Oxford University Press's Blog, page 751

October 15, 2014

A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2

Color names have been investigated in almost overwhelming detail, but it is not the etymology but usage that tends to “throw us off the scent.” One can have no quarrel with the statement that different communities will use a certain term differently, for the basis of comparison may be different (so Francis A. Wood, a great specialist in historical semantics). Wood cited the case of “smeared.” Some people associate “smeared” with “dirty” (hence “brown; black”), while others with “oily” (hence “shiny” and even “bright; yellow; white”). It is harder to agree that “in primitive times colors were not carefully distinguished,” because we don’t know what “primitive times” means. The centuries of Classical Greek, Old English, or some remote epoch from which we have no documents and about whose language habits we can judge only from those of modern “primitive peoples” studied by missionaries and anthropologists? Also, how “careful” should one be in distinguishing colors? The idea that some general notion like “smeared” can diverge and yield opposite meanings is fully acceptable. We are in trouble when a word displays seemingly incompatible meanings in the same language or in closely related languages.

Metaphors do not confuse us, and therefore we accept the idiom green years. We can also let greenhorns and our acquaintances who are still green behind the ears enjoy their youthful inexperience. Perhaps green in green cheese, the moon’s main ingredient in folklore, does mean “fresh,” as I have read, but I still feel some discomfort when an Icelandic saga mentions green meat, green fish, and green butter. In the sagas, green also means “safe, excellent” (and green roads in Old Germanic referred to good roads devoid of danger), so perhaps not fresh (unsalted?) meat, fish, and butter are meant but products of exceptional quality, something one can eat without fearing for one’s health?

Red yolk, occurring in Old Icelandic, also amazes me (in English, yolk has the root of yellow), and so does red gold, a collocation used in the epic poetry all over Europe. Does red mean “scintillating” here, or do we not know something about ancient minting? And how did red gold become a formula in several traditions? Some such phrases have been explained, but the explanations do not always sound fully convincing. In dealing with color names one cannot be too careful. Etymology is of little help here. For example, green has the same root as grow (thus, green is the color of vegetation) and cats have green eyes; yet we still don’t quite understand why jealousy, if we can trust Shakespeare, is a green-eyed monster. Likewise, red is, from an etymological point of view, the color of ore (as follows from Russian ruda “ore”; stress on the second syllable), but coins were not made from ore.

Brown is no less opaque than green or red. Older scholars traced brown to the root of burn (Old Engl. brinnan ~ birnan, Gothic brinnan, and so forth). Allegedly, that is why brown can refer to both dark and bright shades. But brown and burn are hardly related, and, even if they were, those who spoke Old English and Old Icelandic would not have been aware of the ancient root. As mentioned in Part 1 of this essay, brown horses or possibly shields of Germanic speakers seem to have impressed the Romance world so strongly that the word for “brown” made its way into the speech of the French, Italians, and others. In the Germanic languages, shields and occasionally helmets and swords were called brown (= “shining”). This sense returned from Romance to English, which has burnish from French and the verb to brown; both mean “to polish.” In some parts of the German-speaking world (predominantly in the south), braun “brown” means “violet”; Luther used it in this sense. In medieval German literature, compounds turned up that can be glossed as “scarlet-brown” and “black-brown.” Their second components must have emphasized their sheen.

Chesterton’s Pater Brown at his best.

Chesterton’s Pater Brown at his best.In the past, several distinguished language historians thought, and some of their followers still think that brown “shining” and brown “violet” are homonyms, both etymologically distinct from brun (long u, as in Engl. woo) “brown.” Fortunately, there has been no agreement among them, and this explanation has not become dogma, but the idea that braun “violet” owes its existence to Latin prunum “plum” (hence Engl. prune) has gained wide acceptance. For example, it was endorsed by Elmar Seebold, the latest editor of Kluge’s German etymological dictionary, a deservedly authoritative source. According to the rule known as Occam’s razor, entities should not be multiplied (with regard to etymology, I discussed it briefly in the post on qualm). Jacob Grimm suggested that, in dealing with ancient homonyms, it is advisable to treat them as going back to the same root. Given the baffling variety of senses the main color names typically show, it is perhaps more prudent to stay with one basic word that branched off in many unpredictable ways.

What else has been recorded as brown? If the color brown had magical connotations, Germanic shields, swords, and horses may have inspired awe and fear rather than admiration. In the broad Slavic-Iranian belt, brown was a common epithet of stallions and deities. There it was obviously not borrowed from Germanic. In German baroque literature, the phrase braune Nacht “brown night” appeared, and poets began to speak about the brown shadows of night. This usage has been explained as a loan from Romance. Even if so, today we don’t think of night or shadows as brown (compare Byron’s clear obscure, an English version of Italian chiaroscuro).

During the Renaissance, brown competed with black as the color of mourning, especially with reference to mourning women. It suggested merging with the background, being somber, unattractive, inconspicuous. We note with surprise how many Ancient Greek names began with Phryn- “brown” (Phryniskos, Phrynion, and the like). They remind one of Jude the Obscure. Didn’t they originally refer to the insignificance or low status of the bearers? In Part 1, I wrote that the family name Brown ~ Braune needs an explanation but was reminded of Black, White, and Green. Black and White can also be accounted for in several ways. In the population of blonds, would “white” have become a distinguishing feature? To my mind, brown as an allusion to the color of the person’s hair does not look persuasive. How many Greeks had brown hair? If their rarity is the origin of the moniker, then what was so special about Germanic speakers with chestnut-colored hair?

Perhaps an especially revealing phrase is Dante’s sangue bruno “brown blood,” said about gore, that is, blood shed and clotted or simply clotted. English speakers had the word dreor “gore, flowing blood.” It is still alive as the root of the adjective dreary, originally “bloody, gory, grievous, sorrowful,” later “dismal, gloomy.” Homer called blood porphyros “purple” (or “crimson”?), but he also used this adjective when he described descending death. These bridges between “brown” and “red” will perhaps allow us to understand the strange predilection for brown waves (as in Beowulf), wine-colored sea (as in Homer), and the colors of the planet Saturn, which was called by the ancients black, brownish, and fiery. One thing can already be said now: in the history of the Indo-European languages, “brown” designated both a dark and a bright color. Our modern gloss “brown” does it less than full justice.

Question: Can anyone say why Hitler’s SA adopted brown shirts as its uniform? Did the color have any symbolic value?

To be continued.

Image credits: (1) Moon with an unhealthy greenish coating, modified from Michael K. Fairbanks’s photo. Image by Naive cynic, CC-BY-SA-3.0-MIGRATED; GFDL-WITH-DISCLAIMERS via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Illustration from The Innocence of Father Brown, public domain via Project Gutenberg Australia.

The post A Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 2Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1

Related StoriesA Study in Brown and in a Brown Study, Part 1Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 2Bimonthly etymology gleanings for August and September 2014. Part 1

A conversation with Dr. Steven Nelson, Grove Art Online guest editor

Grove Art Online recently updated with new content on African art and architecture. We sat down with Dr. Steven Nelson, who supervised this update, to learn more about his background and the field of African art history.

Can you tell us a little about your background?

As an undergraduate at Yale, after flirting with theater, music, and sociology, I majored in studio art and focused on bookmaking, graphic design, printmaking, and photography. Majors were required to take three art history classes. By the end of my college career, I had taken eight and had seriously thought about changing my major. Within art history, I was most attracted to modern and Japanese art, and studying the two fields had profound effects on art making. After a six-year-long stint in newspaper design, I went to Harvard to pursue a Ph.D. in modern art. After coursework in myriad fields, serving on a search committee for a new faculty member in African art (the search resulted in the hiring Suzanne Preston Blier), and a trip to Kenya to study medieval Swahili architecture, I changed my field to African art. My dissertation is a study of Mousgoum architecture (one of the fields covered in Grove Art Online’s African update) in Cameroon. The thesis became my first book, entitled From Cameroon to Paris: Mousgoum Architecture In and Out of Africa (University of Chicago Press, 2007). Having been an artist has had a profound effect on how I encounter art objects and the built environment.

You recently served as editor for the Grove Art Online African art update. What was your favorite part about this experience?

My favorite part of serving as editor for the Grove Art Online African art update was the opportunity to have a widely used and respected resource as a platform to reassess and to reshape the canon of African art. More to the point, Grove provided a unique opportunity to rearticulate the field’s various methods, to acknowledge shifts in scholarly focus, and to expand the subjects we consider when hearing the very term “African art.” As someone who has served at various points as an editor, I also enjoyed working with authors to produce essays that are both rich in content and accessible to a broad audience. I’m also very pleased that the authors included in the update range from very eminent art historians to graduate students with whom I closely worked.

Igbo and His People. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Igbo and His People. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.What is your favorite work of art of all time, and why?

My favorite work of art of all time changes day-by-day. Right now Malick Sidibé’s party photographs of the 1960s, which explore a burgeoning, international youth culture in Bamako on the heels of independence, hold this title.

Which recently added African art article(s) stand out to you, and why?

While I am really happy with all of the new content, the material on African film and the essay on African modern art are particular importance for me. In African art history, broadly speaking, film has received very little attention (in full disclosure, I write on it myself). However, it is critical in understanding the complexity of modern and contemporary African art. The essay on modern African art is important in that it marks an important expansion of the field, one in which scholars are insisting on understanding modernity and how African artists engage with it with more nuance and precision.

How has your field changed in the past 20 years?

The past 20 years have witnessed a groundswell in studies of modern and contemporary African art. Alongside of this development, the past 20 years have also seen a lot of energy (for better or worse) spent on understanding the relationship between modern and contemporary and “traditional” or “classical” African art. On the one hand, some feel that the two should be considered as separate fields, with the former being a kind of offshoot of global contemporary art. On the other, some feel that the two can inform each other in exciting ways. Having done research on topics ranging from medieval Swahili architecture to contemporary art in Africa and its diasporas, I personally ascribe to the latter view. Methodologically, much has changed as well. Africanist art historians have become much more willing to incorporate poststructuralist and post-colonial scholarship into their studies, and the results have enriched how we understand the subjects of our endeavors. There has also been much welcome attention paid to the important intersections of African art and Islam as well as African art and Christianity.

How do you envision art history research being done in 20 years?

Digital humanities will no doubt have an enormous impact research on art history research. Digital tools allow for quick aggregation, and this can add rich dimensions to our research. One of the challenges, however, will be to see how — or if — the digital realm provides the means for new questions and new art historical knowledge. I helped facilitate a digital art history workshop at UCLA this past summer, and that question, one that really strikes at the place of the digital as we move forward, is one that I engage with both optimism and a healthy skepticism.

The post A conversation with Dr. Steven Nelson, Grove Art Online guest editor appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War IDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?Analyzing the advancement of sports analytics

Related StoriesDispatches from the Front: German Feldpostkarten in World War IDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?Analyzing the advancement of sports analytics

Political economy in Africa

Political economy is back on the centre stage of development studies. The ultimate test of its respectability is that the World Bank has realised that it is not possible to separate social and political issues such as corruption and democracy from other factors that influence the effectiveness of its investments, and started using the concept.

It predates the creation of “economics” as a discipline. Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus, James Mill, and a generation later Karl Marx and Friederich Engels, explored how groups or classes in society exploited each other or were exploited, and used their conclusions to create theories of change or growth.

Marx’s ideas were taken up in the 1950s by economists and sociologists of the left, such as Paul Baran (The Political Economy of Growth, 1957) and later Samir Amin (The Political Economy of the Twentieth Century, 2000) who linked it to theories of imperialism and neo-colonialism to interpret what was happening in newly independent African countries where nationalist political parties had taken power.

Marx and Engels in their early writings, and Marxist orthodoxy subsequently, espoused determinist theories in which development went through pre-determined stages – primitive forms of social organisation, feudalism, capitalism, and then socialism. But in their later writings Marx and Engels were much more open, and recognised that some pre-capitalist formations could survive, and that there was no single road to socialism. Class analysis, and exploration of the economic interests of powerful classes, and their uses of the technologies available to them, could inform a study of history, but not substitute for it.

That was how I interpreted what happened in Tanzania in the 1970s. The country was built around the economic interests of those involved, and the mistakes made, both inside Tanzania but also outside. It focussed on the choices made by those who controlled the Tanzanian state or negotiated “foreign aid” deals with Western governments—Issa Shivji’s bureaucratic bourgeoisie. These themes are still current today.

Returning home after a day’s work, by Martapiqs. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Returning home after a day’s work, by Martapiqs. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.I am not alone. Michael Lofchie’s (A Political Economy of Tanzania, 2014) focuses on the difficult years of structural adjustment in the 1980s and 1990s). He argues how the salaried elite could personally benefit from an overvalued exchange rate. From 1979 on, under the influence of the charismatic President Julius Nyerere, Tanzania resisted the IMF and World Bank which urged it to devalue. But eventually, around the mid-1980s, they realised that they had the possibility of making even bigger financial gains if the country devalued and there were open markets, which would allow them to make money from trade or production. They were becoming a productive bourgeoisie.

Lofchie’s analysis can be contested. The benefits of the chaos that resulted from the extremely over-valued exchange rates of the 1980s were reaped by only a few. It is true that rapid growth followed from around 1990 to the present, but that is also due to the high price of gold on international markets and the rapid expansion of gold mining and tourism. There is still plenty of evidence of individuals making money illegitimately – corruption is ever present in the political discourse, and will continue to be so up till the Presidential elections due in October 2015.

A challenge for the ruling class in Tanzania, leaving the 1970’s, was would they be able to convert their economic strategies into meaningful growth and benefits for the population? By 2011 the challenge was even more acute, because very large reserves of gas had been discovered off the coast of Southern Tanzania, so money for investment would no longer be a binding constraint. But would those resources be used to create real assets which would create the prerequisites for rapid expansions in manufacturing, services and especially agriculture? Or would they be frittered away through imports of non-productive machinery and infrastructure (such as the non-existent electricity generators purchased through the Richmond Project in 2006 in which several leading members of the ruling political party were implicated)? Or end up in Swiss bank accounts? The jury is very much still out. To achieve the current ambition of a rapid transition to a middle income country will require much greater understanding of engineering, agricultural science, and much better contracts than have been recently achieved – and more proactive responses to the challenges of corruption. It will need to take its own political economy seriously.

Headline image credit: Tanzania – Mikumi by Marc Veraart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Political economy in Africa appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?Analyzing the advancement of sports analyticsAnnouncing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pick

Related StoriesDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?Analyzing the advancement of sports analyticsAnnouncing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pick

The life of a bubble

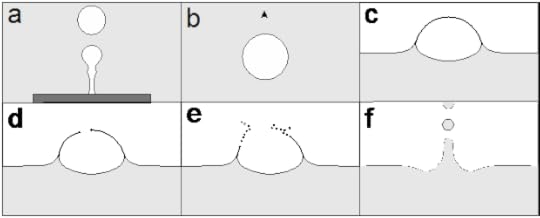

They might be short-lived — but between the time a bubble is born (Fig 1 and Fig 2a) and pops (Fig 2d-f), the bubble can interact with surrounding particles and microorganisms. The consequence of this interaction not only influences the performance of bioreactors, but also can disseminate the particles, minerals, and microorganisms throughout the atmosphere. The interaction between microorganism and bubbles has been appreciated in our civilizations for millennia, most notably in fermentation. During some of these metabolic processes, microorganisms create gas bubbles as a byproduct. Indeed the interplay of bubbles and microorganisms is captured in the origin of the word fermentation, which is derived from the Latin word ‘fervere’, or to boil. More recently, the importance of bubbles on the transfer of microorganisms has been appreciated. In the 1940s, scientists linked red tide syndrome to toxins aerosolized by bursting bubbles in the ocean. Other more deadly illnesses, such as Legionnaires’ disease have been linked since.

Figure 1: Bubble formation during wave breaking resulting in the white foam made of a myriad of bubbles of various sizes. (Walls, Bird, and Bourouiba, 2014, used with permission)

Figure 1: Bubble formation during wave breaking resulting in the white foam made of a myriad of bubbles of various sizes. (Walls, Bird, and Bourouiba, 2014, used with permission)Bubbles are formed whenever gas is completely surrounded by an immiscible liquid. This encapsulation can occur when gas boils out of a liquid or when gas is injected or entrained from an external source, such as a breaking wave. The liquid molecules are attracted to each other more than they are to the gas molecules, and this difference in attraction leads to a surface tension at the gas-liquid interface. This surface tension minimizes surface area so that bubbles tend to be spherical when they rise and rapidly retract when they pop.

Figure 2: Schematic example of Bubble formation (a), rise (b), surfacing (c), rupture (d), film droplet formation (e), and finally jet droplet formation (f) illustrating the life of bubbles from birth to death. (Walls, Bird, and Bourouiba, 2014, used with permission)

Figure 2: Schematic example of Bubble formation (a), rise (b), surfacing (c), rupture (d), film droplet formation (e), and finally jet droplet formation (f) illustrating the life of bubbles from birth to death. (Walls, Bird, and Bourouiba, 2014, used with permission)When microorganisms are near a bubble, they can interact in several ways. First, a rising bubble can create a flow that can move, mix, and stress the surrounding cells. Second, some of the gas inside the bubble can dissolve into the surrounding fluid, which can be important for respiration and gas exchange. Microorganisms can likewise influence a bubble by modifying its surface properties. Certain microorganisms secrete surfactant molecules, which like soap move to the liquid-gas interface and can locally lower the surface tension. Microorganisms can also adhere and stick on this interface. Thus, a submerged bubble travelling through the bulk can scavenge surrounding particulates during its journey, and lift them to the surface.

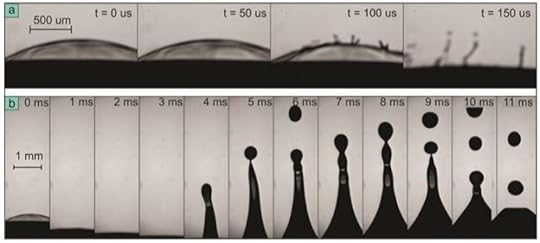

When a bubble reaches a surface (Figure 2c), such as the air-sea interface, it creates a thin, curved film that drains and eventually pops. In Figure 3, a sequence of images shows a bubble before (Fig 3a), during, and after rupture (Fig 3b). The schematic diagrams displayed in Fig 2c-f complement this sequence. Once a hole nucleates in the bubble film (Fig 2d), surface tension causes the film to rapidly retract and centripetal acceleration acts to destabilize the rim so that it forms ligaments and droplets. For the bubble shown, this retraction process occurs over a time of 150 microseconds, where each microsecond is a millionth of a second. The last image of the time series shows film drops launching into the surrounding air. Any particulates that became encapsulated into these film droplets, including all those encountered by the bubble on its journey through the water column, can be transported throughout the atmosphere by air currents.

Figure 3: Photographs, before, during, and after bubble ruptures. The top panel illustrated the formation of small film droplets; the bottom panel illustrates the formation of larger jet drops. (Bird, 2014, used with permission)

Figure 3: Photographs, before, during, and after bubble ruptures. The top panel illustrated the formation of small film droplets; the bottom panel illustrates the formation of larger jet drops. (Bird, 2014, used with permission)Another source of droplets occurs after the bubble has ruptured (Fig 3b). The events occurring after the bubble ruptures is presented in the second time series of photographs. Here the time between photographs is one milliseconds, or 1/1000th of a second. After the film covering the bubble has popped, the resulting cavity rapidly closes to minimize surface area. The liquid filling the cavity overshoots, creating an upward jet that can break up into vertically propelled droplets. These jet drops can also transport any nearby particulates, also including those scavenged by the bubble on its journey to the surface. Although both film and jet drops can vary in size, jet drops tend to be bigger.

Whether it is for the best or the worst, bubbles are ubiquitous in our everyday life. They can expose us to diseases and harmful chemicals, or tickle our palate with fresh scents and yeast aromas, such as those distinctly characterizing a glass of champagne. Bubbles are the messenger that can connect the depth of the waters to the air we breathe and illustrate the inherent interdependence and connectivity that we have with our surrounding environment.

The post The life of a bubble appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat exactly is intelligence?Gangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the USDomestic violence and the NFL. Are players at greater risk for committing the act?

Related StoriesWhat exactly is intelligence?Gangs: the real ‘humanitarian crisis’ driving Central American children to the USDomestic violence and the NFL. Are players at greater risk for committing the act?

October 14, 2014

Analyzing the advancement of sports analytics

The biggest story heading into the 2014-15 National Hockey League (NHL) season appears to not be what is happening with players on the ice. Rather, it is the people working off the ice who evaluate players’ performance on the ice that have a leading role in the NHL’s narrative. The analytics movement has come full force to professional hockey. Teams all across the NHL have hired people with expertise in analytics that can develop proprietary statistical analysis to give their teams a competitive edge. The Toronto Maple Leafs alone hired three analysts this past offseason.

The NHL is the latest league to make a significant investment in analytics. Major League Baseball (MLB) is well-known for its use of sabermetrics, as most famously deployed by general manager Billy Beane and the Oakland Athletics. The National Basketball Association (NBA) has spent the last decade hiring people for senior level positions with strong analytics backgrounds, as exemplified by the Houston Rockets selecting Daryl Morey for their General Manager role.

The rise of analytics to evaluate player performance raises a natural question. If teams and leagues increasingly believe analytics can provide a competitive advantage during competitions, then why not make more use of use analytics to help their businesses as well? In fact, sports teams and leagues should take advantage of the opportunities to hire quantitatively-savvy managers and analysts focused primarily on growing an organization’s revenue.

What value does this provide to an organization? In a recent article in Forbes, I showed how combining analysis of a quarterback’s on-field and off-field performance can provide a more holistic view of his value to an organization. However, focusing on individual athletes’ economic impacts is only the start of how quantitative analysis can impact sports organizations’ businesses. The most common example is with pricing tickets. Dynamic pricing has changed the way that teams, fans, media, and sponsors think about how they purchase tickets. Secondary market ticket sites, such as StubHub, and new dynamic ticket pricing models, such as Purple Pricing, have provided sports organizations with the opportunity to make more money while giving fans better options for buying tickets to games.

Ticket pricing is not the only revenue stream where analytics can be applied. For example, sponsorship revenue can use a more analytical approach to demonstrate how sports organizations often generate a significant return on investment for their partners. Sports organizations have traditionally used qualitative approaches to demonstrate a return on investment for their corporate partners in sponsorship deals. This includes developing recaps that have pictures of sponsorship activation elements during the course of the season such as a picture of a brand’s logo on signage at a sports venue.

However, corporate partners should be presented with a dollar amount for the return on investment that they are receiving by sponsoring an organization. Teams can use analytical models to show how the impressions they generate with lucrative sports audiences creates new customers, helps retain current customers, increases brand awareness, or enhances brand perception. Employing analytics in sports sponsorship provides sponsors with clear reasons why they are getting value by working with a sports organization.

Employing business analytics also helps to specifically address issues when a team or athlete is not successful in competition. Relying on winning is a losing strategy. Teams that rely on winning do not always achieve financial success. In addition, winning is still difficult to predict or control – even as teams hire more people to analyze their competitive performance. Deploying business analytics helps to address these issues. It can show what strategies, marketing campaigns, and promotions work best to generate revenue regardless of a team’s performance. With the influx of new technology into the sports industry impacting ticket purchases, in-game concession sales, digital and mobile streaming, social media engagement, and many others, there is a wealth of new data available to sports organizations. The next Moneyball will be the teams that can find insights from this data to generate money for their organizations.

Headline image credit: Ice hockey stadium. CC0 via Pixaby.

The post Analyzing the advancement of sports analytics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDallas Cowboys: seven strategies that will guarantee a successful 2014 seasonDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?Life in New Orleans during the Reconstruction Era [infographic]

Related StoriesDallas Cowboys: seven strategies that will guarantee a successful 2014 seasonDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?Life in New Orleans during the Reconstruction Era [infographic]

Life in New Orleans during the Reconstruction Era [infographic]

Reconstruction was a time of great change in the city of New Orleans. The Civil War had just ended, and the South was devastated. Although Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had done much for racial equality, racial tension and conflict was ubiquitous in New Orleans. In June 1870, at the height of Reconstruction, 17-month-old Irish-American Mollie Digby was kidnapped from outside her home. The kidnapping was highly publicized in the media of the day, and residents of New Orleans followed the story with intense fervor, all the way to the sensationalized trial of two Afro-Creole women. In The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case: Race, Law, and Justice in the Reconstruction Era, Michael A. Ross looks at why the story of Mollie Digby was so important, and what it reveals about that point in New Orleans history. Below is an infographic depicting life in New Orleans at the time of Mollie Digby’s kidnap.

Download a jpg or PDF of the infographic.

Heading image: 1857 view of Canal Street. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Life in New Orleans during the Reconstruction Era [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSetting the scene of New Orleans during ReconstructionDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?In person online: the human touch

Related StoriesSetting the scene of New Orleans during ReconstructionDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?In person online: the human touch

In person online: the human touch

What is the human touch in online learning? How do you know if it’s there? What does it look and feel like? My epiphany on this topic occurred when a student told me “I thought I would have done better if I had a real teacher.”

This pronouncement triggered a cascade of questions: Why didn’t she see me as real? Because we weren’t in the same physical space? The physical separation of instructor and students creates a psychological and communications gap, and the missing element is the perception of people as real in an online environment — the human touch. Did she think the computer produced the instruction and the teacher interaction? How could this happen when I felt deeply involved in the course — posting detailed reading guides and supplementary materials, leading and participating in discussions, and giving individual feedback on assignments? Was technology getting in the way or was it the way I was using it? In the online classroom we hope that the technology becomes transparent and that students just have a sense of people interacting with other people in an online learning community. And this issue isn’t limited to students. Instructors are sometimes concerned that they won’t be able to achieve the energy of the face-to-face classroom and the electricity of an in-person discussion if they teach online. It’s a matter of presence and personal style.

Internet Cafe after Jean Beraud. Mike Licht, NotionsCapital.com, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

Internet Cafe after Jean Beraud. Mike Licht, NotionsCapital.com, CC BY 2.0 via FlickrWe can create the human touch by establishing an online presence – a sense of really being there and being together for the course. To be perceived as real in the online classroom we need to project ourselves socially and emotionally, and find ways to let our individual personality shine through whatever communications media we’re using. We can look to our own face-to-face teaching style for ways to humanize an online course. What do we do in a face-to-face classroom to make ourselves more approachable? We talk with students as they arrive for class, spice up lectures with touches of humor and relevant personal stories, treat discussions as conversations, and sometimes depart from what we planned so we can follow more promising asides.

To translate these techniques for the online classroom we can look to the issue of physical separation. We use the terms “face-to-face” and “online,” but online isn’t synonymous with faceless and impersonal. In fact, faces can contribute to the human touch. Pictures of the instructor and the students, brief instructional videos, and video-enabled chat all provide images of real people. They add a human touch and contribute to a more vivid sense of presence — of being perceived as real. And posting short introductory autobiographies helps course participants establish personal connections that pave the way for open communication and collaboration. With the use of strategies like these the technology may begin to recede from consciousness, the focus can shift from technology to people, and ultimately the technology may even seem to disappear as people just interact with each other.

Once you’ve established a sense of presence, you want to maintain and extend it. Regular, brief, informal announcements like those we typically make in a face-to-face class — a welcome message at the beginning of a course, reminders of due dates for assignments, current news items relevant to course content — help make our presence felt and assure students that we’re there, we’re working along with them, and we’re interested in their progress and success. Using our normal conversational tone for any online instructional posts (the agenda for the week, descriptions of readings, instructions or prompts for discussion posts) reinforces that sense of personal style. A practice of poking your head in to asynchronous discussions and making brief comments lets students know you’re there and available for help, but avoids the impression of dominating the discussion. Audio or video-enabled synchronous meetings provide a place where people can be themselves, join in informal discussions, show their enthusiasm for their subject matter with individual presentations, or experience the energy of brainstorming sessions — much as they would in a face-to-face classroom. All these techniques can contribute to that human touch, helping us reveal our real selves and engage our students in a vital online learning community.

What personal touches have you used online? Have you found particularly successful techniques you’d suggest others try?

Headline image credit: Headphones. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post In person online: the human touch appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe role of grammar for the teaching of LatinWhat is the most important issue in music education today?Announcing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pick

Related StoriesThe role of grammar for the teaching of LatinWhat is the most important issue in music education today?Announcing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pick

The role of grammar for the teaching of Latin

The development of linguistics as a scientific discipline is one of the greatest achievements of contemporary thought, as it has led to the discovery of some fundamental principles about the functioning of language. However, most of its recent discoveries have not yet reached the general audience of educated people beyond the specialists. Scholars of classics, in particular, have found it difficult to become involved in the debate, since many recent studies in linguistics have been driven by the necessity to free themselves from the subordination to Latin grammar and have put into question the validity of certain aspects of traditional grammar.

As a consequence, progress made by contemporary linguistics has paradoxically had a negative rather than positive effect on the teaching of Latin. Although traditional grammars are now outdated, a suitable replacement has not yet been offered and a widespread scepticism has forced many to keep relying on old fashioned textbooks.

In order to overcome this undesirable state of affairs, it is desirable to bring Latin grammar back to its original high-level scientific conception, going beyond a prescriptive attitude and restoring the original theoretical tension. Although many branches of contemporary linguistics are potentially suited to fulfil this objective, none of them have been fully exploited in teaching yet. Their advantage over traditional approaches lies in their ability to satisfy the same needs as traditional analytical and philosophical Latin grammar, exploiting – at the same time – new methods, which are suitable to formulate more accurate analyses and theoretical generalizations.

Latin grammar should be presented as an activity which raises the linguistic awareness of its readers, using the most recent tools of modern linguistics. This should not be limited to the traditional Indo-European historical perspective, but includes the comparison of different languages and the attempt to represent the way in which grammar rules are codified in the mind.

Italy-Vaticano by gnuckx. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Italy-Vaticano by gnuckx. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThe hypothesis is that there exists a language faculty underlying all languages, known as Universal Grammar (UG), i.e. a system of variable and invariable factors internalized in the speaker’s mind, which constitutes the basis of the grammar of each language. Understanding the contents of UG amounts to understanding those linguistic phenomena that are common to all languages. In this perspective, it is possible to develop a new method of teaching Latin, which aims at strengthening the cognitive skills of the learner’s mind. This method consists in overcoming the rigidity of a purely normative conception of grammatical rules, in order to make them explicit in a synchronic formal way and thus formulate hypotheses about the mental mechanisms that generate them. This method is an updated enhancement of the old conception of grammatical studies known as progymnasmata, i.e. “gymnastics of the mind,” which introduces the reader to the world of classical scholarship.

On the basis of some recent discoveries made by the neurosciences, it is possible to formulate grammatical rules that represent a better approximation of the implicit and explicit mental operations carried out by the language learner. The desired effect is the activation of the appropriate areas of the brain, i.e. the ones which are naturally devoted to the processing of linguistic information, thus rendering the process of language acquisition faster and more natural. Indeed, a vast number of recent studies have shown that language learning strongly relies on a constant and unconscious comparison between the second language (L2) and the learner’s mother tongue. By comparing linguistic phenomena across distinct languages and by interpreting the results with updated theoretical tools, we intend to underlie the deep similarities among languages rather than their superficial differences. This new teaching perspective represents a fundamental advantage for learners, who can focus their attention on the limits of linguistic variation, making their acquisitional task more feasible. In particular, by overtly reflecting on language and comparing L2 grammars to the structures of the mother tongue, the study of Latin becomes more stimulating and active.

Moreover, as students become aware of the difference between a “mistake”, as banned from the standard language, and linguistic “agrammaticality” (i.e. an option which is disallowed by the deep structure of the language), they become more critical and aware of the level of their written and oral performance in their mother tongue. From this perspective, it is clear that the study of Latin contributes to the overall linguistic education of learners, and not only to the training of those interested in classical studies. Students should no longer learn by heart the obscure rules of school grammars, often rooted on misconceptions, but they should instead explore the discoveries of centuries of classical scholarship in order to actively work out how languages function and change. In particular, they should focus their attention on the aspects of the targeted language they already know, before exploring the points of divergence from their mother tongue. Thanks to this revised methodology, the study of Latin loses any passive connotation and becomes an activity which enhances linguistic awareness, meta-linguistic competence, as well as critical thought.

The post The role of grammar for the teaching of Latin appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?Facebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronounsFrom “Checkers” to Watergate

Related StoriesDoes political development involve inherent tradeoffs?Facebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronounsFrom “Checkers” to Watergate

October 13, 2014

Announcing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pick

With the end of 2014 approaching and the publication of the 21st edition of Oxford’s Atlas of the World, we’re considering the most noteworthy places from the past year with our annual Place of the Year (POTY) campaign.

We’ve compiled a long list of ten places that stood out to us in 2014, and you can vote for your choice below. Additionally, we’d love to receive nominations that are not included on this long list, and those can be submitted via the comments section. Follow along with #POTY2014 until our announcement on 1 December.

What do you think Place of the Year 2014 should be?

As can be seen in the video we put together of a few of our past winners, Places of the Year have been as geographically varied as Warming Island and Mars, so feel free to be as imaginative as you’d like with your nominations. We will post the short list on November 3, and the Place of the Year 2014 will be announced on December 1. In the interim, be on the lookout for more information on this year’s nominees as well as past winners with maps, videos, and more.

Image credit: World map made with natural earth data, Eckert 4 projection, central meridian 10° east. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Announcing Place of the Year 2014 longlist: Vote for your pick appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCountries of the World Cup: NetherlandsCountries of the World Cup: ArgentinaReading Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations with a modern perspective

Related StoriesCountries of the World Cup: NetherlandsCountries of the World Cup: ArgentinaReading Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations with a modern perspective

Reading Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations with a modern perspective

Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations is a remarkable phenomenon, a philosophical diary written by a Roman emperor, probably in 168-80 AD, and intended simply for his own use. It offers exceptional insights into the private thoughts of someone who had a very weighty public role, and may well have been composed when he was leading a military campaign in Germany. What features might strike us today as being especially valuable, bearing in mind our contemporary concerns?

At a time when the question of public trust in politicians is constantly being raised, Marcus emerges, in this completely personal document, as a model of integrity. Not only does he define for himself his political ideal (“a monarchy that values above all things the freedom of the subject”) and spell out what this ideal means in his reflections on the character and lifestyle of his adoptive father and predecessor as emperor, Antoninus Pius, but he also reminds himself repeatedly of the triviality of celebrity, wealth and status, describing with contempt the lavish purple imperial robe he wore as stained with “blood from a shellfish”. Of course, Marcus was not a democratic politician and, with hindsight, we can find things to criticize in his acts as emperor — though he was certainly among the most reasonable and responsible of Roman emperors. But I think we would be glad if we knew that our own prime ministers or presidents approached their role, in their most private hours, with an equal degree of thoughtfulness and breadth of vision.

Another striking feature of the Meditations, and one that may well resonate with modern experience, is the way that Marcus aims to combine a local and universal perspective. In line with the Stoic philosophy that underpins his diary, Marcus often recalls that the men and women he encounters each day are fellow-members of the brotherhood of humanity and fellow-citizens in the universe. He uses this fact to remind himself that working for his brothers is an essential part of his role as an emperor and a human being. This reminder helps him to counteract the responses of irritation and resentment that, he admits, the behavior of other people might otherwise arouse in him. At a time when we too are trying to bridge and negotiate local and global perspectives, Marcus’s thoughts may be worth reflecting on. Certainly, this seems to me a more balanced response than ignoring the friend or partner at your side in the café while engrossed in phone conversations with others across the world.

Bust of Marcus Aurelius, Musée Saint-Raymond. By Pierre-Selim. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bust of Marcus Aurelius, Musée Saint-Raymond. By Pierre-Selim. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.More broadly, Marcus, again in line with Stoic thinking, underlines that the ethics of human behavior need to take account of the wider fact that human beings form an integral part of the natural universe and are subject to its laws. Of course, we may not share his confidence that the universe is shaped by order, structure and providential care — though I think it is worth thinking seriously about just how much of that view we have to reject. But the looming environmental crisis, along with the world-wide rise in obesity and the alarming healthcare consequences, represent for us a powerful reminder that we need to rethink the ethics of our relationship to the natural world and re-examine our understanding of what is natural in human life. Marcus’s readiness to see himself, and humanity, as inseparable parts of a larger whole, and to subordinate himself to that whole, may serve as a striking example to us, even if the way we pursue that thought is likely to be different from that of Stoicism.

Another striking theme in the Meditations is the looming presence of death, our own and those of others we are close to. This might seem very alien to the modern secular Western world, where death is often either ignored or treated as something too terrible to mention. But the fact that Marcus’s attitude is so different from our own may be precisely what makes it worth considering. He not only underlines the inevitability of death and the fact that death is a wholly natural process, and for that reason something we should accept. He couples this with the claim that knowledge of the certainty of death does not undermine the value of doing all that what we can while alive to lead a good human life and to develop in ourselves the virtues essential for this life. Although such ideas have often formed part of religious responses to death (which have lost their hold over many people today) Marcus puts them in a form that modern non-religious people can accept. This is another reason, I think, why Marcus’s philosophical diary can speak to us today in a language we can make sense of.

Featured image: Marcus Aurelius’s original statue in Rome, by Zanner. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reading Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations with a modern perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhen tragedy strikes, should theists expect to know why?Plato and contemporary bioethicsFrom Imperial Presidency to Double Government

Related StoriesWhen tragedy strikes, should theists expect to know why?Plato and contemporary bioethicsFrom Imperial Presidency to Double Government

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers