Oxford University Press's Blog, page 759

September 25, 2014

The Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biography

September 2014 marks the tenth anniversary of the publication of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Over the next month a series of blog posts explore aspects of the Dictionary’s online evolution in the decade since 2004. In this post, Henry Summerson considers how new research in medieval biography is reflected in ODNB updates.

Today’s publication of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography’s September 2014 update—marking the Dictionary’s tenth anniversary—contains a chronological bombshell. The ODNB covers the history of Britons worldwide ‘from the earliest times’, a phrase which until now has meant since the fourth century BC, as represented by Pytheas, the Marseilles merchant whose account of the British Isles is the earliest known to survive. But a new ‘biography’ of the Red Lady of Paviland—whose incomplete skeleton was discovered in 1823 in Wales, and which today resides in Oxford’s Museum of Natural History—takes us back to distant prehistory. As the earliest known site of ceremonial human burial in western Europe, Paviland expands the Dictionary’s range by over 32,000 years.

The Red Lady’s is not the only ODNB biography pieced together from unidentified human remains (Lindow Man and the Sutton Hoo burial are others), while the new update also adds the fifteenth-century ‘Worcester Pilgrim’ whose skeleton and clothing are on display at the city’s cathedral. However, the Red Lady is the only one of these ‘historical bodies’ whose subject has changed sex—the bones having been found to be those of a pre-historical man, and not (as was thought when they were discovered), of a Roman woman.

The process of re-examination and re-interpretation which led to this discovery can serve as a paradigm for the development of the DNB, from its first edition (1885-1900) to its second (2004), and its ongoing programme of online updates. In the case of the Red Lady the moving force was in its broadest sense scientific. In this ‘he’ is not unique in the Dictionary. The bones of the East Frankish queen Eadgyth (d.946), discovered in 2008 provide another example of human remains giving rise to a recent biography. But changes in analysis have more often originated in more conventional forms of historical scholarship. Since 2004 these processes have extended the ODNB’s pre-1600 coverage by 300 men and women, so bringing the Dictionary’s complement for this period to more than 7000 individuals.

In part, these new biographies are an evolution of the Dictionary as it stood in 2004 as we broaden areas of coverage in the light of current scholarship. One example is the 100 new biographies of medieval bishops that, added to the ODNB’s existing selection, now provide a comprehensive survey of every member of the English episcopacy from the Conquest to the Reformation—a project further encouraged by the publication of new sources by the Canterbury and York Society and the Early English Episcopal Acta series.

Taken together these new biographies offer opportunities to explore the medieval church, with reference to incumbents’ background and education, the place of patronage networks, or the shifting influence of royal and papal authority. That William Alnwick (d.1449), ‘a peasant born of a low family’, could become bishop of Norwich and Lincoln is, for example, indicative of the growing complexity of later medieval episcopal administration and its need for talented men. A second ODNB project (still in progress) focuses on late-medieval monasticism. Again, some notable people have come to light, including the redoubtable Elizabeth Cressener, prioress of Dartford, who opposed even Thomas Cromwell with success.

Magna Carta, courtesy of the British Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Magna Carta, courtesy of the British Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Away from religious life, recent projects to augment the Dictionary’s medieval and early modern coverage have focused on new histories of philanthropy—with men like Thomas Alleyne, a Staffordshire clergyman whose name is preserved by three schools—and of royal courts and courtly life. Hence first-time biographies of Sir George Blage, whom Henry VIII used to address as ‘my pig’, and at a lower social level, John Skut, the tailor who made clothes for most of the king’s wives: ‘while Henry’s queens came and went, John Skut remained.’

Alongside these are many included for remarkable or interesting lives which illuminate the past in sometimes unexpected ways. At the lowest social level, such lives may have been very ordinary, but precisely because they were commonplace they were seldom recorded. Where a full biography is possible, figures of this kind are of considerable interest to historians. One such is Agnes Cowper, a Southwark ‘servant and vagrant’ in the years around 1600; attempts to discover who was responsible for her maintenance shed a fascinating light on a humble and precarious life, and an experience shared by thousands of late-Tudor Londoners. Such light falls only rarely, but the survival of sources, and the readiness of scholars to investigate them, have also led to recent biographies of the Roman officers and their wives at Vindolanda, based on the famous ‘tablets’ found at Chesterholm in Northumberland; the early fourteenth-century anchorite Christina Carpenter, who provoked outrage by leaving her cell (but later returned to it), and whose story has inspired a film, a play and a novel; and trumpeter John Blanke, whose fanfares enlivened the early Tudor court and whose portrait image is the only identifiable likeness of a black person in sixteenth-century British art.

While people like Blanke are included for their distinctiveness, most ODNB subjects can be related to the wider world of their contemporaries. A significant component of the Dictionary since 2004 has been an interest in recreating medieval and early modern networks and associations; they include the sixth-century bringers of Christianity to England, the companions of William I, and the enforcers of Magna Carta. Each establishes connections between historical figures, sets the latter in context, and charts how appreciations of these networks and their participants have developed over time—from the works of early chroniclers to contemporary historians. Indeed, in several instances, notably the Round Table knights or the ‘Merrie Men’, it is this (often imaginative) interpretation and recreation of Britain’s medieval past that is to the fore.

The importance of medieval afterlives returns us to the Red Lady of Paviland. His biography presents what can be known, or plausibly surmised, about its subject, alongside the ways in which his bodily remains (and the resulting life) have been interpreted by successive generations—each perceptibly influenced by the cultural as well as scholarly outlook of the day. Next year sees the 800th anniversary of the granting of Magna Carta, a centenary which can be confidently expected to bring further medieval subjects into Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. It is unlikely that the historians responsible will be unaffected by considerations of the long-term significance of the Charter. Nor, indeed, should they be—it is the interaction of past and present which does most to bring historical biography to life.

The post The Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biography appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Oxford DNB at 10: new research opportunities in the humanitiesWhose muse mews?How Georg Ludwig became George I

Related StoriesThe Oxford DNB at 10: new research opportunities in the humanitiesWhose muse mews?How Georg Ludwig became George I

September 24, 2014

A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1

Color words are among the most mysterious ones to a historian of language and culture, and brown is perhaps the most mysterious of them all. At first blush (and we will see that it can have a brownish tint), everything is clear. Brown is produced by mixing red, yellow, and black. Other authorities suggest: orange and black. In any case, it has two sides: dark (black) and bright (red or orange). This color name does not seem to occur in the New Testament, and that is why of all the Old Germanic languages only Gothic lacks it (in Gothic a sizable part of a fourth-century translation of the New Testament has been preserved). In the Old Testament, the word appears most rarely. Genesis XXX: 32, 35, and 40 describes the division of Laban’s cattle. According to Verse 35 from the Authorized Version, “…he removed that day the he goats that were ringstraked and spotted, and all the she goats that were speckled and spotted, and every one that had some white in it, and all the brown among the sheep, and gave them into the hand of his sons.” Those sheep were indeed brown, but the situation is not always so clear. For example, an Old English poet called waves brown, and brown is a common epithet attached to swords in early Germanic poetry. Were waves and swords really brown, like Laban’s sheep?

In Old Germanic languages, brown had the form brun, with a long vowel (that is, with the vowel of Modern Engl. boo), and we can be fairly certain that the ancient Indo-Europeans had the same hue in mind we do, because at least three unmistakably brown animals were called brown. One of them is the bear, also known as Bruin (the word is pure Dutch). People were afraid of pronouncing the terrible beast’s name and coined a euphemism (“the brown one”). When they said brown, the bear could no longer think that is was summoned and would not come. The other animal with a “brown” name is beaver. If bears and beavers were called “brown” and the biblical Laban had brown sheep, why then brown waves and brown swords? We’ll have to wait rather long for the answer: this blog is a serial.

Let us first look at etymology. Those who have read the relatively recent posts on gray may remember that that Germanic color name made its way into Romance languages. The same holds for brown (vide French brun and Italian brun). Later, as happened more than once, Old French brun returned to Middle English and reinforced the native word; compare also brunet(te), from French, with reference to people with chestnut-colored or black (!) hair. In the posts on gray, I mentioned two current explanations of why gray, brown, and some other color names enjoyed such popularity outside their country of origin. Allegedly, Germanic mercenaries brought them to the Romance-speaking territory with either the words for their horse breeds or for their shields. There must have been something special about both. The root of brown can also be seen in Engl. burnish. The suffix -ish was added to the root of Old French burnir, from brunir. “To make brown” acquired the meaning “polish (metal) by friction.” This returns us to the brown weapons of Old Germanic.

Abkaou, reçoit ses offrandes. 11e dynastie. Louvre Museum. Photo by Rama. CC BY-SA 2.0 FR via Wikimedia Commons.

Abkaou, reçoit ses offrandes. 11e dynastie. Louvre Museum. Photo by Rama. CC BY-SA 2.0 FR via Wikimedia Commons.The origin of bear and beaver from brown, though highly probable, is not absolutely assured, but the derivation of the Greek word phryne “toad” (stress on the first syllable) can hardly be put into question. Phryne looks like a perfect cognate of brown. (The famous hetaera Phryne is said to have received this nickname for her sallow skin, but other prostitutes were often called the same, and I have my own explanation of this fact; see below.) Toads, detested by some for all kinds of reasons, have occupied a conspicuous place in the superstitions of the whole world, beginning with at least the ancient Egyptian times. In Egypt, far from being shunned, they stood for fertility, and an amulet in the form of a toad supposedly replicated the uterus. Hequet was a goddess with the head of a frog.

Stories about frogs and toads are countless. One is especially famous. It is about a young man (prince) marrying a frog, which turns into a beautiful maiden. The Grimms knew a short and uninspiring version of this story (it is the opening one in their collection). In it the frog that insists on sleeping in the girl’s bed becomes a handsome prince, which is a variant of “Beauty and the Beast”; as a rule, in such tales the frog or the toad is a female. I would like to suggest, that the nickname Phryne had nothing to do with the hetaera’s skin. All other prostitutes who were called this could not have had the same tint. Since in the popular imagination toads and fertility went together and since Egyptian mythology and beliefs exercised a strong influence on the Greek mind, calling prostitutes toads would have made good sense.

Thus, as we can see, toads (brown creatures) were associated with things bad and good. On the one hand, they were feared for their supposed ugliness and identified with witches. On the other, they were venerated and thought to promote fertility. In that capacity, they frequently received votive offerings. From Egypt we should go to the British Isles, for whose sake I have told my story. As far as I can judge, no accepted etymology of brownie “imp” exists. The books at my disposal only say that brownies, benevolent imps, originated in Scotland and were brown. The earliest citations go back to the early seventeenth century. I have as little trust in brown brownies as in the brown-skinned Phryne among the Greeks. The name must have had magic connotations, but whether positive or negative is open to question. As time goes on, such creatures often change their attitude toward the houses they haunt. They can be friendly if treated well and hostile if offended. By contrast, brownies, chocolate cakes with nuts, are always brown and sweet (chocolate-colored, by definition).

My second example is literary. In Dickens’s novel Dombey and Son, Mr. Dombey’s little daughter Florence is abducted by an ugly old rag and bone vendor. When the girl asks the woman about her name, it is given to her as Mrs. Brown and amended to Good Mrs. Brown. “She was a very ugly old woman, with red rims round her eyes, and a mouth that mumbled and chattered of itself when she was not speaking.” This is how she introduced herself to Florence: “…don’t vex me. If you don’t, I tell you I won’t hurt you. But if you do, I’ll kill you. I could have killed you at any time—even if you was in your own bed at home.” I am sure somewhere in the immense literature on Dickens the folklore of Mrs. Brown was explained long ago. In any case, Dickens must have had a reason for calling the witch Mrs. Brown and adding ominously the ironic epithet good to the name, to reinforce the impression.

And here is a final flourish for today. I will be grateful for some reliable information on the origin of the last name Brown ~ Braune. Dictionaries say that the name goes back to the color of its bearers. I find this explanation puzzling. It is as though thousands of our neighbors were bears, beavers, and toads.

To be continued.

The post A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesKissing from a strictly etymological point of viewA wrapping rhapsodyPost 450, descriptive of how the Oxford Etymologist spent part of this past August

Related StoriesKissing from a strictly etymological point of viewA wrapping rhapsodyPost 450, descriptive of how the Oxford Etymologist spent part of this past August

Intergenerational perspectives on psychology, aging, and well-being

Why are people afraid to get old? Research shows that having a bad attitude toward aging at a young age is only detrimental to the young person’s health and well-being in the long-run. Contrary to common wisdom, our sense of well-being actually increases with our age–often even in the presence of illness or disability. Mindy Greenstein, PhD, and Jimmie Holland, MD, debunk the myth that growing older is something to fear in their new book Lighter as We Go: Virtues, Character Strengths, and Aging. In the following videos, Dr. Greenstein and Dr. Holland are joined by Holland’s granddaughter Madeline in a thought-provoking discussion about their different perspectives on aging in correlation to well-being.

The Relationship between Wisdom and Age

The Bridge between Older People and Younger Generations

On Fluctuations in Well-Being throughout Life

The Vintage Readers Book Club

Headline image credit: Cloud Sky over Brest. Photo by Luca Lorenzi. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Intergenerational perspectives on psychology, aging, and well-being appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy you should never trust a proThe truth about evidenceFacebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronouns

Related StoriesWhy you should never trust a proThe truth about evidenceFacebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronouns

The Hunger Games and a dystopian Eurozone economy

The following is an extract from ‘Europe’s Hunger Games: Income Distribution, Cost Competitiveness and Crisis‘, published in the Cambridge Journal of Economics. In this section, Servaas Storm and C.W.M. Naastepad are comparing The Hunger Games to Eurozone economies:

Dystopias are trending in contemporary popular culture. Novels and movies abound that deal with fictional societies within which humans, individually and collectively, have to cope with repressive, technologically powerful states that do not usually care for the well-being or safety of their citizens, but instead focus on their control and extortion. The latest resounding dystopian success is The Hunger Games—a box-office hit located in a nation known as Panem, which consists of 12 poor districts, starved for resources, under the absolute control of a wealthy centre called the Capitol. In the story, competitive struggle is carried to its brutal extreme, as poor young adults in a reality TV show must fight to death in an outdoor arena controlled by an authoritarian Gamemaker, until only one individual remains. The poverty and starvation, combined with terror, create an atmosphere of fear and helplessness that pre-empts any resistance based on hope for a better world.

We fear that part of the popularity of this science fiction action-drama, in Europe at least, lies in the fact that it has a real-life analogue: the Spectacle—in Debord’s (1967) meaning of the term—of the current ‘competitiveness game’ in which the Eurozone economies are fighting for their survival. Its Gamemaker is the European Central Bank (ECB), which—completely stuck to Berlin’s hard line that fiscal profligacy in combination with rigid, over-regulated labour markets has created a deep crisis of labour cost competitiveness—has been keeping the pressure on Eurozone countries so as to let them pay for their alleged fiscal sins. The ECB insists that there will be ‘no gain without pain’ and that the more one is prepared to suffer, the more one is expected to prosper later on.

The contestants in the game are the Eurozone members—each one trying to bootstrap its economy out of the throes of the most severe crisis in living memory. The audience judging each country’s performance is not made up of reality TV watchers but of financial (bond) markets and credit rating agencies, whose supposedly rational views can make or break any economy. The name of the game is boosting cost-competitiveness and exports—and its rules are carved into stone in March 2011 in a Euro Plus ‘Competitiveness Pact’ (Gros, 2011).

The Hunger Games, by Kendra Miller. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The Hunger Games, by Kendra Miller. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.Raising competitiveness here means reducing costs, and more specifically cutting labour costs, which means lowering the wage share by means of reducing employment protection, lowering minimum wages, raising retirement ages, lowering pensions and, last but not least, cutting real wages. Economic inequality, poverty and social exclusion will all initially increase, but don’t worry: structural reforms hurt in the beginning, but their negative effects will be offset over time by changes in ‘confidence,’ boosting spending and exports. But it will not work, and the damage done by austerity and structural reforms is enormous; sadly, most of it was and is avoidable. The wrong policies follow from ‘design faults’ built into the Euro project right from the start—the creation of an ‘independent’ European Central Bank being the biggest ‘fault’, as it precluded the necessary co-ordination of fiscal and monetary policy and disabled the central banking system from providing support to national governments (Arestis and Sawyer, 2011). But as Palma (2009) reminds us, it is wrong to think about these ‘faults’ as being caused by perpetual incompetence—the monetarist Euro project should instead be read as a purposeful ‘technology of power’ to transform capitalism into a rentiers’ paradise. This way, one can understand why policy makers persist in abandoning the unemployed.

The post The Hunger Games and a dystopian Eurozone economy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIncreasing income inequalityChina’s economic foesOut with the old?

Related StoriesIncreasing income inequalityChina’s economic foesOut with the old?

Atheism and feminism

At first glance atheism and feminism are two sides of the same coin.

After all, the most passionate criticism of patriarchy has come from religious (or formerly religious) female scholars. First-hand experience of male domination in such contexts has led many to translate their views into direct political activism. As a result, the fight for women’s rights has often been inseparable from the critique of organised religion.

For example, a nineteenth-century campaigner for civil rights, Ernestine Rose, began by rebelling against an arranged marriage at the tender age of 16, and then gradually added other injustices she witnessed during her travels around Europe and the United States to her list of causes.

Rose was born in a Jewish family, and her religious background certainly affected her subsequent life in two distinct ways. Judaism fostered an inquisitive and critical attitude to the world around her, while at the same time making her aware of the gender inequalities in her own and other religious traditions. She went to the United States in 1836 where she soon started to give public lectures on ending slavery, religious freedom and women’s rights. After one of such public appearance, she was described by the local paper as a ‘female Atheist … a thousand times below a prostitute’.

Negative publicity meant that Rose’s popularity grew significantly, although her speeches were met with such outrage that had to flee the more conservative towns. She continued to make appearances at women’s rights conventions across the United States, although her outspoken atheism caused unease to both men and women.

It did not, however, stop her from becoming the president of the National Women’s Rights Convention in 1854. She worked and made friends with other politically involved women of her time, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Sojourner Truth. Rose’s atheism was not exactly at the forefront of her struggle for justice but it implicitly informed her views and actions. For example, she blamed both organised religion and capitalism for the inferior status of women.

Flower offerings. By mckaysavage. CC-BY-2.0 via

Wikimedia Commons

Flower offerings. By mckaysavage. CC-BY-2.0 via

Wikimedia Commons

Well over a century later the number and variety of female atheists are growing. Nonetheless, atheism remains a male-dominated affair. Data collected by the Atheist Alliance International (2011) show that in Britain, women account for 21.6% of atheists (as opposed to 77.9% men). In the United States men make up 70% of Americans who identify as atheist. In Poland, 32% of atheists are female, and similarly in Australia it is 31.5% .

On rare occasions when female atheists appear in the media, they are invariably feminist activists. This is hardly a problem but unfortunately it leads to a conflation of feminist activism and atheism, which in turn makes the ‘everyday’ female atheists invisible. It also encourages stereotyping of the most simplistic sort whereby the feminist stance becomes the primary focus while the atheism is treated as an add-on. But the two do not necessarily go together, and the women may not see them as equally central to their lives.

As significant progress has been made with regard to gender equality, and traditional religion has largely lost its influence over women’s lives, the connection between atheism and feminism has become more complicated.

My current project involves talking to self-identified female atheists from Britain, Poland, Australia, and the United States. Times may have changed but the core values held by these women closely resemble those espoused by Ernestine Rose, and the passion with which they speak about global and local injustice indicates a very particular atheism, far removed from the detached, rational and scientific front presented by some of the famous (male) faces of the atheist movement.

Two themes have emerged. One is the ease with which an atheist identity can be combined with ethics of care and altruism (thus demonstrating the compatibility of non-belief with goodness). Two is discrimination against women within the atheist movement.

Ernestine Rose. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Ernestine Rose. Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsThe latter reminds me of a paper I once heard at a Gender and Religion conference in Tel Aviv. The presenter compared two synagogues in Paris: a progressive and liberal one which had a female rabbi, and a conservative one which preserved the strict division of gender roles. The paradox lay in the fact that more instances of discrimination against women, including overt sexism and sexual harassment, were reported among the members of the liberal synagogue.

Clearly, nobody looks for sexism in a place defined as non-sexist. A similar paradox applies to atheists. An activist in the atheist community told me that she received the worst abuse from her fellow (male) atheists, not religious hardliners.

One of the explanations for women’s greater religiosity is their need for community, emotional support, and a guiding light in life. Conservative religions perform this role very well, but so do alternative spiritualities where traditional religion is in decline and women suffer from emotional, not material, deprivation.

Atheism does the same for my interviewees. The task of a sociologist is to de-familiarise the familiar and to find the unexpected in the everyday through the grace of serendipity. Female atheists find empowerment and means of expression in their atheism, while at the same time defining it for themselves, rather than relying on the prominent male figures in the atheist community. While on the surface they lack the structure present in religious communities of women, they create networks of support with other women where atheism is but one, albeit a crucial one, feature of their self-definition.

The openness provides a more inclusive and flexible starting point for coming together and fighting for equality and justice, not necessarily on the barricades. Activism is inspiring but values spread more effectively it is in the everyday, mundane activities. In this sense, deeply religious and deeply atheist women have a lot in common. Both find fulfilment and joy in forging connections with other people and creating a safe haven for themselves and those close to them.

The female atheist activists all say the same thing: ‘I do it because I want to help’. A modest statement which can achieve a lot in the long run.

The post Atheism and feminism appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFrom “Checkers” to WatergateCaught in Satan’s StormCatesby’s American Dream: religious persecution in Elizabethan England

Related StoriesFrom “Checkers” to WatergateCaught in Satan’s StormCatesby’s American Dream: religious persecution in Elizabethan England

September 23, 2014

The lure of sounds

There’s something about the idea of ‘original pronunciation’ (OP) that gets the pulse racing. I’ve been amazed by the public interest shown in this unusual application of a little-known branch of linguistics — historical phonology, a subject that explores how the sounds of a language change over time. I little expected, when I was approached by Shakespeare’s Globe in 2004 to help them mount a production of Romeo and Juliet in OP, that ten years on the approach would become a thriving linguistic industry. Nor could I have predicted that a short documentary recording about OP for the Open University (which I made with actor son Ben in 2011) would for no apparent reason go viral towards the end of 2013, with 1.5 million hits in recent months.

A dozen Shakespeare plays have now been produced in original pronunciation, including A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Kansas University in 2010 and Hamlet at the University of Nevada (Reno) in 2011. This year a group from the University of Texas (Houston) brought an OP production of Julius Caesar to the Edinburgh Fringe. Next January, Ben Crystal and his OP ensemble are presenting Pericles in Stockholm as part of an Interplay series along with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. More productions are in the pipeline.

But it isn’t just Shakespeare. The interest in him tops the list, but it is a long list, in which the work of any dramatist from the period can be treated in this way. And not just drama. Poems and prose too. My recording of the Sonnets is available on the website associated with the book Pronouncing Shakespeare. An OP recording by Ben of one of John Donne’s long sermons can now be heard as part of the Virtual St Paul’s Cross project.

Donne takes us forward in time to the 1620s. Going backwards in time, the British Library wanted an original pronunciation recording of William Tyndale to accompany the publication of its facsimile of the Tyndale Gospels. They chose the Matthew Gospel, and I recorded this for them in 2013. That takes us back to 1525. There are earlier recordings in the BL archive, made for the Evolving English winter exhibition in 2011-12, including extracts from Beowulf, Chaucer, Caxton, and Paston. The British Library also commissioned a CD of Shakespeare extracts from Ben and his ensemble: Shakespeare’s Original Pronunciation.

William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116 (© Library of the University of California, Los Angeles).

William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116 (© Library of the University of California, Los Angeles). But the interest extends well beyond literature. Notably present in the talkback sessions after the first original pronunciation productions at the Globe were people interested in early music. And since then there have been many explorations into the kind of pronunciation used by Purcell (late 17th century), Dowland, and other composers. As with their literary counterparts, musicologists have been struck by the fact that so many of the rhymes in songs, madrigals, and operatic texts simply don’t work in modern English, and they want to hear them as they would have been. They note the way many of the vowels and consonants would have had different values in those days, and they want to explore how the texts would sound with those old values articulated. The result is a very different auditory experience, and — by all accounts — an exciting one.

Finally there are the heritage people. It’s all well and good establishing a historical centre where an old period is recreated, and people dress up in old clothes and walk around — but how should they speak? The occasional ‘verily’ and ‘forsooth’ isn’t enough. Here too we see an interest in recreating styles of speech that would have been used in those days.

Add all these constituencies together and you can see why the original pronunciation experiment has become something of an OP movement, with more and more people wanting to learn about OP, to hear it in practice, and to explore its application in texts that so far have received no study. Every new text brings to light something new — such as a previously unnoticed pun, or a fresh way of speaking a line. At university level, people are beginning to write dissertations on the subject. Ben, as I write, is exploring ways for his ensemble to cope with new OP commitments. There’s plenty to do. With only a dozen Shakespeare plays explored so far, that leaves a couple of dozen more awaiting investigation.

The consequence is an urgent need to provide materials to help people take original pronunciation activities forward. Paul Meier already has some tutorial material on his website, and his Dream production is available both as an audio recording and on a DVD. Several articles have now been written answering the usual questions people ask (such as ‘how do you know’?). And I am hard at work on an OP Shakespeare dictionary, which will enable people to make transcripts for themselves. I have paused, in the middle of letter N, to write this post. But with luck and a good following wind, I should have it finished in time for the great anniversary in 2016. And it will be published, of course, by Oxford University Press.

The post The lure of sounds appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy you should never trust a proPeace treaties that changed the worldIs Arabic really a single language?

Related StoriesWhy you should never trust a proPeace treaties that changed the worldIs Arabic really a single language?

From “Checkers” to Watergate

Forty years ago, President Richard M. Nixon faced certain impeachment by the Congress for the Watergate scandal. He resigned the presidency, expressing a sort of conditional regret:

I regret deeply any injuries that may have been done in the course of the events that led to this decision. I would say only that if some of my judgments were wrong, and some were wrong, they were made in what I believed at the time to be the best interest of the Nation.

Nixon is not apologizing here as much as offering what sociologist Erving Goffman calls an account—a verbal reframing of his actions aimed at reducing their offensiveness. Nixon treats himself as a victim of his own mistakes and treats his mistakes as managerial, not criminal. His language is loaded with such words as “any,” “may,” “would,” and “if,” among others and circumlocutions likes “in the course of the events that led to this decision” and “what I believed at the time to be the best interest of the Nation.” Nixon offers regret, but there is no unconditional apology, and there never was.

I sometimes wonder how Nixon’s attitudes toward Watergate and his resignation were shaped by the 1952 presidential campaign, and the events that led to his so-called “Checkers” speech.

It was the home stretch of the 1952 campaign, in which the Republican ticket of Dwight Eisenhower and then-Senator Nixon were pitted against Democrats Adlai Stevenson II and John J. Sparkman to succeed President Harry Truman. Truman’s popularity was at a low point and Eisenhower and Nixon were optimistic about their chances. Then, in mid-September, the press began reporting stories of a secret expense fund established in 1950 by Nixon supporters. The New York Post offered the sensational headline that “Secret Rich Men’s Trust Fund Keeps Nixon in Style Far Beyond His Salary.” As the story developed, many Democrats (and less publicly some Republicans) called for Nixon to be dropped from the ticket. News editorials disapproved of Nixon’s actions two-to-one. Even the Washington Post, which had endorsed the Republican ticket, called for Nixon to withdraw from the race.

The issue took some of the optimism out of the Eisenhower campaign. Eisenhower defended his Vice President publicly, but also promised that there would be a full reporting of the facts by independent auditors. The 39-year-old Nixon offered his account in a half-hour television address broadcast from the El Capitan Theatre in Hollywood, on 23 September 1952.

“I want to tell you my side of the case,” he began, and in a speech that ran just over 4,500 words, Nixon used a series of rhetorical questions guide his audience through his version of events. He used the strategy that rhetoricians called differentiation by claiming that the fund issue was not what it seemed to be. Nixon said that there was no moral wrong because none of the money—about $18,000—was for Senatorial expenses and that none of the contributors receive special favors. He asserted his own good character by explaining why he needed the money: because he was not a rich man and he didn’t feel the taxpayers should pay his expenses.

Nixon bolstered his character further with his biography—explaining his modest background and finances, giving details down to the amount of his life insurance, mortgages, and material of his wife’s coat: not mink but “a respectable Republican cloth coat,” adding that “And I always tell her that she’d look good in anything.”

He added another rhetorical turn in the second half of his speech: “Why do I feel so deeply? Why do I feel that in spite of the smears, the misunderstandings, the necessity for a man to come up here and bare his soul as I have?” Nixon’s answer was “Because, you see, I love my country. And I think my country is in danger.” Here Nixon implies that he is motivated by a greater good and he pivots to an attack on his political opponents and his avowal that Eisenhower was “the man that can clean up the mess in Washington.”

The speech was the first ever use of television by a national candidate to speak directly to the nation and to defend himself against accusations of wrong-doing. And the public was impressed. For many, the most memorable part was when Nixon told the viewers about a black and white cocker spaniel puppy that a supporter from Texas had given his daughters. One of them named it Checkers, and Nixon defiantly asserted that, “regardless of what they say about it, we’re gonna keep it.” The speech thus became known as “The Checkers Speech.”

Nixon finished with a call to action, asking his listeners to write to the Republican National Committee to show their support. His broadcast was seen by an estimated 60 million viewers, and letters and telegrams to the Republican National Committee were overwhelmingly supportive. Eisenhower kept him on the ticket and a few weeks later the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket carried the day with over 55% of the popular vote and 442 electoral votes.

Nixon accomplished three key verbal self-defense strategies in the “Checkers” speech. He argued that the fund was not what it seemed to be. He argued that he was a good steward of public funds and exposed his personal finances. He implied that he was serving a higher good because he supported General Eisenhower and opposed Communism.

But by 1974, things were different. Nixon was in trouble again, much worse trouble of his own making, and there was no “Checkers” speech, no way reframing his situation that would save his presidency. He resigned but he never apologized. Three years after resigning, in interviews with journalist David Frost, Nixon was unequivocally defiant:

When I resigned, people didn’t think it was enough to admit mistakes; fine. If they want me to get down and grovel on the floor, no. Never. Because I don’t believe I should.

Perhaps he was thinking about the “Checkers” speech.

Headline image credit: President Richard Nixon delivers remarks to the White House staff on his final day in office. From left to right are David Eisenhower, Julie Nixon Eisenhower, the president, First Lady Pat Nixon, Tricia Nixon Cox, and Ed Cox. 9 August 1974. White House photo, Courtesy Richard Nixon Presidential Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post From “Checkers” to Watergate appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFacebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronounsThe lure of soundsCaught in Satan’s Storm

Related StoriesFacebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronounsThe lure of soundsCaught in Satan’s Storm

On the Town, flashpoint for racial distress

When the first production of On the Town in 1944 featured the Japanese American ballerina Sono Osato as its star, as part of a cast that also included whites and blacks, it aimed for a realistic depiction of the diversity among US citizens during World War II. It did so at a time when African Americans were expressing affinity with Nisei – that is, with second-generation children of Japanese nationals who had immigrated to other countries. The two communities shared the struggle of discrimination by the majority culture.

In 1942, the Office of War Information conducted a survey in Harlem, trying to gain an African-American perspective on the war, and opinions about the Japanese emerged in the process. Many Harlemites communicated a feeling that “these Japanese are colored people.” That quotation comes from a letter written by William Pickens, an African-American journalist who worked for the US Department of Treasury during World War II. When asked “Would you be better off if America or the Axis won the war?” most blacks in the survey stated they “would be treated either the same or better under Japanese rule, although a large majority responded that conditions would be worse under the Germans.”

Yet relationships between these two marginalized communities were not always easy, and On the Town became a flash point for racial distress. A striking case appeared in the memoir Long Old Road (Trident Press, 1965), written by Horace R. Cayton, Jr. An African American sociologist from Chicago, Cayton attended On the Town soon after he heard about the bombing of Hiroshima, which occurred on 6 August 1945. He articulated a shared mission between Nisei and African Americans, yet he did so with considerable agitation. “Our seats were good, and the theater was cool after the heat of New York,” wrote Cayton. He responded positively to the opening number, “New York, New York,” then launched into an assessment of the racial and political complexities posed by Osato’s appearance on stage at that particular moment in time. He perceived her as racially accommodating.

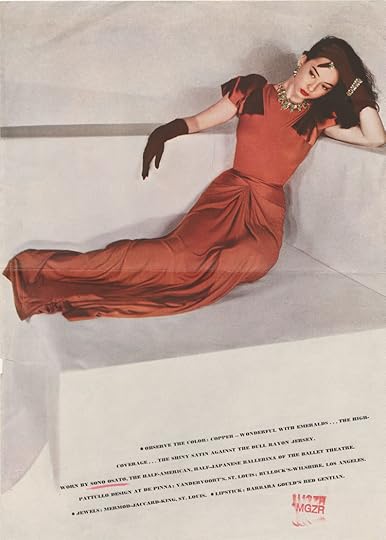

Sono Osato modeling a dress by Pattullo Modes, early 1940s. Dance Clipping Files, New York Public Library at Lincoln Center, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Sono Osato modeling a dress by Pattullo Modes, early 1940s. Dance Clipping Files, New York Public Library at Lincoln Center, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. “It was a catchy tune with cute lyrics, but when the beautiful Sono Osato, who is of Japanese descent, appeared and frolicked with the American sailors, I was filled with anger and disgust,” wrote Cayton. “I care more about your people than you do, I thought, as I sat through the rest of the first act looking at the floor and wondering how soon I could escape to the bar next door.”

Cayton’s “anger and disgust” came from watching Osato engage directly and uncritically with white actors playing the role of sailors. At intermission, Cayton’s wife June, who was white, said to him: “This is the first good musical I’ve seen in years. Isn’t Sono Osato wonderful?” Cayton then recounted a tense conversation between the two of them:

“If I were half-Japanese I wouldn’t be dancing with three American sailors at a time like this,” I [Cayton] commented sourly.

“Why shouldn’t she? She’s as America as you or I.” June began to warm to her subject. “She was born in this country. She’s one hundred per cent American, doesn’t even understand Japanese.”

[Cayton replied:] ‘She’s a Jap, I’m a nigger, and you’re a white girl. Let none of us forget what we are.”

Cayton’s outburst comes across as a racial polemic. But there was deep complexity to his reaction, as he expressed solidarity with other non-white races as they confronted the hegemonic power of Caucasians. Even though his language is disturbing, it is extraordinarily frank, acknowledging the era’s venomous racism against the Japanese and the degree to which African Americans felt themselves to be backed against a wall during World War II. Cayton continued:

“I’m torn a dozen ways. I didn’t want the Japanese to win; after all, I am an American. But the mighty white man was being humiliated, and by the little yellow bastards he had nothing but contempt for. It gave me a sense of satisfaction, a feeling that white wasn’t always right, not always able to enforce its will on everyone who was colored. All those fine white liberals rejoicing because we dropped a bomb killing or maiming seventy-eight thousand helpless civilians. Why couldn’t we have dropped it on the Germans—because they were white? No, save it for the yellow bastards.”

Those multi-layered thoughts were unleashed by watching Sono Osato on stage, dancing an identity that was intended to portray her as “All-American” yet could not avoid the realities of her mixed-race heritage at a harrowing historical moment.

Headline Image: Sono Osato modeling a dress by Pattullo Modes, early 1940s. Dance Clipping Files, New York Public Library at Lincoln Center, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

The post On the Town, flashpoint for racial distress appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn the Town and the long march for civil rights in performanceThe teenage exploits of a future celebrityEchoes of Billie Holiday in Fancy Free

Related StoriesOn the Town and the long march for civil rights in performanceThe teenage exploits of a future celebrityEchoes of Billie Holiday in Fancy Free

Facebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronouns

The death rattle of the gender binary has been ringing for decades now, leaving us to wonder when it will take its last gasp. In this third decade of third wave feminism and the queer critique, dismantling the binary remains a critical task in the gender revolution. Language is among the most socially pervasive tools through which culture is negotiated, but in a language like English, with its minimal linguistic marking of gender, it can be difficult to find concrete signs that linguistic structures are changing to reflect new ways of thinking about the gender binary rather than simply repackaging old ideas.

Sign from Genderblur at Twin Cities Pride 2003. Photo by Transguyjay. CC BY-NC 2.0 Why you should never trust a pro

Sign from Genderblur at Twin Cities Pride 2003. Photo by Transguyjay. CC BY-NC 2.0 Why you should never trust a pro

September 22, 2014

Caught in Satan’s Storm

On 22 September 1692 eight more victims of the Salem witch trials were executed on Gallows Hill. After watching the executions of Martha Cory, Margaret Scott, Mary Easty, Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Willmott Redd, Samuel Wardwell, and Mary Parker, Salem’s junior minister Nicholas Noyes exclaimed “What a sad thing to see eight firebrands of hell hanging there.” These would be the last of the executions, for the trials were facing increasing opposition amid a growing dissatisfaction with the political and spiritual leadership of the colony. Symbolic of that displeasure, less than two months later Noyes’s cousin, Sarah Noyes Hale, the wife of Beverly’s Reverend John Hale, would stand accused of witchcraft.

The Court of Oyer and Terminer, created by Governor Sir William Phips to deal with the witchcraft crisis, increasingly mimicked the arbitrary rule of the former governor Sir Edmond Andros and his hated Dominion of New England. Andros restricted rights and controlled the legal system through his appointment of judges, officials and “packed and picked” juries that did his bidding. In 1687 when several Essex County towns rose up in a tax revolt, protesting what they saw as Andros’s arbitrary and illegal tax law, Sir Edmond acted quickly to try and convict the leaders before a specially established Court of Oyer and Terminer. One of the judges on that panel was William Stoughton, a former minister.

Now five years later, under a new government and royal charter that had supposedly restored English liberties to Massachusetts, William Stoughton headed another Court of Oyer and Terminer that was again making quick and arbitrary decisions. This time people were losing their lives. In a two week session in early September, the court heard 15 cases and convicted 15 people of witchcraft. It was a rush to judgment, especially when the evidence was not as strong as in earlier prosecutions. Judges increasingly relied on dubious spectral evidence, and many observers must have been taken aback by the treatment of Giles Cory. He had been pressed to death on 19 September for standing mute when asked if he would accept a trial by jury. Worse, no one who confessed to being a witch had been executed – with the exception of Samuel Wardwell, who recanted his confession. Only those who refused to confess met death.

The house built for Reverend John and Sarah Hale in 1694, in Beverly, Massachusetts. Today it is operated as a museum by the Beverly Historical Society. Photo by Emerson W. Baker.

The house built for Reverend John and Sarah Hale in 1694, in Beverly, Massachusetts. Today it is operated as a museum by the Beverly Historical Society. Photo by Emerson W. Baker.The trials were but one failure of a weak government that continued to mismanage a war that had damaged the colony’s economy and threatened its very existence. The conflict against the French Catholics of Canada and their Native allies was also symbolic of the ongoing spiritual struggle in Massachusetts. Religious and political leaders had long called for a campaign for moral reformation to end the perceived decline of Puritan faith. The many accusations of witchcraft against the religious and political elite and their families show the extreme level of discontent at the failure of these policy makers.

A total of 20 people (11%) of the 172 formally accused or informally cried out on for witchcraft in 1692 were ministers or their close relatives. The number grows to 50 if one includes extended kin and in-laws of ministers – fully 30% of the people accused in 1692. In all, five ministers, four minister’s wives, three daughters, a son, two brothers and five grandchildren of ministers were cried out upon. Warrants were issued for only five of the twenty, and only two – George Burroughs and Abigail Dane Faulkner (daughter of Andover’s Reverend Francis Dane) would face the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

Burrough’s story is well known but historians have given little attention to Samuel Willard, Francis Dane, John Busse and Jeremiah Shepard, for none were ever formally charged. But they form an important part of an overlooked pattern of accusations against ministers and their families. Virtually all of the ministers who were accused or had family accused preached in New England churches that had accepted the Halfway Covenant – a controversial compromise that conservatives saw as a threat to Puritan orthodoxy.

These ministerial families were allied to each other by marriage, as can be seen in the example of Sarah Noyes Hale who was related to eight ministers. Her brother James would later be one of the seven ministers who founded Yale University. These families also married into the leading political families of the colony, so the accusations were a critique of the political and military leadership as well, including the witchcraft judges. And, the accusations went to the very top. Both Lady Mary Spencer Phips and Maria Cotton Mather were cried out upon. Clearly they served as stand-ins for their husbands – Governor Phips and his chief confidante, Reverend Increase Mather.

Maria Mather was the lynchpin connecting the two most important families of Puritan divines in Massachusetts. Her husband Increase was the President of Harvard College and the son of the prominent Reverend Richard Mather, while her father John Cotton was perhaps the leading Puritan theologian to join the Great Migration. Maria was also the sister of two ministers, sister-in-law of four more, and mother of Reverends Cotton and Samuel Mather. Increase and Cotton were both longstanding advocates of the Halfway Covenant but their conservative North Church had refused to accept it. During the trials, the Mathers were in the final stages of a campaign to get the North Church to adopt the Halfway Covenant. One of the few stalwart church members who stood in the way was Oyer and Terminer Judge John Richards.

The executions of 22 September were clearly the last straw for many observers of the witch trials. They generated opposition to the proceedings and the government, as well as accusations against the colony’s elite. It is notable that soon after his wife was cried out upon, Sir William Phips finally brought the Court of Oyer and Terminer to an end.

Headline image credit: Photo courtesy of Emerson “Tad” Baker.

The post Caught in Satan’s Storm appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGeorge Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witchA visual history of the RooseveltsThe impact of law on families

Related StoriesGeorge Burroughs: Salem’s perfect witchA visual history of the RooseveltsThe impact of law on families

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers