

Mother: And it’s not easy to talk about those really bad things is it? But do you want to say what happened in the middle? It’s like a meltdown. Really, wasn’t it? Yeah, kind of. And there were tears.

Anna: Yeah.

Mother: There were tears because it just wasn’t a good day at all, was it?

Anna: No, not really.

Mother: And you didn’t want to do it.

Anna: No.

Mother: And did your mum say that’s okay Anna, you don’t have to do it?

Anna: No (laughs).

Mother: What did mum say?

Anna: She said, what did you say?

Mother: That you had to finish the match.

Anna: You have to finish and so I did and then I got a present ’cause I kept going.

Mother: It’s really important we thought to have acknowledged the fact that you kept going on. It was really . . .

Anna: Persevering.

Mother: Perseverance in the face of extreme difficulty.

Best of all, family storytelling is free, requiring only your time, memory, and ingenuity at telling the right story at an apt moment. Unlike book-reading, family storytime can happen anywhere: on a walk, at the dinner table, or in the car. So tonight after you tuck in your child and read them a story, turn out the lights and slip in a family story of the day. Let your child ask questions and tell the parts of the story they remembered and enjoyed. You will be starting a tradition that you can keep up long past the time they’re asking to hear Madeline or Thomas the Tank Engine “just one more time.” Instead, you will hear, “Tell me a story, Dad, about the time you…”

The post Tell me a story appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAspirin the wonder drug: some food for thoughtEthics of social networking in social workUnited Airlines and Rhapsody in Blue

Related StoriesAspirin the wonder drug: some food for thoughtEthics of social networking in social workUnited Airlines and Rhapsody in Blue

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers