Oxford University Press's Blog, page 767

September 3, 2014

A First World War reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

As the first year of the World War I centenary continues, here is a selection of classic literature inspired by the conflict. Some of it was written in the years after the war, while some of it was completed as the conflict was in progress. What they all have in common, though, is an unflinchingly expression of the horrors of the First World War for those in the thick of the battles, and those left behind at home.

The Poetry of the First World War, edited by Tim Kendall

The First World War brought forth an extraordinary amount of poetic talent. Their poems have come to express the feelings of a nation about the horrors of war. Some of these poets are widely read and studied to this day, such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Rupert Brooke, and Ivor Gurney. However, others are less widely read, and this anthology incorporates that writing with work by civilian and woman poets, along with music hall and trench songs.

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

This, Woolf’s fourth novel, prominently features Septimus Warren Smith, a young man deeply damaged by his time in the First World War. Shellshock causes him to hallucinate – he thinks he hears birds in a park chattering in Greek, for instance – and the psychological toll wrought by war drives him to a profound hatred of himself and the whole human race.

The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford

Ford Madox Ford was in the process of writing The Good Soldier when the First World War broke out in 1914. Inevitably this influenced his work, and this novel brilliantly portrays the destruction of a civilized elite as it anticipates the cataclysm of war. It also invokes contemporary concerns about sexuality, psychoanalysis, and the New Woman.

Greenmantle by John Buchan

Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In Greenmantle – published during the First World War, in 1916 – Richard Hannay travels across Europe as it is being torn apart by war. He is in search of a German plot and an Islamic Messiah, and is in the process joined by three more of Buchan’s heroes: old Boer Scout Peter Pienaar; John S. Blenkiron, an American determined to fight the Kaiser; and Sandy Arbuthnot, Greenmantle himself, who was modelled on Lawrence of Arabia. In this rip-roaring tale Buchan shows his mastery of the thriller and of the Stevensonian romance, and also his enormous knowledge of international politics before and during World War I.

Jacob’s Room by Virginia Woolf

This is Virginia Woolf’s third novel, and was published in 1922. It is an experimental portrait of Jacob Flanders, a young man who is both representative and victim of the social values which led Edwardian society into the First World War. Even his very name indicates his position as the archetypal victim of the war: Flanders is an area of Belgium where many British soldiers were killed and injured during the First World War. Jacob’s Room is an experimental novel, cutting back and forth in time, and never quite allowing the reader full sight of its subject. Rather, Jacob’s story is told through the words and memories of the women in his life.

War Stories and Poems by Rudyard Kipling

Rudyard Kipling may be most commonly remembered for the Just So Stories and The Jungle Book, but he also wrote extensively about war. His only son, John, was unfortunately killed in action in 1915, and Kipling took many years to accept what had happened. Until his death in 1936, he continued searching for his son’s final resting place but even today John has no known grave. Of the poems Kipling wrote in the aftermath of the First World War, perhaps the best known is his tribute to The Irish Guards (1918), the regiment with which his son was serving at the time of his death.

Headline image credit: World War One soldier’s diary pages. Photo by lawcain via iStockphoto.

The post A First World War reading list from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSong of AmiensA back-to-school reading list of classic literatureA Woman’s Iliad?

Related StoriesSong of AmiensA back-to-school reading list of classic literatureA Woman’s Iliad?

The economics of Scottish Independence

On September 18, Scots will go to the polls to vote on the question “Should Scotland be an independent country?” A “yes” vote would end the political union between England and Scotland that was enacted in 1707.

The main economic reasons for independence, according to the “Yes Scotland” campaign, is that an independent Scotland would have more affordable daycare, free university tuition, more generous retirement and health benefits, less burdensome regulation, and a more sensible tax system.

As a citizen of a former British colony, it is tempting to compare the situation in Scotland with those of British colonies and protectorates that gained their independence, such as the United States, India/Pakistan, and a variety of smaller countries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, although such a comparison is unwarranted.

Historically, independence movements have been motivated by absence of representation in the institutions of government, discrimination against the local population, and economic grievances. These arguments do not hold in the Scottish case.

Scotland is an integral part of the United Kingdom. It is represented in the British Parliament in Westminster, where it holds 9% of the seats—fair representation, considering that Scotland’s population is a bit less than 8.5% of total UK population.

Scotland does have a considerable measure of self-government. A Scottish Parliament, created in 1998, has authority over issues such as health, education, justice, rural affairs, housing and the environment, and some limited authority over tax rates. Foreign and defense policy remain within the purview of the British government.

Scots do not seem to have been systematically discriminated against. At least eight prime ministers since 1900, including recent ex-PMs Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, were either born in Scotland or had significant Scottish connections.

Scotland is about as prosperous as the rest of the UK, with output per capita greater than those of Wales, Northern Ireland, and England outside of London (see figure).

Because the referendum asks only whether Scotland should become independent and contains no further details on how the break-up with the UK would be managed, it is important to consider some key economic issues that will need to be tackled should Scotland declare its independence.

Graph showing UK Gross Value, created by Richard S. Grossman with data from the UK Office of National Statistics.

Graph showing UK Gross Value, created by Richard S. Grossman with data from the UK Office of National Statistics.Since Scotland already has a parliament that makes many spending and taxing decisions, we know something about Scottish fiscal policy. According to the World Bank figures, excluding oil (a resource that is expected to decline in importance in coming decades), Scotland’s budget deficit as a share of gross domestic product already exceeds those of fiscally troubled neighbors Greece, Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Italy. Given the “Yes” campaign’s promise to make Scotland’s welfare system even more generous, the fiscal sustainability of an independent Scotland’s is unclear.

As in any divorce, the parties would need to divide their assets and liabilities.

The largest component of UK liabilities are represented by the British national debt, recently calculated at around £1.4 trillion ($2.4 trillion), or about 90 percent of UK GDP. What share of this would an independent Scotland “acquire” in the break-up?

Assets would also have to be divided. One of the greatest assets—North Sea oil—may be more straightforward to divide given that the legislation establishing the Scottish Parliament also established a maritime boundary between England and Scotland, although this may be subject to negotiation. But what about infrastructure in England funded by Scottish taxes and Scottish infrastructure paid for with English taxes?

An even more contentious item is the currency that would be used by an independent Scotland. The pro-independence camp insists that an independent Scotland would remain in a monetary union with the rest of the UK and continue to use the British pound. And, in fact, there is no reason why an independent Scotland could not declare the UK pound legal tender. Or the euro. Or the US dollar, for that matter.

The problem is that the “owner” of the pound, the Bank of England, would be under no obligation to undertake monetary policy actions to benefit Scotland. If a sluggish Scottish economy is in need of loose monetary policy while the rest of the UK is more concerned about inflation, the Bank of England would no doubt carry out policy aimed at the best interests of the UK—not Scotland.

If a Scottish financial institution was on the point of failure, would the Bank of England feel duty-bound to lend pounds? As lender of last resort in England, the Bank has an obligation to supervise—and assist, via the extension of credit—troubled English financial institutions. It seems unlikely that an independent Scotland would allow its financial institutions to be supervised and regulated by a foreign power—nor would that power be morally or legally required to extend the UK financial safety net to Scotland.

At the time of this writing (the second half of August), the smart money (and they do bet on these things in Britain) is on Scotland saying no to independence, although poll results released on August 18 found a surge in pro-independence sentiment. Whatever the polls indicate, no one is taking any chances. Several Scottish-based financial companies are establishing themselves as corporations in England so that, in the case of independence they will not be at a foreigner’s disadvantage vis-à-vis their English clients. Given the economic uncertainty generated by the vote, the sooner September 18 comes, the better for both Scotland and the UK.

Headline image credit: Scottish Parliament building, by Jamieli. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The economics of Scottish Independence appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Dis-United KingdomThe road to egalitariaWhy referendum campaigns are crucial

Related StoriesThe Dis-United KingdomThe road to egalitariaWhy referendum campaigns are crucial

The Dis-United Kingdom

Is the UK really in danger of dis-uniting? The answer is ‘no’. But the more interesting answer is that the independence referendum is, to some extent, a red herring. The nationalists may well lose the referendum but they have already won the bigger political battle over power and money. All the main political parties in the UK have agreed give Scotland more powers and more financial competencies – or what is called ‘devo-max’ irrespective of what happens on 18 September.

Viewed from the other side of the world the Scottish independence referendum forms part of a colonial narrative that underpins a great deal of Australian life. Some commentators take great pleasure in forecasting ‘the death’ of the United Kingdom and the demise of the English. Michael Sexton’s headline in The Australian, ‘Scotland chips away at the English empire’, is high on hyperbole and, dare I say, even colonial gloating. It sadly lacks any real understanding of British constitutional history and how it has consistently managed territorial tensions. The UK has long been a ‘union state’ rather than a unitary state. Each nation joined the union for different reasons and maintained distinctive institutions or cultural legacies.

The relationships among and between the countries in the UK have changed many times. Like tectonic plates, the countries rub and grate against each other but through processes of conciliation and compromise (and the dominance of England) volcanic eruptions have been rare. In the late 1990s devolutionary pressures were channeled through the delegation of powers to the Northern Ireland Assembly, National Assembly for Wales and the Scottish Parliament. Different competencies reflected the extent of popular pressure within each country and since the millennium, with the exception of Northern Ireland, it is possible to trace the gradual devolution of more powers. Wales wants a Parliament, Scotland wants a stronger Parliament – but few people want independence from a Union that has arguably served them well.

But has the Union really served the Scots so well? It is true that the UK as a whole and not justScotland has benefitted from the North Sea Oil revenues. ‘It’s Scotland’s oil!’ might have been the Scottish Nationalist Party’s slogan in the 1970s but it captures a sentiment that underpins today’s debates. It also overlooks the manner in which Scotland also receives a generous slice of the financial pie when public funds are allocated. Fees and charges for many public services that exist in England, Wales and Northern Ireland are absent north of the border. The nationalists argue that public services could be increased if Scotland had more control over North Sea Oil but they play down the fact that many analysts believe that the pool of black gold is nearly empty and that an independent country would have to take its share of the UK’s national debt. Depending upon how the debt-cake is cut this would be a figure around £150 billion.

The UK Government claims Scots would be £1,400 better off if they stayed in the union, the Scottish government claims that they would be £1,000 better off with independence but the simple fact is that independence is a risky game to play for a small state – the political equivalent of Russian roulette in an increasingly competitive and globalised world. There are lots of questions but few answers. On independence would Scotland remain in the European Union? How would an independent Scotland defend itself? What currency would they use? What kind of international role and influence would an independent Scotland have? Would a ‘Yes Vote’ be good for business? What happens in relation to immigration and border controls? What would independence mean for energy markets? The simple fact is that there are no clear answers to these basic questions. The nationalists understandably define many of these questions as little more than ‘scare tactics’ but independence must come with a price.

Union Jack and Scotland, by Julien Carnot. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Union Jack and Scotland, by Julien Carnot. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Nationalists (such a tired and simplistic term in a world of multiple and overlapping loyalties) may argue that independence is about culture and identity, heart and soul – not bureaucracies and budgets and I would not disagree. The problem is that when stood in the voting booth the Scottish public is likely to vote according to their head (and their wallet) and not their heart. The twist in the tail is that support for Scottish independence has at times been higher amongst the English (and that is 54 million people compared to just five million in Scotland) than the Scottish. Therefore if the referendum on Scottish independence was open to the whole of the UK, as many have argued it should be, Scotland may well have been cast adrift by its English neighbours.

And yet the strangest element of this whole Scottish independence debate is that the model of independence on offer has always been strangely lacking in terms of … how can I put it … independence. What’s on offer is a strange quasi-independence where the Scottish Government wants to share the pound sterling and the Bank of England, it wants to share the British army and other military forces and what this amounts to is a rather odd half-way house that is more like greater devolution within the Union rather than true independence as a self-standing nation state. The risks are therefore high but the benefits uncertain and this explains why the Scottish public remains to be convinced that the gamble is worth it. The latest polling figures find 57% against and 43% in support of a ‘yes’ vote but a shift to the ‘no’ camp can be expected as the referendum draws closer and the public becomes more risk averse.

But does this really matter? A ‘yes vote’ was always incredibly unlikely. Mass public support has never existed and the referendum is really part of a deeper power game to lever more powers from London to Scotland and to this extent the game is already over. Devo-max has already been granted. The 2012 Scotland Act has already been passed and boosts the power of the Scottish Parliament by giving it a new ability to tax and borrow along with a number of new policy powers. (The most important new measure – giving the parliament partial control over setting income tax rates in Scotland will come into force in 2015.) Since this legislation was passed the three main political parties in Westminster have all agreed to devolve even more powers, specifically in relation to tax and welfare.

Mark Twain famously remarked that ‘reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated’ and I cannot help but feel the same is true in relation to those who like to trumpet the death of the United Kingdom. The Scottish independence referendum is highly unlikely to amount to a Dis-United Kingdom or the ‘unraveling’ of the union. It may amount to a ‘looser’ union but the relationship between Edinburgh and Westminster has always been one of partnership rather than domination. My sense is that what we are witnessing is not ‘the end’ as some commentators would like to see it but the beginning of a new stage in a historical journey that has already lasted over three hundred years.

The post The Dis-United Kingdom appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy referendum campaigns are crucialThe burden of guilt and German politics in EuropeThe French burqa ban

Related StoriesWhy referendum campaigns are crucialThe burden of guilt and German politics in EuropeThe French burqa ban

September 2, 2014

The real story of Saint Patrick

Everyone knows about Saint Patrick — the man who drove the snakes out of Ireland, defeated fierce Druids in contests of magic, and used the shamrock to explain the Christian Trinity to the pagan Irish. It’s a great story, but none of it is true. The shamrock legend came along centuries after Patrick’s death, as did the miraculous battles against the Druids. Forget about the snakes — Ireland never had any to begin with. No snakes, no shamrocks, and he wasn’t even Irish.

The real story of St. Patrick is much more interesting than the myths. What we know of Patrick’s life comes only through the chance survival of two remarkable letters which he wrote in Latin in his old age. In them, Patrick tells the story of his tumultuous life and allows us to look intimately inside the mind and soul of a man who lived over fifteen hundred years ago. We may know more biographical details about Julius Caesar or Alexander the Great, but nothing else from ancient times opens the door into the heart of a man more than Patrick’s letters. They tell the story of an amazing life of pain and suffering, self-doubt and struggle, but ultimately of faith and hope in a world which was falling apart around him.

Saint Patrick stained glass window from Cathedral of Christ the Light, Oakland, CA. Photo by Simon Carrasco. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Saint Patrick stained glass window from Cathedral of Christ the Light, Oakland, CA. Photo by Simon Carrasco. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The historical Patrick was not Irish at all, but a spoiled and rebellious young Roman citizen living a life of luxury in fifth-century Britain when he was suddenly kidnapped from his family’s estate as a teenager and sold into slavery across the sea in Ireland. For six years he endured brutal conditions as he watched over his master’s sheep on a lonely mountain in a strange land. He went to Ireland an atheist, but there heard what he believed was the voice of God. One day he escaped and risked his life to make a perilous journey across Ireland, finding passage back to Britain on a ship of reluctant pirates. His family welcomed back their long-lost son and assumed he would take up his life of privilege, but Patrick heard a different call. He returned to Ireland to bring a new way of life to a people who had once enslaved him. He constantly faced opposition, threats of violence, kidnapping, and even criticism from jealous church officials, while his Irish followers faced abuse, murder, and enslavement themselves by mercenary raiders. But through all the difficulties Patrick maintained his faith and persevered in his Irish mission.

The Ireland that Patrick lived and worked in was utterly unlike the Roman province of Britain in which he was born and raised. Dozens of petty Irish kings ruled the countryside with the help of head-hunting warriors while Druids guided their followers in a religion filled with countless gods and perhaps an occasional human sacrifice. Irish women were nothing like those Patrick knew at home. Early Ireland was not a world of perfect equality by any means, but an Irish wife could at least control her own property and divorce her husband for any number of reasons, including if he became too fat for sexual intercourse. But Irish women who were slaves faced a cruel life. Again and again in his letters, Patrick writes of his concern for the many enslaved women of Ireland who faced beatings and abuse on a daily basis.

Patrick wasn’t the first Christian to reach Ireland; he wasn’t even the first bishop. What made Patrick successful was his dogged determination and the courage to face whatever dangers lay ahead, as well as the compassion and forgiveness to work among a people who had brought nothing but pain to his life. None of this came naturally to him, however. He was a man of great insecurities who constantly wondered if he was really cut out for the task he had been given. He had missed years of education while he was enslaved in Ireland and carried a tremendous chip on his shoulder when anyone sneered, as they frequently did, at his simple, schoolboy Latin. He was also given to fits of depression, self-pity, and violent anger. Patrick was not a storybook saint, meek and mild, who wandered Ireland with a beatific smile and a life free from petty faults. He was very much a human being who constantly made mistakes and frequently failed to live up to his own Christian ideals, but he was honest enough to recognize his shortcomings and never allow defeat to rule his life.

You don’t have to be Irish to admire Patrick. His is a story of inspiration for anyone struggling through hard times public or private in a world with unknown terrors lurking around the corner. So raise a glass to the patron saint of Ireland, but remember the man behind the myth.

Headline image credit: Oxalis acetosella. Photo by Erik Fitzpatrick. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The real story of Saint Patrick appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWar poetry across the centuriesAnthropology and ChristianityThe Wilderness Act of 1964 in historical perspective

Related StoriesWar poetry across the centuriesAnthropology and ChristianityThe Wilderness Act of 1964 in historical perspective

The Wilderness Act of 1964 in historical perspective

Signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson on 3 September 1964, the Wilderness Act defined wilderness “as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” It not only put 1.9 million acres under federal protection, it created an entire preservation system that today includes nearly 110 million acres across forty-four states and Puerto Rico—some 5% of the land in the United States. These public lands include wildlife refuges and national forests and parks where people are welcome as visitors, but may not take up permanent residence.

The definition of what constitutes “wilderness” is not without controversy, and some critics question whether preservation is the best use of specific areas. Nevertheless, most Americans celebrate the guarantee that there will always be special places in the United States where nature can thrive in its unfettered state, without human intervention or control. Campers, hikers, birdwatchers, scientists and other outdoor enthusiasts owe much to Howard Zahniser, the act’s primary author.

In recent decades, environmental awareness and protection are values just about as all-American as Mom and apple pie. Despite the ill-fated “Drill, Baby, Drill,” slogan of the 2008 campaign, virtually all political candidates, whatever their party, profess concern about the environment and a commitment to its protection. As a professor, I have a hard time persuading my students, who were born more than two decades after the first Earth Day (in 1970), that environmental protection was once commonly considered downright traitorous.

For generations, many Americans were convinced that it was the exploitation of natural resources that made America great. The early pioneers survived because they wrested a living from the wilderness, and their children and grandchildren thrived because they turned natural resources into profit. Only slowly did the realization come that people had been so intent on pursuing vast commercial enterprises they failed to consider their environmental impact. When, according to the 1890 census, the frontier was closed, the nation was no longer a land of ever-expanding boundaries and unlimited resources. Birds like the passenger pigeon and the Carolina Parakeet were hunted into extinction; practices like strip-mining left ugly scars on the land, and clear-cutting made forest sustainability impossible.

At the turn of the last century members of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs called for the preservation of wilderness, especially through the creation of regional and national parks. They enjoyed the generous cooperation of the Forest Service during the Theodore Roosevelt administration, but found that overall, “it is difficult to get anyone to work for the public with the zeal with which men work for their own pockets.”

President Theodore Roosevelt and naturalist John Muir atop Glacier Point in Yosemite. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

President Theodore Roosevelt and naturalist John Muir atop Glacier Point in Yosemite. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Not surprisingly, Theodore Roosevelt framed his support for conservation in terms of benefiting people rather than (non-human) nature. In 1907 he addressed both houses of Congress to gain support for his administration’s effort to “get our people to look ahead and to substitute a planned and orderly development of our resources in place of a haphazard striving for immediate profit.” It is a testament to Roosevelt’s persona that he could sow the seeds of conservationism within a male population deeply suspicious of any argument even remotely tinged with what was derided as “female sentimentality.” Writer George L. Knapp, for example, termed the call for conservation “unadulterated humbug” and the dire prophecies of further extinction “baseless vaporings.” He preferred to celebrate the fruits of men’s unregulated resource consumption: “The pine woods of Michigan have vanished to make the homes of Kansas; the coal and iron which we have failed—thank Heaven!—to ‘conserve’ have carried meat and wheat to the hungry hives of men and gladdened life with an abundance which no previous age could know.” According to Knapp, men should be praised, not chastened, for turning “forests into villages, mines into ships and skyscrapers, scenery into work.”

The press reinforced the belief that the use of natural resources equaled progress. The Houston Post, for example, declared, “Smoke stacks are a splendid sign of a city’s prosperity,” and the Chicago Record Herald reported that the Creator who made coal “knew that smoke would be a good thing for the world.” Pittsburgh city leaders equated smoke with manly virtue and derided the “sentimentality and frivolity” of those who sought to limit industry out of baseless fear of the by-products it released into the air.

Pioneering educator and psychologist G. Stanley Hall confirmed that “caring for nature was female sentiment, not sound science.” Gifford Pinchot, made first chief of the Forestry Service in 1905, was a self-avowed conservationist. He escaped charges of effeminacy by making it clear that he measured nature’s value by its service to humanity. He dedicated his agency to “the art of producing from the forest whatever it can yield for the service of man.” “Trees are a crop, just like corn,” he famously proclaimed, “Wilderness is waste.”

Looking back at the last fifty years, the Wilderness Act of 1964 is an important achievement. But it becomes truly remarkable when viewed in the context of the long history that preceded it.

Headline image credit: Cook Lake, Bridger-Teton National Forest, Wyoming. Photos by the Pinedale Ranger District of the Bridger-Teton National Forest. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Wilderness Act of 1964 in historical perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe long journey to StonewallAlice Paul, suffragette and activist, in 10 factsThe road to hell is mapped with good intentions

Related StoriesThe long journey to StonewallAlice Paul, suffragette and activist, in 10 factsThe road to hell is mapped with good intentions

September 1, 2014

The US Supreme Court should reverse Wynne – narrowly

Maryland State Comptroller of the Treasury v. Brian Wynne requires the US Supreme Court to decide whether the US Constitution compels a state to grant an income tax credit to its residents for the out-of-state income taxes such residents pay on out-of-state income.

Brian and Karen Wynne live in Howard County, Maryland. As Maryland residents, the Wynnes pay state and county income taxes on their worldwide income. The Maryland income tax statute provides that Maryland residents who pay income taxes to states in which they do not live may credit against their Maryland state income tax liability the taxes paid to those states of nonresidence. However, the Maryland tax law grants no equivalent credit under the county income tax for out-of-state taxes owed by Maryland residents on income earned outside of Maryland.

When the Wynnes complained about the absence of a credit against their Howard County income tax for the out-of-state income taxes the Wynnes paid, Maryland’s Court of Appeals agreed. Maryland’s highest court held that such credits are required by the nondiscrimination principle of the US Constitution’s dormant Commerce Clause. The absence of a credit against the county income tax induces Maryland residents like the Wynnes to invest and work in-state rather than out-of-state. This incentive, the Maryland court held, may impermissibly “affect the interstate market for capital and business investment.”

For two reasons, the US Supreme Court should reverse. First, Wynne highlights the fundamental incoherence of the dormant Commerce Clause test of tax nondiscrimination: any tax provision can be transformed into an economically equivalent direct expenditure. No principled line can be drawn between those tax provisions which are deemed to discriminate against interstate commerce and those which do not. All taxes and government programs can incent residents to invest at home rather than invest out-of-state. It is arbitrary to label only some taxes and public programs as discriminating against interstate commerce.

Suppose, for example, that Howard County seeks to improve its public schools, its police services or its roads. No court or commentator suggests that this kind of routine public improvement violates the dormant Commerce Clause principle of nondiscrimination. However, such direct public expenditures, if successful, have precisely the effect on residents and interstate commerce for which the Court of Appeals condemned the Maryland county income tax as discriminating against interstate commerce: Better public services also “may affect the interstate market for capital and business investment” by encouraging current residents and businesses to stay and by attracting new residents and businesses to come.

There is no principled basis for labeling as discriminatory under the dormant Commerce Clause equivalent tax policies because they affect “the interstate market” of households and businesses. Direct government outlays have the same effects as do taxes on the choice between in-state and out-of-state activity. If taxes discriminate against interstate commerce because they encourage in-state enterprise, so do direct government expenditures which make the state more attractive and thereby stimulate in-state activity.

Snow Clouds Over a Snowy Field, Patuxent Hills, Maryland. Photo by Karol Olson. CC BY 2.0 via olorak Flickr.

Snow Clouds Over a Snowy Field, Patuxent Hills, Maryland. Photo by Karol Olson. CC BY 2.0 via olorak Flickr.Second, the political process concerns advanced both by the Wynne dissenters in Maryland’s Court of Appeals and by the US Solicitor General are persuasive. Mr. and Mrs. Wynne are Maryland residents who, as voters, have a voice in Maryland’s political process. This contrasts with nonresidents and so-called “statutory residents,” individuals who are deemed for state income tax purposes to be residents of a second state in which they do not vote. As nonvoters, nonresidents and statutory residents lack political voice when they are taxed by states in which they do not vote.

Nonresidents and statutory residents require protection under the dormant Commerce Clause since politicians find it irresistible to export tax obligations onto nonvoters. The Wynnes, on the other hand, are residents of a single state and vote for those who impose Maryland’s state and local taxes on them.

In reversing Wynne, the Supreme Court should decide narrowly. The Wynnes, as residents of a single state, should not receive constitutional protection for their claim to a county income tax credit for the out-of-state taxes the Wynnes pay. However, the Court’s decision should not foreclose the Court from ruling, down the road, that credits are required to prevent the double income taxation of individuals who, for income tax purposes, are residents of two or more states. Such dual residents lack the vote in one of the states taxing them and thus require constitutional succor which the Wynnes do not.

Dissenting in Cory v. White, Justice Powell (joined by Justices Marshall and Stevens) argued “that multiple taxation on the basis of domicile” is unconstitutional. Since the Wynnes are taxed by only one state, the Supreme Court need not now confront this issue again. However, the Court should decide Wynne in a fashion which allows the Court to revisit this question in the future by holding that credits are constitutionally required to prevent the double taxation of dual residents.

The post The US Supreme Court should reverse Wynne – narrowly appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesStop and search, and the UK policeTime to see the endCasey Kasem and end-of-life planning

Related StoriesStop and search, and the UK policeTime to see the endCasey Kasem and end-of-life planning

Stop and search, and the UK police

The recent announcement made jointly by the Home Office and College of Policing is a vacuous document that will do little or nothing to change police practice or promote better police-public relations.

Let us be clear: objections to police stop and search is not just a little local difficulty, experienced solely in this country. Similar powers are felt to be just as discriminatory throughout North America where it is regarded as tantamount to an offence of ‘driving whilst black’ (DWB). This and other cross-national similarities persist despite differences in the statutory powers upon which the police rely. It would, therefore, seem essential to ask whether differences in legislation or policy have proven more or less effective in different jurisdictions. Needless to say, absolutely no evidence of experience elsewhere is to be found in this latest Home Office document. Instead, to assuage the concerns of the Home Secretary, more meaningless paperwork will be created.

One reason why evidence seems to be regarded as unnecessary is the commonplace assumption that ‘everyone knows’ why minorities experience disproportionate levels of stop and search: namely that officers rely not upon professional judgement, but upon prejudice, when exercising this power. Enticing though such an assumption is, it has serious weaknesses. As Professor Marion Fitzgerald discovered, when officers are deciding who to stop and search entirely autonomously, they act less disproportionately than when acting on specific information, such as a description.

Research that I and Kevin Stenson conducted in the early 2000s also found that the profile of those stopped and searched very largely corresponded to the so-called ‘available population’ of people out and about in public places at the times when stop and search is most prevalent. This is not to say that these stops and searches were conducted either lawfully or properly. Indeed, a former Detective Chief Superintendent interviewed a sample of 60 officers about their most recent stops and searches as part of this research. What he found was quite alarming, for in around a third of cases the accounts that officers freely gave about the circumstances of these 128 stops and searches could not convince any of us that they were lawful. There was also a woeful lack of knowledge amongst these officers about the statutory basis for the powers upon which officers were relying.

UK police officer watches traffic at roadside. © RussDuparcq via iStock.

UK police officer watches traffic at roadside. © RussDuparcq via iStock.If officers were much better informed about their powers, then perhaps the experience of stop and search may be less disagreeable — it is unlikely ever to be welcomed — than it often is. Paragraph 1.5 of the Code of Practice governing how police stop and search states:

1.5 An officer must not search a person, even with his or her consent, where no power to search is applicable. Even where a person is prepared to submit to a search voluntarily, the person must not be searched unless the necessary legal power exists, and the search must be in accordance with the relevant power and the provisions of this Code.

The implication of this is quite clear: police may stop and search someone with their consent, but may not use such consent as a means of subverting the requirements under which the search would be lawful. Yet, so few officers seem even to be aware of this and conduct stop and search solely on the basis of their formal powers. I believe they do this as a ‘shield’; they imagine that if they go through the formal motions then no one can object to the lawfulness of the search. But they do object and do so most valuably, which gravely damages the public reputation of the police.

Research evidence aplenty confirms that it is not the possession of this power by the police that irks even those who are most at risk of stop and search. What they really object to is the manner in which the stop and search is conducted. A more consensual approach by police officers might just make the use of this power just a little more palatable.

The post Stop and search, and the UK police appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTime to see the endWhy referendum campaigns are crucialDoes industry sponsorship restrict the disclosure of academic research?

Related StoriesTime to see the endWhy referendum campaigns are crucialDoes industry sponsorship restrict the disclosure of academic research?

How does color affect our way of seeing the world?

There is a study of color perception that has gotten around enough that I would like to devote this post to how I see it, according to my take on whether, and how, language “shapes” thought and creates a “worldview.”

The experiment involved the Himba people, and is deliciously tempting for those seeking to show how language creates a way of seeing the world.

There are two parts to the experiment. Part One: presented with a group of squares, most of them various shades of green and one of them a robin’s egg-style blue, Himba tended to have a hard time picking out which square was “different.” That would seem to suggest that having a single word for green and blue really does affect perception.

Part Two: presented with a number of squares which, to Western eyes, seem like minimally different shades of green, Himba people often readily pick out a single square which is distinct from the others. This, too, seems to correlate with something about their language. Namely, although they only have four color terms (similarly to many indigenous groups), those terms split up what we think of as the green range into three pieces – one color corresponds to various dark colors including dark green, one to “green-blue,” and then another one to other realms of green (and other colors).

Both of these results – on film, a Himba woman seeming quite perplexed trying to pick out the blue square, and meanwhile a Himba man squinting a bit and then picking out what looks to us like just one more leafy green square – seem to confirm that how your language describes a color makes a huge difference to how you see the color. The implications are obvious for other work in this tradition addressing things like terms for up and down, gender for inanimate objects, and the like.

But in fact, both cases pan out in ways quite unlike what we might expect. First, the blue square issue. It isn’t for nothing that some have speculated in all seriousness that if the Himba really can’t perceive the difference between forest green and sky blue, then the issue might be some kind of congenital color blindness (which is hardly unknown among isolated groups for various reasons).

Autumn colour, by Ian Kirk from Broadstone, Dorset, UK. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Autumn colour, by Ian Kirk from Broadstone, Dorset, UK. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons That may seem a little hasty. But no one studying color terms, or language and thought, has ever denied that colors occur along a spectrum, upon which some are removed from one another to an extent that no humans have ever been claimed not to be able to perceive. Russians can suss out where dark blue starts shading into light a teensy bit faster than English speakers because they have separate words for light and dark blue – indeed. But no one claims that an English speaker plain can’t see the difference between navy blue and sky blue.

Along those lines, no one would remotely expect that a Himba speaker, or anyone, could actually not see the difference between spectographically distinct shades such as sky blue and forest green. One suspects that issues to do with familiarity with formal tests and their goals may have played a role here – but not that having the same word for green and blue actually renders one what we would elsewhere term color-blind.

Then, as to the shades of green, I’m the last person to say that the man on film didn’t pick out that shade of green faster than I would have expected. However, the question is whether we are seeing a “world view,” we must decide that question according to a very simple metric. The extent to which we treat something in someone’s language as creating a “cool” worldview must be the same extent to which we are prepared to accept something in someone’s language that suggests something “uncool” – because there are plenty of such things.

A demonstration case is Chinese, in which marking plurality, definiteness, hypotheticality, and tense are all optional and as often as not, left to context. The language is, compared to English, strikingly telegraphic. An experiment was done some time ago suggesting that, for example, the issue with hypotheticality meant that to be Chinese was to be less sensitive to the hypothetical than an English speaker is. That is, let’s face it, a cute way of saying that to be Chinese is to be not quite as quick on the uptake as a Westerner.

No one liked that, and I assume that most of us are quite prepared to say that whatever the results of that experiment were, they can’t have anything significant to do with Chinese perception of reality. Well, that means the verdict has to be the same on the Himba and green – we can’t think of him as seeing a world popping with gradations of green we’d never dream of if we can’t accept the Chinese being called a tad simple-minded. This is especially when we remember that there are many groups in the world whose color terms really don’t divvy up any one color in a cool way – they just don’t have as many names for colors, any colors, as we do. Are we ready to condemn them as not seeing the world in colors as vivid as we do because of the way they talk?

Surely not, and that’s the lesson the Himba experiment teaches. Language affects worldview in minuscule ways, of a sort you can tease out in a lab. However, the only way to call these minuscule ways “worldviews” is to accept that to be Chinese is to be dim. I don’t – and I hope none of the rest of us do either.

The post How does color affect our way of seeing the world? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy learn Arabic?Reading demeanor in the courtroomQuebec French and the question of identity

Related StoriesWhy learn Arabic?Reading demeanor in the courtroomQuebec French and the question of identity

August 31, 2014

Why learn Arabic?

To celebrate the launch of our new Oxford Arabic Dictionary (in print and online), the Chief Editor, Tressy Arts, explains why she decided to become an Arabist.

When I tell people I’m an Arabist, they often look at me like they’re waiting for the punchline. Some confuse it with aerobics and look at me dubiously — I don’t quite have the body of a dance instructor. Others do recognize the word “Arabic” and look at me even more dubiously — “What made you decide to study that!?”

Well, my case is simple, if probably not typical. In the Netherlands, where I grew up, you can learn a lot of languages in secondary school, and I tried them all. So when the time came to choose a university study, “a language that isn’t like the others” seemed the most attractive option — and boy, did Arabic deliver.

Squiggly lines and dots?

It started with the script. A lot of people are put off by Arabic’s script, because it looks so impenetrable — all those squiggly lines and dots. At least if you are unfamiliar with Italian you can still make out some of the words. However, the script is really perfectly simple, and anyone can learn it in an hour or two. Arabic has 28 letters, some for sounds that don’t exist in English (and learning to pronounce these can be tricky and cause for much hilarity, like the ‘ayn which I saw most accurately described as “imagine you are at the dentist and the drill touches a nerve”), some handily combining a sound for which English needs two letters into one, like th and sh. Vowels aren’t usually written, only consonants. The dots are to distinguish between letters which have the same basic shape. And the reason it all looks so squiggly is that letters within one word are joined up, like cursive. Once you can see that, it all becomes a lot more transparent.

So once we mastered the script, after the first day of university, things got really interesting. The script unlocked a whole new world of language, and a fascinating language it was. Arabic is a Semitic language, which places it outside the Indo-European language family, and Semitic languages have some unique properties that I had never imagined.

Quran Pak by Shakreez. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Quran Pak by Shakreez. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Root-and-pattern

For example, Arabic (and other Semitic languages) has a so-called “root-and-pattern” morphology. This means that every word is built up of a root, usually consisting of three consonants, which carries the basic meaning of that word; for example the root KTB, with basic meaning “writing”, or DRS “studying”. This root is then put in a pattern consisting of vowels and affixes, which manipulate its meaning to form a word. For example, *aa*i* means “the person who does something”, so a KaaTiB is “someone who writes”: a writer; and a DaaRiS is “someone who studies”: a researcher. Ma**a* means “the place where something takes place”, so a maKTaB is an office, a maKTaBa a library or bookshop, a maDRaSa a school.

This makes learning vocabulary both harder and easier. On the one hand, in the beginning all words sound the same — all verbs have the pattern *a*a*a: KaTaBa, BaHaTHa, DaRaSa, HaDaTHa, JaMaʿa — and you may well get utterly confused. But after a while, you get used to it, and if you encounter a new word and are familiar with the root and recognize the pattern, you can at least make an educated guess at what it might mean.

Keeping things logical . . . usually

Another wonderful aspect of Arabic is that it doesn’t have irregular verbs, unlike, for example, French (I’m looking at you pouvoir). But before you all throw out your French text books and switch to Arabic, let me warn you that there are about 250 different types of regular verb, each of which conjugates into 110 forms. This led to Guy Deutscher remarking, “if the Latin verbal system looked uncomfortably complex, here is an example which makes Latin seem like child’s play: the verbal system of the Semitic languages, such as Arabic, Aramaic and Hebrew.” Fair enough, it’s complex, but it’s all logical, and regular. I, for one, had much less trouble learning these Arabic verbs than the Latin and French ones, simply because there is such an elegant method to them.

There are other aspects of Arabic that are less logical. The numbers, for instance. I won’t go too deep into them, but suffice it to say that if you have three books the three is feminine because books are masculine and if you have three balls it’s vice versa, and then if you have thirteen of something the three is the opposite gender but the ten is the same, the counted word is suddenly singular and for no reason at all the whole lot has become accusative. Then at twenty it all changes again. It’s a wonder the Arab world proved so proficient in mathematics.

Other reasons to learn Arabic

Which leads me to the many other reasons one might want to learn Arabic. I focused on its fascinating linguistics above, because that is my personal favorite field, but there are the cultures steeped in rich history, the fascinating literature ranging from ancient poetry to cutting-edge modern novels, and of course the fact that every Muslim must know at least a little bit of Arabic in order to fulfill their religious duties (shahada, Fatiha, and salat), and for gleaning a deep understanding of the sources of Islam, Arabic is essential. Arabic is also a very wanted skill in many professions, and not just the obvious ones. I recall one of the recruiters at the Arabists’ Career Fair, speaking for a law firm, stating, “We can teach you law. Law is easy. What we need are people with a firm knowledge of Arabic.”

Featured image credit: Learning Arabic calligraphy by Aieman Khimji. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why learn Arabic? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesQuebec French and the question of identityTranslating untranslatable wordsDoing things with verve

Related StoriesQuebec French and the question of identityTranslating untranslatable wordsDoing things with verve

Does industry sponsorship restrict the disclosure of academic research?

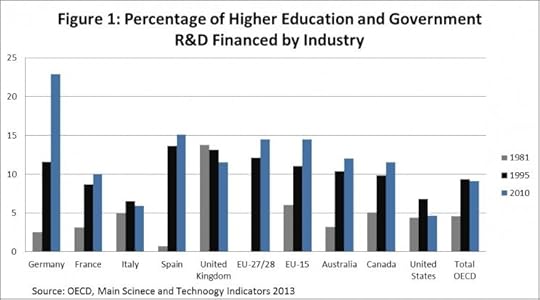

Long-run trends suggest a broad shift is taking place in the institutional financing structure that supports academic research. According to data compiled by the OECD reported in Figure 1, industry sources are financing a growing share of academic research while “core” public funding is generally shrinking. This ongoing shift from public to private sponsorship is a cause for concern because these sponsorship relationships are fundamentally different. Available evidence suggests that industry financing does not simply replace dwindling public money, but imposes additional restrictions on academic researchers. In particular, industry sponsors frequently limit disclosure of research findings, methods, or materials by delaying or banning public release.

Recent economic research highlights why public disclosure of academic research is important. Disclosure permits the stock of public knowledge to be cumulative, accessible, and reliable. It limits duplication of research efforts, allows new knowledge to be replicated and verified by professional peers, and permits access and use by other researchers which enhances opportunities for complementary research. Some work finds that greater access to ideas and materials in academic research not only increased incentives for direct follow-on research, but led to an increase in the diversity of research by increasing the number of experimental research lines. Other work, examining the theoretical conditions supporting “open science” versus “secrecy”, stressed that maintaining and growing the stock of public knowledge requires a limit on the private financial returns obtained through secrecy.

To better understand the potential implications of increased industry funding, we implemented a research project that examined the relationship between industry sponsorship and restrictions on publication disclosure using individual-level data on German academic researchers. Germany is an apt setting for examining this relationship. It has a strong tradition of public financial support for academic research and, according to the OECD, Germany experienced the most dramatic growth in its share of industry sponsorship, an 11.3 percentage point increase from 1995 to 2010 (see Figure 1).

German academic researchers were surveyed about the degree of publication disclosure restrictions experienced during research projects sponsored by government, foundations, industry, and other sources. To examine if industry sponsorship jeopardizes disclosure of academic research, we modeled the degree of restrictiveness (i.e. delay and secrecy) as a function of the researcher’s budget share financed by industry. This formulation allows us to examine two potential effects of industry sponsored research contracts. The first is an adoption effect that takes place when academic researchers commit to industry funding. The second is an intensity effect that captures how publication restrictions depend on the researcher’s exposure to greater ex post review and evaluation by industry sponsors. Our models include covariates that control for non-industry extramural sponsorship, personal characteristics, research characteristics, institutional affiliations, and scientific fields of study.

Both the descriptive and regression results show a positive relationship between the degree of publication restrictions and industry sponsorship. The percentage of respondents who reported higher secrecy (partial or full) is significantly larger for industry sponsored researchers than it is for researchers with other extramural sponsors, 41% and 7% respectively. Controlling for selection, adopting industry sponsorship more than doubles the expected probabilities of publication delay and secrecy. The intensity effect is positive and significant with a larger effect on publication secrecy than on publication delay when academic researchers become heavily supported by industrial firms. These results are robust to the possibility that researchers self-select into extramural sponsorship and to the possibility that the share of industry sponsorship is endogenous due to unobserved variables.

Based on our analysis, the shift from public to private sponsorship seen in the OECD aggregate data reflects changes in the microeconomic environment shaping incentives for disclosure by academic researchers. On average, academic researchers are willing to restrict disclosure in exchange for financial support by industry sponsors. Our results shed light on an important challenge facing policymakers. Understanding the trade-off between public and private sponsorship of academic research involves gauging the impact of disclosure restrictions on the quantity, quality, and evolution of academic research to better understand how these restrictions may ultimately influence innovation and economic growth.

Image credit: Computer research, © Jürgen François, via iStock Photo.

The post Does industry sponsorship restrict the disclosure of academic research? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe road to egalitariaUnited Airlines and Rhapsody in BlueThe burden of guilt and German politics in Europe

Related StoriesThe road to egalitariaUnited Airlines and Rhapsody in BlueThe burden of guilt and German politics in Europe

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers