Oxford University Press's Blog, page 756

October 3, 2014

The power of oral history as a history-making practice

This week, we have a special podcast with managing editor Troy Reeves and Oral History Review 41.2 contributor Amy Starecheski. Her article, “Squatting History: The Power of Oral History as a History-Making Practice,” explores the ways in which an in intergenerational group of activists have used oral history to pass on knowledge through public discussions about the past. In the podcast, Starecheski discusses her motivation for the project and her involvement in the upcoming Annual Meeting of the Oral History Association. Check out the podcast below.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/ohr_starecheski_podcast_workingcopy.mp3

https://soundcloud.com/oral-history-r...

You can learn more about the Annual Meeting of the Oral History Association in the Meeting Program. If you have any trouble playing the podcast, you can download the mp3.

Headline image credit: Courtesy of Amy Starecheski.

The post The power of oral history as a history-making practice appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe power of oral history as a history-making practice - EnclosureSchizophrenia and oral historySo Long, Farewell

Related StoriesThe power of oral history as a history-making practice - EnclosureSchizophrenia and oral historySo Long, Farewell

A Halloween horror story : What was it?

We’re getting ready for Halloween this month by reading the classic horror stories that set the stage for the creepy movies and books we love today. Check in every Friday this October as we tell Fitz-James O’Brien’s tale of an unusual entity in What Was It?, a story from the spine-tingling collection of works in Horror Stories: Classic Tales from Hoffmann to Hodgson, edited by Darryl Jones.

It is, I confess, with considerable diffidence that I approach the strange narrative which I am about to relate. The events which I purpose detailing are of so extraordinary a character that I am quite prepared to meet with an unusual amount of incredulity and scorn. I accept all such beforehand. I have, I trust, the literary courage to face unbelief. I have, after mature consideration, resolved to narrate, in as simple and straightforward a manner as I can compass, some facts that passed under my observation, in the month of July last, and which, in the annals of the mysteries of physical science, are wholly unparalleled.

I live at No. — Twenty-sixth Street, in New York. The house is in some respects a curious one. It has enjoyed for the last two years the reputation of being haunted. It is a large and stately residence, surrounded by what was once a garden, but which is now only a green enclosure used for bleaching clothes. The dry basin of what has been a fountain, and a few fruit-trees ragged and unpruned, indicate that this spot in past days was a pleasant, shady retreat, filled with fruits and flowers and the sweet murmur of waters.

The house is very spacious. A hall of noble size leads to a large spiral staircase winding through its centre, while the various apartments are of imposing dimensions. It was built some fifteen or twenty years since by Mr A——, the well-known New York merchant, who five years ago threw the commercial world into convulsions by a stupendous bank fraud. Mr A——, as everyone knows, escaped to Europe, and died not long after, of a broken heart. Almost immediately after the news of his decease reached this country and was verified, the report spread in Twenty-sixth Street that No. — was haunted. Legal measures had dispossessed the widow of its former owner, and it was inhabited merely by a care-taker and his wife, placed there by the house-agent into whose hands it had passed for purposes of renting or sale. These people declared that they were troubled with unnatural noises. Doors were opened without any visible agency. The remnants of furniture scattered through the various rooms were, during the night, piled one upon the other by unknown hands. Invisible feet passed up and down the stairs in broad daylight, accompanied by the rustle of unseen silk dresses, and the gliding of viewless hands along the massive balusters. The care-taker and his wife declared they would live there no longer. The house-agent laughed, dismissed them, and put others in their place. The noises and supernatural manifestations continued. The neighborhood caught up the story, and the house remained untenanted for three years. Several persons negotiated for it; but, somehow, always before the bargain was closed they heard the unpleasant rumors and declined to treat any further.

It was in this state of things that my landlady, who at that time kept a boarding-house in Bleecker Street, and who wished to move further up town, conceived the bold idea of renting No. — Twenty-sixth Street. Happening to have in her house rather a plucky and philosophical set of boarders, she laid her scheme before us, stating candidly everything she had heard respecting the ghostly qualities of the establishment to which she wished to remove us. With the exception of two timid persons,—a sea-captain and a returned Californian, who immediately gave notice that they would leave,—all of Mrs Moffat’s guests declared that they would accompany her in her chivalric incursion into the abode of spirits.

Our removal was effected in the month of May, and we were charmed with our new residence. The portion of Twenty-sixth Street where our house is situated, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, is one of the pleasantest localities in New York. The gardens back of the houses, running down nearly to the Hudson, form, in the summer time, a perfect avenue of verdure. The air is pure and invigorating, sweeping, as it does, straight across the river from the Weehawken heights, and even the ragged garden which surrounded the house, although displaying on washing days rather too much clothes-line, still gave us a piece of greensward to look at, and a cool retreat in the summer evenings, where we smoked our cigars in the dusk, and watched the fire-flies flashing their dark-lanterns in the long grass.

Of course we had no sooner established ourselves at No. — than we began to expect the ghosts. We absolutely awaited their advent with eagerness. Our dinner conversation was supernatural. One of the boarders, who had purchased Mrs Crowe’s ‘Night Side of Nature’ for his own private delectation, was regarded as a public enemy by the entire household for not having bought twenty copies. The man led a life of supreme wretchedness while he was reading this volume.

A system of espionage was established, of which he was the victim. If he incautiously laid the book down for an instant and left the room, it was immediately seized and read aloud in secret places to a select few. I found myself a person of immense importance, it having leaked out that I was tolerably well versed in the history of supernaturalism, and had once written a story the foundation of which was a ghost. If a table or a wainscot panel happened to warp when we were assembled in the large drawing-room, there was an instant silence, and everyone was prepared for an immediate clanking of chains and a spectral form.

After a month of psychological excitement, it was with the utmost dissatisfaction that we were forced to acknowledge that nothing in the remotest degree approaching the supernatural had manifested itself. Once the black butler asseverated that his candle had been blown out by some invisible agency while he was undressing himself for the night; but as I had more than once discovered this colored gentleman in a condition when one candle must have appeared to him like two, I thought it possible that, by going a step further in his potations, he might have reversed this phenomenon, and seen no candle at all where he ought to have beheld one.

Things were in this state when an incident took place so awful and inexplicable in its character that my reason fairly reels at the bare memory of the occurrence.

Check back next Friday, 10 October, as the events of the narrator’s night unfolds.

Featured image: Hotel Meade by Nomadic Lass. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A Halloween horror story : What was it? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“There is no escape.” Horace Walpole and the terrifying rise of the GothicAchieving patient safety by supervising residentsAre we alone in the Universe?

Related Stories“There is no escape.” Horace Walpole and the terrifying rise of the GothicAchieving patient safety by supervising residentsAre we alone in the Universe?

“There is no escape.” Horace Walpole and the terrifying rise of the Gothic

This year is the 250th anniversary of Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, first published on Christmas Eve 1764 as a seasonal ghost story. The Castle of Otranto is often dubbed the “first Gothic novel” due to Walpole describing it as a “Gothic story,” but for him the Gothic meant very different things from what it might do today. While the Gothic was certainly associated with the supernatural, it was predominantly a theory of English progress rooted in Anglo-Saxon and medieval history — effectively the cultural wing of parliamentarian politics and Protestant theology. The genre of the “Gothic novel,” with all its dire associations of uncanny horror, would not come into being for at least another century. Instead, the writing that followed in the wake of Otranto was known as the German School, the ‘Terrorist System of Writing’, or even hobgobliana.

Reading Otranto today, however, it is almost impossible to forget what 250 years of Gothickry have bequeathed to our culture in literature, architecture, film, music, and fashion: everything from the great Gothic Revival design of the Palace of Westminster to none-more-black clothes for sale on Camden Town High Street and the eerie music of Nick Cave, Jordan Reyne, and Fields of the Nephilim.

And the cinema has been instrumental in spreading this unholy word. Despite being rooted in the history of the barbarian tribes who sacked Rome and the thousand-year epoch of the Dark Ages, the Gothic was also a state-of-the-art movement. Technology drove the Gothic dream, enabling, for instance, the towering spires and colossal naves of medieval cathedrals, or enlisting in nineteenth-century art and literature the latest scientific developments in anatomy and galvanism (Frankenstein), the circulation of the blood and infection (The Vampyre), or drug use and psychology (Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde).

The moving image on the cinema screen therefore had an immediate and compelling appeal. The very experience of cinema was phantasmagoric — kaleidoscopic images projected in a darkened room, accompanied by often wild, expressionist music. The hallucinatory visions of Henry Fuseli and Gustave Doré arose and, like revenants, came to life.

The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli, 1781. Public Domain via Wikiart.

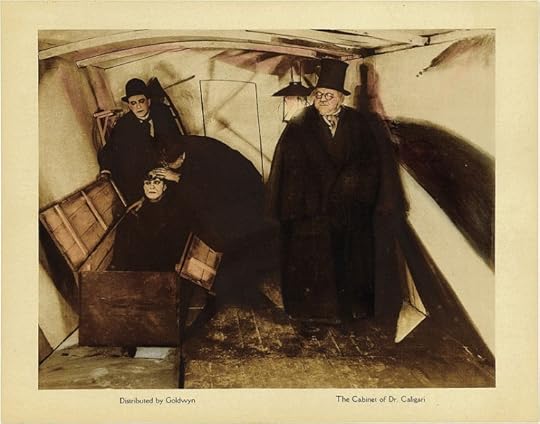

The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli, 1781. Public Domain via Wikiart.Camera tricks, special effects, fantastical scenery, and monstrous figures combined in a new visual style, most notably in Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Terror (1922). Murnau’s Nosferatu, the first vampire film, fed parasitically on Bram Stoker’s Dracula; it was rumored that Max Schreck, who played the nightmarish Count Orlok, was indeed a vampire himself. The horror film had arrived.

Cabinet of Dr Caligari Lobby Card (1920). Goldwyn Distributing Company. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Cabinet of Dr Caligari Lobby Card (1920). Goldwyn Distributing Company. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Mid-century Hollywood movie stars such as Bela Lugosi, who first played Dracula in 1931, and Boris Karloff, who played Frankenstein’s monster in the same year, made these roles iconic. Lugosi played Dracula as a baleful East European, deliberately melodramatic; Karloff was menacing in a different way: mute, brutal, and alien. Both embodied the threat of the “other”: communist Russia, as conjured up by the cinema. Frankenstein’s monster is animated by the new cinematic energy of electricity and light, while in Dracula the Count’s life and death are endlessly replayed on the screen in an immortal and diabolical loop.

It was in Britain, however, that horror films really took the cinema-going public by the throat. Britain was made for the Gothic cinema: British film-makers such as Hammer House of Horror could draw on the nation’s rich literary heritage, its crumbling ecclesiastical remains and ruins, the dark and stormy weather, and its own homegrown movie stars such as Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. Lee in particular radiated a feral sexuality, enabling Hammer Horror to mix a heady cocktail of sex and violence on the screen. It was irresistible.

The slasher movies that have dominated international cinema since Hammer through franchises such as Hellraiser and Saw are more sensationalist melodrama than Gothic, but Gothic film does thrive and continues to create profound unease in audiences: The Exorcist, the Alien films, Blade Runner, The Blair Witch Project, and more overtly literary pictures such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula are all contemporary classics — as is Buffy the Vampire Slayer on TV.

And despite the hi-tech nature of film-making, the profound shift in the meaning of Gothic, and the gulf of 250 years, the pulse of The Castle of Otranto still beats in these films. The action of Otranto takes place predominantly in the dark in a suffocatingly claustrophobic castle and in secret underground passages. Inexplicable events plague the plot, and the dead — embodying the inescapable crimes of the past — haunt the characters like avenging revenants. Otranto is a novel of passion and terror, of human identity at the edge of sanity. In that sense, Horace Walpole did indeed set down the template of the Gothic. The Gothic may have mutated since 1764, it may now go under many different guises, but it is still with us today. And there is no escape.

The post “There is no escape.” Horace Walpole and the terrifying rise of the Gothic appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA welcome from David Cannadine, the new editor of the Oxford DNBDo you have a vulgar tongue?Setting the scene of New Orleans during Reconstruction

Related StoriesA welcome from David Cannadine, the new editor of the Oxford DNBDo you have a vulgar tongue?Setting the scene of New Orleans during Reconstruction

Achieving patient safety by supervising residents

Residency training has always had — and always will have — a dual mission: ensuring the safety of patients treated today by doctors-in-training, and ensuring the safety of patients treated in the future by current trainees once they have entered independent practice.

Surprisingly, these two goals conflict with each other. That is because proper graduate medical education, as I have explained in an earlier essay, requires doctors-in-training to assume responsibility for the management of patients. It is not enough for residents to watch senior physicians evaluate patients, make decisions about diagnosis and therapy, and perform procedures. Rather, trainees must learn to exercise these responsibilities themselves during their residency, lest their first patients in practice become victims of inexperience and inadequate preparation.

For this reason, the needs of today’s patients and those of tomorrow’s are not necessarily the same. Future patients depend on having well prepared doctors who gained extensive independent experience as residents. Their needs are served when inexperienced trainees manage complicated patients or perform major operations today, so once in practice doctors will be able to serve patients maximally. However, today’s patients benefit when they are cared for by the most experienced physicians available. Thus, residency training must consider the safety of both present and future patients. The challenge of achieving this balance has become particularly great during the last generation, as hospitalized patients have become much sicker, hospital stays much shorter, and medical practice ever more powerful and complicated. Mistakes of omission and commission now carry potentially greater consequences.

The key to maximizing the safety of both present and future patients is by providing house officers effective supervision in their work. Many studies have found that closer supervision of residents leads to fewer errors and improved quality of care. One review observed that increased deaths were associated with poor supervision of residents in surgery, anesthesia, emergency medicine, obstetrics, and pediatrics. Another study showed that the impact of better supervision on patient safety was particularly marked with less experienced residents. Despite the contemporary furor surrounding the issue of residents’ work hours, proper supervision has consistently been found to be much more important to ensuring patient safety than house officer fatigue.

Medicine by tpsdave. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Medicine by tpsdave. Public Domain via Pixabay.We have much to learn about supervisory practices in medical education. However, current evidence suggests that the supervisory relationship is the single most important factor in the effectiveness of supervision. Especially important in this relationship are continuity over time, the supervisor’s skill at discharging oversight responsibilities while preserving sufficient intellectual autonomy for trainees, and the opportunity for both trainees and supervisors to reflect on their work. Other qualities of effective supervision have also been identified. Supervisors need to be clinically competent and knowledgeable and have good teaching and interpersonal skills. The supervising relationship must be flexible so that it changes as trainees gain experience and competence. Residents need clear feedback about their errors; corrections must be conveyed unambiguously so that residents are aware of mistakes and any weaknesses they may have. Helpful supervisory behaviors include giving direct guidance on clinical work, linking theory and practice, joint problem solving, and offering feedback reassurance, and role modeling. Ineffective supervisory behaviors include rigidity, intolerance, lack of empathy, failure to offer support, failure to follow trainees’ concerns, lack of concern with teaching, and overemphasis on the evaluative aspects of supervision.

Good supervisors, like good teachers, are made, not born. One advantage of proper supervision is the role modeling it offers residents for the supervision that they themselves may later provide. In addition, there is evidence that faculty can taught and motivated to be better teachers and supervisors.

It should be noted that good clinical supervision, like good teaching, is time-consuming. Many faculty members today find it difficult to provide the time necessary for close supervision and effective teaching because of the pressures they are under to increase their clinical or research “productivity.” For better supervision to flourish, medical schools will have to be willing to place a higher priority on the educational mission than in the past. This will entail a greater institutional willingness to promote clinical-educators, as well as the adaptation of “academies of medical educators,” mission-based budgeting, and other strategies to raise or identify funds to pay for clinical teaching and supervision. If patient safety is the goal, this is an effort worth undertaking.

The post Achieving patient safety by supervising residents appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEducation and service in residency trainingAre we alone in the Universe?Youth suicide and bullying: what’s the connection?

Related StoriesEducation and service in residency trainingAre we alone in the Universe?Youth suicide and bullying: what’s the connection?

Are we alone in the Universe?

World Space Week has prompted myself and colleagues at the Open University to discuss the question: ‘Is there life beyond Earth?’

The bottom line is that we are now certain that there are many places in our Solar System and around other stars where simple microbial life could exist, of kinds that we know from various settings, both mundane and exotic, on Earth. What we don’t know is whether any life does exist in any of those places. Until we find another example, life on Earth could be just an extremely rare fluke. It could be the only life in the whole Universe. That would be a very sobering thought.

At the other extreme, it could be that life pops up pretty much everywhere that it can, so there should be microbes everywhere. If that is the case, then surely evolutionary pressures would often lead towards multicellular life and then to intelligent life. But if that is correct – then where is everybody? Why can’t we recognise the signs of great works of astroengineering by more ancient and advanced aliens? Why can’t we pick up their signals?

The chemicals from which life can be made are available all over the place. Comets, for example, contain a wide variety of organic molecules. They aren’t likely places to find life, but collisions of comets onto planets and their moons should certainly have seeded all the habitable places with the materials from which life could start.

So where might we find life in our Solar System? Most people think of Mars, and it is certainly well worth looking there. The trouble is that lumps of rock knocked off Mars by asteroid impacts have been found on Earth. It won’t have been one-way traffic. Asteroid impacts on Earth must have showered some bits of Earth-rock onto Mars. Microbes inside a rock could survive a journey in space, and so if we do find life on Mars it will be important to establish whether or not it is related to Earth-life. Only if we find evidence of an independent genesis of life on another body in our Solar System will we be able to conclude that the probability of life starting, given the right conditions, is high.

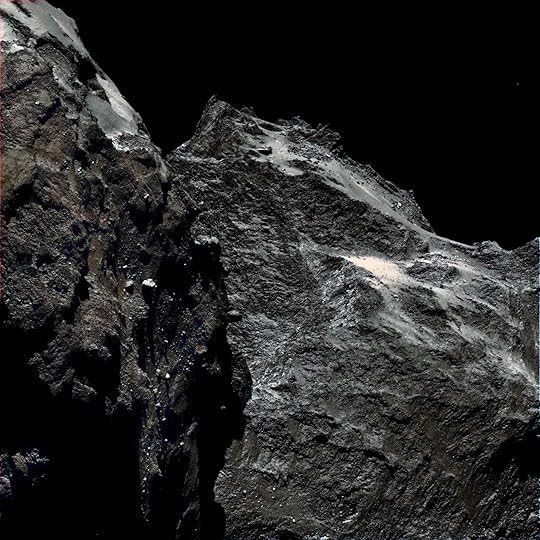

A colour image of comet 67/P from Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera. Part of the ‘body’ of the comet is in the foreground. The ‘head’ is in the background, and the landing site where the Philae lander will arrive on 12 November 2014 is out of view on the far side of the ‘head’. (Patrik Tschudin, CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr)

A colour image of comet 67/P from Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera. Part of the ‘body’ of the comet is in the foreground. The ‘head’ is in the background, and the landing site where the Philae lander will arrive on 12 November 2014 is out of view on the far side of the ‘head’. (Patrik Tschudin, CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr)For my money, Mars is not the most likely place to find life anyway. The surface environment is very harsh. The best we might hope for is some slowly-metabolising rock-eating microbes inside the rock. For a more complex ecosystem, we need to look inside oceans. There is almost certainly liquid water below the icy crust of several of the moons of the giant planets – especially Europa (a moon of Jupiter) and Enceladus (a moon of Saturn). These are warm inside because of tidal heating, and the way-sub-zero surface and lack of any atmosphere are irrelevant. Moreover, there is evidence that life on Earth began at ‘hydrothermal vents’ on the ocean floor, where hot, chemically-rich, water seeps or gushes out. Microbes feed on that chemical energy, and more complex organisms graze on the microbes. No sunlight, and no plants are involved. Similar vents seem pretty likely inside these moons – so we have the right chemicals and the right conditions to start life – and to support a complex ecosystem. If there turns out to be no life under Europa’s ice them I think the odds of life being abundant around other stars will lengthen considerably.

We think that Europa’s ice is mostly more than 10 km thick, so establishing whether or not there is life down there wont be easy. Sometimes the surface cracks apart and slush is squeezed out to form ridges, and these may be the best target for a lander, which might find fossils entombed in the slush.

Enceladus is smaller and may not have such a rich ocean, but comes with the big advantage of spraying samples of its ocean into space though cracks near its south pole (similar plumes have been suspected at Europa, but not proven). A properly equipped spaceprobe could fly through Enceladus’s eruption plumes and look for chemical or isotopic traces of life without needing to land.

I’m sure you’ll agree, moons are fascinating!

Headline image credit: Center of the Milky Way Galaxy, from NASA’S Marshall Space Flight Center. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Are we alone in the Universe? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor?The vision of ConfuciusCERN: glorious past, exciting future

Related StoriesWhat’s so great about being the VSI commissioning editor?The vision of ConfuciusCERN: glorious past, exciting future

October 2, 2014

Do you have a vulgar tongue?

Slang is in a constant state of reinvention. The evolution of language is a testament to our world’s vast and complex history; words and their meanings undergo transformations that reflect a changing environment such as urbanization. In The Vulgar Tongue: Green’s History of Slang, Jonathon Green extensively explores the history of English language slang from the early British beggar books and traces it through to modernity. He defends the importance of a versatile vocabulary and convinces us that there is dose of history in every syllable of slang and that it is a necessary part of contemporary English, no matter how explicit or offensive the content may be. Test your knowledge…how well do you know your history of slang?

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Headline image credit: Explosion. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Do you have a vulgar tongue? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1Whose muse mews?What is the most important issue in music education today?

Related StoriesBimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1Whose muse mews?What is the most important issue in music education today?

What is the most important issue in music education today?

Fall is upon us. The temperature is falling, the leaves are turning, and students are making their way back at school. To get a glimpse into the new school year, we asked some key music educators share their thoughts on the most important issues in music education today.

* * * * *

“The history of music education in the United States is integrally linked to general educational policies and initiatives, as well as American culture and society. Rationales for why music is an important component of students’ education have utilized utilitarian, aesthetic, and praxial arguments, often attempting to connect the goals of music learning with the educational priorities of the day. In the “data driven,” high stakes testing milieu of today’s educational reform movement, music educators find themselves having to defend not only music programs, but also the teaching profession in general. Political rhetoric and shrinking budgets have too often resulted in the false choice of ‘basic subjects’ over other areas of study, such as music and art, that can provide meaningful ways of understanding the world and equipping individuals to live a ‘good life.’ In this environment it is important that music teachers remain strong, articulate advocates for the value of music in the complete education of children, and to not resort to superficial reasons for music’s inclusion in school curricula. All persons deserve the opportunity to experience a life enriched through active musical participation that includes creating, performing, and listening to music. Robust school music programs help to provide the foundational understandings to make that possible. As Karl Gehrkens, former president of the Music Supervisors National Conference, stated in 1923, ‘Music for every child; every child for music.’”

—Dr. William I. Bauer, Associate Professor and Director of the Online Master of Music in Music Education program at the University of Florida, and author of Music Learning Today: Digital Pedagogy for Creating, Performing, and Responding to Music

* * * * *

“Access to quality music instruction is the most important issue in music education today. Some American children have a daily opportunity to make music during school with a certified music teacher who assists them in creating music, performing music, and responding to music. However, many children do not have this opportunity. In some cases, children may have daily access to a music teacher, but that music teacher may not organize instruction in a way that offers the opportunity to create, perform, and respond to music. Many children have access to a music teacher only a few times per week and oftentimes the lack of resources for that music program leads to a subpar experience for students. Due to a lack of state level policy regarding music education, many children have no music teacher in their school building. Although there are rich opportunities for outside of school community music in the United States, many children cannot afford to pay for music instruction outside of the school setting. Citizens interested in making a difference in music education must advocate for a well-prepared, certified music teacher in every school building. Music needs to be mandated at least twice a week in a dedicated space at the elementary level and every secondary student should have the opportunity to participate in choral, instrumental, and general music.”

—Colleen M. Conway, Professor of Music Education, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, University of Michigan, Editor-in-Chief of Arts Education Policy Review, and the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research in American Music Education

* * * * *

“The most important issue in music education today is one that has existed for as long as has formal music education: assessment. The term raises many eyebrows, and I believe in viewing assessment for both its positive attributes and for the dangers it can present. Assessment of student work is vital for accountability, curriculum development, and instructional planning, but assessment can be dangerous when it accounts only for standardized measures, when it is used punitively, and when it does not properly inform educational decision-making. Good assessment of student work in music should help students to understand their own progress, and allow them to explore music creatively. Assessment of music teachers’ work is just as crucial because music teachers must be outstanding musicians, pedagogical thinkers, and instructors. Similar to assessment of student work, assessment of teachers should help to inform teachers of their strengths and areas for growth. Good assessment of teachers should provide feedback for improvement of planning and instruction, and should encourage teachers to incorporate new ideas, technologies, and types of interaction with their students. Assessments of teachers should be based on their actual performance rather than on that of their students, as is the unfortunate case in many high-stakes testing scenarios. Thoughtful, positively focused assessment can be a powerful motivator for educational progress and change, and can help students and teachers alike to participate creatively in music.”

—Jay Dorfman, Assistant Professor in Music Education at Boston University, and author of Theory and Practice of Technology-Based Music Instruction

* * * * *

“With the current trend towards turning student evaluations into teacher accountability measures, we risk narrowly focusing music education to those skills based elements that can be easily measured. As music teacher educators we need to resist the urge to succumb to the standardized testing movement and broaden our students’ notions of what it means to be musical. We need to ensure a learner centered music education for all students that fosters creative thinking and divergent outcomes, such as composing, improvising and other forms of sonic exploration and expression through traditional and non-traditional approaches to music making.”

—Gena R. Greher, Professor of Music Education at University of Massachusetts Lowell, and co-author of Computational Thinking in Sound: Teaching the Art and Science of Music and Technology

* * * * *

“The most important issue in music education today is the lack of understanding shown by policy makers, school leaders, local politicians, and governments of the value of systematic and successful music learning across the lifespan, especially for our children and young people. Engaging in active music learning over a sustained period generates measurable physical, psychological and social benefits (as well as cultural benefit) that are long-term for the individuals and groups involved. The scientific evidence of music’s value (from clinical science, neuroscience, and social science) is increasing every day. Although we don’t yet understand clearly all the mechanisms of how music learning can promote long-term benefit, there can be no doubt that music can make a powerful and positive difference to health (physical, emotional, cognitive), whilst supporting different aspects of intellectual functioning (such as literacy) and fostering social inclusion and cohesion amongst and across diverse groups. Investing in high quality music education should be a priority for all, not just the lucky few, because music can transform lives for the better, across the lifespan.”

—Graham Welch, Professor, Institute of Education, University of London, and co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of Music Education, Volume 1 and Volume 2

Headline Image: music-classical-sheet-music-piano. Creative Commons License via Pixabay

The post What is the most important issue in music education today? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAustin City Limits through the yearsYouth suicide and bullying: what’s the connection?Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1

Related StoriesAustin City Limits through the yearsYouth suicide and bullying: what’s the connection?Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1

Youth suicide and bullying: what’s the connection?

The role of bullying in suicide among our young people has been intensely scrutinized in both media and research. As the deleterious impacts on mental and physical health for both perpetrators and targets—suicide being the most severe—become more evident, calls for framing of the problem from a public health framework have increased. A scientifically grounded educational and public health approach to both bullying and suicide prevention is required.

So let’s look at the science regarding the connection between bullying and suicide. As with most highly emotional phenomena, there has been a tendency to both overstate and minimize the connection. As Jeffrey Duong and Catherine Bradshaw point out: while the prevalence of bullying is high (approximately 20% to 28%), “most children who are bullied do not become suicidal.” At the same time, children who have been bullied have an increased risk of mental and physical problems. Melissa Holt warns us that bullying should be considered one of several factors that increase a young persons risk for suicide. We must be careful, though, not to confuse correlation with causation. That is to say, that bullying most typically has an indirect effect on a young person taking their life, rather than being the sole cause. Finally, the suicide rate (both attempts and completions) among our young people is unacceptably high and requires systematic efforts for prevention and intervention.

Bullying is an abuse of power. By definition, bullying is seen as behavior that is intended to be hurtful and targets individuals perceived to be weaker and unable to defend themselves. Bully can be direct and face-to-face, or may be conducted through social media. Amanda Nickerson and Toni Orrange Trochia reviewed recent research showing that all children involved in bullying (targets, perpetrators, and those who are both) are at higher risk for mental health problems and subsequently higher risk for suicidal behavior. This risk increases with repeated involvement in bullying and, for targets, the belief that they are alone in their plight. At the same time, social environments (community, school, family, peer) that support differences and caring relationship provide greater protection from the harmful effects of bullying.

Excluded girl. © SimmiSimons via iStock.

Excluded girl. © SimmiSimons via iStock.While the question of who gets bullied and why is complicated, we know that some groups are more likely to be the target of bullying than others. Those children who present themselves as “different” are more likely targets than those who fit in comfortably to school norms. Children from stigmatized or marginalized groups, including those with psychiatric problems, physical disabilities, sexual and gender minorities, are at higher risk for being targets of bullying and for suicidal behavior. Again, individuals from stigmatized groups with higher community, school, and family support fare better than those who perceive themselves to face torment alone.

A cultural perspective is important to understand the connection between bullying and suicide. The research on the complexity of ethnic differences in bullying and suicide is sparse and in some cases contradictory. By paying attention to bullying behaviors that happen between people of different ethnic groups and those that exist within the same ethnic group, a clearer picture arises. Different cultural patterns related to aggression and emotion expression help to understand and decode what behaviors warrant being labeled “bullying” within different cultures. Differences between ethnic groups of youth need to be taken into consideration when trying to understand whether bullying and/or suicidal behavior are on the increase. Finally, specific care and attention must be paid to the risk of both suicide and bullying among sexual and gender minority youth. Both of these groups are among the highest at risk.

In conclusion, even one suicide death that is triggered by a recent torment of bullying is too many. As we move to better our responses to the threat of suicide due to bullying, we are assisted by the careful scientific exploration of differential risk and protective factors. By taking community oriented, culturally informed approaches, we believe that current interventions can be improved and new interventions can be created.

The post Youth suicide and bullying: what’s the connection? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCERN: glorious past, exciting futureCelebrating 60 years of CERNBimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1

Related StoriesCERN: glorious past, exciting futureCelebrating 60 years of CERNBimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1

A welcome from David Cannadine, the new editor of the Oxford DNB

September 2014 marked the tenth anniversary of the publication of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Over the next month a series of blog posts explore aspects of the Dictionary’s online evolution in the decade since 2004. In this post, Sir David Cannadine describes his role as the new editor of the Oxford DNB.

Here at Princeton, the new academic year is very much upon us, and I shall soon begin teaching a junior seminar on ‘Winston Churchill, Anglo-America, and the “Special Relationship”’, which is always enormously enjoyable, not least because one of the essential books on the undergraduate reading list is Paul Addison’s marvellous brief biography, published by OUP, which he developed from the outstanding entry on Churchill that he wrote for the Oxford DNB. I’ve been away from the university for a year, on leave as a visiting professor at New York University, so there is a great deal of catching up to do. This month I also assume the editorial chair at the ODNB, as its fourth editor, in succession to the late-lamented Colin Matthew, to Brian Harrison, and to Lawrence Goldman.

As such, I shall be the first ODNB editor who is not resident in Britain, let alone living and working in Oxford, but this says more about our globalized and inter-connected world than it does about me. When I was contacted, several months ago, by a New York representative of OUP, asking me whether I might consider being the next editor, I gave my permanent residence in America as a compelling reason for not taking the job on. But he insisted that, far from being a disadvantage, this was in fact something of a recommendation. In following in the footsteps of my three predecessors (all, as it happens, personal friends) I am eager to do all I can to ensure that my occupancy of the editorial chair will not prove him (and OUP) to have been mistaken.

As must be true of any historian of Britain, the Oxford DNB and its predecessor have always been an essential part of my working life; and I can vividly recall the precise moment at which that relationship (rather inauspiciously) began. As a Cambridge undergraduate, I once mentioned to one of my supervisors that I greatly admired the zest, brio, and elan of J.H. Plumb’s brief life of the earl of Chatham, which I had been given a few years before as a school prize. ‘Oh’, he sniffily replied, ‘there’s no original research there; Plumb got it all from the DNB.’ Of course, I had heard of something called DNA; but what, I wondered, was this (presumably non-molecular) sequel called the DNB? Since I was clearly expected to know, I didn’t dare ask; but I soon found out, and so began a lifelong friendship.

Professor Sir David Cannadine, image courtesy of the ODNB editorial team.

Professor Sir David Cannadine, image courtesy of the ODNB editorial team.During my remaining undergraduate days, as I worked away in the reading room of the Cambridge University Library, the DNB became a constant source of solace and relief: for when the weekly reading list seemed overwhelming, or the essay-writing was not going well, I furtively sought distraction by pulling a random volume of the DNB off the reference shelves. As a result, I cultivated what Leslie Stephen (founding editor of the Dictionary’s Victorian edition) called ‘the great art of skipping’ from one entry to another, and this remains one of the abiding pleasures provided by the DNB’s hard-copy successor. Once I started exploring the history of the modern British aristocracy, the DNB also became an invaluable research tool, bringing to life many a peer whose entry in Burke or Debrett was confined to the barest biographical outline.

Thus approached and appreciated, it was very easy to take the DNB for granted, and it was only when I wrote a lengthy essay on the volume covering the years 1961 to 1970, for the London Review of Books in 1981, that I first realized what an extraordinary enterprise it was and, indeed, had always been since the days when Leslie Stephen first founded it almost one hundred years before. I also came to appreciate how it had developed and evolved across the intervening decades, and I gained some understanding of its strengths—and of its weaknesses, too. So I was not altogether surprised when OUP bravely decided to redo the whole Dictionary, and the DNB was triumphantly reborn as the ODNB—first published almost exactly 10 years ago—to which I contributed the biographies on George Macaulay Trevelyan and Noel Annan.

Since 2004 the Oxford DNB has continued to expand its biographical coverage with three annual online updates, the most recent of which appeared last week. In September 2013 I wrote a collective entry on the Calthorpe family for an update exploring the history of Birmingham and the Black Country, and I am eager to remain an intermittent but enthusiastic contributor now that I am editor. As we rightly mark and celebrate the tenth anniversary of the publication of the ODNB, and its successful continuation across the intervening decade, it is clear that I take over an enterprise in good spirits and an organization (as the Americans would say) in good shape. Within the United Kingdom and, indeed, around the world, the ODNB boasts an unrivalled global audience and an outstanding array of global contributors; and I greatly look forward to keeping in touch, and to getting to know many of you better, in the months and years to come.

Headline image credit: ODNB, online. Image courtesy of the ODNB editorial team.

The post A welcome from David Cannadine, the new editor of the Oxford DNB appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biographyThe Oxford DNB at 10: new research opportunities in the humanitiesHow Georg Ludwig became George I

Related StoriesThe Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biographyThe Oxford DNB at 10: new research opportunities in the humanitiesHow Georg Ludwig became George I

October 1, 2014

Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1

I was out of town at the end of this past August and have a sizable backlog of unanswered questions and comments. It may take me two or even three weeks to catch up with them. I am not complaining: on the contrary, I am delighted to have correspondents from Sweden to Taiwan. Today I will deal with the questions only about the two most recent posts.

Kiss

Our regular correspondent Mr. John Larsson took issue with my remark that kiss has nothing to do with chew and cited some arguments in favor of the chew connection. We should distinguish between the “institute of kissing” and the word for the action. As could be expected, no one knows when people invented kissing, but, according to one theory, everything began with mothers chewing their food and passing it on to their babies from mouth to mouth. I am not an anthropologist and can have no opinion about such matters. But the oldest form of the Germanic verb for “chew” must have sounded approximately like German kauen (initial t in Old Norse tyggja is hardly original). The distance between kauen and kussjan cannot be bridged.

Also from Scandinavia, Mr. Christer Wallenborg informs me that in Sweden two words compete: kyssa is a general term for kissing, while for informal purposes pussa is used. I know this and will now say more about the verbs used for kissing in the Germanic-speaking world. Last time I did not travel farther than the Netherlands (except for mentioning the extinct Goths). My survey comes from an article by the distinguished philologist Theodor Siebs (1862-1941). It was published in the journal of the society for the promotion of Silesian popular lore (Mitteilungen der Schlesischen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde) for 1903. Modern dialect atlases may contain more synonyms.

Below I will list only some of the words and phrases, without specifying the regions. Germany: küssen, piepen, snüttern (long ü), -snudeln (long u), slabben, flabben, smacken, smukken, smatschen, muschen, bussen, bütsen, pützschen, pupen (some of these words are colloquial, some verge on the vulgar). Many verbs for “kiss” (the verb and the noun) go back to Mund and Maul “mouth,” for example, mundsen, mul ~ mull, müll, mill, and the like. Mäulchen “little mouth” is not uncommon for “a kiss,” and Goethe, who was born in Frankfurt, used it. With regard to their sound shape, most verbs resemble Engl. puss, pipe, smack, flap, and slap.

Friesland (Siebs was an outstanding specialist in the modern dialects and history of Frisian): æpke (æ has the value of German ä) ~ apki, make ~ mæke, klebi, totje, kükken, and a few others, borrowed from German and Dutch. Dutch: zoenen, poenen (both mentioned in my previous blog on kiss), kussen, kissen, smokken, smakken, piper geven, and tysje.

Siebs became aware of Nyrop’s book (see again my previous blog on kiss about it) after his own work had been almost completed and succeeded in obtaining a copy of it only because Nyrop sent him one. He soon realized that his predecessor had covered a good deal of the material he had been collecting, but Nyrop’s book did not make Siebs’s 19-page article redundant, because Nyrop’s focus was on the situations in which people kiss (a friendly kiss, a kiss of peace, an erotic kiss, etc.), while Siebs dealt with the linguistic aspect of his data. It appeared that kiss usually goes back to the words for the mouth and lips; for something sweet (German gib mir ’nen Süssen “give me a sweet [thing]”); for love (so in Greek, in Slavic, and in Old Icelandic minnask, literally “to love one another”), and for embracing (as in French embrasser). Some words for kissing are onomatopoeic, and some developed from various metaphors or expanded their original sense (I mentioned the case of Russian: from “be whole” to “kiss”; Nyrop cited several similar examples). We can see that chewing has not turned up in this small catalog.

Tristram and Isolde by John William Waterhouse, 1916. Public domain via WikiArt

Tristram and Isolde by John William Waterhouse, 1916. Public domain via WikiArtSiebs also ventured an etymology of kiss and included this word in his first group. In his opinion, Gothic kukjan “to kiss” retained the original form of Old Engl. kyssan, Old Norse kyssa, and their cognates. In Old Frisian, kokk seems to have meant “speaker” and “mouth” and may thus be related to Old Icelandic kok “throat.” Siebs went on to explain how the protoform guttús yielded kyssan. Specialists know this reconstruction, but everything in it is so uncertain that the origin of kiss cannot be considered solved.

In the picture, chosen to illustrate this post, you will see the moment when Tristan and Isolde drink the fateful love potion. Two quotations from Gottfried’s poem in A. T. Hatto’s translation will serve us well: “He kissed her and she kissed him, lovingly and tenderly. Here was a blissful beginning for Love’s remedy: each poured and quaffed the sweetness that welled up from their hearts” (p. 200), and “One kiss from one’s darling’s lips that comes stealing from the depths of her heart—how it banished love’s cares!” (p. 204).

The color brown and brown animals

The protoform of beaver must have been bhebrús or bhibhrús. This looks like an old formation because it has reduplication (bh-bh) and is a -u stem. The form does not contain the combination bher-bher “carry-carry.” Beavers are famous for building dams rather than for carrying logs from place to place. Francis A. Wood, apparently, the only scholar who offered an etymology of beaver different from the current one, connected the word with the Indo-European root bheruo- ~ bhreu- “press, gnaw, cut,” as in Sanskrit bhárvati “to gnaw; chew” (note our fixation on chewing in this post!). His idea has been ignored, rather than refuted (a usual case in etymological studies). Be that as it may, “brown” underlies many names of animals (earlier I mentioned the bear and the toad; I still think that the brown etymology of the bear is the best there is) and plants. Among the plants are, most probably, the Slavic name of the mountain ash (rowan tree) and the Scandinavian name of the partridge.

American Beaver by John James Audubon, 1844. Public domain via WikiArt.

American Beaver by John James Audubon, 1844. Public domain via WikiArt.And of course I am fully aware of the trouble with the Greek word for “toad.” I have read multiple works by Dutch scholars that purport to show how many Dutch and English words go back to the substrate (the enigmatic initial a, nontraditional ablaut, and so forth). It is hard for me to imagine that in prehistoric times the bird ouzel (German Amsel), the lark, the toad, and many other extremely common creatures retained their indigenous names. According to this interpretation, the invading Indo-Europeans seem to have arrived from places almost devoid of animal life and vegetation. It is easier to imagine all kinds of “derailments” (Entgleisungen) in the spirit of Noreen and Levitsky than this scenario. Words for “toad” and “frog” are subject to taboo all over the world (some references can be found in the entry toad in my dictionary), which further complicates a search for their etymology. But this is no place to engage in a serious discussion on the pre-Indo-European substrate. I said what I could on the subject in my review of Dirk Boutkan’s etymological dictionary of Frisian. Professor Beekes wrote a brief comment on my review.

Anticlimax: English grammar (Mr. Twitter, a comedian)

I have once commented on the abuse of as clauses unconnected with the rest of the sentence. These quasi-absolute constructions often sound silly. In a letter to a newspaper, a woman defends the use of Twitter: “As someone who aspires to go into comedy, Twitter is an incredible creative outlet.” Beware of unconscious humor: the conjunction as is not a synonym of the preposition for.

The post Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1Kissing from a strictly etymological point of viewPost 450, descriptive of how the Oxford Etymologist spent part of this past August

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1Kissing from a strictly etymological point of viewPost 450, descriptive of how the Oxford Etymologist spent part of this past August

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers