Oxford University Press's Blog, page 763

September 14, 2014

What would an independent Scotland look like?

The UK Government will no doubt be shocked if the referendum on 18 September results in a Yes vote. However, it has agreed to respect the outcome of the referendum and so we must assume that David Cameron will accept the Scottish Government’s invitation to open negotiations towards independence.

The first step will be the formation of two negotiating teams — Team Scotland and Team UK, as it were. These will be led by the governments of both Scotland and the UK, although the Scottish Government has indicated that it wants other political parties in Scotland to join with it in negotiating Scotland’s position. We would expect high level points to be set out by the governments, the detail to be negotiated by civil servants.

The Scottish Government anticipates a 19 month process between a Yes vote and a formal declaration of independence in March 2016.

What then would an independent Scotland look like?

The Scottish Government plan is for an interim constitution to be in place after March 2016 with a permanent constitution to be drafted by a constitutional convention composed of representatives of civil society after Scottish elections in May 2016.

The Scottish Government intends that the Queen will remain head of state. But this and other issues would presumably be up to the constitutional convention to determine in 2016.

Similarly the Scottish Parliament will continue to be a one chamber legislature, elected by proportional representation, a model rejected by UK voters for Westminster of course in a referendum in 2011.

The Scottish Government seeks to keep the pound sterling as the currency of an independent Scotland. The UK Government’s position is that Scotland can use the pound but that there will be no formal currency union. After a Yes vote this position could change but the unionist parties are united in denying any such possibility.

The UK has heavily integrated tax, pension, and welfare systems. It will certainly be possible to disentangle these but it may take longer than 19 months. In the course of such negotiations both sides may find that it makes sense to retain elements of close cooperation in the social security area, at least in the short to medium term.

Flags outside Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh by Calum Hutchinson. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Flags outside Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh by Calum Hutchinson. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons. The Scottish Government has put forward a vision of Scotland as a social democracy. It will be interesting if it follows through on plans to enshrine social rights in the constitution, such as entitlements to public services, healthcare, free higher education, and a minimum standard of living. The big question is: can Scotland afford this? It would seem that a new tax model would be needed to fund a significantly higher commitment to public spending.

A third area of great interest is Scotland’s position in the world. One issue is defense. The SNP promises a Scotland free of nuclear weapons, including the removal of Trident submarines from the Clyde. This could create difficulties, both for Scotland in seeking to join NATO, but also for the remainder UK, which would need to find another base for Trident. The Scottish Government rejects firmly that it will be open to a deal on Trident’s location in turn for a currency union with London, but this may not be out of the question.

Another issue is that the Scottish Government takes a much more positive approach to the European Convention on Human Rights, than does the current UK government. In fact, the proposal is that the European Convention will become supreme law in Scotland, which even the Scottish Parliament could not legislate against. This contrasts with the current approach of the Conservative Party, and to some extent the Labour Party, in London which are both proposing to rebalance powers towards the UK Parliament and away from the European Court in Strasbourg.

Turning to the European Union, it seems clear to me that Scotland will be admitted to the EU but that the EU could drive a hard bargain on the terms of membership. Compromises are possible. Scotland does not, at present, qualify for, and in any case there is no appetite to join, the Eurozone, so a general commitment to work towards adopting the Euro may satisfy the EU. The Scottish Government also does not intend to apply for membership of the Schengen Area but will seek to remain a part the Common Travel Area, which would mean no borders and a free right to travel across the British and Irish isles.

The EU issue is also complicated because the UK’s own position in Europe is uncertain. Will the UK stay in the EU? The prospect of an in/out referendum after the next UK general election is very real. Another issue is whether an independent Scotland would gradually develop a much more pro-European mentality than we see in London. Would Scotland become positive rather than reluctant Europeans, and would Scotland seek to adopt the Euro in the medium to longer term? We don’t know for now. But if the UK votes to leave the EU, then this may well be the only option open to an independent Scotland in Europe.

To conclude, a written constitution, a stronger commitment to European human rights standards, a more pro-European Union attitude, and an attempt to build a more social welfarist state could bring about an independent Scotland that looks very different from the current UK. However, the bonds of union run deep, and if Scotland does achieve a currency union with the UK it will be tied closely to London’s tax structure. In such a scenario the economies, and therefore the constitutions, of the two countries, will surely continue to bear very many similarities. Much also depends upon relationships with the European Union. If the UK stays in the EU then Scotland and the UK could co-exist with a sterling currency union and a free travel area. If the UK votes to leave then Scotland will need to choose whether to do likewise or whether to align much more closely with Europe.

The post What would an independent Scotland look like? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?Should Scotland be an independent country?Why Scotland should get the government it votes for

Related StoriesThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?Should Scotland be an independent country?Why Scotland should get the government it votes for

Out with the old?

Innovation is a primary driver of economic growth and of the rise in living standards, and a substantial body of research has been devoted to documenting the welfare benefits from it (an example being Trajtenberg’s 1989 study). Few areas have experienced more rapid innovation than the Personal Computers (PC) industry, with much of this progress being associated with a particular component, the Central Processing Unit (CPU). The past few decades had seen a consistent process of CPU innovation, in line with Moore’s Law: the observation that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles every 18-24 months (see figure below). This remarkable innovation process has clearly benefitted society in many, profound ways.

“Transistor Count and Moore’s Law – 2011″ by Wgsimon – Own work. CC-BYSA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Transistor Count and Moore’s Law – 2011″ by Wgsimon – Own work. CC-BYSA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. A notable feature of this innovation process is that a new PC is often considered “obsolete” within a very short period of time, leading to the rapid elimination of non-frontier products from the shelf. This happens despite the heterogeneity of PC consumers: while some (e.g., engineers or gamers) have a high willingness-to-pay for cutting edge PCs, many consumers perform only basic computing tasks, such as word processing and Web browsing, that require modest computing power. A PC that used to be on the shelf, say, three years ago, would still adequately perform such basic tasks today. The fact that such PCs are no longer available (except via a secondary market for used PCs which remains largely undeveloped) raises a natural question: is there something inefficient about the massive elimination of products that can still meet the needs of large masses of consumers?

Consider, for example, a consumer whose currently-owned, four-year old laptop PC must be replaced since it was severely damaged. Suppose that this consumer has modest computing-power needs, and would have been perfectly happy to keep using the old laptop, had it remained functional. This consumer cannot purchase the old model since it has long vanished from the shelf. Instead, she must purchase a new laptop model, and pay for much more computing power than she actually needs. Could it be, then, that some consumers are actually hurt by innovation?

A natural response to this concern might be that the elimination of older PC models from the shelves likely indicates that demand for them is low. After all, if we believe in markets, we may think that high levels of demand for something would provide ample incentives for firms to offer it. This intuition, however, is problematic: as shown in seminal theoretical work by Nobel Prize laureate Michael Spence, the set of products offered in an oligopoly equilibrium need not be efficient due to the misalignment of private and social incentives. The possibility that yesterday’s PCs vanish from the shelf “too fast” cannot, therefore, be ruled out by economic theory alone, motivating empirical research.

A recent article addresses this question by applying a retrospective analysis of the U.S. Home Personal Computer market during the years 2001-2004. Data analysis is used to explore the nature of consumers’ demand for PCs, and firms’ incentives to offer different types of products. Product obsolescence is found to be a real issue: the average household’s willingness-to-pay for a given PC model is estimated to drop by 257 $US as the model ages by one year. Nonetheless, substantial heterogeneity is detected: some consumers’ valuation of a PC drops at a much faster rate, while from the perspective of other consumers, PCs becomes “obsolete” at a much lower pace.

Laptop and equipment. Public domain via Pixabay.

Laptop and equipment. Public domain via Pixabay. The paper focuses on a leading innovation: Intel’s introduction of its Pentium M® chip, widely considered as a landmark in mobile computing. This innovation is found to have crowded out laptops based on older Intel technologies, such as the Pentium III® and Pentium 4®. It is also found to have made a substantial contribution to the aggregate consumer surplus, boosting it by 3.2%- 6.3%.

These substantial aggregate benefits were, however, far from being uniform across different consumer types: the bulk of the benefits were enjoyed by the 20% least price-sensitive households, while the benefits to the remaining 80% were small and sometimes negligible. The analysis also shows that the benefits from innovation could have “trickled down” to the masses of price-sensitive households, had the older laptop models been allowed to remain on the shelf, alongside the cutting-edge ones. This would have happened since the presence of the new models would have exerted a downward pressure on the prices of older models. In the market equilibrium, this channel is shut down, since the older laptops promptly disappear.

Importantly, while the analysis shows that some consumers benefit from innovation much more than others, no consumers were found to be actually hurt by it. Moreover, the elimination of the older laptops was not found to be inefficient: the social benefits from keeping such laptops on the shelf would have been largely offset by fixed supplier costs.

So what do we make of this analysis? The main takeaway is that one has to go beyond aggregate benefits and consider the heterogeneous effects of innovation on different consumer types, and the possibility that rapid elimination of basic configurations prevents the benefits from trickling down to price-sensitive consumers. Just the same, the paper’s analysis is constrained by its focus on short-run benefits. In particular, it misses certain long-term benefits from innovation, such as complementary innovations in software that are likely to trickle down to all consumer types. Additional research is, therefore, needed in order to fully appreciate the dramatic contribution of innovation in personal computing to economic growth and welfare.

The post Out with the old? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIncreasing income inequalityDoes industry sponsorship restrict the disclosure of academic research?The road to egalitaria

Related StoriesIncreasing income inequalityDoes industry sponsorship restrict the disclosure of academic research?The road to egalitaria

September 13, 2014

Is Arabic really a single language?

All language-learners face the difficulties of regional variations or dialects. Usually, it takes the form of an odd word or turn of phrase or a peculiar pronunciation. For most languages, incomprehension is only momentary, and the similarity — what linguists often refer to as the mutual intelligibility — between the standard language taught to foreigners and the regional speech pattern is maintained. For a language such as French, only the most extreme cases of dialectical differences, such as between Parisian and Québécois or Cajun, pose considerable difficulties for both learners and native speakers of dialects close to the standard. For other languages, however, differences between dialects are so great as to make most dialects other than the standard totally incomprehensible to learners. Arabic is one such language.

The problem that faces most learners of Arabic is that the written language is radically different from the various dialects spoken throughout the Arab world. Such differences appear in a variety of forms: pronunciation, vocabulary, syntax, and tenses of verbs. The result is that even the most advanced learner of standard Arabic (or ‘the standard’) might find herself completely at sea on the streets of Beirut, while it is also conceivable for a student to complete a year of immersion in Cairo and not be able to understand a text written in the standard language.

The most diligent and ambitious of Arabic students, therefore, is required to learn both the standard and a regional variant in order to cover all the social situations in which they might use the language. This, however, will not solve their dilemma in its entirety: Moroccan Arabic is foreign to Levantines, while Iraqi can be quite a puzzle for Egyptians. Even the mastery of a regional variant along with the standard will only ease the learner’s task in part of the Arab World, while making it no easier in other regions. This phenomenon, in which a number of quasi- or poorly-intelligible dialects are used by speakers of a particular language depending on the situation in which they find themselves, is known as diglossia.

Two pages from the Galland manuscript, the oldest text of The Thousand and One Nights. Arabic manuscript, back to the 14th century from Syria in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. A many-headed beast

Two pages from the Galland manuscript, the oldest text of The Thousand and One Nights. Arabic manuscript, back to the 14th century from Syria in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. A many-headed beast The source, or rather sources, of diglossia in the Arab world are both manifold and contentious. In part, regional differences come about from contact between Arabic speakers and non-Arabic speakers. Moroccan Arabic, for example, borrows from Berber, while Levantine dialects (spoken in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, and Jordan) have Aramaic elements in them. The dialects of the Persian Gulf area show the influence of Persian and Hindi, both of which were the languages of important trading partners for the region’s merchants. Finally, the languages of imperial or colonial administration left their imprint on virtually all dialects of the Arab World, albeit in different measures. It is for this reason that native speakers may choose from a variety of words, some foreign and others Arabic, in order to describe the same concept. Thus a Moroccan might use henna (from Berber) or jidda for grandmother; a Kuwaiti might buy meywa (from Farsi) or fawaakih when he has a craving for fruit; and a Lebanese worker might say she is going to the karhane (from Ottoman Turkish) or masna` when heading off to the factory.

Dialectical differences are not just a matter of appropriations and borrowings. Just as many non-native learners have grappled with the complex structure of the Arabic language, so too have many native speakers of Arabic. For all its complexity, however, there are certain nuances that standard Arabic does not express with efficiency or ease. This is why the regional dialects are marked by a number of simplifications and innovations, intended to allow for greater agility and finesse when speaking.

For example, Levantine dialects make use of agent participles (faakira, the one thinking; raayihun, the ones going; maashi, the one walking) instead of actually conjugating the verb (‘afkuru, I am thinking; yaruuhuuna, they are going; tamshiina, you are going). However, these same dialects, as well as Egyptian, have also created a series of verbal prefixes — small non-words that come before the conjugated verb — in order to refine the duration and timing of an action when conjugated verbs are used: baya’kal, he eats; `am baya’kal, he is eating; raH ya’kal or Ha ya’kal, he will eat. Such distinctions are familiar to speakers of English, but are not immediately apparent in Arabic, whose verbal system seeks to stress other types of information.

The more the merrierIndeed, this display of innovation and human creativity is one of the strongest motivations for learning Arabic, whether standard or colloquial. Arabic might require as much effort and commitment as the acquisition of two or three Indo-European languages in order for a non-native speaker to be able to communicate in a meaningful way. However, it also opens the door to understanding the manner in which humans use and adapt language to their particular contexts. The diglossia issue is one that causes complications for non-native learners and native Arabic speakers alike, but it is also a fascinating showcase of the birth and evolution of languages that challenges our preconceived notions about good and bad speech, and the relative importance and value of dialects.

Heading image: Golden calligraphy by Quinn Dombrowski, CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Is Arabic really a single language? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy learn Arabic?Quebec French and the question of identityThe victory of “misgender” – why it’s not a bad word

Related StoriesWhy learn Arabic?Quebec French and the question of identityThe victory of “misgender” – why it’s not a bad word

Eight facts on the history of pain management

September is Pain Awareness Month. In order to raise awareness of the issues surrounding pain and pain management in the world today, we’ve taken a look back at pain throughout history and compiled a list of the eight most interesting things we learned about pain from The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers by Joanna Bourke.

In the past, pain was most often described as an independent entity. In this way, pain was described as something separate from the physical body that might be able to be fought off while keeping the self intact. In India and Asia some descriptions of varying degrees of pain involved animals. Some examples include “bear headaches,” that resemble the heavy steps of a bear, “musk deer headaches” like the galloping of a running dear, and “woodpecker headaches” as if pounding into the bark of a tree. In the late twentieth century, children’s sensitivity to pain was debated. There were major differences in the beliefs of how children experienced pain. 91 % of pediatricians believing that by the age of two a child experienced pain similarly to adults, compared with 77% of family practitioners, and only 59% of surgeons. It had long been observed that, in the heat of battle, even severe wounds may not be felt. In the words of the principal surgeon to the Royal Naval Hospital at Deal, writing in 1816, seamen and soldiers whose limbs he had to amputate because of gunshot wounds “uniformly acknowledged at the time of their being wounded, they were scarcely sensible of the circumstance, till informed of the extent of their misfortune by the inability of moving their limb.” Prior to 1846, surgeons conducted their work without the help of effective anesthetics such as ether or chloroform. They were required to be “men of iron … and indomitable nerve” who would not be “disturbed by the cries and contortions of the sufferer.” Concerns about medical cruelty reached almost hysterical levels in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, largely as a consequence of public concern about the practice of vivisection (which was, in itself, a response to shifts in the discourse of pain more widely). It seemed self-evident to many critics of the medical profession that scientists trained in vivisection would develop a callous attitude towards other vulnerable life forms. In the 19th century it was believed that pain was a necessary process in curing an ailment. In the case of teething infants, lancing their gums or bleeding them with leeches were painful treatments used to reduce inflammation and purge the infant-body of its toxins. John Bonica, an anesthetist and chronic pain suffer himself, established the first international symposium on pain research and therapy in 1973, which resulted in the founding of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).Featured image credit: The Physiognamy of Pain, from Angelo Mosso, Fear (1896), trans. E. Lough and F. Kiesow (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1896), 202, in the Wellcome Collection, L0072188. Used with permission.

The post Eight facts on the history of pain management appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe story of pain in picturesThe truth about evidenceAddressing the true enemies of humankind

Related StoriesThe story of pain in picturesThe truth about evidenceAddressing the true enemies of humankind

Should Scotland be an independent country?

On 18 September 2014 Scots will vote on the question, ‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’

Campaigners for independence and campaigners for the union agree that this is an historic referendum. The question suggests a simple choice between different states. This grossly over-simplifies a complex set of issues and fails to take account of a range of other debates that are taking place in Scotland’s ‘constitutional moment’.

Four cross-cutting issues lie behind this referendum. National identity is but one. If it was simply a matter of identity then supporters of independence would be well ahead. But identities do not translate into constitutional preferences (or party political preferences) in straightforward ways. In the 2011 Scottish Parliament elections more people who said they were ‘British and not Scottish’ voted for the Scottish National Party than voted Tory. Scottish identity has survived without a Scottish state and no doubt Britishness will survive without a British state. Nonetheless, the existence of a sense of a Scottish political entity is important in this referendum.

Party politics, and especially the party systems, also play a part in the referendum. Conservative Party weakness – and latterly the weakness of UKIP in Scotland – north of the border has played into the sense that Scotland is politically divergent. This trend was highlighted by William Miller in a book, entitled The End of British Politics?, written more than thirty years ago. It has not been the geographic distance of London from the rest of the UK so much as the perceived ideological distance that has fuelled demands for Scottish autonomy. Polls continue to suggest that more people would be inclined to vote for independence if they thought Mr Cameron and his party were likely to win next year’s general election and elections into the future than if Labour was to win. It is little wonder that Mr Cameron refuses to debate with Mr Salmond.

Alex Salmond. Photo By Harris Morgan. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Alex Salmond. Photo By Harris Morgan. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons The dynamics of party politics differ north and south of the border. Each side in the referendum campaign works on the assumption that membership of the EU is in Scotland’s interest, suggesting that Scotland will find itself outside the EU if the other wins while a very different dynamic operates south of the border. Debates in immigration and welfare differ on each side of the border. While there is polling evidence that public attitudes on a range of matters differ only marginally north and south of the border, the much harder evidence from election results, evident in the recent uneven rise of UKIP, suggests something very different.

It is not only that different parties might govern in London and Edinburgh but that the policies pursued differ, the directions of travel are different. In this respect, policy initiatives pursued in the early years of devolution, when Labour and the Liberal Democrats controlled the Scottish Parliament, have fed the sense of divergence. The SNP Government has only added – and then only marginally – to this divergence. The big items that signalled that Holyrood and Westminster were heading in different policy directions were tuition fees and care for the elderly. These were policies supported by all parties in Holyrood, including the then governing Labour Party and Liberal Democrats. There is fear in parts of Scotland that UK Governments will dismantle the welfare state while Scots want to protect it.

The constitutional status of Scotland is now the focus of debate. This is not new nor will the referendum resolve this matter for all time, regardless of the result of the referendum. Each generation has to consider the relationship Scotland has with London, the rest of the UK, and beyond. This is currently a debate about relationships, articulated in terms of whether Scotland should be an independent country. Relationships change as circumstances change. The backdrop to these changing relationships has been the party system, public policy preferences and identities. The role and remit of the state and the nature of Scotland’s economy and society have changed and these changes have an impact on the constitutional debate.

Adding to the complexity has been a development few had anticipated. Both sides to the debate report large turnouts at public meetings, engagement we have not witnessed in a long time with a far wider range of issues arising during Scotland’s constitutional moment than might have been suggested by that simple question to be asked on September 18th. Prospectuses on the kind of Scotland people want are being produced. This revival of political engagement may leave a legacy that reverses a trend that has seen decline in turnout, membership of political parties and civic engagement. That would make this referendum historic.

The post Should Scotland be an independent country? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?Why Scotland should get the government it votes forEarthquake at the lightning huaca of San Catequilla de Pichincha

Related StoriesThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?Why Scotland should get the government it votes forEarthquake at the lightning huaca of San Catequilla de Pichincha

Playing Man: some modern consequences of Ancient sport

Playing Man (Homo Ludens), the trail-blazing work by Johan Huizinga, took sport seriously and showed how it was essential in the formation of civilizations. Adult playtime for many pre-industrial cultures served as the crucible in which conventions and boundaries were written for a culture. Actions were censured for being “beyond the pale”, a sports metaphor for being “out of bounds”.

A quasi-sacred time and space set apart for games were a microcosm for the lives of all who played and for the spectators. Sport was a place in which individual merit was the rule and performance was regulated by the terms of the event.

The Ancient Olympic Games, an invention of the 700s BCE, preceded Athenian Democracy by about 200 years, and yet those earliest Games allowed any free citizen to participate and win the supreme Panhellenic crown. Yes, probably most of the first contenders were wealthy by token of having more leisure time to train and travel to the festival.

Yet in the pre-democratic centuries, the sporting model showed that what counted was individual ability and acquired skill, not status by birth. So the era of rule by tyrants and elite families was balanced by models of egalitarian display in the stadium in footraces, wrestling, boxing, and other track and field events.

Chariot racing was of course still the exclusive domain of the wealthy, a vestige of heroic tradition, but the athletes contending mano a mano ushered in more meritocratic ways. The Greek custom of requiring athletes in track and field and combat events to participate in the nude underscored this democratic ethos, perhaps popularized among the communally oriented Spartans by 600 BCE, but soon adopted universally by all Greeks.

The double entendre in my title “playing man” is intentional, with allusion to the sense that sport has been for most of history and globally a performance by and for males. For the Greeks, athletics were for men only, with a few interesting exceptions, notably girls’ ritual races at Olympia to ask Hera for a happy marriage.

In the modern Olympics, there was no women’s marathon race until 1984, almost 90 years into the games. Even then, in 1984, only 25% of all Olympic participants were female; today it is still at less than half (45% in 2012). The first women boxing events came in 2012.

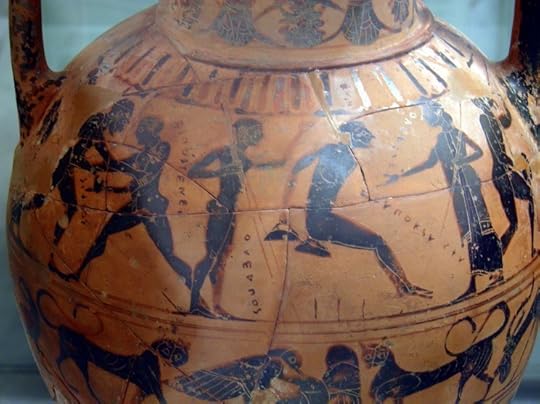

A competitor in the long jump, Black-figured Tyrrhenian amphora showing athletes and a combat scene, Greek, but made for the Etruscan market, 540 BC, found near Rome, Winning at the ancient Games, British Museum. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A competitor in the long jump, Black-figured Tyrrhenian amphora showing athletes and a combat scene, Greek, but made for the Etruscan market, 540 BC, found near Rome, Winning at the ancient Games, British Museum. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Women’s participation in sports at all venues and events has slowly improved over the last 30 years, thanks to gender equity movements as a whole. Still, males have been the participants in and the most avid audiences for competitive sports globally throughout history.

Is it tradition and culture or nature (testosterone and men’s greater muscle bulk) that has driven this trend? Scholarly disagreement continues, but the answer must include nature and culture, with nature perhaps playing a heavier role. The attempts to bring women’s sports to the fore have largely not succeeded: world viewers, broadcasters, and corporate sponsors overwhelmingly prefer male contests.

Overt displays of machismo characterized the ancient Greek contest, or agôn, whence our term agony, the pain of struggle. Combat sports of boxing and wrestling topped the popularity charts and the rewards at the festivals that gave valuable prizes.

At the Olympics, there were no second or third place prizes; only first counted, and one boxer said “give me the wreath of give me death”. Many were brutalized or killed, as is shown on vases in which blood streams from the contestants.

The Greeks were overly familiar with violence meted out by men in war on a daily basis, and so violent sport here did not inspire violence. But the association of athletes with Homeric heroes maintained the display as acceptable and even superhuman (see the funeral games of Iliad 23).

Greek sport, then, is worthy of our attention as the model in many ways for our own very different contests. Yes, the modern Olympics appropriated the Greek ones for its own very different aims. But arguably the ‘deeper’ social inheritances from the Greek men who “played” are, on the one hand, a greater egalitarianism, and on the other a heroized violence and machismo with which we all still wrestle.

The post Playing Man: some modern consequences of Ancient sport appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEarthquake at the lightning huaca of San Catequilla de Pichincha“Young girl, I declare you are not like most men”: retranslating The Poetic EddaThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?

Related StoriesEarthquake at the lightning huaca of San Catequilla de Pichincha“Young girl, I declare you are not like most men”: retranslating The Poetic EddaThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?

September 12, 2014

Why Scotland should get the government it votes for

I want an independent Scotland that is true to the ideals of egalitarianism articulated in some of the best poetry of Robert Burns. I want a pluralist, cosmopolitan Scotland accountable to its own parliament and allied to the European Union. My vote goes to Borgen, not to Braveheart. I want change.

Britain belongs to a past that is sometimes magnificent, but is a relic of empire. Scotland played its sometimes bloody part in that, but now should get out, and have the courage of its own distinctive convictions. It is ready to face up to being a small nation, and to get over its nostalgia for being part of some supposed ‘world power’. No better, no worse than many other nations, it is regaining its self-respect.

Yet the grip of the past is strong. Almost absurdly emblematic of the complicated state of 2014 Scottish politics is Bannockburn: seven hundred years ago Bannockburn, near Stirling in central Scotland, was the site of the greatest medieval Scottish victory against an English army. Today Bannockburn is part of a local government zone controlled by a Labour-Conservative political alliance eager to defeat any aspirations for Scottish independence. In the summer of 2014 Bannockburn was the site of a civilian celebration of that 1314 Scottish victory, and of a large-scale contemporary British military rally. The way the Labour and Conservative parties in Scotland are allied, sometimes uneasily, in the ‘Better Together’ or ‘No’ campaign to preserve the British Union makes Scotland a very different political arena from England where Labour is the opposition party fighting a Conservative Westminster government. England has no parliament of its own. As a result, the so-called ‘British’ Parliament, awash with its Lords, with its cabinet of privately educated millionaires, and with all its braying of privilege, spends much of its time on matters that relate to England, not Britain. This is a manifest abuse of power. The Scottish Parliament at Holyrood looks – and is – very different.

Scottish Parliament Building. © andy2673 via iStock.

Scottish Parliament Building. © andy2673 via iStock. Like many contemporary Scottish writers and artists, I am nourished by traditions, yet I like the idea of change and dislike the status quo, especially the political status quo. National identity is dynamic, not fixed. Democracy is about vigorous debate, about rocking the boat. Operating in an atmosphere of productive uncertainty is often good for artistic work. Writers enjoy rocking the boat, and can see that as a way of achieving a more egalitarian society. That’s why most writers and artists who have spoken out are on the ‘Yes’ side. If there is a Yes vote in the Scottish independence referendum on 18 September 2014, it will be a clear vote for change. If there is a ‘No’ vote, it will be because of a strong innate conservatism in Scottish society – a sense of wanting to play it safe and not rock the boat. Whether Scotland’s Labour voters remain conservative in their allegiances and vote ‘No’, or can be swayed to vote ‘Yes’ because they see the possibility of a more egalitarian future — is a key question.

As we get nearer and nearer to the date of the Scottish independence referendum on 18 September, I expect there will be an audible closing of ranks on the part of the British establishment. Already in July we have had interventions from the First Sea Lord (who gave a Better Togetherish speech at the naming ceremony for an aircraft carrier), and a lot of money from major landowners and bankers has been swelling the coffers of those opposed to independence. In Glasgow it was good to read at an event with Liz Lochhead, Kathleen Jamie, Alasdair Gray, and other poets and novelists in support of independence. This is a very exciting time for Scotland, a time when relationships with all kinds of institutions are coming under intense scrutiny. Whatever happens, the country is likely to emerge stronger, and with an intensified sense of itself as a democratic place.

The post Why Scotland should get the government it votes for appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?The Dis-United KingdomAddressing the true enemies of humankind

Related StoriesThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?The Dis-United KingdomAddressing the true enemies of humankind

Addressing the true enemies of humankind

One hundred years ago, World War I began — the “Great War,” the war “to end all wars.” A war that arose from a series of miscalculations after the assassination of two people. A war that eventually killed 8 million people, wounded 21 million, and disabled millions more — both physically and mentally.

That war sowed the seeds for an even greater war starting two decades later, a war that killed at least 60 million people (45 million of them civilians), wounded 25 million in battle, and disabled many more — a war that led to the development, use, large-scale production, and deployment of nuclear weapons.

Since then, there have been dozens more wars and the continuing threat of thermonuclear war. Statistics reflect the millions of people killed and injured. These statistics are too staggering for us to comprehend, ever more staggering when we realize that these statistics are people with the tears washed off.

It would be nice to think that we, as a global society, had learned the lessons of war and other forms of “collective violence” over the past century. However, although there is evidence that there are fewer major wars today, armed conflict and other forms of collective violence do not seem be abated. The international trade and widespread availability of “conventional weapons,” generations-long ethnic conflict, competition for control of scarce mineral resources, and socioeconomic inequalities and other forms of social injustice fuel this violence.

All too often violence seems to be the default mode of settling disputes between nations. All too often violence, in one form or another, seems to be the way that the powerful maintain power, and the way that the powerless seek it. All too often violence or the threat of violence seems to be the way that national governments — and even law enforcement officers — attempt to maintain security — and the way that “non-state actors” attempt to undermine it.

A young boy sits over an open sewer in the Kibera slum, Nairobi. By Trocaire. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A young boy sits over an open sewer in the Kibera slum, Nairobi. By Trocaire. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. As we have witnessed over the past several decades, national and international security cannot be maintained over the long term by violence or the threat of violence. National and international security is more likely to be sustained by promoting socioeconomic equalities, social justice, and public participation in government; ensuring educational and employment opportunities for all; protecting human rights and ensuring that the basic needs of everyone are met; and addressing the true enemies of humankind: poverty, hunger, and disease.

Enemy #1: Poverty. More than 46 million people in the United States live below the poverty line, the largest number in the 54 years that the Census has measured poverty. More than 21 million children live in poverty in this country. Globally, about half of the world’s population lives on less than $2.50 a day. Poverty is an insidious enemy that robs people of opportunity and worsens their health.

Enemy #2: Hunger. About one out of seven US households are considered “food insecure.” Globally, more than 800 million — one-fourth of people in sub-Saharan Africa — do not have enough to eat. Hunger is a widespread enemy that saps children and adults of their physical and mental capabilities and predisposes them to disease.

Enemy #3: Disease. In the United States, preventable physical and mental illnesses account for much morbidity and mortality. Globally, this is even more true. For example, each year about four million people die of acute respiratory infections, and 1.5 million children die from diarrheal diseases due to unsafe water, inadequate sanitation, and poor hygiene. New types of infectious agents and micro-organisms resistant to antibiotics continue to emerge. And the Ebola virus is rapidly spreading across several West African countries.

These are the true enemies of humankind.

One hundred years from now, what will people, in 2114, say when they look back on these times? Will they say that we failed to learn the lessons of the previous one hundred years and continued to wage war and other forms of violence? Or will they say that we, as a global society, created a culture of peace in which we resolved disputes non-violently and in which we addressed the true enemies of humankind?

Heading image: Urban Poverty by Nikkul. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Addressing the true enemies of humankind appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe truth about evidenceThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?A First World War reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Related StoriesThe truth about evidenceThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?A First World War reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

The truth about evidence

Rated by the British Medical Journal as one of the top 15 breakthroughs in medicine over the last 150 years evidence-based medicine (EBM) is an idea that has become highly influential in both clinical practice and health policy-making. EBM promotes a seemingly irrefutable principle: that decision-making in medical practice should be based, as much as possible, on the most up-to-date research findings. Nowhere has this idea been more welcome than in psychiatry, a field that continues to be dogged by a legacy of controversial clinical interventions. Many mental health experts believe that following the rules of EBM is the best way of safeguarding patients from unproven fads or dangerous interventions. If something is effective or ineffective, EBM will tell us.

But it turns out that ensuring medical practice is based on solid evidence is not as straightforward as it sounds. After all, evidence does not emerge from thin air. There are finite resources for research, which means that there is always someone deciding what topics should be researched, whose studies merit funding, and which results will be published. These kinds of decisions are not neutral. They reflect the beliefs and values of policymakers, funders, researchers, and journal editors about what is important. And determining what is important depends on one’s goals: improving clinical practice to be sure, but also reaping profits, promoting one’s preferred hypotheses, and advancing one’s career. In other words, what counts as evidence is partly determined by values and interests.

Teenage Girl Visits Doctor’s Office Suffering With Depression via iStock. ©monkeybusinessimages.

Teenage Girl Visits Doctor’s Office Suffering With Depression via iStock. ©monkeybusinessimages. Let’s take a concrete example from psychiatry. The two most common types of psychiatric interventions are medications and psychotherapy. As in all areas of medicine, manufacturers of psychiatric drugs play a very significant role in the funding of clinical research, more significant in dollar amount than government funding bodies. Pharmaceutical companies develop drugs in order to sell them and make profits and they want to do so in such a manner that maximizes revenue. Research into drug treatments has a natural sponsor — the companies who stand to profit from their sales. Meanwhile, psychotherapy has no such natural sponsor. There are researchers who are interested in psychotherapy and do obtain funding in order to study it. However, the body of research data supporting the use of pharmaceuticals is simply much larger and continues to grow faster than the body of data concerning psychotherapy. If one were to prioritize treatments that were evidence-based, one would have no choice but to privilege medications. In this way the values of the marketplace become incorporated into research, into evidence, and eventually into clinical practice.

The idea that values effect what counts as evidence is a particularly challenging problem for psychiatry because it has always suffered from the criticism that it is not sufficiently scientific. A broken leg is a fact, but whether someone is normal or abnormal is seen as a value judgement. There is a hope amongst proponents of evidence-based psychiatry that EBM can take this subjective component out of psychiatry but it cannot. Showing that a drug, like an antidepressant, can make a person feel less sad does not take away the judgement that there is something wrong with being sad in the first place. The thorniest ethical problems in psychiatry surround clinical cases in which psychiatrists and/or families want to impose treatment on mentally ill persons in hopes of achieving a certain mental state that the patient himself does not want. At the heart of this dispute is whose version of a good life ought to prevail. Evidence doesn’t resolve this debate. Even worse, it might end up hiding it. After all, evidence that a treatment works for certain symptoms — like hallucinations — focuses our attention on getting rid of those symptoms rather than helping people in other ways such as finding ways to learn to live with them.

The original authors of EBM worried that clinicians’ values and their exercise of judgment in clinical decision-making actually led to bad decisions and harmed patients. They wanted to get rid of judgment and values as much as possible and let scientific data guide practice instead. But this is not possible. No research is done without values, no data becomes evidence without judgments. The challenge for psychiatry is to be as open as possible about how values are intertwined with evidence. Frank discussion of the many ethical, cultural, and economic factors that inform psychiatry enriches rather than diminishes the field.

Heading image: Lexapro pills by Tom Varco. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The truth about evidence appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAddressing the true enemies of humankindThe victory of “misgender” – why it’s not a bad wordThe crossroads of sports concussions and aging

Related StoriesAddressing the true enemies of humankindThe victory of “misgender” – why it’s not a bad wordThe crossroads of sports concussions and aging

The vision of Confucius

To understand China, it is essential to understand Confucianism. There are many teachings of Confucianist tradition, but before we can truly understand them, it is important to look at the vision Confucius himself had. In this excerpt below from Confucianism: A Very Short Introduction, Daniel K. Gardner discusses the future the teacher behind the ideas imagined.

Confucius imagined a future where social harmony and sage rulership would once again prevail. It was a vision of the future that looked heavily to the past. Convinced that a golden age had been fully realized in China’s known history, Confucius thought it necessary to turn to that history, to the political institutions, the social relations, the ideals of personal cultivation that he believed prevailed in the early Zhou period, in order to piece together a vision to serve for all times. Here a comparison with Plato, who lived a few decades after the death of Confucius, is instructive. Like Confucius, Plato was eager to improve on contemporary political and social life. But unlike Confucius, he did not believe that the past offered up a normative model for the present. In constructing his ideal society in the Republic, Plato resorted much less to reconstruction of the past than to philosophical reflection and intellectual dialogue with others.

This is not to say, of course, that Confucius did not engage in philosophical reflection and dialogue with others. But it was the past, and learning from it, that especially consumed him. This learning took the form of studying received texts, especially the Book of Odes and the Book of History. He explains to his disciples:

“The Odes can be a source of inspiration and a basis for evaluation; they can help you to get on with others and to give proper expression to grievances. In the home, they teach you about how to serve your father, and in public life they teach you about how to serve your lord”.

The frequent references to verses from the Odes and to stories and legends from the History indicate Confucius’s deep admiration for these texts in particular and the values, the ritual practices, the legends, and the institutions recorded in them.

But books were not the sole source of Confucius’s knowledge about the past. The oral tradition was a source of instructive ancient lore for him as well. Myths and stories about the legendary sage kings Yao, Shun, and Yu; about Kings Wen and Wu and the Duke of Zhou, who founded the Zhou and inaugurated an age of extraordinary social and political harmony; and about famous or infamous rulers and officials like Bo Yi, Duke Huan of Qi, Guan Zhong, and Liuxia Hui—all mentioned by Confucius in the Analects—would have supplemented what he learned from texts and served to provide a fuller picture of the past.

“Ma Lin – Emperor Yao” by Ma Lin – National Palace Museum, Taipei. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Ma Lin – Emperor Yao” by Ma Lin – National Palace Museum, Taipei. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Still another source of knowledge for Confucius, interestingly, was the behavior of his contemporaries. In observing them, he would select out for praise those manners and practices that struck him as consistent with the cultural norms of the early Zhou and for condemnation those that in his view were contributing to the Zhou decline. The Analects shows him railing against clever speech, glibness, ingratiating appearances, affectation of respect, servility to authority, courage unaccompanied by a sense of right, and single-minded pursuit of worldly success—behavior he found prevalent among contemporaries and that he identified with the moral deterioration of the Zhou. To reverse such deterioration, people had to learn again to be genuinely respectful in dealing with others, slow in speech and quick in action, trustworthy and true to their word, openly but gently critical of friends, families, and rulers who strayed from the proper path, free of resentment when poor, free of arrogance when rich, and faithful to the sacred three-year mourning period for parents, which to Confucius’s great chagrin, had fallen into disuse. In sum, they had to relearn the ritual behavior that had created the harmonious society of the early Zhou.

That Confucius’s characterization of the period as a golden age may have been an idealization is irrelevant. Continuity with a “golden age” lent his vision greater authority and legitimacy, and such continuity validated the rites and practices he advocated. This desire for historical authority and legitimacy—during a period of disrupture and chaos—may help to explain Confucius’s eagerness to present himself as a mere transmitter, a lover of the ancients. Indeed, the Master’s insistence on mere transmission notwithstanding, there can be little doubt that from his study and reconstruction of the early Zhou period he forged an innovative—and enduring—sociopolitical vision. Still, in his presentation of himself as reliant on the past, nothing but a transmitter of what had been, Confucius established what would become something of a cultural template in China. Grand innovation that broke entirely with the past was not much prized in the pre-modern Chinese tradition. A Jackson Pollock who consciously and proudly rejected artistic precedent, for example, would not be acclaimed the creative genius in China that he was in the West. Great writers, great thinkers, and great artists were considered great precisely because they had mastered the tradition—the best ideas and techniques of the past. They learned to be great by linking themselves to past greats and by fully absorbing their styles and techniques. Of course, mere imitation was hardly sufficient; imitation could never be slavish. One had to add something creative, something entirely of one’s own, to mastery of the past.

Thus when you go into a museum gallery to view pre-modern Chinese landscapes, one hanging next to another, they appear at first blush to be quite similar. With closer inspection, however, you find that this artist developed a new sort of brush stroke, and that one a new use of ink-wash, and this one a new style of depicting trees and their vegetation. Now that your eye is becoming trained, more sensitive, it sees the subtle differences in the landscape paintings, with their range of masterful techniques an expression. But even as it sees the differences, it recognizes that the paintings evolved out of a common landscape tradition, in which artists built consciously on the achievements of past masters.

Featured image credit: “Altar of Confucius (7360546688)” by Francisco Anzola – Altar of Confucius. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The vision of Confucius appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesQuestioning the question: religion and rationalityThe ubiquity of structureThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?

Related StoriesQuestioning the question: religion and rationalityThe ubiquity of structureThe Scottish referendum: where is Cicero?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers