Oxford University Press's Blog, page 760

September 22, 2014

The impact of law on families

Strong, stable relationships are essential for both individuals and societies to flourish, but, from transportation policy to the criminal justice system, and from divorce rules to the child welfare system, the legal system makes it harder for parents to provide children with these kinds of relationships.

In her book Failure to Flourish: How Law Undermines Family Relationships, Clare Huntington argues that the legal regulation of families stands fundamentally at odds with the needs of families. We interviewed Professor Huntington about the connection between families and inequality. In the clips below, she explains policies and misconceptions that prevent us from helping families during the crucial first years of a child’s life, provides examples of supportive family law and good neighborhood development, and describes how helping families plays a role in fighting poverty.

Family law and how it affects families

Politics and policy in family law

The role of families in fighting poverty

How do you get into family law?

Headline image credit: family traffic sign. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The impact of law on families appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Responsibility to Protect in the Ebola outbreakAn interview with Shadi HamidPeace treaties that changed the world

Related StoriesThe Responsibility to Protect in the Ebola outbreakAn interview with Shadi HamidPeace treaties that changed the world

The Responsibility to Protect in the Ebola outbreak

When the UN General Assembly endorsed the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) in 2005, the members of the United Nations recognized the responsibility of states to protect the basic human and humanitarian rights of the world’s citizens. In fact, R2P articulates concentric circles of responsibility, starting with the individual state’s obligation to ensure the well-being of its own people; nested within the collective responsibility of the community of nations to assist individual states in meeting those obligations; in turn encircled by the responsibility of the United Nations to respond if necessary to ensure the basic rights of civilians, with military means only contemplated as a last resort, and only with the consent of the Security Council.

The Responsibility to Protect is a response to war crimes, genocide, and other crimes against humanity. But R2P is also a response to pattern and practice human rights abuses that include entrenched poverty, widespread hunger and malnutrition, and endemic disease and denials of basic health care — all socio-economic conditions which themselves feed and exacerbate armed conflict. In fact, socio-economic development is a powerful mechanism for guaranteeing the full panoply of human rights, just as the Millennium Development Goals are a means of fulfilling the Responsibility to Protect.

While Responsibility to Protect is often misconstrued as a mandate for military action, it is more intrinsically a call to social action, and the embodiment of the joint and several responsibilities of the community of nations to seek a coordinated global response to life-threatening conditions of armed conflict, repression, and socio-economic misery. While diplomats and public servants debate the legality and prudence of military responses to criminal uses of military force against civilians, we must not neglect the legality, prudence, and urgency of non-military responses to public health and poverty emergencies throughout the world.

The United States has put out a call to like-minded nations to join forces, literally and figuratively, in the degradation and destruction of the criminal militancy of the so-called Islamic State [ISIL or ISIL]. Despite concerns that the 2003-2011 US war in Iraq itself may have led to the inception and flourishing of ISIS, and despite warnings that the training, arming, and assisting of Iraqi forces, Shia militias in Iraq and non-ISIS Sunni militants in Syria may inflame sectarian violence and threaten civilians in both countries, the United States is contemplating another open-ended military intervention in the Levant.

A military intervention against ISIS is not justified by the principles of Responsibility to Protect. Without the authorization of the Security Council or the consent of the Syrian government, military intervention is unlawful in Syria, offending both the UN Charter and the tenets of R2P. In either Syria or Iraq a military intervention, even with the permission of the responsible governments, is unlawful if it is likely to lead to further outrages against civilians. Military action that predictably causes the suffering of civilians disproportionate to any legitimate military objectives violates the principles of humanitarian law and the Geneva Conventions, as well as the UN Charter and R2P.

UNICEF and partners visit the crowded Marché Niger to continue explaining to families how to they can protect themselves from Ebola. UNICEF have visited many markets, churches, mosques, schools, and community centers throughout Conakry and in the Forest region where the outbreak began. CC BY-NC 2.0 via UNICEF Guinea Flickr.

UNICEF and partners visit the crowded Marché Niger to continue explaining to families how to they can protect themselves from Ebola. UNICEF have visited many markets, churches, mosques, schools, and community centers throughout Conakry and in the Forest region where the outbreak began. CC BY-NC 2.0 via UNICEF Guinea Flickr.Alongside the criminal militancy of ISIS we face the existential threat of the Ebola virus in West Africa, endangering the people of Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and their neighbors. Over the past two months, approximately 5000 people have been infected by this hemorrhagic disease, and around 2500 have died, over 150 of them health care workers. At current rates of infection, with new cases doubling every three weeks, the virus could sicken 10,000 by the end of September, 40,000 by mid-November, and 120,000 by the New Year.

Ebola can be contained through basic public health responses: quarantining of the sick, tracing of exposure in families and communities, safe recovery of the bodies of the deceased, regular hand-washing and sanitation, and the all-important rebuilding of trust between effected community members, health care workers, and government officials. But the very countries impacted have fragile health care systems, insufficient hospital beds, and dedicated Red Cross workers, doctors, and nurses nearly besieged by the number of sick people needing care. By funding and supporting more health care and humanitarian relief workers at the international and local levels, more Ebola field hospitals and clinics, and more food, rehydration fluids, and safe blood supplies for transfusions, less new people will fall sick, and more of the infected will be treated and cured. At the same time, the fragile economies and political systems of the effected countries will be strengthened and the threat of regional insecurity will be addressed. Ebola in West Africa is calling out for a coordinated global public health intervention, which will serve our Responsibility to Protect at the local level, while furthering our collective security at the global level.

As the US Congress debates the funding of so-called moderate rebels in Syria in the pursuit of containing the criminal militancy of ISIS, we should turn our national attention to funding Ebola emergency relief in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Such action is consistent with our enlightened self-interest, and required by our humanitarian principles and obligations.

The post The Responsibility to Protect in the Ebola outbreak appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAn interview with Shadi HamidPeace treaties that changed the worldUnderstanding Immigration Detention

Related StoriesAn interview with Shadi HamidPeace treaties that changed the worldUnderstanding Immigration Detention

Learning with body participation through motion-sensing technologies

Have you ever thought that your body movements can be transformed into learning stimuli and help to deal with abstract concepts? Subjects in natural science contain plenty of abstract concepts which are difficult to understand through reading-based materials, in particular for younger learners who are at the stage of developing their cognitive ability. For example, elementary school students would find it hard to distinguish the differences in similar concepts of fundamental optics such as concave lens imaging versus convex lens imaging. By performing a simulated exercise in person, learners can comprehend concepts easily because of the content-related actions involved during the process of learning natural science.

As far as commonly adopted virtual simulations of natural science experiments are concerned, the learning approach with keyboard and mouse lacks a comprehensive design. To make the learning design more comprehensive, we suggested that learners be provided with a holistic learning context based on embodied cognition, which views mental simulations in the brain, bodily states, environment, and situated actions as integral parts of cognition. In light of recent development in learning technologies, motion-sensing devices have the potential to be incorporated into a learning-by-doing activity for enhancing the learning of abstract concepts.

When younger learners study natural science, their body movements with external perceptions can positively contribute to knowledge construction during the period of performing simulated exercises. The way of using keyboard/mouse for simulated exercises is capable of conveying procedural information to learners. However, it only reproduces physical experimental procedures on a computer. For example, when younger learners use conventional controllers to perform fundamental optics simulation exercises, they might not benefit from such controller-based interaction due to the routine-like operations. If environmental factors, namely bodily states and situated actions, were well-designed as external information, the additional input can further help learners to better grasp the concepts through meaningful and educational body participation.

Photo by Nian-Shing Chen. Used with permission.

Photo by Nian-Shing Chen. Used with permission.Based on the aforementioned idea, we designed an embodiment-based learning strategy to help younger learners perform optics simulation exercises and learn fundamental optics better. With this learning strategy enabled by the motion-sensing technologies, younger learners can interact with digital learning content directly through their gestures. Instead of routine-like operations, the gestures are designed as content-related actions for performing optics simulation exercises. Younger learners can then construct fundamental optics knowledge in a holistic learning context.

One of the learning goals is to acquire knowledge. Therefore, we created a quasi-experiment to evaluate the embodiment-based learning strategy by comparing the leaning performance of the embodiment-based learning group with that of the keyboard-mouse learning group. The result shows that the embodiment-based learning group significantly outperformed the keyboard-mouse learning group. Further analysis shows that no significant difference of cognitive load was found between these two groups although applying new technologies in learning could increase the consumption of learners’ cognitive resources. As it turned out, the embodiment-based learning strategy is an effective learning design to help younger learners comprehend abstract concepts of fundamental optics.

For natural science learning, the learning content and the process of physically experimenting are both important for learners’ cognition and thinking. The operational process conveys implicit knowledge regarding how something works to learners. In the experiments of lens imaging, the position of virtual light source and the type of virtual lens can help learners determine the attributes of the virtual image. By synchronizing gestures with virtual light source, a learner not only concentrates on the simulated experimental process but realizes the details of the external perception. Accordingly, learners can further understand how movements of the virtual light source and the types of virtual lens change the virtual image and learn the knowledge of fundamental optics better.

Our body movements have the potential to improve our learning if adequate learning strategies and designs are applied. Although motion-sensing technologies are now available to the general public, massive applications will depend on economical price and evidence-based approaches recommended for the educational purposes. The embodiment-based design has launched a new direction and is hoped to continuously shed light on improving our future learning.

The post Learning with body participation through motion-sensing technologies appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCatching up with Gemma Barratt, Marketing ManagerSo Long, FarewellWorld Water Monitoring Day 2014

Related StoriesCatching up with Gemma Barratt, Marketing ManagerSo Long, FarewellWorld Water Monitoring Day 2014

September 21, 2014

Why you should never trust a pro

A few years ago a friend of mine and I were intent on learning German. We were both taking an adult beginning German class together and were trying to make sense of what the teacher was telling us. As time progressed I began to use CDs in my car to practice the language everyday. I could repeat a lot of the phrases and slowly built up my ability to speak.

From 2007-2009, I had the good fortune of spending three summers in Berlin doing research thanks to a fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Over time I was able to speak more and more German and my approach of spending lots of time listening and speaking was paying great dividends. My friend, whose wife was from Germany, also spent a significant amount of time in Germany every summer. A few years later, I was finally able to carry out a conversation with his wife in German. But my friend was still struggling. He was slow to pick up words and although working hard seemed to lag behind.

A similar thing has happened to me in another domain. I am a recreational tennis player and enjoy learning more about the game and about how to improve. Recently, I received an email invitation to improve my doubles game. I don’t play doubles a lot but I went a long anyway. I entered my selection by indicating that I had trouble poaching. This is when someone crosses to the other side of the court while at the net and intercepts a ball to end the point quickly. After I entered my response I received my own personalized video tip. Basically, the Bryan Brothers, the most successful doubles team of all time, suggested that I see the ball before it was there. There was no time to react to the ball. So I needed to simply imagine where the ball would be and move to hit the imaginary ball before it was in that place. The video ends by saying that I heard it from the most successful doubles players on the planet. Who could be better at teaching me to poach well?

Suffice it to say that it was not that simple. Sometimes I would imagine where the ball was going and I could get to it. But other times I would miss the ball completely because it did not go where I expected it to go. Like my German-learning friend I seemed to be lagging behind the Bryan Brothers in my poaching ability.

Chess. CC0 via Pixabay.

Chess. CC0 via Pixabay.The differences between experts and novices has been the topic of discussion for many years. Adriaan de Groot, was the first to test this in the realm of chess. He found that chess experts outperformed less skilled players on tests of memory in real game situations. Follow-up work found that experts also showed different patterns of eye movements. K. Anders Ericsson has extended this seminal work by understanding the factors that play a role in the development of expertise. He has established that it takes roughly 10,000 hours to become an expert. But it is not simple exposure that plays a role. Experts engage in deliberate practice during which they are given feedback about their performance. This feedback helps experts fine-tune their skills over time so that they become automatic.

The role of deliberate practice can explain to some extent the differences between the Bryan Brothers and me. During their childhood, the Bryan Brothers, spent thousands of hours playing with tennis balls. Their father, Wayne Bryan, is a tennis coach and played tennis games with his sons at a very young age. As they grew older, they played doubles together. They probably missed hundreds of balls and made many errors. Now in their 30s the Bryan Brothers are able to literally see the ball before someone hits it. Like the chess experts tested by de Groot, they can anticipate what is going to happen because of a large database of experience.

A similar situation exists for my friend and I. When he asked me what he could to improve his language skills, I suggested that he listen to German CDs and just develop his ear for it over time. Eventually, he would learn to anticipate what was coming because of his experience of hearing many sentences.

Suffice it to say that my suggestion did not work so well. The problem was that I had not anticipated the difference between us. Like the Bryan Brothers, I grew up with two parents that had extensive experience with language and language learning. My mother taught English as a foreign language for 30 years in the public school system, has an M.A. in comparative literature, and has written poetry and prose in Spanish and English. My father was a professor of Spanish and Portuguese, learned Arabic in graduate school, and would listen to the Portuguese hour for fun on the radio. As a child I was exposed to five different languages to varying degrees, eventually gaining proficiency in two. At the age of 20 I lived in Brazil during which I gained extensive experience in a third language as an adult.

What I had neglected to account for was all the hours I had spent learning languages in some form. Like the Bryan Brothers I took for granted how much this experience had sharpened my learning abilities. Practicing with a CD in my car had a very different effect on me than it had on my friend.

So the next time a “pro” promises to teach their secrets over the internet in a few weeks, run in the other direction. There is no substitute for the number of hours required to gain expertise in a skill or ability. It doesn’t mean that learning cannot happen over time. But it requires patience and time that a “pro” often neglects to mention.

Headline image credit: Tennis ball. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Why you should never trust a pro appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe problem with moral knowledgeLife’s uncertain voyage10 ways to survive being a psychology student

Related StoriesThe problem with moral knowledgeLife’s uncertain voyage10 ways to survive being a psychology student

An interview with Shadi Hamid

With turmoil in the Middle East, from Egypt’s changing government to the emergence of the Isalmic State, we recently sat down with Shadi Hamid, author of Temptations of Power: Islamists and Illiberal Democracy in a New Middle East, to discuss about his research before and during the Arab Spring, working with Islamists across the Middle East, and his thoughts on the future of the region.

In your recent New York Times essay “The Brotherhood Will Be Back,” you argue that there is still support for the mixing of religion and politics, despite the Muslim Brotherhood’s recent failure in power. So do you see a way for Egypt to achieve stability in the years ahead? Can they look toward their neighbors (Jordan, Tunisia?) for a positive example?

Cultural attitudes toward religion do not change overnight, particularly when they’ve been entrenched for decades. Even if a growing number of Egyptians are disillusioned with the way Islam is “used” for political gain, this does not necessarily translated into support for “secularism,” a word which is still anathema in Egyptian public discourse. One of my book’s arguments I is that democratization not only pushes Islamists toward greater conservatism but that it also skews the entire political spectrum rightwards.

In Chapter 3, for instance, I look at the Arab world’s “forgotten decade,” when there were several intriguing but ultimately short-lived democratic experiments. Here, the ostensibly secular Wafd party, sensing the shift in the country toward greater piety, opted to Islamize its political program, something which was all too obvious (perhaps even a bit too obvious) in its 1984 program. It devoted an entire section to the application of Islamic law, in which the Wafd stated that Islam was both “religion and state.” The program also called for combating moral “deviation” in society and purifying the media of anything contradicting the sharia and general morals. The Wafd party also supported the supposedly secular regime of Anwar Sadat’s ambitious effort in the late 1970s and early 1980s to reconcile Egyptian law with Islamic law. Led by speaker of parliament and close Sadat confidant Sufi Abu Talib, the initiative wasn’t just mere rhetoric; Abu Talib’s committees painstakingly produced hundreds of pages of detailed legislation, covering civil transactions, tort reform, criminal punishments, as well as the maritime code.

The point here is that the Islamization of society (itself pushed ahead by Islamists) doesn’t just affect Islamists. Even Egypt’s president, former general Abdel Fattah al-Sissi, cannot escape these deeply embedded social realities.

Egypt is de-democratizing right now, but the Sissi regime, unlike Mubarak’s, is a popular autocracy where the brutal suppression of one particular group — the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamists — is cheered on by millions of Egyptians. Sissi, then, is not immune from mass sentiment. A populist in the classic vein, Sissi seems to understand this and, like the Brotherhood, instrumentalizes religion for partisan ends. In many ways, Sissi’s efforts surpass those of Islamists before him, asserting great control over al-Azhar, the premier seat of Sunni scholarship in the region, and using the clerical establishment to shore up his regime’s legitimacy. Sissi has said that it’s the president’s role to promote a “correct understanding” of Islam. His regime has also been politically ostentatious with religion in its crackdown against the Gay community, leading one observer to note that

Religion is a powerful tool in a deeply religious society and Sissi, whatever his personal inclinations, can’t escape that basic fact, particularly with a mobilized citizenry.

Looking at the region more broadly, there are really no successful models of reconciling democracy with Islamism, at least not yet, and this failure is likely to have long-term consequences on the region’s trajectory. Turkish Islamists had to effectively concede who they were and become something else — “conservative democrats” — in order to be fully incorporated in Turkish politics. In Tunisia, the Islamist Ennahda party, threatened with Egypt-style mass protests and with the secular opposition calling for the dissolution of parliament and government, opted to step down from power. The true test for Tunisia, then, is still to come: what happens if Ennahda wins the next scheduled elections, and the elections after that, and feels the need to be more responsive to its conservative base? Will this lead, again, to a breakdown in political order, with secular parties unwilling to live with greater “Islamization”?

You began your research on Islamist movements before the start of the Arab Spring. How did your project change after the unrest in 2011? What book did you think you would write when you began living in the region — and what did it become after the revolutions?

I began my research on Islamist movements in 2004-5, when I was living in Jordan as a Fulbright fellow. These were movements that displayed an ambivalence toward power, to the extent that they even lost elections on purpose (an odd phenomenon that was particularly evident in Jordan). Power, and its responsibilities, were dangerous. After the Islamic Salvation Front dominated the first round of the 1991 Algerian elections, and with the military preparing to intervene, the Algerian Islamist Abdelkader Hachani warned a crowd of supporters: “Victory is more dangerous than defeat.” In a sense, then, I was lucky to be able to expand the book’s scope to cover the tumultuous events of 2011-3, allowing me to explore evolving, and increasingly contradictory, attitudes toward power. Because if power was dangerous, it was also tempting, and so this became a recurring theme in the book: the potentially corrupting effects of political power, a problem which was particularly pronounced with groups that claimed a kind of religious purity that transcended politics. The book became about these two phases in the Islamist narrative, in opposition and under repression, on one hand, and during democratic openings, on the other. And then, of course, back again. I knew the military coup of 3 July 2013 and then the Rabaa massacre of 14 August — a dark, tragic blot on Egypt’s history — provided the appropriate bookend. The Brotherhood had returned to its original, purer state of opposition.

The Arab Spring also provided an opportunity to think more seriously and carefully about the effects of democratization. Would democratization have a moderating effect on mainstream Islamist movements, as the academic and conventional wisdom would suggest? Or was there a darker undercurrent, with democratization unleashing ideological polarization and pushing Islamists further to the right? I wanted to challenge a kind of cultural essentialism in reverse: that Islamists, like its ideological counterparts in Latin America or Western Europe, would be no match for “liberal democracy,” history’s apparent end state. Any kind of determinism, even the liberal variety, would prove problematic, especially for us as Americans with our tendency to believe that the process of history would overwhelm the whims of ideology. In a way, I wanted to believe it too, and for many years I did. As someone who has long been a proponent of supporting democracy in the Middle East, this puts me in a bit of a bind: In the Middle East, democracy is simply less attractive. Yes. And now, since the book has come out, I’ve been challenged along these very lines: “Maybe democracy isn’t so good after all… Maybe the dictators were right.” Well, in a sense, they were right. But this is only a problem if we conceive of democracy as some sort of panacea or short-term fix. Democracy is supposed to be difficult, and this is perhaps where the comparisons to the third-wave democracies of the 1980s and 1990s were misleading. The divides of Arab countries were “foundational,” meaning that they weren’t primarily “policy” problems; they were the more basic problems of the State, its meaning, its purpose, and, of course, the role of religion in public life, which inevitably brings us back to the identity of the State. What kind of conception of the Good should the Egyptian or Tunisian states be promoting? Should the state be neutral or should it be a state with a moral or religious mission? These are raw, existential divides that hearken back more to 1848 than 1989.

Tahrir Square on 11 February 2011, by Jonathan Rashad CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Tahrir Square on 11 February 2011, by Jonathan Rashad CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.You conducted many interviews to research Temptations of Power. How did the interviews craft your argument — whether you were speaking with political leaders, activists, students, or citizens? Feel free to mention some examples.

Spending so much time with Islamist activists and leaders over the course of a decade, some of whom I got to know quite well, was absolutely critical. And this book — and pretty much every thing I know and think about Islamist movements — has been informed and shaped by those discussions. I guess I’m a bit old-fashioned that way; that to understand Islamists, you have to sit with them, talk to them, and get to know them as individuals with their own fears and aspirations. This is where I think it’s important for scholars of political Islam to cordon off their own beliefs and political commitments. Just because I’m an American and a small-l liberal (and those two, in my case, are intertwined), doesn’t mean that Egyptians or Jordanians should be subject to my ideological preferences. If you go into the study of Islamism trying to compare Islamists to some liberal ideal, then that’s distorting. Islamists, after all, are products of their own political context, and not ours. So that’s the first thing.

Second, as a political scientist, my tendency has always been to put the focus on political structures, and the first half of my book does quite a bit of that. In other words, context takes precedence: that Islamists — or, for that matter, Islam — are best understood as products of various political variables. This is true, but only up to a point and I worry that we as academics have gone too much in this direction, perhaps over-correcting for what, decades ago, was a seeming obsession with belief and doctrine.

When religion is less relevant in our own lives, it can be difficult to make that jump, to not just understand — but to relate — to its meaning and power for believers, and for those, in particular, who believe they have a cause beyond this life. But I think that outsiders have to make an extra effort to close that gap. And that, in some ways, is the most challenging, and ultimately rewarding, aspect of my work: to be exposed to something fundamentally different. I think, at this point, I feel like I have a good grasp on how mainstream Islamists see the world around them. What I still struggle with is the willingness to die. If I was at a sit-in and the army was coming in with live fire, I’d run for the hills. And that’s why my time interviewing Brotherhood members in Rabaa — before the worst massacre in modern Egyptian history — was so fascinating and forced me to at least try and transcend my own limitations as an analyst. Gehad al-Haddad — who had given up a successful business career in England to return to Egypt — told me was “very much at peace.” He was ready to die, and I knew that he, and so many others, weren’t just saying it. Because many of them — more than 600 — did, in fact, die.

Where does this willingness to die come from? I found myself pondering this same question just a few weeks ago when I was in London. One Brotherhood activist, now unable to return to Egypt, relayed the story of a protester standing at the front line, when the military moved in to “disperse” the sit-in. A bullet grazed his shoulder. Behind him, a man fell to the ground. He had been shot to death. He looked over and began to cry. He could have died a martyr. He knew the man behind him had gone to heaven, in God’s great glory. This is what he longed for. As I heard this story, it couldn’t have been any more clear: this wasn’t politics in any normal sense. Purity, absolution. This was the language of religion, the language of certainties. Where politics, in a sense, is about accepting, or at least coming to terms, with impossibility of purity.

Are you working on any new publications at the moment?

I’m hoping to build on the main arguments in my book and look more closely at how the inherent tensions between religion and mundane politics are expressed in various contexts. This, I think, is at least part of what makes Islamists so important to our understanding of the Middle East. Because their story is, in some ways, the story of a region that is breaking apart because of the inability to answer the fundamental questions of identity, religion, God, citizenship, and State-ness. One project will look at how various Islamist movements have responded to a defining moment in the Islamist narrative — the military coup of July 3, 2013, which has quickly replaced the Algerian coup of 1992 as the thing that always inevitably comes up when you talk to an Islamist. In some ways, I suspect it will prove even more defining in the long-run. Algeria, as devastating as it was, was still somehow remote (and, ironically enough, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Algerian offshoot allowed itself to be co-opted by the military government throughout most of Algeria’s “black decade”).

This time around, there are any number of lessons to be learned. One response among Islamists is that the Brotherhood should have been more confrontational, moving more aggressively against the “deep state” instead of seeking temporary accommodation. While others fault the Brotherhood for not being inclusive enough, and alienating the very allies who had helped bring it to power. But, of course, these two “lessons” are not mutually exclusive, with many believing that the Brotherhood — although it’s not entirely clear how exactly this would work in practice — should have been both more aggressive and more inclusive.

You recently went on a US tour to promote and discuss Temptations of Power — any recent discussion items, comments or questions which supported your conclusions or refined your thinking that you would like to share?

During the tour, I’ve really enjoyed the opportunity to discuss the more philosophical aspects of the book, including the “nature” of Islam, liberalism, and democracy. These are contested terms; Islam, for instance, can mean very different things to different people. A number of people would ask about Narendra Modi, India’s democratically-elected prime minister and somewhat notorious Hindu nationalist. Here’s someone who, in addition to being illiberal, was complicit in genocidal acts against the Muslim minority in Gujarat. But an overwhelming number of Indians voted for him in a free, democratic process. There’s something inspiring about accepting electoral outcomes that might very well be personally threatening to you. Another allied country, Israel, is a democracy with strong (and seemingly stronger) illiberal tendencies. Popular majorities

In some sense, the tensions between liberalism and democracy are universal and trying to find the right balance is an ongoing struggle (although it’s more pronounced and more difficult to address in the Middle Eastern context). So it makes little sense to expect a given Arab country to become anything resembling a liberal democracy in two or three years, when, even in our own history as Americans, our liberalism as well as our democracy were very much in doubt at any number of key points. (I just read this excellent Peter Beinart piece on our descent into populary-backed illiberalism during World War I. Cincinnati actually banned pretzels).

At the same time, looking at other cases has helped me better grasp what, exactly, makes the Middle East different. For example, as illiberal as Modi and the BJP might be, the ideological distance between them and the Congress Party isn’t as much as we might think. In part, this is because the Hindu tradition, to use Michael Cook’s framing, is simply less relevant to modern politics. As Cook writes, “Christians have no law to restore while Hindus do have one but show little interest in restoring it.” Islamists, on the other hand, do have a law and it’s a law that’s taken seriously by large majorities in much of the region. The distinctive nature of “law” — and its continued relevance — in today’s Middle East does add a layer of complexity to the problem of pluralism. This gets us into some uncomfortable territory but I think to ignore it would be a mistake. Islam is distinctive in how it relates to modern politics, at least relative to other major religions. This isn’t bad or good. It just is, and I think this is worth grappling with. As the region plunges into ever greater violence, with questions of religion at the fore, we will need to be more honest about this, even if it’s uncomfortable. This, sometimes, can be as simple as taking religion, and “Islam” in particular, more seriously in an age of secularism. I’m reminded of one of my favorite quotes, which I cite in the book, from the great historian of the Muslim Brotherhood, Richard Mitchell. The Islamic movement, he said, “would not be a serious movement worthy of our attention were it not, above all, an idea and a personal commitment honestly felt.”

Heading image: Protesters fests toward Pearl roundabout. By Bahrain in pictures, CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An interview with Shadi Hamid appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPeace treaties that changed the worldUnderstanding Immigration DetentionScots wha play: an English Shakespikedian Scottish independence referendum mashup

Related StoriesPeace treaties that changed the worldUnderstanding Immigration DetentionScots wha play: an English Shakespikedian Scottish independence referendum mashup

Peace treaties that changed the world

From their remotest origins, treaties have fulfilled numerous different functions. Their contents are as diverse as the substance of human contacts across borders themselves. From pre-classical Antiquity to the present, they have not only been used to govern relations between governments, but also to regulate the position of foreigners or to organise relations between citizens of different polities.

The backbones of the ‘classical law of nations’ or the jus publicum Europaeum of the late 17th and 18th centuries were the networks of bilateral treaties between the princes and republics of Europe, as well as the common principles, values, and customary rules of law that could be induced from the shared practices that were employed in diplomacy in general and in treaty-making in particular. Some treaties, particularly the sets of peace treaties that were made at multiparty peace conferences — such as those of Westphalia (1648, from 1 CTS 1), Nijmegen [Nimeguen] (1678/79, from 14 CTS 365), Rijswijk [Ryswick] (1697, from 21 CTS 347), Utrecht (1713, from 27 CTS 475), Aachen [Aix-la-Chapelle] (1748, 38 CTS 297) or Paris/Hubertusburg (1763, 42 CTS 279 and from 42 CTS 347) — gained special significance and were considered foundational to the general political and legal order of Europe.

This interactive map shows a selection of significant peace treaties that were signed from 1648 to 1919. All of the treaties mapped here include citations to their respective entries in the Consolidated Treaty Series, edited and annotated by Clive Parry (1917-1982). (Please note that this map is not intended to be an exhaustive representation of the most important peace treaties from this period.)

Headline image credit: Dove. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Peace treaties that changed the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUnderstanding Immigration DetentionWhat would an independent Scotland look like?Remembering the slave trade and its abolition

Related StoriesUnderstanding Immigration DetentionWhat would an independent Scotland look like?Remembering the slave trade and its abolition

The problem with moral knowledge

Traveling through Scotland, one is struck by the number of memorials devoted to those who lost their lives in World War I. Nearly every town seems to have at least one memorial listing the names of local boys and men killed in the Great War (St. Andrews, where I am spending the year, has more than one).

Scotland endured a disproportionate number of casualties in comparison with most other Allied nations as Scotland’s military history and the Scots’ reputation as particularly effective fighters contributed to both a proportionally greater number of Scottish recruits as well as a tendency for Allied commanders to give Scottish units the most dangerous combat assignments.

Many who served in World War I undoubtedly suffered from what some contemporary psychologists and psychiatrists have labeled ‘moral injury’, a psychological affliction that occurs when one acts in a way that runs contrary to one’s most deeply-held moral convictions. Journalist David Wood characterizes moral injury as ‘the pain that results from damage to a person’s moral foundation’ and declares that it is ‘the signature wound of [the current] generation of veterans.’

By definition, one cannot suffer from moral injury unless one has deeply-held moral convictions. At the same time that some psychologists have been studying moral injury and how best to treat those afflicted by it, other psychologists have been uncovering the cognitive mechanisms that are responsible for our moral convictions. Among the central findings of that research are that our emotions often influence our moral judgments in significant ways and that such judgments are often produced by quick, automatic, behind-the-scenes cognition to which we lack conscious access.

Thus, it is a familiar phenomenon of human moral life that we find ourselves simply feeling strongly that something is right or wrong without having consciously reasoned our way to a moral conclusion. The hidden nature of much of our moral cognition probably helps to explain the doubt on the part of some philosophers that there really is such a thing as moral knowledge at all.

Scottish National War Memorial, Edinburgh Castle. Photo by Nilfanion, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Scottish National War Memorial, Edinburgh Castle. Photo by Nilfanion, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In 1977, philosopher John Mackie famously pointed out that defenders of the reality of objective moral values were at a loss when it comes to explaining how human beings might acquire knowledge of such values. He declared that believers in objective values would be forced in the end to appeal to ‘a special sort of intuition’— an appeal that he bluntly characterized as ‘lame’. It turns out that ‘intuition’ is indeed a good label for the way many of our moral judgments are formed. In this way, it might appear that contemporary psychology vindicates Mackie’s skepticism and casts doubt on the existence of human moral knowledge.

Not so fast. In addition to discovering that non-conscious cognition has an important role to play in generating our moral beliefs, psychologists have discovered that such cognition also has an important role to play in generating a great many of our beliefs outside of the moral realm.

According to psychologist Daniel Kahneman, quick, automatic, non-conscious processing (which he has labeled ‘System 1′ processing) is both ubiquitous and an important source of knowledge of all kinds:

‘We marvel at the story of the firefighter who has a sudden urge to escape a burning house just before it collapses, because the firefighter knows the danger intuitively, ‘without knowing how he knows.’ However, we also do not know how we immediately know that a person we see as we enter a room is our friend Peter. … [T]he mystery of knowing without knowing … is the norm of mental life.’

This should provide some consolation for friends of moral knowledge. If the processes that produce our moral convictions are of roughly the same sort that enable us to recognize a friend’s face, detect anger in the first word of a telephone call (another of Kahneman’s examples), or distinguish grammatical and ungrammatical sentences, then maybe we shouldn’t be so suspicious of our moral convictions after all.

The good news is that hope for the reality of moral knowledge remains.

The good news is that hope for the reality of moral knowledge remains. – See more at: http://blog.oup.com/?p=75592&prev...

In all of these cases, we are often at a loss to explain how we know, yet it is clear enough that we know. Perhaps the same is true of moral knowledge.

Still, there is more work to be done here, by both psychologists and philosophers. Ironically, some propose a worry that runs in the opposite direction of Mackie’s: that uncovering the details of how the human moral sense works might provide support for skepticism about at least some of our moral convictions.

Psychologist and philosopher Joshua Greene puts the worry this way:

‘I view science as offering a ‘behind the scenes’ look at human morality. Just as a well-researched biography can, depending on what it reveals, boost or deflate one’s esteem for its subject, the scientific investigation of human morality can help us to understand human moral nature, and in so doing change our opinion of it. … Understanding where our moral instincts come from and how they work can … lead us to doubt that our moral convictions stem from perceptions of moral truth rather than projections of moral attitudes.’

The challenge advanced by Greene and others should motivate philosophers who believe in moral knowledge to pay attention to findings in empirical moral psychology. The good news is that hope for the reality of moral knowledge remains.

And if there is moral knowledge, there can be increased moral wisdom and progress, which in turn makes room for hope that someday we can solve the problem of war-related moral injury not by finding an effective way of treating it but rather by finding a way of avoiding the tragedy of war altogether. Reflection on ‘the war to end war’ may yet enable it to live up to its name.

The post The problem with moral knowledge appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘This is my word’: Jesus, the Eucharist, and the BibleWhat commuters know about knowing10 ways to survive being a psychology student

Related Stories‘This is my word’: Jesus, the Eucharist, and the BibleWhat commuters know about knowing10 ways to survive being a psychology student

September 20, 2014

A visual history of the Roosevelts

The Roosevelts: Two exceptionally influential Presidents of the United States, 5th cousins from two different political parties, and key players in the United States’ involvement in both World Wars. Theodore Roosevelt negotiated an end to the Russo-Japanese War and won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize. He also campaigned for America’s immersion in the First World War. Almost 25 years later, Franklin Delano Roosevelt came into office during the calamitous aftermath of the Great Depression, yet during his 12-year presidency he contributed to the drop in unemployment rates from 24% when he first took office, to a staggering mere 2% when he left office in 1945. Furthermore, the first lady Eleanor Roosevelt encouraged discussion and implementation of women’s rights, World War II refugees, and civil rights of Asian and African Americans even well-after her husband’s presidency and death. Witness the lives of these illustrious figures through this slideshow, and take a look at the first half of 20th century American history through the lives of the Roosevelts.

Theodore Roosevelt

“[Theodore] Roosevelt used his bully pulpit to shape public opinion on many subjects. Conservation of natural resources received special emphasis…. Earlier presidents had done little to protect scenic places and national parks against the wasteful exploitation of the environment…. The president achieved much, creating five national parks, four national game preserves, fifty-one bird reservations, and one hundred and fifty national forests” (Lewis L. Gould, Theodore Roosevelt, 43). Public domain via the Library of Congress

Theodore Roosevelt

In 1909 and 1910, after finishing his second term as president, Roosevelt traveled to Africa on safari. While abroad, the American public grew increasingly fascinated with Roosevelt and “to satisfy popular demand, [Theodore Roosevelt] recruited a friendly reporter, Warrington Dawson, to recount the progress of the hunt for the press corps. When Roosevelt returned first to Europe and then home in the spring of 1910, it was to intense popular acclaim everywhere.” (Lewis L. Gould, Theodore Roosevelt, 52). TR (center, facing sideways) on safari, 1910. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft

“Taft was a first-class lieutenant; but he is only fit to act under orders; and for three years and a half the orders given him have been wrong. Now he has lost his temper and is behaving like a blackguard.” (Theodore Roosevelt to Arthur Lee, dated May 1912, from the Papers of Lord Lee of Fareham.) After leaving office in 1908, Theodore Roosevelt’s relationship with his personally-selected successor, William Howard Taft, soured due to policy differences. Theodore Roosevelt decided to run for an unprecedented third term against President Taft in 1912 as a third-party candidate. Theodore Roosevelt and his newly-founded Progressive Party were ultimately defeated by Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson in the general election. Theodore Roosevelt and William H. Taft, c. 1909. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt with his mother, Sara

“Franklin grew up in a remarkably cosseted environment, insulated from the normal experiences of most American boys, both by his family’s wealth and by their intense and at times almost suffocating love…. It was a world of extraordinary comfort, security, and serenity, but also one of reticence and reserve.” (Alan Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 4). Franklin Delano Roosevelt with his mother, Sara, 1887. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

FDR at Harvard

“Entering Harvard College in 1900, [FDR] set out to make up for what he considered his social failures [as a boarding school student at] Groton. He worked hard at making friends, ran for class office, and became president of the school newspaper, the Harvard Crimson, a post that was more a social distinction at the time than a journalistic one. (His own contributions to the newspaper consisted largely of banal editorials calling for greater school spirit.)” (Alan Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 5). FDR as president of the Harvard Crimson, with its Senior Board in 1904. Public domain via the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library.

FDR and Polio

In August of 1921, Roosevelt fell ill after being exposed to the poliomyelitis virus. “He learned to disguise it for pulic purposes by wearing heavy leg braces; supporting himself, first with crutches and later with a cane and the arm of a companion; and using his hips to swing his inert legs forward…So effective was the deception that few Americans knew that Roosevelt could not walk” (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 18-19). Franklin D. Roosevelt, Fala and Ruthie Bie at Hill Top Cottage in Hyde Park, N.Y . Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library.

FDR and the Great Depression

Depression breadlines. In the absence of substantial Gov’t relief programs during 1932, free food was distributed with private funds in some urban centers to large numbers of the unemployed. February 1932 Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Photo 69146. Public domain.

FDR and the New Deal

“When Franklin Delano Roosevelt took the oath of office as president for the first time on March 4, 1933, every moving part in the machinery of the American economy had evidently broken…. Roosevelt right away began working to repair finance, agriculture, and manufacturing…. The Roosevelt agenda grew by experiment: the parts that worked stuck, no matter their origin. Indeed, the program got its name by just that process: Roosevelt used the phrase “new deal” when accepting the democratic nomination for president, and the press liked it. The “New Deal” said the Roosevelt offered a fresh start, but it promised nothing specific: it worked, so it stuck.” (Rauchway, The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction, 56). Franklin Roosevelt at desk in Oval Office with group, Washington, D.C. 1933. Library of Congress, Harris & Ewing Collection. Wikimedia Commons.

FDR and the New Deal

In the beginning of his presidency, Roosevelt proposed a “New Deal.” Over time, it “created state institutions that significantly and permanently expanded the role of federal government in American life, providing at least minimal assistance to the elderly, the poor, and the unemployed; protecting the rights of labor unions; stabilizing the banking system; building low-income housing; regulating financial markets; subsidizing agricultural production…As a result, American political and economic life became much more competitive, with workers, farmers, consumers, and others now able to press their demands upon the government in ways that in the past had usually been available only the corporate world” (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 61). “CCC boys at work–Prince George Co., Virginia.” Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum

FDR and the Social Security ct

President Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act, at approximately 3:30 pm EST on August 14th, 1935. Standing with Roosevelt are Rep. Robert Doughton (D-NC); Sen. Robert Wagner (D-NY); Rep. John Dingell (D-MI); Rep. Joshua Twing Brooks (D-PA); the Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins; Sen. Pat Harrison (D-MS); and Rep. David Lewis (D-MD). Library of Congress. Wikimedia Commons.

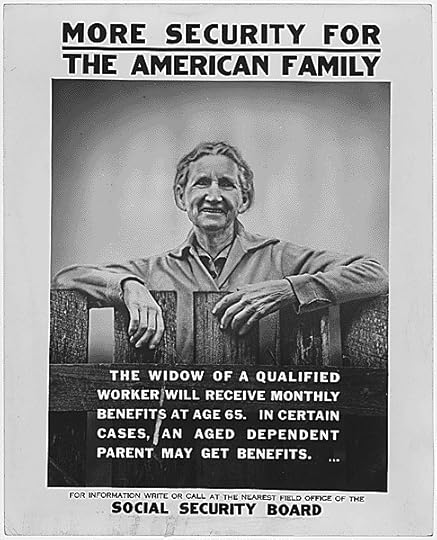

FDR and the Social Security Act

One of the most important pieces of social legislation in American History was The Social Security Act of 1935. The Act was part of Roosevelt’s Second New Deal (from 1935-38). The Social Security Act set up several important programs, including unemployment compensation (funded by employers) and old-age pensions (funded by a Social Security tax paid jointly by employers and employees). It also provided assistance to the disabled (primarily the blind) and the elderly poor (people presumably too old to work). Furthermore, it established Aid to Dependent Children (later called Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC), which created the model for what most Americans considered “welfare” for over sixty years (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 51-52). Roosevelt said, “No one can guarantee this country against the dangers of future depressions, but we can reduce those dangers” (Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, 270). This is a poster publicizing Social Security benefits. Public Domain via Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

FDR and the Second World War

When war finally broke out in Europe in September 1939, Roosevelt continued to insist that the conflict would not involve the United States. Roosevelt declared, “This nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well.” Then, on December 7th, 1941, a wave of Japanese bombers struck the American naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, killing more than 2,000 American servicemen and damaging or destroying dozens of ships and airplanes. Roosevelt called it, “a date which will live in infamy” (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 68). View looking up “Battleship Row” on 7 December 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The battleship USS Arizona (BB-39) is in the center, burning furiously. To the left of her are USS Tennessee (BB-43) and the sunken USS West Virginia (BB-48). Official U.S. Navy Photograph. Wikimedia Commons.

FDR and the declaration of war

“The Senate and House voted for a declaration of war—the Senate unanimously, and the House by a vote of 388 to 1. Three days later, Germany and Italy, Japan’s European allies, declared war on the United States, and the American Congress quickly and unanimously reciprocated” (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 75-76). United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt signing the declaration of war against Japan, in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor. US National Parks Service via Wikimedia Commons

The Big Three

Shown here are ‘The Big Three’: Stalin, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the Tehran Conference, November 1943. At this time, war in eastern Europe had turned decisively in favor of the Soviety Union, which meant that Roosevelt and Churchill now had little leverage over Stalin. Even so, Stalin agreed to enter the Pacific war after the fighting in Europe came to an end. Roosevelt and Churchill promised to launch the long-delayed invasion of France in the spring of 1944 (Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 83). US Signal Corps public domain photo.

Eleanor Roosevelt and the Second World War

An outspoken and publicly active First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt was active both on the homefront and overseas. Her visits drew crowds of people and welcomed her favorably and amiably. This resulted in positive press being written about the Roosevelts across the United States as well as Britain. Eleanor Roosevelt visiting troops in Galapagos Island. US National Archives and Records Administration

The Roosevelt Family

Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt with their 13 grandchildren in Washington, D.C. in January of 1945 (Archivist note: This photograph was taken at FDR’s fourth inauguration. This is one of the last family photographs taken before FDR’s death.) Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

FDR's death

Franklin Delano Roosevelt died of a stroke in on 12 April 1945. In the decades since his death, his stature as one of the most important leaders of the twentieth century has not diminished. “History will honor this man for many things, however wide the disagreement of many of his countrymen with some of his policies and actions,” the New York Times wrote the day after his death. “It will honor him above all else because he had the vision to see clearly the supreme crisis of our times and the courage to meet that crisis boldly. Men will thank God on their knees, a hundred years from now, that Franklin D. Roosevelt was in the White House” (The New York Times, 13 April 1945). Roosevelt’s funeral procession in Washington in 1945; watched by 300,000 spectators. Library of Congress.

Eleanor Roosevelt

The remaining 17 years that Eleanor Roosevelt lived after her husband passed away were years in which she carried out her humanitarian efforts and maintained the integrity of the Roosevelt name. The next President Harry Truman appointed Eleanor as a delegate to the United Nations General Assembly, and less than a year later, she became the first chairperson of the preliminary United Nations Commission on Human Rights. She also chaired the John F. Kennedy administration’s Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. To this day, she is quoted, and referred to with great respect and admiration for her efforts in human rights and politics. Roosevelt speaking at the United Nations in July 1947. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

Headline image credit: The Roosevelt Family. Library of Congress.

The post A visual history of the Roosevelts appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEight myths about Fair RosamundWhat commuters know about knowingThe Oxford DNB at 10: new research opportunities in the humanities

Related StoriesEight myths about Fair RosamundWhat commuters know about knowingThe Oxford DNB at 10: new research opportunities in the humanities

True or False: facts and myths on American higher education

American higher education is at a crossroads. The cost of a college education has made people question the benefits of receiving one. We asked Goldie Blumenstyk, author of American Higher Education in Crisis? What Everyone Needs to Know to help us separate fact from fiction.

True or False? It doesn’t pay to go to college.

False: Generally speaking, college is still worth the money in the long run. According to the latest figures from the College Board, the median earnings for a person with a bachelor’s degree was 65% greater than those for someone with just a high-school diploma over a 40-year working career. Those with associate degrees, typically earned in community or technical colleges, had earnings that were 27% higher. What’s more, the job market of the future will continue to offer more opportunities to those with post-secondary education. By 2020, experts predict two-thirds of jobs will require at least some education and training beyond the high school level. Forty years ago, only about 28% of jobs required that higher level of education.

It costs hundreds of thousands of dollars to go to college.

False: While there are colleges that charge upwards of $50,000 a year for tuition, room, and board (at least 175 of them, counting the half-dozen or so public universities that charge their out-of-state students that much) most colleges cost a lot less. Last year half of all four-year public-college students attended an institution where the annual in-state tuition rate was below $9,011. Some 85 percent of them attended a college where tuition charges were below $15,000. Private colleges charge more but with student aid from the federal and state governments and the colleges themselves, the price students actually pay is often substantially lower than the “sticker price.” Last year the average “net price” at a four-year private college was $12,460. And the average tuition at community colleges, where about four out of ten undergraduates now attend college, was about $3,300 a year.

Student debt is unmanageable.

True (and False): About 40 million Americans now carry student-loan debt and for many of them, particularly recent graduates struggling to get established in a tough job market, student-debt burdens are a real challenge. That’s evidenced by the rising rate of defaults on student loans. But according to the latest data from Project on Student Debt, for students graduating from college with debt, those who attended four-year public colleges had an average debt burden of $25,500. For comparison sake, a new Ford Focus automobile costs anywhere from about $17,000 to $35,000, depending on the options. The average debt level for graduates from four-year private colleges was $32,300. About 40% of student debt is for balances smaller than $10,000, according to the College Board.

Of all the factors that have propelled college prices up faster than the costs of most other goods and services over the past for 40 years, the cost of all those tenured professors isn’t one of them.

True: Actually, while college costs have been rising, the proportion of faculty members who are tenured professors, or on track to be considered for tenure, has shrunk precipitously during the same period. In the mid-1970s according to the American Association of University Professors, about 45% of all faculty members were tenured or on the tenure track; today only about one-quarter of them are. Full-time professors are well paid, but colleges now increasingly rely on faculty members who they hire annually, adjunct professors who they pay only about $2,700 per course, on average, and graduate teaching assistants. Meanwhile, factors that do seem to more directly drive up costs and prices include: growing numbers of administrators, new facilities, major reductions in state support, and the costs for student aid.

Online education takes place primarily at for-profit colleges like the University of Phoenix and DeVry University.

False: For-profit colleges like those were among the first to use distance education-technologies to expand their enrollments, but online education is now increasingly commonplace in more traditional public and private colleges. According to the latest available data, more than five million students — about a quarter of the student population — took at least one course that was fully or partly online in fall 2012. About half of them took a class that was exclusively online. The medium, however, still seems more popular for certain fields of study. For both graduate and undergraduate education, the most common courses and degrees offered via distance education are in business, marketing, computer- and information-technologies, and health-related fields. In the future, students can expect to see more and more classes that use distance-education technology in a hybrid format, mixing face-to-face instruction with online components.

Headline image credit: Graduation By Tulane Public Relations, CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post True or False: facts and myths on American higher education appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow threatened are we by Ebola virus?Limiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemicWhat is the Islamic state and its prospects?

Related StoriesHow threatened are we by Ebola virus?Limiting the possibility of a dangerous pandemicWhat is the Islamic state and its prospects?

September 19, 2014

So Long, Farewell

Dearest readers, I am sorry to say that the time has come for me to say goodbye. I have had a wonderful time meeting you all, not to mention learning more than I ever thought I would know about the fantastic field of oral history. However, grant applications and comprehensive examinations are calling my name, so I must take a step back from tweeting, Facebooking, tumbling and Google plusing (sure, why not).

Fear not, we have found another to take my place: the esteemable and often bow-tie-wearing Andrew Shaffer. I chatted with him earlier this week and I already think he’ll make a wonderful Caitlin 2.0. (For instance, Andrew originally wanted to introduce himself with the lyrics from the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air theme song. A+.)

* * * * *

So, Andrew, tell us a bit about yourself.

Well, Caitlin, I am a first year PhD student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, studying gender and sexuality history in a modern US context. I’m originally from Illinois, but lived in San Francisco for three years before coming to Madison. There I received an MA in International Studies and worked at a non-profit that provides legal resources and policy analysis to immigrants and immigration advocates.

Do you have any interests outside of school?

Honestly? Not really… But when I’m not thinking about school, I sometimes read, go on walks, or explore all the exciting things Madison has to offer.

That’s a little sad. But since you love school so much, I bet you have exceptionally exciting research interests?

I’m really interested in the ways LGBT activists have responded to political and social changes, and how their efforts have impacted the everyday lives of LGBT communities. Because of the incredible diversity among LGBT communities, I use intersectional approaches to better understand how various segments of our community are affected, or even created by these changes.

Oh, awesome! Do you use oral history or interviews in your research?

Absolutely! I had the good fortune to take a class on oral history methods in college, and I fell in love with it right away. Since then, I’ve been involved with multiple oral history projects, and I think it is one of the best tools available to preserve a community’s memories. Because I study the very recent past, I’m lucky to be able to use interviews and oral histories extensively in my research.

You’ll fit in just fine here then — perhaps even better than I did. Speaking of, what are you looking forward to about this position?

I’m most looking forward to meeting and interacting with people who are using oral history to accomplish new and interesting things. The Oral History Review has featured some really great articles on things like using Google Glass for interviews, and using oral history to document the lives of people with schizophrenia. I’m excited to learn more about novel uses of oral history.

Thanks for noticing! I (and Troy) have worked hard to keep up with the latest trends in the field and to shine a spotlight on all the great work oral historians have been doing. Any concerns about taking over?

Definitely! Like most academic types, I find it easier to write 30 pages than 140 characters, but hopefully I’ll learn some brevity. You’ve done a really great job of preparing and sharing high quality posts through Oral History Review’s social media outlets, and I hope I can continue to provide an enjoyable experience for all of our followers!

I’m sure you’ll do great. Best of luck!

* * * * *

Andrew has already taken over all the social media platforms, so you should feel free to bombard him with questions at @oralhistreview, in the comments below or via the other 3 million social media accounts he now runs. He and I will also be at the upcoming annual meeting in October, so be sure to say hi — and goodbye.

Image credit: Cropped close-up of two hands passing a relay baton against a white background. © chaiyon021 via iStockphoto.

The post So Long, Farewell appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMigratory patterns: H-OralHist finds a new home on H-Net CommonsA preview of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingOral history, historical memory, and social change in West Mount Airy

Related StoriesMigratory patterns: H-OralHist finds a new home on H-Net CommonsA preview of the 2014 OHA Annual MeetingOral history, historical memory, and social change in West Mount Airy

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers