Oxford University Press's Blog, page 753

October 11, 2014

The Second Vatican Council and John Henry Newman

The fiftieth anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council fell two years ago in October 2012. In December next year it will be the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Council. There is bound to be much discussion in the coming months of the meaning and significance of the Council, its failures, its successes, its misinterpretations, its distortion and exaggerations, its key seminal texts, and its future developments.

Blessed John Henry Newman has often been referred to as ‘the Father of the Second Vatican Council’. Although Newman was certainly inspirational for the theologians who were the architects of the Council’s teachings, many of which he had anticipated in the previous century, there is only one place in the conciliar documents where his direct influence can clearly be discerned, the text in the Constitution on Divine Revelation which speaks of the development of doctrine. Even so, in this most seminal of modern theologians, the theologians of the ‘ressourcement’ found a sympathetic and eloquent precursor. The ‘ressourcement’ was a theological school that sought to retrieve the sources of Christianity in the the Scriptures and the Fathers and was anxious to escape from the dead hand of a desiccated neo-scholasticism which had lost touch with the Fathers.

Newman has often suffered from selective quotation by people on the opposing wings of the Catholic Church who seek to present him as either a liberal and progressive or as a highly conservative and even reactionary thinker. But the truth is that Newman must be seen in the full range of his thought. For Newman was neither simply conservative nor liberal but is best described as a conservative radical, always open to new ideas and developments but also always sensitive to the tradition and teachings of the Church.

“To live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.” JH Newman, 1801-1890, by Babouba, Ng556. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“To live is to change, and to be perfect is to have changed often.” JH Newman, 1801-1890, by Babouba, Ng556. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. As an Anglican, his radicalism disconcerted and dismayed conservative high churchmen. As a Catholic, he disappointed the liberals because of his respect for authority. He also angered the Ultramontanes with his openness to change and reform.

In his Apologia pro Vita sua, Newman was anxious to show, in effect in accordance with his theory of doctrinal development, that his development from a simple Bible Protestantism to Roman Catholicism represented, change but change in continuity – authentic development rather than corruption. The famous seven ‘tests’ or ‘notes’ of true development that he set out in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine have frequently been dismissed but they can be shown to be applicable to the history of his own religious development.

And they are valuable in showing how the most controversial of the documents of Vatican II, the Declaration on Religious Freedom, can appear to be an abrupt change in the Church’s teaching and yet be actually an authentic development in continuity rather than discontinuity with previous teaching.

In his private letters before, during, after the First Vatican Council, Newman adumbrated a mini-theology of Councils. He was particularly interested in the connexion between Councils and how one Council modifies by adding to what a previous Council taught, and how Councils evince both change and continuity. He saw how Councils cause great confusion and controversy, not least because their teachings, which require careful interpretation, are liable to be exaggerated by opposing protagonists, and that they can have very serious unintended effects. He was also struck by the significance of what a Council does not say.

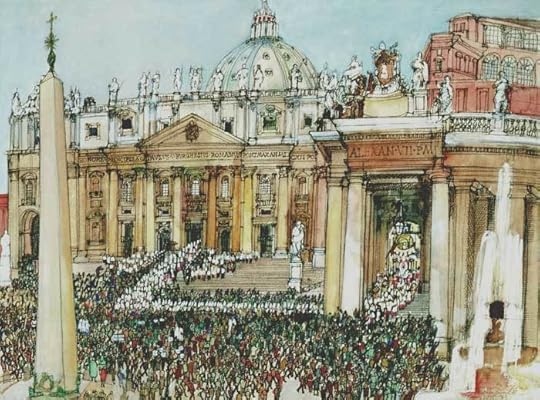

Vatican procession, by Franklin McMahon. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Vatican procession, by Franklin McMahon. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Vatican II’s silence on evangelization is a striking example of this. However, the understanding of the Church as fundamentally the organic communion of the baptized, with which its Constitution on the Church begins, has been concretely realized in the new ecclesial communities and movements. These constitute not only a clear response to this silence but also exemplify Newman’s point in the Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine that such an idea becomes clearer in the course of time.

The first two chapters of the Constitution, which is the centrepiece of a Council almost entirely occupied with the Church, emphasise the charismatic dimension of the Church, the importance of which Newman understood very well as both an Anglican and Catholic. He himself was not only the leader of the Oxford Movement but also the founder of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in England, which he knew had originally begun as in effect an ecclesial community before it became to be virtually a clerical congregation.

The writings of Newman that anticipate the documents of Vatican II provide a valuable and corrective hermeneutic for the understanding of the conciliar documents that have been frequently distorted by exaggerations and partial interpretations. They illustrate how Newman was both the radical reformer and the traditional conservative. The so-called ‘new evangelization’ of secularized post-Christians was also anticipated by Newman in his little read Catholic novel Callista, which in fact dramatizes the approach of an earlier Anglican sermon. What is particularly striking is that his famous argument from conscience for the existence of God is not the primary apologetic approach that he advocates.

The post The Second Vatican Council and John Henry Newman appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe history of Christian art and architectureFire in the nightMonastic silence and a visual dialogue

Related StoriesThe history of Christian art and architectureFire in the nightMonastic silence and a visual dialogue

October 10, 2014

Domestic violence and the NFL. Are players at greater risk for committing the act?

As the domestic violence controversy in the NFL has captured the attention of fans and global media, it seems it has become the No. 1 off-field issue for the league. To gain further perspective into the matter of domestic violence and the current NFL situation, I spoke with Greta Friedemann-Sánchez, PhD and Rodrigo Lovatón, authors of the article, “Intimate Partner Violence in Colombia: Who Is at Risk?,” published in Social Forces, that explores the prevalence of intimate partner violence and the certain risk factors that increase its likelihood.

What do you think of the recent media coverage of domestic violence in the NFL?

In 2010, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that in the United States 24% of women and 13% of men have experienced severe physical violence by an intimate partner at some point during their life. Furthermore, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (Department of Justice) calculates that domestic violence accounted for 21% of all violent victimizations between 2003 and 2012 and about 1.5 million cases in 2013. If emotional abuse and stalking are taken into account, the prevalence rates increase. In some countries the prevalence is even higher. In Colombia, for example, 39% of women have experienced physical violence in their lifetimes. The recent media coverage of domestic violence shows that this is an important policy issue that has not received adequate attention in the United States or internationally. Unfortunately, this is a missed opportunity to educate the public on the high prevalence rates and the negative effects domestic violence has, not only for the victim but for all the members of a family. Equally invisible in the coverage is the fact that domestic violence is an “equal opportunity” event, meaning that it is present in families regardless of socioeconomic status, race, ethnic affiliation, and so on. Domestic violence, and more specifically intimate partner violence, can be just as present in NFL players’ families who are on the eye of the public, as it can be in any other family. The issue, however, remains hidden for the most part. It takes a celebrity to be involved for the issue to gain visibility. In that sense, we are glad the media covered it. This is a policy issue that needs to be appropriately analyzed and addressed.

What do you think is an appropriate punishment for an NFL player who is convicted of domestic violence?

We agree that a professional sports organization, that has extensive media coverage with a large audience, including children and adolescents, should not allow a player who is convicted of domestic violence to participate. Organized sports organizations sell more than just games, they sell the personalities and lives of their players. Players are often held as role models, their careers and lives are admired. To allow a player to continue playing would endorse and normalize violent behavior. Intimate partner violence has long term negative physical, emotional, and economic consequences for the victims, which are often overlooked. In fact, children who witness violence at home have negative emotional and educational outcomes too. Witnessing violence as a child or being a victim of violence as a child are some of the strongest predictors for becoming a victim or a perpetrator of violence later in life. Therefore, the NFL or any sports organization should reject this kind of behavior by disallowing domestic violence offenders from participating in any of their activities.

Do you think that giving a person who commits domestic violence a more severe punishment will decrease the chances that the person will commit violence again?

Types and intensity of violence are varied, and so are the legal mechanisms in place to protect victims and punish batterers. Victims do not always get the support they need from law enforcement. Furthermore, protective and punitive laws are not always enforced in an adequate manner, consequently, victims have a chance to be re-victimized and re-traumatized as the perpetrators become even more violent as a result of the victims’ reporting. The proportion of domestic violence crimes reported to the police represents about 50% of all identified cases between 2003 and 2012 in the United States, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Department of Justice. These issues are recursive. The experience for victims outside of the United States can be even direr as domestic violence legislation may be in its infancy.

Do you think that the recent media attention surrounding domestic and/or that this will increase or decrease the likelihood of/reduce other victims coming forward to report abuse?

Neither. Resolving intimate partner violence requires a multi-pronged approach. Increased visibility of the problem afforded by the recent media coverage might propel better law enforcement, increased funding for research, and implementation of prevention pilot programs that engage men and boys, just to name a few. We need better and more preventive, protective, and punitive mechanisms in place. In addition, the mechanisms in place need to be evaluated for effectiveness in responding to the issue. Until some of these steps happen, simply having more media attention will not have an effect on reporting.

Abandoned child’s shoe on balcony with diffuse filter. © sil63 via iStock.

Abandoned child’s shoe on balcony with diffuse filter. © sil63 via iStock.What are some of the reasons women tend to stay in domestic violence situations?

Why do perpetrators exercise violence against their intimate partners? These questions go hand in hand, yet it is usually the first that is asked, although both are increasingly in the scope of research given the increase in violence against women worldwide. Women’s economic dependence on their partners, which gets amplified when children are present, contributes to women being locked into violent situations. Lack of employment options, being unemployed, having low-wage employment makes women financially dependent on their partners. Lack of affordable day care, day care with limited hours, and school schedules without after-school programs limit women’s participation in employment. Even women who are employed and have livable wages might find it hard to leave if temporary shelters and affordable housing are not available. But the barriers to exiting a violent relationship are not only material. Being abused is a stigmatizing experience. Victims are reluctant to be shamed by their family, friends, and society at large. In addition, the exercise of controlling and humiliating behaviors on the part of batterers has the effect of lowering the victims’ self-esteem and self-efficacy. Victims may doubt their capacity to survive on their own and with their children. But controlling behaviors also include batterers’ being effective at sabotaging the victims’ efforts to access her social support network, to gain employment, or to arrange an alternative living place. In many instances, the episodes of abuse are interspersed by weeks or months of relative calm, and victims may believe their partners have changed, only to find themselves in the same or worse situation. In addition, societies have cultural scripts of what is included in the marital contract, which may justify violence under certain circumstances. Gender norms give men the right to control their intimate partner’s behavior, to exert influence, and to resolve disputes with violence. Furthermore, women are socialized to prioritize the children and family “unity” over their welfare; women may perceive that the children will be negatively affected by a separation, not knowing the negative effects they may already be experiencing.

Who are most at risk for being a victim of domestic violence?

Several factors contribute to the risk of being a victim of intimate partner violence. While there are general patterns, the specifics may vary by country. In our recent study using data from Colombia’s Demographic and Health Surveys, we found that the highest risk factors were associated with the maltreatment of a woman’s partner when he was a child, and current child maltreatment by the woman’s partner. Higher risk is associated with lower educational status of both partners, lower socioeconomic status (only for physical violence), for younger women, and for women working outside of the home. This last factor is especially interesting given the role that income plays in household negotiation dynamics. Gender differences in power among family members affect each member’s economic choices and behavior, including individual’s bargaining over the allocation of material and time resources within the household, over gender norms, and even over how much abuse to exert or resist. It has long been hypothesized that income provides women with strong leverage in family negotiations. But our results and those found in studies in other countries are revealing that the dynamics of negotiation and violence may be heavily mediated by gender norms. In effect, gender norms about women’s socially acceptable behavior, including working for pay, might trump the leverage they can effect with income. In addition, we do not know the effect of relative wages of both partners on violence. What is known for the United States is that economic stress in a family increases the risk for violence. Gender norms of masculinity that prescribe men as the breadwinners have an effect: men who are unemployed are at greater risk for being perpetrators of violence. The same is true for men who endorse rigid views of masculinity, including the norms that men should dominate women.

How can we best help those most at risk of domestic violence?

Interventions at the individual and community level that address gender equitable norms and the construction of gender relations via socialization are simultaneously protective (batterer intervention programs) and preventive. In the same vein, promoting boys and men’s participation in activities considered feminine under rigid norms of masculinity, such as taking care of children, of the sick and disabled, and doing domestic work. Another line of response is to work on those risk factors that can be shaped by public policies, such as promoting equitable access to employment for women and an extended access to education to the population in general. In addition, special care is required for those groups that are at greater risk to suffer from violence, such as households with lower socioeconomic status, with younger women, more children, and where the partners have a previous history of maltreatment. Workshops on parenting skills and non-violent forms of disciplining children. Last, a policy response should also include better mechanisms for the victims to come forward and report the problem, support systems to help them escape from abusive domestic environments, and psychological service for trauma recovery.

Is there anything else you think we can learn about domestic violence in the United States from the recent NFL cases?

From the way the media covered it, it is clear that the general public is not well informed about intimate partner violence. More education will help de-stigmatize the issue.

Headline image credit: Grass. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Domestic violence and the NFL. Are players at greater risk for committing the act? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFalling out of love and down the housing ladder?Who decides ISIS is a terrorist group?Examining 25 years of public opinion data on gay rights and marriage

Related StoriesFalling out of love and down the housing ladder?Who decides ISIS is a terrorist group?Examining 25 years of public opinion data on gay rights and marriage

The history of Christian art and architecture

Although basilisks, griffins, and phoenixes summon ideas of myth and lore, they are three of several fantastic beings displayed in a Christian context. From the anti-Christian Roman emperor Diocletian to the legendary Knights of the Templar, a variety of unexpected subjects, movements, themes, and artists emerge in the history of Christian art and architecture. To get an idea of its scope, we mined The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture for information to test your knowledge.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Headline image credit: St Peter’s facade. Photo by Livioandronico2013. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The history of Christian art and architecture appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow much do you know about Alexander the Great?Contagious disease throughout the agesMonastic silence and a visual dialogue

Related StoriesHow much do you know about Alexander the Great?Contagious disease throughout the agesMonastic silence and a visual dialogue

Fire in the night

Wilderness backpacking is full of surprises. Out in the wilds, the margin between relentless desire and abject terror is sometimes very thin. One night last fall, I lay in a hammock listening to water tumbling over rocks in the Castor River in southern Missouri. I’d camped at a point where the creek plunges through a boulder field of pink rhyolite. These granite rocks are the hardened magma of volcanic explosions a billion and a half years old. I’d tried to cross the water with my pack earlier, but the torrent was running too fast and deep. I had to camp on this side, facing the darker part of the wilderness instead of entering it.

By starlight I watched the silhouette of tall pines atop the ridge on the opposite bank, having crawled into a sleeping bag to ward off the cold. Suddenly I noticed a campfire in the distant trees along the ridge. I hadn’t seen it before and was surprised anyone would be there. Entrance to the river’s conservation area is only feasible from this side of the water. Sixteen hundred acres of uninhabited wilderness extend beyond the horizon. But there it flickered, a light coming through the trees.

Gradually the fire climbed higher into the pines, giving me pause. It was spreading. The whole sky behind the distant trees was glowing, a forest fire apparently making its way up the other side of the ridge. I felt as much awe as fear at the time, being mesmerized by the strange play of light in the trees. But for an instant, as it burst through the treetops, I knew something was terribly wrong, a light flaring out … brighter than fire.

Late moon rising in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Photo by Justin Kern. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via justinwkern Flickr.

Late moon rising in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Photo by Justin Kern. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via justinwkern Flickr.Then it struck me. After a week of overcast nights, I’d forgotten the coming of the full moon. There it was, in all its splendor. I hadn’t witnessed a raging forest fire, much less a numinous apparition. Yet it was both. I sensed what primeval hunters ten thousand years ago might have made of such an event: The soul-gripping mystery of fire breaking into the night.

In Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa, her Kenyan house-boy awakens her one night, whispering, “Msabu, I think that you had better get up. I think that God is coming.” He points out the window to a huge grass-fire burning on the distant hills, rising like a towering figure. Intending to quiet his fears, she explains that it’s nothing more than a fire. “It may be so,” he responds, un-persuaded. “But I thought that you had better get up in case it was God coming.” This same possibility is what draws me again and again to backpacking in wild terrain…the prospect that God (that Fire) might be coming in the night.

Wilderness is a feeder of desire. It fosters my longing for unsettling beauty, for a power I cannot control, for a wonder beyond my grasp. In its wild grandeur and quiet simplicity, it attracts me to a mystery I can’t begin to name. Yet I’m compelled to write about what can’t be put into words. What sings in the corners of an Ozark night is beyond my capacity for language. But I can be crazy in love with it…scribbling, in turn, whatever I’m able to mumble about the experience.

“Through fire everything changes,” wrote Gaston Bachelard. “When we want everything to be changed we call on fire.” That’s as true of our relationship to the earth as it is of our connection with God. In our post-Enlightenment, post-modern world, we’ve only just begun to entertain awe and overcome the awkwardness we feel in acknowledging the marvels of the natural world. Rainer Maria Rilke hiked the cliffs overlooking the Gulf of Trieste in northern Italy in 1898, on what’s known today as the Rilke Trail, with its scenic view of the Adriatic coast. He wrote in his diary: “For a long time we walked along next to each other in embarrassment, nature and I. It was as if I were at the side of a being whom I cherished but to whom I dared not say: ‘I love you.’”

But we’re learning how to love again. Part of the “Great Turning” Joanna Macy describes is a growing ecological awareness of our need (and desire) to honor the larger community of life, to restore what Thomas Berry calls the “Great Conversation” between human beings and the earth. Only as we come to reverence mystery and “harness the energies of love,” will we realize—with Teilhard de Chardin—that “for a second time in the history of the world, humans will have discovered fire.”

The post Fire in the night appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 2Monastic silence and a visual dialogueThe divine colour blue

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 2Monastic silence and a visual dialogueThe divine colour blue

A Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 2

We’re getting ready for Halloween this month by reading the classic horror stories that set the stage for the creepy movies and books we love today. Check in every Friday this October as we tell Fitz-James O’Brien’s tale of an unusual entity in What Was It?, a story from the spine-tingling collection of works in Horror Stories: Classic Tales from Hoffmann to Hodgson, edited by Darryl Jones. Last we left off the narrator had moved into a reported haunted boarding house. After a month of waiting for something eerie to happen, the boarders were beginning to believe there was nothing supernatural at all in the residence…

Things were in this state when an incident took place so awful and inexplicable in its character that my reason fairly reels at the bare memory of the occurrence. It was the tenth of July. After dinner was over I repaired, with my friend Dr Hammond, to the garden to smoke my evening pipe. Independent of certain mental sympathies which existed between the Doctor and myself, we were linked together by a vice. We both smoked opium. We knew each other’s secret, and respected it. We enjoyed together that wonderful expansion of thought, that marvellous intensifying of the perceptive faculties, that boundless feeling of existence when we seem to have points of contact with the whole universe,—in short, that unimaginable spiritual bliss, which I would not surrender for a throne, and which I hope you, reader, will never—never taste.

Those hours of opium happiness which the Doctor and I spent together in secret were regulated with a scientific accuracy. We did not blindly smoke the drug of paradise, and leave our dreams to chance. While smoking, we carefully steered our conversation through the brightest and calmest channels of thought. We talked of the East, and endeavored to recall the magical panorama of its glowing scenery. We criticised the most sensuous poets,—those who painted life ruddy with health, brimming with passion, happy in the possession of youth and strength and beauty. If we talked of Shakespeare’s ‘Tempest,’ we lingered over Ariel, and avoided Caliban. Like the Guebers, we turned our faces to the east, and saw only the sunny side of the world.

This skilful coloring of our train of thought produced in our subsequent visions a corresponding tone. The splendors of Arabian fairy-land dyed our dreams. We paced that narrow strip of grass with the tread and port of kings. The song of the rana arborea, while he clung to the bark of the ragged plum-tree, sounded like the strains of divine musicians. Houses, walls, and streets melted like rain-clouds, and vistas of unimaginable glory stretched away before us. It was a rapturous companionship. We enjoyed the vast delight more perfectly because, even in our most ecstatic moments, we were conscious of each other’s presence. Our pleasures, while individual, were still twin, vibrating and moving in musical accord.

On the evening in question, the tenth of July, the Doctor and myself drifted into an unusually metaphysical mood. We lit our large meerschaums, filled with fine Turkish tobacco, in the core of which burned a little black nut of opium, that, like the nut in the fairy tale, held within its narrow limits wonders beyond the reach of kings; we paced to and fro, conversing. A strange perversity dominated the currents of our thought. They would not flow through the sun-lit channels into which we strove to divert them. For some unaccountable reason, they constantly diverged into dark and lonesome beds, where a continual gloom brooded. It was in vain that, after our old fashion, we flung ourselves on the shores of the East, and talked of its gay bazaars, of the splendors of the time of Haroun, of harems and golden palaces. Black afreets continually arose from the depths of our talk, and expanded, like the one the fisherman released from the copper vessel, until they blotted everything bright from our vision. Insensibly, we yielded to the occult force that swayed us, and indulged in gloomy speculation. We had talked some time upon the proneness of the human mind to mysticism, and the almost universal love of the terrible, when Hammond suddenly said to me,

‘What do you consider to be the greatest element of terror?’

The question puzzled me. That many things were terrible, I knew. Stumbling over a corpse in the dark; beholding, as I once did, a woman floating down a deep and rapid river, with wildly lifted arms, and awful, upturned face, uttering, as she drifted, shrieks that rent one’s heart, while we, the spectators, stood frozen at a window which overhung the river at a height of sixty feet, unable to make the slightest effort to save her, but dumbly watching her last supreme agony and her disappearance. A shattered wreck, with no life visible, encountered floating listlessly on the ocean, is a terrible object, for it suggests a huge terror, the proportions of which are veiled. But it now struck me, for the first time, that there must be one great and ruling embodiment of fear,—a King of Terrors, to which all others must succumb. What might it be? To what train of circumstances would it owe its existence?

‘I confess, Hammond,’ I replied to my friend, ‘I never considered the subject before. That there must be one Something more terrible than any other thing, I feel. I cannot attempt, however, even the most vague definition.’

‘I am somewhat like you, Harry,’ he answered. ‘I feel my capacity to experience a terror greater than anything yet conceived by the human mind;—something combining in fearful and unnatural amalgamation hitherto supposed incompatible elements. The calling of the voices in Brockden Brown’s novel of “Wieland” is awful; so is the picture of the Dweller of the Threshold, in Bulwer’s “Zanoni”; but,’ he added, shaking his head gloomily, ‘there is something more horrible still than these.’

‘Look here, Hammond,’ I rejoined, ‘let us drop this kind of talk, for heaven’s sake! We shall suffer for it, depend on it.’

‘I don’t know what’s the matter with me to-night,’ he replied, ‘but my brain is running upon all sorts of weird and awful thoughts. I feel as if I could write a story like Hoffman, to-night, if I were only master of a literary style.’

‘Well, if we are going to be Hoffmanesque* in our talk, I’m off to bed. Opium and nightmares should never be brought together. How sultry it is! Good-night, Hammond.’

‘Good-night, Harry. Pleasant dreams to you.’

‘To you, gloomy wretch, afreets, ghouls, and enchanters.’

Check back next Friday, 17 October to find out what happens next.

Headline image credit: Once Upon a Midnight Dreary by Andi Jetaime, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A Halloween horror story : What was it? Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it?The anti-urban tradition in America: why Americans dislike their citiesHow much do you know about Alexander the Great?

Related StoriesA Halloween horror story : What was it?The anti-urban tradition in America: why Americans dislike their citiesHow much do you know about Alexander the Great?

The anti-urban tradition in America: why Americans dislike their cities

Another election season is upon us, and so it is time for another lesson in electoral geography. Americans are accustomed to color-coding our politics red and blue, and we shade those handful of states that swing both ways purple. These color choices, of course, vastly simplify the political dynamic of the country.

Look more closely at those maps, and you’ll see that the real political divide is between metropolitan America and everywhere else. The blue dots on the map are, in fact, tiny, and the country is otherwise awash in red. Those blue dots, though, are where most of us live — 65% of us according the Brookings Institution live in metro regions of 500,000 or more — and those big red areas are increasingly empty.

The urban-rural divide has existed in American politics from the very beginning. It is a central irony of American political life that we are an urbanized nation inhabited by people who are deeply ambivalent about cities.

It’s what I call the “anti-urban tradition” in American life, and it comes in two parts.

On the one hand, American cities — starting with Philadelphia in the 18th century — have always been places of ethnic, racial, religious, and cultural diversity. First stop for immigrant arrivals from eastern Europe or the American south, cities embodied the cosmopolitan ideal that critic Randolph Bourne celebrated in his 1916 essay “Trans-National America.”

Not all Americans were as enthusiastic as Bourne about cities filling up with Catholics from Italy and Poland, Jews from Russia and Lithuania, and African-Americans from Mississippi and North Carolina. Many, in fact, recoiled in horror at all this heterogeneity. Many, of course, still do, as when Republican Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin campaigned in North Carolina and called small towns there “real America.”

Italian immigrants pictured along Mulberry Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, ca. 1900. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Italian immigrants pictured along Mulberry Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, ca. 1900. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.On the other hand, the industrial cities that boomed at the turn of the 20th century relied on the actions of government to make life livable. Paved streets, clean water, sanitary sewers — all this infrastructure required the intervention of local, state, and eventually the federal government. Indeed, the 20th century city is where our commitments to the public realm have been given their widest expression — public space, public transportation, public education, public housing. And anti-urbanists then and now have a deep suspicion of those public, “collective” commitments.

In this sense, cities stand as antithetical to the basic, bedrock, “real” American values: self-reliant individualism and the supremacy of all things private. The 2012 Republican Party Platform, for example, denounced “sustainable development,” often associated with urbanist design principles, as nothing less than an assault on “the American way of life of private property ownership, single family homes, private car ownership and individual travel choices, and privately owned farms.”

Yet while anti-urbanism today is closely associated with Tea Party conservatives, its history in the 20th century is more complicated. The American antipathy toward our cities has been common across the political spectrum.

Franklin Roosevelt, architect of the modern liberal state, disliked cities personally — one of his closest aides described him as a “child of the country” who saw cities as “a perhaps necessary nuisance.” He was, to borrow the title of a 1940 biography, a “country squire in the White House.”

The New Deal reflected that anti-urban feeling. While a number of his New Deal programs addressed themselves to the failing industrial economy of the nation’s cities, FDR’s larger ambition was to “decentralize” cities by moving people and industry out into the hinterlands. This urge tied together the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the program to build a series of entirely new towns. After all, according to New Dealer Rexford Tugwell, FDR “always did, and always would, think people better off in the country.”

A generation later, the counter-culture of the 1960s which had emerged on college campuses in Berkeley, Madison, Ann Arbor, and elsewhere manifested its own version of anti-urbanism. Fed up with what they saw as America’s un-savable cities, they went back to the land in dozens of different communal experiments. So many young people joined the exodus out of the city that Newsweek magazine declared 1969 “The Year of the Commune.”

Whether in the hills of Vermont or the hills of Marin County, communards shared the anti-urban impulse with their parents, who had left the city to move to the suburbs in the 1950s. As Steve Diamond put it in a 1971 book describing a trip from his commune back to New York: “you could feel yourself approaching the Big C (City, Civilization, Cancer) itself, deeper and deeper into the decaying heart.” These rebels might not have recognized their resemblance to their parents, but it was there in their shared anti-urban rhetoric.

Certainly, our ambivalence toward our cities lies beneath our unwillingness to tackle urban problems, whether in Detroit or Cleveland or Philadelphia. But the consequences of our anti-urban tradition are more wide-ranging. Our inability to think in public terms, to address the commonweal, grows directly out of our experience running away from cities in the 20th century. If we want a more effective and invigorated politics in the 21st century, therefore, we will have to outgrow our anti-urban habits.

Featured image: Aerial view of the tip of Manhattan, New York, United States, ca. 1931. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The anti-urban tradition in America: why Americans dislike their cities appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow much do you know about Alexander the Great?Monastic silence and a visual dialogue“A Bright But Unsteady Light”

Related StoriesHow much do you know about Alexander the Great?Monastic silence and a visual dialogue“A Bright But Unsteady Light”

How much do you know about Alexander the Great?

Although Alexander the Great died more than two-thousand years ago, his name is synonymous with power, innumerable conquests and incredible leadership. Born in 356 BC, Alexander was tutored in his early years by Aristotle before succeeding his father Philip as King of Macedonia and the mainland of Greece. Early in his reign he set about releasing the Greeks from Persian domination, but continued his campaigns into a programme of imperialist aggrandizement that eventually created a massive, albeit short‐lived, empire from India to Egypt. After his death from fever in 323 BC his hastily constructed dominion fell apart. The most lasting tribute to his achievement being the town of Alexandria, which he founded in Egypt in 331 BC.

How much do you know about one of history’s greatest leaders?

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Headline image credit: Alexander the Great in the Temple of Jerusalem, by Sebastiano Conca, 1750. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How much do you know about Alexander the Great? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesContagious disease throughout the agesWhat’s your gut feeling?Why do you love the VSIs?

Related StoriesContagious disease throughout the agesWhat’s your gut feeling?Why do you love the VSIs?

October 9, 2014

Contagious disease throughout the ages

Contagious disease is as much a part of our lives as the air we breathe and the earth we walk on. Throughout history, humankind’s understanding of disease has shifted dramatically as different cultures developed unique philosophic, religious, and scientific beliefs. From Galen in Ancient Rome to Walter Reed in the United States, the collective experiences of those before us have come to inform our present understanding of contagious disease. See how much you know about the history of contagious disease.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Headline image credit: Copper engraving of Doctor Schnabel [i.e Dr. Beak], a plague doctor in seventeenth-century Rome, with a satirical macaronic poem (‘Vos Creditis, als eine Fabel, / quod scribitur vom Doctor Schnabel’) in octosyllabic rhyming couplets. Public domain Wikimedia Commons

The post Contagious disease throughout the ages appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDo you have a vulgar tongue?Monastic silence and a visual dialogueThe Oxford DNB at 10: what we know now

Related StoriesDo you have a vulgar tongue?Monastic silence and a visual dialogueThe Oxford DNB at 10: what we know now

An inside look at AMS/SMT Meeting

In about a month, the American Musicological Society will again gather to confer, listen, perform, and celebrate. Our Annual Meeting this year will be held in Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s largest city. We meet from Thursday to Sunday, 6-9 November, downtown at the Wisconsin Center and the Hilton Hotel. This year we are joined by the Society for Music Theory in what promises to be a very special meeting.

AMS Photo of 2009 Annual Meeting

AMS Photo of 2009 Annual MeetingThe program committees of the AMS and SMT have been hard at work assembling a rich selection of papers spanning a wide array of topics, from chant and medieval motets to Steve Reich, Dolly Parton, and almost everything in between. The program is especially rich in sessions devoted to American music and music and politics, with two sessions on World War I to mark this year’s centennial. Among the newer approaches appearing on the program are sessions on music and activism, arts efficacy, and intellectual property. Joint sessions featuring collaborations between AMS and SMT members include a panel on Thomas Adès, alternative-format sessions entitled “Queer Music Theory: Interrogating Notes of Sexuality” and “Why Voice Now?”, and a how-to session on preparing poster presentations that includes examples: eleven poster presentations on empirical approaches to music theory and musicology. In addition to the usual wide range of evening sessions presented by AMS committees and study groups, other evening sessions explore such topics as hymnological research, post-1900 musical patronage, the pedagogy of seventeenth- century music, and digital musicology.

Special musical performances over the weekend include Milwaukee’s Early Music Now presenting Quicksilver (Boston/New York) in a program entitled “The Invention of Chamber Music,” the Milwaukee Symphony performing Prokofiev’s “Classical” Symphony and a premiere of Marc Neikrug’s Bassoon Concerto, David Schulenberg in a lecture-recital on C. P. E. Bach (it is the 300th anniversary of his birth this year), and male soprano Robert Crowe and the group Il Furioso in concert entitled “From Carissimi to Croft: The Influence of the Italian Solo Motet in English Sacred Solo Music of the Restoration.”

There’s lots more at this gathering — book fair, professional development workshops, and (not least) dozens of alumni receptions. It’s like a big reunion at times! But the most important aspect: presenting the latest research in musicology and music theory — will be central, and will send ripples well beyond the meeting, as presentations are honed and prepared for publication at our blog, Musicology Now, or in our journal, JAMS. It’s an exciting time–please come join us!

Headline Image: Cello Detail Instrument String Musical. CC0 via Pixabay

The post An inside look at AMS/SMT Meeting appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA spike in “compassion erosion”Monastic silence and a visual dialogueThe Oxford DNB at 10: what we know now

Related StoriesA spike in “compassion erosion”Monastic silence and a visual dialogueThe Oxford DNB at 10: what we know now

A spike in “compassion erosion”

For over thirty years my primary specialty has been the prevention of secondary stress (the pressures experienced in reaching out to others.) During these three decades, I have experienced periods during which the situation has become more difficult for those in the healing and helping professions. For the past several years up to the present, I believe this has become the case again—with an even greater, far ranging initial negative impact, not only for professionals, but also for those whom they serve.

In some cases, the impact I have noted is quite dramatic. When getting ready to speak to military chaplains in Germany, many of whom returned recently from Iraq and Afghanistan, a colonel walked up to me and said: “Before you give your presentation on resilience, I want to give you a caution.” “What is it?” I asked. “There are a lot of ghosts in this room,” he said. “What do you mean by that?” I responded. After a pause, he said, “There’s nothing left inside them.”

Such cases are often termed “acute secondary stress.” This occurs when helpers and healers encounter trauma in others in such a dramatic way that their own sense of well-being is psychologically contaminated. As a result, they too can begin demonstrating the symptoms and signs of post-traumatic stress. Their dreams can be disturbed, their sense of security disrupted, and their overall outlook on the world dimmed.

However, during these times, I have found that a possibly even more disturbing pattern is one termed “chronic secondary stress,” or what has long been called “burnout.” Although this sounds less dangerous, and is certainly not as dramatic as its acute counterpart, I find it to be more worrisome because it is so insidious. Marshall McCluhan, a Canadian philosopher of communications, once said, “If the temperature of the bath rises one degree every ten minutes, how will the bather know when to scream?” In today’s society, I don’t believe we know when to scream or, in the parlance of what I would term “compassion erosion,” know the signs of when it is essential to strengthen or own a self-care program so we can continue to have the broad shoulders to bear others’ burdens as well as our own.

This is not only an American problem, it’s a worldwide one. After presenting a lecture on maintaining a healthy perspective to an audience in Johannesburg, South Africa, a social worker said that she had had enough and was going to leave the profession. When I asked her why, she said that she worked with women who were single parents, had been sexually abused, and were living on the edge of poverty. When she would go to court with them because of the rape they had experienced, they would need to take a day off from work; something they could ill afford. Yet, often the judge would just look at them and say, “Oh, I haven’t had time to look at the material. Schedule another time to come back.” She was clearly despondent and felt she wasn’t making an impact, despite her efforts to help the women that she served.

Rosco, a post-traumatic stress disorder companion animal, stands behind his owner Sgt. 1st Class Jason Syriac, a military police officer with the North Carolina National Guard’s Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 130th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade, at his unit’s armory in Charlotte, N.C., during formation, Jan. 11. Syriac, a two-time Iraq war veteran, said he hopes that by other soldiers meeting Rosco, the experience will help other service members understand the benefits of a companion animal for those with PTSD. U.S. Army National Guard Photo by Staff Sgt. Mary Junell, 130th via dvids Flcikr.Maneuver Enhanced Brigade Public Affairs/Released. via Military Times.

Rosco, a post-traumatic stress disorder companion animal, stands behind his owner Sgt. 1st Class Jason Syriac, a military police officer with the North Carolina National Guard’s Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 130th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade, at his unit’s armory in Charlotte, N.C., during formation, Jan. 11. Syriac, a two-time Iraq war veteran, said he hopes that by other soldiers meeting Rosco, the experience will help other service members understand the benefits of a companion animal for those with PTSD. U.S. Army National Guard Photo by Staff Sgt. Mary Junell, 130th via dvids Flcikr.Maneuver Enhanced Brigade Public Affairs/Released. via Military Times.Even when the individual is initially optimistic and energetic, staying the course can still be problematic. A professional caregiver for the Veteran’s Administration enthusiastically greeted one of the returning Vets when he came in for his initial appointment. He responded by saying, “Boy, you are full of great energy.” To which she smiled and replied, “You have served our Country well. Now, come on in and let us know what we can do for you.” Yet, in the past months she has had to deal with the unpleasant reports that seem to tar the whole VA. Few reports include reference to those workers who are doing good work and truly respect the deserving clients they serve.

The problem goes beyond these events of course. Everyone, not simply helping and healing professionals, are being bombarded with negative and, in some cases, tragic events either directly or indirectly: news of the horrible outcomes of wars in the Middle East, physicians being sued not for malpractice but mispractice (even though no one can be perfect 100% of the time), financial stress due to the unavailability of good paying positions, educators being hounded rather than supported by parents when their children are corrected or not given the grade they expect, clergy being treated with disdain even though they have done nothing inappropriate themselves, nurses being unappreciated for their role as representing the heart of health care… The list is endless and causes both a drain on one’s personal quality of life and an increase in compassion erosion (a decrease in the ability to reach out to others in need on a continued, natural basis).

So what is to be done? Well, to start, several essential steps must be taken by all of us—not just those among us who are in the helping and healing professions. One of these actions is to reframe any efforts at helping others in our circle of friends, family, and those whom we serve so that we focus on faithfulness (which is in our control) instead of success (which never totally is). In the case of the South African social worker, I emphasized to her that she was the only one present to the poor abused women whom she served and this, in and of itself, was of crucial importance and was definitely a positive support.

In addition to appreciating the power of presence, spending time on self-care is also important because one of the greatest gifts we can share with others is a sense of our own peace and a healthy perspective – but we can’t share what we don’t have. In a restaurant, workers are mandated to wash their hands after they go to the lavatory so they don’t contaminate the food of those they serve. In the hospital, the workers must also wash their hands before as well as after they use the bathroom to decrease the occurrence of cross contamination. The same is necessary psychologically for those of us who serve others—even if it is simply our families or co-workers. We must take the necessary steps to be resilient so when encountering negativity, we are not psychologically infected by their problems. Of what good can we be when this happens?

Finally, recognizing the importance of alone time (time spent in silence and solitude or simply being reflective and mindful when in a group) is essential. When I was up on Capitol Hill speaking to some Members of Congress and their Chiefs of Staff on the topic of resilience, I took away an important quote by a former Senator. When asked what he felt was one of the greatest dangers facing the Congress today he replied, “Not enough time to think.” We need some quiet time to be mindful or we will not make it.

We are all in a tough spot now as compassion erosion seems to be spiking for the present. Many of us feel even more than ever before that life is not good and we have little to share with others. However, taking a page from the posttraumatic growth (PTG) literature is essential: namely, some persons who experience severe stress or trauma have the possibility to experience even greater personal insight and depth in their lives that would not have been possible had the terrible events not happened in the first place. So, chronic and acute stress need not be the last word. They may even set the stage for a life of greater, not less, compassion and an appreciation of what and who is truly important to us. However, for this to happen, we need to recognize the danger and do something about it now.

The post A spike in “compassion erosion” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMonastic silence and a visual dialogueBimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 2The divine colour blue

Related StoriesMonastic silence and a visual dialogueBimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 2The divine colour blue

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers