Oxford University Press's Blog, page 758

September 28, 2014

The pros and cons of research preregistration

Research transparency is a hot topic these days in academia, especially with respect to the replication or reproduction of published results.

There are many initiatives that have recently sprung into operation to help improve transparency, and in this regard political scientists are taking the lead. Research transparency has long been a focus of effort of The Society for Political Methodology, and of the journal that I co-edit for the Society, Political Analysis. More recently the American Political Science Association (APSA) has launched an important initiative in Data Access and Research Transparency. It’s likely that other social sciences will be following closely what APSA produces in terms of guidelines and standards.

One way to increase transparency is for scholars to “preregister” their research. That is, they can write up their research plan and publish that prior to the actual implementation of their research plan. A number of social scientists have advocated research preregistration, and Political Analysis will soon release new author guidelines that will encourage scholars who are interested in preregistering their research plans to do so.

However, concerns have been raised about research preregistration. In the Winter 2013 issue of Political Analysis, we published a Symposium on Research Registration. This symposium included two longer papers outlining the rationale for registration: one by Macartan Humphreys, Raul Sanchez de la Sierra, and Peter van der Windt; the other by Jamie Monogan. The symposium included comments from Richard Anderson, Andrew Gelman, and David Laitin.

In order to facilitate further discussion of the pros and cons of research preregistration, I recently asked Jaime Monogan to write a brief essay that outlines the case for preregistration, and I also asked Joshua Tucker to write about some of the concerns that have been raised about how journals may deal with research preregistration.

* * * * *

The pros of preregistration for political science

By Jamie Monogan, Department of Political Science, University of Georgia

Howard Tilton Library Computers, Tulane University by Tulane Public Relations. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Howard Tilton Library Computers, Tulane University by Tulane Public Relations. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Study registration is the idea that a researcher can publicly release a data analysis plan prior to observing a project’s outcome variable. In a Political Analysis symposium on this topic, two articles make the case that this practice can raise research transparency and the overall quality of research in the discipline (“Humphreys, de la Sierra, and van der Windt 2013; Monogan 2013).

Together, these two articles describe seven reasons that study registration benefits our discipline. To start, preregistration can curb four causes of publication bias, or the disproportionate publishing of positive, rather than null, findings:

Preregistration would make evaluating the research design more central to the review process, reducing the importance of significance tests in publication decisions. Whether the decision is made before or after observing results, releasing a design early would highlight study quality for reviewers and editors.

Preregistration would help the problem of null findings that stay in the author’s file drawer because the discipline would at least have a record of the registered study, even if no publication emerged. This will convey where past research was conducted that may not have been fruitful.

Preregistration would reduce the ability to add observations to achieve significance because the registered design would signal in advance the appropriate sample size. It is possible to monitor the analysis until a positive result emerges before stopping data collection, and this would prevent that.

Preregistration can prevent fishing, or manipulating the model to achieve a desired result, because the researcher must describe the model specification ahead of time. By sorting out the best specification of a model using theory and past work ahead of time, a researcher can commit to the results of a well-reasoned model.

Additionally, there are three advantages of study registration beyond the issue of publication bias:

Preregistration prevents inductive studies from being written-up as deductive studies. Inductive research is valuable, but the discipline is being misled if findings that are observed inductively are reported as if they were hypothesis tests of a theory.

Preregistration allows researchers to signal that they did not fish for results, thereby showing that their research design was not driven by an ideological or funding-based desire to produce a result.

Preregistration provides leverage for scholars who face result-oriented pressure from financial benefactors or policy makers. If the scholar has committed to a design beforehand, the lack of flexibility at the final stage can prevent others from influencing the results.

Overall, there is an array of reasons why the added transparency of study registration can serve the discipline, chiefly the opportunity to reduce publication bias. Whatever you think of this case, though, the best way to form an opinion about study registration is to try it by preregistering one of your own studies. Online study registries are available, so you are encouraged to try the process yourself and then weigh in on the preregistration debate with your own firsthand experience.

* * * * *

Experiments, preregistration, and journals

By Joshua Tucker, Professor of Politics (NYU) and Co-Editor, Journal of Experimental Political Science

I want to make one simple point in this blog post: I think it would be a mistake for journals to come up with any set of standards that involves publically recognizing some publications as having “successfully” followed their pre-registration design while identifying others publications as not having done so. This could include a special section for articles that matched their pre-registration design, an A, B, C type rating system for how faithfully articles had stuck with the pre-registration design, or even an asterisk for articles that passed a pre-registration faithfulness bar.

Let me be equally clear that I have no problem with the use of registries for recording experimental designs before those experiments are implemented. Nor do I believe that these registries should not be referenced in published works featuring the results of those experiments. On the contrary, I think authors who have pre-registered designs ought to be free to reference what they registered, as well as to discuss in their publications how much the eventual implementation of the experiment might have differed from what was originally proposed in the registry and why.

My concern is much more narrow: I want to prevent some arbitrary third party from being given the authority to “grade” researchers on how well they stuck to their original design and then to be able to report that grade publically, as opposed to simply allowing readers to make up their own mind in this regard. My concerns are three-fold.

First, I have absolutely no idea how such a standard would actually be applied. Would it count as violating a pre-design registry if you changed the number of subjects enrolled in a study? What if the original subject pool was unwilling to participate for the planned monetary incentive, and the incentive had to be increased, or the subject pool had to be changed? What if the pre-registry called for using one statistical model to analyze the data, but the author eventually realized that another model was more appropriate? What if survey questions that was registered on a 1-4 scale was changed to a 1-5 scale? Which, if any of these, would invalidate the faithful application of the registry? Would all of them together? It seems to the only truly objective way to rate compliance is to have an all or nothing approach: either you do exactly what you say you do, or you didn’t follow the registry. Of course, then we are lumping “p-value fishing” in the same category as applying a better a statistical model or changing the wording of a survey question.

This bring me to my second point, which is a concern that giving people a grade for faithfully sticking to a registry could lead to people conducting sub-optimal research — and stifle creativity — out of fear that it will cost them their “A” registry-faithfulness grade. To take but one example, those of us who use survey experiments have long been taught to pre-test questions precisely because sometime some of the ideas we have when sitting at our desks don’t work in practice. So if someone registers a particular technique for inducing an emotional response and then runs a pre-test and figures out their technique is not working, do we really want the researcher to use the sub-optimal design in order to preserve their faithfulness to the registered design? Or consider a student who plans to run a field experiment in a foreign country that is based on the idea that certain last names convey ethnic identity. What happens if the student arrives in the field and learns that this assumption was incorrect? Should the student stick with the bad research design to preserve the ability to publish in the “registry faithful” section of JEPS? Moreover, research sometimes proceeds in fits and spurts. If as a graduate student I am able to secure funds to conduct experiments in country A but later as a faculty member can secure funds to replicate these experiments in countries B and C as well, should I fear including the results from country A in a comparative analysis because my original registry was for a single country study? Overall, I think we have to be careful about assuming that we can have everything about a study figured out at the time we submit a registry design, and that there will be nothing left for us to learn about how to improve the research — or that there won’t be new questions that can be explored with previously collected data — once we start implementing an experiment.

At this point a fair critique to raise is that the points in preceding paragraph could be taken as an indictment of registries generally. Here we venture more into simply a point of view, but I believe that there is a difference between asking people to document what their original plans were and giving them a chance in their own words — if they choose to do so — to explain how their research project evolved as opposed to having to deal with a public “grade” of whatever form that might take. In my mind, the former is part of producing transparent research, while the latter — however well intentioned — could prove paralyzing in terms of making adjustments during the research process or following new lines of interesting research.

This brings me to my final concern, which is that untenured faculty would end up feeling the most pressure in this regard. For tenured faculty, a publication without the requisite asterisks noting registry compliance might not end up being too big a concern — although I’m not even sure of that — but I could easily imagine junior faculty being especially worried that publications without registry asterisks could be held against them during tenure considerations.

The bottom line is that registries bring with them a host of benefits — as Jamie has nicely laid out above — but we should think carefully about how to best maximize those benefits in order to minimize new costs. Even if we could agree on how to rate a proposal in terms of faithfulness to registry design, I would suggest caution in trying to integrate ratings into the publication process.

The views expressed here are mine alone and do not represent either the Journal of Experimental Political Science or the APSA Organized Section on Experimental Research Methods.

Heading image: Interior of Rijksmuseum research library. Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed. CC-BY-SA-3.0-nl via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The pros and cons of research preregistration appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesQ&A with Jake Bowers, co-author of 2014 Miller Prize PaperWho decides ISIS is a terrorist group?Research replication in social science: reflections from Nathaniel Beck

Related StoriesQ&A with Jake Bowers, co-author of 2014 Miller Prize PaperWho decides ISIS is a terrorist group?Research replication in social science: reflections from Nathaniel Beck

September 27, 2014

Cinematic tragedies for the intractable issues of our times

Tragedies certainly aren’t the most popular types of performances these days. When you hear a film is a tragedy, you might think “outdated Ancient Greek genre, no thanks!” Back in those times, Athenians thought it their civic duty to attend tragic performances of dramas like Antigone or Agammemnon. Were they on to something that we have lost in contemporary Western society? That there is something specifically valuable in a tragic performance that a spectator doesn’t get from other types or performances, such as those of our modern genres of comedy, farce, and melodrama?

Since films reach a greater audience in our culture than plays, after updating Aristotle’s Poetics for the twenty-first century, we analyzed what we call “cinematic tragedies”: films that demonstrate the key components of Aristotelian tragedy. We conclude that a tragedy must consist in the representation of an action that is: (1) complete; (2) serious; (3) probable; (4) has universal significance; (5) involves a reversal of fortune (from good to bad); (6) includes recognition (a change in epistemic state from ignorance to knowledge); (7) includes a specific kind of irrevocable suffering (in the form of death, agony or a terrible wound); (8) has a protagonist who is capable of arousing compassion; and (9) is performed by actors. The effects of the tragedy must include: (10) the arousal in the spectator of pity and fear; and (11) a resolution of pity and fear that is internal to the experience of the drama.

Unlike melodrama (which we hold is the most common film genre), tragedy calls on spectators to ponder thorny moral issues and to navigate them with their own moral compass. One such cinematic tragedy — Into The Wild, 2007, directed by Sean Penn — thematizes the preciousness and precariousness of human life alongside environmental problems, raising questions about human beings’ apparent inability to live on earth without despoiling the beauty and integrity of the biosphere. Other cinematic tragedies deal with a variety of problems with which our modern societies must grapple.

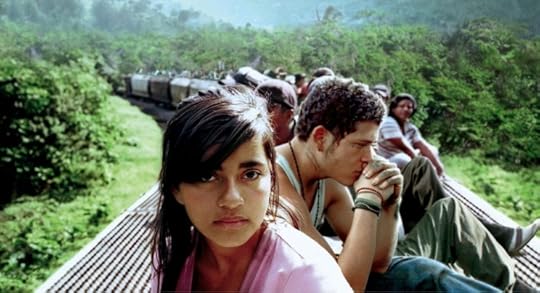

One such topic is illegal immigration, a highly politicized issue that is far more complex than national governments seem equipped to handle, especially beyond the powers of the two parties in the American system. Cinematic tragedies that deal with this issue have been produced over several decades involving immigration into various Western countries, especially the United States; these include Black Girl (France, 1966), El norte (US/UK, 1983), and Sin nombre (Mexico, 2009), the last of which we will expand on here.

Paulina Gaitan (left) and Edgar Flores (right) star in writer/director Cary Joji Fukunaga’s epic dramatic thriller Sin Nombre, a Focus Features release. Photo credit: Cary Joji Fukunaga via Focus Features

Paulina Gaitan (left) and Edgar Flores (right) star in writer/director Cary Joji Fukunaga’s epic dramatic thriller Sin Nombre, a Focus Features release. Photo credit: Cary Joji Fukunaga via Focus FeaturesIn US director Cary Fukunaga’s Sin nombre (which means “Nameless” but which was released in the United States under the Spanish title), Hondurans escaping from their harsh political and economic realities risk their lives in order to make it to the United States, through Mexico, on the tops of rail cars. They travel in this manner since, as we all know, there would be no other legal way for most of these foreign citizens to come to the United States. Over the course of the journey, the immigrants endure terrible suffering or die at the hands of gang members who rob, rape, and even kill some of them.

The film focuses on just a few of the multitudes atop the trains: on a teenage Honduran girl, Sayra, migrating with her father and uncle; and on a few of the gang members. One of them, Casper, has had a change of heart and is no longer loyal to the gang, after its leader killed Casper’s girlfriend after trying to rape her. Casper and other gang members are atop the train robbing the migrants, but he defends Sayra by killing the leader when he tries to rape her. Ultimately, Sayra will arrive in the United States. However, she realizes that the cost has been too great—her father has died falling off of the train; she has lost Casper who is, ironically, shot to death by the pre-pubescent boy whom he himself had trained in the ways of the gang in the opening scenes of the film.

The tremendous losses, and the scenes of suffering, rape, and murder, make unlikely the possibility that the spectator will feel that Sayra’s arrival constitutes a happy ending. In some other aesthetic treatment, Casper’s ultimate death might have been melodramatized as redemptive selflessness for the sake of his new girlfriend. But in Fukunaga’s film, the juxtaposed images imply a continuing cycle of despair and death: Casper’s young killer in Mexico is promoted up the ranks of the gang with a new tattoo, while Sayra’s uncle, back in Honduras after being deported from Mexico, starts the voyage to the United States all over again. Sayra too may face deportation in the future. Following the scene of the reinvigoration of the criminal gang system, as its new young leader gets his first tattoo, the viewer sees Sayra outside a shopping mall in the American southwest. The teenage girl has arrived in the United States and may aspire to participate in advanced consumer capitalism, yet she has lost so much and suffered so undeservingly.

This aesthetic juxtaposition prompts the spectator to attend to the failure of Western political leaders to create a humane system of immigration for the twenty-first century, one which cannot be reached with the entrenched politicized views of the “two sides of the aisle” who miss the human story of immigrants’ plight. This film—like all tragedies—promotes the spectator’s active pondering, that is, it challenges them to respond in some way.

In the tradition of philosophers as various as Aristotle, Seneca, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Martha Nussbaum, and Bernard Williams, we find that tragedies bring to conscious awareness the most significant moral, social, political, and existential problems of the human condition. A film such as Sin nombre, through its tragic performance, points to one of these terrible necessities with which our contemporary Western culture must grapple. While it doesn’t offer an answer, this cinematic tragedy prompts us to recognize and deal with a seemingly intractable problem that needs to move beyond the current impasse of political debate, as we in the industrialized nations continue to shop for and watch movies in the comfort of our malls.

The post Cinematic tragedies for the intractable issues of our times appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDo children make you happier?Q&A with Jake Bowers, co-author of 2014 Miller Prize PaperDo health apps really matter?

Related StoriesDo children make you happier?Q&A with Jake Bowers, co-author of 2014 Miller Prize PaperDo health apps really matter?

World War I in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations

Coverage of the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War has made us freshly familiar with many memorable sayings, from Edward Grey’s ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe’, to Wilfred Owen’s ‘My subject is War, and the pity of war/ The Poetry is in the pity’, and Lena Guilbert Horne’s exhortation to ‘Keep the Home-fires burning’.

But as I prepared the new edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, I was aware that numerous other ‘quotable quotes’ also shed light on aspects of the conflict. Here are just five.

One vivid evocations of the conflict striking passage comes not from a War Poet but from an American novelist writing in the 1930s. In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night (1934), Dick Diver describes the process of trench warfare:

See that little stream—we could walk to it in two minutes. It took the British a month to walk it—a whole empire walking very slowly, dying in front and pushing forward behind. And another empire walked very slowly backward a few inches a day, leaving the dead like a million bloody rugs.

This was, of course, on the Western Front, but there were other theatres of war. One such was the Gallipoli Campaign of 1915–16, where many ‘Anzacs’ lost their lives. In 1934, a group of Australians visited Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, and heard an address by Kemal Atatürk—Commander of the Turkish forces during the war, and by then President of Turkey. Speaking of the dead on both sides, he said:

There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side in this country of ours. You, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries, wipe away your tears. Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.

Atatürk’s words were subsequently inscribed on the memorial at Gallipoli, and on memorials in Canberra and Wellington.

World War I is often is often seen as a watershed, after which nothing could be the same again. (The young Robert Graves’s autobiography published in 1929 was entitled Goodbye to All That.) Two quotations from ODQ look ahead from the end of the war to what might be the consequences. For Jan Christiaan Smuts, President of South Africa, the moment was one of promise. He saw the setting up of the League of Nations in the aftermath of the war as a hope for better things:

Mankind is once more on the move. The very foundations have been shaken and loosened, and things are again fluid. The tents have been struck, and the great caravan of humanity is once more on the march.

However a much less optimistic, and regrettably more prescient comment, had been recorded in 1919 by Marshal Foch on the Treaty of Versailles,

This is not a peace treaty, it is an armistice for twenty years.

Not all ‘war poems’ are immediately recognizable as such. In 1916, the poet and army officer Frederick William Harvey was made a prisoner of war (the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography tells us that he went on to experience seven different prison camps). Returning from a period of solitary confinement, he apparently noticed the drawing of a duck on water made by a fellow-prisoner. This inspired what has become a very well-loved poem.

From troubles of the world

I turn to ducks

Beautiful comical things.

How many people, encountering the poem today, consider that the ‘troubles’ might include a world war?

Headline image credit: A message-carrying pigeon being released from a port-hole in the side of a British tank, near Albert, France. Photo by David McLellan, August 1918. Imperial War Museums. IWM Non-Commercial License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post World War I in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPlagiarism and patriotismThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biographyA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1

Related StoriesPlagiarism and patriotismThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biographyA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1

Why do you love the VSIs?

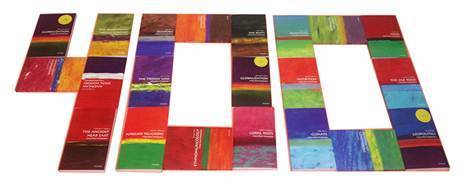

The 400th Very Short Introduction, ‘Knowledge‘, was published this week. In order to celebrate this remarkable series, we asked various colleagues at Oxford University Press to explain why they love the VSIs:

* * * * *

“Why do I love the VSIs? They’re an easy, yet comprehensive way to learn about a topic. From general topics like Philosophy to more specific like Alexander the Great, I finish the book after a few trips on the train and I feel smarter. VSIs also help to quickly fill knowledge gaps that I may have–I never took a chemistry class in college but in just 150 pages, I can have a better understanding of physical chemistry should it ever come up during a trivia challenge. It’s true, VSIs give you the knowledge so you can lead your team to victory at your next pub trivia challenge.”

— Brian Hughes, Senior Platform Marketing Manager

* * * * *

“They’re very effective knowledge pills after taking which I feel so much better equipped for exploring new disciplines. Each ends with a very helpful bibliography section which is a great guide for getting more and more interested in the subject. They’re concise, authoritative and fun to read, and that’s precisely why I love them so much!”

— Anna Ready, Online Project Manager

* * * * *

“I love VSIs because it’s like talking to an expert who is approachable and personable, and doesn’t mind if it takes you a while to understand what they’re saying! They walk you through difficult ideas and concepts in an easily understandable way and you come away feeling like you have a deeper understanding of the topic, often wanting to find out more.”

— Hannah Charters, Senior Marketing Executive

‘VSI 400 cake’, by Jack Campbell-Smith. Image used with permission.

‘VSI 400 cake’, by Jack Campbell-Smith. Image used with permission.

* * * * *

“With the VSI series, you can expect to see a clear explanation of the subject matter presented in a consistent style.”

— Martin Buckmaster, Data Engineer

* * * * *

“A book is a gift. The precious gift of knowledge hard earned by humankind through generations of experience, deep contemplation and a bursts of single minded desire to push the very limits of curiosity. But I’m a postmodern man in a postmodern world; my attention span is wrecked and presented with all the information in the world at my fingertips the best I can manage is to look up pictures of cats. I don’t know what I need to know from what I don’t or even where to start. What I need is a starting point, a rock solid foundation of just what I need to know on the topic of my choice, enough to know if I want to know more, enough to light that old spark of curiosity and easily enough to win an argument down the pub. Not just the gift of knowledge, but the gift of time. That’s why I love VSIs.”

— Anonymous

* * * * *

“I love the VSIs because there is a never ending supply of interesting topics to learn more about. Whenever I found out I would be taking on the Religion & Theology list, I raided my neighbors cubicles for any religion-themed VSIs to read. Whenever I’m out of a book for the train ride home, I go next door to the VSI Marketing Manger’s cubicle, to see what new VSIs she has that I can borrow. They’re the perfect book to fit in your purse and go.”

— Alyssa Bender, Marketing Coordinator

* * * * *

“I told Mrs Dalloway’s this week that purchasing the VSIs from Oxford was just like printing money. They’re smaller than an electronic reading device and fit in my cargo shorts, I mean blazer pocket. I can’t wait for Translation: A Very Short Introduction.”

— George Carroll, Commissioning Rep from Great Northwest, USA

* * * * *

“I love the VSI series because it is so wonderfully wide-ranging. With almost any topic that comes to mind, if I wonder ‘is there a VSI to that?’, the answer is usually yes. It’s a great way to learn a little more about an area you’re already interested in, or as a first foray into one which is entirely new. Long live VSIs!”

— Simon Thomas, Oxford Dictionaries Marketing Executive

* * * * *

“VSIs allow me to sound like I know a lot more about a subject than I actually do, in a very short space of time. An essential cheat for job interviews, pub quizzes, dates etc.”

— Rachel Fenwick, Associate Marketing Manager

* * * * *

“I love the VSIs because they make such broad subjects immediately accessible. If you ever want to understand a subject in its entirety or fill in the gaps in your knowledge, the VSIs should always be your first port of call. From my University studies to my morning commute, the VSIs have, without fail, filled in the gaping holes in my knowledge and allowed me to converse with much smarter people about subjects I would never have previously understood. For that, I’m very grateful!”

— Daniel Parker, Social Media Executive

The post Why do you love the VSIs? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor?What commuters know about knowingThe vision of Confucius

Related StoriesWhat’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor?What commuters know about knowingThe vision of Confucius

September 26, 2014

Do health apps really matter?

Apps are all the rage nowadays, including apps to help fight rage. That’s right, the iTunes app store contains several dozen apps designed to manage anger or reduce stress. Smartphones have become such a prevalent component of everyday life, it’s no surprise that a demand has risen for phone programs (also known as apps) that help us manage some of life’s most important elements, including personal health. But do these programs improve our ability to manage our health? Do health apps really matter?

Early apps for patients with diabetes demonstrate how a proposed app idea can sound useful in theory but provide limited tangible health benefits in practice. First generation diabetes apps worked like a digital notebook, in which apps linked with blood glucose monitors to record and catalog measured glucose levels. Although doctors and patients were initially charmed by high tech appeal and app convenience, the charm wore off as app use failed to improve patient glucose monitoring habits or medication compliance.

Fitness apps are another example of rough starts among early health app attempts. Initial running apps served as an electronic pedometer, recording the number of steps and/or the total distance ran. These apps again provided a useful convenience over using a conventional pedometer, but were unlikely to lead to increased exercise levels or appeal to individuals who didn’t already run. Apps for other health related topics such as nutrition, diet, and air pollution ran into similar limitations in improving healthy habits. For a while, it seemed as if the initial excitement among the life sciences community for e-health simply couldn’t be translated to tangible health benefits among target populations.

Image credit: Personal Health Apps for Smartphones.jgp, by Intel Free Press. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Personal Health Apps for Smartphones.jgp, by Intel Free Press. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Luckily, recent changes in app development ideology have led to noticeable increases in health app impacts. Health app developers are now focused on providing useful tools, rather than collections of information, to app users. The diabetes app ManageBGL.com, for example, predicts when a patient may develop hypoglycemia (low blood sugar levels) before the visual/physical signs and adverse effects of hypoglycemia occur. The running app RunKeeper connects to other friend’s running profiles to share information, provide suggested running routes, and encourage runners to speed up or slow down for reaching a target pace. Air pollution apps let users set customized warning levels, and then predict and warn users when they’re heading towards an area with air pollution that exceeds warning levels. Health apps are progressing beyond providing mere convenience towards a state where they can help the user make informed decisions or perform actions that positively affect and/or protect personal health.

So, do health apps really matter? It’s unlikely that the next generation of health apps will have the same popularity as Facebook or widespread utility such as Google maps. The impact, utility, and popularity of health apps, however, are increasing at a noticeable rate. As health app developers continue to better their understanding of health app strengths and limitations and upcoming technologies that can improve health apps such as miniaturized sensors and smartglass become available, the importance of health related apps and proportion of the general public interested in health apps are only going to get larger.

The post Do health apps really matter? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDo children make you happier?Intergenerational perspectives on psychology, aging, and well-beingLearning with body participation through motion-sensing technologies

Related StoriesDo children make you happier?Intergenerational perspectives on psychology, aging, and well-beingLearning with body participation through motion-sensing technologies

Plagiarism and patriotism

Thou shall not plagiarize. Warnings of this sort are delivered to students each fall, and by spring at least a few have violated this academic commandment. The recent scandal involving Senator John Walsh of Montana, who took his name off the ballot after evidence emerged that he had copied without attribution parts of his master’s thesis, shows how plagiarism can come back to haunt.

But back in the days of 1776, plagiarism did not appear as a sign of ethical weakness or questionable judgment. Indeed, as the example of Mercy Otis Warren suggests, plagiarism was a tactic for spreading Revolutionary sentiments.

An intimate of American propagandists such as Sam Adams, Warren used her rhetorical skill to pillory the corrupt administration of colonial Massachusetts. She excelled at producing newspaper dramas that savaged the governor, Thomas Hutchinson, and his cast of flunkies and bootlickers. Her friend John Adams helped arrange for the anonymous publication of satires so sharp that they might well have given readers paper cuts.

An expanded version soon followed, replete with new scenes in which patriot leaders inspired crowds to resist tyrants. Although the added material uses her characters and echoes her language, they were not written by Warren. As she tells the story, her original drama was “taken up and interlarded with the productions of an unknown hand. The plagiary swelled” her satirical sketch into a pamphlet.

Portrait of Mercy Otis Warren, American writer, by John Singleton Copley (1763). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Mercy Otis Warren, American writer, by John Singleton Copley (1763). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. But Warren didn’t seem to mind the trespass all that much. Her goal was to disseminate the critique of colonial government. There’s evidence that she intentionally left gaps in her plays so that readers could turn author and add new scenes to the Revolutionary drama.

Original art was never the point; instead art suitable for copying formed the basis of her public aesthetic. In place of authenticity, imitation allowed others to join the cause and continue the propagation of Revolutionary messages.

Could it be that plagiarism was patriotic?

Thankfully, this justification is not likely to hold up in today’s classroom. There’s no compelling national interest that requires a student to buy and download a paper on Heart of Darkness.

Warren’s standards are woefully out of date. And yet, she does offer a lesson about political communication that still has relevance. Where today we see plagiarism, she saw a form of dissent had been made available to others.

Headline image credit: La balle a frappé son amante, gravé par L. Halbou. Library of Congress.

The post Plagiarism and patriotism appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFrom “Checkers” to WatergateCaught in Satan’s StormWhat’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor?

Related StoriesFrom “Checkers” to WatergateCaught in Satan’s StormWhat’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor?

Do children make you happier?

A new study shows that women who have difficulty accepting the fact that they can’t have children following unsuccessful fertility treatment, have worse long-term mental health than women who are able to let go of their desire for children. It is the first to look at a large group of women (over 7,000) to try to disentangle the different factors that may affect women’s mental health over a decade after unsuccessful fertility treatment. These factors include whether or not they have children, whether they still want children, their diagnosis, and their medical treatment.

It was already known that people who have infertility treatment and remain childless have worse mental health than those who do manage to conceive with treatment. However, most previous research assumed that this was due exclusively to having children or not, and did not consider the role of other factors. Alongside my research colleagues from the Netherlands, where the study took place, we found only that there is a link between an unfulfilled wish for children and worse mental health, and not that the unfulfilled wish is causing the mental health problems. This is due to the nature of the study, in which the women’s mental health was measured at only one point in time rather than continuously since the end of fertility treatment.

We analysed answers to questionnaires completed by 7,148 women who started fertility treatment at any of 12 IVF hospitals in the Netherlands between 1995-2000. The questionnaires were sent out to the women between January 2011 and 2012, meaning that for most women their last fertility treatment would have been between 11-17 years ago. The women were asked about their age, marital status, education and menopausal status, whether the infertility was due to them, their partner, both or of unknown cause, and what treatment they had received, including ovarian stimulation, intrauterine insemination, and in vitro fertilisation / intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI). In addition, they completed a mental health questionnaire, which asked them how they felt during the past four weeks. The women were asked whether or not they had children, and, if they did, whether they were their biological children or adopted (or both). They were also asked whether they still wished for children.

The majority of women in the study had come to terms with the failure of their fertility treatment. However, 6% (419) still wanted children at the time of answering the study’s questionnaire and this was connected with worse mental health. We found that women who still wished to have children were up to 2.8 times more likely to develop clinically significant mental health problems than women who did not sustain a child-wish. The strength of this association varied according to whether women had children or not. For women with no children, those with a child-wish were 2.8 times more likely to have worse mental health than women without a child-wish. For women with children, those who sustained a child-wish were 1.5 times more likely to have worse mental health than those without a child-wish. This link between a sustained wish for children and worse mental health was irrespective of the women’s fertility diagnosis and treatment history.

Happy family photo by Vera Kratochvil. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Happy family photo by Vera Kratochvil. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Our research found that women had better mental health if the infertility was due to male factors or had an unknown cause. Women who started fertility treatment at an older age had better mental health than women who started younger, and those who were married or cohabiting with their partner reported better mental health than women who were single, divorced, or widowed. Better educated women also had better mental health than the less well educated.

This study improves our understanding of why childless people have poorer adjustment. It shows that it is more strongly associated with their inability to let go of their desire to have children. It is quite striking to see that women who do have children but still wish for more children report poorer mental health than those who have no children but have come to accept it. The findings underline the importance of psychological care of infertility patients and, in particular, more attention should be paid to their long-term adjustment, whatever the outcome of the fertility treatment.

The possibility of treatment failure should not be avoided during treatment and a consultation at the end of treatment should always happen, whether the treatment is successful or unsuccessful, to discuss future implications. This would enable fertility staff to identify patients more likely to have difficulties adjusting to the long term, by assessing the women’s possibilities to come to terms with their unfulfilled child-wish. These patients could be advised to seek additional support from mental health professionals and patient support networks.

It is not known why some women may find it more difficult to let go of their child-wish than others. Psychological theories would claim that how important the goal is for the person would be a relevant factor. The availability of other meaningful life goals is another relevant factor. It is easier to let go of a child-wish if women find other things in life that are fulfilling, like a career.

We live in societies that embrace determination and persistence. However, there is a moment when letting go of unachievable goals (be it parenthood or other important life goals) is a necessary and adaptive process for well-being. We need to consider if societies nowadays actually allow people to let go of their goals and provide them with the necessary mechanisms to realistically assess when is the right moment to let go.

Featured image: Baby feet by Nina-81. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Do children make you happier? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesQ&A with Jake Bowers, co-author of 2014 Miller Prize PaperIntergenerational perspectives on psychology, aging, and well-beingThe Hunger Games and a dystopian Eurozone economy

Related StoriesQ&A with Jake Bowers, co-author of 2014 Miller Prize PaperIntergenerational perspectives on psychology, aging, and well-beingThe Hunger Games and a dystopian Eurozone economy

What’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor?

With the 400th Very Short Introduction on the topic of ‘Knowledge’ publishing this month, I’ve been thinking about how long this series has been around, and how long I have been a commissioning editor for the series, from before the 200th VSI published (number 163 – Human Rights in fact), through number 300 and 400, and how undoubtedly I’ll still be here for the 500th VSI!

Having previously been an editor for law, tax, and accountancy lists, and latterly the OUP Police list, the opportunity to be the VSI editor was one that I simply could not pass up. I already owned, and had read, several VSIs, so I understood broadly what the series was trying to do and who the series was aimed at. I liked the idea of working across a wide range of topics (except science – these VSIs are commissioned by my esteemed colleague Latha Menon) and with a vast array of different authors. I also liked the idea that I would learn lots of new things and be a pub quiz team whizz. Unfortunately in order to be good at pub quizzes you have to be able to retain and recall information and details quickly. I like to think that if someone was able to explore deep inside my brain they would find hundreds of fascinating facts about hundreds of topics that are buried in there somewhere. (What has been exciting is to have on occasion been able to answer a University Challenge question, causing much excitement).

I naively thought that authors would be able to write 35,000 (or so) words easily and quickly, and therefore that they would deliver perfect manuscripts on time which would be easy to edit and a pleasure to read. For the most part I think this is true, but in my seven years as editor, I think I’ve seen and heard it all. ‘The dog ate my homework’ excuses, authors taking eight or nine years to deliver their manuscripts, and one author delivering a 70,000 word manuscript thinking that we could just ‘cut it a little’. There’s never a dull moment. I’ve seen ebooks come into fruition, an online service being launched, and new editions of old and popular VSIs come into being. Marketing has changed too, from the traditional brochure and bookshop displays, to YouTube videos, Facebook pages, and blog posts.

“VSI 400″ image courtesy of VSI editorial team.

“VSI 400″ image courtesy of VSI editorial team. I often get asked what I do all day. The myth is that I do a lot of wining and dining, drinking coffee, putting my feet up on the desk reading manuscripts, and jetting to conferences. The reality is that I do a bit of everything and it doesn’t involve enough wining and dining – the tax authors ten years ago were far worse for this! I decide (with input from sales, marketing, the US VSI editor, and the science VSI editor) what topics to commission, I seek out the best authors I possibly can, I negotiate contracts, I talk to agents, I read manuscripts, I look at cover blurbs, and I panic about the size of my overflowing inbox.

People also ask me what my favourite VSI is, which is a very difficult question to answer. The first VSI I ever read was Mary Beard and John Henderson’s Classics (number 1 in the series) and I still think it’s a wonderful book. Of those I’ve commissioned, I love Angels and English Literature. And who is my favourite author? Now that would be telling, but I have passed countless happy hours with many of my authors. And that’s the best thing about being the VSI editor. I get to meet so many different authors and help them turn their vast amount of knowledge (and sometimes their lifetime’s work) into a short book that they can be proud of. My favourite quote from an author is, ‘now my children, grandchildren and friends might finally understand what I do’!

The post What’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat commuters know about knowingThe vision of ConfuciusThe ubiquity of structure

Related StoriesWhat commuters know about knowingThe vision of ConfuciusThe ubiquity of structure

September 25, 2014

Q&A with Jake Bowers, co-author of 2014 Miller Prize Paper

Despite what many of my colleagues think, being a journal editor is usually a pretty interesting job. The best part about being a journal editor is working with authors to help frame, shape, and improve their research. We also have many chances to honor specific authors and their work for being of particular importance. One of those honors is the Miller Prize, awarded annually by the Society for Political Methodology for the best paper published in Political Analysis the proceeding year.

The 2013 Miller Prize was awarded to Jake Bowers, Mark M. Fredrickson, and Costas Panagopoulos, for their paper, “Reasoning about Interference Between Units: A General Framework.” To recognize the significance of this paper, it is available for free online access for the next year. The award committee summarized the contribution of the paper:

“..the article tackles an difficult and pervasive problem—interference among units—in a novel and compelling way. Rather than treating spillover effects as a nuisance to be marginalized over or, worse, ignored, Bowers et al. use them as an opportunity to test substantive questions regarding interference … Their work also brings together causal inference and network analysis in an innovative and compelling way, pointing the way to future convergence between these domains.”

In other words, this is an important contribution to political methodology.

I recently posed a number of question to one of the authors of the Miller Prize paper, Jake Bowers, asking him to talk more about this paper and its origins.

R. Michael Alvarez: Your paper, “Reasoning about Interference Between Units: A General Framework” recently won the Miller Prize for the best paper published in Political Analysis in the past year. What motivated you to write this paper?

Jake Bowers: Let me provide a little background for readers not already familiar with randomization-based statistical inference.

Randomized designs provide clear answers to two of the most common questions that we ask about empirical research: The Interpretation Question: “What does it mean that people in group A act differently from people in group B?” and The Information Question: “How precise is our summary of A-vs-B?” (Or, more defensively, “Do we really have enough information to distinguish A from B?”).

If we have randomly assigned some A-vs-B intervention, then we can answer the interpretation question very simply: “If group A differs from group B, it is only because of the A-vs-B intervention. Randomization ought to erase any other pre-existing differences between groups A and B.”

In answering the information question, randomization alone also allows us to characterize other ways that the experiment might have turned out: “Here are all of the possible ways that groups A and B could differ if we re-randomized the A-vs-B intervention to the experimental pool while entertaining the idea that A and B do not differ. If few (or none) of these differences is as large as the one we observe, we have a lot of information against the idea that A and B do not differ. If many of these differences are as large as the one we see, we don’t have much information to counter the argument that A and B do not differ.”

Of course, these are not the only questions one should ask about research, and interpretation should not end with knowing that an input created an output. Yet, these concerns about meaning and information are fundamental and the answers allowed by randomization offer a particularly clear starting place for learning from observation. In fact, many randomization-based methods for summarizing answers to the information question tend to have validity guarantees even with small samples. If we really did repeat the experiment all the possible ways that it could have been done, and repeated a common hypothesis test many times, we would reject a true null hypothesis no more than α% of the time even if we had observed only eight people (Rosenbaum 2002, Chap 2).

In fact a project with only eight cities impelled this paper. Costa Panagopoulos had administered a field experiment of newspaper advertising and turnout to eight US cities, and he and I began to discuss how to produce substantively meaningful, easy to interpret, and statistically valid, answers to the question about the effect of advertising on turnout. Could we hypothesize that, for example, the effect was zero for three of the treated cites, and more than zero for one of the treated cites? The answer was yes.

I realized that hypotheses about causal effects do not need to be simple, and, furthermore, they could represent substantive, theoretical models very directly. Soon, Mark Fredrickson and I started thinking about substantive models in which treatment given to one city might have an effect on another city. It seemed straightforward to write down these models. We had read Peter Aronow’s and Paul Rosenbaum’s papers on the sharp null model of no effects and interference, and so we didn’t think we were completely off base to imagine that, if we side-stepped estimation of average treatment effects and focused on testing hypotheses, we could learn something about what we called “models of interference”. But, we had not seen this done before. So, in part because we worried about whether we were right about how simple it was to write down and test hypotheses generated from models of spillover or interference between units, we wrote the “Reasoning about Interference” paper to see if what we were doing with Panagopoulos’ eight cities would scale, and whether it would perform as randomization-based tests should. The paper shows that we were right.

R. Michael Alvarez: In your paper, you focus on the “no interference” assumption that is widely discussed in the contemporary literature on causal models. What is this assumption and why is it important?

Jake Bowers: When we say that some intervention, (Zi), caused some outcome for some person, (i), we often mean that the outcome we would have seen for person (i) when the intervention is not-active, (Zi=0) — written as (y{i,Zi=0}) — would have been different from the outcome we would have seen if the intervention were active for that same person (at that same moment in time), (Zi=1), — written as (y{i,Z_i=1}). Most people would say that the treatment had an effect on person (i) when (i) would have acted differently under the intervention than under the control condition such that y{i,Zi=1} does not equal y{i,Zi=0}. David Cox (1958) noticed that this definition of causal effects involves an assumption that an intervention assigned to one person does not influence the potential outcomes for another person. (Henry Brady’s piece, “Causation and Explanation in Social Science” in the Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology provides an excellent discussion of the no-interference assumption and Don Rubin’s formalization and generalization of Cox’s no-interference assumption.)

As an illustration of the confusion that interference can cause, imagine we had four people in our study such that (i in {1,2,3,4}). When we write that the intervention had an effect for person (i=1),(y{i=1,Z1=1} does not equal y{i=1,Z1=0}), we are saying that person 1 would act the same when (Z{i=1}=1) regardless of how intervention was assigned to any other person such that

(y{i=1,{Z_1=1,Z_2=1,Z_3=0,Z_4=0}}=y{i=1,{Z_1=1,Z_2=0,Z_3=1,Z_4=0\}}=y{i=1,\{Zi=1,…}})

If we do not make this assumption then we cannot write down a treatment effect in terms of a simple comparison of two groups. Even if we randomly assigned the intervention to two of the four people in this little study, we would have six potential outcomes per person rather than only two potential outcomes (you can see two of the six potential outcomes for person 1 in above). Randomization does not help us decide what a “treatment effect” means and six counterfactuals per person poses a challenge for the conceptualization of causal effects.

So, interference is a problem with the definition of causal effects. It is also a problem with estimation. Many folks know about what Paul Holland (1986) calls the “Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference” that the potential outcomes heuristic for thinking about causality reveals: we cannot ever know the causal effect for person (i) directly because we can never observe both potential outcomes. I know of three main solutions for this problem, each of which have to deal with problems of interference:

Jerzy Neyman (1923) showed that if we change our substantive focus from individual level to group level comparisons, and to averages in particular, then randomization would allow us to learn about the true, underlying, average treatment effect using the difference of means observed in the actual study (where we only see responses to intervention for some but not all of the experimental subjects). Don Rubin (1978) showed a Bayesian predictive approach — a probability model of the outcomes of your study and a probability model for the treatment effect itself allows you can predict the unobserved potential outcomes for each person in your study and then take averages of those predictions to produce an estimate of the average treatment effect. Ronald Fisher (1935) suggested another approach which maintained attention on the individual level potential outcomes, but did not use models to predict them. He showed that randomization alone allows you to test the hypothesis of “no effects” at the individual level. Interference makes it difficult to interpret Neyman’s comparisons of observed averages and Rubin’s comparison of predicted averages as telling us about causal effects because we have too many possible averages.It turns out that Fisher’s sharp null hypothesis test of no effects is simple to interpret even when we have unknown interference between units. Our paper starts from that idea and shows that, in fact, one can test sharp hypotheses about effects rather than only no effects.

Note that there has been a lot of great recent work trying to define and estimate average treatment effects recently by folks like Cyrus Samii and Peter Aronow, Neelan Sircar and Alex Coppock, Panos Toulis and Edward Kao, Tyler Vanderweele, Eric Tchetgen Tchetgen and Betsy Ogburn, Michael Sobel, and Michael Hudgens, among others. I also think that interference poses a smaller problem for Rubin’s approach in principle — one would add a model of interference to the list of models (of outcomes, of intervention, of effects) used to predict the unobserved outcomes. (This approach has been used without formalization in terms of counterfactuals in both the spatial and networks models worlds.) One might then focus on posterior distributions of quantities other than simple differences of averages or interpret such differences reflecting the kinds of weightings used in the work that I gestured to at the start of this paragraph.

R. Michael Alvarez: How do you relax the “no interference” assumption in your paper?

Jake Bowers: I would say that we did not really relax an assumption, but rather side-stepped the need to think of interference as an assumption. Since we did not use the average causal effect, we were not facing the same problems of requiring that all potential outcomes collapse down to two averages. However, what we had to do instead was use what Paul Rosenbaum might call Fisher’s solution to the fundamental problem of causal inference. Fisher noticed that, even if you couldn’t say that a treatment had an effect on person (i), you could ask whether we had enough information (in our design and data) to shed light on a question about whether or not the treatment had an effect on person (i). In our paper, Fisher’s approach meant that we did not need to define our scientifically interesting quantity in terms of averages. Instead, we had to write down hypotheses about no interference. That is, we did not really relax an assumption, but instead we directly modelled a process.

Rosenbaum (2007) and Aronow (2011), among others, had noticed that the hypothesis that Fisher is most famous for, the sharp null hypothesis of no effects, in fact does not assume no interference, but rather implies no interference (i.e., if the treatment has no effect for any person, then it does not matter how treatment has been assigned). So, in fact, the assumption of no interference is not really a fundamental piece of how we talk about counterfactual causality, but a by-product of a commitment to the use of a particular technology (simple comparisons of averages). We took a next step in our paper and realized that Fisher’s sharp null hypothesis implied a particular, and very simple, model of interference (a model of no interference). We then set out to see if we could write other, more substantively interesting models of interference. So, that is what we show in the paper: one can write down a substantive theoretical model of interference (and of the mechanism for an experimental effect to come to matter for the units in the study) and then this model can be understood as a generator of sharp null hypotheses, each of which could be tested using the same randomization inference tools that we have been studying for their clarity and validity previously.

R. Michael Alvarez: What are the applications for the approach you develop in your paper?

Jake Bowers: We are working on a couple of applications. In general, our approach is useful as a way to learn about substantive models of the mechanisms for the effects of experimental treatments.

For example, Bruce Desmarais, Mark Fredrickson, and I are working with Nahomi Ichino, Wayne Lee, and Simi Wang on how to design randomized experiments to learn about models of the propagation of treatments across a social network. If we think that an experimental intervention on some subset of Facebook users should spread in some certain manner, then we are hoping to have a general way to think about how to design that experiment (using our approach to learn about that propagation model, but also using some of the new developments in network-weighted average treatment effects that I referenced above). Our very early work suggests that, if treatment does propagate across a social network following a common infectious disease model, that you might prefer to assign relatively few units to direct intervention.

In another application, Nahomi Ichino, Mark Fredrickson, and I are using this approach to learn about agent-based models of the interaction of ethnicity and party strategies of voter registration fraud using a field experiment in Ghana. To improve our formal models, another collaborator, Chris Grady, is going to Ghana to do in-depth interviews with local party activists this fall.

R. Michael Alvarez: Political methodologists have made many contributions to the area of causal inference. If you had to recommend to a graduate student two or three things in this area that they might consider working on in the next year, what would they be?

Jake Bowers: About advice for graduate students: Here are some of the questions I would love to learn about.

How should we move from formal, equilibrium-oriented, theories of behavior to models of mechanisms of treatment effects that would allow us to test hypotheses and learn about theory from data? How can we take advantage of estimation-based procedures or procedures developed without specific focus on counterfactual causal inference if we want to make counterfactual causal inferences about models of interference? How should we reinterpret or use tools from spatial analysis like those developed by Rob Franzese and Jude Hayes or tools from network analysis like those developed by Mark Handcock to answer causal inference questions? How can we provide general advice about how to choose test-statistics to summarize the observable implications of these theoretical models? We know that the KS-test used in our article is pretty low-powered. And we know from Rosenbaum (Chap 2, 2002) that certain classes of test statistics have excellent properties in one-dimension, but I wonder about general properties of multi-parameter models and test statistics that can be sensitive to multi-way differences in distribution between experimental groups. How should we apply ideas from randomized studies to the observational world? What does adjustment for confounding/omitted variable bias (by matching or “controlling for” or weighting) mean in the context of social networks or spatial relations? How should we do and judge such adjustment? Would might what Rosenbaum-inspired sensitivity analysis or Manski-inspired bounds analysis might mean when we move away from testing one parameter or estimating one quantity?R. Michael Alvarez: You do a lot of work with software tool development and statistical computing. What are you working on now that you are most excited about?

Jake Bowers: I am working on two computationally oriented projects that I find very exciting. The first involves using machine learning/statistical learning for optimal covariance adjustment in experiments (with Mark Fredrickson and Ben Hansen). The second involves collecting thousands of hand-drawn maps on Google maps as GIS objects to learn about how people define and understand the places where they live in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States (with Cara Wong, Daniel Rubenson, Mark Fredrickson, Ashlea Rundlett, Jane Green, and Edward Fieldhouse).

When an experimental intervention has produced a difference in outcomes, comparisons of treated to control outcomes can sometimes fail to detect this effect, in part, because the outcomes themselves are naturally noisy in comparison to the strength of the treatment effect. We would like to reduce the noise that is unrelated to treatment (say, remove the noise related to background covariates, like education) without ever estimating a treatment effect (or testing a hypothesis about a treatment effect). So far, people shy away from using covariates for precision enhancement of this type because of every model in which they soak up noise with covariates is also a model in which they look at the p-value for their treatment effect. This project learns from the growing literature in machine learning (aka statistical learning) to turn specification of the covariance adjustment part of a statistical model over to an automated system focused on the control group only which thus bypasses concerns about data snooping and multiple p-values.

The second project involves using Google maps embedded in online surveys to capture hand-drawn maps representing how people respond when asked to draw the boundaries of their “local communities.” So far we have over 7000 such maps from a large survey of Canadians, and we plan to have data from this module carried on the British Election Study and the US Cooperative Congressional Election Study within the next year. We are using these maps and associated data to add to the “context/neighborhood effects” literature to learn how psychological understandings of place by individuals relates to Census measurements and also to individual level attitudes about inter-group relations and public goods provision.

Headline image credit: Abstract city and statistics. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Q&A with Jake Bowers, co-author of 2014 Miller Prize Paper appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Hunger Games and a dystopian Eurozone economyRestUK, international law, and the Scottish referendumLearning with body participation through motion-sensing technologies

Related StoriesThe Hunger Games and a dystopian Eurozone economyRestUK, international law, and the Scottish referendumLearning with body participation through motion-sensing technologies

Seven fun facts about the ukulele

The ukulele, a small four-stringed instrument of Portuguese origin, was patented in Hawaii in 1917, deriving its name from the Hawaiian word for “leaping flea.” Immigrants from the island of Madeira first brought to Hawaii a pair of Portuguese instruments in the late 1870s from which the ukuleles eventually developed. Trace back to the origins of the ukulele, follow its evolution and path to present-day popularity, and explore interesting facts about this instrument with Oxford Reference.

1. Developed from a four-string Madeiran instrument and built from Hawaiian koa wood, ukuleles were popular among the Hawaiian royalty in the late 19th century.

2. 1893’s World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago saw the first major performance of Hawaiian music with ukulele on the mainland.

3. By 1916, Hawaiian music became a national craze, and the ukulele was incorporated into popular American culture soon afterwards.

4. Singin’ In The Rain vocalist Cliff Edwards was also known as Ukulele Ike, and was one of the best known ukulele players during the height of the instrument’s popularity in the United States.

Cliff Edwards playing ukulele with phonograph, 1947. Photography from the William P. Gottlieb Collection. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Cliff Edwards playing ukulele with phonograph, 1947. Photography from the William P. Gottlieb Collection. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. 5. When its sales reached millions in the 1920s, the ukulele became an icon of the decade in the United States.

6. Ernest Ka’ai wrote the earliest known ukulele method in The Ukulele, A Hawaiian Guitar and How to Play It, 1906.

7. The highest paid entertainer and top box office attraction in Britain during the 1930s and 40s, George Fromby, popularized the ukulele in the United Kingdom.

Headline image credit: Ukuleles. Photo by Ian Ransley. CC BY 2.0 via design-dog Flickr.

The post Seven fun facts about the ukulele appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biographyThe lure of soundsOn the Town, flashpoint for racial distress

Related StoriesThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biographyThe lure of soundsOn the Town, flashpoint for racial distress

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers